Abstract

Background and Aims:

Post-operative sore throat (POST) is often considered an inevitable consequence of tracheal intubation. This study was performed to compare the effect of inhaled budesonide suspension, administered using a metered dose inhaler, on the incidence and severity of POST.

Methods:

In this prospective randomised study, 46 patients undergoing laparoscopic surgeries lasting <2 h were randomly allotted into two equal groups. Group A received 200 μg budesonide inhalation suspension, using a metered dose inhaler, 10 min before intubation, and repeated 6 h after extubation. No such intervention was performed in Group B. The primary outcome was the incidence and severity of POST. Secondary outocomes included the incidence of post-operative hoarseness and cough. Pearson's Chi-square test, Fisher's exact test and Independent sample t-test were used as applicable.

Results:

Compared to Group B, significantly fewer patients had POST in Group A at 2, 6, 12 and 24 h (P < 0.001). Although more patients in Group B had post-operative hoarseness of voice and cough at all-time points, the difference was statistically significant only at 12 h and 24 h for post-operative hoarseness and at 2 h and 12 h for post-operative cough. Severity as well as the incidence of POST showed downward trends in both groups over time, and by 24 h no patient in Group A had sore throat.

Conclusion:

Inhaled budesonide suspension is effective in significantly reducing the incidence and severity of POST.

Key words: Budesonide, cough, hoarseness, intubation, nebulizers and vaporizers, pharyngitis

INTRODUCTION

With an incidence of 21%–71.8%,[1,2,3] post-operative sore throat (POST) is very often considered to be synonymous with endotracheal intubation. It is commonly associated with hoarseness of voice and cough. Prophylactic management of POST is recommended to improve the quality of post-anaesthesia care, though the symptoms resolve spontaneously without any treatment.[4] Various drugs including ketamine, lidocaine and magnesium sulphate administered either by nebulisation or gargling, have some efficacy in reducing the symptoms. Delivery of the drug using a metered dose inhaler would obviate the need of additional equipment such as nebulisers or atomisers, and also avoid the requirement of assistance from nursing staff. Moreover, this mode of drug delivery is considered as simple and less time-consuming with high patient acceptability.

The primary aim of the present study was to compare the effects of inhaled budesonide suspension, administered using a metered dose inhaler, on the incidence and severity of POST in surgical patients following endotracheal intubation.

METHODS

This prospective, randomised, unblinded study was conducted after obtaining approval from hospital ethical committee and patients' written, informed consent.

Forty-six patients aged 18–60 years, of the American Society of Anaesthesiologists (ASA) physical status 1–2 with Mallampatti score of 1–2, undergoing short elective laparoscopic surgeries (laparoscopic sterilisation and diagnostic laparoscopy) lasting <2 h under general anaesthesia with endotracheal intubation were included in the study. Patients with anticipated difficult airway, history of allergy to the test drug, who required more than two attempts at intubation or nasogastric tube insertion and those with pre-operative sore throat or already on analgesics or steroids (systemic or inhaled) were excluded from the study.

The patients were randomly allotted into two equal groups, labelled A and B, based on computer-generated random sequence of numbers. Patients belonging to Group A received 200 μg budesonide inhalation suspension, using a metered dose inhaler (Budecort™ inhaler 200, Cipla Ltd) 10 min before intubation, which was repeated 6 h after extubation. The inhaler canister was shaken vigorously for about 10 s before use and was primed by spraying two test sprays into the air. Patients were then asked to breathe out fully, and the mouthpiece was placed into the mouth, pursing the lips around it. While breathing in slowly, the canister was pushed down, and the breath was held for 10 s. The patients were then asked to breathe out slowly. Each actuation of the canister delivered 200 μg budesonide IP suspended in chlorofluorocarbon-free propellant. In Group B, no such intervention was performed before intubation or after extubation.

All patients received general anaesthesia as per a standardised protocol. They were pre-oxygenated with 100% oxygen for 3 min, followed by intravenous (IV) glycopyrrolate 0.2 mg, midazolam 1 mg and fentanyl 2 μg/kg. Anaesthesia was induced with IV propofol 2 mg/kg and the lungs were ventilated via facemask with isoflurane 1% in oxygen.

IV Vecuronium 0.1 mg/kg was administered after induction and 3 min later, the trachea was intubated following a gentle and quick laryngoscopy lasting not more than 15 s with a low- pressure, high-volume cuffed polyvinyl chloride endotracheal tube. In males, 8 mm and in females, 7 mm internal diameter tubes were used. All intubations were performed by the same anaesthesiologist and confirmed with auscultation and end-tidal capnography. Endotracheal tube cuffs were filled with the minimal volume of air required to prevent an audible leak. Intraoperatively, the cuff pressure was checked immediately after intubation and thereafter, half-hourly using cuff inflator/pressure gauge PORTEX™ (Smiths Medical) cuff pressure monitor, and was maintained at 20–22 cm of H2O. Patients who required three or more attempts at laryngoscopy or nasogastric tube insertion were excluded from the study.

Anaesthesia was maintained using oxygen in air (1:2) with 1%–1.2% end-tidal isoflurane and intermittent positive pressure ventilation maintaining end-tidal carbon dioxide levels at 30–35 mm Hg. IV Vecuronium 1 mg was repeated at half an hour interval to provide muscle relaxation. IV Paracetamol 1 g was administered half an hour after induction. Rise in heart rate and/or mean arterial pressure more than 20% from the baseline value was initially treated with increasing the inspired concentration of isoflurane to 1.5%–2% transiently. If there was no response, IV 20 μg boluses of fentanyl were given.

At the end of the surgery, IV ondansetron 4 mg was given intravenously, and the residual muscle paralysis was reversed with IV neostigmine 0.05–0.07 mg/kg and glycopyrrolate 10 μg/kg. and nasogastric tube was suctioned and removed. Extubation was performed following gentle oro-pharyngeal suctioning using a soft suction catheter under vision. Post-operatively, all patients received paracetamol 1 g 8 hourly and tramadol 100 mg on demand intravenously. If this failed to control surgical site pain, intravenous fentanyl 20 μg incremental boluses were given. Total intra-operative as well as post-operative opioid consumptions were documented.

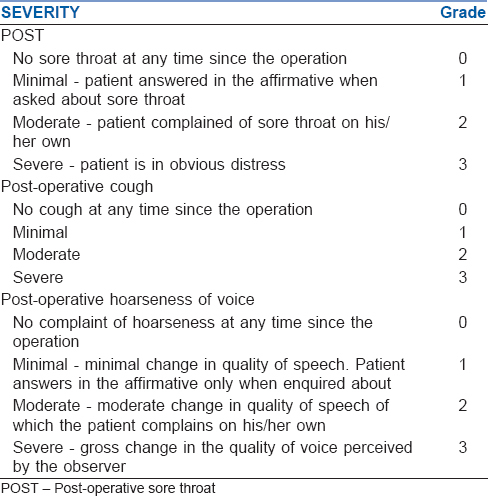

POST, cough and hoarseness of voice were assessed at 2, 6, 12 and 24 h based on the scales described in Table 1. Those with Grade III sore throat were given dispersible Aspirin 75 mg gargle which was repeated as many times as needed till there was relief from the symptoms. The number of times rescue therapy had been required for post-operative sore throat and pain and the modality used were also noted.

Table 1.

Assessment of severity of post-operative sore throat, cough and hoarseness of voice

Based on a previous study by Chen et al.[5] considering the incidence of the POST in patients who received budesonide nebulization as compared to control group (72.5% vs. 87.5%), with 95% confidence interval and 80% power, minimum sample size to obtain statistically significant result was calculated as 30. We recruited 46 patients with 23 in each group. Pearson's Chi-square test or Fisher's exact test was used to compare the categorical variables such as gender, ASA status, number of attempts at intubation, use of bougie, Mallampatti score, incidence and severity of POST, hoarseness of voice and cough. Independent sample t-test was used to compare the continuous variables such as age, weight, intraoperative opioid consumption and duration of intubation among the groups. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Version 20.0 for Windows (IBM Corporation ARMONK, NY, USA).

RESULTS

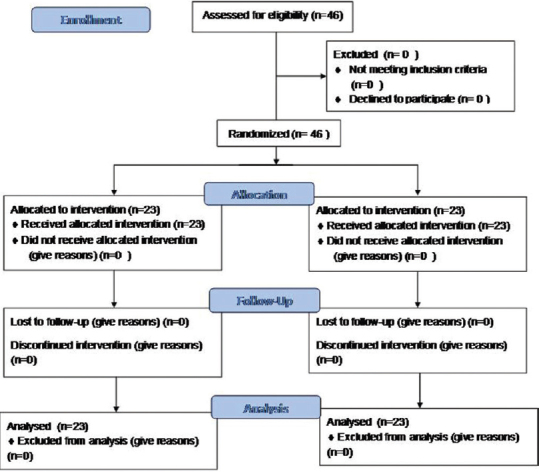

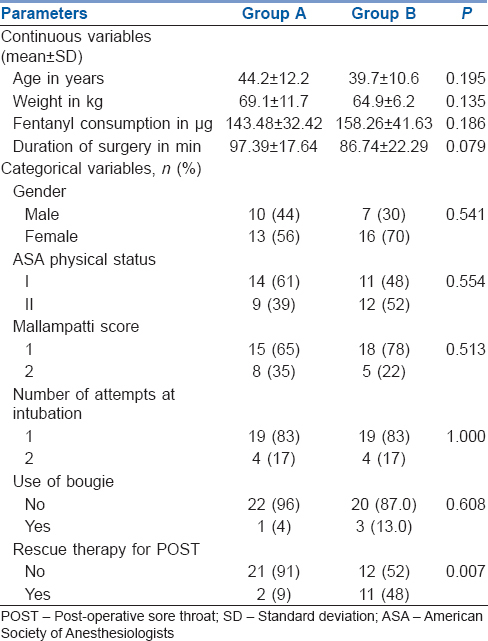

Forty-six patients were recruited in the present study [Figure 1]. Both groups were comparable with respect to mean age and weight, distribution of sex, ASA physical status and Mallampatti score. Nearly 82.6% of patients in group A and 78% in Group B were intubated in the first attempt whereas the rest required one more attempt which was comparable among the groups. Similarly, percentage of patients who were intubated over a bougie was similar among the groups. Both Group A and B had comparable duration of intubation as well as intra-operative fentanyl consumption [Table 2].

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram. n = number

Table 2.

Comparison of demographic profile, opioid consumption, duration of surgery and categorical variables

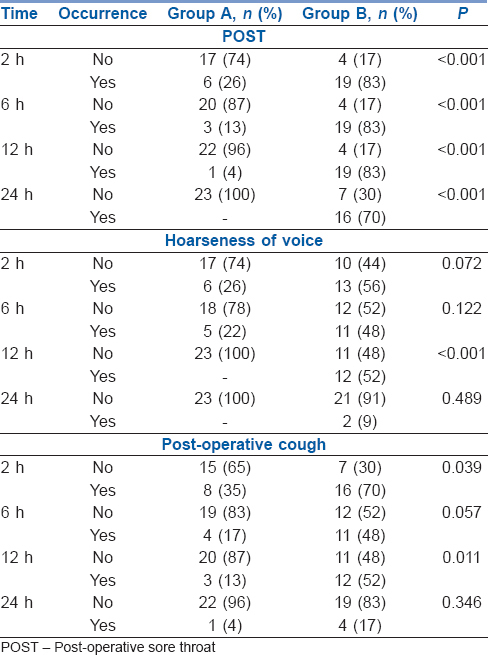

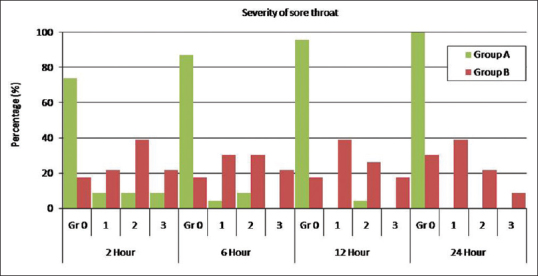

POST, cough and hoarseness of voice were assessed at 2, 6, 12 and 24 h based on the scales described in Table 1. Compared to Group B, the number of patients who had POST was significantly lower in Group A at 2, 6, 12 and 24 h (P < 0.001). Although more patients in Group B had post-operative hoarseness of voice and cough at all-time points, the difference was statistically significant only at 12 h and 24 h for post-operative hoarseness and at 2 h and 12 h for post-operative cough [Table 3]. The severity as well as the incidence of POST showed a downward trend in both groups with time and by 24 h no patient in Group A had sore throat. In Group B, 31% had no sore throat at 24 h [Figure 2].

Table 3.

Comparison of incidence of post-operative sore throat, cough and hoarseness of voice

Figure 2.

Severity of postoperative sore throat. Gr = Grade

A similar trend as with POST was seen with hoarseness of voice and cough too. From 12 h onward no patient in Group A had hoarseness of voice while 9% continued to have grade1 symptoms even at 24 h in Group B. 4% in Group A and 17% in Group B continued to have post-operative cough at 24 h. Significantly more number of patients in Group B required rescue therapy for POST (48% vs. 9%, P = 0.007).

DISCUSSION

Although considered as a minor self-limiting complication, POST accounts for one of the major reasons of patient dissatisfaction and delay in discharge following ambulatory surgery.[6] It results from an aseptic inflammatory process caused by irritation of the pharyngeal mucosa during laryngoscopy, and tracheal mucosa due to endotracheal tube cuff. Trauma during laryngoscopy and intubation is another major contributing factor.[7,8,9]

In the present study, we used a metered dose inhaler to deliver the test drug. Most of the studies which investigated the efficacy of various drugs on the incidence of POST have administered the drugs either intravenously, topically, as intracuff medication, nebulisation or gargle. Topical benzydamine hydrochloride.[10] intracuff[11] and topical lidocaine,[12] magnesium sulfate gargle,[13,14] nebulisations of ketamine and magnesium sulfate[15] are few examples.

Although most modalities were found to be effective, these drugs could result in the development of unwanted side effects. Use of drugs like ketamine can have adverse effects on haemodynamics or on central nervous system. As intracuff lidocaine diffuses out, though the chance of POST is reduced, the possibility of hoarseness increases due to nerve paresis. Higher doses of drugs are required when used intravenously as compared to topical administration and hence the chance of development of side effects increases. Gargling as a route of drug administration may not be acceptable for all patients.

Usually following a difficult intubation, administration of steroids and/or nebulised adrenaline is considered as the first line of management anticipating airway oedema.[16] Intravenous hydrocortisone or dexamethasone is usually preferred for this purpose. Steroids when given prophylactically act through their anti-inflammatory action by inhibition of leukocyte migration to the inflammation site and inhibition of release of cytokines by maintaining cellular integrity and by inhibition of fibroblast proliferation.[3,7,17,18] It had been shown that both topical as well as intravenous dexamethasone reduced the incidence of POST.[19,20,21,22] However side effects such as fluid retention, delayed wound healing and glucose intolerance are concerns with the use of intravenous steroids.

The advantage of using the inhaled route is that the total dose administered is minimal, at the same time the maximum concentration of the drug is made available at the site of action, thereby reducing the magnitude of side effects. Budesonide is a corticosteroid with potent glucocorticoid and weak mineralocorticoid activities. As one of the most commonly used inhaled glucocorticoids which decreases airway hyperactivity, it is being extensively used in the management of bronchial asthma.[23] It acts by reducing the number of inflammatory cells and mediators present in the airways, exhibits potent local anti-inflammatory activity with limited systemic exposure. Its usefulness in prevention of POST had been investigated with promising results when administered before induction of anaesthesia through oxygen driven atomising inhalation.[5] The dose of budesonide used in our study was well within the therapeutic limits used in bronchial asthma. Since for each patient, it was used only twice, 6 h apart, chance of overdosing or development of side effects were minimal.

Hoarseness of voice and cough are symptoms very often associated with POST. Use of larger-sized endotracheal tubes and laryngeal trauma are considered to be the common reasons for post-operative cough.[24] Although hoarseness of voice is common after intubation, prolonged hoarseness is very rare. Usually, it settles by the third post-operative day, the duration of which is decided by the age of patient and duration of intubation. The cause of prolonged hoarseness is usually arytenoid cartilage dislocation.[24] Use of smaller-sized tubes and periodic measurement of cuff pressure greatly reduce mucosal damage and thereby hoarseness.[24]

In the present study, we have not used the same metered dose inhaler for multiple patients considering the chance of cross infection. It may be reused after wiping the mouthpiece with sterile alcohol pad, which is then inserted into an aerosol cloud enhancer spacer with a one-way valve. However, the spacer should not be used for multiple patients.[25]

One of the strong points of our study was that all the intubations in our study were performed by a single anaesthetist which eliminated subjective variations due to differences in experience. We recruited patients who were undergoing short laparoscopic surgeries like laparoscopic sterilisation or diagnostic pelvic laparoscopy as post-operative pain following these procedures would be minimal, and hence, incidence and severity of POST would be better appreciated.

Compared to open surgeries, patients who undergo laparoscopic surgeries have a high incidence of POST as endotracheal tube cuff pressure increases due to pneumoperitoneum and Trendelenburg position[26,27] and degree of table tilt is proportional to the incidence of POST. The degree of table tilt used in our study was restricted to 15°–20° as we recruited patients undergoing pelvic laparoscopic surgeries only and hence, degree of Trendelenburg in both groups were comparable.

One of the limitations of the study was that it was conducted as an unblinded study. Delivery of the drug to the site of action was solely dependent on patient effort and hence might not have been uniform and accurate in all patients. Although sex distribution was comparable in both groups, the majority of the patient population comprised of females.

CONCLUSION

Inhaled budesonide suspension, administered as a 200 μg dose before induction of anaesthesia using a metered dose inhaler, was effective in significantly reducing the incidence and severity of POST, hoarseness of voice and cough seen in patients following endotracheal intubation.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Park SY, Kim SH, Lee SJ, Chae WS, Jin HC, Lee JS, et al. Application of triamcinolone acetonide paste to the endotracheal tube reduces postoperative sore throat: A Randomized controlled trial. Can J Anaesth. 2011;58:436–42. doi: 10.1007/s12630-011-9478-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thomas S, Beevi S. Dexamethasone reduces the severity of postoperative sore throat. Can J Anaesth. 2007;54:897–901. doi: 10.1007/BF03026793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scuderi PE. Postoperative sore throat: More answers than questions. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:831–2. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181ee85c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hung NK, Wu CT, Chan SM, Lu CH, Huang YS, Yeh CC, et al. Effect on postoperative sore throat of spraying the endotracheal tube cuff with benzydamine hydrochloride, 10% lidocaine, and 2% lidocaine. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:882–6. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181d4854e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen YQ, Li JP, Xiao J. Prophylactic effectiveness of budesonide inhalation in reducing postoperative throat complaints. Eur Arch Otorhinolaryngol. 2014;271:1667–72. doi: 10.1007/s00405-014-2896-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Higgins PP, Chung F, Mezei G. Postoperative sore throat after ambulatory surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2002;88:582–4. doi: 10.1093/bja/88.4.582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Park SH, Hang SH, Do SH, Kim JW, Rhee KY, Kim JH. Prophylactic dexamathasone decreases the incidence of sore throat and hoarseness after tracheal extubation with a double lumen endotracheal tube. Anesth Analg. 2008;107:1814–8. doi: 10.1213/ane.0b013e318185d093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Huang YS, Hung NK, Lee MS, Kuo CP, Yu JC, Huang GS, et al. The effectiveness of benzydamine hydrochloride spraying on the endotracheal tube cuff or oral mucosa for postoperative sore throat. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:887–91. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181e6d82a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rudra A, Ray S, Chatterjee S, Ahmed A, Ghosh S. Gargling with ketamine attenuates the postoperative sore throat. Indian J Anaesth. 2009;53:40–3. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen CY, Kuo CJ, Lee YW, Lam F, Tam KW. Benzydamine hydrochloride on postoperative sore throat: A meta-analysis of Randomized controlled trials. Can J Anaesth. 2014;61:220–8. doi: 10.1007/s12630-013-0080-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lam F, Lin YC, Tsai HC, Chen TL, Tam KW, Chen CY, et al. Effect of intracuff lidocaine on postoperative sore throat and the emergence phenomenon: A systematic review and meta-analysis of Randomized controlled trials. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0136184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0136184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bousselmi R, Lebbi MA, Bargaoui A, Ben Romdhane M, Messaoudi A, Ben Gabsia A, et al. Lidocaine reduces endotracheal tube associated side effects when instilled over the glottis but not when used to inflate the cuff: A double blind, placebo-controlled, randomized trial. Tunis Med. 2014;92:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chattopadhyay S, Das A, Nandy S, RoyBasunia S, Mitra T, Halder PS, et al. Postoperative sore throat prevention in ambulatory surgery: A comparison between preoperative aspirin and magnesium sulfate gargle – A prospective, Randomized, double-blind study. Anesth Essays Res. 2017;11:94–100. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.186602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Teymourian H, Mohajerani SA, Farahbod A. Magnesium and ketamine gargle and postoperative sore throat. Anesth Pain Med. 2015;5:e22367. doi: 10.5812/aapm.5(3)2015.22367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rajan S, Malayil GJ, Varghese R, Kumar L. Comparison of usefulness of ketamine and magnesium sulfate nebulizations for attenuating postoperative sore throat, hoarseness of voice, and cough. Anesth Essays Res. 2017;11:287–93. doi: 10.4103/0259-1162.181427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myatra SN, Shah A, Kundra P, Patwa A, Ramkumar V, Divatia JV, et al. All India Difficult Airway Association 2016 guidelines for the management of unanticipated difficult tracheal intubation in adults. Indian J Anaesth. 2016;60:885–98. doi: 10.4103/0019-5049.195481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canbay O, Celebi N, Sahin A, Celiker V, Ozgen S, Aypar U, et al. Ketamine gargle for attenuating postoperative sore throat. Br J Anaesth. 2008;100:490–3. doi: 10.1093/bja/aen023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu J, Zhang X, Gong W, Li S, Wang F, Fu S, et al. Correlations between controlled endotracheal tube cuff pressure and postprocedural complications: A multicenter study. Anesth Analg. 2010;111:1133–7. doi: 10.1213/ANE.0b013e3181f2ecc7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee JH, Kim SB, Lee W, Ki S, Kim MH, Cho K, et al. Effects of topical dexamethasone in postoperative sore throat. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2017;70:58–63. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2017.70.1.58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sun L, Guo R, Sun L. Dexamethasone for preventing postoperative sore throat: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Ir J Med Sci. 2014;183:593–600. doi: 10.1007/s11845-013-1057-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhao X, Cao X, Li Q. Dexamethasone for the prevention of postoperative sore throat: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Anesth. 2015;27:45–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2014.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bagchi D, Mandal MC, Das S, Sahoo T, Basu SR, Sarkar S, et al. Efficacy of intravenous dexamethasone to reduce incidence of postoperative sore throat: A prospective randomized controlled trial. J Anaesthesiol Clin Pharmacol. 2012;28:477–80. doi: 10.4103/0970-9185.101920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Szefler SJ. Pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics of budesonide: A new nebulized corticosteroid. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1999;104:175–83. doi: 10.1016/s0091-6749(99)70059-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yamanaka H, Hayashi Y, Watanabe Y, Uematu H, Mashimo T. Prolonged hoarseness and arytenoid cartilage dislocation after tracheal intubation. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:452–5. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Grissinger M. Shared metered dose inhalers among multiple patients: Can cross-contamination be avoided? P T. 2013;38:434–42. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yildirim ZB, Uzunkoy A, Cigdem A, Ganidagli S, Ozgonul A. Changes in cuff pressure of endotracheal tube during laparoscopic and open abdominal surgery. Surg Endosc. 2012;26:398–401. doi: 10.1007/s00464-011-1886-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Geng G, Hu J, Huang S. The effect of endotracheal tube cuff pressure change during gynecological laparoscopic surgery on postoperative sore throat: A control study. J Clin Monit Comput. 2015;29:141–4. doi: 10.1007/s10877-014-9578-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]