Abstract

Background:

As patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) require lifelong treatment, optimization of therapy with respect to efficacy and safety is needed to limit long-term disease progression. Patients with MS also need a range of health-related services. Satisfaction with these as well as treatment is clinically relevant because satisfied patients are more likely to adhere to therapy. The aim of this study was to determine the status of patient satisfaction and of healthcare services in 70 specialized MS centres in Germany.

Methods:

In 2011, patients with MS responded to a questionnaire, which solicited clinical and demographic information, as well as patients’ perceptions of their overall situation and their satisfaction with treatment.

Results:

Of 2791 patients surveyed, 81.9% had relapsing-remitting MS with mild disability [mean (standard deviation) Expanded Disability Status Scale score: 2.6 (1.8)]. Disease activity data were collected from 2205 patients, of whom 57.6% had remained relapse-free during the preceding 12 months. However, 38.9% had experienced one or more relapses, most of whom (67.3%) while receiving immunomodulatory treatment. About one-third of the patients indicated that they were more dissatisfied with their overall situation compared with the time before diagnosis. However, many patients (58.3%) were satisfied with their existing medication. Overall, 72.8% of patients would prefer oral to injectable treatments, assuming there was no difference in their efficacy.

Conclusions:

A substantial proportion of patients experienced breakthrough disease on treatment and may potentially benefit from a change of therapy. Although largely satisfied with treatment, most patients with MS would choose oral over injectable treatments.

Keywords: disease activity, immunomodulatory treatment, multiple sclerosis, patient satisfaction, treatment adherence

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic neurodegenerative disorder characterized by inflammation and progressive neurological destruction and degeneration.1 The disease is associated with a wide range of symptoms including motor, sensory, and cognitive impairments, which lead to gradual worsening of disability.1,2 Although chronic and incurable, MS has only a limited effect on life expectancy,3 so patients with MS require long-term treatment and this places a significant burden on healthcare resources in terms of time and cost. Both specialized care from an attending physician and suitable healthcare infrastructure are needed to support effective long-term treatment. Also, monitoring of each patient’s treatment response, based on clinical events and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings, is needed to ensure that patients with breakthrough disease are identified early, so that therapy can be changed to reduce the risk of further disease progression.4,5

It is clinically relevant to evaluate the extent to which patients with MS are satisfied with treatment, with healthcare services, and with the disease-related information they receive6 because satisfied patients are more likely both to comply with therapy7 and to participate actively in managing their disease.8 Promoting a high level of patient satisfaction is therefore desirable to ensure the best clinical outcomes. Also, healthcare professionals’ perceptions of patient status, including physical disability and health-related quality of life, may differ from those perceived by the patient.9,10 Thus, it is important to understand patients’ perspectives when trying to improve the quality of treatment and of healthcare services.11

The impact of dissatisfaction with treatment on adherence is of particular concern among patients with MS.12 For instance, it has been demonstrated that when patients adhere to therapy in the long-term, relapse rates can be reduced and functional and cognitive abilities and quality of life can be enhanced.6,13,14 However, two factors may constrain adherence to MS therapy. First, extended periods when significant symptoms do not occur may cause patients to question the need for long-term treatment.15 It is, therefore, important to provide patients with reliable information that allows them to understand their prognosis, subclinical disease progression and the benefit of persisting with treatment.16 Secondly, many disease-modifying drugs require frequent parenteral administration, predominantly by self-injection. Anxiety about self-injection, and injection-site disorders may lead to treatment interruption or discontinuation.6,17,18

Patients with MS not only require specialized treatment, but also reliable long-term care measures and health-related services. Beyond assessment of treatment satisfaction, analysis of patient satisfaction needs to consider factors such as a patient’s overall satisfaction with their physical, mental, social and occupational status; their perceived needs concerning health-related services; and their expectations for further treatment. To meet the various needs of patients with MS, specialized centres have been established in Germany that offer a comprehensive approach to MS healthcare. In addition to treatment, these centres offer educational programmes to improve patient understanding of the condition, and of the need for adherence to, and the potential benefits of treatment. Specialist MS nurses also attend these centres to provide information on support services and to advise patients on the management of disease symptoms and of adverse effects associated with treatment.

The survey reported here was conducted in 2011, when fewer disease-modifying therapies were licensed and the first oral disease-modifying therapy in MS [fingolimod (Gilenya®), Novartis Pharma AG, Basel, Switzerland] had only just been approved. The aim of the survey was to evaluate the status of patient satisfaction and the healthcare situation in 70 specialized MS centres in Germany. Data were obtained by questionnaires that recorded clinical data as well as treatment satisfaction and patients’ perceptions of their overall situation. The rate and reasons for treatment discontinuation were also examined, and patients were asked through questionnaires about their perception of unmet needs in the ongoing development of MS drugs.

Methods

Participants and procedures

This anonymous, cross-sectional survey was conducted in 70 specialized MS centres in Germany between March and June 2011. Patients were eligible if they were diagnosed with ‘clinically definite’ MS,19 and if informed consent was given (n = 2791). Data were collected using questionnaires designed specifically for the survey, and that had been tested in a pilot study conducted between October 2010 and February 2011. Questionnaires were completed either during routine clinic visits or during specially arranged appointments.

Questionnaire

Demographic data and clinical characteristics were collected retrospectively. Demographic data comprised age, sex, occupational status, and marital status. Clinical characteristics included onset of disease, duration of disease and treatment, and MS subtypes [clinically isolated syndrome (CIS), relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), secondary progressive MS (SPMS), primary progressive MS (PPMS)]. Disability was scored using Kurtzke’s Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS).20 In addition, information was collected about patients’ most recent MRI investigations (number of lesions in T2-weighted MRI) and about the number and severity of relapses in the preceding 12 months.

Questions on perceived needs and satisfaction were answered by patients in the presence of a health professional. This patient-directed part of the questionnaire included: one question on whether treatment was eventually discontinued or interrupted; five multiple choice questions to rate the advantages and disadvantages of their current medication, their reasons for treatment discontinuation, their preferred way of obtaining information, and the frequency with which information was obtained; and six items listing several statements about which patients were asked to indicate their level of agreement using a pivoted 5-point Likert scale (1, strongly agree; 2, agree; 3, neither agree nor disagree; 4, disagree; 5, strongly disagree). These statements focused on patients’ satisfaction with their current situation and medication as well as their perceived needs for improvements in therapy.

Statistics

Questionnaire data were reported descriptively and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD) or as the percentage of participants. The top-two-box score refers to the percentage of patients who awarded an agreement score of 1 or 2 when asked to give their level of agreement with a statement using the Likert scale. Patients were also stratified based on their preferred drug administration route. Comparisons between groups of patients were performed by a Student’s t test. The Chi-square test was used to assess statistical differences among categorical variables. A p-value ⩽0.05 was considered significant. The statistical analyses were performed with GESS tabs 4.0 (Gesellschaft für Software in der Sozialforschung mbH, Hamburg, Germany).

Results

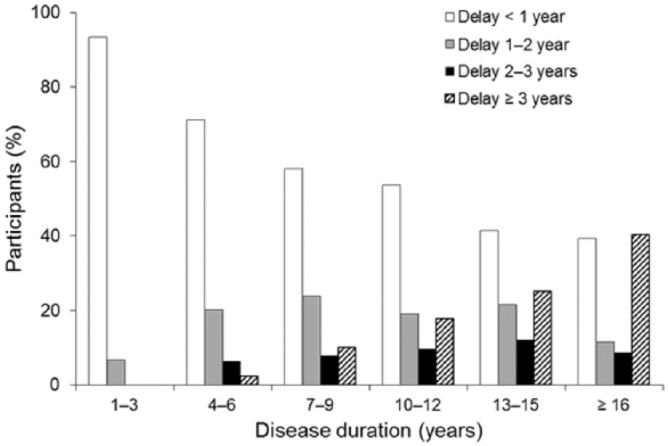

A total of 2791 patients participated in the survey; demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in Table 1. In 71% of patients, MS was diagnosed within 2 years of the onset of symptoms and the duration of diagnostic delay tended to increase with disease duration (Figure 1). Overall treatment duration was 2 years or less in 27.1% of patients, 3–5 years in 26.4%, and 6 years or more in 42.8%. The duration of current therapy was 2 years or less in 44.2% of patients, 3–5 years in 27.4% and 6 years or more in 22.7%. Most patients had T2 lesions (no lesions, 4.6%; 1–8 lesions, 33.9%; >8 lesions, 61.5%) with an average T2 lesion load of 11.8 (Table 2) at the most recent MRI scan (performed <1 year ago in 61.4% of patients). Overall, 38.9% of patients had a relapse in the preceding year (Table 2). For 65.9% (n = 380) of the patients who relapsed while on therapy, information on T2 lesion count was available. Almost all had T2 lesions (<9 lesions: 28.4%; ⩾9 lesions: 70.6%).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of participants.

| Total | CIS | RRMS | SPMS/PPMS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with MS (N) | 2791 | 49 | 2285 | 370 |

| Women (%) | 72.5 | 87.8 | 72.7 | 69.5 |

| Age, years (mean ± SD) | 41.4 ± 11.0 | 33.4 ± 10.3 | 40.0 ± 10.5 | 50.5 ± 9.2 |

| Married/ living with a partner (%) | 73.0 | 63.3 | 73.7 | 70.3 |

| Employed (%) | 55.2 | 57.1 | 60.7 | 23.5 |

| Time from symptom onset to diagnosis, years (mean ± SD) | 1.7 ± 3.8 | 0.7 ± 3.4 | 1.6 ± 3.5 | 2.9 ± 5.2 |

| MS subtypes | ||||

| RRMS (%) | 81.9 | – | 100 | – |

| SPMS (%) | 11.7 | – | – | 88.1 |

| CIS (%) | 1.8 | 100 | – | – |

| PPMS (%) | 1.6 | – | – | 11.9 |

| Disability status | ||||

| EDSS-score (mean ± SD) | 2.6 ± 1.8 | 1.0 ± 0.8 | 2.2 ± 1.5 | 5.0 ± 1.8 |

| EDSS-score 0.0–2.0 (%) | 50.2 | 91.8 | 57.1 | 7.8 |

| EDSS-score 2.5–4.0 (%) | 25.9 | 4.1 | 26.9 | 23.7 |

| EDSS-score 4.5–5.0 (%) | 5.7 | 0 | 4.2 | 15.9 |

| EDSS-score ⩾ 5.5 (%) | 10.0 | 0 | 5.0 | 43.5 |

CIS, clinically isolated syndrome; EDSS, expanded disability status scale; MS, multiple sclerosis; PPMS, primary progressive MS; RRMS, relapsing–remitting MS; SD, standard deviation; SPMS, secondary progressive MS.

Figure 1.

Duration of diagnostic delay versus disease duration (N = 2736).

Table 2.

Disease progression data (T2-weighted MRI lesion number, and relapse number and severity).

| Total | CIS | RRMS | SPMS/PPMS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients with MS (n) | 2205 | 33 | 1838 | 274 |

| MRI | ||||

| Most recent MRI (date ± SD years) | 2009.4 ± 2.1 | 2008.3 ± 8.8 | 2009.6 ± 1.7 | 2008.7 ± 2.5 |

| Number of T2 lesions (mean ± SD) | 11.8 ± 10.0 | 7.7 ± 5.6 | 11.6 ± 9.5 | 13.9 ± 13.4 |

| Patients with Gd-enhancing lesions at last scan (%) | 22.4 | 33.3 | 22.9 | 18.2 |

| MS relapse | ||||

| Relapse in the last 12 months (%) (n = 857) | 38.9 | 60.6 | 40.4 | 27.8 |

| Relapse under immunomodulatory therapy (%) (n = 557) | 30.4 | 3.0 | 32.5 | 20.8 |

| Number of relapses within previous year (mean ± SD) | 0.6 ± 1.1 | 0.8 ± 0.7 | 0.6 ± 1.1 | 0.4 ± 0.9 |

| Complete or almost complete remission (%) | 60.0 | 72.7 | 65.8 | 20.1 |

| Partial or minor remission (%) | 23.2 | 18.2 | 19.8 | 47.1 |

| Ongoing relapse or no remission (%) | 4.2 | 6.0 | 3.3 | 9.8 |

| Signs of disability progression | ||||

| Yes (%) | 20.1 | 6.1 | 14.4 | 59.9 |

| No (%) | 72.7 | 84.8 | 79.2 | 29.9 |

CIS, clinically isolated syndrome; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MS, multiple sclerosis; PPMS, primary progressive MS; RRMS, relapsing–remitting MS; SD, standard deviation; SPMS, secondary progressive MS.

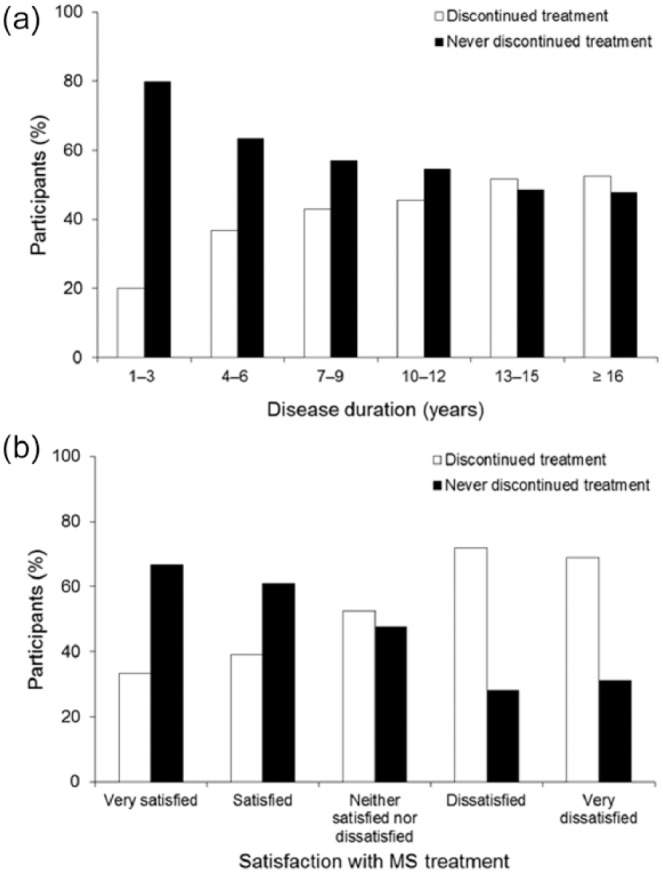

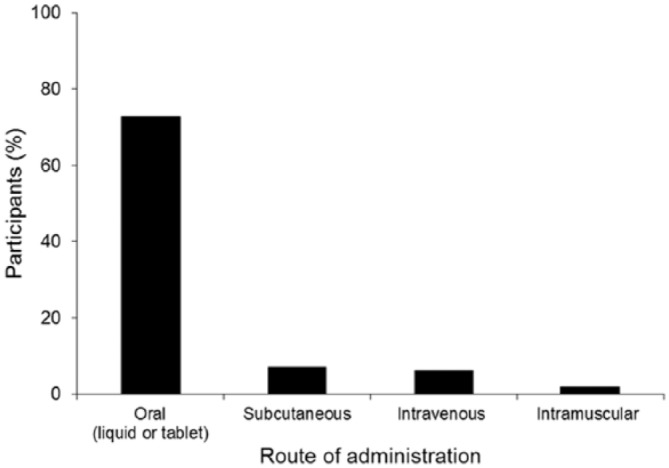

About one-third of the patients reported negative impact of the disease on their lives (Table 3). In total, 58.3% of the patients reported to be satisfied or very satisfied with their therapy (Table 4). However, 43.2% of patients reported having discontinued or interrupted therapy at least once. Treatment discontinuation occurred more frequently in patients with longer disease duration and in patients who reported being rather dissatisfied with the efficacy of their MS medication than in other groups (Figure 2). Reasons reported for discontinuation were general side effects (57.5%), injection-site reactions (38.7%), insufficient efficacy (32.6%), and complex administration (19.1%). Ideal requirements of MS treatment from the patients’ perspective are summarized in Table 5. Based on an assumption that all new medications are equally effective, the majority of patients indicated that their first-choice route of administration would be oral (72.8%), with few ranking subcutaneous, intravenous or intramuscular administration as preferred routes (Figure 3). For oral administration, patients indicated that tablets and capsules were preferred to liquid drug forms (54.5% versus 18.3%, respectively). Baseline demographic and disease characteristics were similar in the group of patients who ranked oral administration as a very important improvement (n = 651) and in the group that ranked it as unimportant or very unimportant (n = 332). Comfortable use was ranked far more important among patients who considered oral administration important (Table 6) and injection-site reactions and complexity of administration were more frequently perceived as disadvantage in this group (Table 7). Other subgroup analyses (geographic variables, MS subtypes) revealed no differences in patient satisfaction. The preferred source of information for MS patients is a physician/neurologist (Table 8).

Table 3.

Patients’ perception of their overall situation and functional impairments, patients who scored top-two boxes (%)a (N = 2791).

| Statement | Total | CIS | RRMS | SPMS/PPMS |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| My daily life is affected by MS | 35.3 | 18.4 | 29.9 | 71.9 |

| My professional life is affected by MS | 35.7 | 20.4 | 31.9 | 61.9 |

| My physical activity is affected by MS | 40.9 | 20.4 | 35.4 | 78.9 |

| I suffer from premature fatigue | 47.1 | 26.5 | 44.4 | 65.7 |

| I have difficulties in concentrating | 33.9 | 24.5 | 31.5 | 47.8 |

| I suffer from mood swings and depression | 29.3 | 20.4 | 27.7 | 39.2 |

| I am more dissatisfied than before MS diagnosis | ||||

| With my overall situation | 27.2 | 18.4 | 23.8 | 48.9 |

| With my physical situation | 35.9 | 18.4 | 31.2 | 65.7 |

| With my mental situation | 28.1 | 16.3 | 26.3 | 40.5 |

| With my occupational situation | 28.4 | 12.2 | 25.9 | 46.5 |

| With my social situation | 19.6 | 8.2 | 17.7 | 32.7 |

Data are based on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 = ‘strongly agree’, 2 = ‘agree’, 3 = ‘neither agree nor disagree’, 4 = ‘disagree’, and 5 = ‘strongly disagree’.

Top-two box score refers to the percentage of patients (N = 2791) who scored a 1 or a 2.

CIS, clinically isolated syndrome; MS, multiple sclerosis; PPMS, primary progressive MS; RRMS, relapsing–remitting MS; SD, standard deviation; SPMS, secondary progressive MS.

Table 4.

Patients’ satisfaction with efficacy and tolerability of the MS medication (N = 2791).

| Rating score | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | No response |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | ||||||

| Efficacy (%) | 22.5 | 35.8 | 25.3 | 7.9 | 2.8 | 5.8 |

| Tolerability (%) | 21.9 | 36.4 | 25.5 | 8.4 | 2.4 | 5.3 |

| CIS | ||||||

| Efficacy (%) | 36.7 | 28.6 | 20.4 | 4.1 | 2.0 | 8.2 |

| Tolerability (%) | 22.4 | 38.8 | 18.4 | 8.2 | – | 12.2 |

| RRMS | ||||||

| Efficacy (%) | 23.6 | 38.2 | 24.4 | 6.5 | 1.8 | 5.6 |

| Tolerability (%) | 22.5 | 37.5 | 25.1 | 7.8 | 2.3 | 4.8 |

| SPMS/PPMS | ||||||

| Efficacy (%) | 11.4 | 22.7 | 31.6 | 18.1 | 8.9 | 7.3 |

| Tolerability (%) | 16.5 | 28.6 | 31.4 | 12.7 | 3.2 | 7.6 |

Values are expressed as the percentage of patients who reported each level of satisfaction with the efficacy and tolerability of their MS medication. Patients rated their scores on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 = ‘very satisfied’, 2 = ‘satisfied’, 3 = ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’, 4 = ‘slightly dissatisfied’, and 5 = ‘very dissatisfied.

CIS, clinically isolated syndrome; MS, multiple sclerosis; PPMS, primary progressive MS; RRMS, relapsing–remitting MS; SPMS, secondary progressive MS.

Figure 2.

Treatment discontinuation frequency versus (a) disease duration (N = 2736) and (b) satisfaction with medication efficacy (N = 2577).

Satisfaction was rated on a five-point pivoted Likert scale, in which 1 = ‘very satisfied’, 2 = ‘satisfied’, 3 = ‘neither satisfied nor dissatisfied’, 4 = ‘slightly dissatisfied’, and 5 = ‘very dissatisfied).

Table 5.

Ideal requirements of a new MS treatment, patients who scored top-two boxes (%)a (N = 2791).

| Total | CIS | RRMS | SPMS/PPMS | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reduction of relapses | 91.7 | 91.8 | 94.0 | 78.9 |

| Prevention of health status deterioration | 93.1 | 91.8 | 93.3 | 93.5 |

| Fewer side effects | 85.8 | 79.6 | 86.6 | 82.7 |

| Reduced inflammatory activity in MRI | 85.2 | 89.8 | 86.7 | 76.2 |

| Safe use | 84.8 | 83.7 | 85.6 | 80.8 |

| Comfortable use | 78.9 | 71.4 | 80.0 | 73.0 |

| Reduction of everyday problems | 78.4 | 83.7 | 77.9 | 81.1 |

| Possibility of long-term therapy (>8 years) | 76.3 | 61.2 | 78.0 | 70.0 |

| Oral administration | 65.9 | 67.3 | 67.3 | 59.2 |

| Regular intake | 61.6 | 61.2 | 62.1 | 57.3 |

Data are based on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 = ‘very important’, 2 = ‘important’, 3 = ‘neither important or unimportant’, 4 = ‘unimportant’, and 5 = ‘very unimportant’.

Top-two box score refers to the percentage of patients (N = 2791) who scored each criterion a 1 or a 2.

CIS, clinically isolated syndrome; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; MS, multiple sclerosis; PPMS, primary progressive MS; RRMS, relapsing–remitting MS; SPMS, secondary progressive MS.

Figure 3.

Preferred route of administration (N = 2791).

The graph depicts the proportion of patients who rated each route of administration for a new MS medication as their first choice on a scale of 1–5, where 1 represented the patient’s first choice and 5 their last choice. Equal efficacy of the MS preparations was assumed.

MS, multiple sclerosis.

Table 6.

Requirements for future MS therapies stated by patients who preferred oral administration.

| Oral administration | Difference (p) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Importanta (n = 651) | Unimportantb (n = 332) | ||

| Reduction of relapses | 1.3 ± 0.7 | 1.2 ± 0.7 | NS |

| Prevention of health status deterioration | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 1.3 ± 0.7 | NS |

| Fewer side effects | 1.4 ± 0.9 | 1.8 ± 1.1 | <0.01 |

| Reduced inflammatory activity in MRI | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.6 ± 1.0 | <0.01 |

| Safe use | 1.4 ± 0.7 | 1.9 ± 1.2 | <0.01 |

| Comfortable use | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 2.4 ± 1.3 | <0.01 |

| Reduction of everyday problems | 1.9 ± 1.1 | 1.8 ± 1.1 | NS |

| Possibility of long-term therapy (>8 years) | 1.7 ± 1.0 | 2.1 ± 1.3 | <0.01 |

| Oral administration | 1.0 ± 0.0 | 4.5 ± 0.5 | <0.01 |

| Regular intake | 2.3 ± 1.3 | 2.7 ± 1.5 | <0.01 |

Data are expressed as mean ± SD and are based on a five-point Likert scale, where 1 = ‘very important’, 2 = ‘important’, 3 = ‘neither important or unimportant’, 4 = ‘unimportant’, and 5 = ‘very unimportant’.

Mean ± SD scores of patients who had ranked oral administration as very important.

Mean ± SD scores of patients who had ranked oral administration as unimportant or very unimportant.

MS, multiple sclerosis; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging; NS, not significant; SD, standard deviation.

Table 7.

Perceived disadvantages of currently used medications stated by patients who preferred oral administration (% responses).

| Oral administration | Difference (p) |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| Importanta (n = 651) | Unimportantb (n = 332) | ||

| Side effects | 51.9 | 50.0 | NS |

| Injection-site reactions | 51.0 | 41.0 | <0.01 |

| Complexity of administration | 33.9 | 20.2 | <0.01 |

| Insufficient efficacy | 20.1 | 22.9 | NS |

Percentage of responses from patients who had ranked oral administration as very important.

Percentage of responses from patients who had ranked oral administration as unimportant or very unimportant.

Multiple responses were possible.

NS, not significant.

Table 8.

Preferred source of information of patients with MS (N = 2791).

| Source of information | Survey participants (%) |

|---|---|

| Personal contacts | |

| Physician/neurologist | 94.6 |

| MS nurse | 52.8 |

| Family, partner, friends | 30.4 |

| Telephone hotline | 11.3 |

| Internet | |

| Internet (in general) | 64.3 |

| Homepage of the German multiple sclerosis society | 35.4 |

| Manufacturer’s homepage | 13.1 |

| Internet chatrooms | 11.5 |

| Manufacturer’s information | 36.5 |

| Newspaper | 35.0 |

| Books | 30.5 |

| Other | 15.2 |

MS, multiple sclerosis.

Discussion

In this large survey of approximately 2800 patients treated in specialized MS centres in Germany, more than half of patients had not experienced a relapse in the preceding year. However, more than one-third had relapsed during that time, many while receiving immunomodulatory treatment. The survey also identified that >20% of patients had MRI disease activity, that is Gd-enhancing lesions at their last scan. This situation might be improved by better monitoring to detect breakthrough disease, more timely treatment review, and a more individualized approach to treatment than was practised when this survey was conducted in 2011.21 Changes in the intervening period to Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie MS treatment guidelines, which now differentiate between mild, moderate and (highly) active forms of MS, suggest that practice is moving in this direction.22 The fact that treatment optimization has become more achievable accentuates the need to detect and address a suboptimal treatment response early and so minimize disease progression and long-term neurological damage.23

Over the last 5 years, assessment of MS worsening and progression has increasingly employed combination measures of clinical and MRI disease activity, with a shift towards using such measures to evaluate therapeutic effectiveness.24–27 Although these combination measures continue to evolve, their proliferation tends to support the notion that the MS community is increasingly accepting of the concept of treating to such optimized treatment goals.28 For therapy to be most effective it must also begin as early as possible, so it was encouraging that this study found an apparent reduction over time in the delay between symptom onset and diagnosis.

The survey identified a relatively high degree of patient satisfaction with the efficacy and tolerability of their existing medication. However, rates of treatment discontinuation were substantial (nearly half of patients had discontinued or interrupted therapy) and these rates increased with both disease duration and the level of dissatisfaction with therapy which is in line with Haase and colleagues.6 Discontinuation was mainly attributable to general side effects and injection-site reactions. Consistent with this, adverse effects such as flu-like symptoms29 and injection-site reactions30 have been reported as reasons for treatment discontinuation. In terms of adherence, most patients reported general side effects and, to a lesser degree, injection-site reactions and the complexity of administering therapy, as crucial factors. Disease-related factors, such as neuropsychological complications, can also impact adherence, and treatment of depression has been shown to increase adherence to interferon β-1b therapy.31 Fatigue was rated as the most burdensome symptom in this survey and as it has been identified as one of the most common adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation.15 Symptomatic treatment of fatigue should be targeted as a matter of clinical routine in MS.32

As well satisfaction with treatment, this survey explored what requirements patients would like to see fulfilled in MS therapies to guide their further development. Most patients stated that reduced relapse rates, delayed disease progression, less MRI inflammatory activity, and therapies suitable for long-term use would all be desirable. Such answers demonstrate how well-informed these patients were, both about their medical condition and about MS pathogenesis in general. As reported elsewhere,33 the internet was identified in this study as an important source of information for patients. However, participants identified their neurologist as a primary information source, which also tends to suggest a good physician-patient relationship.34 Notably, a recent study in MS patients identified the physician-patient relationship as important in influencing long-term treatment adherence.35

Studies of treatment adherence in MS have reported discontinuation rates ranging from 27% during the first 6 months of treatment 36 to 46% over a 4.2-year follow up.37 Notably, patients with RRMS who adhere to disease-modifying therapies have been shown to have a significantly better quality of life, fewer neuropsychological complications, and shorter duration of disease and treatment than nonadherent patients.13 It is difficult to quantify the relationship between adherence and MRI outcomes, but adherent patients probably experience greater benefit from treatment36 and may, therefore, be at lower risk for disease progression.

Among strategies being explored to improve adherence, oral drug administration has been very promising. This survey found that if new medications were equally effective, most patients would prefer oral to injectable therapy, and oral administration has been shown to be associated with higher levels of patient satisfaction than injectable therapies.38,39 A total of three oral MS treatments are now approved: fingolimod (Gilenya®),40 teriflunomide (Aubagio®),41 and dimethyl fumarate (Tecfidera®).42 After a switch from injectable therapy to fingolimod for example, patients reported an increase in treatment satisfaction.43 With respect to adherence, a recent analysis did not observe differences between oral medication and injectable disease-modifying therapies. However, this analysis was based on a 12-month period only, and only 10% of the patients included were on oral medication.44 Future studies will show to what extent oral drugs have a positive impact on long-term adherence in MS.

Negative expectations towards a therapy, for example the expectation of adverse drug effects, can trigger nocebo effects that affect adherence.45 Patient management thus needs to address patients’ expectations towards a therapy in order to increase adherence. Patients with somatoform disorder comorbidities like depression or anxiety disorders are often less adherent to medication than patients without these comorbidities. As such disorders are frequent in MS patients, their contribution to adherence needs to be considered. Adequate treatment of these comorbidities may increase adherence.46

In terms of patients’ levels of satisfaction with their overall situation and with different aspects of their lives, about one-third of participants were dissatisfied with their situation, compared with the time before diagnosis. Patients had also experienced impairments to both their daily and professional lives, and suffered from more restricted physical activity. Several studies have shown that patients with MS are rather dissatisfied with healthcare-related matters such as rehabilitation, coordination of services, availability of MS-related information,47–49 and their current situation in general.50 Consistent with this, about one-third of the participants in our study expressed dissatisfaction with different physical, psychological, and vocational aspects of their lives. Among patients with progressive forms of MS the proportion was higher than in the total population. The effect of MS on neurological and neuropsychiatric functions,51 the unpredictability of the disease course, and the relatively young age of patients at diagnosis all conspire to impact severely on patients’ personal development. It is perhaps unsurprising that patients with MS report lower levels of satisfaction with their lives than do healthy individuals52 or patients with other chronic diseases, such as inflammatory bowel disease, rheumatoid arthritis, and diabetes.53,54

Conclusion

Our survey aimed to assess satisfaction and the healthcare-related services of patients treated in specialized MS care centres in Germany and showed that patients were rather satisfied with the efficacy and tolerability of their existing medication, and with healthcare professionals in general. The survey did highlight some dissatisfaction among patients with aspects of their situation, and further studies could examine how this could be improved, based on how patient satisfaction in the cohort changes over time. The levels of disease breakthrough observed indicate that a substantial proportion of patients were also receiving suboptimal treatment, which should be possible to address given the increased number of treatment options available to patients with MS since the survey was conducted. Based on preferences expressed in this survey, treatment adherence may be more likely if patients with MS can choose oral instead of injectable therapies.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge Dr Jeremy Bright, Oxford PharmaGenesis Ltd., UK, and Dr Stefan Lang who provided editorial support. VB and VH designed the protocol and developed the survey. TZ, KS and HS analyzed and interpreted the patient data and were major contributors in writing the manuscripts. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Footnotes

Ethics approval and informed consent: According to the German Medicinal Products Act Article 4 (23) (Arzneimittelgesetz), ethics approval and written informed consent is mandatory for interventional clinical studies (Article 40). Further, according to the code of medical ethics (Ärztliche Berufsordnung), research in which data cannot be traced back to the individual does not require ethics approval. As the present survey does not fulfil the definition of an interventional study and no personal data were collected, ethics approval as well as written informed consent was not mandatory. Nevertheless, patients were informed by means of a written patient information leaflet about the intended use of their data, and data were only collected if patients agreed.

The datasets used and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Funding: The study as well as editorial support was funded by Novartis Pharma GmbH.

Conflict of interest statement: Veit Becker has received reimbursements for participation in scientific advisory boards and speaker honoraria from Merck, Biogen, Novartis Pharma AG, Genzyme, Sanofi. He received research support from Novartis Pharma AG, Merck and Teva.

Volker Heeschen, Katrin Schuh and Heinke Schieb are employees of Novartis Pharma GmbH.

Tjalf Ziemssen has received reimbursements for participation in scientific advisory boards from Bayer Healthcare, Biogen Idec, Novartis Pharma AG, Merck Serono, Teva, Genzyme, and Synthon. He has also received speaker honorarium from Bayer Healthcare, Biogen Idec, Genzyme, Merck Sharp & Dohme, GlaxoSmithKline, Novartis Pharma AG, Teva, Sanofi Aventis, and Almirall. He has also received research support from Bayer Healthcare, Biogen Idec, Genzyme, Novartis Pharma AG, Teva, and Sanofi Aventis.

Contributor Information

Veit Becker, Neurologische Praxis Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany.

Volker Heeschen, Novartis Pharma GmbH, Nuremberg, Germany.

Katrin Schuh, Novartis Pharma GmbH, Nuremberg, Germany.

Heinke Schieb, Novartis Pharma GmbH, Nuremberg, Germany.

Tjalf Ziemssen, Center of Clinical Neuroscience, University Clinic Carl Gustav Carus Dresden, Fetscherstraße 74, 01307 Dresden, Germany.

References

- 1. Keegan BM, Noseworthy JH. Multiple sclerosis. Annu Rev Med 2002; 53: 285–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Rao SM, Leo GJ, Bernardin L, et al. Cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. I. Frequency, patterns, and prediction. Neurology 1991; 41: 685–691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Weinshenker BG. Natural history of multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol 1994; 36(Suppl.): S6–S11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sormani MP, De Stefano N. Defining and scoring response to IFN-beta in multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Neurol 2013; 9: 504–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ziemssen T, De Stefano N, Pia Sormani M, et al. Optimizing therapy early in multiple sclerosis: an evidence-based view. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2015; 4: 460–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Haase R, Kullmann JS, Ziemssen T. Therapy satisfaction and adherence in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis: the THEPA-MS survey. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2016; 9: 250–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pascoe GC. Patient satisfaction in primary health care: a literature review and analysis. Eval Program Plann 1983; 6: 185–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Donabedian A. The quality of care. How can it be assessed? JAMA 1988; 260: 1743–1748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Rothwell PM, McDowell Z, Wong CK, et al. Doctors and patients don’t agree: cross-sectional study of patients’ and doctors’ perceptions and assessments of disability in multiple sclerosis. BMJ 1997; 314: 1580–1583. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kersten P, George S, McLellan L, et al. Disabled people and professionals differ in their perceptions of rehabilitation needs. J Public Health Med 2000; 22: 393–399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Sitzia J, Wood N. Patient satisfaction: a review of issues and concepts. Soc Sci Med 1997; 45: 1829–1843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kern S, Reichmann H, Ziemssen T. Adherence to neurologic treatment. Lessons from multiple sclerosis. Nervenarzt 2008; 79: 877–878, 880,–882, 884–886 passim. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Devonshire V, Lapierre Y, Macdonell R, et al. The Global Adherence Project (GAP): a multicenter observational study on adherence to disease-modifying therapies in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur J Neurol 2011; 18: 69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fraser C, Morgante L, Hadjimichael O, et al. A prospective study of adherence to glatiramer acetate in individuals with multiple sclerosis. J Neurosci Nurs 2004; 36: 120–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Costello K, Kennedy P, Scanzillo J. Recognizing nonadherence in patients with multiple sclerosis and maintaining treatment adherence in the long term. MedscapeJ Med 2008; 10: 225. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kopke S, Kern S, Ziemssen T, et al. Evidence-based patient information programme in early multiple sclerosis: a randomised controlled trial. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2014; 85: 411–418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mohr DC, Boudewyn AC, Likosky W, et al. Injectable medication for the treatment of multiple sclerosis: the influence of self-efficacy expectations and injection anxiety on adherence and ability to self-inject. Ann Behav Med 2001; 23: 125–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Utz KS, Hoog J, Wentrup A, et al. Patient preferences for disease-modifying drugs in multiple sclerosis therapy: a choice-based conjoint analysis. Ther Adv Neurol Disord 2014; 7: 263–275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Poser CM, Paty DW, Scheinberg L, et al. New diagnostic criteria for multiple sclerosis: guidelines for research protocols. Ann Neurol 1983; 13: 227–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kurtzke JF. Rating neurologic impairment in multiple sclerosis: an expanded disability status scale (EDSS). Neurology 1983; 33: 1444–1452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ziemssen T, Kern R, Thomas K. Multiple sclerosis: clinical profiling and data collection as prerequisite for personalized medicine approach. BMC Neurol 2016; 16: 124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Deutsche Gesellschaft für Neurologie. Diagnose und Therapie der Multiplen Sklerose (S2e Leitlinie; AWMF-Registernummer: 030/050), Januar 2012, Ergänzung August 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Ziemssen T, Derfuss T, de Stefano N, et al. Optimizing treatment success in multiple sclerosis. J Neurol 2016; 263: 1053–1065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Havrdova E, Galetta S, Hutchinson M, et al. Effect of natalizumab on clinical and radiological disease activity in multiple sclerosis: a retrospective analysis of the natalizumab safety and efficacy in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis (AFFIRM) study. Lancet Neurol 2009; 8: 254–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Giovannoni G, Cook S, Rammohan K, et al. Sustained disease-activity-free status in patients with relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis treated with cladribine tablets in the CLARITY study: a post-hoc and subgroup analysis. Lancet Neurol 2011; 10: 329–337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Radu EW, Bendfeldt K, Mueller-Lenke N, et al. Brain atrophy: an in-vivo measure of disease activity in multiple sclerosis. Swiss Med Wkly 2013; 143: w13887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. De Stefano N, Airas L, Grigoriadis N, et al. Clinical relevance of brain volume measures in multiple sclerosis. CNS Drugs 2014; 28: 147–156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Ziemssen T, Thomas K. Treatment optimisation in multiple sclerosis: how do we apply emerging evidence? Expert Rev Clin Immunol 2017; 13: 509–511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Bayas A, Rieckmann P. Managing the adverse effects of interferon beta therapy in multiple sclerosis. Drug Saf 2000; 22: 149–159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Mohr DC, Goodkin DE, Likosky W, et al. Therapeutic expectations of patients with multiple sclerosis upon initiating interferon beta-1b: relationship to adherence to treatment. Mult Scler 1996; 2: 222–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mohr DC, Goodkin DE, Likosky W, et al. Treatment of depression improves adherence to interferon beta-1b therapy for multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol 1997; 54: 531–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Ziemssen T. Multiple sclerosis beyond EDSS: depression and fatigue. J Neurol Sci 2009; 277(Suppl. 1): S37–S41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Haase R, Schultheiss T, Kempcke R, et al. Use and acceptance of electronic communication by patients with multiple sclerosis: a multicenter questionnaire study. J Med Internet Res 2012; 14: e135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lugaresi A, Ziemssen T, Oreja-Guevara C, et al. Improving patient-physician dialog: commentary on the results of the MS Choices survey. Patient Prefer Adherence 2012; 6: 143–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Koudriavtseva T, Onesti E, Pestalozza IF, et al. The importance of physician–patient relationship for improvement of adherence to long-term therapy: data of survey in a cohort of multiple sclerosis patients with mild and moderate disability. Neurol Sci 2012; 33: 575–584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Tremlett HL, Oger J. Interrupted therapy: stopping and switching of the beta-interferons prescribed for MS. Neurology 2003; 61: 551–554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Portaccio E, Zipoli V, Siracusa G, et al. Long-term adherence to interferon beta therapy in relapsing–remitting multiple sclerosis. Eur Neurol 2008; 59: 131–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Calkwood J, Cree B, Crayton H, et al. Impact of a switch to fingolimod versus staying on glatiramer acetate or beta-interferons on patient- and physician-reported outcomes in relapsing multiple sclerosis: post-hoc analyses of the EPOC trial. BMC Neurol 2014; 14: 220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Vermersch P, Czlonkowska A, Grimaldi LM, et al. Teriflunomide versus subcutaneous interferon beta-1a in patients with relapsing multiple sclerosis: a randomised, controlled phase 3 trial. Mult Scler 2014; 20: 705–716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Kappos L, Radue EW, O’Connor P, et al. ; FREEDOMS Study Group. A placebo-controlled trial of oral fingolimod in relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2010; 362: 387–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. O’Connor P, Wolinsky JS, Confavreux C, et al. Randomized trial of oral teriflunomide for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2011; 365: 1293–1303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Fox RJ, Miller DH, Phillips JT, et al. Placebo-controlled phase 3 study of oral BG-12 or glatiramer in multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med 2012; 367: 1087–1097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fox E, Edwards K, Burch G, et al. ; EPOC Study Investigators. Outcomes of switching directly to oral fingolimod from injectable therapies: results of the randomized, open-label, multicenter, Evaluate Patient OutComes (EPOC) study in relapsing multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler Relat Disord 2014; 3: 607–619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Burks J, Marshall TS, Ye X. Adherence to disease-modifying therapies and its impact on relapse, health resource utilization, and costs among patients with multiple sclerosis. Clinicoecon Outcomes Res 2017; 9: 251–260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Faasse K, Petrie KJ. The nocebo effect: patient expectations and medication side effects. Postgrad Med J 2013; 89: 540–546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Beiske AG, Svensson E, Sandanger I, et al. Depression and anxiety amongst multiple sclerosis patients. Eur J Neurol 2008; 15: 239–245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Gottberg K, Einarsson U, Ytterberg C, et al. Use of health care services and satisfaction with care in people with multiple sclerosis in Stockholm County: a population-based study. Mult Scler 2008; 14: 962–971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Forbes A, While A, Taylor M. What people with multiple sclerosis perceive to be important to meeting their needs. J Adv Nurs 2007; 58: 11–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Somerset M, Campbell R, Sharp DJ, et al. What do people with MS want and expect from health care services? Health Expect 2001; 4: 29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Bränholm IB, Erhardsson On life satisfaction and activity preferences in subjects with multiple sclerosis: a comparative study. Scand J Occup Ther 1994; 1: 17–23. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kern S, Schrempf W, Schneider H, et al. Neurological disability, psychological distress, and health-related quality of life in MS patients within the first three years after diagnosis. Mult Scler 2009; 15: 752–758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. McCabe MP, McKern S. Quality of life and multiple sclerosis: comparison between people with multiple sclerosis and people from the general population. J Clin Psychol Med Settings 2002; 9: 287–295. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rudick RA, Miller D, Clough JD, et al. Quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Comparison with inflammatory bowel disease and rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Neurol 1992; 49: 1237–1242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Hermann BP, Vickrey B, Hays RD, et al. A comparison of health-related quality of life in patients with epilepsy, diabetes and multiple sclerosis. Epilepsy Res 1996; 25: 113–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]