Abstract

A novel approach to data extraction and synthesis was used to explore the connections between research priorities, understanding and practice improvement associated with family bereavement in the context of the potential for organ donation. Conducting the review as a qualitative longitudinal study highlighted changes over time, and extraction of citation-related data facilitated an analysis of the interaction in this field. It was found that lack of ‘communication’ between researchers contributes to information being ‘lost’ and then later ‘rediscovered’. It is recommended that researchers should plan early for dissemination and practice improvement to ensure that research contributes to change.

Keywords: bereavement, dissemination, knowledge translation, methodology, mixed methods, narrative, novel synthesis, organ donation, research priorities, systematic review

Introduction

Following the first heart transplant in 1967, and the formalisation of the diagnosis of brain death (BD) in 1968, members of the public and medical professionals showed increased interest in the processes of organ donation and transplantation. Medical teams, researchers, journalists, families who donated organs and transplant recipients all sought to understand the impact of the new phenomena.

This response can be viewed through the lens of meaning-making, and post-mortem organ donation and transplantation can be seen as events that challenged the understanding of life, death and the boundaries of medical science. As described by Park (2010), in response to a disruption in their worldview, people respond by trying to make sense of new information and then attempting to determine its significance. By assimilating information into existing constructs or adjusting one’s worldview to accommodate the new experiences, a sense of meaningfulness can be restored.

Researchers explored this context and shared information about the bereavement of families of potential organ donors. This contributed to meaning-making, a narrative about family experiences, and practice improvement. Data describing the role of research and the evolution of research priorities were extracted from sources previously used during a systematic review of family bereavement (Dicks et al., 2017a). To show how understanding of family bereavement in this context developed over time, sources were ordered chronologically and analysed longitudinally.

Aims

The current review aims to determine what can be learned from the selected sources about the identification of research priorities, the conduct of research, dissemination of findings, theory development and practice improvement. In addition, methodological innovations are trialled to explore their utility as tools for use when conducting systematic reviews in general.

Method

Research questions

This article is organised into four sections exploring the following research questions:

Whom did researchers interact with, and how did this contribute to understanding of the bereavement of families of potential organ donors?

What topics are suggested for future research? What methods should be used to further understanding in this area?

What can be learned from the way findings have been shared?

What can be learned from the selected sources about the links between research, theory development and practice improvement?

Systematic literature search

An electronic search conducted on 4 December 2016 and hand-searching identified 120 sources that each provided information about family bereavement in the context of the potential for post-mortem organ donation. Details of this search and the narrative of family bereavement that emerged when sources were analysed have been described previously (Dicks et al., 2017a).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

As described by Dicks et al. (2017a), English sources published since 1968 referring to family bereavement in the context of a potential organ donation were included. Sources that do not comment on the bereavement of families of potential deceased organ donors were excluded. These excluded sources include those dealing with living organ donation, ways of increasing deceased donation rates, community awareness and medical aspects of the organ donation context. The search strategy also captured a number of sources that were out of the scope of this review, such as gamete donation, and these were excluded.

Of the 120 sources used by Dicks et al. (2017a), 40 were excluded before conducting the present analysis because they did not provide information about research priorities, methods, theory or practice improvement.

Data preparation

To facilitate comparison over time, as research priorities evolved in response to accumulated knowledge and social contexts, sources were initially sorted according to three almost equal time periods: 1968–1985, 1986–2000 and 2001–2017. However, as the number of papers published has increased dramatically over time (with 68% of sources being from the 2001–2017 period), it was considered more meaningful to split this final period producing four periods.

The final time period, T4, starts on 1 January 2011. After the systematic literature search was completed, email alerts were left active in order to identify any new publications that matched inclusion criteria. Taylor et al. (2017) was published in August 2017 and is included in the review. No sources were added after that.

The chosen time periods and number of sources used in this article per period are as follows: T1: 1968–1985 (n = 7), T2: 1986–2000 (n = 18), T3: 2001–2010 (n = 30) and T4: 2011–2017 (n = 25).

Data extraction

For each period, content relevant to research and practice was extracted. This included data related to identification of gaps in the field, research priorities, research methods used or suggested, advice regarding the research process, the impact of research on participants, and discussions about the links between research, theory and practice.

Additional data extracted

In addition to the above-mentioned data, the reference lists of sources used by Dicks et al. (2017a) were perused, and citations occurring specifically among those 120 sources were noted. Data obtained in this way were used to establish the ‘activity level’ of each source in terms of both citing others and being cited. This activity level was expressed as a ‘citation-linked impact score’ while an additional measure, the ‘combined impact score’, considered both citations and the content of each source specifically in relation to the understanding of family bereavement. The calculation of these scores is described in Supplementary File 1, and insight gained by their use is discussed in Section 3.

Data analysis

Qualitative longitudinal research (QLR) aims to explore a phenomenon over time and describe not only what happens, but how it happens (Carduff, 2013). The unfolding process is studied within a socio-cultural context (Holland et al., 2006) to demonstrate the interplay between time, society, culture and other relevant variables. In this article, QLR methods are used to analyse data extracted from sources previously used to gain an understanding of family bereavement in the context of the potential for organ donation.

Results

Results are described below in four sections corresponding with the four research questions mentioned earlier. Although these sections are treated separately below to assist with the organisation of data, they are connected, and findings are integrated in section ‘Discussion’. Various features of the in-hospital process are described with the understanding that they contribute in some way to family bereavement.

Section 1: role players and the developing narrative

This section introduces the dynamic context in which the narrative about the bereavement of families who were asked to consider organ donation developed. The actions of researchers and their interaction with others during the four time periods are explored.

1968–1985

The narrative that developed during T1 describes the new phenomenon of organ donation after brain death (DBD) and helps to ensure the sustainability thereof. Newspaper stories gave members of the public a way to ‘observe’ others and see them as coping well, while peer-reviewed sources provided the medical community with a way of observing the benefits of this new phenomenon.

According to Christopherson and Lunde (1971), journalists were initially allowed to publish information about the identity of organ donors and recipients. Transplant teams later met with newspaper editors and negotiated alternatives when they became aware that families of donors and recipients found the publicity inappropriate.

Early sources demonstrate close interaction between research and the practices that were studied. Research conducted at centres contributed to better understanding of the needs of families and practice improvements rapidly followed. Some findings were supported by later research and were drawn into the narrative of family bereavement, while others were not. This interactive, social process of creating, exchanging, clarifying and challenging ideas is a necessary part of meaning-making and narrative development (Neimeyer et al., 2014).

The first researchers who aimed to make sense of this phenomenon needed a reference point – something to compare their observations with. Theoretically, this can be related to one’s sense of global meaning which serves as a guide when interpreting new experiences (Park, 2010). During T1, researchers reflected on the field in terms of theories of grief. For example, Christopherson and Lunde (1971) noted that the period of acute grief lasted 4–6 weeks as had been predicted by grief theory. In the references section of her article, Pittman (1985) lists 12 sources, seven of which relate to the understanding of bereavement at that time, confirming the importance given to grief theory.

During the period leading up to 1985, sources attempted to provide a holistic understanding of family experiences (although samples included many more consenting than non-consenting families). The contributions of T1 authors laid the foundation for the understanding and response to the new phenomenon of organ DBD.

1986–2000

During T2 sources demonstrate a sharper focus, looking at specific features within the in-hospital process. Many studies from T2 did not use grief theory as a point of reference as those from T1 had. Instead, efforts were made to develop a specific theory to fit the organ donation context.

For example, Pelletier (1992, 1993a) explored factors contributing to family stress and methods used by families to cope, while Sque and Payne (1996) developed the Theory of Dissonant Loss to explain aspects of the family experience.

While researchers before 1986 showed confidence that the characteristics of the organ donation context could be understood and did not significantly impact on family grief (e.g. Christopherson and Lunde, 1971), researchers during T2 admitted that there was still much to learn. For example, Painter et al. (1995) pointed out that improvements in care and planning based on research findings were ongoing, and Caplan (1995) argued that little was known about the impact of organ donation requests, especially on families who declined donation. By 1986, organ donation was relatively well established in many countries and had become an accepted practice. Perhaps this allowed uncertainties to be described without them threatening the future of organ donation and transplantation.

When discussing future directions, Perkins (1987) argued that psychology was the discipline best positioned to study and understand family and staff experiences while identifying needs for support and training. Perkins (1987) recognised that to conduct meaningful research in this context, psychologists would need to gain the trust of stakeholders and establish cooperative relationships with members of donation teams.

Researchers agreed that understanding and improvement of the family experience had not progressed at the same rate as medical understanding in the donation and transplantation context (Holtkamp, 1997; Pelletier, 1993b; Robertson-Malt, 1998; Sque and Payne, 1996). Siminoff and Chillag (1999) argued that those developing metaphors and slogans for community awareness campaigns should be aware of the implications of their symbols and their impact on the experience of families. These comments highlight connections between medical, psychological and social factors.

It seems that towards the end of T2, researchers were not content to just describe uncertainties and gaps. Strong comments made by Holtkamp (1997), Robertson-Malt (1998) and Siminoff and Chillag (1999) about the need to give families a voice and to see the field from the family’s point of view suggest a blurring of the line between researcher and advocate.

2001–2010

Researchers argued that more attention had been given to technical aspects, and the experiences of transplant recipients than to understanding families who were asked to consider donation (Cleiren and Van Zoelen, 2002; Holtkamp, 2002). Noting that positive stories were encouraged, and stories of less satisfied families went unheard, they argued that the study of family bereavement should be more thorough in order to improve understanding and service delivery (Holtkamp, 2002). Tavakoli et al. (2008) argued that the family’s experience of the in-hospital process had not been fully explored and noted that although findings of studies indicated that consenting to donation may alleviate grief, the actual mechanisms that may contribute to this had not been specified.

Maloney and Altmaier (2003) agreed that the psychological aspects of the context are crucial and argued that psychologists interested in the bereavement of families should develop this area of the literature. Siminoff et al. (2001) noted that public education neglected the details of the donation process, contributing to families being unprepared.

While researchers during the previous period had explored specific areas, researchers during T3 called for a consolidation of understanding. Bellali and Papadatou (2006) felt that studies had neglected to explore the process as a whole, hindering the development of a comprehensive theoretical model of family bereavement in this context. Sque et al. (2006) agreed that a conceptual framework would facilitate understanding of family experiences and guide in-hospital interaction, and López et al. (2008) argued that integrated explanations of the process would contribute to the development of a theory that considers the family’s perspective.

Stouder et al. (2009) identified the value of support from extended family members but acknowledged that they had not investigated how interaction becomes supportive. Stouder et al. (2009) noted that few studies in the organ donation context address grief and suggested that incorporating knowledge of the grief process could promote understanding of family reactions and needs. This observation could be seen as seeking to address the movement away from theories of grief that occurred during T2.

2011–2017

Over the final period, both diversification and consolidation are observed. Instead of focussing on understanding the experience of the potential for organ donation as a singular phenomenon, some researchers differentiated between DBD, donation after circulatory death (DCD) and the experiences of families who consented to DCD that did not proceed (Hoover et al., 2014; Siminoff et al., 2017). The differences experienced when the potential donor was a child rather than an adult (Siminoff et al., 2015) or when the wishes of the potential donor were unknown rather than known (De Groot et al., 2015) received attention.

The general understanding of bereavement has become more complex over the past 50 years, and this is reflected in the present attention given within the field of organ donation to moral dilemmas, meaning-making, continuing bonds and narrative when referring to family experiences.

Outcome measures described in a number of T4 sources reflect the earlier T1 focus on family satisfaction and promoting a healthy bereavement (Ashkenazi, 2010; De Groot et al., 2012; Jensen, 2011a, 2011b; Marck et al., 2016; Northam, 2015; Ralph et al., 2014; Walker and Sque, 2016) rather than the focus on obtaining consent and increasing donation rates that was seen in a number of studies during T2 and T3.

During T4, four systematic reviews (De Groot et al., 2012; Falomir-Pichastor et al., 2013; Ralph et al., 2014; Walker et al., 2013) focussing on various aspects of family experiences were conducted. These use information from previous time periods and contribute towards a consolidation of knowledge as was called for during T3. In addition to the systematic reviews, a number of PhD studies have explored the area in recent years. These include Ashkenazi (2010), De Groot (2016), Jensen (2011a) and Northam (2015). Journal articles have been published associated with this research. With the consolidation that has already taken place, an opportunity exists for the development of an evidence-based theoretical framework and a more structured approach to future research guided by the identified gaps and developing theory.

Section 2: study focus and design

Overarching research priorities have changed from one period to the next as described in Section 1, while specific suggestions for future research show overlap across periods. For this reason, Section 2 findings are not separated according to the time periods.

Suggested research topics

Researchers have highlighted the need for a comprehensive theoretical framework (Bellali et al., 2007; Falomir-Pichastor et al., 2013; Long et al., 2008; Pelletier, 1993a; Sque et al., 2006). Acknowledging the complexity of the in-hospital process, they argue that the theoretical framework should reflect this and describe how the process unfolds and changes over time (Bellali and Papadatou, 2006), giving attention to interaction and mutual influence among relevant factors (Falomir-Pichastor et al., 2013).

It has been suggested that the significance of specific factors such as pre-existing family relationships (Ashkenazi and Guttman, 2016), consenting or declining donation (Painter et al., 1995; Walker and Sque, 2016), DCD or DBD (Bauer and Han, 2014; Hoover et al., 2014; Mills and Koulouglioti, 2016; Sque et al., 2013; Taylor et al., 2017), culture and religion (Northam, 2015; Ralph et al., 2014; Shih et al., 2001a), family and staff roles (Anker, 2013; Ashkenazi, 2010; Bellali et al., 2007; Mills and Koulouglioti, 2016; Northam, 2015; Sanner, 1994) and demographic factors (Hoover et al., 2014) must be studied. Rodrigue et al. (2010) argued that family members who ask about the possibility of organ donation before staff have raised the matter have special needs that must be understood to facilitate a caring response.

Other suggested topics include the exploration of the family’s perceptions of experiences (Jensen, 2011b; Maloney and Altmaier, 2003; Ralph et al., 2014; Simmons et al., 1972; Walker et al., 2013), such as their final separation from their loved one (Ashkenazi and Guttman, 2016), and the in-hospital process as a whole (Bartucci, 1987).

Sque et al. (2013) argue that the role of young people and children and the impact of the process on them is not clearly understood. This gap needs to be addressed within the requirements of ethics committees. Family support and communication should be optimised at each stage of the in-hospital process, and opportunities to provide care after a decision has been made should be explored (Sque et al., 2013).

Exploration of these areas could lead to the identification of risk factors that increase the possibility of complications in bereavement and protective factors which assist the grieving family (Ralph et al., 2014; Shih et al., 2001a; Tavakoli et al., 2008). The support needs of family and staff (Bartucci, 1987; Ralph et al., 2014) and understanding of the impact of the in-hospital process on bereavement (Caplan, 1995; Cleiren and Van Zoelen, 2002; Kinjo and Morioka, 2011; Pittman, 1985; Randhawa, 1998; Simmons et al., 1972; Walker and Sque, 2016) must be explored further.

Researchers agreed that a better understanding of the psychological aspects of the context is required (Holtkamp, 1997; López Martínez et al., 2008; Sque and Payne, 1996; Steed and Wager, 1998) with particular attention to be given to the development of trust (Anker, 2013) and hope (Jensen, 2016; Northam, 2015). Jensen (2016) highlights the need to investigate the shared hopes of family and staff as they interact during the in-hospital process.

Understanding of the interaction between aspects of the experience including sudden death, trauma, a donation request and bereavement (Haney, 1973; Holtkamp, 1997, 2002; Pittman, 1985; Simpkin et al., 2009) can contribute to improved staff training (Maloney and Altmaier, 2003), a meaningful family experience (Pelletier, 1993b) and family-centred outcomes such as empowerment (De Groot et al., 2012) and satisfaction (Marck et al., 2016).

Researchers argued that families experience vulnerability and more research is needed to examine how follow-up and counselling can help (Mills and Koulouglioti, 2016; Ralph et al., 2014). The study of variables related to meaning of life after loss (Ashkenazi and Guttman, 2016) and the need to develop and evaluate aftercare support programmes were also highlighted (Ralph et al., 2014; Shih et al., 2001a).

Suggested methodological considerations

Research studies focussing on bereavement encounter unique recruitment challenges (Walker and Sque, 2016). It was stressed that careful attention to the wording of the initial invitation to participate is vital. The document should indicate the purpose of the study and describe how participation could assist others (Kiss et al., 2007; Pearson et al., 1995; Rodrigue et al., 2008a, 2008b). Comments were also made regarding the timing of recruitment, and many participating families over the years suggested that early recruitment would allow better recall (Berntzen and Bjork, 2014; Shih et al., 2001a).

It was agreed that an interview guide should be logically structured to gather information regarding the family’s unfolding experience (Long et al., 2006; Sque et al., 2008), but at the same time be flexible enough to adapt to emerging concepts (Bellali and Papadatou, 2006) rather than adhering strictly to pre-determined criteria (Walker et al., 2013).

Researchers suggested that it is valuable to incorporate input from advisory panels, families who have experienced the in-hospital process and past research when designing interview guides (Hoover et al., 2014; Rodrigue et al., 2008a, 2008b).

The value of prospective longitudinal studies (Anker, 2013; Ashkenazi, 2010; Bellali and Papadatou, 2006; Northam, 2015; Sque et al., 2008) and the need to capture descriptions of family dynamics were highlighted (Bellali and Papadatou, 2006; Simmons et al., 1972). Sque et al. (2013) suggest that a prospective, ethnographic, observation study should be conducted to improve understanding of interaction at the hospital.

Bellali and Papadatou (2006) suggested that longitudinal studies could explore the evolution of grief for individual family members and the family as a whole. Sque et al. (2008) felt that prospective studies with families identified at the time of their in-hospital journey could produce more adequate samples than retrospective studies.

Given the sensitive nature of research in this field, researchers suggested that making provision for the possible secondary analysis of data was valuable (Frid et al., 2007; Long et al., 2008; Sque and Galasinski, 2013). Anker (2013) felt that multi-centre studies would produce findings that were generalisable, and Bellali and Papadatou (2006) felt that providing participants with details of data analysis would provide an opportunity for them to participate in enhancing the quality of study outcomes.

Other suggestions made regarding the process of research

The importance of good working relationships between researchers and other role players such as the donation team (Perkins, 1987), hospital staff (Duckworth et al., 1998; Kiss et al., 2007) and ethics committee(s) (Kiss et al., 2007) was emphasised.

During research interviews, the value of a conversational style rather than an overly structured approach was highlighted (Frid et al., 2001; Hoover et al., 2014; Pelletier, 1992). It was suggested that a supportive, caring presence would contribute to understanding (De Groot et al., 2015; Holtkamp, 1997) and that the relational aspect of sharing information is a vital component of data collection (Cleiren and Van Zoelen, 2002). In many studies, families were given a choice with regard to the venue for interviews, and they often chose the natural environment of their own home (Berntzen and Bjork, 2014).

Taylor et al. (2017) report that interviews were opened with a broad question: ‘Could you share the story of your personal experience with organ donation?’ Their project design allowed the interviewer’s technique and questioning to improve in response to feedback and emerging themes. Similarly, in Frid et al.’s (2001) study, families were encouraged to freely narrate their experiences.

Morton and Leonard (1979) found that families appreciated the opportunity to participate in the research interview and other researchers reported that many family members found participation in research to be supportive, comforting and beneficial (Berntzen and Bjork, 2014; De Groot et al., 2015; Jensen, 2007). Frid et al. (2001) feel that it is perhaps the self-reflecting process that contributes to the healing effect of narrating one’s own experiences. Similarly, Marck et al. (2016) found that many participants used the interview to ask questions and clarify misunderstandings.

Families hoped that by participating in studies they would be heard and that improvements would be made to the system (Sque et al., 2003), benefiting future families (De Groot et al., 2015; Jensen, 2016). This hope contributes to a sense of community (Jensen, 2016) and research projects become part of the life stories of participating families (Jensen, 2007).

Suggestions regarding the researcher role

Sque and Payne (1996) argued that researchers (as narrators of participants’ stories) should view themselves as being in a relationship with participants and readers where personal values and interests influence meaning and interpretation. The way that the research narrative is formulated depends on the narrator’s ability to connect data to other discourse in order to develop theoretical understanding (Frid et al., 2001).

Researchers should reflect on the impact that they have on participants and provide information about this reflective process to readers (Sque and Payne, 1996). Jensen (2016) argues that researchers should pay attention to the encouragement, demands, responses and responsibilities related to their research to contextualise findings.

During T4, researchers at times included themselves in their descriptions. For example, De Groot (2016) explains, ‘I see incomprehension and despair in the eyes of family members as the doctor comes along to tell them that their loved one has probably died. … The response from families is what prompted me to do this research’ (p. 10). Jensen (2011a) also included herself in her descriptions and reflected on the impact that her research had on her perceptions, contributing to new insights.

Sque et al. (2013) felt that the participation of donation and hospital staff in research should be encouraged and argued that training should be provided to enhance research competencies of members of these groups.

Section 3: sharing research findings and recommendations

Simmons et al. (1972) discussed both deceased and living donation, and noted that

by focusing on individuals … most of the previous literature … [mainly exploring living donation within a family] … has ignored the stress that the … [process] … has on the family as a whole. Conflicts and pressures within the family and channels of family communication have not been investigated. (p. 322)

Similarly, Pittman (1985) argued that post-mortem organ donation requests complicate the ‘already difficult and ambivalent … [experience of sudden death]’ (p. 569) and urged researchers to study the family’s experience where differences in opinion could lead to ongoing tension. However, despite these recommendations, many studies have continued to obtain information from individuals and then generalise statements as if related to families without thoroughly exploring the experience of the family system.

Considering this observation in the light of this article led to the following question:

If treating a family simply as a group of individuals overlooks the synergistic effect of relationships and connections, could it be said that treating sources selected for a systematic review as individual elements overlooks the ways in which the sources interact, and collectively contribute to the process of narrative development?

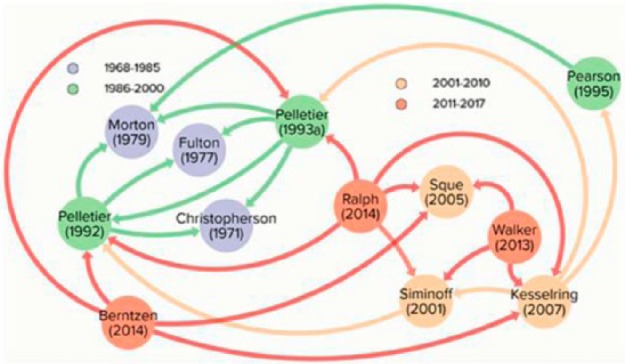

The present section addresses this question by exploring the dynamic process of communication about research concerning family bereavement in the context of the potential for organ donation. To illustrate this communication, citation maps were constructed using the online KUMU mapping software (https://kumu.io).

While a table can perform the task of identifying relevant sources and describing their attributes, it does not describe the interaction between sources and treats each as if it exists on its own. The present section asserts that acknowledging the network that developed when authors cited others contributes to understanding of how the narrative of family bereavement developed.

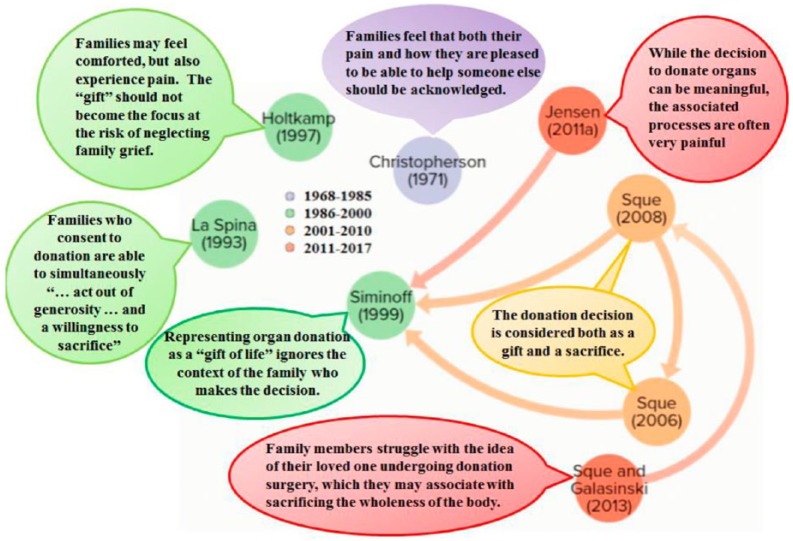

The following examples demonstrate the risks related to lack of interaction between the ideas of researchers: Christopherson and Lunde (1971) noted that families felt it was important that both their pain and how they were pleased to be able to help someone else was acknowledged. La Spina et al. (1993) later concluded that families who decide to consent to donation are able to simultaneously ‘… act out of generosity … and a willingness to sacrifice’. (p. 1700)

Holtkamp (1997) noted that families might feel comforted, but also experience pain and argued that the ‘gift’ should not become the focus at the risk of neglecting family grief. Siminoff and Chillag (1999) later argued that representing organ donation as a ‘gift of life’ ignores the context of the family who makes the decision, and Sque et al. (2006, 2008) explored the simultaneous consideration of donation as a gift and a sacrifice. Jensen (2011a) argued that while the decision to donate organs can be meaningful, the associated processes are often very painful, and Sque and Galasinski (2013) described family members’ struggle with the idea of their loved one undergoing donation surgery, which they may associate with sacrificing the wholeness of the body.

Although the researchers mentioned above may have been referring to similar comments made by families, there are few citations between the sources. Sque et al. (2006, 2008) and Jensen (2011a) cite Siminoff and Chillag (1999) while Sque and Galasinski (2013) cite Sque et al. (2008), and Sque et al. (2008) in turn cite Sque et al. (2006). This example demonstrates how the understanding of the family’s experience of making a decision about donation has developed in a slow and disconnected way over the last 50 years in spite of the way that La Spina et al. (1993) had captured the idea that families confront ambiguities associated with the gift and sacrifice metaphors. This is shown in Figure 1, where sources are identified by the first author’s name only when this does not contribute to ambiguity in order to reduce in-diagram text.

Figure 1.

Lack of connection between authors exploring the gift and sacrifice metaphors.

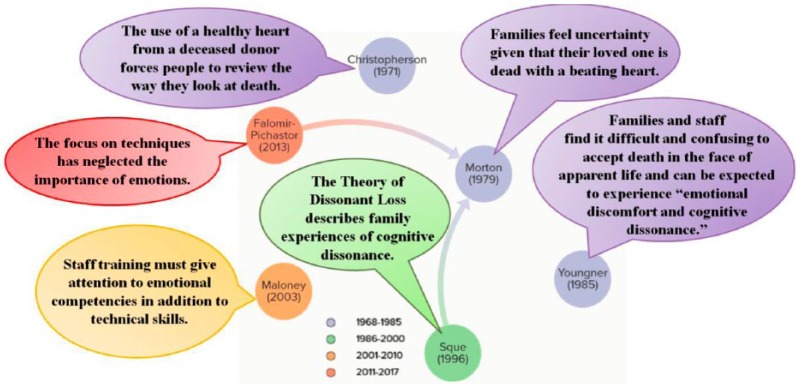

Another example illustrates this too. Christopherson and Lunde (1971) had noted that BD and the use of a healthy heart from a deceased donor forced people to review the way they looked at death while Morton and Leonard (1979) found that some families felt uncertainty given that their loved one was dead with a beating heart. Following that, Youngner et al. (1985) argued that families and staff find it difficult and confusing to accept death in the face of apparent life and can be expected to experience ‘emotional discomfort and cognitive dissonance’ (p. 323).

Eleven years later, Sque and Payne (1996) described the Theory of Dissonant Loss to account for family experiences of cognitive dissonance, while Maloney and Altmaier (2003) called for attention to be given to affective competencies in addition to technical skills in staff training programmes suggesting that while technical skills and understanding had reduced cognitive dissonance of staff, the emotional nature of the context had received insufficient attention. Even later, Falomir-Pichastor et al. (2013) added that the focus on techniques and other contributing factors had neglected the importance of emotional influences.

Youngner et al. (1985) captured the importance of cognitive and emotional vulnerabilities related to family and staff experiences while sources almost 30 years later still highlight the need to gather more information. These examples show that understanding of concepts is hampered when information-sharing in not coordinated (see Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Slow development in the understanding of emotional and cognitive stressors.

Citation-linked impact score

Having noticed the disconnection described above, and considering the implication that the voices of researchers and participants are at times not heard, we sought a way to explore how sources relate to each other. This is seen as relevant to the current review because if research is conducted but not drawn into the narrative about the donation context, its potential to contribute to practice improvement is diminished.

Where other reviews evaluate the quality of sources individually in terms of factors such as methods used and analysis conducted, we propose that it is also useful to know whether findings are contributing to overall understanding by being drawn into the dynamic discussion about the field.

Reference lists of sources used by Dicks et al. (2017a) were used to map the way that those 120 sources cited each other. Using this information, a measure of the impact of each source on the developing narrative was calculated. This measure assumes that a source should demonstrate familiarity with previous literature by making citations, and then when that source is cited by future sources, it contributes to the narrative. Comments could be positive or negative and represent a way in which researchers give each other (and research participants) a voice.

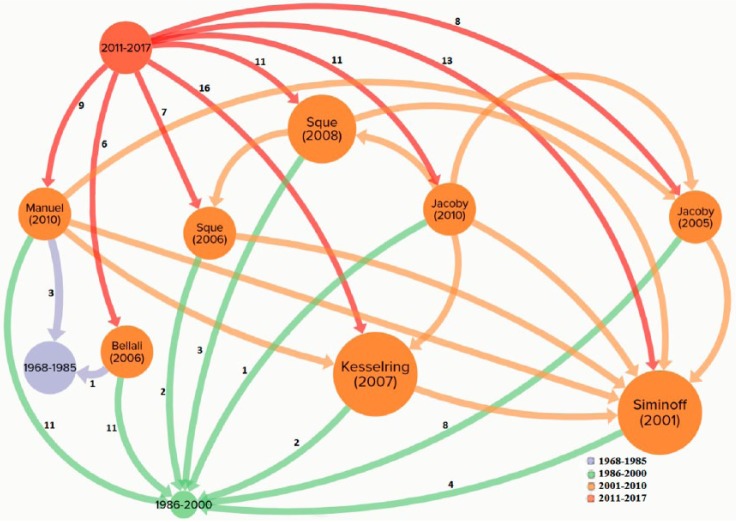

The usefulness of the citation-linked impact score will be demonstrated with reference to some of the most ‘active’ (in terms of citation scores) T3 sources. In Figure 3, scaled scores calculated as described in Supplementary File 1 were used to determine the size of the circle representing the sources shown.

Figure 3.

Connections between most active T3 sources and sources from other periods.

The citation mapping of some active T3 sources shows that the sources have different levels of activity. All those shown cite articles from T2 (shown by green lines), and all are cited by T4 sources (shown by red lines). The small numbers on the connecting lines indicate how many sources from other periods cite or are cited by each T3 source shown. For example, Kesselring et al. (2007) were cited by 16 T4 sources that were used by Dicks et al. (2017a) but only cite two sources from T2. This suggests that rather than focussing on highlighting already- published sources, Kesselring et al. (2007) added new information which was drawn into the narrative by subsequent sources.

Bellali and Papadatou (2006) and Manuel et al. (2010), on the other hand, both cite T1 sources and 11 T2 sources each, while being cited by 6 and 9 T4 sources, respectively. This could suggest that these sources (Bellali and Papadatou, 2006; Manuel et al., 2010) play the important role of reflecting on, consolidating and drawing information from previous periods into the narrative in addition to adding new information. Both these articles made valuable contributions to the previously published review of family bereavement (Dicks et al., 2017a) and it is surprising that they were not more actively cited.

Figure 3 demonstrates the range of connectivity among ‘popular’ sources, and it must be remembered that other sources not shown provided valuable information without being drawn into the narrative (see Frid et al., 2007 in Table 1 of Supplementary File 1). The risk of information getting ‘lost’ in this way is not visible in linear tables of sources and their attributes but becomes clear when exploring citation histories.

Combined (relevance and citations) impact score

Following the completion of the review of family bereavement (Dicks et al., 2017a), the extent to which content of each source was relevant to the understanding of family bereavement could be determined. Supplementary File 1 describes the calculation of combined impact scores that considered both activity level as described above and relevance of content. The three sources with the highest combined impact scores from each of the time periods are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Interaction between high scoring sources (based on combined impact score).

It is relevant that among these ‘Top 12’ sources, the T1 sources have only been cited by T2 sources, suggesting that to some extent these T2 sources act as intermediaries, passing insights from T1 to later periods. T4 sources shown have not cited each other, highlighting the need to consolidate findings. Pelletier (1992, 1993a) and Kesselring et al. (2007) play an active role, citing and being cited by sources from multiple time periods, while also adding significantly to the content of knowledge in this field.

Figure 4 can be seen to show some of the sources that have contributed most significantly to the understanding of family bereavement both through breadth of content and by active contribution to the narrative. It is suggested that practitioners and researchers interested in obtaining information about the main features of family bereavement in this context from original sources could begin by reading the 10 original articles referred to in Figure 4 (Ralph et al. (2014) and Walker et al. (2013) are systematic reviews).

Section 4: research translation

Impact of research

While research has contributed to the understanding of family bereavement, this understanding needs to be translated into supportive activities and staff training before it can benefit families (Manuel et al., 2010). Earlier studies describe an immediate impact on practice, but the impact of recent studies is difficult to determine.

Christopherson and Lunde (1971) noted that the transplant centre conducted research and then changed practices accordingly. Similarly, Fulton et al. (1977) note that research interviews indicated that families wanted to know the time of death and in response, practices were immediately adapted. Morton and Leonard (1979) report that as a result of feedback received from families, an interview was included as part of follow-up care, and the term ‘harvesting’ was replaced with ‘recovery/retrieval’.

Kesselring et al. (2007) used a phone call about 6 months after the death as part of their research method. When families provided positive feedback about the opportunity to speak to someone at that time, a call was incorporated into the support provided to families in general. Good relationships between the research team and intensive care unit (ICU) staff made rapid change possible, and findings from the study that were incorporated into a training workshop for nurses were well received (Kesselring et al., 2007; Kiss et al., 2007). This demonstrates the value of good relationships with stakeholders.

Design of studies should include attention to increasing the awareness of the study, and thereby the study’s impact, while identifying opportunities to influence practice through collaboration and working relationships with practitioners (Douglass and Daly, 1995; Neidlinger et al., 2013; Painter et al., 1995). The need for researchers to consider the impact that their projects may make and find ways of measuring that impact was highlighted. Duckworth et al. (1998) argue that parameters involved in the measurement of impact must be carefully chosen to include aspects such as compassion and care which are not easy to quantify.

Pittman (1985) notes that research should contribute to improvements in services provided to families in-hospital and after they leave while Youngner et al. (1985) argue that understanding of difficulties encountered by families and staff could contribute to practice enhancement. Sque and Payne (1996) argue that there is a need for researchers to develop a theory of loss and separation that could contribute to improved family care, and Perkins (1987) noted that the in-hospital process requires sensitivity and tact, highlighting the need for research exploring staff training.

The responsibility of the researcher to give a voice to the experiences of participants was also highlighted. Robertson-Malt (1998) noted that at times this voice may challenge the status quo and raise questions but should not be silenced or seen as a threat. Jensen (2016) considered her responsibility in relation to participants’ desire to make a difference. In response, she presented research findings to professionals in 50 lectures nationwide in keeping with the families’ desire that their experiences should be shared.

De Groot et al. (2015) reported that families provided suggestions for how the in-hospital process could be improved, including moral counselling, more time, compassion, support or having a mediator to assist the family. Participants in Hoover et al.’s (2014) study thought about families who would in future find themselves considering DCD and suggested, ‘Listen to your heart, trust your intuition; find out about options, there are choices; talk with your family; Ask more questions; Ask to speak to another family who has had this experience’. Hoover et al. (2014) explored ways of making these voices heard.

Suggestions made regarding practice

Researchers made specific suggestions for in-hospital practices and family care. Pelletier (1993b) stressed that in order to provide the best possible service to families, staff must work collaboratively and support each other. Jensen (2011a) included families in her ideas about collaboration and felt that family members should play a role in the development of new practices, improvements and policies because they represent a valuable source of information based on their experiences.

Shih et al. (2001b) argued that training should include the post-decision phase and coping strategies of families who previously made decisions about donation should be shared with families during the in-hospital process. Maloney and Altmaier (2003) felt that affective competencies should form part of training programmes and argued that donation-related self-efficacy should be measured as part of programme evaluation. Jensen (2011a) argued that in addition to being ‘taught’ at workshops, staff members value the opportunity to discuss ethical challenges and learn from each other.

Because families need to be assisted to understand the structure and procedures of the in-hospital process (Cleiren and Van Zoelen, 2002), providing them with information about the process and suggesting coping strategies may be empowering (Mills and Koulouglioti, 2016). Rodrigue et al. (2008a, 2008b) felt that all staff involved should play a role in the assessment of family dynamics.

Together these researchers seem to highlight the need for family and staff to understand each other’s roles. Indeed, De Groot et al. (2012) argue that the relationships between family members and staff are vital components of the process and could contribute to family empowerment. Creative interventions, including peer support and the use of intermediaries, can improve family care (Jacoby et al., 2005; Jacoby and Jaccard, 2010; Lloyd-Williams et al., 2009).

Discussion

The current discussion consolidates observations from the sections previously described. Park (2010) argues that meaning-making begins soon after an event that has disrupted one’s sense of global meaning. If the first heart transplant in 1967 is seen as a disrupting event in this sense, actions and explanations of families, researchers, journalists and others can be seen as attempts at meaning-making, contributing to the development of a narrative of family bereavement in the context of a request for organ donation.

Concepts have developed and have been challenged and tested for relevance over the 50-year period. During T1, the meaning-making process adopted an outward focus, seeking to understand family experiences by comparing them to grief theory, and during T2, there was an inward focus, seeking to understand the field as being unique, requiring new conceptual frameworks. These shifts can be seen to be reflected in theories that suggest that people move to and fro, alternating between processes while coming to terms with life-changing events (Pelletier, 1993a; Stroebe and Schut, 1999). T3 researchers called for a consolidation of knowledge, and a reconnection with grief theory and T4 researchers seem to have responded with a number of systematic reviews which consider existing sources from different points of view.

As described in Section 2, this consolidation has assisted researchers to clarify current research priorities. The systematic reviews identify the need for a comprehensive theoretical framework (linked to grief theory) that captures family experiences and guides staff to identify risk and protective factors. This will enable staff to provide support that assists families to cope with decision-making, grief and acute stress during the in-hospital process and after they return home. Exploration of the influence of specific circumstances (e.g. DBD and DCD), increased understanding of psychological factors and identification of aftercare priorities have been highlighted as areas requiring attention.

Various research methods have been used over the years, and researchers currently highlight the potential value of prospective qualitative longitudinal studies that could contribute to the understanding of bereavement and the coping of individuals and the family system over time. Researchers also emphasise the value of a systemic understanding of research itself, giving attention to the links and relationships that form between researchers, participants, ethics committees, hospital staff and other stakeholders.

Authors have more recently looked at complexities in the roles of researcher and participant. Rather than being observer and observed, researchers acknowledge the impact that parties have on each other. The need for self-reflection and consideration of the researcher and the project within a broader context has been emphasised, and researchers have been advised to consider the responsibilities that they have towards participants who want to be heard and hope to contribute to practice improvement.

Section 3 proposed that by conducting research, sharing findings and citing each other, researchers have contributed to the development of an emerging narrative about family grief. The need for researchers to plan for the dissemination of their findings was highlighted by demonstrating how the implications of important concepts (e.g. dissonance, gift, sacrifice) were only described years after the concepts had initially been identified.

The use of local impact scores assisted with the identification of sources that made a significant impact on the narrative explored by Dicks et al. (2017a) and also demonstrated that some sources containing valuable content did not get drawn into the narrative.

These findings suggest that researchers should look within the system that their studies become part of to identify leverage points and ensure that knowledge develops in a connected and coordinated way. Failing to do so contributes to significant delays in the development of understanding and implementation of improved practices.

Citation maps suggest that authors from each time period reflect mainly on sources from the preceding period, confirming findings and adding new ideas. Ensuring that information from earlier time periods is not overlooked could assist researchers to avoid repetition and facilitate the advancement of theory.

Early researchers did not have access to present means of sharing findings such as email, the Internet, open access journals and social media while more recent sources do not describe whether these tools were used. This highlights a need to explore the potential contribution that these resources can make to enhancing theory and knowledge by connecting researchers and projects internationally. The extent to which researchers would be enthusiastic about using these methods must also to be explored. Trends linked to this may be the increasing use of journal publications during PhD research and websites which allow researchers to follow each other’s projects. These methods help to raise the awareness of projects while they are unfolding.

The fourth section demonstrated the need to consider the outcome of research in terms of the impact that it makes on the development of understanding and practice improvement. Considerations need to be built into study design from the beginning as it would be difficult to later develop the productive working relationships that researchers are advised to form with participants, advisory panels, ethics committees, organisations, practitioners and other stakeholders. Projects need to fit the context and respect stakeholders, building relationships and effectively communicating findings in a way that demonstrates potential value to the existing system.

This review has identified areas requiring further research and makes suggestions regarding methodologies while also highlighting ways to facilitate practice improvements. These findings are summarised in Supplementary File 2.

Meaning-making and research priorities

During the course of this article, we have hypothesised that meaning-making (e.g. Park, 2010, 2017) offers a way of understanding the co-evolution of research priorities and understanding in the context of the potential for organ donation. In this section, the hypothesised links are made clear, and examples relevant to the preceding sections are described in terms of meaning-making.

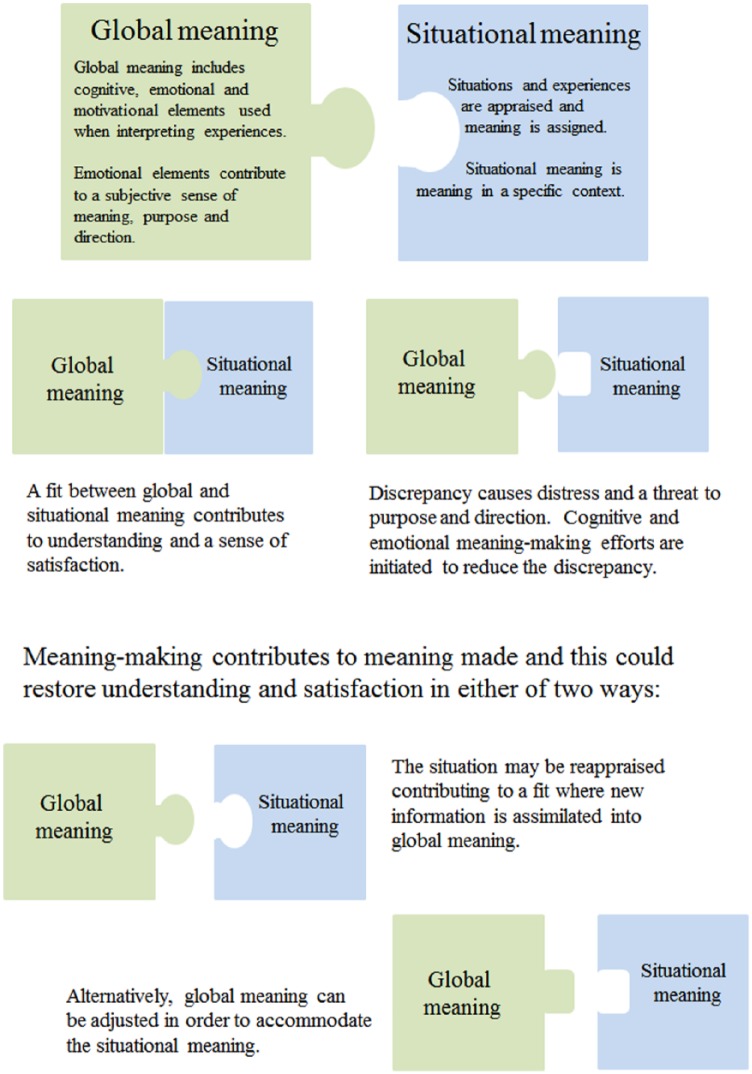

First, a summary of the meaning-making model is provided. Park (2010, 2017) distinguishes between global meaning, which develops over time and has a degree of stability, and situational meaning which develops in response to specific experiences. If the meaning attributed to a new situation matches what would be expected given one’s global meaning, satisfaction and acceptance are expected whereas when there is a discrepancy, distress is expected. This distress triggers meaning-making efforts in an attempt to restore congruence by adjusting situational and/or global meaning. When successful, these efforts reduce stress and restore a sense of purpose and direction. At times, a number of iterations may be required to achieve this. Figure 5 summarises Park’s (2010, 2017) model and provides more detail.

Figure 5.

The main tenets of the model of meaning-making (Park, 2010).

While originally described as a model to understand an individual’s meaning-making efforts in response to distress, we believe that the model is useful in the present context too. If global meaning was taken to be similar to theoretical understanding, discrepancies were seen as similar to areas requiring clarity, and meaning-making efforts included setting of research priorities and other research-related activities, observations such as the following can be made.

Christopherson and Lunde (1971) showed concern about the impact of organ donation on family bereavement, given that the diagnosis of BD challenged the idea that a beating heart indicated life, and probably also considering the impact of families allowing donation surgery after death. As a theoretical starting point, Christopherson and Lunde (1971) compared the grieving of families who had donated organs to the theories of grief available at that time. It was found that donating organs did not impact significantly on grief and may even have a positive effect. This would have restored meaning and strengthened constructs such as beneficence, allowing the phenomenon of organ DBD to be assimilated into what was already known about bereavement.

Park (2010) distinguishes between making sense (comprehensibility) and determining the implications (significance) of an experience. In the above-mentioned example, Christopherson and Lunde (1971) showed that when families comprehend BD as death, they are able to consider organ donation without it impacting negatively on their bereavement.

Fulton et al. (1977) reported that families notified researchers that not knowing the exact time of death created stress (possibly raising the question, ‘Were the organs removed before or after death?’). Researchers communicated with transplant teams, and practice was improved with staff making it clear to families that death was confirmed at the time of the second set of BD tests and that this would be recorded as the time of death. Here, parties worked together to identify and respond to discrepancies, restoring meaningfulness.

The above-mentioned example highlights two elements not described in detail by Park (2010, 2017). First, while Park (2010, 2017) speaks of agency, purpose and direction being associated with a functioning meaning system, the actual role of action or behaviour as a meaning-making tool is not described. Second, one of the actions described in the example above is social interaction. As described by Neimeyer et al. (2014), from a social constructionist point of view, interacting and exchanging ideas is an important part of meaning-making. Christopherson and Lunde (1971) refer to the role of newspapers as a way of connecting with the public and Morton and Leonard (1979) describe the use of a television documentary encouraging families to speak about organ donation. In these ways, meaning-making is simultaneously an individual and a social phenomenon.

Before the results of a particular study are published, there will have been communication between researchers regarding their project, and between researchers and ethics committees, and then interaction between researchers and participants, between researchers during analysis and between researchers, journal editors and peer-reviewers before publication. There would also have been self-reflection as individuals in this system considered the situations and information encountered. These all represent opportunities for meaning-making.

Pelletier (1992) noticed that although Christopherson and Lunde (1971), Fulton et al. (1977) and Morton and Leonard (1979), all T1 sources, had contributed significantly to understanding, their findings lacked a theoretical base. Pelletier’s (1992) appraisal that the lack of a theoretical base may hinder deeper understanding prompted her to explore family experiences of stress and coping and develop a theory that took these factors into consideration. Similarly, Sque and Payne (1996) hoped that their Theory of Dissonant Loss would provide a framework that would lead to improved understanding of the psycho-social effect of the in-hospital process.

These researchers observed that global meaning (represented by theoretical understanding) needed to be enhanced to be able to explain situational meaning (represented by findings of other studies). They were motivated to develop new ways of thinking about the context so that purpose and direction could emerge when global meaning was adjusted to allow new phenomena to be understood.

Although the model refers to iterative cycles of reappraisals and meaning-making, Park (2010) notes that the effect of time on meaning-making has not been explored in detail. Studying the sources used in this longitudinal study shows that over time relevant factors changed, sometimes because of conscious efforts in the field (during T1 physicians approached families to request donation whereas trained donation requesters performed this task during later periods) and sometimes because of developments outside of the field of organ donation (grief theory changed significantly over the 50-year period). While Christopherson and Lunde (1971) were satisfied that they understood the impact on family bereavement in the context of grief theory of that time, later researchers asked about the role of factors such as the biography of the deceased, the development of continuing bonds and the family narrative. These factors are features of present theories of grief and lead to new questions and discrepancies, and hence to new research priorities.

While models describing parts of the family’s experience emerged over the years, researchers during T3 identified the need to draw knowledge together and formulate a comprehensive theoretical framework. This suggests that global meaning and understanding can be observed as having different levels or layers. Pelletier (1992) acknowledged the value of T1 studies but commented that findings of individual studies did not provide a theoretical base. Researchers responded by creating models and theories and then later researchers such as Bellali and Papadatou (2006) identified the need for a consolidation of these models and the formulation of an overarching theory.

The systematic reviews conducted during T4 can be seen as a form of meaning-making that seeks to address that gap by drawing together existing knowledge. Related to the hypothesised layers of global meaning described above, the systematic reviews themselves were conducted independently and need to be viewed together in order to move closer to a consolidated theory. Dicks et al. (2017b) describe one way of synthesising the data contained in the systematic reviews. This asynchronous interaction between researchers may be seen as related to Neimeyer et al.’s (2014) argument that meaning-making and narrative formation are ongoing social processes.

This section has described how Park’s (2010, 2017) model of meaning-making can be applied to understand the way that research priorities, research projects, theoretical understanding and practice improvement have coevolved over the last 50 years. We also highlight the potential value of expanding Park’s (2010, 2017) model to include further consideration of goal-directed action as a form of meaning-making, the value of social interaction in meaning-making, the influence of time on variables related to meaning-making, and viewing global meaning as being layered.

The examples used in this section have been chosen to show how the thread of meaning-making connects the experiences of participants in early studies, the findings of the T1 researchers, the models of the T2 and T3 researchers and the findings of the systematic reviews conducted by T4 researchers. The thread shows a growing complexity in the understanding of the context as it moves towards the development of an overarching theoretical framework. While this takes place, individual studies continue to provide new insights that get drawn into the narrative.

Strengths and limitations

This study presents a novel way of exploring data sources in a systematic review contributing to a synthesis that includes not only their qualitative characteristics but also quantitative data. The creative approach has demonstrated that while ordering sources alphabetically contributes to ‘neatness’, ordering them chronologically and analysing them longitudinally contributes to new insights, and more clearly highlights the influence of time.

Tapping into the information contained in the reference sections of sources demonstrated that these need not be seen as static lists, but rather they can be utilised to illuminate the dynamic network formed by the selected sources. In this review, these data demonstrated problems with the dissemination of published data. Potentially, tools currently used for social network analysis could highlight further implications.

The study does have a number of limitations. The literature search was limited to English sources, and this study itself is limited by the inclusion and exclusion criteria used by Dicks et al. (2017a). The research priorities identified are related specifically to family experiences, especially of bereavement, and do not include factors such as increasing awareness, or assisting families to make decisions that they are confident about.

The novel methods used are presently not well developed, and although we feel that they highlight new sources and forms of information, the extent to which others may agree is presently unknown. While the citation-linked impact scores are purely quantitative and provide a reliable measure of each source’s activity among the sources analysed, the combined impact score does contain a subjective feature in that the number of times a source was cited within Dicks et al.’s (2017a) review (across the family’s experience from anticipatory mourning to ongoing adjustment to loss in the months that followed) was taken to be indicative of its content-related contribution to the narrative of family bereavement. This does help to identify sources that contributed to the understanding of a variety of elements during the family’s bereavement experience (breadth of understanding), but it does not demonstrate the value of studies such as Sque and Payne (1996) that contributed significantly to the depth of understanding in a more specific area.

The case of Sque and Payne (1996) highlights another weakness in the proposed combined impact score. When drafting Dicks et al. (2017a), the methods used in this article had not been developed, and the aim at that time was to represent a narrative of family bereavement in a trustworthy manner. Because Sque and Payne (1996) describe the development of a grounded theory, where the parts of their model are connected to form an interactive whole, the Theory of Dissonant Loss, that whole could be referred to without explaining the parts in detail, leading to the source being cited less often by Dicks et al. (2017a). In this way, the combined impact score of Sque and Payne (1996) under-represents the source’s contribution to the field.

In qualitative research, it is recognised that there is a reflexive relationship between the researcher, the data and the emerging text where meaning is not discovered but coevolves during the interaction between the data and the researcher (Charmaz, 2006) before being presented to the reader (Sque and Payne, 1996).

This article reports on our meaning-making efforts. We invite others to comment on and challenge the methods that we have used. This will contribute either to improvements, providing those conducting systematic reviews with new tools, or it may be determined that the information provided by our methods does not significantly advance understanding, and the methods will not gain popularity. Either way, discussion will contribute to meaning being made and that will determine the future use of these methods.

Conclusion

Researchers have commented on the value of using data initially collected for one purpose in order to answer questions that arise later. Secondary use of data is seen as particularly relevant in a sensitive field where obtaining ethics review board approval, recruiting participants and conducting research is a delicate and time-consuming process. This article describes a ‘secondary analysis’ of the sources used in a previous review. Where that review asked, ‘What do we know about family bereavement in the context of the potential for organ donation?’ this article asked, ‘What do we know about the process of studying family bereavement in this context?’

The novel methods used to conduct this review including longitudinal analysis and citation-analysis demonstrate changes in meaning-making and research priorities over time and highlight missed opportunities for sharing information that may have contributed to more rapid theory development and practice improvement.

The review of family bereavement demonstrated that although relevant research has been conducted related to psycho-social aspects of the field, theory and practice has not advanced as quickly as in the medical field of donation and transplantation. This article identifies potential explanations for this delay and demonstrates the need for connections between researchers and practitioners and the importance of planning early for dissemination and impact.

Findings suggest that researchers need to take the time to get to know the system that their research will interact with, identifying stakeholders, gaps, resources and leverage points in order to initiate shifts that lead to practice improvements and benefits for all role players.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

SGD, a PhD candidate, conducted the data extraction and compiled a draft of the review with guidance from his supervisory panel. Supervisors evaluated the draft and critically reviewed the methods, process, outcomes and presentation. In this way, all authors contributed to the final article. The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers whose comments were very valuable.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The first author acknowledges that as a PhD candidate, support was received through an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship.

Supplementary material: Supplementary material is available for this article online.

References

- Anker A. (2013) Critical conversations: Organ procurement coordinators’ interpersonal communication during donation requests. In: Laurie MA. (ed.) Organ Donation and Transplantation. New York: Nova Science Publishers, pp. 189–221. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi T. (2010) The ramifications of child organ and tissue donations in the mourning process and parents’ adjustment to loss: A comparative study of parents choosing to donate organs and those choosing not to donate. PhD Thesis, Tel Aviv University, Tel Aviv, Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Ashkenazi T, Guttman N. (2016) Organ and tissue donor parents’ positive psychological adjustment to grief and bereavement: Practical and ethical implications. Bereavement Care 35(2): 58–66. [Google Scholar]

- Bartucci MR. (1987) Organ donation: A study of the donor family perspective. The Journal of Neuroscience Nursing 19(6): 305–309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bauer P, Han Y. (2014) Parental perspectives of donation after circulatory determination of death in children: Have we really investigated the heart of the matter? Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 15(2): 171–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellali T, Papadatou D. (2006) Parental grief following the brain death of a child: Does consent or refusal to organ donation affect their grief? Death Studies 30(10): 883–917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellali T, Papazoglou I, Papadatou D. (2007) Empirically based recommendations to support parents facing the dilemma of paediatric cadaver organ donation. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing 23(4): 216–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntzen H, Bjork IT. (2014) Experiences of donor families after consenting to organ donation: A qualitative study. Intensive & Critical Care Nursing 30(5): 266–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan AL. (1995) The telltale heart: Public policy and the utilization of non-heart-beating donors. In: Arnold RM, Youngner SJ, Schapiro MPH, et al. (eds) Procuring Organs for Transplant: The Debate over Non-Heart-Beating Cadaver Protocols. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, pp. 207–218. [Google Scholar]

- Carduff EK. (2013) Realising the potential: Developing qualitative longitudinal methods for understanding the experience of metastatic colorectal cancer. PhD Thesis, The University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh. [Google Scholar]

- Charmaz K. (2006) Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide through Qualitative Analysis. London: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Christopherson LK, Lunde DT. (1971) Heart transplant donors and their families. Seminars in Psychiatry 3(1): 26–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cleiren MP, Van Zoelen AA. (2002) Post-mortem organ donation and grief: A study of consent, refusal and well-being in bereavement. Death Studies 26(10): 837–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot JJAM. (2016) Decision making by relatives of eligible brain dead organ donors. PhD Thesis, Radboud University, Nijmegen: Available at: http://hdl.handle.net/2066/159498 (accessed 10 December 2016). [Google Scholar]

- De Groot JJAM, van Hoek M, Hoedemaekers CWE, et al. (2015) Decision making on organ donation: The dilemmas of relatives of potential brain dead donors. BMC Medical Ethics 16(1): 64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Groot JJAM, Vernooij-Dassen M, Hoedemaekers C, et al. (2012) Decision making by relatives about brain death organ donation: An integrative review. Transplantation 93(12): 1196–1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicks SG, Ranse K, Northam H, et al. (2017. a) The development of a narrative describing the bereavement of families of potential organ donors: A systematic review. Health Psychology Open. Epub ahead of print 5 December DOI: 10.1177/2055102917742918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dicks SG, Ranse K, van Haren FMP, et al. (2017. b) In-hospital experiences of families of potential organ donors: A systematic review and qualitative synthesis. Health Psychology Open. Epub ahead of print April DOI: 10.1177/2055102917709375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Douglass GE, Daly M. (1995) Donor families’ experience of organ donation. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 23(1): 96–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth RM, Sproat GW, Morien M, et al. (1998) Acute bereavement services and routine referral as a mechanism to increase donation. Journal of Transplant Coordination 8(1): 16–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falomir-Pichastor JM, Berent JA, Pereira A. (2013) Social psychological factors of post-mortem organ donation: A theoretical review of determinants and promotion strategies. Health Psychology Review 7(2): 202–247. [Google Scholar]

- Frid I, Bergbom I, Haljamäe H. (2001) No going back: Narratives by close relatives of the braindead patient. Intensive and Critical Care Nursing 17(5): 263–278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frid I, Haljamäe H, Öhlén J, et al. (2007) Brain death: Close relatives’ use of imagery as a descriptor of experience. Journal of Advanced Nursing 58(1): 63–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulton J, Fulton R, Simmons R. (1977) The cadaver donor and the gift of life. In: Simmons R, Marine S, Simmons R. (eds) Gift of Life: The Social and Psychological Impact of Organ Transplantation. New York: John Wiley & Sons, pp. 338–376. [Google Scholar]

- Haney CA. (1973) Issues and considerations in requesting an anatomical gift. Social Science & Medicine 7(8): 635–642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland J, Thomson R, Henderson S. (2006) Qualitative longitudinal research: A discussion paper. Working paper no. 21, December London: Families & Social Capital ESRC Research Group. [Google Scholar]

- Holtkamp SC. (1997) The donor family experience: Sudden loss, brain death, organ donation, grief and recovery. In: Chapman J, Deiherhoi M, Wight C. (eds) Organ and Tissue Donation for Transplantation. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 304–322. [Google Scholar]

- Holtkamp SC. (2002) Wrapped in Mourning: The Gift of Life and Organ Donor Family Trauma. New York: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover S, Bratton S, Roach E, et al. (2014) Parental experiences and recommendations in donation after circulatory determination of death. Pediatric Critical Care Medicine 15(2): 105–111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby LH, Jaccard J. (2010) Perceived support among families deciding about organ donation for their loved ones: Donor vs nondonor next of kin. American Journal of Critical Care 19(5): e52–e61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacoby LH, Breitkopf CR, Pease EA. (2005) A qualitative examination of the needs of families faced with the option of organ donation. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing 24(4): 183–189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AMB. (2007) Those who give and grieve. Master’s Thesis, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AMB. (2011. a) Orchestrating an exceptional death: Donor family experiences and organ donation in Denmark. PhD Thesis, University of Copenhagen, Copenhagen. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AMB. (2011. b) Searching for meaningful aftermaths: Donor family experiences and expressions in New York and Denmark. Sites: A Journal of Social Anthropology and Cultural Studies 8(1): 129–148. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen AMB. (2016) ‘Make sure somebody will survive from this’: Transformative practices of hope among Danish organ donor families. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 30(3): 378–394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kesselring A, Kainz M, Kiss A. (2007) Traumatic memories of relatives regarding brain death, request for organ donation and interactions with professionals in the ICU. American Journal of Transplantation 7(1): 211–217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kinjo T, Morioka M. (2011) Narrative responsibility and moral dilemma: A case study of a family’s decision about a brain-dead daughter. Theoretical Medicine and Bioethics 32(2): 91–99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiss A, Bischoff P, Kainz M, et al. (2007) The experience of relatives asked for organ donation. The original project, obstacles, findings, and unexpected results. Swiss Medical Weekly 137(Suppl. 155): 128S–131S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- La Spina F, Sedda L, Pizzi C, et al. (1993) Donor families’ attitude toward organ donation. The North Italy Transplant Program. Transplantation Proceedings 25(1): 1699–1701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd-Williams M, Morton J, Peters S. (2009) The end-of-life care experiences of relatives of brain dead intensive care patients. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management 37(4): 659–664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long T, Sque M, Addington-Hall J. (2008) Conflict rationalisation: How family members cope with a diagnosis of brain stem death. Social Science & Medicine 67(2): 253–261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long T, Sque M, Payne S. (2006) Information sharing: Its impact on donor and nondonor families’ experiences in the hospital. Progress in Transplantation 16(2): 144–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- López Martínez JS, Martín López MJ, Scandroglio B, et al. (2008) Family perception of the process of organ donation. Qualitative psychosocial analysis of the subjective interpretation of donor and nondonor families. The Spanish Journal of Psychology 11(1): 125–136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maloney R, Altmaier EM. (2003) Caring for bereaved families: Self-efficacy in the donation request process. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings 10(4): 251–258. [Google Scholar]

- Manuel A, Solberg S, MacDonald S. (2010) Organ donation experiences of family members. Nephrology Nursing Journal 37(3): 229–237. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marck CH, Neate SL, Skinner M, et al. (2016) Potential donor families’ experiences of organ and tissue donation-related communication, processes and outcome. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 44(1): 99–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills L, Koulouglioti C. (2016) How can nurses support relatives of a dying patient with the organ donation option? Nursing in Critical Care 21(4): 214–224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morton JB, Leonard DRA. (1979) Cadaver nephrectomy: An operation on the donor’s family. The British Medical Journal 1(6158): 239–241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neidlinger N, Gleason B, Cheng J. (2013) Honoring deceased donors with a unique family-designed statement followed by a moment of silence: Effect on donation outcomes. Progress in Transplantation 23(2): 188–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neimeyer RA, Klass D, Dennis MR. (2014) A social constructionist account of grief: Loss and the narration of meaning. Death Studies 38(6–10): 485–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Northam HL. (2015) Hope for a peaceful death and organ donation. PhD Thesis, University of Canberra, Canberra, ACT, Australia. [Google Scholar]

- Painter LM, Langlands JM, Walker JI. (1995) Donor families experience of organ donation: A New Zealand study. The New Zealand Medical Journal 108(1004): 295–296. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. (2010) Making sense of the meaning literature: An integrative review of meaning making and its effects on adjustment to stressful life events. Psychological Bulletin 136(2): 257–301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. (2017) Distinctions to promote an integrated perspective on meaning: Global meaning and meaning-making processes. Journal of Constructivist Psychology 30(1): 14–19. [Google Scholar]

- Pearson IY, Bazeley P, Spencer-Plane T, et al. (1995) A survey of families of brain dead patients: Their experiences, attitudes to organ donation and transplantation. Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 23(1): 88–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pelletier M. (1992) The organ donor family members’ perception of stressful situations during the organ donation experience. Journal of Advanced Nursing 17(1): 90–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]