Abstract

Objective:

This systematic review presents evidence regarding factors that may influence the patient’s subjective experience of an episode of mechanical restraint, seclusion, or forced administration of medication.

Method:

Two authors searched CINAHL, PubMed, SCOPUS, Web of Science, and Psych-Info, considering published studies between 1 January 1992 and 1 February 2016. Based on the inclusion criteria and methodological quality, 34 studies were selected, reporting a total sample of 1,869 participants.

Results:

The results showed that the provision of information, contact and interaction with staff, and adequate communication with professionals are factors that influence the subjective experience of these measures. Humane treatment, respect, and staff support are also associated with a better experience, and debriefing is an important procedure/technique to reduce the emotional impact of these measures. Likewise, the quality of the working and physical environment and some individual and treatment variables were related to the experience of these measures. There are different results in relation to the most frequently associated experiences and, despite some data that indicate positive experiences, the evidence shows such experiences to be predominantly negative and frequently with adverse consequences. It seems that patients find forced medication and seclusion to be more tolerable than mechanical restraint and combined measures.

Conclusions:

It appears that the role of the staff and the environmental conditions, which are potentially modifiable, affect the subjective experience of these measures. There was considerable heterogeneity among studies in terms of coercive measures experienced by participants and study designs.

Keywords: coercion, restraint, seclusion, forced medication, patient perceptions, mental health

Abstract

Objectif:

Cette revue systématique présente les données probantes concernant les facteurs qui peuvent influencer l’expérience subjective du patient à l’égard d’un épisode de contention mécanique, d’isolement ou d’administration forcée d’un médicament.

Méthode:

Deux auteurs ont recherché les bases de données CINAHL, PubMed, SCOPUS, Web of Science, et Psych-Info, en examinant les études publiées entre le 1er janvier 1992 et le 1er février 2016. Selon les critères d’inclusion et la qualité méthodologique, 34 études ont été choisies, portant sur un échantillon total de 1 869 participants.

Résultats:

Les résultats ont indiqué que l’offre d’information, le contact et l’interaction avec le personnel, et une communication adéquate avec les professionnels sont des facteurs qui influencent l’expérience subjective de ces mesures. Un traitement humain, le respect, et le soutien du personnel sont également associés à une meilleure expérience, et le débreffage est une importante procédure/technique pour réduire l’effet émotionnel de ces mesures. De même, la qualité de l’environnement de travail et physique ainsi que certaines variables individuelles et liées au traitement étaient reliées à l’expérience de ces mesures. Les résultats diffèrent relativement aux expériences les plus fréquemment associées, et, malgré certaines données qui indiquent des expériences positives, les données probantes montrent que ces expériences sont principalement négatives, et qu’elles ont fréquemment des conséquences indésirables. Il semble que les patients trouvent la médication forcée et l’isolement plus tolérables que la contention mécanique et les mesures combinées.

Conclusions:

Il semble que le rôle du personnel et des conditions environnementales, qui sont potentiellement modifiables, affecte l’expérience subjective de ces mesures. Il y avait une hétérogénéité considérable parmi les études en ce qui a trait aux mesures coercitives expérimentées par les participants et aux méthodes des études.

The current models and paradigms in mental health care are oriented towards the goals of recovery and self-determination for the user, and explicitly propose the reduction of coercive measures in the treatment of severe mental disorders. Forced medication, seclusion, and mechanical restraint in theory are intended to protect patients and those around them but the use of these measures restricts freedom and conflicts with the ethical principle of patient autonomy. These coercive measures also present risks due to their side effects’; for example, forced medication may be associated with hypotension1 and bronchospasms.2 These measures are even more problematic when used repeatedly3 and in combination—for example, when seclusion or forced medication is combined with physical or mechanical restraint, which can become extremely traumatic, causing physical and psychological harm to both patients and staff,4 and leading to serious side effects, including death.5

The use of coercive measures is controversial due to the lack of consensus regarding the choice of coercive method, its practice, registration, and control, and the core issue remains as to which is the best intervention(s) to prevent the application of these measures.6–8 Reduction rates in restraint have been achieved through multimodal interventions,9 which include several strategies to prevent and control disturbed behaviors without using restraint measures. Decreases in seclusion-restraint rates have been found in different institutions and countries that have applied the 6 core strategies:10–14 improving leadership, training staff, monitoring the use of restraint, involving consumers and family, using tools to reduce episodes of seclusion or restraint, and analyzing past events. In addition, the intervention, based on the “safewards”15 model developed by Bowers, has shown a significant reduction in restraint measures in a recent cluster randomized trial.16 Nevertheless, there are few studies on patient experiences of these measures and the factors that influence there experiences.

In recent years, the shared decision making process and the involvement of patients in their treatment have emerged with great force in the healthcare system, with reference to the process of taking control and responsibility for life, incorporating the goals of self-sufficiency, dignity, respect, and membership in and contribution to the community.17 It is at this point that the subjective experiences of the patients about their treatment after experiencing a coercive measure acquires a special importance, since it represents a central theme regarding the quality of the attention that mental health services are trying to offer.18 Some qualitative and quantitative studies have explored the subjective experiences, and related variables, of the use of coercive measures on patients admitted to mental health hospitalization units.19–22 Although there are other reviews on the subjective experiences of patients after the application of coercive measures,23 to our knowledge, no integrated results have focused on the factors that influence this experience. An understanding of the factors affecting the subjective experience of patients may help to improve the functioning of psychiatric units and thus improve patient satisfaction with the treatment. This understanding could also eventually contribute to improving programs aimed at preventing the use of coercive measures.

The objective of this study was to carry out a systematic review of the factors that influence the patient’s subjective experience in relation to the application of coercive measures in mental health hospitalization settings. The secondary objective was to review the results concerning the types of subjective experiences reported by the patients and the outcomes, comparing the different coercive measures and considering the patient’s subjective experience.

Methods

This review followed the PRISMA guidelines24 and the protocol was registered in PROSPERO (registration number: 42016036669).

Eligibility Criteria

Participants

The review considered only: 1) studies carried out in samples of patients exposed to physical or mechanical restraint, seclusion, or forced medication; 2) studies where the coercive measure was applied during psychiatric hospitalization; and 3) studies with a qualitative or quantitative assessment about the subjective experience in relation to the coercive measures selected. Studies were excluded when: 1) patients were under 18 y old; 2) patients were admitted into non-mental health wards, specialized facilities for substance abuse, or psychogeriatric facilities; or 3) the study only accounted for the experience of the staff.

Intervention or exposure

We considered for inclusion studies that collected information of the factors associated with the subjective experience of patients exposed to mechanical restraint, seclusion, or the forced administration of medication.

Outcomes

The primary outcomes were factors that affect the patient’s subjective experience of the coercive measures, considering subjective experience to include all those perceptions, feelings, perspectives, impressions, or opinions that the patients have with respect to the coercive measures. The secondary outcomes were: 1) the types of subjective experiences reported by the patients, and 2) the different measures (mechanical restraint, seclusion, and forced medication) considered comparatively in relation to the patient’s subjective experience.

Search Strategy and Selection of Studies

The aim of this systematic review was to identify studies published between 1 January 1992 and 1 February 2016 in the English or Spanish languages. A 25-y time period was chosen, as it was considered to be sufficiently broad and representative for the purpose of the review. We searched the following databases for relevant articles: CINAHL, PubMed, SCOPUS, Web of Science, and Psych-Info. We used the following subject headings and search terms to identify potential articles for inclusion: “mental health or psychiat* (in all fields) AND restraint or seclusion or isolation or involuntary medication or forced medication or coercion or coercive measures (in all fields) AND patient experience or patients experiences or patient perspective or patients perspectives or patient perception or patients perceptions or patient preference or patients preferences or satisfaction (in all fields).”

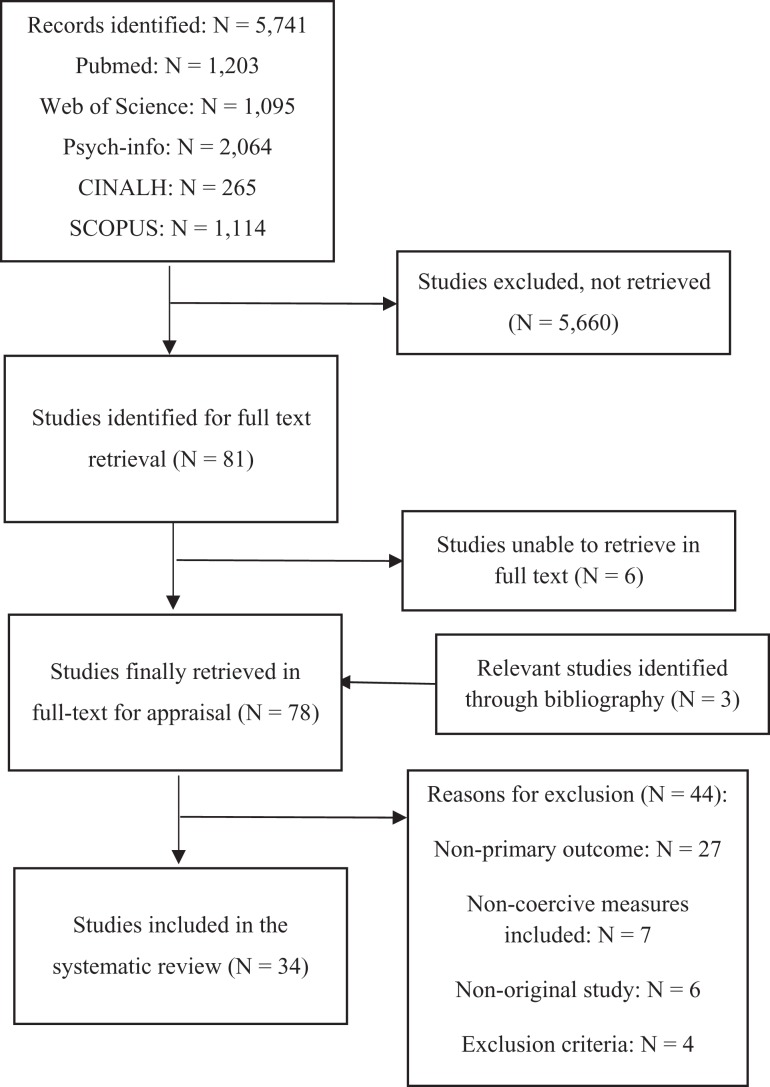

Study selection was carried out independently by 2 reviewers (CAS and JGP) between March and September 2016. A second review was conducted between August and September 2017. The results of the search were first screened by title and abstract, and where doubt existed, the complete text was revised. Studies that met the inclusion criteria were then selected. If there were discrepancies for the inclusion of any study, an agreed decision was made between the 2 reviewers. After our initial search, we also manually reviewed the reference lists of selected articles. The details of the search, including the reasons for exclusions, are presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of included studies in the systematic review.

Methodological Quality and Data Extraction

To ensure the quality of the studies included in the analysis, we used Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP),25 a standardised checklist on the most relevant characteristics of different types of studies that provides a score for each study. For qualitative studies, the scale presents 10 items; for case-control studies, 11 items; for longitudinal studies, 12 items; and for randomized control trials, 11 items. We gave a “high quality” rating to studies with ≥70% of items satisfied; “medium quality” to studies with ≥50% and <70% of items satisfied, and “low quality” to studies with <50% of items satisfied. Any discrepancy between the reviewers was resolved through discussion. All the selected studies passed the quality assessment.

Data were extracted independently from each of the 34 studies by 2 reviewers (CAS and JGP) regarding: 1) country of origin, 2) setting, 3) sample, 4) coercive measure used, 5) design and methodology, 6) the factors that affect the experience of the measure, 7) the subjective experience associated with the measure, and 8) comparison between measures.

Data Synthesis

Given the diversity of studies in terms of design, type of sample, type of coercive measure used, and scope of study, the narrative method was considered the most appropriate procedure by which to present the results. The data were grouped by thematic categories. Quantitative data were also included in the data synthesis.

Results

Characteristics of Included Studies

Thirty-four articles that met the inclusion criteria were identified and passed our quality assessment as high-quality studies (see flow chart in Figure 1). The studies included a total of 1,869 participants. Most of the studies were set in different acute psychiatric wards in hospitals (28), as well as in forensics wards (2), community mental health services (regarding the experience during hospital admission) (2), a mixed setting (inpatient units in a general hospital and forensic wards) (1), and a long-term care organization (1). The distribution by country was as follows: United States (8), Canada (4), Netherlands (4), Australia (3), Germany (3), Sweden (2), United Kingdom (2), Finland (2), Norway (2), South Africa (2), China (1), and Austria (1).

In relation to the typology of the study, 15 used qualitative methods, with structured or semi-structured interviews (14) and the auditing (1) for data collection. Another 13 studies were quantitative, of which 8 were cross-sectional, 4 longitudinal, and 1 an intervention study. The methodology of the remaining 6 studies was mixed (qualitative and quantitative). Regarding the types of coercive measures used by the staff, 16 studies used seclusion, 5 studies used mechanical restraint, and 1 used forced medication as the only measure. Eight studies took into account 2 measures, and 4 studies included the use of 3 measures. More information is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Details of Included Studies

| Principal Author, Year, and Country | Setting | Sample | Coercive Measure | Design and Method | Factors Affecting the Experience of the Measure | Subjective Experience Associated With the Measure | Comparison between Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fugger et al.19 2016 Austria | Acute psychiatric ward in public general hospital | N = 47 | Mechanical restraint | Longitudinal study of 18 months (structured interviews with 4 measurement scales: MacArthur, Visual Analogue Scale [VAS], Impact of Event Scale–Revised version [IESR], Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale) | The medication administered affects the experience of the measure: It can lead to better tolerance and acceptance of the measure. On the other hand, it can induce a state of impotence, depression, and even amnesia. | 36 patients reported mood disturbances (depression and impotence) between 4 to 6 d after the measure. About half of patients perceived high levels of coercion. 29.4% met criteria for a PTSD diagnosis prior to discharge and 22.2% after approximately 4 wk after discharge. | Preferences for the use of medication v. mechanical restraint. |

| Mielau et al.21 2015 Germany | Outpatient units of the departments of psychiatry and psychotherapy | N = 46 | Mechanical restraint | Cross-sectional study (structured interviews with 2 measurement scales of perceived coercion: adaptation of the McArthur Admission Experience Survey [AES] and Coercion Experience Scale [CES]) | A higher number of self-experienced coercive interventions and low levels of perceived fairness and effectiveness of treatment were associated with a worse experience. | AES subscale 1 summarizes AES factors “fairness” and “effectiveness” (2.20 score, range 1 to 5). AES subscale 2 score that combines AES factors “perceived coercion,” “process exclusion,” and “negative pressures” as the negative aspects of patients’ perception of their treatment (3.04 score, range 1 to 5). CES score of 3.32, range (1 to 5). In each case, a higher score means more perceived coercion. | Participants expressed preference for involuntary medication v. mechanical restraint. Seclusion is considered as an alternative measure to mechanical restraint. |

| Holmes et al.22 2015 Canada | Forensic psychiatric ward | N = 13 | Seclusion | Qualitative study (semi-structured interviews) | A clear understanding on the part of the patients regarding the reasons that led to the use of seclusion affects positively the experience of seclusion. A post-seclusion debriefing is recommended. | Experiences during seclusion: feelings of being “abandoned” by nursing staff. Post-seclusion experiences: some patients found seclusion to be a negative experience but most understood why seclusion rooms would be necessary in a forensic psychiatric setting. | |

| Ling et al.20 2015 Canada | Acute psychiatric ward | N = 55 | Mechanical restraint | Qualitative study (patient debriefing and comments form) | Debriefing guided by a structured form allows inpatients and staff to develop a greater understanding of restraint events. | During restraint events: In general, restraint was a negative experience. Fear and rejection were common feelings. Post-restraint events: loss of trust was mentioned and also feelings of victimization and resentment and lack of information during the process. In general, restraint was frequently a negative experience, but it had no later consequences. | |

| Lanthén et al.26 2015 Sweden | Psychiatric outpatient units, as well as patient organizations | N = 10 | Mechanical restraint | Qualitative study (one-on-one interviews) | The physical presence and an appropriate attitude of the staff are perceived as positive. The debriefing could help the patient to process the event. | Positive experience: calm and safety. Negative experience: powerlessness and feeling excluded or exposed. | |

| Ezeobele et al.27 2014 USA | Acute psychiatric ward | N = 20 | Seclusion | Qualitative study (semi-structured interviews) | Lack of therapeutic communication skills, incitements, and provocation from the staff affect the experience of seclusion. | 60% of the participants perceived the seclusion as penalizing and as a negative experience. 20% of the participants experienced seclusion as positive. Seclusion seen as a room to “meditate and pray.” | |

| Faschingbauer et al.28 2013 USA | Acute psychiatric ward | N = 12 | Seclusion | Qualitative study (in-depth unstructured interviews) | Lack and/or difficulties in interpersonal communication before, during, and after the event affect the experience of seclusion. | Patients negative experiences: anxiety, anger, hurt, and humiliation. Patients reported feeling ignored in seclusion. Also perceived their needs were not met and their rights were violated. Some patients perceived that they did not need seclusion and felt this was used as punishment. | |

| Larue et al.29 2013 Canada | Acute psychiatric ward | N = 50 | Seclusion/ Mechanical restraint | Mixed methods (merging qualitative and quantitative data) | The intensive support by care providers and the less restrictive environment (possibility to leave the seclusion area for patients admitted voluntarily) could contribute to a positive perception. | Positive experiences: some patients found the measures helpful during difficult, loss-of-control situations. Negative experiences: some patients found the loss of freedom difficult (46%), the absence or loss of objects (23%), and humiliation (12%) were the most frequent experiences. | |

| Steinert et al.30 2013 Germany | Three general psychiatric units | N = 60 | Seclusion/ Mechanical restraint | One-year follow-up of a randomized controlled study. Semi-structured interviews by telephone or face to face. The Coercion Experience Scale [CES] was the main outcome. | 57.0% of patients would have preferred more contact with staff during the measure. Patients mentioned that what alleviated distress more frequently was contact with staff (53.3%) and having personal objects nearby (16.7%). | 55.0% of patients judged the measures as justified (67.7% seclusion and 41.4% restraint) and 58.3% indicated that the measure had some positive effects, mainly calming down. The feelings most frequently associated with the measure were: helplessness (71.7%), tension (63.3%), being at the mercy of others (63.3%), rage (58.3%), fear (56.7%), desperation (48.3%), anger (48.3%), and disappointment (46.7%). | In the original study, there were no significant differences between seclusion and restraint in CES ratings. In the follow-up, CES scores were more negative for mechanical restraint on 6 of the 9 items. |

| Whitecross et al.31 2013 Australia | Acute inpatient psychiatric service | N = 31 | Seclusion | Interventional study with control group, comparing debriefing after seclusion with usual intervention. Impact of Events—Revised (IES-R) as dependent variable. | Counseling after seclusion did not significantly reduce the trauma experience. | Approximately 47% reported trauma symptoms consistent with “probable post-traumatic stress disorder” (IES-R total score, >33), but there was no difference in trauma experience between groups. | |

| Georgieva et al.32 2012 Netherland | Acute psychiatric ward | N= 125 | Seclusion, involuntary medication, combined seclusion and medication, and combined seclusion and mechanical restraint | Prospective study using as the independent variable the type of coercive intervention; and as dependent variables: effectiveness and subjective distress (assessed with CES and an VAS) | The combination of coercive measures was related to a major subjective coercive experience in the isolation scale of CES and physically adverse effects. Women and younger people reported that they had experienced coercive interventions as more burdensome. | No detailed information is provided. The subjective level of coercion at the start of the measures had a mean (SD) of 4.03 (3.25) in the total sample. | Involuntary medication was experienced as the least distressing measure. There were no differences in the effectiveness of the different measures. |

| Kontio et al.33 2012 Finland | Six acute closed wards in 2 psychiatric hospitals | N = 30 | Seclusion/ Mechanical restraint | Qualitative study (open-ended focused interview questions) | Humane treatment, being able to talk with external agents about the experience, more information about the reason for and duration of the measure, written information about their treatment plan, and an environment with better conditions were the topics indicated. | Previous experiences: mainly dissatisfaction with the treatment from staff and the lack of information. Experiences during the event: anger, fear, loneliness, security, and boredom. Experiences after the event: mainly negative but also positive. | |

| Haw et al.34 2011 UK | Forensic rehabilitation wards | N = 57 | Mechanical restraint/ Seclusion/ Involuntary medication | Mixed methods (merging qualitative and quantitative data) | Factors that can affect the experience of these coercive measures: Doing these measures the most pleasant way possible, giving details of how they will proceed and using the preferences of patients, improving communication between patients and staff, and giving greater importance to the comfort and dignity of the patient. | Negative experiences: fear, loss of dignity, anger, humiliation, shame, loneliness. Some positive experiences: time for quiet reflection, prevention of violence to self and others, opportunity to regain control. 56.4% had a negative experience with seclusion; 16.6% positive. 53.6% had a negative experience with mechanical restraint; 16.0% positive. 50.0% had a negative experience with intramuscular medication; 36.0% positive. | Comparing preferences between forced medication and seclusion: 52.6% preferred medication, 36.8% preferred seclusion, 7.0% didn’t know, and one 1.8% expressed no preference. |

| Iversen et al.35 2011 Norway | Acute psychiatric ward | N = 56 | Seclusion | Cross-sectional study (structured interviews). The patients’ experiences were assessed at discharge from the seclusion area with an 8-item treatment satisfaction questionnaire with a Visual Analogue Scale [VAS-scale].) | The respondents who were admitted voluntarily reported significantly better experiences with regard to the help received, support from the staff, and respectful treatment. | Most of the mean scores of patient experiences measured after their stay at the seclusion area were positive (≥66 mm) with regard to support from staff, respectful treatment, and feeling safe. Also, their overall patient experience was positive (≥330 mm). | |

| Mayers et al.36 2010 South Africa | Three acute psychiatric wards | N = 43 | Mechanical restraint/ Seclusion/ Involuntary medication | Qualitative study (semi-structured interviews and 2 focus groups) | Restraint, independently of the type, was experienced as very stressful, particularly if debriefing and reorientation were not applied when the person had returned to the ward or had his/her sedation reduced. | Issues of abuse and human rights violations emerged as strong themes in both in- and outpatient settings. Seclusion was seen as punishment by 28 respondents (78%). 57% who had been sedated during hospitalization described their sedation as being necessary. Restraint was considered necessary by 33%. | Sedation was found to be less traumatizing and distressing than seclusion and restraint for all respondents. |

| Keski-Valkama et al.37 2010 Finland | The general psychiatric inpatient units of 2 hospitals Two forensic psychiatric hospitals | N = 38 N = 68 | Seclusion | Longitudinal study (structured interviews) | The forensic group perceived seclusion as a form of punishment more often than non-forensic patients. The patients proposed to improve the experience of seclusion: more interaction with the staff (27.2%), less regulated use of toilet facilities and freedom to take care of their own hygiene (25.5%), more comfortable bed and bedclothes (21.8%), smoking possibilities (14.5%), more therapeutic furnishing (12.7%), alarm bell (10.9%), shorter duration of seclusion episodes (9.1%), and ordinary clothing (7.3%). | 57.3% of the patients had a negative experience and 66.6% experienced it as a punishment. Comparatively, 50.6% experienced the measure as beneficial. | |

| Veltkamp et al.38 2008 Netherland | Three acute psychiatric ward of 2 hospitals | N= 104 | Seclusion/ Involuntary medication | Cross-sectional study (structured interviews with 2 measurement scales and one Visual Analogue Scale [VASs]) | Understand the measures and why the measure was applied was related with the opinion of being more effective. | Seclusion: Positive aspects: rest, security, and possibility of sleep were frequently mentioned (45%). Negative aspects: feeling alone and locked in was the most frequently named (30%). One-third (34%) referred no positive aspects. Medication: Positive aspects: calming. Negative aspect: feeling powerless and aversive side effects. | The same number of patients preferred seclusion and medication and the 2 measures were equal in perceived averseness and efficacy. |

| Ntsaba et al.39 2007 South Africa | Acute psychiatric ward | N = 11 | Seclusion | Qualitative study (semi-structured interviews) | Insensitive or unfriendly staff behavior, lack of information during the measure, and the lack of response to the demands were related to a negative experience. | Negative experiences: punishment and the creation of an environment of human rights violations. Positive experiences: sense of calmness. | |

| Stolker et al.40 2006 Netherlands | Acute psychiatric ward | N = 54 | Seclusion | Mixed methods (semi-structured interviews and the Patient View-of-Seclusion Questionnaire) | Patients who initially resided in rooms with multiple beds had a more favorable view of seclusion. | Score of 3.1 in negative items and 2.4 in positive ones. This result is associated with a positive perception of seclusion in this particular ward. | |

| Chien et al.41 2005 China | Two acute psychiatric wards | N = 30 | Mechanical restraint | Qualitative study (semi-structured interviews) | Positive factors: caring attitudes and behavior of the staff. Negative factors: inability of staff to satisfy patients’ needs for concern, empathy, active listening, and information about restraint during and after its use. The negative feelings were strong if they were newly admitted and not familiar with the ward environment. | 20 participants (66.7%) expressed positive feelings related to mechanical restraint. 16 (53.3%) participants expressed negative experiences and frustration. 11 (36.7%) participants felt anxious and frightened because they felt unable to protect themselves when being restrained. | |

| Wynn et al.42 2004 Norway | Acute psychiatric ward | N = 12 | Mechanical restraint (N = 7 with involuntary medication) | Qualitative study (one-on-one interviews) | Patients with psychotic symptoms were more understanding of staff’s decision to apply the measure. The presence of the staff and the systematical debriefing of patients after restraint affected the experience of the measure. | Negative experiences: anxiousness, anger, and hostility. Also angry, fearful, and distrustful of staff. Positive experiences: some patients indicated that they calmed down and others only after additional medication. | |

| Holmes et al.43 2004 Canada | A specialized psychiatric care unit located in a psychiatric hospital | N = 6 | Seclusion | Qualitative study (one-on-one interviews) | The limited contact with staff and the perceived neglect affect the experience (related with needs as eating, elimination, and security). | Negative experiences: fear, anger, sadness, shame, and feeling abandoned. One patient experienced seclusion as positive. | |

| Meehan et al.44 2004 Australia | Two acute inpatient units and a medium secure unit | N = 29 | Seclusion | Cross-sectional study (structured interviews: Heymans’s Attitude Towards Seclusion Survey) | More communication and dialogue between nurses and patients may improve the experience of seclusion. | Negative experiences: feeling punished (92%), frustrated (96%) and angry (85%). Positive effects: calm (67%), able to express their feelings in a non-disruptive way (64%), and able to feel better (28%). | |

| Hoekstra et al.45 2004 Netherlands | Long-term Adult Care Organization | N = 7 | Seclusion | Qualitative study (semi-structured interviews) | Importance of human contact. Some patients feel uncomfortable when they are not allowed to wear their own clothes. Some patients indicate the importance of talking about what happened after the measure. | Patients mainly report negative effects: Powerlessness with regard to nursing staff, loneliness, and self-confidence impaired. | |

| Haglund et al.46 2003 Sweden | Five locked wards at a department of psychiatry for inpatient care | N = 11 | Involuntary medication | Qualitative study (semi-structured interviews) | An unequal positioning in the therapeutic relationship, placing the patient in a state of dependence on the professional, with no capacity to participate in decision making affect negatively the experience of the measure. | 7 patients (64.7%) expressed experiences of physical or psychological discomfort after the measure. 3 patients (27.3%) approved of it retrospectively. The measure was frequently experienced as a punishment, with manifestations of rage, agitation, frustration, irritation, sadness, and panic. | |

| Bonner et al.47 2002 UK | Acute psychiatric ward | N = 6 | Mechanical restraint | Qualitative study (semi-structured interviews) | The ward atmosphere and lack of staff communication negatively affect the experience. | Negative experiences: fear, shame, and feeling ignored before and, above all, after mechanical restraint. 3 patients (50%) reported that being restrained brought back memories of previous violent incidents, including, in one case, the experience of having been raped, and in another case the experience of having been abused in childhood. | |

| Meehan et al.48 2000 Australia | Two open acute care units | N = 12 | Seclusion | Qualitative study (semi-structured interviews) | Give information to patients, increasing interaction during seclusion, taking into account privacy and debriefing can decrease the emotional impact of the measure. | Mainly negative experiences: perceived arbitrary and perception that seclusion was more beneficial to the staff, perceptions of punishment, abandonment, fear, isolation and depression. Positive experiences: secure environment in which to gain control. | |

| Martinez et al.49 1999 USA | Inpatient psychiatric hospital | N = 53 | Seclusion | Mixed methods (merging qualitative and quantitative data with interviews and focus group) | Increased communication with staff, physical presence of staff, and being treated with respect were factors suggested by patients that could improve the experience of seclusion. Some patients also indicated that the involvement of family members could be beneficial. | Negative experiences were predominant: 61.7% felt neglected, 63.8% felt fearful, 54.3% felt loss of control, 61.2% felt vulnerable, 64.4% felt worthless, 56.3% felt bad, and 76.5% felt punished. Some patients expressed positive experiences: 27.7% felt safe, 36.9% felt a sense of control, 24.5% felt protected, 26.6% felt valuable, 27% felt good, and 15.7% felt cared for. | |

| Ray et al.50 1996 USA | 285 organizations received mail surveys | N = 560 | Mechanical restraint/ Seclusion | Cross-sectional study: A mail survey regarding hospital treatment (36 true/false items) and restraint and seclusion use (21 true/false items) and the type of treatment received (7 yes/no items) | The staff efforts to calm the patients down or to resolve the problems of the patients before the use of restraint or seclusion was associated with a positive experience of the measure. | Most patients perceived the measures as negative. 94% of these individuals reported at least one complaint about the use of restraint and seclusion. The measures were mainly experienced as unnecessary, premature, and punitive. A small percentage of respondents offered positive comments, indicating that their behavior was dangerous, that they had been treated fairly, and that they benefited from the use of the intervention. | |

| Naber et al.51 1996 Germany | Two locked wards of a university psychiatric hospital | N = 40 | Mechanical restraint/ Involuntary medication | Mixed methods (merging qualitative and quantitative data with semi-structured interviews) | A low insight into the disease was significantly associated with a negative experience of these measures. | 48% evaluated these measures as necessary or positive, 23% as negative, and 30% were indifferent. Fear and impotence were the predominant emotions provoked by coercive measures. | The results suggest that mechanical restraint was more unpleasant than injections but this result was not significant. |

| Outlaw et al.52 1994 USA | Three Veterans Administration Medical Centers with psychiatric inpatient units | N = 84 | Mechanical restraint/ Seclusion | Mixed methods (semi-structured interviews) | The correlation between previous admissions to a psychiatric hospital and the controllability dimension was significant (r = −26, P = 0.03). Patients who had experienced a previous admission to a psychiatric hospital gave answers that indicated that they believed that they could control the behaviors that lead to restraint. | The patients attributed the causes of the restraint to factors that were external, uncontrollable, and unstable. | |

| Mann et al.53 1993 USA | A voluntary psychiatric unit in a not-for-profit community teaching hospital | N = 50 | Seclusion | Cross-sectional study (The questionnaire was based upon an instrument previously designed to assess patient perceptions of the use of seclusion rooms objectively.) | Some individual variables, such as being categorized as non-compliant, being the first time in seclusion, more episodes of seclusion, and substance abuse correlated with a negative experience of the measure. | More than 60% felt safe during seclusion, and more than 40% felt treated as prisoners and were afraid of being secluded again. | |

| Tooke et al.54 1992 USA | Acute psychiatric ward | N = 19 | Seclusion | Cross-sectional study (structured interviews: Heyman’s Attitude Towards Seclusion Survey) | Access to open activities, presence of staff during the measure, discontinuation of the measure, wearing own clothes, and a comfortable room were indicated as proposals to improve the seclusion. | Patients experienced more negative than positive feelings. The most associated negative feelings were: confused (91%), helpless (91%), and hopeless (91%). The most associated positive feelings were: in control (50%), safe (47%), and relieved (44%). | |

| Norris et al.55 1992 USA | Two short-term adult units in a university hospital center | N = 20 | Seclusion | Cross-sectional study (structured interviews with 2 instruments developed by the investigator) | The behavior of the staff is important before and during the measure and can promote pleasant feelings. Debriefing can be one of the most important means to lessen the emotional impact of the measure. The physical environment is perceived as important. | Many negative feelings associated with seclusion in most of the sample: fear, depression, degradation, dehumanization, humiliation, loneliness, anger, and guilt. The study does not refer to the presence of positive experiences or feelings. |

Factors Affecting the Subjective Experience of the Coercive Measures

The data were reduced and categorised according to the following categories: 1) Provision of information, presence of or interaction with staff, and adequacy of communication with professionals; 2) the physical environment of the psychiatric ward; 3) respect, humane treatment, and support from staff; 4) debriefing; 5) Individual characteristics of patients and their admission or treatment.

Provision of information, presence of or interaction with staff, and adequacy of communication with professionals

Twenty studies indicated that the provision of information, the presence of or interaction with staff, and the adequacy of communication with professionals influenced the subjective experience of the coercive measure(s). Ten of these studies indicated that contact and the presence of staff during the process influences the subjective experience, making the coersive measure less aversive.26,30,33,37,42,43,45,48,49,54 One study49 indicated that the presence of relatives was associated with a more positive experience, and 2 other studies mentioned that staff trying to calm or solve the user’s problems before the application of the coercive measure also had a positive influence.35,50 Seven studies indicated that providing adequate information about the measure26,34,42,48 and making sure that the patient understands the reasons for adopting the measure,38 or the staff’s failure to explain them,36,39,47 affected the experience. Furthermore, adequate communication41,44,49 or a lack of communication or communication skills27,28,39,47 was also noted as a factor that may influence the experience of coercive measures in 7 studies.

The physical environment of the psychiatric ward

Eleven studies cited the physical environment as an influential factor in the subjective experience of coercive measures. This concept encompasses a range of concepts, as indicated by Van der Schaffer et al.,56 including the comfort of the rooms29,33,34,37,54,55 and/or furniture,33,37 the physical environment,29,33,34,55 wearing own clothes,37,45,54 the presence of personal objects,29,30 the regulated use of the bathrooms,33,37 pronounced inactivity,33,48 the ward atmosphere,47 noise,48 hostile environment,34 and privacy.48 In one study,40 it was found that even the physical environment not directly related to the measure may influence the perception of seclusion. The authors further suggested that seclusion was associated with a positive experience in patients who stayed in rooms with multiple beds, and the authors speculate that the previous discomfort and lack of privacy could be the reason why seclusion has been frequently experienced as positive.

Respect, humane treatment, and support from staff

Ten studies reported that respect, humane treatment, and support from staff influenced the experience of the measure, with several terms related to a better experience of the measure: respect,35,49 professional and pleasant behavior of the staff,26,39 humane treatment,33 treatment fairness,21 taking into account the dignity of the patient,34 empathy,41 a position at an equal level,46 and support from the staff.35

Debriefing

In 8 studies,20,22,26,36,42,45,48,55 the use of debriefing was indicated as an important technique for reducing the emotional impact of the measure. In 4 of these studies,26,48,45,55 patients reported their desire to talk about what happened as a way of processing the experience. In 3 studies,26,48,36 debriefing was suggested to prevent subsequent trauma and distress. However, one of the methodologically more comprehensive studies revealed that debriefing after seclusion did not significantly reduce the trauma experience.31 The study by Ling et al.20 indicated that debriefing facilitated a greater understanding of restraint events, with the same conclusion reached by Holmes el al;22 albeit, their data was from the staff reports. Finally, the study by Wynn et al.42 recommends debriefing to improve patients’ lack of understanding of the reasons why the measure was adopted.

Individual characteristics of patients and their admission or treatment

A total of 7 studies mentioned that characteristics at the level of the individual, including their admission and treatment, were associated with a negative experiences of the coersive measure. In one study,51 patients with low insight into the disease perceived coercion more strongly than patients with high levels of insight. In another study, poor adherence to treatment and multiple previous episodes of coercive measures53 were also correlated with a negative experience. One study32 found that a younger age and female gender were associated with more burdensome coercive measures. Other factors were associated with more positive experiences, including psychotic symptoms,42 voluntary admission,35 and previous admission in the unit.52 Yet, a history of substance abuse was related to a negative experience,53 and the consumption of prescribed medication had both positive and negative effects.19 Finally, one study32 found that application of combined measures was associated with a higher perception of coercion.

Characteristics of Experiences Raised by Coercive Measures

Twenty-six studies reported predominantly negative experiences associated with the measures (irrespective of the measure applied).19–22,26–28,30,31,33,34,36,37,39,42–50,52,54,55 The most frequent experiences reported were: 1) fear, anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)19,20,28,30,31,33,34,41,42,46–49,51,53,55; 2) powerlessness, abandonment, distrustfulness or loneliness20,22,26,28,30,33,34,38,42,45,47–49,55; 3) punishment, maltreatment, or pain27,28,36,37,39,44,46,48–50,53; 4) anger, rage, or resentment20,28,30,33,34,42–44,46,55; 5) depression, impotence, or sadness19,30,43,44,46,51,54,55; 6) humiliation, degradation, or shame34,47,28,29,55; and 7) loss of freedom, or coercion.19,21,29 However, 6 studies found more positive than negative experiences,35,38,40,41,51,53 and one study showed an equal number of positive and negative experiences29 associated with the application of the coercive measures. In 14 studies, a minority of patients had some positive experiences after the application of the measures, mainly regarding seclusion.22,26,27,30,34,37,39,43,44,46,48–50,54 The most frequent positive experiences reported were: 1) feeling that the measure was helpful, beneficial, or necessary29,35–37,44,49–51; 2) calming down, time for reflection or rest26,27,30,34,38,39,42,44; 3) safety or sense of control26,34,35,38,48,49,54; and 4) prevention of violence or a place to express emotion34,44

Subjective Experiences Comparing the Different Coercive Measures

Eight studies mentioned a comparison of the subjective experiences of the different coercive measures.19,21,30,32,34,36,38,54 Most of the studies identified forced medication as the preferred coercive measure for patients as compared with restraint,19,21 or seclusion,34 with patients finding it less traumatizing and distressing.32,36 The study by Naber et al.51 found a tendency toward patients viewing mechanical restraint as more unpleasant than injections but the result did not reach significance. A study, with a high-quality methodology, found in their follow-up that mechanical restraint was associated with a higher perception of coercion and other negative experiences as compared with seclusion.30 Another study with a high-quality methodology, however, indicated no significant difference in perceived coercion between seclusion and forced medication.38

Discussion

General Findings

This systematic review provides a detailed exploration of the factors that influence patient’s subjective experiences of restraint, seclusion, and/or the administration of forced medication in inpatient mental health services.

Among the main findings on the factors influencing the perception of measures are the attitudes of professionals and patient’s interactions with the staff. Thus, there is evidence to support the importance of staff behavior, especially their presence, during episodes of hostility and/or agitation and during the implementation of coercive measures,26,33,37,42,43,48,49,54 positioning them as agents of protection who are in control of the situation.36,41,42,48,49 Importantly, this result is related to modifiable factors, and reveals the need to have experts who are specialized in mental health care, with adequate training and specific organizational control to ensure good clinical practice in the wards. Indeed, staff training is covered in most programs to reduce coercive measures8 and it is part of the 6 core strategies.57 Likewise, respect and humane treatment by staff were repeatedly associated with a more favorable perception of coercive measures, a finding mainly reflected in qualitative studies,33,37,55,58 with a high empathy rating of staff related to a decrease in the use of coercive measures.59 Improved relationships between patients and staff seem to reduce conflict and restraint rates, as shown by the “safewards” model.16 Moreover, positive treatment by staff upon hospital admission was also associated with less coercive experience.60,61 The use of debriefing after the coercive measure appears to be supported by empirical evidence;20,22,26,36,42,48,55 although, its effectiveness in preventing trauma is inconsistently reported.31 However, debriefing plays an important role in providing psychological and operational feedback for both users and professionals, as well as for the organization as a whole. Another important issue that must be considered is the need to create a comfortable and appropriate climate in the ward, also taking into account individual patient characteristics and the possible negative consequences that these measures may on certain patients. Likewise, several studies have shown that the use of sensory modulation62 or comfort rooms can reduce the need for coercive measures.56,63 Thus, the evidence seems to indicate that creating a comfortable and appropriate atmosphere in the ward not only improves the subjective experience, but also prevents the adoption of these measures. With regard to the individual characteristics, there are fewer studies and more heterogeneous results. However, the results suggest that patients who are more vulnerable, with more adverse experiences and repeated coercive measures, present a greater risk of possible complications.

Some studies have demonstrated perceived benefit after seclusion43,44 and/or mechanical restraint,26,29 with positive perceptions including feelings of protection and security. Nevertheless, most studies reflect adverse and negative experiences, and these measures are associated with post-traumatic stress disorder19 and a high degree and wide variety of negative feelings and experiences, such as fear and humiliation.

Comparing among coercive measures, the results suggested a less aversive subjective experience associated with the administration of forced medication19,21,34 and more negative outcomes related to mechanical restraint30 and combined measures.32 Nevertheless, while some measures are more acceptable to patients than others, it is important to consider the preferences of patients and, if possible, discuss them on admission.

Limitations

There are a number of important limitations in this systematic review. The main limitation is related to the heterogeneity of the studies, with different designs, the use of both qualitative and quantitative (or both) methods, and, for most studies, small sample sizes. Also, the studies analyzed different coercive measures or combinations of measures. In general, studies about the experiences of coercive measures, as well as studies about the factors that affect them, are methodologically complex,64 and should be considered in the context in which they were carried out. Variations in results can be attributed to different service settings, mental health legislative frameworks, social policies, and cultural factors, and this requires that the results be interpreted with caution. Second, given the object of such studies and their important ethical and legal connotations, a publication bias is possible; i.e., there could be instances where negative results were obtained and not published. Third, study selection bias is possible; although, 2 independent reviewers performed the selection of the sources used in this study. Finally, the factors that affected the subjective experience were not considered as primary outcomes in most of the studies.

Future Research

Few studies used valid, simple, and reliable assessment instruments to study the subjective experience of coercive measures and the factors that influence these experiences. As pointed out by others,65,66 there are currently few instruments that can measure the subjective experiences of patients and may be applicable to compare the different coercive measures and different interventions. In this review, there were only 3 longitudinal studies19,30 and one interventional study31 with standardized outcome measures. Thus, more longitudinal and interventional studies are necessary to understand what factors positively and negatively affect patient experiences. Although many intervention studies have been carried out to reduce the use of these measures’ and to improve the handling of conflict and incidents in wards, these studies do not address the experiences of patients and the possible improvements in such experiences. Thus, subjective experience tracking and an evaluation of the long-term psychological effects are still lacking in this domain. Furthermore, there are few studies concerning the individual factors associated with the subjective experience of coercive measures, such as those related to previous exposure to traumatic or violent events, which may evoke stressful emotions and feelings among patients. These factors could be identified to prevent possible adverse effects of these measures.

Conclusions

It can be inferred from the results of this review that the actions of staff, the respect and treatment afforded to the patient, the effects of the physical and the organizational characteristics of the unit, and the inclusion of debriefing all influence the experience of coercive measures, and therefore efforts should be made to implement these changes in wards. In addition to reducing coercive measures, it could also be possible to improve the subjective experience of users in cases when the adoption of the measure is inevitable.

Footnotes

Author Note: Joint first co-authorship: Carlos Aguilera-Serrano and Jose Guzman-Parra

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Carlos Aguilera-Serrano, RN http://orcid.org/0000-0002-7520-162X

Jose Guzman-Parra, DClinPsy, PhD http://orcid.org/0000-0002-1463-6435

References

- 1. Zacher JL, Roche-Desilets J. Hypotension secondary to the combination of intramuscular olanzapine and intramuscular lorazepam. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66(12):1614–1615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Berardis D, Fornaro M, Orsolini L, et al. The role of inhaled loxapine in the treatment of acute agitation in patients with psychiatric disorders: a clinical review. Int J Mol Sci. 2017;18(2):349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Guzman-Parra J, Guzik J, Garcia-Sanchez JA, et al. Characteristics of psychiatric hospitalizations with multiple mechanical restraint episodes versus hospitalization with a single mechanical restraint episode. Psychiatry Res. 2016;30(244):210–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Roberts D, Crompton D, Milligan E, et al. Reflection on the use of seclusion. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2009;47(10):25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rakhmatullina M, Taub A, Jacob T. Morbidity and mortality associated with the utilization of restraints: A review of literature. Psychiatr Q. 2013;84(4):499–512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Guzman-Parra J, Garcia-Sanchez JA, Pino-Benitez I, et al. Effects of a regulatory protocol for mechanical restraint and coercion in a Spanish psychiatric ward. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2015;51(4):260–267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Guzman-Parra J, Aguilera Serrano C, García-Sánchez JA, et al. Effectiveness of a multimodal intervention program for restraint prevention in an acute Spanish psychiatric ward. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2016;22(3):233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stewart D, Van der Merwe M, Bowers L, et al. A review of interventions to reduce mechanical restraint and seclusion among adult psychiatric inpatients. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2010;31(6):413–424. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Guzman-Parra J, Aguilera Serrano C, García-Sánchez JA, et al. Effectiveness of a multimodal intervention program for restraint prevention in an acute Spanish psychiatric ward. J Am Psychiatr Nurses Assoc. 2016;22(3):233–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lebel JL, Duxbury JA, Putkonen A. Multinational experience in reducing restraint. J Psychosoc Nurs. 2014;52(11):22–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Putkonen A, Kuivalainen S, Louheranta O, et al. Cluster-randomized controlled trial of reducing seclusion and restraint in secured care of men with schizophrenia. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64(9):850–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Glover RW. Reducing the use of seclusion and restraint: a NASMHPD priority. Psychiatr Serv. 2005;56(9):1141–1142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wisdom JP, Wenger D, Robertson D, et al. The New York state office of mental health positive alternatives to restraint and seclusion (PARS) project. Psychiatr Serv. 2015;66(8):851–856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Wieman DA, Camacho-Gonsalves T, et al. Multisite study of an evidence-based practice to reduce seclusion and restraint in psychiatric inpatient facilities. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(3):345–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bowers L. Safewards: a new model of conflict and containment on psychiatric wards. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2014;21(6):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Bowers L, James K, Quirk A, et al. Reducing conflict and containment rates on acute psychiatric wards: The Safewards cluster randomised controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2015;52(9):1412–1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. World Health Organization. User empowerment in mental health – a statement by the WHO Regional Office for Europe. Copenhagen (DK): World Health Organization; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 18. World Health Organization. Policies and practices for mental health in Europe. Copenhagen (DK): World Health Organization; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fugger G, Gleiss A, Baldinger P, et al. Psychiatric patients’ perception of physical restraint. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2016;133(3):221–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Ling S, Cleverley K, Perivolaris A. Understanding mental health service user experiences of restraint through debriefing: a qualitative analysis. Can J Psychiatry. 2015;60(9):386–392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Mielau J, Altunbay J, Gallinat J, et al. Subjective experience of coercion in psychiatric care: a study comparing the attitudes of patients and healthy volunteers towards coercive methods and their justification. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2015;266(4):337–347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Holmes D, Murray SJ, Knack N. Experiencing seclusion in a forensic psychiatric setting: a phenomenological study. J Forensic Nurs. 2015;11(4):200–213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Van Der Merwe M, Muir-Cochrane E, Jones J, et al. Improving seclusion practice: implications of a review of staff and patient views. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2013;20(3):203–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, et al. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement (Reprinted from Annals of Internal Medicine). Phys Ther. 2009;89(9):873–880. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. CASP Checklist. 2016. Available from: http://www.casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists.

- 26. Lanthén K, Rask M, Sunnqvist C. Psychiatric patients experiences with mechanical restraints: an interview study. Psychiatry J. 2015;748392. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Ezeobele IE, Malecha AT, Mock A, et al. Patients’ lived seclusion experience in acute psychiatric hospital in the United States: a qualitative study. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2014;21(4):303–312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Faschingbauer KM, Peden-McAlpine C, Tempel W. Use of seclusion. Finding the voice of the patient to influence practice. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2013;51(7):32–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Larue C, Dumais A, Boyer R, et al. The experience of seclusion and restraint in psychiatric settings: perspectives of patients. Iss Ment Heal Nurs. 2013;34(5):317–324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Steinert T, Birk M, Flammer E, et al. Subjective distress after seclusion or mechanical restraint: one-year follow-up of a randomized controlled study. Psychiatr Serv. 2013;64:1012–1017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Whitecross F, Seeary A, Lee S. Measuring the impacts of seclusion on psychiatry inpatients and the effectiveness of a pilot single-session post-seclusion counselling intervention. Int J Ment Health Nurs. 2013;22(6):512–521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Georgieva I, Mulder CL, Whittington R. Evaluation of behavioral changes and subjective distress after exposure to coercive inpatient interventions. BMC Psychiatry. 2012;12(1):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kontio R, Joffe G, Putkonen H, et al. Seclusion and restraint in psychiatry: patients’ experiences and practical suggestions on how to improve practices and use alternatives. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2012;48(1):16–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Haw C, Stubbs J, Bickle A, et al. Coercive treatments in forensic psychiatry: a study of patients’ experiences and preferences. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2011;22(4):564–585. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Iversen VC, Sallaup T, Vaaler AE, et al. Patients’ perceptions of their stay in a psychiatric seclusion area. J Psychiatr Intensive Care. 2011;7(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mayers P, Keet N, Winkler G, et al. Mental health service users’ perceptions and experiences of sedation, seclusion and restraint. Int J Soc Psychiatry. 2010;56(1):60–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Keski-Valkama A, Koivisto A-M, Eronen M, et al. Forensic and general psychiatric patients’ view of seclusion: a comparison study. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2010;21(3):446–461. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Veltkamp E, Nijman H, Stolker JJ, et al. Patients’ preferences for seclusion or forced medication in acute psychiatric emergency in the Netherlands. Psychiatr Serv. 2008;59(2):209–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Ntsaba GM, Havenga Y. Psychiatric in-patients’ experience of being secluded in a specific hospital in Lesotho. Heal SA Gesondheid. 2008;12(4):3–12. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Stolker JJ, Nijman HLI, Zwanikken PH. Are patients’ views on seclusion associated with lack of privacy in the ward? Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 2006;20(6):282–287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chien W-T, Chan CWH, Lam L-W, et al. Psychiatric inpatients’ perceptions of positive and negative aspects of physical restraint. Patient Educ Couns. 2005;59(1):80–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wynn R. Psychiatric inpatients’ experiences with restraint. J Forens Psychiatry Psychol. 2004;15(1):124–144. [Google Scholar]

- 43. Holmes D, Kennedy SL, Perron A. The mentally ill and social exclusion: a critical examination of the use of seclusion from the patient’s perspective. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2004;25(6):559–578. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Meehan T, Bergen H, Fjeldsoe K. Staff and patient perceptions of seclusion: has anything changed? J Adv Nurs. 2004;47(1):33–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Hoekstra T, Lendemeijer HH, Jansen MG. Seclusion: the inside story. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2004;11(3):276–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Haglund K, Von Knorring L, Von Essen L. Forced medication in psychiatric care: patient experiences and nurse perceptions. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2003;10(1):65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bonner G, Lowe T, Rawcliffe D, et al. Trauma for all: a pilot study of the subjective experience of physical restraint for mental health inpatients and staff in the UK. J Psychiatr Ment Health Nurs. 2002;9(4):465–473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Meehan T, Vermeer C, Windsor C. Patients’ perceptions of seclusion: a qualitative investigation. J Adv Nurs. 2000;31(2):370–377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Martinez R, Grimm M, Adamson M. From the other side of the door: patient views of seclusion. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Heal Serv. 1999;37(3):13–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Ray NK, Mayer KJ, Rappaport ME. Patient perspectives on restraint and seclusion experiences: a survey of former patients of New York State Psychiatric Facilities. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 1996;20(1):11–18. [Google Scholar]

- 51. Naber D, Kircher T, Hessel K. Schizophrenic patients’ retrospective attitudes regarding involuntary psychopharmacological treatment and restraint. Eur Psychiatry. 1996;11(1):7–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Hopkins Outlaw F, Lowery BJ. An attributional study of seclusion and restraint of psychiatric patients. Arch Psychiatr Nurs. 1994;8(2):69–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Mann LS, Wise TN, Shay L. A prospective study of psychiatry patients’ attitudes toward the seclusion room experience. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 1993;15(3):177–182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tooke SK, Brown JS. Perceptions of seclusion: comparing patient and staff reactions. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1992;30(8):23–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Norris MK, Kennedy CW. The view from within: how patients perceive the seclusion process. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 1992;30(3):7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. van der Schaaf PS, Dusseldorp E, Keuning FM, et al. Impact of the physical environment of psychiatric wards on the use of seclusion. Br J Psychiatry. 2013;202(2):142–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. LeBel JL, Duxbury JA, Putkonen A, et al. Multinational experiences in reducing and preventing the use of restraint and seclusion. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2014;52(11):22–29. doi:10.3928/02793695-20140915-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Newton-Howes G, Mullen R. Coercion in psychiatric care: systematic review of correlates and themes. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62(5):465–470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Yang CP, Hargreaves WA, Bostrom A. Association of empathy of nursing staff with reduction of seclusion and restraint in psychiatric inpatient care. Psychiatr Serv. 2014;65(2):251–254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Lidz CW, Mulvey EP, Hoge SK, et al. Factual sources of psychiatric patients’ perceptions of coercion in the hospital admission process. Am J Psychiatry. 1998;155(9):1254–1260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Lidz CW, Mulvey EP, Hoge SK, et al. Sources of coercive behaviours in psychiatric admissions. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2000;101(1):73–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Andersen C, Kolmos A, Andersen K, et al. Applying sensory modulation to mental health inpatient care to reduce seclusion and restraint: a case control study. Nord J Psychiatry. 2017;71(7):525–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Cummings KS, Grandfield SA, Coldwell CM. Caring with comfort rooms. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2010;48(6):26–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Soininen P, Putkonen H, Joffe G, et al. Methodological and ethical challenges in studying patients’ perceptions of coercion: a systematic mixed studies review. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14(1):162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Bergk J, Flammer E, Steinert T. Coercion Experience Scale (CES)—validation of a questionnaire on coercive measures. BMC Psychiatry. 2010;10:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Nyttingnes O, Rugkåsa J, Holmén A, et al. The development, validation, and feasibility of the experienced coercion scale. Psychol Assess [epub ahead of print 5 Dec 2016]. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]