Abstract

With the synthesis and functionalization of membranes for selective separations, reactivity, and stimuli responsive behavior arises new and advanced opportunities. The integration of bio-based channels is one of these advancements in membrane technologies. By a layer-by-layer (LbL) assembly of polyelectrolytes, outer membrane protein F trimers (OmpF) or “porins” from Escherichia coli with a central pore of ~2 nm diameter at its opening and ~0.7 × 1.1 nm at its constricted region are immobilized within the pores of poly(vinylidene fluoride) microfiltration membranes, as opposed to traditional ruptured lipid bilayer or vesicles processes. These OmpF-membranes demonstrate selective rejections of non-charged organics over ionic solutes, allowing the passage of salts up to 2 times higher than traditional nanofiltration membranes starting with rejections of 84% for 0.4–1.0 kDa organics. The presence of charged groups in OmpF membranes also leads to pH-dependent salt rejection through Donnan exclusion. These OmpF-membranes also show exceptional durability and stability, delivering consistent and constant permeability and recovery for over 160 h of operation. Characterization of solutions containing OmpF, and membranes were conducted during each stage of the process, including detection by fluorescence labelling (FITC), zeta potential, pH responsiveness, flux changes, and rejections of organic-inorganic solutions.

Keywords: Layer-by-layer membranes, selective separation, OmpF immobilization, functional polymer

1. INTRODUCTION

Nature offers elegant separations with high selectivity, resistance to fouling, and regenerative capabilities. Inspired by these separation processes, research progress has been extensive in recent years, largely by the development of new processes of isolation of biomolecules that render unique functionalities and by their incorporation in engineered materials.1–3 Likewise, recent approaches in the synthesis of bioinspired structures, such as amphiphilic block copolymers, imidazole-quartet channels, triarylamines, carbon nanotubes or graphene oxide, have improved the separation performance and versatility.4–8 Processes involving polymer and bioinspired membranes have been developed in order to obtain applications such as water purification and ion transport, recovery of valuable products, sensors developments and drug delivery, etc.9–13 Membranes provide selective barriers that allow certain molecules to pass through them based on charge and/or size restriction and provide an opportunity for chemical separation that requires less energy than more common thermal separation processes.9, 14

Membranes may also act as a platform to immobilize other useful materials in pores. Functionalizing membranes that can be responsive to various stimuli like temperature, pH, and electric fields, promises even more unique applications.15, 16 For porous membranes, a typical functionalization involves grafting or cross-linking of stimuli-responsive functional polymers inside the membrane pores. Such responsiveness allows reversible changes in selectivity and permeation across the membrane in response to environmental factors, such as pH, which can deprotonate functional polymers, absorbing water while decreasing membrane’s pore diameter and permeability.17–20 The functional groups in the polymer allow for the assembly of other layers with alternating charge polyelectrolyte groups in layer-by-layer (LbL) assembly.16, 21–24 Additionally, one can take advantage of the LbL responsive functionality by tethering diverse biofunctional groups, such as enzymes, peptides and in our case, porins.2, 22, 23

Porins are transmembrane passive pores conformed by cylindrical β-barrel proteins with a pore going through the middle of their structure.4 Some porins are monomers, while others, including the Outer membrane protein F (OmpF) from Gram-negative Escherichia coli, form trimers. Therefore, incorporating porins into these synthetic LbL assembled membranes could potentially increase rejection and selectivity due to a combination of electrostatic responsiveness and steric effects, while attaining larger water permeability over conventional and charged ultrafiltration (UF) membranes.25, 26

The incorporation of OmpF porins into membranes poses additional advantages for several reasons. OmpF has been shown to have a slight selectivity for cations over anions, although it functions principally as a non-specific port and, studies of cations and anions flowing through OmpF showed these ions follow different pathways without interference through the pore.27–33 However, OmpF have shown enhanced transport of organic molecules, if these molecules are charged.33–35 This characteristic has mostly been used to increase drug permeability through the cell membrane, but it could be applied in a highly specific purification of valuable molecules, by adding a charge to them and selectively separate them by using porins. Gross physiochemical properties like size and charge of the solute rather than specific molecular shape and atomic composition dictate how OmpF rejects.32 With an hourglass shape with ~2 nm diameter at its opening and ~0.7 × 1.1 nm at its most constricted region (eyelet), the monomeric pores of OmpF should easily reject charge-neutral molecules around this same size (around 650 Da), which include sucrose at a hydrated diameter of approximately 1.0 nm.33, 36, 37 Furthermore, both in vivo and in vitro studies have revealed OmpF’s pH responsive behavior, suggesting changes in pore size at a pKa of 7.2.38–42 OmpF’s inherent stimuli-responsiveness, including sensitiveness to magnetic fields, could be useful for channel alignment and can be tactful in simultaneous biofilm cleaning and separation of multiple sizes of molecules.43 Permeability through the central channel in porins depends on the size and charge of a molecule. For example, small metabolites can be transported through porins but large polysaccharides cannot. To use porins in the construction of artificial membranes, the protein would need to be incorporated protected from denaturation. The LbL-assembly is potentially a good method for the incorporation of proteins without covalent attachment. This technique has shown a 25-fold increase of immobilized biomolecules with insignificant distortion of the biomolecule.22

Studies thus far on OmpF porins have been conducted with either the entire E. coli cell in vivo, with OmpF isolated and immobilized within a block-copolymer, with OmpF self-assembled into lipid vesicles deposited on porous supports or ruptured into planar layers.11, 24, 44, 45 Vesicles and ruptured vesicle planes have proven to be quite defective and unstable under the high pressures. Membranes with vesicles containing aquaporins have poorly rejected inorganic salts, with only one research group that has achieved 98% rejection.45 Poor rejection is likely attributed to defects in the bilayers because the vesicles are not cross-linked together and the aquaporins may not be aligned. Even with perfect block-copolymer or lipid bilayer, protein stability is still a major concern.9 Immobilizing biomolecules within already-existing membrane pores and then crosslinking the charged residues of these molecules could increase mechanical stability and longevity.

The present study quantifies immobilization of OmpF porins using LbL assembly functionalization within the pores of poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) membranes. Specific objectives include: (1) to determine whether or not LbL immobilization of OmpF enhances salt passage while rejecting solutes such as sucrose (1 nm size) and (2), to evaluate the stability of the OmpF functionalized membranes through the rejection of various solutions containing different organic solutes and salts. The membranes were analyzed during each stage of the process, including comparisons between LbL membranes with and without OmpF. Characterizations include Zeta (ζ) potential, pH responsiveness, fluorescence and changes in permeability. The characterizations of OmpF purified solutions for immobilization include feed and permeate concentrations, and ζ potential. The effects of pH on permeability and salt rejection were also studied. This is the new approach with native protein incorporated into artificial polymer membrane, which could be leading to a more active and functional separation method.

2. EXPERIMENTAL

2.1. Materials for OmpF Extraction and Characterization

E.coli BL21(DE3) (NEB, USA); Valeric Acid (99%); Coomassie blue R-250, Ammonium persulfate (APS) (Sigma-Aldrich, USA); sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS), polyacrylamide, Tris-HCl, N,N,N′,N′-Tetramethylethylenediamine (TEMED), HEPES, Dimethylformamide (DMF), (Bioworld, USA); ethanol (95%), acetic acid (glacial) (VWR, USA); protein marker, bicinchoninic acid (BCA) assay PierceTM BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermofisher Scientific, USA); Fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC) (Thermofisher Scientific, USA).

2.2. Materials for Synthesis of LbL Membrane with OmpF

Acrylic acid (AA), 98% extra pure and stabilized, N,N′-Methylenebisacrylamide (MBA), for electrophoresis, 99+% (ACROS ORGANICS, France and Belgium, respectively); potassium persulfate (KPS) (EM SCIENCE, Germany); poly(allylamine hydrochloride) (PAH) (ALDRICH, Japan); poly(styrene sulfonic acid) (PSS), MW 75,000, 30% w/v aq. sol. (Alfa Aesar, USA); purified OmpF from E. coli; commercial scale membranes of poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF) (PV200, PV700 and XPVDF, produced in collaboration with Nanostone Water, Inc., USA); Track-etched 50 nm polycarbonate membranes (PC50) (Whatman-Tisch Scientific, USA).

2.3. OmpF Solution Purification and Characterization

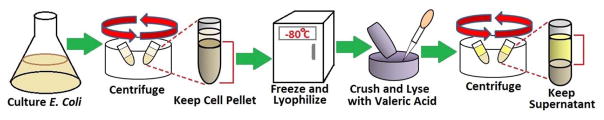

Normally, membrane protein purification consists of several steps: culturing cells, cell lysis, membrane protein extraction, and purification through chromatography.46–48 Studies have shown that porin trimers are stable in detergents and organic solvents due to hydrogen-bonding and electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions between each subunit.49 Thus, a method to rapidly extract membrane protein was developed to largely improve the efficiency of the purification process for OmpF. Other methods of OmpF solution characterization are depicted in the Electronic Supplementary Information (ESI) section 1. The procedure used was a modification from Arcidiacono et al.50 This method that uses a single step extraction, save not only time and effort but also provide active protein, as depicted in Figure 1. E.coli BL21 (DE3) were cultured in LB medium overnight. Harvested cells were centrifuged at 8,000 rpm for 10 min, then frozen at −80 °C and lyophilized (Labconco Freezone 12). The lyophilized cells were ground to powder and 2 mL of valeric acid were added per gram of powder, followed by the 3-fold addition of deionized water to get a concentration of 2.3 M valeric acid. The mixture was stirred at room temperature for 1 hour. Finally, the mixture was clarified by centrifugation at 20,000 g for 30 min. This valeric acid solution acts as the dispersant detergent having its alkyl group to protect the protein from denaturation and aggregation. Through this method, the product contains highly pure OmpF.50 Previous studies have used this method to purify OmpF and OmpC, having functional proteins that were used in a lipid bilayer membrane and as antigen for the immune system, respectively.51, 52

Figure 1.

Schematic of the extraction process of OmpF from E. coli.

The purity of OmpF isolated by valeric acid was examined through sodium dodecyl sulfate polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE). The sample was diluted with 2% SDS five times and then boiled in a water bath for 5 min before loading into a 20% polyacrylamide gel (20% polyacrylamide, 0.4M Tris-HCl pH 8.8, 0.1% SDS, 0.1% ammonium persulfate, and 0.1% TEMED). The sample was run in the SDS buffer (0.3% w/v Tris base, 1.44% w/v glycine, and 0.1% w/v SDS) at 200 V for one hour. Protein was stained with 0.1% Coomassie blue R-250 in 50% ethanol and 10% acetic acid for 15 min, and distained with 10% acetic acid and 20% ethanol for one hour. An enhanced BCA assay was chosen to quantify the OmpF concentration for each of the samples due to its non-destructive approach. This enhanced protocol has a working range between 5 and 250 μg/mL. Feed, permeate, and retentate was quantified through material balance in each of the membranes with the enhanced BCA method.

For the fluorescence labeling, valeric acid containing purified OmpF was diluted with two folds of HEPES buffer (50 mM HEPES, 0.2M NaCl, pH = 7.5), then adjusted the pH of the solution to ~8.0. FITC was dissolved in DMF and then added into the mixture to a final concentration of 0.1mg/mL. The mixture was incubated in dark at room temperature for 2 hours. After the labeling reaction, 100 mM Tris (pH = 8.0) was added to the mixture and incubated for 20 min to quench the free FITC. OmpF was labeled with extra amount of FITC. Free FITC was removed by centrifugation leaving labeled protein and pass through small molecules. To determine the labeling efficiency, which has the molecular weight cut-off of 10 kDa, the difference is calculated between the FITC concentration before and after filtration and the concentration of OmpF. The ratio of OmpF: FITC is 1:3, which is one trimer with 3 FITC labeling efficiency.

2.4. Membrane Characterization and Layer-by-layer Functionalization

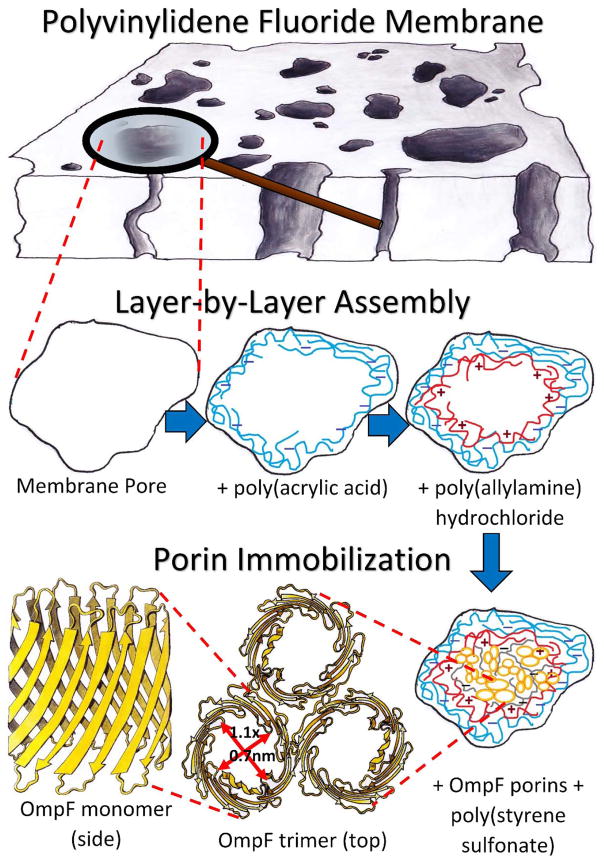

Samples of PVDF and PC50 membranes were characterized with a scanning electron microscope (SEM) (Hitachi S-4300). Pore sizes were measured based on previous works using ImageJ, and SAS software for statistical analysis.53 OmpF were then immobilized within the PVDF membranes after two assembled layers. First, a layer of PAA hydrogel was synthesized in situ by free radical polymerization of PAA hydrogel by previously developed methods.53–55 Second, a solution of PAH was accumulated by convective flow using a dead-end batch cell (Sterlitech HP4750). The PAH solution was prepared with 0.2 M NaCl solution and two-fold molar excess of PAH with respect to the immobilized PAA. The pH of the PAH solution was adjusted to ~9.0 using NaOH to deprotonate the PAA in order to bond the amine groups of PAH to the COO− groups and form a long poly-alkyl double chain that would protect the hydrophobic center of the OmpF barrels.

A top layer of PSS was permeated through the membrane after the OmpF immobilization and was used to stabilize the protein in the membrane, crosslinking OmpF extracellular loops and bonding these to the charge leftovers of the PAH layer. PSS was also permeated through a non-OmpF membrane, on top of the PAH layer for comparison. 25 mL of deionized ultra-filtered water (DIUF) containing PSS repeating units equal to the quantity of COOH groups on the membrane were prepared. The solution was passed twice, at 10.2 bar and pH = 6.0. A slightly acidic pH renders OmpF’s extracellular loops positively charged which has an affinity for the carboxylic groups in PSS. Figure 2 represents the entire LbL assembly to OmpF immobilization process. Functionalized membranes were also characterized with SEM and in the case of fluorescence-labeled OmpF membranes, a confocal microscope was employed (Zeiss LSM880 Multiphotom Microscope). Detailed descriptions of the functionalization methods used are in the ESI section 2.

Figure 2.

Schematic of layer-by-layer assembly process of polyelectrolytes into a PVDF membrane and subsequent immobilization of OmpF.

2.5. Immobilization of OmpF in the LbL assembled membrane

The OmpF solution was sonicated to reduce association, and permeated twice through the PVDF-PAA-PAH membrane at 6.8 bar for 5 hours and at 9.5 bar for 5.5 hours. The original frozen OmpF solution (2.3 M valeric acid) containing 51 μg/mL of protein was thawed to room temperature and filtered through a cellulose membrane syringe filter with average pore diameter of 200 nm to remove any remaining cell debris. Before diluting it with water, 5 mL of additional valeric acid were added to the purified OmpF solution to prevent excessive association. For a total volume of 100 mL, 93 mL of DIUF water were added. The pH was raised to 5.5 with the addition of NaOH to improve miscibility of valeric acid in water and detergency, observed through increased clarity of the solution. BCA assay and fluorescence measurements (Varian Cary Eclipse Fluorescence Spectrophotometer) were carried out for material balance purposes.

2.6. Flux Rejection and Selectivity Studies

Permeation of different solutions was done in the dead-end batch cell at 3.4 bar with DIUF at pH = 7.0 to surpass the pKa of functional polymers. Values of ζ potential (Anton-Paar Surpass Electrokinetic Analyzer) were used to quantify changes on surface charge, see ESI section 3 for more detail. Depending on the functional groups present on the membrane surface, the ζ potential would significantly vary, rendering it as a method to verify proper functionalization of each layer. Another verification technique for layers was changing the pH of water from 8 to 3 for both PVDF-PAA and PVDF-PAA-PAH. The different pH solutions were allowed to pass until the flux reached a steady state. Between each pass, the membrane was washed with DIUF water for 30 min; ensuring ions were removed before the next pass at a different pH. Each pH sample was fluxed three times (cycles) to ensure stability of the layers.

The membrane throughout functionalization was tested for its rejection of salts and uncharged (organic) molecules, as well as for pure water through each layer. Testing rejections of uncharged molecules gives an indication of the rejection capabilities based solely on size and thus indicates the size of pores. At 3.4 bar, mixture solutions containing one uncharged molecule (glucose, sucrose, or polyethylene glycols) (PEG 400 and PEG 1000)) and one salt (NaCl or CaCl2) were passed through the membrane after each layer of assembly to demonstrate selectivity. Passes were conducted at pH = 6.0 in DIUF water to avoid effects of additional ions. Membranes containing OmpF should significantly reject molecules around the size of sucrose and larger while allowing the permeation of small ions. The aforementioned solutes plus Dextran Blue 5000 and Dextran 41000 mixture solutions were used in rejection cycles with the OmpF membrane, see Table 1. Here, one cycle consisted of passing all six model organic solutes, with DIUF permeation through the membrane between each cycle. Three cycles were performed to prove consistent results between rejection and stability. The solutions were permeated through the membrane for an average of 8 h/day in three weeks. Due to previous reported functionality of OmpF at varying pH, rejection and flux were also measured at pH between 3.0 and 10.0 and compared to the non-OmpF membrane pH functionality.

Table 1.

Molecular weight, hydrodynamic and ionic radii of ions and model organic molecules used in rejection studies.

| Molecule | Molecular Weight (Da) | rH(nm) | Ionic Radii (nm) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na+ | 23.0 | 0.36* | 0.095 | 58, 59 |

| Ca2+ | 40.1 | 0.41* | 0.099 | |

|

| ||||

| Cl− | 35.5 | 0.33* | 0.181 | 59 |

|

| ||||

| Glucose† | 180.2 | 0.37 | - | 60–65 |

|

| ||||

| Sucrose† | 342.3 | 0.46 | - | 60–63, 65, 66 |

|

| ||||

| PEG 400‡ | 400 | 0.65 | - | 60, 67, 68 |

| PEG 1000‡ | 1000 | 0.93 | - | |

|

| ||||

| Dextran Blue 5000‡ | 5000 | 1.87 | - | 66, 69–71 |

| Dextran 41000‡ | 41000 | 4.60 | - | |

Mean of rH referenced values.

Calculated rH by curve fitting of referenced values.

Hydrated radii.

A total organic carbon analyzer (TOC) (TOC-5000A by Shimadzu) was used to measure feed, permeate, and retentate concentrations of the model organic solutions used, see ESI section 4 for details. Salt rejection measurements were taken with a conductivity probe (Fisher Scientific Traceable Bench Conductivity Meter) and an inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometer (ICP-OES) (Varian Vista-PRO).

As a method of control, track-etched polycarbonate membranes (PC50) were used to investigate the necessity of LbL assembly for OmpF immobilization and see if OmpF dissociate under shear stress. PC50 provides pores of consistent size (75 ± 1 nm) and has effectively no surface charge to cause OmpF grafting. The OmpF solution used has pH = 5.5 and is 0.0352 M of valeric acid. This OmpF solution was permeated through PC50 at 3.4 bar, and samples of feed, permeate, and retentate were collected to calculate the OmpF loading.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Characterization of OmpF

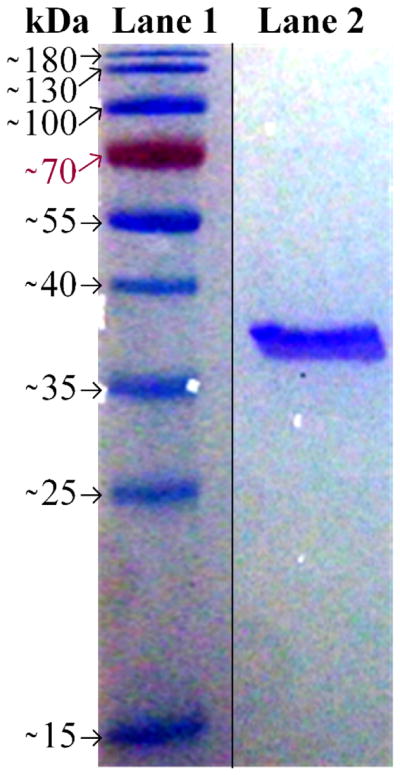

Purified OmpF was analyzed using SDS-PAGE (Figure 3). Lane 1 is the protein marker and Lane 2 is the purified OmpF. The single band between 35 and 40 kDa is OmpF monomer, which has a molecular weight of 38.9 kDa. The diluted solution (0.035 M at pH = 5.5) of valeric acid was used to gradually pass extracted OmpF through the functionalized membranes. The pH = 5.5 was chosen because valeric acid is miscible in water at this pH, and the slightly acidic pH achieves the desired charge of residues on the OmpF extracellular loops.

Figure 3.

SDS-PAGE of OmpF extracted using valeric acid. Lane 1 is the protein marker, and lane 2 is the purified OmpF obtained.

3.2. Membrane Characterization

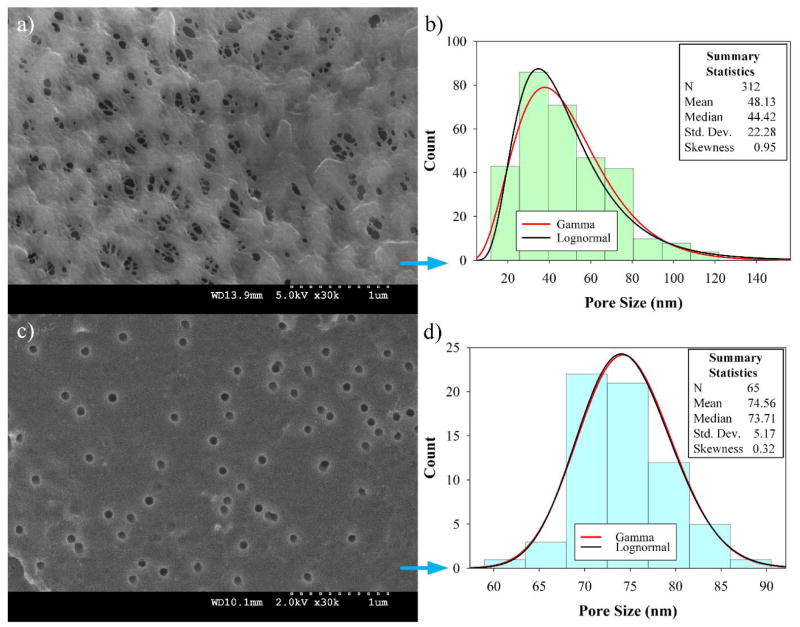

Preliminary studies for selecting the suitable PVDF membrane were performed and are discussed in the ESI section 5. The selected PVDF membrane in Figure 4a (PV200 from Table S1), shows an SEM image with a fairly porous, intricate surface of different pore shapes and sizes with an upper limit of 140 nm (Figure 4b). The alternative PV700 membrane tested shows larger pores, see ESI section 5, Figure S1. On the other hand, PC50 has more uniform pores, as expected. Histograms of the size distributions for both PVDF and PC50 (Figure 4b, d) reveal an average pore diameter of 48 ± 1 nm and 75 ± 1 nm, respectively. For PVDF, pore size distribution was well fitted with both lognormal and gamma distributions, with the latter being more adjusted. With α = 0.05, the Kolmogorov-Smirnov parameter was D = 0.046, with a probability P = 0.051 for lognormal and D = 0.038, P > 0.25 for gamma functions. PVDF provides pores that are large enough for polyelectrolyte LbL-assembled layers and the subsequent addition of OmpF without complete collapse. For PC50, the median pore diameter is 74 nm, closer to its mean value than PVDF. Skewness is low for gamma and lognormal distribution models and the standard deviation is small, suggesting highly consistent pores and more normal goodness-of-fit distribution parameters with α = 0.05 (D = 0.085, P = 0.170 for lognormal and D = 0.082, P = 0.209 for gamma).

Figure 4.

Bare membrane characterization. (a) Top surface PVDF microfiltration membrane (Nanostone PV200); (b) Pore size distribution of PVDF membrane; (c) Top surface PC membrane (50 nm Whatman-Tisch Scientific); (d) Pore size distribution of PC membrane.

3.2.1. Verification of Polymer Layers, Immobilized Porins, and Functionality

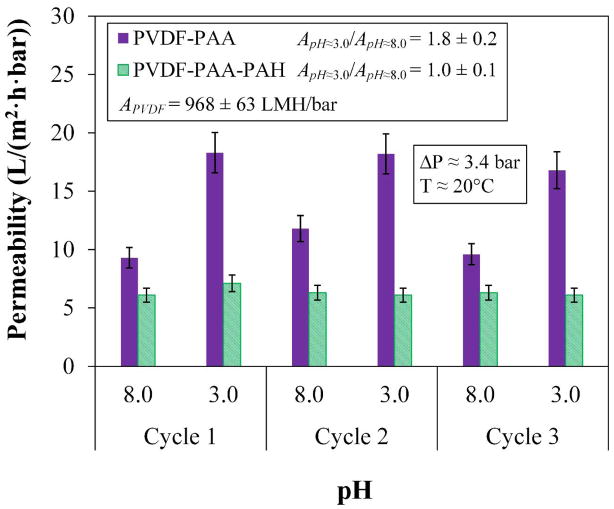

Besides observing a mass gain, a characteristic pH responsiveness was observed for the PAA layer, represented in Figure 5. The selection of the optimal functionalization conditions for the PAA layer are discussed in the ESI section 6. Three cycles demonstrate the pH responsiveness of PAA whereby COOH groups become deprotonated into COO− at higher pH, bonding with water molecules on their positive end and thus increasing swelling. Flux decreases at a higher pH, the extent to which is dependent on several factors like the quantity of PAA, initial pore size, and degree of cross-linking. Consistent changes in permeability depending on pH also demonstrate the stability of this membrane. A particular ratio of DIUF permeability (A) at a pH =3 compared to pH = 8 is observed. For this particular PVDF-PAA membrane, ApH3/ApH8 fluctuates between 17.8 ± 0.4 and 10.2 ± 0.6 L/(m2·h·bar) (LMH/bar) for low and high pH’s, respectively. In Figure 5, it is also shown that with the addition of PAH, this pH responsiveness is not observable, implying that PAH bound with the first layer of PAA and form a long poly-alkyl double chain. This poly-alkyl chain protects the transmembrane domain of OmpF from aggregation and deformation by hydrophobic interactions. Although there could still be some hydrophilicity presented as swelling within the polymer layers due to loose charges, they renders any observable functionality null, due to a balance of charged groups. For this membrane, the permeability is in effect constant (6.3 ± 0.2 LMH/bar) at any pH.

Figure 5.

Water permeability and pH responsiveness in layer-by-layer functionalization after two layers. Membrane used: PVDF (Nanostone PV200), original pore size of 48 ± 1 nm. Monomer concentration before polymerization = 1.26 M acrylic acid. APVDF is the permeability of the bare PVDF membrane to DIUF.

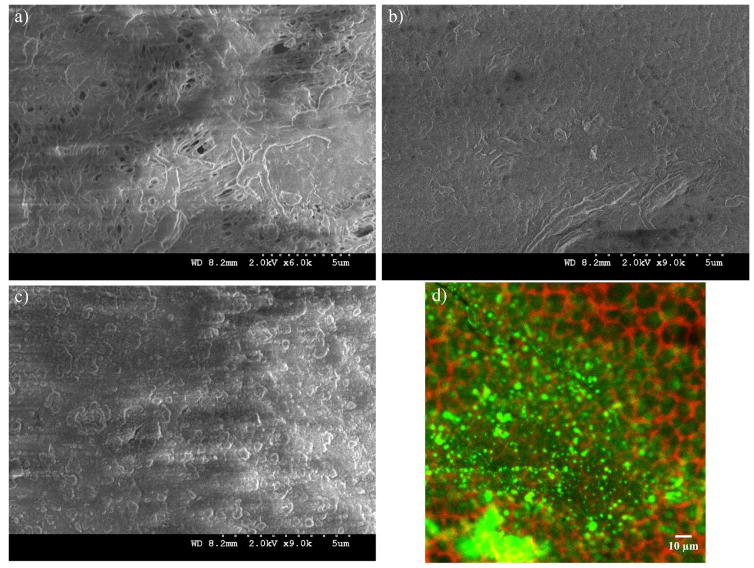

After each polymer layer, images of the membranes were taken with the SEM and the confocal microscope; this last was used with the fluorescence (FITC)-labeled OmpF membranes only. In Figure 6a, PAA layer decreased the porosity extensively, but some bigger pores can be seen. Non-OmpF membranes with all layers (PAA to PSS) show almost no porous structure and some polymer aggregates on the surface (Figure 6c), this differs from the OmpF membrane in Figure 6b. The OmpF membranes still show some open spaces (higher porosity) with less polymer agglomeration, evidencing a different layer arrange that can increase permeability on these membranes, as discussed below. The labeled OmpF membranes in Figure 6d show that OmpF are distributed uniformly on the porous structure of the membrane, both on the surface and in depth: confocal images show presence of fluorescence down to 20 μm.

Figure 6.

Membrane characterization in each step of layer-by-layer functionalization. (a) Top surface PVDF-PAA membrane; (b) Top surface PVDF-PAA-PAH-OmpF-PSS membrane; (c) Top surface PVDF-PAA-PAH-PSS membrane; (d) Top surface PVDF-PAA-PAH-FITC labelled OmpF-PSS membrane with green tag (FITC) for fluorescence-labeled OmpF and red tag for membrane structure. Membrane used: PVDF (Nanostone PV200), original pore size of 48 ± 1 nm. PAA weight gain ≈ 3.0%. PAH:PAA = 2/1 molar, PSS:PAA = 1/1 molar; OmpF permeated: 1.74 g/m2 of PVDF top surface.

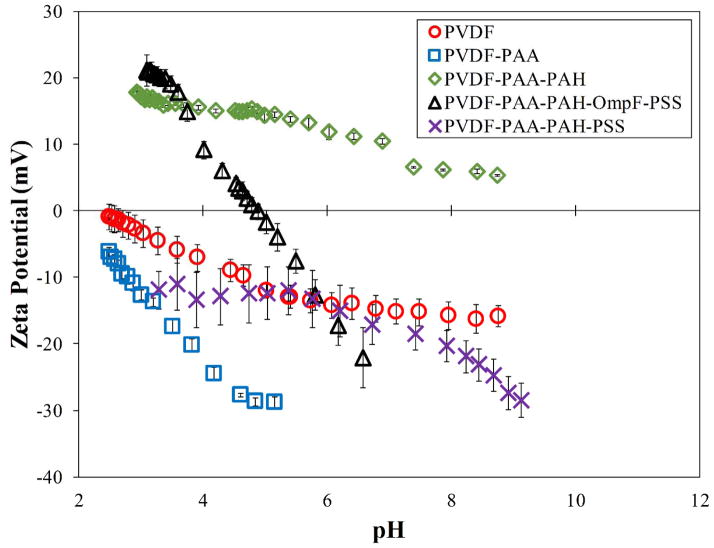

Measurements of surface charge verify the presence of each polymer layer. Each layer builds upon the next, with functional groups of the most recently added layer influencing the ζ potential. The functional groups show negative values when negatively charged ionization is present and positive for positively charged groups. Neutral surfaces change the charge from positive to negative throughout the range of pH. As seen in Figure 7, the bare PVDF membrane has slightly acidic behavior due to charging on its surface, the PAA functionalized membrane shows negative behavior and PAA-PAH is positive due to the amine groups in its structure. The final PVDF-PAA-OmpF-PSS membrane in this case goes from positive to negative. The hydrophilic amino acid on each end of OmpF was stabilized by the electrostatic interactions with the functional polymers. In addition, the presence of previous charges from PAA and PAH, shifts the OmpF ionization point to pH 5.0. In the case of the non-OmpF membrane (PVDF-PAA-PAH-PSS), its behavior is negative as expected from the sulfonate groups in PSS. There is a small range between pH 4 and 6 where the ζ potential of the non-OmpF membrane does not change, due to possible balance of the charges between the PAH and the PSS layers.

Figure 7.

Zeta potential due to pH change in each step of layer-by-layer functionalization. Membrane used: PVDF (Nanostone PV200), original pore size of 48 ± 1 nm. PAA weight gain ≈ 3.0%. PAH:PAA = 2/1 molar, PSS:PAA = 1/1 molar; OmpF permeated: 1.74 g/m2 of PVDF top surface. Some error bars are inside the symbols or are negligible.

3.2.2. Water Permeability changes during Functionalization

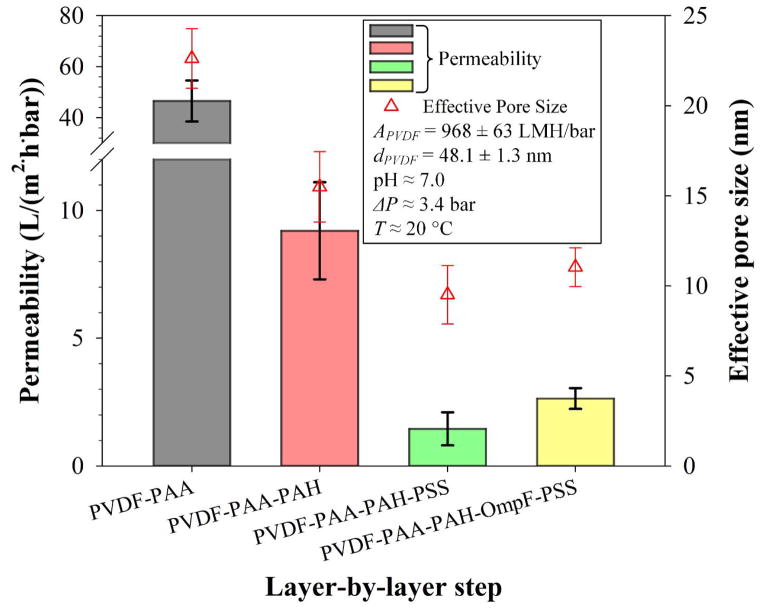

Additional layers within a channel reduce the diameter of the channel and thus, these layer decreased the permeability of water, unless hydrophilicity is increased. Measurements of permeability of DIUF at pH = 7.0 throughout functionalization are presented in Figure 8. Indeed, overall permeability decreases with each additional layer, from 968 ± 63 LMH/bar for the bare PVDF to a final 2.6 ± 0.3 LMH/bar for OmpF membranes. In addition, a greater pickup of PSS in the non-OmpF membrane is shown here. This difference likely occurred due to the fact no OmpF are present and thus more of the positive charges left from amine groups in PAH are available to bind to deprotonated carboxylic groups in PSS. Unlike OmpF, this polymer layer does not inherently contain pores, so increased grafting of PSS decreased flux.

Figure 8.

Permeability and pore size change of functionalized PVDF membrane (Nanostone PV200) per step of layer-by-layer functionalization. PAA weight gain ≈ 3.0%; PAH:PAA = 2/1 molar, PSS:PAA = 1/1 molar. APVDF is the permeability of the bare PVDF membrane to DIUF water. dPVDF is the mean pore size of the bare PVDF membrane to DIUF water.

On the other hand, increased grafting of properly aligned OmpF within the pore could actually increase flux because OmpF contains positive and negative residues on opposite sides within the tightest midsection, rendering this area polar and highly hydrophilic at neutral pH.56 Thus, non-OmpF membranes have, on average, a slightly smaller permeability (1.5 ± 0.5 LMH/bar) than OmpF membranes (2.6 ± 0.3 LMH/bar). From these results, an effective pore diameter was calculated using a modified Hagen-Poiseuille’s equation.57 The effective pore size based on flow is larger for OmpF membranes than for non-OmpF membranes, which demonstrates a flux enhancement due to the presence of OmpF. Note that this pore size is not an actual value of the pores but rather represents a nominal pore size. This means that the presence of OmpF increases the water permeability compared to the non-OmpF membranes, which in turn is associated to a bigger effective pore diameter. The effective pore size suggests a larger permeability due to the presence of OmpF.

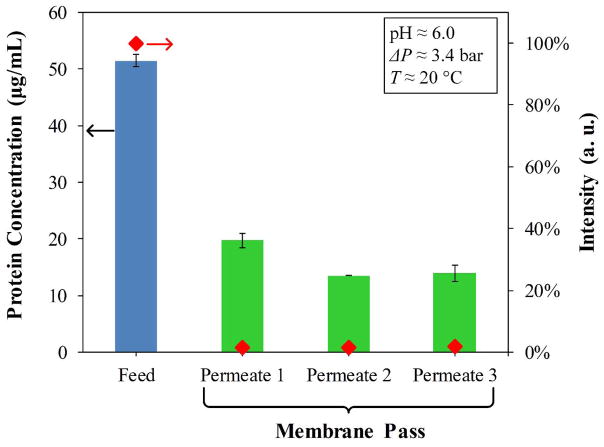

From the enhanced BCA assay, the material balance of the OmpF solutions passed-through the PVDF-PAA-PAH membranes in Figure 9 presents the feed (with 50 μg/ml) and the subsequent permeates, which are in the range of detection. A permeate of one pass becomes the feed of the next; for instance, Permeate 1 = Feed 2. By the third pass, no decrease in concentration between feed (Permeate 2) and Permeate 3 is observed, suggesting that only two passes of OmpF solution are necessary. On the other hand, fluorescence labelling with 5 μg/ml porin is almost insignificant which demonstrates the effective OmpF immobilization by LbL functionalization. This also confirmed by fluorescence spectra of the Feed and the Permeate of the FITC Labelled OmpF solutions, shown in Figure S5 in ESI.

Figure 9.

OmpF concentration and normalized fluorescence (FITC) intensity of feed and permeate streams during layer-by-layer functionalization on PVDF-PAA-PAH membrane. Original PVDF: Nanostone PV200 with pore size of 48 ± 1 nm. FITC labelled OmpF expt: Note the feed concentration for this experiment was 5 μg/ml. Permeate showing very low intensity of FITC Labelled OmpF (red diamond) indicating high retention during each pass.

For the first and second passes of OmpF solution, protein loaded was 1.74 g/m2 of membrane after two passes. The total number of OmpF’s loaded can be determined from their molecular weight. The permeation of 50 mL DIUF water at pH = 6 and 6.8 bar contained non-detectable OmpF, suggesting secure immobilization of the protein. The OmpF feed used was 51–53 μg/mL for all membranes produced.. The charges of OmpF’s outer, exposed residues, or those in the extracellular loops at the top and bottom of the β-barrel are mainly positive at low pH and negative at high pH.56 Thus, with the second layer of polyelectrolytes being PAH and essentially having neutral charge, OmpF pores can be oriented parallel to the flux through the membrane. It is also likely that while loosely bound valeric acid molecules were washed away, tightly bound ones will remain in forming a protection layer around the hydrophobic part of the protein, with the acid head group facing out to the positive charge leftovers of the PAH layer.

3.3. Rejection of Solutes

Glucose, sucrose, PEG and Dextran with different molecular weights were mixed separately with salts (NaCl or CaCl2) in each solution. Table 1 shows the hydrodynamic radii (rH), the hydrated radii and the molecular weight of the solutes used for different references.58–71 The different values of molecular weights and their corresponding rH, were correlated for Dextran and poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG) molecules, while mean values were used for glucose and sucrose. From these correlations, the calculated values were used in the rejections studies for each of the species, see Figures S3 and S4 in the ESI section 7. It is important to note that the two largest molecules have merely an average rH of a normally-distributed range of sizes. PEG and Dextran molecules show polydispersity because the length of their chains is not controllable during synthesis. Also, the exact way the chain coils is not consistent and depends on the solvent. Long polymer chains of the same degree of polymerization do not “balled-up” in the same way.69, 72 Thus, although it seems like 100% rejection should be observed for these molecules with number-average sizes well above the dimensions of OmpF’s constriction zone, the membrane could be defective or there could be polymer chains possessing lengths, and consequently radii, significantly smaller than the average.

In the case of the ions, large differences are depicted between the Stokes and the rH in Table 1. However, reported values show high variation and only a few are depicted here. This phenomena was initially discussed by Nightingale and later by Tansel et al.59, 73 Briefly, the Stokes radius in some ions, like Cl−, is dependent on temperature change and therefore chloride becomes more hydrated at higher temperatures but also, Cl− is able to lose its hydration water during permeation. The Stokes radius of Na+ varies slightly with temperature. On the other hand, for Ca2+, both Stokes and rH are independent of temperature. Na+ and often Ca2+ are not large enough compared to the water molecule to satisfy the Stokes law. Because Na+ has very low charge dispersion, the hydration water is more strongly held. Ca2+ retains less its hydration water than other divalent ions, like Mg2+, making Ca2+ more suitable for adsorption on the membrane surface. Still, the rejection of Ca2+ is higher than Na+ because the rH for Ca2+ is larger than Na+.

3.3.1. Control Studies with OmpF in Track-etched Polycarbonate Membranes

The OmpF immobilization within the track-etched PC50 membrane shows that the permeability of water at 3.4 bar and pH = 6.0 went from 204 ± 2 LMH/bar to 20 ± 0.54 LMH/bar, implying OmpF immobilization. No protein was rejected into the retentate and a rinse on the surface did not remove any protein either. A material balance revealed an immobilization of 1.01 g/m2 of OmpF. These results reveal that the OmpF can be immobilized under pressure. In the case of mechanical wedging however, subsequent rejection tests of the salt/organic mixtures revealed that the PC50-OmpF membrane rejected nothing significant (all rejections were < 9%) and over the duration of the rejections, permeability increased up to 54 LMH/bar, indicating some OmpF loss. This result confirms that immobilization of OmpF by simple mechanical wedging is temporary and unstable. One explanation to this behavior is that the extracellular loops on the OmpF help them to be attached to the charge leftovers in the LbL assembly, and this feature helps OmpF immobilization.

3.3.2. Rejection of Organic and Inorganic Solutes throughout Functionalization

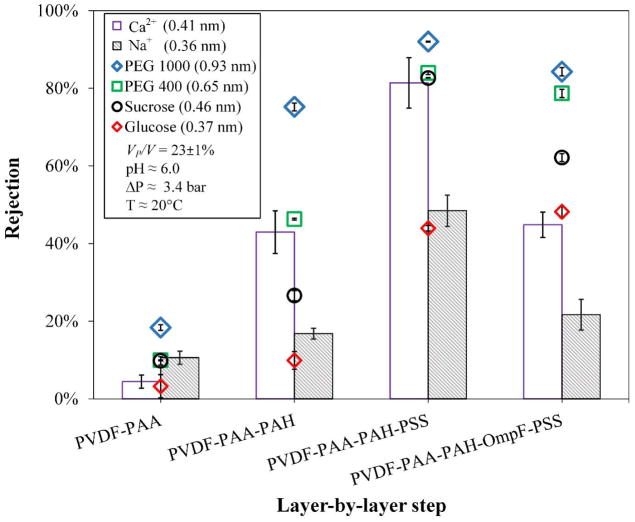

Each additional layer of functionalization increases the rejection of all solutes, as seen in Figure 10. The rejections were measured with each of the salt-organic mixtures in three cycles as explained. Here, rejections are calculated from the formula R = 1− CP/C, where CP is the cumulative concentration of permeate and C is the concentration of retentate, per salt and per model organic solute. These trends, are horizontally asymptotic as the size of the model organic solutes increases as they approach 100% rejection, with almost the same recovery (VP/V), where VP is the cumulative permeate volume and V the feed or retentate volume. When comparing the fully functionalized membrane with and without OmpF, rejections of the model organic solutes are slightly different between these two membranes with higher rejections for the non-OmpF membranes, except for glucose, which has a negligible difference between the non-OmpF and the OmpF membranes, and demonstrate that glucose still overcome the OmpF cutoff (~ 650 Da), see Table 1.

Figure 10.

Rejection of different organic molecular sizes and inorganic salts for each layer of the layer-by-layer functionalization. Ca2+ and Na+ as CaCl2 and NaCl, respectively. Membrane used: PVDF (Nanostone PV200). Some error bars are inside the symbols or are negligible.

Sucrose also could pass due to its low molecular weight, but has larger difference in rejections (83 to 62%). It is possible that OmpF’s elliptical opening (1.1 × 0.7 nm) allows sucrose to orientate in such a way that it can pass through more easily than through a rounded pore of the same diameter. In addition to that, sucrose is in the limits of the OmpF molecular cutoff, and that the presence of protein channels could help to form sucrose-calcium complex, which facilitate sucrose transport through the OmpF membranes.74 OmpF have shown to open larger at high and low pH, and although pH values were around neutral (pH = 6.0), this phenomenon could have been replicated by interactions with individual ions and molecules. This makes OmpF’s midsection open and close due to ionization, with the above constriction zone measurements only true for the non-hydrated channel. These rejections of OmpF membranes do not expound what OmpF fully and partially rejects, since it is not clear what portion of large and small channels (from 0.35 to 0.16 nm, respectively) predominates. The constriction region is mostly hydrophobic at low pH values due to its net negative charge42, 75. Additionally, the switch from small to large channel is abrupt in very small pH range, which becomes difficult to control having other charged moieties present in the layers; it is also feasible that there are fewer pores in the membrane with no OmpF, allowing solutes to pass.

OmpF-membranes significantly reject uncharged molecules higher than 1 nm while allowing ions to pass through. Even though the membranes in this study are for microfiltration, due to their functionalization they may behave as UF and nanofiltration (NF) membranes with similarities to the NF in terms of size and charge (shown by the ζ potential in Figure 7). The molecular cutoff of the OmpF membrane still needs to be improved, but it can be observed that the type of the organic compounds used did not affect the rejection of the salt, a feature that some conventional UF membranes do not possess. It is worth noting that the experiments performed were designed for dilute concentrations, and increasing the concentrations of model organics would generate additional effects, such as concentration-polarization or pore blocking/constriction.

With almost similar rH, OmpF membranes selectively allow the pass of more salts than the non-OmpF ones. The behavior of the non-OmpF membrane is comparable to previous results from our group in NF membranes: in the non-OmpF, the rejections of CaCl2 and NaCl are 81 and 48%, respectively, while in NF membranes go from 83 and 44% to 95 and 92% depending on the hydrophilicity of the membrane.76 This implies a ratio of about 2 between the divalent and the monovalent ions for the more hydrophilic membranes. This ratio is conserved in the OmpF membranes but with lower values: sodium chloride rejection is 22% and calcium chloride is 45%, while the rejection of the model organics remains almost the same, except from sucrose, as explained previously. A plausible explanation for this behavior is that the positive charge on Ca2+ and Na+ at the operating pH results in them being transported through the OmpF.34 This is corroborated later when the effect of pH in salt rejection is analyzed. Therefore, the membrane containing OmpF demonstrates superior selectivity over NF membranes and the ones containing various polymeric layers. Although NF membranes have sharper cutoff and fully functionalized non-OmpF membranes reject organics slightly higher than OmpF membranes, with similar permeability, OmpF membranes are able to permeate charged ions from uncharged molecules, feature that had not been reported previously in LbL studies. In fact, non-OmpF membranes reject CaCl2 (Figure 10) as well as it rejects larger organics; the exposed charges of the polymeric layers likely are improving ionic rejection and sacrificing selectivity. The selectivity of the OmpF membrane implies an advantage in reducing salt concentration in the retentate stream, and improvements in LbL assembly could increase the rejection and the selectivity performances.

To estimate this salt/organic selectivity (α), one could calculate a ratio of the sieving coefficients of each of the species (α = (1 − Rsalt)/(1 − Rorg)), or the ratio of concentrations in permeate over retentate.26, 77 Values of α > 1 mean that salts are being filtrated, increasing permeate specific concentrations during the process. In contrast, α < 1 correspond to an increase in salt concentration in the retentate. From the data on the Figure 10, one can calculate the ratio of rejections Rorg/Rsalt for PEG 1000 for example, which goes from 1.8 to 3.9 times in the OmpF membranes, depending on the salt used. This represents higher filtration selectivity for salts, with α values from 3.5 to 5.0, see Table 2.

Table 2.

Selectivity values for salt/organic molecule separations

| Membrane | Glucose | Sucrose | PEG 400 | PEG 1000 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Na+ | Ca2+ | Na+ | Ca2+ | Na+ | Ca2+ | Na+ | Ca2+ | |

| PVDF-PAA | 0.92 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 1.06 | 0.99 | 1.06 | 1.09 | 1.17 |

| PVDF-PAA-PAH | 0.92 | 0.63 | 1.13 | 0.78 | 1.55 | 1.06 | 3.35 | 2.30 |

| PVDF-PAA-PAH-OmpF-PSS | 0.92 | 0.33 | 2.97 | 1.07 | 3.21 | 1.16 | 6.45 | 2.33 |

| PVDF-PAA-PAH-PSS | 1.51 | 1.06 | 2.07 | 1.46 | 3.67 | 2.59 | 4.98 | 3.51 |

For the OmpF membrane, more significant selectivity values are achieved with NaCl than CaCl2, likely owing to the slightly higher rH of the calcium salt. In order to observe the effects of osmotic pressure on permeability over time in the case of significant rejections (those in non-OmpF membranes), much larger initial salt concentration and much more time is needed.

The rejections were calculated as an average from multiple passes of salts and model organic solute combinations for each membrane type, taking into account the error propagation for calculations. For all tests, permeability and recovery were consistent and not affected by the presence of the solutes, this is one confirmation of the OmpF-membrane stability.

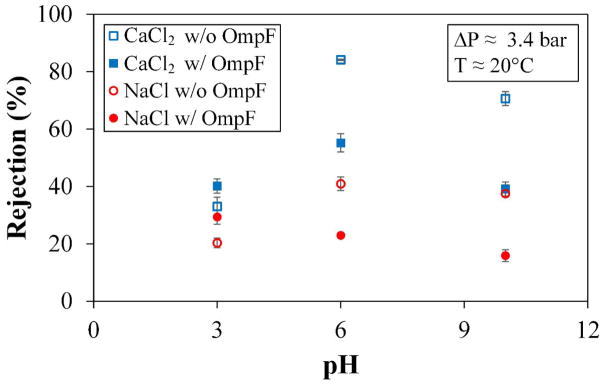

3.3.3. Effect of pH on Salt Rejection and Permeability

The functional behavior based on pH between OmpF and non-OmpF membranes shows that the membranes lacking OmpF have a much more drastic increase in salt rejection from a low to a neutral-range pH than from neutral to high (salt solutions at pH = 6.0 were not adjusted), see Figure 11. Change in permeability is similar between the two membranes, with lower flux for low pH and higher flux for high pH. The behavior of OmpF with CaCl2 on the other hand, is affected by an increase in Donnan potential with the increase of pH, making the channel more negative inside. This phenomenon creates a simple calcium-polyelectrolyte interaction that could possibly be binding negative charges, resulting in a pseudo-cross-linking of the polyelectrolytes by chelation. The transport of calcium through the OmpF membrane due to its divalent nature causes the ion to lodge and dislodge in trapping events, as reported, through the protein channel.37

Figure 11.

Rejections of salts at different pH values. Membrane used: PVDF (Nanostone PV200) with OmpF layer (-PAA-PAH-OmpF-PSS) and without OmpF layer (-PAA-PAH-PSS). Membrane used: PVDF (Nanostone PV200) with a layer-by-layer functionalization. Some error bars are inside the symbols or are negligible.

The rejection of NaCl is different. NaCl rejection by OmpF membranes presents a slightly negative, linear trend with increase in pH due to its smaller size and an enlargement of the OmpF channels, as previously reported.38, 42. Sodium’s slightly smaller rH coupled with a smaller presence of PSS in the OmpF-membrane means that more sodium could bypass outer surface charges of PSS and make its way into the OmpF pore. This would cause the protein’s pore residues to dominate the rejection mechanism over the possible rejection by the PSS that secure the OmpF. Overall, the effect is an increase in the partitioning between monovalent salts and non-charged molecules, as seen in Figure 10.

However, an important feature is also presented in Figure 11: In both salts, the rejection is lower in OmpF-membranes than in non OmpF-membranes. For pH = 3.0, the rejection values can be related to affinity between charges on the external PSS layer and low Donnan potential, but either way, the difference between OmpF- and non OmpF-membranes is not significant in this pH range.

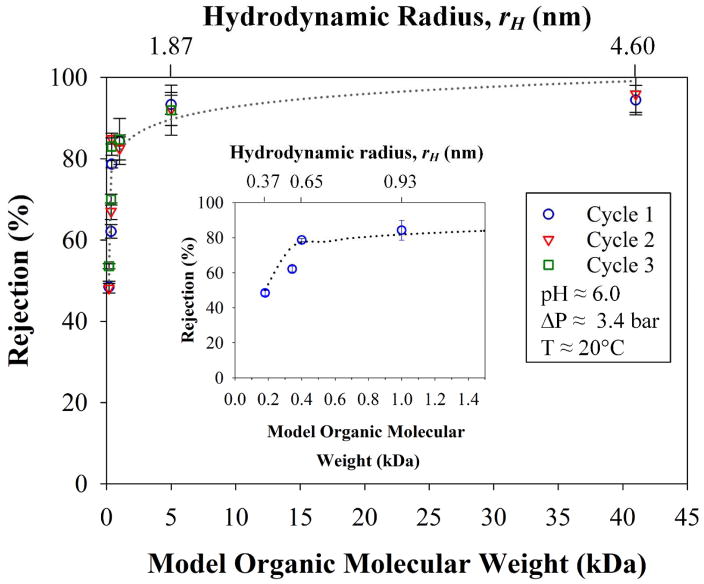

3.4. Stability and Material Balance in OmpF LbL Membranes

The stability and consistency of the rejections for OmpF membranes was tested in three cycles for all organic solutes shown in Table 1. In Figure 12, all the solutions were permeated through the membrane for an average of 8 h/day in three weeks, demonstrating the exceptional resiliency of the membrane with extremely consistent values, and with an estimated error of only 3.3%. The logarithmic pattern (dash lines in Figure 12) again correlates rejection with the molecular weight of the organic compounds (R2 = 0.90) and thus, with rH values of the solutes used. It is also worth to note that the rejection plateau is reached at 84% from molecular weights of 0.4 to 1.0 kDa and then, at 5 kDa the rejection is 92%, see Figure 12. The mean recovery, 24 ± 1%, for these cycles is also constant and similar to the previous results. It is worth to note that there is an increase in the recovery (up to 9%) after the first cycle due to adsorption, mainly for solutes with lower molecular weights. These adsorptions and measurement errors were up to absolute 8% in all experiments performed and have to be taken into account as imbalances in the material balances, see ESI section 8. At this point, it is confirmed again that OmpF membranes selectively separate the model organic solutes from salts that exceed 40% rejection.

Figure 12.

Rejections of solutions with different molecular weights of model organic solutes over the course of three cycles. Insert: First cycle denoting rejections for the smaller molecular weights. For comparison purposes molecule radius is included in the top axis. Membrane used: PVDF (Nanostone PV200) with a layer-by-layer functionalization of PAA-PAH-OmpF-PSS. Some error bars are inside the symbols or are negligible.

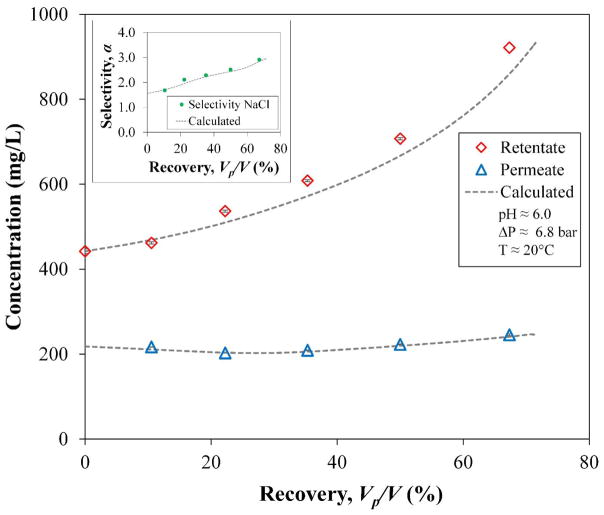

Using a model solution of sucrose and NaCl, a material balance for a batch process was calculated, taking samples of retentate and cumulative permeate over time. Assuming that density does not change due to low solute concentration, the total and the solute mass balances can be calculated by

| (1) |

| (2) |

where J is the flux of the solution through the membrane, A is the area normal to the direction of flux, and V is the volume of the feed-retentate through time t, and C and Cp are the concentrations of retentate and permeate at any given time, respectively.

To calculate the batch operation, analytical integration between the initial and final concentrations, C0 and C, gives the retentate volume V as a function of its concentration in every step of the integration, leaving only one numerical integration for t using the functions of the experimental data (J and Cp vs. C). The experimental and integration values in Figure 13 show an expected increase of the retentate C as well of α values of NaCl, and consequently, an almost constant behavior of the cumulative permeate, CP. This confirms again that OmpF membranes increase the selective filtration of salts over non-charged organics through time. Comparing the two data sets by a two tails t-test shows that there is no evidence of a difference between experimental and calculated values (|t| = 1.046 < 2.023 with α = 0.05).

Figure 13.

Measured and calculated concentrations over time for a solution of sucrose and NaCl. Insert: Filtration selectivity of NaCl from sucrose. Membrane used: PVDF (Nanostone PV200) with layer-by-layer functionalization of PAA-PAH-OmpF-PSS. Sucrose initial concentration, C0 = 442.05±0.85 mg/L. Initial volume, V0 = 0.190 L. Some error bars are inside the symbols or are negligible.

4. CONCLUSIONS

Successful immobilization of OmpF by LbL method within a functionalized membrane was achieved. This procedure opens a new approach for the incorporation of biomolecules into an artificial membrane showing better selectivity of ions over non-charged molecules and although with less sharp cutoff, comparable rejection values to NF and LbL non-OmpF membranes Understanding the behavior of the charged and uncharged parts on the exterior of OmpF will improve the fluxes and rejections. This topic has not been explored without using lipid bilayers or vesicles for immobilization. Development in this field could show better alignment within the nanocomposite membrane matrix.

With almost similar pore sizes, OmpF-membranes separate more salts than model organics from the mixtures. Salt rejections through OmpF-membrane by LbL assembly are much lower than that of the polymeric membrane without OmpF. This means that OmpF-membranes have a higher selectivity in the separation of ions over non-charged molecules than NF membranes and LbL membranes without OmpF, allowing these ions to pass through the membrane while rejecting some non-charged molecules. For CaCl2, rejection ratios (Rorg/Rsalt) are up to 1.7 times higher than a non-OmpF membrane, while NaCl go up to 2.1 times higher than the non-OmpF membrane.

The OmpF-membrane is stable and consistent in all cycles tested, suggesting durability of the membrane for more than 160 h. Solutions flow through both immobilized OmpF pores and the spaces between the layers reaching 84 % of rejection from 0.4 to 1.0 kDa and more than 92 % rejection for 5 kDa with almost double permeation of salts. A unique pH responsiveness of the LbL membrane with OmpF, observed as it changes in permeability and salt rejection, is an indicator that solution is passing mostly through OmpF. Also, the unimproved rejection of salts and organics in track-etched polycarbonate membranes and merely temporary decrease of flux proves that LbL stabilizes OmpF within the membranes and improves their performance. FITC labelled OmpF studies by fluorescence analysis (confocal microscope, and through feed/permeate analysis) further verified stability (and no loss) of porins.

Various methods of verifying the cross-linking of PAA and the subsequent layer depositions of PAH, OmpF and PSS onto a PVDF microfiltration membrane were successful, including pH responsiveness, changes in flux, and ζ potential. The unique behavior of the functionalized PVDF membranes with immobilized OmpF is a promising result, suggesting OmpF are immobilized. The membrane, potentially provides more mechanical stability than bioinspired membranes with traditional ruptured lipid bilayer or vesicles containing biomolecular channels. Most importantly, this work could be applied for immobilizing other biomolecules, such as aquaporins that have the potential to reject 100% of nearly all solutes.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This work was supported by the National Science Foundation NSF KY EPSCoR program (Grant no: 1355438), and the National Institutes of Environmental Health Sciences NIEHS-SRC (grant number P42ES007380).

The authors want to thank the collaboration of Nanostone Water Inc. related to PVDF membrane scale-up, and the Environmental Research Training Laboratories at the University of Kentucky.

Footnotes

5. ELECTRONIC SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION (ESI)

Detailed methods and analysis are illustrated in the ESI material. These include sections on OmpF solution and membrane functionalization and characterizations; ξ potential procedures; preliminary characterization of concentrations of feed retentate and permeate; membrane selection; optimization of PAA functionalization; FITC labelled Ompf analysis of feed and permeate; model organic compound regressions; and material imbalance minimization.

References

- 1.Qi S, Wang R, Chaitra GKM, Torres J, Hu X, Fane AG. J Membrane Sci. 2016;508:94–103. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Turner K, Khatwani S, Daunert S. Responsive Membranes and Materials. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012. pp. 243–268. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li X, Chou S, Wang R, Shi L, Fang W, Chaitra G, Tang CY, Torres J, Hu X, Fane AG. J Membrane Sci. 2015;494:68–77. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shen Y-x, Saboe PO, Sines IT, Erbakan M, Kumar M. J Membrane Sci. 2014;454:359–381. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Liu Y-Q, Zhang Y-L, Fu X-Y, Sun H-B. Acs Appl Mater Inter. 2015;7:20930–20936. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b06326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hinds B. Responsive Membranes and Materials. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012. pp. 51–71. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Licsandru E, Kocsis I, Shen Y-x, Murail S, Legrand Y-M, van der Lee A, Tsai D, Baaden M, Kumar M, Barboiu M. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:5403–5409. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b01811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider S, Licsandru E-D, Kocsis I, Gilles A, Dumitru F, Moulin E, Tan J, Lehn J-M, Giuseppone N, Barboiu M. J Am Chem Soc. 2017;139:3721–3727. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Werber JR, Osuji CO, Elimelech M. Nature Reviews Materials. 2016;1:16018. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sholl DS, Lively RP. Nature. 2016;532:435–437. doi: 10.1038/532435a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shen YX, Si W, Erbakan M, Decker K, De Zorzi R, Saboe PO, Kang YJ, Majd S, Butler PJ, Walz T, Aksimentiev A, Hou JL, Kumar M. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2015;112:9810–9815. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1508575112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kim Y-R, Jung S, Ryu H, Yoo Y-E, Kim SM, Jeon T-J. Sensors-Basel. 2012;12:9530. doi: 10.3390/s120709530. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang X, Tanner P, Graff A, Palivan CG, Meier W. Journal of Polymer Science Part A: Polymer Chemistry. 2012;50:2293–2318. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kang G-D, Cao Y-M. J Membrane Sci. 2014;463:145–165. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Husson SM. Responsive Membranes and Materials. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012. pp. 73–96. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lewis SR, Smuleac V, Xiao L, Bhattacharyya D. Responsive Membranes and Materials. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd; 2012. pp. 97–142. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wandera D, Wickramasinghe SR, Husson SM. J Membrane Sci. 2010;357:6–35. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yuk H, Zhang T, Lin S, Parada GA, Zhao X. Nat Mater. 2016;15:190–196. doi: 10.1038/nmat4463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wisniewska M, Urban T, Grzadka E, Zarko VI, Gun’ko VM. Colloid Polym Sci. 2014;292:699–705. doi: 10.1007/s00396-013-3103-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hernandez S, Papp JK, Bhattacharyya D. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2014;53:1130–1142. doi: 10.1021/ie403353g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Decher G, Hong JD, Schmitt J. Thin Solid Films. 1992;210:831–835. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smuleac V, Butterfield DA, Bhattacharyya D. Langmuir. 2006;22:10118–10124. doi: 10.1021/la061124d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Butterfield DA, Bhattacharyya D, Daunert S, Bachas L. J Membrane Sci. 2001;181:29–37. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang M, Wang Z, Wang X, Wang S, Ding W, Gao C. Environ Sci Technol. 2015;49:3761–3768. doi: 10.1021/es5056337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zydney A. In: Encyclopedia of Membranes. Drioli E, Giorno L, editors. Springer Berlin Heidelberg; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2015. pp. 1–2. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mehta A, Zydney AL. J Membrane Sci. 2005;249:245–249. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Saint N, Lou KL, Widmer C, Luckey M, Schirmer T, Rosenbusch JP. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:20676–20680. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schirmer T, Phale PS. J Mol Biol. 1999;294:1159–1167. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1999.3326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nikaido H. The Journal of General Physiology. 1981;77:121–135. doi: 10.1085/jgp.77.2.121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nikaido H, Rosenberg EY, Foulds J. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:232–240. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.232-240.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Nikaido H, Rosenberg EY. J Bacteriol. 1983;153:241–252. doi: 10.1128/jb.153.1.241-252.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kojima S, Nikaido H. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:E2629–2634. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1310333110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Robertson KM, Tieleman DP. Febs Lett. 2002;528:53–57. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)03173-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cama J, Bajaj H, Pagliara S, Maier T, Braun Y, Winterhalter M, Keyser UF. J Am Chem Soc. 2015;137:13836–13843. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b08960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ziervogel Brigitte K, Roux B. Structure. 2013;21:76–87. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2012.10.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nikaido H, Vaara M. Microbiol Rev. 1985;49:1–32. doi: 10.1128/mr.49.1.1-32.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hijkoop VJv, Dammers AJ, Malek K, Coppens M-O. The Journal of Chemical Physics. 2007;127:085101. doi: 10.1063/1.2761897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Todt JC, Rocque WJ, McGroarty EJ. Biochemistry-Us. 1992;31:10471–10478. doi: 10.1021/bi00158a009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Benz R, Janko K, Lauger P. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1979;551:238–247. doi: 10.1016/0005-2736(89)90002-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schindler H, Rosenbusch JP. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1978;75:3751–3755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.75.8.3751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Buehler LK, Rosenbusch JP. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1993;190:624–629. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1993.1094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Todt JC, McGroarty EJ. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1992;189:1498–1502. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(92)90244-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Klara SS, Saboe PO, Sines IT, Babaei M, Chiu PL, DeZorzi R, Dayal K, Walz T, Kumar M, Mauter MS. J Am Chem Soc. 2016;138:28–31. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b03320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kumar M, Grzelakowski M, Zilles J, Clark M, Meier W. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20719–20724. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708762104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang H, Chung TS, Tong YW, Jeyaseelan K, Armugam A, Chen Z, Hong M, Meier W. Small. 2012;8:1185–1190. 1125. doi: 10.1002/smll.201102120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taylor R, Burgner JW, Clifton J, Cramer WA. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:31113–31118. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.47.31113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holzenburg A, Engel A, Kessler R, Manz HJ, Lustig A, Aebi U. Biochemistry-Us. 1989;28:4187–4193. doi: 10.1021/bi00436a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yoshimura F, Zalman LS, Nikaido H. J Biol Chem. 1983;258:2308–2314. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Garavito RM, Rosenbusch JP. Methods in enzymology. 1986;125:309–328. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(86)25027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Arcidiacono S, Butler MM, Mello CM. Protein Expr Purif. 2002;25:134–137. doi: 10.1006/prep.2002.1619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Xiao H, Hong D, Zhu T, Liu S, Li G. Journal of Applied Electrochemistry. 2009;39:1163–1167. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Jarząb A, Witkowska D, Ziomek E, Dąbrowska A, Szewczuk Z, Gamian A. Plos One. 2013;8:e70539. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0070539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hernández S, Lei S, Rong W, Ormsbee L, Bhattacharyya D. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering. 2016;4:907–918. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.5b01005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Smuleac V, Varma R, Sikdar S, Bhattacharyya D. J Memb Sci. 2011;379:131–137. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2011.05.054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xiao L, Davenport DM, Ormsbee L, Bhattacharyya D. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2015;54:4174–4182. doi: 10.1021/ie504149t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Aguilella VM, Queralt-Martin M, Aguilella-Arzo M, Alcaraz A. Integr Biol (Camb) 2011;3:159–172. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00048e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Smuleac V, Bachas L, Bhattacharyya D. J Memb Sci. 2010;346:310–317. doi: 10.1016/j.memsci.2009.09.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dove PM, Nix CJ. Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta. 1997;61:3329–3340. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Nightingale ER. The Journal of Physical Chemistry. 1959;63:1381–1387. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kasianowicz JJ, Kellermayer M, Deamer D. Structure and Dynamics of Confined Polymers: Proceedings of the NATO Advanced Research Workshop on Biological, Biophysical & Theoretical Aspects of Polymer Structure and Transport Bikal; Hungary. 20–25 June 1999; Springer Netherlands; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pappenheimer JR. Physiological Reviews. 1953;33:387–423. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1953.33.3.387. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ramm LE, Whitlow MB, Mayer MM. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982;79:4751–4755. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.15.4751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ribeiro ACF, Ortona O, Simões SMN, Santos CIAV, Prazeres PMRA, Valente AJM, Lobo VMM, Burrows HD. Journal of Chemical & Engineering Data. 2006;51:1836–1840. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sabek OM, Ferrati S, Fraga DW, Sih J, Zabre EV, Fine DH, Ferrari M, Gaber AO, Grattoni A. Lab Chip. 2013;13:3675–3688. doi: 10.1039/c3lc50601k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schultz SG, Solomon AK. J Gen Physiol. 1961;44:1189–1199. doi: 10.1085/jgp.44.6.1189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lebrun L, Junter GA. Enzyme and Microbial Technology. 1993;15:1057–1062. doi: 10.1016/0141-0229(93)90054-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ghandehari H, Smith PL, Ellens H, Yeh PY, Kopecek J. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1997;280:747–753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ling K, Jiang H, Zhang Q. Nanoscale Res Lett. 2013;8:538. doi: 10.1186/1556-276X-8-538. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pluen A, Netti PA, Jain RK, Berk DA. Biophys J. 1999;77:542–552. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(99)76911-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Baron-Epel O, Gharyal PK, Schindler M. Planta. 1988;175:389–395. doi: 10.1007/BF00396345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Choi JJ, Wang S, Tung YS, Morrison B, 3rd, Konofagou EE. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2010;36:58–67. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2009.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Masuelli MA. Journal of Polymer and Biopolymer Physics Chemistry. 2013;1:13–21. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tansel B, Sager J, Rector T, Garland J, Strayer RF, Levine L, Roberts M, Hummerick M, Bauer J. Sep Purif Technol. 2006;51:40–47. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Leitão TJ, Tenuta LMA, Ishi G, Cury JA. Brazilian Oral Research. 2012;26:100–105. doi: 10.1590/s1806-83242012000200003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jap BK, Walian PJ. Physiol Rev. 1996;76:1073–1088. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1996.76.4.1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Colburn AS, Meeks N, Weinman ST, Bhattacharyya D. Ind Eng Chem Res. 2016;55:4089–4097. doi: 10.1021/acs.iecr.6b00098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Umpuch C, Galier S, Kanchanatawee S, Balmann HR-d. Process Biochem. 2010;45:1763–1768. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.