ABSTRACT

Ionizing radiation (IR) elevates mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) in response to the energy requirement for DNA damage responses. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) released during mitochondrial OXPHOS may cause oxidative damage to mitochondria in irradiated cells. In this paper, we investigated the association between nuclear DNA damage and mitochondrial damage following IR in normal human lung fibroblasts. In contrast to low-doses of acute single radiation, continuous exposure of chronic radiation or long-term exposure of fractionated radiation (FR) induced persistent Rad51 and γ-H2AX foci at least 24 hours after IR in irradiated cells. Additionally, long-term FR increased mitochondrial ROS accompanied with enhanced mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) and mitochondrial complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase) activity. Mitochondrial ROS released from the respiratory chain complex I caused oxidative damage to mitochondria. Inhibition of ATM kinase or ATM loss eliminated nuclear DNA damage recognition and mitochondrial radiation responses. Consequently, nuclear DNA damage activates ATM which in turn increases ROS level and subsequently induces mitochondrial damage in irradiated cells.

In conclusion, we demonstrated that ATM is essential in the mitochondrial radiation responses in irradiated cells. We further demonstrated that ATM is involved in signal transduction from nucleus to the mitochondria in response to IR.

KEYWORDS: Long-term fractionated radiation, mitochondria, ATM, parkin, ROS

Introduction

Ionizing radiation (IR) induces DNA double strand breaks (DSBs) and its deleterious effect is the main biological concern.1 As a result of high doses of IR exposure, apoptotic signals arising from severe DNA DSBs in the nucleus are transmitted to mitochondria, which then release cytochrome c to induce apoptosis in irradiated cells.2 IR also affects other organelles such as the plasma membrane, cytoskeleton, mitochondria, endoplasmic reticulum, Golgi apparatus, and lysosomes.3 Mitochondrial signaling is associated with the adaptive response and bystander effect at low or moderate doses of IR.4,5 Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) can damage nuclear DNA (nDNA) leading to genomic instability in the irradiated cells.6, 7 IR preferentially causes loss-of-function mutations in mtDNA than in nDNA because the majority of the mitochondrial genome contains genes. Thus, it is of special importance to clarify the effect of IR on mitochondrial function.

Mitochondria govern many metabolic processes. Oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) is defined as an electron transfer chain driven by substrate oxidation that creates an electrochemical transmembrane gradient. Mitochondrial membrane potential (ΔΨm) consists of a proton gradient that drives adenosine-5′-triphosphate (ATP) synthesis.8 The energy produced in this pathway is essential to the DNA damage response (DDR) process for maintaining the genome stability of cells.9

During OXPHOS, mitochondria release superoxide anions (O2−), which are then converted to hydrogen peroxide (H2O2) by Mn-superoxide dismutase (MnSOD).7 Glutathione (GSH) further reduces H2O2 to water. However, redox perturbation due to GSH deficiency leads to excessive ROS and oxidative insults on cellular components, such as nucleic acids, proteins, and lipids.10 mtDNA is located at the inner mitochondrial membrane close to the sites of ROS production. Due to its chronic exposure to ROS, mtDNA has a high mutation rate.11,12 To control the quality of mitochondria, the contents of damaged and healthy mitochondria are mixed,13,14 or the mitochondria undergo the selective degradation (mitophagy).15,16 Phosphatase and tensin homolog induced putative kinase 1 (PINK1) and the parkin E3 ubiquitin ligase play key roles in mitochondrial quality control by recogning abnormal mitochondria with low membrane potential.17 Parkin normally localized in the cytoplasm is relocated to abnormal mitochondria with low ΔΨm and promotes their clearance via mitochondrial degradation by autophagy (mitophagy).18,19 Functional loss of mitochondria alters cellular metabolism and is strongly correlated with carcinogenesis, aging, and neurodegeneration. We recently determined that repeated exposure to fractionated radiation (FR) with low doses of X-rays for 31 d (long-term) induces mitochondrial damage in human fibroblasts.20,21 Mitochondria are thought to be a major target for oxidative stress induced by long-term FR.22 However, the mechanism of IR-induced mitochondrial damage remains unclear.

Here we investigated the cross-talk between the nucleus and the mitochondria in response to IR in normal human fibroblasts. We found that the nDNA damage activates mitochondrial OXPHOS and causes mitochondrial damage in irradiated cells.

Results

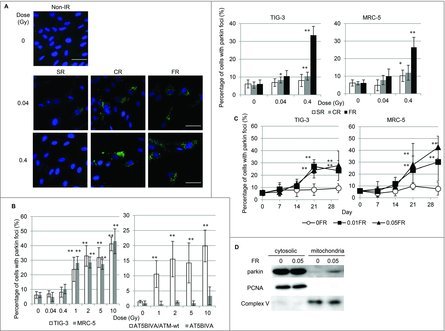

Chronic radiation or long-term FR induces mitochondrial damage in human fibroblasts

We investigated radiation-induced mitochondrial damage in normal human lung fibroblasts (TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells) exposed to chronic gamma radiation (CR) (0.04 and 0.4Gray (Gy); 0.01Gy or 0.1Gy/d for 4d, respectively) or FR (0.01Gy/fraction twice a day, 5 d/wk for 2 d or 28 d). Another cohort of cells underwent acute single radiation (SR) with the same total dosage. Cells were immunostained with an antibody specific for the E3 ubiquitin ligase, parkin, which recognizes damaged mitochondria with low ΔΨm. Parkin foci were evident in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells exposed to low doses of CR or FR at 24 hours after IR (Fig. 1A and supplemental Fig. 1). There was a statistically significant increase in the number of cells displaying parkin foci following 0.4Gy of CR or FR in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells compared to non-irradiated cells (Fig. 1A, right panel). In contrast to both exposures, SR did not increase the number of cells with parkin foci at low doses (below 0.4Gy). However, parkin foci did appear when cells were exposed to >1Gy of SR in both TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells (Fig. 1B left panel). ATM-deficient cells showed no induction of parkin foci by >1Gy of SR (Fig. 1B, right panel and supplemental Fig. 1), suggesting that ATM is involved in IR-induced parkin foci in human fibroblasts. We have previously reported that oxidative DNA damage by measuring amounts of 8-Hydroxydeoxyguanosine (8-OHdG) and apurinic/apyrimidinic (AP) site was accumulated in the mtDNA following long-term FR compared to that in non-irradiated cells.20 We monitored mitochondrial damage by observing the formation of parkin foci during FR for 31d (long-term FR). The parkin foci were induced by FR with 0.01Gy or 0.05Gy/fraction for >21 d (total 0.3 or 1.5Gy, respectively) in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells. Cells cultivated for 31 d without FR did not display an increase in the number of cells with parkin foci (Fig. 1C). We further quantified the amounts of mitochondrial damage by western blotting. This analysis revealed that parkin was accumulated to a greater extent in mitochondria of TIG-3 cells following long-term FR compared to non-irradiated 0FR cells (Fig. 1D). Thus, IR-induced mitochondrial damage varies with the irradiation method, dose, and duration of radiation exposure.

Figure 1.

Parkin focus formation in response to acute SR, CR or FR. (A) Images of parkin staining in non-irradiated control cells and TIG-3 cells exposed to acute SR, CR, or FR for 24hours after IR. The scale bar represents 50 µm. Percentage of cells with parkin foci in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells was shown for each irradiation method in the graph. (B) Percentage of cells with parkin foci in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells was shown for acute SR at the indicated doses on the left graph. Percentage of cells with parkin foci in AT5BIVA (ATM-deficient) and AT5BIVA/ATM-wt is shown on the right graph. (C) Monitoring of parkin-positive cells during FR for 31days in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells. Asterisks indicate the significant difference of the number of cells with parkin foci in irradiated cells as compared with non-irradiated cells. (D) Western blotting for parkin, complex V and PCNA in cytosolic and mitochondrial fraction of 0FR and 31FR cells.

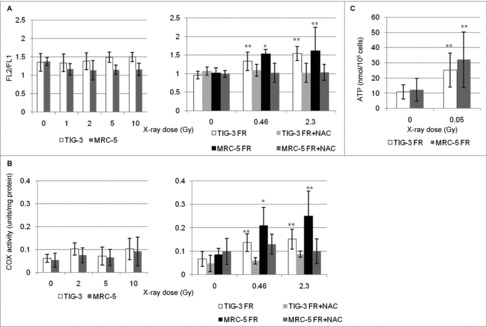

Mitochondrial OXPHOS is enhanced in response to long-term FR in human fibroblasts

We next investigated the effect of IR on mitochondrial OXPHOS in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells. We used the JC-1 probe, a lipophilic cation, to measure mitochondria with low or high ΔΨm, as indicated by formation of JC-1 aggregates and monomers, respectively.23 ΔΨm was shown by the ratio of FL2 detector (JC1-aggregates, orange-red color)/FL1 detector (JC-1 monomers, green color). SR administered at a dose range between 0Gy and 10Gy did not change the ΔΨm or the mitochondrial complex IV (cytochrome c oxidase (COX)) activity in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells (Fig. 2A and 2B, left panel). In contrast, long-term FR elevated the ΔΨm and COX activity in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells as we previously reported in other cell lines, including neural cells (Fig. 2A and 2B, right panels).21 Cells were continuously treated with the antioxidant N-acetyl-cysteine (NAC) at a final concentration of 1 mM during FR. Media was changed at 2- or 3-d intervals. Statistical comparisons revealed that treatment of irradiated cells with NAC prevents changes in mitochondrial membrane potential or COX activity (Fig. 2A and 2B, right panel). We further measured intracellular ATP levels (Fig. 2C). Compared to non-irradiated cells, long-term FR increased ATP levels in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells. These results indicated that ROS are implicated in the activation of OXPHOS after long-term FR in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells.

Figure 2.

Mitochondrial membrane potential and COX activity after IR. (A) FACS results for JC-1 staining after SR or long-term FR in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells. Cells were stained with JC-1 at 24hours after SR or last FR. Asterisks indicate the significant difference of the FL2/FL1 ratio in irradiated cells as compared with that of non-irradiated cells. (B) COX activity at 24hours after SR or last FR in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells. Asterisks indicate the significant difference of the COX activity in irradiated cells as compared with that of non-irradiated cells. (C) ATP levels at 24hours after last FR in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells. Asterisks indicate the significant difference of the amounts of ATP in irradiated cells as compared with that of non-irradiated cells.

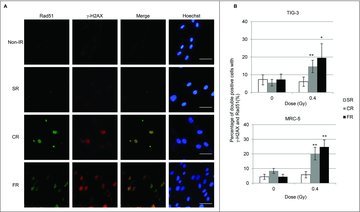

CR or long-term FR prolongs DNA repair

Long-term FR-induced activation of mitochondrial OXPHOS is thought to be associated with the increased energy demands required for DNA DSBs repair.7,21 We investigated focus formation of γ-H2AX, the marker for DSBs, and Rad51, a marker for homologous recombination repair, to identify ongoing DNA repair in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells. CR or FR treatment with 0.4Gy induced prolonged DSB repair as evidenced by γ-H2AX and Rad51 foci formation at 24 hours after IR in irradiated cells (Fig. 3A and 3B). In contrast, no γ-H2AX and RAD51 foci were observed 24 hours following low-dose SR (Fig. 3A and 3B). We previously reported that cells continued to grow exponentially during long-term FR in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells.24 Cell cycle analysis indicated that long-term FR had a negligible effect on IR-induced G2-arrest in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells.21

Figure 3.

γ-H2AX and Rad51 foci formation after IR. (A) Images of γ-H2AX (red) and Rad51 (green) positive cells at 24hours after SR, CR, or FR in MRC-5 cells. DNA was stained with Hoechst. The scale bar represents 50 µm. (B) The percentage of γ-H2AX and Rad51 double-positive cells is shown for each irradiation method in the graph. Asterisks indicate the significant difference of the percentage of double-positive cells in irradiated cells as compared with that of non-irradiated cells.

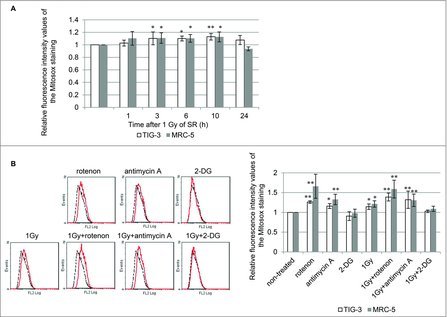

IR-induced mitochondrial ROS

ROS released from mitochondria during OXPHOS may attack mitochondria as oxidative stress in irradiated cells. Mitochondrial O2− was quantified with MitoSOX-Red staining in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells. We previously reported that long-term FR-induced increases in mitochondrial O2− levels in TIG-3 cells.20 Upon 1Gy of SR, O2− levels also increased compared with those of non-irradiated controls and then restored to non-irradiated control levels at 24 hour after 1Gy of SR in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells (Fig. 4A). Mitochondrial respiratory complex I and III have been shown to produce O2−. The role of OXPHOS in IR-induced mitochondrial O2− was examined by using the mitochondrial complex I inhibitor, rotenone, and mitochondrial complex III inhibitor, antimycin A. In addition to SR treatment of 1Gy, treatment with either rotenone or antimycin A led to increased O2− levels in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells compared with non-treated control cells. An increase in mitochondrial ROS levels was also observed when cells were concomitantly treated with IR plus rotenone or antimycin A. We further used 2-deoxy-D-glucose (2-DG), a glucose analog that is unable to be metabolized. 2-DG is phosphorylated by a hexokinase to 2-DG-P, which cannot be further metabolized. Instead, 2-DG-P becomes trapped and accumulates within cells, resulting in inhibition of glucose uptake.25 Treatment with 2-DG alone and 2-DG plus 1Gy did not affect O2− levels in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells.

Figure 4.

ROS generation (A) FACS results for MitoSOX-red staining after 1 Gy of SR in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells at the indicated time. The relative fluorescence intensity values of MitoSOX-red staining normalized to non-irradiated controls are shown. Asterisks indicate the significant difference of the relative fluorescence intensity values of the Mitosox staining in irradiated cells as compared with those of non-irradiated cells. (B) FACS results for MitoSOX-red staining in TIG-3 cells treated with rotenone, antimycin A, 2-DG, 1 Gy of SR, 1 Gy+rotenone, 1 Gy+anitimycin A, and 1 Gy+2-DG. Asterisks indicate the significant difference of the relative fluorescence intensity values of the MitoSOX-red staining in cells treated with the indicated reagents as compared with that of non-irradiated cells.

OXPHOS is associated with IR-induced mitochondrial damage in human fibroblasts

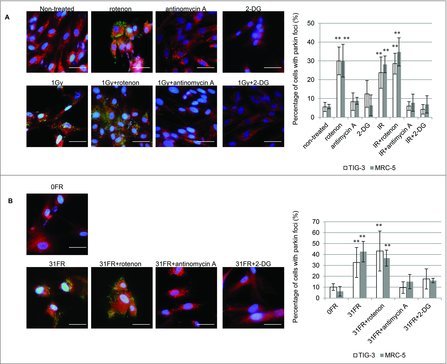

We investigated whether an increase in mitochondrial O2− caused mitochondrial damage in irradiated cells. Parkin focus formation was examined after treatment with rotenone or antimycin A (Fig. 5). As expected, treatment with rotenone alone and rotenone plus SR or long-term FR, induced parkin foci in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells. This phenotype is consistent with an increase in O2− levels after treatment with rotenone as shown in Fig. 4B. In contrast, treatment with antimycin A did not increase the number of cells with parkin foci in spite of elevated O2− levels (Fig. 5A). Mitochondrial oxidative damage was not mediated by antimycin A-induced mitochondrial ROS. Furthermore, antimycin A can eliminate SR- or long-term FR-induced parkin foci in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells (Fig. 5A, 5B). We further indicated that inhibition of glucose metabolism with 2-DG suppressed IR-induced parkin foci in these cells (Fig. 5A, 5B). These results indicate that cellular metabolism contributes to the induction of mitochondrial damage through mitochondrial OXPHOS in response to IR in human fibroblasts.

Figure 5.

The role of mitochondrial OXPHOS on IR-induced mitochondrial damage. (A) Image of parkin staining in untreated TIG-3 (control) cells, cells treated with the indicated reagents and cells exposed to 1 Gy of SR. DNA was stained with Hoechst. The scale bar represents 50 µm. Percentage of parkin-positive TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells is shown on the graph. Asterisks indicate the significant difference of the percentage of cells with parkin foci in cells treated with the indicated reagents as compared with that of non-irradiated cells. (B) Image of parkin staining in untreated TIG-3 (0FR) cells and 31FR cells treated with indicated reagents. Percentage of parkin-positive 31FR cells was shown on the graph. Asterisks indicate the significant difference of the percentage of 31FR cells with parkin foci in cells treated with the indicated reagents as compared with that of non-irradiated cells

Association between nDNA damage and mitochondrial damage

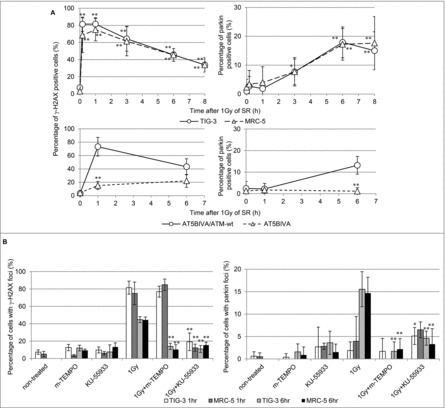

In order to clarify the association between nDNA damage and mitochondrial damage, we investigated the kinetics of focus formation of γ-H2AX and parkin after 1Gy of SR (Fig. 6A). γ-H2AX foci were immediately induced after 1Gy of SR and then disappeared following DNA repair. On the other hand, parkin foci appeared at later time points in parallel with accumulation of mitochondrial ROS following DNA repair of nDNA damage in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells (Fig. 6A, upper panel). Loss of ATM showed defects in IR-induced γ-H2AX and parkin foci in ATM-deficient cells (Fig. 6A, lower panel). We further examined γ-H2AX and parkin staining after treatment with mitochondrial targeted ROS scavenger mito-TEMPO or ATM inhibitor KU-55933. Mito-TEMPO can eliminate IR-induced parkin foci and nDNA damage by regulating mitochondrial ROS generation at 6hours, but not at 1hour after 1Gy of SR in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells (Fig. 6B). This result indicates that initial nuclear DNA damage induced by IR is independent of mitochondrial oxidative damage, whereas mitochondrial oxidative damage is upstream of DNA damage at a later time. KU-55933 abrogated both focus formation of γ-H2AX and parkin after IR in TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells (Fig. 6b). Thus, ATM has a pivotal role in nDNA damage recognition and the damage signal transduction from the nucleus to the mitochondria in irradiated cells.

Figure 6.

nDNA damage and mitochondrial damage (A) The kinetics of focus formation of γ-H2AX or parkin after 1Gy of SR in TIG-3, MRC-5 cells was shown in the upper panel. Asterisks indicate the significant difference the percentage of γ-H2AX or parkin foci in irradiated cells as compared with those of non-irradiated cells. Percentage of AT5BIVA and AT5BIVA/ATM-wt cells with γ-H2AX or parkin foci after 1Gy of SR was shown in the lower panel. Asterisks indicate the significant difference the percentage of γ-H2AX or parkin foci in ATM-deficient cells as compared with those of ATM-wt reconstituted cells. (B) Cells were irradiated with 1Gy following treatment with mito-TEMPO or KU-55933 for two hours and then were stained with γ-H2AX and parkin at 1hour or 6hours after SR. The percentage of cells with γ-H2AX or parkin foci is shown. Asterisks indicate the significant decrease in the percentage of γ-H2AX or parkin positive cells in cells treated with 1Gy plus mito-TEMPO or 1Gy plus KU-55933 as compared with that of 1Gy-irradiated cells at 1 or 6hours after IR.

Discussion

Radiation biology research has focused on the effect of IR-induced DSBs in the cell nucleus and has elucidated DDR mechanisms such as DNA repair, cell cycle checkpoint, and apoptosis in mammalian cells.26 In order to execute DDR, IR stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis and activates mitochondrial OXPHOS for the energy supply to undergo DDR.27-30 The effects of IR on mitochondria are well reviewed in other papers.9, 22 We here demonstrated that long-term FR increased mitochondrial ROS generation in conjunction with enhanced mitochondrial membrane potential or COX activity. We previously reported that antioxidant GSH becomes exhausted after low-dose long-term FR.20 The accumulation of mitochondrial ROS owing to a GSH deficiency inflicts mitochondrial damage which detected by focus formation of parkin in irradiated TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells. In contrast, GSH levels were unchanged and ROS levels were restored to non-irradiated control levels at 24hours after SR in TIG-3 cells.20 Mitochondrial damage was induced when cells were exposed to >1Gy of SR in both TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells without change in GSH levels, mitochondrial membrane potential, and COX activity.

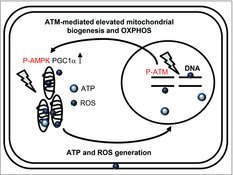

We depicted a schematic model for the role of ATM on mitochondria radiation responses in Fig. 7. ATM is activated by nuclear DNA damage to transmit the damage signals to target molecules. ATM stimulates mitochondrial biogenesis via activation of AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK)31 or induction of the expression of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma coactivator 1α (PGC1α) in response to genotoxic stress.32 These suggests that ATM-regulated damage signaling leads to elevation of mitochondrial biogenesis and OXPHOS in response to the energy requirement for DNA damage responses after IR. ROS are produced in mitochondria as a by-product of ATP production through OXPHOS. ROS levels are increased in ATM-complemented cells, while ROS levels are unaffected by low-dose, long-term FR in ATM-deficient cells.32 Collectively, ATM has an essential role for the crosstalk between the nucleus and mitochondria in irradiated cells.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of the relationship between nuclear and mitochondrial damage responses via ATM signaling pathway.

ATM has been also shown to be associated with induction of mitophagy in response to IR and oxidative stress.33 ATM loss leads to decreased mitophagy, mitochondrial dysfunction, and persistent oxidative stress in ATM-null mice.33 We have previously reported that ATM loss eliminated the effect of radiation on mitochondria such as elevated ΔΨm, increase in ROS levels and focus formation of parkin. Long-term FR resulted in severe mitochondrial damage, as observed through mitochondrial fragmentation in the ATM-deficient cells. This result demonstrated that ATM is essential in the mitochondrial radiation responses in irradiated cells. Consequently, ATM-deficient cells showed highly radiosensitive phenotypes with mitochondria-mediated apoptosis when subjected to low-dose long-term FR.30

Neural stem cells exhibited efficient DNA repair during FR exposure intervals as evident by no γ-H2AX and Rad51 foci and resistance to long-term FR. These cells showed the lack of effects on induction of mitochondrial damage by long-term FR. When neural stem cells were differentiated into neural cells, long-term FR induced persistent Rad51 and γ-H2AX foci accompanied with induction of mitochondrial damage as shown in other differentiated cells (TIG-3 and MRC-5 cells). Thus, it is suggested that sustained nuclear DNA damage is associated with activation of mitochondrial OXPHOS and induction of the mitochondrial damage following exposure to long-term FR. nDNA damage signals are transmitted to the mitochondria and induce mitochondrial oxidative damage via generation of mitochondrial ROS in human cells. ATM is involved in the crosstalk between the nucleus and mitochondria in irradiated cells. On the other hand, inhibition of mitochondrial ROS generation with mito-TEMPO diminished damage to nDNA at a later time in irradiated cells.

Mitochondria are the source of a continuing flux of oxygen radicals. The respiratory chain complex I and complex III are the sites of ROS generation during OXPHOS. We used rotenone and antimycin A to inhibit the electron transfer in complex I and the Q-cycle of enzyme turn over in complex III, respectively. Mitochondrial ROS are the cause of mitochondrial damage, because an effect that can be mitigated by antioxidant. Thus, increased ROS level by exposure to IR and treatment with rotenone induced mitochondrial damage regardless of mitochondrial OXPHOS activity. However, antimycin A did not induce mitochondrial damage despite of increase in ROS levels as others reported previously.17 ROS in complex I are predominantly released to the mitochondrial matrix where mtDNA is located,11,12 while the complex III is associated with release of ROS into both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane.34,35 These results suggested that O2− released from complex I is a major cause of mitochondrial damage in human fibroblasts. ROS levels did not further increase by concomitant treatment with antimycin A with 1Gy of SR compared to when cells were treated with antimycin A alone. This result indicates that antimycin A suppresses IR-induced O2− via perturbation of mitochondrial OXPHOS and therefore can mitigate IR-induced mitochondrial damage.

We have previously reported that long-term FR-induced oxidative damage on mtDNA by measuring amounts of AP site using Nucleostain DNA damage Quantification Kit and amounts of 8-OHdG using high performance liquid chromatography-electrochemical detector (HPLC-ECD).20 mtDNA is more susceptible to oxidative stress than nDNA because a lack of histone protection.11,12 It is well known that insufficient DNA repair system compared to nDNA indicates low DNA repair capacity to mtDNA.36 Oxidative mtDNA lesions lead to abnormal OXPHOS, mitochondrial dysfunction and overproduction of mitochondrial ROS, establishing mitochondrial ROS vicious cycle.7,37-39 A switch from OXPHOS to aerobic glycolysis associated with mitochondrial dysfunction increase tumorigenesis.9,40 Additionally, mitochondrial genomic instability has been shown to correlate with increased risk of vascular disease, neurodegeneration, aging, and carcinogenesis.7,41-43

In conclusion, we demonstrated that nDNA damage caused elevated mitochondrial OXPHOS. This leads to increased mitochondrial ROS as a byproduct of OXPHOS and damages mitochondria in irradiated cells. Mitochondrial dysfunction can be used as markers to assess the long-lasting oxidative stress after IR. We show that antioxidants are useful agents for protection against the mitochondrial damage induced by long-term FR.

Materials and methods

Cell culture conditions and drugs

Normal human diploid lung fibroblasts (MRC-5 and TIG-3) were purchased from the Health Science Research Resources Bank and grown in minimum essential medium (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum. ATM-defective human fibroblasts (AT5BIVA) and ATM-wt reconstituted cells (AT5BIVA/ATM-wt) were obtained from the Radiation Biology Center of Kyoto University.44,45 These cells were transformed with SV-40 and grown in RPMI 1640 medium (Nacalai Tesque, Kyoto, Japan) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal calf serum. Antimycin A, 2-DG, mito-TEMPO, and NAC was purchased from Sigma (San Diego, CA, USA). Rotenon was purchased from Nacalai Tesque. Cells were treated with Antimycin A (10 uM), 2-DG (5 mM), Mito-TEMPO(100 uM), NAC(1 mM) and rotenone(10 uM) for the indicated time.

Irradiation experiments

Cells were irradiated using a 150-kVp X-ray generator (Model MBR-1505R2, Hitachi) with 0.5-mm Cu and 0.1-mm Al filters. Low dose X-ray fractions (0.01Gy or 0.05Gy) were administrated twice a day, 5d/wk. The total doses delivered over 31 d were 0.46Gy and 2.3Gy for cells exposed to FR of 0.01Gy and 0.05Gy, respectively. Cells continued to grow for 31 d following exposure to 0.01Gy or 0.05Gy FR. When cells reached 80% confluency, cells were subcultured in a new flask. For chronic irradiation, cells were irradiated with a 137Cs radiation device (1.11TBq) (Sangyo Kagaku, Osaka, Japan) at different dose rates (0.01Gy or 0.1Gy/d) for 4 d.

Immunofluorescence

Immunofluorescence staining was performed as previously described.24,46 Cells were seeded onto 18 × 18 mm cover slips, placed in 35-mm tissue culture dishes and cultured overnight. Cells on cover slips were fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 10minutes (min) and permeabilized with 0.5% Triton X-100 for 5min. For double staining with MitoTraker deep red (Invitrogen) and parkin, cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde at 37 °C for 15min and permeabilized with 0.2% Triton X-100 for 10 min. Antibodies against γ-H2AX (05-636, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA), parkin (SC-30130, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and Rad51 (ABE257, Millipore, Billerica, MA, USA) and secondary antibodies conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488 (A11034, Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR, USA) or Cy-3 (515-165-062, Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, West Grove, PA, USA) were used. Cells were counterstained for DNA with Hoechst 33258 (4 µg/mL in Vectashield mounting medium; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA, USA). Images were captured using a CCD camera attached to a fluorescence microscope (Keyence). For each data point, > 50 cells were counted from at least three independent samples.

Western blot analyses

Western blotting was performed as described previously.47 Mitochondrial and cytosolic fractionations were collected by using a mitochondrial isolation kit from Thermo Fisher Scientific (Rockford, IL, USA) followed by the manufacturer's instructions. Antibodies against Complex V d-subunit (459000, Invitrogen, Frederick, MD, USA), parkin (SC-30130, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA), and PCNA (sc-56, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA, USA) and secondary antibodies conjugated with HRP (rabbit IgG, NA934, GE Healthcare, Piscataway, NJ, USA and mouse IgG, HAF007, R&D systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) were used. The protein bands were visualized with Chemi-Lumi One L Western blotting substrate (Nacalai Tesque).

Mitochondrial membrane potential

Cells were stained with JC-1 according to the manufacturer's instructions (Invitrogen). The dye can distinguish between mitochondria with low or high membrane potential by formation of JC-1 aggregates and monomers, respectively.23 Cells were incubated in JC-1 for 15min. JC-1 stained cells were quantified with FACScan (Becton Dickinson).

Measurement of cytochrome c oxidase activity

COX activity was measured using a cytochrome c oxidase assay kit (Sigma) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The activity was reported as units/mg of cell extract.

Measurement of ATP in cells

Amounts of ATP were measured using a ATP colorimetric assay kit (Biovision) according to the manufacturer's instructions. The levels were reported as nmol/105 cells.

Mitochondrial ROS measurements

Cells were treated with rotenone, antimycin A or 2-DG for 8hours and were then stained with 5 μM MitoSOX-red (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Lafayette, Colorado, USA.) for 10 min in minimum essential medium without serum. For irradiation experiments, cells were treated with rotenone, antinomycin A or 2-DG for two hours before IR, irradiated with 1Gy and then stained with MitoSOX-red at six hours after SR. MitoSOX-red-stained cells were quantified with FACScan (Becton Dickinson, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA).

Statistical analysis

Error bars represent the standard deviation. All experiments were repeated at least three times using independent samples. Student's t test was used to detect significant differences between non-irradiated and irradiated groups. Dunnett test following one-way ANOVA was used to detect significant differences between the means of three or more independent groups. Double and single asterisks indicate significant differences with p-values of < 0.01 and < 0.05, respectively.

Acknowledgements

Sources of support: This research was supported by a grant from the Japanese Ministry of Education and Science Houga (15K12220, 15K12212), Industrial Disease Clinical Research Grants from the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare and in part by NIFS Collaborative Research Program (NIFS13KOBA028). This work was performed at the Joint Usage/Research Center (Radiation Biology Center), Kyoto University and the Program of the network-type joint Usage/Research Center for Radiation Disaster Medical Science of Hiroshima University, Nagasaki University and Fukushima Medical University.

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

References

- [1].Ciccia A, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: making it safe to play with knives. Mol Cell. 2010;40:179–204. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.09.019. PMID:20965415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Wang X. The expanding role of mitochondria in apoptosis. Genes & development. 2001;15:2922–2933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Somosy Z. Radiation response of cell organelles. Micron. 2000;31:165–181. doi: 10.1016/S0968-4328(99)00083-9. PMID:10588063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Eldridge A, Fan M, Woloschak G, Grdina DJ, Chromy BA, Li JJ. Manganese superoxide dismutase interacts with a large scale of cellular and mitochondrial proteins in low-dose radiation-induced adaptive radioprotection. Free radical biology & medicine. 2012;53:1838–1847. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.08.589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Kim GJ, Fiskum GM, Morgan WF. A role for mitochondrial dysfunction in perpetuating radiation-induced genomic instability. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10377–10383. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-3036. PMID:17079457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Szumiel I. Ionizing radiation-induced oxidative stress, epigenetic changes and genomic instability: the pivotal role of mitochondria. International journal of radiation biology. 2015;91:1–12. doi: 10.3109/09553002.2014.934929. PMID:24937368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Balaban RS, Nemoto S, Finkel T. Mitochondria, oxidants, and aging. Cell. 2005;120:483–495. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.001. PMID:15734681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ernster L, Schatz G. Mitochondria: a historical review. J Cell Biol. 1981;91:227s–255s. doi: 10.1083/jcb.91.3.227s. PMID:7033239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Kam WW, Banati RB. Effects of ionizing radiation on mitochondria. Free radical biology & medicine. 2013;65:607–619. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2013.07.024.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Glutathione Meister A., ascorbate, and cellular protection. Cancer Res. 1994;54:1969s–1975s. PMID:8137322. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Richter C, Park JW, Ames BN. Normal oxidative damage to mitochondrial and nuclear DNA is extensive. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1988;85:6465–6467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.17.6465. PMID:3413108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Yakes FM, Van Houten B. Mitochondrial DNA damage is more extensive and persists longer than nuclear DNA damage in human cells following oxidative stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 1997;94:514–519. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.2.514. PMID:9012815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Chen H, McCaffery JM, Chan DC. Mitochondrial fusion protects against neurodegeneration in the cerebellum. Cell. 2007;130:548–562. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.026. PMID:17693261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Ono T, Isobe K, Nakada K, Hayashi JI. Human cells are protected from mitochondrial dysfunction by complementation of DNA products in fused mitochondria. Nature genetics. 2001;28:272–275. doi: 10.1038/90116. PMID:11431699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Mitophagy Tolkovsky AM. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2009;1793:1508–1515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Kubli DA, Gustafsson AB. Mitochondria and mitophagy: the yin and yang of cell death control. Circulation research. 2012;111:1208–1221. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.112.265819. PMID:23065344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Vives-Bauza C, Zhou C, Huang Y, Cui M, de Vries RL, Kim J, May J, Tocilescu MA, Liu W, Ko HS, Magrane J, Moore DJ, Dawson VL, Grailhe R, Dawson TM, Li C, Tieu K, Przedborski S. PINK1-dependent recruitment of Parkin to mitochondria in mitophagy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2010;107:378–383. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0911187107. PMID:19966284. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Greene JC, Whitworth AJ, Kuo I, Andrews LA, Feany MB, Pallanck LJ. Mitochondrial pathology and apoptotic muscle degeneration in Drosophila parkin mutants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2003;100:4078–4083. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0737556100. PMID:12642658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Narendra D, Tanaka A, Suen DF, Youle RJ. Parkin is recruited selectively to impaired mitochondria and promotes their autophagy. The Journal of cell biology. 2008;183:795–803. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200809125. PMID:19029340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Shimura T, Sasatani M, Kamiya K, Kawai H, Inaba Y, Kunugita N. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species perturb AKT/cyclin D1 cell cycle signaling via oxidative inactivation of PP2A in lowdose irradiated human fibroblasts. Oncotarget. 2016;7:3559–3570. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.6518. PMID:26657292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Shimura T, Sasatani M, Kawai H, Kamiya K, Kobayashi J, Komatsu K, Kunugita N. A comparison of radiation-induced mitochondrial damage between neural progenitor stem cells and differentiated cells. Cell cycle. 2017;16:565–573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Shimura T, Kunugita N. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species-mediated genomic instability in low-dose irradiated human cells through nuclear retention of cyclin D1. Cell cycle. 2016;15:1410–1414. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2016.1170271. PMID:27078622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Perelman A, Wachtel C, Cohen M, Haupt S, Shapiro H, Tzur A. JC-1: alternative excitation wavelengths facilitate mitochondrial membrane potential cytometry. Cell death & disease. 2012;3:e430. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2012.171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Shimura T, Hamada N, Sasatani M, Kamiya K, Kunugita N. Nuclear accumulation of cyclin D1 following long-term fractionated exposures to low-dose ionizing radiation in normal human diploid cells. Cell cycle. 2014;13:1248–1255. doi: 10.4161/cc.28139. PMID:24583467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Woodward GE, Hudson MT. The effect of 2-desoxy-D-glucose on glycolysis and respiration of tumor and normal tissues. Cancer research 1954;14:599–605. PMID:13199805. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Zhou BB, Elledge SJ. The DNA damage response: putting checkpoints in perspective. Nature. 2000;408:433–439. doi: 10.1038/35044005. PMID:11100718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Yu J, Wang Q, Chen N, Sun Y, Wang X, Wu L, Chen S, Yuan H, Xu A, Wang J. Mitochondrial transcription factor A regulated ionizing radiation-induced mitochondrial biogenesis in human lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells. Journal of radiation research. 2013;54:998–1004. doi: 10.1093/jrr/rrt046. PMID:23645454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Kulkarni R, Marples B, Balasubramaniam M, Thomas RA, Tucker JD. Mitochondrial gene expression changes in normal and mitochondrial mutant cells after exposure to ionizing radiation. Radiation research. 2010;173:635–644. doi: 10.1667/RR1737.1. PMID:20426663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Gong B, Chen Q, Almasan A. Ionizing radiation stimulates mitochondrial gene expression and activity. Radiation research 1998;150:505–512. doi: 10.2307/3579866. PMID:9806591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Yamamori T, Yasui H, Yamazumi M, Wada Y, Nakamura Y, Nakamura H, Inanami O. Ionizing radiation induces mitochondrial reactive oxygen species production accompanied by upregulation of mitochondrial electron transport chain function and mitochondrial content under control of the cell cycle checkpoint. Free radical biology & medicine. 2012;53:260–270. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2012.04.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fu X, Wan S, Lyu YL, Liu LF, Qi H. Etoposide induces ATM-dependent mitochondrial biogenesis through AMPK activation. PloS one. 2008;3:e2009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002009. PMID:18431490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Shimura T, Kobayashi J, Komatsu K, Kunugita N. Severe mitochondrial damage associated with low-dose radiation sensitivity in ATM- and NBS1-deficient cells. Cell cycle. 2016;15:1099–1107. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2016.1156276. PMID:26940879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Valentin-Vega YA, Maclean KH, Tait-Mulder J, Milasta S, Steeves M, Dorsey FC, Cleveland JL, Green DR, Kastan MB. Mitochondrial dysfunction in ataxia-telangiectasia. Blood. 2012;119:1490–1500. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-08-373639. PMID:22144182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Kudin AP, Debska-Vielhaber G, Kunz WS. Characterization of superoxide production sites in isolated rat brain and skeletal muscle mitochondria. Biomedicine & pharmacotherapy = Biomedecine & pharmacotherapie. 2005;59:163–168. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2005.03.012.. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Muller FL, Liu Y, Van Remmen H. Complex III releases superoxide to both sides of the inner mitochondrial membrane. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2004;279:49064–49073. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M407715200. PMID:15317809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Kazak L, Reyes A, Holt IJ. Minimizing the damage: repair pathways keep mitochondrial DNA intact. Nature reviews Molecular cell biology. 2012;13:659–671. doi: 10.1038/nrm3439. PMID:22992591. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Zorov DB, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ. Mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) and ROS-induced ROS release. Physiological reviews. 2014;94:909–950. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00026.2013. PMID:24987008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Zorov DB, Juhaszova M, Sollott SJ. Mitochondrial ROS-induced ROS release: an update and review. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2006;1757:509–517. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2006.04.029. PMID:16829228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Zorov DB, Filburn CR, Klotz LO, Zweier JL, Sollott SJ. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release: a new phenomenon accompanying induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. The Journal of experimental medicine. 2000;192:1001–1014. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.7.1001. PMID:11015441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Pavlides S, Whitaker-Menezes D, Castello-Cros R, Flomenberg N, Witkiewicz AK, Frank PG, Casimiro MC, Wang C, Fortina P, Addya S, Pestell RG, Martinez-Outschoorn UE, Sotgia F, Lisanti MP. The reverse Warburg effect: aerobic glycolysis in cancer associated fibroblasts and the tumor stroma. Cell cycle. 2009;8:3984–4001. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.23.10238. PMID:19923890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Yu E, Mercer J, Bennett M. Mitochondria in vascular disease. Cardiovascular research. 2012;95:173–182. doi: 10.1093/cvr/cvs111. PMID:22392270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Kujoth GC, Hiona A, Pugh TD, Someya S, Panzer K, Wohlgemuth SE, Hofer T, Seo AY, Sullivan R, Jobling WA, Morrow JD, Van Remmen H Sedivy JM, Yamasoba T, Tanokura M, Weindruch R, Leeuwenburgh C, Prolla TA. Mitochondrial DNA mutations, oxidative stress, and apoptosis in mammalian aging. Science. 2005;309:481–484. doi: 10.1126/science.1112125. PMID:16020738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Lin MT, Beal MF. Mitochondrial dysfunction and oxidative stress in neurodegenerative diseases. Nature. 2006;443:787–795. doi: 10.1038/nature05292. PMID:17051205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Kobayashi J, Tauchi H, Sakamoto S, Nakamura A, Morishima K, Matsuura S, Kobayashi T, Tamai K, Tanimoto K, Komatsu K. NBS1 localizes to gamma-H2AX foci through interaction with the FHA/BRCT domain. Curr Biol. 2002;12:1846–1851. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(02)01259-9. PMID:12419185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Komatsu K, Matsuura S, Tauchi H, Endo S, Kodama S, Smeets D, Weemaes C, Oshimura M. The gene for Nijmegen breakage syndrome (V2) is not located on chromosome 11. Am J Hum Genet. 1996;58:885–888. PMID:8644753. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Shimura T, Toyoshima M, Adiga SK, Kunoh T, Nagai H, Shimizu N, Inoue M, Niwa O. Suppression of replication fork progression in low-dose-specific p53-dependent S-phase DNA damage checkpoint. Oncogene. 2006;25:5921–5932. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209624. PMID:16682953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Shimura T, Toyoshima M, Adiga SK, Kunoh T, Nagai H, Shimizu N, Inoue M, Niwa O. Suppression of replication fork progression in low-dose-specic p53-dependent S-phase DNA damage checkpoint. Oncogene. 2006;25:5921–5932. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209624. PMID:16682953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]