Abstract

Background and Objectives

Maternal buprenorphine maintenance predisposes the infant to exhibit neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS), but there is insufficient published information regarding the nature of NAS and factors that contribute to its severity in buprenorphine-exposed infants.

Methods

The present study evaluated forty-one infants of buprenorphine-maintained women in comprehensive substance use disorder treatment who participated in an open-label study examining the effects of maternal buprenorphine maintenance on infant outcomes. Modifiers of the infant outcomes, including maternal treatment and substance use disorder parameters, were also evaluated.

Results

Fifty-nine percent of offspring exhibited NAS that required pharmacologic management. Both maternal buprenorphine dose as well as prenatal polysubstance exposure to illicit substance use/licit substance misuse were independently associated with NAS expression. Polysubstance exposure was associated with more severe NAS expression after controlling for the effects of buprenorphine dose. Other exposures, including cigarette smoking and SRI use, were not related to outcomes. Maternal buprenorphine dose was positively associated with lower birth weight and length.

Conclusions

Polysubstance exposure was the most potent predictor of NAS severity in this sample of buprenorphine-exposed neonates. This finding suggests the need for interventions that reduce maternal polysubstance use during medication assisted treatment for opioid use disorder, and highlights the necessity of a comprehensive approach, beyond buprenorphine treatment alone, for the optimal care for pregnant women with opioid use disorders.

Keywords: Buprenorphine, Perinatal substance use disorder treatment, Neonatal abstinence syndrome, Substance exposed neonate, Opioid exposed neonate, Medication assisted treatment during pregnancy, Maternal opioid use disorder

1. Introduction

Gestational illicit opioid use and licit opioid misuse are on the rise in the US, with an attendant increase in the incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome (NAS) among exposed infants (Patrick et al., 2012; Patrick et al., 2015; Ko et al., 2016). Medication assisted treatment of maternal opioid use disorders (OUDs) with either methadone, a full mu-agonist or buprenorphine, a partial mu-agonist/antagonist during gestation is the current standard of care (WHO, 2014). Buprenorphine treatment has become more common (Krans et al., 2016) since the publication of the MOTHER study (Jones et al., 2010), which found that buprenorphine treatment of women with OUDs may confer some advantage to the infant in the form of less severe NAS. NAS requiring pharmacotherapy occurs in 22–67% (Kocherlakota, 2014) among buprenorphine-exposed infants. Substances that may potentiate NAS severity in methadone-exposed infants include polysubstance exposures (Jansson et al., 2012), heavy cigarette smoking (Choo et al., 2004) and psychiatric medication, particularly SRIs (Kaltenbach et al., 2012). It is unknown whether these substances similarly predispose the infant to more severe NAS in buprenorphine-exposed pregnancies, or if other aspects of exposure, such as maternal buprenorphine dose, potentiates NAS in exposed infants.

The purpose of this longitudinal, prospective study is to comprehensively document the outcome of buprenorphine-exposed neonates. Research questions include: 1) the extent to which there is a positive association between maternal buprenorphine dose and NAS severity; 2) whether other maternal factors, including polysubstance use, severity of opioid use, and psychiatric medications potentiate NAS outcomes; and 3) the relation between maternal buprenorphine dose and size at birth. A secondary analysis addressed whether any detected associations between buprenorphine dose and NAS severity is similarly present among women who do and do not use illicit/misuse licit substances during treatment.

2. Participants and Methods

Participants were drawn from a population of pregnant women with OUD entering treatment at the Center for Addiction and Pregnancy (CAP) between 2012 and 2016. CAP is a comprehensive treatment facility for pregnant and parenting women and has been comprehensively described previously (Jansson et al., 1996). Women who opted for buprenorphine (monoproduct only) maintenance as part of a study evaluating fetal and infant outcomes were eligible for enrollment. Eligibility was limited to singleton pregnancies less than 34 weeks of gestation at the time of enrollment, and absence of significant medical/obstetrical comorbidities that could independently affect fetal functioning, such as gestational diabetes, growth restriction, HIV infection, disorders of thyroid functioning and hypertension. Current alcohol use as measured by the Addiction Severity Index (McLellan et al., 1992) at enrollment was exclusionary, as was more than three episodes of alcohol use during treatment. Daily benzodiazepine use at enrollment was also exclusionary due to risk for maternal seizures during inpatient induction (as determined on an individual basis by the overseeing psychiatrist) was exclusionary. Other substance use was not exclusionary, nor was maternal consumption of prescribed psychotropic medications. Participants were required to comply with study procedures, including periodic fetal monitoring, urine toxicology requirements and daily observed buprenorphine dosing at the center; more than 5 consecutive episodes of missed dosing resulted in disenrollment from the protocol. Women provided weekly research urine samples for toxicology screening which were analyzed for illicit substance use/licit substance misuse. The protocol was approved by the overseeing institutional review board and all participants provided informed written consent.

Participants either underwent a 3-day inpatient buprenorphine induction based on the MOTHER study (Jones et al., 2010) or were admitted to the protocol on a stable dose of buprenorphine that was prescribed by another provider prior to pregnancy. Participants in the latter group transferred all obstetric and psychiatric care to CAP program physicians for the duration of the pregnancy. All participants attended intensive outpatient substance use disorder treatment at the center, where they also received obstetric and psychiatric care for co-occurring disorders. Daily buprenorphine dosing was observed through tablet dissolving. Weekly urine samples were analyzed for illicit substance use/licit substance misuse including: amphetamines, barbiturates, buprenorphine, benzodiazepines, cocaine, THC, methamphetamine, methadone, opiates (morphine), and oxycodone (see Table 1 for cut-off values). Infants were delivered at a hospital on the same campus as the treatment center; pediatric care for infants was available at the center.

Table 1.

Maternal treatment and substance exposure characteristics (n=41)

| Maternal characteristic | Mean | St. deviation | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, in years | 27.7 | 4.7 | (21–37) |

| Age at first substance use, in years | 20.2 | 4.8 | (9–31) |

| Age at regular substance use (3x/week or more) in years | 21.4 | 4.7 | (14–32) |

| Years of regular substance use upon treatment entry | 5.8 | 3.6 | (1–16) |

| Gestational age upon treatment entry, in weeks | 21.0 | 7.3 | (5.3–32.5) |

| Length of time in treatment prior to delivery, in days | 131.0 | 55.2 | (44–241) |

| Number of urine toxicology screenings during treatment | 17.8 | 7.8 | (5–33) |

| Number of positive urine toxicology screenings during treatment* | 3.1 | 4.3 | (0–18) |

| Number of urine toxicology screenings positive for opioids** | 0.8 | 1.6 | (0–7) |

| Percent of urine toxicology screenings positive, indicating illicit substance use or licit substance misuse | 18.0 | 26.6 | (0–100) |

| Percent of urine toxicology screenings positive for opioid substance use or misuse | 4.9 | 11.3 | (0–46.7) |

| Buprenorphine*** dose, in mg, at the time of infant delivery | 13.2 | 6.7 | (2–24) |

Indicating illicit substance use or licit substance misuse. Substances screened and cut-off values are: amphetamines 1000 ng/mL; barbiturates 300 ng/mL; buprenorphine 10 ng/mL; benzodiazepines 300 ng/mL; cocaine 300 ng/mL; THC 50 ng/mL; methamphetamine 500 ng/mL; methadone 300 ng/mL; opiates (morphine) 300 ng/mL; oxycodone 100 ng/mL

Includes positive screens for methadone 300 ng/mL, opiates (morphine) 300 ng/mL, and oxycodone 100 ng/mL

monoproduct only

Infants were evaluated for symptoms/signs of NAS using a modified version of the Finnegan scoring system (Jansson et al., 2009) conducted every 3–4 hours, and all were hospitalized for a minimum of 4 days after delivery for observation. Pharmacotherapy for NAS in the hospital of infant birth included oral morphine sulfate with a secondary medication (clonidine, orally) added for infants reaching maximal doses of morphine. All NAS treatment occurred during the inpatient stay; no infants were discharged home on medication. Standard of care for infants after delivery in the hospital of record included rooming in with their mothers.

2.1 Analytic Plan

The primary outcome measure of NAS severity was defined as the total morphine treatment dose, in 0.10 mg increments, administered to infants during hospitalization. Maternal pharmacologic exposure was based on buprenorphine dose (mg); other substances included cigarette use (mean cigarettes per day during treatment) and exposure to illicit substance use/licit substance misuse during treatment, operationalized as the percent of positive urine toxicology tests for any substance during treatment and the percent in which only opioids were detected. A binary variable (0 = none; 1 = > 1) was also created indicating any positive toxicology screen during treatment. Additional maternal variables included maternal age and two measures of opioid use severity: age at first regular opioid use and number of years of regular use.

Negative binomial regression was used to test hypotheses, as it is appropriate for a count distribution (NAS severity, measured in 0.10 mg morphine increments) with many zero values (Allison, 2012), and over-dispersion (conditional variance > conditional mean; Coxe et al., 2009). The relation of maternal buprenorphine dose at delivery and each explanatory risk factor with NAS severity was evaluated in single predictor negative binomial models. Multivariable models assessed the association of buprenorphine dose with NAS severity adjusting for maternal characteristics. To aid with interpretation of model coefficients, continuous control variables were centered at the mean (Aiken and West). In addition, exposure to illicit substance use/licit substance misuse during maternal treatment was tested as a moderator of the relation between maternal buprenorphine dose and NAS severity by entering an interaction term (substance exposure by maternal buprenorphine dose) into negative binomial models. Model fit was assessed using likelihood ratio chi-square, and Akaike (AIC) and Bayesian (BIC) information criteria were used to compare relative fit between models.

The effect of maternal buprenorphine use on birth parameter outcomes (i.e., weight, length and head circumference) was evaluated through linear regression models specified to test buprenorphine dose and other explanatory risk factors in single predictor and adjusted models. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 24 (IBM Corp).

3. Results

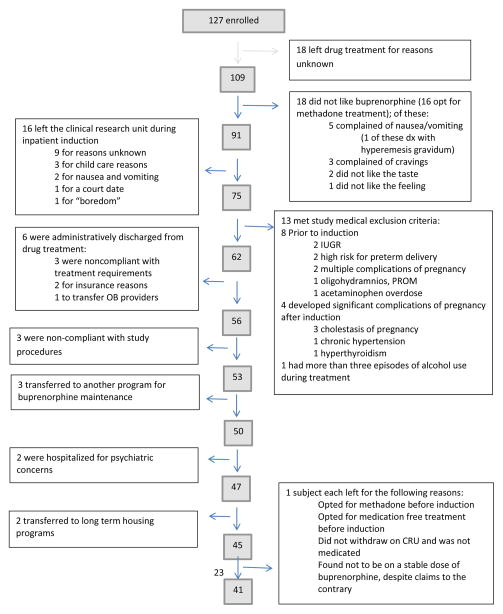

A total of 127 pregnant women provided consent for study participation; 41 completed the protocol through delivery. Participants who left the protocol did so for a variety of reasons (Figure 1). Of the 86 participants who left the protocol for any reason, 42 remained in drug treatment but switched to methadone maintenance and 44 left drug treatment at the center. Data describing fetal neurobehavioral development in the final sample are presented elsewhere (Jansson et al., 2017).

Figure 1.

Study enrollment flowchart

3.1 Maternal Characteristics

Maternal participants (n = 41) were predominantly Caucasian (92.7%), with a mean (SD) age of 26.7 (4.6) years, and 11.4 (2.0) years of education. All were multiparous; participants had on average 2.2 (1.2) prior deliveries at term and 4 women (9.8%) had prior preterm deliveries. Almost all (38, 92.7%) smoked cigarettes, with a mean of 9.7 (6.7) cigarettes smoked per day. Most had at least one psychiatric diagnosis; 25 (61.0%) depression; 6 (14.6%) anxiety, 7 (17.1%) other diagnosis. Seventeen (41.5%) received psychiatric medications during the current pregnancy, all SRIs. Nearly half (n = 18; 43.9%) had no positive urine toxicology results for illicit substance use/licit substance misuse after study enrollment, despite frequent testing (Mean number of urine toxicology testings = 17.8). Maternal substance exposure and drug treatment information is presented in Table 1. Of those with positive toxicology screens, 4 (17.4%) included opioid use only. Maternal urine toxicology screening at delivery was negative for most (38, 92.7%) participants, with 1 positive for THC and 2 for illicit opioid use.

3.2 Infant Birth Parameters

Table 2 presents infant outcomes. All were delivered at full-term (> 36 weeks) and were appropriate weight for gestational age. Gestational age estimation by maternal clinical history was consistent with Ballard Scale (Ballard et al., 1979) scores at delivery. Eight infants (19.5%) required admission to the NICU for respiratory distress determined to be above and beyond that associated with NAS; diagnoses included pneumothorax (1), congenital pneumonia (1) and chorioamnionitis (1); the remaining 5 had respiratory distress of unknown etiology resolving spontaneously. All infants were free from congenital anomalies with one exception. An infant born to a woman treated with buprenorphine from 13 weeks of gestation had 2 different congenital malformations: polydactyly (extra 5th digits) and a congenital heart defect (mild to moderate atrial septal defect); there was a maternal family history for both of these malformations. Twenty five (61.0%) were male.

Table 2.

Infant birth parameters (n=41)

| Infant parameter | Mean | St. deviation | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Birthweight, in grams | 3316.6 | 410.6 | (2375.0–4445.0) |

| Birth length, in cm | 50.8 | 2.3 | (44.5–56.0) |

| Birth head circumference, in cm | 34.4 | 2.3 | (32.0–37.0) |

| Apgar 1 minute | 7.9 | 2.1 | (1–9) |

| Apgar 5 minute | 8.9 | 0.4 | (7–9) |

| Gestational age by dates in weeks | 39.4 | 1.3 | (36.2–41.2) |

Data regarding infant NAS course and severity are presented in Table 3. Consistent with expectations (O’Connor et al., 2011), NAS symptoms peaked on day 3 of life. More than half of the infants (24, 58.5%) required pharmacotherapy for NAS; of these 3 (12.5%) required a second medication to control NAS symptoms. However, the range of medication required to treat NAS was wide (0.6 to 31.7 mg morphine) and distributed over 3 to 41 days. Infant sex was unrelated to NAS severity (B = 0.25, p = .74).

Table 3.

Infant NAS characteristics for infants requiring pharmacotherapy for NAS (n=24)

| Infant NAS characteristic | Mean | St deviation | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| NAS score*, day 1 | 3.9 | 2.1 | (0.3–7.1) |

| NAS score, day 2 | 5.9 | 2.3 | (0.9–11.0) |

| NAS score, day 3 | 5.7 | 2.2 | (1.5–12.1) |

| NAS score, day 4 | 5.7 | 1.9 | (2.5–9.5) |

| Day of highest NAS score | 3.0 | 0.9 | (2.0–4.0) |

| Total opiate (morphine sulfate, PO) given, (mg) | 6.7 | 7.9 | (0.6–31.7) |

| Amount of second medication (clonidine, PO) given (mg) (n=3 infants required second medication) | 0.4 | 0.2 | (0.2–0.6) |

| Length of pharmacological treatment for NAS (days) | 11.8 | 8.9 | (3–41) |

| Total hospitalization (days) | 14.7 | 9.0 | (5–44) |

Modified Finnegan

3.3 Associations Between Buprenorphine Dose and Other Risk Factors on NAS Severity

Negative binomial regression of NAS severity (total morphine required to treat NAS in mg) on buprenorphine dose in a single predictor model indicated a statistically significant relation between maternal buprenorphine dose and NAS severity (incidence rate ratio (IRR) = 1.11, 95%CI [1.01, 1.22], p = 0.03). The IRR indicates that for each 1 mg increase in maternal buprenorphine dose, there was an associated 1.1 multiplicative increase in 0.10 mg increment of opiate prescribed for the pharmacotherapy of NAS. A series of single predictor negative binomial models tested other maternal factors as independent risk factors of NAS severity. Maternal other substance use (i.e., positive toxicology results) during buprenorphine treatment was significantly associated with NAS severity (IRR = 9.8, 95%CI [2.8, 34.0] p < 0.001). However, years of regular opioid use (IRR= 0.99, 95%CI [0.87, 1.12], p = .84), age at first regular opioid use (IRR= 1.09, 95%CI [0.93, 1.24], p = 0.28), average number of cigarettes per day (IRR = 1.07, 95%CI [0.93, 1.24], p = 0.36), and SRI psychiatric medications (IRR= 0.715, 95%CI [0.17, 2.94], p = 0.64) were not associated with NAS severity.

In multivariable models, a test of illicit substance use/licit substance misuse exposure during treatment as a moderator variable was not significant (B = −0.012, p = 0.92), indicating that the effect of buprenorphine dose on NAS severity was equivalent among women who used illicit substances/misused licit substances during treatment and those who did not. Subsequent multivariable models demonstrated that buprenorphine dose was significantly associated with NAS severity (IRR= 1.11, 95%CI [1.00, 1.23], p < 0.05) controlling for years of regular use and maternal age. When maternal illicit substance use/licit substance misuse during prenatal treatment was added to the negative binomial model, maternal buprenorphine dose was non-significant and maternal exposure to substances was significant. Results of this final negative binomial regression model are listed in Table 4. This indicates that infants of mothers who used other substances during treatment required a morphine treatment 9.85 times as high as infants of women who didn’t use other substances during treatment. The model including exposure to substances during prenatal treatment was a better fit to the data than the intercept-only model (Likelihood χ2 = 12.6, df=4, p=0.013), and information criteria values (AIC=314.9; BIC=325.2) indicated better relative fit compared to the model without substance exposure (AIC=320.9; BIC=329.5). The Lagrange multiplier test indicated the negative binomial model was better fit than the Poisson model p=.001).

Table 4.

Negative binomial regression of NAS severity on maternal buprenorphine dose adjusted for maternal risk factors

| Predictor | IRR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buprenorphine dose | 1.09 | [0.98, 1.20] | 0.11 |

| Illicit substance exposure | 0.11 | [0.03, 0.43] | 0.002 |

| Years of regular opioid use | 1.00 | [0.93, 1.30] | 0.26 |

| Maternal age | 1.00 | [0.86, 1.18] | 0.96 |

Notes. IRR= incidence rate ratio; the overdispersion factor parameter estimate was 3.53. Likelihood ratio chi-square test (χ2= 12.62, df=4, p=0.01) indicated good model fit.

These results are confirmed when the measure for maternal illicit substance use/licit substance misuse was replaced by the percentage of positive urine toxicology screens during treatment for any substance. When positive urine screens for opioid substances only was examined the effect on NAS severity neared, but did not attain significance (IRR= 1.06, 95%CI [0.99, .13], p =0 .075).

3.4 Birth Parameter Outcomes

Maternal buprenorphine dose during treatment was significantly associated with decreased infant birth weight (B= −23.8, p = 0.01) and length (B= −.11, p <0.05), but was unrelated to head circumference. Buprenorphine dose remained significant after controlling for the effect of exposure to illicit substance use/licit substance misuse during pregnancy for both birth weight (B = −24.1, p < 0.05) and birth length (B= −0.12, p <0.001). Age at first regular opioid use was also significantly associated with decreased birth weight (B= −35.4, p < 0.01) and length (B= −0.15, p < 0.05). Birth length was also significantly and negatively associated with SRI psychiatric medication exposure (B= −2.18, p<0.001) but birth weight was not (p = 0.28). Birth parameters were unrelated to exposure to illicit substance use/licit substance misuse during treatment. Use of the continuous measures of percent positive urine screens for poly-substances and opioids only, respectively, in sensitivity analyses failed to detected significant associations with birth parameters.

4. Discussion

Treatment of maternal OUD during pregnancy with buprenorphine provides the maternal-infant dyad with major benefits, including more optimal birth weight, lower incidence of birth defects, reduced risk of preterm birth, and reduced NAS severity when compared to methadone (Laslo et al., 2017). However, there is poorly understood variability in the continuum of expression of NAS in buprenorphine-exposed infants, with no single factor or groups of factors that can reliably and accurately predict more severe expression (i.e., the need for pharmacologic treatment for NAS).

In this sample, gestational buprenorphine treatment was associated with NAS that required pharmacotherapeutic treatment in 58.5% of offspring, and maternal buprenorphine dose was an independent predictor of NAS severity over and above mothers’ histories of substance use. Contrary to expectations and findings from methadone treatment studies (Choo et al., 2004; Kaltenbach et al., 2012) neither cigarette use nor SRI medication were associated with NAS severity. However, maternal use of illicit substances or licit substance misuse was significantly associated with NAS severity; this finding persisted after other factors were controlled while buprenorphine dose did not. Given that only 56% of the sample (n = 23) used illicit or misused licit substances (i.e., tested positive at least once for other substances), and a range of substances were detected, more detailed analyses of the role of specific substances on NAS is not possible.

Polysubstance exposure has been associated with increased severity of NAS in infants born to women with OUDs (Jansson et al., 2012; Desai et al., 2015). The relationship between maternal buprenorphine dose and NAS severity has been previously examined with mixed results. Norbuprenorphine, the primary active buprenorphine metabolite, concentrations in infant urine in the first three days of life has been positively correlated with infant length of hospital stay and duration of pharmacotherapy for NAS (Hytinantii et al., 2008). Total meconium concentrations of buprenorphine and buprenorphine:norbuprenorphine ratios have been related to NAS scores > 4, but not to NAS symptomatology requiring pharmacotherapy; however, no relationship between maternal buprenorphine dose at delivery and meconium buprenorphine or norbuprenorphine concentrations was detected (Kacinko et al., 2008). Cord blood concentrations of active metabolites norbuprenorphine and buprenorphine-glucuronide have been positively related with incidence of NAS requiring pharmacotherapy (Shah et al., 2016). However, most previous research has not found a relationship between maternal buprenorphine dose per se and NAS severity as defined by duration/incidence of NAS treatment, peak NAS score or duration of hospital stay (O’Connor et al., 2011; Jones et al., 2014; Bakstad et al., 2009; Metz et al., 2011), although one report suggested a relationship between dose and maximal NAS score that was not significant when the NAS score was above zero (Lejeune et al., 2006). Most of these studies did not consider other substance use (Jones et al., 2014; Lejeune et al., 2006) or considered only limited other substance use (Metz et al., 2011), were retrospective (O’Connor et al., 2011), used self-reported measures of other substance use as opposed to toxicology screens (Bakstad et al., 2009), or had small numbers of participants (O’Connor et al., 2011). None were rigidly controlled prospective series that required maternal adherence to a treatment and research testing protocol, as was the case for this trial.

Higher maternal buprenorphine dose was negatively related to infant birth weight and length and this remained significant after controlling for other illicit/licit misuse of poly-substances. This finding, to our knowledge, has not been previously reported. It is important to note that while this dose relationship did exist, most infants were appropriately grown for gestational age at birth. Although two other reports have not found such an association, this may be due to the limited use of other substances in the populations that comprised those studies (Jones et al., 2014;. O’Connor et al., 2016). Regardless, buprenorphine’s effects on fetal growth remains an open question.

5. Conclusions

In this sample, maternal buprenorphine dose was an independent predictor of NAS severity over and above mothers’ histories of substance use, but antepartum polysubstance exposure was the most potent predictor of more severe NAS expression in buprenorphine-exposed infants. In contrast to methadone treatment, which usually occurs in the context of federally licensed programs requiring patients to return daily for dosing, buprenorphine is increasingly used as an outpatient medication delivered in larger quantities over longer durations (i.e., weekly, monthly) due to a decreased risk of overdose potential for the treatment of OUDs, including in pregnant women (Krans et al., 2016). Benefits of this approach include the elimination of barriers to care for this population which include lack of child care, transportation, or workplace responsibilities. Accordingly, a limitation of this study may be the open label nature of the protocol, which could introduce some bias in the population of women entering treatment who opted for buprenorphine as part of a research study. However, office based treatment that provides only medication for OUDs often does not encompass other aspects of comprehensive care necessary for this population, including obstetric, psychiatric and pediatric care, parenting instruction, psychosocial interventions/case management and close monitoring and intervention for other substance use/misuse. Similarly, the finding that other substance use was a potent predictor of NAS severity lends support for the optimal administration of buprenorphine to pregnant women with OUD in comprehensive treatment settings with strong psychosocial components where maternal other substance use/misuse can be closely monitored and addressed to assure the optimal outcome for the neonate.

The study identified a relationship between higher maternal buprenorphine dose at delivery and lower infant birth weight and length. This finding underscores the need to intensify behavioral health services to address continuing polysubstance use, rather than rely primarily on agonist medication, which only treats OUD. In this sample, at least 16 women transferred to methadone treatment once on buprenorphine due to dissatisfaction with medication, emphasizing the need for maternal medication choice and highlighting to providers that, for buprenorphine-maintained women who continue to report cravings or relapse to opioids, consideration of methadone treatment may be warranted rather than escalating doses of buprenorphine once a therapeutic dose is reached.

Highlights.

Study focused on a sample of buprenorphine-exposed infants

Maternal gestational buprenorphine dose is a positive predictor of NAS severity

Polysubstance exposure most potently predicted NAS severity

Findings underscore the need for comprehensive addictions treatment during pregnancy

Acknowledgments

Role of Funding Source

This study was funded by NIH/NIDA RO1DA031689, Jansson LM (PI)

This study was funded by NIH/NIDA RO1DA031689. Medication for this study was provided by Indivior who had no role in study design; collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The authors thank the study participants and the staff of the Center for Addiction and Pregnancy, without whom this work would not be possible.

Footnotes

Conflict of Interest

Lauren Jansson is a paid consultant for Chiesi, Inc., in which capacity she provides expert guidance regarding pharmacotherapy for neonatal abstinence syndrome. The other authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Contributors

Dr. Jansson conceptualized and designed the study, obtained funding for the research, and drafted the initial manuscript. Dr. Velez assisted the research by being a liaison between the research team and the treatment program, reviewed and revised the manuscript. Ms. McConnell and Ms. Spencer performed data collection for all maternal and infant subjects, were responsible for data abstraction from medical records and data entry and storage. Dr. Jones held the IND for this study, assisted with initial analysis of the data, reviewed and revised the manuscript. Rebeca Rios performed all the analyses for this manuscript, reviewed and revised the manuscript for statistical precision. Drs King, Gandotra and Milio assisted with this research by providing medical oversight for all maternal subjects during their time in the study. They each reviewed the manuscript. Dr. Tuten assisted with regulatory oversight for this study, reviewed and revised the manuscript. Dr. DiPietro assisted with data analysis and interpretation and manuscript preparation. All authors have approved the final manuscript.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; [Google Scholar]

- Allison P. Do we really need zero-inflated models? 2012 Aug 7; http://statisticalhorizons.com/zero-inflated.models/

- Bakstad B, Sarfi M, Welle-Strand GK, Ravndal E. Opioid maintenance treatment during pregnancy: Occurrence and severity of neonatal abstinence syndrome. Eur Addict Res. 2009;15:128–134. doi: 10.1159/000210042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ballard JL, Novak KK, Driver M. A simplified score for assessment of fetal maturation of newly born infants. J Pediatr. 1979;95:769–74. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(79)80734-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo RE, Huestis MA, Schroeder JR, Shin AS, Jones HE. Neonatal abstinence syndrome in methadone-exposed infants is altered by level of prenatal tobacco exposure. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2004;75:253–260. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2004.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coxe S, West SG, Aiken LS. The analysis of count data: A gentle introduction to poisson regression and its alternatives. J Pers Assess. 2009;91:121–136. doi: 10.1080/00223890802634175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Desai RJ, Huybrechts KF, Hernandez-Diaz S, Mogun H, Patorno E, Kaltenbach K, Kerzner LS, Bateman BT. Exposure to prescription opioid analgesics in utero and risk of neonatal abstinence syndrome: Population based cohort study. BMJ. 2015;350:h2102. doi: 10.1136/bmj.h2102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hytinantii T, Kahlia H, Renlund M, Jarvenpaa A, Halmesmako E, Kivitie-Kallio S. Neonatal outcome of 58 infants exposed to maternal buprenorphine in utero. Acta Paediatrica. 2008;97:1040–1044. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.2008.00838.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 24.0. Armonk, NY: IBM Corp; Released 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Jansson LM, Svikis D, Lee J, Paluzzi P, Rutigliano P, Hackerman F. Pregnancy and addiction: A comprehensive care model. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1996;13:321–329. doi: 10.1016/s0740-5472(96)00070-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson LM, Velez M, Harrow C. The opioid-exposed newborn: Assessment and pharmacologic management. J Opioid Manag. 2009;5:47–55. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson LM, Di Pietro JA, Elko A, Williams EL, Milio L, Velez M. Pregnancies exposed to methadone, methadone and other illicit substances, and poly-drugs without methadone: A comparison of fetal neurobehaviors and infant outcomes. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;122:213–219. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jansson LM, Velez M, McConnell K, Spencer N, Tuten M, Jones HE, King VL, Gandotra N, Milio LA, Voegtline K, DiPietro JA. Maternal buprenorphine treatment and fetal neurobehavioral development. AJOG. 2017;216:529.e1–529.e8. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2017.01.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HE, Kaltenbach K, Heil SH, Stine SM, Coyle MG, Arria AM, O’Grady KE, Selby P, Martin PR, Fischer G. Neonatal abstinence syndrome after methadone or buprenorphine exposure. N Engl J Med. 2010;363:2320–2331. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1005359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones HE, Dengler E, Garrison A, O’Grady KE, Seashore C, Horton E, Andringa K, Jansson LM, Thorp J. Neonatal outcomes and their relationship to maternal buprenorphine dose during pregnancy. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2014;134:414–417. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2013.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kacinko SL, Jones HE, Johnson RE, Choo RE, Huestis MA. Correlations of maternal buprenorphine dose, buprenorphine and metabolite concentrations in meconium with neonatal outcomes. Clin Pharmacol. 2008;84:604–612. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2008.156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltenbach K, Holbrook AM, Coyle MG, Heil SH, Salisbury AL, Stine SM, Martin PR, Jones HE. Predicting treatment for neonatal abstinence syndrome in infants born to women maintained on opioid agonist medication. Addiction. 2012;107(Suppl 1):45–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2012.04038.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocherlakota P. Neonatal abstinence syndrome. Pediatrics. 2014;134:e547–561. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-3524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krans EE, Bogen D, Richardson G, Park SY, Dunn SL, Day N. Factors associated with buprenorphine versus methadone use in pregnancy. Subst Abuse. 2016;37:550–557. doi: 10.1080/08897077.2016.1146649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko JY, Patrick SW, Tong VT, Patel R, Lind JN, Barfield WD. Incidence of neonatal abstinence syndrome — 28 states, 1999–2013. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65:799–802. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6531a2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laslo J, Brunner JM, Burns D, Butler E, Cunningham A, Killpack R, Pyeritz C, Rinard K, Childers J, Horzempa J. An overview of available drugs for management of opioid abuse during pregnancy. Mat Health Neonatal Perinatol. 2017;3:4. doi: 10.1186/s40748-017-0044-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lejeune C, Simmat-Durand L, Gourarier L, Aubisson S. Prospective multicenter observational study of 260 infants born to 259 opiate-dependent mothers on methadone or high-dose buprenorphine substitution. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;82:250–57. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLellan A, Kushner H, Metzger D, Peters R, Smith I, Grissom G, Pettinati H, Argeriou M. The fifth edition of the addiction severity index: Historical critique and normative data. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1992;9:199–213. doi: 10.1016/0740-5472(92)90062-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Metz V, Jagsch R, Ebner N, Würzl J, Pribasnig A, Aschauer C, Fischer G. Impact of treatment approach on maternal and neonatal outcome in pregnant opioid-maintained women. Human Psychopharmacol Clin Exp. 2011;26:412–421. doi: 10.1002/hup.1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor A, Alto W, Musgrave K, Gibbons D, Llanto L, Holden S, Karnes J. Observational; study of buprenorphine treatment of opioid-dependent pregnant women in a family medicine residency: Reports on maternal and infant outcomes. J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24:194–201. doi: 10.3122/jabfm.2011.02.100155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor AB, O’Brien L, Alto WA. Maternal buprenorphine dose at delivery and its relationship to neonatal outcomes. Eur Addict Res. 2016;22:127–130. doi: 10.1159/000441220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick SW, Schumacher RE, Benneyworth BD, Krans EE, McAllister JM, Davis MM. Neonatal abstinence syndrome and associated health care expenditures: United States, 2000–2009. J Am Med Assoc. 2012;307:1934–194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick SW, Dudley J, Martin PR, Harrell FE, Warren MD, Hartmann KE, Ely EW, Grijalva CG, Cooper WO. Prescription opioid epidemic and infant outcomes. Pediatrics. 2015;135:842–850. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-3299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah D, Brown S, Hagemeier N, Zheng S, Kyle A, Pryor J, Dankhara N, Singh P. Predictors of neonatal abstinence syndrome in buprenorphine exposed newborn: Can cord blood buprenorphine metabolite levels help? SpringerPlus. 2016;5:854. doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-2576-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Guidelines for the identification and management of substance use and substance use disorders in pregnancy. 2014 http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/107130/1/9789241548731_eng.pdf. [PubMed]