Abstract

The emergence of mucosal healing as a treatment goal that could modify the natural course of Crohn's disease and the accumulating evidence showing that biologics are most effective in achieving mucosal healing, along with the success of early treatment regimens for rheumatoid arthritis, have led to the identification of early Crohn's disease and development of the concept of catching the therapeutic window during the early disease course. Thus, an increasing number of pediatric gastroenterologists are adopting an early biologic treatment strategy with or without an immunomodulator. Although early biologic treatment is effective, cost and overtreatment are issues that limit its early use. Currently, there are insufficient data on who will benefit most from early biologics, as well as on who will not need early or even any biologics. For now, top-down biologics should be considered for patients with currently known high-risk factors of poor outcomes. For other patients, close, objective monitoring and accelerating the step-up process by means of a treat-to-target approach seems the best way to catch the therapeutic window in early pediatric Crohn's disease. The individual benefits of immunomodulator addition during early biologic treatment should be weighed against its risks and decision on early combination treatment should be made after comprehensive discussion with each patient and guardian.

Keywords: Crohn disease, Treat-to-target, Mucosal healing, Top-down, Accelerated step-up, Pediatrics

INTRODUCTION

Crohn's disease (CD) is a chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) that can affect the entire gastrointestinal tract, and it is characterized by periods of clinical remission and relapse [1]. The disease course is usually progressive, and half of affected patients are known to experience complications such as strictures and fistulas, leading to persisting and refractory symptoms, impaired quality of life, and surgery [2,3]. It is known that approximately 25% of CD cases develop during childhood or adolescence, and pediatric CD is more progressive and extensive than CD that occurs in adults [4,5]. Another unique feature of pediatric CD compared with adult-onset CD is linear growth impairment, which is more profound in patients who have undergone a prolonged period of active disease [6]. Therefore, restoring linear growth impairment is an additional goal for pediatric IBD gastroenterologists, which is a much more time-sensitive problem than the challenges presented by adult IBD [7]. In other words, when to start therapy with biologics is a common issue of interest that should be clarified in the treatment of pediatric CD.

The introduction of anti-tumor necrosis factor (anti-TNF) agents such as infliximab (IFX) and adalimumab (ADL), monoclonal antibodies that bind with high specificity and affinity to TNF-alpha (TNF-α), has benefited a large majority of CD patients of all age groups who are refractory to conventional treatments [8,9,10,11,12]. Recent studies in adults have suggested that the early introduction of biologics combined with an immunosuppressant during the disease course may possibly modify the natural history of the disease [13,14]. In accordance, an increasing number of IBD specialists worldwide are adopting an early biologic regimen into real-life clinical practice. Despite the evidence on the efficacy and safety of early biologic treatment in adult patients with moderate-to-severe CD, relevant data are relatively scarce in children and adolescents. This review will focus on the available literature on the efficacy and safety of early biologic treatment in pediatric CD, and how early biologic treatment strategies could be implemented into clinical practice. We will start with looking at why early biologic treatment is important in CD.

SIGNIFICANCE OF EARLY BIOLOGIC TREATMENT IN CD

The traditional goals of treatment in CD were focused on controlling symptoms, enhancing quality of life, minimizing complications to prevent surgery, and additionally restoring growth in pediatric patients [1,4]. However, with accumulating evidence showing that mucosal healing is associated with sustained corticosteroid-free clinical remission, reduced hospitalization, and lower surgery rates, mucosal healing has emerged as a major treatment goal in CD [15,16,17,18]. Among the currently available drugs, biologics are most effective in inducing and maintaining mucosal healing [19]. Thus, their introduction has led to expectations that they may be capable of modifying the natural history of CD [20].

Meanwhile, the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis has significantly progressed during the past two decades as a result of earlier introduction of disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs during the disease course, development of composite measures to better assess disease activity, introduction of biologics, and structured patient management aiming for a treatment target [21]. Likewise, the concept of identifying CD in its early course has been adopted in the management of this disease in order to aggressively halt inflammation and prevent further bowel damage and disability [22]. An international consensus recently defined early CD as a disease with a duration ≤18 months after the diagnosis, and occurring in patients without previous exposure to immunomodulators or biologics [23]. It is now acknowledged that there is a “therapeutic window of opportunity” in early CD, which is when treatment is more effective before bowel damage and disability progress during the natural disease course [24]. Consequently, catching this therapeutic window of opportunity in early CD and achieving deep remission may be the best ways to modify the natural history of CD [25].

EFFICACY OF EARLY BIOLOGIC TREATMENT IN ADULT CD

Early biologic treatment has been shown to be more effective than the conventional step-up approach in several randomized controlled studies in adult CD patients [26,27,28]. In the “top-down vs. step-up” study by D'Haens et al. [26], patients allocated to the early combined immunosuppression group receiving IFX and an immunomodulator showed significantly higher rates of corticosteroid-free clinical remission at both weeks 26 and 52 compared with the conventional step-up group (week 26: 60.0% vs. 35.9%, p=0.006; week 52: 61.5% vs. 42.2%, p=0.03). Furthermore, patients in the early combined immunosuppression group were more likely to reveal no ulcers on endoscopy at 2 years (73.1% vs. 30.4%, p=0.003). Further prospective investigation of a subset of patients from this study revealed that achievement of complete mucosal healing at 2 years was associated with higher rates of corticosteroid-free clinical remission and lower rates of hospitalization and surgery during 3 and 4 years after treatment initiation [18].

In the SONIC trial, combination therapy with IFX and azathioprine was superior to IFX monotherapy (56.8% vs. 44.4%, p=0.02) and azathioprine monotherapy (56.8% vs. 30.0%, p<0.001) in inducing corticosteroid-free remission at week 26 [27]. This superiority was also observed in terms of mucosal healing at week 26 (43.9% vs. 30.1%, p=0.06; 43.9% vs. 16.5%, p<0.001, respectively). Notably, IFX monotherapy was also superior to azathioprine monotherapy in inducing these two outcomes at week 26 (44.4% vs. 30.0%, p=0.006; 30.1% vs. 16.5%, p=0.02, respectively), indicating the superiority of early biologics over conventional treatment. Recently, the REACT study reported that major adverse outcomes, defined as the occurrence of surgery, hospital admission, or serious disease-related complications over a 2-year period, were significantly lower in patients who had received early combined immunosuppression with ADL and an immunomodulator than in those who had received conventional treatment (27.7% vs. 35.1%; hazard ratio, 0.73; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.62–0.86; p=0.0003) [28].

Furthermore, studies in adult CD patients have also demonstrated that the efficacy was higher when anti-TNF treatment was introduced earlier in the disease course [29,30]. A recent post-hoc analysis of the SONIC trial revealed higher mucosal healing rates in early CD patients compared with their counterparts, among a subgroup of patients receiving combination therapy with IFX and azathioprine [29]. Another recent post-hoc analysis of the EXTEND study reported higher 1-year deep remission rates in patients whose disease duration were shorter (33%, 20%, and 16% in disease durations of ≤2, >2–5, and >5 years, respectively) in CD patients who had received scheduled ADL treatment [30].

EFFICACY OF EARLY BIOLOGIC TREATMENT IN PEDIATRIC CD

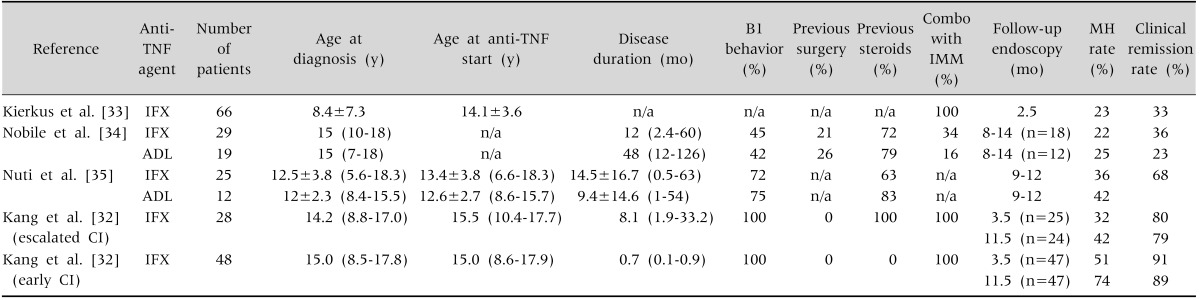

Despite the currently limited relevant evidence in pediatric CD patients, the available literature suggests that early IFX treatment is also more effective when administered earlier in the disease course [31,32]. According to a recent retrospective study with propensity score analysis, early anti-TNF-α monotherapy initiated within 3 months of diagnosis was associated with significantly improved clinical outcomes, with an estimated 25% absolute improvement compared with early immunomodulator monotherapy [31]. This superiority was also demonstrated in terms of mucosal healing in our recently published study in moderate-to-severe luminal pediatric CD patients, which revealed that mucosal healing rates at week 54 from baseline IFX were significantly higher in patients who were treated with an early combined immunosuppression strategy initiated within 1 month from diagnosis than in those who were stepped up to receive combined immunosuppression (74% vs. 42%, p=0.007) [32]. Concerning mucosal healing, studies on pediatric CD patients receiving treatment with anti-TNF agents have shown variable mucosal healing rates of 22–42% at 3 months to 1 year after treatment initiation [33,34,35]. Factors such as disease duration, previous bowel surgery, proportion of patients with inflammatory disease behavior, and proportion of patients receiving combination treatment with an immunomodulator may have affected this difference in achieving mucosal healing (Table 1) [32,33,34,35]. Although it is yet unclear what mechanism is responsible for this discrepancy in efficacy according to the difference in the timing of anti-TNF initiation, factors such as differences in inflammatory burden and cytokine profiles between the two stages of disease may play a role [3,36,37].

Table 1. Studies on Mucosal Healing in Pediatric Crohn's Disease Patients Treated with Biologics.

Values are presented as number only, mean±standard deviation, mean±standard deviation (range), or median (range).

Anti-TNF: anti-tumor necrosis factor, IMM: immunomodulatory, MH: mucosal healing, IFX: infliximab, n/a: not available, ADL: adalimumab, CI: combined immunosuppression.

Restoration of linear growth impairment is an additional goal in the treatment of CD among children and adolescents [7]. The effectiveness of anti-TNF agents in improving linear growth in pediatric CD has been reported in several studies [38,39,40]. Although there are limited data about the effect of early anti-TNF treatment on long-term growth restoration, the aforementioned study by Walters et al demonstrated a significant improvement in height in the early anti-TNF group, whereas height was not restored in the early immunomodulator group and in those who had received neither drug (mean Δ-height +0.14 vs. −0.02 vs. −0.06, p=0.039) [31]. Recently, we have found that early combined immunosuppression was superior to step-up therapy in improving long-term height z-scores at 3 years after adjusting for sex, age at diagnosis, and Tanner stage at diagnosis [41]. This difference was also significant in a subgroup of patients with Tanner stage 1–2, suggesting that biologics should be considered upfront at diagnosis in pediatric CD patients, especially in those with remaining growth potential.

Although there are limited data on the effect of early biologics on long-term outcomes, we have previously demonstrated that the relapse-free rates at 3 years from IFX initiation was significantly higher in the top-down combination group than in the step-up combination group, although the proportion of patients who had stopped IFX at 1 year was significantly higher in the top-down group [42]. A recent prospective cohort study from Belgium concluded that anti-TNF therapy and accelerated step-up therapy in older patients with more severe disease leads to beneficial long-term outcomes [43]. Another recent large-scale multicenter study that derived and validated a risk-stratification model based on clinical and serological factors at diagnosis concluded that early biologic usage was associated with the reduction of intestinal penetrating complications, and that a novel ileal extracellular matrix gene signature was associated with future stricturing complications [44].

SAFETY OF EARLY BIOLOGIC TREATMENT IN PEDIATRIC CD

The occurrence of fatal hepatosplenic T-cell lymphomas (HSTCLs) during combination therapy with thiopurines has posed a major fear among pediatric gastroenterologists. It has been reported that HSTCLs tend to occur predominantly in male patients, in 50% of patients aged <20 years, and in patients who had been treated with long-term thiopurines either alone or combination with anti-TNF agents [45,46]. Previous studies have shown that the risk of developing any lymphoma is increased in IBD patients, both those receiving thiopurine monotherapy and those receiving combination therapy with an anti-TNF agent [47,48,49]. Furthermore, a recent systematic analysis reported that among pediatric IBD patients, the risk for developing lymphoma was not higher in patients who received only anti-TNF therapy than in those treated with other drugs [50]. However, there are currently limited long-term data on the safety of early biologic treatment compared with conventional step-up biologic treatment in children.

According to a recent large long-term prospective cohort study that utilized data from the DEVELOP registry in 5,766 pediatric IBD patients with 24,543.0 patient-years of follow-up, IFX monotherapy was not associated with an increased risk of malignancy, whereas a trend toward an increased risk of malignancy was observed in thiopurine-exposed patients, irrespective of biologic exposure [51]. In this study, standardized incidence ratios (SIRs) did not demonstrate an increased risk of malignancy among patients exposed to IFX (SIR, 1.69; 95% CI, 0.46–4.32) compared with patients not exposed to a biologic agent (SIR, 2.17; 95% CI, 0.59–5.56), even when patients were stratified according to thiopurine exposure. Moreover, compared with the SIR for patients with ongoing thiopurine exposure or discontinuation of therapy within 1 year of a malignancy diagnosis (SIR, 4.45; 95% CI, 1.92–8.77), the SIR for those who discontinued thiopurine therapy for ≥1 years before a malignancy diagnosis (SIR, 1.48; 95% CI, 0.30–4.32) was similar to the SIR for the thiopurine non-exposed group (SIR, 1.30; 95% CI, 0.16–4.71), suggesting that discontinuation of thiopurines for ≥1 year may reduce the malignancy risk (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer). Moreover, they demonstrated that thiopurine exposure was also an important precedent event for the development of malignancy or hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in pediatric patients with IBD, based on the observation of five cases of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis development among patients who had received only thiopurines.

Concerning combination therapy in pediatric CD patients, the current consensus guideline of the European Crohn's and Colitis Organization (ECCO) and the European Society for Pediatric Gastroenterology, Hepatology, and Nutrition (ESPGHAN) on the medical management of pediatric CD states that concomitant azathioprine may be used during the first 6 months of treatment with IFX, mostly extrapolating data from adult studies [46]. After 6 months, stopping azathioprine should be considered especially in boys, whereas the decision should be individualized by weighing the benefits and risks. In this manner, the use of low-dose methotrexate may be an alternative to azathioprine in combination therapy [52]. Although no significance was observed in clinical outcomes between adult CD patients who received IFX and methotrexate for combination treatment and those who received IFX only in the COMMIT trial, combination treatment resulted in significantly higher IFX trough levels and lower anti-drug antibodies to IFX [53]. Further studies are required on whether methotrexate could act as an effective and safe concomitant medication during treatment with biologics. Concerning the risk for developing opportunistic infections, several studies have demonstrated that anti-TNF agents, immunomodulators, and corticosteroids each pose a risk, and the risk is increased when these agents are combined [54,55,56]. Until more evidence is available, a personalized strategy weighing the benefits and risks based on each patient's disease phenotype and activity seems the best answer for combined immunosuppression.

WHO SHOULD RECEIVE EARLY BIOLOGIC TREATMENT IN PEDIATRIC CD?

Risk stratification at diagnosis is crucial in CD in order to avoid undertreatment of patients with a poor prognosis and overtreatment of patients with a favorable prognosis [57]. According to the consensus guideline of ECCO/ESPGHAN on the medical management of pediatric CD, high-risk factors for poor outcomes are defined as deep colonic ulcerations on endoscopy, persistent severe disease despite adequate induction therapy, extensive disease, marked growth retardation, severe osteoporosis, stricturing and penetrating disease at onset, and severe perianal disease [46]. Adult studies have previously demonstrated that age at diagnosis <40 years, complicating disease with intestinal strictures or fistulas, extensive intestinal involvement, perianal disease, and smoking are risk factors for a complicated or disabling disease course [58,59,60,61,62,63]. Serologic markers, such as antibodies to Saccharomyces cerevisiae, CD-related bacterial sequence I2, Escherichia coli outer membrane porin C, and CBir1 flagellin and genetic factors, such as NOD2, IL23R, JAK2, TNFS15, and PRDM1, have been shown to be associated with a complicated disease course [64,65,66].

In an attempt to facilitate individualized risk stratification, a recent study developed a predictive model using system dynamic analysis of prospective clinical and serologic data of 796 patients [67]. In this study, among patients possessing the highest risk for developing complications, corticosteroid use hastened the time to complication, whereas anti-TNF-α use within 3 months reduced the absolute risk of complications by 75%, and immunomodulators reduced the risk by approximately 25%. However, a significant risk reduction advantage of biologics over immunomodulators was not observed in patients with a low risk for complications. It is noteworthy that not all patients may require a biologic to alter their natural history of CD [68]. Future randomized clinical trials investigating the benefit and risk of current therapies including biologics by stratifying patients according to the presence or absence of individual risk factors for a complicated or disabling disease course may answer the question of who will most benefit from early biologic treatment, as well as the question of who will not need early or even any biologics.

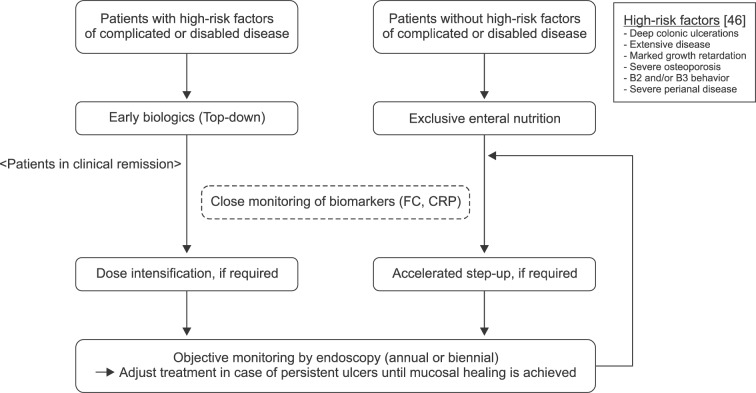

Until these questions are answered, it seems that early top-down biologics should be considered for those with currently known high-risk factors for poor outcomes in accordance with the ECCO/ESPGHAN guideline on the medical management of pediatric CD [46]. For those without high-risk factors, exclusive enteral nutrition should be the primary choice of treatment if tolerable, also in accordance with the ECCO/ESPGHAN guideline.

The treatment protocol for pediatric CD in the current ECCO/ESPGHAN guideline is primarily based on a step-up strategy in which treatment is escalated when symptoms persist. Although the treatment protocol is swift in stepping-up treatment in patients with persisting symptoms, patients in clinical remission induced by a certain therapeutic agent are likely to maintain their current treatment until symptoms relapse in the future. For example, some patients may stay clinically well for a certain period with no symptoms after induction of exclusive enteral nutrition and maintenance with immunomodulators. Despite the absence of symptoms, mucosal inflammation and ulcers may persist in some patients and, consequently, bowel damage may gradually progress. Therefore, a conventional step-up strategy based on clinical symptoms is not enough to catch the therapeutic window of opportunity, and a treat-to-target strategy is definitely required, especially in patients who do not possess high-risk factors for a disabling course at diagnosis and are in clinical remission. The main principles of the treat-to-target strategy are based on regularly assessing disease activity by using validated outcome measures and subsequently adjusting treatment when inflammatory disease activity persists, which is based on a protocol in which treatment consequences and targets are specified in advance [57]. Thus, making the initial treatment decision according to risk stratification and close objective monitoring, and hastening the step-up process by using a treat-to-target strategy seem the best ways to catch the therapeutic window in early pediatric CD.

Meanwhile, objective monitoring may be rather difficult to perform in the pediatric population when mucosal healing is the target and when endoscopic evaluation is recommended at 6–9 months from diagnosis [69]. Although biomarker remission, such as normalization of C-reactive protein (CRP) and fecal calprotectin (FC), is recommended as an adjunctive target in adults [69], it should be considered an alternative target of endoscopic remission in children, on account of the infeasibility of frequent and repetitive ileocolonoscopy in this age group (Fig. 1) [46]. This is supported by a recent study proposing a composite of normalized Pediatric Crohn's Disease Activity Index, CRP, and FC <500 µg/g as the noninvasive end point for treatment response in pediatric CD [70]. Future studies on novel biomarkers or composite scores to better predict mucosal healing could possibly substitute short-term endoscopic evaluation between regular annual or biennial examinations.

Fig. 1. Application of early biologic treatment strategies into current guidelines based on a treat-to-target methodology. FC: fecal calprotectin, CRP: C-reactive protein.

CONCLUSION

Early biologic treatment is effective for pediatric CD patients. However, this does not mean that all pediatric CD patients should start biologics upfront from diagnosis, as not all patients will require biologics during their disease course. Early biologics should be considered in patients possessing potential risks for developing a progressive and disabling disease course. For the rest, a treat-to-target approach by means of close objective monitoring and accelerating the step-up process seems to be the best way to catch the therapeutic window in early pediatric CD. Considering the infeasibility of repetitive and frequent endoscopic examinations in children, biomarker remission, including normalization of FC and CRP, should be considered an alternative target of endoscopic remission. Studies stratifying patients into those who will benefit most and those who will benefit least from early treatment with biologics are required in the future. Concerning early combination therapy, individualized treatment based on the benefits and risks in each patient is more crucial, considering the increased risk of malignancy and serious infections associated with thiopurine use. Most importantly, a thorough explanation of the pros and cons of each treatment and treatment strategy should be provided to each patient and guardian, and the final decision should be based on full consensus.

References

- 1.Baumgart DC, Sandborn WJ. Inflammatory bowel disease: clinical aspects and established and evolving therapies. Lancet. 2007;369:1641–1657. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60751-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cosnes J, Cattan S, Blain A, Beaugerie L, Carbonnel F, Parc R, et al. Long-term evolution of disease behavior of Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2002;8:244–250. doi: 10.1097/00054725-200207000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thia KT, Sandborn WJ, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Loftus EV., Jr Risk factors associated with progression to intestinal complications of Crohn's disease in a population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2010;139:1147–1155. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.06.070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosen MJ, Dhawan A, Saeed SA. Inflammatory bowel disease in children and adolescents. JAMA Pediatr. 2015;169:1053–1060. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim S. Surgery in pediatric crohn's disease: indications, timing and post-operative management. Pediatr Gastroenterol Hepatol Nutr. 2017;20:14–21. doi: 10.5223/pghn.2017.20.1.14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Walters TD, Griffiths AM. Mechanisms of growth impairment in pediatric Crohn's disease. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;6:513–523. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2009.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Walters TD, Hyams JS. Can early anti-TNF-α treatment be an effective therapeutic strategy in children with Crohn's disease? Immunotherapy. 2014;6:799–802. doi: 10.2217/imt.14.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanauer SB, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, et al. Maintenance infliximab for Crohn's disease: the ACCENT I randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;359:1541–1549. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08512-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sands BE, Blank MA, Patel K, van Deventer SJ ACCENT II Study. Long-term treatment of rectovaginal fistulas in Crohn's disease: response to infliximab in the ACCENT II Study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:912–920. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00414-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hyams J, Crandall W, Kugathasan S, Griffiths A, Olson A, Johanns J, et al. Induction and maintenance infliximab therapy for the treatment of moderate-to-severe Crohn's disease in children. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:863–873. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Rutgeerts P, Enns R, Hanauer SB, Panaccione R, et al. Adalimumab for maintenance of clinical response and remission in patients with Crohn's disease: the CHARM trial. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:52–65. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hyams JS, Griffiths A, Markowitz J, Baldassano RN, Faubion WA, Jr, Colletti RB, et al. Safety and efficacy of adalimumab for moderate to severe Crohn's disease in children. Gastroenterology. 2012;143:365–74.e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2012.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ordás I, Feagan BG, Sandborn WJ. Early use of immunosuppressives or TNF antagonists for the treatment of Crohn's disease: time for a change. Gut. 2011;60:1754–1763. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antunes O, Filippi J, Hébuterne X, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Treatment algorithms in Crohn's - up, down or something else? Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2014;28:473–483. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2014.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Neurath MF, Travis SP. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel diseases: a systematic review. Gut. 2012;61:1619–1635. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-302830. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rutgeerts P, Feagan BG, Lichtenstein GR, Mayer LF, Schreiber S, Colombel JF, et al. Comparison of scheduled and episodic treatment strategies of infliximab in Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2004;126:402–413. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2003.11.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Frøslie KF, Jahnsen J, Moum BA, Vatn MH IBSEN Group. Mucosal healing in inflammatory bowel disease: results from a Norwegian population-based cohort. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:412–422. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baert F, Moortgat L, Van Assche G, Caenepeel P, Vergauwe P, De Vos M, et al. Mucosal healing predicts sustained clinical remission in patients with early-stage Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:463–468. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.09.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.De Cruz P, Kamm MA, Prideaux L, Allen PB, Moore G. Mucosal healing in Crohn's disease: a systematic review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2013;19:429–444. doi: 10.1002/ibd.22977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Frolkis AD, Dykeman J, Negrón ME, Debruyn J, Jette N, Fiest KM, et al. Risk of surgery for inflammatory bowel diseases has decreased over time: a systematic review and meta-analysis of population-based studies. Gastroenterology. 2013;145:996–1006. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.07.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Breedveld FC, Boumpas D, Burmester G, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis. 2010;69:631–637. doi: 10.1136/ard.2009.123919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Allen PB, Gower-Rousseau C, Danese S, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Preventing disability in inflammatory bowel disease. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2017;10:865–876. doi: 10.1177/1756283X17732720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Billioud V, D'Haens G, Panaccione R, Feagan B, Panés J, et al. Development of the Paris definition of early Crohn's disease for disease-modification trials: results of an international expert opinion process. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012;107:1770–1776. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2012.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pariente B, Cosnes J, Danese S, Sandborn WJ, Lewin M, Fletcher JG, et al. Development of the Crohn's disease digestive damage score, the Lémann score. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:1415–1422. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Danese S, Fiorino G, Fernandes C, Peyrin-Biroulet L. Catching the therapeutic window of opportunity in early Crohn's disease. Curr Drug Targets. 2014;15:1056–1063. doi: 10.2174/1389450115666140908125738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.D'Haens G, Baert F, van Assche G, Caenepeel P, Vergauwe P, Tuynman H, et al. Early combined immunosuppression or conventional management in patients with newly diagnosed Crohn's disease: an open randomised trial. Lancet. 2008;371:660–667. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60304-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Colombel JF, Sandborn WJ, Reinisch W, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Rachmilewitz D, et al. Infliximab, azathioprine, or combination therapy for Crohn's disease. N Engl J Med. 2010;362:1383–1395. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0904492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khanna R, Bressler B, Levesque BG, Zou G, Stitt LW, Greenberg GR, et al. Early combined immunosuppression for the management of Crohn's disease (REACT): a cluster randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:1825–1834. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00068-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Colombel JF, Reinisch W, Mantzaris GJ, Kornbluth A, Rutgeerts P, Tang KL, et al. Randomised clinical trial: deep remission in biologic and immunomodulator naïve patients with Crohn's disease-a SONIC post hoc analysis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2015;41:734–746. doi: 10.1111/apt.13139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Colombel JF, Rutgeerts PJ, Sandborn WJ, Yang M, Camez A, Pollack PF, et al. Adalimumab induces deep remission in patients with Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:414–422.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Walters TD, Kim MO, Denson LA, Griffiths AM, Dubinsky M, Markowitz J, et al. Increased effectiveness of early therapy with anti-tumor necrosis factor-α vs an immunomodulator in children with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:383–391. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kang B, Choi SY, Kim HS, Kim K, Lee YM, Choe YH. Mucosal healing in paediatric patients with moderate-to-severe luminal crohn's disease under combined immunosuppression: escalation versus early treatment. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:1279–1286. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjw086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kierkus J, Dadalski M, Szymanska E, Oracz G, Wegner A, Gorczewska M, et al. The impact of infliximab induction therapy on mucosal healing and clinical remission in Polish pediatric patients with moderateto-severe Crohn's disease. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;24:495–500. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e32835159f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nobile S, Gionchetti P, Rizzello F, Calabrese C, Campieri M. Mucosal healing in pediatric Crohn's disease after anti-TNF therapy: a long-term experience at a single center. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;26:458–465. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0000000000000045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nuti F, Civitelli F, Bloise S, Oliva S, Aloi M, Latorre G, et al. Prospective evaluation of the achievement of mucosal healing with anti-TNF-α therapy in a paediatric Crohn's disease cohort. J Crohns Colitis. 2016;10:5–12. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjv126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Desreumaux P, Brandt E, Gambiez L, Emilie D, Geboes K, Klein O, et al. Distinct cytokine patterns in early and chronic ileal lesions of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:118–126. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70116-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kugathasan S, Saubermann LJ, Smith L, Kou D, Itoh J, Binion DG, et al. Mucosal T-cell immunoregulation varies in early and late inflammatory bowel disease. Gut. 2007;56:1696–1705. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.116467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Borrelli O, Bascietto C, Viola F, Bueno de Mesquita M, Barbato M, et al. Infliximab heals intestinal inflammatory lesions and restores growth in children with Crohn's disease. Dig Liver Dis. 2004;36:342–347. doi: 10.1016/j.dld.2003.12.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Crombé V, Salleron J, Savoye G, Dupas JL, Vernier-Massouille G, Lerebours E, et al. Long-term outcome of treatment with infliximab in pediatric-onset Crohn's disease: a population-based study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:2144–2152. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Church PC, Guan J, Walters TD, Frost K, Assa A, Muise AM, et al. Infliximab maintains durable response and facilitates catch-up growth in luminal pediatric Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2014;20:1177–1186. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Choi J, Kang B, Kim MJ, Sohn I, Lee HJ, Choe YH. Early infliximab yields superior long-term effects on linear growth in pediatric Crohn's disease patients. Gut Liver. 2018 doi: 10.5009/gnl17290. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lee YM, Kang B, Lee Y, Kim MJ, Choe YH. Infliximab “Top-Down” strategy is superior to “Step-Up” in maintaining long-term remission in the treatment of pediatric crohn disease. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;60:737–743. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000000711. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wauters L, Smets F, De Greef E, Bontems P, Hoffman I, Hauser B, et al. Long-term outcomes with anti-TNF therapy and accelerated step-up in the prospective pediatric belgian crohn's disease registry (BELCRO) Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2017;23:1584–1591. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000001193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kugathasan S, Denson LA, Walters TD, Kim MO, Marigorta UM, Schirmer M, et al. Prediction of complicated disease course for children newly diagnosed with Crohn's disease: a multicentre inception cohort study. Lancet. 2017;389:1710–1718. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30317-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kotlyar DS, Osterman MT, Diamond RH, Porter D, Blonski WC, Wasik M, et al. A systematic review of factors that contribute to hepatosplenic T-cell lymphoma in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2011;9:36–41.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2010.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ruemmele FM, Veres G, Kolho KL, Griffiths A, Levine A, Escher JC, et al. Consensus guidelines of ECCO/ESPGHAN on the medical management of pediatric Crohn's disease. J Crohns Colitis. 2014;8:1179–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2014.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kopylov U, Vutcovici M, Kezouh A, Seidman E, Bitton A, Afif W. Risk of lymphoma, colorectal and skin cancer in patients with IBD treated with immunomodulators and biologics: a quebec claims database study. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1847–1853. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kandiel A, Fraser AG, Korelitz BI, Brensinger C, Lewis JD. Increased risk of lymphoma among inflammatory bowel disease patients treated with azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine. Gut. 2005;54:1121–1125. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.049460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Siegel CA, Marden SM, Persing SM, Larson RJ, Sands BE. Risk of lymphoma associated with combination anti-tumor necrosis factor and immunomodulator therapy for the treatment of Crohn's disease: a metaanalysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2009;7:874–881. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2009.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Dulai PS, Thompson KD, Blunt HB, Dubinsky MC, Siegel CA. Risks of serious infection or lymphoma with anti-tumor necrosis factor therapy for pediatric inflammatory bowel disease: a systematic review. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2014;12:1443–1451. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2014.01.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hyams JS, Dubinsky MC, Baldassano RN, Colletti RB, Cucchiara S, Escher J, et al. Infliximab is not associated with increased risk of malignancy or hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis in pediatric patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2017;152:1901–1914.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2017.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cozijnsen MA, Escher JC, Griffiths A, Turner D, de Ridder L. Benefits and risks of combining anti-tumor necrosis factor with immunomodulator therapy in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:951–961. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Feagan BG, McDonald JW, Panaccione R, Enns RA, Bernstein CN, Ponich TP, et al. Methotrexate in combination with infliximab is no more effective than infliximab alone in patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2014;146:681–688.e1. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2013.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Toruner M, Loftus EV, Jr, Harmsen WS, Zinsmeister AR, Orenstein R, Sandborn WJ, et al. Risk factors for opportunistic infections in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Gastroenterology. 2008;134:929–936. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Marehbian J, Arrighi HM, Hass S, Tian H, Sandborn WJ. Adverse events associated with common therapy regimens for moderate-to-severe Crohn's disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:2524–2533. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2009.322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Day AS, Gulati AS, Patel N, Boyle B, Park KT, Saeed SA. The role of combination therapy in pediatric inflammatory bowel disease (IBD): a clinical report from the North American Society for pediatric gastroenterology, hepatology and nutrition. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2017 doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001850. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bouguen G, Levesque BG, Feagan BG, Kavanaugh A, Peyrin-Biroulet L, Colombel JF, et al. Treat to target: a proposed new paradigm for the management of Crohn's disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13:1042–1050.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2013.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Assche G, Dignass A, Reinisch W, van der Woude CJ, Sturm A, De Vos M, et al. The second European evidence-based Consensus on the diagnosis and management of Crohn's disease: special situations. J Crohns Colitis. 2010;4:63–101. doi: 10.1016/j.crohns.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Beaugerie L, Seksik P, Nion-Larmurier I, Gendre JP, Cosnes J. Predictors of Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:650–656. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.12.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Louis E, Michel V, Hugot JP, Reenaers C, Fontaine F, Delforge M, et al. Early development of stricturing or penetrating pattern in Crohn's disease is influenced by disease location, number of flares, and smoking but not by NOD2/CARD15 genotype. Gut. 2003;52:552–557. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.4.552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Romberg-Camps MJ, Dagnelie PC, Kester AD, Hesselink-van de Kruijs MA, Cilissen M, Engels LG, et al. Influence of phenotype at diagnosis and of other potential prognostic factors on the course of inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:371–383. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Allez M, Lemann M, Bonnet J, Cattan P, Jian R, Modigliani R. Long term outcome of patients with active Crohn's disease exhibiting extensive and deep ulcerations at colonoscopy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:947–953. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05614.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Fiorino G, Buisson A, Danese S. First-line therapy in adult Crohn's disease: who should receive anti-TNF agents? Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013;10:345–351. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2013.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Dubinsky MC, Kugathasan S, Mei L, Picornell Y, Nebel J, Wrobel I, et al. Increased immune reactivity predicts aggressive complicating Crohn's disease in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6:1105–1111. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2008.04.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Abreu MT, Taylor KD, Lin YC, Hang T, Gaiennie J, Landers CJ, et al. Mutations in NOD2 are associated with fibrostenosing disease in patients with Crohn's disease. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:679–688. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.35393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cleynen I, González JR, Figueroa C, Franke A, McGovern D, Bortlík M, et al. Genetic factors conferring an increased susceptibility to develop Crohn's disease also influence disease phenotype: results from the IBDchip European Project. Gut. 2013;62:1556–1565. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2011-300777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Siegel CA, Siegel LS, Hyams JS, Kugathasan S, Markowitz J, Rosh JR, et al. Real-time tool to display the predicted disease course and treatment response for children with Crohn's disease. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2011;17:30–38. doi: 10.1002/ibd.21386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Dubinsky M. Have we changed the natural history of pediatric Crohn's disease with biologics? Dig Dis. 2014;32:360–363. doi: 10.1159/000358137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Peyrin-Biroulet L, Sandborn W, Sands BE, Reinisch W, Bemelman W, Bryant RV, et al. Selecting therapeutic targets in inflammatory bowel disease (STRIDE): determining therapeutic goals for treat-to-target. Am J Gastroenterol. 2015;110:1324–1338. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2015.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Zubin G, Peter L. Predicting endoscopic crohn's disease activity before and after induction therapy in children: a comprehensive assessment of PCDAI, CRP, and fecal calprotectin. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2015;21:1386–1391. doi: 10.1097/MIB.0000000000000388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]