INTRODUCTION

Preferences for future medical treatments may be documented in a legal document known as an advance directive (AD). Despite national efforts to promote AD completion,1 men, blacks, and those with less education less frequently complete ADs.2 , 3 However, it remains unclear whether such groups differ in their willingness to complete ADs or have different opportunities to do so. The latter would suggest disparities in access to advance care planning. We sought to elucidate this key distinction by assessing associations between demographic characteristics and AD completion within two randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that presented uniform opportunities to participants who may be targeted for AD completion.

METHODS AND FINDINGS

We performed secondary analyses of data from two RCTs (NCT02289105 and NCT02017548). RCT 1 compared three ADs that differed in how information was presented to 484 people with serious illnesses enrolled from 30 clinics within two Pennsylvania health systems between February 2014 and March 2016.4 The study protocol for trial 1 has been published elsewhere.4 RCT 2 compared methods of encouraging AD completion among new employees at a Pennsylvania healthcare system between November 2014 and August 2015. An AD completion module was inserted into the online system through which all new healthcare system employees complete employment documents. Employees were randomly assigned a module that either did or did not require them to make an active choice of whether to complete an AD.

Participants in each trial received standardized educational materials and a professionally endorsed AD form on which they could indicate preferences for five life-sustaining interventions and a general treatment goal. Institutional review boards approved all procedures.

The primary outcome in these secondary analyses was AD completion, defined as patients returning an AD via mail in RCT 1 and employees completing an AD online in RCT 2. Independent variables were all demographics measured in each trial (Table 1). Each trial was independently analyzed.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Enrolled Participants in Two Randomized Trials Supporting Advance Directive Completion

| Characteristic | Trial 1 | Trial 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Seriously ill patients | New health system employees | |

| Number enrolled | 484 | 1279 |

| Age in years (median, interquartile range) | 63 (56.0–69.5) | 29 (25.0–38.0) |

| Sex | ||

| Female | 212 (44.0%) | 918 (71.8%) |

| Male | 270 (56.0%) | 333 (26.0%) |

| Other/prefer not to answer | – | 28 (2.2%) |

| Race | ||

| White | 337 (69.6%) | 678 (53.0%) |

| Black | 123 (25.4%) | 344 (26.9%) |

| Mixed or Other | 24 (5.0%) | 197 (15.4%) |

| Prefer not to answer | – | 60 (4.7%) |

| Highest level of education completed | ||

| High school or less | 172 (35.5%) | 108 (8.4%) |

| Some college | 111 (23.2%) | 269 (21.0%) |

| College degree | 116 (24.3%) | 602 (47.1%) |

| Post-college degree | 79 (16.5%) | 224 (17.5%) |

| Missing | – | 76 (5.9%) |

| Religious affiliation | ||

| Catholic | 165 (34.1%) | Not asked |

| Protestant | 173 (35.7%) | |

| Other Christian | 48 (9.9%) | |

| Other | 98 (20.3%) | |

| Marital status | ||

| Currently married | 309 (64.4%) | Not asked |

| Never married | 68 (14.2%) | |

| Divorced | 60 (12.5%) | |

| Separated | 13 (2.7%) | |

| Widowed | 30 (6.3%) | |

| Household income (annual) | ||

| Less than $30,000 | 129 (26.7%) | Not asked |

| $30,000–59,999 | 135 (27.9%) | |

| $60,000–89,999 | 92 (19.0%) | |

| $90,000 or more | 128 (26.5%) | |

| Primary diagnosis | ||

| Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease | 23 (4.8%) | Not applicable |

| Other incurable lung disease | 21 (4.3%) | |

| Gastrointestinal cancer | 99 (20.5%) | |

| Genitourinary cancer | 90 (18.6%) | |

| Breast cancer | 29 (6.0%) | |

| Pancreatic or gallbladder cancer | 59 (12.2%) | |

| End-stage renal disease | 35 (7.2%) | |

| Heart failure | 11 (2.3%) | |

| Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis | 38 (7.9%) | |

| Lung cancer | 79 (16.3%) | |

| Prior clinical degree* | Not asked | 269 (21.0%) |

| Type of employment | ||

| Full-time | Not applicable | 933 (73.0%) |

| Part-time | 346 (27.1%) | |

*Participants were considered to have clinical degrees if they had any of the following designations: MD, MSN, BSN, RN, LPN, DO, NP, PA, DPT, PharmD, DVM, CRNA, speech pathology, CNA, CMA, surgical tech, medical assistant, nurse assistant, or medical technologist

We used multivariable logistic regression to examine associations between demographics and AD completion. Randomization arm was entered as a fixed effect in analyses of both RCTs, and recruiter was an additional fixed effect for RCT 1.

RESULTS

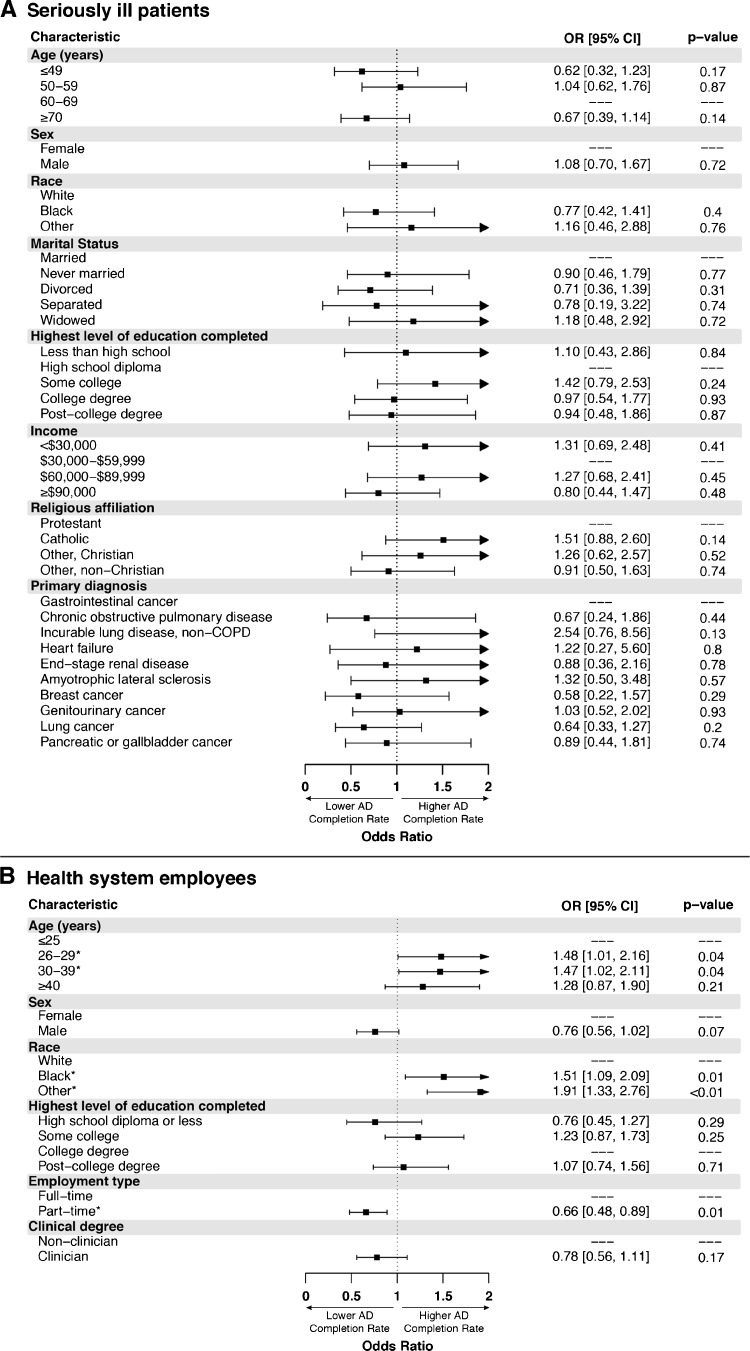

Characteristics of participants in each RCT are reported in Table 1. In RCT 1, 286 of 484 seriously ill outpatients (59.1%) completed an AD. In multivariable analyses, none of the measured patient characteristics (age, sex, race, marital status, income, level of education, religious affiliation, and primary diagnosis) were associated with AD completion (all p > 0.10; Fig. 1a).

Figure 1.

Characteristics of participants as predictors of advance directive completion. CI = confidence interval. Characteristics entered in fully adjusted logistic regression with randomization arm (and recruiter for RCT 1) entered as fixed effect.

In RCT 2, 355 of the 1279 participating employees (27.8%) completed an AD. In fully adjusted models, participants who were black (OR = 1.51; 95% CI = 1.09–2.09) or of mixed/other race (OR = 1.91; 95% CI = 1.33–2.76) were significantly more likely than white participants to complete an AD (Fig. 1b). Part-time employees were less likely than full-time employees to complete ADs (OR = 0.66; 95% CI = 0.48–0.89). No other characteristic was significantly associated with AD completion (all p > 0.05).

DISCUSSION

This study shows that when all individuals are given the same opportunities to complete ADs, demographic characteristics are not consistently associated with AD completion. Because results from previous observational studies—which found that men, blacks, and less-educated persons completed ADs less frequently—were not observed when equal opportunities to complete ADs were ensured, those prior studies were likely identifying disparities in patients’ access to such opportunities rather than differences in patients’ willingness to complete ADs.

The findings of this study may not generalize beyond the populations studied. RCT 1 participants agreed to participate in a study of ADs, perhaps creating a motivated cohort. The employees in RCT 2 were younger and may approach ADs differently from the general public. However, both patients and healthy individuals have been targeted for AD efforts. We cannot draw conclusions about unmeasured participant characteristics. Finally, we cannot rule out the possibility that the lack of observed associations stemmed from insufficient power, but the point estimates of most of the effects argue against this possibility.

Our findings suggest that future work should seek to mitigate system- or clinician-based barriers to offering opportunities for AD completion equally, rather than focusing solely on different demographic groups’ preferences for completing ADs. By providing equal opportunities for AD completion to all patients, such efforts may also reduce demographic differences in the intensity of end-of-life care that patients receive.5

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Michael Olorunnisola, Lucy Chen, Sarah Grundy, Stephanie Szymanski, Margaret W. Hays, Heather Tomko, and Michael Josephs for their contributions to these clinical trials. This work has been directly supported by the Otto Haas Charitable Trust and the Gordon and Betty Moore Foundation. Dr. Hart was supported by grant K12HL109009 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, National Institutes of Health. A previous version of this work was presented orally by Dr. Hart at the American Thoracic Society International Conference in 2017.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Halpern SD. Toward evidence-based end-of-life care. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(21):2001–3. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1509664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Huang IA, Neuhaus JM, Chiong W. Racial and ethnic differences in advance directive possession: role of demographic factors, religious affiliation, and personal health values in a national survey of older adults. J Palliat Med. 2016;19(2):149–56. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2015.0326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Harrison KL, Adrion ER, Ritchie CS, Sudore RL, Smith AK. Low completion and disparities in advance care planning activities among older medicare beneficiaries. JAMA Intern Med. 2016;176(12):1872–5. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2016.6751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gabler NB, Cooney E, Small DS, Troxel AB, Arnold RM, White DB, et al. Default options in advance directives: study protocol for a randomised clinical trial. BMJ Open. 2016;6(6):e010628. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010628. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kelley AS, Ettner SL, Morrison RS, Du Q, Wenger NS, Sarkisian CA. Determinants of medical expenditures in the last 6 months of life. Ann Intern Med. 2011;154(4):235–42. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-154-4-201102150-00004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]