Abstract

Background and Objective

Inadequate competing interest declarations present interpretive challenges for editors, reviewers, and readers. We systematically studied a common euphemism, ‘unpaid consultant,’ to determine its occurrence in declarations and its association with vested interests, authors, and journals.

Methods

We used Google Scholar, a search engine that routinely includes disclosures, to identify 1164 occurrences and 787 unique biomedical journal publications between 1994 and 2014 that included one or more authors declaring themselves as an “unpaid consultant.” Changes over time were reckoned with absolute and relative yearly rates, the latter normalized by overall biomedical publication volumes. We further analyzed declarations according to author, consultancy recipient, and journal.

Results

We demonstrate increases in the use of “unpaid consultant” since 2004 and show that such uninformative declarations are overwhelmingly (801/865, 92.6%) associated with for-profit companies and other vested interests, most notably in the pharmaceutical, device, and biotech industries.

Conclusions

Disclosing ‘unpaid’ relationships with for-profit companies typically signals but does not explain competing interests. Our findings challenge editors to respond to the increasing use of language that may conceal rather than illuminate conflicts of interest.

KEY WORDS: conflict of interest, competing interest, disclosure, unpaid consultant

INTRODUCTION

Declaration of potential conflicts of interest is now required when submitting manuscripts to almost all biomedical journals, but there is much uncertainty regarding their utility for editors, reviewers, and readers.1,2 Although financial involvements are typically emphasized, non-financial competing interests are also important but more difficult to define, measure, and manage.3

Authors are increasingly referring to themselves as ‘unpaid consultants.’ By its literal meaning, this indicates the absence of direct monetary reimbursement. Other benefits from industry involvement may nonetheless constitute actual or perceived conflicts of interest and ought to be disclosed. We systematically studied the term ‘unpaid consultant’ in medical article disclosures by analyzing its use over time, links to vested interests, and association with particular journals and authors.

METHODS

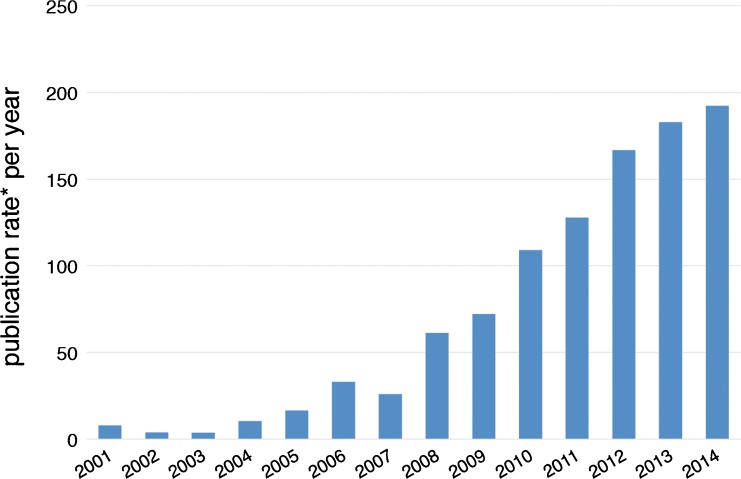

We used Google Scholar to determine occurrence of “unpaid consultant” in biomedical publication disclosures during 1994-2014. Approximately 6% of articles meeting criteria had two or more authors declaring unpaid consultancy; we analyzed results both per article (n = 787, Fig. 1) and per disclosure (n = 865, Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Articles with unpaid consultant authors. Data indicate unique articles (n = 779) published during 2001–2014 with one or more authors declaring unpaid consultancy to one or more for-profit companies, normalized to control for growth in overall publication volumes. *Histogram bars indicate target article count divided by total MEDLINE citation volume (×106) for that year (see text)

Table 1.

Breakdown of Unpaid Consultancy by Category

| Year | Drug | Device | Biotech | IT | Govt | NGO | CRO | Other | Totals |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2014 | 74 | 55 | 13 | 17 | 1 | 7 | 3 | 5 | 175 |

| 2013 | 65 | 45 | 30 | 16 | 6 | 7 | 0 | 4 | 173 |

| 2012 | 67 | 45 | 21 | 5 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 3 | 152 |

| 2011 | 45 | 41 | 10 | 9 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 109 |

| 2010 | 25 | 29 | 18 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 87 |

| 2009 | 18 | 18 | 5 | 2 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 50 |

| 2008 | 17 | 19 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 44 |

| 2007 | 8 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 18 |

| 2006 | 7 | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 21 |

| 2005 | 5 | 4 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 11 |

| 2004 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 |

| 2003 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| 2002 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 2001 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 4 |

| 2000 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1999 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| 1998 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1997 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1996 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1995 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| 1994 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Totals | 335 | 278 | 104 | 62 | 36 | 28 | 3 | 19 | 865 |

Govt includes local and regional as well as national governmental authorities. NGO refers to any not-for-profit non-governmental organization. CRO refers to for-profit clinical research organizations. ‘Other’ includes various for-profit concerns, including management consultancy, non-medical research, and nutritional and alternative healthcare marketing. Declarations of unpaid consultancy to multiple companies in a given category were counted only once; the indicated counts, particularly for drug, are thus conservative

Results

Review of each Google Scholar ‘hit’ indicated that most were relevant, inasmuch as authors referred to relationships that were not directly financial but nonetheless suggested important and usually unexplained engagement with for-profit companies. To control for trends in publication volumes, we used annual MEDLINE citation counts (https://www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/medline_cit_counts_yr_pub.html, last accessed 4 September 2016). As Fig. 1 illustrates, the normalized publication rate of health-related articles with authors disclosing unpaid consultancy increased markedly between 2004 and 2014.

Further analysis of ‘unpaid consultancies’ showed these were overwhelmingly (801/865, 92.6%) associated with for-profit companies (Table 1). Declarations of unpaid consultancy to companies in various categories, including not-for-profit entities (government and NGO), were found to increase comparably during this 10-year period. With very few exceptions, authors provided no detail of these relationships or the associated benefits, either to the companies/entities or themselves.

A wide range of medical journals included declarations of unpaid consultancy; American journals predominated, and some disciplines, notably orthopedics, were overrepresented (data not shown). Some authors made frequent, in most cases identical, disclosures to multiple journals. Additionally, most authors describing themselves as unpaid consultants also disclosed paid relationships with for-profit companies. For example, five of nine authors with 10 or more disclosures of unpaid consultancy also declared financial relationships in 73/152 articles, naming for-profit companies 159 times. While this finding accords with studies showing that individual authors often report multiple conflicts,3 the connection between financial conflicts and the more recent surge of ‘unpaid’ disclosures remains unclear.

DISCUSSION

The use of ‘unpaid consultant’ in disclosures relates to the now prevalent requirement for authors and editors to recognize and manage conflicts of interest. The term may be disingenuous, however, if it fails to identify research funding, conference fees, travel expenses or other benefits from engagement with for-profit industries. Disclosure statements should be as complete and accurate as possible2 to enable editors, reviewers, and readers to appraise the relevance of competing interests to an author’s collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. Declarations of unpaid consultancy appear unhelpful and may do more to conceal than illuminate.

People commonly underestimate their own vulnerability to bias and tend to be better at judging others’ biases than their own.4 Submitting authors have an understandable motivation to portray themselves as willing to disclose possible sources of bias. This motivation, coupled with routine disclosure requirements, may have contributed to the increase in authors describing themselves as ‘unpaid consultants.’ This terminology signals a relationship but almost never explains what it entails, and thus provides little basis to appraise how it may affect an author’s motivation and judgment. Our results are consonant with the view that financial disclosure alone is insufficient, that professional/intellectual conflicts are comparably important, and that standards for disclosure of the latter are currently inadequate.

In conclusion, full and honest disclosure of authors’ competing interests, both financial and non-financial, is essential, but in itself does not assure freedom from bias.2 , 5 In particularly ‘sensitive’ domains, such as treatment guideline preparation, excluding rather than managing conflicts has been recommended.6 More generally, our results indicate the need for further examination of language and meaning in competing interest declarations and suggest that editorial requirements for disclosure be strengthened.

Acknowledgements

Andrew Herxheimer (deceased 21 February 2016), founder of Drug and Therapeutics Bulletin, contributed keen insight and elegant prose to initial phases of this work. Lyn Wood, New Zealand librarian, assisted with literature searches. University of Auckland HoD Fund 11096 supported this work. David Menkes has been a paid member of a Data Safety Monitoring Board (Zenith Technology, Dunedin, New Zealand) and is a member of the conflict of interest working group, International Society of Drug Bulletins.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflicts of Interest

All other authors declare no conflicts.

References

- 1.Lo B. Commentary: Conflict of interest policies: an opportunity for the medical profession to take the lead. Acad Med. 2010;85:9–11. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c46e96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Loewenstein G, Sah S, Cain DM. The unintended consequences of conflict of interest disclosure. JAMA. 2012;307:669–70. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bero L. What is in a name? Nonfinancial influences on the outcomes of systematic reviews and guidelines. J Clin Epidemiol. 2014;67:1239–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pronin E. Perception and misperception of bias in human judgment. Trends Cogn Sci. 2007;11:37–43. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2006.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wilson M. Is transparency really a panacea? J R Soc Med. 2014;107:216–7. doi: 10.1177/0141076814532744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Menkes DB, Bijl D. Credibility and trust are required to judge the benefits and harms of medicines. BMJ. 2017;358:j4204. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j4204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]