Highlights

-

•

An interaction between warfarin and cannabidiol is described

-

•

The mechanisms of cannabidiol and warfarin metabolism are reviewed

-

•

Mechanism of the interaction is proposed

-

•

INR should be monitored in patients when cannabinoids are introduced

1. Introduction

The use of cannabis products for the treatment of epilepsy and other chronic diseases is growing rapidly [1], [2]. Cannabis products include any pharmaceutical or artisanal derivatives of the cannabis plant [2]. One such agent is cannabidiol (CBD), one of the phytocannabinoids frequently used by patients with seizures. Current data regarding interactions between CBD and other pharmaceuticals are primarily limited to anti-seizure drugs [3], [4]. This case report observes a clinically significant interaction between pharmaceutical grade cannabidiol (Epidiolex®; Greenwich Biosciences, Inc.) and warfarin, one of the most widely used oral anticoagulants.

2. Case report

A 44-year-old Caucasian male with Marfan Syndrome, mechanical mitral valve replacement, warfarin therapy, and post-stroke epilepsy was enrolled in the University of Alabama at Birmingham open-label program for compassionate use of cannabidiol for the management of treatment-resistant epilepsy (NCT02700412). His seizures began at age 27 concurrent with diagnosis of stroke during the post-operative period from cardiac surgery. Despite initial control of seizures on monotherapy, events returned in 2011 prompting adjustment of anti-seizure medications and eventual consideration of epilepsy surgery. Following video EEG monitoring, he was determined to be a poor surgical candidate due to non-localized seizure onset. Additionally, the need for anticoagulation due to mechanical valve limited more invasive testing for localization of seizure focus as well as posed a challenge for completion of any surgical resection. He was subsequently referred to the UAB CBD program.

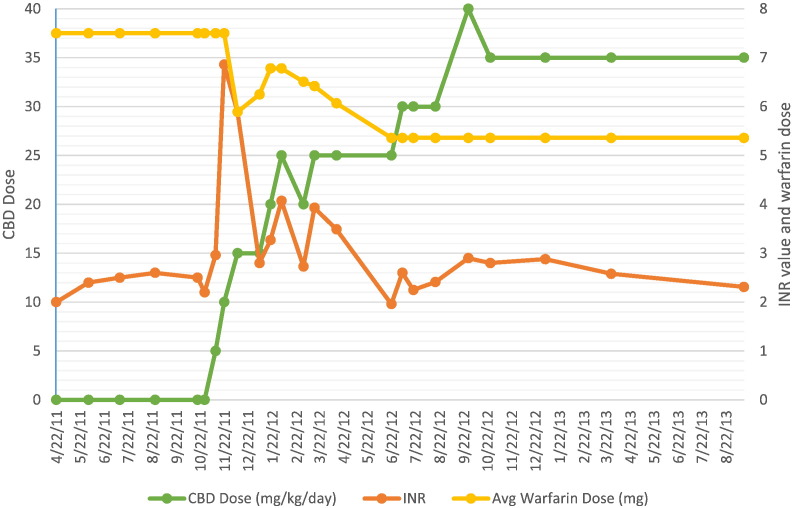

At the time of study enrolment, the patient was taking lamotrigine 400 mg and levetiracetam 1500 mg, both twice daily. He was also taking warfarin 7.5 mg daily with a goal International Normalized Ratio (INR) of 2–3. Prior to study entry, his INR had been stable for at least 6 months with levels ranging from 2.0 to 2.6 (Fig. 1). At the initial study visit, his baseline INR was obtained and he was placed on the starting dose of CBD at 5 mg/kg/day divided twice daily. Per study protocol (www.uab.edu/cbd) CBD dose was increased in 5 mg/kg/day increments every two weeks.

Fig. 1.

INR Trend over time.

With up-titration of CBD oil, a non-linear increase in the INR was noted (Table 1, Fig. 1). Warfarin dosage adjustments were made by primary care physician in effort to maintain an INR within his therapeutic range. At the most recent study visit his warfarin dose had been reduced by approximately 30%. The patient was followed clinically without bleeding complications.

Table 1.

Visit summary.

| Visit # | Day # | Date | Weight (kg) | CBD dose (mg/kg/day) | CBD dose (mg BID) | Coumadin dose averaged over time between visits (mg) | INR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 0 | 10/29/15 | 105.9 | 0 | 0 | 7.5 | 2.22 |

| 2 | 14 | 11/12/15 | 105.9 | 5 | 265 | 7.5 | 2.96 |

| 3 | 28 | 11/23/15 | 105.5 | 10 | 528 | 7.5 | 6.86 |

| 4 | 42 | 12/10/15 | 105.5 | 15 | 790 | 5.89 | 4.40 |

| 5 | 70 | 1/07/16 | 104.8 | 15 | 786 | 6.25 | 2.8 |

| 6 | 84 | 1/21/16 | 105.8 | 20 | 1058 | 6.78 | 3.27 |

| 7 | 98 | 2/04/16 | 108.2 | 25 | 1352 | 6.78 | 4.07 |

| 8 | 126 | 3/03/16 | 107 | 20 | 1070 | 6.51 | 2.73 |

| 9 | 140 | 3/17/16 | 106.8 | 25 | 1335 | 6.42 | 3.93 |

| 10 | 168 | 4/14/16 | 107.1 | 25 | 1338 | 6.07 | 3.49 |

| 11 | 238 | 6/23/16 | 105.1 | 25 | 1313 | 5.36 | 1.96 |

| 12 | 252 | 7/07/16 | 104.6 | 30 | 1570 | 5.36 | 2.6 |

| 13 | 266 | 7/21/16 | 105.7 | 30 | 1585 | 5.36 | 2.25 |

| 14 | 294 | 8/18/16 | 104.1 | 30 | 1562 | 5.36 | 2.41 |

| 15 | 322 | 9/15/16 | 104.8 | 35 | 1834 | 5.36 | 2.31 |

| 16 | 336 | 9/29/16 | 105.5 | 40 | 2110 | 5.36 | 2.90 |

| 17 | 364 | 10/27/16 | 106.9 | 35 | 1870 | 5.36 | 2.80 |

| 18 | 434 | 1/05/17 | 107.2 | 35 | 1876 | 5.36 | 2.88 |

| 19 | 518 | 3/30/17 | 103 | 35 | 1802 | 5.36 | 2.58 |

3. Discussion

Despite the emergence of novel oral anticoagulants, warfarin continues to be the most commonly used oral anticoagulant worldwide [5]. A potent inhibitor of vitamin K epoxide reductase complex, warfarin functions by disrupting the production of vitamin-K-dependent clotting factors [6]. The drug is comprised of R and S stereoisomers with S-warfarin being the more active of the two. Warfarin is metabolized via the CYP450 hepatic enzyme complex and cleared through the renal system, however each stereoisomer is metabolized differently. The S-isomer is predominantly metabolized by CYP2C9 and R-warfarin by way of CYP3A4 with lesser involvement of CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2C8, CYP2C9, CYP2C18 and CYP2C19 [6]. Resultantly, factors that impact the CYP2C9 enzyme (genetic polymorphisms, other medications, etc.) alter warfarin activity [5], [7], [8]. Due to its narrow therapeutic index and variability of dosing requirements amongst individuals, frequent monitoring of the INR is required to both achieve and maintain appropriate anticoagulant effects on the blood. Drugs that compete as substrates for these cytochromes or inhibit their activity may increase warfarin plasma concentrations and INR, potentially increasing the risk of bleeding. Conversely, drugs which induce these metabolic pathways may decrease warfarin plasma concentrations and INR, potentially leading to reduced efficacy.

The metabolism of CBD is also by way of the hepatic P450 enzyme system. To date there are seven major isoforms identified that contribute to this process: CYP1A1, CYP1A2, CYP2C9, CYP2C19, CYP2D6, CYP3A4, and CYP3A5, with CYP3A4 and CYP2C19 being the dominant contributors [9]. Five of the seven isoforms are also involved with metabolism of warfarin, including CYP2C9, which is the dominant enzyme for S-warfarin, and CYP3A4, which is the dominant enzyme for R-warfarin [7], [9]. In addition to competing for enzymes in same metabolic pathway as warfarin, CBD has been demonstrated to act as a potent competitive inhibitor of all seven of its own CYP enzymes and as such could further impair the degradation of warfarin [10], [11]. It is this combination of factors that presumably constitutes the observed rise in INR values with concomitant warfarin and CBD administration.

4. Conclusions

This finding suggests an interaction between warfarin and cannabidiol, underscoring the importance of monitoring appropriate laboratory work in patients receiving concomitant cannabis products and other pharmaceuticals, particularly those metabolized by the cytochrome P450 enzyme system. In patients taking warfarin, INR monitoring is suggested during initiation and up-titration of cannabinoids.

References

- 1.Szaflarski J.B., Bebin E.M. Cannabis, cannabidiol, and epilepsy — from receptors to clinical response. Epilepsy Behav. 2014;41(December 2014):277–282. doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2014.08.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Friedman D., Devinsky O. Cannabinoids in the treatment of epilepsy. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(11):1048–1058. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1407304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gaston T.E. Interactions between cannabidiol and commonly used antiepileptic drugs. Epilepsia. 2017;58(9):1586–1592. doi: 10.1111/epi.13852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geffrey A.L. Drug–drug interaction between clobazam and cannabidiol in children with refractory epilepsy. Epilepsia. 2015;56(8):1246–1251. doi: 10.1111/epi.13060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnson J.A. Clinical pharmacogenetics implementation consortium (CPIC) guideline for pharmacogenetics-guided warfarin dosing: 2017 update. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2017 doi: 10.1002/cpt.668. (n/a-n/a) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coumadin Product Data- FDA.

- 7.Whirl-Carrillo M., EMM, Hebert J.M., Gong L., Sangkuhl K., Thorn C.F. Pharmacogenomics knowledge for personalized medicine. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2012;92(4):414–417. doi: 10.1038/clpt.2012.96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wadelius M., Chen L.Y., Downes K., Ghori J., Hunt S., Eriksson N. Common VKORC1 and GGCX polymorphisms associated with warfarin dose. J Pharm. 2005;5(4):262–270. doi: 10.1038/sj.tpj.6500313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jiang R., Yamaori S., Takeda S., Yamamoto I., Watanabe K. Identification of cytochrome P450 enzymes responsible for metabolism of cannabidiol by human liver microsomes. Life Sci. 2011;89(5–6):165–170. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamaori S., Ebisawa J., Okushima Y., Yamamoto I., Watanabe K. Potent inhibition of human cytochrome P450 3A isoforms by cannabidiol: role of phenolic hydroxyl groups in the resorcinol moiety. Life Sci. 2011;88(15–16):730–736. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2011.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yamaori S., Koeda K., Kushihara M., Hada Y., Yamamoto I., Watanabe K. Comparison in the in vitro inhibitory effects of major phytocannabinoids and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons contained in marijuana smoke on cytochrome P450 2C9 activity. Drug Metab Pharmacokinet. 2012;27(3):294–300. doi: 10.2133/dmpk.dmpk-11-rg-107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]