Abstract

TNBC (Triple Negative Breast Cancer) is a subtype of breast cancer with an aggressive phenotype which shows high metastatic capability and poor prognosis. Owing to its intrinsic properties like heterogeneity, lack of hormonal receptors and aggressive phenotype leave chemotherapy as a mainstay for the treatment of TNBC. Various studies have demonstrated that chemotherapy alone or therapeutic drugs targeting TNBC pathways, epigenetic mechanisms and immunotherapy alone have not shown significant improvement in TNBC patients. On the other hand, a combination of therapeutic drugs or addition of chemotherapy with therapeutic drugs has shown substantial improvement in results and proven to be an effective strategy for TNBC treatment. This review sheds light on effective combinational drug strategies and current clinical trial status of various combinatorial drugs for the treatment of TNBC.

Keywords: Cell Signalling Pathways, Drug Therapy, Triple Negative Breast Cancer

Introduction

A search of term ‘triple-negative breast cancer’ in PubMed hits more than 7000 publications; of which 5000 were published in the last 5 years. TNBC (triple negative breast cancer) is an intrinsically heterogeneous disease which accounts for nearly 15–20% cases among 1.7 million new breast cancer cases diagnosed annually across the world [1].

Chemotherapy remains the mainstay for the treatment of TNBC due to lack of targeted therapies. Hormone-targeted drugs like tamoxifen, aromatase inhibitors and Her2-targeted drugs like trastuzumab are ineffective towards the treatment of TNBC due to the absence of receptors. A localized breast cancer can be primarily treated by surgery, while the metastasized breast cancer treatment focuses on improving the quality of life (QOL) by increasing the outcome of pCR (pathological clinical response), PFS (progression-free survival) and prolonging the OS (overall survival) rate of the patient. The rapidly increasing evidence of research and lack of therapeutic options show the significance of investigating effective therapeutic strategies for the treatment of TNBC.

Molecular characteristics of TNBC

TNBC is a breast cancer subtype defined as lack of expression of hormonal receptors (oestrogen (ER) negative (<1%), progesterone (PR) negative (<1%) and HER2/neu) [2,3]. TNBC is a breast cancer subtype with similar characteristics of basal-like with an aggressive phenotype and high metastatic rate. TNBC exhibit properties of high histological grade [4] with distinct pathological and clinical features and associated with poor prognosis [5]. The 5-year survival rate for TNBC is 70% less than other breast cancer subtypes having 80% survival rates [6].

‘BRCAness’ can be defined as inherited and acquired mutations in DNA repair mechanisms in breast cancer cells [7]. BRCAness enriched phenotype in TNBC can be used as a biomarker for the exploitation of therapeutic options and clinical implications [8,9]. TNBC showed a high prevalence of BRCA mutations when compared with other subtypes of breast cancer [10–12]. Studies showed that 15–20% of TNBC patients carry BRCA1/2 germline mutations [10]. In recent years, gene expression signatures have been linked with TNBC to unravel distinct molecular subtypes [13]. TNBCs overlap up to 70% with basal-like breast cancer but are clinically and histopathologically distinct [14]. Based on the gene expression profiling and meta-analysis of 21 datasets of breast cancer, TNBCs are categorized into seven subclasses: Basal-like subclass (Basal-like 1 and Basal-like 2), Mesenchymal (M), MSL (mesenchymal stem-like), IM (immunomodulatory), LAR (luminal androgen receptor) and others. Identification of distinct TNBC subtypes may provide biomarkers for selection of patients in designing clinical trials and may help in the prediction of response to the treatment [13].

A study in 2006 showed that TNBC is linked to ethnic and menopausal differences which are not observed in ER+/Her2− and ER+/Her2+ breast cancer. The study also reports that prevalence of TNBC in African American women is 47%, twice when compared with white women which accounts only 22%, and this rate further increases to three-fold when considering factors like age and stage of diagnosis. African American premenopausal women diagnosed with breast cancer showed 39% of TNBC [15].

Pathways and therapeutic targets in TNBC

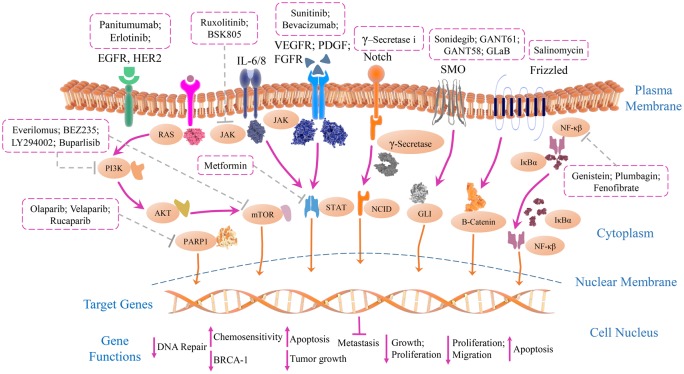

Cancer is a network of complex signalling pathways controlled by a cascade of events. Some pathways are highly regulated and are indispensable for the growth, survival, invasion and progression of TNBC. Various pathways are targeted and only a few pathways are found to be sensitive and effective targets for the treatment of TNBC (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Overview of signalling pathways involved with identified potential inhibitors in TNBC.

The network of multiple signalling cascades with downstream effectors help in the maintenance of growth, proliferation, survival and metastasis of TNBC cells. The signalling pathways like NF-κB, PI3/AKT/mTOR, JAK/STAT and RTKs (receptor tyrosine kinases) are implicated in the pathogenesis of TNBC cells. The developmental pathways like Wnt/β-Catenin, Notch, Hh (Hedgehog) are associated with invasion, migration, metastatic potential and also self-renewal ability of cancer stem cells. PARP inhibitors directly interact and inhibit molecules associated with DNA repair to increase the cellular damage ultimately leading to apoptosis. Most of the potential inhibitors directly induced apoptosis in TNBC by up-regulation of Bad, Caspase 3 and down-regulation of BCL-2, BCL-XL and survivin. While several inhibitors showed therapeutic response through control of tumour growth and antiproliferative effect on TNBC cells, some inhibitors increased chemosensitivity of TNBC cells. So, synergistic targeting of chemotherapy drugs and therapeutic inhibitors may prove to be an effective way of treatment for TNBC.

NF-κB is a key regulator of inflammatory response, apoptosis and angiogenesis in TNBC and shows four-fold differential expression when compared with normal breast cells [16]. Resistance in cancer cells is developed by abnormal activation of the NF-κB pathway [17]. More than 750 natural and synthetic inhibitors like small molecules, antioxidants, small RNA/DNA, peptides, viral and microbial proteins have been identified as inhibitors of the NF-κB pathway [18]. These inhibitors are used to treat various types of diseases and cancers, but there are no therapeutic drugs for TNBC which may directly interact with NF-κB pathway and thereby treat TNBC. Studies have shown that apoptosis in TNBC is also regulated by the NF-κB pathway. Genistein, a relatively nontoxic and one of the major soy isoflavones, induce apoptosis in TNBC cells by down-regulating the expression of BCL-2, BCL-xL and Cyclin B1 possibly mediated by activation of NF-κB through Notch-1 signalling pathway [19]. Plumbagin inactivates DNA-binding activity of NF-κB and BCL-2 and induces apoptosis in TNBC cells with no effect on normal breast cells [20]. Fenofibrate has antiproliferative effects and induces apoptosis by activation of the NF-κB pathway in TNBC by up-regulation of Bad and activation of Caspase-3, down-regulation of BCL-xL, survivin [21].

JAK/STAT pathway is a key regulator of cellular functions like cell differentiation, proliferation, migration, survival and apoptosis [22]. STAT3 is overexpressed in more than 50% of TNBCs associated with poor prognosis and invasive phenotype [23,24]. Metformin selectively inhibits STAT3 and restricts the growth of the tumour and induces apoptosis in TNBC cells [25]. Ruxolitinib, an inhibitor of JAK1/2 is approved for myelofibrosis treatment [26]. This drug in combination with paclitaxel, doxorubicin and cyclophosphamide is being tested in Phase II clinical trials for triple negative inflammatory breast cancers (Trial Ref.: NCT02876302). In a study, the results showed that JAK2 gene is amplified in TNBC cells treated with chemotherapy when compared with the tumours before the treatment indicating the JAK2 role in chemoresistance of TNBC. Ruxolitinib failed to inhibit tumour progression in JAK2 amplified TNBC cells. BSK805, a JAK2-specific inhibitor when combined with chemotherapy reduced the tumour growth in mice [27].

PI3K–AKT–mTOR pathway regulates key cellular functions like cell metabolism, proliferation, motility and survival [28]. Almost 60% of TNBCs showed overactivation of PI3K, with its role in deletion or mutation of PTEN tumour suppressor gene. AKT is associated with apoptosis in TNBC by regulating pro-apoptotic molecules like BAD (BCL-2 associated death promoter) [29–31]. AKT activates mTOR through TSC1/2 leading to protein synthesis and cell growth [32]. Activation of PI3K/AKT pathway in ELK3-Knockdown TNBC cells resulted in impaired autophagy and increased chemosensitivity to doxorubicin [33]. Few studies reported that PI3/AKT inhibition increases PARP sensitivity to TNBC cells. PI3K suppression increases sensitivity to PARPi in both BRCA1-deficient and -proficient TNBC patients [31,34]. Buparlisib (PI3K/AKT inhibitor) hyperactivates ERK and MEK1 causing down-regulation of BRCA1. This favours the activity of Olaparib (PARPi) followed by reduction in cancerous cell proliferation [35]. One of the other studies reported that association of Rucaparib (PARPi) and LY294002 (PI3Ki) in BRCA1-deficient cells improves the activity of PARPi [36].

mTOR is a downstream constituent of PI3K/AKT pathway and regulates cellular functions like cell growth, survival, protein turnover and translocation. It exists in two different complexes, mTORC1 and mTORC2. mTORC1 is involved in activation of protein translation and mTORC2 is responsible for AKT phosphorylation. Clinical efficiency of numerous drugs targeting mTOR in TNBC patients is under investigation. Everolimus exhibited antitumour activity in basal-like breast cancer cells in preclinical studies [37]. BEZ235 has shown resistance to the TORC1/2 activity which further activates NOTCH1 that increases population of cancer stem cells. NOTCH activation depends upon FGFR (fibroblast growth factor receptor) 1 (FGFR1)-mitochondrial metabolism. Thus, a combined approach of TORC1/2 inhibitor and FGFR1-mitochondrial metabolism antagonists is required [38]. Some clinical trials have shown that addition of everolimus to paclitaxel in Phase II/III TNBC patients did not show any significant improvement in response ration (RR) and pCR [39–41].

Role of developmental pathways in TNBC

Wnt/β-catenin signalling plays a major role in embryonic development and tumorigenesis by regulating cell proliferation, differentiation and survival [42–44]. Previous studies reported that aberrant activation of Wnt/β-catenin signalling in TNBC results in poor prognosis [44,45]. Knockdown of β-catenin in TNBC cells significantly decreased cell migration and made TNBC cells more sensitive to chemotherapeutic drugs like cisplatin and doxorubicin [46]. Highly conserved developmental transcription factor SOX4 (sex-determining region Y-box 4) plays a key role in Wnt signalling [47]. SOX4 knockdown has shown to decrease the migration and proliferation in TNBC. Wnt/β-catenin pathway inhibitor ICRT-3 has been reported to inhibit proliferation of TNBC cells [48]. LRP5 and LRP6 of the LDLR (low-density lipoprotein receptor) family are the essential co-receptors for Wnt/β-catenin signalling [43]. LRP6 is overexpressed in TNBC and its knockdown suppresses Wnt/β-catenin signalling in vivo. Thus, LRP6 can act as a potential therapeutic target in the treatment of TNBC [49]. To activate Wnt/β-catenin signalling, Wnt binds to both FZD (Frizzled) proteins and LRP5/6. It has been demonstrated that FZD 7 was overexpressed in TNBC and its suppression inactivates Wnt/β-catenin pathway [50]. Secreted glycoproteins like WIF1 and FZD are reported to act as Wnt antagonists. Both the proteins inhibit the interaction of Wnt with FZD receptor hindering the transcription of activated genes by β-catenin/TCF/LEF transcriptional complex [43]. Recently, it has been reported that salinomycin induces degradation of Wnt co-receptor LRP6 [51,52] and also has potential to inhibit the breast cancer cell proliferation [43].

Hh (Hedgehog) signalling dysregulation confers aggressive TNBC phenotype and enhances the invasion, migration and metastatic potential of TNBC cells [53,54]. Previous clinical studies highlighted the key role of Hh signalling in cancer stem cell reprogramming and EMT (epithelial-to-mesenchymal) in TNBC [55,56]. The Hh pathway is associated with embryonic patterning and mediates stem cell renewal by activating the expression of BMI-1, a potent regulator of self-renewal in cancer stem cells [57]. It involves three ligands – IHH (Indian Hedhehog), SHH (Sonic Hedgehog) and DHH (Desert Hedgehog); Transmembrane receptor, PTCH ( Patched) and co-receptor, SMO (Smoothened) [58]. There are three glioma-associated oncogenes (GLI) transcription factors, GLI1, GLI2 and GLI3. However, GLI1 and GLI2 are the most studied ones and responsible for cell proliferation and survival [59]. SMO is the most pharmacologically targeted pathway in TNBC. Various SMO inhibitors were clinically tested and few gave the positive response as Hh antagonists (NCT01071564, NCT02027376 and NCT01757327) [60]. However, in preclinical studies, resistance to these Hh antagonists was observed in TNBC. Thus, a rationale for the GLI-targeted approach was suggested [61]. So far, numerous direct and indirect GLI inhibitors have been clinically tried like GANT61, GANT58 and Glabrescione B (GLaB). These drugs interfere with GLI DNA binding by inhibiting the output of transcription in Hh signalling pathway [62].

The Notch signalling pathway is a much conserved signalling pathway that is mediated by four receptors (NOTCH 1–4) and five ligands (Δ-like 1,3,4 and JAGGED-1,2) [63–66]. Cell–cell contact is a key factor to activate the NOTCH signalling pathway [67]. The signalling cascade is activated by the release of Notch receptor intracellular domain (NICD) with a series of proteolytic cleavage facilitated by γ-secretase [68]. Irregular activation of Notch signalling cascade could initiate malignancies and promote angiogenesis [69]. Previous studies reported that GSI (γ-secretase inhibitors) play a significant role in blocking the Notch signalling pathway [70]. Therefore, numerous preclinical studies have been done on GSI-directed therapy. Researchers confirmed that NOTCH-1 exert a strong influence on tumour proliferation and metastasis. The increased expression of NOTCH-1 has been observed in TNBC that lead to malignancies and poor prognosis [71]. However, it has been recently discovered that NOTCH-4 also plays a pivotal role in the initiation of TNBC and induction of proliferation and tumorigenesis [72]. Targeting NOTCH signalling cascade with GSIs and other drugs should be meticulously explored to increase the survival rate of TNBC patients.

Receptor-mediated targeting

RTKs (receptor tyrosine kinases) regulate cell growth and metabolism, proliferation and differentiation, cell survival and apoptosis [73]. The therapeutic targets of TNBC in RTK family are VEGFR (vascular endothelial growth factor receptor) [74], PDGFR (platelet-derived growth factor receptor) [75], TGFβR (TGFβ receptor) [76,77], FGFR [78], EGFR (epidermal growth factor receptor) [79,80] and IGF-1R (insulin-like growth factor-1 receptor) [81].

EGFR, also known as HER1 is overexpressed in basal-like cells [80]. EGFR-TKI (tyrosine kinase inhibitor) erlotinib, showed a change in mesenchymal phenotype to epithelial phenotype by up-regulating E-cadherin and down-regulating Vimentin in TNBC cells [82]. Several other EGFR inhibiting agents like panitumumab, cetuximab, gefitinib have shown initial success but failed to produce significant results in clinical studies [83]. Sunitinib is a small-molecule kinase inhibitor, which inhibits both PDGF family and VEGF have shown to reduce tumour volume in xenograft models of TNBC [84]. Bevacizumab reduced progression of metastatic TNBC in 35% of patients in a meta-analysis of Phase III clinical trials [85].

Epigenetic therapies

It is widely believed that aberrant epigenetic changes in histone deacetylation and DNA hypermethylation may lead to silencing of tumour suppressor genes and drive tumorigenesis in cancer cells [86]. A detailed study of DNA methylation signatures using TCGA (The Cancer Genome Atlas) data helped in the separation of TNBC cells from non-TNBC cells. These data helped in the prognosis of patients by categorizing into poor, medium and good outcomes [87]. The first study showed methylation of a BRCA1 promoter in TNBC and few other studies investigated the role of BRCA1 methylation in TNBC. They also found that BRCA1 methylation increases the sensitivity of TNBC cells towards PARP inhibitors [88]. Another study has found that decreased expression of pRb and increased expression of p76 is associated with BRCA1 [89].

DNA hypermethylation decreases expression of tumour suppressor genes. A study revealed that inhibition of STAT3-DNMT1 (DNA methyltransferase 1) at K685 residue by novel inhibitor SH-I-14 has shown to demethylate the promoter regions of tumour suppressor genes and re-expressed PDLIM4 and VHL genes [90]. A study performed on whole-genome methyl CpG binding domain based capture sequencing (MBDCap-Seq) on TNBC tumours and found 36 differentially methylated regions (DMRs) which showed increased hypermethylation specifically in TNBC cells when compared with non-TNBC samples [91]. BRD4 is a BET (bromodomain and extra terminal) protein family member, regulates mitosis and cell cycle progression [92,93]. BRD4 inhibition has shown to suppress important oncogenic drivers [94]. BETi (BET inhibitor) showed direct inhibition of mitotic regulating proteins AURKA/B in TNBC cells and thereby suppressing tumour growth [95]. BETi JQ1 targeted hypoxic inducing genes and angiogenesis dually in TNBC cells [96]. ID4 (inhibitor of differentiation) protein is highly expressed in TNBC cells and down-regulates BRCA1 pathways [97] and exhibits anchorage-independent growth of breast cancer cells [98]. ID4 promoter hypermethylation is known to increase lymph node metastasis [99]. A study also revealed that ID4 and BRCA1 expression are inversely related and unmethylation of ID4 is associated with BRCAness of breast cancer cells [100]. PKD1 (protein kinase D1) encoded by PRKD1 gene is abnormally methylated and silenced in invasive breast cancer cells. DNMT inhibitor decitabine reverses PRKD1 promoter methylation and restores PKD1 expression and suppresses lung metastasis in animal models [101].

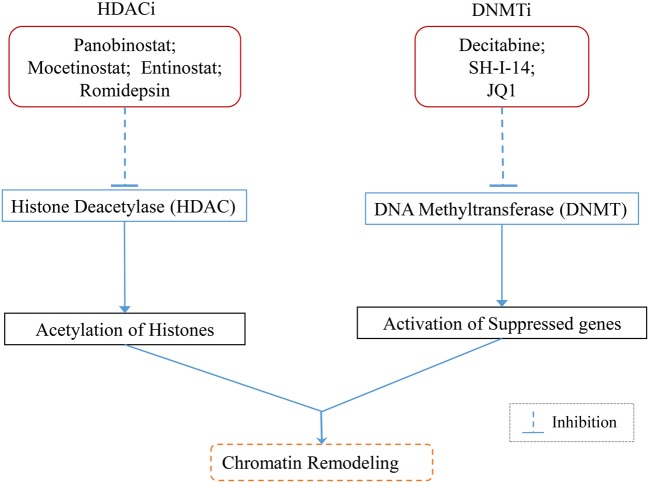

Another promising epigenetic target for TNBC are HDACi (HDAC inhibitors). HDACi entinostat reduces binding of twist and snail to the CDH-1 promoter, increasing E-cadherin and cytokeratin 8/18 expression and decreasing N-cadherin expression thereby reversing EMT phenotype [102]. Entinostat decreases the expression of CD44high/CD24low and markers of TICs (tumour-initiating cells) such as β-catenin, Bmi-1, Nanog, Oct-4 and also reduces mammosphere formation [103]. Romidepsin alone or in combination with paclitaxel removed metastatic lesions and primary tumours in TNBC cells [104]. A potent HDACi Panobinostat decreases cell proliferation, survival, induced apoptosis and inhibits tumour formation in TNBC cells [105]. Another study showed that LBH589 (Panobinostat) inhibits metastasis in TNBC cells mediated by inhibition of ZEB (zinc finger E-box-binding homoeobox) [106] (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the mechanism of epigenetic inhibitors in TNBC.

Aberrant epigenetic changes like histone deacetylation and DNA hypermethylation are associated with silencing of tumour suppressor genes and drive tumorigenesis. Epigenetic inhibitors like Panobinostat; Mocetinostat; Entinostat; Romidepsin inhibit histone deacetylase and promote acetylation of histones leading to transcriptionally active chromatin. DNMT inhibitors Decitabine; SH-I-14; JQ1 help to inhibit DNMT to reactivate suppressed genes.

Cancer cells disseminate to distant sites by transforming EMT phenotype, which is characterized by loss of E-cadherin expression. TICs which are found in tumour tissues exhibit self-renewing stem cell properties and they also have the ability to grow into a tumour in mice when inoculated at very low numbers [107]. Studies have shown that cancer cells activating EMT acquire TIC’s properties expressing CD44high/CD24low markers [108–110].

Immunotherapies

In 2013, cancer immunotherapy was named as ‘Breakthrough of the year’ by science magazine [111]. TILs (tumour-infiltrating lymphocytes) are long known to be associated with breast cancer prognosis. The prognostic and predictive values vary between subtypes of breast cancer. Studies showed that TILs highly prevailed in TNBC and were less abundant in other types of breast cancer [112]. TILs are prognostic markers for high OS, increased metastasis-free survival and decreased distant recurrence [113,114]. Stromal TILs are correlated with immunological markers like indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO1), CD8α, CCL5 (chemokine (C–C motif) ligand 5) and PD-L1 (programmed cell death ligand-1) to significantly increase pCR rates in chemotherapy [115]. Trop-2 (trophoblast cell-surface antigen) is expressed on multiple solid cancers and found to be a novel target for antibody-mediated drug conjugate (ADC) therapy [116]. IMMU-132 is an ADC, delivers topoisomerase-I inhibitor (SN-38) in its most active (non-glucuronidated) form targeting Trop-2 in TNBC [117].

Immune checkpoints are the molecules of inhibitory pathways in the immune system which play a major role in preventing autoimmunity [118]. Activated CD8+ T cells express inhibitory cytotoxic receptor T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4 (CTLA-4), counteracts the activity of co-stimulatory receptor CD28 and attenuates immune response [119]. Ipilimumab is a monoclonal antibody that targets CTLA-4 to activate T cells and thereby increasing proliferation of T cells and potentiates antitumour immune response [120]. Another ‘immune checkpoint’ blockade is PD-1 (programmed cell death 1), a T-cell transmembrane receptor expressed on CD8+ T cells. Up-regulation of PD-1 ligands (PD-L1 or PD-L2) blocks T-cell immune response in the tumour microenvironment [121]. Pembrolizumab, a potent inhibitor of PD-1 showed antitumour activity and overall response rate (ORR) of 18.5% in TNBC patients [122] (Figure 3). Other antibodies to take the ‘brakes off’ T cells to increase the antitumour immune response are under investigation and the current immunotherapy clinical trials are listed in Table 1 (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Illustration of immunotherapeutic response in TNBC.

PD-1 and CTLA-4 are immune checkpoints that prevent immune response towards cancer cells. PD-1 immune checkpoint inhibitors like Permbrolizumab; Durvalumab; Azetolimumab and CTLA-4 inhibitors like Ipilimumab; Tremelimumab inhibit checkpoints and take the ‘brakes off’ T cells thereby activating immune response to attack cancer cells. IMMU-132 is an antibody–drug conjugate delivering topoisomerase I inhibitor (SN-38) targeting Trop-2 receptors on cancer cells.

Table 1. Recent clinical trials investigating potential therapeutic targets using combinational drug therapy strategy for the treatment of TNBC.

| Primary drugs | Molecules targeted | Combinatorial drugs | Molecules targeted | Trial reference | Clinical phase | Estimated completion |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Everolimus | mTOR | Eribulin | Microtubules | NCT02616848 | Phase I | November 2015 |

| MLN0128 | mTOR | MLN8237 | Aurora A | NCT02719691 | Phase I | November 2018 |

| L-NMMA | Nitric oxide synthase | Docetaxel | Microtubules | NCT02834403 | Phase I | August 2019 |

| Trilaciclib | CDK4/6 inhibitor | Carboplatin; gemcitabine | DNA damage; nucleosides | NCT02978716 | Phase II | December 2019 |

| Ixazomib | Proteasome subunit β-5 | Carboplatin | DNA damage | NCT02993094 | Phase I/II | September 2019 |

| Selumetinib | MAPK/ERK | Docetaxel; doxobicin; cyclophosphamide | Microtubules; DNA damage | NCT02685657 | Phase II | January 2018 |

| Doxorubicin | DNA | Everolimus; bevacizumab | mTOR; VEGF | NCT02456857 | Phase II | January 2019 |

| ARQ 092 | PI3K/AKT | Carboplatin + paclitaxel/paclitaxel/ anastrozole | DNA damage; tubulin; aromatase | NCT02476955 | Phase I | December 2017 |

| Eribulin | Microtubules | PQR309 | PI3K/mTOR | NCT02723877 | Phase I/II | December 2018 |

| Ruxolitinib | JAK | Paclitaxel; doxobicin; cyclophosphamide | Tubulin; DNA damage | NCT02876302 | Phase II | February 2024 |

| Galunisertib | TGF-β | Paclitaxel | Tubulin | NCT02672475 | Phase I | January 2020 |

| Vismodegib | SMO (Hh pathway) | Paclitaxel; epirubicin; cyclophosphamide | Tubulin; DNA damage | NCT02694224 | Phase II | December 2018 |

| Enzalutamide | Androgen receptor | Paclitaxel | Tubulin | NCT02929576 | Phase III | April 2019 |

| Panitumumab | EGFR | Carboplatin; paclitaxel | DNA repair; tubulin | NCT02593175 | Phase II | August 2018 |

| Paclitaxel | Tubulin | Afatinib | EGFR | NCT02511847 | Phase II | July 2017 |

| Pemetrexed | Nucleotides | Sorafenib | VEGFR, PDGFR | NCT02624700 | Phase II | December 2019 |

| Cediranib | VEGF | Olaparib | PARP | NCT02498613 | Phase II | May 2018 |

| Cisplatin | DNA damage | Veliparib | PARP | NCT02595905 | Phase II | October 2021 |

| Docetaxel | Microtubules | Carboplatin | DNA damage | NCT02547987 | Phase II | September 2020 |

| Paclitaxel | Tubulin | Bavituximab | Phosphatidyl-serine | NCT02685306 | Phase II | September 2017 |

| Paclitaxel | Tubulin | AT13387 | Hsp90 | NCT02474173 | Phase I | March 2017 |

| Romidepsin | HDAC | Cisplatin | DNA damage | NCT02393794 | Phase I/II | December 2018 |

| PDR001 | PD-1 | LCL161; everolimus or panobinostat | mTOR/HDAC | NCT02890069 | Phase I | October 2018 |

| Nivolumab | PD-1 | Doxorubicin; cyclophosphamide; cisplatin | DNA damage | NCT02499367 | Phase II | August 2022 |

| Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | Carboplatin; gemcitabine | DNA damage; nucleosides | NCT02755272 | Phase II | April 2023 |

| Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | Imprime PGG | B-cell receptor | NCT02981303 | Phase II | September 2019 |

| Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | Nab-paclitaxel; doxorubicin; cyclophosphamide; carboplatin | Tubulin; DNA damage | NCT02622074 | Phase I | August 2017 |

| Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | Cyclophosphamide | DNA damage | NCT02768701 | Phase II | December 2022 |

| Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | Nab-paclitaxel; paclitaxel; gemcitabine; carboplatin | Tubulin; DNA damage; nucleosides | NCT02819518 | Phase III | December 2019 |

| Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | INCB039110; INCB050465 | JAK; PI3K/AKT | NCT02646748 | Phase I | December 2017 |

| Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | Nab-paclitaxel | Tubulin | NCT02752685 | Phase II | December 2018 |

| Eribulin mesylate | Microtubules | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | NCT02513472 | Phase I/II | January 2018 |

| Niraparib | PARP | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | NCT02657889 | Phase I/II | February 2019 |

| Paclitaxel; capecitabine | Tubulin; nucleotides | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | NCT02734290 | Phase I/II | May 2022 |

| Enoblituzumab | B7-H3 | Pembrolizumab | PD-1 | NCT02475213 | Phase I | August 2020 |

| MCS110 | M-CSF | PDR001 | PD-1 | NCT02807844 | Phase I/II | February 2019 |

| BLZ945 | CSF-1R | PDR001 | PD-1 | NCT02829723 | Phase I/II | June 2019 |

| MPDL3280A | PD-L1 | Nab-paclitaxel | Tubulin | NCT02530489 | Phase II | February 2021 |

| MPDL3280A | PD-L1 | Carboplatin; abraxane | DNA damage; Tubulin | NCT02620280 | Phase III | May 2022 |

| Durvalumab | PD-L1 | Vigil | T cells | NCT02725489 | Phase II/III | May 2018 |

| Durvalumab | PD-L1 | Nab-paclitaxel; epirubicin; cyclophosphamide | Tubulin; DNA damage | NCT02685059 | Phase II | March 2018 |

| Durvalumab | PD-L1 | Olaparib; cediranib | PARP; VEGF | NCT02484404 | Phase I/II | December 2019 |

| Atezolizumab | PD-L1 | Carboplatin; paclitaxel | DNA damage; tubulin | NCT02883062 | Phase II | September 2019 |

| Veliparib | PARP | Atezolizumab | PD-L1 | NCT02849496 | Phase II | August 2018 |

| Nab-paclitaxel | Tubulin | Atezolizumab | PD-L1 | NCT02425891 | Phase III | April 2020 |

| Entinostat | HDAC | Atezolizumab | PD-L1 | NCT02708680 | Phase I/II | June 2019 |

| Varlilumab | CD-27 | Atezolizumab | PD-L1 | NCT02543645 | Phase I/II | June 2019 |

| Nab-paclitaxel | Tubulin | MPD3280A | PD-L1 | NCT02530489 | Phase II | February 2021 |

| Durvalumab | PD-L1 | Nab-paclitaxel; dose-dense doxorubicin/cyclophosphamide | Tubulin; DNA/RNA damage | NCT02489448 | Phase I/II | October 2019 |

| Tremelimumab | CTLA-4 | Durvalumab | PD-L1 | NCT02527434 | Phase II | April 2018 |

| Enoblituzumab | B7-H3 | Ipilimumab | CTLA-4 | NCT02381314 | Phase I | March 2018 |

| Carboplatin; Gemcitabine | DNA damage; nucleosides | MCS110 | M-CSF | NCT02435680 | Phase II | March 2019 |

Details provided in the table include only recent clinical trials which are first received on or after 01/01/2015.

Combined drug therapy strategies

Although the single-agent therapy has shown positive results in cell lines and preclinical models but failed to get promising results in clinical trials to counter aggressive TNBC, owing to its heterogeneity and acquired drug resistance. Combined drug therapy (CDT) is rapidly gaining popularity and proving to be effective in current clinical trials towards improving pCR, PFS and OS in various cancers. At present, almost 80% of the clinical trials are using combinatorial drugs to investigate new therapeutic strategies for TNBC treatment. CDT strategies in current clinical trials data are provided (Table 1).

Recently, CDT strategy has been widely used for immunotherapy checkpoint inhibitors to target TNBC effectively. Tremelimumab (CTLA-4i) in combination with duralumin (PD-L1i) is under investigation in Phase II clinical trials (NCT02527434). The effective way of planning combinational strategy is through prediction of effective targets connected to signalling networks that drive cancer progression. Systems biology provided attractive tools to strategize network-based therapies for cancer. Using these tools, a study group identified five most effective and connected targets (VIM, YWHAB, TK1, CSNK2B and HSP90AB1) in TNBC cells. Initially, the targets were validated using cell-based assays. Based on initial results, using animal models they knocked out five targets in vivo and successfully inhibited colony formation, proliferation, migration, anchorage independence and invasion [123].

A study showed that combination of mTOR inhibitor rapamycin and doxorubicin-loaded cyclic octapeptide liposomes inhibited the expression of HIF-1α in TNBC cells [124]. Combined inhibition of PI3K/AKT/mTOR with chemotherapy showed substantial improvement in PFS of TNBC patients [125]. Other study showed that combined inhibition of CDK4/6 and PI3Kα has greatly increased tumour infiltrating T-cell activation in TNBC cells [126]. TNBC cells which expressed PTEN responded to PARP and HDACis. Combined inhibition of olaparib and SAHA in TNBC cells showed increased DNA damage, decreased proliferation, increased autophagy and apoptosis [127]. HDACi mocetinostat combinedly treated with BETi JQ1 showed synergistic suppression of cell cycle progression genes and induced apoptosis in TNBC cells [128].

Few randomized clinical trials showed that addition of HDACi to DNMTi did not improve the outcomes in the patients [129–131]. There is no conclusive evidence that epigenetic inhibitors function by epigenetic mechanisms. These results clearly indicate to reinvestigate how epigenetic drugs work and their mechanism of action [132].

Future directions

The recent study shows that knockdown of PRL-3 (phosphatase of regenerating liver 3) leads cancer cells to senescence. The experimental drug AMPI-109 inactivates PRL-3, making senescent cancer cells sensitive for immunotherapy treatment [133].

There is an increasing evidence indicating the role of PTEN in acquiring chemoresistance in MDR (multidrug resistant) breast cancer cells. Inhibition of miR-19 down-regulates multidrug resistance genes (MDR-1, MRP-1 and BCRP) and restores PTEN expression in MDR breast cancer cells, sensitizing cells to chemotherapeutic agents [134]. Up-regulation of PTEN activity increases the effectiveness of chemotherapy and in combination with ID4 (DNA binding protein inhibitor) can be studied for the effective treatment of TNBC. One of the studies suggested that combination therapy of lapatinib (NF-κB inhibitor) with a proteasome inhibitor may prove to be an effective treatment for TNBC [135].

A study published in 2011, shows that anti-oestrogens or aromatase inhibitors increase the population of ER-negative cells in luminal breast cancer cells thereby increasing resistance to the treatment [136]. This study led to the findings that inhibiting Notch-1 in luminal breast cancers maintains the ER positive state for the effective targeting of ER-based therapies. It is also found that inhibiting Notch-1 can transform ER−/PR−/CK5+ cells to ER+ cells [137]. Therefore, Notch-1 inhibitors like GSI in combination with endocrine therapies can be used as CDT strategy for TNBC treatment.

Several other chemotherapy drugs, epigenetic inhibitors, immunotherapies and combinational therapies showing positive results in vitro should be immediately carried over to clinical trials to determine the effectiveness of the drugs in vivo. As there is an urgent need to find out therapeutic targets for TNBC, we need to explore the new biomarkers and signalling pathways which help in early diagnosis of cancer and finding new therapeutic targets for effective treatment of TNBC.

Conclusion

Despite the fact that combined therapeutic strategies are proven to be effective in various cancers including TNBC, there are few exemptions where some of the valid hypotheses and in vitro results are shown to be ineffective when translated into clinical trials. TNBC is a heterogeneous cancer with varying physiological and pathological characteristics and associated with the aggressive phenotype. So, despite the emergence of various therapeutic strategies for the treatment of TNBC, the effective treatment can be provided by selecting suitable combinational therapy by considering patient-specific molecular characteristics, biomarkers, clinical and pathological features through proper diagnosis.

Abbreviations

- BET

bromodomain and extra terminal

- BETi

BET inhibitor

- CDT

combined drug therapy

- CTLA-4

cytotoxic receptor T-lymphocyte associated antigen 4

- DNMT

DNA methyltransferase

- EGFR

epidermal growth factor receptor

- EMT

epithelial-to-mesenchymal

- FGFR

fibroblast growth factor receptor

- FZD

frizzled protein

- GLI

glioma-associated oncogene

- GSI

γ-secretase inhibitor

- HDACi

HDAC inhibitor

- Hh

hedgehog

- ID4

inhibitor of differentiation

- MDR

multidrug resistant

- OS

overall survival

- pCR

pathological clinical response

- PD-1

programmed cell death 1

- PD-L1

programmed cell death ligand-1

- PFS

progression-free survival

- PKD1

protein kinase D1

- PRL-3

phosphatase of regenerating liver 3

- RTK

receptor tyrosine kinase

- SMO

smoothened

- SOX4

sex-determining region Y-box 4

- TIC

tumour-initiating cell

- TIL

tumour-infiltrating lymphocyte

- TNBC

triple negative breast cancer

- Trop-2

trophoblast cell-surface antigen

Competing interests

The authors declare that there are no competing interests associated with the manuscript.

Author contribution

S.B.P. was responsible for the conception, synthesis and drafting of the article. N.K.R. C.-R. was responsible for the data/literature collection and for the data analysis and interpretation.

Funding

This work was supported by the Science and Engineering Research Board (SERB) [grant number SB/YS/LS-57/2014 (to S.B.P.)].

References

- 1.Ferlay J., et al. (2015) Cancer incidence and mortality worldwide: sources, methods and major patterns in GLOBOCAN 2012. Int. J. Cancer 136, E359–E386 10.1002/ijc.29210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gajulapalli V.N.R., et al. (2016) Oestrogen receptor negativity in breast cancer: a cause or consequence ? Biosci. Rep. 36, e00432 10.1042/BSR20160228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Polyak K. (2011) Heterogeneity in breast cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 3786 10.1172/JCI60534 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kaur P., et al. (2012) A mouse model for triple-negative breast cancer tumor-initiating cells (TNBC-TICs) exhibits similar aggressive phenotype to the human disease. BMC Cancer 12, 120 10.1186/1471-2407-12-120 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Irvin W.J. and Carey L.A. (2008) What is triple-negative breast cancer? Eur. J. Cancer 44, 2799–2805 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.09.034 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Blows F.M., et al. (2010) Subtyping of breast cancer by immunohistochemistry to investigate a relationship between subtype and short and long term survival: a collaborative analysis of data for 10,159 cases from 12 studies. PLoS Med. 7, e1000279 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000279 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sharma P. (2016) Biology and management of patients with triple-negative breast cancer. Oncologist 21, 10.1634/theoncologist.2016-0067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lips E., et al. (2013) Triple-negative breast cancer: BRCAness and concordance of clinical features with BRCA1-mutation carriers. Br. J. Cancer 108, 2172–2177 10.1038/bjc.2013.144 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sharma P., et al. (2014) The prognostic value of BRCA1 promoter methylation in early stage triple negative breast cancer. J. Cancer Ther. Res. 3, 1–11 10.7243/2049-7962-3-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sharma P., et al. (2014) Germline BRCA mutation evaluation in a prospective triple-negative breast cancer registry: implications for hereditary breast and/or ovarian cancer syndrome testing. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 145, 707–714 10.1007/s10549-014-2980-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gonzalez-Angulo A.M., et al. (2011) Incidence and outcome of BRCA mutations in unselected patients with triple receptor-negative breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 1082–1089 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hartman A.R., et al. (2012) Prevalence of BRCA mutations in an unselected population of triple‐negative breast cancer. Cancer 118, 2787–2795 10.1002/cncr.26576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lehmann B.D., et al. (2011) Identification of human triple-negative breast cancer subtypes and preclinical models for selection of targeted therapies. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 2750–2767 10.1172/JCI45014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kreike B., et al. (2007) Gene expression profiling and histopathological characterization of triple-negative/basal-like breast carcinomas. Breast Cancer Res. 9, R65 10.1186/bcr1771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Carey L.A., et al. (2006) Race, breast cancer subtypes, and survival in the Carolina Breast Cancer Study. JAMA 295, 2492–2502 10.1001/jama.295.21.2492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ossovskaya V., et al. (2011) Exploring molecular pathways of triple-negative breast cancer. Genes Cancer 2, 870–879 10.1177/1947601911432496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fan Y., et al. (2008) Regulation of programmed cell death by NF-κB and its role in tumorigenesis and therapy. In Programmed Cell Death in Cancer Progression and Therapy, pp. 223–250, Springer; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gilmore T. and Herscovitch M. (2006) Inhibitors of NF-κB signaling: 785 and counting. Oncogene 25, 6887–6899 10.1038/sj.onc.1209982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pan H., et al. (2012) Genistein inhibits MDA-MB-231 triple-negative breast cancer cell growth by inhibiting NF-κB activity via the Notch-1 pathway. Int. J. Mol. Med. 30, 337–343 10.3892/ijmm.2012.990 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ahmad A., et al. (2008) Plumbagin‐induced apoptosis of human breast cancer cells is mediated by inactivation of NF‐κB and Bcl‐2. J. Cell. Biochem. 105, 1461–1471 10.1002/jcb.21966 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li T., et al. (2014) Fenofibrate induces apoptosis of triple-negative breast cancer cells via activation of NF-κB pathway. BMC Cancer 14, 96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Furth P.A. (2014) STAT signaling in different breast cancer sub-types. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 382, 612–615 10.1016/j.mce.2013.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wei W., et al. (2014) STAT3 signaling is activated preferentially in tumor‐initiating cells in claudin‐low models of human breast cancer. Stem Cell 32, 2571–2582 10.1002/stem.1752 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shields B.J., et al. (2013) TCPTP regulates SFK and STAT3 signaling and is lost in triple-negative breast cancers. Mol. Cell. Biol. 33, 557–570 10.1128/MCB.01016-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Deng X.-S., et al. (2012) Metformin targets Stat3 to inhibit cell growth and induce apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancers. Cell Cycle 11, 367–376 10.4161/cc.11.2.18813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrison C. (2015) JAK inhibitors and myelofibrosis, Einstein and ruxolitinib. Haematologica 100, 409–411 10.3324/haematol.2015.124099 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Balko J.M., et al. (2016) Triple-negative breast cancers with amplification of JAK2 at the 9p24 locus demonstrate JAK2-specific dependence. Sci. Transl. Med. 8, 334ra353 10.1126/scitranslmed.aad3001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Massihnia D., et al. (2016) Triple negative breast cancer: shedding light onto the role of pi3k/akt/mtor pathway. Oncotarget 10.18632/oncotarget.10858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gordon V. and Banerji S. (2013) Molecular pathways: PI3K pathway targets in triple-negative breast cancers. Clin. Cancer Res. 19, 3738–3744 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-12-0274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gewinner C., et al. (2009) Evidence that inositol polyphosphate 4-phosphatase type II is a tumor suppressor that inhibits PI3K signaling. Cancer Cell 16, 115–125 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fruman D.A. and Rommel C. (2014) PI3K and cancer: lessons, challenges and opportunities. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 140–156 10.1038/nrd4204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lauring J., et al. (2013) The phosphoinositide-3-kinase-Akt-mTOR pathway as a therapeutic target in breast cancer. J. Natl. Compr. Cancer Netw. 11, 670–678 10.6004/jnccn.2013.0086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Park J.-H., et al. (2016) PI3K/Akt/mTOR activation by suppression of ELK3 mediates chemosensitivity of MDA-MB-231 cells to doxorubicin by inhibiting autophagy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 10.1016/j.bbrc.2016.06.057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Juvekar A., et al. (2012) Combining a PI3K inhibitor with a PARP inhibitor provides an effective therapy for BRCA1-related breast cancer. Cancer Discov. 2, 1048–1063 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ibrahim Y.H., et al. (2012) PI3K inhibition impairs BRCA1/2 expression and sensitizes BRCA-proficient triple-negative breast cancer to PARP inhibition. Cancer Discov. 2, 1036–1047 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0348 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kimbung S., et al. (2012) Co-targeting of the PI3K pathway improves the response of BRCA1 deficient breast cancer cells to PARP1 inhibition. Cancer Lett. 319, 232–241 10.1016/j.canlet.2012.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Yunokawa M., et al. (2012) Efficacy of everolimus, a novel mTOR inhibitor, against basal‐like triple‐negative breast cancer cells. Cancer Sci. 103, 1665–1671 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2012.02359.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bhola N.E., et al. (2016) Treatment of triple-negative breast cancer with TORC1/2 inhibitors sustains a drug-resistant and notch-dependent cancer stem cell population. Cancer Res. 76, 440–452 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-1640-T [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mayer I., et al. (2013) Abstract PD1-6: a randomized phase II neoadjuvant study of cisplatin, paclitaxel with or without everolimus (an mTOR inhibitor) in patients with stage II/III triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC). Cancer Res. 73, PD1–6 10.1158/0008-5472.SABCS13-PD1-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gonzalez-Angulo A., et al. (2014) Open-label randomized clinical trial of standard neoadjuvant chemotherapy with paclitaxel followed by FEC versus the combination of paclitaxel and everolimus followed by FEC in women with triple receptor-negative breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 25, 1122–1127 10.1093/annonc/mdu124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Jerusalem G., et al. (2014) Use of mTOR inhibitors in the treatment of breast cancer: an evaluation of factors that influence patient outcomes. Breast Cancer 6, 43–57 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Howe L.R. and Brown A.M. (2004) Wnt signaling and breast cancer. Cancer Biol. Ther. 3, 36–41 10.4161/cbt.3.1.561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.MacDonald B.T., et al. (2009) Wnt/β-catenin signaling: components, mechanisms, and diseases. Dev. Cell 17, 9–26 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.06.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khramtsov A.I., et al. (2010) Wnt/β-catenin pathway activation is enriched in basal-like breast cancers and predicts poor outcome. Am. J. Pathol. 176, 2911–2920 10.2353/ajpath.2010.091125 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barker N. and Clevers H. (2006) Mining the Wnt pathway for cancer therapeutics. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 5, 997–1014 10.1038/nrd2154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Xu J., et al. (2015) β-Catenin is required for the tumorigenic behavior of triple-negative breast cancer cells. PLoS ONE 10, e0117097 10.1371/journal.pone.0117097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Scharer C.D., et al. (2009) Genome-wide promoter analysis of the SOX4 transcriptional network in prostate cancer cells. Cancer Res. 69, 709–717 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3415 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bilir B., et al. (2013) Wnt signaling blockage inhibits cell proliferation and migration, and induces apoptosis in triple-negative breast cancer cells. J. Transl. Med. 11, 280 10.1186/1479-5876-11-280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Liu C.-C., et al. (2010) LRP6 overexpression defines a class of breast cancer subtype and is a target for therapy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 5136–5141 10.1073/pnas.0911220107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang L., et al. (2011) FZD7 has a critical role in cell proliferation in triple negative breast cancer. Oncogene 30, 4437–4446 10.1038/onc.2011.145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lu D., et al. (2011) Salinomycin inhibits Wnt signaling and selectively induces apoptosis in chronic lymphocytic leukemia cells. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 13253–13257 10.1073/pnas.1110431108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Tang Q.-L., et al. (2011) Salinomycin inhibits osteosarcoma by targeting its tumor stem cells. Cancer Lett. 311, 113–121 10.1016/j.canlet.2011.07.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kwon Y.-J., et al. (2011) Gli1 enhances migration and invasion via up-regulation of MMP-11 and promotes metastasis in ERα negative breast cancer cell lines. Clin. Exp. Metastasis 28, 437–449 10.1007/s10585-011-9382-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Harris L.G., et al. (2012) Increased vascularity and spontaneous metastasis of breast cancer by hedgehog signaling mediated upregulation of cyr61. Oncogene 31, 3370–3380 10.1038/onc.2011.496 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lei J., et al. (2015) Gli-1 is crucial for hypoxia-induced epithelial-mesenchymal transition and invasion of breast cancer. Tumour Biol. 36, 3119–3126 10.1007/s13277-014-2948-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sims‐Mourtada J., et al. (2015) Taxane‐induced hedgehog signaling is linked to expansion of breast cancer stem‐like populations after chemotherapy. Mol. Carcinog. 54, 1480–1493 10.1002/mc.22225 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yang N., et al. (2016) Inhibition of sonic hedgehog signaling pathway by thiazole antibiotic thiostrepton attenuates the CD44+/CD24-stem-like population and sphere-forming capacity in triple-negative breast cancer. Cell. Physiol. Biochem. 38, 1157–1170 10.1159/000443066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sasai N. and Briscoe J. (2012) Primary cilia and graded Sonic Hedgehog signaling. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Dev. Biol. 1, 753–772 10.1002/wdev.43 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Alexandre C., et al. (1996) Transcriptional activation of hedgehog target genes in Drosophila is mediated directly by the cubitus interruptus protein, a member of the GLI family of zinc finger DNA-binding proteins. Genes Dev. 10, 2003–2013 10.1101/gad.10.16.2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Merchant A.A. and Matsui W. (2010) Targeting Hedgehog—a cancer stem cell pathway. Clin. Cancer Res. 16, 3130–3140 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-2846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kameda C., et al. (2009) The Hedgehog pathway is a possible therapeutic target for patients with estrogen receptor-negative breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 29, 871–879 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Lauth M., et al. (2007) Inhibition of GLI-mediated transcription and tumor cell growth by small-molecule antagonists. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 8455–8460 10.1073/pnas.0609699104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Lindsell C.E., et al. (1995) Jagged: a mammalian ligand that activates Notch1. Cell 80, 909–917 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90294-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shawber C., et al. (1996) Jagged2: a serrate-like gene expressed during rat embryogenesis. Dev. Biol. 180, 370–376 10.1006/dbio.1996.0310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Speiser J., et al. (2012) Notch-1 and Notch-4 biomarker expression in triple-negative breast cancer. Int. J. Surg. Pathol. 20, 137–143 10.1177/1066896911427035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Blaumueller C. and Artavanis-Tsakonas S. (1996) Comparative aspects of Notch signaling in lower and higher eukaryotes. Perspect. Dev. Neurobiol. 4, 325–343 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Callahan R. and Raafat A. (2001) Notch signaling in mammary gland tumorigenesis. J. Mammary Gland Biol. Neoplasia 6, 23–36 10.1023/A:1009512414430 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Bolós V., et al. (2007) Notch signaling in development and cancer. Endocr. Rev. 28, 339–363 10.1210/er.2006-0046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Phng L.-K. and Gerhardt H. (2009) Angiogenesis: a team effort coordinated by notch. Dev. Cell 16, 196–208 10.1016/j.devcel.2009.01.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Li Z.-L., et al. (2015) Gamma secretase inhibitor enhances sensitivity to doxorubicin in MDA-MB-231 cells. Int. J. Clin. Exp. Pathol. 8, 4378–4387 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bolós V., et al. (2013) Notch activation stimulates migration of breast cancer cells and promotes tumor growth. Breast Cancer Res. 15, R54 10.1186/bcr3447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Nagamatsu I., et al. (2014) NOTCH4 is a potential therapeutic target for triple-negative breast cancer. Anticancer Res. 34, 69–80 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zhang J. and Hochwald S.N. (2013) Targeting receptor tyrosine kinases in solid tumors. Surg. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 22, 685–703 10.1016/j.soc.2013.06.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Dent S. (2009) The role of VEGF in triple-negative breast cancer: where do we go from here? Ann. Oncol. 20, 1615–1617 10.1093/annonc/mdp410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Carvalho I., et al. (2005) Overexpression of platelet-derived growth factor receptor α in breast cancer is associated with tumour progression. Breast Cancer Res. 7, R788–R795 10.1186/bcr1304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bhola N.E., et al. (2013) TGF-β inhibition enhances chemotherapy action against triple-negative breast cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 123, 1348–1358 10.1172/JCI65416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Jovanović B., et al. (2014) Transforming growth factor beta receptor type III is a tumor promoter in mesenchymal-stem like triple negative breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. 16, R69 10.1186/bcr3684 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sharpe R., et al. (2011) FGFR signaling promotes the growth of triple-negative and basal-like breast cancer cell lines both in vitro and in vivo. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 5275–5286 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2727 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Song H., et al. (2013) Targeting aberrant DNA double-strand break repair in triple-negative breast cancer with alpha-particle emitter radiolabeled anti-EGFR antibody. Mol. Cancer Ther. 12, 2043–2054 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-13-0108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Corkery B., et al. (2009) Epidermal growth factor receptor as a potential therapeutic target in triple-negative breast cancer. Ann. Oncol. 20, 862–867 10.1093/annonc/mdn710 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Litzenburger B.C., et al. (2011) High IGF-IR activity in triple-negative breast cancer cell lines and tumorgrafts correlates with sensitivity to anti–IGF-IR therapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 2314–2327 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-1903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Ueno N.T. and Zhang D. (2011) Targeting EGFR in triple negative breast cancer. J. Cancer 2, 324–328 10.7150/jca.2.324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Amin D.N., et al. (2010) Resiliency and vulnerability in the HER2-HER3 tumorigenic driver. Sci. Transl. Med. 2, 16ra17–16ra17 10.1126/scitranslmed.3000389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Chinchar E., et al. (2014) Sunitinib significantly suppresses the proliferation, migration, apoptosis resistance, tumor angiogenesis and growth of triple-negative breast cancers but increases breast cancer stem cells. Vasc. Cell 6, 12 10.1186/2045-824X-6-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.O’Shaughnessy J., et al. (2010) Abstract P6-12-03: meta-analysis of patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) from three randomized trials of first-line bevacizumab (BV) and chemotherapy treatment for metastatic breast cancer (MBC). Cancer Res. 70, 10.1158/0008-5472.SABCS10-P6-12-03 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Jones P.A. and Baylin S.B. (2007) The epigenomics of cancer. Cell 128, 683–692 10.1016/j.cell.2007.01.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Stirzaker C., et al. (2015) Methylome sequencing in triple-negative breast cancer reveals distinct methylation clusters with prognostic value. Nat. Commun. 6, 10.1038/ncomms6899 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Veeck J., et al. (2010) BRCA1 CpG island hypermethylation predicts sensitivity to poly (adenosine diphosphate)-ribose polymerase inhibitors. J. Clin. Oncol. 28, e563–e564 10.1200/JCO.2010.30.1010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Stefansson O.A., et al. (2011) CpG island hypermethylation of BRCA1 and loss of pRb as co-occurring events in basal/triple-negative breast cancer. Epigenetics 6, 638–649 10.4161/epi.6.5.15667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Kang H.J., et al. (2015) Disruption of STAT3-DNMT1 interaction by SH-I-14 induces re-expression of tumor suppressor genes and inhibits growth of triple-negative breast tumor. Oncotarget 5, 10.18632/oncotarget.4054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Stirzaker C., et al. (2016) Genome-wide DNA methylation profiling in triple-negative breast cancer reveals epigenetic signatures with important clinical value. Mol. Cell. Oncol. 3, e1038424 10.1080/23723556.2015.1038424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Wu S.-Y. and Chiang C.-M. (2007) The double bromodomain-containing chromatin adaptor Brd4 and transcriptional regulation. J. Biol. Chem. 282, 13141–13145 10.1074/jbc.R700001200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Dey A., et al. (2000) A bromodomain protein, MCAP, associates with mitotic chromosomes and affects G2-to-M transition. Mol. Cell. Biol. 20, 6537–6549 10.1128/MCB.20.17.6537-6549.2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Lovén J., et al. (2013) Selective inhibition of tumor oncogenes by disruption of super-enhancers. Cell 153, 320–334 10.1016/j.cell.2013.03.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Sahni J.M., et al. (2016) Bromodomain and extraterminal protein inhibition blocks growth of triple-negative breast cancers through the suppression of Aurora kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 10.1074/jbc.M116.738666 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.da Motta L., et al. (2016) The BET inhibitor JQ1 selectively impairs tumour response to hypoxia and downregulates CA9 and angiogenesis in triple negative breast cancer. Oncogene, 10.1038/onc.2016.184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Wen Y.H., et al. (2012) Id4 protein is highly expressed in triple-negative breast carcinomas: possible implications for BRCA1 downregulation. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 135, 93–102 10.1007/s10549-012-2070-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Beger C., et al. (2001) Identification of Id4 as a regulator of BRCA1 expression by using a ribozyme-library-based inverse genomics approach. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 98, 130–135 10.1073/pnas.98.1.130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Umetani N., et al. (2005) Aberrant hypermethylation of ID4 gene promoter region increases risk of lymph node metastasis in T1 breast cancer. Oncogene 24, 4721–4727 10.1038/sj.onc.1208538 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Branham M., et al. (2016) Epigenetic regulation of ID4 in the determination of the BRCAness phenotype in breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 155, 13–23 10.1007/s10549-015-3648-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Borges S., et al. (2013) Pharmacologic reversion of epigenetic silencing of the PRKD1 promoter blocks breast tumor cell invasion and metastasis. Breast Cancer Res. 15, R66 10.1186/bcr3460 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Shah P., et al. (2014) Histone deacetylase inhibitor entinostat reverses epithelial to mesenchymal transition of breast cancer cells by reversing the repression of E-cadherin. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 143, 99–111 10.1007/s10549-013-2784-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Schech A., et al. (2015) Histone deacetylase inhibitor entinostat inhibits tumor-initiating cells in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Mol. Cancer Ther. 14, 1848–1857 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Robertson F.M., et al. (2013) The class I HDAC inhibitor Romidepsin targets inflammatory breast cancer tumor emboli and synergizes with paclitaxel to inhibit metastasis. J. Exp. Ther. Oncol. 10, 219–233 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Tate C.R., et al. (2012) Targeting triple-negative breast cancer cells with the histone deacetylase inhibitor panobinostat. Breast Cancer Res. 14, R79 10.1186/bcr3192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Rhodes L.V., et al. (2014) Suppression of triple-negative breast cancer metastasis by pan-DAC inhibitor panobinostat via inhibition of ZEB family of EMT master regulators. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 145, 593–604 10.1007/s10549-014-2979-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Reya T., et al. (2001) Stem cells, cancer, and cancer stem cells. Nature 414, 105–111 10.1038/35102167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Morel A.-P., et al. (2008) Generation of breast cancer stem cells through epithelial-mesenchymal transition. PLoS ONE 3, e2888 10.1371/journal.pone.0002888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Mani S.A., et al. (2008) The epithelial-mesenchymal transition generates cells with properties of stem cells. Cell 133, 704–715 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Scheel C. and Weinberg R.A. (2012) Cancer stem cells and epithelial–mesenchymal transition: concepts and molecular links, Semin. Cancer Biol. 22, 396–403 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Couzin-Frankel J. (2013) Cancer immunotherapy. Science 342, 1432–1433 10.1126/science.342.6165.1432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Pusztai L., et al. (2016) New strategies in breast cancer: immunotherapy. Clin. Cancer Res. 22, 2105–2110 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-1315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Loi S., et al. (2014) Tumor infiltrating lymphocytes are prognostic in triple negative breast cancer and predictive for trastuzumab benefit in early breast cancer: results from the FinHER trial. Ann. Oncol. 25, 1544–1550 10.1093/annonc/mdu112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Adams S., et al. (2014) Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in triple-negative breast cancers from two phase III randomized adjuvant breast cancer trials: ECOG 2197 and ECOG 1199. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 2959–2966 10.1200/JCO.2013.55.0491 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Denkert C., et al. (2015) Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and response to neoadjuvant chemotherapy with or without carboplatin in human epidermal growth factor receptor 2–positive and triple-negative primary breast cancers. J. Clin. Oncol. 33, 983–991 10.1200/JCO.2014.58.1967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Cardillo T.M., et al. (2011) Humanized anti-Trop-2 IgG-SN-38 conjugate for effective treatment of diverse epithelial cancers: preclinical studies in human cancer xenograft models and monkeys. Clin. Cancer Res. 17, 3157–3169 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-10-2939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Goldenberg D.M., et al. (2015) Trop-2 is a novel target for solid cancer therapy with sacituzumab govitecan (IMMU-132), an antibody-drug conjugate (ADC). Oncotarget 6, 22496 10.18632/oncotarget.4318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Pardoll D.M. (2012) The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Cancer 12, 252–264 10.1038/nrc3239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Krummel M.F. and Allison J.P. (1995) CD28 and CTLA-4 have opposing effects on the response of T cells to stimulation. J. Exp. Med. 182, 459–465 10.1084/jem.182.2.459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Robert C., et al. (2011) Ipilimumab plus dacarbazine for previously untreated metastatic melanoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 2517–2526 10.1056/NEJMoa1104621 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Schalper K.A., et al. (2014) In situ tumor PD-L1 mRNA expression is associated with increased TILs and better outcome in breast carcinomas. Clin. Cancer Res. 20, 2773–2782 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-2702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Nanda R., et al. (2016) Pembrolizumab in patients with advanced triple-negative breast cancer: phase Ib KEYNOTE-012 Study. J. Clin. Oncol., 10.1200/JCO.2015.64.8931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Tilli T.M., et al. (2016) Validation of a network-based strategy for the optimization of combinatorial target selection in breast cancer therapy: siRNA knockdown of network targets in MDA-MB-231 cells as an in vitro model for inhibition of tumor development. Oncotarget 7, 63189–63203 10.18632/oncotarget.11055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Dai W., et al. (2014) Combined mTOR inhibitor rapamycin and doxorubicin-loaded cyclic octapeptide modified liposomes for targeting integrin α3 in triple-negative breast cancer. Biomaterials 35, 5347–5358 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2014.03.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Ganesan P., et al. (2014) Triple-negative breast cancer patients treated at MD Anderson Cancer Center in phase I trials: improved outcomes with combination chemotherapy and targeted agents. Mol. Cancer Ther. 13, 3175–3184 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-14-0358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Teo Z.L., et al. (2017) Combined CDK4/6 and PI3Kα inhibition is synergistic and immunogenic in triple negative breast cancer. Cancer Res., 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-17-2210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Min A., et al. (2015) Histone deacetylase inhibitor, suberoylanilide hydroxamic acid (SAHA), enhances anti-tumor effects of the poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) inhibitor olaparib in triple-negative breast cancer cells. Breast Cancer Res. 17, 33 10.1186/s13058-015-0534-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Borbely G., et al. (2015) Induction of USP17 by combining BET and HDAC inhibitors in breast cancer cells. Oncotarget 6, 33623 10.18632/oncotarget.5601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Sekeres M.A., et al. (2014) A randomized phase II study of azacitidine combined with lenalidomide or with vorinostat vs. azacitidine monotherapy in higher-risk myelodysplastic syndromes (MDS) and chronic myelomonocytic leukemia (CMML): North American Intergroup Study SWOG S1117. Blood 124, LBA–5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Issa J.P., et al. (2015) Results of phase 2 randomized study of low‐dose decitabine with or without valproic acid in patients with myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myelogenous leukemia. Cancer 121, 556–561 10.1002/cncr.29085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Prebet T., et al. (2014) Prolonged administration of azacitidine with or without entinostat for myelodysplastic syndrome and acute myeloid leukemia with myelodysplasia-related changes: results of the US Leukemia Intergroup trial E1905. J. Clin. Oncol. 32, 1242–1248 10.1200/JCO.2013.50.3102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Yang A.S. and Yang B.J. (2015) The failure of epigenetic combination therapy for cancer and what it might be telling us about DNA methylation inhibitors. Epigenomics 8, 9–12, [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Gari H., et al. (2016) Loss of the oncogenic phosphatase PRL-3 promotes a TNF-R1 feedback loop that mediates triple-negative breast cancer growth. Oncogenesis 5, e255 10.1038/oncsis.2016.50 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Liang Z., et al. (2011) Regulation of miR-19 to breast cancer chemoresistance through targeting PTEN. Pharm. Res. 28, 3091–3100 10.1007/s11095-011-0570-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Chen Y.-J., et al. (2013) Lapatinib–induced NF-kappaB activation sensitizes triple-negative breast cancer cells to proteasome inhibitors. Breast Cancer Res. 15, R108 10.1186/bcr3575 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Kabos P., et al. (2011) Cytokeratin 5 positive cells represent a steroid receptor negative and therapy resistant subpopulation in luminal breast cancers. Breast Cancer Res. Treat. 128, 45–55 10.1007/s10549-010-1078-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Haughian J.M., et al. (2012) Maintenance of hormone responsiveness in luminal breast cancers by suppression of Notch. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 2742–2747 10.1073/pnas.1106509108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]