Hulsmans et al. show that cardiac macrophages expand in left ventricular diastolic dysfunction, a hallmark of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF) and cardiac aging. In HFpEF, macrophages shift toward a profibrotic subset that promotes ventricular stiffness.

Abstract

Macrophages populate the healthy myocardium and, depending on their phenotype, may contribute to tissue homeostasis or disease. Their origin and role in diastolic dysfunction, a hallmark of cardiac aging and heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, remain unclear. Here we show that cardiac macrophages expand in humans and mice with diastolic dysfunction, which in mice was induced by either hypertension or advanced age. A higher murine myocardial macrophage density results from monocyte recruitment and increased hematopoiesis in bone marrow and spleen. In humans, we observed a parallel constellation of hematopoietic activation: circulating myeloid cells are more frequent, and splenic 18F-FDG PET/CT imaging signal correlates with echocardiographic indices of diastolic dysfunction. While diastolic dysfunction develops, cardiac macrophages produce IL-10, activate fibroblasts, and stimulate collagen deposition, leading to impaired myocardial relaxation and increased myocardial stiffness. Deletion of IL-10 in macrophages improves diastolic function. These data imply expansion and phenotypic changes of cardiac macrophages as therapeutic targets for cardiac fibrosis leading to diastolic dysfunction.

Introduction

In addition to its signature parenchymal cells, the contracting cardiomyocytes, the heart harbors a large cast of supporters, including fibroblasts, smooth muscle cells, endothelial cells and resident macrophages (Pinto et al., 2016). Crosstalk between these cellular factions ensures myocardial homeostasis but may also initiate and propagate adverse cardiac remodeling (Kong et al., 2014; Hulsmans et al., 2016). Neurohormonal blockade attenuates this remodeling and improves outcomes in heart failure patients with reduced ejection fraction, in which pump failure compromises cardiac output (Francis, 2011). However, ∼50% of heart failure admissions account for patients with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF), a condition for which we lack therapies (Mozaffarian et al., 2016; Yancy et al., 2016). HFpEF often associates with left ventricular (LV) diastolic dysfunction, which in large part is caused by stiffer cardiomyocytes and interstitial fibrosis (Paulus and Tschöpe, 2013; Sharma and Kass, 2014). Prolonged cardiac myofibroblast activation and collagen deposition lead to distortion of tissue architecture, increased myocardial stiffness, and the heart’s inability to rapidly refill with blood in preparation of the next contraction (Hartupee and Mann, 2016). In HFpEF, the role of macrophages, which promote fibrosis in many disease settings, is incompletely understood. Specifically, insights into whether changes in cardiac macrophage number or phenotype increase myocardial stiffness may help overcome therapeutic roadblocks.

Here we show that cardiac macrophages expand and have a causal role in diastolic dysfunction. Higher myocardial macrophage densities arise from monocyte recruitment and activation of hematopoiesis in bone marrow and spleen. In mice with macrophage-specific deletion of IL-10, an interleukin that increases during diastolic dysfunction, rapid cardiac filling during diastole improves. IL-10 contributes to a macrophage phenotype shift toward a profibrotic subset, which activates fibroblasts. Fibroblasts become more numerous and deposit collagen, leading to impaired myocardial relaxation. These data define macrophage-derived IL-10 as an autocrine profibrotic agent that promotes diastolic dysfunction.

Results

Cardiac macrophages expand in diastolic dysfunction

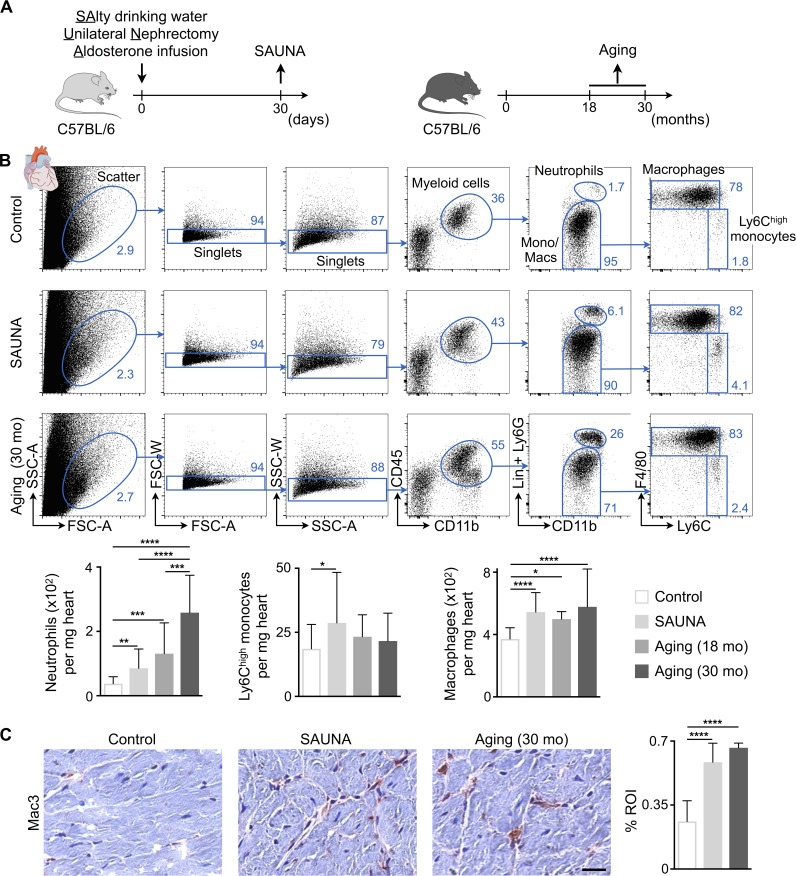

The mammalian heart contains a population of resident macrophages that expands in response to myocardial infarction and acute hemodynamic stress (Epelman et al., 2014; Heidt et al., 2014). The behavior of macrophages in diastolic dysfunction is not well understood, and it is unclear if and how these cells contribute to the relaxation properties of the heart. We examined cardiac macrophages in mice, using two validated approaches to study diastolic dysfunction of the left ventricle. The first combines salty drinking water, unilateral nephrectomy, and chronic exposure to aldosterone (SAUNA) to induce hypertension (Valero-Muñoz et al., 2016); the second is a mouse model of physiological aging (18 and 30 mo; Fig. 1 A; Signore et al., 2015; Eisenberg et al., 2016). Old (18–24 mo) and senescent (>26 mo) mice are characterized by a modest increase in LV mass and interstitial fibrosis and a decline in diastolic function in the absence of increased blood pressure (Ma et al., 2015; Signore et al., 2015; Eisenberg et al., 2016). We found that the density of macrophages in the left ventricle rose in both conditions, whereas inflammatory Ly6Chigh monocytes only increased significantly in mice exposed to SAUNA (Fig. 1, B and C). We further observed an increase in neutrophils, which was more pronounced in the senescent myocardium (Fig. 1 B). In parallel to these murine data, LV myocardial biopsies collected from patients with hypertension and HFpEF also contained more macrophages compared with age-matched healthy controls, while hypertension alone did not change the myocardial macrophage density in patients (Fig. S1 A and Table S1).

Figure 1.

Cardiac macrophage expansion in diastolic dysfunction. (A) Experimental outline. Left: Mice were exposed to SAUNA; right: 18- and 30-mo-old C57BL/6 mice were used to study macrophages in aging. (B) Flow cytometric quantification of myeloid cell populations in hearts from control, SAUNA-exposed, and aged mice. Top: Representative flow cytometry plots; bottom: number of cell populations per milligram of heart tissue. Data are pooled from two (aging) to seven (SAUNA) independent experiments (n = 8–47 mice per group). Lin, lineage; mo, months; Mono/Macs, monocytes/macrophages. (C) Immunohistochemical analysis of macrophages in hearts from control, SAUNA-exposed, and aged mice. Left: Representative images; right: bar graph shows percentage of positive staining per ROI. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 7–12 mice per group). Bar, 25 µm. Results are shown as mean ± SD. For statistical analysis, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was performed for multiple comparisons. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

Exposure to SAUNA for 30 d increased systolic blood pressure (Fig. S2 A), a highly prevalent comorbidity in human HFpEF patients (McMurray et al., 2008). The heart rate was unchanged compared with healthy control mice (Fig. S2 B). We next measured reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in cardiac endothelial cells as a surrogate marker for endothelial cell dysfunction, a possible instigator of HFpEF development and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (Paulus and Tschöpe, 2013). ROS levels rose in endothelial cells isolated from SAUNA hearts (Fig. S2 C) and associated with cardiomyocyte hypertrophy (Fig. S2, D and E). Cardiac fibroblasts in SAUNA-exposed hearts also produced more ROS (Fig. S2 F), which favors their proliferation and activation to collagen-producing myofibroblasts (Ohtsu et al., 2005; Alili et al., 2014). The increased fibroblast density, together with lower protease and metalloproteinase (MMP) activities, aligns with interstitial fibrosis in SAUNA hearts (Fig. S2, G–I). Higher LV end-diastolic pressure, reduced diastolic relaxation (–dP/dt), and prolonged time constant of pressure decay (τ) all document declining diastolic function in SAUNA-exposed mice (Fig. S2 J). Systolic parameters, including ejection fraction and maximum rate of pressure change (+dP/dt), were preserved (Fig. S2 K). SAUNA-exposed mice also showed increased cardiac expression of atrial and brain natriuretic peptide (Anp and Bnp, respectively) and pulmonary congestion, all surrogate markers for congestive heart failure (Fig. S2, L and M). Each individual SAUNA intervention component (i.e., only salty drinking water, unilateral nephrectomy, or aldosterone infusion) did not increase myeloid cells (Fig. S2 N).

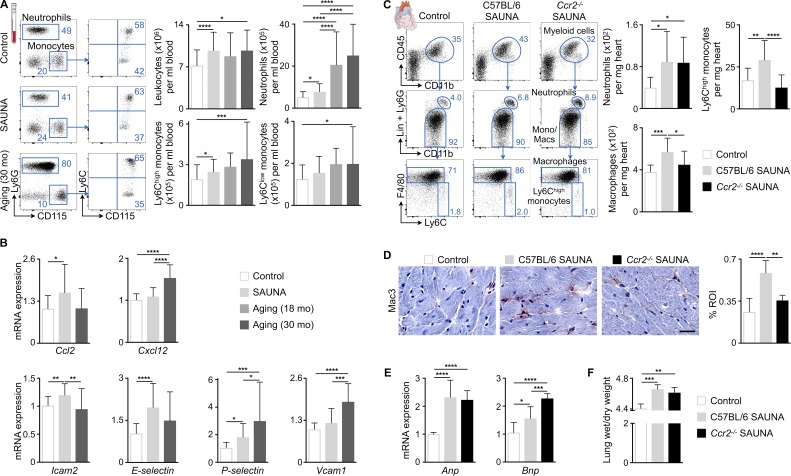

Monocyte recruitment contributes to cardiac macrophage expansion

To evaluate systemic innate immunity in mice exposed to SAUNA or aging, we began by quantifying systemic leukocyte levels with flow cytometry. Total blood leukocyte counts, including inflammatory Ly6Chigh monocytes and neutrophils, rose in both conditions (Fig. 2 A). Interestingly, neutrophilia was more pronounced in old and senescent mice (Fig. 2 A). Individual SAUNA interventions did not alter myeloid cell numbers (Fig. S2 O). Data obtained in a cohort of HFpEF patients showed a similar increase of blood leukocytes, neutrophils, and monocytes, whereas lymphocyte numbers were unchanged (Fig. S1 B).

Figure 2.

Ccr2-dependent monocyte recruitment contributes to cardiac macrophage expansion associated with diastolic dysfunction. (A) Flow cytometric quantification of monocytes and neutrophils in blood from control, SAUNA-exposed, and aged mice. Left: Representative flow cytometry plots; right: number of leukocytes and myeloid cells per milliliter of blood. Data are pooled from 2 (aging) to 11 (SAUNA) independent experiments (n = 8–89 mice per group). (B) Relative expression levels of different chemokines and adhesion molecules by qPCR in hearts from control, SAUNA-exposed, and aged mice. Data are pooled from two (aging) to four (SAUNA) independent experiments (n = 10–33 mice per group). (C) Flow cytometric quantification of myeloid cell populations in hearts from control and C57BL/6 and Ccr2−/− SAUNA-exposed mice. Left: Representative flow cytometry plots; right: number of cell populations per milligram of heart tissue. Data are pooled from three independent experiments (n = 14–15 mice per group). (D) Immunohistochemical analysis of macrophages in hearts from control and C57BL/6 and Ccr2−/− SAUNA-exposed mice. Left: Representative images; right: bar graph shows percentage of positive staining per ROI. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 5–12 mice per group). Bar, 25 µm. (E) Relative Anp and Bnp expression levels by qPCR in hearts from control and C57BL/6 and Ccr2−/− SAUNA-exposed mice. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 8–12 mice per group). (F) Lung wet-to-dry weight ratio in control and C57BL/6 and Ccr2−/− SAUNA-exposed mice. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 4 mice per group). Results are shown as mean ± SD. For statistical analysis, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was performed for multiple comparisons. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

To determine whether accumulation of myocardial macrophages relies on recruitment of monocytes from the blood, we measured expression of chemokines and adhesion molecules in myocardial tissue from SAUNA and senescent mice (Fig. 2 B). Interestingly, chemokine C-C motif ligand-2 (Ccl2) was only increased in SAUNA-exposed mice, whereas chemokine C-X-C motif ligand-12 (Cxcl12) only rose in senescent myocardium (Fig. 2 B), a constellation that aligns well with the differences in cardiac neutrophil densities observed in both conditions (Fig. 1 B). We next tested the role of the Ccl2/Ccr2 axis in recruiting monocytes to the diseased myocardium by exposing Ccr2−/− mice, which lack the receptor for Ccl2, to SAUNA. Myocardial Ly6Chigh monocyte and macrophage numbers decreased in Ccr2−/− SAUNA-exposed mice, whereas neutrophils were unaffected (Fig. 2, C and D). Deletion of Ccr2 in SAUNA-exposed mice did not reduce cardiac Anp and Bnp levels or pulmonary congestion (Fig. 2, E and F). These data indicate that Ccr2-dependent monocyte migration contributes to cardiac macrophage expansion in mice with diastolic dysfunction induced by SAUNA and that inhibiting monocyte recruitment alone is not sufficient to prevent congestive heart failure.

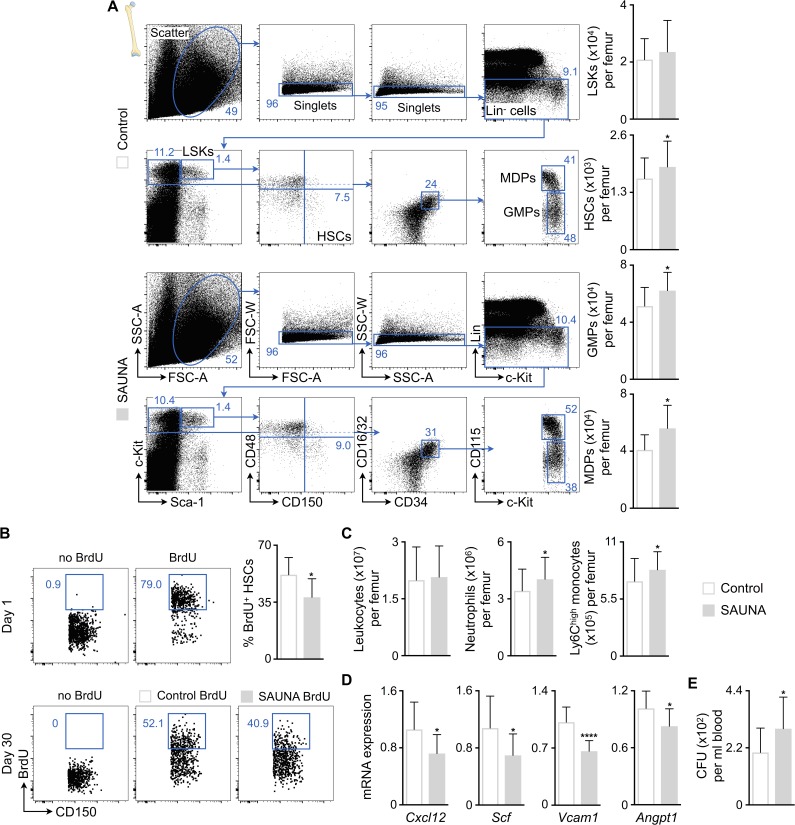

Hematopoietic activation during diastolic dysfunction

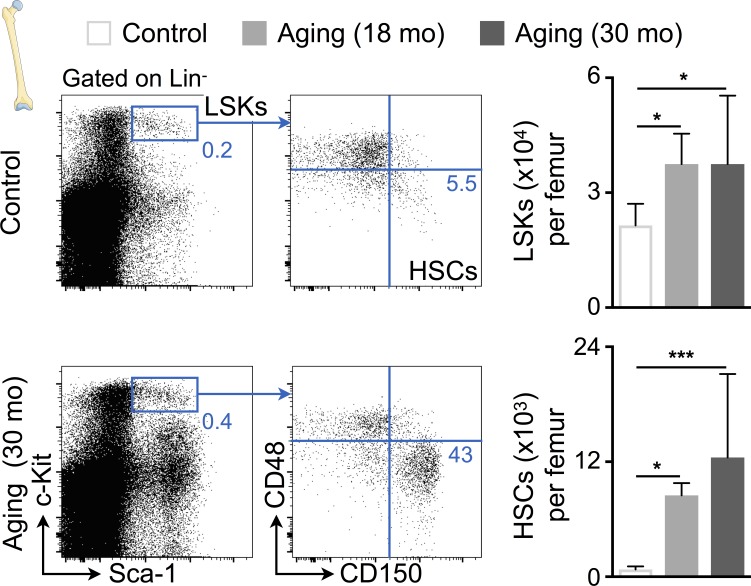

Because our data indicate that mice and humans with diastolic dysfunction develop blood monocytosis and neutrophilia, we next investigated hematopoiesis. Bone marrow harvested from SAUNA-exposed mice contained higher numbers of hematopoietic stem cells (HSCs), downstream myeloid progenitors including granulocyte macrophage progenitors (GMPs) and monocyte-macrophage dendritic cell progenitors (MDPs, Fig. 3 A). This increase in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) indicates that the cells proliferate at higher rates. To experimentally assess cell proliferation during the development of diastolic dysfunction, we performed a pulse-chase BrdU label retention experiment. 2-wk BrdU exposure via drinking water led to >70% labeling of HSCs (Fig. 3 B). After completing the label wash-in phase, we exposed mice to SAUNA for 30 d. This accelerated HSC BrdU wash-out significantly (Fig. 3 B), thus indicating that HSCs divide more frequently while diastolic dysfunction develops. The increased hematopoietic activity augmented monocyte and neutrophil numbers in the bone marrow of SAUNA-exposed mice (Fig. 3 C). When studying niche factors that regulate HSPC quiescence and retention, we observed decreased levels of Cxcl12, stem cell factor (Scf), vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (Vcam1), and angiopoietin-1 (Angpt1) in bone marrow of SAUNA-exposed mice (Fig. 3 D). Lower retention factor expression enhanced HSPC release from the marrow into the blood (Fig. 3 E). At advanced age, HSPC levels were increased in bone marrow samples in a similar fashion (Fig. 4).

Figure 3.

SAUNA increases bone marrow hematopoiesis. (A) Flow cytometric quantification of HSPCs in bone marrow from control and SAUNA-exposed mice. Left: Representative flow cytometry plots; right: number of HSPCs per femur. Data are pooled from at least two independent experiments (n = 10–36 mice per group). (B) BrdU pulse-chase experiment. Mice were exposed to BrdU in drinking water for 2 wk, which led to >70% BrdU labeling of HSCs (day 1). Additional cohorts of mice were exposed to SAUNA for 30 d or remained unexposed after BrdU labeling. The lower panel shows representative dot plots, and the bar graph shows quantification of BrdU retention in HSCs (day 30). Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 10 mice per group). (C) Number of leukocytes and myeloid cells per femur from control and SAUNA-exposed mice. Data are pooled from five independent experiments (n = 27–42 mice per group). (D) Retention factor expression by qPCR in bone marrow from control and SAUNA-exposed mice. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 9–14 mice per group). (E) Blood CFU assay in control and SAUNA-exposed mice. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 10–16 mice per group). Results are shown as mean ± SD. For statistical analysis, a two-tailed unpaired t test was performed to compare two groups. *, P < 0.05; ****, P < 0.0001.

Figure 4.

Aging expands bone marrow HSCs. Flow cytometric quantification of HSPCs in bone marrow from control and aged mice. Left: Representative flow cytometry plots; right: number of HSPCs per femur. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 8–10 mice per group). Results are shown as mean ± SD. For statistical analysis, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was performed for multiple comparisons. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001.

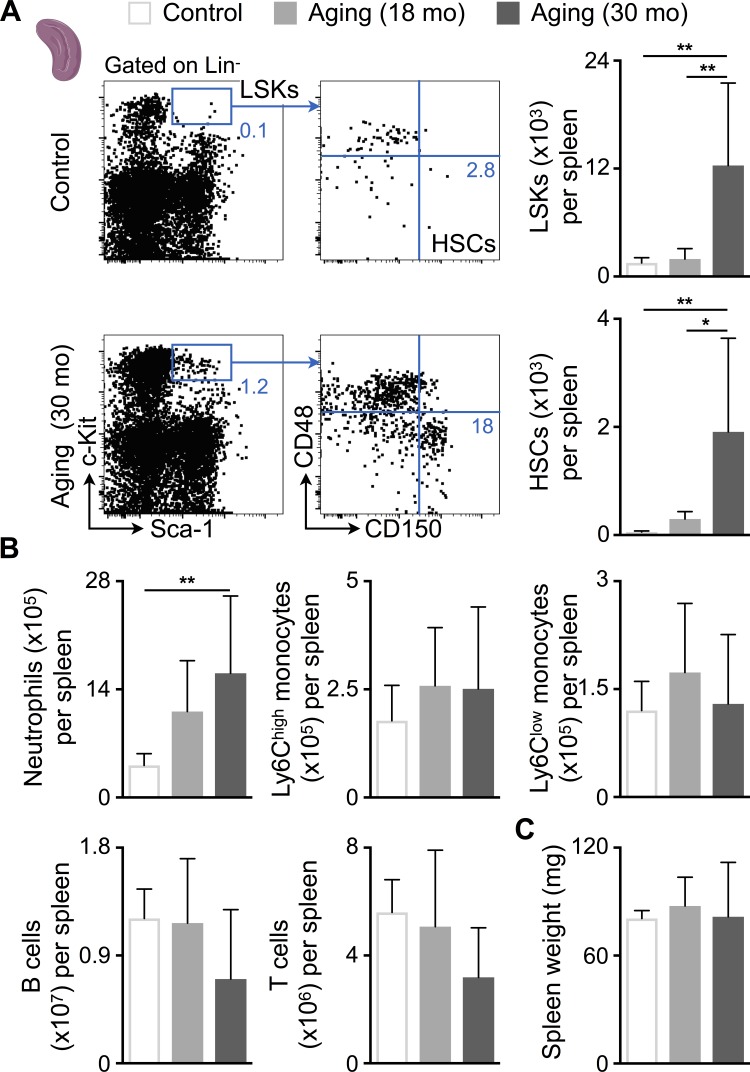

Because blood HSPCs increased in SAUNA-exposed mice (Fig. 3 E), we next investigated if these cells seed the spleen to induce extramedullary hematopoiesis. The number of splenic HSCs, monocytes, neutrophils, and B cells increased in SAUNA-exposed mice, which led to splenomegaly (Fig. 5, A–C). Individual SAUNA components did not increase myeloid cell numbers in the spleen (Fig. S2 P). In senescent mice, splenic Lineage− Sca-1+ c-Kit+ progenitor (LSK), HSC, and neutrophil numbers expanded even more drastically (Fig. 6, A and B). However, the numbers of lymphocytes had a tendency to be lower in senescent mice (Fig. 6 B), which may explain their unchanged spleen weights (Fig. 6 C).

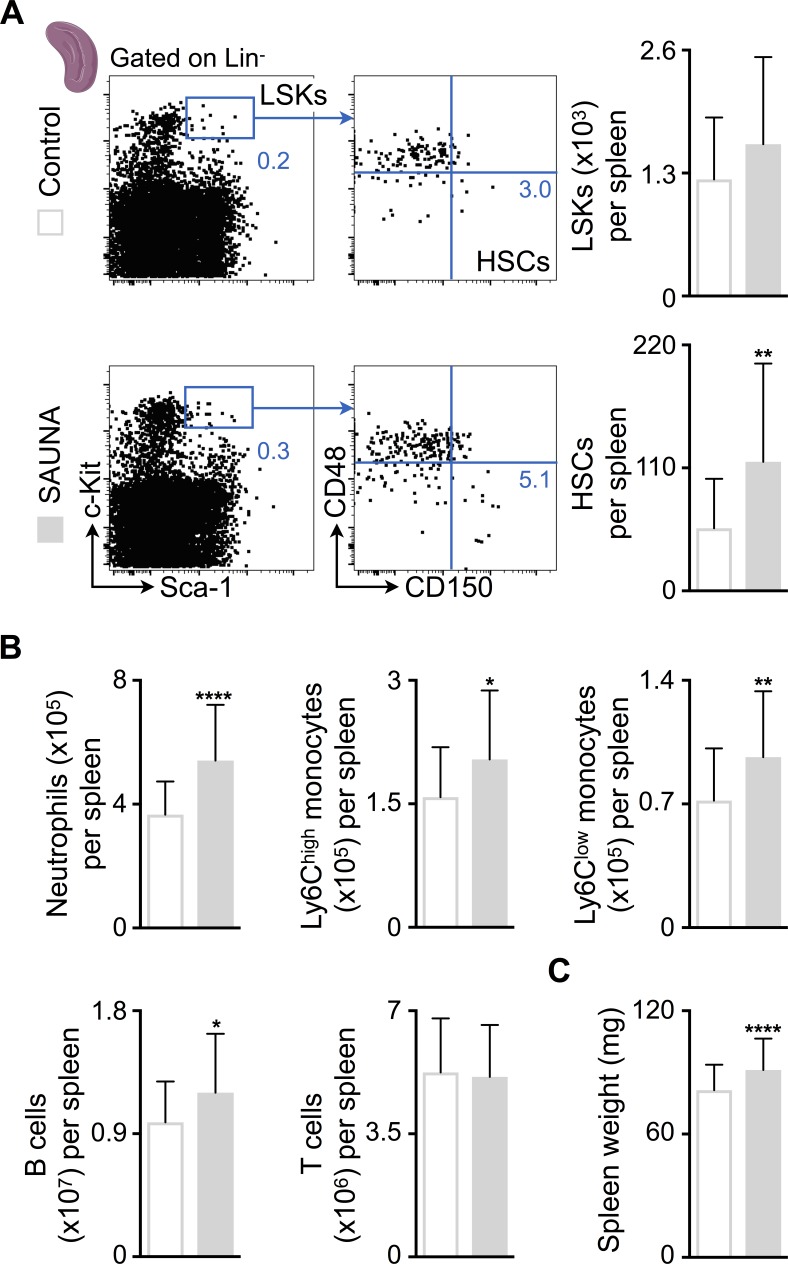

Figure 5.

SAUNA induces splenic myelopoiesis. (A) Flow cytometric quantification of HSPCs in spleens from control and SAUNA-exposed mice. Left: Representative flow cytometry plots; right: number of HSPCs per spleen. Data are pooled from five independent experiments (n = 25–39 mice per group). (B) Number of splenic myeloid cells and lymphocytes in control and SAUNA-exposed mice. Data are pooled from five independent experiments (n = 27–42 mice per group). (C) Spleen weight in control and SAUNA-exposed mice. Data are pooled from 15 independent experiments (n = 102–103 mice per group). Results are shown as mean ± SD. For statistical analysis, a two-tailed unpaired t test was performed to compare two groups. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001.

Figure 6.

Aging expands splenic HSCs. (A) Flow cytometric quantification of HSPCs in spleens from control and aged mice. Left: Representative flow cytometry plots; right: number of HSPCs per spleen. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 8–10 mice per group). (B) Number of splenic myeloid cells and lymphocytes in control and aged mice. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 8–10 mice per group). (C) Spleen weight in control and aged mice. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 8–10 mice per group). Results are shown as mean ± SD. For statistical analysis, one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was performed for multiple comparisons. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

To assess whether activation of hematopoiesis associates with altered diastolic function in humans, we correlated 18F-fluoro-2-deoxyglucose (18F-FDG) uptake in hematopoietic organs with echocardiographic parameters of diastolic function in a retrospective analysis (Fig. S1 C). Increased 18F-FDG positron emission tomography (PET) signal reflects higher metabolic rates, which in marrow and spleen indicates accelerated hematopoietic activity (Liu, 2009). Among patients with normal diastolic function (see Materials and methods for patient selection criteria), we found a significant correlation of splenic PET signal with echocardiographic measures of filling pressures (i.e., E/e′ and the estimated right ventricular systolic pressure) and observed similar trends for the marrow PET signal (Fig. S1 C). These retrospective clinical data are preliminary because of (a) a small sample size, (b) the unspecific mechanisms behind 18F-FDG uptake, and (c) the load dependence of echocardiographic measures, which were acquired at different time points. Nevertheless, the parallels between the histology, flow cytometry, and imaging observations in patients and those in mice are intriguing, indicating that diastolic dysfunction associates with increased myelopoiesis and systemic myeloid cell oversupply.

Macrophage-derived IL-10 contributes to SAUNA-induced diastolic dysfunction

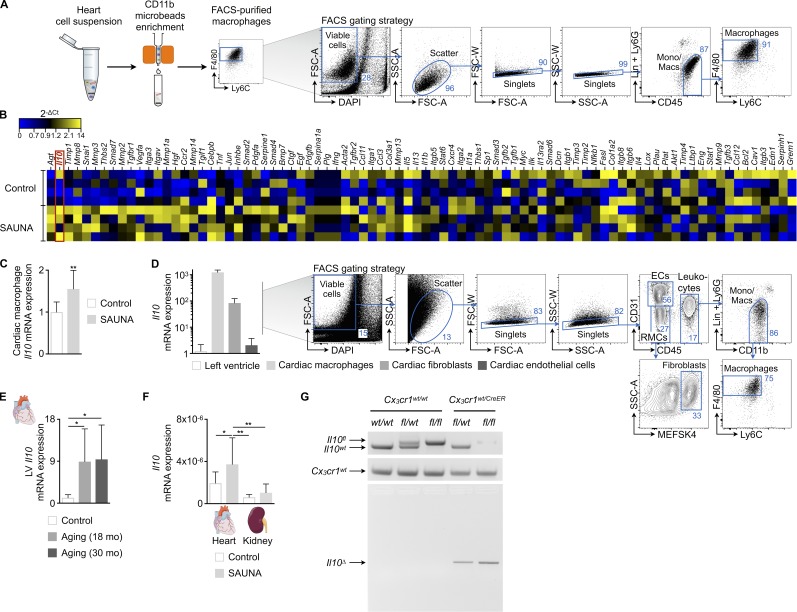

To evaluate phenotypic changes of cardiac macrophages, we compared these cells obtained from SAUNA and control myocardium using a fibrosis quantitative PCR (qPCR) array. We identified Il10 as one of the most up-regulated fibrosis-related genes in cardiac macrophages that were FACS-purified from SAUNA mice’s myocardium (Fig. 7, A–C). IL-10 is a pleiotropic cytokine produced and sensed by many leukocytes, including macrophages (Moore et al., 2001). We confirmed that tissue-resident macrophages are indeed a dominant source of Il10 by comparing their expression to whole myocardium, cardiac fibroblasts, and endothelial cells (Fig. 7 D). Old and senescent myocardium also showed higher expression levels of Il10 (Fig. 7 E), further supporting a contributing role of this cytokine in the development of diastolic dysfunction. The remaining kidney in SAUNA-treated mice, which also contains resident macrophages (Schulz et al., 2012), exhibited lower Il10 expression than the myocardium (Fig. 7 F).

Figure 7.

Identification and validation of Il10 produced by cardiac macrophages as gene of interest. (A) Workflow and FACS gating strategy to purify macrophages from heart tissue. (B) Heat map of expression values (2-ΔCt) of fibrosis-related genes by qPCR in FACS-purified cardiac macrophages from control and SAUNA-exposed mice (n = 4 mice per group). (C) Relative Il10 expression levels by qPCR in macrophages FACS-sorted from a second, independent cohort of control and SAUNA-exposed mice (n = 8–9 mice per group). (D) Left: Il10 expression by qPCR in left ventricle and FACS-purified cardiac macrophages, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells from C57BL/6 mice (n = 6–9 mice per group); right: FACS gating strategy to purify macrophages, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells from heart tissue. (E) Relative Il10 expression levels by qPCR in hearts from control and aged mice. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 7–9 mice per group). (F) Relative Il10 expression levels by qPCR in hearts and kidneys from control and SAUNA-exposed mice. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 7–15 mice per group). (G) PCR analysis of FACS-purified Cx3cr1wt/wt and Cx3cr1wt/CreER cardiac macrophages 7 d after tamoxifen treatment for the presence of wild-type (Il10wt) and conditional undeleted (Il10fl) or deleted (Il10Δ) Il10 alleles. Results are shown as mean ± SD. For statistical analysis, a two-tailed unpaired t test was performed to compare two groups, and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was performed for multiple comparisons. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01.

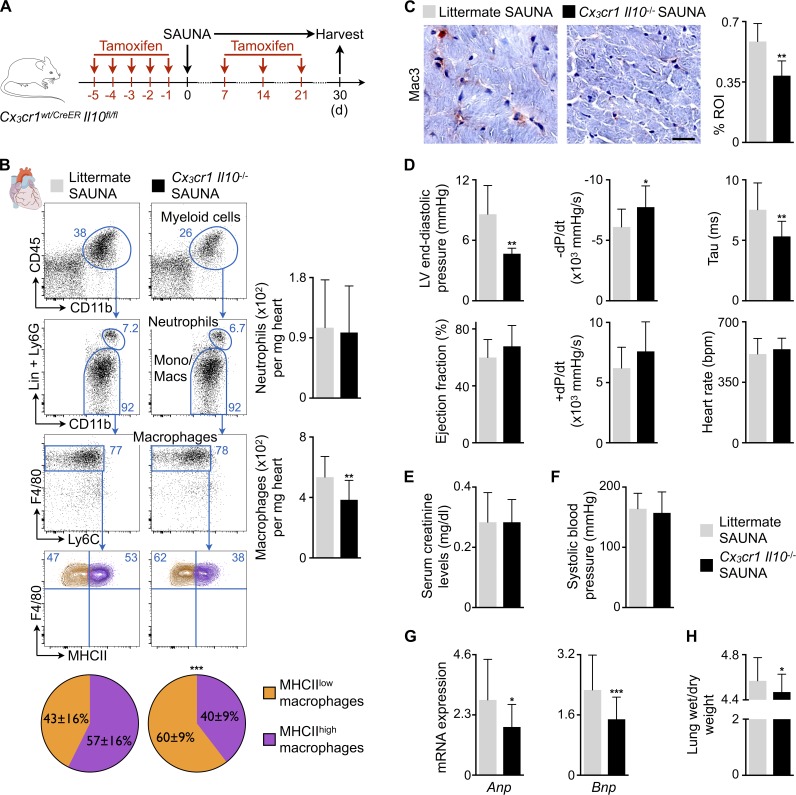

To probe whether macrophage-derived IL-10 causally contributes to diastolic dysfunction, we bred tamoxifen-inducible Cx3cr1CreER with Il10fl/fl mice, hereafter denoted as Cx3cr1 Il10−/−, to obtain mice in which tamoxifen treatment deletes Il10 in Cx3cr1-expressing monocytes and macrophages. We previously validated the specificity of the Cx3cr1 promoter to study cardiac macrophages in steady-state and pathological conditions (Heidt et al., 2014; Hulsmans et al., 2017). Genomic PCR-based examination of the wild-type (Il10wt), floxed intact (Il10fl), and recombined (Il10Δ) alleles of the Il10 gene in FACS-purified Cx3cr1+ cardiac macrophages showed effective Il10 deletion in cardiac macrophages after tamoxifen treatment (Fig. 7 G). Cx3cr1 Il10−/− mice were then exposed to SAUNA for 30 d while receiving an additional tamoxifen dose once a week to deplete Il10 in newly made monocytes and monocyte-derived macrophages. All Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-exposed mice underwent analysis 7 d after a final tamoxifen injection (Fig. 8 A). LV myocardium collected from Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-exposed mice contained fewer macrophages compared with littermate SAUNA-treated mice, whereas myocardial neutrophil numbers did not change (Fig. 8, B and C). The phenotype of cardiac macrophages in Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-treated mice shifted toward the MHCIIlow macrophage subset (Epelman et al., 2014; Fig. 8 B). Importantly, monocyte/macrophage-restricted deletion of Il10 improved diastolic function assessed by invasive hemodynamic measurements. Cx3cr1 Il10−/− mice that underwent the SAUNA protocol had a reduced LV end-diastolic pressure and better diastolic relaxation indicated by a larger −dP/dt and shortening of the isovolumic relaxation constant τ (Fig. 8 D). These data document that deleting IL-10 in macrophages attenuates development of diastolic dysfunction, which was independent of renal function or systolic blood pressure changes (Fig. 8, E and F). The myocardium of Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-exposed mice expressed less Anp and Bnp, and pulmonary congestion diminished (Fig. 8, G and H).

Figure 8.

Macrophage-restricted IL-10 deletion in SAUNA-exposed mice improves diastolic function. (A) Experimental outline of the SAUNA protocol applied on mice lacking IL-10. (B) Flow cytometric quantification of neutrophils and macrophages in hearts from littermate and Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-exposed mice. Left: Representative flow cytometry plots; right: number of neutrophils and macrophages per milligram of heart tissue. The pie charts indicate the percentage of MHCIIlow (orange) and MHCIIhigh (purple) cardiac macrophages. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 14–16 mice per group). (C) Immunohistochemical analysis of macrophages in hearts from littermate and Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-exposed mice. Left: Representative images; right: bar graph shows percentage of positive staining per ROI. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 6–7 mice per group). Bar, 25 µm. (D) Hemodynamic parameters by pressure–volume catherization of hearts from littermate and Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-exposed mice. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 7–11 mice per group). (E) Serum creatinine levels in littermate and Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-exposed mice. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 6 mice per group). (F) Systolic blood pressure in littermate and Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-exposed mice. Data are pooled from six independent experiments (n = 38–46 mice per group). (G) Relative Anp and Bnp expression levels by qPCR in hearts from littermate and Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-exposed mice. Data are pooled from four independent experiments (n = 27 mice per group). (H) Lung wet-to-dry weight ratio in littermate and Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-exposed mice. Data are pooled from five independent experiments (n = 32–39 mice per group). Results are shown as mean ± SD. For statistical analysis, a two-tailed unpaired t test was performed to compare two groups. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001.

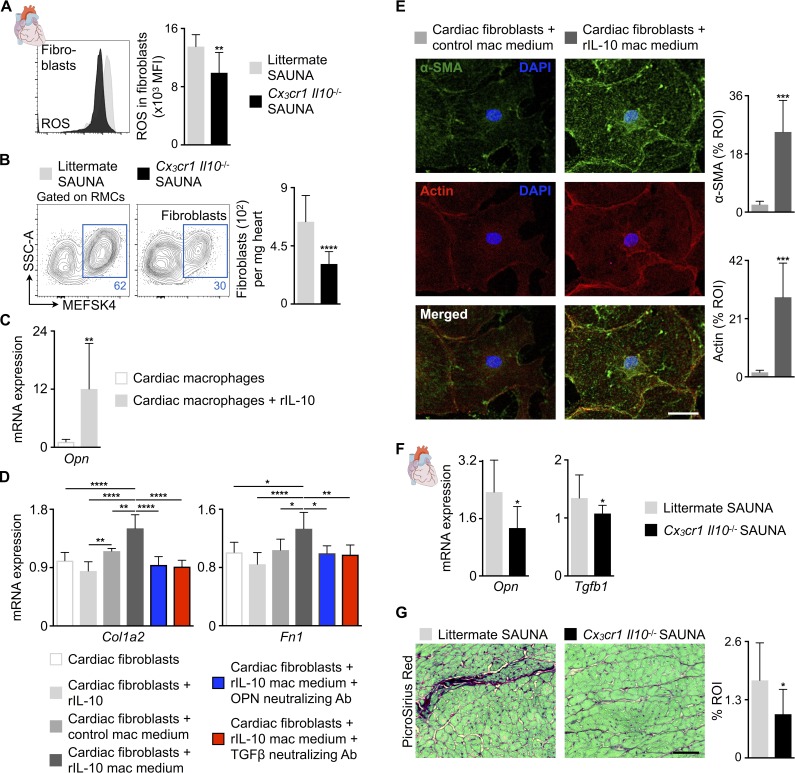

Macrophage-derived IL-10 indirectly promotes fibroblast activation

Next, we investigated how increased IL-10 production by cardiac macrophages deteriorates diastolic function. We observed no difference in LV mass between littermate and Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-treated mice by cardiac magnetic resonance imaging, indicating no effect of IL-10 on SAUNA-induced hypertrophy (Fig. S3 A). Therefore, we focused on the crosstalk between macrophages and fibroblasts and their contribution to fibrosis-mediated myocardial stiffness. The deletion of Il10 in macrophages of SAUNA-treated mice lowered ROS production in cardiac fibroblasts (Fig. 9 A) and decreased fibroblast numbers (Fig. 9 B). To determine if IL-10 can directly activate fibroblasts, we measured the expression of its receptor, which is composed of an IL-10–binding chain (IL-10Rα) and an accessory molecule shared with other receptors of IL-10 superfamily members (IL-10Rβ; Moore et al., 2001), in fibroblasts. qPCR on FACS-purified noncardiomyocytes revealed that only cardiac macrophages express both receptor subunits that are necessary for IL-10 binding (Moore et al., 2001; Fig. S3 B), suggesting that IL-10 indirectly modulates fibroblasts by autocrine activation of macrophages toward a fibrogenic phenotype. FACS-purified cardiac macrophages exposed to recombinant murine IL-10 (rIL-10) expressed more osteopontin (Opn; Fig. 9 C), a matricellular protein and multifunctional cytokine associated with cardiac fibrosis causing myofibroblast differentiation and activation (Lenga et al., 2008; Shiraishi et al., 2016). Interestingly, macrophages are also the main source of Opn in LV myocardial tissue (Fig. S3 B). We then exposed FACS-purified cardiac fibroblasts to rIL-10 directly or to cell culture medium collected from cardiac macrophages incubated with rIL-10. Cardiac fibroblasts increased expression of type I collagen (Col1a2), fibronectin (Fn1), actin filaments, and α-smooth muscle actin (α-SMA) after incubation with rIL-10–exposed macrophage medium (Fig. 9, D and E), all documenting enhanced fibroblast activation. Direct exposure of cardiac fibroblasts to rIL-10 did not change Col1a2 and Fn1 expression (Fig. 9 D). Furthermore, antibody-mediated neutralization of OPN suppressed activation of fibroblasts (Fig. 9 D). Similar suppressive effects occurred after neutralizing TGFβ (Fig. 9 D). These data suggest that OPN is produced by macrophages and acts as a paracrine fibroblast activator. Cardiac macrophages are also a source of Tgfb1 (Fig. S3 B). In deposited microarray data (Epelman et al., 2014), a gene set associated with the regulation of TGFβ production (GO:0032914) enriched in MHCIIhigh macrophages when compared with the MHCIIlow subset (Fig. S3 C). MHCIIlow macrophages, which were more prevalent in Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-treated mice (Fig. 8 B), showed higher protease and MMP activity compared with MHCIIhigh macrophages (Fig. S3 D), indicating that the MHCIIlow macrophage subset favors matrix breakdown. Taken together, these data suggest that MHCIIlow macrophages, which are more numerous after IL-10 deletion, counteract fibrosis whereas MHCIIhigh macrophages promote it. LV myocardium from Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-treated mice indeed decreased Opn and Tgfb1 expression and interstitial fibrosis compared with littermate SAUNA-treated mice (Fig. 9, F and G). Thus, macrophage-derived IL-10 is a profibrotic cytokine that indirectly activates cardiac (myo)fibroblasts, promoting collagen deposition and myocardial stiffness in diastolic dysfunction.

Figure 9.

IL-10 produced by cardiac macrophages indirectly activates fibroblasts. (A) Mean fluorescence intensities (MFI) indicating ROS production in cardiac fibroblasts from littermate and Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-exposed mice. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 11 mice per group). (B) Flow cytometric quantification of fibroblasts in hearts from littermate and Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-exposed mice. Left: Representative flow cytometry plots; right: number of fibroblasts per milligram of heart tissue. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 11–15 mice per group). RMCs, resident mesenchymal cells. (C) Relative Opn expression levels by qPCR in control and rIL-10–exposed FACS-purified cardiac macrophages. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 10 per group). (D) Relative Col1a2 and Fn1 expression levels by qPCR in FACS-purified cardiac fibroblasts incubated with rIL-10, control macrophage (mac) medium or rIL-10–exposed mac medium with and without OPN or TGFβ neutralizing antibody (Ab). Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 4–7 per group). (E) Left: Representative immunofluorescence images of FACS-purified cardiac fibroblasts incubated with control or rIL-10–exposed mac medium, and stained with α-SMA (green), Phalloidin to identify actin filaments (red), and DAPI (blue); right: bar graphs show percentage of positive α-SMA or actin staining per ROI. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 7 per group). Bar, 50 µm. (F) Relative Opn and Tgfb1 expression levels by qPCR in hearts from littermate and Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-exposed mice. Data are pooled from at least two independent experiments (n = 8–15 mice per group). (G) Histological analysis of collagen deposition (PicroSirius Red) in hearts from littermate and Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-exposed mice. Left: Representative images; right: bar graph shows percentage of positive staining per ROI. Data are pooled from two independent experiments (n = 6 mice per group). Bar, 50 µm. Results are shown as mean ± SD. For statistical analysis, a two-tailed unpaired t test was performed to compare two groups, and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s test was performed for multiple comparisons. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

Discussion

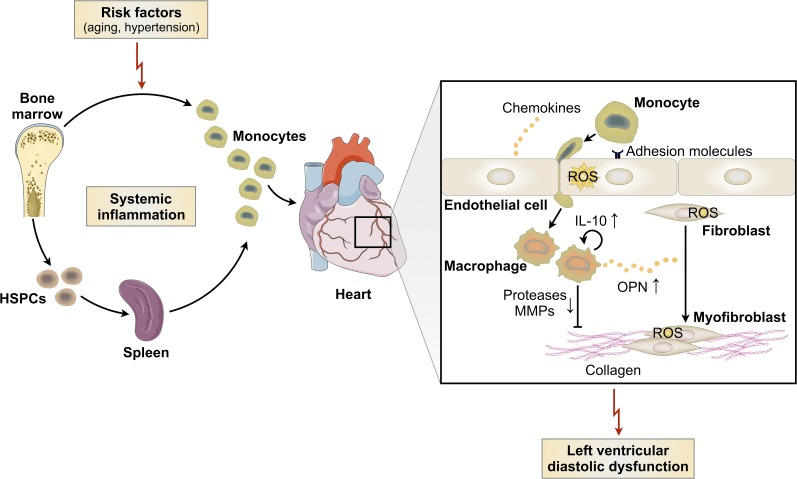

The genesis of HFpEF is multifactorial, which likely contributes to the current lack of treatment options and the lively debate on how to best study HFpEF pathophysiology in animals. Nevertheless, the problem is urgent as mortality and morbidity increase (Vasan et al., 1999; Owan et al., 2006). Advanced age, hypertension, diabetes, and obesity are accepted risk factors (Ather et al., 2012), while myocardial fibrosis and hypertrophy are common pathologies. In many conditions, macrophages regulate extracellular matrix turnover (Wick et al., 2013; Kong et al., 2014). Because they are well equipped to sense their surroundings (Murray and Wynn, 2011), macrophage phenotypes may rapidly adjust to systemic risk. We therefore studied myeloid cells in two different conditions that lead to diastolic dysfunction in mice and compared some key findings to HFpEF patients. While our clinical observations are preliminary and should be interpreted with caution, the data document interesting parallels and some differences between murine cohorts and humans. Cardiac macrophages expand in aged mice, in mice exposed to SAUNA, and in myocardial biopsies from HFpEF patients. Both murine conditions and HFpEF in patients increase circulating monocytes, which are progenitors of macrophages recruited to the diseased heart. In all three scenarios, we observed increased activity in hematopoietic organs (Fig. 10). Taken together, these data align well with the systemic inflammation previously reported in HFpEF patients (Kalogeropoulos et al., 2010) and provide a compelling rationale to consider macrophages’ role in HFpEF pathophysiology.

Figure 10.

Summary cartoon. Systemic inflammation and impaired LV diastolic function are seen in both hypertension and physiological aging. Circulating monocytes and myocardial macrophage density are increased in diastolic dysfunction, and the macrophage expansion is partially driven by monocyte recruitment. Blood monocytosis derives from increased production in the bone marrow and spleen. Mechanistically, cardiac macrophages produce more IL-10 leading to their autocrine activation toward a fibrogenic phenotype. A profibrotic macrophage subset secretes more OPN and fewer proteases and MMPs, contributing to fibroblast activation, collagen deposition, and subsequently increased myocardial stiffness and diastolic dysfunction.

We also detected some interesting differences: while blood neutrophil levels were increased in all cohorts, this was more pronounced in aged mice, which exhibited the typical myeloid hematopoiesis bias associated with aging (Beerman et al., 2010). Senescent mice had more neutrophils and inflammatory monocytes in circulation and recruited more neutrophils into the myocardium when compared with SAUNA-exposed mice. Splenic hematopoiesis was likewise more pronounced in senescent mice. Aging is associated with functionally compromised HSCs, which expand phenotypically (Dykstra et al., 2011; Beerman et al., 2013) and develop a myeloid bias (Beerman et al., 2010). The recently reported association of patients’ cardiovascular mortality with clonal hematopoiesis (Jaiswal et al., 2014), which occurs in senescence, an HFpEF risk factor, supports a potential relationship of heart failure with hematopoiesis, cardiac macrophage origins, phenotypes, and abundance. Of note, distinct mechanisms observed in the two murine disease models may occur simultaneously in elderly patients, contributing jointly to an overall expansion of myeloid cells in the heart.

We noted an excess production of IL-10 in the setting of diastolic dysfunction caused by SAUNA and old age. Macrophage-specific IL-10 deletion reduced fibrosis and improved diastolic function. While the Cx3cr1CreER mouse expresses the tamoxifen-inducible Cre recombinase fusion protein (CreER) in monocytes and macrophages (Yona et al., 2013; Hulsmans et al., 2017), this is not restricted to the heart but could also affect other organs, such as the brain and kidney. Despite this caveat, we ruled out that restored diastolic function in Cx3cr1 Il10−/− SAUNA-treated mice was the result of improved renal function or lower blood pressure. Macrophage IL-10 production indirectly induces (myo)fibroblast activation and collagen deposition resulting in increased myocardial stiffness (Fig. 10). HFpEF myocardium contains more collagen type I, increasingly cross-linked collagen, and less MMP activity, all contributing to fibrosis-mediated diastolic dysfunction (Kasner et al., 2011; Westermann et al., 2011). Cardiac macrophages in HFpEF patients also secrete profibrotic TGFβ further inducing excess collagen deposition (Westermann et al., 2011). During the reparative phase after acute myocardial infarction, IL-10–producing macrophages direct myofibroblast proliferation and mature scar formation (Troidl et al., 2009). Interestingly, atherosclerotic lesions in Il10−/− mice show a very low percentage of collagen deposition (Mallat et al., 1999), whereas long-term overexpression of IL-10 promotes lung fibrosis (Sun et al., 2011). These data parallel our findings that IL-10 may exert profibrotic deleterious actions in a chronic disease setting, even though it may be beneficial in inflammation resolution and wound healing. Systemic IL-10 treatment attenuates hypertrophic remodeling and improves heart function in mice with pressure overload-induced heart failure (Verma et al., 2012), further indicating the complex pleiotropic, disease- and potentially source-dependent effects of IL-10.

Replacing the M1/2 in vitro macrophage classification, Epelman et al. (2014) defined cardiac macrophage subsets based on expression of MHCII and CCR2, an approach recently backed by unsupervised hierarchical clustering of single-cell RNA-sequencing data (Hulsmans et al., 2017). Our data obtained in mice with diastolic dysfunction after exposure to SAUNA provide arguments in support for this classification because MHCIIhigh and MHCIIlow macrophage subsets diverge functionally in this disease setting. MHCIIlow macrophages activate in vivo protease sensors more avidly whereas MHCIIhigh macrophages enrich for a gene set that regulates profibrotic TGFβ. Viewed together with the shift toward MHCIIlow macrophages and reduced fibrosis in IL-10–deficient mice, strategies to therapeutically limit the numbers or function of the MHCIIhigh subset appear promising. Cardiac senescence is also associated with phenotypic changes in resident macrophages including up-regulation of profibrotic genes, which possibly contribute to aging-associated cardiac fibrosis (Pinto et al., 2014). Macrophages are potential therapeutic targets because of their phenotypic plasticity, their dynamic crosstalk with neighboring cells including fibroblasts (Hulsmans et al., 2016), and their avidity to ingest nanoparticle-delivered drug payloads (Mulder et al., 2014). Clearance of excess collagen from fibrotic myocardium likely requires protease activation, in which antifibrotic MHCIIlow macrophages could play a role, whereas dampening activity of profibrotic MHCIIhigh macrophages could be beneficial. Although these tactical considerations are still hypothetical, the observed causal contribution of macrophages to fibrotic myocardial remodeling and diastolic dysfunction provides new drug discovery strategies for HFpEF.

Materials and methods

Humans

Human tissue collection, blood sampling, and 18F-FDG-PET/computed tomography (CT) study were conducted according to the Declaration of Helsinki and were approved by the Medical University of South Carolina Institutional Review Board, the Veterans Administration Medical Center Research and Development Committee (PRO42347), the Boston University Medical Center Institutional Review Board (H-32244), and the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board (2010P001955). All patients gave written, informed consent as required.

Human LV myocardial biopsies were obtained at the Medical University of South Carolina and at the Ralph H. Johnson Department of Veterans Administration Medical Center. Patient recruitment and general inclusion and exclusion criteria were described previously (Zile et al., 2015). HFpEF was defined according to the general inclusion criteria specified by the European Society of Cardiology and Heart Failure Society of America (Paulus et al., 2007; Heart Failure Society of America et al., 2010). In detail, control subjects (n = 5, 80% male), patients with hypertension without HFpEF (n = 4, 75% male), and patients with hypertension and HFpEF (n = 6, 83% male) were recruited as stable outpatients scheduled for elective coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Controls and both patient groups were matched by age and sex. All subjects had coronary artery disease, none had atrial fibrillation or type 2 diabetes mellitus, and none were decompensated or admitted to the hospital for heart failure at the time of biopsy. Samples were collected from the LV epicardial anterior wall during coronary artery bypass graft surgery as described previously (Zile et al., 2015). Clinical, demographic, echocardiographic, and LV pressure data for both patient groups are summarized in Table S1. Both groups had hypertension with a similar degree of hypertension-induced LV hypertrophic remodeling. However, only patients with hypertension and HFpEF had evidence of heart failure. Specifically, only patients with HFpEF had evidence of diastolic dysfunction and increased LV diastolic filling pressures (increased pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, left atrial volume, and LV end-diastolic pressure). The increased LV diastolic pressure with normal LV end-diastolic volume demonstrates that HFpEF patients had an increased LV diastolic chamber stiffness.

Human blood samples were collected from acutely decompensated patients with HFpEF enrolled at Boston Medical Center. Patients were 60 ± 14 yr old (mean ± SD; n = 20, 50% male) and the New York Heart Association functional class was 3.8 ± 1.2 (mean ± SD) at the time of enrollment. Comorbidities included hypertension (90%), obesity (82%), type 2 diabetes mellitus (56%), and atrial fibrillation/flutter (30%). Mean LV ejection fraction and LV mass were 61 ± 7% (mean ± SD) and 194 ± 65 g (mean ± SD; normal 67–162 g), respectively. Controls were selected from ambulatory subjects and matched by age and sex. Control subjects were 57 ± 13 yr old (mean ± SD; n = 10, 50% male) healthy individuals without cardiac disease and were not taking cardiovascular medications.

For the 18F-FDG-PET/CT study, subjects without active malignancy who underwent clinically indicated imaging and who were part of a retrospective study designed to investigate the relationship between stress-associated neural activity and cardiovascular and cardiometabolic disease (n = 293) were screened for clinically indicated transthoracic echocardiograms within 1 yr before and 5 yr after imaging. Patients with reduced LV ejection fraction (<50%), moderate or severe valvular disease, and known cardiovascular pathology were excluded from the study. Additional exclusion criteria were chronic inflammatory conditions, age < 30 yr, insufficient clinical data at baseline or follow-up to ascertain clinical status, and lack or poor quality of PET/CT images. A total of 14 patients with clinically indicated transthoracic echocardiograms met these selection criteria and were evaluated by a blinded trained cardiologist using validated methods to assess parameters of diastolic impairment and elevated filling pressures according to the 2016 American Society of Echocardiography/European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging Guidelines (Nagueh et al., 2016; e.g., E/e′ and estimated right ventricular systolic pressure) from the available images. We were able to assess E/e′ and right ventricular systolic pressure from 11 and 10 patients, respectively.

Mice

All animal studies conformed to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals and were performed with the approval of the Subcommittee on Animal Research Care at Massachusetts General Hospital (2014N000078). C57BL/6 (stock 000664), B6.129S4-Ccr2tm1Ifc/J (Ccr2−/−; stock 004999), and B6.129P2(Cg)-Cx3cr1tm2.1(cre/ERT)Litt/WganJ (Cx3cr1CreER; stock 021160) were purchased from Jackson Laboratory. Genotyping of Cx3cr1CreER mice was performed as described on the Jackson Laboratory website. Il10fl/fl mice have been described elsewhere (Roers et al., 2004). All experiments (except the aging study) were performed with 8–30-wk-old animals and were performed by using age- and sex-matched groups. Aged mice (18- and 30-mo-old) were compared with 8-wk-old, sex-matched mice. All animals were on a C57BL/6 background and were maintained in a pathogen-free environment of the Massachusetts General Hospital animal facility.

In vivo interventions

To induce chronic HFpEF by using the SAUNA protocol, mice underwent unilateral nephrectomy and were exposed to a continuous infusion of d-aldosterone (0.30 µg/h; Sigma-Aldrich) via osmotic minipumps (Alzet) and salty (1% NaCl) drinking water for 30 d (Valero-Muñoz et al., 2016). Tamoxifen was given as a solution in corn oil (Sigma-Aldrich) by intraperitoneal injection. Animals received 5 doses of 2 mg tamoxifen with a separation of 24 h between doses, followed by 1 dose of 2 mg of tamoxifen per week for 3 wk. To quantify protease and MMP activity in hearts, 2 nmol of the pan-cathepsin protease sensor ProSense-680 (PerkinElmer) or 2 nmol of the MMP sensor MMPSense-680 (PerkinElmer) was injected intravenously 24 h before analysis. For BrdU label-retaining pulse-chase experiments, BrdU was added to the drinking water (1 mg/ml) for 14 d before inducing chronic HFpEF with the SAUNA protocol.

Blood pressure, surface ECG, and hemodynamic measurements

Blood pressure in conscious mice was measured with a noninvasive tail-cuff system (Kent Scientific Corporation). Surface ECG was recorded in anaesthetized mice (1.5% isoflurane in 95% O2) by using subcutaneous electrodes connected to the Animal Bio amplifier and PowerLab station (AD Instruments). LV hemodynamics were obtained in anaesthetized mice in the closed-chest approach with a Millar MPVS-300 system equipped with a Millar SPR-839 catheter. The mouse was intubated, ventilated, and warmed with a heating pad. The catheter was then inserted into the LV through the right carotid artery. During data collection, ventilation was interrupted to acquire data without lung motion artifacts. Calibration of the SPR-839 catheter and assessment of LV blood volume were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Data were analyzed with LabChart Pro software (AD Instruments).

Magnetic resonance imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging was performed with a 7-Tesla horizontal bore Pharmascan system (Bruker) equipped with a custom-built mouse cardiac coil (Rapid Biomedical) to obtain cine images of the LV short axis (Sager et al., 2016). Anatomical and functional parameters were quantified from 7–8 myocardial slices by using OsiriX software.

18F-FDG PET/CT imaging

18F-FDG PET/CT imaging in humans was performed by using validated methods (Tawakol et al., 2013). 18F-FDG was administered intravenously (∼10 mCi for a 70-kg patient) after an overnight fast with imaging performed 60–90 min after the injection with the use of a standard hybrid PET/CT scanner (e.g., Siemens Biograph 64). A CT scan for attenuation correction was performed before PET imaging from the skull to thigh with 15-min acquisitions per bed position. Attenuation-corrected images were reconstructed by using ordered subset expectation maximization algorithm. All individuals had a blood glucose level <200 mg/dl at the time of 18F-FDG injection. Image interpretation was performed by a blinded radiologist. Bone marrow and splenic activity were assessed by using validated methods (Emami et al., 2015) by measuring standardized uptake values in the target tissue (i.e., bone marrow and spleen) and correcting them for background venous activity to derive a target to background ratio (TBR).

Tissue processing

Human myocardial biopsies were obtained from the LV epicardial anterior wall during coronary artery bypass graft surgery as described previously (Zile et al., 2015). Human blood samples were collected by using BD Vacutainer CPT tubes, and peripheral blood mononuclear cells were isolated according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Peripheral mouse blood was collected by retroorbital bleeding by using heparinized capillary tubes (BD Diagnostics), and red blood cells were lysed with 1× red blood cell lysis buffer (BioLegend). To obtain the lung wet-to-dry weight ratio, lungs were excised and weighed before and after drying at 65°C for 48 h. Hearts were perfused through the left ventricle with 10 ml ice-cold PBS, excised, minced into small pieces, and subjected to enzymatic digestion with 450 U/ml collagenase I, 125 U/ml collagenase XI, 60 U/ml DNase I, and 60 U/ml hyaluronidase (all Sigma-Aldrich) for 1 h at 37°C under agitation. Spleens were excised, and bone marrow was flushed out from the bones with FACS buffer (PBS supplemented with 0.5% BSA). All mouse tissues were then triturated, and cells were filtered through a 40-µm nylon mesh (Falcon), washed, and centrifuged to obtain single-cell suspensions.

Flow cytometry

For a leukocyte staining on human peripheral blood mononuclear cells, cells were stained at 4°C in FACS buffer with CCR2 (clone K036C2, 1:600), CD3 (clone HIT3a, 1:300), CD4 (clone RPA-T4, 1:300), CD8a (clone RPA-T8, 1:300), CD14 (clone HCD14, 1:300), CD16 (clone 3G8, 1:300), CD19 (clone HIB19, 1:300), CD56 (clone HCD56, 1:300), CX3CR1 (clone 2A9-1, 1:300), and HLA-DR (clone L243, 1:300). Human classical monocytes were identified as (CD3/CD4/CD8a/CD19/CD56)low (CCR2/HLA-DR)high CX3CR1low CD14++ CD16−, intermediated monocytes as (CD3/CD4/CD8a/CD19/CD56)low (CX3CR1/HLA-DR)high CCR2low CD14++ CD16+, and nonclassical monocytes as (CD3/CD4/CD8a/CD19/CD56)low (CX3CR1/HLA-DR)high CCR2low CD14+ CD16++.

For a leukocyte staining on processed murine blood, spleen, and bone marrow samples, cell suspensions were stained at 4°C in FACS buffer with CD11b (clone M1/70, 1:600), CD19 (clone 1D3, 1:600), CD90.2 (clone 53–2.1, 1:1200), CD115 (clone AFS98, 1:600), Ly6C (clone AL-21 or HK1.4, 1:600), and Ly6G (clone 1A8, 1:600). For a myeloid cell staining on processed heart samples, isolated cells were first labeled with mouse hematopoietic lineage markers including PE-conjugated anti-mouse antibodies directed against B220 (clone RA3-6B2, 1:600), CD49b (clone DX5, 1:1200), CD90.2 (clone 53–2.1, 1:3000), Ly6G (clone 1A8, 1:600), NK1.1 (clone PK136, 1:600), and Ter-119 (clone TER-119, 1:600). This was followed by a second staining for CD11b (clone M1/70, 1:600), CD45.2 (clone 104, 1:600), F4/80 (clone BM8, 1:600), Ly6C (clone AL-21 or HK1.4, 1:600), and MHCII (clone M5/114.15.2, 1:600). For a fibroblast and endothelial cell staining on processed heart samples, isolated cells were stained with CD31 (clone 390, 1:400), CD45 (clone 30-F11, 1:600), and MEFSK4 (clone mEF-SK4, 1:20). To quantify ROS, cells were additionally incubated with CellROX deep-red reagent (1:500; Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 30 min at 37°C. B and T cells were identified as CD19high CD90.2low and CD19low CD90.2high, respectively. Monocytes were defined as (CD19/CD90.2)low CD11bhigh CD115high Ly6Clow/high or (B220/CD49b/CD90.2/Ly6G/NK1.1/Ter-119)low (CD11b/CD45)high F4/80low Ly6Chigh and neutrophils as (CD19/CD90.2)low CD11bhigh CD115low/int Ly6Ghigh or (B220/CD49b/CD90.2/NK1.1/Ter-119)low (CD11b/CD45)high Ly6Ghigh. Cardiac macrophages were identified as (B220/CD49b/CD90.2/Ly6G/NK1.1/Ter-119)low (CD11b/CD45)high F4/80high Ly6Clow/int, cardiac fibroblasts as CD31low CD45low MEFSK4high, and cardiac endothelial cells as CD31high CD45low.

For a HSPC staining, cell suspensions were labeled with biotin-conjugated anti–mouse antibodies directed against B220 (clone RA3-6B2, 1:100), CD4 (clone GK1.5, 1:100), CD8a (clone 53–6.7, 1:100), CD11b (clone M1/70, 1:100), CD11c (clone N418, 1:100), Gr-1 (clone RB6-8C5, 1:100), IL7Rα (clone A7R34, 1:100), NK1.1 (clone PK136, 1:100), and Ter-119 (clone TER-119, 1:100). This was followed by a second staining for CD16/32 (clone 93, 1:100), CD34 (clone RAM34, 1:33), CD48 (clone HM48-1, 1:50), CD115 (clone AFS98, 1:100), CD150 (clone TC15-12F12.2, 1:50), c-Kit (clone 2B8, 1:100), Sca-1 (clone D7, 1:50), and Pacific Orange-conjugated streptavidin (1:100). LSKs were identified as (B220/CD4/CD8a/CD11b/CD11c/Gr-1/IL7Rα/NK1.1/Ter-119)low c-Kithigh Sca-1high and HSCs as (B220/CD4/CD8a/CD11b/CD11c/Gr-1/IL7Rα/NK1.1/Ter-119)low c-Kithigh Sca-1high CD48low CD150high. GMPs were defined as (B220/CD4/CD8a/CD11b/CD11c/Gr-1/IL7Rα/NK1.1/Ter-119)low c-Kithigh Sca-1low (CD16/32/CD34)high CD115low/int and MDPs as (B220/CD4/CD8a/CD11b/CD11c/Gr-1/IL7Rα/NK1.1/Ter-119)low c-Kithigh Sca-1low (CD16/32/CD34)high CD115high. The APC BrdU flow kit (BD Biosciences) was used to quantify BrdU+ HSCs according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Antibodies were purchased from BioLegend, BD Biosciences, eBioscience, Miltenyi Biotec, or Thermo Fisher Scientific. DAPI and LIVE/DEAD Fixable Blue Dead Cell Stain (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used as cell viability markers. Data were acquired on an LSRII (BD Biosciences) and analyzed with FlowJo software.

Cell sorting

To purify cardiac macrophages from control and SAUNA-exposed mice for qPCR analysis, digested tissue samples were first enriched for CD11b+ cells by using Miltenyi CD11b microbeads and MACS columns according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Next, cells were stained with hematopoietic lineage markers, CD45.2, F4/80, and Ly6C and FACS-sorted by using a FACSAria II cell sorter (BD Biosciences; Fig. 7 A). To isolate cardiac macrophages, fibroblasts and endothelial cells from C57BL/6 mice for qPCR and in vitro experiments, digested tissue samples were stained with hematopoietic lineage markers, CD11b, CD31, CD45, F4/80, Ly6C, and MEFSK4 and FACS-sorted by using a FACSAria II cell sorter (Fig. 7 D). DAPI was used as a cell viability marker.

Cell culture

FACS-purified cardiac macrophages were serum starved overnight and incubated with 50 ng/ml murine rIL-10 (PeproTech) for 24 h under normal growth conditions. After 24 h, the cell culture medium was collected, and cells were harvested for qPCR analysis. FACS-purified cardiac fibroblasts were cultured until reaching >80% confluency. After serum starvation, 50 ng/ml rIL-10 or culture medium collected from rIL-10–exposed cardiac macrophages with and without neutralizing anti–OPN antibody (10 µg/ml; catalog number AF808; R&D Systems) or anti–TGFβ antibody (50 µg/ml; catalog number AB-100-NA; R&D Systems) was added and incubated for 24 to 72 h under normal growth conditions.

Histology

To eliminate blood contamination, murine hearts were perfused with 10 ml of ice-cold PBS. The hearts were then excised and embedded in OCT compound. To detect myocardial fibrosis, frozen 6-µm sections were stained with PicroSirius Red (Sigma-Aldrich) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. To identify mouse cardiac macrophages, serial frozen 6-µm sections were prepared, blocked with 4% normal rabbit serum, and incubated with a rat anti–mouse Mac3 antibody (clone M3/84; BD Biosciences) overnight at 4°C, followed by a biotinylated rabbit anti–rat IgG antibody (Vector Laboratories) for 30 min at room temperature. To identify human cardiac macrophages, paraffin-embedded tissue was first deparaffinized, and antigen retrieval was performed by using sodium citrate, pH 6.0 (BD Biosciences). To block endogenous peroxidase activity, the tissue sections were incubated in 1% H2O2 diluted in dH2O for 10 min and rinsed in dH2O and PBS. The sections were then blocked with 4% horse serum in PBS for 30 min at room temperature and incubated with a monoclonal mouse anti–human CD68 antibody (clone KP1; Dako) overnight at 4°C. A biotinylated horse anti–mouse IgG antibody was applied for 30 min at room temperature. For color development, the VectaStain ABC kit (Vector Laboratories) and AEC substrate (Dako) were used. All the slides were counterstained with Harris hematoxylin. To visualize nuclei and delineate cells in mouse hearts, serial frozen 6-µm sections were incubated with DAPI and the membrane stain Alexa Fluor 594 WGA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 10 min at room temperature. Slides were scanned with NanoZoomer 2.0-RS (Hamamatsu), and sections were analyzed at 20× magnification by using ImageJ (NIH) or iVision (BioVision Technologies) software. In detail, the average percentage of positive staining of at least eight randomly selected LV myocardial areas (i.e., region of interest [ROI]) was determined per mouse.

Coverslips seeded with cardiac fibroblasts were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min at room temperature. After washing, cells were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 10 min at room temperature, washed, and blocked in blocking solution (PBS containing 10% goat serum, 0.1% Tween-20, and 0.3 M glycine) for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were then stained with a rabbit anti–mouse α-SMA (clone E184; Abcam) antibody in blocking solution for 1 h at room temperature, followed by incubation with an Alexa Fluor 647 goat anti–rabbit IgG secondary antibody (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing, cells were stained with Alexa Fluor 555 Phalloidin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for 20 min at room temperature, and DAPI was applied for nuclear counterstaining. All images were captured using an Olympus FV1000 microscope and analyzed with ImageJ software.

Fluorescence reflectance imaging

Heart slices were imaged by using a planar fluorescence reflectance imaging system (Olympus OV-110) with a 680-nm excitation wavelength. Acquired images were analyzed with ImageJ software.

CFU assay

CFU assays were performed by using a semisolid cell culture medium (Methocult M3434; Stem Cell Technology) following the manufacturer’s protocol. In detail, 50 µl peripheral blood was collected, and red blood cells were lysed with 1× red blood cell lysis buffer. Cells were resuspended in Iscove’s Modified Dulbecco’s Medium (Stem Cell Technology) supplemented with 2% FBS and 1% penicillin/streptomycin, plated on 35-mm dishes in duplicate and incubated at 37°C for 12 d. Colonies were counted by using a low-magnification inverted microscope.

PCR confirmation of the deletion of the Il10 allele

Genomic DNA from FACS-purified cardiac macrophages was isolated with the DNeasy Blood & Tissue kit (Qiagen) and used in PCR with two pairs of Il10-specific primers: 5′-ACTGGCTCAGCACTGCTATGC-3′ and 5′-GCCTTCTTTGGACCTCCATACCAG-3′ for detecting Il10fl or Il10wt alleles and 5′-CAGGATTTGACAGTGCTAGAGC-3′ and 5′-AAACCCAGCTCAAATCTCCTGC-3′ for detecting the Il10 allele lacking the floxed fragment. To normalize the amount of input DNA, specific primers to the Cx3cr1wt gene were used: 5′-AAGACTCACGTGGACCTGCT-3′ and 5′-AGGATGTTGACTTCCGAGTTG-3′.

qPCR

Total RNA from the heart and bone marrow was extracted by using the RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen) or from FACS-purified cells by using the RNeasy Micro kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. A mouse Fibrosis RT2 Profiler array (Qiagen) was used to examine the expression profile of fibrosis-related genes in FACS-purified cardiac macrophages. Reverse transcription, qPCR, and data analysis were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions. For single-gene qPCR analysis, first-strand cDNA was synthesized by using the High-Capacity RNA-to-cDNA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The following TaqMan gene expression assays (Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used to quantify target genes: Angpt1 (Mm00456503_m1), Anp (Mm01255747_g1), Bnp (Mm01255770_g1), Ccl2 (Mm00441242_m1), Col1a2 (Mm00483888_m1), Cxcl12 (Mm00445553_m1), Fn1 (Mm01256744_m1), Gapdh (Mm99999915_g1), Icam2 (Mm00494862_m1), Il10 (Mm00439614_m1), Il10ra (Mm00434151_m1), Il10rb (Mm00434157_m1), Opn (Mm00436767_m1), Scf (Mm00442972_m1), Sele (Mm00441278_m1), Selp (Mm00441295_m1), Tgfb1 (Mm01178820_m1), and Vcam1 (Mm01320970_m1). The relative changes were normalized to Gapdh mRNA by using the 2-ΔΔCt method.

Microarray data analysis

Processed microarray data (signal values calculated by Agilent Feature Extraction V11.5.1.1, quantile-normalized and log2-transformed) were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession no. GSE53787). Gene set enrichment analysis (Subramanian et al., 2005) was performed by using standard parameters (gene set permutation, signal-to-noise ratio as a ranking metric). Genes involved in regulation of TGFβ production (Gene ontology term GO:0032914) were downloaded from the QuickGO Browser (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/QuickGO/).

Statistics

All statistical analyses were conducted with GraphPad Prism software. Data are presented as mean ± SD. No statistical method was used to predetermine the sample size. We excluded outliers that were identified by the ROUT method (Q = 1%). For two-group comparisons, two-tailed unpaired Student’s t tests, two-tailed unpaired t tests with Welch’s correction, or two-tailed nonparametric Mann–Whitney tests were used. For comparing more than two groups, ANOVA tests followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test were applied. Correlations were calculated by using the Pearson correlation coefficient. P values ≤ 0.05 were considered significant.

Online supplemental material

Fig. S1 shows human data. Fig. S2 shows the cardiac phenotype in mice exposed to SAUNA. Fig. S3 shows that macrophage-restricted IL-10 deletion does not alter SAUNA-induced hypertrophy. Table S1 contains the clinical characteristics of patients recruited for LV myocardial biopsies.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank M. Weglarz, M. Handley, and A. Galvin for assistance with cell sorting.

This work was funded in part by federal funds from the NIH (5T32076136-12 to M.T. Osborne; HL122987, HL135886, and TR000901 to A. Rosenzweig; HL117153 to F. Sam; and HL117829, HL125428, and HL096576 to M. Nahrendorf). M. Hulsmans was supported by the Research Foundation - Flanders (12A0213N) and by an MGH ECOR Tosteson and Fund for Medical Discovery Fellowship (2017A052660). H.B. Sager was funded by Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (SA1668/2-1). J.D. Roh was supported by the Frederick and Ines Yeatts Fund for Innovative Research and an American Heart Association Fellow-to-Faculty Award. N.E. Houstis was supported by a Margaret Q. Landenberger Foundation Award. A. Rosenzweig was funded by the American Heart Association (14CSA20500002 and 16SFRN31720000). M. Nahrendorf was supported by the MGH Research Scholar Program.

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Author contributions: M. Hulsmans, H.B. Sager, and J.D. Roh performed experiments, and collected, analyzed, and discussed data. M. Valero-Muñoz, N.E. Houstis, Y. Iwamoto, Y. Sun, R.M. Wilson, G. Wojtkiewicz, B. Tricot, C. Vinegoni, and K. Naxerova performed experiments and collected data. M.T. Osborne, J. Hung, M.R. Zile, A.D. Bradshaw, A. Tawakol, and F. Sam provided human samples and data. D.E. Sosnovik, R. Liao, A. Tawakol, R. Weissleder, A. Rosenzweig, F.K. Swirski, F. Sam, and M. Nahrendorf conceived experiments and discussed results and strategy. M. Nahrendorf conceived, designed, and directed the study. M. Hulsmans and M. Nahrendorf wrote the manuscript, which was revised and approved by all authors.

References

- Alili L., Sack M., Puschmann K., and Brenneisen P.. 2014. Fibroblast-to-myofibroblast switch is mediated by NAD(P)H oxidase generated reactive oxygen species. Biosci. Rep. 34:00089 10.1042/BSR20130091 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ather S., Chan W., Bozkurt B., Aguilar D., Ramasubbu K., Zachariah A.A., Wehrens X.H., and Deswal A.. 2012. Impact of noncardiac comorbidities on morbidity and mortality in a predominantly male population with heart failure and preserved versus reduced ejection fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 59:998–1005. 10.1016/j.jacc.2011.11.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerman I., Bhattacharya D., Zandi S., Sigvardsson M., Weissman I.L., Bryder D., and Rossi D.J.. 2010. Functionally distinct hematopoietic stem cells modulate hematopoietic lineage potential during aging by a mechanism of clonal expansion. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 107:5465–5470. 10.1073/pnas.1000834107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beerman I., Bock C., Garrison B.S., Smith Z.D., Gu H., Meissner A., and Rossi D.J.. 2013. Proliferation-dependent alterations of the DNA methylation landscape underlie hematopoietic stem cell aging. Cell Stem Cell. 12:413–425. 10.1016/j.stem.2013.01.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dykstra B., Olthof S., Schreuder J., Ritsema M., and de Haan G.. 2011. Clonal analysis reveals multiple functional defects of aged murine hematopoietic stem cells. J. Exp. Med. 208:2691–2703. 10.1084/jem.20111490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg T., Abdellatif M., Schroeder S., Primessnig U., Stekovic S., Pendl T., Harger A., Schipke J., Zimmermann A., Schmidt A., et al. 2016. Cardioprotection and lifespan extension by the natural polyamine spermidine. Nat. Med. 22:1428–1438. 10.1038/nm.4222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emami H., Singh P., MacNabb M., Vucic E., Lavender Z., Rudd J.H., Fayad Z.A., Lehrer-Graiwer J., Korsgren M., Figueroa A.L., et al. 2015. Splenic metabolic activity predicts risk of future cardiovascular events: demonstration of a cardiosplenic axis in humans. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 8:121–130. 10.1016/j.jcmg.2014.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Epelman S., Lavine K.J., Beaudin A.E., Sojka D.K., Carrero J.A., Calderon B., Brija T., Gautier E.L., Ivanov S., Satpathy A.T., et al. 2014. Embryonic and adult-derived resident cardiac macrophages are maintained through distinct mechanisms at steady state and during inflammation. Immunity. 40:91–104. 10.1016/j.immuni.2013.11.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francis G.S. 2011. Neurohormonal control of heart failure. Cleve. Clin. J. Med. 78(Suppl. 1):S75–S79. 10.3949/ccjm.78.s1.13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartupee J., and Mann D.L.. 2016. Role of inflammatory cells in fibroblast activation. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 93:143–148. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.11.016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heart Failure Society of America,Lindenfeld J., Albert N.M., Boehmer J.P., Collins S.P., Ezekowitz J.A., Givertz M.M., Katz S.D., Klapholz M., Moser D.K., Rogers J.G., et al. 2010. HFSA 2010 Comprehensive Heart Failure Practice Guideline. J. Card. Fail. 16:e1–e194. 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidt T., Courties G., Dutta P., Sager H.B., Sebas M., Iwamoto Y., Sun Y., Da Silva N., Panizzi P., van der Laan A.M., et al. 2014. Differential contribution of monocytes to heart macrophages in steady-state and after myocardial infarction. Circ. Res. 115:284–295. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.303567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsmans M., Sam F., and Nahrendorf M.. 2016. Monocyte and macrophage contributions to cardiac remodeling. J. Mol. Cell. Cardiol. 93:149–155. 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2015.11.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hulsmans M., Clauss S., Xiao L., Aguirre A.D., King K.R., Hanley A., Hucker W.J., Wülfers E.M., Seemann G., Courties G., et al. 2017. Macrophages facilitate electrical conduction in the heart. Cell. 169:510–522.e20. 10.1016/j.cell.2017.03.050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal S., Fontanillas P., Flannick J., Manning A., Grauman P.V., Mar B.G., Lindsley R.C., Mermel C.H., Burtt N., Chavez A., et al. 2014. Age-related clonal hematopoiesis associated with adverse outcomes. N. Engl. J. Med. 371:2488–2498. 10.1056/NEJMoa1408617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalogeropoulos A., Georgiopoulou V., Psaty B.M., Rodondi N., Smith A.L., Harrison D.G., Liu Y., Hoffmann U., Bauer D.C., Newman A.B., et al. Health ABC Study Investigators . 2010. Inflammatory markers and incident heart failure risk in older adults: The Health ABC (Health, Aging, and Body Composition) study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 55:2129–2137. 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.12.045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasner M., Westermann D., Lopez B., Gaub R., Escher F., Kühl U., Schultheiss H.P., and Tschöpe C.. 2011. Diastolic tissue Doppler indexes correlate with the degree of collagen expression and cross-linking in heart failure and normal ejection fraction. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 57:977–985. 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong P., Christia P., and Frangogiannis N.G.. 2014. The pathogenesis of cardiac fibrosis. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 71:549–574. 10.1007/s00018-013-1349-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenga Y., Koh A., Perera A.S., McCulloch C.A., Sodek J., and Zohar R.. 2008. Osteopontin expression is required for myofibroblast differentiation. Circ. Res. 102:319–327. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.160408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y. 2009. Clinical significance of diffusely increased splenic uptake on FDG-PET. Nucl. Med. Commun. 30:763–769. 10.1097/MNM.0b013e32832fa254 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y., Chiao Y.A., Clark R., Flynn E.R., Yabluchanskiy A., Ghasemi O., Zouein F., Lindsey M.L., and Jin Y.F.. 2015. Deriving a cardiac ageing signature to reveal MMP-9-dependent inflammatory signalling in senescence. Cardiovasc. Res. 106:421–431. 10.1093/cvr/cvv128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mallat Z., Besnard S., Duriez M., Deleuze V., Emmanuel F., Bureau M.F., Soubrier F., Esposito B., Duez H., Fievet C., et al. 1999. Protective role of interleukin-10 in atherosclerosis. Circ. Res. 85:e17–e24. 10.1161/01.RES.85.8.e17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMurray J.J., Carson P.E., Komajda M., McKelvie R., Zile M.R., Ptaszynska A., Staiger C., Donovan J.M., and Massie B.M.. 2008. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Clinical characteristics of 4133 patients enrolled in the I-PRESERVE trial. Eur. J. Heart Fail. 10:149–156. 10.1016/j.ejheart.2007.12.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore K.W., de Waal Malefyt R., Coffman R.L., and O’Garra A.. 2001. Interleukin-10 and the interleukin-10 receptor. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 19:683–765. 10.1146/annurev.immunol.19.1.683 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffarian D., Benjamin E.J., Go A.S., Arnett D.K., Blaha M.J., Cushman M., Das S.R., de Ferranti S., Després J.P., Fullerton H.J., et al. 2016. Executive Summary: Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics--2016 Update: A report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 133:447–454. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mulder W.J., Jaffer F.A., Fayad Z.A., and Nahrendorf M.. 2014. Imaging and nanomedicine in inflammatory atherosclerosis. Sci. Transl. Med. 6:239sr1 10.1126/scitranslmed.3005101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray P.J., and Wynn T.A.. 2011. Protective and pathogenic functions of macrophage subsets. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 11:723–737. 10.1038/nri3073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagueh S.F., Smiseth O.A., Appleton C.P., Byrd B.F. III, Dokainish H., Edvardsen T., Flachskampf F.A., Gillebert T.C., Klein A.L., Lancellotti P., et al. 2016. Recommendations for the evaluation of left ventricular diastolic function by echocardiography: An update from the American Society of Echocardiography and the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging. J. Am. Soc. Echocardiogr. 29:277–314. 10.1016/j.echo.2016.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtsu H., Frank G.D., Utsunomiya H., and Eguchi S.. 2005. Redox-dependent protein kinase regulation by angiotensin II: Mechanistic insights and its pathophysiology. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 7:1315–1326. 10.1089/ars.2005.7.1315 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owan T.E., Hodge D.O., Herges R.M., Jacobsen S.J., Roger V.L., and Redfield M.M.. 2006. Trends in prevalence and outcome of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. N. Engl. J. Med. 355:251–259. 10.1056/NEJMoa052256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus W.J., and Tschöpe C.. 2013. A novel paradigm for heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Comorbidities drive myocardial dysfunction and remodeling through coronary microvascular endothelial inflammation. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62:263–271. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.02.092 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paulus W.J., Tschöpe C., Sanderson J.E., Rusconi C., Flachskampf F.A., Rademakers F.E., Marino P., Smiseth O.A., De Keulenaer G., Leite-Moreira A.F., et al. 2007. How to diagnose diastolic heart failure: A consensus statement on the diagnosis of heart failure with normal left ventricular ejection fraction by the Heart Failure and Echocardiography Associations of the European Society of Cardiology. Eur. Heart J. 28:2539–2550. 10.1093/eurheartj/ehm037 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto A.R., Godwin J.W., Chandran A., Hersey L., Ilinykh A., Debuque R., Wang L., and Rosenthal N.A.. 2014. Age-related changes in tissue macrophages precede cardiac functional impairment. Aging (Albany N.Y.). 6:399–413. 10.18632/aging.100669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pinto A.R., Ilinykh A., Ivey M.J., Kuwabara J.T., D’Antoni M.L., Debuque R., Chandran A., Wang L., Arora K., Rosenthal N.A., and Tallquist M.D.. 2016. Revisiting cardiac cellular composition. Circ. Res. 118:400–409. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.307778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roers A., Siewe L., Strittmatter E., Deckert M., Schlüter D., Stenzel W., Gruber A.D., Krieg T., Rajewsky K., and Müller W.. 2004. T cell-specific inactivation of the interleukin 10 gene in mice results in enhanced T cell responses but normal innate responses to lipopolysaccharide or skin irritation. J. Exp. Med. 200:1289–1297. 10.1084/jem.20041789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sager H.B., Hulsmans M., Lavine K.J., Moreira M.B., Heidt T., Courties G., Sun Y., Iwamoto Y., Tricot B., Khan O.F., et al. 2016. Proliferation and recruitment contribute to myocardial macrophage expansion in chronic heart failure. Circ. Res. 119:853–864. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.309001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz C., Gomez Perdiguero E., Chorro L., Szabo-Rogers H., Cagnard N., Kierdorf K., Prinz M., Wu B., Jacobsen S.E., Pollard J.W., et al. 2012. A lineage of myeloid cells independent of Myb and hematopoietic stem cells. Science. 336:86–90. 10.1126/science.1219179 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma K., and Kass D.A.. 2014. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction: Mechanisms, clinical features, and therapies. Circ. Res. 115:79–96. 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.115.302922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shiraishi M., Shintani Y., Shintani Y., Ishida H., Saba R., Yamaguchi A., Adachi H., Yashiro K., and Suzuki K.. 2016. Alternatively activated macrophages determine repair of the infarcted adult murine heart. J. Clin. Invest. 126:2151–2166. 10.1172/JCI85782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Signore S., Sorrentino A., Borghetti G., Cannata A., Meo M., Zhou Y., Kannappan R., Pasqualini F., O’Malley H., Sundman M., et al. 2015. Late Na(+) current and protracted electrical recovery are critical determinants of the aging myopathy. Nat. Commun. 6:8803 10.1038/ncomms9803 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramanian A., Tamayo P., Mootha V.K., Mukherjee S., Ebert B.L., Gillette M.A., Paulovich A., Pomeroy S.L., Golub T.R., Lander E.S., and Mesirov J.P.. 2005. Gene set enrichment analysis: A knowledge-based approach for interpreting genome-wide expression profiles. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 102:15545–15550. 10.1073/pnas.0506580102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L., Louie M.C., Vannella K.M., Wilke C.A., LeVine A.M., Moore B.B., and Shanley T.P.. 2011. New concepts of IL-10-induced lung fibrosis: Fibrocyte recruitment and M2 activation in a CCL2/CCR2 axis. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell. Mol. Physiol. 300:L341–L353. 10.1152/ajplung.00122.2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tawakol A., Fayad Z.A., Mogg R., Alon A., Klimas M.T., Dansky H., Subramanian S.S., Abdelbaky A., Rudd J.H., Farkouh M.E., et al. 2013. Intensification of statin therapy results in a rapid reduction in atherosclerotic inflammation: Results of a multicenter fluorodeoxyglucose-positron emission tomography/computed tomography feasibility study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 62:909–917. 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.04.066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Troidl C., Möllmann H., Nef H., Masseli F., Voss S., Szardien S., Willmer M., Rolf A., Rixe J., Troidl K., et al. 2009. Classically and alternatively activated macrophages contribute to tissue remodelling after myocardial infarction. J. Cell. Mol. Med. 13(9b, 9B):3485–3496. 10.1111/j.1582-4934.2009.00707.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valero-Muñoz M., Li S., Wilson R.M., Hulsmans M., Aprahamian T., Fuster J.J., Nahrendorf M., Scherer P.E., and Sam F.. 2016. Heart failure with preserved ejection fraction induces beiging in adipose tissue. Circ Heart Fail. 9:e002724 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002724 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vasan R.S., Larson M.G., Benjamin E.J., Evans J.C., Reiss C.K., and Levy D.. 1999. Congestive heart failure in subjects with normal versus reduced left ventricular ejection fraction: Prevalence and mortality in a population-based cohort. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 33:1948–1955. 10.1016/S0735-1097(99)00118-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verma S.K., Krishnamurthy P., Barefield D., Singh N., Gupta R., Lambers E., Thal M., Mackie A., Hoxha E., Ramirez V., et al. 2012. Interleukin-10 treatment attenuates pressure overload-induced hypertrophic remodeling and improves heart function via signal transducers and activators of transcription 3-dependent inhibition of nuclear factor-κB. Circulation. 126:418–429. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.112.112185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Westermann D., Lindner D., Kasner M., Zietsch C., Savvatis K., Escher F., von Schlippenbach J., Skurk C., Steendijk P., Riad A., et al. 2011. Cardiac inflammation contributes to changes in the extracellular matrix in patients with heart failure and normal ejection fraction. Circ Heart Fail. 4:44–52. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.109.931451 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wick G., Grundtman C., Mayerl C., Wimpissinger T.F., Feichtinger J., Zelger B., Sgonc R., and Wolfram D.. 2013. The immunology of fibrosis. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 31:107–135. 10.1146/annurev-immunol-032712-095937 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancy C.W., Jessup M., Bozkurt B., Butler J., Casey D.E. Jr., Colvin M.M., Drazner M.H., Filippatos G., Fonarow G.C., Givertz M.M., et al. WRITING COMMITTEE MEMBERS . 2016. 2016 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update on New Pharmacological Therapy for Heart Failure: An Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America. Circulation. 134:e282–e293. 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]