Abstract

Background/Aims

The aim of this study was to assess the ability of neuropsychological tests to differentiate autopsy-defined Alzheimer disease (AD) from subcortical ischemic vascular dementia (SIVD).

Methods

From a sample of 175 cases followed longitudinally that underwent autopsy, we selected 23 normal controls (NC), 20 SIVD, 69 AD, and 10 mixed cases of dementia. Baseline neuropsychological tests, including Memory Assessment Scale word list learning test, control oral word association test, and animal fluency, were compared between the three autopsy-defined groups.

Results

The NC, SIVD, and AD groups did not differ by age or education. The SIVD and AD groups did not differ by the Global Clinical Dementia Rating Scale. Subjects with AD performed worse on delayed recall (p < 0.01). A receiver operating characteristics analysis comparing the SIVD and AD groups including age, education, difference between categorical (animals) versus phonemic fluency (letter F), and the first recall from the word learning test distinguished the two groups with a sensitivity of 85%, specificity of 67%, and positive likelihood ratio of 2.57 (AUC = 0.789, 95% CI 0.69–0.88, p < 0.0001).

Conclusion

In neuropathologically defined subgroups, neuropsychological profiles have modest ability to distinguish patients with AD from those with SIVD.

Keywords: Alzheimer disease, Subcortical ischemic vascular dementia, Neuropathology, Vascular cognitive impairment, Memory performance

Introduction

Alzheimer disease [AD] is the most common type of dementia in individuals older than 65 years of age. Vascular cognitive impairment (VCI) is the second most common type [1]. Differentiating between AD and subcortical ischemic vascular dementia (SIVD) is important from a therapeutic and prognostic point of view. VCI (including SIVD) compared to pure AD carries a significantly higher rate of morbidity and mortality based on its more frequent association with vascular risk factors as well as motor impairment. More specifically, vascular dementia [VaD] is associated with 50% lower median survival [3–4 vs. 6–7 years], greater healthcare costs, and higher rates of comorbidity, institutionalization, and caregiver use [2].

The neuropsychological profile of AD is characterized by memory impairment, most specifically of the episodic or declarative type, associated with deficits in other cognitive areas including language, visuospatial, and executive function [3]. VCI falls on a spectrum from mild forms that include vascular mild cognitive impairment to full-blown VaD [4]. In contrast with AD, the neurobehavioral profile for VCI is variable, mainly influenced by the location of the cerebral vascular injury including WMD [white matter disease], SBI [silent brain infarcts], subcortical lacunar strokes, or large vessel stroke resulting from ischemia or hemorrhage [5].

SIVD is a specific type of VaD defined by vascular brain injury mostly confined to the subcortical gray and white matter. It includes Binswanger’s syndrome, lacunar strokes, and strategic infarcts causing dementia due to small vessel disease [6]. Poor executive function that includes poor planning, difficulties with working memory, attention, problem solving, verbal reasoning, inhibition, mental flexibility, multitasking, monitoring of actions, task changing, and decreased speed of processing are preferentially affected in these patients [4]. Previous studies have demonstrated that patients with SIVD have a dysexecutive pattern of memory impairment of a retrieval type that responds better to cueing or recognition rather than the episodic memory deficit in AD that is one of learning affecting the encoding and storage of information [7].

Multiple prior studies have attempted to differentiate SIVD from AD. Several methodological difficulties have been encountered, including making an appropriate diagnosis that is based on premortem clinical characteristics and neuropsychological profile findings. Ultimately, definite diagnosis of both dementias is based on neuropathology findings at postmortem autopsy. It has been difficult to eliminate the confounding effects of mixed pathology [Alzheimer and vascular in the same patient] because mixed pathology with AD and vascular changes frequently coexist [8, 9].

In the current study, we focus on the differentiation of pathologically confirmed AD versus SIVD based on the neuropsychological profiles, because of their noninvasiveness and ready availability, and the ability of a primary care practitioner to assess these simple cognitive measures at the bedside. We hypothesized that patients with SIVD would have more deficits in memory retrieval and phonemic fluency compared to patients with AD that would have more deficits in spontaneous delayed recall and categorical fluency. To determine whether the pattern of cognitive performance might reliably inform the diagnosis in individual cases, we performed receiver operator curve analyses.

Methods

Autopsy Cases

The study sample (n = 143) was derived from the first 175 consecutive autopsy cases in the neuropathology database from February 1997 to January 2011, from a prospective longitudinal study of SIVD, AD, and normal aging in an ischemic vascular dementia program project. Inclusion criteria for initial enrolment included age >55 years, English speaking, cognitively normal or cognitively impaired (Clinical Dementia Rating [CDR] ≤2] due to either SIVD or AD. Exclusion criteria included severe dementia (CDR >2), history of alcohol or substance abuse, head trauma with loss of consciousness >15 min, severe medical illness, neurologic or psychiatric disorders except dementia, and persons currently taking medications likely to affect cognitive function. For the purpose of this study, we selected cases with neuropathological diagnosis of pure SIVD, pure AD, mixed AD + SIVD, and normal aging. Hippocampal sclerosis (HS) was noted and initially considered as a common comorbid condition.

Written informed consent was obtained from all subjects or surrogate decision maker after the protocols were approved by the institutional review boards at each participating institution.

Neuropathological Evaluation

Each case was reviewed at Consensus Neuropathology Conferences, including 2 Board-certified neuropathologists blinded to clinical diagnosis. For each autopsy case, Braak and Braak stage (B&B), Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer Disease (CERAD)-neuritic plaque, and Lewy body score were recorded. The severity of cerebrovascular ischemic brain injury was rated using a vascular brain injury pathology scoring (CVDPS) developed within this project, and previously described [10]. Subscores for cystic infarcts, lacunar infarcts, and microinfarcts summed the individual scores across all brain regions and normalized to a scale of 0–100. The 3 subscores were summed to a total CVDPS score (0–300). Acute infarcts or hemorrhages near the time of death were noted, but not included in the CVDPS score.

Pathological Diagnosis

Among the first 175 consecutive autopsy cases, 1 case with frontotemporal lobar degeneration, 11 with dementia with Lewy bodies (score ≥3), 1 case with AD CDR = 3.0, and 19 cases with no complete neuropsychological testing data were excluded from this analysis. Cutoff scores were selected for B&B and CVDPS scores among 144 cases to operationally define 5 pathological diagnosis groups. We also performed sensitivity analyses to assess whether different cutoff scores would significantly change the results.

We used B&B ≥4 to define the AD group (n = 69), and CVDPS score ≥20, as described previously [11], to define the CVD group (n = 20). Cases with B&B ≥4 and CVDPS score ≥20 were defined as the MIXED group (cases with CVD and AD, n = 10). Cases with B&B <4 and CVDPS <20 were classified as having no significant pathological abnormality. We further subdivided the latter group into normal controls (NC; cognitively normal and no significant pathology, n = 23) and other (cognitively impaired without significant pathology, n = 21). HS was found across all of the comparison groups, occurring in 2 NC, 4 SIVD, 19 AD, 3 mixed cases, and 9 in the “other” category. The time (mean, standard deviation) between initial neuropsychological evaluation and death for each group is included in Table 1.

Table 1.

Sample characteristics at the initial neuropsychological testing

| NC (n = 23) |

SIVD (n = 20) |

AD (n = 69) |

MIXED (n = 10) |

Other (n = 21) |

p value1 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at neuropsychological test, years | 78.1 ± 4.9 | 79.0± 6.9 | 80.0 ±6.9 | 80.4 ± 7.0 | 81.3± 6.2 | 0.55 |

| Female, n (%) | 16 (69.6) | 5 (25.0) | 24 (34.8) | 5 (50.0) | 10 (47.6) | 0.02 |

| Education, years | 14.9 ± 3.2 | 15.3± 2.9 | 14.7 ±3.4 | 15.3 ± 2.9 | 13.9± 3.2 | 0.68 |

| MMSE | 29.0 ± 4.6 | 25.7± 6.0 | 23.8 ±4.5 | 20.1 ± 2.8 | 25.4± 4.2 | <0.0001 |

| Initial neuropsychological evaluation to death, years | 7.8 ± 3.8 | 4.2± 3.9 | 5.7 ±3.0 | 4.8 ± 2.2 | 3.8± 2.8 | 0.0004 |

| Global CDR | 0.0 | 0.6± 0.8 | 0.8 ±0.5 | 1.2 ± 0.6 | 0.8± 0.6 | <0.0001 |

| Global cognition | 99.3 ± 11.7 | 85± 22.3 | 77 ±21.7 | 52 ± 13.4 | 76.4± 22.2 | <0.0001 |

| Verbal memory | 106 ± 12.8 | 84.6± 23.6 | 67.9 ±21.3 | 56.7 ± 10.3 | 72.4± 21.1 | <0.0001 |

| Visual memory | 100.2 ± 11.3 | 79.5± 22.1 | 67.1 ±18.4 | 51.6 ± 7.8 | 71.5± 17.1 | <0.0001 |

| Executive function | 100.8 ± 14 | 79.3± 23.2 | 81.2 ±18.5 | 61.5 ± 14 | 76.1± 20.2 | <0.0001 |

| Hippocampal sclerosis2, n (%) | 2 (8.7) | 4 (20.0) | 19 (27.5) | 3 (30.0) | 9 (42.9) | 0.48 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD or as stated. NC, normal controls; SIVD, subcortical ischemic vascular dementia; AD, Alzheimer disease; MIXED, cases with evidence of AD/SIVD pathology on autopsy; other, cognitively impaired individuals without significant pathological findings.

Obtained from analysis of variance for continuous variables and from χ2 tests for categorical variables.

Defined at autopsy.

Neuropsychological Tests

A battery of standardized neuropsychological tests had been administered every other year for participants less than 80 years old and every year for participants at least 80 years old.

Baseline neuropsychological tests, including the Memory Assessment Scale word list learning test, FAS phonemic fluency, and animal category fluency, were compared between the four autopsy-defined groups. We also created a measure of the difference (DIFF) between categorical versus phonemic fluency: DIFF = Category Verbal Fluency Animals total - Phonemic Fluency FAS. Measures of global cognition, verbal memory, and executive function were created using item response theory as previously described [12].

Statistical Analysis

Sample characteristics and neuropsychological profiles were compared among the pathological groups using analysis of variance (ANOVA) for continuous variables and χ2 tests for categorical variables. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed with Tukey adjustment. Neuropsychological tests, with p < 0.20 from the comparison between SIVD and AD groups, were selected into the forward stepwise logistic regression model to identify independent contributing tests in differentiating SIVD from AD. Subsequently, we used the receiver operating characteristics (ROC) curve to assess the ability of these independent contributing tests to predict postmortem diagnosis of SIVD. Age and education were included as covariates in the final model. An ROC curve plots a test’s false-positive rate (1 - specificity) versus its true-positive rate (sensitivity). Each point on the curve represents the sensitivity and false-positive rate at a certain decision threshold. All statistical testing was performed at a 5% level of significance using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Clinical Characteristics

On the basis of pathological ratings, the sample was differentiated into 23 NC, 20 patients with SIVD, 69 patients with AD, 10 with mixed dementia, and 21 were classified as other (cognitively impaired without significant pathology). The groups did not differ by age, but there was a predominance of males in the dementia groups relative to controls (Table 1). Patient groups were also distinguished by lower MMSE and Global CDR.

Neuropsychological Profiles

Table 2 shows the different neuropsychological profiles between the NC, SIVD, and AD groups, in addition to comparisons between the NC versus AD, NC versus SIVD, and SIVD versus AD. Both the SIVD and AD groups performed worse in all neuropsychological measures when compared with NC. Global measures of cognition and verbal and visual memories were statistically significantly different across all the three comparison groups. No significant difference was seen in measures of executive function between the AD and SIVD groups (SIVD = 79.7 ±18.8; AD = 81.4 ± 18.8; p = 0.93). Subjects with AD performed worse on delayed recall (mean total recall SIVD = 43.5 ± 13.4; AD = 33.3 ± 13.3; p < 0.01). Subjects with SIVD performed better on cued recall (SIVD = 8.3 ± 3.3; AD = 5.6 ± 3.3; p < 0.01).

Table 2.

Comparison of neuropsychological profiles among NC, SIVD, and AD

| Neuropsychological test | NC (n = 23) |

SIVD (n = 20) |

AD (n = 69) |

p value1 | NC vs. SIVD | SIVD vs. AD | NC vs. AD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Composite measures | |||||||

| Global cognition | 99.3 ± 21.1 | 85 ± 20.5 | 77± 20.4 | 0.0001 | 0.08 | 0.28 | <0.01 |

| Verbal memory | 105.1 ± 21.2 | 85.1 ± 20.5 | 68± 20.4 | <0.0001 | 0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Visual memory | 99.6 ± 18.6 | 79.8 ± 18 | 67.2± 18 | <0.0001 | <0.01 | 0.03 | <0.01 |

| Executive function | 99.9 ± 19.4 | 79.7 ± 18.8 | 81.4± 18.8 | 0.0004 | <0.01 | 0.93 | <0.01 |

| Learning test | |||||||

| Mean total recall | 56.8 ± 13.8 | 43.5 ± 13.4 | 33.3± 13.3 | <0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| Number of words remembered during trial 6 | 11.1 ± 2.8 | 8.6 ± 2.7 | 6.5± 2.7 | <0.0001 | 0.02 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| Delayed recall | 10.4 ± 4 | 7.2 ± 3.9 | 3.5± 3.9 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Forget | 0.6 ± 2.4 | 1.4 ± 2.3 | 3± 2.3 | <0.0001 | 0.56 | 0.02 | <0.01 |

| Retention | 1 ± 0.4 | 0.7 ± 0.4 | 0.4± 0.4 | <0.0001 | 0.23 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| List recall | |||||||

| Recall trial correct | 10.5 ± 3.9 | 6.6 ± 3.7 | 3.4± 3.7 | <0.0001 | <0.01 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Cued recall trial correct | 10.7 ± 3.4 | 8.3 ± 3.3 | 5.6± 3.3 | <0.0001 | 0.06 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Saving | 0.2 ± 2.1 | 1.7 ± 2 | 2.3± 2 | 0.0003 | 0.06 | 0.47 | <0.01 |

| Trial 1 correct | 6.1 ± 2 | 5.1 ± 1.9 | 3.5± 1.9 | <0.0001 | 0.22 | <0.01 | <0.01 |

| Trial 2 correct | 8.7 ± 2.3 | 6.8 ± 2.3 | 5.1± 2.3 | <0.0001 | 0.03 | 0.01 | <0.01 |

| Trial 3 correct | 9.6 ± 2.6 | 7.3 ± 2.5 | 5.6± 2.5 | <0.0001 | 0.01 | 0.03 | <0.01 |

| Verbal Fluency | |||||||

| Letter F (total) | 14.4 ± 5 | 10 ± 4.9 | 11.1± 4.9 | 0.011 | 0.02 | 0.66 | 0.02 |

| Letter A (total) | 12.1 ± 4.8 | 8.7 ± 4.7 | 9.2± 4.7 | 0.032 | 0.07 | 0.94 | 0.04 |

| Letter S (total) | 15.5 ± 5.7 | 10.9 ± 5.5 | 11.9± 5.5 | 0.018 | 0.03 | 0.76 | 0.03 |

| Phonemic Fluency FAS | 14 ± 4.8 | 10.1 ± 4.6 | 10.7± 4.6 | 0.012 | 0.03 | 0.87 | 0.02 |

| Verbal Fluency Animals | 17.3 ± 6.5 | 14.4 ± 6.3 | 12.4± 6.3 | 0.008 | 0.32 | 0.42 | 0.01 |

| DIFF | 2.9 ± 6.5 | 4.3 ± 6.3 | 1.3± 6.3 | 0.15 | |||

| Digit Span | |||||||

| Forward | 7.6 ± 2.3 | 8 ± 2.2 | 7.5± 2.2 | 0.65 | |||

| Backward | 6.3 ± 2.5 | 5.2 ± 2.4 | 5.3± 2.4 | 0.23 | |||

| Visual Span Backward | 6.6 ± 2.1 | 5.5 ± 2 | 5.3± 2 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 0.92 | 0.03 |

| Dementia Rating Scale | 35.5 ± 6 | 30.8 ± 5.8 | 29± 5.8 | 0.0001 | 0.04 | 0.45 | <0.01 |

Data are presented as mean ± SD. Forgotten, number of words remembered during trial 6 - Delayed recall; retention, Delayed recall/number of words remembered during trial 6; saving, Cued recall trial correct - Recall trial correct; DIFF, category Verbal Fluency Animals total - Phonemic Fluency FAS.

Obtained from ANCOVA with gender as covariate. Post hoc pairwise comparisons were performed with Tukey adjustment.

In measures of verbal fluency, no difference was observed when comparing the SIVD and AD groups with individual measures of fluency in the COWAT (FAS) (SIVD = 10.1 ± 4.6; AD = 10.7 ± 4.7; p = 0.87) or categorical verbal fluency for animals (SIVD = 14.4 ± 6.3; AD = 12.4 ± 6.3; p = 0.42).

When the category and phonemic fluency were considered jointly, with a measure that we called DIFF, there was a trend showing greater impairment in category versus phonemic fluency in AD versus SIVD (AD category minus phonemic fluency = 1.3 ± 6.3; SIVD = 4.3 ± 6.3; p = 0.15).

Prediction of Diagnosis Based on Neuropsychological Profiles

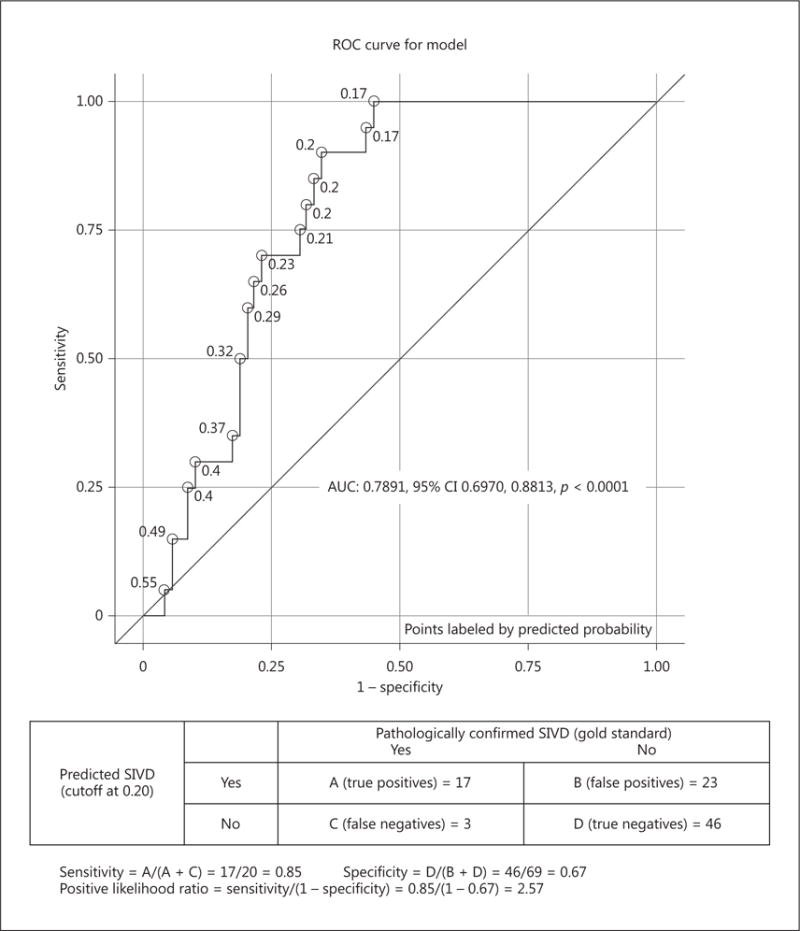

From the neuropsychological tests listed in Table 2, 11 tests with p < 0.20 were entered into forward stepwise logistic regression model to identify independent contributing tests in differentiating SIVD from AD. The first recall from the word-learning test was the most important independent contributing test. It contributed 15.8% variation between SIVD and AD cases (p = 0.004). It was followed by the difference between categorical (animals) versus phonemic fluency (p = 0.13), which explained an additional 3.38% of variation (Table 3). In order to use these results to assess the probability of SIVD in a clinical setting, we added age at neuropsychological testing and years of education in the final model even though both variables were not statistically significant. The ROC curve of predicted probabilities of having SIVD is presented in Figure 1.

Table 3.

Stepwise logistic regression analyses to determine the independent neuropsychological profiles for SIVD

| Step | Factor entered | Adjusted odds ratio | 95% CI | Max-scale R2 |

Cumulative R2 |

p value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | First recall from word learning | 1.50 | 1.14, 1.98 | 15.84% | 15.84% | 0.0039 |

| 2 | Difference between categorical (animals) versus phonemic fluency | 1.06 | 0.98, 1.15 | 3.38% | 19.42% | 0.1263 |

Fig. 1.

Neuropsychological profiles differentiate SIVD (n = 20) from AD (n = 69). An ROC analysis comparing the SIVD and AD groups that included age, education, difference between categorical (animals) vs. phonemic fluency (letter F) and the first recall from the word learning test.

An ROC analysis comparing the SIVD and AD groups that included age, education, difference between categorical (animals) versus phonemic fluency (letter F) and the first recall from the word learning test distinguished the two groups with a sensitivity of 85%, specificity of 67%, and positive likelihood ratio of 2.57 (AUC = 0.79, 95% CI 0.70–0.88; p < 0.0001).

The following equation was created based on the above ROC analysis for predicting SIVD diagnosis versus AD; it is explained in the following two steps:

X (probability of SIVD) = −3.1 + 0.4 × (List Learning Trial 1) + 0.06 × (Verbal Fluency Animals total - Verbal Fluency Letter F total) − 0.02 × (age − 78.4) − 0.01 × (years of education − 14.8)

The predicted probability of SIVD = ex/(1 + ex)

For example, patient A was 80 years old, had 20 years of education, List learning Trial 1 = 6, Verbal Fluency Animals total = 23, Verbal Fluency Letter F total = 9. Using the equation above, we yielded a predicted probability of SIVD = 0.51 for patient A. The cutoff predicted probability of SIVD was equal to 0.20 per the ROC curve; therefore, patient A would be classified as AD per the clinical information we had.

We repeated the ROC analyses after excluding cases with HS (see online supplement 1; for all online suppl. material, see www.karger.com/doi/10.1159/000477344], a confounding factor for memory impairment. In differentiating 16 SIVD from 50 AD cases (without HS), the composite memory/fluency metric showed a sensitivity of 81%, specificity of 72%, and positive likelihood ratio of 2.89 (AUC = 0.80, 95% CI 0.70–0.91; p < 0.0001).

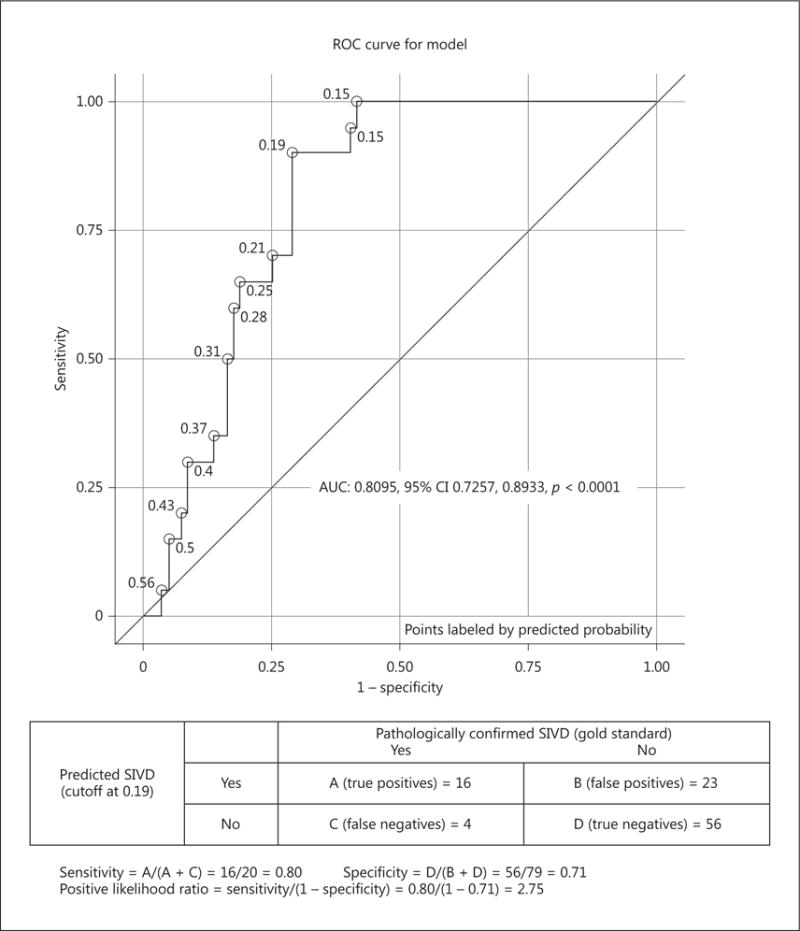

When AD and SIVD are combined (so-called mixed dementia), the impact of AD dominates the behavioral presentation. We repeated the ROC analyses comparing the SIVD group with AD + MIXED (Fig. 2). In differentiating 20 SIVD from 79 AD + MIXED cases, the composite memory/fluency metric showed a sensitivity of 80%, specificity of 71%, and positive likelihood ratio of 2.75 (AUC = 0.80, 95% CI 0.72–0.89; p < 0.0001).

Fig. 2.

Neuropsychological profiles differentiate SIVD (n = 20) from AD + MIXED (n = 79). In differentiating SIVD from AD + MIXED cases, the composite memory/fluency metric showed a sensitivity of 80%, specificity of 71%, and positive likelihood ratio of 0.80.

Discussion

Our study confirms that features of neuropsychological profiles may assist in the clinical differentiation of neuropathologically defined SIVD from AD. A combined memory and verbal fluency score was able to differentiate the two groups with a sensitivity of 85%, specificity of 67%, and positive likelihood ratio of 2.5 (AUC = 0.79, 95% CI 0.70–0.88; p < 0.0001). The cognitive profiles associated with mixed SIVD + AD resemble AD. The sensitivity, specificity, and positive likelihood ratio remained similar after adding the mixed dementia group to the AD group.

This compares favorably with studies based on the clinical diagnostic criteria of VaD, which have reported moderate sensitivity (50–56%) and variable specificity (64–98%) [5]. These metrics could be improved when cases with HS were excluded. However, there are currently no clinical criteria for HS, and diagnosis relies exclusively on neuropathological criteria; therefore, exclusion of HS in a clinical setting is not feasible at this time [13].

Pathological overlap between VCI and neurodegenerative disorders (such as AD and dementia with Lewy bodies) is frequent, especially with increasing age. Converging evidence indicates that ischemic infarcts and neurodegenerative lesions combine in an additive fashion to increase the risk of cognitive impairment and dementia [9].

To be more inclusive of the cases in our entire pathological confirmed cohort, we reclassified the category “other” into AD or SIVD by lowering the scores for pathological diagnosis. We redefined the AD group as B&B ≥3 and CVDPS score <15, SIVD group as B&B <3 and CVDPS score ≥15; when B&B was ≥3 and CVDPS score ≥15, the cases were defined as mixed. With these scores, the SIVD group increased by 2 subjects and the AD group increased by 8 subjects. An ROC analysis with this larger sample showed a sensitivity of 68%, specificity of 68%, and positive likelihood ratio of 2.13 (see online Supplement 2) (AUC = 0.7650, 95% CI 0.66–0.87; p < 0.0001).

A previous report from our group demonstrated that memory loss exceeded executive dysfunction in patients with AD. The reverse was not uniformly the case in SIVD, where variable cognitive profiles of patients with cognitive vascular impairment due to small vessel disease were observed [11]. Our present results confirm and extend these findings with a larger sample and different analytic approach.

Previous studies utilizing neuropsychological assessments to differentiate clinically diagnosed SIVD versus AD have demonstrated greater impairment in executive function and better preservation of recognition memory in SIVD [14–24].

A study performed in patients with probable AD and positive amyloid PET scan versus patients with subcortical VaD based on DMS-IV criteria and negative amyloid PET scan demonstrated that patients with subcortical VaD were better at verbal and visual memory tests including delayed recalls of a Verbal Learning Test and Rey Complex Figure Test, but worse at frontal function tasks (a measure of executive function) including phonemic fluency of the Controlled Oral Word Association Test and Stroop Color Test than patients with AD [25].

Our results based on neuropathologically defined groups confirm that memory is more impaired in patients with AD. In addition, our cohort of patients with SIVD showed a tendency towards greater impairment on phonemic fluency. Our results demonstrate that in measures of verbal fluency, there was a trend showing greater impairment in category versus phonemic fluency in AD versus SIVD, based on the results of the DIFF measure. This is consistent with previous studies that have suggested greater impairments on categorical fluency in patients with AD versus phonemic fluency in patients with SIVD [21, 22].

Similar differences in verbal fluency have been demonstrated between patients with AD versus frontotemporal dementia (FTD), a type of dementia that affects frontal lobe functions including executive function similar to SIVD. AD patients showed greater impairment in semantic category fluency while patients with FTD performed worse on letter fluency, when calculated by a semantic index [26]. It has been proposed that this difference between letter and semantic fluency is suggestive of differences in the relative contribution of frontal lobemediated retrieval deficits in SIVD and FTD and temporal lobe-mediated semantic deficits in AD.

The mechanisms of memory failure are different in SIVD than AD [27]. From a neuroanatomical perspective, the dysexecutive neuropsychological profile seen in SIVD is more characteristic of a dysfunction between frontal-subcortical loops that disrupt the connections between the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex and the basal ganglia, in contrast to the amnestic memory impairment seen in AD explained by the failure of the limbic diencephalic memory system which includes the hippocampus, entorhinal cortex, and Papez circuit, involved in long-term storage. However, it is possible that overlaps among many of the symptom characteristics between AD and SIVD might be explained by common recruitment of extended neocortical networks that adaptively occurs as a compensatory mechanism in the face of a local pathology affecting the medial temporal lobe [28].

Because we did not find statistically significant differences when comparing the two groups with individual measures of fluency in the COWAT (FAS) or categorical verbal fluency for animals, we were unable to predict a diagnosis of AD versus SIVD based on those single measures. In an attempt to predict the probability of AD versus SIVD, we created a formula that incorporates the results of the Learning Trial 1 of the Memory Assessment Scale, number of words generated on phonemic fluency (letter F), number of words generated on categorical fluency for animals, age, and education. This equation yielded moderate sensitivity and specificity to predict a diagnosis of AD versus SIVD. If confirmed by independent studies, this approach could provide an easy way to distinguish AD from SIVD in the clinical setting.

There are several strengths of the present study, including autopsy-confirmed diagnoses, matching of comparison groups on demographic characteristics and dementia severity as measured by the MMSE and global CDR. Limitations include a convenient sample with relatively small sample sizes of the SIVD and mixed pathology groups. We also did not attempt to define neuropsychometric changes in those subjects with a CDR of 0.5 that did not have a significant pathology on autopsy (the “other” category) due to the inability to discern possibly different underlying etiologies.

Conclusion

In neuropathologically defined subgroups, neuropsychological profiles show modest ability to distinguish patients with AD from those with SIVD. These findings are consistent with previous studies based on both clinically and PiB-defined groups. Taken together, the pattern of deficits in AD is consistent with medial and lateral temporal lobe dysfunction (amnestic memory impairment and lower categorical fluency), while the pattern in SIVD showed a tendency towards greater impairment on phonemic fluency and better performance on recognition memory. The ability of the combined memory and verbal fluency measures to differentiate SIVD from AD should be confirmed in an independent sample.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute on Aging (P01AG12435 and P50AG05142).

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

None of the authors have any conflicts of interest to declare.

Author Contributions

All authors have contributed equally to the concept and design, acquisition of subjects and or data, analysis and interpretation of data, and preparation and final approval of the version for publication.

References

- 1.Lopez OL, Kuller LH, Fitzpatrick A, Ives D, Becker JT, Beauchamp N. Evaluation of dementia in the Cardiovascular Health Cognition Study. Neuroepidemiology. 2003;22:1–12. doi: 10.1159/000067110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Levine DA, Langa KM. Vascular cognitive impairment: disease mechanisms and therapeutic implications. Neurotherapeutics. 2011;8:361–373. doi: 10.1007/s13311-011-0047-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Markowitsch HJ, Staniloiu A. Amnesic disorders. Lancet. 2012;380:1429–1440. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)61304-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gorelick PB, Scuteri A, Black SE, Decarli C, Greenberg SM, et al. Vascular contributions to cognitive impairment and dementia: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2011;42:2672–2713. doi: 10.1161/STR.0b013e3182299496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jellinger KA. Pathology and pathogenesis of vascular cognitive impairment - a critical update. Front Aging Neurosci. 2013;5:17. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2013.00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chui HC. Subcortical ischemic vascular dementia. Neurol Clin. 2007;25:717–740. vi. doi: 10.1016/j.ncl.2007.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Suades-Gonzalez E, Jodar-Vicente M, Perdrix-Solas D. Memory deficit in patients with subcortical vascular cognitive impairment versus Alzheimer-type dementia: the sensitivity of the “word list” subtest on the Wechsler Memory Scale-III (in Spanish) Rev Neurol. 2009;49:623–629. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schneider JA, Arvanitakis Z, Bang W, Bennett DA. Mixed brain pathologies account for most dementia cases in community-dwelling older persons. Neurology. 2007;69:2197–2204. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000271090.28148.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chui HC, Ramirez-Gomez L. Clinical and imaging features of mixed Alzheimer and vascular pathologies. Alzheimers Res Ther. 2015;7:21. doi: 10.1186/s13195-015-0104-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chui HC, Zarow C, Mack WJ, Ellis WG, Zheng L, Jagust WJ, Mungas D, Reed BR, Kramer JH, Decarli CC, Weiner MW, Vinters HV. Cognitive impact of subcortical vascular and Alzheimer’s disease pathology. Ann Neurol. 2006;60:677–687. doi: 10.1002/ana.21009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Reed BR, Mungas DM, Kramer JH, Ellis W, Vinters HV, Zarow C, Jagust WJ, Chui HC. Profiles of neuropsychological impairment in autopsy-defined Alzheimer’s disease and cerebrovascular disease. Brain. 2007;130:731–739. doi: 10.1093/brain/awl385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mungas D, Reed BR, Kramer JH. Psychometrically matched measures of global cognition, memory, and executive function for assessment of cognitive decline in older persons. Neuropsychology. 2003;17:380–392. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.17.3.380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nelson PT, Smith CD, Abner EL, Wilfred BJ, Wang WX, Neltner JH, Baker M, Fardo DW, Kryscio RJ, Scheff SW, Jicha GA, Jellinger KA, Van Eldik LJ, Schmitt FA. Hippocampal sclerosis of aging, a prevalent and high-morbidity brain disease. Acta Neuropathol. 2013;126:161–177. doi: 10.1007/s00401-013-1154-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mendez MF, Ashla-Mendez M. Differences between multi-infarct dementia and Alzheimer’s disease on unstructured neuropsychological tasks. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1991;13:923–932. doi: 10.1080/01688639108405108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Almkvist O. Neuropsychological deficits in vascular dementia in relation to Alzheimer’s disease: reviewing evidence for functional similarity or divergence. Dementia. 1994;5:203–209. doi: 10.1159/000106724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kertesz A, Clydesdale S. Neuropsychological deficits in vascular dementia vs Alzheimer’s disease. Frontal lobe deficits prominent in vascular dementia. Arch Neurol. 1994;51:1226–1231. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1994.00540240070018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lafosse JM, Reed BR, Mungas D, Sterling SB, Wahbeh H, Jagust WJ. Fluency and memory differences between ischemic vascular dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 1997;11:514–522. doi: 10.1037//0894-4105.11.4.514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tei H, Miyazaki A, Iwata M, Osawa M, Nagata Y, Maruyama S. Early-stage Alzheimer’s disease and multiple subcortical infarction with mild cognitive impairment: neuropsychological comparison using an easily applicable test battery. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 1997;8:355–358. doi: 10.1159/000106655. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Matsuda O, Saito M, Sugishita M. Cognitive deficits of mild dementia: a comparison between dementia of the Alzheimer’s type and vascular dementia. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1998;52:87–91. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.1998.tb00978.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Looi JC, Sachdev PS. Differentiation of vascular dementia from AD on neuropsychological tests. Neurology. 1999;53:670–678. doi: 10.1212/wnl.53.4.670. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lukatela K, Cohen RA, Kessler H, Jenkins MA, Moser DJ, Stone WF, Gordon N, Kaplan RF. Dementia Rating Scale performance: a comparison of vascular and Alzheimer’s dementia. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 2000;22:445–454. doi: 10.1076/1380-3395(200008)22:4;1-0;FT445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Desmond DW. The neuropsychology of vascular cognitive impairment: is there a specific cognitive deficit? J Neurol Sci. 2004;226:3–7. doi: 10.1016/j.jns.2004.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graham NL, Emery T, Hodges JR. Distinctive cognitive profiles in Alzheimer’s disease and subcortical vascular dementia. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:61–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tarykov Latchezar BS, Thibaudet M-C, Rigaud A-S, Smagghe A, Boller F. Neuropsychological deficit in early subcortical vascular dementia: comparison to Alzheimer’s disease. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2002:26–32. doi: 10.1159/000058330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yoon CW, Shin JS, Kim HJ, Cho H, Noh Y, Kim GH, Chin JH, Oh SJ, Kim JS, Choe YS, Lee KH, Lee JH, Seo SW, Na DL. Cognitive deficits of pure subcortical vascular dementia versus Alzheimer disease: PiB-PET-based study. Neurology. 2013;80:569–573. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182815485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rascovsky K, Salmon DP, Hansen LA, Thal LJ, Galasko D. Disparate letter and semantic category fluency deficits in autopsy-confirmed frontotemporal dementia and Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychology. 2007;21:20–30. doi: 10.1037/0894-4105.21.1.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reed B, Eberling JL, Mungas D, Weiner MW, Jagust WJ. Memory failure has different mechanisms in subcortical stroke and Alzheimer’s disease. Ann Neurol. 2000;48:275–284. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Finke C, Bruehl H, Duzel E, Heekeren HR, Ploner CJ. Neural correlates of short-term memory reorganization in humans with hippocampal damage. J Neurosci. 2013;33:11061–11069. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0744-13.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]