Abstract

Patient: Male, 30

Final Diagnosis: Benign pericardial schwannoma

Symptoms: Chest pain

Medication: —

Clinical Procedure: —

Specialty: Surgery

Objective:

Rare disease

Background:

Primary pericardial tumors have a prevalence of between 6.7% and 12.8% of all tumors arising in the cardiac region. Pericardial schwannoma is a rare entity. It arises from the cardiac plexus and vagus nerve innervating the heart. Most of the reported cases, have presented with benign behavior, however, in rare situations, they can undergo transformation to malignant behavior When comparing the prevalence of cardiac tumors to that of pericardial tumors, the latter is much lower in occurrence. A review of English literature identified six pericardial schwannoma cases.

Case Report:

We present a case of a 30-year-old male patient who presented to our center with the chief complaint of six months of gradually progressive left chest pain. His past medical history (PMH) was positive for panic attacks (for which he was taking beta-blockers), paroxysmal tachycardia, sweating, and irritability. A computed tomography chest scan was done; a differential diagnosis of paraganglioma was suggested. However, histopathological examination confirmed the pericardial mass was a schwannoma. The patient was surgically treated by thoracotomy to resect the lesion.

Conclusions:

This case adds to the existing limited literature on pericardial schwannoma as the seventh reported case. Neurogenic cardiac tumors; our case marks the second case reported to occur in the subcarinal area near the left atrium.

MeSH Keywords: Neurilemmoma, Pericardium, Thoracotomy

Background

Primary cardiac tumors are exceedingly rare tumors with a prevalence of 0.02–0.056% [1]. When comparing the prevalence of cardiac tumors to that of pericardial tumors, the latter has an even lower occurrence. Primary pericardial tumors have a prevalence of between 6.7% and 12.8% of all tumors arising in cardiac region [2]. Schwannoma are slow growing tumors arising from Schwann cells that produce myelin to sheath peripheral nerves. They are commonly encountered in the neck and head but can be present anywhere in the mediastinum, most commonly in the posterior mediastinum and only rarely in the middle mediastinum [3]. Pericardial schwannoma may develop on very rare occasions and are thought to arise from the cardiac branches originating from the vagus nerve or the cardiac plexus [4]. Recognition of such tumors is critical as they have the potential, though minimal, to transform, displaying malignant behavior. Their growth tends to produce clinical signs and symptoms related to tumor size and compression of adjacent structures such as the great vessels, heart chambers, mediastinal structures, and coronary arteries [2]. In this report, we present a case of a pericardial schwannoma detected in a previously healthy thirty-year-old-male patient that was initially misdiagnosed as a paraganglioma. We also reviewed and summarized similar previous reported cases.

Case Report

In our case, a 30-year-old male patient presented to King Faisal Specialist Hospital with a chief complaint of six months of gradually progressive left chest and left upper quadrant pain radiating to the shoulder and scapula. His past medical history (PMH) was positive for panic attacks for which he was taking beta-blockers, paroxysmal tachycardia, sweating, and irritability. His PMH was negative for major illnesses, hypertension, diabetes, and bronchial asthma. The patient’s review of systems was negative for weight loss, fever, skeletal and neurological symptoms. On physical examination, he was well nourished, and his abdomen was soft, non-tender, and non-distended. No clubbing, lymphadenopathy, pedal edema, icterus, or pallor were noted, and his jugular venous pressure was considered within normal limits. Respiratory system examination, neurological examination, renal panel, urine examination, hepatic profile, and coagulation profile were within normal limits and the patient had no apparent systemic changes. The patient’s vitals were stable, and his complete blood count, basic metabolic panel, and coagulation profile were within normal limits. His upper endoscopy revealed mild gastritis and his chest x-ray was within normal limits.

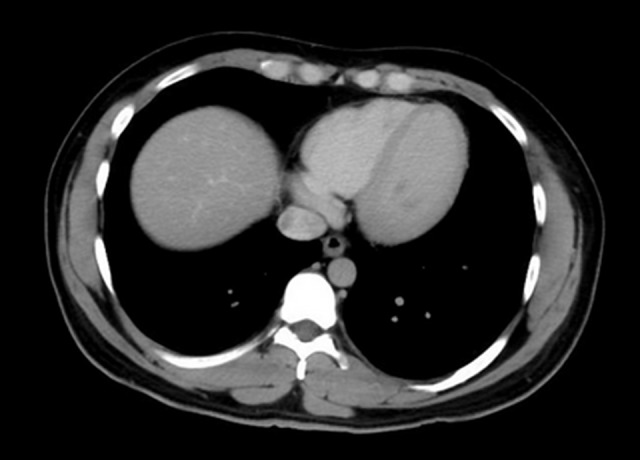

Computed tomography (CT) chest scan revealed a 3×2 cm enhancing, subcarinal mass that was documented as an intrapericardial mass lesion adjacent to the left atrium (Figure 1). No other lesions were noted in the chest or upper abdomen.. The pre-operative diagnosis documented was “retrocardiac mass” and the patient was admitted for further investigation. The electrocardiogram report showed a normal sinus rhythm with possible left atrial enlargement. Electrocardiography (Echo) imaging showed a small rounded mass superior to the atria. Other Echo parameters were within normal range. Cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed a 2.5×2.5 cm intensely enhanced mass located just anterior to the esophagus that was causing indentation on the right pulmonary artery. A positron emission tomography (PET)/CT revealed mild flurodeoxyglucose (FDG-avid) solitary lesion of most likely benign etiology but at the time, malignancy could not be ruled out of the differential diagnosis (Figure 2). The patient was referred to thoracic surgery for a thoracotomy and excision of the intrapericardial soft tissue lesion. Schwannoma and paraganglioma were among the differential diagnoses for this patient’s presentation. The results of these investigations ruled out other abnormalities such as critical aortic stenosis, acute coronary syndrome, and hypertrophic cardiomyopathy.

Figure 1.

Computed tomography chest scan revealed a 3×2 cm enhancing, subcarinal mass that was documented as an intrapericardial mass lesion adjacent to the left atrium.

Figure 2.

Positron emission tomography shows mild flurodeoxyglucose (FDG-avid) uptake.

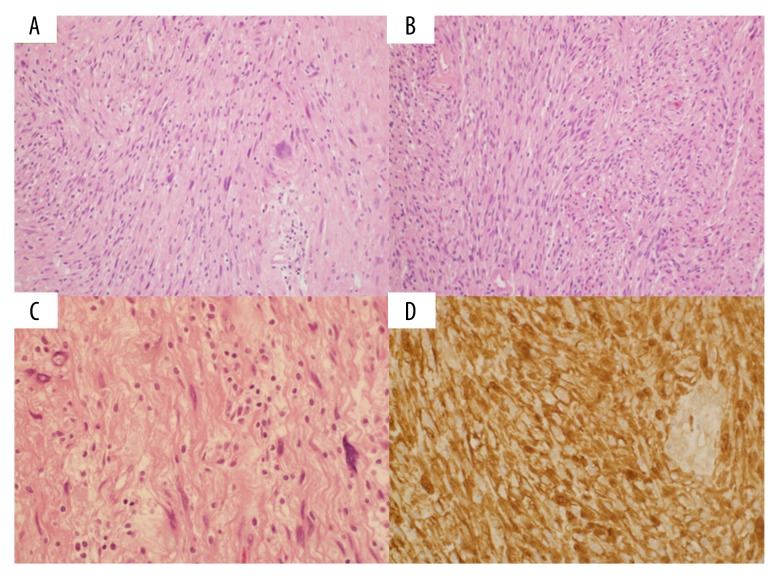

Upon total excision, the mass was discovered to be a 2×2 cm avascular, firm mass. The surgery was uncomplicated, with an estimated 100 cc of blood loss. The specimen was sent for histopathology and the patient was discharged with analgesics and a six-week follow-up appointment with s scheduled for chest x-ray at the outpatient clinic. The ultimate diagnosis, pericardial schwannoma, was made based on the findings of microscopic examination which shows cellular areas consisting of monomorphic spindle-shaped Schwann cells with poorly defined eosinophilic cytoplasm and pointed basophilic nuclei set in a collagenous stroma (Figure 3A, 3B). Areas characteristic of Antoni B, composed of Schwann cells with inconspicuous cytoplasm and nuclei suspended in myxoid matrix, are identified (Figure 3C). Immunohistochemical studies revealed that the tumor cells stained positive for S100 (Figure 3D).

Figure 3.

Monomorphic Schwann cells with focal nuclear palisading (A, B). Schwann cells with inconspicuous cytoplasm and nuclei suspended in myxoid matrix (C). Immunohistochemical stain is positive for S-100 protein (D).

Discussion

Primary cardiac neoplasms are exceedingly rare tumors with a prevalence of between 0.02% and 0.056% [1]. Occurrence of schwannoma in the pericardium is even rarer [2]. Our review of the English language literature revealed a total number of 24 cases reported: cardiac schwannoma (n=18) and pericardial schwannoma (n=6). Our case offers a significant addition to the literature of pericardial schwannoma, as it marks the seventh case reported in English language literature and the second case reported that was located in the subcarinal area near the left atrium.

The majority of the pericardial schwannoma cases, including our case, were benign (n=6), however, one case presented with malignant behavior. Three cases, including ours, demonstrated a nonspecific presentation of cough and chest pain, which are common symptoms in many disease processes. Two cases were discovered as incidental findings due to heart enlargement on chest radiograph. Interestingly, two advanced cases presented as acute coronary syndrome and heart failure (Table 1) [5–10].

Table 1.

Previous cases reported in literature: presentation, tumor characteristics and treatment modality.

| Number of Patients | Age (years) | Sex (M/F) | Presenting symptoms | Behavior | Tumor size (cm) | Complication | Surgical/management approach | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 35 | M | Intermittent chest pain | Benign | 2.5×2.5×2 | None | Median sternotomy, no CPB | [5] |

| 2 | 38 | F | Atypical angina | Benign | – | Acute coronary syndrome | – | [6] |

| 3 | 50 | F | Productive cough | Benign | 9×11 | None | Thoracotomy | [7] |

| 4 | 60 | M | Dyspnea, orthopnea, chest pain and paradoxical pulse | Malignant | 5.2×7×11 | ICU stay, orthopnea and hypoperfusion | Partial resection + adjuvant radiation and chemotherapy | [8] |

| 5 | 42 | F | Incidental cardiomegaly on chest radiograph | Benign | 14×10×7 | None | Sternotomy + CPB + 3D printing model | [9] |

| 6 | 46 | F | Cardiomegaly on chest radiograph | Benign | 12×8×7 | None | Median sternotomy + CPB | [10] |

| Present case | 30 | M | Left chest pain | Benign | 2×2 | None | Right thoracotomy excision |

ICU – intensive care unit; CPB – cardiopulmonary bypass.

Generally, primary tumors of the pericardium exhibit a non-specific or asymptomatic presentation due to the various sizes, locations, and relationship of the tumor to the adjacent structures in the mediastinum. In our case, the preoperative differential diagnosis was thought to be a paraganglioma, due to the lesion’s location in the left atrium, a common location for paragangliomas, and the presenting associated symptoms of panic attacks, tachycardia, and sweating, which commonly result with paragangliomas from plasma elevation of catecholamines [1,2]. However, schwannoma of the heart was the first differential diagnosis in this patient’s presentation.

The role of imaging in the diagnosis of pericardial lesions is crucial, however, the ultimate diagnosis can be only confirmed by lesion biopsy. Initially, the patient’s chest radiograph revealed no significant findings. However, CT demonstrated an enhanced mass in the subcarinal area near the left atrium. CT plays an important role in the evaluation of pericardial masses as it assists in narrowing the differential diagnosis and illuminating the relationship of the tumor to adjacent structures, and the tumor’s invasion into significant vascular structures in the mediastinum. Also, CT along with PET scan help in staging the tumor and examining for metastasis locally or at distant sites [1,2].

Peripheral nerve sheath tumors exhibit variable and not well correlated clinical-pathobiological features, and schwannoma offers a good example of such a spectrum. Schwannoma can be classified as 1) conventional schwannoma, 2) cellular schwannoma, 3) plexiform schwannoma, and 4) melanotic schwannoma [11]. Typically, schwannoma express variable amounts of organized hypercellular region (Antoni A) and less organized hypocellular area with myoxid matrix (Antoni B). In our case, the histopathology examination showed the presence of a cellular area organized into palisading Antoni A (Figure 3A) and Antoni B (Figure 3C). Immunohistochemical staining revealed the expression of S-100 protein suggesting neuronal origin (Figure 3D) [12]. The origin of schwannoma is attributed to the peripheral nerves that arise from the cardiac plexus and cardiac branches arising from the vagus nerve. Location wise, cardiac schwannoma can appear in right and left atrium with equal distribution [13]. However, it can on rare occasions appear anywhere in the heart, including the pericardium which is innervated by the autonomic nervous system [4].

Surgical resection remains the mainstay strategy in the treatment of cardiac schwannoma, and early recognition and excision is crucial for better prognosis and prevention of complications. In reviewing previous cases, thoracotomy and sternotomy were the mainstays of treatment. In addition, cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) was used in three separate cases to stabilize the patients’ hemodynamics, while in two cases, including our case, CPB was not utilized due to the small size of the lesion [5–10].

Conclusions

Pericardial schwannoma is a rare entity that has been previously reported in English language literature six times. Our case is significant as it marks the seventh case and the second in the subcarinal area. The majority of reported pericardial schwannoma cases were benign with an equal ratio of male to female cases, and nonspecific symptoms on presentation. Recognition of pericardial schwannoma and early surgical intervention plays an important role in the prevention of complications.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest

None.

References:

- 1.Restrepo CS, Vargas D, Ocazionez D, et al. Primary pericardial tumors. Radiographics. 2013;33:1613–30. doi: 10.1148/rg.336135512. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Grebenc ML, Rosado de Christenson ML, Burke AP, et al. Primary cardiac and pericardial neoplasms: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics. 2000;20:1073–103. doi: 10.1148/radiographics.20.4.g00jl081073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang W, Cui M, Ma HX, et al. A large schwannoma of the middle mediastinum: A case report and review of the literature. Oncol Lett. 2016;11:1719–21. doi: 10.3892/ol.2016.4148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hwang SK, Jung SH. Schwannoma of the heart. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;47:141–44. doi: 10.5090/kjtcs.2014.47.2.141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chung JH, Jung JS, Lee SH, et al. Resection of intrapericardial schwannoma co-existing with thymic follicular hyperplasia through sternotomy without cardiopulmonary bypass. Korean J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2014;47:298–301. doi: 10.5090/kjtcs.2014.47.3.298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajesh GN, Raju D, Haridasan V, et al. Intrapericardial schwannoma presenting as acute coronary syndrome. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(25):e527. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.06.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang XH, Wang Y, Quan XY, Liang B. Benign pericardial schwannoma in a Chinese woman: A case report. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2013;13:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2261-13-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.D’Amato N, Correale M, Ireva R, Di Biase M. A rare cause of acute heart failure: malignant schwannoma of the pericardium. Congest Heart Fail. 2010;16(2):82–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-7133.2009.00124.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Son KH, Kim KW, Ahn CB, et al. Surgical planning by 3D printing for primary cardiac schwannoma resection. Yonsei Med J. 2015;56(6):1735–37. doi: 10.3349/ymj.2015.56.6.1735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hashimoto T, Eguchi S, Nakayama T, et al. Successful removal of massive cardiac neurilemoma with cardiopulmonary bypass. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66(2):553–55. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(98)00473-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kurtkaya-Yapicier O, Scheithauer BW, Woodruff JM. The pathobiologic spectrum of schwannomas. Histol Histopathol. 2003;18(3):925–34. doi: 10.14670/HH-18.925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rodriguez FJ, Folpe AL, Giannini C, Perry A. Pathology of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: Diagnostic overview and update on selected diagnostic problems. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(3):295–319. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0954-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yun PJ, Huang TW, Li YF, et al. Symptomatic pericardial schwannoma treated with video-assisted thoracic surgery: A case report. J Thorac Dis. 2016;8(5):E349–52. doi: 10.21037/jtd.2016.03.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]