Abstract

Plant breeding programs in local regions may have genetic and phenotypic variations that are desirable and shape adaptability during the establishment of local populations. Despite the characterization of genetic population structures in various kinds of populations, the effects of variations in phenotype on agro-economical traits currently remain unclear. In the present study, we evaluated phenotypic changes in 26 agro-economical traits among the local population during rice breeding programs in Hokkaido. Wide variations were observed in all 26 agro-economical traits with continuous distributions. In order to elucidate improvements in these agro-economic traits during rice breeding programs in Hokkaido, values were compared between genetic population structures. Traits were classified into four patterns based on the timing of significant differences. Patterns A and B showed significant differences once and twice, respectively. Pattern C gradually showed significant differences. Pattern D showed no significant differences for the desired directions. Based on the changes in phenotype observed in the present study and the genetic population structure for the local population in Hokkaido, a model of the artificial selection for phenotypes in genetic diversity among the local population during plant breeding programs has been proposed.

Keywords: local population, Oryza sativa L., plant breeding programs, rice, selection

Introduction

Asian cultivated rice (Oryza sativa L.) is one of the important crops in the world. Cultivated rice originated from tropical regions and expanded to a wide range of geographic areas with diverse environmental conditions due to extensive efforts by rice breeding programs worldwide (Vaughan et al. 2008a, 2008b). Geographically, indica is preferred in tropical and subtropical regions, whereas japonica is used in wider regions including more temperate regions than those of indica (Agrama et al. 2010, Vaughan et al. 2008a). Genetic variations in various kinds of populations have been evaluated worldwide, country, and regional levels using molecular markers (Ebana et al. 2008, Fujino et al. 2015a, Kojima et al. 2005, Shinada et al. 2014, Yamamoto et al. 2010). Varietal differences as DNA variations are an important genetic resources for a primary gene pool of local populations because they may be involved in local adaptation to specific environmental conditions at the edge of the species range. Therefore, phenotypic changes during the process of establishing a local population has been unclear.

Hokkaido is the northernmost region of Japan and one of the northern limits of rice cultivation. The climatic conditions in Hokkaido are unique for rice cultivation, namely, a cool temperature during rice growth period with a naturally long daylength of more than 15 hours. Only varieties with extremely early heading behavior are grown in Hokkaido. Rice cultivation began in Hokkaido in the late 1800s. In order to overcome the unique climatic conditions, intensive selections with a focus on extremely early heading, tolerance to low temperature, yield, and eating quality have been conducted (Ando et al. 2010, Fujino et al. 2013, 2015b, Fujino and Sekiguchi 2005a, 2005b, Shinada et al. 2013, Takemoto-Kuno et al. 2015). As a result of 100-year rice breeding programs in Hokkaido, rice is now the principal crop in Hokkaido which occupies 7.55% of total rice production in Japan in 2015 (http://www.pref.hokkaido.lg.jp/ns/nsk/kome/).

We previously identified the genetic population structure of the local rice population established by rice breeding programs in Hokkaido (Shinada et al. 2014). This local population had been divided into six groups according to the objectives of the rice breeding programs in each generation. Group I consisted of landraces and their pedigrees established before 1941. Group II was the pedigree of group I established between 1919 and 1953. Group IIIa was established between 1935 and 1977, Group IIIb between 1962 and 1989, Group IV between 1940 and 1990, and Group V after 1983. Furthermore, the genetic base of the local population has markedly shifted to the current variety type in the last two decades (Fujino et al. 2015a). The rapid accumulation of pre-existing mutations may play major roles in establishing and shaping adaptability to local regions in current rice breeding programs.

The precise evaluation of phenotypes under the conditions in which varieties will be grown is essential for plant breeding programs. For human demands, plant varieties have been improved resulting in plant-type, yield, quality, and tolerance to biotic and abiotic stress under diverse conditions that differ from their origins. Despite the characterization of genetic population structures in various kinds of populations (Ali et al. 2011, Courtois et al. 2012, Ebana et al. 2008, Yan et al. 2007), the effects of variations in phenotypes on agro-economical traits currently remain unclear. In the present study, we demonstrated phenotypic changes among the local population during rice breeding programs in Hokkaido. The results obtained revealed a role of the artificial selection for phenotypes in genetic diversity in local populations during plant breeding programs.

Materials and Methods

Plant material

The Hokkaido Rice Core Panel (HRCP), which includes 63 landraces and varieties bred by breeding programs (Shinada et al. 2014), was used. The HRCP represents the genetic diversity of this local population and was clearly classified into six groups over the history of rice breeding programs in Hokkaido.

All rice varieties were cultivated in experimental paddy fields at Kamikawa Agricultural Experiment Station, Pippu, Japan, 43°51′ N latitude. Sowing and transplanting were performed in late April and late May, respectively. All materials were planted with a 15.0-cm spacing between plants within each row and 30.0-cm spacing between rows. Cultivation management followed the standard procedures used at Kamikawa Agricultural Experiment Station. Seeds were harvested at the full maturity stage.

Phenotype evaluation

Twenty-six agronomic traits which were used to be measured in practical rice breeding programs were evaluated. We evaluated the values of varieties in 2013 and 2014 because agro-economical traits are influenced by environmental conditions such as temperature during growth periods. The descriptions, abbreviations, and units of the 26 traits were listed in Table 1. In evaluations of grain quality, seeds were subjected to the following procedures. Brown rice was polished to 90% of the original grain weight using a Pearlest (Kett electric laboratory, Tokyo) and then milled using a Laboratory Mill Quadrumat Junior II (Brabender, Germany).

Table 1.

List of traits measured in this study

| Trait | Unit | Abbreviation | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plant height | cm | PH | Height of plants after 1 month from transplanting, means of 4 or 8 plants |

| Tiller number | Number | TN | Number of tillers after 1 month from transplanting, means of 4 or 8 plants |

| Days to heading | Days | DTH | Days to heading from sowing more than 90% plants exhibit the emergence of panicle |

| Days to maturing | Days | DTM | Days to maturing from DTH more than 90% plants exhibit ripning colour of panicle |

| Culm length | cm | CL | Culm length in the longest tillers in eight or 10 plants |

| Panicle length | cm | PL | Means of panicle length in the longest tillers in eight or 10 plants |

| Panicle number | Number/m2 | PN | Means of panicle number in eight or 10 plants |

| 1000-grains weight | g | TGW | Weight of 1000 grains calcurated from 500 grains |

| Seeds per panicle | Number | SP | Number of seeds on panicle |

| Seeds per area | Number/m2 | SA | Number of seeds per 1 m2 |

| Seed sterility | % | SS | Ratio of sterile seeds on five or three panicles per plants |

| Plant weight | kg/a | PW | Means of total plant weight in 12 or 20 plants |

| Seed weight | kg/a | SW | Means of total seed weight in 12 or 20 plants |

| Total yield | kg/a | YLDt | Means of unhulled seed weight in 12 or 20 plants |

| Standard yield | kg/a | YLDs | Means of unhulled seed weight in 12 or 20 plants, seeds with more than 1.9 mm grain thick were selected |

| Hulling rate | % | HR | Ratio of SW in YLDt |

| Grain apperance | % | GA | Measured by RGQI10B (SATAKE) |

| Immature seeds | % | IMS | Measured by RGQI10B (SATAKE) |

| Grain length | mm | GL | Measured by RGQI10B (SATAKE) |

| Grain wideth | mm | GW | Measured by RGQI10B (SATAKE) |

| Grain thickness | mm | GT | Measured by RGQI10B (SATAKE) |

| Whiteness of brown rice | Number | WB | Measured by C-300 (Kett) |

| Whiteness of white rice | Number | WW | Measured by C-300 (Kett) |

| Protein content | % | PC | Measuered by Infratec1241 (FOSS) |

| Hull-cracked rice | % | HC | Ratio of hull-crackled rice among 300 grains |

| Amylose content | % | AC | Measured by AutoAnalyzer (BRAN LUEBBE) |

In order to elucidate phenotypic changes, varieties were classified into six groups by the genetic population structure based on genome-wide DNA polymorphisms (Shinada et al. 2014), and values were then compared between groups. The Tukey-Kramer HSD test was conducted using JMP (SAS Institute, USA).

Results

Variations in traits

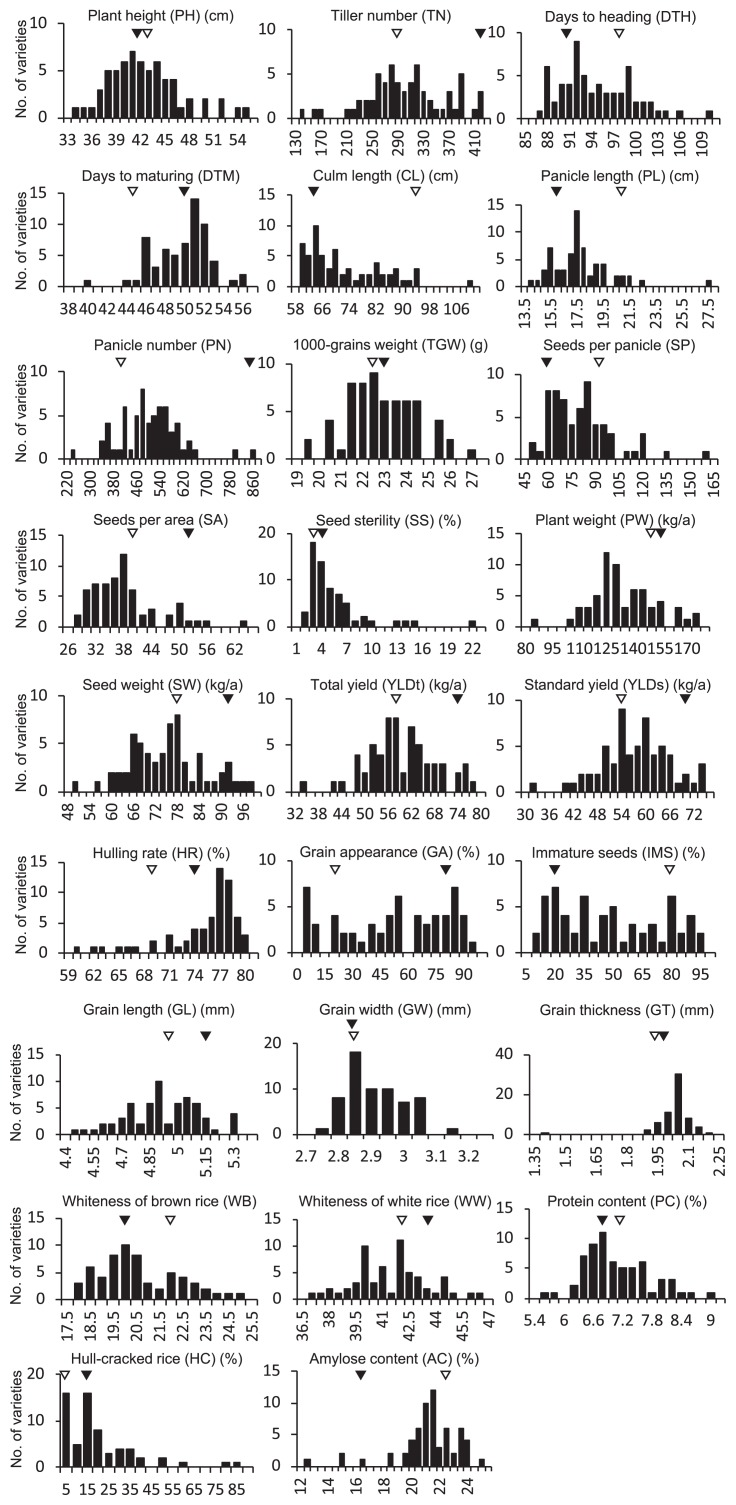

Wide variations were observed in all 26 agro-economical traits (Supplemental Tables 1, 2). The frequency distributions of the varieties evaluated in 2013 were shown in Fig. 1. Continuous distributions with extreme large or small values were observed. Regarding plant type, the latest DTH and earliest DTM were observed in Ounochutou, 109, and Tomoemasari, 39, respectively. Ounochutou exhibited the highest SA, 62.1. The longest CL and highest SP were observed in Minakuchiine, 109.0 and 159.9, respectively. Hokkaiwase showed the longest PL, but smallest PN, 27.5 and 237, respectively. Higher PN was observed in Hoshimaru, 796, and Yumepirika, 848. Norin No. 11 showed the highest SS, 21.6. Norin No. 15 exhibited the lowest values of PW (83.3), SW (49.3), YLDt (32.9), and YLDs (31.2), while Tomoenishiki exhibited the highest values of PW (174.1) and SW (96.8) and Yukara had the highest values of YLDt (76.1) and YLDs (73.7). Regarding grain shape, the largest values of GW and TGW were observed in Mimasari, 3.13, and Daichinohoshi, 26.9, respectively. High HC, more than 70%, was observed in Ishikarishiroge, 75.0, and Ounochutou, 84.5. Concerning grain quality, high and low PC were observed in Wasebouzu, 8.89, Tomoemasari, 6.98, and Ounochutou, 5.69, respectively. High AC, 24.5, was detected in Bouzu No. 6, while low AC was detected in Eiko, 18.3, and Honoka 224, 18.4, except for four accessions with the dull mutations.

Fig. 1.

Frequency distributions of 26 traits among the HRCP evaluated in 2013. Open and closed triangles indicate the values of Akage and Yumepirika, respectively.

The current leading variety Yumepirika exhibited the preferred phenotype over landrace Akage; high TN, early DTH, short CL, short PL, high PN, few SP, high SA, high SW, high YLDt, high YLDs, high GA, low IMS, high WW, low PC, and low AC (Fig. 1).

Similar phenotypic variations and frequency distributions were observed in both years, 2013 and 2014 (Supplemental Tables 1, 2).

Correlations among 26 traits

Correlations were observed between many pairs of the 26 agro-economical traits (Supplemental Table 3). Strong correlations with absolute values of more than 0.7 were observed in 16 trait combinations. Among them, 13 and three showed positive and negative correlations, respectively. PW showed positive correlations with DTH, SA, SW, YLDt, and YLDs, but a negative correlation with PC. The highest positive and negative correlations were observed at the trait combinations of YLDt-SW, 0.984 in 2014, and IMS-GA, −0.990 in 2013, respectively.

Phenotypic changes during rice breeding programs

In order to elucidate improvements in agro-economic traits during the rice breeding programs in Hokkaido, values were compared between genetic population structures (Table 2). Based on the timing of the generation of significant differences, traits were classified into four patterns: A, B, C, and D. In nine traits, a significant difference was detected once; Pattern A, PH, PL, PW, SW, YLDt, YLDs, HR, and PC detected between Groups I and II, whereas AC was observed between Groups III and V. Pattern B showed significant differences twice; CL, PN, GA, IMS, and WB. Pattern C gradually showed significant differences; TN, TGW, SP, GT, and HC. Pattern D showed no significant differences for the desired directions; DTH, DTM, SA, SS, GL, GW, and WW.

Table 2.

Changes of the 26 traits during rice breeding programs

| Trait | All | Groupa | Pattern | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| I | II | IIIa | IIIb | IV | V | |||

|

| ||||||||

| n = 63 | n = 11 | n = 8 | n = 13 | n = 6 | n = 11 | n = 13 | ||

| Plant height (PH) | 42.0 ± 4.4 | 47.3 ± 4.8b | 40.7 ± 4.0a | 42.2 ± 4.7a | 40.0 ± 0.9a | 41.4 ± 2.9a | 39.9 ± 2.0a | A |

| 44.0 ± 4.3 | 48.6 ± 4.1b | 42.3 ± 4.7a | 42.9 ± 3.8a | 42.9 ± 2.6a | 44.2 ± 3.2ab | 42.9 ± 3.7a | ||

| Tiller number (TN) | 297.9 ± 62.8 | 254.0 ± 71.2 | 310.4 ± 61.4 | 304.3 ± 58.0 | 341.7 ± 53.1 | 282.3 ± 58.0 | 315.8 ± 55.7 | C |

| 289.8 ± 60.3 | 231.3 ± 53.7a | 293.8 ± 63.4ab | 292.1 ± 60.8ab | 297.2 ± 28.9ab | 275.5 ± 44.7ab | 333.1 ± 38.5b | ||

| Days to heading (DTH) | 93.7 ± 5.0 | 92.7 ± 4.8ab | 98.1 ± 4.8b | 95.7 ± 5.5b | 96.2 ± 4.0ab | 91.5 ± 4.2a | 90.4 ± 2.2a | D |

| 83.3 ± 6.3 | 80.5 ± 6.2a | 88.9 ± 9.2b | 85.0 ± 6.2ab | 84.7 ± 6.0ab | 80.1 ± 4.9a | 82.3 ± 2.8ab | ||

| Days to maturing (DTM) | 48.7 ± 2.9 | 48.4 ± 2.8 | 46.8 ± 3.9 | 48.1 ± 2.2 | 48.0 ± 2.5 | 50.1 ± 3.2 | 50.3 ± 2.0 | D |

| 58.8 ± 6.8 | 55.8 ± 4.9 | 58.9 ± 5.2 | 56.5 ± 6.9 | 55.8 ± 5.3 | 62.6 ± 9.4 | 61.4 ± 5.5 | ||

| Culm length (CL) | 71.8 ± 11.4 | 86.3 ± 11.4c | 81.2 ± 4.0bc | 74.3 ± 9.0b | 63.9 ± 2.6a | 64.7 ± 3.6a | 61.6 ± 2.5a | B |

| 69.6 ± 9.8 | 79.9 ± 12.7c | 78.4 ± 5.1bc | 70.2 ± 7.0ab | 61.7 ± 5.6a | 62.6 ± 2.3a | 64.7 ± 5.1a | ||

| Panicle length (PL) | 17.5 ± 2.2 | 20.6 ± 2.7b | 16.6 ± 2.4a | 16.3 ± 1.1a | 17.8 ± 0.9a | 17.2 ± 1.1a | 16.7 ± 1.2a | A |

| 16.8 ± 1.8 | 19.1 ± 2.1c | 16.9 ± 0.8ab | 16.4 ± 1.5a | 17.0 ± 1.5bc | 16.1 ± 1.0a | 15.9 ± 1.4a | ||

| Panicle number (PN) | 494.0 ± 103.7 | 407.1 ± 110.6a | 469.9 ± 93.6ab | 478.1 ± 72.5ab | 511.1 ± 43.9ab | 501.5 ± 76.5ab | 576.1 ± 115.4b | B |

| 551.6 ± 103.3 | 425.5 ± 89.9a | 546.7 ± 108.6b | 530.4 ± 76.5b | 591.9 ± 46.7bc | 553.7 ± 65.5b | 652.6 ± 54.5c | ||

| 1000-grains weight (TGW) | 22.7 ± 1.6 | 21.3 ± 1.3a | 22.2 ± 0.9ab | 22.6 ± 1.9ab | 23.0 ± 1.1ab | 22.8 ± 1.4ab | 23.7 ± 1.5b | C |

| 22.8 ± 1.5 | 21.9 ± 1.6a | 22.6 ± 0.9ab | 22.6 ± 1.6ab | 23.0 ± 1.4ab | 22.8 ± 1.2ab | 23.8 ± 1.5b | ||

| Seeds per panicle (SP) | 78.6 ± 20.9 | 102.4 ± 27.6c | 87.6 ± 13.8bc | 83.0 ± 16.0b | 69.6 ± 8.1a | 72.5 ± 10.5ab | 59.0 ± 6.0a | C |

| 88.6 ± 18.5 | 101.7 ± 28.3b | 92.7 ± 11.6ab | 92.8 ± 15.3ab | 90.0 ± 23.3ab | 81.6 ± 10.0ab | 76.5 ± 9.2a | ||

| Seeds per area (SA) | 37.4 ± 7.3 | 40.1 ± 9.7 | 40.4 ± 5.7 | 39.4 ± 8.8 | 35.6 ± 5.0 | 35.9 ± 4.1 | 33.7 ± 6.1 | D |

| 48.2 ± 10.6 | 42.3 ± 11.0 | 51.0 ± 13.7 | 49.3 ± 10.6 | 53.0 ± 12.6 | 45.1 ± 7.3 | 50.1 ± 8.7 | ||

| Seed sterility (SS) | 4.8 ± 3.5 | 6.8 ± 5.7 | 3.9 ± 2.3 | 4.2 ± 1.6 | 3.9 ± 2.5 | 6.1 ± 4.3 | 3.4 ± 1.5 | D |

| 5.7 ± 3.6 | 6.8 ± 4.6 | 8.8 ± 4.7 | 4.5 ± 1.5 | 4.4 ± 1.5 | 5.2 ± 4.1 | 4.7 ± 2.8 | ||

| Plant weight (PW) | 131.8 ± 17.5 | 128.1 ± 19.6ab | 145.4 ± 17.1b | 136.6 ± 17.0ab | 136.1 ± 20.2ab | 121.8 ± 15.9a | 128.6 ± 12.2ab | A |

| 134.8 ± 20.1 | 114.4 ± 18.4a | 148.2 ± 25.0b | 136.2 ± 17.6b | 141.8 ± 21.6b | 130.8 ± 13.8ab | 141.3 ± 13.0b | ||

| Seed weight (SW) | 74.2 ± 10.1 | 69.0 ± 10.2 | 80.1 ± 9.0 | 75.8 ± 9.2 | 77.2 ± 13.6 | 70.9 ± 10.9 | 75.2 ± 8.3 | A |

| 78.7 ± 11.6 | 65.3 ± 8.7a | 84.3 ± 13.2b | 79.3 ± 10.1b | 84.6 ± 12.4b | 77.2 ± 9.3ab | 84.0 ± 6.8b | ||

| Total yield (YLDt) | 58.3 ± 8.9 | 51.6 ± 7.8a | 63.5 ± 6.8b | 59.9 ± 7.8ab | 61.5 ± 11.9ab | 55.8 ± 10.2ab | 60.0 ± 6.9ab | A |

| 61.8 ± 9.7 | 50.2 ± 8.3a | 66.4 ± 10.2b | 62.2 ± 8.6b | 66.9 ± 10.0b | 60.8 ± 7.7b | 66.5 ± 5.5b | ||

| Standard yield (YLDs) | 56.3 ± 8.6 | 48.3 ± 7.3a | 59.4 ± 3.6b | 58.5 ± 7.9b | 60.2 ± 11.1b | 54.4 ± 10.4ab | 58.6 ± 6.3b | A |

| 59.3 ± 9.6 | 46.6 ± 6.1a | 63.4 ± 9.3b | 60.5 ± 8.6b | 64.9 ± 8.9b | 58.6 ± 7.6b | 64.1 ± 5.4b | ||

|

| ||||||||

| Hulling rate (HR) | 74.6 ± 4.5 | 69.1 ± 4.8a | 73.6 ± 5.5ab | 76.0 ± 2.5b | 76.9 ± 1.2b | 75.2 ± 4.7b | 76.9 ± 1.5b | A |

| 75.3 ± 3.3 | 71.5 ± 4.0a | 75.3 ± 3.3ab | 76.2 ± 1.9b | 76.7 ± 1.2b | 75.8 ± 3.4b | 76.4 ± 2.5b | ||

| Grain apperance (GA) | 49.3 ± 29.1 | 8.5 ± 12.3a | 40.9 ± 18.7b | 32.0 ± 17.9b | 74.7 ± 7.6c | 65.8 ± 17.0c | 78.4 ± 11.2c | B |

| 50.8 ± 25.1 | 10.5 ± 9.3a | 51.1 ± 14.4bc | 40.5 ± 18.2b | 71.8 ± 6.9cd | 62.3 ± 17.8cd | 72.4 ± 6.2d | ||

| Immature seeds (IMS) | 45.5 ± 26.4 | 81.9 ± 10.9c | 53.2 ± 18.8b | 61.2 ± 15.5b | 22.4 ± 8.5a | 30.2 ± 16.1a | 19.6 ± 11.4a | B |

| 42.5 ± 22.6 | 79.9 ± 7.8d | 42.2 ± 13.4bc | 50.3 ± 15.1c | 22.3 ± 8.7a | 32.3 ± 16.3ab | 24.3 ± 5.4a | ||

| Grain length (GL) | 4.9 ± 0.2 | 4.9 ± 0.2ab | 4.8 ± 0.1ab | 4.7 ± 0.2a | 4.9 ± 0.1ab | 4.9 ± 0.1ab | 5.0 ± 0.2b | D |

| 5.0 ± 0.2 | 5.0 ± 0.2ab | 5.0 ± 0.1ab | 4.8 ± 0.2a | 5.0 ± 0.1ab | 5.1 ± 0.1b | 5.2 ± 0.1b | ||

| Grain wideth (GW) | 2.9 ± 0.1 | 2.8 ± 0.1a | 2.9 ± 0.1ab | 2.9 ± 0.1b | 2.9 ± 0.1ab | 2.8 ± 0.1a | 2.9 ± 0.1ab | D |

| 2.9 ± 0.1 | 2.9 ± 0.1ab | 2.9 ± 0.1ab | 3.0 ± 0.1b | 2.9 ± 0.1ab | 2.9 ± 0.1a | 2.9 ± 0.1ab | ||

| Grain thickness (GT) | 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.2a | 2.0 ± 0.1ab | 2.1 ± 0.0b | 2.0 ± 0.0ab | 2.0 ± 0.0ab | 2.0 ± 0.0b | C |

| 2.0 ± 0.1 | 1.9 ± 0.2a | 2.0 ± 0.1ab | 2.1 ± 0.0b | 2.0 ± 0.0ab | 2.0 ± 0.0ab | 2.0 ± 0.1ab | ||

| Whiteness of brown rice (WB) | 20.3 ± 1.7 | 22.2 ± 1.1d | 20.4 ± 1.0bc | 21.5 ± 2.1cd | 18.2 ± 0.5a | 19.2 ± 0.9ab | 19.5 ± 0.5ab | B |

| 20.7 ± 1.8 | 23.2 ± 0.9b | 19.4 ± 1.6a | 21.7 ± 2.1b | 19.0 ± 0.6a | 20.0 ± 0.8a | 20.0 ± 0.5a | ||

| Whiteness of white rice (WW) | 41.2 ± 2.0 | 40.5 ± 2.2 | 41.9 ± 1.9 | 42.2 ± 2.3 | 40.1 ± 1.3 | 40.1 ± 1.3 | 41.1 ± 1.5 | D |

| 41.4 ± 1.7 | 41.3 ± 1.4 | 41.2 ± 2.2 | 41.9 ± 2.2 | 40.2 ± 0.8 | 41.2 ± 1.7 | 41.4 ± 1.3 | ||

| Protein content (PC) | 7.0 ± 0.7 | 7.7 ± 0.6b | 6.5 ± 0.7a | 7.0 ± 0.8ab | 7.0 ± 0.3ab | 7.0 ± 0.6ab | 6.6 ± 0.3a | A |

| 6.8 ± 0.8 | 7.6 ± 0.7b | 6.4 ± 0.9a | 6.9 ± 0.9ab | 6.6 ± 0.5ab | 6.7 ± 0.5a | 6.5 ± 0.4a | ||

| Hull-cracked rice (HC) | 17.5 ± 17.0 | 7.4 ± 8.6a | 12.5 ± 10.6ab | 16.0 ± 21.9ab | 9.1 ± 6.2ab | 29.1 ± 19.9b | 24.8 ± 14.3ab | C |

| 13.1 ± 10.9 | 3.1 ± 3.5a | 13.0 ± 12.2ab | 11.0 ± 10.2ab | 9.2 ± 5.2ab | 21.8 ± 12.2b | 18.0 ± 9.1b | ||

| Amylose content (AC) | 21.0 ± 2.2 | 22.2 ± 1.0b | 21.8 ± 1.4b | 21.3 ± 1.4b | 22.5 ± 1.4b | 20.9 ± 1.5ab | 19.1 ± 2.4a | A |

| 21.5 ± 1.8 | 21.9 ± 1.1b | 22.9 ± 0.8b | 21.8 ± 1.4b | 22.6 ± 1.5b | 21.7 ± 1.4ab | 20.0 ± 2.0a | ||

Upper and lower rows indicate phenotype values in 2013 and 2014, respectively. Different letters indicate significant differences at p < 0.05.

Genetic population structure (Shinada et al. 2014).

Discussion

During long-term breeding processes, current rice varieties finely adapt to specific conditions. One of the aims of plant breeding programs is to combine different rice varieties exhibiting the best performance under the specific conditions in which they were developed. The results of the present study have some implications for rice breeding programs. Wide variations were observed in all 26 agro-economical traits with continuous distributions (Supplemental Table 2, Fig. 1). In 16 trait combinations, 13 positive and three negative correlations were observed (Supplemental Table 3). Nineteen out of the 26 agro-economical traits showed significant differences (Table 2). These phenotypic changes paralleled with changes in the genetic population structure, indicating that the objectives in rice breeding programs at that time focused on these traits and the improvements were achieved.

Genomes in local populations are structured by the artificial selection of the genotype × environmental conditions in recurrent cycles of hybridization among local populations or with an exotic germplasm during plant breeding programs (Shinada et al. 2014). This process may generate genetic variations desirable to local populations and shape adaptability during the establishment of local populations (Fujino et al. 2015a). Plant breeding programs also generate intensive selection pressure with a focus on the shaping of adaptability to local environmental conditions, cultivation methods, and market demands. Although the use of exotic varieties without adaptability is challenging for plant breeding programs, this may achieve improvements in traits for human demands. The dynamics of hybridization combinations and artificial selection on desirable phenotypes in each generation may result in genetic and phenotypic diversity among local populations.

Phenotypic changes lead to a stable and high yield with high eating quality; a short culm, large number of tillers, small panicle, and lower protein and amylose contents. Significant differences were detected in eight traits between Groups I and II (Table 2). These traits were involved in plant architecture in these specific conditions. Since these traits were visible, they were selected in the early phase of the rice breeding programs in Hokkaido. On the other hand, a significant difference was observed in AC between Groups IV and V. AC is involved in eating quality, which has been targeted since the 1980s to meet demands in Japan (Juliano et al. 1964, 1993). This improvement was dependent on knowledge of grain quality and the application of evaluation machines into breeding programs.

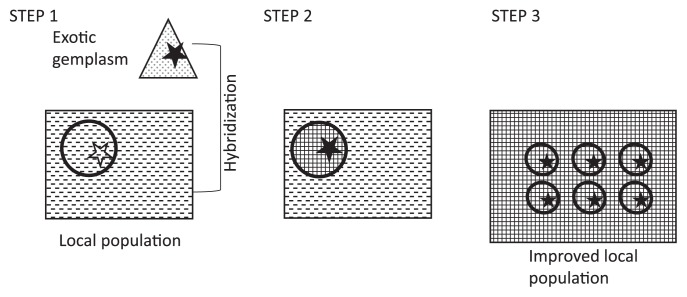

In addition to genetic characteristics (Fujino et al. 2015a, Shinada et al. 2014), theses phenotypic changes may provide a model for the artificial selection during rice breeding programs in Hokkaido (Fig. 2). Breeders may conduct selections for the desirable trait(s) among populations derived from hybridization using an exotic germplasm. Once the desirable trait(s) have been transferred into the group, the trait(s) may immediately disperse among the population within the group. For example, AC was decreasing in the group IV, then decreased in group V (Table 2).

Fig. 2.

Proposed model for the artificial selection of phenotypes during rice breeding programs in Hokkaido. STEP 1: Hybridization using the exotic germplasm (triangle) was performed to meet human demands. STEP 2: The desirable phenotypes were successfully transferred from exotic germplasm into the population by artificial selection for the traits. The desirable trait(s) and other trait(s), which shape adaptability, might be both transferred. STEP 3: During the process of rice breeding, desired phenotype related allele is dispersed among local population to generate a new genetic structure in the population. Square and Circle indicate population and variety, respectively. Square size indicates the degree of the genetic diversity. Closed and open star means the desirable and undesirable trait(s), respectively. Pattern shows the genotype.

Plant breeding programs have generally restricted genetic diversity among local populations due to establishing an ideotype for the objectives of current breeding programs (Cowling 2013, Dilday 1990, Fu et al. 2003, Le Clerc et al. 2005, Roussel et al. 2005, Yamamoto et al. 2010). Patterns A, B, and C observed in this study (Table 2) may be caused by a few genes. Trait improvements have been completed by the transfer of single or double events, suggesting that the elite characteristics in current varieties in the local population may be controlled by a simple genetic base. Recently, breeding lines have been used for GWAS to enhance the identification of genes for agro-economical traits (Begum et al. 2015, Klos et al. 2016, Poets et al. 2016).

Rice breeding programs have been performed using the artificial selection for phenotypes. The cycle in Fig. 2 might be completed in several times within 100-year rice breeding programs in Hokkaido. The breeding strategies in Hokkaido are not only successful for achieving improvements in traits (Table 2), but also generate new genotypes, leading to enlarge the genetic diversity in the local population (Fujino et al. 2015a, Shinada et al. 2014). This is the genetic force of the 100-year rice breeding programs in Hokkaido.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by a grant from the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries of Japan (Science and Technology Research Promotion Program for Agriculture, Forestry, Fisheries and Food Industry).

Literature Cited

- Agrama, H.A., Yan, W.G., Jia, M., Fjellstrom, R. and McClung, A.M. (2010) Genetic structure associated with diversity and geographic distribution in the USDA rice world collection. Natural Sci. 2: 247–291. [Google Scholar]

- Ali, M.L., McClung, A.M., Jia, M.H., Kimball, J.A., McCouch, S.R. and Eizenga, G. (2011) A rice diversity panel evaluated for genetic and agro-morphological diversity between subpopulations and its geographic distribution. Crop Sci. 51: 2021–2035. [Google Scholar]

- Ando, I., Sato, H., Aoki, N., Suzuki, Y., Hirabayashi, H., Kuroki, M., Shimizu, H., Ando, T. and Takeuchi, Y. (2010) Genetic analysis of the low-amylose characteristics of rice cultivars Oborozuki and Hokkai-PL9. Breed. Sci. 60: 187–194. [Google Scholar]

- Begum, H., Spindel, J.E., Lalusin, A., Borromeo, T., Gregorio, G., Hernandez, J., Virk, P., Collard, B. and McCouch, S.R. (2015) Genome-wide association mapping for yield and other agronomic traits in an elite breeding population of tropical rice (Oryza sativa). PLoS ONE 10: e0119873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtois, B., Frouin, J., Greco, R., Bruschi, G., Droc, G., Hamelin, C., Ruiz, M., Clément, G., Evrard, J.C., Van Coppenole, S.et al. (2012) Genetic diversity and population structure in a European collection of rice. Crop Sci. 52: 1663–1675. [Google Scholar]

- Cowling, W.A. (2013) Sustainable plant breeding. Plant Breed. 132: 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Dilday, R. (1990) Contribution of ancestral lines in the development of new cultivars of rice. Crop Sci. 30: 905–911. [Google Scholar]

- Ebana, K., Kojima, Y., Fukuoka, S., Nagamine, T. and Kawase, M. (2008) Development of mini core collection of Japanese rice landrace. Breed. Sci. 58: 281–291. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, Y., Peterson, G.W., Scoles, G., Rossnagel, B., Schoen, D. and Richards, K. (2003) Allelic diversity changes in 96 Canadian oat cultivars released from 1886 to 2001. Crop Sci. 43: 1989–1995. [Google Scholar]

- Fujino, K. and Sekiguchi, H. (2005a) Identification of QTLs conferring genetic variation for heading date among rice varieties at the northern-limit of rice cultivation. Breed. Sci. 55: 141–146. [Google Scholar]

- Fujino, K. and Sekiguchi, H. (2005b) Mapping of QTLs conferring extremely early heading in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 111: 393–398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino, K., Yamanouchi, U. and Yano, M. (2013) Roles of Hd5 gene controlling heading date for adaptation to the northern limits of rice cultivation. Theor. Appl. Genet. 126: 611–618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino, K., Obara, M., Ikegaya, T. and Tamura, K. (2015a) Genetic shift in local rice populations during rice breeding programs in the northern limit of rice cultivation in the world. Theor. Appl. Genet. 128: 1739–1746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujino, K., Obara, M., Shimizu, T., Koyanagi, K.O. and Ikegaya, T. (2015b) Genome-wide association mapping focusing on a rice population derived from rice breeding programs in a region. Breed. Sci. 65: 403–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juliano, B.O., Bautista, G.M., Lugay, J.C. and Reyes, A.C. (1964) Rice quality, studies on physicochemical properties of rice. J. Agric. Food Chem. 12: 131–138. [Google Scholar]

- Juliano, B.O., Perez, C.M. and Cuevas-Perez, F. (1993) Screening for stable high head rice yields in rough rice. Cereal Chem. 70: 650–655. [Google Scholar]

- Klos, K.E., Huang, Y.F., Bekele, W.A., Obert, D.E., Babiker, E., Beattie, A.D., Bjørnstad, Å, Bonman, J.M., Carson, M.L., Chao, S.et al. (2016) Population genomics related to adaptation in elite oat germplasm. Plant Genome 9. doi: 10.3835/plantgenome2015.10.0103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kojima, Y., Ebana, K., Fukuoka, S., Nagamine, T. and Kawase, M. (2005) Development of an RFLP-based rice diversity research set of germplasm. Breed. Sci. 55: 431–440. [Google Scholar]

- Le Clerc, V., Bazante, F., Baril, C., Guiard, J. and Zhang, D. (2005) Assessing temporal changes in genetic diversity of maize varieties using microsatellite markers. Theor. Appl. Genet. 110: 294–302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poets, A.M., Mohammadi, M., Seth, K., Wang, H., Kono, T.J., Fang, Z., Muehlbauer, G.J., Smith, K.P. and Morrell, P.L. (2016) The effects of both recent and long-term selection and genetic drift are readily evident in north American barley breeding populations. G3 (Bethesda) 6: 609–622. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roussel, V., Leisova, L., Exbrayat, F., Stehno, Z. and Balfourier, F. (2005) SSR allelic diversity changes in 480 European bread wheat varieties released from 1840 to 2000. Theor. Appl. Genet. 111: 162–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinada, H., Iwata, N., Sato, T. and Fujino, K. (2013) Genetical and morphological characterization of cold tolerance at fertilization stage in rice. Breed. Sci. 63: 197–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinada, H., Yamamoto, T., Yamamoto, E., Hori, K., Yonemaru, J., Matsuba, S. and Fujino, K. (2014) Historical changes in population structure during rice breeding programs in the northern limits of rice cultivation. Theor. Appl. Genet. 127: 995–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takemoto-Kuno, Y., Mitsueda, H., Suzuki, K., Hirabayashi, H., Ideta, O., Aoki, N., Umemoto, T., Ishii, T., Ando, I., Kato, H.et al. (2015) qAC2, a novel QTL that interacts with Wx and controls the low amylose content in rice (Oryza sativa L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 128: 563–573. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, D.A., Lu, B.R. and Tomooka, N. (2008a) Was Asian rice (Oryza sativa) domesticated more than once? Rice 1: 16–24. [Google Scholar]

- Vaughan, D.A., Lu, B.R. and Tomooka, N. (2008b) The evolving story of rice evolution. Plant Sci. 174: 394–408. [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto, T., Nagasaki, H., Yonemaru, J., Ebana, K., Nakajima, M., Shibaya, T. and Yano, M. (2010) Fine definition of the pedigree haplotypes of closely related rice cultivars by means of genome-wide discovery of single-nucleotide polymorphisms. BMC Genomics 11: 267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan, W., Rutger, J.N., Bryant, R.J., Bockelman, H.E., Fjellstrom, R.G., Chen, M.H., Tai, T.H. and McClung, A.M. (2007) Development and evaluation of a core subset of the USDA rice germplasm collection. Crop Sci. 47: 869–876. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.