Abstract

Background

Influenza infection is a common disease with a huge disease burden. Influenza vaccination has been widely used, but concerns regarding vaccine efficacy exist, especially in the elderly. Probiotics are live microorganisms with immunomodulatory effects and may enhance the immune responses to influenza vaccination.

Methods

We conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis to determine the influence of prebiotics/probiotics/synbiotics supplementation on vaccine responses to influenza vaccination. Studies were systematically identified from electronic databases up to July 2017. Information regarding study population, influenza vaccination, components of supplements, and immune responses were extracted and analyzed. Twelve studies, investigating a total of 688 participants, were included in this review.

Results

Patients with prebiotics/probiotics supplements were found to have higher influenza hemagglutination inhibition antibody titers after vaccination (for A/H1N1, 42.89 vs 35.76, mean difference =7.14, 95% CI =2.73, 11.55, P=0.002; for A/H3N2, 105.4 vs 88.25, mean difference =17.19, 95% CI =3.39, 30.99, P=0.01; for B strain, 34.87 vs 30.73, mean difference =4.17, 95% CI =0.37, 7.96, P=0.03).

Conclusion

Supplementation with prebiotics or probiotics may enhance the influenza hemagglutination inhibition antibody titers in all A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and B strains (20%, 19.5%, and 13.6% increases, respectively). Concomitant prebiotics or probiotics supplementation with influenza vaccination may hold great promise for improving vaccine efficacy. However, high heterogeneity was observed and further studies are warranted.

Keywords: influenza, influenza vaccine, probiotics, prebiotics, synbiotics, antibody titer, immune response

Introduction

Influenza is a common infectious disease with a huge disease burden worldwide. It is estimated to be responsible for 250,000–500,000 deaths annually, especially among the elderly.1 Influenza vaccination prevents influenza infection. Usually, the influenza vaccine is composed of split virions with 2 A strains (A/H1N1 and A/H3N2) and 1 B strain (Victoria or Yamagata lineages). Influenza vaccines are widely used, but concerns regarding vaccine efficacy exist, especially in the elderly. In a meta-analysis published in 2012, the pooled efficacy was 59% in adults aged 18–65 years, and evidence of protection in the elderly was lacking.2 Low vaccine efficacy leads to inadequate protection, breakthrough infection, and influenza-related morbidity and mortality. Efforts have been made to improve the immune responses to influenza vaccines, such as adding adjuvant supplements, nutritional interventions, or increasing the vaccine dose.3,4 In summary, the efficacy of the current influenza vaccine is not satisfactory.

The human intestine is host to a vast variety of microbes. Probiotics are microorganisms that have beneficial properties for the host and are known to alter the intestinal microflora.5,6 Prebiotics are defined as dietary components that stimulate the growth and metabolic activity of probiotics. Synbiotics are the combination of prebiotics and probiotics. Application of prebiotics/probiotics/synbiotics suppresses the growth of pathogenic bacteria and improves the intestinal barrier function, and is widely used in patients with gastrointestinal infections and inflammation.7,8 In addition to the beneficial effects on the intestinal tract, probiotics also have immunomodulatory effects by inducing production of protective cytokines and suppressing pro-inflammatory cytokines.9–12 Extraintestinal benefits of probiotics include immune regulations in allergic diseases, cardiovascular diseases, and suppression of tumor growth.13–15 Adjuvant probiotic use in these diseases is a potential target for future development.

The beneficial properties of immune modulation that follow probiotics consumption may enhance the immune responses to influenza vaccines.16–20 Several randomized controlled trials (RCTs) have been conducted to investigate the influence of probiotics on influenza vaccines, but the results were inconsistent and inconclusive. Therefore, we conducted this systematic review and meta-analysis to evaluate the impacts of prebiotics/probiotics/synbiotics on immune responses after influenza vaccination.

Materials and methods

Study design and study selection

This study was approved by the Ethics Committees of MacKay Memorial Hospital, Taiwan (IRB No: 16MMHIS174e) and conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols guidelines.21 We systematically searched for all relevant articles in the following online databases: Embase, PubMed, the Cochrane Library, the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health, the Airiti Library, and the PerioPath Index to the Taiwan Periodical Literature in Taiwan, from the earliest record to July 2017. The Cochrane Collaboration Central Register of Controlled Clinical Trials, Cochrane Systematic Reviews, and ClinicalTrials.gov were manually searched for additional references. The key terms used for the search were “influenza vaccine”, “probiotics”, “prebiotics”, and “synbiotics”. Keywords were combined using Boolean searches and the search was made using keywords, Boolean operators, and MeSH descriptor. The detailed search strategy is enclosed as Box S1. Two authors (P-CS and S-JL) conducted the search independently, and disagreements were resolved through discussion with the third author (W-TL).

After the initial search, 2 independent reviewers (P-CS and T-LY) assessed the eligibility of each publication. The inclusion criteria of selected RCTs were as follows: 1) studies in adults; 2) inclusion of a control group in the study design; 3) use of influenza vaccination and supplementation of probiotics, prebiotics, or synbiotics in the intervention group; 4) reporting of at least 1 immunological response to influenza vaccination. We excluded the following: 1) articles irrelevant to the topic; 2) duplicate publications; 3) trials of a cross-over study design; and 4) studies in which the control arm received an effective intervention rather than a placebo.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Two authors (W-TL and T-LY) independently evaluated the quality assessment of all eligible articles using the Cochrane Review risk of bias assessment tool. We assessed the adequacy of randomization, allocation concealment, blinding methods, implementation of the intent-to-treat analysis, dropout rate, complete outcome data, selective data reporting, and other biases of each enrolled publication.

The articles were scrutinized, and data regarding study population, influenza vaccine components, protocols of probiotics consumption, details of vaccine immune responses, and adverse effects from the selected studies were extracted. Discrepancies between the 2 independent evaluations for potential articles were resolved through discussion and consensus. The primary outcome was the immunogenicity of influenza vaccination, presented as hemagglutination inhibition (HI) antibody titers. The HI antibody titer equals the maximum dilution capable of inhibiting the agglutination of guinea pig red blood cells, with the influenza viruses under standardized conditions.22 Other comparative variables included the components of the vaccine and probiotics, the protocols of probiotics consumption, and the serious adverse effects.

Data synthesis and analysis

Immunogenicity data from all the studies were extracted, analyzed, and compared to determine differences in the efficacy of influenza vaccination in the groups receiving prebiotics/probiotics/synbiotics supplementation and the placebo groups. Due to significant (and expected) heterogeneity among the studies, a random effects model was employed.23 The results were represented by a point estimate with a 95% CI. The heterogeneity across studies was tested using I2 and Cochran’s Q tests. A P-value <0.10 for chi-square testing of the Q statistic or an I2>50% was considered as statistically significant heterogeneity.24 A sensitivity analysis was performed by removing some studies to observe whether the action caused serious changes in the overall results. The potential publication bias was assessed by observing the symmetry of funnel plots and using Egger’s test.25 Review Manager (version 5.3.5) was used for our analyses.

Results

Description of studies and quality assessment

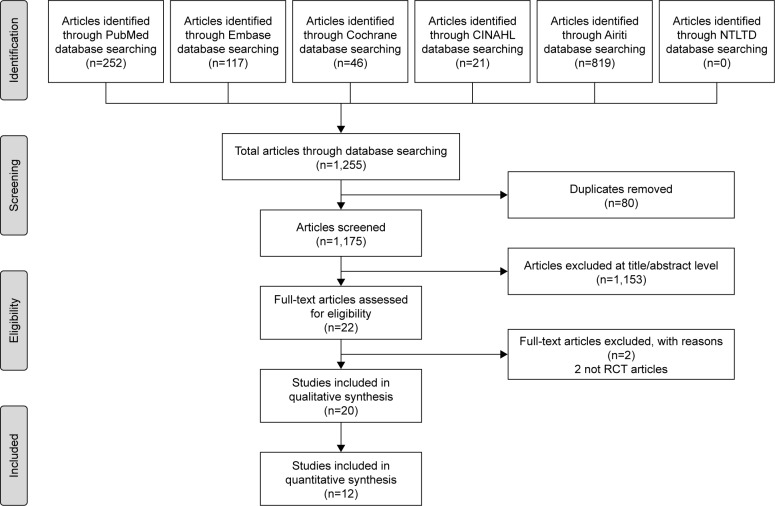

Of the 22 non-duplicate citations identified from the literature, 2 studies were not RCTs and 20 were ultimately assessed for eligibility (Figure 1). Finally, 11 publications with 12 RCTs were included in our qualitative synthesis after critical review (Table 1).26–36 Two trials (a pilot and a confirmatory study) with different patient numbers, treatment protocols, and years of study were published in the same article.34 Seven studies investigated the effects of probiotics, and five studies investigated the effects of prebiotics. One study investigating synbiotics was excluded, after critical review, for using a different outcome parameter.37 The included studies were conducted in the USA, France, Japan, and the UK. In total, 780 patients were enrolled in these studies with female predominance (M:F =1:2.1). Five different probiotics and 5 different prebiotics were used in the intervention arm. The trivalent inactivated influenza vaccines (TIV) were used in most studies (10/12). Most of the included studies had a low bias, as shown by our quality assessment using the Cochrane assessment tool. The detailed quality assessment of each included study is shown in Table S1.

Figure 1.

Flow diagram showing the selection of articles for review.

Abbreviations: CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health; NTLTD, Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations; RCT, randomized controlled trials.

Table 1.

Characteristics of randomized controlled trials investigating the influence of prebiotics/probiotics on influenza vaccination

| Reference, year | Country | Participants (M%:F%) | Age (years; mean [SD]) | Supplement duration: total weeks (before/after vaccination) | Strains of supplements | Type of vaccine | Components of vaccine | Severe adverse events |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotics | ||||||||

| Olivares et al, 200767 | Spain | 50 healthy adults (62%:38%) | 33.00 (7.70) | 4 (2/2) | Lactobacillus fermentum CECT5716 l×1010 CFU daily | TIV | H1N1: New Caledonia/20/99 H3N2: Fujian/411/2002 B: Shanghai/361/2002 |

Nil |

| French and Penny, 200968 | Australia | 47 healthy adults (41%:59%) | 31.55 (6.72) | 6 (214) | L. fermentum VRI 003 1×109 CFU | TIV | H1N1: New Caledonia/20/99 H3N2: Wisconsin/67/2005 B: Malaysia/2506/2004 |

30 |

| Boge et al, 2009 (pilot)34,a | France | 68 adults in nursing home (44%:56%) | 83.64 (7.70) | 7 (4/3) | L. casei DN-114 001 twice daily | TIV | H1N1: New Caledonia/20/99 H3N2: Wisconsin/67/2005 B: Malaysia/2506/2004 |

NR |

| Boge et al, 2009 (confirmed)34,a | France | 222 elders in nursing home (33%:67%) | 84.64 (6.72) | 13 (4/9) | L. casei DN-114 001 twice daily | TIV | H1N1: New Caledonia/20/99 H3N2: California/7/2004 B: Shanghai/361/2002a B: Jiangsu/10/2003a |

30 |

| Namba et al, 201033,a | Japan | 27 elders in health care facility (11%:89%) | 86.70 (6.60) | 20 (3/17) | Bifidobacterium longum BB536 l×1011 CFU daily | TIV | H1N1: New Caledonia/20/99 H3N2: Wyoming/3/2003 B: Shanghai/361/2002 |

NR |

| Davidson et al, 201132,a | USA | 42 healthy adults (38%:62%) | 33.30 | 4 (4/0) | L rhamnosus GG 1×1010 CFU twice daily | LA1V | H1N1: Solomon lslands/3/2006 H3N2: Wisconsin/67/2005 B: Malaysia/2506/2004 |

1 |

| Van Puyenboreck et al, 201269 | Belgium | 737 healthy adults in nursing home (25%:75%) | 84.06 | 25 (3/22) | L. casei Shirola 6.5×109 CFU twice daily | TIV | H1N1: Solomon Islands/3/2006 IVR-145 H3N2: Wisconsin/67/2005 Malaysia/2506/2004 |

NR |

| Rizzardini et al, 201270 | Italy | 211 healthy adults (44%:56%) | 33.2 | 6 (2/4) | BB-12® (DSM15954) 1×109 CFU L. casei 431® (ATCC55544) daily | TIV | H1N1: Brisbane/59/2007 H3N2: Uruguay/716/2007 B: Florida/4/2006 |

Nil |

| Bosch et al, 201271 | Spain | 60 adults in nursing home (NR) | 65–85 | 12 (0/12) |

L. plantarum CECT7315/7316 daily Group A: 5×109 CFU Group B: 5×108 CFU |

TIV | H1N1: Solomon Islands/3/2006 1VR-145 H3N2: Wisconsin/67/2005 B: Malaysia/2506/2004 |

NR |

| Akatsu et al, 2013 (paper)30,a | Japan | 45 enteral tube feeding adults (29%:71%) | 81.70 (8.70) | 12 (4/8) | Bifidobacterium strain, BB536 5×1010 CFU twice daily | TIV | H1N1: Brisbane/59/2007 H3N2: Uruguay/716/2007 B: Brisbane/60/2008 |

Nil |

| Akatsu et al, 2013 (letter)30,a | Japan | 15 adults in nursing home (47%:53%) | 75.74 (7.22) | 12 (3/9) | L. paracasei MoLac 1×1011 CFU | TIV | A/H1N1: Brisbane/59/2007 A/H3N2: Uruguay/716/2007 B strain: Brisbane/60/2008 |

NR |

| Jespersen et al, 201572 | Germany, Denmark | 1,104 healthy adults (41%:59%) | 31.45 | 6 (3/3) | L. casei 43/(ATCC55544) l×109 CFU daily | TIV | A/H1N1: Califonia/7/2009 A/H3N2: Perth/16/2009 B strain: Brisbane/60/2008 |

5 |

| Maruyama et al, 201626,a | Japan | 42 elders in nursing home (19%:81%) | 87.15 (5.71) | 6 (3/3) | L. paracasei MCC 1,849 1×1011 CFU daily | TIV | A/H1N1: California/7/2009 pdm09 A/H3N2: Texas/50/2012 B strain: Massachusetts/2/2012 (Yamagata lineage) |

Nil |

| Prebiotics | ||||||||

| Bunout et al, 200273 | Chile | 66 healthy elders (similar%) | 75.73 | 28 (1/27) | FOS (70% raftilose 30% raftiline) 2 sachets daily | TIV | A/H1N1: Caledonia A/H3N2: Moscow, Sydney B strain: Belgium (code 184–93) |

3 |

| Langkamp-Henken et al, 200436,a | USA | 66 healthy elders (47%:53%) | 81.54 (1.35) | 26 (2/24) | High oleic safflower oil, soybean oil, FOS, structured TG 8 oz daily | TIV | A/H1N1: Beijing/262/95 A/H3N2: Sydney/5/97 B strain: Yamanashi/166/98 (B/Beijing/184/93-like) |

NR |

| Langkamp-Henken et al, 200635,a | USA | 157 frail elders in LTCI facilities (28%:72%) | 83.36 (0.80) | 10 (4/6) | Antioxidants, B vitamins, selenium, zinc, FOS, structured TG 240 mL daily | TIV | A/H1N1: Caledonia/20/99 A/H3N2: Panama/2007/99 B strain: Hong Kong/1434/2002 |

NR |

| Nagafuchi et al, 201528,a | Japan | 24 enteral tube feeding elders (46%:54%) | 80.30 (9.80) | 14 (4/10) | BGS (1.65 µg/100 kcal), DHNA, GOS (0.4 g/100 kcal), fermented milk products | TIV | A/H1Nl: California/7/2009 A/H3N2: Victoria/210/2009 B strain: Brisbane/60/2008 |

Nil |

| Lomax et al, 201529,a | UK | 49 healthy adults (26%:74%) | 54.98 | 8 (4/4) | 50:50 mixture of long-chain inulin and oligofructose 8 g daily | TIV | A/H1N1: Brisbane/59/2007-like A/H3N2: Brisbane/10/2007-like B strain: Florida/4/2006-like |

NR |

| Akatsu et al, 201627,a | Japan | 23 PEG-fed bedridden elders (13%:87%) | 78.98 (9.09) | 8 (4/4) | Heat-treated lactic acid bacteria fermented milk products, GOS 4 g/day, BGS 0.4 g/day | LAIV | A/H1N1: Solomon Islands/3/2006 A/H3N2: Hiroshima/52/2005 B strain: Malaysia/2506/2004 |

NR |

| Synbiotics | ||||||||

| Enani et al, 201737 | UK | 112 healthy adults (NR) | 18–35 60–85 | 8 (4/4) | Bifidobacterium longum l×109 CFU with GI-OS 8 g daily | TIV | A/H1N1: California/17/2009 pdm09 A/H3N2: Perth/16/2009 B strain: Brisbane/60/2008 |

NR |

Note:

Included in meta-analysis.

Abbreviations: BGS, bifidogenic growth stimulator; CFU, colony-forming unit; DHNA, 1,4-dihydroxy-2-naphthoic acid; FOS, fructooligosaccharides; GOS, galactooligosaccharide; LAIV, live attenuated influenza vaccine; LTC, long term care facilities; Nil, no serious adverse events; NR, not reported; PEG, percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy; TG, triglycerol; TIV, trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine.

Data synthesis and meta-analysis

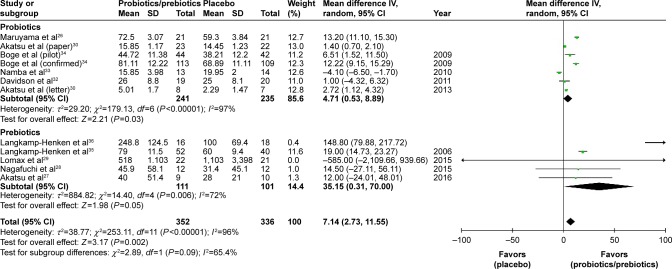

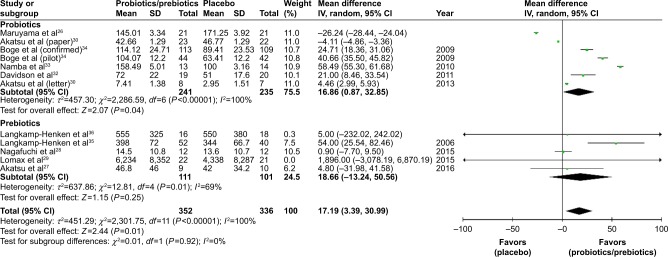

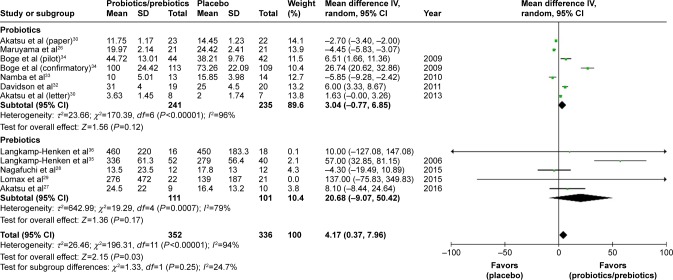

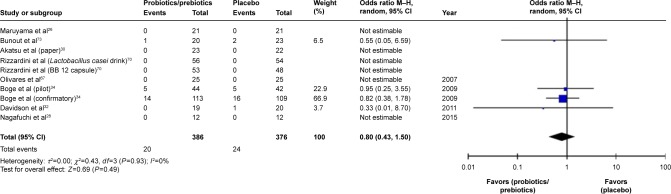

Ultimately, 688 patients were enrolled in our meta-analysis. By comparing the HI titers of strain A/H1N1 after influenza vaccination, we found a significantly higher HI titers in the probiotics/prebiotics group (42.89 vs 35.76, mean difference =7.14, 95% CI =2.73, 11.55, P<0.001, I2=96%) (Figure 2). For strain A/H3N2, similar increase in HI titers was observed (105.4 vs 88.25, mean difference =17.19, 95% CI =3.39, 30.99, P<0.001, I2=100%) (Figure 3). In patients with prebiotics/probiotics supplement, higher immune responses after influenza vaccination was noticed for strain B (34.87 vs 30.73, mean difference =4.17, 95% CI =0.37, 7.96, P<0.001, I2=94%) (Figure 4). The percentages of increases were 20% (A/H1N1), 19.5% (A/H3N2), and 13.6% (B strain); the mean HI antibody titers are summarized in Table 2. Subgroup analysis of prebiotics and probiotics showed similar results. The heterogeneity was high in all analyses. We found no significant differences in serious adverse effects in either arm (Figure 5). The funnel plots were also assessed (Figures S1–S3).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of the HI titers of A/H1N1 strain after influenza vaccination between the prebiotic or probiotic group, and the placebo group.

Abbreviations: HI, hemagglutination inhibition; IV, inverse variance.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of the HI titers of A/H3N2 strain after influenza vaccination between prebiotic or probiotic group, and placebo group.

Abbreviations: HI, hemagglutination inhibition; IV, inverse variance.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of the HI titers of B strain between prebiotic or probiotic group, and placebo group.

Abbreviations: HI, hemagglutination inhibition; IV, inverse variance.

Table 2.

The mean hemagglutination inhibition antibody titers of vaccine strains in probiotics/prebiotics and control groups

| Vaccine strain | Probiotics/prebiotics group | Control group | Mean differences (% of increase) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/H1N1 | 42.89 | 35.76 | 7.14 (20) | 0.002 |

| A/H3N2 | 105.4 | 88.25 | 17.19 (19.5) | 0.01 |

| B | 34.87 | 30.73 | 4.17 (13.6) | 0.03 |

Figure 5.

Forest plot of the incidence of adverse effect between prebiotic or probiotic group, and placebo group.

Abbreviation: M–H, Mantel–Haenszel method.

Discussion

Our systematic review and meta-analysis support the beneficial effects of prebiotic/probiotic supplementation on humoral responses to influenza vaccination. We found that supplementation with pre- or probiotics enhanced the HI titers in all A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and B strains (20%, 19.5%, and 13.6% increases in HI antibody titers, respectively). Concomitant prebiotics/probiotics supplementation potentially improved the protection of influenza vaccination and decreased the subsequent risk of influenza-related morbidity and mortality. However, high heterogeneity was noted and further studies are warranted to consolidate this suggestion.

Influenza is highly contagious and virulent. Despite widespread use of influenza vaccination, it remains an important health threat. Currently, the effectiveness of influenza vaccination is not satisfactory and multiple factors contribute to the low effectiveness, including antigen drift, season mismatch, and manufacture technique limitations.2,38,39 Elderly individuals have both the highest burden of disease and the lowest immune responses to vaccination.40–42 The protection rate may be as low as 30% in elderly people after vaccination and little evidence is found supporting the benefits of influenza vaccination in the elderly.40,41 Immunosenescence, gradual deterioration of the immune system brought on by natural aging, also plays an important role in the hyporesponsiveness of influenza vaccination.43 Poorer nutritional status and higher rates of comorbid diseases are also important reasons for the nearly inevitable weak immune responses after vaccination in the elderly.44,45 The TIV with high doses (4× the standard dose) induced significantly higher antibody responses in elderly people, but are not widely used.3 Supplementation with prebiotics/probiotics may provide a simple, convenient, and practical solution.16–18,20,46,47 Besides, probiotics consumption may have beneficial effects in preventing respiratory tract infections and influenza-related illnesses.48,49 Our study provided comprehensive evidence that prebiotic/probiotic use will enhance the HI antibody titer after influenza vaccination. In addition, the immunogenicity of influenza vaccination may be affected by the components of vaccine strains. Compared with A/H1N1 and A/H3N2 strains, poorer antigen immunogenic responses in B strain were reported in previous studies.50–52 Our studies also showed relatively lower HI antibody titers in B strain (Table 2). However, the beneficial effects of prebiotic/probiotic supplementation were observed in all A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and B strains. A 20% (A/H1N1), 19.5% (A/H3N2), and 13.6% (B strain) increase in HI antibody titers was observed in individuals with prebiotics/probiotics use.

Consumption of “good bacteria” could suppress the growth of pathogenic bacteria in the gastrointestinal tract and improve the intestinal barrier function.6,7 The use of prebiotics/probiotics in patients with bacterial diarrhea is well known.8,53–55 Probiotics are also used to prevent necrotizing enterocolitis and sepsis in preterm neonates and may also contribute to adjuvant therapy in eradication of Helicobacter pylori.54,56–60 In addition to the beneficial effects in the gastrointestinal tract, systemic immunomodulatory effects, toll-like receptor-mediated pathways, regulatory T cell induction, natural killer cells, soluble proteins, and various cytokines were involved in the probiotic immune regulatory mechanism.5,9–12,61 Therefore, manipulation of the gut microbiota may benefit patients with systemic diseases, such as allergic diseases.14 Reduced risks of subsequent cardiovascular diseases and metabolic outcomes were also observed.15,62 In a report published in 2016, it was stated that probiotic-modulated gut microbiota may suppress hepatocellular carcinoma growth in mice via regulation of T cell and pro-inflammatory cytokines.13 The use of prebiotics/probiotics/synbiotics may hold great promise for preventing and treating many extraintestinal diseases.

Probiotics are “live” bacteria, which help human to fight against pathogenic bacteria. Although the benefits of probiotics in preterm neonates are well documented, safety of probiotics in immunocompromised individuals remains a major concern.56–58 Bacteremia caused by probiotics strains was reported in some immunocompromised patients.63–66 Elderly people are at increased risk of being immunocompromised and the issue of safety remains important. In our meta-analysis studies, more than half of the participants were bedridden, fed with nasogastric tubes, or nursing home residents; no documented probiotics-related sepsis was reported.26–28,30,31,34,35 Furthermore, in the subgroup analysis of our study, prebiotics were also beneficial for enhancing immune responses after influenza vaccination. Prebiotic use may be a reasonable choice for immunocompromised patients at increased risk for infection.

Our study had some limitations. First, the study design, study participants, and study period were highly heterogeneous. Further large-scale studies are warranted to confirm our findings. Second, the strain, doses, and the duration of prebiotics/probiotics supplementation differed among studies. The immune responses may vary in different supplement protocol. Further studies are required to investigate the optimal strain, dosage, and duration of probiotic consumption. Finally, the components of the influenza vaccine and prevalent influenza strains were different each year. It may be more valuable to explore the effects of probiotics with the same influenza vaccine.

Conclusion

Our study suggests that concomitant prebiotics/probiotics use might be an effective intervention to enhance the HI antibody titer following influenza vaccination (13.6%–20% increases in HI antibody titers). Adjuvant prebiotics/probiotics use may hold great promise for the improvement of immune responses following influenza vaccination. However, high heterogeneity was observed and further studies are warranted to elucidate the effectiveness and decide the optimal strains, dose, timing, and duration of supplementation.

Supplementary materials

Funnel plot of strain A/H1N1.

Abbreviations: MD, mean difference; SE, standard error.

Funnel plot of strain A/H3N2.

Abbreviations: MD, mean difference; SE, standard error.

Funnel plot of strain B.

Abbreviations: MD, mean difference; SE, standard error.

Table S1.

Quality assessment of each included studya

| Study validity domains | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel and outcome assessors | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting | Other sources of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotics | ||||||

| Olivares1 | Low | Unclearb | Unclearb | Low | Low | Low |

| French and Penny2 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Uncertainf |

| Boge et al (pilot)3 | Low | Low | Low | Highd | Low | Uncertainf |

| Boge et al (confirmed)3 | Low | Low | Low | Highd | Low | Uncertainf |

| Namba et al4 | Low | Unclearb | Unclearb | Highd | Low | Uncertainf |

| Davidson et al5 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Van Puyenbroeck6 | Low | Low | Low | Highd | Highe | Uncertainf |

| Rizzardini7 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Uncertainf |

| Bosch8 | Unclearb | Unclearb | Low | Highd | Low | Highg |

| Akatsu et al9,a (letter) | Unclearb | Unclearb | Highc | Low | Uncertainb | Uncertainf |

| Akatsu et al10,b (paper) | Low | Unclearb | Unclearb | Low | Low | Uncertainf |

| Jespersen11 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Highe | Uncertainf |

| Maruyama et al12 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Prebiotics | ||||||

| Bunout13 | Low | Unclearb | Low | Highd | Low | Uncertainf |

| Langkamp-Henken et al14 | Low | Low | Unclearb | Highd | Low | Uncertainf |

| Langkamp-Henken et al15 | Unclearb | Low | Low | Highd | Low | Highg |

| Nagafuchi et al16 | Unclearb | Unclearb | Highc | Low | Low | Uncertainf |

| Lomax et al17 | Unclearb | Low | Unclearb | Highd | Highe | Uncertainf |

| Akatsu et al18 | Unclearb | Unclearb | Highc | Low | Low | Uncertainf |

| Synbiotics | ||||||

| Enami19 | Unclearb | Low | Low | Highd | Unclear | Unclearf |

Notes:

Each domain has been evaluated as being “High”, “Low”, or “Unclear” regarding the risk of bias following the guidelines of Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias. “Low” in all domains would place a study at “Low Risk of Bias”; “High” in any of the domains would place a study at “High Risk of Bias”; “Unclear” in any of the domains would place the study at “Unclear Risk of Bias”.

Not mentioned.

Un-blinded, open-labeled.

Drop-off rate >10%.

Missing data/data lost.

Conflict of interest, financial supports.

Authors employed by funding companies.

Box S1. Detailed search strategy of systematic review.

| PubMed |

| ((((Flu Vaccine* OR Afluria OR Influenza Vaccine* OR Afluria OR Influenzavirus Vaccine* OR LAIV vaccine OR FluMist OR CAIV-T vaccine OR Trivalent Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine OR Influenza Virus Vaccine*)) OR ((((Influenza, Human) OR (lnfluenza* OR flu)))in All Fields |

| AND |

| ((Vaccination) OR vaccine*)))) in All Fields |

| AND |

| ((((((((Probiotics) OR Bifidobacterium longum) OR Lactobacillus rhamnosus) OR (Lactic acid bacteria OR Lactobacillus acidophilus OR Lactobacillus amylovorus OR Lactobacillus Streptococcus faecalis OR L. acidophilus OR B. lactis OR Bifidobacterium OR B. bifidum OR B. longum OR Bifidobacter* OR Lactobacillus casei OR Lactobacillus paracasei OR Lactobacillus rhamnosus OR Lactobacillus GG OR Culturelle)) OR probiotic*)) OR ((Prebiotics) OR ((Prebiotic* OR Oligosaccharid*)))) OR ((Synbiotics) OR Synbiotic*)) in All Fields |

| Embase |

| Influenza Vaccines OR Flu Vaccine* OR Afluria OR Influenza Vaccines OR Flu Vaccine* OR Afluria OR Influenzavirus Vaccine* OR LAIV vaccine OR FluMist OR CAIV-T vaccine OR Trivalent Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine OR Influenza Virus Vaccine* |

| AND |

| Vaccination OR vaccine* |

| AND |

| ((((((((Probiotics) OR Bifidobacterium longum) OR Lactobacillus rhamnosus) OR (Lactic acid bacteria OR Lactobacillus acidophilus OR Lactobacillus amylovorus OR Lactobacillus Streptococcus faecalis OR L. acidophilus OR B. lactis OR Bifidobacterium OR B. bifidum OR B. longum OR Bifidobacter* OR Lactobacillus casei OR Lactobacillus paracasei OR Lactobacillus rhamnosus OR Lactobacillus GG OR Culturelle)) OR probiotic*)) OR ((Prebiotics) OR ((Prebiotic* OR Oligosaccharid*)))) OR ((Synbiotics) OR Synbiotic*)) |

| Cochrane |

| Influenza Vaccines OR Flu Vaccine* OR Afluria OR Influenza Vaccines OR Flu Vaccine* OR Afluria OR Influenzavirus Vaccine* OR LAIV vaccine OR FluMist OR CAIV-T vaccine OR Trivalent Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine OR Influenza Virus Vaccine* |

| AND |

| Vaccination OR vaccine* |

| AND |

| ((((((((Probiotics) OR Bifidobacterium longum) OR Lactobacillus rhamnosus) OR (Lactic acid bacteria OR Lactobacillus acidophilus OR Lactobacillus amylovorus OR Lactobacillus Streptococcus faecalis OR L. acidophilus OR B. lactis OR Bifidobacterium OR B. bifidum OR B. longum OR Bifidobacter* OR Lactobacillus casei OR Lactobacillus paracasei OR Lactobacillus rhamnosus OR Lactobacillus GG OR Culturelle)) OR probiotic*)) OR ((Prebiotics) OR ((Prebiotic* OR Oligosaccharid*)))) OR ((Synbiotics) OR Synbiotic*)) |

| CINAHL |

| ((((Flu Vaccine* OR Afluria OR Influenza Vaccine* OR Afluria OR Influenzavirus Vaccine* OR LAIV vaccine OR FluMist OR CAIV-T vaccine OR Trivalent Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine OR Influenza Virus Vaccine*)) OR ((((Influenza, Human) OR (lnfluenza* OR flu))) |

| AND |

| ((Vaccination) OR vaccine*)))) |

| AND |

| ((((((((Probiotics) OR Bifidobacterium longum) OR Lactobacillus rhamnosus) OR (Lactic acid bacteria OR Lactobacillus acidophilus OR Lactobacillus amylovorus OR Lactobacillus Streptococcus faecalis OR L. acidophilus OR B. lactis OR Bifidobacterium OR B. bifidum OR B. longum OR Bifidobacter* OR Lactobacillus casei OR Lactobacillus paracasei OR Lactobacillus rhamnosus OR Lactobacillus GG OR Culturelle)) OR probiotic*)) OR ((Prebiotics) OR ((Prebiotic* OR Oligosaccharid*)))) OR ((Synbiotics) OR Synbiotic*)) |

| Airiti |

| 流感 OR 流行性感冒 OR 感冒 |

| AND |

| 疫苗 |

| AND |

| 益生菌 OR 乳酸菌 OR 龍根菌 OR 益菌生 OR 益生源 OR 合生元 OR 共生質 OR 合益菌 |

| NTLTD |

| 流感 + 流行性感冒 + 感冒 |

| AND |

| 疫苗 |

| AND |

| 益生菌 + 乳酸菌 + 龍根菌 + 益菌生 + 益生源 + 合生元 + 共生質 + 合益菌 |

Abbreviations: CAIV-T, cold-adapted influenza vaccine, trivalent; CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health; LAIV, live attenuated influenza vaccine; NTLTD, Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations.

References

- 1.Olivares M, Diaz-Ropero MP, Sierra S, et al. Oral intake of Lactobacillus fermentum CECT5716 enhances the effects of influenza vaccination. Nutrition. 2007;23(3):254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.French PW, Penny R. Use of probiotic bacteria as an adjuvant for an influenza vaccine. Int J Probiotics Prebiotics. 2009;4(3):175–182. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boge T, Remigy M, Vaudaine S, Tanguy J, Bourdet-Sicard R, van der Werf S. A probiotic fermented dairy drink improves antibody response to influenza vaccination in the elderly in two randomised controlled trials. Vaccine. 2009;27(41):5677–5684. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.06.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Namba K, Hatano M, Yaeshima T, Takase M, Suzuki K. Effects of Bifidobacterium longum BB536 administration on influenza infection, influenza vaccine antibody titer, and cell-mediated immunity in the elderly. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2010;74(5):939–945. doi: 10.1271/bbb.90749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davidson LE, Fiorino AM, Snydman DR, Hibberd PL. Lactobacillus GG as an immune adjuvant for live-attenuated influenza vaccine in healthy adults: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(4):501–507. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Puyenbroeck K, Hens N, Coenen S, et al. Efficacy of daily intake of Lactobacillus casei Shirota on respiratory symptoms and influenza vaccination immune response: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in healthy elderly nursing home residents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(5):1165–1171. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.026831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rizzardini G, Eskesen D, Calder PC, Capetti A, Jespersen L, Clerici M. Evaluation of the immune benefits of two probiotic strains Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis, BB-12® and Lactobacillus paracasei ssp. paracasei, L. casei 431® in an influenza vaccination model: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Nutr. 2012;107(6):876–884. doi: 10.1017/S000711451100420X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bosch M, Méndez M, Pérez M, Farran A, Fuentes MC, Cuñé J. Lactobacillus plantarum CECT7315 and CECT7316 stimulate immunoglobulin production after influenza vaccination in elderly. Nutr Hosp. 2012;27(2):504–509. doi: 10.1590/S0212-16112012000200023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akatsu H, Arakawa K, Yamamoto T, et al. Lactobacillus in jelly enhances the effect of influenza vaccination in elderly individuals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(10):1828–1830. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Akatsu H, Iwabuchi N, Xiao JZ, et al. Clinical effects of probiotic Bifidobacterium longum BB536 on immune function and intestinal microbiota in elderly patients receiving enteral tube feeding. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2013;37(5):631–640. doi: 10.1177/0148607112467819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jespersen L, Tarnow I, Eskesen D, et al. Effect of Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei, L. casei 431 on immune response to influenza vaccination and upper respiratory tract infections in healthy adult volunteers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(6):1188–1196. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.103531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maruyama M, Abe R, Shimono T, Iwabuchi N, Abe F, Xiao JZ. The effects of non-viable Lactobacillus on immune function in the elderly: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2016;67(1):67–73. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2015.1126564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunout D, Hirsch S, Pía de la Maza M, et al. Effects of prebiotics on the immune response to vaccination in the elderly. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002;26(6):372–376. doi: 10.1177/0148607102026006372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Langkamp-Henken B, Bender BS, Gardner EM, et al. Nutritional formula enhanced immune function and reduced days of symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection in seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(1):3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Langkamp-Henken B, Wood SM, Herlinger-Garcia KA, et al. Nutritional formula improved immune profiles of seniors living in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(12):1861–1870. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nagafuchi S, Yamaji T, Kawashima A, et al. Effects of a formula containing two types of prebiotics, bifidogenic growth stimulator and galactooligosaccharide, and fermented milk products on intestinal microbiota and antibody response to influenza vaccine in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2015;8(2):351–365. doi: 10.3390/ph8020351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lomax AR, Cheung LV, Noakes PS, Miles EA, Calder PC. Inulin-type beta2–1 fructans have some effect on the antibody response to seasonal influenza vaccination in healthy middle-aged humans. Front Immunol. 2015;6:490. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Akatsu H, Nagafuchi S, Kurihara R, et al. Enhanced vaccination effect against influenza by prebiotics in elderly patients receiving enteral nutrition. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16(2):205–213. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Enani S, Przemska-Kosicka A, Childs CE, et al. Impact of ageing and a synbiotic on the immune response to seasonal influenza vaccination; a randomised controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2017 Jan 28; doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.01.011. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Acknowledgments

Our manuscript has been edited for English language, grammar, punctuation, and spelling by Enago, the editing brand of Crimson Interactive Pvt, Ltd.

Footnotes

Author contributions

All authors contributed toward data analysis, drafting and critically revising the paper, gave final approval of the version to be published, and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure

The authors report no conflicts of interest in this work.

References

- 1.Jordan RE, Hawker JI. Influenza in elderly people in care homes. BMJ. 2006;333(7581):1229–1230. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39050.408044.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Osterholm MT, Kelley NS, Sommer A, Belongia EA. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2012;12(1):36–44. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(11)70295-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.DiazGranados CA, Dunning AJ, Kimmel M, et al. Efficacy of high-dose versus standard-dose influenza vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 2014;371(7):635–645. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1315727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pae M, Meydani SN, Wu D. The role of nutrition in enhancing immunity in aging. Aging Dis. 2012;3(1):91–129. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yan F, Cao H, Cover TL, Whitehead R, Washington MK, Polk DB. Soluble proteins produced by probiotic bacteria regulate intestinal epithelial cell survival and growth. Gastroenterology. 2007;132(2):562–575. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Markowiak P, Śliżewska K. Effects of probiotics, prebiotics, and synbiotics on human health. Nutrients. 2017;9(9):E1021. doi: 10.3390/nu9091021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jones SE, Versalovic J. Probiotic Lactobacillus reuteri biofilms produce antimicrobial and anti-inflammatory factors. BMC Microbiol. 2009;9:35. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-9-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hojsak I, Szajewska H, Canani RB, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of nosocomial diarrhea in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2018;66(1):3–9. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Oshima K, et al. Treg induction by a rationally selected mixture of Clostridia strains from the human microbiota. Nature. 2013;500(7461):232–236. doi: 10.1038/nature12331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Round JL, Lee SM, Li J, et al. The Toll-like receptor 2 pathway establishes colonization by a commensal of the human microbiota. Science. 2011;332(6032):974–977. doi: 10.1126/science.1206095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pathmakanthan S, Li CK, Cowie J, Hawkey CJ. Lactobacillus plantarum 299: beneficial in vitro immunomodulation in cells extracted from inflamed human colon. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;19(2):166–173. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2004.03181.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee A, Lee YJ, Yoo HJ, et al. Consumption of dairy yogurt containing Lactobacillus paracasei ssp. paracasei, Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis and heat-treated Lactobacillus plantarum improves immune function including natural killer cell activity. Nutrients. 2017;9(6):E558. doi: 10.3390/nu9060558. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li J, Sung CY, Lee N, et al. Probiotics modulated gut microbiota suppresses hepatocellular carcinoma growth in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(9):E1306–E1315. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1518189113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chang YS, Trivedi MK, Jha A, Lin YF, Dimaano L, Garcia-Romero MT. Synbiotics for prevention and treatment of atopic dermatitis: a meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Pediatr. 2016;170(3):236–242. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu L, Sun D. Consumption of yogurt and the incident risk of cardiovascular disease: a meta-analysis of nine cohort studies. Nutrients. 2017;9(3):E315. doi: 10.3390/nu9030315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Praharaj I, John SM, Bandyopadhyay R, Kang G. Probiotics, antibiotics and the immune responses to vaccines. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci. 2015;370(1671):20140144. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2014.0144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Maidens C, Childs C, Przemska A, Dayel IB, Yaqoob P. Modulation of vaccine response by concomitant probiotic administration. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 2013;75(3):663–670. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.2012.04404.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Licciardi PV, Tang ML. Vaccine adjuvant properties of probiotic bacteria. Discov Med. 2011;12(67):525–533. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zimmermann P, Curtis N. The influence of probiotics on vaccine responses – a systematic review. Vaccine. 2018;36(2):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.08.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lei WT, Shih PC, Liu SJ, Lin CY, Yeh TL. Effect of probiotics and prebiotics on immune response to influenza vaccination in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. 2017;9(11):E1175. doi: 10.3390/nu9111175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liberati A, Altman DG, Tetzlaff J, et al. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. BMJ. 2009;339:b2700. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.de Jong JC, Palache AM, Beyer WE, Rimmelzwaan GF, Boon AC, Osterhaus AD. Haemagglutination-inhibiting antibody to influenza virus. Dev Biol (Basel) 2003;115:63–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Higgins JP, Thompson SG. Quantifying heterogeneity in a meta-analysis. Stat Med. 2002;21(11):1539–1558. doi: 10.1002/sim.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003;327(7414):557–560. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Egger M, Davey Smith G, Schneider M, Minder C. Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ. 1997;315(7109):629–634. doi: 10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maruyama M, Abe R, Shimono T, Iwabuchi N, Abe F, Xiao JZ. The effects of non-viable Lactobacillus on immune function in the elderly: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Int J Food Sci Nutr. 2016;67(1):67–73. doi: 10.3109/09637486.2015.1126564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Akatsu H, Nagafuchi S, Kurihara R, et al. Enhanced vaccination effect against influenza by prebiotics in elderly patients receiving enteral nutrition. Geriatr Gerontol Int. 2016;16(2):205–213. doi: 10.1111/ggi.12454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nagafuchi S, Yamaji T, Kawashima A, et al. Effects of a formula containing two types of prebiotics, bifidogenic growth stimulator and galactooligosaccharide, and fermented milk products on intestinal microbiota and antibody response to influenza vaccine in elderly patients: a randomized controlled trial. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2015;8(2):351–365. doi: 10.3390/ph8020351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lomax AR, Cheung LV, Noakes PS, Miles EA, Calder PC. Inulin-type beta2–1 fructans have some effect on the antibody response to seasonal influenza vaccination in healthy middle-aged humans. Front Immunol. 2015;6:490. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Akatsu H, Iwabuchi N, Xiao JZ, et al. Clinical effects of probiotic Bifidobacterium longum BB536 on immune function and intestinal microbiota in elderly patients receiving enteral tube feeding. JPEN J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2013;37(5):631–640. doi: 10.1177/0148607112467819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Akatsu H, Arakawa K, Yamamoto T, et al. Lactobacillus in jelly enhances the effect of influenza vaccination in elderly individuals. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(10):1828–1830. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Davidson LE, Fiorino AM, Snydman DR, Hibberd PL. Lactobacillus GG as an immune adjuvant for live-attenuated influenza vaccine in healthy adults: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2011;65(4):501–507. doi: 10.1038/ejcn.2010.289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Namba K, Hatano M, Yaeshima T, Takase M, Suzuki K. Effects of Bifidobacterium longum BB536 administration on influenza infection, influenza vaccine antibody titer, and cell-mediated immunity in the elderly. Biosci Biotechnol Biochem. 2010;74(5):939–945. doi: 10.1271/bbb.90749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boge T, Remigy M, Vaudaine S, Tanguy J, Bourdet-Sicard R, van der Werf S. A probiotic fermented dairy drink improves antibody response to influenza vaccination in the elderly in two randomised controlled trials. Vaccine. 2009;27(41):5677–5684. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2009.06.094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Langkamp-Henken B, Wood SM, Herlinger-Garcia KA, et al. Nutritional formula improved immune profiles of seniors living in nursing homes. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2006;54(12):1861–1870. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2006.00982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Langkamp-Henken B, Bender BS, Gardner EM, et al. Nutritional formula enhanced immune function and reduced days of symptoms of upper respiratory tract infection in seniors. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52(1):3–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Enani S, Przemska-Kosicka A, Childs CE, et al. Impact of ageing and a synbiotic on the immune response to seasonal influenza vaccination; a randomised controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2017 Jan 28; doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2017.01.011. Epub. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Manzoli L, Ioannidis JP, Flacco ME, De Vito C, Villari P. Effectiveness and harms of seasonal and pandemic influenza vaccines in children, adults and elderly: a critical review and re-analysis of 15 meta-analyses. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2012;8(7):851–862. doi: 10.4161/hv.19917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nicoll A, Sprenger M. Low effectiveness undermines promotion of seasonal influenza vaccine. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13(1):7–9. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70313-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Puig-Barbera J, Mira-Iglesias A, Tortajada-Girbes M, et al. Waning protection of influenza vaccination during four influenza seasons, 2011/2012 to 2014/2015. Vaccine. 2017;35(43):5799–5807. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2017.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bellei NC, Carraro E, Castelo A, Granato CF. Risk factors for poor immune response to influenza vaccination in elderly people. Braz J Infect Dis. 2006;10(4):269–273. doi: 10.1590/s1413-86702006000400011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jefferson T, Rivetti D, Rivetti A, Rudin M, Di Pietrantonj C, Demicheli V. Efficacy and effectiveness of influenza vaccines in elderly people: a systematic review. Lancet. 2005;366(9492):1165–1174. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)67339-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haq K, McElhaney JE. Immunosenescence: influenza vaccination and the elderly. Curr Opin Immunol. 2014;29:38–42. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2014.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chen WH, Kozlovsky BF, Effros RB, Grubeck-Loebenstein B, Edelman R, Sztein MB. Vaccination in the elderly: an immunological perspective. Trends Immunol. 2009;30(7):351–359. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Brydak LB, Machala M, Mysliwska J, Mysliwski A, Trzonkowski P. Immune response to influenza vaccination in an elderly population. J Clin Immunol. 2003;23(3):214–222. doi: 10.1023/a:1023314029788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yaqoob P. Ageing, immunity and influenza: a role for probiotics? Proc Nutr Soc. 2014;73(2):309–317. doi: 10.1017/S0029665113003777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Youngster I, Kozer E, Lazarovitch Z, Broide E, Goldman M. Probiotics and the immunological response to infant vaccinations: a prospective, placebo controlled pilot study. Arch Dis Child. 2011;96(4):345–349. doi: 10.1136/adc.2010.197459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hao Q, Dong BR, Wu T. Probiotics for preventing acute upper respiratory tract infections. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015;2:CD006895. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006895.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leyer GJ, Li S, Mubasher ME, Reifer C, Ouwehand AC. Probiotic effects on cold and influenza-like symptom incidence and duration in children. Pediatrics. 2009;124(2):e172–e179. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Talbot HK, Keitel W, Cate TR, et al. Immunogenicity, safety and consistency of new trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine. Vaccine. 2008;26(32):4057–4061. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Del Porto F, Lagana B, Biselli R, et al. Influenza vaccine administration in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis. Safety and immunogenicity. Vaccine. 2006;24(16):3217–3223. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2006.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Salemi S, Picchianti-Diamanti A, Germano V, et al. Influenza vaccine administration in rheumatoid arthritis patients under treatment with TNFα blockers: safety and immunogenicity. Clin Immunol. 2010;134(2):113–120. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Floch MH, Walker WA, Sanders ME, et al. Recommendations for probiotic use – 2015 update: proceedings and consensus opinion. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2015;49(Suppl 1):S69–S73. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000000420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Vandenplas Y, Veereman-Wauters G, De Greef E, et al. Probiotics and prebiotics in prevention and treatment of diseases in infants and children. J Pediatr. 2011;87(4):292–300. doi: 10.2223/JPED.2103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Szajewska H, Canani RB, Guarino A, et al. Probiotics for the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea in children. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2016;62(3):495–506. doi: 10.1097/MPG.0000000000001081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Pammi M, Suresh G. Enteral lactoferrin supplementation for prevention of sepsis and necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;6:CD007137. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007137.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hu HJ, Zhang GQ, Zhang Q, Shakya S, Li ZY. Probiotics prevent candida colonization and invasive fungal sepsis in preterm neonates: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Pediatr Neonatol. 2017;58(2):103–110. doi: 10.1016/j.pedneo.2016.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rao SC, Athalye-Jape GK, Deshpande GC, Simmer KN, Patole SK. Probiotic supplementation and late-onset sepsis in preterm infants: a meta-analysis. Pediatrics. 2016;137(3):e20153684. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aceti A, Maggio L, Beghetti I, et al. Probiotics prevent late-onset sepsis in human milk-fed, very low birth weight preterm infants: systematic review and meta-analysis. Nutrients. 2017;9(8):E904. doi: 10.3390/nu9080904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Aceti A, Gori D, Barone G, et al. Probiotics for prevention of necrotizing enterocolitis in preterm infants: systematic review and meta-analysis. Ital J Pediatr. 2015;41:89. doi: 10.1186/s13052-015-0199-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.McCarthy J, O’Mahony L, O’Callaghan L, et al. Double blind, placebo controlled trial of two probiotic strains in interleukin 10 knockout mice and mechanistic link with cytokine balance. Gut. 2003;52(7):975–980. doi: 10.1136/gut.52.7.975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Taylor B, Woodfall G, Sheedy K, et al. Effect of probiotics on metabolic outcomes in pregnant women with gestational diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Nutrients. 2017;9(5):E461. doi: 10.3390/nu9050461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Esaiassen E, Hjerde E, Cavanagh JP, Simonsen GS, Klingenberg C. Bifidobacterium bacteremia: clinical characteristics and a genomic approach to assess pathogenicity. J Clin Microbiol. 2017;55(7):2234–2248. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00150-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sherid M, Samo S, Sulaiman S, Husein H, Sifuentes H, Sridhar S. Liver abscess and bacteremia caused by lactobacillus: role of probiotics? Case report and review of the literature. BMC Gastroenterol. 2016;16(1):138. doi: 10.1186/s12876-016-0552-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cohen SA, Woodfield MC, Boyle N, Stednick Z, Boeckh M, Pergam SA. Incidence and outcomes of bloodstream infections among hematopoietic cell transplant recipients from species commonly reported to be in over-the-counter probiotic formulations. Transpl Infect Dis. 2016;18(5):699–705. doi: 10.1111/tid.12587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Meini S, Laureano R, Fani L, et al. Breakthrough Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG bacteremia associated with probiotic use in an adult patient with severe active ulcerative colitis: case report and review of the literature. Infection. 2015;43(6):777–781. doi: 10.1007/s15010-015-0798-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Olivares M, Diaz-Ropero MP, Sierra S, et al. Oral intake of Lactobacillus fermentum CECT5716 enhances the effects of influenza vaccination. Nutrition. 2007;23(3):254–260. doi: 10.1016/j.nut.2007.01.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.French PW, Penny R. Use of probiotic bacteria as an adjuvant for an influenza vaccine. Int J Probiotics Prebiotics. 2009;4(3):175–182. [Google Scholar]

- 69.Van Puyenbroeck K, Hens N, Coenen S, et al. Efficacy of daily intake of Lactobacillus casei Shirota on respiratory symptoms and influenza vaccination immune response: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in healthy elderly nursing home residents. Am J Clin Nutr. 2012;95(5):1165–1171. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.111.026831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Rizzardini G, Eskesen D, Calder PC, Capetti A, Jespersen L, Clerici M. Evaluation of the immune benefits of two probiotic strains Bifidobacterium animalis ssp. lactis, BB-12® and Lactobacillus paracasei ssp. paracasei, L. casei 431® in an influenza vaccination model: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Br J Nutr. 2012;107(6):876–884. doi: 10.1017/S000711451100420X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bosch M, Méndez M, Pérez M, Farran A, Fuentes MC, Cuñé J. Lactobacillus plantarum CECT7315 and CECT7316 stimulate immunoglobulin production after influenza vaccination in elderly. Nutr Hosp. 2012;27(2):504–509. doi: 10.1590/S0212-16112012000200023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Jespersen L, Tarnow I, Eskesen D, et al. Effect of Lactobacillus paracasei subsp. paracasei, L. casei 431 on immune response to influenza vaccination and upper respiratory tract infections in healthy adult volunteers: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;101(6):1188–1196. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.114.103531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Bunout D, Hirsch S, Pía de la Maza M, et al. Effects of prebiotics on the immune response to vaccination in the elderly. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2002;26(6):372–376. doi: 10.1177/0148607102026006372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Funnel plot of strain A/H1N1.

Abbreviations: MD, mean difference; SE, standard error.

Funnel plot of strain A/H3N2.

Abbreviations: MD, mean difference; SE, standard error.

Funnel plot of strain B.

Abbreviations: MD, mean difference; SE, standard error.

Table S1.

Quality assessment of each included studya

| Study validity domains | Sequence generation | Allocation concealment | Blinding of participants and personnel and outcome assessors | Incomplete outcome data | Selective outcome reporting | Other sources of bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Probiotics | ||||||

| Olivares1 | Low | Unclearb | Unclearb | Low | Low | Low |

| French and Penny2 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Uncertainf |

| Boge et al (pilot)3 | Low | Low | Low | Highd | Low | Uncertainf |

| Boge et al (confirmed)3 | Low | Low | Low | Highd | Low | Uncertainf |

| Namba et al4 | Low | Unclearb | Unclearb | Highd | Low | Uncertainf |

| Davidson et al5 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Van Puyenbroeck6 | Low | Low | Low | Highd | Highe | Uncertainf |

| Rizzardini7 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Uncertainf |

| Bosch8 | Unclearb | Unclearb | Low | Highd | Low | Highg |

| Akatsu et al9,a (letter) | Unclearb | Unclearb | Highc | Low | Uncertainb | Uncertainf |

| Akatsu et al10,b (paper) | Low | Unclearb | Unclearb | Low | Low | Uncertainf |

| Jespersen11 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Highe | Uncertainf |

| Maruyama et al12 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low |

| Prebiotics | ||||||

| Bunout13 | Low | Unclearb | Low | Highd | Low | Uncertainf |

| Langkamp-Henken et al14 | Low | Low | Unclearb | Highd | Low | Uncertainf |

| Langkamp-Henken et al15 | Unclearb | Low | Low | Highd | Low | Highg |

| Nagafuchi et al16 | Unclearb | Unclearb | Highc | Low | Low | Uncertainf |

| Lomax et al17 | Unclearb | Low | Unclearb | Highd | Highe | Uncertainf |

| Akatsu et al18 | Unclearb | Unclearb | Highc | Low | Low | Uncertainf |

| Synbiotics | ||||||

| Enami19 | Unclearb | Low | Low | Highd | Unclear | Unclearf |

Notes:

Each domain has been evaluated as being “High”, “Low”, or “Unclear” regarding the risk of bias following the guidelines of Cochrane Collaboration’s tool for assessing risk of bias. “Low” in all domains would place a study at “Low Risk of Bias”; “High” in any of the domains would place a study at “High Risk of Bias”; “Unclear” in any of the domains would place the study at “Unclear Risk of Bias”.

Not mentioned.

Un-blinded, open-labeled.

Drop-off rate >10%.

Missing data/data lost.

Conflict of interest, financial supports.

Authors employed by funding companies.

Box S1. Detailed search strategy of systematic review.

| PubMed |

| ((((Flu Vaccine* OR Afluria OR Influenza Vaccine* OR Afluria OR Influenzavirus Vaccine* OR LAIV vaccine OR FluMist OR CAIV-T vaccine OR Trivalent Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine OR Influenza Virus Vaccine*)) OR ((((Influenza, Human) OR (lnfluenza* OR flu)))in All Fields |

| AND |

| ((Vaccination) OR vaccine*)))) in All Fields |

| AND |

| ((((((((Probiotics) OR Bifidobacterium longum) OR Lactobacillus rhamnosus) OR (Lactic acid bacteria OR Lactobacillus acidophilus OR Lactobacillus amylovorus OR Lactobacillus Streptococcus faecalis OR L. acidophilus OR B. lactis OR Bifidobacterium OR B. bifidum OR B. longum OR Bifidobacter* OR Lactobacillus casei OR Lactobacillus paracasei OR Lactobacillus rhamnosus OR Lactobacillus GG OR Culturelle)) OR probiotic*)) OR ((Prebiotics) OR ((Prebiotic* OR Oligosaccharid*)))) OR ((Synbiotics) OR Synbiotic*)) in All Fields |

| Embase |

| Influenza Vaccines OR Flu Vaccine* OR Afluria OR Influenza Vaccines OR Flu Vaccine* OR Afluria OR Influenzavirus Vaccine* OR LAIV vaccine OR FluMist OR CAIV-T vaccine OR Trivalent Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine OR Influenza Virus Vaccine* |

| AND |

| Vaccination OR vaccine* |

| AND |

| ((((((((Probiotics) OR Bifidobacterium longum) OR Lactobacillus rhamnosus) OR (Lactic acid bacteria OR Lactobacillus acidophilus OR Lactobacillus amylovorus OR Lactobacillus Streptococcus faecalis OR L. acidophilus OR B. lactis OR Bifidobacterium OR B. bifidum OR B. longum OR Bifidobacter* OR Lactobacillus casei OR Lactobacillus paracasei OR Lactobacillus rhamnosus OR Lactobacillus GG OR Culturelle)) OR probiotic*)) OR ((Prebiotics) OR ((Prebiotic* OR Oligosaccharid*)))) OR ((Synbiotics) OR Synbiotic*)) |

| Cochrane |

| Influenza Vaccines OR Flu Vaccine* OR Afluria OR Influenza Vaccines OR Flu Vaccine* OR Afluria OR Influenzavirus Vaccine* OR LAIV vaccine OR FluMist OR CAIV-T vaccine OR Trivalent Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine OR Influenza Virus Vaccine* |

| AND |

| Vaccination OR vaccine* |

| AND |

| ((((((((Probiotics) OR Bifidobacterium longum) OR Lactobacillus rhamnosus) OR (Lactic acid bacteria OR Lactobacillus acidophilus OR Lactobacillus amylovorus OR Lactobacillus Streptococcus faecalis OR L. acidophilus OR B. lactis OR Bifidobacterium OR B. bifidum OR B. longum OR Bifidobacter* OR Lactobacillus casei OR Lactobacillus paracasei OR Lactobacillus rhamnosus OR Lactobacillus GG OR Culturelle)) OR probiotic*)) OR ((Prebiotics) OR ((Prebiotic* OR Oligosaccharid*)))) OR ((Synbiotics) OR Synbiotic*)) |

| CINAHL |

| ((((Flu Vaccine* OR Afluria OR Influenza Vaccine* OR Afluria OR Influenzavirus Vaccine* OR LAIV vaccine OR FluMist OR CAIV-T vaccine OR Trivalent Live Attenuated Influenza Vaccine OR Influenza Virus Vaccine*)) OR ((((Influenza, Human) OR (lnfluenza* OR flu))) |

| AND |

| ((Vaccination) OR vaccine*)))) |

| AND |

| ((((((((Probiotics) OR Bifidobacterium longum) OR Lactobacillus rhamnosus) OR (Lactic acid bacteria OR Lactobacillus acidophilus OR Lactobacillus amylovorus OR Lactobacillus Streptococcus faecalis OR L. acidophilus OR B. lactis OR Bifidobacterium OR B. bifidum OR B. longum OR Bifidobacter* OR Lactobacillus casei OR Lactobacillus paracasei OR Lactobacillus rhamnosus OR Lactobacillus GG OR Culturelle)) OR probiotic*)) OR ((Prebiotics) OR ((Prebiotic* OR Oligosaccharid*)))) OR ((Synbiotics) OR Synbiotic*)) |

| Airiti |

| 流感 OR 流行性感冒 OR 感冒 |

| AND |

| 疫苗 |

| AND |

| 益生菌 OR 乳酸菌 OR 龍根菌 OR 益菌生 OR 益生源 OR 合生元 OR 共生質 OR 合益菌 |

| NTLTD |

| 流感 + 流行性感冒 + 感冒 |

| AND |

| 疫苗 |

| AND |

| 益生菌 + 乳酸菌 + 龍根菌 + 益菌生 + 益生源 + 合生元 + 共生質 + 合益菌 |

Abbreviations: CAIV-T, cold-adapted influenza vaccine, trivalent; CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health; LAIV, live attenuated influenza vaccine; NTLTD, Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations.