Abstract

Although it is now widely accepted that the rate of phenotypic evolution may not necessarily be constant across large phylogenies, the frequency and phylogenetic position of periods of rapid evolution remain unclear. In his highly influential view of evolution, G. G. Simpson supposed that such evolutionary jumps occur when organisms transition into so-called new adaptive zones, for instance after dispersal into a new geographic area, after rapid climatic changes, or following the appearance of an evolutionary novelty. Only recently, large, accurate and well calibrated phylogenies have become available that allow testing this hypothesis directly, yet inferring evolutionary jumps remains computationally very challenging. Here, we develop a computationally highly efficient algorithm to accurately infer the rate and strength of evolutionary jumps as well as their phylogenetic location. Following previous work we model evolutionary jumps as a compound process, but introduce a novel approach to sample jump configurations that does not require matrix inversions and thus naturally scales to large trees. We then make use of this development to infer evolutionary jumps in Anolis lizards and Loriinii parrots where we find strong signal for such jumps at the basis of clades that transitioned into new adaptive zones, just as postulated by Simpson’s hypothesis. [evolutionary jump; Lévy process; phenotypic evolution; punctuated equilibrium; quantitative traits.

A key goal of evolutionary biology is to understand the mechanisms by which the phenotypic diversity seen today evolved. Our understanding of these mechanisms is improving rapidly with the advent of increasingly powerful sequencing approaches. For instance, the accumulation of molecular data has led to the resolution of phylogenetic trees encompassing entire orders. Further, methods to reliably identify substitutions that likely resulted from selection, and to accurately place them on a phylogeny have been developed. In contrast, methods to infer events of rapid evolution from phenotypic data have lagged and are mostly restricted to inferring independent evolutionary rates for different clades.

In general, quantitative studies of the evolution of phenotypic/quantitative traits date back just a few decades. A first attempt was by Edwards et al. (1964) and Cavalli-Sforza and Edwards (1967), who modeled quantitative traits stochastically as “Brownian motion” (BM). However, given the current wealth of molecular data available, a more realistic goal is to only aim at inferring the rates at which quantitative traits evolve, while assuming the underlying phylogeny to be known. This has been successfully done using a BM model in multiple taxa. Freckleton et al. (2002), for instance, used a BM model on a given phylogeny to test if traits showed phylogenetic signal. More recently, Brawand et al. (2011) modeled gene expression evolution as BM and rejected evolution at a constant rate for several genes.

Several extensions to a basic BM model have been proposed. Butler and King (2004) were the first to implement Ornstein–Uhlenbeck (OU) processes with multiple evolutionary optima, as initially described by Hansen (1997), and recently used to describe the evolution of gene expression (e.g., Bedford and Hartl 2009; Rohlfs et al. 2013). Other extensions to BM allow evolutionary rates to change over time. O’Meara et al. (2006), for instance, contrasted maximum likelihood (ML) estimates of evolutionary rates under BM and showed that major clades of angiosperms vastly differ in their rate of genome size evolution. More recently, Eastman et al. (2011) developed a Bayesian method to jointly infer evolutionary rates in different clades and found evidence for multiple rate shifts in body size evolution in emydid turtles. Shortly after, Slater et al. (2012) have introduced an extension to incompletely sampled phylogenies and trait data using Approximate Bayesian Computation. However, they found no evidence for an elevated rate of body size evolution in pinnipeds in comparison to terrestrial carnivores, despite considerable power. This suggests that the larger body size found in pinnipeds may be the result of rapid evolutionary changes early in the clade, rather than a change in the rate itself, and hence that models of occasional “evolutionary jumps” may often more accurately explain the evolution of quantitative traits.

According to Simpson (1944), such evolutionary jumps are triggered by shifts of lineages into different adaptive zones, either by dispersal into new geographic areas, the appearance of evolutionary novelties, key innovations, the extinction of lineages leaving niches empty, or by rapid changes in the environment (climatic or ecological). Additionally, the existence of “ecological opportunities” (Losos 2010) might also trigger such jumps. While OU processes have been proposed to model the dynamics of adaptive landscapes (e.g., Ingram and Mahler 2013; Uyeda and Harmon 2014), a promising alternative is to model this type of evolution as a compound process (or Lévy process) consisting of a continuous background process and a discrete jump process. The first implementation of such a model assumed that jumps only occurred at speciation events (Bokma 2008), but Landis et al. (2013) recently described Lévy processes in a much more general way and showed that while the likelihood functions of most of these models are intractable, inference is possible under a Bayesian framework. For instance, when modeling the evolution of quantitative traits as a Poisson compound process, in which traits are assumed to evolve under BM with occasional jumps that occur as a Poisson process on the tree, the likelihood can be calculated analytically when conditioning on a jump configuration (a placement of jumps on the tree). Under the assumption that jump effects are normally distributed, a jump configuration can be seen as simply stretching the branches of the tree on which they occur, and the likelihood is then given by a multivariate normal distribution with the variance–covariance matrix resulting from the stretched tree. The numerical integration is then limited to sampling jump configurations, which is readily done using Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC).

Unfortunately, two computational challenges prohibit the application of this approach to larger trees. First, the space of jump configurations grows exponentially with tree size, leading to very long MCMC chains. Second, the evaluation of the likelihood requires the computation of the inverse of the variance–covariance matrix, which is computationally very demanding since it scales exponentially with tree size (Tung Ho and Ané 2014). Here, we address these computational issues using an empirical Bayes approach in which we first infer the hierarchical parameters of the Brownian and Poisson processes using ML, and then fix those when inferring posterior probabilities on jump locations. This approach allows us to run MCMC chains with fixed hierarchical parameters, for which we find a computationally highly efficient approach that does not require matrix inversions. As a result, this approach readily scales up to very large phylogenies.

We then demonstrate the power and accuracy of our approach with extensive simulations and find that our approach hardly misses any jumps with a meaningful strength. We then illustrate the usefulness of our approach by identifying evolutionary jumps in Anolis lizards and Loriini parrots, two well-studied groups for which morphological data is available. We identify few but important evolutionary jumps in both groups, suggesting such periods of rapid evolutionary change to be rare but crucial in shaping the morphological diversity observed today.

Theory

The Null Hypothesis: Brownian Motion

We first consider a Brownian motion (BM) process on a phylogenetic tree  with root

with root  where time is measured in the unit of the branch lengths. The process starts at

where time is measured in the unit of the branch lengths. The process starts at  with value

with value  (root state) and then proceeds with variance

(root state) and then proceeds with variance  along the branches. The values of the BM process, as observed at the

along the branches. The values of the BM process, as observed at the  leaves, give rise to the random vector

leaves, give rise to the random vector

Let us fix the notation: The lengths of the (inner and outer) branches of  are called

are called  where

where  is the number of branches. For two leaves

is the number of branches. For two leaves  we denote by

we denote by  the length of their common branch in

the length of their common branch in  as measured from the root

as measured from the root  . Now, under the assumption of a pure BM, and defining

. Now, under the assumption of a pure BM, and defining  , the values

, the values  at the leaves have the multivariate normal distribution

at the leaves have the multivariate normal distribution

or written more conveniently:

| (1) |

with  . Since

. Since  is positive definite and symmetric, it has a symmetric and positive definite square root

is positive definite and symmetric, it has a symmetric and positive definite square root  , i.e.,

, i.e.,  . Multiplying both sides of (1) with

. Multiplying both sides of (1) with  we get the homoskedastic model

we get the homoskedastic model

where  ,

,  , and

, and  . For this we have the usual OLS estimators (see e.g., Davidson and MacKinnon 2004, ch. 3.2)

. For this we have the usual OLS estimators (see e.g., Davidson and MacKinnon 2004, ch. 3.2)

and

Lévy Process

We now extend the BM model by super-imposing an independent Poissonian jump-process with rate  . The jumps shall be normally distributed with zero mean and variance

. The jumps shall be normally distributed with zero mean and variance  . The (unobservable) random vector

. The (unobservable) random vector

counts the number of Poisson events (jumps) on each of the  branches. By assumption,

branches. By assumption,

For a multi-index  , we have

, we have

| (2) |

Recall that for two leaves  we denote by

we denote by  the length of their common branch in

the length of their common branch in  as measured from the root

as measured from the root  . In particular,

. In particular,  is the distance (sum of branch lengths) of the leaf

is the distance (sum of branch lengths) of the leaf  from the root

from the root  .

.

We denote by  for two leaves

for two leaves  the number of Poisson events along the common branch of length

the number of Poisson events along the common branch of length  . Conditional on

. Conditional on  , the random vector

, the random vector  is multivariate normal with mean

is multivariate normal with mean  and the

and the  variance–covariance matrix

variance–covariance matrix  where

where

The conditional density of  given

given  is

is

| (3) |

The likelihood of  given the four parameters

given the four parameters  (root state),

(root state),  (Brownian motion) and

(Brownian motion) and  (Poissonian jump process) is the mixture distribution

(Poissonian jump process) is the mixture distribution

| (4) |

where we used expressions (2) and (3). It is not hard to show that

Inference under the Lévy Process

Here we develop a computationally efficient approach to maximize the likelihood function given in equation (4). Although the infinite sums in (4) prohibit an analytical solution, they are readily evaluated using numerical approaches. Landis et al. (2013), for instance, proposed to use an MCMC approach to integrate over jump configurations. Unfortunately, however, such a solution does not scale to large trees, because the calculation of the conditional density values in (3) involves the computation of the inverse of  and its determinant, which are computationally very demanding.

and its determinant, which are computationally very demanding.

We propose to address this problem by introducing an algorithm to calculate these quantities efficiently under this model. Specifically, and as we show in Appendix 1, both the inverse and determinant can be determined cheaply from a previous solution to a case that differs in the presence of a single jump on the tree. Although this algorithm can readily be incorporated into the MCMC approach proposed of Landis et al. (2013), we will propose an alternative hierarchical Bayes approach that makes even better use of it and leads to a computationally highly efficient inference approach to obtain point estimates of the parameters  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  , as well as posterior probabilities on the location of evolutionary jumps, as we describe in the following.

, as well as posterior probabilities on the location of evolutionary jumps, as we describe in the following.

Monte Carlo EM algorithm.

—We obtain ML estimates of the parameters  and

and  by means of a Monte Carlo version of the classical Expectation Maximization (EM) algorithm, in which we treat the random variable

by means of a Monte Carlo version of the classical Expectation Maximization (EM) algorithm, in which we treat the random variable  as missing (unobserved) data. Although this approach does not allow us to find the ML estimate of

as missing (unobserved) data. Although this approach does not allow us to find the ML estimate of  , we discuss below how this can be achieved using a simple grid search.

, we discuss below how this can be achieved using a simple grid search.

Recall that each iteration of the EM algorithm consists of an estimation (E) and a maximization (M) step. Let us denote the old parameters determined in the previous M-step by  , and the new parameters with respect to which the

, and the new parameters with respect to which the  -function has to be maximized in the next M-step by

-function has to be maximized in the next M-step by  , where

, where  is a fixed value for

is a fixed value for  . The two steps of the EM algorithm are then as follows:

. The two steps of the EM algorithm are then as follows:

Monte Carlo E-step. In this step, we simulate stochastically  vectors

vectors  according to the multi-Poisson distribution

according to the multi-Poisson distribution  . For this we use an MCMC scheme that fully exploits the fast computation of inverses discussed above (see Appendix 2 for details).

. For this we use an MCMC scheme that fully exploits the fast computation of inverses discussed above (see Appendix 2 for details).

Determine the weights

with

In the M-step we have to maximize the function

| (5) |

with respect to the parameters  where

where

From Bayes’ theorem we have

| (6) |

Thus, according to our Monte Carlo scheme and up to the factor  , the infinite sum in (5) can be approximated by

, the infinite sum in (5) can be approximated by

| (7) |

where  and

and  are given by (2) and (3), respectively.

are given by (2) and (3), respectively.

M-step. In this step, we seek the parameters  which maximize the sum in (7) and which will serve as “old” parameters in the next E-step. We have

which maximize the sum in (7) and which will serve as “old” parameters in the next E-step. We have

where  is the total length of the tree

is the total length of the tree  ,

,  denotes the sum of the components of

denotes the sum of the components of  , and

, and  is a factor that does not depend on any of the parameters

is a factor that does not depend on any of the parameters  . From this it is easy to see that

. From this it is easy to see that

| (8) |

independently of the values of the other three parameters. Since we assume the value of  to be fixed, we can also give explicit expressions for the values of

to be fixed, we can also give explicit expressions for the values of  and

and  which maximize

which maximize  . First, determine the matrix

. First, determine the matrix

| (9) |

Standard calculus shows that

| (10) |

and

| (11) |

We note that the EM algorithm can be implemented without the Monte-Carlo part if we impose a condition  on the likelihood, i.e., if we suppose a priori that there have been only

on the likelihood, i.e., if we suppose a priori that there have been only  or less Poisson events on the tree

or less Poisson events on the tree  . In that case, the sum in (5) is over all

. In that case, the sum in (5) is over all  such that

such that  (see Appendix 3).

(see Appendix 3).

Estimating factor  .

.

—The Monte Carlo EM algorithm proposed above, while computationally highly efficient, does not allow for the estimation of the factor  . We thus use a numerical approach to iteratively approach the ML estimate of

. We thus use a numerical approach to iteratively approach the ML estimate of  . Specifically, we start at a value

. Specifically, we start at a value  and then iteratively increase that value such that

and then iteratively increase that value such that  until the likelihood decreases. The algorithm then turns back by setting

until the likelihood decreases. The algorithm then turns back by setting  and proceeds again until the likelihood decreases. With every switch, the step size gets smaller and the estimate is guaranteed to get closer to the true MLE value as we found the likelihood surface to have a single peak (Figure S1 available as Supplementary Material on Dryad at http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.170rb). In each step, we use the Monte Carlo EM algorithm described above to calculate the likelihood at the MLE estimates of all other parameters conditioned on that

and proceeds again until the likelihood decreases. With every switch, the step size gets smaller and the estimate is guaranteed to get closer to the true MLE value as we found the likelihood surface to have a single peak (Figure S1 available as Supplementary Material on Dryad at http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.170rb). In each step, we use the Monte Carlo EM algorithm described above to calculate the likelihood at the MLE estimates of all other parameters conditioned on that  value. In all application we set

value. In all application we set  and the initial

and the initial  and found estimates to be accurate within five switches corresponding to about 15 values tested.

and found estimates to be accurate within five switches corresponding to about 15 values tested.

Identifying jump locations.

—To infer the location of jumps on a phylogenetic tree we implement an empirical Bayes approach. As is commonly done in such a setting, we assume the ML estimates  and

and  obtained using our Monte Carlo EM scheme are accurate and thus known constants when inferring jump locations. Under this assumption, the MCMC approach introduced above can also be used to sample configurations of jumps

obtained using our Monte Carlo EM scheme are accurate and thus known constants when inferring jump locations. Under this assumption, the MCMC approach introduced above can also be used to sample configurations of jumps  from the probability distribution

from the probability distribution  . This allows us to numerically infer for each branch

. This allows us to numerically infer for each branch  the posterior probabilities of

the posterior probabilities of  and

and  , and thus to identify branches for which there is convincing evidence for an evolutionary jump.

, and thus to identify branches for which there is convincing evidence for an evolutionary jump.

Implementation.

—We implemented the algorithm introduced here in C++ and optimized the code for speed. A user-friendly program to apply it to data is available at our lab website (http://www.unifr.ch/biology/research/wegmann/).

Simulations

Convergence

Convergence of the MCMC.

—We assessed the convergence of MCMC chains by comparing parameter estimates between two independent and parallel chain runs until 10,000 jump vectors  were sampled. We run a total of 100 such chain pairs for each of two different starting locations and discarded the first 100 such vectors as burn-in. We also compared two different values to thin the chains: either we sampled every 10th or every 5000th step. Here we define an MCMC step as one proposed update for each branch (hence one step consist of as many iterations as there are branches in the tree).

were sampled. We run a total of 100 such chain pairs for each of two different starting locations and discarded the first 100 such vectors as burn-in. We also compared two different values to thin the chains: either we sampled every 10th or every 5000th step. Here we define an MCMC step as one proposed update for each branch (hence one step consist of as many iterations as there are branches in the tree).

Regardless of the starting values, convergence was reached rather fast but with some variation across parameters (Figure S2 available as Supplementary Material on Dryad). The parameter to converge fastest was  , for which the difference in estimates was below 0.01 within 2000 sampled jump vectors for 90% of all chain pairs. Similarly small differences for

, for which the difference in estimates was below 0.01 within 2000 sampled jump vectors for 90% of all chain pairs. Similarly small differences for  and

and  were only reached after sampling about 4000 jump vectors (Figure S2 available as Supplementary Material on Dryad). Interestingly, a larger thinning did not improve convergence, suggesting that the variance in estimates is dominated by variation in the jump vectors sampled, but not by autocorrelation along the chain. This was further confirmed when we repeated the same experiment for much larger trees with 1000 leaves and sampling every second step to reflect the larger number of iterations per step, in which case convergence was observed at the same rate (Figure S3 available as Supplementary Material on Dryad). For subsequent analyses, we sampled a total of 5000 jump vectors an used thinning of 10 and two for trees with 100 and 1000 leaves, respectively.

were only reached after sampling about 4000 jump vectors (Figure S2 available as Supplementary Material on Dryad). Interestingly, a larger thinning did not improve convergence, suggesting that the variance in estimates is dominated by variation in the jump vectors sampled, but not by autocorrelation along the chain. This was further confirmed when we repeated the same experiment for much larger trees with 1000 leaves and sampling every second step to reflect the larger number of iterations per step, in which case convergence was observed at the same rate (Figure S3 available as Supplementary Material on Dryad). For subsequent analyses, we sampled a total of 5000 jump vectors an used thinning of 10 and two for trees with 100 and 1000 leaves, respectively.

We next assessed the convergence of the MCMC for the inference of jumps on trees by assessing the difference in posterior probabilities between independent chains for trees with 100 and 1000 leaves (Figures S4 and S5 available as Supplementary Material on Dryad). We again run 100 chain pairs, fixed the thinning to 10 or two for trees with 100 or 1000 leaves, respectively, and discarded the first 100 jump vectors as burn-in. Although we found convergence to be reached within less than 2000 iterations for branches with very low ( ) and very high (

) and very high ( ) posterior probabilities, more iterations were required for branches with intermediate posterior probabilities. We found that sampling 5000 jump vectors gave very consistent results also for inferring the location of jumps.

) posterior probabilities, more iterations were required for branches with intermediate posterior probabilities. We found that sampling 5000 jump vectors gave very consistent results also for inferring the location of jumps.

Convergence of the EM for parameter inference.

—To test if the stochastic EM algorithm converges with the MCMC settings determined above, we run the EM for a wide range of parameter values for up to 100 iterations. Since the EM algorithm is stochastic, it does not converge onto a single value unless an infinitely large sample of  vectors are used. We thus first inspected obtained patterns visually and found that parameter estimates stabilized after only a few iterations,

usually between 10 and 20, regardless of tree size (Figures S6 and S7 available as Supplementary Material on Dryad).

vectors are used. We thus first inspected obtained patterns visually and found that parameter estimates stabilized after only a few iterations,

usually between 10 and 20, regardless of tree size (Figures S6 and S7 available as Supplementary Material on Dryad).

We then implemented two different measurements to assess convergence more formally: the first is a test statistic assessing the presence of a trend in the parameter estimates, and the second is quantifying the number of slope changes in the individual parameter updates (see Appendix 4).

Power to Reject Brownian Motion

To assess the power of our approach to identify Lévy processes and to estimate associated parameters, we run our EM algorithm on data simulated with jumps on trees of 100 leaves, each simulated using a birth–death model (Stadler 2011) and scaled to a total length of 1. We generated 100 such simulations for many combinations of number of jumps and  values but fixed

values but fixed  and

and  because changing these parameters does not affect the inference. We then inferred the MLE estimates for all parameters under both the null model (Brownian motion) and under the alternative Lévy model.

because changing these parameters does not affect the inference. We then inferred the MLE estimates for all parameters under both the null model (Brownian motion) and under the alternative Lévy model.

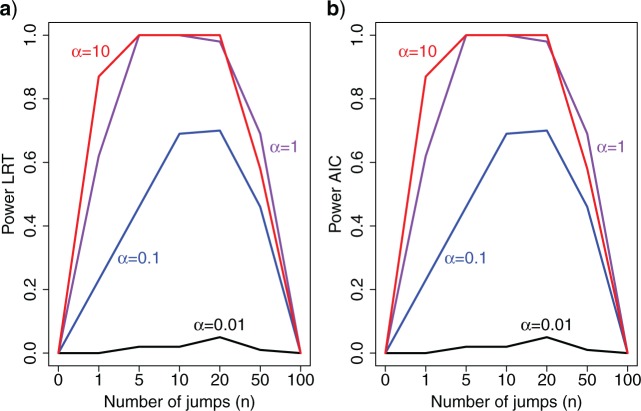

Using both a likelihood ratio test (LRT) or the Akaike Information Criterion resulted in generally substantial power to reject the null model over a large range of jumps simulated and for many different values of  (Fig. 1). Unsurprisingly, power was much lower if simulated jumps were on the order of the change of the Brownian background process or lower. Here we simulated trees of length 1, and thus the average length of each of the

(Fig. 1). Unsurprisingly, power was much lower if simulated jumps were on the order of the change of the Brownian background process or lower. Here we simulated trees of length 1, and thus the average length of each of the  branches on a tree with 100 leaves was roughly 0.005. Hence with

branches on a tree with 100 leaves was roughly 0.005. Hence with  , the strength of half of the evolutionary jumps are expected to be smaller or equal to the effect of the background process on an average branch. However, with

, the strength of half of the evolutionary jumps are expected to be smaller or equal to the effect of the background process on an average branch. However, with  , the power to reject the null model was

, the power to reject the null model was  if multiple jumps were present on the tree.

if multiple jumps were present on the tree.

Figure. 1.

Power to reject the null model (Brownian motion) using a likelihood ratio test (LRT) a), or the Akaike information criterion (AIC); b) as a function of the number of simulated jumps  and the jump strengths

and the jump strengths  .

.

Interestingly, we also found our approach to regularly fail to reject the null model if the number of jumps was very large, i.e., on the order of the number of branches (50 jumps correspond to a jump on every 4th branch). In such situations, the large variance in traits observed under the Lévy model is also perfectly explained by a pure BM model with larger variance  (see below). Surprisingly, we did not observe this effect at larger trees of 1,000 leaves at the same proportion of jumps (Figure S8 available as Supplementary Material on Dryad), suggesting that the fraction of branches with jumps required for the model to reduce to pure Brownian motion is larger for larger trees.

(see below). Surprisingly, we did not observe this effect at larger trees of 1,000 leaves at the same proportion of jumps (Figure S8 available as Supplementary Material on Dryad), suggesting that the fraction of branches with jumps required for the model to reduce to pure Brownian motion is larger for larger trees.

In summary, these results show that our method has considerable power to detect Lévy processes as long as jumps are meaningfully strong and there are not too many jumps, in which case the Lévy and BM models become indistinguishable from each other.

Accuracy in Inferring Lévy Parameters

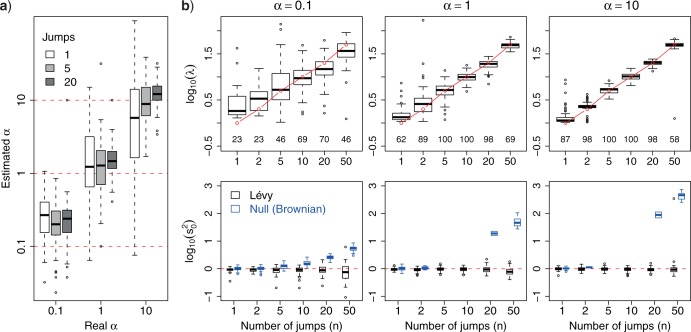

For the cases in which the Lévy model was preferred we next evaluated the power of our approach to infer the associated parameters, starting with the jump strength  and trees with 100 leaves. We found that our approach infers

and trees with 100 leaves. We found that our approach infers  quite accurately over the whole range, but we observed a slight overestimation for lower

quite accurately over the whole range, but we observed a slight overestimation for lower  values. This is a direct result of the low power to reject a model of Brownian rate at these lower jump strengths such that for simulations that resulted in larger jumps the Brownian model was more easily rejected. But the inferred values for

values. This is a direct result of the low power to reject a model of Brownian rate at these lower jump strengths such that for simulations that resulted in larger jumps the Brownian model was more easily rejected. But the inferred values for  were rarely further from the true value than a factor of 2 if multiple jumps were present (Fig. 2a), whereas it was unsurprisingly much harder to accurately infer the jump strength in case of a single jump.

were rarely further from the true value than a factor of 2 if multiple jumps were present (Fig. 2a), whereas it was unsurprisingly much harder to accurately infer the jump strength in case of a single jump.

Figure. 2.

Accuracy in inferring Lévy parameters. Each boxplot represents the distribution of inferred values across 100 replicates simulated as described in the text for different combinations of jump strengths  and number of simulated jumps

and number of simulated jumps  . a) Accuracy in inferring factor

. a) Accuracy in inferring factor  . The true

. The true  values used in the simulations are indicated with red dashed lines. b) Top row: distributions of inferred jump rate

values used in the simulations are indicated with red dashed lines. b) Top row: distributions of inferred jump rate  . Connected red open circles represent the true values. The numbers printed below the boxplots indicate the percentage of simulations for which the Brownian model was rejected and are hence included here. Bottom row: distributions of inferred Brownian background rates

. Connected red open circles represent the true values. The numbers printed below the boxplots indicate the percentage of simulations for which the Brownian model was rejected and are hence included here. Bottom row: distributions of inferred Brownian background rates  for simulations in which the Brownian null model was rejected (black) or not rejected (blue).

for simulations in which the Brownian null model was rejected (black) or not rejected (blue).

We next evaluated the accuracy of our approach in inferring the jump rate  , again limited to the simulations in which a Lévy model was preferred. As shown in Figure 2b, our method inferred this parameters very accurately over a large range of jumps simulated and for all values of

, again limited to the simulations in which a Lévy model was preferred. As shown in Figure 2b, our method inferred this parameters very accurately over a large range of jumps simulated and for all values of  , with generally higher accuracy with higher

, with generally higher accuracy with higher  values.

values.

We then finally evaluated the accuracy in inferring the Brownian background rate  (Figure 2b) and found it to be very accurately inferred whenever the Brownian model was rejected. Interestingly, however,

(Figure 2b) and found it to be very accurately inferred whenever the Brownian model was rejected. Interestingly, however,  was overestimated whenever the Brownian model could not be rejected but jumps were simulated. This illustrates that under certain conditions a Lévy model is indistinguishable from a model of pure Brownian motion with an elevated rate. This is particularly true in the case of weak jumps (small

was overestimated whenever the Brownian model could not be rejected but jumps were simulated. This illustrates that under certain conditions a Lévy model is indistinguishable from a model of pure Brownian motion with an elevated rate. This is particularly true in the case of weak jumps (small  ) or if jumps are very common on the tree.

) or if jumps are very common on the tree.

As expected given the larger amount of information, the hierarchical parameters are estimated much more accurately on larger trees. To illustrate this we repeated these analyses for trees with 1,000 leaves which resulted in much tighter confidence intervals for all parameters (Figure S9 available as Supplementary Material on Dryad).

Jump Location

We finally tested the power of our method to infer the location of jumps on the tree. For this we simulated trees with 100 leaves and trait data affected by 20 jumps randomly placed on each tree for different jump strengths  while fixing

while fixing  . In each case, we then assumed the Lévy parameters to be known and used our MCMC approach to calculate the posterior probability on there being at least one jump for each branch.

. In each case, we then assumed the Lévy parameters to be known and used our MCMC approach to calculate the posterior probability on there being at least one jump for each branch.

We found our method to have a very low false positive rate in identifying jumps in that a posterior probability for jumps  was never obtained for branches on which we did not simulate any jumps (Fig. 3a), and 90% of all such branches resulted in a posterior probability for jumps below 0.2 even for the weakest jump strengths simulated (

was never obtained for branches on which we did not simulate any jumps (Fig. 3a), and 90% of all such branches resulted in a posterior probability for jumps below 0.2 even for the weakest jump strengths simulated ( ).

).

Figure. 3.

Power to detect individual jumps. a) Cumulative distribution of jump posterior probabilities on all branches with (solid lines) and without (dashed lines) simulated jumps. Notice that branches with jumps have posterior probabilities that accumulate at 1, whereas branches without jumps accumulate at 0. b) Distribution of the absolute strengths of individual jumps that were either detected (white) or not detected (gray). c) Same as (a) but for trees with 1000 leaves. d) Same as (b) but for trees with 1000 leaves.

The power to infer true jumps (true positives) was also considerably high, especially for jumps of meaningful strength. For data simulated with  , for instance, 90% of all branches on which jumps were simulated resulted in a posterior probability

, for instance, 90% of all branches on which jumps were simulated resulted in a posterior probability  , and 75% even in a posterior probability

, and 75% even in a posterior probability  . The few branches with jumps for which we did not obtain decisive posterior probabilities in favor of jumps all contained jumps that were considerably weak (Fig. 3b). Such jumps are expected even for large

. The few branches with jumps for which we did not obtain decisive posterior probabilities in favor of jumps all contained jumps that were considerably weak (Fig. 3b). Such jumps are expected even for large  values since individual jump strengths are assumed to be normally distributed around zero.

values since individual jump strengths are assumed to be normally distributed around zero.

A similar pattern was observed when simulating data with smaller  , but even in the case of

, but even in the case of  we obtain posterior probabilities in favor of jumps

we obtain posterior probabilities in favor of jumps  for more than one third of the branches on which jumps were simulated (Fig. 3a). At such small

for more than one third of the branches on which jumps were simulated (Fig. 3a). At such small  values for a tree of length 1, about 40% of all jumps are expected to have a strength smaller than 10 times the effect of the Brownian process on the same branch. But we note that the difficulty in placing weak jumps did not affect the power to infer the jump rate

values for a tree of length 1, about 40% of all jumps are expected to have a strength smaller than 10 times the effect of the Brownian process on the same branch. But we note that the difficulty in placing weak jumps did not affect the power to infer the jump rate  , which was inferred quite accurately even at such low

, which was inferred quite accurately even at such low  values (Fig. 2).

values (Fig. 2).

All these findings were confirmed with simulations conducted for trees with 1000 leaves (Fig. 3c and d) if scaling  appropriately (since branches are 10 times smaller, the same power is obtained with 10 times smaller

appropriately (since branches are 10 times smaller, the same power is obtained with 10 times smaller  values).

values).

Run Times

The simulations performed here illustrate the computational efficiency of our algorithm. For a tree with 100 leaves, a single iteration of the EM required about 10 seconds on a single core of a standard desktop computer. Given that the EM converged after about 15 iterations on average, the algorithm required about 3 minutes to the find the MLE of all model parameters for a fixed  value. For a tree with 1000 leaves, the EM also took on average 15 iterations to converge, but a single EM iteration required about eight minutes, resulting in a run time of 2 hours per

value. For a tree with 1000 leaves, the EM also took on average 15 iterations to converge, but a single EM iteration required about eight minutes, resulting in a run time of 2 hours per  value. The number of

value. The number of  values to test directly translates into the estimation accuracy, but we found that very accurate estimates of

values to test directly translates into the estimation accuracy, but we found that very accurate estimates of  were obtained with our peak-finder algorithm after already 15 values. The total run time was thus 45 minutes and 30 hours for a tree with 100 and 1000 leaves, respectively. The inference of jump locations then requires just a single run of the MCMC algorithm, and hence as long as a single EM iteration (10 seconds and 8 minutes, respectively).

were obtained with our peak-finder algorithm after already 15 values. The total run time was thus 45 minutes and 30 hours for a tree with 100 and 1000 leaves, respectively. The inference of jump locations then requires just a single run of the MCMC algorithm, and hence as long as a single EM iteration (10 seconds and 8 minutes, respectively).

We note that this almost quadratic increase in computational costs between a tree with 100 and 1000 leaves is expected given that the number of branches increases quadratically with the number of leaves. We can thus speculate that the inference of evolutionary jumps on a tree with 10000 leaves will require about 10 hours per EM iteration and thus about 6 days for a single  value. To speed up the inference for trees this large we thus recommend not to use our peak-finder algorithm but rather to run a grid search over

value. To speed up the inference for trees this large we thus recommend not to use our peak-finder algorithm but rather to run a grid search over  that is readily parallelized on a computer cluster. It might further be beneficial to obtain initial estimates from a subset of the tree to restrict this search range and to initialize the EM algorithm with already appropriate values. All features required for such runs are readily available in our implementation.

that is readily parallelized on a computer cluster. It might further be beneficial to obtain initial estimates from a subset of the tree to restrict this search range and to initialize the EM algorithm with already appropriate values. All features required for such runs are readily available in our implementation.

Applications

Quantum Evolution in Anoles

There have been a few direct tests of Simpsonian jumps between adaptive zones using empirical data (Uyeda et al. 2011). Here, we analyze “evolution by jumps” in the adaptive radiation of anoles, lizards that have adaptively radiated in the Caribbean and South America (Losos 2009). Following previous work, we focused on anoles on the four islands of the Greater Antilles, as they provide a unique opportunity for testing Simpson’s theory of adaptive zones for two reasons. First, there have been repeated dispersal events among islands in the Greater Antilles (Losos et al. 1998; Mahler et al. 2010). These dispersal events represent geographic opportunities, where anole lineages reach a new island and are no longer sympatric with the former set of competitors (Mahler et al. 2010). Second, most anole species can be classified into ecomorphs, habitat specialists that have evolved repeatedly on the four islands of the Greater Antilles (Losos et al. 1998). Transitions between ecomorph categories represent the evolution of key characters in anole lineages that allow them to invade novel habitats (see Losos (2009) for a review).

Anoles have thus repeatedly experienced two conditions under which Simpson expected evolutionary jumps to be observed: dispersal into new geographic areas and the appearance of evolutionary novelties. Importantly, both ecomorph origins and transitions among islands are replicated in the phylogeny of anoles, but are still rare enough that we can estimate the position of transitions on the phylogenetic tree with some confidence (Schluter 1995; Huelsenbeck et al. 2003).

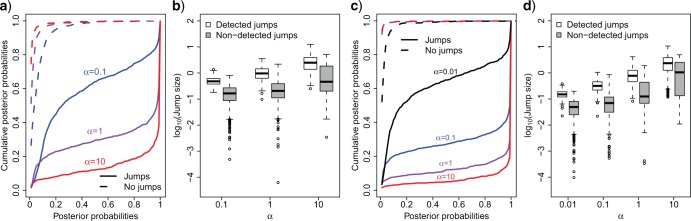

With this background in mind, we tested if a model with evolutionary jumps fits the evolution of body size in anoles better than pure Brownian motion, and if jumps correspond with either of the two factors postulated by Simpson: evolution of key characters and/or geographic dispersal. To address this question, we made use of a recent time-calibrated phylogeny of 170 Anolis lizards (Thomas et al. 2009) and analyzed snout-to-vent length (SVL), a standard phenotypic measurement of body size in lizards. This trait is broadly correlated with habitat partitioning in Greater Antillean anoles and represent the primary axes of ecologically driven evolutionary divergence in lizards (Schoener 1970; Beuttell and Losos 1999; Losos 2009). We made use of the sex-specific data of SVL from Thomas et al. (2009) and inferred evolutionary parameters independently for females and males, but excluded five species that lacked information on SVL for one or both sexes (Anolis darlingtoni, A. guamuhaya, A. loveridgei, A. oporinus, and A. polyrhachis).

We found that the Lévy jump model is preferred over a strict BM model in females, but not in males (Table 1). Evolutionary jumps indicating rapid body size evolution (Fig. 4) were found precisely at the basis of the clade comprising the ecomorph “crown giants” Thomas et al. (2009), in which females exhibit particularly large body sizes. The large sexual size dimorphism of this group (Harmon et al. 2005) is also likely explaining why the BM model fits the evolution of male body sizes well. In addition to the clades of crown giants, we also identify evolutionary jumps at the basis of the clade consisting of the species A. barbatus, A. porcus, and A. chamaeleonides. These species, which are known as “false chamaleons” and are part of the former genus Chameleolis have been called the “most bizarre West Indian lizards” (Leal and Losos 2000).

Table 1.

Inferred Lévy parameters for Anolis and Loriinii, along with the log-likelihood (ℓ) obtained under the Lévy and BM models and the p-value of a LRT contrasting these.

| Anolis | Loriini | |||||

| logSVLf | logSVLm | log Wgt | PC1 | PC2 | PC3 | |

| μ | 3.93 | 4.18 | 5.33 | –0.062 | 0.051 | 0.19 |

|

5.06 | 10.34 | 44.40 | 7.68 | 7.35 | 5.80 |

| α | 0.11 | — | — | 0.16 | 0.093 | — |

| λ | 11.27 | — | — | 11.95 | 7.38 | — |

| ℓBM | 5.03 | –15.19 | –85.54 | –65.00 | –60.63 | –6.22 |

| ℓLévy | 26.61 | –13.89 | –85.51 | –31.99 | –24.72 | –4.97 |

| LRT p | 4.3.10-10 | 0.28 | 0.97 | 4.7.10-15 | 2.3.10-16 | 0.29 |

| Preferred model | Lévy | BM | BM | Lévy | Lévy | BM |

Figure. 4.

Inferred jumps for female body-size evolution on the anoles’ tree. The trait measured was the snout-to-vent length (SVL). Branches are colored according to their inferred jump posterior probability (black to red scale going from posterior probability 0 to 1, respectively). Tips are colored according to ecomorphs as defined by Thomas et al. (2009).

Our analyses support two main conclusions. First, evolutionary change in female anoles is not well described by a uniform random walk. A better description of anole evolution combines a uniform component of change that is punctuated by rapid jumps in trait values. Second, these jumps in body size very well correspond to ecological transitions to novel ecomorphs. The evolution of this trait is thus consistent with Simpson’s description of evolutionary jumps associated with the entry into new adaptive zones. The fact that we did not find such jumps at the basis of clades of other ecomorphs suggests that body size was not a trait strongly contributing to the ecological transition of those. However, evolutionary jumps might well be found at the basis of those clades when focusing on more relevant traits.

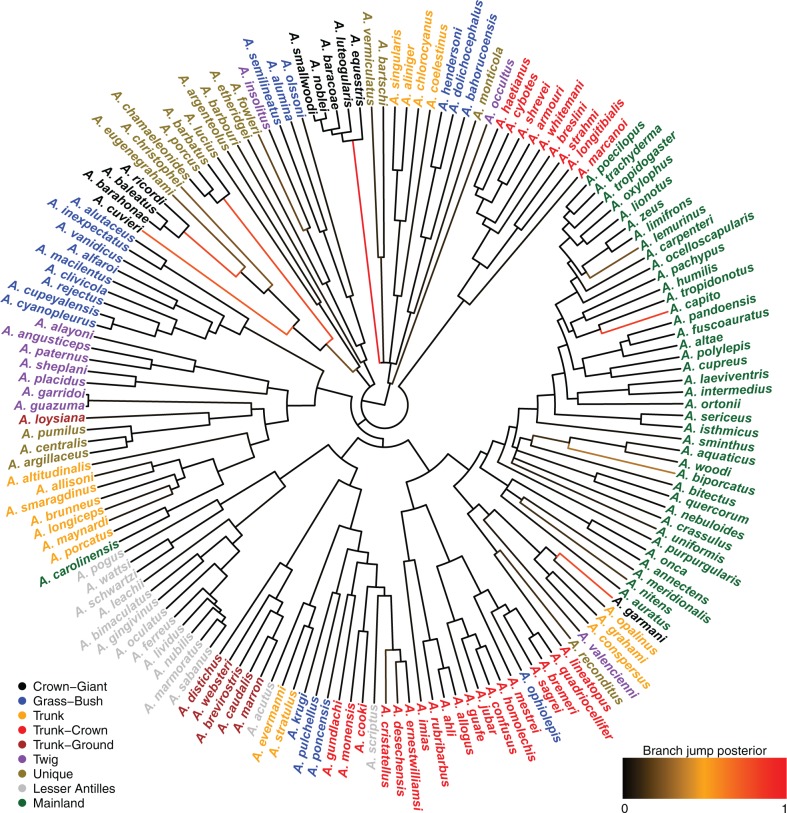

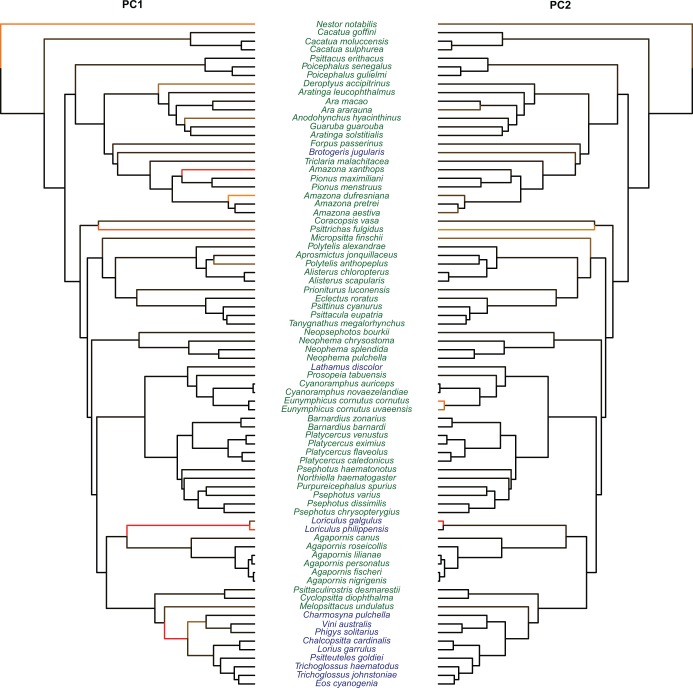

Nectarivory Evolution in Loriini

The Australasian lories belong to the tribe Loriini (Joseph et al. 2012) and are extremely species rich (Schweizer et al. 2011). Their digestive tract is highly adapted to a nectarivorous diet (Güntert 2012) and Schweizer et al. (2014) has shown quantitatively that a switch in diet to nectarivory might be considered an evolutionary novelty that created an ecological opportunity for species proliferation through allopatric partitioning of the same new niche. Using the methodology developed above we tested if the evolution of the morphology of the digestive tract in parrots as a whole is better characterized by a model of evolutionary jumps or Brownian motion. For this we made use of data from Schweizer et al. (2014), to generate a time-calibrated phylogeny of 78 parrot species using BEAST (Drummond and Rambaut 2007) implementing a secondary calibration point from Schweizer et al. (2011) for the initial split within parrots. The following 13 measurements of the morphology of the digestive tract were used: the length of intestine, length of esophagus, extension of esophagus glands, length of intermediate zone, length of proventriculus, gizzard height, gizzard width, gizzard depth, maximum gizzard height at main muscles, gizzard thickness at main muscles, gizzard lumen width including koilin layer, gizzard width at the caudoventral thin muscle, maximum gizzard height at the thin muscle, and the maximum gizzard lumen at the thin muscle. Since many of the morphological characters of the digestive tract considered are both highly correlated with body size as well as among themselves, we first regressed out body mass (Wgt) from each other morphological trait and then summarized the residuals of all traits using the first three principal components (PCA; see also (Revell 2009)).

We found that the evolution of the first two PC axis on the morphology of the digestive tract were much better explained by a model of evolutionary jumps ( in both cases) with relatively high rates of jumps (Table 1). Overall, the jumps for PC1 identified with strongest support are both on branches basal to clades of nectarivorous species, particularly at the base of highly specialized nectar feeding Loriini, but also at the base of the genus Loriculus (Fig. 5). As postulated by Simpson the niche shift to nectarivory especially in Loriini involved a period of rapid evolution reflecting adaptations to feed effectively on nectar (and pollen) (Schweizer et al. 2014). Although the jumps within the Neotropical parrots are difficult to interpret in biological terms, the shift along the branch leading to Psittrichas fulgidus might be explained by its gizzard morphology similar to that of the Loriini probably reflecting an adaptation to its reportedly mainly frugivorous diet (Schweizer et al. 2014). Some special structures in the digestive tract of the genus Nestor have been described in Güntert (2012).

in both cases) with relatively high rates of jumps (Table 1). Overall, the jumps for PC1 identified with strongest support are both on branches basal to clades of nectarivorous species, particularly at the base of highly specialized nectar feeding Loriini, but also at the base of the genus Loriculus (Fig. 5). As postulated by Simpson the niche shift to nectarivory especially in Loriini involved a period of rapid evolution reflecting adaptations to feed effectively on nectar (and pollen) (Schweizer et al. 2014). Although the jumps within the Neotropical parrots are difficult to interpret in biological terms, the shift along the branch leading to Psittrichas fulgidus might be explained by its gizzard morphology similar to that of the Loriini probably reflecting an adaptation to its reportedly mainly frugivorous diet (Schweizer et al. 2014). Some special structures in the digestive tract of the genus Nestor have been described in Güntert (2012).

Figure. 5.

Evolutionary jumps in the morphology of the digestive tract in parrots. Results for PC1 are shown on the left phylogeny, and results for PC2 on the right phylogeny. Branches are colored according to their inferred jump posterior probability (black to red scale going from posterior probability 0 to 1, respectively). Species names are colored according to their diet: nectarivorous (blue) and nonnectarivorous (green).

Discussion

Although many traits appear to evolve at relatively constant rates over long time periods and across many taxa, some traits seem to undergo periods of rather rapid evolution (see Arnold (2014)). Simpson (1944). Simpson (1944) postulated that such evolutionary jumps are triggered by a change in selection pressure after lineages transitioned into different adaptive zones, for instance by dispersing into new geographic areas, after the appearance of evolutionary novelties, key innovations, or after rapid climatic or ecological changes of the environment. The appearance of well-calibrated phylogenies along with recent statistical developments now allow to test such models on a wide variety of data.

Bokma (2008), for instance, proposed to model evolutionary jumps as a compound process of a continuous background process and a discrete jump process. Recently, Landis et al. (2013) introduced a general framework to infer parameters of such Lévy processes under a Bayesian framework by means of Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC). Unfortunately this approach, while elegant, requires the calculation of the inverse of the variance–covariance matrix describing the correlations between traits as a function of the phylogenetic tree and the jump process, which is computationally prohibitive for large trees.

Here we introduce a computationally highly efficient variant of this approach that naturally scales to large trees. The basis of our approach is an MCMC algorithm in which we can update the inverse of the above mentioned variance–covariance matrix directly without inversion when sampling jump configurations with fixed hierarchical parameters (root state, Brownian rate, jump strength and jump rate). To make use of this development for inference we propose a two-step approach in which the MCMC algorithm is embedded into an Expectation–Maximization (EM) approach to obtain maximum likelihood (ML) estimates of the hierarchical parameters while integrating over jump configurations. In a second step, the location of jumps can then be inferred under an empirical Bayes framework in which the hierarchical parameters are fixed to their ML estimate and the developed MCMC algorithm is used to obtain for each branch the posterior probability that a jump occurred at this location.

There are also other methods that deal with the burden of calculating inverses and determinants of variance–covariance matrices. For instance, Freckleton (2012) applied the results of Felsenstein (1973) and Felsenstein (1985) to calculate the likelihood in linear time of a BM model. FitzJohn (2012) also proposed a fast algorithm to calculate BM and OU likelihoods using Gaussian elimination, but this is not applicable to non-Gaussian traits. Tung Ho and Ané (2014) proposed a new method, which efficiently calculates likelihoods by avoiding the calculation of the inverse and determinant of the variance–covariance matrix. Their method requires that this matrix belongs to a class of generalized 3-point structured matrices. Our method, which applies an iterative scheme, differs from the others in the sense that the inverse and determinant of the variance–covariance matrix has to be calculated only once when obtaining the likelihoods, thus obtaining rather fast calculation times.

We demonstrated the applicability of our approach by identifying evolutionary jumps for body size evolution in Anolis lizards and the evolution of gut morphology in Australasian lories of the tribe Loriini. We found strong support for evolutionary jumps in both systems that provide direct support for Simpson’s quantum evolutionary hypothesis of adaptive zones. Among the anoles, for instance, we identified evolutionary jumps on the basal lineage leading to crown giants, a group of lizards that transitioned into a novel niche for hunting: the crowns of large tropical trees. Similarly, we identified jumps at the basis of clades of lories that transitioned to nectarivory, an evolutionary novelty that triggered rapid changes in morphology of the digestive system and promoted significant lineage diversification, which was probably mainly non-adaptive after the basal diet shift through allopatric partitioning of the same niche (Schweizer et al. 2014, cf.).

These results also show that the distinction between “gradual” and “punctuated” models of evolution is a false dichotomy; instead, evolution has a gradual component that may be frequently punctuated by periods of rapid change (Levinton 2001). We further note that in both cases studied here a single jump at the basis of clades is sufficient to explain their trait data, suggesting that the period of rapid evolution was limited to a single branch and that the background rate remained constant. We suggest that future work should follow Simpson’s lead and focus on the factors that promote these pulses of evolutionary change.

Although we model evolutionary jumps as instantaneous, we want to be clear that we are not invoking actual instantaneous evolutionary change (e.g., “hopeful monsters”) (Goldschmidt 1940; Charlesworth et al. 1982). Typical microevolutionary processes of selection and drift can cause change that would appear to be instantaneous when viewed over the timescale of macroevolution. Our model is also distinct from punctuated equilibrium, which requires evolutionary jumps to occur only at speciation events (Eldredge and Gould 1972). The punctuated changes in our model occur along branches in the tree and are not necessarily associated with speciation events. In fact, for the case of anoles, two lines of evidence argue against punctuated equilibrium: first, most speciation events in the tree are not associated with jumps; and second, we know from detailed microevolutionary studies that anole body size can evolve rapidly in response to selection even in the absence of speciation (e.g., Losos et al. (2006)).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material including Figures can be found in the Dryad data repository at http://dx.doi.org/10.5061/dryad.170rb.

Funding

This study was supported by Swiss National Foundation grant [31003A_149920 to D.W.]. The work of S. M. Szilágyi was supported by the János Bolyai Fellowship Program of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the helpful comments Folmer Bokma made in his signed review.

Appendix 1

Efficient Calculation of Inverses and Determinants

For a symmetric non-singular matrix  and a (column) vector

and a (column) vector  , we have

, we have

| (1) |

(see Izenman (2008), p. 47) and

| (2) |

(see Anderson 2003, Corollary A.3.1). These formulae have recently been shown to speed up the calculation of the likelihood function under Brownian motion models (Tung Ho and Ané 2014). Here we use them to develop a fast algorithm applicable to Lévy processes.

Let us first fix some notation: For each branch  , we define the

, we define the  incidence matrix

incidence matrix  by setting

by setting  if the branch

if the branch  is common to the pair of leaves

is common to the pair of leaves  , and

, and  otherwise. Clearly,

otherwise. Clearly,

In the following we replace the parameter  with the positive factor

with the positive factor  given by

given by  . Observe that

. Observe that

where

and  . Finally, we introduce for

. Finally, we introduce for  the (column) vectors

the (column) vectors  , each one with

, each one with  components. The

components. The  -th component

-th component  is equal to

is equal to  if leaf

if leaf  is subordinate to branch

is subordinate to branch  (i.e., the path from the root

(i.e., the path from the root  to node

to node  contains branch

contains branch  ). Otherwise, if leaf

). Otherwise, if leaf  is not subordinate to branch

is not subordinate to branch  , then

, then  . It is easy to see that

. It is easy to see that  and thus

and thus

| (3) |

We can now apply formulae (1) and (2) to obtain the following iterative scheme for the computation of  and

and  :

:

First, determine  and

and  . Then, for each term with

. Then, for each term with  in the sum (3), update

in the sum (3), update  to

to  etc. as follows: Let

etc. as follows: Let

and calculate

| (4) |

When all non-zero terms in (3) have been considered, we arrive at  and

and  . Observe that in this scheme, the only matrix inverse that ever has to be determined is

. Observe that in this scheme, the only matrix inverse that ever has to be determined is  . The number of non-zero

. The number of non-zero  will frequently be small compared to

will frequently be small compared to  and so will be the number of iterations (4).

and so will be the number of iterations (4).

Appendix 2

Simulating  with MCMC

with MCMC

Here we describe how to sample the states  from the probability distribution

from the probability distribution  using the Metropolis scheme. (To unburden the notation in the description of the MCMC algorithm, we drop the tilde overscript on the parameters.) At each state we will need the inverse matrix

using the Metropolis scheme. (To unburden the notation in the description of the MCMC algorithm, we drop the tilde overscript on the parameters.) At each state we will need the inverse matrix  of

of  given by (3). Start the chain e.g., at

given by (3). Start the chain e.g., at  and with

and with  .

.

-

1.

Let

denote the current state of the Markov chain and

denote the current state of the Markov chain and  the inverse matrix of

the inverse matrix of  . Choose an index

. Choose an index  with equal probability (or with a probability proportional to

with equal probability (or with a probability proportional to  ) and an increment

) and an increment  or

or  with probability

with probability  . The candidate state

. The candidate state  is given by in- or decreasing the

is given by in- or decreasing the  -th index

-th index  by

by  :

:  .

. - 2.

-

3.With probability

jump to the candidate state

jump to the candidate state  , otherwise stay at

, otherwise stay at  . In the first case, update

. In the first case, update

and go to step .

.

No matrix inverse must ever be calculated in this scheme thanks to the update in step  . (To counterbalance the accumulation of numerical errors it might however be wise to occasionally calculate

. (To counterbalance the accumulation of numerical errors it might however be wise to occasionally calculate  from scratch.)

from scratch.)

After the burn-in phase, a fraction  of the simulated states will be retained (thinning out). These will be used to replace the matrix (9) in the M-step of the EM algorithm by

of the simulated states will be retained (thinning out). These will be used to replace the matrix (9) in the M-step of the EM algorithm by

| (5) |

Appendix 3

Conditional Likelihood

If we suppose a priori that there have been only  or less Poisson events on the tree

or less Poisson events on the tree  , the EM algorithm can be implemented deterministically. In that case, the sum in (5) is over all

, the EM algorithm can be implemented deterministically. In that case, the sum in (5) is over all  such that

such that  . Observe that we have to use the conditional probabilities

. Observe that we have to use the conditional probabilities

The new  -function is

-function is

| (6) |

where we can use

In the conditional case, there no longer seems to exists a closed formula like (8) for the optimal  . Setting the derivative of (6) w.r.t.

. Setting the derivative of (6) w.r.t.  equal to

equal to  , one can show that

, one can show that  is the root of the following

is the root of the following  -th order polynomial:

-th order polynomial:

i.e.,  . The estimation of

. The estimation of  and

and  , on the other hand, remains exactly as given by (10) and (11), respectively.

, on the other hand, remains exactly as given by (10) and (11), respectively.

Appendix 4

Assessing Convergence of the Stochastic EM

We introduce two measures to assess convergence of the Monte Carlo EM algorithm.

Regression criterion.

—We consider a time series  and construct a test statistic which allows to reject the null hypothesis that the time series exhibits no trend. For this we estimate the slope

and construct a test statistic which allows to reject the null hypothesis that the time series exhibits no trend. For this we estimate the slope  of the regression line passing through the data points

of the regression line passing through the data points  and test for the null hypothesis

and test for the null hypothesis  (no trend). Determine the following quantities:

(no trend). Determine the following quantities:

The test statistic

has the Student’s  -distribution with

-distribution with  degrees of freedom. We reject the null hypothesis on the level

degrees of freedom. We reject the null hypothesis on the level  if

if  . A good rule of thumb (for

. A good rule of thumb (for  roughly

roughly  and

and  ) is

) is  .

.

Proportion of slope sign changes.

—We propose a second way of assessing convergence by taking the last  values of the EM algorithm and counting the number of times

values of the EM algorithm and counting the number of times  there is a change in the sign of the slope between consecutive values. If convergence is reached, we expect the number of slopes with a positive sign to be similar to the number of slopes with a negative sign. We report the test statistic

there is a change in the sign of the slope between consecutive values. If convergence is reached, we expect the number of slopes with a positive sign to be similar to the number of slopes with a negative sign. We report the test statistic

where  represents the total number of possible sign changes among the last

represents the total number of possible sign changes among the last  values.

values.

References

- Anderson T. 2003. An introduction to multivariate statistical analysis. New York: John Wiley. [Google Scholar]

- Arnold S.J. 2014. Phenotypic evolution: the ongoing synthesis. American Naturalist 183:729–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford T.,, Hartl D.L. 2009. Optimization of gene expression by natural selection. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 106:1133–1138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beuttell K.,, Losos J.B. 1999. Ecological morphology of caribbean anoles. Herpetological Monographs, p. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Bokma F. 2008. sDetection of punctuated equilibrium by bayesian estimation of speciation and extinction rates, ancestral character states, and rates of anagenetic and cladogenetic evolution on a molecular phylogeny. Evolution 62:2718–2726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawand D., Soumillon M., Necsulea A., Julien P., Csárdi G., Harrigan P., Weier M., Liechti A., Aximu-Petri A., Kircher M., et al. 2011. The evolution of gene expression levels in mammalian organs. Nature 478:343–348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butler M.A.,, King A.A. 2004. Phylogenetic comparative analysis: a modeling approach for adaptive evolution. American Naturalist 164:683–695. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalli-Sforza L.L.,, Edwards A.W. 1967. Phylogenetic analysis. models and estimation procedures. American J. Human Genet. 19:233. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlesworth B.,, Lande R.,, Slatkin M. 1982. A neo-darwinian commentary on macroevolution. Evolution 36:474–498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davidson R.,, MacKinnon J.G. 2004. Econometric theory and methods, vol. 5 New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drummond A.J.,, Rambaut A. 2007. Beast: Bayesian evolutionary analysis by sampling trees. BMC Evolut. Biol. 7:214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eastman J.M.,, Alfaro M.E.,, Joyce P.,, Hipp A.L.,, Harmon L.J. 2011. A novel comparative method for identifying shifts in the rate of character evolution on trees. Evolution 65:3578–3589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards A., Cavalli-Sforza L., Heywood V.. 1964. Phenetic and phylogenetic classification. Systematics Association, Publication 67. [Google Scholar]

- Eldredge N.,, Gould S.J. 1972. Punctuated equilibria: an alternative to phyletic gradualism. Models in Paleobiol. 82–115. [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. 1973. Maximum-likelihood estimation of evolutionary trees from continuous characters. American J. Human Genet. 25:471. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. 1985. Phylogenies and the comparative method. American Natural 125(1):1–15. [Google Scholar]

- FitzJohn R.G. 2012. Diversitree: comparative phylogenetic analyses of diversification in r. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3:1084–1092. [Google Scholar]

- Freckleton R.P. 2012. Fast likelihood calculations for comparative analyses. Methods Ecol. Evol. 3:940–947. [Google Scholar]

- Freckleton R.P.,, Harvey P.H.,, Pagel M. 2002. Phylogenetic analysis and comparative data: a test and review of evidence. American Naturalist 160:712–726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldschmidt R. 1940. The material basis of evolution, vol. 28 New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Güntert M. 2012. Morphologische Untersuchungen zur adaptiven Radiation des Verdauungstraktes bei Papageien (Psittaci). Zoologische Jahrbucher. Abteilung für Anatomie und Ontogenie der Tiere106:471–526. [Google Scholar]

- Hansen T.F. 1997. Stabilizing selection and the comparative analysis of adaptation. Evolution 51(5):1341–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harmon L.J.,, Kolbe J.J.,, Cheverud J.M.,, Losos J.B. 2005. Convergence and the multidimensional niche. Evolution 59:409–421. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huelsenbeck J.P.,, Nielsen R.,, Bollback J.P. 2003. Stochastic mapping of morphological characters. Syst. Biol. 52:131–158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingram T.,, Mahler D.L. 2013. SURFACE: detecting convergent evolution from comparative data by fitting Ornstein-Uhlenbeck models with stepwise Akaike Information Criterion. Methods Ecol. Evol. 4:416–425. [Google Scholar]

- Izenman A. 2008. Modern multivariate statistical techniques vol. 1 New York: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph L.,, Toon A.,, Schirtzinger E.E.,, Wright T.F.,, Schodde R. 2012. A revised nomenclature and classification for family-group taxa of parrots (Psittaciformes). Zootaxa 3205:26–40. [Google Scholar]

- Landis M.J.,, Schraiber J.G.,, Liang M. 2013. Phylogenetic analysis using lévy processes: finding jumps in the evolution of continuous traits. Syst. Biol. 62:193–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leal M.,, Losos J.B. 2000. Behavior and ecology of the Cuban “chipojos bobos“ Chamaeleolis barbatus and C. porcus. J. Herpetol. 34:318–322. [Google Scholar]

- Levinton J.S. 2001. Genetics, paleontology, and macroevolution. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Losos J.B. 2009. Lizards in an evolutionary tree: ecology and adaptive radiation of anoles vol. 10 University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Losos J.B. 2010. Adaptive radiation, ecological opportunity, and evolutionary determinism. American Naturalist 175:623–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Losos J.B.,, Glor R.E.,, Kolbe J.J.,, Nicholson K. 2006. Adaptation, speciation, and convergence: a hierarchical analysis of adaptive radiation in caribbean Anolis lizards 1. Annals Missouri Botanical Garden 93:24–33. [Google Scholar]

- Losos J.B.,, Jackman T.R.,, Larson A.,, de Queiroz K.,, Rodrıguez-Schettino L. 1998. Contingency and determinism in replicated adaptive radiations of island lizards. Science 279:2115–2118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mahler D.L.,, Revell L.J.,, Glor R.E.,, Losos J.B. 2010. Ecological opportunity and the rate of morphological evolution in the diversification of greater antillean anoles. Evolution 64:2731–2745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Meara B.C.,, Ané C.,, Sanderson M.J.,, Wainwright P.C. 2006. Testing for different rates of continuous trait evolution using likelihood. Evolution 60:922–933. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Revell L.J. 2009. Size-correction and principal components for interspecific comparative studies. Evolution 63:3258–3268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohlfs R.V.,, Harrigan P.,, Nielsen R. 2013. Modeling gene expression evolution with an extended ornstein-uhlenbeck process accounting for within-species variation. Mol. Biol. Evol. 31(1):201–211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schluter D. 1995. Uncertainty in ancient phylogenies. Nature 377:108–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoener T.W. 1970. Size patterns in west indian anolis lizards. ii. correlations with the sizes of particular sympatric species-displacement and convergence. Am. Naturalist 104(936):155–174. [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer M.,, Güntert M.,, Seehausen O.,, Leuenberger C.,, Hertwig S.T. 2014. Parallel adaptations to nectarivory in parrots, key innovations and the diversification of the loriinae. Ecol. Evol. 4:2867–2883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schweizer M.,, Seehausen O.,, Hertwig S.T. 2011. Macroevolutionary patterns in the diversification of parrots: effects of climate change, geological events and key innovations. J. Biogeography 38:2176–2194. [Google Scholar]

- Simpson G. 1944. Tempo and Mode in Evolution. A Wartime book. New York: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Slater G.J.,, Harmon L.J.,, Wegmann D.,, Joyce P.,, Revell L.J.,, Alfaro M.E. 2012. Fitting models of continuous trait evolution to incompletely sampled comparative data using approximate bayesian computation. Evolution 66:752–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadler T. 2011. Simulating trees with a fixed number of extant species. Syst. Biol. 60:676–684. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas G.H.,, Meiri S.,, Phillimore A.B. 2009. Body size diversification in Anolis: novel environment and island effects. Evolution 63:2017–2030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tung Ho, L.S.,, Ané C. 2014. A linear-time algorithm for gaussian and non-gaussian trait evolution models. Syst. Biol. 63:397–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyeda J.C.,, Hansen T.F.,, Arnold S.J.,, Pienaar J. 2011. The million-year wait for macroevolutionary bursts. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. 108:15908–15913. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Uyeda J.C.,, Harmon L.J. 2014. A novel Bayesian method for inferring and interpreting the dynamics of adaptive landscapes from phylogenetic comparative data. Syst. Biol. 63:902–918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]