ABSTRACT

The enzyme arginase-1 reduces the availability of arginine to tumor-infiltrating immune cells, thus reducing T-cell functionality in the tumor milieu. Arginase-1 is expressed by some cancer cells and by immune inhibitory cells, such as myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) and tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), and its expression is associated with poor prognosis. In the present study, we divided the arginase-1 protein sequence into overlapping 20-amino-acid-long peptides, generating a library of 31 peptides covering the whole arginase-1 sequence. Reactivity towards this peptide library was examined in PBMCs from cancer patients and healthy individuals. IFNγ ELISPOT revealed frequent immune responses against multiple arginase-1-derived peptides. We further identified a hot-spot region within the arginase-1 protein sequence containing multiple epitopes recognized by T cells. Next, we examined in vitro-expanded tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) isolated from melanoma patients, and detected arginase-1-specific T cells that reacted against epitopes from the hot-spot region. Arginase-1-specific CD4+T cells could be isolated and expanded from peripheral T cell pool of a patient with melanoma, and further demonstrated the specificity and reactivity of these T cells. Overall, we showed that arginase-1-specific T cells were capable of recognizing arginase-1-expressing cells. The activation of arginase-1-specific T cells by vaccination is an attractive approach to target arginase-1-expressing malignant cells and inhibitory immune cells. In the clinical setting, the induction of arginase-1-specific immune responses could induce or increase Th1 inflammation at the sites of tumors that are otherwise excluded due to infiltration with MDSCs and TAMs.

KEYWORDS: arginase, antigens, Inflammation and cancer, Immunomodulation, MDSC, Models of anticancer vaccination, Models of immunostimulation, peptide vaccine, T cells

Introduction

Neoplastic transformation is associated with immunogenic antigen expression; however, the immune system often fails to effectively respond and becomes tolerant towards these antigens.1 Successful cancer immunotherapy requires overcoming this acquired state of tolerance. Cancer cells can directly suppress anti-cancer immune mechanisms, and also attract and/or convert immunocompetent cells to generate and uphold a cancer-tolerant immune microenvironment. For example, to evade immune surveillance, tumor cells can appropriate local myeloid cells and trigger their differentiation into myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) or tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs), both of which impair anti-cancer immunity through various direct and indirect mechanisms.2–4 MDSCs and TAMs inhibit the activation, proliferation, and cytotoxicity of effector T cells and natural killer cells, as well as induce the differentiation and expansion of regulatory T cells (Tregs). The direct immunosuppressive mechanisms mediated by MDSCs and TAMs rely on the activities of enzymes, chemokines, and checkpoint molecules.4–6

The enzyme arginase-1 plays a vital role in the TAM- and MDSC-mediated induction of immune tolerance and suppression of anti-cancer immune responses. Arginase-1 catalyzes a reaction that converts the amino acid L-arginine into L-ornithine and urea, depleting the microenvironment of arginine and consequently suppressing tumor-specific cytotoxic T-cell responses.7 Several reports emphasize that altered arginine metabolism in tumors plays an important role in suppressing tumor-specific T-cell responses. Cancer cells, as well as regulatory immune cells like MDSCs and TAMs, can suppress T cells by manipulating L-arginine metabolism via expression of arginase-1.5 Thus, arginase-1 is critically involved in the inhibition or termination of inflammation. Arginase-1 is highly overexpressed in cancers, including breast, lung, colon, and prostate cancer,8–13 and increased arginase-1 activity has been detected in both malignant cells and other cells infiltrating the tumor microenvironment. In particular, arginase-1 is reportedly elevated in glioblastoma, while arginase-2 elevation has been described in acute myeloid leukemia (AML). A recent study demonstrated that acute myeloid leukemia (AML) blasts show an arginase-dependent ability to inhibit proliferation of T-cell and hematopoietic stem cells. Moreover, arginase and iNOS inhibitors reduce AML suppression activity.14

Both in vitro and in vivo studies demonstrate that transfection of mouse macrophages with a rat arginase-1 gene promotes proliferation of co-cultured tumor cells. Furthermore, induction of arginase-1 expression in macrophages reportedly increases tumor vascularization through polyamine synthesis.8 Examination of a murine lung carcinoma model revealed a subpopulation of mature tumor-associated myeloid cells that express high levels of arginase-1, which depletes extracellular L-arginine, in turn, inhibiting antigen-specific proliferation of the tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs). Injection of an arginase-1 inhibitor blocks lung carcinoma growth in these mice. This demonstrates how induction of arginase-1 expression in tumor cells and tumor-associated myeloid cells may promote tumor growth via negative effects on TILs, resulting in suppression of anti-tumor immune responses. Moreover, genetic knock-out of arginase-1 improves survival in mice receiving adoptive transfer of tumor-specific cytotoxic T cells.6

In the present study, we examined whether arginase-1 served as a target for specific T cells, which could potentially be exploited for anti-cancer immune therapy. To this end, we identified and characterized arginase-1 specific T cells that were present among peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC).

Results

Immune responses against arginase-1

We divided the entire arginase-1 protein sequence into overlapping 20-mere peptides, generating a library of 31 peptides covering the entire sequence (Table 1). Each peptide in the library overlapped with the first 10 amino acids of the following peptide. Using this arginase-1 peptide library and the IFNγ ELISPOT assay, we next screened PBMCs from patients with melanoma and healthy donors for immune responses (Fig. 1A and B). The PBMCs were stimulated for one week with a pool of 3–4 adjacent 20-mer arginase-1 library peptides and low-dose IL-2 (120 U/mL). They were then set up for an IFNγ ELISPOT assay to screen for responses against each 20-mer peptide separately. The following eight peptides showed the highest and most abundant responses in PBMCs from patients with melanoma: Arg31–50, Arg111–130, Arg161–180, Arg171–190, Arg181–200, Arg191–210, Arg221–240, and Arg261–280. Among these overlapping peptides, Arg161–180, Arg171–190, Arg181–200, and Arg191–210 spanned a 50-amino-acid-long region that was deemed a hot-spot region since nearly all patients harbored a response against one or more of these peptides (Fig. 1A). The selected eight peptides were further used to screen for immune responses against arginase-1 in PBMCs from eight healthy donors using IFNγ ELISPOT. As in the PBMCs from cancer patients, the PBMCs from healthy donors showed the highest IFNγ responses against the four arginase-1 peptides in the hot-spot region (Fig. 1B). We further used the four hot-spot region peptides to screen for responses in 25 cancer patients: 14 melanoma, 1 breast cancer, 1 renal cell carcinoma, 9 multiple myeloma (due to limited material 9 multiple myeloma patients screened for responses against Arg191–210 and 4 of these patients were screened for responses against Arg161–180, Arg171–190, Arg181–200). We found responses against Arg161–180 in 6 out of 20 screened patients (Fig. 2A), against Arg171–190 in 4 out of 20 patients (Fig. 2B), against Arg181–200 in 4 out of 20 patients (Fig. 2C) and against Arg191–210 in 10 out of 25 patients (Fig. 2D).

Table 1.

Arginase-1 peptides.

| Peptide name |

Sequence |

| Arg 1–20 | MSAKSRTIGIIGAPFSKGQP |

| Arg 11–30 | IGAPFSKGQPRGGVEEGPTV |

| Arg 21–40 | RGGVEEGPTVLRKAGLLEKL |

| Arg 31–50 | LRKAGLLEKLKEQECDVKDY |

| Arg 41–60 | KEQECDVKDYGDLPFADIPN |

| Arg 51–70 | GDLPFADIPNDSPFQIVKNP |

| Arg 61–80 | DSPFQIVKNPRSVGKASEQL |

| Arg 71–90 | RSVGKASEQLAGKVAEVKKN |

| Arg 81–100 | AGKVAEVKKNGRISLVLGGD |

| Arg 91–110 | GRISLVLGGDHSLAIGSISG |

| Arg 101–120 | HSLAIGSISGHARVHPDLGV |

| Arg 111–130 | HARVHPDLGVIWVDAHTDIN |

| Arg 121–140 | IWVDAHTDINTPLTTTSGNL |

| Arg 131–150 | TPLTTTSGNLHGQPVSFLLK |

| Arg 141–160 | HGQPVSFLLKELKGKIPDVP |

| Arg 151–170 | ELKGKIPDVPGFSWVTPCIS |

| Arg 161–180 | GFSWVTPCISAKDIVYIGLR |

| Arg 171–190 | AKDIVYIGLRDVDPGEHYIL |

| Arg 181–200 | DVDPGEHYILKTLGIKYFSM |

| Arg 191–210 | KTLGIKYFSMTEVDRLGIGK |

| Arg 201–220 | TEVDRLGIGKVMEETLSYLL |

| Arg 211–230 | VMEETLSYLLGRKKRPIHLS |

| Arg 221–240 | GRKKRPIHLSFDVDGLDPSF |

| Arg 231–250 | FDVDGLDPSFTPATGTPVVG |

| Arg 241–260 | TPATGTPVVGGLTYREGLYI |

| Arg 251–270 | GLTYREGLYITEEIYKTGLL |

| Arg 261–280 | TEEIYKTGLLSGLDIMEVNP |

| Arg 271–290 | SGLDIMEVNPSLGKTPEEVT |

| Arg 281–300 | SLGKTPEEVTRTVNTAVAIT |

| Arg 291–310 | RTVNTAVAITLACFGLAREG |

| Arg 301–322 | LACFGLAREGNHKPIDYLNPPK |

| Arg 161–190 | GFSWVTPCISAKDIVYIGLRDVDPGEHYIL |

| Arg 181–210 | DVDPGEHYILKTLGIKYFSMTEVDRLGIGK |

| Arg 161–210 | GFSWVTPCISAKDIVYIGLRDVDPGEHYILKTLGIKYFSMTEVDRLGIGK |

| Arg Short | IVYIGLRDV |

Figure 1.

Multiple arginase-1 peptides are recognized by PBMCs from cancer patients and healthy donors. A - IFNγ ELISPOT screening of responses against overlapping 20-mer arginase-1 peptides in PBMCs from 3 melanoma patients. 4–7 × 105 cells/well were used. B - IFNγ ELISPOT screening of responses against eight selected 20-mer arginase-1 peptides in PBMCs from 8 healthy donors. Spot counts are given as a difference between averages of the wells stimulated with the peptide and control wells. Peptide and control stimulations were performed in duplicates or triplicates.

Figure 2.

Arginase-1 hot-spot region is widely recognized by cancer patient PBMCs. A - IFNγ ELISPOT responses against Arg161–180 peptide. Experiments performed with 5 × 105 PBMCs/well for all cancer patients except BC30 where 3 × 105 PBMCs/wells were used. B - IFNγ ELISPOT responses against Arg171–190 peptide. Experiments performed with 5 × 105 PBMCs/well. C - IFNγ ELISPOT responses against Arg181–200 peptide. 5 × 105 PBMCs/well were used for BC30. D - IFNγ ELISPOT responses against Arg191–210 peptide. 3 × 105 cells/well used for MM22, MM25, BC30 and RCC43; 4 × 105 cells/well used for MMy15 and MMy20; 5 × 105 cells/well used for MM15, MM23, MMy1 and MMy13. MM - malignant melanoma, BC - breast cancer, MMy - multiple myeloma, RCC- renal cell carcinoma. Peptide and control stimulations were performed in duplicates or triplicates. Overlay bars represent mean values for non-stimulated/control and peptide stimulated wells ± standard error of the mean. Responses were analyzed using distribution free resampling (DFR) rule. *- p≤0.05, ns-not significant.

Immune responses against long arginase-1 peptides

Since we most frequently observed responses against arginase-1 peptides from the hot-spot region, we next analyzed whether longer peptides covering the same sequence could be used instead of four 20-mers. A 50-mer peptide covering the entire hot-spot region elicited lower responses compared to the 20-mer peptides (data not shown). We then divided the arginase-1 hot-spot region into two 30-mer peptides that overlapped by 10 amino acids: Arg161–190 and Arg181–210. These 30-mer peptides were used to check for responses in selected PBMCs from cancer patients and healthy donors, which had previously shown responses against the 20-mer hot-spot peptides. The PBMCs were stimulated for one week with either Arg161–190 or Arg181–210 in the presence of IL-2, and were then used in IFNγ ELISPOT. PBMCs from both cancer patients and healthy donors showed high responses against Arg161–190 (Fig. 3A), comparable to the responses against 20-mer peptides. Some PBMCs also showed responses against the 30-mer Arg181–210 peptide (Fig. 3B); however, these responses were lower than those against the overlapping 20-mer peptides covering the same protein region (Fig. 1A and 1B).

Figure 3.

30-mer peptides from arginase-1hot-spot region are recognized by cancer patient and healthy donor PBMCs. A - Left: Responses against Arg161–190 peptide in PBMCs from 5 selected cancer patients and four healthy donors. Right: Well examples of responses against Arg161–190 peptide in 2 healthy donors and 2 cancer patients. B - Left: Responses against Arg181–210 peptide in PBMCs from 5 selected cancer patients and four healthy donors. Right: Well examples of responses against Arg161–190 peptide in 2 healthy donors and 2 cancer patients. Spot counts are given as a difference between averages of the wells stimulated with the peptide and control wells. Peptide and control stimulations were performed in triplicates.

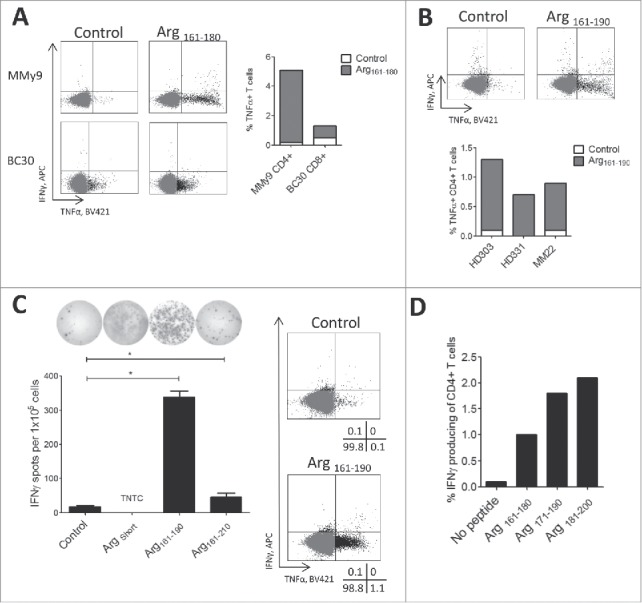

CD4+ and CD8+ T cells recognize arginase-1 in cancer patient and healthy donor PBMCs

We performed intracellular staining for IFNγ and TNFα production in PBMCs from 7 cancer patients stimulated with 20-mer hot-spot region peptides. We were able to detect CD4+ and CD8+ T cell responses against Arg161–180 (Fig. 4A) in two cancer patients, suggesting the presence of both HLA Class I and II epitopes in the arginase-1 hot-spot region. We further found that PBMCs from two healthy donors and one patient with melanoma had shown responses against the Arg161–190 peptide in IFNγ ELISPOT. We detected TNFα production by CD4+ T cells after 8-hour incubation with Arg161–190 (Fig. 4B). A minor response from CD8+ T cells in some samples (data not shown) was detected against Arg161–190.

Figure 4.

Arginase-1hot-spot region contains class I and II T-cell epitopes. A - Right: % TNFα producing CD4+ and CD8+ T cells in intracellular staining of PBMCs from multiple myeloma (MMy) and breast cancer (BC) patients stimulated with 20-mer Arg161–180 peptide and non-stimulated control. Left: representative dot plots for Arg161–180 peptide stimulated. B - Bottom: % TNFα producing CD4+ T cells in intracellular staining of PBMCs from two healthy donor and one melanoma patient production by the CD4+ T cells in response against 30-mer Arg161–180, Arg171–190, Arg181–200 peptides for 8 hours. Top: Example dot plots of non-stimulated control and Arg161–190 peptide stimulation. C - Left: IFNγ ELISPOT responses using T cell culture specific for ArgShort minimal peptide stimulated with 9-mer ArgShort, 30-mer Arg161–190 and 50-mer Arg161–210 peptides or non-stimulated control. TNTC- too numerous to count. Right: Intracellular staining of CD4+ T cell in ArgShort -specific T cell culture stimulated with Arg161–210 peptide for 8 hours. D - IFNγ production by CD4+ T cells in in vitro expanded TILs from a melanoma patient in response against Arg161–180, Arg171–190, Arg181–200 peptides as compared to non-stimulated control.

We generated an arginase-1-specific CD4+ T-cell culture by repeated stimulation of PBMCs from a melanoma patient with DCs and PBMCs that were loaded with a minimal 9-mer arginase-1 peptide (called ArgShort: IVYIGLRDV) located in the hot-spot region. The T-cell culture specific against the minimal arginase-1 epitope ArgShort also recognized the 30-mer Arg161–190 peptide (which contains the sequence of ArgShort) in IFNγ ELISPOT (Fig. 4C, left) and intracellular staining (Fig. 4C, right). After 8 hours of Arg161–190 peptide stimulation, intracellular staining revealed TNFα production from CD4+ T cells (Fig. 4C, right). However, the 50-mer peptide covering the entire hot-spot region was poorly recognized (Fig. 4C, left). TNFα secretion was confirmed by TNFα ELISA (Supplementary Figure 2).

Arginase-1 specific T cells were present in melanoma TILs

To investigate the potential presence of arginase-1-specific T cells among tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in cancer, we screened in vitro expanded TILs from eight melanoma patients for responses against arginase-1 derived peptides. To this end, we performed intracellular staining for IFNγ and TNFα production in response to direct stimulation with peptide. TILs were thawed, rested overnight without IL-2, and then stimulated for 5 hours with three hot-spot immunogenic region 20-mer peptides: Arg161–180, Arg171–190, Arg181–200. In one of the TIL cultures, IFNγ was produced by CD4+ T cells in response to stimulation with all three arginase-1 peptides (Fig. 4D), suggesting that the arginase-1hot-spot region likely contained a number of CD4+ T-cell epitopes. The percentage of IFNγ-producing cells was higher for Arg171–190 and Arg181–200 compared to Arg161–180, and the response against Arg181–200 was almost twice that against Arg161–180. No IFNγ or TNFα production was observed from CD8+ T cells.

T-cell recognition of the target cells was dependent on arginase-1 expression

To assess the ability of arginase-1-specific CD4+ T cells to recognize and react against immune cells producing arginase-1, we transfected autologous DCs and B cells with mRNA encoding arginase-1 protein. Autologous DCs were transfected with two different constructs encoding arginase-1 mRNA. One of these constructs contained the arginase-1 sequence fused to the DC-LAMP signal sequence, which targets a protein towards the lysosomal compartment and thus directs that protein towards Class II presentation.15 Arginase-1-specific CD4+ T-cell cultures from two different melanoma patients were rested without IL-2 for 24 h, and then set up for IFNγ ELISPOT with electroporated autologous DCs or B cells. We observed higher reactivity against DCs and B cells that were transfected with arginase-1 mRNA compared to Mock control (Fig. 5A-D). The responses were even higher against the DCs transfected with arginase-1-DC-LAMP compared to both Mock control and arginase-1 mRNA (Fig. 5E). After 24 h, we checked the electroporation efficiency of DCs via FACS analysis of GFP/NGFR-expressing cells, finding >90% transfection efficiency (data not shown).

Figure 5.

Arginase-1-specific T cells recognize arginase-1-expressing immune cells. A and C - IFNγ response by the arginase-1 specific T cell cultures from two different melanoma patients (MM01 and MM05) to autologous dendritic cells electroporated with irrelevant control mRNA (DC Mock) or Arginase-1 mRNA (DC Arg mRNA). Effector to target ratio 10:1. B and D - IFNγ response by the arginase-1 specific T cell cultures from two different melanoma patients to autologous B cells electroporated with irrelevant control mRNA (B cells Mock mRNA) or Arginase-1 mRNA (B cells Arg mRNA) Effector to target 2:1. E - Bottom: IFNγ response by arginase-1 specific T cell culture towards autologous dendritic cells electroporated with irrelevant control mRNA (DC Mock), arginase-1 mRNA (DC Arg mRNA) or arginase-1 mRNA containing DC-LAMP signal sequence (DC.LAMP Arg mRNA). Top: representative well images. Control and transfected cell stimulations were performed in triplicates in A and C, duplicates in B, D and E. Bars represent mean values ± standard error of the mean. *- p≤0.05 according to the DFR rule.

Discussion

The enzyme arginase-1 is involved in immunity under both normal and pathological settings.5 Arginine depletion by arginase-1-expressing myeloid cells contributes to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment that inhibits effector lymphocyte proliferation. Specific targeting of arginase-1-expressing myeloid cells (e.g., neutrophils, TAMs, and MDSC) could potentially restore arginine levels, allowing T-cell proliferation and reestablishing anti-tumor immune responses.16 In the present study, we describe arginase-1-specific effector T cells that could be exploited as a possible novel means of targeting arginase-1-expressing cells. We first identified peripheral arginase-1-specific T cells that were naturally present in both cancer patients and healthy donors by screening a peptide library covering the entire arginase-1 sequence. Interestingly, we discovered that arginase-1 contained multiple epitopes that were frequently recognized by peripheral T cells, including a 50-amino-acid-long hot-spot region (161–210) containing numerous T-cell epitopes. We observed frequent T-cell responses against arginase-1, underlining the high immunogenicity of arginase-1, and supporting the likelihood of boosting an arginase-1-specific immune response in most patients with solid tumors as well as hematological malignancies. In particular, the identified hot-spot region of the arginase-1 protein seems to be an obvious target for, e.g., peptide-based vaccination. We detected specific reactivity among in vitro expanded CD4+ TILs against peptides from this hot-spot region, indicating the presence of arginase-1-reactive T cells in the tumor microenvironment. As described by Borchers et al,17 ex vivo responses can be identify by peptide loaded autologous DCs, which could potentially reveal more frequent spontaneous responses against arginase-1.

We additionally isolated and expanded specific CD4+ T cells that reacted to peptides derived from the hot-spot region. Our results demonstrated that arginase-1-specific T cells indeed recognized and reacted to DCs and B cells that were electroporated with arginase-1 mRNA. Moreover, targeting arginase-1 towards lysosomal degradation and Class II presentation resulted in increased recognition of electroporated DCs by the arginase-1-specific CD4+ T-cell culture. Although our study focused on arginase-1-specific CD4+ T cells, we also observed CD8+ specific T-cells that were naturally present in some patients. The less frequent CD8+ T cell responses may reflect the fact that long overlapping peptides were used instead of short peptides. Recent evidence supports the view that regulatory T cells have both suppressor and effector capabilities.18 We previously reported that self-reactive pro-inflammatory T cells, termed anti-regulatory T cells (anti-Tregs),19 can specifically target immune-suppressive cells in both the periphery and the tumor microenvironment. This suggests the existence of immune system mechanisms to counteract the immune-suppressive feedback signals mediated by regulatory cells. The presently described arginase-1-specific T cells may indeed be a novel type of anti-Treg.

Suppression of the adaptive immune responses plays a major role in cancer progression, with major mechanisms of tumor immune escape including MDSC expansion and tumor signaling of programmed death 1 (PD-1).20,21 In a subset of patients with various cancer types, durable therapeutic responses can be generated via immune checkpoint blockade using antibodies against cytotoxic-T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA4) or PD1/programmed cell death 1 ligand 1 (PD-L1).22 However, checkpoint inhibitors are effective only in a small fraction of patients with advanced solid tumors. MDSCs and TAMs play important roles in tumor immune evasion, and their accumulation in the tumor bed restricts the accumulation of T cells within the vicinity of cancer cells. Therefore, these suppressive cells constitute a major reason for the limited efficacy of checkpoint blockade in cancer treatment.23 The findings of our present study may lead to a translatable strategy for improving the efficacy of checkpoint blockade through the activation of arginase-1-specific T cells that react to arginase-1-expressing cells at the tumor site, inducing local inflammation. We hypothesize that an arginase-1-specific T-cell-activating vaccine would attract T cells into the tumor, thereby inducing Th1 inflammation, which would further induce PD-L1 expression in cancer and immune cells, generating targets more susceptible to anti-PD1/PDL1 immunotherapy. Furthermore, the arginase-1-specific T cells could directly reduce arginase-1-expressing DCs, MDSCs, and TAMs, thus decreasing the tumor burden. Combinatorial therapy with an arginase-1-based vaccine and checkpoint blockade could be effective in a much wider population of cancer patients.

We previously identified self-reactive T cells that recognize human leukocyte antigen (HLA)-restricted epitopes derived from proteins, including indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase (IDO)24-26 and PD-L1,27-30 that are induced by interferons expressed at inflammation sites in regulatory immune cells. In an earlier study, we verified that interferons expand populations of PD-L1-specific anti-T cells by demonstrating that known IDO inducers (e.g., IFN-γ) lead to expansion of IDO-specific anti-Treg cells among human PBMCs without additional stimulation.25 The fact that Th1 inflammation signals induce IDO- and PD-L1-specific T cells suggests that activating arginase-1-specific T cells may work synergistically with, for example, IDO and/or PD-L1 vaccination. In this situation, arginase-1 vaccination could induce Th1 inflammation at a tumor site where myeloid cells (e.g., neutrophils, TAMs, and MDSCs) are contributing to an immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment that inhibits effector lymphocyte proliferation. This arginase-1-specific Th1 inflammation would, in turn, induce IDO and PD-L1 at the tumor site, enabling further targeting by PD-L1- and/or IDO-specific T cells. The combination of epitopes like arginase-1, PDL1, and IDO would be highly beneficial and easy to implement in a vaccine setting. Such antigens could serve as targets that would be widely applicable for immunotherapeutic strategies, completely differing from previously described antigens with regards to function and expression pattern.

The development of novel immune therapies for cancer requires a thorough understanding of the molecules involved in cancer pathogenesis, and the specific proteins recognized by the immune system. The present results suggest that an arginase-1-based vaccine may be exploited for immunotherapy, especially against cancers in which arginase-1-expressing cells represent major obstacles to the successful implementation of many forms of immunotherapy.

Materials and Methods

Patient material

Peripheral Blood Mononuclear Cells (PBMCs) were collected from healthy individuals and patients with melanoma. Blood samples were drawn a minimum of four weeks after termination of any kind of anti-cancer therapy. PBMC were isolated using Lymphoprep™ (Alere AS, cat. 1114547) separation, HLA-typed and frozen in fetal bovine serum (FBS) with 10% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich, cat. D5879-100 ML). The protocol was approved by the Scientific Ethics Committee for The Capital Region of Denmark and conducted in accordance with the provisions of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent from the patients was obtained before study entry.

Tumor infiltrating lymphocyte cultures

Surgically resected melanoma tumors were cut into 1–2 mm3 fragments under sterile conditions from which tumor infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) were minimally expanded in high doses of IL-2 (6,000 IU/mL IL2; Proleukin from Novartis) to a minimal cell count of 50 × 106 cells. Cells were further expanded using standard 14-day rapid expansion protocol (REP) with allogeneic irradiated peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from at least three different healthy donors, 30 ng/mL anti-CD3 antibodies (OKT3, from Janssen-Cilag or Miltenyi Biotec). These rapidly expanded TIL cultures were used to screen for responses against arginase-1-derived peptides.

Peptide stimulation and ELISPOT assay

PBMCs from healthy donors or cancer patients were stimulated with 20 μM of arginase-1-derived peptides and 120 U/ml IL-2 (Peprotech, cat. 200–02) for a week. 4–6 × 105 PBMCs were then placed in the bottom of ELISPOT plate (nitrocellulose bottomed 96-well plates by MultiScreen MAIP N45; Millipore, cat. MSIPN4W50) pre- coated with IFN-γ capture Ab (Mabtech, cat. 3420-3-1000) and 5–25 μM of arginase-1 derived peptides were added: 5 μM working concentration was used for 9-mer and 20-mer peptides, whereas 15–25 μM concentration was used for 30-mers. PBMCs from each patient and donors were set up in duplicates or triplicates for peptide and control stimulations. Cells were incubated in ELISPOT plates in the presence of an antigen for 14–16 hours after which they are washed off and secondary biotinylated Ab (Mabtech, cat. 3420-6-1000) was added. After 2 hour incubation unbound secondary antibody was washed off and streptavidin conjugated alkaline phosphatase (AP) (Mabtech, cat. 3310–10) was added for 1 hour. Next, unbound conjugated enzyme is washed off and the assay was developed by adding BCIP/NBT substrate (Mabtech, cat. 3650–10). Developed ELISPOT plates were analysed on CTL ImmunoSpot S6 Ultimate-V analyzer using Immunospot software v5.1. Responses were reported as the difference between average numbers of spots in wells stimulated with arginase-1 peptides and control wells.

Peptides

20-mer Arginase-1 peptide library was synthesized by PepScan and dissolved in DMSO at 10 mM. 30-mer and 50-mer Arginase-1 peptides were synthesized by Schafer-N ApS and dissolved in DMSO at 10 mM stock. ArgShort peptide was synthesized by KJ Ross-Petersen ApS and dissolved in sterile water to a stock concentration of 2 mM. Purity of the synthesized peptides was >80%. For a summary of all peptides see Table 1.

Establishment of arginase-1-specific T-cell cultures

Arginase-1-specific T cell cultures were established by initial stimulation of PBMCs obtained from patients with melanoma, with irradiated ArgShort peptide-loaded autologous dendritic cells (DCs) or PBMCs. The following day 40 U/ml IL-7 and 20 U/ml IL-12 (PeproTech, cat. 200-07-10 and 200-12) were added. Stimulation of the cultures were carried out every 8 days with ArgShort peptide loaded irradiated autologous DC followed by ArgShort peptide-loaded irradiated autologous PBMC. The day after peptide stimulation IL-2 (PeproTech, cat. 200–12) was added. Arginase-1-specific T cells were enriched using TNF-α cell enrichment kit (MiltenyiBiotec, cat. 130-091-269) after five stimulations.

Generation of dendritic cells

DCs were generated from PBMCs by adherence of monocytes on culture dishes at 37°C for 1–2 h. in RPMI-1640. Adherent monocytes were cultured in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS in the presence of IL-4 (250 U/ml) and GM-CSF (1000 U/ml) (Peprotech, cat. 200–04 and 300-03-100) for 6 days. DCs were matured by addition of IL-β (1000 U/ml), IL-6 (1000 U/ml) TNF-α (1000 U/ml) (Peprotech, cat. 200-01B, 200-06 and 300-01A) and PGE2 (1ug/ml) (Sigma Aldrich, cat. P6532).

B cell isolation

PBMCs from cancer patients were thawed and rested overnight. B cells were isolated from patient PBMCs using Pan B Cell Isolation Kit (Miltenyi Biotec Inc., cat. 130-101-638) according to manufacturer's instructions.

Production of in vitro-transcribed mRNA

The cDNA encoding Arginase-1 (accession nr. NM_000045) was synthesized and cloned into either pSP73-SphA64 (kindly provided by Dr. E. Gilboa, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, NC) using 5′XhoI/3′PacI restriction sites (Geneart/Life Technologies) or into the HLA class II targeting plasmid pGEM-sig-DC.LAMP (kindly provided by Dr. K. Thielemans, Medical School of the Vrije Universiteit Brussel) using 5′BamHI/3′BamHI restriction sites. Both plasmids were linearized with SpeI before serving as DNA template for in vitro transcription.31

Electroporation

For mRNA experiments, DCs and B cells were transfected with Arginase-1 mRNA or control mRNA encoding GFP or nerve growth factor receptor (NGFR) using electroporation parameters as previously described. Briefly, cells were washed twice, suspended in Opti-MEM medium (Invitrogen, cat. 11058021) and adjusted to a final cell density of 4–7 × 106 cells/ml. The cell suspension (200–300 ul) was pre-incubated on ice for 5 min and 5–10 μg of mRNA was added. Cell suspension was then transferred into a 4-mm gap electroporation cuvette and electroporated.31 Electroporated cells were further incubated in humidified atmosphere with 5% CO2 and used for experimental analysis as specified. Electroporation efficiency was determined 24 hours later by FACS analysis of the GFP or NGFR transfected cells.

Flow cytometric analysis

Flow cytometry analysis was performed on a FACSCanto™ II (BD Biosciences). Intracellular staining of cell cultures was performed after the cells were stimulated with 20-mer peptides for 5 hours or 30-mere peptides for 8 hours (BD GolgiPlug™ cat. 555029, was added after the first hour). The cells were then stained for surface markers, then washed and permeabilized by using Fixation/Permeabilization and Permeabilization Buffer (eBioscience, cat. 00-5123-43), according to manufacturer's instructions. Antibodies used: IFNγ-APC (cat.341117), TNFα-BV421 (cat.562783), CD4-FITC (cat.347413), CD8- PerCP (cat.345774), CD3-APC-H7 (cat. 560275) (all from BD Biosciences). Dead cells were stained using FVS510 (564406, BD Biosciences) according to manufacturer's instructions. Gating strategy is presented in Supplementary Figure 1.

ELISA

Cell culture supernatants were analyzed using TNF alpha Human Uncoated ELISA Kit (cat. 88-7346-22) (ThermoFisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Statistical analysis

ELISPOT responses were analyzed using distribution free resampling (DFR) method, described by Moodie et al.32 for statistical analysis of ELISPOT responses. Statistical analysis was performed using Rstudio (RStudio Team (2016). RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, Inc., Boston, MA URL http://www.rstudio.com/).

Supplementary Material

Disclosure of potential conflicts of interest

Mads Hald Andersen has filed a patent application based on the use of arginase-1 for vaccination. The rights of the patent application have been transferred to Copenhagen University Hospital, Herlev through the Capital Region of Denmark. The other authors declare “no conflict of interest”.

Acknowledgments

We thank Merete Jonassen and Tina Seremet for their excellent technical assistance, and Per thor Straten for scientific discussions. This work was supported by Herlev Hospital, the Danish Cancer Society, and the Danish Council for Independent Research. The funders had no role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or manuscript preparation.

References

- 1.Andersen MH. The targeting of immunosuppressive mechanisms in hematological malignancies. Leukemia. 2014;28:1784–1792. doi: 10.1038/leu.2014.108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Umansky V, Blattner C, Fleming V, Hu X, Gebhardt C, Altevogt P, Utikal J. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells and tumor escape from immune surveillance. Semin Immunopathol. 2016. PMID:27787613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schroder M, Loos S, Naumann SK, Bachran C, Krotschel M, Umansky V, Helming L, Swee LK. Identification of inhibitors of myeloid-derived suppressor cells activity through phenotypic chemical screening. Oncoimmunology. 2016;6:e1258503. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1258503. PMID:28197378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karakhanova S, Link J, Heinrich M, Shevchenko I, Yang Y, Hassenpflug M, Bunge H, von Ahn K, Brecht R, Mathes A, et al.. Characterization of myeloid leukocytes and soluble mediators in pancreatic cancer: importance of myeloid-derived suppressor cells. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e998519. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2014.998519. PMID:26137414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mondanelli G, Bianchi R, Pallotta MT, Orabona C, Albini E, Iacono A, Belladonna ML, Vacca C, Fallarino F, Macchiarulo A, et al.. A Relay Pathway between Arginine and Tryptophan Metabolism Confers Immunosuppressive Properties on Dendritic Cells. Immunity. 2017;46:233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2017.01.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marigo I, Zilio S, Desantis G, Mlecnik B, Agnellini AH, Ugel S, Sasso MS, Qualls JE, Kratochvill F, Zanovello P, Molon B, Ries CH, Runza V, Hoves S, Bilocq AM, Bindea G, Mazza EM, Bicciato S, Galon J, Murray PJ, Bronte V.. T Cell Cancer Therapy Requires CD40-CD40L Activation of Tumor Necrosis Factor and Inducible Nitric-Oxide-Synthase-Producing Dendritic Cells. Cancer Cell. 2016;30:377–390. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhu Z, Singh V, Watkins SK, Bronte V, Shoe JL, Feigenbaum L, Hurwitz AA. High-avidity T cells are preferentially tolerized in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Res. 2013;73:595–604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 8.Bronte V, Zanovello P. Regulation of immune responses by L-arginine metabolism. Nat Rev Immunol. 2005;5:641–654. doi: 10.1038/nri1668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Coosemans A, Decoene J, Baert T, Laenen A, Kasran A, Verschuere T, Seys S, Vergote I. Immunosuppressive parameters in serum of ovarian cancer patients change during the disease course. Oncoimmunology. 2015;5:e1111505. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2015.1111505. PMID:27141394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Song J, Lee J, Kim J, Jo S, Kim YJ, Baek JE, Kwon ES, Lee KP, Yang S, Kwon KS, et al.. Pancreatic adenocarcinoma up-regulated factor (PAUF) enhances the accumulation and functional activity of myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs) in pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2016;7:51840–51853. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.10123. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Romano A, Parrinello NL, Vetro C, Tibullo D, Giallongo C, La CP, Chiarenza A, Motta G, Caruso AL, Villari L, et al.. The prognostic value of the myeloid-mediated immunosuppression marker Arginase-1 in classic Hodgkin lymphoma. Oncotarget. 2016;7:67333–67346. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.12024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang J, Yang L, Yu L, Wang YY, Chen R, Qian J, Hong ZP, Su XS. Surgery-induced monocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells expand regulatory T cells in lung cancer. Oncotarget. 2017;8:17050–17058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Javeed N, Gustafson MP, Dutta SK, Lin Y, Bamlet WR, Oberg AL, Petersen GM, Chari ST, Dietz AB, Mukhopadhyay D, et al.. Immunosuppressive CD14+HLA-DRlo/neg monocytes are elevated in pancreatic cancer and “primed” by tumor-derived exosomes. Oncoimmunology. 2016;6:e1252013. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1252013. PMID:28197368. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mussai F, De SC, Abu-Dayyeh I, Booth S, Quek L, McEwen-Smith RM, Qureshi A, Dazzi F, Vyas P, Cerundolo V. Acute myeloid leukemia creates an arginase-dependent immunosuppressive microenvironment. Blood. 2013;122:749–758. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-480129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bonehill A, Heirman C, Tuyaerts S, Michiels A, Breckpot K, Brasseur F, Zhang Y, Van Der Bruggen P Thielemans K. Messenger RNA-electroporated dendritic cells presenting MAGE-A3 simultaneously in HLA class I and class II molecules. J Immunol. 2004;172:6649–6657. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.172.11.6649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schroder M, Loos S, Naumann SK, Bachran C, Krotschel M, Umansky V, Helming L, Swee LK. Identification of inhibitors of myeloid-derived suppressor cells activity through phenotypic chemical screening. Oncoimmunology. 2016;6:e1258503. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2016.1258503. PMID:28197378. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borchers S, Masslo C, Muller CA, Tahedl A, Volkind J, Nowak Y, Umansky V, Esterlechner J, Frank MH, Ganss C, et al.. Detection of ABCB5-tumour-antigen-specific CD8+ T cells in Melanoma Patients and Implications for Immunotherapy. Clin Exp Immunol. 2017;10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andersen MH. Anti-regulatory T cells. Semin Immunopathol. 2017;39:317–326. doi: 10.1007/s00281-016-0593-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Andersen MH. Immune Regulation by Self-Recognition: Novel Possibilities for Anticancer Immunotherapy. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107:154. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djv154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Umansky V, Blattner C, Fleming V, Hu X, Gebhardt C, Altevogt P, Utikal J. Myeloid-derived suppressor cells and tumor escape from immune surveillance. Semin Immunopathol. 2017;39:295–305. doi: 10.1007/s00281-016-0597-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pardoll DM. The blockade of immune checkpoints in cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2012;12:252–264. doi: 10.1038/nrc3239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Carbonnel F, Soularue E, Coutzac C, Chaput N, Mateus C, Lepage P, Robert C. Inflammatory bowel disease and cancer response due to anti-CTLA-4: is it in the flora? Semin Immunopathol. 2017;39:327–331. doi: 10.1007/s00281-016-0613-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Katoh H, Watanabe M. Myeloid-Derived Suppressor Cells and Therapeutic Strategies in Cancer. Mediators Inflamm. 2015;2015:159269. Epub;%2015 May;%19.:159269. doi: 10.1155/2015/159269. PMID:26078490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Munir S, Larsen SK, Iversen TZ, Donia M, Klausen TW, Svane IM, Straten PT, Andersen MH. Natural CD4(+) T-Cell Responses against Indoleamine 2,3-Dioxygenase. PLoS One. 2012;7:e34568. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0034568. PMID:22539948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sorensen RB, Hadrup SR, Svane IM, Hjortso MC, thor Straten P, Andersen MH. Indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase specific, cytotoxic T cells as immune regulators. Blood. 2011;117:2200–2210. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-06-288498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sorensen RB, Berge-Hansen L, Junker N, Hansen CA, Hadrup SR, Schumacher TN, Svane IM, Becker JC, thor Straten P, Andersen MH. The immune system strikes back: cellular immune responses against indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase. PLoS One. 2009;4:e6910. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006910. PMID:19738905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmad SM, Larsen SK, Svane IM, Andersen MH. Harnessing PD-L1-specific cytotoxic T cells for anti-leukemia immunotherapy to defeat mechanisms of immune escape mediated by the PD-1 pathway. Leukemia. 2014;28:236–238. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Munir S, Andersen GH, Met O, Donia M, Frosig TM, Larsen SK, Klausen TW, Svane IM, Andersen MH. HLA-restricted cytotoxic T cells that are specific for the immune checkpoint ligand PD-L1 occur with high frequency in cancer patients. Cancer Research. 2013;73:1674–1776. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-3507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Munir S, Andersen GH, Svane IM, Andersen MH. The immune checkpoint regulator PD-L1 is a specific target for naturally occurring CD4+ T cells. Oncoimmunology. 2013;2:e23991. doi: 10.4161/onci.23991. PMID:23734334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Munir S, Andersen GH, Woetmann A, Odum N, Becker JC, Andersen MH. Cutaneous T cell lymphoma cells are targets for immune checkpoint ligand PD-L1-specific, cytotoxic T cells. Leukemia. 2013;27:2251–2253. doi: 10.1038/leu.2013.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Met O, Balslev E, Flyger H, Svane IM. High immunogenic potential of p53 mRNA-transfected dendritic cells in patients with primary breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2011;125:395–406. doi: 10.1007/s10549-010-0844-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Moodie Z, Price L, Janetzki S, Britten CM. Response determination criteria for ELISPOT: toward a standard that can be applied across laboratories. Methods Mol Biol. 2012;792:185–196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.