Abstract

Systemically administered 2′-O-methoxyethyl (2′MOE) antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) accumulate in the kidney and metabolites are cleared in urine. The effects of eleven 2′MOE ASOs on renal function were assessed in 2,435 patients from 32 phase 2 and phase 3 trials. The principle analysis was on data from 28 randomized placebo-controlled trials. Mean levels of renal parameters remained within normal ranges over time across dose groups. Patient-level meta-analyses demonstrated a significant difference between placebo-treated and 2′MOE ASO-treated patients at doses >175 mg/week in the percentage and absolute change from baseline for serum creatinine and estimated glomerular filtration rate. However, these changes were not clinically significant or progressive. No dose-related effects were observed in the incidence of abnormal renal test results in the total population of patients, or subpopulation of diabetic patients or patients with renal dysfunction at baseline. The incidence of acute kidney injury [serum creatinine ≥0.3 mg/dL (26.5 μM) increases from baseline or ≥1.5 × baseline] in 2′MOE ASO-treated patients (2.4%) was not statistically different from placebo (1.7%, P = 0.411). In conclusion, in this database, encompassing 32 clinical trials and 11 different 2′MOE ASOs, we found no evidence of clinically significant renal dysfunction up to 52 weeks of randomized-controlled treatment.

Keywords: : antisense, oligonucleotide, kidney, safety, clinical trials, humans

Introduction

2′-O-methoxyethyl (2′MOE) antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs) are the most thoroughly evaluated chemical and mechanistic class of RNA-targeted therapeutics [1–5]. Two 2′MOE ASOs, mipomersen, administered systemically and nusinersen, administered intrathecally, have been approved for commercial use, and two other 2′MOE ASOs are completing phase 3 evaluation [6]. Because of the shared chemical properties between each member of a chemical class differing only in sequence, members of the same chemical class share similar biological properties (for review see Crooke [1]). We have, therefore, constructed databases that integrate all the safety findings in nonhuman primates (NHPs) and human clinical trials for each chemical class we are developing. A previous publication examined the general side effect profiles of 2′MOE ASOs in NHPs and human normal volunteer studies [7]. A second publication evaluated the effects of 2′MOE ASOs on number of platelets in completed clinical trials and those with unblinded locked data from analysis of primary end points [8].

For 2′MOE ASOs, the kidney is an organ of particular interest, because after a systemic dose, the kidney accumulates the highest concentration of the 2′MOE ASOs [3]. Accumulation of 2′MOE ASOs and metabolites in the renal cortex is first order and saturates, so long-term treatment does not result in significant increases in concentrations [4]. Furthermore, in toxicological studies performed at high doses in NHPs, vacuolization of proximal convoluted tubule cells and very mild tubular cellular degeneration were observed [5]. Finally, urinary excretion of metabolites is a major mechanism of clearance [3].

Insights into the ability of routine tests to identify changes in renal function can be obtained from ISIS 388626, a 12-mer 2′MOE ASO that targets human sodium glucose cotransporter 2. ISIS 388626 was designed to accumulate a higher fraction of a dose in the kidney than a 20-mer 2′MOE ASO. Indeed, in animals this was proven to be the case [9]. In NHPs, ISIS 388626 resulted in dose-dependent glycosuria as intended, but also an increase in serum creatinine levels [10]. Similar observations were made in normal human volunteers [10,11]. Importantly, in the context of the current report, this trial demonstrates that a decrease in renal function is observable by routine monitoring of serum creatinine even in small trials.

We have previously reported results of the effects of 2′MOE ASOs on renal function in normal human volunteers enrolled in phase 1 trials [7]. In that analysis, we found no evidence of drug-associated effects on renal function. In this report, we focus on effects of 2′MOE ASOs on renal function in completed phase 2 and phase 3 trials, and two patient subpopulations at greater risk for kidney injury, diabetes, and patients who had renal dysfunction at baseline. Since the time of the analyses on the effects of 2′MOE ASOs on platelets [8], additional trials have been completed and added to the database for inclusion in the current renal analysis. Moreover, in a recently completed phase 3 trial of the 2′MOE ASO, inotersen, in patients with transthyretin (TTR) amyloidosis and associated renal dysfunction due to amyloid accumulation, we observed evidence that inotersen administered at a dose of 300 mg/week clinically worsened kidney function in a few patients [12]. Although results from this trial are not yet available for inclusion in the current analyses, a thorough analysis will be presented elsewhere. Nevertheless, these preliminary observations emphasize both the importance of examining the effects of the 2′MOE class of agents and the potential limitations of the database in predicting results in a specific patient population with a specific ASO of a specific sequence.

Materials and Methods

Data collected from 2,435 patients enrolled in 32 phase 2 and phase 3 trials treated with 11 unique 2′MOE ASOs were analyzed (Tables 1 and 2). All data are from completed trials, or from trials that have been unblinded and locked for interim analysis. Data collected from oncology trials were excluded from the analyses since the large majority of cancer patients were treated with a 2′MOE ASO in combination with cytotoxic agents, and no trials were placebo controlled.

Table 1.

Sequences of 2′-O-Methoxyethyl Antisense Oligonucleotides Studied

| No. | Sequence (5'3')a | Target | Trialsb | ASO, N | Total, N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 104838 | GCTGATTAGAGAGAGGTCCC | TNFA | 2 | 143 | 196 |

| 113715 | GCTCCTTCCACTGATCCTGC | PTP1B | 4 | 137 | 197 |

| 301012 | GCCTCAGTCTGCTTCGCACC | APOB | 13 | 814 | 1103 |

| 304801 | AGCTTCTTGTCCAGCTTTAT | APOCIII | 4 | 182 | 283 |

| 329993 | AGCATAGTTAACGAGCTCCC | CRP | 1 | 39 | 51 |

| 404173 | AATGGTTTATTCCATGGCCA | PTP1B | 1 | 62 | 92 |

| 416858 | ACGGCATTGGTGCACAGTTT | FXI | 1 | 228 | 228 |

| 426115 | GCAGCCATGGTGATCAGGAG | GCCR | 1 | 25 | 38 |

| 449884 | GGTTCCCGAGGTGCCCA | GCGR | 3 | 111 | 169 |

| 463588 | GCACACTCAGCAGGACCCCC | FGFR4 | 1 | 11 | 14 |

| 494372 | TGCTCCGTTGGTGCTTGTTC | APO(a) | 1 | 35 | 64 |

| Total | 11 | 10 | 32 | 1787 | 2435 |

2′MOE ASOs were phosphorothioate modified and all cytosine (C) residues were methylated at the five position. Underline indicates 2′MOE-modified sugar residues.

Phase 2 and phase 3 trials only.

ASOs, antisense oligonucleotides; 2′MOE, 2′-O-methoxyethyl.

Table 2.

Types of Trials

| Phase 2 | Phase 3 | Total, systemic | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Count, N | Trials | Patients | Trials | Patients | ASOs | Trials | Patients |

| RCT | 21 | 1,147 | 7 | 879 | 10 | 28 | 2,026 |

| OL | 2 | 244a | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 244 |

| OLE | 1 | 22 | 1 | 143 | 1 | 2 | 165 |

| Total | 24 | 1,413 | 8 | 1,022 | 11 | 32 | 2,435 |

Includes three patients from open-label cohort of an RCT.

OL, open label; OLE, open-label extension; RCT, randomized placebo-controlled trial.

Clinical studies were performed in compliance with the guidelines of Good Clinical Practice and Declaration of Helsinki. All human subjects gave written informed consent.

Study populations analyzed included patients who participated in randomized placebo-controlled phase 2 and phase 3 trials and the respective subpopulation of patients diagnosed with diabetes, defined as those who had baseline HbA1c ≥6.5% or on-study usage of a concomitant medication indicated for diabetes. Patients with renal dysfunction at entry, defined as those who had abnormal values in both serum creatinine (>upper limit of normal [>ULN]) and the estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR <90 mL/min per 1.73 m2) at baseline, were excluded from these study populations and analyzed separately. Data from open-label trials, including longer term extension trials, were also assessed separately.

Measures of renal function

Standardized laboratory tests were utilized as markers of renal function, and included serum creatinine, blood urea nitrogen (BUN), eGFR, serum albumin, serum electrolytes, and urine blood and protein. Assessments of data were based on the incidence of confirmed abnormal or clinically meaningful events, and the mean results by dose and exposure. An abnormal event was defined as data falling outside of the normal range (either lower limit of normal [LLN] or ULN) and/or an event meeting criteria established in the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE, version 4.03) for scientific analyses and reporting [13]. The six-variable modification of diet in renal disease (MDRD) equation was used for calculation of eGFR [14]. This equation is based on serum creatinine, BUN, serum albumin, age, sex, and race.

Statistical analysis

Data are presented by the incidence of events and descriptive summary statistics of test results. Evaluated subjects received at least one dose of study drug. Analyses on the incidence of events were based on confirmed test results. A confirmed event was defined as a consecutive (next) abnormal laboratory value after the initial observation. If there was no consecutive test to confirm, then the initial observation was presumed confirmed. Worst confirmed category is reported for each patient in categorical tabulations and shift tables. The percentage was calculated based on the available data. Baseline was defined as the last value before the first dose. The Fisher's exact test was used to determine significant differences in the incidence of renal events between placebo and ASO-treated patients.

A meta-analysis using subject-level data was performed to investigate the relationship between dose and change in the renal laboratory test results in the randomized placebo-controlled trials (RCTs). The meta-analysis was limited to values collected during the treatment period, defined as the period from first dose to last dose plus 10 days. The end points evaluated were the percentage change and absolute change from baseline using the last nonmissing value in the treatment period. Two comparisons were performed for each end point. The first comparison investigated the relationship between the separate 2′MOE ASO doses (>0–75, >75–175, >175–275, >275–375, and >375–475 mg/week) and placebo. The second comparison investigated adjacent 2′MOE ASO doses (eg, >0–75 mg/week vs. placebo, >75–175 mg/week vs. >0–75 mg/week). The difference in the average change (percentage or absolute) between a 2′MOE ASO dose and placebo or the adjacent 2′MOE ASO dose was estimated using an analysis of covariance model, with dose, trial, and baseline level as independent variables in the model.

Results

Overall analysis plan

Tables 1 and 2 show the 2′MOE ASOs and types of trials included in the current analysis, and Table 3 shows the disease indications with respective targets and range of 2′MOE ASO doses and duration of treatment. We excluded data from trials in patients with cancer from this analysis because these studies are not placebo controlled and most are in combination with cytotoxic drugs. Since the last publication of the results of this database [8], we have added randomized placebo-controlled data from two phase 2 trials for ISIS 449884 (N = 94), one phase 2 trial for ISIS 463588 (N = 14), and from two phase 3 trials on volanesorsen (N = 178). To effectively assess dose-dependent effects on renal function, the principle analysis for this investigation was on data collected from 28 randomized placebo-controlled phase 2 and phase 3 trials on 10 unique 2′MOE ASOs. Separate analyses were performed on data collected from two open-label phase 2 trials on two 2′MOE ASOs, and two longer term open-label extension trials on one 2′MOE ASO.

Table 3.

Disease Indications Studied in Phase 2 and Phase 3 Trials on 2′-O-Methoxyethyl Antisense Oligonucleotides

| Indication | Targets | ASO doses (mg/week) | Treatment (weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hyperlipidemia | APOB | 30–400 | 5–52a |

| APOCIII | |||

| APO(a) | |||

| Diabetes/obesity | PTP1B | 50–600 | 4–26 |

| GCCR | |||

| GCGR | |||

| FGFR4 | |||

| APOCIII | |||

| Thrombosis | FXI | 100–300 | 6–12 |

| Inflammation/autoimmune | CRP | 100–400 | 4–13 |

| TNFA |

Treatment up to a total of 264 weeks with open-label extension.

Demographics

The overall demographics of the entire randomized placebo-controlled population for this renal analysis shows a distribution consistent with participation in phase 2 and phase 3 clinical trials (Table 4 and Supplementary Table S1; Supplementary Data are available online at www.liebertpub.com/nat). The mean age was ∼54 years old, with a nearly equal distribution of male and female patients and a preponderance of white patients, but with the representation of other races. The mean body mass index was within the expected range for the age of patients. In contrast, patients with diabetes were heavier and differed in other parameters (Table 4). As indicated in the methods, patients with abnormal renal function at entry were analyzed separately. Their demographic characteristics are also shown in Table 4.

Table 4.

Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics of Randomized Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 or Phase 3 Population Minus Patients with Renal Dysfunction at Baseline (N = 2,008), Subpopulation of Patients with Diabetes Minus Patients with Renal Dysfunction at Baseline (N = 733), and Subpopulation of Patients with Renal Dysfunction at Baseline (N = 18)

| Phase 2 or phase 3a | Diabetic patientsa | Renal dysfunction at baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N = 642) | ASO total (N = 1,366) | Placebo (N = 235) | ASO total (N = 498) | Placebo (N = 6) | ASO total (N = 12) | |

| Age, years | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 54 (11) | 54 (11) | 57 (9) | 56 (9) | 63 (6) | 64 (9) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||||||

| Female | 324 (50.5) | 717 (52.5) | 127 (54.0) | 280 (56.2) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (25.0) |

| Male | 318 (49.5) | 649 (47.5) | 108 (46.0) | 218 (43.8) | 4 (66.7) | 9 (75.0) |

| Race, n (%) | ||||||

| White | 543 (84.6) | 1,158 (84.8) | 184 (78.3) | 388 (77.9) | 4 (66.7) | 9 (75.0) |

| Black | 60 (9.3) | 108 (7.9) | 42 (17.9) | 73 (14.7) | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| Asian | 21 (3.3) | 48 (3.5) | 5 (2.1) | 14 (2.8) | 0 | 2 (16.7) |

| Hispanic | 5 (0.8) | 16 (1.2) | 1 (0.4) | 4 (0.8) | 1 (16.7) | 0 |

| Other | 13 (2.0) | 35 (2.6) | 3 (1.3) | 19 (3.8) | 1 (16.7) | 0 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ||||||

| Mean (SD) | 29.6 (5.1) | 29.8 (5.6) | 31.4 (5.0) | 31.9 (5.2) | 28.7 (5.3) | 29.1 (4.3) |

Excludes patients with renal dysfunction at baseline.

BMI, body mass index.

Baseline renal characteristics

Table 5 shows that, by design, patients enrolled in the randomized placebo-controlled phase 2 or phase 3 population entered with normal renal function. This was also true for patients with diabetes. However, as expected, patients identified with abnormal renal function at entry showed a distinct baseline profile. For a tabulated summary of baseline renal characteristics by dose group, see Supplementary Table S2.

Table 5.

Baseline Renal Characteristics of the Randomized Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 or Phase 3 Population Minus Patients with Renal Dysfunction at Baseline (N = 2,008), the Subpopulation of Patients with Diabetes Minus Patients with Renal Dysfunction at Baseline (N = 733), and the Subpopulation of Patients with Renal Dysfunction at Baseline (N = 18)

| Phase 2 or phase 3a | Diabetic patientsa | Renal dysfunction at baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N = 642) | Total ASO (N = 1,366) | Placebo (N = 235) | Total ASO (N = 498) | Placebo (N = 6) | Total ASO (N = 12) | |

| Creatinine (mg/dL) | ||||||

| n | 637 | 1,344 | 233 | 496 | 6 | 12 |

| Mean | 0.82 | 0.81 | 0.80 | 0.78 | 1.67 | 1.55 |

| SD, SEM | 0.18, 0.01 | 0.18, 0.01 | 0.19, 0.01 | 0.18, 0.01 | 0.67, 0.27 | 0.18, 0.05 |

| Mean 95% CI | 0.81, 0.84 | 0.80, 0.82 | 0.78, 0.83 | 0.76, 0.79 | 0.97, 2.37 | 1.43, 1.66 |

| eGFR (mL/min per 1.73 m2) | ||||||

| n | 637 | 1,343 | 233 | 496 | 6 | 12 |

| Mean | 97.8 | 98.4 | 99.5 | 102.4 | 45.3 | 46.6 |

| SD, SEM | 23.2, 0.9 | 23.6, 0.6 | 23.9, 1.6 | 25.4, 1.1 | 15.8, 6.4 | 12.6, 3.6 |

| Mean 95% CI | 96.0, 99.6 | 97.1, 99.7 | 96.4, 102.5 | 100.2, 104.7 | 28.8, 61.9 | 38.6, 54.5 |

| BUN (mg/dL) | ||||||

| n | 637 | 1,344 | 233 | 496 | 6 | 12 |

| Mean | 15.2 | 15.0 | 15.3 | 15.0 | 30.9 | 31.5 |

| SD, SEM | 4.5, 0.2 | 4.4, 0.1 | 4.8, 0.3 | 4.6, 0.2 | 14.5, 5.9 | 12.6, 3.6 |

| Mean 95% CI | 14.9, 15.6 | 14.7, 15.2 | 14.7, 16.0 | 14.6, 15.4 | 15.7, 46.1 | 23.5, 39.5 |

| Albumin | ||||||

| n | 637 | 1,344 | 233 | 496 | 6 | 12 |

| Mean | 4.5 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.4 | 4.1 | 4.2 |

| SD, SEM | 0.4, 0.0 | 0.4, 0.0 | 0.3, 0.0 | 0.4, 0.0 | 0.4, 0.1 | 0.5, 0.2 |

| Mean 95% CI | 4.4, 4.5 | 4.4, 4.5 | 4.4, 4.5 | 4.4, 4.5 | 3.7, 4.5 | 3.9, 4.6 |

| Potassium (mEq/L) | ||||||

| n | 636 | 1,339 | 233 | 496 | 6 | 12 |

| Mean | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 | 4.3 |

| SD, SEM | 0.4, 0.0 | 0.4, 0.0 | 0.5, 0.0 | 0.4, 0.0 | 0.4, 0.2 | 0.5, 0.2 |

| Mean 95% CI | 4.3, 4.3 | 4.3, 4.3 | 4.3, 4.4 | 4.3, 4.3 | 3.9, 4.7 | 4.0, 4.7 |

| Sodium (mEq/L) | ||||||

| n | 637 | 1,344 | 233 | 496 | 6 | 12 |

| Mean | 139.6 | 139.5 | 139.2 | 139.0 | 141.2 | 140.1 |

| SD, SEM | 2.9, 0.1 | 2.8, 0.1 | 3.5, 0.2 | 3.2, 0.1 | 2.6, 1.0 | 2.4, 0.7 |

| Mean 95% CI | 139.4, 139.8 | 139.3, 139.6 | 138.7, 139.6 | 138.7, 139.3 | 138.5, 143.9 | 138.6, 141.6 |

| Bicarbonate (mEq/L) | ||||||

| n | 637 | 1,344 | 233 | 496 | 6 | 12 |

| Mean | 25.4 | 25.2 | 24.6 | 24.6 | 24.3 | 24.8 |

| SD, SEM | 3.5, 0.1 | 3.4, 0.1 | 3.4, 0.2 | 3.3, 0.1 | 4.2, 1.7 | 3.1, 0.9 |

| Mean 95% CI | 25.1, 25.7 | 25.0, 25.4 | 24.2, 25.0 | 24.3, 24.8 | 19.9, 28.6 | 22.8, 26.7 |

| Chloride (mEq/L) | ||||||

| n | 637 | 1,344 | 233 | 496 | 6 | 12 |

| Mean | 103.7 | 103.8 | 103.2 | 103.0 | 105.5 | 104.8 |

| SD, SEM | 2.9, 0.1 | 3.2, 0.1 | 3.2, 0.2 | 3.5, 0.2 | 3.0, 1.2 | 3.6, 1.1 |

| Mean 95% CI | 103.5, 103.9 | 103.6, 103.9 | 102.8, 103.6 | 102.7, 103.3 | 102.3, 108.7 | 102.4, 107.1 |

Excludes patients with renal dysfunction at baseline.

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CI, confidence interval; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; SD, standard deviation; SEM, standard error of the mean.

Concomitant medications

Table 6 shows the usage of various concomitantly administered agents considered potentially nephrotoxic [15,16] across dose groups. The incidence of concurrent usage of two or more concomitant medications that have been reported to have a higher risk of renal injury when taken at the same time was ∼10% in the phase 2 or phase 3 RCT population with an increase in usage to ∼14% in the subpopulation of patients with diabetes.

Table 6.

Use of Concomitant Medications with Potential for Nephrotoxicity [13,14], (A) Duration >7 to 28 Days, (B) Duration >28 Days, and (C) Concurrent Use of 2 or More Specified Drug Classes with Potential for Nephrotoxicity by Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial Study Population

| Phase 2 or phase 3a | Diabetic patientsa | Renal dysfunction at baseline | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | Placebo (N = 642) | ASO total (N = 1,366) | Placebo (N = 235) | ASO total (N = 498) | Placebo (N = 6) | ASO total (N = 12) |

| (A) Duration >7 to 28 days | ||||||

| Patients on potentially nephrotoxic CMs | 156 (24.3) | 336 (24.6) | 46 (19.6) | 107 (21.5) | 0 | 4 (33.3) |

| Antibacterials for systemic useb,c | 81 (12.6) | 141 (10.3) | 27 (11.5) | 53 (10.6) | 0 | 2 (16.7) |

| Beta-lactamsb | 52 (8.1) | 90 (6.6) | 17 (7.2) | 33 (6.6) | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| Ciprofloxacinb,c | 11 (1.7) | 25 (1.8) | 4 (1.7) | 11 (2.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Sulfonamidesb,c | 10 (1.6) | 17 (1.2) | 6 (2.6) | 11 (2.2) | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| Aminoglycosidesc | 0 | 2 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Analgesicsb,d,e | 34 (5.3) | 91 (6.7) | 9 (3.8) | 32 (6.4) | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| Anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic productsb,d,e | 27 (4.2) | 72 (5.3) | 6 (2.6) | 25 (5.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Oxicamsb,e | 3 (0.5) | 7 (0.5) | 1 (0.4) | 6 (1.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Lipid-modifying agentsf | 6 (0.9) | 25 (1.8) | 1 (0.4) | 5 (1.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Drugs for acid-related disordersb | 15 (2.3) | 22 (1.6) | 2 (0.9) | 3 (0.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Agents acting on the renin–angiotensin systemd | 12 (1.9) | 21 (1.5) | 4 (1.7) | 9 (1.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Antithrombotic agentsg | 10 (1.6) | 21 (1.5) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| Psychoanalepticse,f | 5 (0.8) | 12 (0.9) | 0 | 5 (1.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Antihistamines for systemic usef | 3 (0.5) | 9 (0.7) | 1 (0.4) | 3 (0.6) | 0 | 0 |

| Diureticsb | 3 (0.5) | 9 (0.7) | 2 (0.9) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| Antivirals for systemic usec | 1 (0.2) | 5 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 0 |

| Antimycotics for systemic usec | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Antiepilepticsb | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Drugs for treatment of bone diseasec,e | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Bisphosphonates, IVc | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antimycobacterialsb | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antigout preparationsb | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antiprotozoalsc | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Immunosuppressantsb,e | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Psycholepticsb,f | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (B) Duration >28 days | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients on potentially nephrotoxic CMs | 523 (81.5) | 1,125 (82.4) | 173 (73.6) | 380 (76.3) | 6 (100.0) | 12 (100.0) |

| Lipid-modifying agentsf | 331 (51.6) | 718 (52.6) | 91 (38.7) | 204 (41.0) | 4 (66.7) | 8 (66.7) |

| Agents acting on the renin–angiotensin systemd | 243 (37.9) | 471 (34.5) | 112 (47.7) | 242 (48.6) | 5 (83.3) | 5 (41.7) |

| Antithrombotic agentsg | 261 (40.7) | 516 (37.8) | 75 (31.9) | 150 (30.1) | 2 (33.3) | 7 (58.3) |

| Drugs for acid-related disordersb | 137 (21.3) | 265 (19.4) | 31 (13.2) | 70 (14.1) | 1 (16.7) | 3 (25.0) |

| Analgesicsb,d,e | 139 (21.7) | 331 (24.2) | 29 (12.3) | 68 (13.7) | 1 (16.7) | 4 (33.3) |

| Anti-inflammatory and antirheumatic productsb,d,e | 102 (15.9) | 229 (16.8) | 24 (10.2) | 52 (10.4) | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| Oxicamsb,e | 10 (1.6) | 31 (2.3) | 3 (1.3) | 7 (1.4) | 0 | 0 |

| Diureticsb | 95 (14.8) | 172 (12.6) | 49 (20.9) | 79 (15.9) | 2 (33.3) | 3 (25.0) |

| Psychoanalepticsf,e | 65 (10.1) | 123 (9.0) | 18 (7.7) | 32 (6.4) | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| Drugs for treatment of bone diseasec,e | 10 (1.6) | 29 (2.1) | 0 | 6 (1.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Bisphosphonates, IVc | 0 | 2 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antigout preparationsb | 16 (2.5) | 20 (1.5) | 6 (2.6) | 7 (1.4) | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| Antihistamines for systemic usef | 4 (0.6) | 16 (1.2) | 1 (0.4) | 4 (0.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Antibacterials for systemic useb,c | 7 (1.1) | 15 (1.1) | 2 (0.9) | 5 (1.0) | 0 | 0 |

| Beta-lactamsb | 0 | 8 (0.6) | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 0 |

| Ciprofloxacinb,c | 2 (0.3) | 5 (0.4) | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 0 |

| Sulfonamidesb,c | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.1) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Aminoglycosidesc | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antivirals for systemic usec | 6 (0.9) | 6 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Psycholepticsb,f | 0 | 2 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 |

| Antiepilepticsb | 0 | 2 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antiprotozoalsc | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Immunosuppressantsb,e | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antimycobacterialsb | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Antimycotics for systemic usec | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| (C) Concurrent usage | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients on potentially nephrotoxic CMs | 72 (11.2) | 135 (9.9) | 37 (15.7) | 63 (12.7) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (8.3) |

| ARB/ACE inhibitors and diuretics | 63 (9.8) | 115 (8.4) | 34 (14.5) | 52 (10.4) | 2 (33.3) | 1 (8.3) |

| ARB/ACE inhibitors and oxicams | 4 (0.6) | 16 (1.2) | 1 (0.4) | 9 (1.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Diuretics and oxicams | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 0 |

| ARB/ACE inhibitors, diuretics, and oxicamsh | 4 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | 2 (0.9) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Incidence of usage by dose group for phase 2 or phase 3 RCT population is shown in Supplementary Table S3.

Excludes patients with renal dysfunction at baseline.

Mechanism of injury: binterstitial nephritis; ctubular injury; dhemodynamic insult; ealtered intraglomerular hemodynamics; frhabdomyolysis; and gvascular injury.

Patients with concurrent use of all three of the indicated concomitant medications were not counted in categories for concurrent usage of two.

ACE/ARB, angiotensin-converting enzyme/angiotensin II receptor blocker; CM, concomitant medication.

Renal laboratory tests

Randomized placebo-controlled phase 2 or phase 3 population

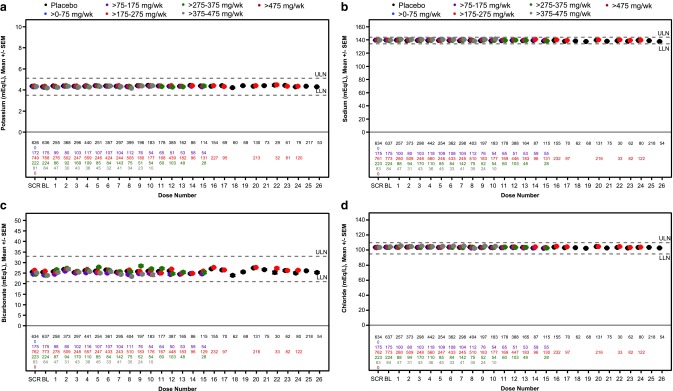

In Figs. 1 and 2, we show the variations in serum creatinine, eGFR, BUN, serum albumin, and serum electrolytes by dose group in the phase 2 or phase 3 patient population as a function of number of doses. An increase in the mean serum creatinine level and decrease in the mean eGFR were observed at doses >275 mg/week. In the patient-level meta-analysis, both the percentage change and absolute change from baseline in serum creatinine and eGFR levels at end of treatment were significantly different between placebo-treated patients and 2′MOE ASO-treated patients administered doses >175 mg/week (Supplementary Table S7 and S8). However, the effects were minimal and the means remained in the normal range. The incidence of abnormal values in renal analytes is shown in Table 7 and demonstrates that there were no dose-dependent effects on serum analytes including electrolytes. Nor were there effects on urine character or composition that could be discerned. The incidence of acute kidney injury (AKI), defined as either serum creatinine ≥0.3 mg/dL (26.5 μM) increase from baseline or ≥1.5 × baseline in patients treated with 2′MOE ASOs (2.4%), was not statistically different compared with placebo (1.7%, P = 0.411). As might be expected, the incidence of creatinine and eGFR events in the total phase 2 or phase 3 RCT population was numerically greater in patients reporting usage of potentially nephrotoxic agents than in patients not reporting usage of these agents (Supplementary Table S9). However, differences in incidence between 2′MOE ASO-treated patients and placebo were not significant, either with or without usage of these concomitant medications.

FIG. 1.

Serum chemistry test results from subjects treated up to 26 weeks with multiple doses of study drug in phase 2 and phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trials. Mean ± SEM by dose group for (a) serum creatinine, (b) eGFR, (c) BUN, and (d) albumin. Each data point represents data from at least three ASOs and 10 patients. See Supplementary Table S4 for reference range values and Supplementary Table S5 for a tabulated summary of results shown. ASOs, antisense oligonucleotides; BUN, blood urea nitrogen; eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; SEM, standard error of the mean.

FIG. 2.

Serum electrolyte test results from subjects treated up to 26 weeks with multiple doses of study drug in phase 2 and phase 3 randomized placebo-controlled trials. Mean ± SEM by dose group for (a) potassium, (b) sodium, (c) bicarbonate, and (d) chloride. Each data point represents data from at least three ASOs and 10 patients. See Supplementary Table S4 for reference range values and Supplementary Table S6 for a tabulated summary of results shown.

Table 7.

Incidence of Abnormal Renal Test Results in Randomized Placebo-Controlled Phase 2 or Phase 3 Population by Dose Group

| Phase 2 or phase 3 RCT | 2′MOE ASO dose (mg/week) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event, n (%), confirmeda | Placebo (N = 642) | Total ASO (N = 1,366) | >0–75 (N = 76) | >75–175 (N = 175) | >175–275 (N = 793) | >275–375 (N = 225) | >375–475 (N = 85) | >475 (N = 12) |

| Serum chemistries | ||||||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL), n | 637 | 1,344 | 76 | 175 | 773 | 224 | 84 | 12 |

| ≥0.3 mg/dL (26.5 μM) increase from baseline or ≥1.5 × baseline | 11 (1.7) | 32 (2.4) | 2 (2.6) | 3 (1.7) | 20 (2.6) | 5 (2.2) | 2 (2.4) | 0 |

| ≥2 × baseline | 0 | 1 (0.1)b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.2)b | 0 |

| eGFR (mL/min per 1.73 m2), n | 637 | 1,343 | 76 | 175 | 772 | 224 | 84 | 12 |

| <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 22 (3.5) | 62 (4.6) | 2 (2.6) | 4 (2.3) | 43 (5.6) | 9 (4.0) | 4 (4.8) | 0 |

| <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BUN (mg/dL), n | 637 | 1,344 | 76 | 175 | 773 | 224 | 84 | 12 |

| ≥2 × ULN or baseline if >ULN | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 0 |

| Albumin (g/dL), n | 637 | 1,344 | 76 | 175 | 773 | 224 | 84 | 12 |

| <LLN, or baseline if <LLN | 4 (0.6) | 8 (0.6) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 2 (0.3) | 3 (1.3) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (8.3) |

| <2.5 g/dL | 0 (0.0) | 2 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 0 |

| Serum electrolytes | ||||||||

| Potassium (mEq/L), n | 637 | 1,342 | 76 | 175 | 771 | 224 | 84 | 12 |

| <LLN or baseline if <LLN | 11 (1.7) | 17 (1.3) | 1 (1.3) | 4 (2.3) | 9 (1.2) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (2.4) | 0 |

| <3.0 mM | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 0 | 1 (1.2) | 0 |

| >ULN or baseline if >ULN | 31 (4.9) | 71 (5.3) | 11 (14.5) | 6 (3.4) | 43 (5.6) | 4 (1.8) | 3 (3.6) | 4 (33.3) |

| >5.5 mM | 5 (0.8) | 13 (1.0) | 3 (3.9) | 1 (0.6) | 7 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| Sodium (mEq/L), n | 637 | 1,344 | 76 | 175 | 773 | 224 | 84 | 12 |

| <LLN or baseline if <LLN | 33 (5.2) | 42 (3.1)* | 5 (6.6) | 2 (1.1) | 24 (3.1) | 6 (2.7) | 4 (4.8) | 1 (8.3) |

| <130 mM | 1 (0.2) | 3 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| >ULN or baseline if >ULN | 21 (3.3) | 55 (4.1) | 3 (3.9) | 8 (4.6) | 37 (4.8) | 4 (1.8) | 3 (3.6) | 0 |

| >150 mM | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.1) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.2) | 0 |

| Bicarbonate (mEq/L), n | 637 | 1,344 | 76 | 175 | 773 | 224 | 84 | 12 |

| <LLN or baseline if <LLN | 58 (9.1) | 99 (7.4) | 6 (7.9) | 23 (13.1) | 32 (4.1) | 19 (8.5) | 18 (21.4) | 1 (8.3) |

| Chloride (mEq/L), n | 637 | 1,344 | 76 | 175 | 773 | 224 | 84 | 12 |

| <LLN or baseline if <LLN | 9 (1.4) | 22 (1.6) | 0 | 5 (2.9) | 7 (0.9) | 5 (2.2) | 4 (4.8) | 1 (8.3) |

| >ULN or baseline if >ULN | 13 (2.0) | 46 (3.4) | 5 (6.6) | 8 (4.6) | 17 (2.2) | 10 (4.5) | 5 (6.0) | 1 (8.3) |

| Urine | ||||||||

| Blood, n | 636 | 1,338 | 76 | 175 | 772 | 220 | 83 | 12 |

| 2+ or ≥0.2 mg/dL or ≥2 mg/L | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.2) | 0 |

| 3+ or ≥1.0 mg/dL or ≥10 mg/L | 2 (0.3) | 4 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.5) | 1 (1.2) | 0 |

| Protein, n | 636 | 1,338 | 76 | 175 | 772 | 220 | 83 | 12 |

| 1+ or ≥30 mg/dL or ≥0.3 g/L | 51 (8.0) | 143 (10.7) | 10 (13.2) | 12 (6.9) | 88 (11.4) | 24 (10.9) | 9 (10.8) | 0 |

| 2+ or ≥100 mg/dL or ≥1 g/L | 9 (1.4) | 22 (1.6) | 2 (2.6) | 3 (1.7) | 13 (1.7) | 4 (1.8) | 0 | 0 |

| 3+ or ≥300 mg/dL or ≥3 g/L | 1 (0.2) | 4 (0.3) | 0 | 0 | 4 (0.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Confirmed event is defined as a consecutive abnormal laboratory value on next measurement after the initial observation. If there is no consecutive test to confirm, then the initial observation is presumed confirmed.

Patient postbaseline creatinine event was within the range of normal at 0.78 mg/dL.

P < 0.05, Fisher's exact test.

LLN, lower limit of normal; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Diabetes subpopulation

The diabetes subpopulation was treated with nine different 2′MOE ASOs with data from a total of 23 trials. As expected, the incidence of abnormal renal events was numerically higher in patients with diabetes (Table 8). Nevertheless, despite the presence of diabetes, no dose-related increases in the incidence of abnormal values or values that were greater than twofold different from baseline were apparent. Nor were there dose-related changes in urine composition. The incidence of AKI, defined as either serum creatinine ≥0.3 mg/dL (26.5 μM) increase from baseline or ≥1.5 × baseline in patients with diabetes treated with 2′MOE ASOs (3.8%), was not statistically different compared with placebo (2.6%, P = 0.514). Similar to the total randomized placebo-controlled population, an increase in the mean serum creatinine level and decrease in the mean eGFR were observed at doses >275 mg/week (Supplementary Figs. S1 and S2). However, the experience at doses >375 mg/week is limited, and only 66 patients have been exposed to >275–375 mg/week.

Table 8.

Incidence of Abnormal Renal Test Results in Patients with Diabetes from Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials by Dose Group

| Diabetic patients | 2′MOE ASO dose (mg/week) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Event, n (%), confirmeda | Placebo (N = 235) | Total ASO (N = 498) | >0–75 (N = 52) | >75–175 (N = 75) | >175–275 (N = 274) | >275–375 (N = 66) | >375–475 (N = 19) | >475 (N = 12) |

| Serum chemistries | ||||||||

| Creatinine (mg/dL), n | 233 | 496 | 52 | 75 | 272 | 66 | 19 | 12 |

| ≥0.3 mg/dL (26.5 μM) increase from baseline or ≥1.5 × baseline | 6 (2.6) | 19 (3.8) | 2 (3.8) | 1 (1.3) | 13 (4.8) | 2 (3.0) | 1 (5.3) | 0 |

| ≥2 × baseline | 0 | 1 (0.2)b | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.3)b | 0 |

| eGFR (mL/min per 1.73 m2), n | 233 | 496 | 52 | 75 | 272 | 66 | 19 | 12 |

| <60 mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 13 (5.6) | 22 (4.4) | 2 (3.8) | 0 | 16 (5.9) | 3 (4.5) | 1 (5.3) | 0 |

| <30 mL/min per 1.73 m2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| BUN (mg/dL), n | 233 | 496 | 52 | 75 | 272 | 66 | 19 | 12 |

| ≥2 × ULN or baseline if >ULN | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Albumin (g/dL), n | 233 | 496 | 52 | 75 | 272 | 66 | 19 | 12 |

| <LLN or baseline if <LLN | 3 (1.3) | 3 (0.6) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| <2.5 g/dL | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.3) | 0 |

| Serum electrolytes | ||||||||

| Potassium (mEq/L), n | 233 | 496 | 52 | 75 | 272 | 66 | 19 | 12 |

| <LLN or baseline if <LLN | 4 (1.7) | 7 (1.4) | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 5 (1.8) | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 0 |

| <3.0 mM | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 0 | 1 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 0 |

| >ULN or baseline if >ULN | 16 (6.9) | 43 (8.7) | 10 (19.2) | 4 (5.3) | 21 (7.7) | 1 (1.5) | 3 (15.8) | 4 (33.3) |

| >5.5 mM | 4 (1.7) | 7 (1.4) | 3 (5.8) | 0 | 3 (1.1) | 0 | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| Sodium (mEq/L), n | 233 | 496 | 52 | 75 | 272 | 66 | 19 | 12 |

| <LLN or baseline if <LLN | 23 (9.9) | 23 (4.6)* | 5 (9.6) | 0 | 13 (4.8) | 3 (4.5) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (8.3) |

| <130 mM | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| >ULN or baseline if >ULN | 12 (5.2) | 18 (3.6) | 1 (1.9) | 7 (9.3) | 9 (3.3) | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 0 |

| >150 mM | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (5.3) | 0 |

| Bicarbonate (mEq/L), n | 233 | 496 | 52 | 75 | 272 | 66 | 19 | 12 |

| <LLN or baseline if <LLN | 11 (4.7) | 29 (5.8) | 3 (5.8) | 2 (2.7) | 14 (5.1) | 6 (9.1) | 3 (15.8) | 1 (8.3) |

| Chloride (mEq/L), n | 233 | 496 | 52 | 75 | 272 | 66 | 19 | 12 |

| <LLN or baseline if <LLN | 6 (2.6) | 7 (1.4) | 0 | 2 (2.7) | 1 (0.4) | 2 (3.0) | 1 (5.3) | 1 (8.3) |

| >ULN or baseline if >ULN | 5 (2.1) | 13 (2.6) | 1 (1.9) | 1 (1.3) | 4 (1.5) | 6 (9.1) | 0 | 1 (8.3) |

| Urine | ||||||||

| Blood, n | 232 | 496 | 52 | 75 | 272 | 66 | 19 | 12 |

| 2+ or ≥0.2 mg/dL or ≥2 mg/L | 0 | 2 (0.4) | 0 | 1 (1.3) | 0 | 1 (1.5) | 0 | 0 |

| 3+ or ≥1.0 mg/dL or ≥10 mg/L | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Protein, n | 232 | 496 | 52 | 75 | 272 | 66 | 19 | 12 |

| 1+ or ≥30 mg/dL or ≥0.3 g/L | 29 (12.5) | 65 (13.1) | 8 (15.4) | 9 (12.0) | 38 (14.0) | 9 (13.6) | 1 (5.3) | 0 |

| 2+ or ≥100 mg/dL or ≥1 g/L | 4 (1.7) | 8 (1.6) | 2 (3.8) | 1 (1.3) | 3 (1.1) | 2 (3.0) | 0 | 0 |

| 3+ or ≥300 mg/dL or ≥3 g/L | 1 (0.4) | 4 (0.8) | 0 | 0 | 4 (1.5) | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Confirmed event is defined as a consecutive abnormal laboratory value on next measurement after the initial observation. If there is no consecutive test to confirm, then the initial observation is presumed confirmed.

Patient postbaseline creatinine event was within the range of normal at 0.78 mg/dL.

P < 0.05, Fisher's exact test.

Patients with renal dysfunction at entry

At present, in our clinical database of 2′MOE ASOs, there are only 18 patients (6 placebo, 12 ASOs) who entered randomized placebo-controlled phase 2 or phase 3 clinical trials with abnormal renal function. The number of different ASOs studied in these patients was 4, with 8 of 12 (67%) patients exposed to only one of the 2′MOE ASOs. Thus, even preliminary conclusions about the effects of 2′MOE ASOs in this unique patient population are not possible. Nevertheless, in Tables 9–11 we show with shift analyses that there was no worsening renal function in these patients comparing their on-treatment change from baseline in the eGFR. One of 12 patients in the 2′MOE ASO-treated group experienced an increase in serum creatinine, whereas 1 of 6 patients in placebo experienced an increase in BUN.

Table 9.

Baseline to Treatment Period Laboratory Test Shift Tables for Patients from Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials with Renal Dysfunction At baseline (Creatinine)

| Treatment period, confirmed observation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Creatinine, mg/dL | Baseline | Unknown | ≤1.4 | >1.4–1.7 | >1.7–2.1 | >2.1–4.2 | >4.2 |

| Placebo (N = 6) | Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ≤1.4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| >1.4–1.7 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| >1.7–2.1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| >2.1–4.2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| >4.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total ASO (N = 12) | Unknown | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| ≤1.4 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| >1.4–1.7 | 0 | 5 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| >1.7–2.1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| >2.1–4.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| >4.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Bold values represent the middle line where no change was observed between baseline and the highest confirmed measure in the treatment period.

Table 10.

Baseline to Treatment Period Laboratory Test Shift Tables for Patients from Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials with Renal Dysfunction At Baseline (Estimated Glomerular Filtration Rate)

| Treatment period, confirmed observation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| eGFR, mL/(min ·1.73 m2) | Baseline | ≥90 | <90 to 60 | <60 to 45 | <45 to 30 | <30 to 15 | ≤15 |

| Placebo (N = 6) | ≥90 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| <90 to 60 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| <60 to 45 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| <45 to 30 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| <30 to 15 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| <15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total ASO (N = 12) | ≥90 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| <90 to 60 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| <60 to 45 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| <45 to 30 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| <30 to 15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| <15 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Bold values represent the middle line where no change was observed between baseline and the highest confirmed measure in the treatment period.

Table 11.

Baseline to Treatment Period Laboratory Test Shift Tables for Patients from Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trials with Renal Dysfunction At Baseline (Blood Urea Nitrogen)

| Treatment period, confirmed observation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BUN, mg/dL | Baseline | ≤22 | >22–31 | >31–44 | >44 |

| Placebo (N = 6) | ≤22 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| >22–31 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| >31–44 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| >44 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | |

| Total ASO (N = 12) | ≤22 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| >22–31 | 0 | 4 | 0 | 0 | |

| >31–44 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | |

| >44 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

Bold values represent the middle line where no change was observed between baseline and the highest confirmed measure in the treatment period.

Open label and longer term open-label extension trials

Although limited by the study design and scope of data available, the incidence of renal abnormalities in the open-label trials (three trials, three ASOs) was similar to the incidence observed in the randomized placebo-controlled phase 2 or phase 3 trials (Supplementary Table S10). Similarly, analysis of data from the additional two open-label extension trials for one 2′MOE ASO (with longer term treatment up to 264 weeks) did not appear to increase the incidence of abnormal renal test results compared with the randomized placebo-controlled phase 2 or phase 3 trials.

Discussion

In this third publication derived from our 2′MOE safety database, we examine the effects of treatment with 2′MOE ASOs on renal function. In 2,435 patients derived from phase 2 or phase 3 trials, we demonstrate minimal and clinically insignificant changes in measures of renal function. Importantly, there were no clinically meaningful dose-related changes in the overall population or in the subpopulation of patients with diabetes. Finally, there were no statistically significant increases in the incidence of renal events in 2′MOE ASO-treated patients compared with placebo-treated patients, including the spot urine protein test.

The major clinically relevant analysis of renal function in short- to medium-term studies such as these is AKI. Using accepted measures [13], we show that the incidence of mild, stage 1 AKI was not different between placebo and treated groups, with overall low rates. A caveat to this conclusion is that the total long-term exposure represented by our database is still modest. However, other large outcome trials with drugs that utilize renal clearance mechanisms (angiotensin-converting enzyme/angiotensin II receptor blocker [ACE/ARB] or renin inhibitors) in high-risk populations, such as diabetic patients or heart-failure patients, have higher rates of AKI [17,18].

The evaluation of mean serum creatinine and eGFR levels over time in the overall group revealed small changes that remained within the normal range. To complement this evaluation, a patient-level meta-analysis for dose effects revealed a significant difference in the 2′MOE ASO-treated patients who received >175 mg/week compared with placebo, but these differences are not considered clinically meaningful. We did not observe any significant rates of hyperkalemia or other electrolyte disturbances associated with these small changes.

A preliminary analysis of patients with renal dysfunction was also performed, but must be interpreted with extreme caution because the number of patients is small, the duration of treatment is short, and only a few 2′MOE ASOs have been studied. Thus, it is not possible to address the effects of 2′MOE ASOs on renal function in patients with various types of renal disease in the current analysis. In this regard, the phase 3 trial in patients with TTR amyloidosis (data not included in the current analysis) is important and revealing as many of these patients have progressive renal dysfunction caused by amyloid deposits in the kidney [19]. A topline analysis of that trial has shown that in patients with significant renal dysfunction due to amyloid accumulation, inotersen (IONIS-TTRRx) appeared to exacerbate renal dysfunction in a few patients [12]. Four inotersen-treated patients discontinued treatment due to a renal observation: two patients met a predefined renal stopping rule and two experienced serious renal adverse events, one of whom experienced chronic renal insufficiency. One placebo-treated patient also met a predefined renal stopping rule. Enhanced monitoring was implemented during the study to support early detection and management of these renal issues. Although conclusions about the effects on inotersen in this phase 3 trial must await a complete analysis and publication of the trial results, the topline analysis appears to demonstrate that 300 mg/week doses of inotersen can worsen renal function in some patients from a population with amyloid deposits throughout the kidney.

In contrast, data from the reported phase 2 or phase 3 volanesorsen trials in patients with elevated triglycerides and familial chylomicronemia syndrome, which do not have any direct disease-related renal effects, revealed no adverse effects on renal function or AKI. This suggests that other cofactors or comorbidities may be necessary for nephrotoxicity to be expressed or for clinical deterioration in renal function to become apparent, especially the presence of underlying renal compromise.

As the clinical experience of 2′MOE ASOs expands to larger patient cohorts with more comorbidities, it will be important to understand the relationship between the effect of this class of agents on patients already at risk for renal disease and the effect on those without any inherent disease-related risk. Future studies must also focus on evaluation of other 2′MOE ASOs in patient populations with other types of renal dysfunction, including primary renal disease, diabetes and older age.

The results of this and other analyses of the 2′MOE ASO safety database coupled to the recently reported results from phase 3 trials on volanesorsen and inotersen demonstrate the value of the database and emphasize the limitations. Information in the database supports data-based decisions on dosing and other clinical trial characteristics, and thus enhances the design and safety of trials in specific patients. However, the results from the volanesorsen and inotersen trials show that each drug at a given dose and in a given patient population may result in safety events not predicted by the experience in the safety database, emphasizing the obvious need for diligence in trials in specific patient populations. The observations also emphasize the value of continuing to add new studies in new patient populations to the safety database.

Limitations of the analysis are that in this database, the drug exposure or duration is modest in terms of time, with the longest treatment in a randomized placebo-controlled setting being 52 weeks. Second, few patients had baseline renal function or comorbidities that could predispose to renal disease. Future studies will need to address the renal effects of 2′MOEs in higher risk cohorts. Other limitations of the integrated database include heterogeneities in trial designs, for example, protocol-specified schedules for dosing and sample collection, and in the disease indications investigated for the 11 different 2′MOE ASOs. In addition, although the eGFR equation applied in this analysis accounts for several independent variables, the mean eGFR values reported are likely lower than what would be observed if measured directly [20]. Finally, with regard to long-term exposure that derives from phase 3 and open-label extension studies, the maximum dose studied is 300 mg because substantial target reduction and efficacy have been observed consistently in humans at this dose for this class of ASOs.

More recent developments have allowed specific targeting of hepatocytes for liver targets using N-acetylgalactosamine (GalNAc) moiety covalently bound to the ASO to target it to the asialoglycoprotein hepatocyte receptors, which has allowed two important developments. First, the dose required for similar target knockdown, in this case plasma Lp(a) levels, is up to 30-fold less, as exemplified in recent clinical trials using a 2′MOE ASO directed to apolipoprotein(a). Comparing the untargeted 2′MOE ASO to the GalNAc-targeted 2′MOE ASO, doses were 100–400 mg versus 10–40 mg and ED50 was 4 versus 122 mg [21,22]. Second, the nonhepatic exposure, including renal exposure, was ∼95% reduced by directing a higher proportion of the drug to the liver and the much lower dose [23,24]. Therefore, future 2′MOE ASOs that are targeted to the liver are expected to have much lower renal accumulation and presumably lower renal risk profile [25].

In conclusion, in this large database encompassing 32 clinical trials and 11 different 2′MOE ASOs, we found no major signal of renal dysfunction. This database provides a useful clinical summary to gauge 2′MOE ASO effects on renal disease and will be expanded and amplified with the completion of new analyses and new trials with this relatively new class of therapeutic compounds. Observations from the phase 3 trial on inotersen, however, emphasize both the importance of examining the effects of the 2′MOE class of agents and the potential limitations of the database in predicting results in a specific patient population with a specific ASO.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Di Yu, Doreen Chen, Dan Schulz, Yuyi Feng, and Nelson Salgado of Ionis Pharmaceuticals for database support; Tracy Reigle of Ionis Pharmaceuticals for graphics support; and GCP ClinPlus Co., Ltd. (Bejing, China) for SAS programming and statistical analysis.

Author Disclosure Statement

All authors are employees of Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc.

References

- 1.Crooke ST, ed. (2008). Antisense Drug Technology Principles, Strategies, and Applications, 2nd ed. CRC Press, New York [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bennett CF. (2008). Pharmacological properties of 2′-O-methoxyethyl-modified oligonucleotides. In: Antisense Drug Technology, Principles, Strategies and Applications, 2nd ed. Crooke ST, ed. CRC Press, New York, pp 273–303 [Google Scholar]

- 3.Levin AA, Yu RZ. and Geary RS. (2008). Basic principles of the pharmacokinetics of antisense oligonucleotide drugs. In: Antisense Drug Technology, Principles, Strategies and Applications, 2nd ed. Crooke ST, ed. CRC Press, New York, pp 183–215 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Geary RS, Yu RS, Siwkowski A. and Levin AA. (2008). Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic properties of phosphorothioate 2′-O-(2-methoxyethyl)-modified antisense oligonucleotides in animals and man. In: Antisense Drug Technology, Principles, Strategies and Applications, 2nd ed. Crooke ST, ed. CRC Press, New York, pp 305–326 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Henry SP, Kim TW, Kramer-Strickland K, Zanardi TA, Fey RA. and Levin AA. (2008). Toxicological properties of 2′-O-methoxyethyl chimeric antisense inhibitors in animals and man. In: Antisense Drug Technology, Principles, Strategies and Applications, 2nd ed. Crooke ST, ed. CRC Press, New York, pp 327–363 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bennett CF, Baker BF, Pham N, Swayze E. and Geary RS. (2017). Pharmacology of antisense drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 57:81–105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Crooke ST, Baker BF, Kwoh TJ, Cheng W, Schulz DJ, Xia S, Salgado N, Bui H-H, Hart CE, et al. (2016). Integrated safety assessment of 2'-O-methoxyethyl chimeric antisense oligonucleotides in nonhuman primates and healthy human volunteers. Mol Ther 24:1771–1782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Crooke ST, Baker BF, Witztum JL, Kwoh TJ, Pham NC, Salgado N, McEvoy BW, Cheng W, Hughes SG, Bhanot S. and Geary RS. (2017). The effects of 2'-O-methoxyethyl containing antisense oligonucleotides on platelets in human clinical trials. Nucleic Acid Ther 27:121–129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zanardi TA, Han SC, Jeong EJ, Rime S, Yu RZ, Chakravarty K. and Henry SP. (2012). Pharmacodynamics and subchronic toxicity in mice and monkeys of ISIS 388626, a second-generation antisense oligonucleotide that targets human sodium glucose cotransporter 2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 343:489–496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Meer L, Moerland M, van Dongen M, Goulouze B, de Kam M, Klaassen E, Cohen A. and Burggraaf J. (2016). Renal effects of antisense-mediated inhibition of SGLT2. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 359:280–289 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van Meer L, van Dongen M, Moerland M, de Kam M, Cohen A. and Burggraaf. J. (2017). Novel SGLT2 inhibitor: first-in-man studies of antisense compound is associated with unexpected renal effects. Pharmacol Res Perspect 5:e00292. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. press release on phase 3 inotersen topline results. http://ir.ionispharma.com/phoenix.zhtml?c=222170&p=irol-newsArticle&ID=2272828 Accessed on August18, 2017

- 13.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute. (2010). Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) Version 4.03 (June 2010). https://evs.nci.nih.gov/ftp1/CTCAE/CTCAE_4.03_2010-06-14_QuickReference_8.5×11.pdf Accessed on August18, 2017

- 14.Levey AS, Bosch JP, Lewis JB, Greene T, Rogers N. and Roth D. (1999). A more accurate method to estimate glomerular filtration rate from serum creatinine: a new prediction equation. Modification of diet in renal disease study group. Ann Intern Med 130:461–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Naughton CA. (2008). Drug-induced nephrotoxicity. Am Fam Physician 78:743–750 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perazella MA. and Luciano RL. (2015). Review of select causes of drug-induced AKI. Expert Rev Clin Pharmacol 8:367–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fried LF, Emanuele N, Zhang JH, Brophy M, Conner TA, Duckworth W, Leehey DJ, McCullough PA, O'Connor T, et al. (2013). Combined angiotensin inhibition for the treatment of diabetic nephropathy. N Engl J Med 369:1892–1903 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beldhuis IE, Streng KW, Ter Maaten JM, Voors AA, van der Meer P, Rossignol P, McMurray JJ. and Damman K. (2017). Renin-angiotensin system inhibition, worsening renal function, and outcome in heart failure patients with reduced and preserved ejection fraction: a meta-analysis of published study data. Circ Heart Fail 10:pii: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lobato L. and Rocha A. (2012). Transthyretin amyloidosis in the kidney. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7:1337–1346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Feldman HI, Greene T, Lash JP, Nelson RG, Rahman M, Deysher AE, Zhang YL, Schmid CH. and Levey AS. (2007). Evaluation of the modification of diet in renal disease study equation in a large diverse population. J Am Soc Nephrol 18:2749–2757 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tsimikas S, Viney NJ, Hughes SG, Singleton W, Graham MJ, Baker BF, Burkey JL, Yang Q, Marcovina SM, et al. (2015). Antisense therapy targeting apolipoprotein(a): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase 1 study. Lancet 386:1472–1483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Viney NJ, van Capelleveen JC, Geary RS, Xia S, Tami JA, Yu RZ, Marcovina SM, Hughes SG, Graham MJ, et al. (2016). Antisense oligonucleotides targeting apolipoprotein(a) in people with raised lipoprotein(a): two randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, dose-ranging trials. Lancet 388:2239–2253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Yu RZ, Gunawan R, Post N, Zanardi T, Hall S, Burkey J, Kim TW, Graham MJ, Prakash TP, et al. (2016). Disposition and pharmacokinetics of a GalNAc3-conjugated antisense oligonucleotide targeting human lipoprotein (a) in monkeys. Nucleic Acid Ther 26:372–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yu RZ, Graham MJ, Post N, Riney S, Zanardi T, Hall S, Burkey J, Shemesh CS, Prakash TP, et al. (2016). Disposition and pharmacology of a GalNAc3-conjugated ASO targeting human lipoprotein (a) in mice. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids 5:e317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Graham MJ, Lee RG, Brandt TA, Tai LJ, Fu W, Peralta R, Yu R, Hurh E, Paz E, et al. (2017). Cardiovascular and metabolic effects of ANGPTL3 antisense oligonucleotides. N Engl J Med 377:222–232 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.