Abstract

BACKGROUND:

A teenage woman’s sexual health practices may be influenced by her mother’s experience. We evaluated whether there is an intergenerational tendency for induced abortion between mothers and their teenage daughters.

METHODS:

We conducted a retrospective population-based cohort study involving daughters born in Ontario between 1992 and 1999. We evaluated the daughters’ data for induced abortions between age 12 years and their 20th birthday. We assessed each mother’s history of induced abortion for the period from 4 years before her daughter’s birth to 12 years after (i.e., when her daughter turned 12 years of age). We used Cox proportional hazard models to estimate a daughter’s risk of having an induced abortion in relation to the mother’s history of the same procedure. We adjusted hazard ratios (HRs) for maternal age and world region of origin, mental or physical health problems in the daughter, mother– daughter cohabitation, neighbourhood-level rate of teen induced abortion, rural or urban residence, and income quintile.

RESULTS:

A total of 431 623 daughters were included in the analysis. The cumulative probability of teen induced abortion was 10.1% (95% confidence interval [CI] 9.8%–10.4%) among daughters whose mother had an induced abortion, and 4.2% (95% CI 4.1%–4.3%) among daughters whose mother had no induced abortion, for an adjusted HR of 1.94 (95% CI 1.86–2.01). The adjusted HR of a teenaged daughter having an induced abortion in relation to number of maternal induced abortions was 1.77 (95% CI 1.69–1.85) with 1 maternal abortion, 2.04 (95% CI 1.91–2.18) with 2 maternal abortions, 2.39 (95% CI 2.19–2.62) with 3 maternal abortions and 2.54 (95% CI 2.33–2.77) with 4 or more maternal abortions, relative to none.

INTERPRETATION:

We found that the risk of teen induced abortion was higher among daughters whose mother had had an induced abortion. Future research should explore the mechanisms for intergenerational induced abortion.

Each year, about 6.7 million induced abortions are performed in developed nations.1 A considerable proportion of these procedures are among teens aged 19 years or younger, at rates of 12–25 per 1000 women, depending on the country.2–7 In Canada, the teen pregnancy rate is 28 per 1000, with more than half of these pregnancies ending in induced abortion.6,7 Short-term morbidity related to the procedure is uncommon, but includes incomplete procedure, infection, hemorrhage and hematometra, as well as uterine perforation.8 Compared with women with abortion at an older age, those who undergo induced abortion as teenagers are more likely to report psychologic stress related to the procedure.9,10

Teen induced abortion may be influenced by factors at the individual, family, peer and community levels.11,12 A positive association has been observed between mother and daughter in the timing of fertility practices,13 age of first childbirth14 and teen child-bearing.12,15 We examined whether there is an intergenerational association between mothers and their teenage daughters with respect to induced abortion.

Methods

Study setting

We conducted a population-based retrospective cohort study using administrative health care data for the province of Ontario, Canada, where health care, including induced abortion procedures, is publicly funded. Abortion services, legalized in Canada in January 1988,16,17 can be accessed through outpatient clinics and hospitals up to 24 weeks gestational age.16 Almost all induced abortions in Canada are performed as surgical procedures, with less than 5% being pharmaceutically induced18 with methotrexate and misoprostol or with misoprostol alone.19 During the period of the current study, mifepristone was unavailable in Canada.

Although access to abortion services can vary geographically,20–22 there is no legal restriction based on a woman’s age.3 Parental consent is not required for adolescents aged 16 years or older or for counselled mature minors under 16 years of age.23

Data sources

All study databases are housed at the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES) in Toronto. We identified induced abortion procedures by combining information from the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI) Discharge Abstract Database, the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System and the Ontario Health Insurance Plan (OHIP) database, which contains billing information for all physicians (Appendix 1, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170595/-/DC1). We obtained demographic information through the Registered Persons Database; determined each mother’s immigrant status through the Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada Permanent Resident database; and identified mother–daughter pairs in the MOMBABY data set. These data sets were linked with unique encoded identifiers and analyzed at ICES.

Participants

We first identified all daughters born alive in Ontario between Jan. 1, 1992, and Dec. 31, 1999. We excluded daughters whose mothers were younger than 12 years of age or older than 50 years of age at the daughter’s birth, those whose mother’s country of birth was unknown, daughters with less than 12 years of follow-up since the date of birth, those missing information on income quintile and those residing in a neighbourhood with a sparse number of teens, as described below.

Exposures and outcomes

The primary exposure was whether a mother had at least 1 induced abortion in the period from 4 years before her daughter’s birth up to 12 years after (i.e., when her daughter turned 12 years of age). We assigned each daughter to the exposed or the unexposed group, according to whether her mother had an induced abortion during this defined period. We had 2 reasons for defining the exposure period as 4 years before to 12 years after the daughter’s birth. First, given that the mean age at menarche is 12.7 years,24 starting at 12 years after the daughter’s birth would approximate the earliest age that a daughter might undergo induced abortion. Second, data on induced abortion were available in our data sets only from 1988 onward, the year when the procedure was legalized. Thus, for daughters in our cohort born in 1992, only a 4-year look-back window (to 1988) was possible. Nevertheless, as described below, we performed additional analyses considering a maternal history of induced abortion in the period between 10 years before and 16 years after the daughter’s birth, and in the period when the mother was aged 15 years up to 38–43 years.

The secondary exposure was the cumulative number of induced abortions that the mother had in the period between 4 years before and 12 years after the daughter’s birth, categorized as 0, 1, 2, 3 or ≥ 4.

The primary study outcome was time to a daughter’s first teen induced abortion, between age 12 years and her 20th birthday. For the primary outcome, we followed each daughter from age 12 years to the date of the first induced abortion; otherwise, the daughter’s data were censored if she died, was lost to follow-up, reached her 20th birthday, or was alive and event-free at the end of the study (Mar. 31, 2016). The secondary study outcome was the cumulative number of induced abortions that a daughter had as a teenager, censoring on the same factors as above.

We defined induced abortion as intentional termination of pregnancy through a surgical procedure or use of an abortifacient pharmaceutical agent before 20 weeks gestational age (Appendix 1). If a woman had more than 1 induced abortion during the study period, it was required that the subsequent abortion occurred at least 90 days after the preceding one. The timing was determined either by the gestational age (in weeks) in the CIHI Discharge Abstract Database or the National Ambulatory Care Reporting System database or by an OHIP physician billing code for induced abortion at gestational age less than 15 weeks (“early”) or gestational age 15 weeks or older (“late”).

Covariables

Confounding factors were based on previous studies.25–27 The first set of factors, assessed at the daughter’s birth, were the mother’s age, the mother’s world region of origin,28 whether the daughter was born preterm (at 24–36 wk gestational age rather than at term), residential income quintile, and rural or urban residence. The second set of factors, when the daughter was 12 years of age, included residential income quintile, rural or urban residence, mother–daughter cohabitation (i.e., both residing within the same dissemination area [defined as a small, relatively stable geographic unit comprising 400–700 residents]) and rate of teen induced abortion within the daughter’s residential dissemination area. The second set of confounders also included any major physical illness or mental illness in the 2-year period before the daughter turned 12 years of age, evaluated by the Johns Hopkins Aggregated Diagnostic Group using diagnostic information from inpatient care, emergency department visits and physician visits.29,30 We calculated the rate of teen induced abortion in each residential dissemination area as the number of abortions experienced by girls aged 12–19 years residing in the same dissemination area in the same calendar year as when the daughter turned age 12 years, divided by the total number of girls aged 12–19 years residing within that dissemination area during that calendar year. It is for this reason that we excluded any daughter residing in a dissemination area with fewer than 6 teenage girls at the time the daughter was 12 years of age.

Statistical analysis

We reported mothers’ and daughters’ characteristics for the exposed and unexposed groups. We used standardized differences to compare means and proportions, with absolute values greater than 0.10 being deemed to indicate important differences for a given variable.31,32

We calculated incidence rates of induced abortion, and used Cox proportional hazard models to generate hazard ratios (HRs) for a daughter having an induced abortion in relation to her mother having had the same procedure. We used robust sandwich variance estimates to account for clustering (i.e., daughters with the same mother).33 The HRs were adjusted for the covariables listed above.

The main model was then stratified by maternal age, world region of origin, residential income quintile, rate of teen induced abortion within the residential dissemination area and mother–daughter cohabitation. To account for possible right-censoring on the risk estimates from the main model, we restricted the sample to daughters born in 1995, thereby ensuring complete follow-up of each daughter to the day of her 20th birthday.

Information on each mother’s history of induced abortion across all reproductive years was unavailable, so we performed 3 additional analyses. First, we expanded the assessment of maternal history of induced abortion to the period from 4 years before to 16 years after her daughter’s birth. Then, in a restricted sample of daughters born in 1998 and 1999, we further widened the assessment of maternal induced abortion to the period from 10 years before to 16 years after her daughter’s birth. Finally, in a subcohort of daughters whose mothers were born between 1973 and 1977, we estimated each daughter’s risk of having an induced abortion in relation to her mother having had an induced abortion from 15 years of age up to 38–43 years.

We also evaluated whether the daughter’s first induced abortion was early (< 15 wk gestational age) or late (≥ 15 wk gestational age). We used a Fine and Gray subdistribution hazard model34 to estimate the HR in this analysis.

To assess for a dose–response effect, we first evaluated within the original Cox model the total number of induced abortions that the mother had had (0, 1, 2, 3 or ≥ 4) between 4 years before and 12 years after the daughter’s birth date, and the corresponding HR for a daughter having any teen induced abortion. Then, we used multinomial logistic regression to assess the number of teen induced abortions that a daughter experienced (0, 1, 2 or ≥ 3) in relation to the number of maternal abortions (0, 1, 2 or ≥ 3).

All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute).

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Board of Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre and the Office of Research Ethics at the University of Toronto.

Results

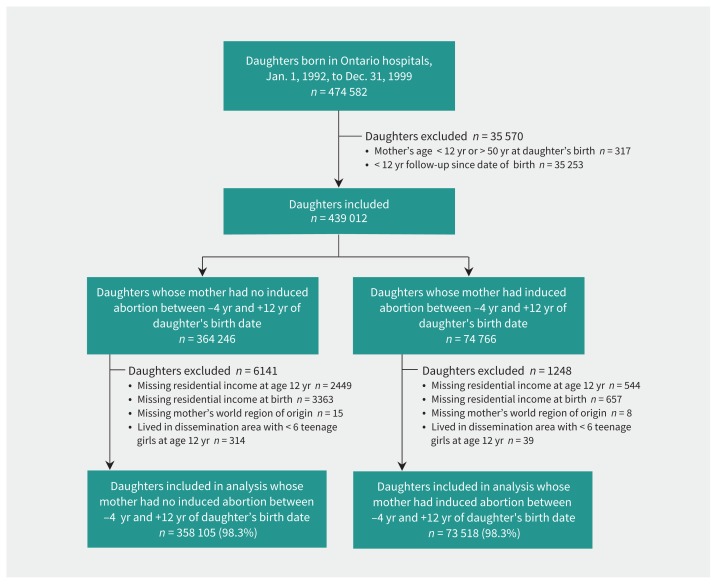

Of 474 582 daughters born in an Ontario hospital between Jan. 1, 1992, and Dec. 31, 1999, 431 623 were included in the analysis: 73 518 in the exposed group and 358 105 in the unexposed group (Figure 1).

Figure 1:

Flow chart of study groups.

Mothers who had an induced abortion during the specified period were younger at their daughters’ birth than mothers who did not have an abortion (26.2 v. 29.5 yr) (Table 1). A higher proportion of daughters in the exposed than the unexposed group were born to mothers from South Asia, East Asia, the Caribbean and Hispanic America, and were more likely to reside in a low-income area. Unexposed daughters were more likely to reside in a dissemination area with no teen induced abortions. Starting from birth, the mean follow-up time was 18.5 years in the exposed group and 18.7 years in the unexposed group (Table 1).

Table 1:

Characteristics of mothers and their daughters born between 1992 and 1999, according to whether the mother had an induced abortion between 4 years before and 12 years after the daughter’s birth date

| Characteristic | Maternal induced abortion; no. (%) of daughters* | Standardized difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes n = 73 518 |

No n = 358 105 |

||

| Mother’s age at daughter’s birth, yr | |||

| Mean ± SD | 26.2 ± 5.7 | 29.5 ± 5.1 | −0.61 |

| < 20 | 10 012 (13.6) | 11 214 (3.1) | 0.39 |

| 20–24 | 19 721 (26.8) | 47 094 (13.2) | 0.35 |

| 25–29 | 22 187 (30.2) | 117 144 (32.7) | −0.05 |

| 30–34 | 15 834 (21.5) | 125 415 (35.0) | −0.3 |

| 35–39 | 5197 (7.1) | 49 789 (13.9) | −0.22 |

| ≥ 40 | 567 (0.8) | 7449 (2.1) | −0.11 |

| Mother’s world region of origin | |||

| Africa | 1533 (2.1) | 4014 (1.1) | 0.08 |

| Canada | 54 930 (74.7) | 314 130 (87.7) | −0.34 |

| Caribbean | 2588 (3.5) | 3217 (0.9) | 0.18 |

| East Asia | 4029 (5.5) | 10 256 (2.9) | 0.13 |

| Hispanic America | 1879 (2.6) | 4170 (1.2) | 0.1 |

| Middle East | 885 (1.2) | 3734 (1.0) | 0.02 |

| South Asia | 5761 (7.8) | 8327 (2.3) | 0.25 |

| Western nation other than Canada | 1913 (2.6) | 10 257 (2.9) | −0.02 |

| Daughter’s year of birth | |||

| 1992 | 5081 (6.9) | 33 495 (9.4) | −0.09 |

| 1993 | 8547 (11.6) | 47 788 (13.3) | −0.05 |

| 1994 | 9976 (13.6) | 49 222 (13.7) | −0.01 |

| 1995 | 10 420 (14.2) | 47 728 (13.3) | 0.02 |

| 1996 | 9858 (13.4) | 46 047 (12.8) | 0.02 |

| 1997 | 9877 (13.4) | 45 205 (12.6) | 0.02 |

| 1998 | 10 074 (13.7) | 44 907 (12.5) | 0.03 |

| 1999 | 9685 (13.2) | 43 713 (12.2) | 0.03 |

| Daughter born preterm (< 37 wk gestational age) | 4988 (6.8) | 22 188 (6.2) | 0.02 |

| Residential income quintile of daughter at birth | |||

| Q1 (lowest) | 25 327 (34.4) | 74 488 (20.8) | 0.31 |

| Q2 | 17 240 (23.4) | 72 364 (20.2) | 0.08 |

| Q3 | 13 017 (17.7) | 73 403 (20.5) | −0.07 |

| Q4 | 10 523 (14.3) | 75 372 (21.0) | −0.18 |

| Q5 (highest) | 7411 (10.1) | 62 478 (17.4) | −0.22 |

| Rural residence of daughter at birth | 5207 (7.1) | 47 679 (13.3) | 0.21 |

| Daughter had mental illness in 2 yr before turning age 12 yr† | 8446 (11.5) | 38 398 (10.7) | 0.02 |

| Daughter had major physical illness in 2 yr before turning age 12 yr† | 12 506 (17.0) | 64 178 (17.9) | −0.02 |

| Mother–daughter cohabitation when daughter turned age 12 yr | 46 394 (63.1) | 232 463 (64.9) | 0.04 |

| Residential income quintile of daughter at age 12 yr | |||

| Q1 (lowest) | 18 454 (25.1) | 54 197 (15.1) | 0.25 |

| Q2 | 16 743 (22.8) | 63 341 (17.7) | 0.13 |

| Q3 | 15 104 (20.5) | 72 651 (20.3) | 0.01 |

| Q4 | 13 007 (17.7) | 81 371 (22.7) | 0.13 |

| Q5 (highest) | 10 210 (13.9) | 86 545 (24.2) | −0.26 |

| Rural residence of daughter at age 12 yr | 5510 (7.5) | 45 442 (12.7) | 0.17 |

| Induced abortion rate in dissemination area where the daughter was residing at age 12 yr, per 1000 | |||

| 0 | 42 385 (57.7) | 239 340 (66.8) | −0.19 |

| 0.1–9.9 | 5651 (7.7) | 18 508 (5.2) | 0.10 |

| 10.0–19.9 | 9209 (12.5) | 32 396 (9.0) | 0.11 |

| 20.0–29.9 | 6659 (9.1) | 27 823 (7.8) | 0.05 |

| 30.0–39.9 | 4095 (5.6) | 17 637 (4.9) | 0.03 |

| ≥ 40 | 5519 (7.5) | 22 401 (6.3) | 0.05 |

| Study follow-up for daughter, from birth to primary end point, yr, mean ± SD‡ | 18.5 ± 1.6 | 18.7 ± 1.5 | 0.11 |

Note: SD = standard deviation.

Except where indicated otherwise.

Based on Johns Hopkins Adjusted Aggregated Diagnosis Groups.

End of follow-up was defined as the earliest of the following: date of first induced abortion, date of death, date lost to follow-up from administrative data sets, 20th birthday or Mar. 31, 2016.

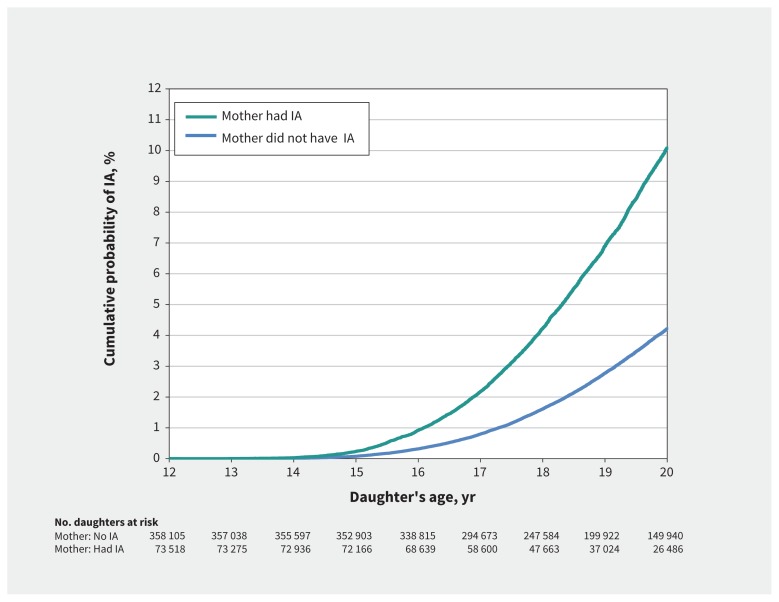

Of the 73 518 daughters in the exposed group, 4880 had a teen induced abortion, for an incidence rate of 10.1 per 1000 person-years. In the unexposed group of 358 105 daughters, 10 108 had a teen induced abortion, for an incidence rate of 4.2 per 1000 person-years (Table 2). The corresponding adjusted HR in the main model was 1.94 (95% confidence interval [CI] 1.86–2.01) (Table 2). The rate of teen induced abortion started to rise notably at about age 15 years, with the cumulative probability of having an induced abortion reaching 10.1% (95% CI 9.8%–10.4%) in the exposed group and 4.2% (95% CI 4.1%–4.3%) in the unexposed group by the 20th birthday (Figure 2). The adjusted HR for teen induced abortion persisted across variables at the daughter’s birth and at age 12 years (Appendix 2, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170595/-/DC1).

Table 2:

Main model of risk that a daughter had a first induced abortion (IA) as a teenager, in relation to her mother having had IA between 4 years before and 12 years after daughter’s birth date

| Maternal IA between −4 and +12 yr of daughter’s birth date | No. (%) of daughters with IA | Incidence rate at time of first IA, per 1000 person-years (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude* | Adjusted*† | |||

| No (n = 358 105) | 10 108 (2.8) | 4.2 (4.1–4.3) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| Yes (n = 73 518) | 4880 (6.6) | 10.1 (9.9–10.4) | 2.51 (2.43–2.60) | 1.94 (1.86–2.01) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, HR = hazard ratio.

Results based on Cox proportional hazard models. Robust sandwich variance estimates were used to account for more than 1 daughter clustered within the same mother.

Adjusted for mother’s age when giving birth to her daughter, mother’s world region of origin, daughter’s mental health status in the 2-year period before turning age 12 years, whether daughter had major physical health problem in the 2-year period before turning age 12 years, neighbourhood-level teen IA rate, mother–daughter cohabitation when daughter was 12 years of age, daughter’s residence (rural v. urban) at time of birth and at age 12 years, and daughter’s neighbourhood income quintile at time of birth and at age 12 years.

Figure 2:

Cumulative probability of having an induced abortion (IA) among teenage daughters whose mothers had or did not have an IA between 4 years before and 12 years after the daughter’s birth.

Limiting the main model to daughters born in 1995, all of whom had 20 years of follow-up, did not change the main findings (Appendix 3, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170595/-/DC1). Similar results were obtained when we expanded the exposure period of maternal induced abortion, as either from 4 years before to 16 years after the daughter’s birth (Appendix 4, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170595/-/DC1) or from 10 years before to 16 years after the daughter’s birth (Appendix 5, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170595/-/DC1), or when we considered maternal induced abortion from 15 up to 38–43 years of age (Appendix 6, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170595/-/DC1).

Of all daughters who had a teen induced abortion, 14 158 (94.5%) had the procedure early, at less than 15 weeks gestational age, and 645 (4.3%) had it late, at gestational age 15 weeks or older; for 185 (1.2%), gestational age was unknown. There was an association between a mother’s and her daughter’s induced abortion for both early (adjusted HR 1.95, 95% CI 1.87–2.02) and late (adjusted HR 1.79, 95% CI 1.47–2.16) induced abortions among the daughters (Appendix 7, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170595/-/DC1).

A dose–response effect was seen for teen induced abortion, with adjusted HRs of 1.77 (95% CI 1.69–1.85) among daughters whose mothers had 1 induced abortion in the exposure period, 2.04 (95% CI 1.91–2.18) with 2 maternal abortions, 2.39 (95% CI 2.19–2.62) with 3 maternal abortions and 2.54 (95% CI 2.33–2.77) with 4 or more maternal abortions, relative to none (Table 3). Furthermore, a daughter whose mother had 3 or more induced abortions was most likely to also have 3 or more induced abortions (adjusted odds ratio [OR] 3.18, 95% CI 2.37–4.28), relative to a daughter whose mother had no induced abortions (Appendix 8, available at www.cmaj.ca/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1503/cmaj.170595/-/DC1).

Table 3:

Risk of a daughter having a first induced abortion (IA) as a teenager, in relation to total number of IAs that her mother had between 4 years before and 12 years after daughter’s birth date

| No. of maternal IAs between −4 yr and +12 yr of daughter’s birth date | No. (%) of daughters with IA | Incidence rate at time of first IA, per 1000 person-years (95% CI) | HR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Crude* | Adjusted*† | |||

| 0 (n = 358 105) | 10 108 (2.8) | 4.2 (4.1–4.3) | 1.00 (ref) | 1.00 (ref) |

| 1 (n = 46 441) | 2622 (5.6) | 8.6 (8.2–8.9) | 2.10 (2.01–2.19) | 1.77 (1.69–1.85) |

| 2 (n = 14 812) | 1063 (7.2) | 11.0 (10.4–11.7) | 2.76 (2.59–2.94) | 2.04 (1.91–2.18) |

| 3 (n = 6134) | 559 (9.1) | 14.1 (13.0–15.3) | 3.58 (3.28–3.91) | 2.39 (2.19–2.62) |

| ≥ 4 (n = 6131) | 636 (10.4) | 16.4 (15.1–17.7) | 4.28 (3.94–4.64) | 2.54 (2.33–2.77) |

Note: CI = confidence interval, HR = hazard ratio.

Results based on Cox proportional hazard models. Robust sandwich variance estimates were used to account for more than 1 daughter clustered within the same mother.

Adjusted for mother’s age when giving birth to her daughter, mother’s world region of origin, daughter’s mental health status in the 2-year period before turning age 12 years, whether daughter had major physical health problem in the 2-year period before turning age 12 years, neighbourhood-level teen IA rate, mother–daughter cohabitation when daughter was 12 years of age, daughter’s residence (rural v. urban) at time of birth and at age 12 years, and daughter’s neighbourhood income quintile at time of birth and at age 12 years.

Interpretation

In Ontario, the risk of having an induced abortion as a teenager was twice as high among daughters whose mother had an induced abortion. This higher risk of intergenerational induced abortion persisted across various demographic groups and was more pronounced with increasing numbers of maternal abortions.

The mechanisms for intergenerational induced abortion are unclear, and this study was not designed to assess such details. Several previous studies explored the determinants of teen abortion, and reported that a woman is more likely to have a teen induced abortion if she has mental illness or a substance use disorder, 25–27 poor school performance,25 teenage parents at her own birth, parents with a lower level of education25–27 or receiving income support,26 and family disruption resulting in separation from biological parents.26,27 These factors should be taken into consideration when studying intergenerational induced abortion. In a previous study from Finland, the adjusted OR for a daughter having a teen induced abortion was 1.8 (95% CI 1.5–2.2) among those whose mother did versus did not have an antecedent induced abortion.26 However, no details were available to further characterize the association.

Limitations

This study lacked details on several factors, including information about the daughter’s father, the marital status and educational attainment of both the daughter and her mother, and family dynamics. Cohabitation of the mother and daughter was defined using a proxy, namely, that the mother and daughter were residing in the same dissemination area; however, it is possible that a mother and daughter lived nearby, but in different households. Although physician services for induced abortion are fully covered under Ontario’s universal health insurance system, some women may have undergone induced abortion by a nonphysician or outside of the province.

In the main analysis, a mother’s history of induced abortion was assessed only between 4 years before and 12 years after the daughter’s birth, rather than throughout the mother’s reproductive years. However, in additional analyses that expanded the timing of maternal abortion exposure, the associated risk persisted. We had no information about the indication for teen induced abortion. However, most occurred at less than 15 weeks gestational age, which suggests that most were for social indications, rather than for a recognized fetal trisomy or congenital anomaly (typically detected by prenatal screening after 16 weeks gestational age). We did not have information about the sex of the embryo or fetus carried by the daughter or mother, or about other liveborn children. We previously found that induced abortions were more likely among female fetuses of Indian-born mothers who already had daughters.35,36 However, in the current study, we found no variation in intergenerational induced abortion across immigrant groups.

Conclusion

This study identified maternal induced abortion as a risk factor for teen induced abortion. Further assessment is required to determine the effectiveness of family-centred interventions (aimed at engaging parents) in reducing sexual behaviour and unprotected sex among teenagers. Future research should consider more in-depth exploration of the factors that contribute not only to teen pregnancy, but also to a decision to proceed with induced abortion among teenage women.

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Dr. Michael Geary, St. Michael’s Hospital, Toronto, for his valuable suggestions on study design.

Footnotes

Competing interests: None declared.

This article has been peer reviewed.

Contributors: Ning Liu had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. Ning Liu and Joel Ray contributed to the study concept, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation of the data, and drafting and revision of the manuscript. Michèle Farrugia, Simone Vigod and Marcelo Urquia contributed to the analysis and interpretation of data and to critical revision of the manuscript. All of the authors gave final approval of the version to be published and agreed to be accountable for all apsects of the work.

Funding: Joel Ray is supported by an Applied Research Chair in Reproductive and Child Health Services and Policy Research from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research. This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC).

Disclaimer: This study was supported by the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences (ICES), which is funded by an annual grant from the Ontario Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care (MOHLTC). The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis or interpretation of the data; preparation, review or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication. No endorsement by ICES or the Ontario MOHLTC is intended or should be inferred. Parts of this material are based on data and information compiled and provided by the Canadian Institute for Health Information (CIHI). However, the analyses, conclusions, opinions and statements expressed herein are those of the authors, and not necessarily those of CIHI.

References

- 1.Sedgh G, Bearak J, Singh S, et al. Abortion incidence between 1990 and 2014: global, regional, and subregional levels and trends. Lancet 2016;388:258–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sedgh G, Finer LB, Bankole A, et al. Adolescent pregnancy, birth, and abortion rates across countries: levels and recent trends. J Adolesc Health 2015;56:223–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fleming N, O’Driscoll T, Becker G, et al. ; CANPAGO Committee. Adolescent pregnancy guidelines. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2015;37:740–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Finer LB, Zolna MR. Declines in unintended pregnancy in the United States, 2008–2011. N Engl J Med 2016;374:843–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones RK, Kavanaugh ML. Changes in abortion rates between 2000 and 2008 and lifetime incidence of abortion. Obstet Gynecol 2011;117:1358–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKay A, Barrett B. Trends in teen pregnancy rates from 1996–2006: a comparison of Canada, Sweden, U.S.A., and England/Wales. Can J Hum Sex 2010; 19:43–52. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dunn S, Wise MR, Johnson LM, et al. Chapter 10: Reproductive and gynaecological health Bierman AS, editor. Ontario women’s health equity report. Vol. 2 Toronto: Project for an Ontario Women’s Health Evidence-Based Report; 2011:74–92. Available: http://powerstudy.ca/wp-content/uploads/downloads/2012/10/Chapter10-ReproductiveandGynaecologicalHealth.pdf (accessed 2017 Mar. 12). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Upadhyay UD, Desai S, Zlidar V, et al. Incidence of emergency department visits and complications after abortion. Obstet Gynecol 2015;125:175–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Franz W, Reardon D. Differential impact of abortion on adolescents and adults. Adolescence 1992;27:161–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Major B, Cozzarelli C, Cooper ML, et al. Psychological responses of women after first-trimester abortion. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2000;57:777–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Institute of Medicine. The future of the public’s health in the 21st century. Washington: The National Academies Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meade CS, Kershaw TS, Ickovics JR. The intergenerational cycle of teenage motherhood: an ecological approach. Health Psychol 2008;27:419–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jennings JA, Sullivan AR, Hacker JD. Intergenerational transmission of reproductive behavior during the demographic transition. J Interdiscip Hist 2012; 42:543–69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Barber JS. The intergenerational transmission of age at first birth among married and unmarried men and women. Soc Sci Res 2001;30:219–47. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hardy JB, Astone NM, Brooks-Gunn J, et al. Like mother, like child: intergenerational patterns of age at first birth and associations with childhood and adolescent characteristics and adult outcomes in the second generation. Dev Psychol 1998;34:1220–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sabourin JN, Burnett M. A review of therapeutic abortions and related areas of concern in Canada. J Obstet Gynaecol Can 2012;34:532–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.CMA policy summary. Induced abortion. CMAJ 1988;139:1176A–B. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Induced abortions reported in Canada in 2014. Ottawa: Canadian Institute for Health Information; 2015. Available: https://www.cihi.ca/sites/default/files/document/induced_abortion_can_2014_en_web.xlsx (accessed 2017 Mar. 12). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davis V. SOGC clinical practice guidelines. No. 184: induced abortion guidelines Ottawa: Society of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists of Canada; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Norman WV, Soon JA, Maughn N, et al. Barriers to rural induced abortion services in Canada: findings of the British Columbia Abortion Providers Survey (BCAPS). PLoS One 2013;8:e67023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cano JK, Foster AM. “They made me go through like weeks of appointments and everything”: documenting women’s experiences seeking abortion care in Yukon territory, Canada. Contraception 2016;94:489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Norman WV, Guilbert ER, Okpaleke C, et al. Abortion health services in Canada: results of a 2012 national survey. Can Fam Physician 2016;62:e209–17. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.The injustice and harms of parental consent laws for abortion. Position Paper no. 58 Vancouver: Abortion Rights Coalition of Canada; 2014. Available: www.arcc-cdac.ca/postionpapers/58-Parental-Consent.pdf (accessed 2017 Mar. 15). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Sahab B, Ardern CI, Hamadeh MJ, et al. Age at menarche in Canada: results from the National Longitudinal Survey of Children & Youth. BMC Public Health 2010;10:736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lehti V, Sourander A, Polo-Kantola P, et al. Association between childhood psychosocial factors and induced abortion. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol 2013;166:190–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Leppälahti S, Heikinheimo O, Paananen R, et al. Determinants of underage induced abortion — the 1987 Finnish Birth Cohort study. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 2016;95:572–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christoffersen M. Motherhood and induced abortion among teenagers: a longitudinal study of all 15–19 year old Danish women born in 1966. Children, Youth and Families Working Paper 2 Copenhagen (Denmark): Danish National Institute of Social Research; 2003. Available: www.sfi-campbell.dk/Files/Filer/SFI/Pdf/Working_papers/wp2000303mc.pdf (accessed 2017 Feb. 11). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ray JG, Redelmeier DA, Urquia ML, et al. Risk of cerebral palsy among the offspring of immigrants. PLoS One 2014;9:e102275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.The Johns Hopkins ACG® System: excerpt from version 11.0 technical reference guide. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health; 2014. Available: http://www2.gov.bc.ca/assets/gov/health/conducting-health-research/data-access/johns-hopkins-acg-system-technical-reference-guide.pdf (accessed 2017 May 18). [Google Scholar]

- 30.The Johns Hopkins ACG® Case-Mix System technical reference guide version 10.0. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University; 2011 Available: https://www.hopkinsacg.org/document/acg-system-version-10-0-technical-reference-guide/ (accessed 2017 Sept. 8). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2nd ed Hillsdale (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mamdani M, Sykora K, Li P, et al. Reader’s guide to critical appraisal of cohort studies: 2. Assessing potential for confounding. BMJ 2005;330:960–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lin DY, Wei LJ. The robust inference for the Cox proportional hazards model. J Am Stat Assoc 1989;84:1074–8. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fine JP, Gray RJ. A proportional hazards model for the subdistribution of a competing risk. J Am Stat Assoc 1999;94:496–509. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ray JG, Henry DA, Urquia ML. Sex ratios among Canadian liveborn infants of mothers from different countries. CMAJ 2012;184:E492–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Urquia ML, Moineddin R, Jha P, et al. Sex ratios at birth after induced abortion. CMAJ 2016;188:E181–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]