Abstract

Increased environmental pollution has necessitated the need for eco-friendly clean-up strategies. Filamentous fungal species from gold and gemstone mine site soils were isolated, identified and assessed for their tolerance to varied heavy metal concentrations of cadmium (Cd), copper (Cu), lead (Pb), arsenic (As) and iron (Fe). The identities of the fungal strains were determined based on the internal transcribed spacer 1 and 2 (ITS 1 and ITS 2) regions. Mycelia growth of the fungal strains were subjected to a range of (0–100 Cd), (0–1000 Cu), (0–400 Pb), (0–500 As) and (0–800 Fe) concentrations (mgkg−1) incorporated into malt extract agar (MEA) in triplicates. Fungal radial growths were recorded every three days over a 13-days’ incubation period. Fungal strains were identified as Fomitopsis meliae, Trichoderma ghanense and Rhizopus microsporus. All test fungal exhibited tolerance to Cu, Pb, and Fe at all test concentrations (400–1000 mgkg−1), not differing significantly (p > 0.05) from the controls and with tolerance index >1. T. ghanense and R. microsporus demonstrated exceptional capacity for Cd and As concentrations, while showing no significant (p > 0.05) difference compared to the controls and with a tolerance index >1 at 25 mgkg−1 Cd and 125 mgkg−1 As. Remarkably, these fungal strains showed tolerance to metal concentrations exceeding globally permissible limits for contaminated soils. It is envisaged that this metal tolerance trait exhibited by these fungal strains may indicate their potentials as effective agents for bioremediative clean-up of heavy metal polluted environments.

Keywords: Fungi metal tolerance, Mycoremediation, Heavy metal, Mine site, Eco-friendly clean-up strategy

Introduction

Increased heavy metal contamination of soil and water environments1 has necessitated the need for clean-up strategies. Recently, diverse eco-friendly remediation options have been explored for the restoration of contaminated environments. These remediation options, among others, include the use of plants (phytoremediation),2 bacteria (bacterial bioremediation)3 and fungi (mycoremediation).4 The employability of these bio-resources (plants, bacteria and fungi) for effective bioremediation has been well reported.2, 3, 4

At present of these options, mycoremediation strategy has received increased attention in the bioremediation of contaminated/polluted environments due to its reasonably low cost implications and significant success outcomes.5, 6, 7, 8 Filamentous fungal species have been identified for their distinct attributes (ability to thrive under extreme pH, temperature and nutrient variability conditions, as well as tolerance to high metal concentrations)9, 10, 11 and hence their effective remediation traits of contaminated sites.

Metal tolerance/resistance has been defined as the ability of an organism to survive metal toxicity by means of one or more mechanisms devised in direct response to the metal(s) concerned.7, 12 Metal tolerance by filamentous fungi has been associated with their sites of isolation, toxicity of the metal tested, its concentration in medium, and on the isolate's competence.10 Contaminated sites are known as principal sources of metal-resistant species18, 19, 20, 21, 22 with indigenous fungal strains isolated from heavy metal contaminated sites exhibiting notable tolerance for high heavy metal concentrations.9, 21, 23, 24, 25

However, of more importance is the specific and nonspecific heavy metal tolerance mechanisms adopted by fungal species. According to Vadkertiova and Slavikova13 the introduction of heavy metals into the environment has induced physiological and morphological adaptation strategies in the microbial community. Specifically, fungal species adopt one or more metal tolerance strategies which include extracellular metal sequestration and precipitation, suppressed influx, enhanced metal efflux, production of intracellular/extracellular enzymes, metal binding to cell walls, intracellular sequestration and complexation.14, 15, 16, 17

Several metal-tolerant filamentous fungi (Rhizopus, Trichoderma, Aspergillus, Penicillium, and Fusarium) have been isolated from multiple heavy metal contaminated soils.7 Zafar et al.7 reported that Rhizopus sp., isolated from metal-contaminated agricultural soils tolerated Cd and Cr concentrations. In addition, Volesky26 observed that the mycelium of a Rhizopus specie was biosorbent towards Pb, Cd, Cu and Zn. Trichoderma species have also been known to exhibit tolerance to a range of toxicants27, 28, 29 and Cu, Cd, As and Zn heavy metals in in vitro conditions.8, 23, 27, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34

However, there is a dearth of knowledge of the growth response and heavy metal tolerance of filamentous fungal species isolated from gold and gemstone mining sites. This study was therefore designed to isolate, identify and assess the growth response and tolerance/resistance of filamentous fungi isolated from gold and gemstone mining sites to varied concentrations of selected heavy metals associated with mining sites.

Materials and methods

Study sites and soil sampling

Mine site soils used in this study were obtained from gemstone and gold mining sites in Southwestern, Nigeria namely: Awo (7°46′ N, 4°24′ E) and Itagunmodi (7°30′ N, 4°49′ E) as described.1, 4, 35 From previous studies,1, 4, 35 soil preliminary heavy metal analysis of the sites recorded elevated concentrations of 0.20–0.35 mgkg−1 Cd; 3.68–48.60 mgkg−1 Cu; 19.05–35.00 mgkg−1 Pb; 20.45–34.80 mgkg−1 As and 240.24–296.18 mgkg−1 Fe.

Isolation of soil fungi

Isolation of soil fungi was performed by serial dilution and the spread plate method using malt extract agar (MEA) medium and incubated at 30°C for five days as previously described.4, 35 Streptomycin (35 mgmL−1) was added as a supplement into the medium to inhibit bacterial growth. After incubation, isolates of single spores were successively sub-cultured on MEA to obtain pure isolates. Fungal species were characterized on the basis of phenotypical/macroscopic observation (pigmentation, shape, diameter, colony appearance and texture) and microscopic examination (septation of mycelium, shape, form, diameter and texture of spore/conidia). The cultural and morphological characteristic features of the fungal species were compared with those described.36 Fungal species were then selected for genotypic-based identification.

DNA extraction and PCR amplification

The ZR fungal/bacterial DNA kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) was used to extract genomic DNA from pure 5-day old fungal cultures according to the manufacturer's manual. About 40 mg (wet wt.) mycelium was harvested aseptically into the ZR BashingBead™ lysis tube and lysed in 750 μL of lysis buffer by bead beating. The lysate was then centrifuged at 13,400 rpm for 300 s to obtain clear supernatant. Further protocols, which are binding, wash steps and elution of DNA were performed as instructed by the manufacturer. The quality and integrity of the extracted DNA were verified on 1% agarose gel, while DNA concentration and purity were verified using NanoDrop spectrophotometer (ND-1000, NanoDrop Technologies Inc., Wilmington, Delaware USA).

Taxonomic identification of isolates was between the internally transcribed spacer regions – 1 (ITS1) and 2 (ITS2). DNA amplification was done using primer sets ITS1 (5′-TCCGTAGGTGAACCTGCGG-3′) and ITS4 (5′-TCCTCCGCTTATTGATATGC-3′).37 Each PCR reaction contained 12.5 μL of 2× Dream Master mix (Thermo Scientific Technologies, Waltham, MA, USA), 50 ng DNA template, 0.2 M of each forward and reverse primers and nuclease-free water to a final volume of 25 μL. PCR was performed in a C1000™ thermal cycler (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) involving an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 min, 29 cycles of denaturation at 95°C for 30 s, annealing at 55°C for 30 s and extension at 72°C for 60 s. The amplification process was terminated by a final extension of 72°C for 5 min. The PCR amplicons were then verified on 1.5% agarose gel after electrophoresis.

Sequencing and phylogenetic reconstruction

Purified PCR amplicons were sequenced by using forward primer ITS1 and the Big Dye terminator v3.1 cycle sequencing kit (Applied Biosystems, Warrington, UK) on a 3130 Genetic analyzer (Applied Biosystems/Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). Sequence electropherograms were inspected manually and edited with FinchTV (v. 1.4.0; http://www.geospiza.com/Products/finchtv.shtml). For taxonomic assignment, edited sequences were aligned with sequences on the UNITE ITS database (https://unite.ut.ee/index.php) while for, phylogenetic reconstruction, the sequences, together with closely related sequences in the GenBank were selected. Multiple sequence alignment of the obtained sequences was done using MUSCLE38 integrated in MEGA V. 6.0.39 The resulting multiple sequence alignments were then edited manually and rectified for gaps using DAMBE software.40 Phylogeny dendrograms were constructed using the neighbour-joining method of the Tamura–Nei substitution model and a thousand bootstrap replications in MEGA.

Heavy metal tolerance assay

Isolated filamentous fungi were assessed for heavy metal tolerance at varying Cd, Cu, Pb, As and Fe concentrations. Filter (0.25 μm pore size) sterilized heavy metal salts of CdCl2, CuSO4, PbSO4, AsSO4 and Fe2SO4 were incorporated into sterile MEA. Media were supplemented with 35 mgmL−1 streptomycin and pH was maintained at 5.6 by the addition of 3 M NaOH. The experiment was conducted in triplicates with control and four other varied test concentrations. Heavy metal concentrations (mgkg−1) were: (25, 50, 75 and 100) cadmium, (125, 250, 500 and 1000) copper, (100, 200, 300 and 400) lead, (125, 250, 375 and 500) arsenic and (200, 400, 600 and 800) iron. The non-amended medium served as a control.

Test fungal strain of 8 mm diameter disks from 7-day old pure culture each were individually inoculated into an 8 mm well aseptically bored at the centre of control and test MEA plates. All plates were incubated at 29 ± 1°C for 13 days, during which mycelial radial growth was monitored and recorded every three days. Heavy metal tolerance potential of the fungal species in the test medium was calculated in relation to the control radial growths (Eq. (1)). Fungi heavy metal tolerance was rated thus: 0.00–0.39 (very low tolerance), 0.40–0.59 (low tolerance), 0.60–0.79 (moderate tolerance), 0.80–0.99 (high tolerance) and 1.00–>1.00 (very high tolerance), the higher the values, the higher the fungal tolerance to the heavy metal.

| (1) |

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis of data obtained was done using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) at 5% level of significance using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS) version 23 (IBM, Armonk, NY, USA). A post hoc test was performed using the Duncan's New Multiple Range Test.

Results

Fungi identification

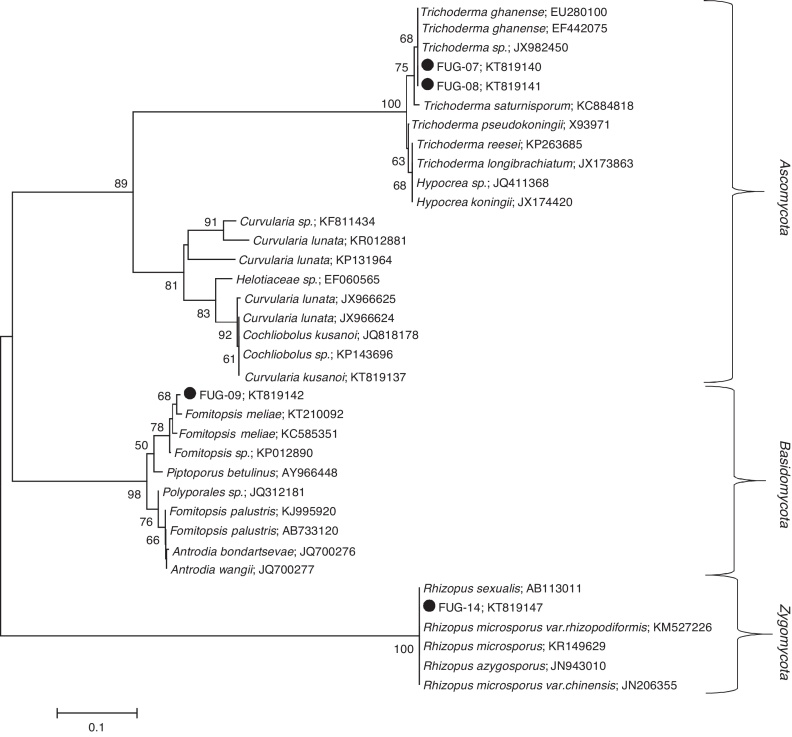

Three indigenous fungal species isolated from gold and gemstone mining sites were identified. The ITS-based taxonomic assignment of the fungal strains confirmed the identities of Fomitopsis meliae, Trichoderma ghanense (two isolates) and Rhizopus microsporus (Table 1). The isolation sources of the species revealed the presence of two genera – Fomitopsis and Trichoderma from Itagunmodi, the gold mining site and Rhizopus from the gemstone mine site. The evolutionary relatedness of the isolates with similar GenBank sequences further confirmed the identities of the strains (Fig. 1).

Table 1.

Taxonomic identification of fungal species with similarity on the UNITE ITS database.

Fig. 1.

Unrooted neighbour-joining tree of fungal species. Sequences obtained in this study are indicated shaded circles (●). Neighbour-joining tree was constructed in Mega (Version 6) by using the Tamura–Nei substitution model and a thousand bootstrap replications. Bootstrap values below 50 are not shown.

Growth response of tested fungal strains in heavy metal-rich media

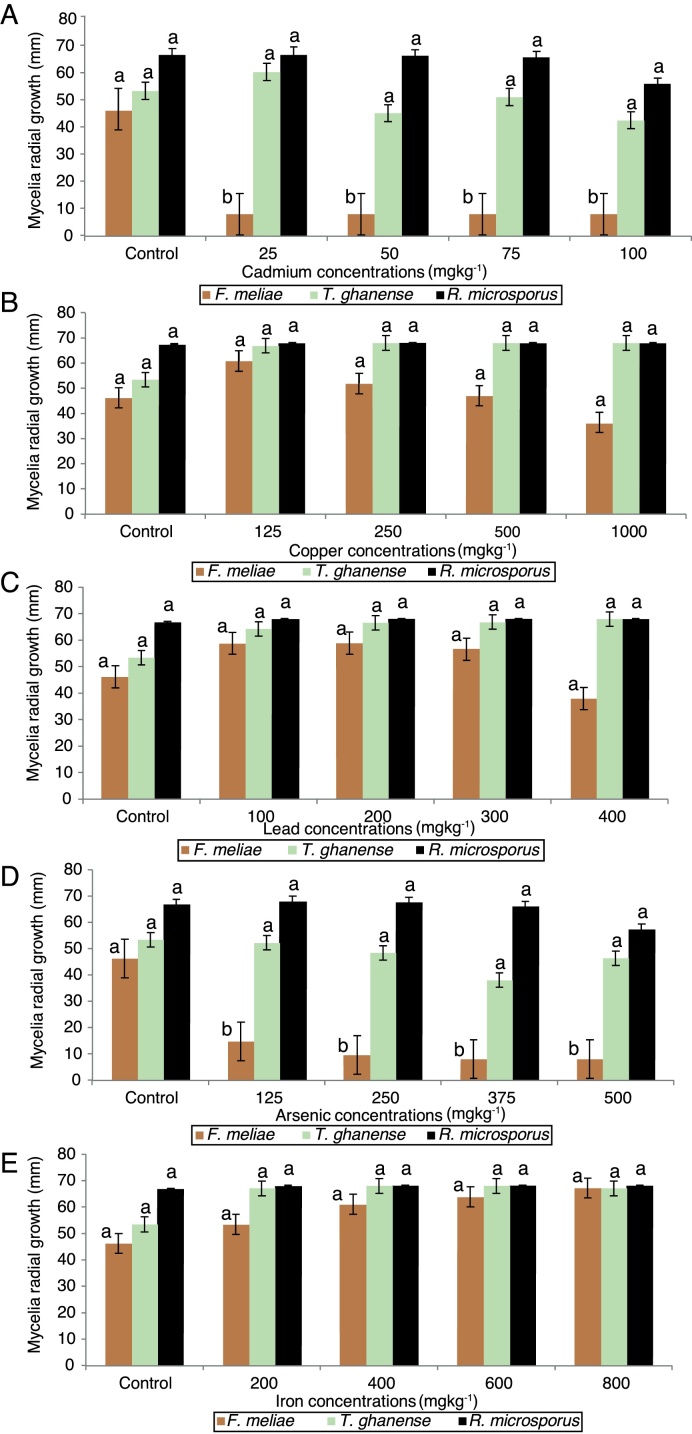

Mycelia growth response of F. meliae, T. ghanense and R. microsporus to varied concentrations of cadmium, copper, lead, arsenic and iron differed among the species (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Effect of varied concentrations of (A) Cd, (B) Cu, (C) Pb, (D) As and (E) Fe on fungi radial growth (mm) over 13 days incubation period. Key – F. meliae (Fomitopsis meliae); T. ghanense (Trichoderma ghanense) and R. microsporus (Rhizopus microsporus). Means of 3 replicates (± SE). Bars of the same fungal specie with different letters are significantly different (p < 0.05) according to Duncan's New Multiple Range Test.

On exposure to all cadmium and arsenic concentrations, F. meliae exhibited inhibited growth, with mycelia growths differing significantly (p < 0.05) compared to the control. Although, when exposed to varied Cu, Pb and Fe-enriched media, a divergent trait was displayed as F. meliae revealed no statistical (p > 0.05) difference in radial growth compared to the control. With respect to T. ghanense and R. microsporus strains, no statistical (p > 0.05) differences were obtained in the radial growth of the strains compared to their controls in Cd (25–100 mgkg−1), Cu (125–1000 mgkg−1), Pb (100–400 mgkg−1), As (125–500 mgkg−1) and Fe (200–800 mgkg−1) enriched media.

Overall, a growth response trend of Fe = Cu = Pb > As = Cd was observed among the fungal strains to heavy metal concentrations. In terms of their response in heavy metal rich-media, a trend showing T. ghanense > R. microsporus > F. meliae was observed. Generally, F. meliae tolerated 400 mgkg−1 Pb, 800 mgkg−1 Fe and 1000 mgkg−1 Cu concentrations, but revealed high inhibition to all Cd and As concentrations. On the other hand, T. ghanense and R. microsporus showed tolerance to elevated Cd (100 mgkg−1), Pb (400 mgkg−1), Fe (500 mgkg−1), As (800 mgkg−1) and Cu (1000 mgkg−1) concentrations. Comparing the response of these fungal species to heavy metal limits for contaminated soils, it was observed that the fungal species far exceeded the set permissible limits (Table 2) except F. meliae which was intolerant to all Cd and As concentrations.

Table 2.

Tolerance capability of fungal species to heavy metal concentrations (mgkg−1).

| Heavy metals | Fungi | Highest metal concentration (mgkg−1) tolerated in media | aWorld permissible limit in soils (mgkg−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cadmium | 0.41 | ||

| F. meliae | bNT | ||

| dT. ghanense | 100 | ||

| R. micosporus | 100 | ||

| Copper | 38.90 | ||

| F. meliae | 1000 | ||

| dT. ghanense | 1000 | ||

| R. micosporus | 1000 | ||

| Lead | 27.0 | ||

| F. meliae | 400 | ||

| dT. ghanense | 400 | ||

| R. micosporus | 400 | ||

| Arsenic | 20.0 | ||

| F. meliae | bNT | ||

| dT. ghanense | 500 | ||

| R. micosporus | 500 | ||

| Iron | c | ||

| F. meliae | 800 | ||

| dT. ghanense | 800 | ||

| R. micosporus | 800 | ||

Tolerance index rating of F. meliae, T. ghanense and R. microsporus to Cd, Cu, Pb, As and Fe concentrations

In ascertaining the tolerance of the test fungal strains to heavy metal concentrations (Fig. 2), we further evaluated the heavy metal tolerance levels of the fungal species. This was obtained by calculating the tolerance index of the test fungal species relative to their controls using the mycelia radial growth data in heavy metal enriched media (Eq. (1)).

The tolerance rating of F. meliae to 25–100 mgkg−1 cadmium and 125–500 mgkg−1 arsenic concentrations were observed to be very low, with tolerance indices ranging between 0.17 and 0.32 (Table 3). However, in Cu and Pb concentrations, F. meliae indicated high tolerance revealed by the very high tolerance index values of 1.02–1.32 in 125–500 mgkg−1 Cu and 0.96–1.28 in 100–300 mgkg−1 Pb. At higher Pb (400 mgkg−1) and Cu (1000 mgkg−1) concentrations, a decreased tolerance was indicated by F. meliae with tolerance index values of 0.67 and 0.78 respectively.

Table 3.

Tolerance index levels of fungal strains in metal-rich media concentrations.

| Heavy metals | Fungi | Concentrations (mgkg−1) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cadmium | 25 | 50 | 75 | 100 | |

| F. meliae | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | 0.17 | |

| aT. ghanense | 1.13 | 0.85 | 0.96 | 0.80 | |

| R. micosporus | 1.01 | 0.99 | 0.99 | 0.84 | |

| Copper | 125 | 250 | 500 | 1000 | |

| F. meliae | 1.32 | 1.12 | 1.02 | 0.78 | |

| aT. ghanense | 1.25 | 1.27 | 1.27 | 1.27 | |

| R. micosporus | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | |

| Lead | 100 | 200 | 300 | 400 | |

| F. meliae | 1.27 | 1.28 | 0.96 | 0.67 | |

| aT. ghanense | 1.20 | 1.25 | 1.25 | 1.27 | |

| R. micosporus | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | |

| Arsenic | 125 | 250 | 375 | 500 | |

| F. meliae | 0.32 | 0.21 | 0.17 | 0.17 | |

| aT. ghanense | 0.98 | 0.91 | 0.72 | 0.87 | |

| R. micosporus | 1.02 | 1.02 | 0.99 | 0.86 | |

| Iron | 200 | 400 | 600 | 800 | |

| F. meliae | 1.16 | 1.32 | 1.38 | 1.45 | |

| aT. ghanense | 1.25 | 1.27 | 1.27 | 1.25 | |

| R. micosporus | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | 1.02 | |

Tolerance index rating values indicate:

0.00–0.39 – very low metal tolerance.

0.40–0.59 – low metal tolerance.

0.60–0.79 – moderate metal tolerance.

0.80–0.99 – high metal tolerance.

1.00–>1.00 – very high metal tolerance.

Mean concentrations of taxonomically similar fungal identities in the study was used.

For T. ghanense and R. microsporus in all Cd concentrations, an indication of high to very high tolerances of 0.80–1.13 and a 0.84–1.01 tolerance index were obtained respectively. In addition, in Cu and Pb concentrations, the species indicated very high tolerance with index ranges of 1.02–1.27. In arsenic enriched-media, T. ghanense indicated moderate (0.72) to high (0.98) tolerance while R. microsporus indicated high to very high tolerance at 375 and 500 mgkg−1 and 125 and 250 mgkg−1 concentrations. Exceptionally, the three fungal species indicated remarkably high tolerances (tolerance index ranges of 1.02–1.45) in all varied Fe enriched-media concentrations, with F. meliae demonstrating the highest tolerance index of 1.45 at 800 mgkg−1.

When assessing the tolerance index of the fungal species, R. microsporus exhibited high to very high tolerance in all five heavy metal concentrations tested closely followed by T. ghanense which revealed high to very high tolerance in Cd, Cu, Pb and Fe concentrations except arsenic. F. meliae, on the other hand, indicated high to very high tolerance in Cu, Pb and Fe concentration exposures but very low tolerance in Cd and As concentrations. On the whole, the tolerance levels of the species to the heavy metals showed a decreasing trend of Fe > Cu > Pb > As > Cd.

Discussion

The occurrence of F. meliae, T. ghanense and R. microsporus on heavy metal contaminated gold and gemstone mining sites was confirmed in this study. The presence of fungal species in various contaminated/polluted sites with elevated heavy metal concentrations has been well documented. Specifically, Zafar et al.7 and Fazli et al.43 reported the occurrence of fungal strains in soils with elevated Cd, Cu, As and Zn concentrations. In addition, Anand et al.9 and Karcprzak and Malina29 confirmed the presence of fungi in heavy metal polluted soils. Iram et al.,12 Iskandar et al.,21 and López and Vázquez23 also affirmed the occurrence of fungal species in sewage sludge water plants, heavy metal contaminated freshwater ecosystem and sewage and industrial waste waters respectively. Furthermore, Mo et al.,44 Srivastava et al.45 and Babu et al.46 confirmed the existence of fungal strains in Pb and As polluted sites and mine tailings soils.

Of more importance is the marked tolerance displayed by these fungal species to heavy metals. Fungal species tolerate metals6, 15, 47 and thrive at elevated metal concentrations.9, 24, 48 In particular, indigenous filamentous fungi isolated from contaminated sites have shown tolerance to heavy metals.12, 18, 19, 49 This exceptional trait may be attributed to the isolates’ tolerance strategies to elevated heavy metal contaminations. Fomina et al.,14 Turnau et al.,15 Gadd16 and Vala and Sutariya17 reported that these tolerance mechanisms include metal binding to cell walls, production of intracellular/extracellular enzymes, intracellular sequestration, extracellular metal sequestration and precipitation, suppressed influx, enhanced metal efflux, and complexation.

Remarkable heavy metal tolerance was demonstrated by R. microsporus and T. ghanense species. Trichoderma and Rhizopus species have been widely reported for their notable tolerance to various heavy metals at varied concentrations.7, 23, 31, 50 Some strains of Rhizopus and Trichoderma revealed high resistance to a range of heavy metals, such as Cd,11, 23, 26, 44, 50, 51 Cu,21, 26, 46 Pb26, 52 and As.17, 45 Vala and Sutariya17 reported that Rhizopus species were highly tolerant to 25 and 50 mgkg−1 As concentrations, which confirms the findings of this study. In addition, strains of Trichoderma tolerated Cd at 100 and 125 mgkg−153, 54 and Cu at 300 mgkg−1,23 500 mgkg−1,9 800 mgkg−121 and 1000 mgkg−145 concentrations. Furthermore, a strain of Trichoderma was found to tolerate Pb concentrations of 1000 mgkg−1 in medium.21

All three fungal species demonstrated extraordinary preference for Fe at all concentrations as observed in their tolerance index values. This may be ascribed to the fact that iron serves as a micronutrient and is crucial in many metabolic processes.55 In addition, Kosman,56 Philpott57 and Johnson58 found that fungal species have a high affinity and capacity to take up Fe in various forms and variety. Aznar and Dellagi55 and Neilands59 stated that most fungal strains synthesize and secrete siderophores (small organic compounds that bind ferric Fe with high affinity and specificity) which they utilize to extract Fe from their environment. Furthermore, according to Kosman56 microorganisms including fungi basically deploy three main strategies to increase iron solubility by acidifying the environment, reducing ferric iron to a more soluble ferrous form and secreting soluble iron-chelating molecules.

Overall, T. ghanense and R. microsporus exhibited higher tolerance in Cd, Cu, Pb and As-enriched media compared to F. meliae which specifically displayed sensitivity to all Cd and As concentrations. Studies confirm that differing levels of metal resistance have been demonstrated by different fungal species isolated from the same source of metal-contaminated sites.12, 60, 61, 62, 63, 64 This may be ascribed to variations in the tolerance mechanism utilized by the fungal species7 which is individually dependent.65 In addition, the evident sensitivity to all Cd and As concentrations displayed by F. meliae may be attributed to the known toxicity of these heavy metals as reported.66, 67, 68

Conclusion

Indigenous filamentous fungal species from gold and gemstone mine sites exhibited remarkable tolerance in heavy metal-rich media. Exposures of F. meliae, T. ghanense and R. microsporus to elevated Cu, Pb and Fe levels revealed high tolerance with index values >1. Furthermore, T. ghanense and R. microsporus demonstrated extraordinary tolerance for As and Cd concentrations with a tolerance index >1 at 25 mgkg−1 Cd and 50 mgkg−1 As. These exceptional traits displayed by these fungal species to elevated heavy metal levels may indicate the bioremediative potentials inherent in the indigenous filamentous fungal species.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study acknowledges the North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa for the financial support and appreciates Mr. Obinna Ezeokoli for assisting with the molecular aspect of the work and Mr. Adesanya Adebowale for the statistical analysis.

Associate Editor: Valeria Oliveira

References

- 1.Oladipo O.G., Olayinka A., Awotoye O.O. Maize (Zea mays L.) performance in organically remediated mine site soils. J Environ Manage. 2016;182:435–442. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.07.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chirakkara R., Cameselle C., Reddy K. Assessing the applicability of phytoremediation of soils with mixed organic and heavy metal contaminants. Rev Environ Sci Biotechnol. 2016;15(2):299–326. [Google Scholar]

- 3.de la Cueva S.C., Rodríguez C.H., Cruz N.O.S., Contreras J.A.R., Miranda J.L. Changes in bacterial populations during bioremediation of soil contaminated with petroleum hydrocarbons. Water Air Soil Pollut. 2016;227(3):1–12. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oladipo O.G., Awotoye O.O., Olayinka A., Ezeokoli O.T., Maboeta M.S., Bezuidenhout C.C. Heavy metal tolerance potential of Aspergillus strains isolated from mining sites. Biorem J. 2016;(20):287–297. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fu Y., Viraraghavan T. Fungal decolorization of dye wastewaters: a review. Bioresour Technol. 2001;79:251–262. doi: 10.1016/s0960-8524(01)00028-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baldrian P. Interactions of heavy metals with white-rot fungi. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2003;32:78–91. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zafar S., Aqil F., Ahmad I. Metal tolerance and biosorption potential of filamentous fungi isolated from metal contaminated agricultural soil. Bioresour Technol. 2007;98:2557–2561. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2006.09.051. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shukla D., Vankar P.S. Role of Trichoderma species in bioremediation process: biosorption studies on hexavalent chromium. In: Gupta V.K., Schmoll M., Herrera-Estrella A., Upadhyay R.S., Druzhinina I., Tuohy M.G., editors. Vol 30. Elsevier Publishers; USA: 2014. pp. 405–414. (Biotechnology and Biology of Trichoderma). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Anand P., Isar J., Saran S., Saxena R.K. Bioaccumulation of copper by Trichoderma viride. Bioresour Technol. 2006;97:1018–1025. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2005.04.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ruta L., Paraschivescu C., Matache M., Avramescu S., Farcasanu I.C. Removing heavy metals from synthetic effluents using “kamikaze” Saccharomyces cerevisiae cells. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2010;85:763–771. doi: 10.1007/s00253-009-2266-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Puglisi I., Faedda R., Sanzaro V., Lo Piero A.R., Petrone G., Cacciola S.O. Identification of differentially expressed genes in response to mercury I and II stress in Trichoderma harzianum. Gene. 2012;506:325–330. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.06.091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Iram S., Zaman A., Iqbal Z., Shabbir R. Heavy metal tolerance of fungus isolated from soil contaminated with sewage and industrial wastewater. Pol J Environ Stud. 2013;22(3):691–697. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Vadkertiova R., Slavikova E. Metal tolerance of yeasts isolated from water, soil and plant environments. J Basic Microbiol. 2006;46:145–152. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200510609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fomina M.A., Alexander I.J., Colpaert J.V., Gadd G.M. Solubilization of toxic metal minerals and metal tolerance of mycorrhizal fungi. Soil Biol Biochem. 2005;37:851–866. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turnau K., Orlowska E., Ryszka P. Role of mycorrhizal fungi in phytoremediation and toxicity monitoring of heavy metal rich industrial wastes in southern Poland. Soil Water Pollut. 2006;23(3):533–551. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gadd G.M. Geomycology: biogeochemical transformations of rocks, minerals, metals and radionuclides by fungi, bioweathering and bioremediation. Mycol Res. 2007;111:43–49. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2006.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vala A.K., Sutariya V. Trivalent arsenic tolerance and accumulation in two facultative marine fungi. Jundishapur J Microbiol. 2012;5(4):542–545. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gadd G.M., Sayer G.M. Fungal transformation of metals and metalloids. In: Lovely D.R., editor. Environmental Microbe–Metal Interactions. American Soc Microbiol; 2000. pp. 237–256. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Malik A. Metal bioremediation through growing cells. Environ Int. 2004;30:261–278. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2003.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Machado M.D., Santos M.S.F., Gouveia C., Soares H.M.V.M., Soares E.V. Removal of heavy metals using a brewer's yeast strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the flocculation as a separation process. Bioresour Technol. 2008;99:2107–2115. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2007.05.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Iskandar N.L., Zainudin N.A., Tan S.G. Tolerance and biosorption of copper (Cu) and lead (Pb) by filamentous fungi isolated from a freshwater ecosystem. J Environ Sci (China) 2011;23:824–830. doi: 10.1016/s1001-0742(10)60475-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Muñoz A.J., Ruiz E., Abriouel H. Heavy metal tolerance of microorganisms isolated from wastewaters: identification and evaluation of its potential for biosorption. Chem Eng J. 2012;210:325–332. [Google Scholar]

- 23.López E.E., Vázquez C. Tolerance and uptake of heavy metals by Trichoderma atroviride isolated from sludge. Chemosphere. 2003;50:137–143. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(02)00485-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deng Z., Cao L., Gaur A., Adholeya A. Prospects of arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi in phytoremediation of heavy metal contaminated soils. Curr Sci. 2004;86(4):528–534. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Cecia A., Maggia O., Pinzarib F., Persiani A.M. Growth responses to and accumulation of vanadium in agricultural soil fungi. Appl Soil Ecol. 2012;58:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Volesky B. Advances in biosorption of metals: selection of biomass types. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 1994;14:291–302. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.1994.tb00102.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harman G.E., Lorito M., Lynch J.M. Uses of Trichoderma spp. to remediate soil and water pollution. Adv Appl Microbiol. 2004;56:313–330. doi: 10.1016/S0065-2164(04)56010-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ezzi M.I., Lynch J.M. Biodegradation of cyanide by Trichoderma spp. and Fusarium spp. Enzyme Microb Technol. 2005;36:849–854. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Karcprzak M., Malina G. The tolerance and Zn2+, Ba2+ and Fe2+ accumulation by Trichoderma atroviride and Mortierella exigua isolated from contaminated soil. Can J Soil Sci. 2005;85:283–290. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guillermina M., Romero M., Cazau M., Bucsinszky A. Cadmium removal capacities of filamentous soil fungi isolated from industrially polluted sediments, in La Plata (Argentina) World J Microbiol Biotechnol. 2002;18(9):817–820. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Harman G.E., Howell C.R., Viterbo A., Chet I., Lorito M. Trichoderma species opportunistic, a virulent plant symbionts. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:43–56. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Akhtar K., Khalid A., Akhtar M., Ghauri M. Removal and recovery of uranium from aqueous solutions by Ca-alginate immobilized Trichoderma harzianum. Bioresour Technol. 2009;100(20):4551–4558. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2009.03.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zeng X., Su S., Jiang X., Li L., Bai L., Zhang Y. Capability of pentavalent arsenic bioaccumulation and biovolatilization of three fungal strains under laboratory conditions. Clean: Soil Air Water. 2010;38:238–241. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tripathi P., Singh A.M., Chauhan P.S. Trichoderma: a potential bioremediator for environmental clean up. Clean Technol Environ Policy. 2013;15(4):541–550. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Oladipo O.G., Olayinka A., Awotoye O.O. Ecological impact of mining on soils of Southwestern Nigeria. Environ Exp Biol. 2014;12:179–186. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Samson R.A., Hoekstra E.S., van Oorschot C.A.N. Institute of the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts Science; Amsterdam, The Netherlands: 1984. Introduction of Food-Borne Fungi; p. 248 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 37.White T.J., Bruns T., Lee S., Taylor J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In: Innis M.A., Gelfand D.H., Sninsky J.J., White T.J., editors. PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications. Academic Press, Inc.; New York: 1990. pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Edgar R.C. MUSCLE: multiple sequence alignment with high accuracy and high throughput. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:1792–1797. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tamura K., Stecher G., Peterson D., Filipski A., Kumar S. MEGA6: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis version 6.0. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:2725–2729. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xia X. DAMBE5: a comprehensive software package for Data Analysis in Molecular Biology and Evolution. Mol Biol Evol. 2013;30:1720–1728. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Food and Agricultural Organization of the United Nations (FAO) FAO; Rome, Italy: 1984. Plant Production and Protection Series – Agroclimatological Data for Africa. Vol 1: Countries North of the Equator. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kabata-Pendias A. 4th ed. CRC Press, Taylor & Francis Gp; Florida: 2011. Trace Elements in Soils and Plants. 534 pp. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fazli M.M., Soleimani N., Mehrasbi M., Darabian S., Mohammadi J., Ramazani A. Highly cadmium tolerant fungi: their tolerance and removal potential. J Environ Health Sci Eng. 2015:13–19. doi: 10.1186/s40201-015-0176-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Mo M.H., Chen W.M., Zhang K.Q. Heavy metal tolerance of nematode-trapping fungi in lead-polluted soils. Appl Soil Ecol. 2006;31:1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Srivastava P.K., Vaish A., Dwivedi S., Chakrabarty D., Singh N. Biological removal of arsenic pollution by soil fungi. Sci Total Environ. 2011;409:2430–2442. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Babu A.G., Shea P.J., Oh B.T. Trichoderma sp. PDR1-7 promotes Pinus sylvestris reforestation of lead-contaminated mine tailing sites. Sci Total Environ. 2014;476–477:561–567. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2013.12.119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Qazilbash A.A. Isolation and characterization of heavy metal tolerant biota from industrially polluted soils and their role in bioremediation. Biol Sci. 2004;41:210–256. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Adriaensen K., Vrålstad T., Noben J.P., Vangronsveld J., Colpaert J.V. Copper-adapted Suillus luteus, a symbiotic solution for pines colonizing Cu mine spoils. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2005;71:7279–7284. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.11.7279-7284.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ashida J. Adaptation of fungi to metal toxicants. Annu Rev Phytopathol. 1965;3:153–174. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Babich H., Stotzky G. Effect of cadmium on fungi and on interactions between fungi and bacteria in soil: influence of clay minerals and pH. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1977;33:1059–1066. doi: 10.1128/aem.33.5.1059-1066.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Townsley C.C., Ross I.S., Atkins A.S. Biorecovery of metallic residues from various industrial effluents using filamentous fungi. In: Lawrence R.W., Branion R.M.R., Ebner H.G., editors. Fundamental Appl Biohydrometallr. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1986. [Google Scholar]

- 52.Babu A.G., Shim J., Bang K.S., Shea P.J., Oh B.T. Trichoderma virens PDR-28: a heavy metal-tolerant and plant growth-promoting fungus for remediation and bioenergy crop production on mine tailing soil. J Environ Manag. 2014;132:129–134. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2013.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Baldrian P., Gabriel J., Nerud F. Effect of cadmium on the ligninolytic activity of Stereum hirsutum and Phanerochaete chrysosporium. Folia Microbiol. 1996;41:363–367. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Datta B. Heavy metal tolerance of filamentous fungi isolated from metal-contaminated soil. Asian J Microbiol Biotechnol Environ Sci. 2015;17(4):965–968. [Google Scholar]

- 55.Aznar A., Dellagi A. New insights into the role of siderophores as triggers of plant immunity: what can we learn from animals? J Exp Bot. 2015;66(11):3001–3010. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erv155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kosman D.J. Molecular mechanisms of iron uptake in fungi. Mol Microbiol. 2003;47(5):1185–1197. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03368.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Philpott C.C. Iron uptake in fungi: a system for every source. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2006;1763(7):636–645. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Johnson L. Iron and siderophores in fungal–host interactions. Mycol Res. 2008;112:170–183. doi: 10.1016/j.mycres.2007.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Neilands J.B. Siderophores: structure and function of microbial iron transport compounds. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(45):26723–26726. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.26723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Vala A.K., Anand N., Bhatt P.N., Joshi H.V. Tolerance and accumulation of hexavalent chromium by two seaweed associated Aspergilli. Mar Pollut Bull. 2004;48(9–10):983–985. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2004.02.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Taboski M.A., Rand T.G., Piorko A. Lead and cadmium uptake in the marine fungi Corollospora lacera and Monodictys pelagica. FEMS Microbiol Ecol. 2005;53(3):445–453. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2005.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Sanyal A., Rautaray D., Bansal V., Ahmad A., Sastry M. Heavy metal remediation by a fungus as a mean of lead and cadmium carbonate crystals. Langmuir. 2005;2(21):7220–7224. doi: 10.1021/la047132g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Iram S., Ahmad I., Javed B. Fungal tolerance to heavy metals. Pak J Bot. 2009;41(5):2583–2594. [Google Scholar]

- 64.Li T., Liu M.J., Zhang X.T., Zhang H.B., Sha T., Zhao Z.W. Improved tolerance of maize (Zea mays L.) to heavy metals by colonization of a dark septate endophyte (DSE) Exophiala pisciphila. Sci Total Environ. 2011;409:1069–1074. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2010.12.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Srinath T., Verma T., Ramteke P., Garg K. Chromium biosorption and bioaccumulation by chromate resistant bacteria. Chemosphere. 2002;(48):427–435. doi: 10.1016/s0045-6535(02)00089-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.DalCorso G., Farinati S., Maistri S., Furini A. How plants cope with cadmium: staking all on metabolism and gene expression. J Integr Plant Biol. 2008;50:1268–1280. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7909.2008.00737.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bhattacharya S.K., Gupta S., Debnath U.C., Ghosh D., Chattopadhyay, Mukhopadhyay A. Arsenic bioaccumulation in rice and edible plants and subsequent transmission through food chain in Bengal basin: a review of the perspectives for environmental health. Toxicol Environ Chem. 2012;94:429–441. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Tamás M.J., Sharma S.K., Ibstedt S., Jacobson T., Christen P. Heavy metals and metalloids as a cause for protein misfolding and aggregation. Biomolecules. 2014;4:252–267. doi: 10.3390/biom4010252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]