Abstract

Background

HRQOL reflects a patient’s disease burden, treatment effectiveness, and health status and is summarized by physical, mental, and kidney disease-specific scales among ESRD patients. While on average HRQOL improves post-KT, the degree of change depends on the ability of the patient to withstand the stressor of dialysis versus the ability to tolerate the intense physiologic changes of KT. Frail KT recipients may be extra vulnerable to either of these stressors, thus affecting change in HRQOL after KT.

Methods

We ascertained frailty as well as physical, mental, and kidney disease-specific HRQOL in a multicenter prospective cohort of 443 KT recipients (5/2014–5/2017) using KDQOL. We quantified the short-term (3 month) rate of post-KT HRQOL change by frailty status using adjusted mixed-effects linear regression models.

Results

Mean HRQOL scores at KT were 43.3(SD=9.6) for physical, 52.8(SD=8.9) for mental, and 72.6(SD=12.8) for kidney disease-specific HRQOL; frail recipients had worse physical (p<0.001) and kidney disease-specific HRQOL (p=0.001), but similar mental HRQOL (p=0.43). Frail recipients experienced significantly greater rates of improvement in physical HRQOL (frail: 1.35points/month 95%CI:0.65,2.05; nonfrail: 0.34points/month,95%CI:−0.17,0.85; p=0.02) and kidney disease-specific HRQOL (frail: 3.75points/month, 95%CI:2.89,4.60; nonfrail: 2.41points/month, 95%CI:1.78,3.04; p=0.01), but no difference in mental HRQOL (frail: 0.54points/month, 95%CI:−0.17,1.25; nonfrail: 0.46points/month, 95%CI:−0.06,0.98; p=0.85) post-KT.

Conclusions

Despite decreased physiologic reserve, frail recipients experience improvement in post-KT physical and kidney disease-specific HRQOL better than nonfrail recipients.

Introduction

Health-related quality of life (HRQOL) is an important indicator of a patient’s disease burden, treatment effectiveness, and health status (1, 2). Poor HRQOL is associated with increased risks of hospitalizations, graft failure, and mortality in both patients with end-stage renal disease (ESRD) and those undergoing kidney transplantation (KT) (3–6). On average, HRQOL improves after KT (7–9); improvements in HRQOL are particularly important in the months immediately following KT because short-term dynamic changes in HRQOL are associated with subsequent morbidity and mortality (3, 6). However, the degree of change in HRQOL depends on the ability of the patient to withstand the stressor of dialysis versus the ability to tolerate the intense physiologic changes of KT (10). These stressors likely have a different impact on physical, mental, and kidney disease-specific HRQOL, the constituent components of HRQOL for ESRD patients. KT may have a greater impact on kidney disease-specific HRQOL by improving symptoms, effects, and burden, but the surgical stressor may have an adverse effect on physical and mental HRQOL by reducing energy and physical functioning in the first few months. The phenotype of patients who will have short-term improvements in physical, mental, and kidney disease-specific HRQOL remains poorly understood.

Frailty, a phenotype of decreased physiologic reserve and vulnerability to stressors, (11) has been associated with adverse clinical outcomes among dialysis patients including poor cognitive function, falls, hospitalizations, and mortality (12–15). Our previous work demonstrated that frail patients with ESRD are more than twice as likely to experience a decline in HRQOL while awaiting KT (16), resulting in worse HRQOL compared to their nonfrail peers at the time of KT and frailty is associated with post-KT adverse outcomes including delayed graft function, longer length of stay, early hospital readmission, immunosuppression intolerance, and mortality (17–20). Candidates who are frail prior to KT may be extra vulnerable to the stressor of dialysis, but may also be extra vulnerable to the stressors of KT and post-KT immune system dysregulation. As such, it is unclear whether KT recipients who are frail at the time of KT experience improvements in physical, mental, and kidney disease-specific HRQOL immediately after KT at the same rate as nonfrail recipients.

The goals of this study were to 1) compare the pre-KT physical, mental, and kidney disease-specific HRQOL by frailty status at the time of KT, 2) describe the short-term change in physical, mental, and kidney disease-specific HRQOL in the first 3 months post-KT, 3) quantify the association between pre-KT frailty and the rate of change in physical, mental, and kidney disease-specific HRQOL following KT.

Materials and Methods

Study Design

This was a prospective, multicenter longitudinal cohort study of 443 KT recipients at Johns Hopkins Hospital (n=370), Baltimore, Maryland (5/2014–5/2017) and the University of Michigan (N=73), Ann Arbor, Michigan (3/2015–6/2016). Study participants were enrolled at admission for KT, just prior to transplantation, and frailty and HRQOL (described below) were ascertained now. Recipient and donor factors (age, sex, race, education level, donor type, delayed graft function [DGF], and kidney donor profile index [KDPI]) were abstracted from the medical chart. A Charlson comorbidity index adapted for patients with ESRD was calculated based on self-reported comorbidities at the time of KT (21). Subsequent post-KT assessments of HRQOL were conducted during routine postoperative clinical follow-up visits. This study was approved by the Johns Hopkins Institutional Review Board (IRB number: NA_00015758).

Frailty

At admission for KT, frailty was measured as defined and validated by Fried and colleagues in older adults (11, 22–31) and by our group in ESRD and KT populations (12–14, 17–20, 32–34). The phenotype was based on 5 components: shrinking (self-report of unintentional weight loss of more than 10 lbs. in the past year based on dry weight), weakness (grip strength below an established cutoff based on gender and BMI), exhaustion (self-report), low physical activity (kcals/week below an established cutoff), and slowed walking speed (walking time of 15 feet below an established cutoff by gender and height) (11). Participants received a score of 0 or 1, representing the absence or presence respectively of each of the 5 components. The aggregate frailty score was calculated as the sum of the component scores (range 0–5); nonfrail was defined as a score of 0 or 1, intermediate frailty was defined as a score of 2, and frailty was defined as a score of 3 or higher (12–14, 17–20, 32–34). In this study, we empirically combined intermediately frail and frail groups because both groups were associated with a similar change in post-KT HRQOL; we refer to this group as frail throughout the rest of this article.

HRQOL Assessment

We assessed HRQOL using the Kidney Disease Quality of Life instrument short form (KDQOL-SF) version 1.3 (35, 36), which has been validated in KT recipients (37). The KDQOL-SF consists of a generic core [Short Form-36 (SF-36)], as well as 11 multi-item kidney disease-specific scales. The SF-36 consists of 8 multi-item scales that address domains of physical and mental health: physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health problems, bodily pain, general health, emotional well-being, role limitations due to emotional health problems, social functioning, and energy. We calculated SF-36 domain scores per published guidelines; converting question items to a 0–100 scale with higher transformed scores reflecting better HRQOL. These SF-36 domains scores were aggregated into a physical component and a mental component with summary scores standardized to the 1998 U.S. adult population for comparison (ie, mean 50, standard deviation 10) (35, 38). The kidney disease-specific domains included: symptoms of ESRD, effects of ESRD on daily life, burden of ESRD, cognitive function, quality of social interactions, sleep, and social support. We linearly converted kidney disease-specific domain scores to a 0–100 scale in a similar manner to that used for the SF-36 domain scores. A kidney disease-specific component summary score was generated as an average of these kidney disease-specific scales as has previously been reported (39, 40).

Frailty and HRQOL

Multivariable linear regression models were used to examine the relationship between frailty and physical, mental, and kidney disease-specific HRQOL at KT. We used paired t tests to assess the within-individual changes in HRQOL scores among frail and nonfrail recipients at KT compared to scores at 1 month and 3 months post-KT. Student t tests were also used to compare HRQOL scores between frail and nonfrail recipients at these follow-up intervals. Multilevel mixed effects linear regression models, with random slopes and intercepts, were used to perform a longitudinal analysis of post-KT HRQOL change among frail and nonfrail recipients. Models also included an interaction term for time of follow-up and frailty status at KT to test whether the rates of change in HRQOL in the frail and nonfrail populations were statistically different. Models were adjusted for pre-KT HRQOL as well as potential predictors of post-KT HRQOL including: age, sex, race, education level, donor type, and the presence of comorbidities measured by the Charlson comorbidity index. Using a similar approach, we estimated the rate of change of physical, mental, and kidney-disease specific HRQOL by donor type, DGF, and KDPI.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical significance was defined as p<0.05 for all analyses. All analyses were performed using Stata version 14.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX).

Results

Study Population

Among 443 KT recipients, the mean age was 52.0 years (standard deviation (SD)=14.1, range 19.9–86.0), 37.3% were female, 38.2% were African-American, 38.2% had a high school education or less, 34.8% received a live donor KT, and 37.0% were categorized as frail/intermediate frail. The median follow-up post-KT was 7.7 months. Prior to KT, 73.27% of participants were undergoing hemodialysis, 58.91% were undergoing peritoneal dialysis; 14.36% were preemptive KT recipients. The median time on dialysis for those undergoing dialysis was 3.26 years (IQR: 1.56–5.62).

HRQOL at KT

The mean HRQOL scores at the time of KT was 43.3 points (SD=9.6) for physical HRQOL, 52.8 points (SD=8.9) for mental HRQOL, and 72.6 points (SD=12.8) for kidney disease-specific HRQOL. HRQOL at KT did not differ by age, sex, race, educational status, donor type, or pre-KT dialysis; except for slightly better mental HRQOL scores (55.0 vs. 51.7, p<0.001) and kidney disease-specific HRQOL (75.6 vs. 72.8, p=0.04) among African-Americans (Table 1).

Table 1.

Physical, Mental, and Kidney Disease-Specific Health-Related Quality of Life at Kidney Transplantation by Recipient and Donor Factors.

| Physical HRQOL Mean (SD) |

p value | Mental HRQOL Mean (SD) |

P value | Kidney disease-specific HRQOL Mean (SD) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <65 | 43.11 (9.68) | 0.83 | 52.45 (8.87) | 0.02 | 73.62 (13.84) | 0.49 |

| ≥65 | 42.86 (9.67) | 54.97 (7.54) | 74.76 (12.32) | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 43.44 (9.43) | 0.31 | 52.89 (8.57) | 0.80 | 73.07 (13.61) | 0.13 |

| Female | 42.42 (10.06) | 53.12 (8.83) | 75.18 (13.33) | |||

| Race | ||||||

| Non-AA | 42.79 (9.50) | 0.47 | 51.67 (8.74) | <0.001 | 72.76 (13.50) | 0.04 |

| AA | 43.50 (9.94) | 54.99 (8.15) | 75.55 (13.45) | |||

| Education status | ||||||

| >High school | 43.16 (9.84) | 0.80 | 52.71 (8.73) | 0.44 | 73.85 (13.17) | 0.99 |

| ≤High School | 42.91 (9.42) | 53.40 (8.55) | 73.86 (14.13) | |||

| Donor type | ||||||

| DDKT | 43.23 (9.65) | 0.62 | 53.52 (8.47) | 0.07 | 73.90 (13.90) | 0.91 |

| LDKT | 42.72 (9.74) | 51.84 (8.96) | 73.75 (14.04) | |||

| Dialysis type | ||||||

| HD | 42.73 (9.89) | 53.47 (9.07) | 73.65 (14.02) | |||

| PD | 42.41 (9.18) | 0.31 | 53.88 (7.01) | 0.23 | 74.24 (11.57) | 0.69 |

| Preemptive | 44.33 (9.47) | 51.91 (8.16) | 75.02 (13.22) |

(Key: HRQOL= Health-Related Quality of Life, AA= African-American, DDKT= Deceased Donor Kidney Transplantation, LDKT= Live donor Kidney Transplantation), HD=Hemodialysis, PD=Peritoneal Dialysis. All measures of HRQOL made using the Kidney Disease Quality of Life instrument short form (KDQOL-SF) (35). Higher scores indicate better HRQOL.

Frailty and HRQOL at the Time of KT

At the time of KT, frail KT recipients had significantly worse scores in physical HRQOL (39.3 vs. 45.6, p<0.001) and kidney disease-specific HRQOL (70.2 vs. 76.1, p<0.001), but not mental HRQOL (52.4 vs. 53.1, p=0.43) (Table 2). After adjusting for recipient and donor factors, frailty was associated with significantly worse physical HRQOL (−6.31 points; 95% CI: −8.16, −4.46, p<0.001), and worse kidney disease-specific HRQOL (−6.53 points; 95% CI: −9.17, −3.89, p<0.001) but no difference in mental HRQOL (−1.21 points; 95% CI: −2.96, 0.22, p=0.18) at the time of KT (Table 3); there were no differences in physical, mental, or kidney disease-specific HRQOL at the time of KT by donor type or KDPI.

Table 2.

Physical, Mental, and Kidney Disease-Specific Health-Related Quality of Life Pre and Postkidney Transplantation by Frailty Status.

| Pre-KT | Post-KT | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||

| 1-month change | 3-month change | |||||

|

| ||||||

| Nonfrail | Frail | Nonfrail | Frail | Nonfrail | Frail | |

|

| ||||||

| Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | Mean (SD) | |

| Physical HRQOL | 45.55 (8.66) | 39.31 (9.88) | −7.26 (9.29)* | −5.25 (10.03)* | 0.97 (9.48) | 4.06 (8.78)* |

| Mental HRQOL | 53.06 (8.47) | 52.36 (9.60) | 1.59 (9.77)* | 1.47 (9.98) | 1.61 (9.20)* | 1.60 (10.10) |

| Domains | ||||||

| Physical functioning | 77.02 (20.22) | 61.61 (25.59) | −12.46 (22.77)* | −11.94 (28.12)* | 2.35 (19.56) | 7.29 (24.19)* |

| Role limitations due to physical health problems | 55.88 (38.02) | 41.93 (38.41) | −28.66 (45.58)* | −22.36 (46.90)* | 3.28 (48.99) | 13.97 (45.31)* |

| Bodily pain | 79.90 (23.13) | 46.00 (23.11) | −19.57 (30.69)* | −14.60 (30.23)* | 0.19 (26.47) | 4.00 (27.60) |

| General health | 56.67 (20.45) | 43.60 (23.12) | 8.49 (17.71)* | 11.12 (18.98)* | 6.98 (19.22)* | 10.07 (20.11)* |

| Emotional well being | 83.21 (14.44) | 80.79 (15.74) | 2.46 (16.30)* | 3.29 (16.97) | 3.01 (14.45) | 3.56 (15.22) |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | 84.50 (29.50) | 79.54 (33.17) | 0.00 (37.89) | −3.14 (37.02) | 1.30 (39.77) | 3.33 (37.71) |

| Social functioning | 82.10 (23.43) | 76.83 (24.83) | −15.56 (29.66)* | −12.75 (31.27)* | 2.68 (24.59) | 1.43 (29.14) |

| Energy | 55.92 (22.85) | 45.37 (25.00) | −2.97 (24.60)* | 0.72 (28.57) | 5.81 (24.58)* | 11.36 (26.35)* |

|

| ||||||

| Kidney disease-specific HRQOL | 76.05 (12.53) | 70.23 (14.41) | 3.94 (10.64)* | 4.15 (11.92)* | 7.90 (10.87)* | 11.07 (12.31)* |

| Domains | ||||||

| Symptoms | 83.24 (12.45) | 77.83 (14.89) | 1.94 (11.62)* | 3.31 (13.96)* | 5.74 (11.30)* | 8.05 (13.28)* |

| Effects | 74.88 (17.91) | 68.02 (22.57) | 7.55 (19.80)* | 8.26 (21.61)* | 12.06 (17.59)* | 18.54 (21.08)* |

| Burden | 54.65 (28.41) | 45.91 (29.37) | 11.76 (26.39)* | 13.95 (25.70)* | 19.99 (27.61)* | 22.31 (30.37)* |

| Cognitive function | 86.26 (15.57) | 80.77 (19.88) | 2.35 (14.57) | 2.69 (17.43) | 5.10 (14.03)* | 6.81 (13.68)* |

| Social interaction | 83.92 (15.47) | 79.83 (16.78) | −2.85 (16.56)* | −0.44 (15.41) | 0.44 (14.48) | 3.29 (18.84) |

| Sleep | 64.58 (20.23) | 59.46 (22.80) | 1.76 (24.55) | −0.13 (22.38) | 6.64 (20.44)* | 11.34 (21.53)* |

| Social support | 84.69 (20.15) | 79.71 (22.03) | 4.47 (23.17)* | 0.68 (23.92) | 5.29 (22.17)* | 6.72 (22.10) |

(Key: HRQOL= Health-Related Quality of Life, KT= Kidney Transplantation). Unadjusted mean HRQOL scores were measured pre-KT and compared to scores at 1-month and 3-months post-KT.

indicates statistical significant changes in scores compared to KT. All measures of HRQOL made using the Kidney Disease Quality of Life instrument short form (KDQOL-SF) (35).

Table 3.

Association between Physical, Mental, and Kidney Disease-Specific Health-Related Quality of Life with Frailty Status at Kidney Transplantation.

| Frail vs. nonfrail | DDKK vs. LDKT | High vs. Low KDPI | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Points (95% CI) |

Points (95% CI) |

Points (95% CI) |

|

| Physical HRQOL | −6.31 (−8.16, −4.46) |

0.51 (−1.75, 2.77) |

−0.03 (−4.73, 4.66) |

| Mental HRQOL | −1.21 (−2.96, 0.22) |

0.08 (−1.90, 2.07) |

0.19 (−3.84, 4.23) |

| Domains: | |||

| Physical functioning | −14.17 (−18.58, −9.76) |

−2.03 (−7.42, 3.36) |

2.24 (−9.43, 13.90) |

| Role limitations due to physical health problems | −15.37 (−22.96, −7.78) |

2.66 (−6.27, 11.59) |

−2.89 (−21.00, 15.22) |

| Bodily pain | −9.45 (−14.33, −4.57) |

−2.18 (−7.97, 3.60) |

−1.24 (−13.57, 11.09) |

| General health | −11.76 (−15.94, −7.59) |

2.85 (−2.10, 7.79) |

−3.18 (−13.23, 6.89) |

| Emotional well being | −3.05 (−6.01, −0.09) |

−1.75 (−5.09, 1.60) |

−1.09 (−8.02, 5.83) |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | −5.28 (−11.46, 0.90) |

−2.31 (−9.39, 4.77) |

−0.96 (−15.82, 13.90) |

| Social functioning | −6.19 (−10.98, −1.41) |

3.84 (−1.73, 9.42) |

3.83 (−7.48, 15.13) |

| Energy | −11.66 (−16.30, −7.03) |

2.67 (−2.78, 8.12) |

2.49 (−8.86, 13.85) |

|

| |||

| Kidney disease-specific HRQOL | −6.53 (−9.17, −3.89) |

−2.08 (−5.06, 0.90) |

1.38 (−5.09, 7.86) |

| Domains: | |||

| Symptoms | −5.50 (−8.20, −2.79) |

−1.30 (−4.50, 1.89) |

0.22 (−6.43, 6.87) |

| Effects | −7.69 (−11.66, −3.72) |

−0.81 (−5.45, 3.82) |

1.51 (−8.39, 11.41) |

| Burden | −10.19 (−15.94, −4.44) |

−1.79 (−8.52, 4.95) |

−5.94 (−19.43, 7.55) |

| Cognitive function | −5.51 (−9.00, −2.02) |

−1.18 (5.19, 2.83) |

−1.49 (−9.90, 6.91) |

| Social interaction | −4.70 (−7.85, −1.56) |

−3.02 (−6.63, 0.59) |

6.01 (−1.55, 13.57) |

| Sleep | −6.29 (−10.56, −2.02) |

1.14 (−3.88, 6.16) |

5.23 (−5.32, 15.79) |

| Social support | −5.69 (−9.92, −1.47) |

−2.77 (−7.63, 2.08) |

3.69 (−6.63, 14.01) |

(Key: HRQOL= Health-Related Quality of Life, DDKT= Deceased Donor Kidney Transplantation, LDKT= Live Donor Kidney Transplantation). Separate linear models of HRQOL at KT by frailty status adjusted for age, sex, race, educational status, donor type. All measures of HRQOL made using the Kidney Disease Quality of Life instrument short form (KDQOL-SF) (35). Negative coefficients indicate worse HRQOL for frail KT recipients.

At the domain level, frail KT recipients had worse scores in physical functioning, role limitations due to physical health problems, bodily pain, general health, social functioning, energy, symptoms of disease, effects of disease on daily living, burden of disease, cognitive functioning, sleep, and social support after adjusting for recipient and donor factors.

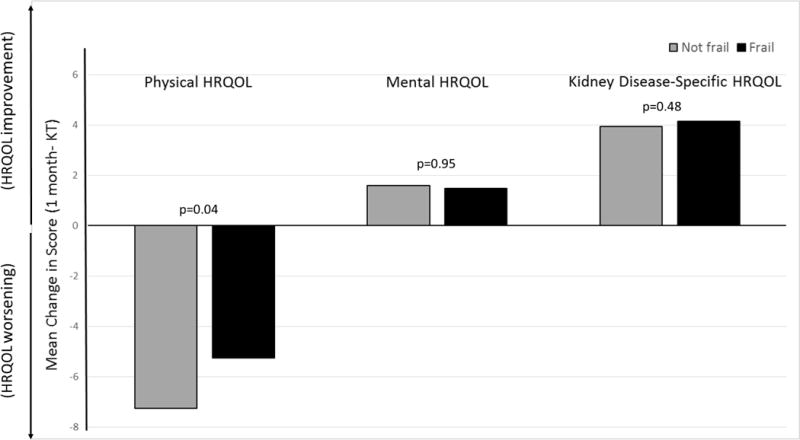

Frailty and Change in HRQOL at 1-month post-KT

There were statistically significant declines in physical HRQOL for both frail and nonfrail recipients (frail: −5.25 points, p<0.001; nonfrail: −7.26 points, p<0.001) at 1-month post-KT (Table 2); these declines were greater among those who were frail (p for interaction=0.04) (Figure 1). There was no change in mental HRQOL among frail recipients (1.47 points, p=0.145) and improvement in the nonfrail recipients (1.59 points, p=0.025) although there was no evidence of a difference in the changes in mental HRQOL scores by frailty status (p for interaction=0.95). There was significant improvement in kidney disease-specific HRQOL at 1-month for frail (4.15 points, p=0.001) and nonfrail recipients (3.94 points, p<0.001); these improvements were similar by frailty status (adjusted p for interaction=0.48).

Figure 1.

Mean Change in Health-Related Quality of Life from Kidney Transplantation to 1 Month post-KT by Frailty Status. (Key: HRQOL= Health-Related Quality of Life, KT= Kidney Transplantation). Mean 1-month changes in physical, mental, and kidney disease-specific HRQOL were calculated and compared by frailty status at KT. All measures of HRQOL were from the Kidney Disease Quality of Life instrument short form (KDQOL-SF) (35).

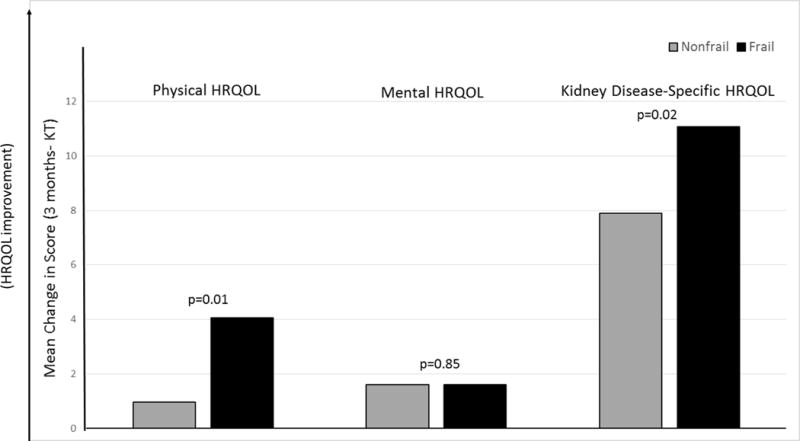

Frailty and Change in HRQOL at 3-months post-KT

There were statistically significant improvements in physical HRQOL among frail (4.06 points, p<0.001) but not nonfrail recipients (0.97 points, p=0.21) at 3-months post-KT (Table 2) and this 3-month improvement was significantly greater among frail recipients (p for interaction=0.01) (Figure 2). There were significant changes in 3-month mental HRQOL among frail and no change in nonfrail recipients (frail: 1.60 points, p=0.03; nonfrail: 1.61 points, p=0.19; p for interaction=0.85). There were statistically significant 3-month improvements in kidney disease-specific HRQOL for both frail and nonfrail recipients (frail: 11.07 points, p<0.001; nonfrail: 7.90 points, p<0.001) at 3-months post-KT and these improvements were greater among those who were frail (p for interaction=0.02). Among frail KT recipients, those who were <65 had a greater improvement in physical (p=0.02) and kidney disease-specific HRQOL (p=0.04) (Table 4); LDKT recipients had a greater improvement in physical HRQOL (p=0.009).

Figure 2.

Mean Change in Health-Related Quality of Life from Kidney Transplantation to 3 Months post-KT by Frailty Status. (Key: HRQOL= Health-Related Quality of Life, KT= Kidney Transplantation). Mean 3-month changes in physical, mental, and kidney disease-specific HRQOL were calculated and compared by frailty status at KT. All measures of HRQOL were from the Kidney Disease Quality of Life instrument short form (KDQOL-SF) (35).

Table 4.

3-Month Change in Physical, Mental, and Kidney Disease-Specific Health-Related Quality of Life Among Frail KT Recipients by Recipient and Donor Factors.

| Physical HRQOL Mean (SD) |

p value | Mental HRQOL Mean (SD) |

p value | Kidney disease-specific HRQOL Mean (SD) |

p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||||||

| <65 | 5.33 (8.80)* | 0.02 | 2.26 (9.82) | 0.31 | 12.55 (9.51)* | 0.04 |

| ≥65 | −0.50 (7.26) | −0.78 (11.08) | 5.17 (14.60) | |||

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 4.87 (8.10)* | 0.37 | 1.95 (9.89) | 0.74 | 12.44 (11.81) | 0.27 |

| Female | 2.94 (9.68) | 1.13 (10.55) | 9.13 (12.94) | |||

| Race | ||||||

| Non-AA | 5.36 (8.27)* | 0.06 | 2.45 (10.23) | 0.29 | 12.92 (11.42)* | 0.06 |

| AA | 1.09 (9.38) | −0.34 (9.77) | 7.04 (13.46)* | |||

| Education status | ||||||

| >High school | 5.64 (8.03)* | 2.27 (8.85) | 12.58 (11.68)* | |||

| ≤High School | 1.75 (9.45) | 0.07 | 0.62 (11.81) | 0.51 | 8.93 (13.05)* | 0.22 |

| Donor type | ||||||

| DDKT | 1.84 (8.43) | 0.009 | 1.29 (8.27) | 0.74 | 9.61 (12.65)* | 0.18 |

| LDKT | 7.97 (8.14)* | 2.15 (12.90) | 13.71 (11.44)* | |||

| Dialysis type | ||||||

| HD | 3.73 (7.94) | 2.90 (11.33) | 10.17 (13.26) | |||

| PD | −4.33 (10.43) | 0.002 | 3.51 (5.93) | 0.23 | 16.37 (14.24)* | 0.47 |

| Preemptive | 8.58 (6.39)* | −1.91 (7.83) | 10.43 (9.02)* |

(Key: HRQOL= Health-Related Quality of Life, AA= African-American, DDKT= Deceased Donor Kidney Transplantation, LDKT= Live Donor Kidney Transplantation, HD=Hemodialysis, PD=Peritoneal Dialysis). All measures of HRQOL made using the Kidney Disease Quality of Life instrument short form (KDQOL-SF) (35).

indicates statistical significant changes in scores compared to KT. Higher scores indicate greater change HRQOL.

Frailty and Rate of Change in post-KT HRQOL Adjusted for Recipient and Donor Factors

After adjusting for recipient and donor factors, there was a significantly greater rate of improvement over 3-months in post-KT physical HRQOL among frail recipients (frail: 1.35 points/month, 95% CI: 0.65, 2.05; nonfrail: 0.34 points/month, 95% CI: −0.17, 0.85; p for interaction=0.02) (Table 5). There were no changes in post-KT mental HRQOL regardless of recipient’s frailty status (frail: 0.54 points/month, 95% CI: −0.17, 1.25; nonfrail: 0.46 points/month, 95% CI: −0.06, 0.98; p for interaction=0.85). Frail and nonfrail KT recipients reported similar rates of improvement in kidney disease-specific HRQOL (frail: 3.75 points/month, 95% CI: 2.89, 4.60; nonfrail: 2.41 points/month, 95% CI: 2.89, 4.60; p for interaction=0.01).

Table 5.

Rates of Change in Posttransplant Health-Related Quality of Life within 3 Months by Frailty Status at Kidney Transplantation.

| Nonfrail | Frail | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Points/month (95% CI) | Points/month (95% CI) | Interaction p-value | |

| Physical HRQOL | 0.34 (−0.17, 0.85) | 1.35 (0.65, 2.05)* | 0.02 |

| Mental HRQOL | 0.46 (−0.06, 0.98) | 0.54 (−0.17, 1.25) | 0.85 |

| Domains: | |||

| Physical functioning | 0.72 (−0.46, 1.89) | 2.62 (1.02, 4.22)* | 0.06 |

| Role limitations due to physical health problems | −1.33 (−3.84, 1.17) | 1.55 (−1.86, 4.75) | 0.18 |

| Bodily pain | 0.92 (−0.56, 2.39) | 1.67 (−0.37, 3.70) | 0.56 |

| General health | 2.87 (1.82, 3.92)* | 4.93 (3.51, 6.35)* | 0.02 |

| Emotional well being | 0.98 (0.15, 1.81)* | 1.45 (0.32, 2.58)* | 0.51 |

| Role limitations due to emotional problems | −0.09 (−2.08, 1.90) | 0.49 (−2.22, 3.21) | 0.93 |

| Social functioning | 0.49 (−1.09, 2.07) | −0.07 (−2.24, 2.10) | 0.68 |

| Energy | 1.91 (0.57, 3.25)* | 3.98 (2.15, 5.81)* | 0.07 |

|

| |||

| Kidney disease-specific HRQOL | 2.41 (1.78, 3.04)* | 3.75 (2.89, 4.60)* | 0.01 |

| Domains: | |||

| Symptoms | 2.21 (1.55, 2.86)* | 3.27 (2.38, 4.17)* | 0.06 |

| Effects | 4.01 (2.99, 5.03)* | 7.10 (5.68, 8.51)* | 0.001 |

| Burden | 6.38 (4.88, 7.88)* | 7.94 (5.90, 9.98)* | 0.23 |

| Cognitive function | 1.28 (0.50, 2.07)* | 2.88 (1.80, 3.96)* | 0.019 |

| Social interaction | −0.57 (−1.47, 0.33) | 1.18 (−0.06, 2.43) | 0.025 |

| Sleep | 2.02 (0.81, 3.22)* | 3.28 (1.62, 4.95)* | 0.23 |

| Social support | 1.73 (0.55, 2.91)* | 2.53 (0.90, 4.18)* | 0.43 |

(Key: HRQOL= Health-Related Quality of Life). Separate longitudinal models of change in HRQOL by frailty status adjusted for age, sex, race, educational status, donor type and HRQOL at transplant. Interaction p value indicates whether rates of change in frail and nonfrail KT recipients are significantly different.

indicates statistical significant difference in rates of change of HRQOL. All measures of HRQOL made using the Kidney Disease Quality of Life instrument short form (KDQOL-SF) (35). Negative rates indicate worsening HRQOL.

Furthermore, frail recipients reported significantly greater rates of improvement in the constituent domain of general health (frail: 4.93 points/month, 95% CI: 3.51, 6.35; nonfrail: 2.87 points/month, 95% CI: 1.82, 3.92; p for interaction=0.02), the effects of ESRD on daily living (frail: 7.10 points/month, 95% CI: 5.68, 8.51; nonfrail: 4.01 points/month, 95% CI: 2.99, 5.03; p for interaction=0.001), and cognitive function (frail: 2.88 points/month, 95% CI: 1.80, 3.96; nonfrail: 1.28 points/month, 95% CI: 0.50, 2.07; p for interaction=0.02).

Transplant Factors and Rate of Change in post-KT HRQOL Adjusted for Recipient and Donor Factors

Among LDKT recipients there was a significantly greater rate of improvement over 3-months in post-KT physical HRQOL (LDKT: 1.57 points/month, 95% CI: 0.98, 2.17; DDKT: 0.18 points/month, 95% CI: −0.25, 0.62; p for interaction<0.001) and kidney disease-specific HRQOL (LDKT: 3.67 points/month, 95% CI: 3.03, 4.32; DDKT: 2.48 points/month, 95% CI: 1.84, 3.13; p for interaction=0.01) (Table 6).

Table 6.

Rates of change in Posttransplant Health-Related Quality of Life Within 3 Months by Transplant Factors.

| DDKT | LDKT | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Points/month (95% CI) | Points/month (95% CI) | Interaction p value | |

| Physical HRQOL | 0.18 (−0.25, 0.62) | 1.57 (0.98, 2.17)* | <0.001 |

| Mental HRQOL | 0.38 (−0.11, 0.87) | 0.72 (0.12, 1.33)* | 0.39 |

| Kidney disease-specific HRQOL | 2.48 (1.84, 3.13)* | 3.67 (3.03, 4.32)* | 0.01 |

|

| |||

| DGF | No DGF | ||

|

| |||

| Points/month (95% CI) | Points/month (95% CI) | Interaction p value | |

|

| |||

| Physical HRQOL | 0.28 (−0.39, 0.96) | 0.85 (0.42, 1.28)* | 0.17 |

| Mental HRQOL | −0.13 (−0.78, 0.52) | 0.69 (0.23, 1.16)* | 0.04 |

| Kidney disease-specific HRQOL | 2.23 (1.16, 3.31)* | 3.18 (2.64, 3.82)* | 0.12 |

|

| |||

| High KDPI | Low KDPI | ||

|

| |||

| Points/month (95% CI) | Points/month (95% CI) | Interaction p value | |

|

| |||

| Physical HRQOL | 0.15 (−1.72, 2.02) | 0.31 (−0.13, 0.75) | 0.87 |

| Mental HRQOL | −0.69 (−2.29, 0.92) | 0.47 (−0.03, 0.98) | 0.18 |

| Kidney disease-specific HRQOL | 0.33 (−1.73, 2.39) | 2.65 (1.96, 3.33)* | 0.04 |

(Key: HRQOL= Health-Related Quality of Life, DDKT= Deceased Donor Kidney Transplantation, LDKT= Live Donor Kidney Transplantation, DGF= Delayed Graft Function, KDPI=Kidney Donor Profile Index). Separate longitudinal models of change in HRQOL by transplant factors adjusted for age, sex, race, educational status, donor type and HRQOL at transplant. Interaction p value indicates whether rates of change in living vs. deceased donor KT recipients (as well as DGF and KDPI) are significantly different.

indicates statistical significant difference in rates of change of HRQOL. All measures of HRQOL made using the Kidney Disease Quality of Life instrument short form (KDQOL-SF) (35). Negative rates indicate worsening HRQOL.

Discussion

In this longitudinal study of 443 KT recipients, we found that frail KT recipients had worse physical and kidney disease-specific HRQOL prior to KT, but they had a greater rate of improvement in the first 3 months post-KT compared with their nonfrail counterparts. Importantly, they also had substantial gains in general health (4.93 points per month) and the effects of ESRD on daily living (7.10 points per month) in the first 3 months post-KT. Finally, there were no differences in mental HRQOL at KT or changes in mental HRQOL by frailty status.

Previous studies suggest that KT recipients have better HRQOL and life participation than ESRD patients undergoing dialysis (41, 42), and that overall HRQOL improves for most recipients after KT (43). However, the impact of KT on mental HRQOL is small (8, 9). We have extended these findings on physical, mental, and kidney disease-specific HRQOL after KT and found that by 3 months post-KT frail KT recipients have a 4-point increase in physical HRQOL, and a 10-point increase in kidney disease specific HRQOL. These changes are substantial and meaningful given that a 2–3-point difference in SF-36 scores is clinically relevant for patients (44–46). Interestingly, the 3-month improvement in HRQOL occurs at the same time that frailty improves, on average, after KT (32). We also found that the impact of KT on mental HRQOL was minimal for both frail and nonfrail KT recipients; this is likely the case because the measure of mental HRQOL (MCS) emphasizes how a patient feels and reflect their emotional well-being which may require more than 3 months to improve.

Few studies have identified phenotypes of patients who do and do not experience an HRQOL benefit from KT. Sarcopenia and muscle weakness are associated with worse physical HRQOL after KT (43). Additionally, KT recipients with diabetes were found to have worse post-KT HRQOL (47). We have previously demonstrated that frail KT recipients are at high risk of adverse KT outcomes including delayed graft function, longer length of stay, early hospital readmission, immunosuppression intolerance, and mortality (17–20, 34). This work extends these previous findings on frailty among KT recipients to include a patient-centered outcome and demonstrates that frail recipients benefit from KT with respect to physical HRQOL. It is possible that while frail KT recipients experience the greatest decline in HRQOL while undergoing the stressor of dialysis (16) particularly those undergoing hemodialysis (48), the restoration of kidney function through KT greatly improves their HRQOL even if they experience proximal adverse outcomes like early hospital readmission or delayed graft function (49–51).

This study has several strengths and limitations. While HRQOL is often critiqued because it a subjective measure of the impact of a disease or treatment, this is a strength of our study because we captured the overall patient-centered impact of ESRD on physical, mental, and kidney-disease specific HRQOL. We could measure changes in HRQOL after KT while accounting for pre-KT HRQOL which has not been previously characterized in frail adults; the longitudinal nature of our study is a clear strength. Additionally, we have ascertained a prospective measurement of a validated, objective frailty instrument to capture decreased physiologic reserve (11). One of the main limitations of the study is that we have only a single validated instrument to measure HRQOL; however, the KDQOL is the most commonly used measure of HRQOL in this population and 1 of the only instruments that is specific to ESRD patients. Additionally, this study focused on HRQOL immediately following KT as this is a critical time of recovery and did not have long-term measures of HRQOL. However, this is a particularly important postoperative period with dynamic changes in HRQOL which are associated with subsequent morbidity and mortality (3, 6). Finally, we did not collect information on formal physical rehabilitation following KT discharge.

In this study of KT recipients of all ages, recipients who were frail prior to KT experienced a greater change in physical HRQOL and kidney-disease specific HRQOL than their nonfrail counterparts even though frail KT recipients had worse HRQOL prior to KT. Frail recipients who undergo KT experience better improvement in physical and kidney disease-specific HRQOL despite their increased vulnerability to stressors and impaired HRQOL pre-KT. Our findings highlight that even a high risk group like frail KT recipients experience the benefit of improved HRQOL with KT. These findings have important implications for KT candidates, especially those who are frail and unable to tolerate the stressor of dialysis; KT may improve physical and kidney-disease specific HRQOL.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the study participants for their contributions to this study.

Funding

This study was supported by NIH grant K24DK101828 (PI: Dorry Segev), and by NIH grant (PI: Dorry Segev). Mara McAdams-DeMarco was supported by the Johns Hopkins University Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG021334) and NIH grant K01AG043501. Rasheeda Hall was supported by the Duke Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center (P30AG028716), GEMSSTAR program R03AG050834], National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (UL1TR001117), the T. Franklin Williams Scholarship Award (Funding provided by Atlantic Philanthropies, Inc., the John A. Hartford Foundation, the Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine-Association of Specialty Professors, and the American Society of Nephrology Foundation). Christine Haugen was supported by NIH grant F32AG053025.

Abbreviations

- ESRD

end-stage renal disease

- KT

kidney transplant

- HRQOL

health-related quality of life

- KDQOL-SF

kidney disease quality of life instrument short form

- US

United States

Footnotes

Authorship

Mara A. McAdams-DeMarco: Research design, data analysis, writing of the paper and review of the paper

Israel O. Olorundare: Data analysis, writing of the paper and review of the paper

Hao Ying: Performance of the research, data analysis, writing of the paper and review of the paper

Fatima Warsame: Performance of the research, writing of the paper and review of the paper

Christine E. Haugen: Performance of the research, writing of the paper and review of the paper

Rasheeda Hall: Writing of the paper and review of the paper

Jacqueline M. Garonzik-Wang: Performance of the research, writing of the paper and review of the paper

Niraj M. Desai: Performance of the research, writing of the paper and review of the paper

Jeremy D. Walston: Writing of the paper and review of the paper

Silas P. Norman: Performance of the research, writing of the paper and review of the paper

Dorry L. Segev: Research design, writing of the paper and review of the paper

Disclosure

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Croog SH, Levine S. Quality of life and health care interventions. In: Freeman HE, Levine S, editors. Handbook of Medical Sociology. 4th. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall College Div; 1989. p. 508. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guyatt GH, Bombardier C, Tugwell PX. Measuring disease-specific quality of life in clinical trials. CMAJ. 1986;134(8):889–895. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Griva K, Davenport A, Newman SP. Health-related quality of life and long-term survival and graft failure in kidney transplantation: a 12-year follow-up study. Transplantation. 2013;95(5):740–9. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31827d9772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mapes DL, Lopes AA, Satayathum S, et al. Health-related quality of life as a predictor of mortality and hospitalization: the Dialysis Outcomes and Practice Patterns Study (DOPPS) Kidney Int. 2003;64(1):339–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00072.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Molnar-Varga M, Molnar MZ, Szeifert L, et al. Health-related quality of life and clinical outcomes in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(3):444–52. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prihodova L, Nagyova I, Rosenberger J, et al. Health-related quality of life 3 months after kidney transplantation as a predictor of survival over 10 years: a longitudinal study. Transplantation. 2014;97(11):1139–45. doi: 10.1097/01.TP.0000441092.24593.1e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kugler C, Gottlieb J, Warnecke G, et al. Health-related quality of life after solid organ transplantation: a prospective, multiorgan cohort study. Transplantation. 2013;96(3):316–23. doi: 10.1097/TP.0b013e31829853eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ortega T, Deulofeu R, Salamero P, et al. Health-related quality of life before and after a solid organ transplantation (kidney, liver, and lung) of four Catalonia hospitals. Transplantation. 41(6):2265–7. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2009.06.175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pinson CW, Feurer ID, Payne JL, Wise PE, Shockley S, Speroff T. Health-related quality of life after different types of solid organ transplantation. Ann Surg. 2000;232(4):597–607. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200010000-00015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ortiz F, Aronen P, Koskinen PK, et al. Health-related quality of life after kidney transplantation: who benefits the most? Transpl Int. 2014;27(11):1143–51. doi: 10.1111/tri.12394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M146–56. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, et al. Frailty as a novel predictor of mortality and hospitalization in individuals of all ages undergoing hemodialysis. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2013;61(6):896–901. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Suresh S, Law A, et al. Frailty and falls among adult patients undergoing chronic hemodialysis: a prospective cohort study. BMC Nephrol. 2013;14:224. doi: 10.1186/1471-2369-14-224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Tan J, Salter ML, et al. Frailty and cognitive function in incident hemodialysis patients. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(12):2181–9. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01960215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nastasi AJ, McAdams-DeMarco MA, Schrack J, et al. Pre-kidney transplant lower extremity impairment and post-transplant mortality. Am J Transplant. 2017 Jul 15; doi: 10.1111/ajt.14430. published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McAdams-DeMarco M, Ying H, Olorundare I, et al. Frailty and health-related quality of life in end stage renal disease patients of all ages. J Frailty Aging. 2016;5(3):174–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garonzik-Wang JM, Govindan P, Grinnan JW, et al. Frailty and delayed graft function in kidney transplant recipients. Arch Surg. 2012;147(2):190–3. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2011.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McAdams-DeMarco MA, King EA, Luo X, et al. Frailty, length of stay, and mortality in kidney transplant recipients: a national registry and prospective cohort study. Ann Surg. 2016 Sep 21; doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002025. published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Salter ML, et al. Frailty and early hospital readmission after kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2013;13(8):2091–2095. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Law A, Tan J, et al. Frailty, mycophenolate reduction, and graft loss in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2015;99(4):805–810. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hemmelgarn BR, Manns BJ, Quan H, Ghali WA. Adapting the Charlson Comorbidity Index for use in patients with ESRD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2003;42(1):125–32. doi: 10.1016/s0272-6386(03)00415-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bandeen-Roche K, Xue Q-L, Ferrucci L, et al. Phenotype of frailty: characterization in the women’s health and aging studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2006;61(3):262–6. doi: 10.1093/gerona/61.3.262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Barzilay JI, Blaum C, Moore T, et al. Insulin resistance and inflammation as precursors of frailty: the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(7):635–41. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.7.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cappola AR, Xue Q-L, Fried LP. Multiple hormonal deficiencies in anabolic hormones are found in frail older women: the Women’s Health and Aging studies. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(2):243–8. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chang SS, Weiss CO, Xue Q-L, Fried LP. Patterns of comorbid inflammatory diseases in frail older women: the Women’s Health and Aging Studies I and II. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;65(4):407–13. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glp181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang SS, Weiss CO, Xue Q-L, Fried LP. Association between inflammatory-related disease burden and frailty: results from the Women’s Health and Aging Studies (WHAS) I and II. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(1):9–15. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2011.05.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Leng SX, Hung W, Cappola AR, Yu Q, Xue Q-L, Fried LP. White blood cell counts, insulinlike growth factor-1 levels, and frailty in community-dwelling older women. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2009;64(4):499–502. doi: 10.1093/gerona/gln047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Leng SX, Xue QL, Tian J, Walston JD, Fried LP. Inflammation and frailty in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007;55(6):864–71. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01186.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Newman AB, Gottdiener JS, McBurnie MA, et al. Associations of subclinical cardiovascular disease with frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2001;56(3):M158–66. doi: 10.1093/gerona/56.3.m158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Walston J, McBurnie MA, Newman A, et al. Frailty and activation of the inflammation and coagulation systems with and without clinical comorbidities: results from the Cardiovascular Health Study. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162(20):2333–41. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.20.2333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xue Q-L, Bandeen-Roche K, Varadhan R, Zhou J, Fried LP. Initial manifestations of frailty criteria and the development of frailty phenotype in the Women’s Health and Aging Study II. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008;63(9):984–90. doi: 10.1093/gerona/63.9.984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Isaacs K, Darko L, et al. Changes in frailty after kidney transplantation. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63(10):2152–7. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McAdams-DeMarco MA, Ying H, Olorundare I, et al. Individual frailty components and mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Transplantation. 2017;101(9):2126–2132. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McAdams-DeMarco M, Law A, King E, et al. Frailty and mortality in kidney transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2015;15(1):149–2132. doi: 10.1111/ajt.12992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hays RD, Amin N, Leplege A, et al. Kidney Disease Quality of Life Short Form (KDQOL-SFtm), Version 1.2: A manual for use and scoring (French questionnaire, France) Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hays RD, Kallich JD, Mapes DL, Coons SJ, Carter WB. Development of the kidney disease quality of life (KDQOL™) instrument. Qual Life Res. 1994;3(5):329–38. doi: 10.1007/BF00451725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Barotfi S, Molnar MZ, Almasi C, et al. Validation of the Kidney Disease Quality of Life-Short Form questionnaire in kidney transplant patients. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60(5):495–504. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2005.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ware JE, Keller SD, Kosinski M. SF-36 physical and mental health summary scales: a user’s manual. Boston, MA: Health Assessment Lab; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Saban KL, Bryant FB, Reda DJ, Stroupe KT, Hynes DM. Measurement invariance of the kidney disease and quality of life instrument (KDQOL-SF) across veterans and non-veterans. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2010;8:120. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-8-120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Saban KL, Stroupe KT, Bryant FB, Reda DJ, Browning MM, Hynes DM. Comparison of health-related quality of life measures for chronic renal failure: quality of well-being scale, short-form-6D, and the kidney disease quality of life instrument. Quality of Life Research. 2008;17(8):1103–15. doi: 10.1007/s11136-008-9387-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Czyzewski L, Sanko-Resmer J, Wyzgal J, Kurowski A. Assessment of health-related quality of life of patients after kidney transplantation in comparison with hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis. Ann Transplant. 2014;19:576–85. doi: 10.12659/AOT.891265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Purnell TS, Auguste P, Crews DC, et al. Comparison of life participation activities among adults treated by hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, and kidney transplantation: a systematic review. Am J Kidney Dis. 2013;62(5):953–73. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Villeneuve C, Laroche M-L, Essig M, et al. Evolution and determinants of health-related quality-of-life in kidney transplant patients over the first 3 years after transplantation. Transplantation. 2016;100(3):640–7. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jaeschke R, Singer J, Guyatt GH. Measurement of health status: ascertaining the minimal clinically important difference. Control Clin Trials. 1989;10(4):407–15. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(89)90005-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wyrwich KW, Bullinger M, Aaronson N, Hays RD, Patrick DL, Symonds T. Estimating clinically significant differences in quality of life outcomes. Qual Life Res. 2005;14(2):285–95. doi: 10.1007/s11136-004-0705-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wyrwich KW, Wolinsky FD. Identifying meaningful intra-individual change standards for health-related quality of life measures. J Eval Clin Pract. 2000;6(1):39–49. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2753.2000.00238.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Dukes JL, Seelam S, Lentine KL, Schnitzler MA, Neri L. Health-related quality of life in kidney transplant patients with diabetes. Clin Transplant. 2013;27(5):E554–62. doi: 10.1111/ctr.12198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wu AW, Fink NE, Marsh-Manzi JV, et al. Changes in quality of life during hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis treatment: generic and disease specific measures. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2004;15(3):743–53. doi: 10.1097/01.asn.0000113315.81448.ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lubetzky M, Yaffe H, Chen C, Ali H, Kayler LK. Early readmission after kidney transplantation: examination of discharge-level factors. Transplantation. 2016;100(5):1079–85. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000001089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li AH, Lam NN, Naylor KL, Garg AX, Knoll GA, Kim SJ. Early hospital readmissions after transplantation: burden, causes, and consequences. Transplantation. 2016;100(4):713–8. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Taber DJ, Palanisamy AP, Srinivas TR, et al. Inclusion of dynamic clinical data improves the predictive performance of a 30-day readmission risk model in kidney transplantation. Transplantation. 2015;99(2):324–30. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]