Abstract

There is broad agreement that neighborhood contexts are important for adolescent development, but there is less consensus about their association with adolescent smoking and alcohol use. Few studies have examined associations between neighborhood socioeconomic contexts and smoking and alcohol use while also accounting for differences in family and peer risk factors for substance use. Data drawn from the Seattle Social Development Project (N=808), a gender-balanced (female=49%), multiethnic, theory-driven longitudinal study originating in Seattle, WA, were used to estimate trajectories of smoking and alcohol use from 5th to 9th grade. Time-varying measures of neighborhood socioeconomic, family, and peer factors were associated with smoking and alcohol use at each wave after accounting for average growth in smoking and alcohol use over time and demographic differences. Results indicated that living in more socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods, lower family income, low family general functioning, more permissive family smoking environments, and affiliation with deviant peers were independently associated with increased smoking. Low family functioning, more permissive family alcohol use environments, and deviant peers were independently associated with increased alcohol use. The effect of neighborhood disadvantage on smoking was mediated by family income and deviant peers while the effect of neighborhood disadvantage on alcohol use was mediated by deviant peers alone. Family functioning and family substance use did not mediate associations between neighborhood disadvantage and smoking or alcohol use. The results highlight the importance of neighborhood, family, and peer factors in early adolescent smoking and alcohol use. Future studies should examine the unique association of neighborhood disadvantage with adolescent smoking net of family-level socioeconomics, family functioning, and peer affiliations. Better understanding of the role of contextual factors in early adolescent smoking and alcohol use can help bolster efforts to prevent both short and long harms from substance use.

Keywords: neighborhood disadvantage, early onset smoking, early onset alcohol use, adolescent development, latent growth curve

Introduction

There is now a consensus that preventing early initiation of smoking and alcohol use is a key strategy in improving both short and long term adolescent health (Catalano et al., 2012; Currie et al., 2009; Office of Surgeon General, 2016; Viner et al., 2012). Smoking initiation in the early teenage years has consistently been associated with increased risk of developing nicotine dependence and decreased likelihood of smoking cessation in adulthood (Breslau & Peterson, 1996; Grant, 1998; Kendler, Myers, Damaj, & Chen, 2013). Systematic reviews also suggest that early smoking may inhibit normative cognitive development and enhance susceptibility to nicotine and other drug addiction (Lydon, Wilson, Child, & Geier, 2014). As such, early adolescent smoking contributes to the substantial societal costs attributable to smoking-related disease, disability, and mortality across the life course (Centers for Disease Control Prevention, 2008). Similar to smoking, early initiation of alcohol use has repeatedly been identified as a risk factor for later alcohol misuse, abuse, and dependence (Grant & Dawson, 1997; Grant, Stinson, & Harford, 2001; Guttmannova et al., 2011; Hawkins et al., 1997). Further, adolescents who begin using alcohol at earlier ages are at increasing risk for unintentional physical injury to themselves, unintentional injury to others, and regularly driving under the influence of alcohol (Hingson & Zha, 2009). Systematic reviews suggest that early adolescent alcohol use can lead to adverse changes in brain structures that regulate risk and reward systems and, in turn, increase risk for developing alcohol addiction (Ewing, Sakhardande, & Blakemore, 2014; Welch, Carson, & Lawrie, 2013). Early initiation of alcohol use, therefore, plays an important role in the considerable societal costs emanating from problem drinking (Rehm et al., 2014) and the alcohol-related burden of injury and disease across the life course (Sacks, Gonzales, Bouchery, Tomedi, & Brewer, 2015). While many youth experiment with smoking and alcohol, delayed onset and restricted use among those who do use may help mitigate the negative consequences of adolescent substance use (Spoth, Reyes, Redmond, & Shin, 1999). Given the current breadth and depth of findings highlighting the preventable harms associated with adolescent smoking and alcohol use (Catalano et al., 2012), it is essential to continue refining our understanding of risk factors associated with the dynamics of early onset of smoking and alcohol use.

Neighborhood Socioeconomics and Adolescent Substance Use

There is broad agreement that neighborhood socioeconomic factors represent an important component of the social determinants of health and well-being (Diez Roux & Mair, 2010). More specifically, researchers have sought to understand the extent to which exposure to impoverished or unstable neighborhoods may undermine healthy adolescent development (Elliott et al., 1996; Jencks & Mayer, 1990; Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Wilson, 1987). These studies have largely drawn from socioecological theories of human development (Bronfenbrenner, 1977) which posit that adolescent behaviors and developmental outcomes are best understood as embedded within social contexts such as neighborhoods, peer groups, and families. Neighborhoods characterized by high poverty, low educational attainment, and lack of stability among residents are theorized to contain low levels of informal social control important for inhibiting deviant behavior among youth, a shortage of collective social support mechanisms for parents and children, and a higher concentration of deviant peer groups (Elliott et al., 1996; Jencks & Mayer, 1990; Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002). While research has shown that children growing up in disadvantaged neighborhoods are at increased risk of high school dropout (Wodtke, Harding, & Elwert, 2011) and mental health problems (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000), studies explicitly testing the association of neighborhood disadvantage and adolescent substance use have not produced consistent results (Jackson, Denny, & Ameratunga, 2014; Karriker-Jaffe, 2011; Mathur, Erickson, Stigler, Forster, & Finnegan Jr, 2013). Depending on study design, sociodemographic features of the study sample, and the range of control variables considered, living in a disadvantaged neighborhood has been connected with both increased and decreased alcohol use and smoking among adolescents (Jackson et al., 2014; Karriker-Jaffe, 2011; Mathur et al., 2013).

Neighborhood-focused scholars have offered two categories of potential explanations for the above inconsistencies in findings across studies. First, measures of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage typically include area-level estimates of median household income, percentage of residents dropping out of high school, and percentage of single-parent households (Herrenkohl, Hawkins, Abbott, & Guo, 2002; Sampson et al., 2002). Without these same factors measured at the family-level, analyses run the risk of conflating neighborhood and family socioeconomics in their relationship to adolescent development (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Thus, it is important that measures of family-level socioeconomics such as income, parental education, and family structure be included in statistical models estimating the effect of neighborhood socioeconomics on adolescent outcomes (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000; Wodtke et al., 2011). A second explanation for inconsistent findings across studies is the span of time adolescents have resided in a specific neighborhood. Scholars have contended that the duration of exposure is a key, but often unmeasured, factor in studies assessing the impact of neighborhood contexts on adolescents (Jackson & Mare, 2007; Wodtke et al., 2011). As such, adolescents exposed to socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods for only brief periods of time may display different patterns of association between neighborhoods and substance use when compared to those with sustained exposure to disadvantaged neighborhoods (Wodtke et al., 2011). Thus, it is important to account for length of exposure to neighborhood disadvantage in models seeking to understand the impact of neighborhood disadvantage on substance use.

Family and Peer Risk Factors for Substance Use

Studies investigating the role of family-level sociodemographic factors in predicting adolescent smoking and alcohol use have also not produced consistent results across studies (Blum et al., 2000; Devenish, Hooley, & Mellor, 2017; Hanson & Chen, 2007; Patrick, Wightman, Schoeni, & Schulenberg, 2012). While epidemiological surveillance and systematic reviews have reported higher rates of smoking among adults of lower socioeconomic status (SES), it remains less clear if this relationship extends to adolescents (Galea, Nandi, & Vlahov, 2004; Hiscock, Bauld, Amos, Fidler, & Munafò, 2012). Research examining relationships between family SES and adolescent alcohol use have produced varied results with a range of studies finding positive, negative, and null effects of lower family SES on adolescent alcohol use (Hanson & Chen, 2007). It is important to consider that, similar to challenges faced by neighborhood-based studies, adolescents may be exposed to markedly different levels of family SES across development as parents potentially gain promotions, obtain new jobs, or experience bouts of unemployment (Wodtke, Elwert, & Harding, 2016). More consistent findings have been noted for differences in adolescent smoking and alcohol use by family structure and by race or ethnicity. Results from studies employing nationally representative samples have found that African American youth engage is less smoking and alcohol use compared to Whites after controlling for family income, family structure, and gender (Blum et al., 2000; Hoffmann & Johnson, 1998). These same studies have also shown that adolescents in single-parent households are at increased risk for substance use after controlling for other sociodemographic factors. Research employing multi-ethnic, longitudinal samples have similarly observed less smoking and alcohol use among Asian American and African American youth when compared to European Americans after controlling for differences in family SES, family structure, and gender (Catalano et al., 1992; Hill, Hawkins, Catalano, Abbott, & Guo, 2005; Kosterman, Hawkins, Guo, Catalano, & Abbott, 2000).

Socioecological models of adolescent behavior suggest that other family factors and social contexts are important potential influences that may contribute to substance use beyond neighborhood factors (Cambron, Catalano, & Hawkins, in press; Catalano & Hawkins, 1996). Prevention scientists and substance use researchers have highlighted the clear role that poor functioning families and deviant peer groups play in escalating adolescent substance use (Galea et al., 2004; Hawkins, Catalano, & Miller, 1992a). A meta-analysis of 77 studies identified multiple features of family relationship quality including positive parental monitoring, shared activities between parents and children, parental warmth, quality of communication, parent-child bonding, and use of positive discipline strategies as important factors in delaying early adolescent initiation of alcohol use (Ryan, Jorm, & Lubman, 2010). Similar measures of family relationship quality have been linked with adolescent smoking by multiple studies (Darling & Cumsille, 2003; Hill et al., 2005; Skinner, Haggerty, & Catalano, 2009). Parent and sibling substance using behaviors as well as more permissive family norms regarding substance use have also shown strong associations with increased early adolescent smoking and alcohol use across numerous studies (Darling & Cumsille, 2003; Hawkins et al., 1992a; Hill et al., 2005; Kosterman et al., 2000; Tobler, Komro, & Maldonado-Molina, 2009).

More recent investigations have suggested the importance of considering the unique role of substance use specific features of family relationships in addition to general features of family environments (Bailey et al., 2014; Bailey, Hill, Meacham, Young, & Hawkins, 2011; Epstein, Hill, Bailey, & Hawkins, 2013; Hill et al., 2005; Tobler et al., 2009). Findings from these studies have shown that, net of adolescent general family functioning, more permissive adolescent family smoking environments uniquely predict a higher likelihood of initiation of daily smoking during adolescence (Hill et al., 2005) and nicotine dependence among young adults (Bailey et al., 2014; Bailey et al., 2011). Studies have also indicated that more permissive adolescent family smoking and alcohol environments predicted higher levels of engagement in multiple problem behaviors including polysubstance use, antisocial behavior, and risky sex among young adults net of the impact of adolescent general family functioning (Bailey et al., 2014; Bailey et al., 2011). Tobler and colleagues (2009) showed a unique connection between more permissive family alcohol environments and youth alcohol use net of family functioning, previous alcohol use, and other risk factors for alcohol use. In this same study, more permissive family alcohol environments partially mediated an inverse association between stronger neighborhood social structure and youth alcohol use.

Numerous researchers have identified substantially increased risk of smoking and alcohol use among adolescents affiliated with deviant or substance using peers (Harrop & Catalano, 2016; Hawkins et al., 1992a). Some studies have suggested that lack of appropriate parental monitoring and poor parenting practices may set the stage for increased affiliation with deviant peers (Oxford, Harachi, Catalano, & Abbott, 2001; Skinner et al., 2009). Researchers have also suggested that socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods may be important for adolescent smoking and alcohol use in the extent to which these environments degrade positive family functioning (Byrnes & Miller, 2012; Roosa, Jones, Tein, & Cree, 2003) or facilitate deviant peer group formation (Brody et al., 2001; Chuang, Ennett, Bauman, & Foshee, 2005; Elliott et al., 2006; Ingoldsby et al., 2006). Chuang and colleagues (2005) noted that stronger parental monitoring in low SES neighborhoods reduced youth smoking and alcohol use even after accounting for family bonding, family substance use, and peer substance use. This same study showed greater parental alcohol use in higher SES neighborhoods which was, in turn, associated with increased youth alcohol use suggesting that more permissive family alcohol environments may be relevant mechanisms in both low and high SES neighborhoods.

Current Study

Given that many adolescents experiment with substance use, it is important to understand factors related to both early initiation and escalation of use that lead to negative health consequences. To date, only two studies have sought to examine associations between neighborhood socioeconomics and trajectories of adolescent smoking (Mathur et al., 2013) or alcohol use (Trim & Chassin, 2008). Neither study, however, considered neighborhood socioeconomic factors or other important contexts for smoking and alcohol use over time. Mathur and colleagues (2013), using latent growth curve modeling to estimate smoking trajectories for adolescents aged 12 to 18, found no direct effect of neighborhood socioeconomics on either smoking at age 12 or growth in smoking over time after controlling family SES, gender, and ethnicity. However, lower family SES predicted increased smoking at age 12 and over time. Trim and Chassin (2008) also used latent growth curve modeling to estimate trajectories of alcohol use among adolescents aged 10 to 15 and compared trajectories for adolescents with an alcoholic parent to adolescents without. Recognizing the temporal importance of neighborhood socioeconomic factors, Trim and Chassin restricted their analysis to families that did not move to neighborhoods with different socioeconomic profiles during the study period. Results indicated that among adolescent without an alcoholic parent, living in a more socioeconomically advantaged neighborhood was predictive of increased alcohol use over time after controlling for age, ethnicity, and parent education. Estimating the same model for adolescents with an alcoholic parent produced the opposite result indicating that living in a more disadvantaged neighborhood was predictive of increased alcohol use over time. No differences by ethnicity or parent education were noted.

In the present study, we incorporated family and peer risk factors for substance use established by prevention science frameworks (Harrop & Catalano, 2016; Hawkins et al., 1992a) as well as conceptual guidance from neighborhood-focused researchers (Jackson & Mare, 2007; Wodtke et al., 2011) to examine trajectories of adolescent smoking and alcohol use. We employed time-varying measures of neighborhood socioeconomics, family SES, low family functioning, family substance using environments, and deviant peer affiliations. Building upon the above described studies, we hypothesized that lower family functioning, more permissive family smoking environments, and affiliations with deviant peers would be related to higher levels of smoking. We also hypothesized that lower family functioning, more permissive family alcohol environments, and affiliation with deviant peers would be related to higher levels of alcohol use. Associations of neighborhood disadvantage, residential stability, and family SES with smoking or alcohol use among adolescents remains an open and important question to be examined here. Given findings from previous studies, we also expected that more proximal risk factors of low family functioning, permissive family substance use environments, and deviant peers would attenuate any observed relationships between neighborhood factors and youth smoking or alcohol use.

Methods

Sample

Data were drawn from the Seattle Social Development Project (SSDP), a longitudinal, theory-driven study originating in 18 Seattle elementary schools over-representing high crime neighborhoods. SSDP conducted paper and pencil interviews in 1985 with 808 students in the 5th grade when most participants were 10 years old (M = 10.3, SD = .52). The 808 respondents accounted for 77% of 1,053 5th grade students initially invited to participate in the study. Retention rates for the participating sample across the four waves of data collection for the analysis sample were 69%, 81%, and 97% in grades 6, 7, and 9 respectively. At each wave, one parent or caregiver conducted a paper and pencil interview separately from the student. Parental or caregiver participation rates were 71%, 75%, 75%, and 89% of the full youth sample at grades 5, 6, 7, and 9 respectively and approximately 85% of parental responses were provide by the student’s mother. Of the longitudinal sample, 49% were female, 46% were European American, 24% were African American, 21% were Asian American and 9% were Native American.

Measures

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for all measures by grade.

Table 1.

Sample descriptive statistics

| Variable | Min | Max | Grade 5 | Grade 6 | Grade 7 | Grade 9 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | M | SD | |||

| Past Month Smoking | 0 | 3 | .08 | .37 | .12 | .41 | .16 | .51 | .35 | .85 |

| none | 94.6% | 92.7% | 90.4% | 82.5% | ||||||

| less than 1 cigarette / day | 3.4% | 5.1% | 6.4% | 7.1% | ||||||

| 1 to 5 cigarettes / day | 2.0% | 2.3% | 2.4% | 5.7% | ||||||

| 10+ cigarettes / day | 0% | 0% | 0.7% | 4.7% | ||||||

| Past Month Alcohol Use | 0 | 3 | .23 | .52 | .24 | .54 | .27 | .59 | .41 | .79 |

| none | 82.0% | 84.7% | 81.0% | 72.4% | ||||||

| 1 or 2 times | 13.4% | 10.6% | 15.3% | 18.4% | ||||||

| 3 to 5 times | 4.6% | 4.7% | 2.3% | 6.0% | ||||||

| 6+ times | 0% | 0% | 1.5% | 3.2% | ||||||

| Neighborhood Disadvantage | −1.40 | 5.67 | .00 | 1.00 | .00 | 1.00 | .00 | 1.00 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Residential Stability | −5.11 | 2.15 | .00 | 1.00 | .00 | 1.00 | .00 | 1.00 | .00 | 1.00 |

| Family Income | 1 | 7 | 4.38 | 1.92 | 4.53 | 1.93 | 4.61 | 1.96 | 4.99 | 1.85 |

| Low Family Functioning | 1 | 4 | 2.52 | .40 | 2.46 | .39 | 2.55 | .35 | 2.41 | .41 |

| Family Smoking Environment | 0 | 5 | 1.26 | .87 | 1.60 | .75 | 1.48 | .67 | 1.45 | .68 |

| Family Alcohol Use Environment | 0 | 4 | 1.58 | .69 | 1.55 | .69 | 1.65 | .67 | 1.41 | .64 |

| Deviant Peers | 1 | 2 | 1.13 | .22 | 1.18 | .27 | 1.22 | .27 | 1.31 | .28 |

| Female | 0 | 1 | 49% | - | - | - | ||||

| African American | 0 | 1 | 26% | - | - | - | ||||

| Asian American | 0 | 1 | 22% | - | - | - | ||||

| Native American | 0 | 1 | 5% | - | - | - | ||||

| European American | 0 | 1 | 47% | - | - | - | ||||

| Two Parent Household | 0 | 1 | 69% | - | - | - | ||||

| Parent College Education | 0 | 1 | 56% | - | - | - | ||||

Notes. M = mean, SD = standard deviation.

Past month smoking and alcohol use

Participants responded to a single question for cigarette smoking at each grade and a single question for alcohol at each grade indicating the number of times they used each substance in the past month. A four category ordinal variable for past month smoking was created at each grade and coded as 0 = no past month use, 1 = less than one cigarette per day, 2 = 1 to 5 cigarettes per day, 3 = 10 or more cigarettes per day. A four category ordinal variable for past month alcohol use was created at each wave and coded 0 = no past month use, 1 = drank alcohol 1 or 2 times, 2 = drank alcohol 3 to 5 times, 3 = drank alcohol 6 or more times.

Neighborhood disadvantage and residential stability

Two factor scores from a principal components analysis summarizing 10 block group-level variables from the 1990 census were used to measure neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and residential stability. For further details and discussion on the development of this measure with the SSDP sample, see Herrenkohl and colleagues (2002). Previous research has indicated that census block groups containing roughly 2,000 to 3,000 residents most closely reflect adolescent perceptions of their neighborhood (Elliott et al., 2006). Participant home address data that could be geocoded and matched with census block groups included 792, 732, 724, and 766 addresses for grades 5, 6, 7, and 9 respectively. The average number of students per block group ranged from 1.8 to 2.8 across grades. Table 2 reports census items used, the results of the principal components analysis, and descriptive statistics for census variables. Higher scores on the neighborhood disadvantage factors indicate neighborhoods with lower socioeconomic resources and higher scores on the residential stability factor indicate more stable resident populations in the neighborhood.

Table 2.

Principal components analysis for census-based measures

| Variable | Neighborhood Disadvantage |

Residential Stability |

M | SD | Min | Max |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Percent of youth (ages 10–17) | .95 | .32 | 8.98 | 3.61 | .42 | 21.39 |

| Percent single-parent, female-headed households | .94 | −.01 | 15.22 | 10.58 | 1.62 | 60.12 |

| Percent of individuals receiving public assistance income | .84 | −.20 | 10.72 | 12.04 | .00 | 64.41 |

| Percent of adults without high school diploma | .84 | −.03 | 20.49 | 12.19 | .00 | 61.98 |

| Number of racial groups with 10% or more representation | .83 | .24 | 2.03 | .90 | 1.00 | 4.00 |

| Percent of families in poverty | .80 | −.24 | 11.97 | 15.85 | .00 | 86.81 |

| Percent of females unemployed | .73 | −.10 | 6.28 | 7.61 | .00 | 52.86 |

| Percent of males unemployed | .69 | −.14 | 7.37 | 7.44 | .00 | 56.14 |

| Percent of individuals living in same residence for 5+ years | .20 | .96 | 49.16 | 13.44 | .00 | 80.40 |

| Percent of owner-occupied homes | −.24 | .83 | 57.64 | 24.80 | .00 | 100.00 |

| Eigenvalue | 5.64 | 1.92 | ||||

| Percent of variance | .56 | .19 |

Notes. N = 792, M = mean, SD = standard deviation; results shown are for grade 5 and closely align with results for grades 6, 7, and 9.

Time-fixed sociodemographic factors

Gender was coded as female = 1 and male = 0. Dummy variables for ethnicity were coded such that the three ethnic groups were compared to European Americans. Two parent household was measured by a series of questions indicating family structure and was coded as 1 for two acting parents present and 0 for two acting parents not present. Parent college education was indicated by the maximum of educational attainment of the mother and father and was coded as 1 for at least one parent completing a 4-year college degree and 0 for neither parent completing a college degree. Family structure and education were reported by parents of study participants and measured at grade 5.

Time-varying general family factors

Family income was reported by parents and measured at each grade by a seven category question with response options ranging from less than $5,000 to greater than $40,000 annual income. Low family functioning was indicated by the mean of 21 questions about family management, involvement, and bonding. Family management questions asked about parental monitoring, communication practices, family rules, and conflict resolution strategies. Family involvement questions recorded the child’s level of involvement with their parents in the past week in household chores, recreational activities, family meals, or conversations about school. Family bonding questions asked if the participant wanted to be like their mother or father and how often the participants shared their thoughts and feelings with parents and siblings. All items were coded such that higher scores indicated lower family functioning (internal consistency = .79 to .85 across grades).

Time-varying family substance use

An index of family smoking environment was indicated by the mean of three questions. Parents reported how they perceived the risk of harm from smoking with responses from no risk to very great risk. Parents also reported their hypothetical response to their child smoking with responses ranging from “okay for the child to use if he or she wants” to “I would absolutely forbid my child to use.” All items were coded such that higher scores indicated more permissive smoking norms. Participants reported if he or she had any siblings who smoked cigarettes with responses coded as 1 = smoking sibling(s) and 0 = no smoking siblings. Higher scores on the index indicated more exposure to family smoking environments. An index of family alcohol environment was indicated by the mean of five questions regarding parent alcohol use and alcohol norms. Parents reported how often they drank alcohol with response options ranging from never to 3 or more drinks a day. Parents reported their perceived risk of harm from occasional and daily alcohol use with response options ranging from no risk to very great risk. Parents also reported their hypothetical parental response to their child drinking alcohol with responses ranging from “okay for the child to use if he or she wants” to “I would absolutely forbid my child to use.” All items were coded such that higher scores on the index indicated more exposure to family alcohol use environments.

Time-varying deviant peers

A scale of associations with deviant peers was constructed from the mean of six questions regarding the three best friends of the participant. Items asked if the participant’s three best friends did things to get in trouble with their teachers or tried alcohol without the knowledge of their parents with response options of yes or no. All items were coded to indicate more deviant behavior (internal consistency = .62 to .72 across grades).

Analytic Strategy

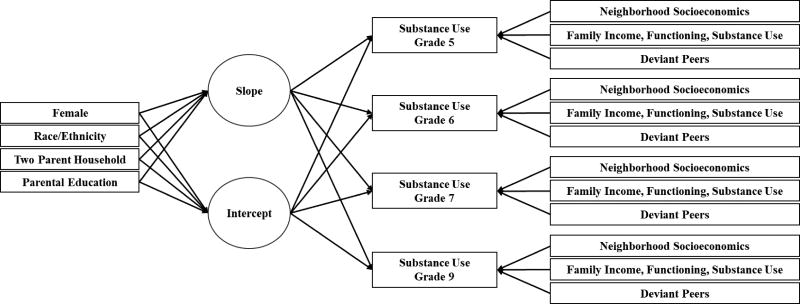

Longitudinal latent growth modeling is regularly employed to examine changes in substance use over time and offers the flexibility to estimate individual differences in initial levels of substance use and rates of change over time as well as deviation from average levels of use at each time point (Curran & Hussong, 2003). Deviation from average levels of substance use can be examined by simultaneously estimating a growth curve and regressing the indicators of the growth curve parameters (i.e., outcomes at each time point) on the time-varying predictors (Hussong, Curran, Moffitt, Caspi, & Carrig, 2004). Figure 1 provides a conceptual diagram of this strategy employing both time-fixed and time-varying covariates. Identical analytic strategies were employed for past month smoking and alcohol use models. First, an unconditional growth model estimated the trajectory of past month substance use from grades 5 to 9. Next, Model 1 examined the impact of time-fixed sociodemographic predictors on the latent intercept and latent slope and used time-varying measures of neighborhood disadvantage and residential stability to predict the ordinal indicators of substance use. Model 2 included time-varying measures of family income, low general family functioning, family substance use environments, and deviant peers also predicting ordinal indicators of substance use. Associations of each time-varying measure with the substance use measures were constrained to be equal over time in both Model 1 and 2. This strategy improved model fit and facilitated ease of interpretation. Model fit was compared across models using sample-size adjusted Bayesian Information Criteria (BIC) and a reduction of five or more in BIC was considered an improvement in model fit (Singer & Willett, 2003). Missing data were handled via the multiple imputation procedure in Mplus (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2010). Forty datasets were created and subsequently analyzed using latent growth modeling for categorical outcomes in Mplus 7.1 and mediation tests were conducted using the Model Constraint command (Muthén & Muthén, 2006). All models employed the maximum likelihood estimator for robust standard errors (MLR) and are averaged across the 40 imputed datasets. Parameter estimates and model fit statistics from unconditional models, Model 1, and Model 2 for smoking and alcohol use are reported in Table 3.1 Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals for time-varying covariates from Model 2 predicting higher smoking and alcohol use are shown in Figure 2. Growth models for smoking and alcohol use testing for non-linear growth did not show improved fit or substantively alter the results presented in Table 3. Results of tests for indirect effects are reported in Table 4.

Figure 1.

Latent growth curves for past month smoking and alcohol use from grades 5 to 9. Separate models for smoking and alcohol use at each grade were regressed on time-varying measures of neighborhood, family, and peer factors controlling respectively for average growth in smoking and alcohol use from grades 5 to 9.

Table 3.

Results of latent growth curves for past month smoking and alcohol use

| Smoking b

|

Alcohol Use c

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | ||

| Time-varying Covariates | Est. (SE) | Est. (SE) | Est. (SE) | Est. (SE) | |

|

|

|

||||

| Neighborhood Disadvantage | .64 (.15) *** | .41 (.13) ** | .24 (.11) * | .12 (.10) | |

| Residential Stability | −.04 (.15) | −.05 (.13) | .08 (.09) | .08 (.09) | |

| Family Income | −.49 (.15) ** | −.15 (.10) | |||

| Low Family Functioning | .38 (.11) ** | .36 (.08) *** | |||

| Family Substance Use Environment a | .33 (.11) ** | .17 (.07) * | |||

| Deviant Peers | 1.05 (.11) *** | .82 (.07) *** | |||

| Time-fixed Covariates | |||||

| Female | Int. | −.18 (.35) | −.03 (.34) | −.72 (.24) ** | −.54 (.24) * |

| Slope | −.03 (.13) | −.04 (.12) | .13 (.09) | .12 (.08) | |

| African American | Int. | −.69 (.46) | −1.01 (.47) * | −.85 (.33) * | −.88 (.34) * |

| Slope | −.43 (.17) ** | −.30 (.16) | .05 (.12) | .10 (.11) | |

| Asian American | Int. | −2.08 (.63) ** | −1.73 (.63) ** | −2.24 (.41) *** | −1.96 (.41) *** |

| Slope | −.32 (.22) | −.20 (.22) | .26 (.13) * | .35 (.12) ** | |

| Native American | Int. | −.45 (.66) | −.80 (.69) | −.97 (.56) | −1.14 (.58) |

| Slope | .66 (.22) ** | .63 (.23) ** | .42 (.17) * | .41 (.18) * | |

| Two Parent Household | Int. | .33 (.49) | .72 (.49) | .46 (.31) | .61 (.31) |

| Slope | −.35 (.17) * | −.27 (.16) | −.28 (.11) ** | −.23 (.11) * | |

| Parent College Education | Int. | −.83 (.49) | −.35 (.49) | −.06 (.27) | .13 (.28) |

| Slope | −.11 (.19) | −.11 (.18) | −.08 (.10) | −.12 (.10) | |

| Intercept & Slope | |||||

| Int. | Int. | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) | .00 (.00) |

| Slope | .61 (.25) * | .70 (.24) ** | .14 (.17) | .20 (.16) | |

| Residual Variance | Int. | 4.82 (1.3) *** | 3.67 (1.1) *** | 3.81 (.75) *** | 3.56 (.74) *** |

| Slope | .66 (.20) ** | .50 (.17) ** | .35 (.10) *** | .27 (.08) *** | |

| Intercept & Slope Covariance | −.35 (.31) | −.55 (.33) * | −.57 (.20) ** | −.73 (.20) *** | |

| BIC d | 2187 (2203) | 2011 (2032) | 3504 (3518) | 3296 (3303) | |

Notes. N=808; Est. = unstandardized estimates; SE = standard error; Int = intercept; time-varying predictors were standardized prior to inclusion in the model and predicted smoking and alcohol use after controlling for the average intercept and growth for the sample; ethnicity variables are compared to European Americans.

= family smoking environment and family alcohol environment correspond to each outcome respectively.

= Results of unconditional smoking model with intercept set at 0, intercept variance (Est = 5.21, SE = 1.35), slope (Est = .11, SE = .12), slope variance (Est = .79, SE = .21), BIC (2233).

= Results of unconditional alcohol use model with intercept set at 0, intercept variance (Est = 4.49, SE = .80), slope (Est = .21, SE = .07), slope variance (Est = .39, SE = .10), BIC (3526).

= BIC in parenthesis represents fit with additional time-varying covariates unconstrained over time.

p<.05,

p<.01

p<.001.

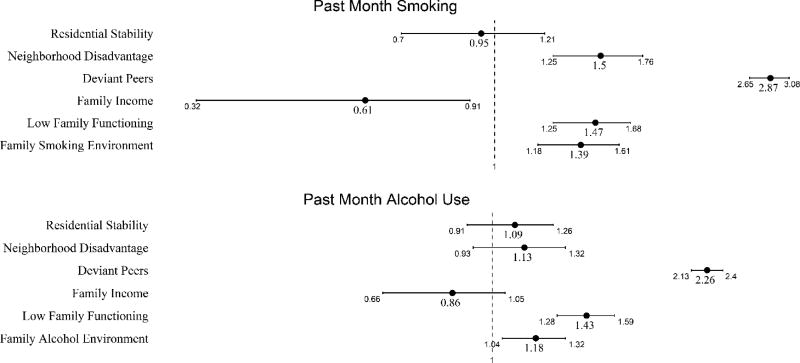

Figure 2.

Odd ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for neighborhood, family, and peer factors predicting past month smoking and alcohol use from grades 5 to 9 after controlling for average growth in smoking and alcohol use. Estimates are conditional on sociodemographic differences in overall intercept and slope of smoking and alcohol use. Each OR indicates that a one standard deviation increase in the predictor corresponds to an increase or decrease in the odds of increased smoking or alcohol use across grades 5 through 9. The x-axis is presented on the log scale and CIs that include 1 indicate a non-statistically significant association.

Table 4.

Indirect Effects of Neighborhood Disadvantage on Smoking and Alcohol Use

| Smoking

|

Alcohol Use

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Est. (SE)

|

Est. (SE)

|

|

| NH Disadvantage -> Family Income | ||

| Indirect Effect | .08 (.03) ** | .03 (.02) |

| Total Effect | .49 (.14) *** | .14 (.10) |

| NH Disadvantage -> Low Family Functioning | ||

| Indirect Effect | .01 (.01) | .01 (.01) |

| Total Effect | .43 (.14) ** | .13 (.10) |

| NH Disadvantage -> Family Substance Use Environment a | ||

| Indirect Effect | .01 (.01) | .00 (.01) |

| Total Effect | .42 (.13) ** | .12 (.10) |

| NH Disadvantage -> Deviant Peers | ||

| Indirect Effect | .08 (.03) * | .06 (.03) * |

| Total Effect | .48 (.14) *** | .18 (.10) |

Notes. N=808; Est. = estimate; SE = standard error; NH = neighborhood; each mediation model was run separately; all models controlled for associations between sociodemographic, family, and peer factors and each mediator;

= family smoking environment and family alcohol environment corresponded to each outcome.

p<.05,

p<.01,

p<.001.

Results

Results of unconditional growth models for both past month smoking and alcohol use showed significant variance on the intercept and slope warranting the inclusion of time-fixed and time-varying covariates. As expected, we found significant differences in initial levels of use and growth over time in smoking and alcohol use by time-fixed sociodemographic factors. All results for time-fixed sociodemographic factors described below are after controlling for time-varying neighborhood, family, and peer factors in Model 2. Females had significantly lower levels of initial alcohol use as compared to males and no differences in growth of alcohol use over time. No differences in initial levels of use or growth in smoking were noted for females. African Americans had significantly lower levels of initial smoking and alcohol use as compared to European Americans and no significant differences in growth of either smoking or alcohol use over time.2 Asian Americans also had lower initial levels of alcohol use and smoking as compared to European Americans. Asian Americans, however, showed faster growth in alcohol use over time as compared to European Americans and no differences for growth in smoking. Native Americans showed no differences in initial levels of smoking and alcohol use and faster growth in both smoking and alcohol use over time as compared to European Americans. Youth living in two parent households had no differences in initial levels of smoking or alcohol use and slower growth in alcohol use over time as compared to youth not living in two parent households. No differences in initial levels of use or change in use over time were found for adolescents with at least one college educated parent on either smoking or alcohol use when compared to adolescent without a college educated parent.

Results of Model 1 for smoking indicated that greater neighborhood disadvantage was associated with increased smoking after controlling for time-fixed sociodemographic factors and average growth in smoking. No significant association was noted between residential stability and smoking. In Model 2, increased neighborhood disadvantage, low family functioning, family smoking environment, and affiliation with deviant peers were uniquely associated with higher levels of smoking from grades 5 to 9. Higher family income was uniquely associated with lower levels of smoking from grades 5 to 9. The inclusion of time-varying family and peer factors in Model 2 attenuated the association between neighborhood disadvantage and smoking observed in Model 1. Mediation analyses found an indirect effect of neighborhood disadvantage on smoking through both family income and deviant peers in Model 2.

Results of Model 1 for alcohol use found that increased neighborhood disadvantage was associated with higher levels of alcohol use after controlling for time-fixed sociodemographic factors and average growth in alcohol use. No significant association was noted between residential stability and alcohol use. Results of Model 2 for alcohol use showed a similar pattern of unique associations between increased low family functioning, family alcohol use environment, and affiliation with deviant peers and higher levels of alcohol use. No significant association between family income and alcohol use was noted in Model 2. The inclusion of time-varying family and peer factors in Model 2 rendered the association between neighborhood disadvantage and alcohol use observed in Model 1 non-significant. Mediation analyses found an indirect effect of neighborhood disadvantage on alcohol use through affiliation with deviant peers.

We conducted two sets of sensitivity tests to assess potential non-independence among observations. Separate models were estimated clustering standard errors with respect to grade 5 and grade 9 home addresses. Clustered and un-clustered models produced substantively similar results for both smoking and alcohol use and, in most cases, the standard errors were identical across models. Further sensitivity tests were conducted with two parent household and parent education modeled as time-varying covariates. These models showed worse fit on SABIC and did not alter the substantive interpretation of other coefficients in the models. As a result, two parent household and parent education were included as time-fixed predictors measured at the 5th grade.

Discussion

The results of this study help clarify the role of neighborhood, family, and peer contextual factors in the etiology of early onset adolescent smoking and alcohol use. Neighborhood-focused studies have rarely considered the dynamics of neighborhood socioeconomic, family, and peer factors over time (Wodtke et al., 2016; Wodtke et al., 2011). Furthermore, few studies have adequately accounted for family-level sociodemographic controls in estimating associations between neighborhood socioeconomics and youth substance use (Leventhal & Brooks-Gunn, 2000). Employing latent growth curve modeling in conjunction with time-varying measures of neighborhood, family, and peer factors, we found evidence that living in more socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods was associated with both early adolescent smoking and alcohol use above and beyond average growth in smoking and alcohol use from grades 5 to 9. Low family functioning, more permissive family substance use environments, and deviant peer affiliations also predicted greater youth smoking and alcohol use after accounting for average growth in smoking and alcohol use. A unique association of neighborhood disadvantage with smoking, but not alcohol use, persisted in fully controlled models accounting for a range of family, peer, and sociodemographic factors.

Higher family income was uniquely protective against smoking but not alcohol use, suggesting that neighborhood-level and family-level socioeconomic factors are particularly relevant for the etiology of early adolescent smoking. This is consistent with findings from prior studies showing that while smoking has decreased across the American population in the past decade, rates have remained persistently higher among those in lower socioeconomic groups (Hill, Amos, Clifford, & Platt, 2014; Leventhal, 2016). Our findings suggest that tobacco-related health disparities associated with neighborhood and family socioeconomic factors were already detectable in early adolescence. Furthermore, given the increased risk of nicotine dependence conferred by early adolescent smoking (Grant, 1998; Kendler et al., 2013), our results suggest that childhood neighborhood and family socioeconomics can impact tobacco-related health disparities across the life course net of other family and peer contextual risk factors.

Future neighborhood-based studies investigating adolescent smoking and alcohol use should consider three key features of this study. First, employing measures of neighborhood socioeconomics across time may improve the ability to detect neighborhood effects by more accurately reflecting neighborhood exposure (Wodtke et al., 2011). Second, our results indicate that the effect of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage on smoking and alcohol use was mediated by increased affiliation with deviant peers even after controlling for family-level sociodemographic factors as well as family income, family functioning, and permissiveness of family substance using environments. Examining only direct effects of neighborhood socioeconomics on adolescent smoking and alcohol use may obfuscate important indirect associations between neighborhoods, other contexts, and adolescent substance use (Fagan, Wright, & Pinchevsky, 2015). Finally, neighborhood socioeconomics may differentially impact smoking or alcohol use. Past studies examining the role of neighborhood contexts in adolescent development have not found direct effects of neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage when collapsing measures of substance use and delinquency together into a more general measure of problem behavior (Elliott et al., 2006; Elliott et al., 1996). Our results suggest that neighborhood and family-level socioeconomics operate differentially with respect to early smoking and alcohol use among adolescents.

Future studies should also examine these associations with more recent cohorts of adolescents. Long term trends in smoking and alcohol use among youth (Johnston, O'Malley, Bachman, & Schulenberg, 2011), shifting social norms regarding the perceived harmfulness of smoking and alcohol use, evolving tobacco and alcohol control policies (Hill et al., 2014; Jenson & Bender, 2014), the dynamics of neighborhood socioeconomic trends (Allard, 2017), or successful implementation of youth substance use prevention programming (Jenson & Bender, 2014) over the past 25 years may all potentially impact the results reported by this study. In addition, while our results did show direct and mediated associations between neighborhood socioeconomic disadvantage and youth smoking and alcohol use, no unique associations were noted for residential stability in initial or fully controlled models. While empirical and theoretical work has shown residential stability to be an important component of informal social control or collective efficacy (Sampson et al., 2002), few studies have found a direct impact of residential stability on youth substance use. Further studies should explicitly test the impact of residential stability through informal social control or collective efficacy and, in turn, youth substance use.

The current findings also offer evidence for a unique contribution of poor family functioning and more permissive family substance use environments to both adolescent smoking and alcohol use. While general family functioning and substance using family environments have shown relevance for young adult substance use (Bailey et al., 2014; Bailey et al., 2011; Hill et al., 2005; Kosterman et al., 2000), few studies have examined the role of general and substance-specific family environments for early adolescent smoking and alcohol use in conjunction with neighborhood socioeconomic factors and deviant peer affiliations (Chuang et al., 2005). Given the contribution of early smoking and alcohol use to the substantial societal costs associated with smoking and alcohol-related disease and disability across the life-course (Centers for Disease Control Prevention, 2008; Sacks et al., 2015), strategies for preventing or delaying early adolescent smoking and alcohol use by addressing modifiable family and peer risk factors are essential (Catalano et al., 2012; Spoth et al., 1999). Specifically, preventive interventions improving family functioning during adolescence have shown the ability to inhibit deviant peer affiliations and early initiation of substance use (Harrop & Catalano, 2016; Van Ryzin, Stormshak, & Dishion, 2012). Importantly, family functioning and family substance use did not mediate the impact of neighborhood disadvantage on adolescent smoking and alcohol use suggesting the relevance of universal preventive interventions. Future studies explicitly testing the ability of preventive interventions to mitigate the negative impact of neighborhood disadvantage on deviant peer affiliations and early adolescent substance use can provide important information to practitioners and prevention scientists. Challenges may exist, however, for addressing the direct impact of neighborhood disadvantage on smoking and identification of malleable mechanisms by which neighborhood socioeconomics may impact adolescent smoking is needed. For example, observational studies have found that socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods contain a higher concentration of tobacco-related advertising which, in turn, has been linked to smoking among adolescents (Henriksen, Schleicher, Feighery, & Fortmann, 2010; Lee, Henriksen, Rose, Moreland-Russell, & Ribisl, 2015). Further research investigating strategies to counteract the negative impact of tobacco marketing on adolescents living in disadvantaged neighborhoods may prove important for addressing tobacco-related health disparities.

It is important to note that ethnicity and family structure were significantly associated with both smoking and alcohol use. Adolescents living in two parent households showed slower growth in alcohol use. While this finding concurs with previous studies (Blum et al., 2000; Hoffmann & Johnson, 1998), our results suggest the reduced risk for alcohol use associated with living in a two parent housdhold persists after also accounting for differences in race/ethnicity, neighborhood contexts, family SES, low family functioning, family substance use environments, and affiliations with deviant peers. Further research should take note of the role of family structure in early adolescent alcohol use. In concert with previous studies with the SSDP sample (Hill et al., 2005; Kosterman et al., 2000) and research with nationally representative data (Blum et al., 2000; Hoffmann & Johnson, 1998), our results also showed differences in both early adolescent smoking and alcohol use by race/ethnicity. Importantly, these differences were not explained by family structure, neighborhood contexts, low family functioning, family SES, or affiliations with deviant peers. Further research should consider other possible mechanisms related to differences in early adoelscent substance use across racial or ethnic groups.

Some limitations of the current study should also be noted. First, the SSDP study was not designed to assess neighborhood effects. As such, there are few students per census block group which precludes multilevel modeling strategies to examine contextual effects (Jackson et al., 2014). Secondly, the SSDP survey did not gather sufficient data to assess the role of parent and peer smoking from grades 5 to 9. Given established associations between SES and smoking among adults (Hiscock et al., 2012) and the importance of peer behavior for adolescent substance use, it is possible that the direct effect of neighborhood disadvantage on adolescent smoking would be partially mediated by a measure of parent and peer smoking. Additionally, the results of the current study should be replicated with more current cohorts of adolescents. Future analyses should seek to further disentangle general and substance specific environmental risk factors for adolescent substance use.

Conclusion

Understanding the role of contextual factors associated with increased early adolescent smoking and alcohol use is key for preventing both short and long term harms from substance use. Results of this study help to advance a body of largely inconsistent findings regarding the potential impact of neighborhood contexts on youth substance use (Bryden, Roberts, Petticrew, & McKee, 2013; Hiscock et al., 2012; Jackson et al., 2014; Karriker-Jaffe, 2011; Sampson et al., 2002). Incorporating suggestions from neighborhood-focused scholars, we found that youth growing up in socioeconomically disadvantaged neighborhoods are at increased risk for smoking and alcohol use above and beyond average growth in smoking and alcohol use from grades 5 to 9. Some of the increased risk associated with neighborhood contexts could be attributed to greater affiliation with deviant peers. Unique risks for early onset smoking and alcohol use were also associated with modifiable family factors including the quality of family functioning and the permissiveness of family substance use environments. These findings may be particularly relevant for those designing and implementing programs to prevent early onset of youth smoking and alcohol use.

Acknowledgments

Funding

Data collection for this study was supported by grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (5R01DA003721 and 5R01DA033956). Support was provided a National Poverty Research Center Dissertation Fellowship awarded by the Institute for Research on Poverty at the University of Wisconsin–Madison with funding from the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Cooperative Agreement number AE00103. Support was provided by a Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development research infrastructure grant, No. R24HD042828; and training grant No. T32HD007543 to the Center for Studies in Demography and Ecology at the University of Washington. The opinions and conclusions expressed herein are solely those of the author and should not be construed as representing the opinions or policy of any agency of the Federal government.

Footnotes

Some SSDP participants received a social development intervention during elementary school (Hawkins et al., 1992b). Sensitivity tests controlling for the intervention in Model 2 for both smoking and alcohol use did not show any substantive changes to the findings reported in Table 3.

The direction and magnitude of associations between time-fixed sociodemographic factors and both smoking and alcohol use was similar across models; one difference was noted for African Americans. Africans Americans showed no differences in initial levels of smoking and slower growth in smoking over time as compared to European Americans in Model 1. With the inclusion of time-varying family and peer factors in Model 2, African Americans showed lower initial levels of smoking but no differences in growth in smoking when compared to European Americans. This change is likely attributable to the improved precision in estimation of the growth curve intercept and slope after including time-varying family and peer factors in Model 2.

Authors’ Contributions C.C. conceived of the study design, performed the statistical analyses, interpreted the data, and drafted the manuscript; R.K. participated in the data interpretation and helped draft the manuscript; R.C. participated in data interpretation and helped draft the manuscript; K.G. participated in the statistical analyses, data interpretation, and helped draft the manuscript; J.H. participated in data interpretation and helped draft the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Compliance with Ethical Standards

Conflict of Interest

R.F. Catalano is on the board of Channing Bete Company, distributer of prevention programs. The remaining authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

All procedures performed in studies involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical standards of the University of Washington and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards.

Informed Consent

Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

References

- Allard SW. Places in Need: The Changing Geography of Poverty. Russell Sage Foundation; 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Asparouhov T, Muthén B. Multiple imputation with Mplus. MPlus Web Notes 2010 [Google Scholar]

- Bailey J, Samek D, Keyes M, Hill K, Hicks B, McGue M, Haggerty K. General and substance-specific predictors of young adult nicotine dependence, alcohol use disorder, and problem behavior: Replication in two samples. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2014;138:161–168. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2014.02.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey JA, Hill KG, Meacham MC, Young SE, Hawkins JD. Strategies for characterizing complex phenotypes and environments: General and specific family environmental predictors of young adult tobacco dependence, alcohol use disorder, and co-occurring problems. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2011;118(2):444–451. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum RW, Beuhring T, Shew ML, Bearinger LH, Sieving RE, Resnick MD. The effects of race/ethnicity, income, and family structure on adolescent risk behaviors. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(12):1879. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.12.1879. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau N, Peterson EL. Smoking cessation in young adults: age at initiation of cigarette smoking and other suspected influences. American Journal of Public Health. 1996;86(2):214–220. doi: 10.2105/ajph.86.2.214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody GH, Conger R, Gibbons FX, Ge X, McBride Murry V, Gerrard M, Simons RL. The influence of neighborhood disadvantage, collective socialization, and parenting on African American children's affiliation with deviant peers. Child development. 2001;72(4):1231–1246. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.00344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. American psychologist. 1977;32(7):513. [Google Scholar]

- Bryden A, Roberts B, Petticrew M, McKee M. A systematic review of the influence of community level social factors on alcohol use. Health & place. 2013;21:70–85. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes HF, Miller BA. The relationship between neighborhood characteristics and effective parenting behaviors: The role of social support. Journal of family issues. 2012;33(12):1658–1687. doi: 10.1177/0192513X12437693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cambron C, Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The social development model. In: Press OU, editor. The Oxford Handbook of Life-Course and Developmental Criminology. in press. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Fagan AA, Gavin LE, Greenberg MT, Irwin CE, Ross DA, Shek DT. Worldwide application of prevention science in adolescent health. The Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1653–1664. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60238-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Hawkins JD. The social development model. Delinquency and crime. 1996;149:197. [Google Scholar]

- Catalano RF, Morrison DM, Wells EA, Gillmore MR, Iritani B, Hawkins JD. Ethnic differences in family factors related to early drug initiation. Journal of studies on alcohol. 1992;53(3):208–217. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1992.53.208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control Prevention. Smoking-attributable mortality, years of potential life lost, and productivity losses--United States, 2000–2004. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report. 2008;57(45):1226. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chuang Y-C, Ennett ST, Bauman KE, Foshee VA. Neighborhood influences on adolescent cigarette and alcohol use: mediating effects through parent and peer behaviors. Journal of health and social behavior. 2005;46(2):187–204. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Curran PJ, Hussong AM. The use of latent trajectory models in psychopathology research. Journal of abnormal psychology. 2003;112(4):526. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.112.4.526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currie C, Zanotti C, Morgan A, Currie D, de Looze M, Roberts C, Barnekow V. Social determinants of health and well-being among young people. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) study: international report from the. 2009;2010:271. [Google Scholar]

- Darling N, Cumsille P. Theory, measurement, and methods in the study of family influences on adolescent smoking. Addiction. 2003;98(s1):21–36. doi: 10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.3.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Devenish B, Hooley M, Mellor D. The Pathways Between Socioeconomic Status and Adolescent Outcomes: A Systematic Review. American journal of community psychology. 2017 doi: 10.1002/ajcp.12115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diez Roux AV, Mair C. Neighborhoods and health. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2010;1186(1):125–145. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05333.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Menard S, Rankin B, Elliott A, Wilson WJ, Huizinga D. Good kids from bad neighborhoods: Successful development in social context. Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott DS, Wilson WJ, Huizinga D, Sampson RJ, Elliott A, Rankin B. The effects of neighborhood disadvantage on adolescent development. Journal of Research in Crime and Delinquency. 1996;33(4):389–426. [Google Scholar]

- Epstein M, Hill KG, Bailey JA, Hawkins JD. The effect of general and drug-specific family environments on comorbid and drug-specific problem behavior: A longitudinal examination. Developmental psychology. 2013;49(6):1151. doi: 10.1037/a0029309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ewing SWF, Sakhardande A, Blakemore S-J. The effect of alcohol consumption on the adolescent brain: A systematic review of MRI and fMRI studies of alcohol-using youth. NeuroImage: Clinical. 2014;5:420–437. doi: 10.1016/j.nicl.2014.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fagan AA, Wright EM, Pinchevsky GM. A multi-level analysis of the impact of neighborhood structural and social factors on adolescent substance use. Drug and alcohol dependence. 2015;153:180–186. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2015.05.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galea S, Nandi A, Vlahov D. The social epidemiology of substance use. Epidemiologic reviews. 2004;26(1):36–52. doi: 10.1093/epirev/mxh007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF. Age at smoking onset and its association with alcohol consumption and DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of substance abuse. 1998;10(1):59–73. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(99)80141-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Dawson DA. Age at onset of alcohol use and its association with DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: results from the National Longitudinal Alcohol Epidemiologic Survey. Journal of substance abuse. 1997;9:103–110. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(97)90009-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant BF, Stinson FS, Harford TC. Age at onset of alcohol use and DSM-IV alcohol abuse and dependence: a 12-year follow-up. Journal of substance abuse. 2001;13(4):493–504. doi: 10.1016/s0899-3289(01)00096-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttmannova K, Bailey JA, Hill KG, Lee JO, Hawkins JD, Woods ML, Catalano RF. Sensitive periods for adolescent alcohol use initiation: Predicting the lifetime occurrence and chronicity of alcohol problems in adulthood. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2011;72(2):221–231. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2011.72.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson MD, Chen E. Socioeconomic status and health behaviors in adolescence: a review of the literature. Journal of behavioral medicine. 2007;30(3):263. doi: 10.1007/s10865-007-9098-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrop E, Catalano RF. Evidence-based prevention for adolescent substance use. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2016;25(3):387–410. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2016.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Miller JY. Risk and protective factors for alcohol and other drug problems in adolescence and early adulthood: implications for substance abuse prevention. Psychological bulletin. 1992a;112(1):64. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.112.1.64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Morrison DM, O'Donnell J, Abbott RD, Day LE. The Seattle Social Development Project: Effects of the first four years on protective factors and problem behaviors. In: McCord J, Tremblay RE, editors. Preventing antisocial behavior: Interventions from birth through adolescence. New York: Guilford Press; 1992b. pp. 139–161. [Google Scholar]

- Hawkins JD, Graham JW, Maguin E, Abbott R, Hill KG, Catalano RF. Exploring the effects of age of alcohol use initiation and psychosocial risk factors on subsequent alcohol misuse. Journal of studies on alcohol. 1997;58(3):280. doi: 10.15288/jsa.1997.58.280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henriksen L, Schleicher NC, Feighery EC, Fortmann SP. A longitudinal study of exposure to retail cigarette advertising and smoking initiation. Pediatrics. 2010;126(2):232–238. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-3021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrenkohl TI, Hawkins JD, Abbott RD, Guo J. Correspondence between youth report and census measures of neighborhood context. Journal of Community Psychology. 2002;30(3):225–233. [Google Scholar]

- Hill KG, Hawkins JD, Catalano RF, Abbott RD, Guo J. Family influences on the risk of daily smoking initiation. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37(3):202–210. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill S, Amos A, Clifford D, Platt S. Impact of tobacco control interventions on socioeconomic inequalities in smoking: review of the evidence. Tobacco Control. 2014;23(e2):e89–e97. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2013-051110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hingson RW, Zha W. Age of drinking onset, alcohol use disorders, frequent heavy drinking, and unintentionally injuring oneself and others after drinking. Pediatrics. 2009;123(6):1477–1484. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-2176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hiscock R, Bauld L, Amos A, Fidler JA, Munafò M. Socioeconomic status and smoking: a review. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2012;1248(1):107–123. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2011.06202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JP, Johnson RA. A national portrait of family structure and adolescent drug use. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1998:633–645. [Google Scholar]

- Hussong AM, Curran PJ, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Carrig MM. Substance abuse hinders desistance in young adults' antisocial behavior. Development and psychopathology. 2004;16(4):1029–1046. doi: 10.1017/s095457940404012x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoldsby EM, Shaw DS, Winslow E, Schonberg M, Gilliom M, Criss MM. Neighborhood disadvantage, parent–child conflict, neighborhood peer relationships, and early antisocial behavior problem trajectories. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2006;34(3):293–309. doi: 10.1007/s10802-006-9026-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson MI, Mare RD. Cross-sectional and longitudinal measurements of neighborhood experience and their effects on children. Social science research. 2007;36(2):590–610. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2007.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson N, Denny S, Ameratunga S. Social and socio-demographic neighborhood effects on adolescent alcohol use: A systematic review of multi-level studies. Social science & medicine. 2014;115:10–20. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jencks C, Mayer SE. The social consequences of growing up in a poor neighborhood. Inner-city poverty in the United States. 1990;111:186. [Google Scholar]

- Jenson JM, Bender K. Preventing child and adolescent problem behavior: Evidence-based strategies in schools, families, and communities 2014 [Google Scholar]

- Johnston LD, O'Malley PM, Bachman JG, Schulenberg JE. Monitoring the Future National Survey Results on Drug Use, 1975–2010. Volume I, Secondary School Students. Institute for Social Research 2011 [Google Scholar]

- Karriker-Jaffe KJ. Areas of disadvantage: A systematic review of effects of area-level socioeconomic status on substance use outcomes. Drug and alcohol review. 2011;30(1):84–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00191.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Myers J, Damaj MI, Chen X. Early smoking onset and risk for subsequent nicotine dependence: a monozygotic co-twin control study. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2013;170(4):408–413. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12030321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosterman R, Hawkins JD, Guo J, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. The dynamics of alcohol and marijuana initiation: patterns and predictors of first use in adolescence. American Journal of Public Health. 2000;90(3):360. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.3.360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JG, Henriksen L, Rose SW, Moreland-Russell S, Ribisl KM. A systematic review of neighborhood disparities in point-of-sale tobacco marketing. American Journal of Public Health. 2015;105(9):e8–e18. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AM. The sociopharmacology of tobacco addiction: implications for understanding health disparities. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2016;18(2):110–121. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntv084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal T, Brooks-Gunn J. The neighborhoods they live in: the effects of neighborhood residence on child and adolescent outcomes. Psychological bulletin. 2000;126(2):309. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.126.2.309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lydon DM, Wilson SJ, Child A, Geier CF. Adolescent brain maturation and smoking: what we know and where we’re headed. Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews. 2014;45:323–342. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2014.07.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathur C, Erickson DJ, Stigler MH, Forster JL, Finnegan JR., Jr Individual and neighborhood socioeconomic status effects on adolescent smoking: a multilevel cohort-sequential latent growth analysis. American Journal of Public Health. 2013;103(3):543–548. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.300830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén LK, Muthén BO. Mplus Version 7 user’s guide. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Office of Surgeon General. Facing Addiction in America: The Surgeon General’s Report on Alcohol, Drugs, and Health. Washington, D.C.: 2016. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oxford ML, Harachi TW, Catalano RF, Abbott RD. Preadolescent predictors of substance initiation: A test of both the direct and mediated effect of family social control factors on deviant peer associations and substance initiation. The American journal of drug and alcohol abuse. 2001;27(4):599–616. doi: 10.1081/ada-100107658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick ME, Wightman P, Schoeni RF, Schulenberg JE. Socioeconomic status and substance use among young adults: a comparison across constructs and drugs. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2012;73(5):772–782. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2012.73.772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehm J, Dawson D, Frick U, Gmel G, Roerecke M, Shield KD, Grant B. Burden of disease associated with alcohol use disorders in the United States. Alcoholism: Clinical and Experimental Research. 2014;38(4):1068–1077. doi: 10.1111/acer.12331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosa MW, Jones S, Tein J-Y, Cree W. Prevention science and neighborhood influences on low-income children's development: Theoretical and methodological issues. American journal of community psychology. 2003;31(1–2):55–72. doi: 10.1023/a:1023070519597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan SM, Jorm AF, Lubman DI. Parenting factors associated with reduced adolescent alcohol use: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry. 2010;44(9):774–783. doi: 10.1080/00048674.2010.501759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sacks JJ, Gonzales KR, Bouchery EE, Tomedi LE, Brewer RD. 2010 national and state costs of excessive alcohol consumption. American journal of preventive medicine. 2015;49(5):e73–e79. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2015.05.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampson RJ, Morenoff JD, Gannon-Rowley T. Assessing" neighborhood effects": Social processes and new directions in research. Annual review of sociology. 2002:443–478. [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford university press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Skinner ML, Haggerty KP, Catalano RF. Parental and peer influences on teen smoking: Are White and Black families different? Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 2009;11(5):558–563. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntp034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spoth R, Reyes ML, Redmond C, Shin C. Assessing a public health approach to delay onset and progression of adolescent substance use: latent transition and log-linear analyses of longitudinal family preventive intervention outcomes. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1999;67(5):619. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.67.5.619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tobler AL, Komro KA, Maldonado-Molina MM. Relationship between neighborhood context, family management practices and alcohol use among urban, multi-ethnic, young adolescents. Prevention Science. 2009;10(4):313–324. doi: 10.1007/s11121-009-0133-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trim RS, Chassin L. Neighborhood socioeconomic status effects on adolescent alcohol outcomes using growth models: Exploring the role of parental alcoholism. Journal of studies on alcohol and drugs. 2008;69(5):639–648. doi: 10.15288/jsad.2008.69.639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Ryzin MJ, Stormshak EA, Dishion TJ. Engaging parents in the family check-up in middle school: Longitudinal effects on family conflict and problem behavior through the high school transition. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2012;50(6):627–633. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.10.255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viner RM, Ozer EM, Denny S, Marmot M, Resnick M, Fatusi A, Currie C. Adolescence and the social determinants of health. The Lancet. 2012;379(9826):1641–1652. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60149-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch KA, Carson A, Lawrie SM. Brain structure in adolescents and young adults with alcohol problems: systematic review of imaging studies. Alcohol and alcoholism. 2013;48(4):433–444. doi: 10.1093/alcalc/agt037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson W. Truly Disadvantaged: The Inner City, the Underclass, and Public Policy 1987 [Google Scholar]

- Wodtke GT, Elwert F, Harding DJ. Neighborhood Effect Heterogeneity by Family Income and Developmental Period 1. American journal of sociology. 2016;121(4):1168–1222. doi: 10.1086/684137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wodtke GT, Harding DJ, Elwert F. Neighborhood effects in temporal perspective the impact of long-term exposure to concentrated disadvantage on high school graduation. American Sociological Review. 2011;76(5):713–736. doi: 10.1177/0003122411420816. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]