ABSTRACT

Objective:

To evaluate systematically the effects of continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) on blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).

Methods:

The Cochrane Library, PubMed, ScienceDirect, and the Web of Science were searched for studies investigating the effects of CPAP on blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension and OSA. The selected studies underwent quality assessment and meta-analysis, as well as being tested for heterogeneity.

Results:

Six randomized controlled trials were included in the meta-analysis. The pooled estimates of the changes in mean systolic blood pressure and mean diastolic blood pressure (as assessed by 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring) were −5.40 mmHg (95% CI: −9.17 to −1.64; p = 0.001; I2 = 74%) and −3.86 mmHg (95% CI: −6.41 to −1.30; p = 0.00001; I2 = 79%), respectively.

Conclusions:

CPAP therapy can significantly reduce blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension and OSA.

Keywords: Continuous positive airway pressure; Sleep apnea, obstructive; Hypertension; Meta-analysis

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a chronic disease characterized by recurrent upper airway collapse during sleep leading to intermittent hypoxemia and sleep disruption.1 It has been estimated that 24% of all males in the 30- to 60-year age bracket and 9% of all females in the same age bracket have OSA.2 Several studies have shown that OSA is a risk factor for cardiovascular diseases, including hypertension, heart failure, atrial fibrillation, and coronary artery disease.3-6 In 2003, the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure identified OSA as an important identifiable cause of hypertension.7

Resistant hypertension has been defined as blood pressure that remains above goal despite concomitant use of at least three classes of antihypertensive medications. Individuals with controlled blood pressure using at least four classes of antihypertensive medications are also considered to have resistant hypertension. International guidelines now recognize OSA as one of the most common risk factors for resistant hypertension.8 Gonçalves et al. found that the risk of resistant hypertension is nearly five times higher in patients with OSA.9 Similarly, Calhoun et al. found that 63% of all patients presenting to a clinic for resistant hypertension were at high risk for OSA on the basis of their responses to the Berlin Questionnaire.10 In a prospective observational study, Lavie et al. found that the prevalence and severity of hypertension increased as the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) increased.11

Continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) is the most widely accepted form of therapy for OSA and remains the gold standard for treatment. Although there is a significant amount of data on the effect of CPAP on hypertension, data on resistant hypertension are limited.12 Therefore, we performed a meta-analysis to evaluate the efficacy of CPAP in patients with OSA and resistant hypertension.

METHODS

Inclusion criteria

We sought to evaluate systematically randomized clinical trials of the effects that CPAP therapy has on the blood pressure of patients with OSA and resistant hypertension. We included studies including patients over 18 years of age diagnosed with OSA and resistant hypertension, the latter having been diagnosed by ambulatory blood pressure monitoring (ABPM). Interventions included a control group receiving conventional antihypertensive therapy or placebo and a treatment group receiving CPAP therapy, treatment group patients having completed the treatment. Endpoints included mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) and mean diastolic blood pressure (DBP) as assessed by 24-h ABPM.

Exclusion criteria

The exclusion criteria were as follows: studies in which the sample size was < 10; nonrandomized controlled studies; early studies (i.e., studies published before 2010); repeated trials; studies with no control group; studies in which patients were used as their own controls; studies not providing the full original data; studies whose full-text articles were unavailable; and studies whose authors we were unable to contact.

Literature retrieval

We searched the following databases: the Cochrane Library; ScienceDirect; PubMed; and the Web of Science. We used the following search terms: “continuous positive airway pressure”; “CPAP”; “obstructive sleep apnea”; “OSA”; “apnea-hypopnea index”; “AHI”; “resistant hypertension”; “RH”; “refractory hypertension”; “resistant high blood pressure”; “randomized controlled trial”; and “RCT”. The search was limited to original research articles published between January of 2010 and January of 2016. In addition, the ResearchGate social networking website was used in order to contact researchers for additional relevant studies.

Literature screening

In order to select the articles for inclusion, two researchers independently applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria to all of the studies selected by the aforementioned method. In cases of disagreement, a third member of the research team was consulted. Relevant data were extracted and cross-checked. In cases in which important data were missing from the selected studies, the authors were contacted by email or phone.

Quality assessment

The quality of the selected studies was assessed by the Jadad score, which ranges from 0 to 5. Articles with a Jadad score of more than 3 were included in our meta-analysis. Two researchers independently assessed the quality of the studies by applying the Jadad criteria. In cases of disagreement, a third member of the research team was consulted. All relevant data were subsequently extracted.

Statistical analysis

Meta-analysis

Meta-analysis was performed with the Review Manager (RevMan) software, version 5.3 (The Nordic Cochrane Centre, Copenhagen, Denmark). The I2 statistics was used in order to assess heterogeneity (clinical heterogeneity and statistical heterogeneity), the level of significance being set at p < 0.1. For studies showing clinical homogeneity and statistical homogeneity (i.e., p > 0.1 and I2 ≤ 50%), a fixed effect model was used; for those showing clinical homogeneity and statistical heterogeneity (i.e., p < 0.1 and I2 > 50%), a random effects model was used. In the presence of significant clinical heterogeneity, only descriptive statistics were used. Continuous variables included weighted mean difference and standardized mean difference, the effects being expressed as 95% CIs. The level of significance was set at p < 0.05. Funnel plots were used in order to determine whether there was significant publication bias.

Heterogeneity test

Heterogeneity was analyzed by the method of subgroup analysis, which consists of dividing the data into smaller units and comparing the subgroups. On the basis of the AHI, body mass index (BMI), SBP, DBP, total duration of CPAP treatment, mean daily duration of CPAP treatment, Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) score, and geographic location of the institutions, we divided the study sample into eight subgroups in order to analyze potential factors leading to heterogeneity.

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analysis was performed by excluding studies that might affect the analysis and by using different correlation coefficients to observe the stability of the results.

RESULTS

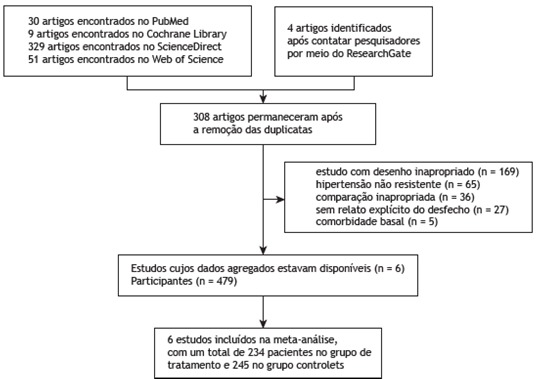

A total of 423 articles were initially retrieved, and a total of 308 remained after duplicate entries were removed. Of the remaining articles, 613-18 were included in our meta-analysis (Figure 1). The 6 included articles were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) and comprised a total of 479 patients. Of those, 245 had been control group patients and 234 had been treatment group patients. The basic characteristics of the 6 RCTs included in the meta-analysis are shown in Table 1. Table 2 shows the baseline AHI, ESS score, BMI, SBP (as assessed by 24-h ABPM), and DBP (as assessed by 24-h ABPM) in the 6 RCTs included in our meta-analysis.

Figure 1. Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram of the process of including studies in our meta-analysis.

Table 1. Basic characteristics of the six studies included in the meta-analysis.

| Author | Year | Number of patients | Male gender, % | Mean age ± SD, years | CPAP compliance, h | Type of study | Treatment duration | Method of BP measurement | Country | Jadad score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muxfeldt et al.(17) | 2015 | 46 (CPAP) | 37.9 | 60.8 ± 8.0 | 4.8 | RCT | 6 months | ABPM | Brazil | 3 |

| 60 (Control) | ||||||||||

| de Oliveira et al.(13) | 2014 | 24 (CPAP) | 58 | 59.5 ± 7.3 | ≥ 4 | RCT | 8 weeks | ABPM | Brazil | 4 |

| 23 (Control) | ||||||||||

| Lloberes et al.(14) | 2014 | 27 (CPAP) | 72.4 | 58.7 ± 9.5 | 5.7 ± 1.5 | RCT | 3 months | ABPM | Spain | 3 |

| 29 (Control) | ||||||||||

| Pedrosa et al.(18) | 2013 | 19 (CPAP) | 74 | 57 ± 2a | 6.01 ± 0.20 | RCT | 6 months | ABPM | Brazil | 3 |

| 16 (Control) | ||||||||||

| Martínez-García et al.(16) | 2013 | 98 (CPAP) | 72.4 | 56.0 ± 9.5 | 5 ± 1.9 | RCT | 3 months | ABPM | Spain | 3 |

| 96 (Control) | ||||||||||

| Lozano et al.(15) | 2010 | 20 (CPAP) | 75.9 | 59.2 ± 8.7 | 5.6 ± 1.5 | RCT | 3 months | ABPM | Spain | 3 |

| 21 (Control) |

CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; BP: blood pressure; RCT: randomized controlled trial; and ABPM: ambulatory blood pressure monitoring. aData expressed as mean ± SE.

Table 2. Baseline apnea-hypopnea index, Epworth Sleepiness Scale score, body mass index, systolic blood pressure (as assessed by 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring), and diastolic blood pressure (as assessed by 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring).a.

| Study | AHI | ESS score | BMI | SBP | DBP |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Muxfeldt et al.(17) | 41 (21) | 11 (6) | 33.4 (5.3) | 129 (16) | 75 (12) |

| de Oliveira et al.(13) | 20 (18-31)b | 10 (6-15)b | 29.8 ± 4.4c | 148 ± 17 | 88 ± 13 |

| Lloberes et al.(14) | 50.1 ± 20.6 | 6.76 ± 3.7 | 31.4 (4.9) | 139.2 ± 11.5 | 80.8 ± 10.8 |

| Pedrosa et al.(18) | 29 (24-48)b | 10 ± 1c | 32 (28-39)b | 162 ± 4 | 97 ± 2 |

| Martínez-García et al.(16) | 40.4 (18.9) | 9.1 (3.7) | 34.1 (5.4) | 144.2 (12.5) | 83.0 (10.5) |

| Lozano et al.(15) | 52.67 ± 21.5 | 6.14 ± 3.30 | 30.8 ± 5.0 | 129 (16) | 75 (12) |

AHI: apnea-hypopnea index; ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale; BMI: body mass index; SBP: systolic blood pressure; and DBP: diastolic blood pressure. aValues expressed as n (%) or mean ± SD, except where otherwise indicated. bData expressed as median (range). cData expressed as mean ± SE.

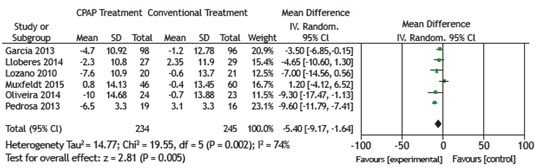

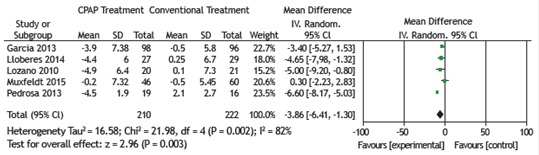

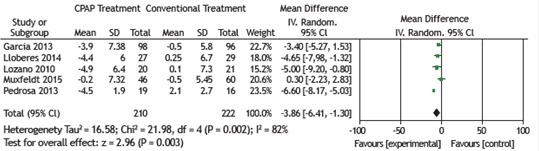

All 6 RCTs examined the effects of CPAP treatment on mean SBP (as assessed by 24-h ABPM) in patients with OSA and resistant hypertension. The pooled estimate of the change in mean SBP was −5.40 mmHg (95% CI: −9.17 to −1.64; p = 0.005; I2 = 74%). Five of the 6 RCTs examined the effects of CPAP treatment on mean DBP (as assessed by 24-h ABPM) in patients with OSA and resistant hypertension. The pooled estimate of the change in mean DBP was −3.86 mmHg (95% CI: −6.41 to −1.30; p = 0.003; I2 = 82%). There was significant heterogeneity among the studies, and a random effects model was therefore used in order to analyze the results (Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Forest plot of the mean change in systolic blood pressure as assessed by 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and its 95% CI.

Figure 3. Forest plot of the mean change in diastolic blood pressure as assessed by 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring and its 95% CI.

Five studies examined the effects of CPAP treatment on mean daytime and nocturnal SBP in patients with OSA and resistant hypertension. The pooled estimates of the changes in mean daytime SBP and mean nocturnal SBP were −4.11 mmHg (95% CI: −9.06 to −0.84; p = 0.10; I2 = 85%) and −3.17 mmHg (95% CI: −6.25 to −0.09; p = 0.04; I2 = 90%), respectively (Table 3). The pooled estimates of the changes in mean daytime DBP and mean nocturnal DBP were −2.11 mmHg (95% CI: −4.16 to −0.05; p = 0.04; I2 = 0%) and −1.55 mmHg (95% CI: −2.81 to −0.29; p = 0.02; I2 = 0%), respectively (Table 4). Because there was significant heterogeneity among the studies regarding mean daytime SBP/DBP, a random effects model was used in order to analyze the results. Because there was no significant heterogeneity among the studies regarding mean nocturnal SBP/DBP, a fixed effect model was used in order to analyze the results.

Table 3. Subgroup analysis of mean changes in systolic blood pressure as assessed by 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring.

| Subgroup | SBP (as assessed by 24-h ABPM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Mean net change | 95% CI | p; I2 (%) | ||

| AHI | ≥ 30 | 4 | −3.07 | −5.50 to −0.65 | p = 0.01; I2 = 22% |

| > 30 | 2 | −9.58 | −11.70 to −7.46 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 0% | |

| Baseline SBP/DBP, mmHg | > 145/85 | 2 | −9.58 | −11.70 to −7.46 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 0% |

| < 145/85 | 4 | −3.07 | −5.50 to −0.65 | p = 0.01; I2 = 22% | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ≥ 32 | 3 | −6.81 | −8.55 to −5.08 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 89% |

| < 32 | 3 | −6.47 | −10.53 to −2.42 | p = 0.002; I2 = 0% | |

| CPAP compliance, h | > 5 | 4 | −7.47 | −9.18 to −5.76 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 70% |

| ≤ 5 | 1 | 1.20 | −4.12 to 6.52 | p = 0.66; I2 = 0% | |

| Treatment duration, months | > 3 | 2 | −8.03 | −10.06 to −6.00 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 93% |

| ≤ 3 | 4 | −4.71 | −7.29 to −2.12 | p = 0.0004; I2 = 0% | |

| ESS score | ≥ 10 | 3 | −5.89 | −13.33 to 1.55 | p = 0.12; I2 = 85% |

| < 10 | 3 | −4.19 | −6.92 to −1.47 | p = 0.003; I2 = 0% | |

| Location | Europe | 3 | −4.19 | -6.92 to −1.47 | p = 0.003; I2 = 0% |

| South America | 3 | −8.10 | −10.07 to −6.13 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 85% | |

| Study sample size | ≥ 25 | 3 | −0.20 | −0.41 to −0.01 | p = 0.06; I2 = 36% |

| < 25 | 3 | −0.96 | −1.36 to −0.57 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 88% | |

SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; ABPM: ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; AHI: apnea-hypopnea index; BMI: body mass index; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; and ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

Table 4. Subgroup analysis of mean changes in diastolic blood pressure as assessed by 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring.

| Subgroup | DBP (as assessed by 24-h ABPM) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | Mean net change | 95% CI | p; I2 (%) | ||

| AHI | ≥ 30 | 4 | −2.76 | −4.06 to −1.46 | p < 0.0001; I2 = 64% |

| < 30 | 1 | −6.60 | −8.17 to −5.03 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 0% | |

| Baseline SBP/DBP, mmHg | > 145/85 | 1 | −6.60 | −8.17 to −5.03 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 0% |

| < 145/85 | 4 | −2.76 | −4.06 to −1.46 | p < 0.0001; I2 = 64% | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | ≥ 32 | 3 | −4.24 | −5.32 to −3.15 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 91% |

| < 32 | 2 | −4.79 | −7.39 to −2.18 | p = 0.0003; I2 = 0% | |

| CPAP compliance, h | > 5 | 4 | −5.18 | −6.28 to −4.09 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 55% |

| ≤ 5 | 1 | 0.30 | −2.23 to 2.83 | p = 0.82; I2 = 0% | |

| Treatment duration, months | > 3 | 2 | −4.67 | −6.00 to −3.33 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 95% |

| ≤ 3 | 3 | −3.87 | −5.39 to −3.35 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 0% | |

| ESS score | ≥ 10 | 2 | −4.67 | −6.00 to −3.33 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 95% |

| < 10 | 3 | −3.87 | −5.39 to −2.35 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 0% | |

| Location | Europe | 3 | −3.87 | −5.39 to −2.35. | p < 0.00001; I2 = 0% |

| South America | 2 | −4.67 | −6.00 to −3.33 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 95% | |

| Study sample size | ≥ 25 | 3 | −2.53 | −3.89 to −1.16 | p = 0.0003; I2 = 72% |

| < 25 | 2 | −6.40 | −7.88 to −4.93 | p < 0.00001; I2 = 0% | |

DBP: diastolic blood pressure; SBP: systolic blood pressure; ABPM: ambulatory blood pressure monitoring; AHI: apnea-hypopnea index; BMI: body mass index; CPAP: continuous positive airway pressure; and ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale.

Subgroup analysis was used in order to explore potential factors leading to heterogeneity. With regard to changes in mean SBP (as assessed by 24-h ABPM) before and after CPAP therapy, no heterogeneity was found among the eight subgroups for an AHI ≥ 30; an AHI < 30; a baseline SBP/DBP > 145/85 mmHg; a baseline SBP/DBP < 145/85 mmHg; a BMI < 32 kg/m2; a CPAP treatment duration ≤ 3 months; a European location; or a study sample size ≥ 25 (Table 3). With regard to changes in mean DBP (as assessed by 24-h ABPM) before and after CPAP therapy, it was unlikely that an AHI ≥ 30, a BMI < 32 kg/m2, a CPAP treatment duration ≤ 3 months, an ESS score of < 10, a European location, or a study sample size of < 25 were the factors leading to heterogeneity (Table 4).

Meta-regression analysis showed that the ESS score, BMI, AHI, and age were not the factors leading to heterogeneity in mean SBP as assessed by 24-h ABPM. In contrast, there was a significant correlation between age and heterogeneity in mean DBP as assessed by 24-h ABPM (Table 5).

Table 5. Meta-regression of 24-h ambulatory blood pressure monitoring data.

| Explanatory variable | SBP | DBP | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of studies | p | No. of studies | p | ||

| ESS score | 6 | 0.74 | 5 | 0.44 | |

| BMI | 6 | 0.14 | 5 | 0.25 | |

| AHI | 6 | 0.22 | 5 | 0.70 | |

| Age | 6 | 0.47 | 5 | < 0.0001 | |

SBP: systolic blood pressure; DBP: diastolic blood pressure; ESS: Epworth Sleepiness Scale; BMI: body mass index; and AHI: apnea-hypopnea index.

A sensitivity analysis was performed by removing one study at a time from the combined effects model in order to observe mean changes in effects and determine whether there were any differences between the combined effects model and the original model regarding heterogeneity and CIs. One study was found to have led to heterogeneity. Different standard deviations and correlation coefficients were used, but the results were not significantly different. Funnel plots showed no significant publication bias (Begg’s test, p = 0.707; Egger’s test, p = 0.347).

DISCUSSION

OSA has been acknowledged as an independent risk factor for hypertension,11,19,20 being an adverse clinical factor that makes it impossible to control hypertension; in addition, OSA is the most common factor leading to resistant hypertension.21 Given that CPAP performs extraordinarily well in maintaining continuous positive pressure in the respiratory tract and that it can effectively reduce the AHI, cardiovascular morbidity, and cardiovascular mortality,22,23 it is currently one of the most effective ways to treat mild, moderate, and severe OSA. However, there is still controversy as to whether CPAP can effectively control blood pressure.

The present meta-analysis showed that, in patients with OSA and resistant hypertension undergoing CPAP treatment, mean SBP and DBP (as assessed by 24-h ABPM) decreased by 5.40 mmHg and 3.86 mmHg, respectively. In addition, mean nocturnal SBP and DBP decreased value after CPAP treatment (2.11 mmHg and 1.55 mmHg, respectively). Although mean daytime SBP and DBP decreased by 4.11 mmHg and 3.17 mmHg, respectively, after CPAP treatment, the combined effects of CPAP on SBP were statistically significant.

We found two observational studies showing the effects of CPAP treatment on blood pressure in patients with OSA and resistant hypertension. Dernaika et al.24 found that mean arterial pressure decreased by 5.6 mmHg after CPAP therapy (95% CI: 2.0-8.7; p = 0.03). Frenţ et al.25 suggested that long-term CPAP treatment can significantly control blood pressure in patients with OSA and resistant hypertension. The findings of the two aforementioned studies are consistent with those of the present study.

Durán-Cantolla et al.26 found that mean SBP and DBP (as assessed by 24-h ABPM) decreased by 2.1 mmHg (95% CI: 0.4-3.7; p = 0.01) and 1.3 mmHg (95% CI: 0.2-2.3; p = 0.02), respectively. Barbé et al.27 found that, after CPAP treatment, mean SBP and DBP decreased by 1.89 mmHg (95% CI: −0.11 to 3.9; p = 0.0654) and 2.19 mmHg (95% CI: 0.93-3.46; p = 0.0008), respectively. Therefore, it can be inferred that CPAP treatment has significant effects on the blood pressure of patients with OSA and resistant hypertension. Iftikhar et al.28 performed a meta-analysis of the effects of CPAP on blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension and OSA and reported that the risk of target organ damage and cardiovascular complications is higher in patients with resistant hypertension than in those with nonresistant hypertension, having found that CPAP treatment resulted in a favorable reduction in blood pressure in the former.

In the present study, we performed a combined effects analysis of mean daytime SBP/DBP, and the results of the heterogeneity test revealed a fairly large heterogeneity in daytime SBP/DBP across the studies. A sensitivity analysis revealed that the heterogeneity was mainly due to a study conducted by Pedrosa et al.,18 who concluded that CPAP treatment cannot significantly improve mean nocturnal SBP/DBP but can significantly improve mean daytime SBP/DBP. This finding is similar to those of the present meta-analysis.

We found two studies in which patients received CPAP treatment, conventional antihypertensive therapy, or a combination of the two. Lozano et al.15 found that the combined use of CPAP treatment and conventional antihypertensive therapy resulted in a more significant reduction in mean DBP (as assessed by 24-h ABPM) than did the use of conventional antihypertensive therapy alone. The results obtained by Litvin et al.29 are consistent with those obtained by Lozano et al.,15 the former group of authors having found that the combined use of CPAP and conventional antihypertensive therapy resulted in a more significant reduction in blood pressure. Therefore, patients with resistant hypertension should receive a combination of antihypertensive therapy and CPAP treatment, the effects of which are more significant than are those of antihypertensive therapy alone.

Our subgroup analysis revealed that the AHI, BMI, and ESS score were in the subgroup at risk of developing OSA and might be factors leading to heterogeneity. This is possibly due to the fact that the severity of OSA has an impact on the treatment of hypertension.

The present meta-analysis has some advantages over two earlier meta-analyses.28,30 First, all 6 studies included in our meta-analysis are RCTs. Second, we compiled a more comprehensive literature set, our results therefore being more convincing. Finally, in order to explore as many factors leading to heterogeneity as possible and provide a better explanation for the observed results, we adopted a variety of approaches to testing heterogeneity.

The present study has limitations. First, because of the limitations of our method of literature retrieval, it is possible that relevant studies were left out. Second, the number of RCTs included in our meta-analysis was rather small. Third, we did not control for confounding factors such as mean patient age, type of antihypertensive medication, degree of obesity, and genetic factors. Finally, the control groups were not homogeneous across studies. Despite these limitations, the results of the present study can be used in order to inform future studies.

In conclusion, CPAP treatment has an effect on patients with OSA and resistant hypertension. When treating patients with hypertension, physicians can prescribe CPAP treatment or CPAP treatment in combination with conventional antihypertensive therapy for those with concomitant OSA.

Study carried out in the Faculty of Information Engineering and Automation, Kunming University of Science and Technology, Kunming, China.

Financial support: None

REFERENCES

- 1.Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ Jr, Friedman N, Malhotra A, Patil SP, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(3):263-76 [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Epstein LJ, Kristo D, Strollo PJ, Jr, Friedman N, Malhotra A, Patil SP, et al. Clinical guideline for the evaluation, management and long-term care of obstructive sleep apnea in adults. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(3):263–276. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.2 Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(17):1230-5. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199304293281704 [DOI] [PubMed]; Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J, Weber S, Badr S. The occurrence of sleep-disordered breathing among middle-aged adults. N Engl J Med. 1993;328(17):1230–1235. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199304293281704. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199304293281704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.3 Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1046-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74229-X [DOI] [PubMed]; Marin JM, Carrizo SJ, Vicente E, Agusti AG. Long-term cardiovascular outcomes in men with obstructive sleep apnoea-hypopnoea with or without treatment with continuous positive airway pressure: an observational study. Lancet. 2005;365(9464):1046–1053. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)71141-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(05)74229-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.4 Parati G, Lombardi C, Hedner J, Bonsignore MR, Grote L, Tkacova R, et al. Position paper on the management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension: joint recommendations by the European Society of Hypertension, by the European Respiratory Society and by the members of European COST (COoperation in Scientific and Technological research) ACTION B26 on obstructive sleep apnea. J Hypertens. 2012;30(4):633-46. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e328350e53b [DOI] [PubMed]; Parati G, Lombardi C, Hedner J, Bonsignore MR, Grote L, Tkacova R, et al. Position paper on the management of patients with obstructive sleep apnea and hypertension: joint recommendations by the European Society of Hypertension, by the European Respiratory Society and by the members of European COST (COoperation in Scientific and Technological research) ACTION B26 on obstructive sleep apnea. J Hypertens. 2012;30(4):633–646. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e328350e53b. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e328350e53b [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.5 Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, Lichtman JH, Brass LM, Mohsenin V. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med . 2005;353(19):2034-41. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa043104 [DOI] [PubMed]; Yaggi HK, Concato J, Kernan WN, Lichtman JH, Brass LM, Mohsenin V. Obstructive sleep apnea as a risk factor for stroke and death. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(19):2034–2041. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa043104. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMoa043104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.6 Gottlieb DJ, Yenokyan G, Newman AB, O’Connor GT, Punjabi NM, Quan SF, et al. Prospective study of obstructive sleep apnea and incident coronary heart disease and heart failure: the sleep heart health study. Circulation. 2011;122(4):352-60. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.901801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Gottlieb DJ, Yenokyan G, Newman AB, O’Connor GT, Punjabi NM, Quan SF, et al. Prospective study of obstructive sleep apnea and incident coronary heart disease and heart failure: the sleep heart health study. Circulation. 2011;122(4):352–360. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.901801. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.109.901801 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.7 Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL Jr, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206-52. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2 [DOI] [PubMed]; Chobanian AV, Bakris GL, Black HR, Cushman WC, Green LA, Izzo JL, Jr, et al. Seventh report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Hypertension. 2003;42(6):1206–1252. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2. https://doi.org/10.1161/01.HYP.0000107251.49515.c2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.8 Calhoun DA, Jones D, Textor S, Goff DC, Murphy TP, Toto RD, et al. Resistant hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2008;117(25):e510-26. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.189141 [DOI] [PubMed]; Calhoun DA, Jones D, Textor S, Goff DC, Murphy TP, Toto RD, et al. Resistant hypertension: diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association Professional Education Committee of the Council for High Blood Pressure Research. Circulation. 2008;117(25):e510–e526. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.189141. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.189141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.9 Gonçalves SC, Martinez D, Gus M, de Abreu-Silva EO, Bertoluci C, Dutra I, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and resistant hypertension: a case-control study. Chest. 2007;132(6):1858-62. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.07-1170 [DOI] [PubMed]; Gonçalves SC, Martinez D, Gus M, de Abreu-Silva EO, Bertoluci C, Dutra I, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea and resistant hypertension: a case-control study. Chest. 2007;132(6):1858–1862. doi: 10.1378/chest.07-1170. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.07-1170 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.10 Calhoun DA, Nishizaka MK, Zaman MA, Harding SM. Aldosterone excretion among subjects with resistant hypertension and symptoms of sleep apnea. Chest. 2004;125(1):112-7. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.125.1.112 [DOI] [PubMed]; Calhoun DA, Nishizaka MK, Zaman MA, Harding SM. Aldosterone excretion among subjects with resistant hypertension and symptoms of sleep apnea. Chest. 2004;125(1):112–117. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.1.112. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.125.1.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.11 Lavie P, Herer P, Hoffstein V. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome as a risk factor for hypertension: population study. BMJ. 2000;320(7233):479-82. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7233.479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Lavie P, Herer P, Hoffstein V. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome as a risk factor for hypertension: population study. BMJ. 2000;320(7233):479–482. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7233.479. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.320.7233.479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.12 Khan A, Patel NK, O’Hearn DJ, Khan S. Resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. Int J Hypertens . 2013;2013:193010. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/193010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Khan A, Patel NK, O’Hearn DJ, Khan S. Resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. Int J Hypertens. 2013;2013:193010–193010. doi: 10.1155/2013/193010. https://doi.org/10.1155/2013/193010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.13 de Oliveira AC, Martinez D, Massierer D, Gus M, Gonçalves SC, Ghizzoni F, et al. The antihypertensive effect of positive airway pressure on resistant hypertension of patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized, double-blind, clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(3):345-7. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201403-0479LE [DOI] [PubMed]; de Oliveira AC, Martinez D, Massierer D, Gus M, Gonçalves SC, Ghizzoni F, et al. The antihypertensive effect of positive airway pressure on resistant hypertension of patients with obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized, double-blind, clinical trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2014;190(3):345–347. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201403-0479LE. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.201403-0479LE [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.14 Lloberes P, Sampol G, Espinel E, Segarra A, Ramon MA, Romero O, et al. A randomized controlled study of CPAP effect on plasma aldosterone concentration in patients with resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. J Hypertens . 2014;32(8):1650-7; discussion 1657. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000000238 [DOI] [PubMed]; Lloberes P, Sampol G, Espinel E, Segarra A, Ramon MA, Romero O, et al. A randomized controlled study of CPAP effect on plasma aldosterone concentration in patients with resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. J Hypertens. 2014;32(8):1650-7; discussion 1657. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000238. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000000238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.15 Lozano L, Tovar JL, Sampol G, Romero O, Jurado MJ, Segarra A, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure treatment in sleep apnea patients with resistant hypertension: a randomized, controlled trial. J Hypertens . 2010;28(10):2161-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833b9c63 [DOI] [PubMed]; Lozano L, Tovar JL, Sampol G, Romero O, Jurado MJ, Segarra A, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure treatment in sleep apnea patients with resistant hypertension: a randomized, controlled trial. J Hypertens. 2010;28(10):2161–2168. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833b9c63. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e32833b9c63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.16 Martínez-García M, Capote F, Campos-Rodríguez F, Lloberes P, Díaz de Atauri MJ, Somoza M, et al. Effect of CPAP on blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and resistant hypertension: the HIPARCO randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(22):2407-15. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281250 [DOI] [PubMed]; Martínez-García M, Capote F, Campos-Rodríguez F, Lloberes P, Díaz de Atauri MJ, Somoza M, et al. Effect of CPAP on blood pressure in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and resistant hypertension: the HIPARCO randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013;310(22):2407–2415. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281250. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2013.281250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.17 Muxfeldt ES, Margallo V, Costa LM, Guimarães G, Cavalcante AH, Azevedo JC, et al. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on clinic and ambulatory blood pressures in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and resistant hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. Hypertension . 2015;65(4):736-42 https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04852 [DOI] [PubMed]; Muxfeldt ES, Margallo V, Costa LM, Guimarães G, Cavalcante AH, Azevedo JC, et al. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure treatment on clinic and ambulatory blood pressures in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and resistant hypertension: a randomized controlled trial. Hypertension. 2015;65(4):736–742. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04852. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.18 Pedrosa RP, Drager LF, de Paula LK, Amaro AC, Bortolotto LA, Lorenzi-Filho G. Effects of OSA treatment on BP in patients with resistant hypertension: a randomized trial. Chest. 2013;144(5):1487-94. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-0085 [DOI] [PubMed]; Pedrosa RP, Drager LF, de Paula LK, Amaro AC, Bortolotto LA, Lorenzi-Filho G. Effects of OSA treatment on BP in patients with resistant hypertension: a randomized trial. Chest. 2013;144(5):1487–1494. doi: 10.1378/chest.13-0085. https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.13-0085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.19 Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. Prospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med . 2000;342(19):1378-84. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200005113421901 [DOI] [PubMed]; Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Skatrud J. ospective study of the association between sleep-disordered breathing and hypertension. N Engl J Med. 2000;342(19):1378–1384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005113421901. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM200005113421901 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.20 Marin JM, Agusti A, Villar I, Forner M, Nieto D, Carrizo SJ, et al. Association between treated and untreated obstructive sleep apnea and risk of hypertension. JAMA. 2012;307(20):2169-76. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.3418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Marin JM, Agusti A, Villar I, Forner M, Nieto D, Carrizo SJ, et al. Association between treated and untreated obstructive sleep apnea and risk of hypertension. JAMA. 2012;307(20):2169–2176. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.3418. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2012.3418 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.21 Oliveras A, Schmieder RE. Clinical situations associated with difficult-to-control hypertension. J Hypertens . 2013;31 Suppl 1:S3-8. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835d2af0 [DOI] [PubMed]; Oliveras A, Schmieder RE. Clinical situations associated with difficult-to-control hypertension. J Hypertens. 2013;31(Suppl 1):S3–S8. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835d2af0. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0b013e32835d2af0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.22 Mannarino MR, Di Filippo F, Pirro M. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23(7):586-93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2012.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed]; Mannarino MR, Di Filippo F, Pirro M. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Eur J Intern Med. 2012;23(7):586–593. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2012.05.013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejim.2012.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.23 Pedrosa RP, Drager LF, Gonzaga CC, Sousa MG, de Paula LK, Amaro AC, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea: the most common secondary cause of hypertension associated with resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;58(5):811-7. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.179788 [DOI] [PubMed]; Pedrosa RP, Drager LF, Gonzaga CC, Sousa MG, de Paula LK, Amaro AC, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea: the most common secondary cause of hypertension associated with resistant hypertension. Hypertension. 2011;58(5):811–817. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.179788. https://doi.org/10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.179788 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dernaika TA, Kinasewitz GT, Tawk MM. Effects of nocturnal continuous positive airway pressure therapy in patients with resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med . 2009;5(2):103-7. [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Dernaika TA, Kinasewitz GT, Tawk MM. Effects of nocturnal continuous positive airway pressure therapy in patients with resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5(2):103–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frenţ ŞM, Tudorache VM, Ardelean C, Mihăicuţă S. Long-term effects of nocturnal continuous positive airway pressure therapy in patients with resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. Pneumologia. 2014;63(4):204, 207-11. [PubMed]; Frenţ ŞM, Tudorache VM, Ardelean C, Mihăicuţă S. Long-term effects of nocturnal continuous positive airway pressure therapy in patients with resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea. Pneumologia. 2014;63(4):204, 207-11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.26 Durán-Cantolla J, Aizpuru F, Montserrat JM, Ballester E, Terán-Santos J, Aguirregomoscorta JI, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure as treatment for systemic hypertension in people with obstructive sleep apnoea: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c5991. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c5991 [DOI] [PubMed]; Durán-Cantolla J, Aizpuru F, Montserrat JM, Ballester E, Terán-Santos J, Aguirregomoscorta JI, et al. Continuous positive airway pressure as treatment for systemic hypertension in people with obstructive sleep apnoea: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c5991–c5991. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5991. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c5991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.27 Barbé F, Durán-Cantolla J, Capote F, de la Peña M, Chiner E, Masa JF, et al. Long-term effect of continuous positive airway pressure in hypertensive patients with sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med . 2010;181(7):718-26. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200901-0050OC [DOI] [PubMed]; Barbé F, Durán-Cantolla J, Capote F, de la Peña M, Chiner E, Masa JF, et al. Long-term effect of continuous positive airway pressure in hypertensive patients with sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2010;181(7):718–726. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200901-0050OC. https://doi.org/10.1164/rccm.200901-0050OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.28 Iftikhar IH, Valentine CW, Bittencourt LR, Cohen DL, Fedson AC, Gíslason T, et al. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure on blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. J Hypertens . 2014;32(12):2341-50; discussion 2350. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000000372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Iftikhar IH, Valentine CW, Bittencourt LR, Cohen DL, Fedson AC, Gíslason T, et al. Effects of continuous positive airway pressure on blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension and obstructive sleep apnea: a meta-analysis. J Hypertens. 2014;32(12):2341-50; discussion 2350. doi: 10.1097/HJH.0000000000000372. https://doi.org/10.1097/HJH.0000000000000372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Litvin AY, Sukmarova ZN, Elfimova EM, Aksenova AV, Galitsin PV, Rogoza AN, et al. Effects of CPAP on “vascular” risk factors in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and arterial hypertension. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2013;9:229-35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Litvin AY, Sukmarova ZN, Elfimova EM, Aksenova AV, Galitsin PV, Rogoza AN, et al. Effects of CPAP on “vascular” risk factors in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and arterial hypertension. Vasc Health Risk Manag. 2013;9:229–235. doi: 10.2147/VHRM.S40231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.30 Liu L, Cao Q, Guo Z, Dai Q. Continuous Positive Airway Pressure in Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Resistant Hypertension: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich). 2016;18(2):153-8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.12639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]; Liu L, Cao Q, Guo Z, Dai Q. Continuous Positive Airway Pressure in Patients With Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Resistant Hypertension: A Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. J Clin Hypertens (Greenwich) 2016;18(2):153–158. doi: 10.1111/jch.12639. https://doi.org/10.1111/jch.12639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]