Abstract

The development of influenza candidate vaccine viruses (CVVs) for pre-pandemic vaccine production represents a critical step in pandemic preparedness. The multiple subtypes and clades of avian or swine origin influenza viruses circulating world-wide at any one time necessitates the continuous generation of CVVs to provide an advanced starting point should a novel zoonotic virus cross the species barrier and cause a pandemic. Furthermore, the evolution and diversity of novel influenza viruses that cause zoonotic infections requires ongoing monitoring and surveillance, and, when a lack of antigenic match between circulating viruses and available CVVs is identified, the production of new CVVs. Pandemic guidelines developed by the WHO Global Influenza Program govern the design and preparation of reverse genetics-derived CVVs, which must undergo numerous safety and quality tests prior to human use. Confirmation of reassortant CVV attenuation of virulence in ferrets relative to wild-type virus represents one of these critical steps, yet there is a paucity of information available regarding the relative degree of attenuation achieved by WHO-recommended CVVs developed against novel viruses with pandemic potential. To better understand the degree of CVV attenuation in the ferret model, we examined the relative virulence of six A/Puerto Rico/8/1934-based CVVs encompassing five different influenza A subtypes (H2N3, H5N1, H5N2, H5N8, and H7N9) compared with the respective wild-type virus in ferrets. Despite varied virulence of wild-type viruses in the ferret, all CVVs examined showed reductions in morbidity and viral shedding in upper respiratory tract tissues. Furthermore, unlike the wild-type counterparts, none of the CVVs spread to extrapulmonary tissues during the acute phase of infection. While the magnitude of virus attenuation varied between virus subtypes, collectively we show the reliable and reproducible attenuation of CVVs that have the A/Puerto Rico/9/1934 backbone in a mammalian model.

Keywords: Pathogenicity, Influenza, Ferret, Vaccine viruses

1. Introduction

Influenza viruses cause seasonal epidemics and occasional pandemics in humans, with the severity of disease ranging from mild respiratory illness to acute respiratory disease and death. The continued circulation of influenza viruses in animal hosts represents a constant threat to human health should a virus jump the species barrier and cause human infection (Swayne, 2016); detection of novel influenza viruses in humans of avian and swine origin in recent years underscores that possibility (Uyeki et al., 2017). Vaccines represent the most effective public health tool to protect against influenza virus infection, but the prolonged lead time in vaccine virus development and manufacture make them difficult to employ in the early stages of a pandemic. In response, the WHO supports the generation of pre-pandemic candidate vaccine viruses (CVVs); CVVs designated by the WHO currently encompass seven virus subtypes.

The ferret is the preferred mammalian model for the study of influenza virus pathogenesis and transmission, due to similarities in lung physiology, distribution of influenza virus receptors throughout the respiratory tract, and numerous shared clinical signs and symptoms of influenza virus infection (Belser et al., 2011). As such, pathogenicity and transmissibility data obtained from ferrets is included in the Influenza Risk Assessment Tool (IRAT), a multi-attribute model that supports decision-making efforts regarding the selection of appropriate candidate vaccine viruses (Cox et al., 2014). The WHO recommends the demonstration of attenuation of CVVs in ferrets prior to distribution to vaccine manufacturers (WHO, 2005b). While there have been several isolated studies showing CVV attenuation in ferrets (Dong et al., 2009; Robertson et al., 2011; Webby et al., 2004), no comprehensive analysis of the relative degree of attenuation among numerous strains/subtypes of influenza viruses with pandemic potential has been reported. A better understanding of strain-specific variation compared with parameters uniformly present among all safety-tested viruses is critical when evaluating safety profiles of CVVs against influenza viruses with pandemic potential. This is of particular importance as demonstration that CVVs possess reduced pathogenicity is needed to Confirm the virus can be safely handled at the biosafety levels present during large-scale manufacturing of influenza vaccines. Similar to the current influenza vaccine production methods, the manufacturing process for CVVs includes virus concentration, inactivation, and purification procedures.

Here, we examined the mammalian virulence of six recently isolated wild-type influenza viruses from avian and swine reservoirs which have either been associated with human infection or are considered to pose a threat to human health, and determined the safety profile of each paired CVV using multiple parameters of the ferret model. Among ferrets inoculated with CVVs, we found strain-specific impacts of the HA and/or NA on morbidity and virus replication in the upper respiratory tract compared with the relevant wild-type virus, but high uniformity in the ablation of virus spread beyond the respiratory tract among all viruses analyzed. This study underscores the importance of aggregating safety-related in vivo data to demonstrate both the reliability and reproducibility of the A/Puerto Rico/8/1934 (PR/8) based CVV safety profile in mammals and as a resource when new potentially pandemic viruses emerge.

2. Methods

2.1. Viruses

Influenza A viruses included in the analyses in this study are listed in Table 1. All viruses were propagated in the allantoic cavity of 10–11 day old embryonated chicken eggs at 35–37 °C for 24–48 h as described previously (Maines et al., 2009, 2005). Pooled allantoic fluid was clarified by centrifugation and aliquots were stored at −80 °C until use. Stock titers were titered for 50% egg infectious dose (EID50) or plaque forming units (PFU) in MDCK cells as described previously (Reed and Muench, 1938; Zeng et al., 2007). All experiments with avian-origin viruses were conducted under biosafety level 2 or 3 containment, including enhancements required by the U.S. Department of Agriculture and the Division of Select Agents and Toxins/CDC (Chosewood et al., 2009).

Table 1.

Wild-type and CVVs used in this study.

| Virus | Abbreviation | Subtype | Virulence in ferrets | Reference | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Wt lossa | Tempa | ||||

| A/swine/Missouri/2124514/2006 | sw/MO/06 | H2N3 | 13.7 | 1.7 | (Pappas et al., 2015) |

| A/swine/Missouri/2124514/2006 (H2N3)-PR8-IDCDC-RG27 | RG27 | H2N3 | 5.9 | 1.3 | This study |

| A/Egypt/N03072/2010 | Egypt/10 | H5N1 | 9.1 | 1.8 | (Pearce et al., 2016) |

| A/Egypt/N03072/2010(H5N1)-PR8-IDCDC-RG29 | RG29 | H5N1 | 1.2 | 1.0 | This study |

| A/duck/Vietnam/NCVD-1206/2012 | dk/VN/12 | H5N1 | 6.5 | 1.9 | (Pearce et al., 2016) |

| A/Hubei/1/2010(H5N1)-PR8-IDCDC-RG30 | RG30 | H5N1 | 3.8 | 0.8 | This study |

| A/Anhui/1/2013 | Anhui/13 | H7N9 | 11.0 | 1.5 | (Belser et al., 2013) |

| A/Shanghai/2/2013 (H7N9)-PR8-IDCDC-RG32A | RG32A | H7N9 | 1.5 | 1.5 | (Ridenour et al., 2015a) |

| A/gyrfalcon/Washington/41088-6/2014 | gyr/WA/14 | H5N8 | 3.5 | 1.3 | (Pulit-Penaloza et al., 2015) |

| A/gyrfalcon/Washington/41088-6/2014(H5N8)-PR8-IDCDC-RG43A | RG43A | H5N8 | 1.2 | 0.2 | This study |

| A/northern pintail/Washington/40964/14 | np/WA/14 | H5N2 | 0.5 | 1.4 | (Pulit-Penaloza et al., 2015) |

| IDCDC-RG47B (A/gyrfalcon/Washington/41088-6/2014 (H5N8)-PR8-IDCDC-RG43A-like HA, A/turkey/Minnesota/15-014110-1/2015 NA) × PR8 | RG47B | H5N2 | 0.3 | 1.2 | This study |

Mean maximum weight loss (expressed as percentage) and rise in pre-inoculation temperature (reported as °C above baseline) collected during the first 9 days p.i.

Reassortant vaccine candidate viruses (GLP candidate vaccine viruses) were generated by transfecting reverse genetics plasmids encoding the HA and NA surface gene segments of the virus of interest along with reverse genetics constructs encoding the PB2, PB1, PA, NP, M, and NS gene segments of PR/8 influenza virus (plasmids described in Ridenour et al. (2015a)) into certified Vero cells (O’Neill and Donis, 2009). HA and NA Genbank accession numbers: EU258939, EU258937 (RG27); JN401974, CY062485 (RG29); CY103897, CY098760 (RG30); KF021597.1, KF021599.1 (RG32A); KP307984.1, KP307986.1 (RG43A). In some cases, HA and NA genes may be synthetically produced based on genetic sequence information (Dormitzer, 2015). For hemagglutinin gene segments of highly pathogenic avian H5N1 influenza viruses, constructs were generated that delete the region coding for polybasic amino acids juxtaposed to the HA1/HA2 protease cleavage site to create a mono-basic amino acid cleavage site characteristic of low pathogenic viruses (Dong et al., 2009; O’Neill and Donis, 2009; Subbarao et al., 2003; World Health Organization Global Influenza Program Surveillance, 2005). Automated sequencing was performed using an Applied Biosystems 3130 genetic analyzer to Confirm both a matching genetic sequence with the parental viruses, and to verify the lack of a polybasic sequence at the HA cleavage site. Sterility testing of each CVV for bacterial (aerobic, anaerobic) and fungal contaminates was performed (WHO, 2005b).

2.2. Ferret experiments

Male Fitch ferrets (Triple F Farms, Sayre, PA), 6–12 months of age and serologically negative by hemagglutination inhibition assay to currently circulating influenza viruses, were used in this study. Animal research was conducted under the guidance of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee in an Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International-accredited animal facility. Ferrets were housed for the duration of each experiment in a Duo-Flo BioClean environmental enclosure (Lab Products, Seaford, DE). For each virus tested, 6 ferrets were intranasally (i.n.) inoculated with 106 PFU or EID50 of virus diluted in PBS in a 1 ml volume. Wild-type ferret pathotyping data was published previously as indicated by the references provided in Table 1. In all experiments, three ferrets were monitored daily for clinical signs and symptoms of infection for 14 days, with nasal wash (NW) samples collected on alternate days post-inoculation (p.i.) for virus titration in eggs or cells as previously described (Maines et al., 2005). Any ferret that lost > 25% of its pre-inoculation body weight or displayed signs of neurological dysfunction was euthanized. Three additional ferrets were euthanized day 3 p.i. for collection and titration of systemic tissues as previously described (Maines et al., 2005). Statistical significance of NW viral titers between CVV and wild-type strains was determined by Student’s t-test.

3. Results

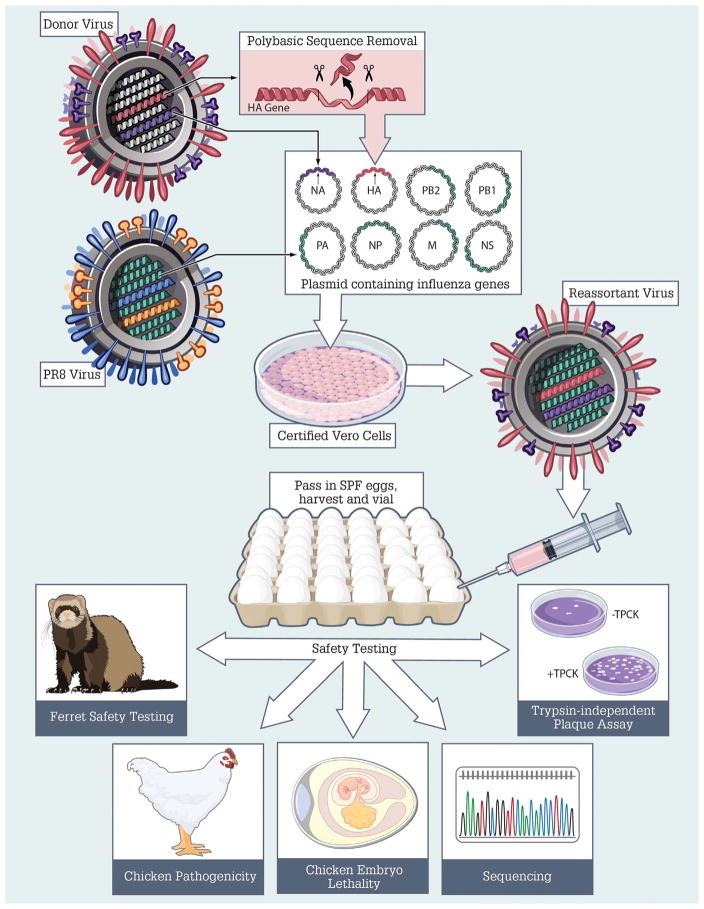

3.1. Generation and validation of candidate vaccine viruses

The generation of reassortant viruses was performed according to WHO guidance for development of vaccine reference viruses (WHO, 2005b) (Fig. 1). Briefly, the hemagglutinin (HA) and neuraminidase (NA) genes were amplified from viral RNA either extracted from the donor virus, or generated synthetically, using Reverse Transcription-Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR). Amplified PCR products for HA and NA genes were ligated into the transcription plasmid, Confirmed by sequence analysis, and co-transfected together with the six internal gene plasmids from PR/8, to produce recombinant virus. Recombinant virus containing HA and NA from the donor virus on a PR/8 backbone were propagated in specific pathogen free (SPF) 10–11 day-old embryonated chicken eggs for at least two passages.

Fig. 1. Generation, validation, and safety testing of candidate vaccine viruses.

Influenza virus reassortant candidate vaccine viruses (CVVs) were created according to WHO guidance for development of vaccine reference viruses (WHO, 2005b). Methodology is described in detail in Sections 2 and 3.

Following propagation in eggs, all candidate vaccine viruses underwent further testing to assess phenotype and pathogenicity. This included chicken embryo lethality testing to verify reduced pathogenicity of reassortant viruses, and for viruses derived from an HA donor virus with a highly pathogenic sequence at the HA cleavage site, chicken pathogenicity testing and a trypsin-dependent plaque assay (OIE, 2015). These assays verified reduced pathogenicity of reassortant viruses (data not shown). Upon successful completion of all safety and quality testing, viruses are eligible to become a candidate vaccine virus (CVV), and may be designated as such by WHO (2016a, 2017).

3.2. Virulence of candidate vaccine viruses in ferrets

According to WHO recommendations, CVV attenuation must be demonstrated in the ferret model, including reductions in viral titer of the CVV compared with the wild-type strain in respiratory tract tissues and an absence of extrapulmonary spread (WHO, 2005a, 2013), as ferrets typically function as a reliable indicator of influenza virus virulence in humans (Belser et al., 2011; Smith and Sweet, 1988). To examine the degree of attenuation that the HA modifications and PR/8 backbone typically provide, we compared the relative virulence of each CVV to the wild-type parental virus or a genetically related wild-type strain. The wild-type viruses included in this study possessed a range of virulence in ferrets: the H2N3, H5N1, and H7N9 viruses exhibited moderate virulence (mean maximum weight loss 6.5–13.7%, with one dk/VN/12 virus-inoculated ferret succumbing to disease day 7 p.i.), while the HPAI H5N2 and H5N8 viruses exhibited low virulence (mean maximum weight loss < 4%) (Table 1). Mean maximum rises in body temperature ranging from 1.3 to 1.9 °C above baseline pre-inoculation readings were observed among wild-type viruses independent of virulence characterization.

Severe disease and lethality were not detected in any ferret inoculated with a CVV. All CVVs exhibited reductions in mean maximum weight loss in ferrets compared to wild-type virus infection, with the magnitude of weight loss reduction dependent on the severity of the wild-type virus. H2N3, H5N1 (Egypt), and H7N9 CVVs exhibited the most pronounced reduction in morbidity in ferrets (ranging from 7.8% to 9.5% reductions in weight loss from pre-inoculation body weight compared with wild-type infection), while H5N1 (Hubei), H5N2, and H5N8 viruses exhibited less overall effect on morbidity (0.2–2.7% reductions in weight loss from pre-inoculation body weight compared with wild-type infection) (Table 1). All ferrets inoculated with H2 or H5 subtype CVVs exhibited reductions in peak mean rise in body temperature post-inoculation compared with wild-type virus infection, ranging from modest reductions (0.2–0.4 °C reductions for H2N3 and H5N2 subtype viruses) to more pronounced reductions (0.8–1.1 °C reductions for H5N1 and H5N8 subtype viruses). These data indicate that the relative virulence of CVV strains must be compared with wild-type strains to fully appreciate the degree of attenuation achieved by the vaccine strain.

3.3. Attenuated replication of CVVs in the ferret upper respiratory tract

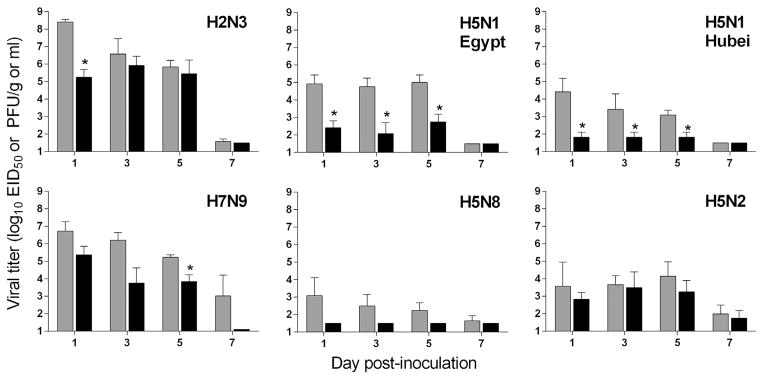

The reverse genetics PR/8 virus does not cause severe disease in ferrets, but is capable of moderate replication in the ferret upper respiratory tract through day 5 p.i. (Dong et al., 2009). To determine the kinetics and magnitude of CVV replication in the ferret upper respiratory tract, nasal wash (NW) samples from ferrets inoculated with wild-type or CVVs were collected on alternate days 1–9 p.i. and titered for the presence of infectious virus (Fig. 2). In agreement with morbidity measurements (Table 1), the wild-type viruses in this study exhibited a range of titers, with the H2N3 and H7N9 wild-type viruses replicating to highest titer in this sample (reaching peak mean titers > 106 EID50/ml or PFU/ml day 1 p.i.) and the H5N8 virus replicating with least efficiency (peak mean titers < 103.1 EID50/ml day 1 p.i.). Independent of peak NW titers reached in this sample, virus was cleared by day 9 p.i. in all virus-inoculated ferrets.

Fig. 2. Mean nasal wash viral titer of wild-type and CVVs in ferrets.

Three ferrets per group were inoculated with 106 PFU or EID50 of virus (grey bars, wild-type virus; black bars, CVV). Nasal washes were collected on alternate days p.i. Mean titers for each group are shown as log10 EID50/ml + standard deviation (SD) with the exception of H7N9 viruses which are shown as log10 PFU/ml. The limit of detection was 1.5 log10 EID50/ml or 1 log10 PFU/ml. *, p < 0.05 between wild-type and CVV groups.

When compared with the wild-type viruses, all CVVs exhibited reductions in virus shedding in NW samples. The greatest attenuation was observed among H5N1 CVVs compared with wild-type counterpart viruses, which had significantly reduced titers detected on days 1–5 p.i. in NW samples among all CVV strains (p < 0.05, Fig. 2). H2N3 and H7N9 expressing CVVs also had significantly reduced viral titers in NW samples, reaching peak fold reductions in viral load of > 1000-fold and > 100-fold on days 1 and 5 p.i., respectively. The H5N8 CVV replicated so inefficiently that it was not detected (limit of detection 1.5 log10 EID50/ml) in NW specimens of any inoculated ferret during the acute phase of infection. Reductions in viral titer in NW samples between wild-type and CVV for H5N2 and H5N8 subtypes were not statistically significant, likely due to poor fitness among wild-type strains in ferrets. With the exception of H2N3 virus, all other CVVs tested further possessed reduced viral loads in ferret nasal turbinates collected day 3 p.i., providing an additional measure of reduction of virus replication in the nasal cavity (Fig. 3). Collectively, reduced viral titers were present in the upper respiratory tract following infection with CVVs compared with wild-type viruses, but the relative degree of viral load reduction was subtype-specific and likely influenced by the robustness of replication of the wild-type strain.

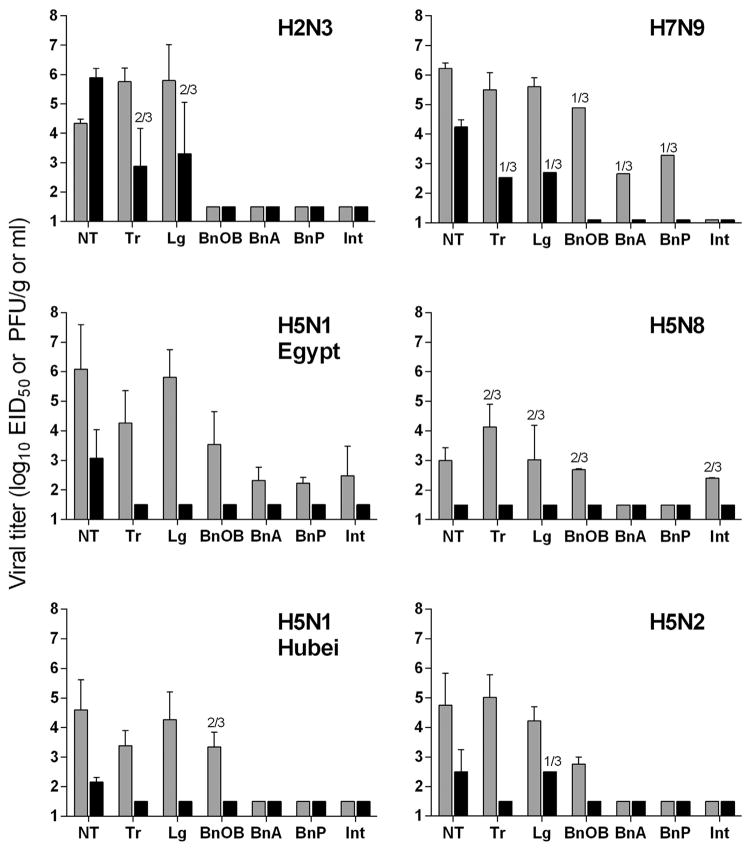

Fig. 3. Systemic replication of wild-type and CVVs in ferrets.

Three ferrets per group were inoculated with 106 PFU or EID50 of virus (grey bars, wild-type virus; black bars, CVV), and tissues were collected 3 days p.i. for virus titration. Mean titers for each group are shown as log10 EID50/g or ml + SD with the exception of H7N9 viruses which are shown as log10 PFU/g or ml. All titers are reffective of virus detection in 3/3 ferrets unless specified otherwise. NT, nasal turbinates; Tr, trachea; Lg, lung; BnOB, olfactory bulb; BnA, anterior brain; BnP, posterior brain; Int, intestine (pooled). The limit of detection was 1.5 log10 EID50/g or ml or 1 log10 PFU/g or ml (all samples are expressed per g with the exception of NT, which is expressed per ml).

3.4. Ablated systemic spread of CVVs in ferrets

Unlike human seasonal influenza viruses which are typically restricted to replication in the ferret upper respiratory tract, influenza viruses which are associated with severe disease in ferrets are typically detected at high titer in the lower respiratory tract and recovered from extrapulmonary tissues, including the brain (Maines et al., 2005). In agreement with most zoonotic influenza viruses examined in the ferret model, all wild-type influenza viruses in this study were detected in the trachea and lung day 3 p.i. (Fig. 3). Furthermore, all H5 and H7 wild-type influenza viruses were detected in the olfactory bulb of the brain, and two viruses (Egypt H5N1 and H7N9) were detected in both anterior and posterior regions of the brain at this time p.i. Viral isolation from intestinal tissue was detected only with HPAI H5N1 (Egypt) and H5N8 viruses (Pearce et al., 2016; Pulit-Penaloza et al., 2015).

In contrast with wild-type strains, CVVs were detected more sporadically and to lower titer than homologous wild-type virus in the lower respiratory tract tissues (Fig. 3). Virus was recovered in the trachea of 3/6 CVV-inoculated ferrets (H2N3, H7N9) and the lung of 4/9 CVV-inoculated ferrets (H2N3, H7N9, H5N2), but in all instances both the mean titer and incidence of detection were reduced compared with the wild-type counterpart. No infectious virus was detected in the olfactory bulb, brain, or intestine of any CVV-inoculated ferret. These findings indicate that CVVs were attenuated in both their dissemination to lower respiratory tract tissues and as well as to extrapulmonary tissues in the ferret model on day 3 p.i.

4. Discussion

While circulating seasonal human influenza A viruses are restricted to a few subtypes (Azziz-Baumgartner et al., 2015), there are multiple subtypes of zoonotic influenza viruses that have extensive strain-specific variation circulating throughout the world (WHO, 2016b). These viruses can sometimes adapt between hosts, accelerating the acquisition of mutations that can potentially lead to wider within host transmission (Ridenour et al., 2015b). The development of CVVs against zoonotic viruses and subsequent vaccine products for the assessment of vaccine immunogenicity, optimal vaccination strategies and/or stockpiling are important pandemic preparedness efforts (WHO, 2006). However, the strain-specific phenotypic/genotypic variation of these viruses requires the development of a specific vaccine against an actual pandemic virus. Despite these challenges, the creation of a bank of CVVs antigenically matched to the currently circulating potentially pandemic strains enables a rapid and more informed response for emergency use.

The attenuation of the pathogenicity of the potential CVV must be shown before its inclusion in any list of WHO candidate vaccine viruses for use in a pandemic (WHO-GISN, 2011). Attenuation of pathogenicity of the candidate vaccine virus in both chicken embryos and 4–7 week old chickens are required indicators for vaccine virus environmental biosafety. Additionally, chicken pathogenicity testing is performed on all viruses that are derived from highly-pathogenic avian influenza parental strains. Sequencing of both wild-type and candidate vaccine viruses were performed to verify the lack of a highly pathogenic genotype in the candidate vaccine virus, and to Confirm an absence of mutations in the surface genes that might lead to a loss of antigenicity. Parallel work that can occur further downstream of the safety testing of the CVV involves analysis of HA yield and further improvements in growth characteristics necessary for large-scale expansion and stockpiling. Specifically, alternate PR/8 internal gene segments with different characteristics can be combined with the HA and NA from the CVV in order to optimize yield through different gene segment interactions (Johnson et al., 2015). In addition, further passaging in eggs is another approach to elicit egg-adapted changes that can improve yield while maintaining antigenicity similarity to parental virus (Ridenour et al., 2015a).

A few studies have reported the attenuation of CVVs in the ferret model in comparison to wild-type strains, but rarely have provided specific data regarding the degree of attenuation (Dong et al., 2009; Robertson et al., 2011; Webby et al., 2004). Our results highlight that the relative degree of attenuation of CVVs is strain-specific, and dependent on the properties of the parental virus. CVVs exhibited varied reductions in morbidity (as measured by weight loss), fever, magnitude and duration of virus shedding in upper respiratory tract tissues, as well as presence of detectable virus in lower respiratory tract tissues. While all CVVs included in this study possessed an attenuated phenotype compared with wild-type viruses in the ferret model, the alignment of numerous CVVs of different virus subtypes and lineages included here underscores the need to assess numerous parameters when determining an attenuated phenotype in a mammalian model. Furthermore, a poorly studied component of virus attenuation is reduction in transmissibility. Although determination of transmission efficiency is not required to confirm CVV attenuation (WHO, 2005b), we performed a transmission experiment in ferrets for one CVV, RG27 (H2N3) and found that the H2N3 CVV failed to transmit by respiratory droplets, whereas the wild-type (sw/MO/06) virus transmitted to 66% of naïve contacts ((Pappas et al., 2015) and data not shown).

In all CVVs examined in this study, the degree of attenuation in the ferret model was relative to the virulence of the wild-type strain, again illustrating the impact the HA and NA play in pathogenesis. In ferrets, H2N3 and H7N9 CVVs exhibited peak mean viral titers in nasal wash samples > 105 EID50 or PFU/ml, which is higher than any wild-type H5N1 strain included in this study; both H2N3 and H7N9 viruses possess an enhanced capacity to bind to α2–6 linked sialic acid receptors, which may confer a fitness advantage in the ferret model compared with avian-like H5N1 viruses (Fig. 2) (Pappas et al., 2015; Xiong et al., 2013). Nonetheless, H2N3 and H7N9 CVVs showed reduced virulence compared with wild-type strains, as demonstrated by diminished morbidity and reduced viral replication in the upper and lower respiratory tract. Similarly, the range of peak viral titers throughout the respiratory tract of ferrets inoculated with H5 subtype viruses, and the absence or presence of extrapulmonary virus spread among H5-inoculated ferrets, aids in the interpretation of attenuation observed among HPAI H5 subtype CVVs. Collectively, these results underscore the value of paired wild-type control pathotyping data when assessing CVV attenuation while simultaneously demonstrating the achievement of virus attenuation of CVV strains regardless of wild-type strain virulence in this mammalian model.

Ferrets are studied to assess the attenuation of influenza countermeasures relative to wild-type virus infection. In addition to CVVs for inactivated vaccines, ferrets are used to assess the safety of live attenuated influenza vaccine viruses (Shcherbik et al., 2015; Shen et al., 2016; Zhou et al., 2010), and examination of the protective effects of prior infection with heterologous viruses (Houser et al., 2013), among other vaccine approaches against both influenza and other viruses of public health concern (Enkirch and von Messling, 2015). These studies also vary in the degree of attenuation afforded but collectively highlight the utility of ferrets in evaluating the pre-clinical effectiveness of influenza countermeasures to mitigate clinical signs and symptoms of infection, magnitude and dissemination of virus replication, and in some instances, transmissibility. The continued development of ferret-specific reagents will improve our understanding of vaccine immunogenicity in this model, and will further enable a role for ferrets in the continued development of universal influenza vaccines (Margine and Krammer, 2014).

The creation of CVVs represents a pillar of public health pandemic preparedness. The WHO guidelines ensure a reliably safe, attenuated, non-pathogenic virus strain appropriate for large-scale manufacturing facilities. Our results further reinforce the reliability and reproducibility of reverse-genetics CVVs engineered as PR/8-based 6:2 reassortants with a range of viruses with pandemic potential. This study addressed the attenuation of CVVs developed against multiple zoonotic influenza viruses which pose a threat to human health. However, there remains a need to assess the ability of vaccines developed using these CVVs, including stockpiled vaccines, to elicit protective antibodies against continually evolving and increasingly antigenically diverse influenza viruses with pandemic potential (Pearce et al., 2011).

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Jennifer Oosthuizen for graphical assistance. The findings and conclusions are those of the authors and do not necessarily reffect the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

References

- Azziz-Baumgartner E, Garten RJ, Palekar R, Cerpa M, Mirza S, Ropero AM, Palomeque FS, Moen A, Bresee J, Shaw M, Widdowson MA. Determination of predominance of influenza virus strains in the Americas. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:1209–1212. doi: 10.3201/eid2107.140788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belser JA, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. The ferret as a model organism to study influenza A virus infection. Dis Model Mech. 2011;4:575–579. doi: 10.1242/dmm.007823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belser JA, Gustin KM, Pearce MB, Maines TR, Zeng H, Pappas C, Sun X, Carney PJ, Villanueva JM, Stevens J, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. Pathogenesis and transmission of avian influenza A (H7N9) virus in ferrets and mice. Nature. 2013;501:556–559. doi: 10.1038/nature12391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chosewood LC, Wilson DE Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.), National Institutes of Health (U.S.) Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories. 5. U.S. Dept. of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institutes of Health; Washington, D.C: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cox NJ, Trock SC, Burke SA. Pandemic preparedness and the Influenza Risk Assessment Tool (IRAT) Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2014;385:119–136. doi: 10.1007/82_2014_419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong J, Matsuoka Y, Maines TR, Swayne DE, O’Neill E, Davis CT, Van-Hoven N, Balish A, Yu HJ, Katz JM, Klimov A, Cox N, Li DX, Wang Y, Guo YJ, Yang WZ, Donis RO, Shu YL. Development of a new candidate H5N1 avian influenza virus for pre-pandemic vaccine production. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2009;3:287–295. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-2659.2009.00104.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dormitzer PR. Rapid production of synthetic influenza vaccines. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2015;386:237–273. doi: 10.1007/82_2014_399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Enkirch T, von Messling V. Ferret models of viral pathogenesis. Virology. 2015;479–480:259–270. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Houser KV, Pearce MB, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. Impact of prior seasonal H3N2 influenza vaccination or infection on protection and transmission of emerging variants of influenza A(H3N2)v virus in ferrets. J Virol. 2013;87:13480–13489. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02434-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson A, Chen LM, Winne E, Santana W, Metcalfe MG, Mateu-Petit G, Ridenour C, Hossain MJ, Villanueva J, Zaki SR, Williams TL, Cox NJ, Barr JR, Donis RO. Identification of influenza A/PR/8/34 donor viruses imparting high hemagglutinin yields to candidate vaccine viruses in eggs. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0128982. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0128982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maines TR, Lu XH, Erb SM, Edwards L, Guarner J, Greer PW, Nguyen DC, Szretter KJ, Chen LM, Thawatsupha P, Chittaganpitch M, Waicharoen S, Nguyen DT, Nguyen T, Nguyen HH, Kim JH, Hoang LT, Kang C, Phuong LS, Lim W, Zaki S, Donis RO, Cox NJ, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. Avian influenza (H5N1) viruses isolated from humans in Asia in 2004 exhibit increased virulence in mammals. J Virol. 2005;79:11788–11800. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.18.11788-11800.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maines TR, Jayaraman A, Belser JA, Wadford DA, Pappas C, Zeng H, Gustin KM, Pearce MB, Viswanathan K, Shriver ZH, Raman R, Cox NJ, Sasisekharan R, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. Transmission and pathogenesis of swine-origin 2009 A(H1N1) influenza viruses in ferrets and mice. Science. 2009;325:484–487. doi: 10.1126/science.1177238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Margine I, Krammer F. Animal models for influenza viruses: implications for universal vaccine development. Pathogens. 2014;3:845–874. doi: 10.3390/pathogens3040845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- OIE. Manual of Diagnostic Tests and Vaccines for Terrestrial Animals 2015 [Google Scholar]

- O’Neill E, Donis RO. Generation and characterization of candidate vaccine viruses for prepandemic influenza vaccines. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2009;333:83–108. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-92165-3_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pappas C, Yang H, Carney PJ, Pearce MB, Katz JM, Stevens J, Tumpey TM. Assessment of transmission, pathogenesis and adaptation of H2 subtype influenza viruses in ferrets. Virology. 2015;477:61–71. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce MB, Belser JA, Houser KV, Katz JM, Tumpey TM. Efficacy of seasonal live attenuated influenza vaccine against virus replication and transmission of a pandemic 2009 H1N1 virus in ferrets. Vaccine. 2011;29:2887–2894. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pearce MB, Pappas C, Gustin KM, Davis CT, Pantin-Jackwood MJ, Swayne DE, Maines TR, Belser JA, Tumpey TM. Enhanced virulence of clade 2.3.2.1 highly pathogenic avian influenza A H5N1 viruses in ferrets. Virology. 2016;502:114–122. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.12.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pulit-Penaloza JA, Sun X, Creager HM, Zeng H, Belser JA, Maines TR, Tumpey TM. Pathogenesis and transmission of novel highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N2 and H5N8 viruses in ferrets and mice. J Virol. 2015;89:10286–10293. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01438-15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reed LJ, Muench HA. A simple method of estimating fifty per cent endpoints. Am J Hyg. 1938;27:493–497. [Google Scholar]

- Ridenour C, Johnson A, Winne E, Hossain J, Mateu-Petit G, Balish A, Santana W, Kim T, Davis C, Cox NJ, Barr JR, Donis RO, Villanueva J, Williams TL, Chen LM. Development of influenza A(H7N9) candidate vaccine viruses with improved hemagglutinin antigen yield in eggs. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2015a;9:263–270. doi: 10.1111/irv.12322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ridenour C, Williams SM, Jones L, Tompkins SM, Tripp RA, Mundt E. Serial passage in ducks of a low-pathogenic avian influenza virus isolated from a chicken reveals a high mutation rate in the hemagglutinin that is likely due to selection in the host. Arch Virol. 2015b;160:2455–2470. doi: 10.1007/s00705-015-2504-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson JS, Nicolson C, Harvey R, Johnson R, Major D, Guilfoyle K, Roseby S, Newman R, Collin R, Wallis C, Engelhardt OG, Wood JM, Le J, Manojkumar R, Pokorny BA, Silverman J, Devis R, Bucher D, Verity E, Agius C, Camuglia S, Ong C, Rockman S, Curtis A, Schoofs P, Zoueva O, Xie H, Li X, Lin Z, Ye Z, Chen LM, O’Neill E, Balish A, Lipatov AS, Guo Z, Isakova I, Davis CT, Rivailler P, Gustin KM, Belser JA, Maines TR, Tumpey TM, Xu X, Katz JM, Klimov A, Cox NJ, Donis RO. The development of vaccine viruses against pandemic A(H1N1) influenza. Vaccine. 2011;29:1836–1843. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.12.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shcherbik S, Pearce N, Balish A, Jones J, Thor S, Davis CT, Pearce M, Tumpey T, Cureton D, Chen LM, Villanueva J, Bousse TL. Generation and characterization of live attenuated influenza A(H7N9) candidate vaccine virus based on russian donor of attenuation. PLoS One. 2015;10:e0138951. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0138951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen Z, Bowen RA, Ge P, Yu J, Shen Y, Kong W, Jiang C, Wu J, Zhu C, Xu Y, Wei W, Rudenko L, Kiseleva I, Xu F. Evaluation of a candidate live attenuated influenza vaccine prepared in Changchun BCHT (China) for safety and efficacy in ferrets. Vaccine. 2016;34:5953–5958. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2016.09.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith H, Sweet C. Lessons for human influenza from pathogenicity studies with ferrets. Rev Infect Dis. 1988;10:56–75. doi: 10.1093/clinids/10.1.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subbarao K, Chen H, Swayne D, Mingay L, Fodor E, Brownlee G, Xu X, Lu X, Katz J, Cox N, Matsuoka Y. Evaluation of a genetically modified reassortant H5N1 influenza A virus vaccine candidate generated by plasmid-based reverse genetics. Virology. 2003;305:192–200. doi: 10.1006/viro.2002.1742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swayne DE. Animal Influenza. 2. Wiley-Blackwell; Ames, Iowa: 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Uyeki TM, Katz JM, Jernigan DB. Novel influenza A viruses and pandemic threats. Lancet. 2017;389:2172–2174. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)31274-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webby RJ, Perez DR, Coleman JS, Guan Y, Knight JH, Govorkova EA, McClain-Moss LR, Peiris JS, Rehg JE, Tuomanen EI, Webster RG. Responsiveness to a pandemic alert: use of reverse genetics for rapid development of influenza vaccines. Lancet. 2004;363:1099–1103. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15892-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Expert Committee on Biological Standardization, Fifty-sixth Report. WHO; Geneva: 2005a. Biosafety Risk Assessment and Guidelines for the Production and Quality Control of Human Influenza Pandemic Vaccines. (p. Annex 5) [Google Scholar]

- WHO. WHO Guidance on Development of Influenza Vaccine Reference Viruses by Reverse Genetics 2005b [Google Scholar]

- WHO; Services, W.D.P, editor. Global Pandemic Influenza Action Plan to Increase Vaccine Supply. Geneva, Switzerland: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Update of WHO Biosafety Risk Assessment and Guidelines for the Production and Quality Control of Human Influenza Vaccines Against Avian Influenza A(H7N9) Virus. WHO; Geneva: 2013. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Available Candidate Vaccine Viruses and Potency Testing Reagents 2016a [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Zoonotic influenza viruses: antigenic and genetic characteristics and development of candidate vaccine viruses for pandemic preparedness. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2016b;91:485–499. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Antigenic and Genetic Characteristics of Zoonotic Influenza Viruses and Development of Candidate Vaccine Viruses for Pandemic Preparedness 2017 [Google Scholar]

- Press W, editor. WHO-GISN. Manual for the Laboratory Diagnosis and Virological Surveillance of Influenza. Geneva, Switzerland: 2011. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization, Global Influenza Program Surveillance, N. Evolution of H5N1 avian influenza viruses in Asia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:1515–1521. doi: 10.3201/eid1110.050644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiong X, Martin SR, Haire LF, Wharton SA, Daniels RS, Bennett MS, McCauley JW, Collins PJ, Walker PA, Skehel JJ, Gamblin SJ. Receptor binding by an H7N9 influenza virus from humans. Nature. 2013;499:496–499. doi: 10.1038/nature12372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeng H, Goldsmith C, Thawatsupha P, Chittaganpitch M, Waicharoen S, Zaki S, Tumpey TM, Katz JM. Highly pathogenic avian influenza H5N1 viruses elicit an attenuated type i interferon response in polarized human bronchial epithelial cells. J Virol. 2007;81:12439–12449. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01134-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou B, Li Y, Belser JA, Pearce MB, Schmolke M, Subba AX, Shi Z, Zaki SR, Blau DM, Garcia-Sastre A, Tumpey TM, Wentworth DE. NS-based live attenuated H1N1 pandemic vaccines protect mice and ferrets. Vaccine. 2010;28:8015–8025. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2010.08.106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]