Abstract

Background:

Giant cell tumor (GCT) of the bone is known for its locally aggressive behavior and tendency to recur. It is an admixture of rounded or spindle-shaped mononuclear neoplastic stromal cells and multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells with their proportionate dispersion among the former. Zoledronic acid (a bisphosphonate) is being used in various cancers such as myelomas and metastasis, for osteoporosis with an aim to reduce the resorption of bone, and as an adjuvant treatment for the management of GCT of bone for reduction of local recurrence. We have carried out a prospective comparative study to assess the effect of intravenous infusion of zoledronic acid on histopathology and recurrence of GCT of bone.

Materials and Methods:

The study was carried out in the biopsy proven GCTs in 37 patients; 15 males and 22 females, in the age range from 17 to 55 years. They were treated with extended curettage. Of these 37 patients, 18 were given three doses of 4 mg zoledronic acid infusion at 3-week intervals and extended curettage was performed 2 weeks after the last infusion whereas the other 19 were treated with extended curettage without zoledronic infusion. The post infusion histopathology of the curetted material was compared with the histopathology of initial biopsy. All the patients were evaluated at 3-month intervals for the first 2 years and then six monthly thereafter, for local recurrence and functional outcome of limb using the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) score.

Results:

In postzoledronic infusion cases, the histopathology of samples showed abnormal stromal cells secreting matrix leading to fibrosis and calcification. The type of fibrosis and calcification was different from pathological calcification and fibrosis what is usually observed. There was a good marginalization and solidification of tumors which made surgical curettage easier in six cases in the study group. There was noticeable reduction in the number of giant cells and alteration in morphology of stromal cells to the fibroblastic-fibrocytic series type in comparison to preinfusion histopathology. Recurrence occurred in one case out of 18 patients in infusion group whereas in four cases among 19 patients in control group. The functional results were assessed, and the overall average MSTS score was 27.50 (range 24–30) and 27.00 (range 23.50–30) in the study and control groups, respectively.

Conclusions:

We observed that bisphosphonates reduce osteoclast activity and affects stromal cells in GCT, resulting in the reduction of their numbers and noticeable apoptosis. This results in better marginalization of the lesions and reduced recurrence. Extended curettage of friable GCT became easier and adequate which otherwise might not have been possible.

Keywords: Giant cell tumor, extended curettage, histopathology, recurrence, stromal cells, zoledronate

MeSH terms: Giant cell tumors, prospective studies, histopathology, bone cements

Introduction

Giant cell tumors (GCTs) of bone account for about 5% of primary bone tumors and 20% of all benign bone tumors. These are locally aggressive and have a tendency to recur.1,2 There is a slight female preponderance with a peak incidence in 20–40 years of age. The most frequent sites are lower end of femur, proximal tibia, and lower end of radius in that descending order. These lesions are characteristically chocolate brown, soft, spongy, and friable due to blood-filled cystic cavities in tumor mass. Histologically, there is an admixture of osteoclasts and stromal cells. Overexpression of receptor activator factor kappa-B ligand (RANK-L) by mononuclear neoplastic stromal cells promotes recruitment of reactive multinucleated giant cells which are capable of bone resorption.3

The treatment of GCT aims to eradicate the tumor tissue, reconstruct the bone defect, and restore a functional limb. Extended curettage and filling the cavity with polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) cement, bone grafts, or sandwich technique and an en bloc resection with suitable reconstruction are the mainstay of the treatment.4,5,6 Local recurrences after simple curettage without adjuvants have been reported to be >50%. Local recurrence has now been reported from 0% to 25% with adjuvants, while with wide resection, it is about 5% but has added morbidity. This can be decreased with the use of adjuvant treatment modalities such as phenol, hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), liquid nitrogen, high-speed burring, and thermo-coagulation.6,7,8

Zoledronic acid is a bisphosphonate (1-Hydroxy-2-imidazol -1-yl-phosphonoethyl, by activating protein kinase C, acts as an inhibitor of osteoclastic bone resorption and induces antiproliferative activity along with apoptotic effect in vitro, resulting in increased extracellular calcium concentration).9,10,11,12,13,14 It may be helpful in the management of GCT via modification in the role of giant cells as well as stromal cells.10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18

We conducted a prospective comparative study to ascertain the effect of zoledronic acid on the histopathology of GCT and recurrence rate.

Materials and Methods

37 patients (15 males, 22 females) of biopsy proved GCT of bones reported between 2012 and 2015 were included in this study. X-rays were done in two planes, i.e., anteroposterior and lateral views of the affected areas. The computed tomography scan and magnetic resonance imaging of the tumor site were also performed for local staging. The diagnoses were confirmed histopathologically with an open or core needle biopsy in all patients. Renal functions were assessed in all the cases where zoledronate was given and they were properly hydrated. The study group was (n = 18) given three doses of 4 mg intravenous zoledronic acid at 3-week intervals. The extended curettage was performed 2 weeks after the last infusion. Intravenous zoledronate 4 mg in 100 ml normal saline was infused slowly over 45–60 min under observation. The control group (n = 19) was treated with extended curettage only The patients with extensive lesions with extension in the soft tissue with hardly any bone for curettage with intraarticular extension requiring excision, metastatic disease, neurovascular involvement, and those previously treated were excluded from the study.

The volume calculation of the lesion (GCT) was done at the time of reporting of the patients to outdoor before biopsy. Two views of X-rays were obtained. It was calculated individually depending on the radiological shape of the defect as follows: cylindrical defect = ABC × 0.785, i.e., (π × A/2 × B/2 × C) and for spherical defect = ABC × 0.52, i.e., (4/3× π × A/2 × B/2 × C/2), where A = width, B = depth, and C = height. The sizes of the lesions in the study group were measured on X-rays before biopsy. The radiological changes noted after the last infusion were assessed on plain radiographs of the affected parts.

Patients were operated after obtaining anesthetic clearance and written informed consent. Extended curettage was performed in both the groups. A large cortical window almost as large as the lesion itself was made to have a good exposure of the cavity. Adequate exposures of the lesion minimize the tumor cells to be left behind around the corner as well as under the overhanging shelves of the near cortices. Extended mechanical curettage was done using the sharp curettes, bone nibblers, and high-speed burr for removing the ridges and septae. Thorough pulsatile jet lavage was done to wash the residual tumor cells. Every nook and corner was visualized for thorough excision of the pathological tissue.

The defect after bone curettage was filled by autograft, allograft, or bone substitutes, depending on the amount of subchondral bone thickness. The cases with cementation were not included in this study because this adjuvant can influence the recurrence due to its thermal effect on the wall of the cavity.

Histopathological examination

An experienced pathologist analyzed postinfusion histopathological changes in the curetting after extended curettage and compared them with the histopathology of biopsy slides made for diagnosis before infusions. These were subjected to assessing the area of fibrosis, calcification, new bone formation, and cell types including stromal and giant cells with their ratios. All the blocks were subjected to strap sectioning to pick up every 10th section on the glass slide. All the samples were also subjected to microscopic examination to calculate in terms of total percentage of calcification, ossification, and fibrosis of the total tumor area. Average percentage was calculated after combining the area of all the sections. The tumor areas that have not undergone secondary changes in terms of ossification, calcification, and fibrosis were then subjected to calculation of ratio of stromal cells to osteoclastic giant cells.

All the patients were followed up at the 3-month interval for 2 years and 6-month interval thereafter for functional outcome and local recurrence.

Results

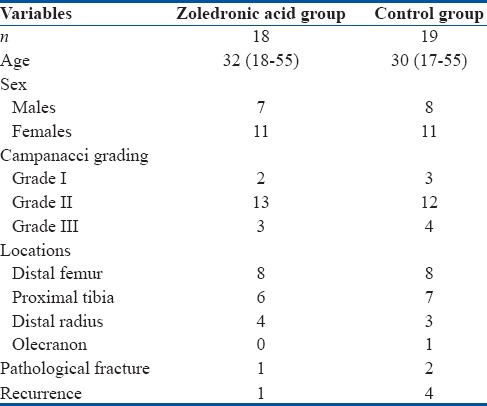

The mean age of patients was 36 years (range 17–55 years); there were 15 males and 22 females; lower limbs were involved in 20 cases whereas upper limbs in 17 cases; right side was involved in 21 cases and left side in 16 cases [Table 1]. Three patients had preoperative pathological fractures. Campanacci grading system results were as follows: five patients were with Grade I, 25 patients with Grade II, and 7 patients with Grade III. The various sites of GCT were femur (n = 16), tibia (n = 13), radius (n = 7), and olecranon (n = 1). The mean volume of GCT was 31.29 cm3 and 32.20 cm3 in the study and control groups, respectively. The following observations were made.

Table 1.

Comparative data of patients in the study and control groups

Tumor size

In the study group, it was observed that tumor size remained stationary in 13 cases whereas unexpectedly increased in 5 cases. In controls, tumor size remained same or slightly increased in all the 19 cases over 3 weeks till operated with extended curettage.

Histopathological changes

All the diagnostic biopsy samples and postoperative curettage tissues of all the patients were sent for histopathological examination. It was observed that calcification and fibrosis were not found in any primary biopsy which all showed a uniform sprinkling of giant cell among stromal cells. In primary biopsy samples, it varied from 10:1 to 100:1. In postinfusion biopsy samples, stromal cells and giant cells were not observed in calcification, ossification, and fibrosis areas while other areas showed that the ratio of stromal cell to giant cell had increased between 3 and 15 times; however, these stromal cells acquired morphological changes of fibroblastic-fibrocytic series focally. In none of the controls, curetting revealed fibrosis, calcification, and ossification, and also the stromal to giant cell ratio remained unaltered when compared with diagnostic biopsy slides.

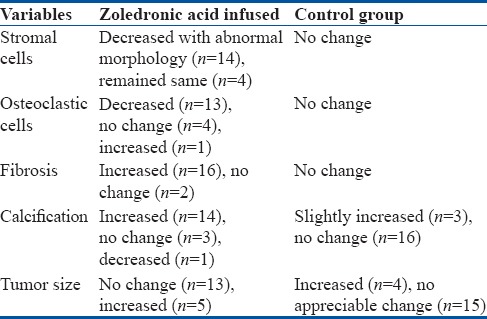

Histopathological changes were compared in both the groups as described in Table 2. In the study group, significant changes were observed in postoperative curetting as compared to preoperative biopsy slides. In 77.78% of cases (n = 14), the number of stromal cells decreased whereas remained equal in 22.22% of cases (n = 4) but with abnormal morphology in all cases. The number of osteoclasts decreased in 72.22% cases (n = 13) and unexpectedly increased in one case, while remained unchanged in 22.22% of cases (n = 4). There was no fibrosis and calcification in preinfusion tissues, but in postoperative slides, fibrosis in matrix of tumor was observed which was not like normal fibrosis. Amount of calcification also increased in the matrix of tumor which was abnormally spread and abnormally stained than the normal except in one case where it disappeared or decreased. Hence, abnormal fibrosis and calcifications was a universal phenomenon after zoledronic acid infusion [Figures 1 and 2].

Table 2.

Comparison of histopathological changes in postoperative slides with that of preoperative biopsy slides

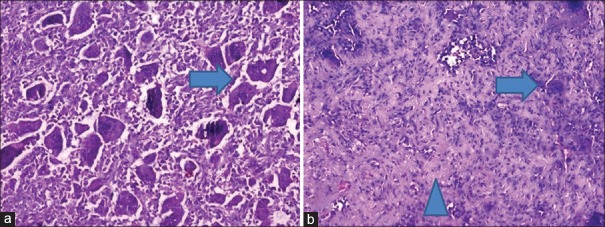

Figure 1.

Histopathology of core biopsy slides (H and E, ×100) (a) before zoledronic acid infusion showing proportionately distributed osteoclastic giant cells among stromal cells (arrow) and (b) after zoledronic acid infusions showing marked reduction in the number of giant cells (arrow) and morphological changes in stromal cells along with fibrosis (arrow head)

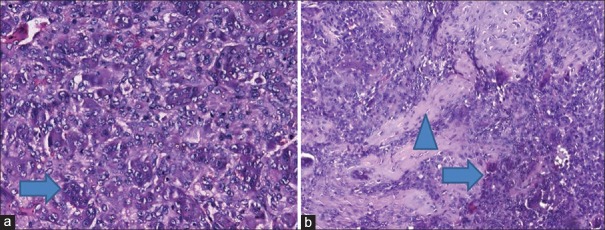

Figure 2.

Histopathology of core biopsy slides (H and E, ×400) (a) before zoledronic acid infusion showing large number of osteoclastic giant cells among stromal cells showing mild pleomorphism (arrow) and (b) after zoledronic acid infusions showing marked reduction in the number of giant cells (arrow) and morphological changes in stromal cells along with areas of calcification and fibrosis (arrow head)

Recurrence

Recurrence was found in only 1 out of 18 cases in the study group in a patient of GCT lower end radius whereas 4 out of 19 cases in control group with two in lower radius and one each in distal femur and proximal tibia (P = 0.47). These were similarly in matched pairs in view of the location, size, and age of the patients. The mean followup period was 32 months (range 24–70 months).

Functional results

The functional results were assessed using the Musculoskeletal Tumor Society scores, which were 27.50 (range 24–30) and 27.00 (range 23.50–30) in the study and control groups, respectively, and thus were almost similar in both groups as all these were joint-preserving surgeries. We observed no side effects of zoledronic acid in any of the cases.

Discussion

Antiosteolytic and antitumor function of bisphosphonates by inhibition of farnesylation and geranylgeranylation of RAS-related proteins has attracted lot of attention. Zoledronic acid increases the extracellular calcium concentration and this effect is augmented with dexamethasone and thalidomide using this property in the treatment of myeloma by increasing cytotoxicity and reduction of destruction of bone.9 Thus, it is used along with cancer chemotherapy to treat bone problems that may occur with multiple myeloma and other metastatic deposits to the bones and also for treating hypercalcemia observed in these cancers. It lowers high blood calcium levels by reducing the amount of calcium released from bones into circulation and slows the breakdown of bones by cancer to prevent bone fractures. It has been approved for the treatment of bone metastasis associated with breast, prostate, lung, and renal cancers.19

Apart from the use of bisphosphonates in osteoporosis, myeloma, and metastasis, recently, the potential of bisphosphonates in killing tumor cells and its use in GCT have been reported in various studies in the literature.10,12,13,14,15,16,17,18 There has been ongoing effort to reduce the local recurrence in GCTs after curettage using different adjuvants.20,21 Moreover, zoledronic acid is now one of these being used to decrease the recurrence in GCT.10,11,12,13,14,15 Even the recurrences are now being satisfactorily managed with conservative treatment, i.e., further curettage using adjuvants such as PMMA and bisphosphonates. Effective adjuvant systemic therapy with reconstruction is very helpful in the effective management of GCT. Stable and adequate filling of cavities with graft or cement and satisfactory healing after tumor removal with systemic bisphosphonate therapy are associated with patient's clinical benefit, especially around weightbearing joints.22 Vult von Steyern et al. analyzed the local recurrence of GCT in long bones following curettage and cementing in a retrospective study. They concluded that local recurrence after surgery in long bones can generally be successfully treated with further curettage and cementing, with only a minor risk of increased morbidity, thus observing that PMMA cement reduces the recurrence.23 Tse et al. studied 24 patients treated with zoledronic acid given preoperatively and found that only one patient developed local recurrence as compared to 30% recurrence in the control group.15 Our results are similar to this study and show effectiveness of zoledronate to reduce recurrence rates. Similar results have been reported in many studies.10,11,12,13,14,15 They observed that intravenous zoledronic acid causes apoptosis of both giant cell and stromal cells which are responsible for lysis of bone in GCT, thus reducing the overall recurrence rate. We also observed the similar results as the recurrence was significantly less as compared to the control group.

Arpornchayanon and Leerapun24 treated a case of extensive GCT of sacrum with intravenous 4 mg zoledronate every 4 weeks for seven courses. The curettage and bone cement implantation were performed after 5 months of the treatment with zoledronate. Histological examination from specimen curetted at the 5th month after receiving zoledronate showed no residual GCT and observed significant calcification around the lesion.24 These results are similar to that of our study and reveal the effectiveness of zoledronate adjuvant therapy. In the present study, zoledronic acid had significant histological changes; however, it had variable effects on the sizes of the lesions.

In this series, in 13 patients, size remained stationary whereas it increased in five cases showing that zoledronic acid has unpredictable effects on progression of the size of tumor. However, it showed morphological alteration in size and shape of stromal cells. There were abnormal stromal cells which started secreting matrix leading to fibrosis and calcification, and may be responsible for the increase in the size of the tumor in some cases as these cells became more secretory as noted on histopathology. This provided good marginalization of tumor, leading to easy and adequate surgical curettage of GCT. The fibrosis and calcification contents varied in different cases. Reason for these variations has to be explored by more such studies. There was one recurrence out of 18 cases in the study group compared to four recurrences out of 19 in the control group. This is, as discussed, attributed to the reduction of osteoclasts and changes in stromal cells due to zoledronic acid.

Strengths and limitations of study

The study design is prospective conducted in a single institute (tertiary care center) and all surgeries were performed by a senior experienced orthopedic oncology surgeon. All the biopsy samples were analyzed by an efficient onco-pathologist. The results are significant in favor of preoperative zoledronate infusion with respect to histopathological and recurrence outcomes, but the study size is comparatively smaller. The results may be more significant in large sample with long period of postoperative followup. A multicenter trial and meta-analysis may overcome these limitations.

Conclusions

We conclude that zoledronic acid affects both osteoclasts as well as stromal cells in GCT. By affecting these two main cells of the tumor, it may have reduction of recurrence rate. It accelerates fibrosis and calcification, thus providing better marginalization of the lesions for extended curettage which may not be otherwise possible. We observed that the overall recurrence rate did reduce in this small series of cases with preoperative zoledronate infusion.

Declaration of patient consent

The authors certify that they have obtained all appropriate patient consent forms. In the form the patient(s) has/have given his/her/their consent for his/her/their images and other clinical information to be reported in the journal. The patients understand that their names and initials will not be published and due efforts will be made to conceal their identity, but anonymity cannot be guaranteed.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Carnesale PG. General principles of tumors. In: Crensaw AH, editor. Campbell's Operative Orthopedics. Missouri: Mosby Year Book; 1992. pp. 195–234. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Campanacci M, Baldini N, Boriani S, Sudanese A. Giant-cell tumor of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:106–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Athanasou NA, Bansal M, Forsyth R, Reid RP, Sapi Z. Giant cell tumour of bone. In: Fletcher CD, Bridge JA, Hogendoorn PC, Mertens F, editors. World Health Organization - Classification of Tumors of Soft Tissue and Bone. Lyon: IARC Press; 2013. pp. 321–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Szendröi M. Giant-cell tumour of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2004;86:5–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wysocki RW, Soni E, Virkus WW, Scarborough MT, Leurgans SE, Gitelis S, et al. Is intralesional treatment of giant cell tumor of the distal radius comparable to resection with respect to local control and functional outcome? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473:706–15. doi: 10.1007/s11999-014-4054-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gitelis S, Mallin BA, Piasecki P, Turner F. Intralesional excision compared with en bloc resection for giant-cell tumors of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75:1648–55. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199311000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blackley HR, Wunder JS, Davis AM, White LM, Kandel R, Bell RS, et al. Treatment of giant-cell tumors of long bones with curettage and bone-grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1999;81:811–20. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199906000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Turcotte RE. Giant cell tumor of bone. Orthop Clin North Am. 2006;37:35–51. doi: 10.1016/j.ocl.2005.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ural AU, Yilmaz MI, Avcu F, Pekel A, Zerman M, Nevruz O, et al. The bisphosphonate zoledronic acid induces cytotoxicity in human myeloma cell lines with enhancing effects of dexamethasone and thalidomide. Int J Hematol. 2003;78:443–9. doi: 10.1007/BF02983818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chang SS, Suratwala SJ, Jung KM, Doppelt JD, Zhang HZ, Blaine TA, et al. Bisphosphonates may reduce recurrence in giant cell tumor by inducing apoptosis. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2004:426103–9. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000141372.54456.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fujimoto N, Nakagawa K, Seichi A, Terahara A, Tago M, Aoki Y, et al. A new bisphosphonate treatment option for giant cell tumors. Oncol Rep. 2001;8:643–7. doi: 10.3892/or.8.3.643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau CP, Wong KC, Huang L, Li G, Tsui SK, Kumta SM, et al. A mouse model of luciferase-transfected stromal cells of giant cell tumor of bone. Connect Tissue Res. 2015;56:493–503. doi: 10.3109/03008207.2015.1075519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lau CP, Huang L, Wong KC, Kumta SM. Comparison of the anti-tumor effects of denosumab and zoledronic acid on the neoplastic stromal cells of giant cell tumor of bone. Connect Tissue Res. 2013;54:439–49. doi: 10.3109/03008207.2013.848202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lau CP, Huang L, Tsui SK, Ng PK, Leung PY, Kumta SM, et al. Pamidronate, farnesyl transferase, and geranylgeranyl transferase-I inhibitors affects cell proliferation, apoptosis, and OPG/RANKL mRNA expression in stromal cells of giant cell tumor of bone. J Orthop Res. 2011;29:403–13. doi: 10.1002/jor.21249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tse LF, Wong KC, Kumta SM, Huang L, Chow TC, Griffith JF, et al. Bisphosphonates reduce local recurrence in extremity giant cell tumor of bone: A case-control study. Bone. 2008;42:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2007.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cheng YY, Huang L, Lee KM, Xu JK, Zheng MH, Kumta SM, et al. Bisphosphonates induce apoptosis of stromal tumor cells in giant cell tumor of bone. Calcif Tissue Int. 2004;75:71–7. doi: 10.1007/s00223-004-0120-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cheng YY, Huang L, Kumta SM, Lee KM, Lai FM, Tam JS, et al. Cytochemical and ultrastructural changes in the osteoclast-like giant cells of giant cell tumor of bone following bisphosphonate administration. Ultrastruct Pathol. 2003;27:385–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lau YS, Sabokbar A, Gibbons CL, Giele H, Athanasou N. Phenotypic and molecular studies of giant-cell tumors of bone and soft tissue. Hum Pathol. 2005;36:945–54. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2005.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rosen LS, Gordon D, Tchekmedyian S, Yanagihara R, Hirsh V, Krzakowski M, et al. Zoledronic acid versus placebo in the treatment of skeletal metastases in patients with lung cancer and other solid tumors: A phase III, double-blind, randomized trial – The zoledronic acid lung cancer and other solid tumors study group. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:3150–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Klenke FM, Wenger DE, Inwards CY, Rose PS, Sim FH. Recurrent giant cell tumor of long bones: Analysis of surgical management. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:1181–7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1560-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Klenke FM, Wenger DE, Inwards CY, Rose PS, Sim FH. Giant cell tumor of bone: Risk factors for recurrence. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:591–9. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1501-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Xu HR, Niu XH, Zhang Q, Hao L, Ding Y, Li Y, et al. Subchondral bone grafting reduces degenerative change of knee joint in patients of giant cell tumor of bone. Chin Med J (Engl) 2013;126:3053–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Vult von Steyern F, Bauer HC, Trovik C, Kivioja A, Bergh P, Holmberg Jörgensen P, et al. Treatment of local recurrences of giant cell tumour in long bones after curettage and cementing. A Scandinavian sarcoma group study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:531–5. doi: 10.1302/0301-620X.88B4.17407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arpornchayanon O, Leerapun T. Effectiveness of intravenous bisphosphonate in treatment of giant cell tumor: A case report and review of the literature. J Med Assoc Thai. 2008;91:1609–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]