Abstract

BACKGROUND AND GOAL:

Screening of fetal anomalies is assumed as a necessary measurement in antenatal cares. The screening plans aim at empowerment of individuals to make the informed choice. This study was conducted in order to compare the effect of group and face-to-face education and decisional conflicts among the pregnant females regarding screening of fetal abnormalities.

METHODS:

This study of the clinical trial was carried out on 240 pregnant women at <10-week pregnancy age in health care medical centers in Mashhad city in 2014. The form of individual-midwifery information and informed choice questionnaire and decisional conflict scale were used as tools for data collection. The face-to-face and group education course were held in two weekly sessions for intervention groups during two consecutive weeks, and the usual care was conducted for the control group. The rate of informed choice and decisional conflict was measured in pregnant women before education and also at weeks 20–22 of pregnancy in three groups. The data analysis was executed using SPSS statistical software (version 16), and statistical tests were implemented including Chi-square test, Kruskal–Wallis test, Wilcoxon test, Mann–Whitney U-test, one-way analysis of variance test, and Tukey's range test. The P < 0.05 was considered as a significant.

RESULTS:

The results showed that there was statically significant difference between three groups in terms of frequency of informed choice in screening of fetal abnormalities (P = 0.001) in such a way that at next step of intervention, 62 participants (77.5%) in face-to-face education group, 64 members (80%) in group education class, and 20 persons (25%) in control group had the informed choice regarding screening tests, but there was no statistically significant difference between two individual and group education classes. Similarly, during the postintervention phase, there was a statistically significant difference in mean score of decisional conflict scale among pregnant women regarding screening tests in three groups (P = 0.001).

DISCUSSION AND CONCLUSION:

With respect to effectiveness of group and face-to-face education methods in increasing the informed choice and reduced decisional conflict in pregnant women regarding screening tests, each of these education methods may be employed according to the clinical environment conditions and requirement to encourage the women for conducting the screening tests.

Keywords: Chromosomal abnormalities, decision making, education, informed consent, prenatal screening

Introduction

The existing anomalies at birth are deemed as one of the reasons for mortality of neonates and an important health care problem throughout the world.[1] The trisomy-21 (Down's syndrome) is the most morbid nonlethal trisomy that has been further noticed than all other syndromes in genetic screening programs,[2] and the frequency of this syndrome is one per 814 live childbirths in Iran.[3] At present, according to fetal anomaly screening protocol in Iran, regardless of the parameter of age, all the pregnant women are suggested to conduct Down's syndrome screening test, Edward's syndrome, and open neural tube defects in Iran and with respect to time limitation for taking permission for legal abortion and necessity for parental awareness to select fetal anomalies screening, some information is given to parents in this regard in first visit of pregnancy (6–10th pregnancy week).[4] Concerning to conducting screening tests, the pregnant mother has any right to receive total needed information before execution of tests in order to be able to measure screening advantages against its risks and for making a decision.[5] Whereas, the screening tests may lead to making some decisions about diagnostic tests as well as fetal abortion thus the specialists in health care field, essentially emphasize in this point that the families to be able to make a decision on their own.[6] The screening plans aim at empowerment of individuals in making an informed choice and reducing doubt and ambiguity in making a decision.[7] In order to empower the individuals to make the informed choice, they need to be equipped with objective and adequate knowledge with a high quality and appropriate regarding the results of their choices.[8] The researchers have indicated that improving knowledge and amount of information may affect on recognition of key and important subjects and increase their perception and make their attitude positive.[9,10] The study of Chiang et al. (2006) in Taiwan showed that despite the fact that the screening tests are voluntarily presented to the pregnant mother but it seems that the final process of decision-making is imposed by health care system to the mothers.[11] In his investigation in Greece, Gourounti and Sandall came to this result that about 56% of pregnant women had no informed choice for conducting fetal anomalies screening tests, which were considered as the main cause for defective knowledge.[12] In their study, Dormandy et al. mentioned the low-level awareness and weak social-economic status as the factors for lack of informed choice regarding screening tests during pregnancy period.[13] The result of study done by Bekker et al. showed that those women who conducted screening tests by informed choice might express less decisional conflicts[14] therefore although physician or midwife should make the pregnant women aware of execution of the screening tests, giving such information is not adequate only and the pregnant women are required to know how many side-effects and benefits will be followed by these tests for them.[15] Not only the mother and her embryo's health care are noticed during pregnancy medical exams and the needed measures are made, but also the mother receives the necessary education as one of the most efficient prophylactic factors against the occurrence of mortalities and reducing the side-effects at pregnancy period. This education may be effective when they could be followed by a change of positive attitude in them as well.[16] Certainly, selection of appropriate education method plays an essential role in the rate of learning and encouragement of pregnant women to change the health care-relevant behaviors. Concerning the selection of the given technique, the education goal, financial solvency, and personnel of system should be taken into consideration.[17] The group and face-to-face education are one of the educational approaches in health care education programs. As a type of direct education techniques, the advantage of group and face-to-face education is in that the participants are located actively through the learning trend, and the ambiguities are removed by asking questions, and this may exert a further effect on them.[18] Despite the effectiveness of educational programs, there are few evidences about rate of impact of these programs on the informed choice and decisional conflict among pregnant women regarding fetal abnormalities screening tests therefore with respect to importance of early diagnosis of chromosomal disorders and lack of reporting any study to compare the effect of education on rate of informed choice and decisional conflict in pregnant women about fetal anomalies screening, the present study was carried out in Mashhad city in 2014.

Methods

This study as a clinical trial was conducted after approval by Ethics Committee in academic research on 240 pregnant women with <10-week pregnancy age who have referred to health care medical centers for the first time to make file for their current pregnancy at Mashhad city from July 2014 through March 2015. After confirmation of research by Ethics Committee of the Mashhad University of Medical Sciences and acquisition of recommendation letter from Mashhad University of Nursing and Midwifery and submission of them to the related health care centers and after expressing the objectives of this study and taking agreement from pregnant women and written consent of them and by considering ethical codes, the sampling process was done and research was conducted. Primarily, Healthcare Center No. 3 was selected randomly among health care and medical centers in Mashhad city and by taking lots and then three affiliated centers to this health care center were selected, which were similar in terms of social texture. These three groups were also allocated randomly and by using lottery method so that any center was allocated to one group and afterward sampling was conducted by nonstochastic and easy method. The sample size, which was extracted according to the guiding study on 30 participants from research units (10 members in any group), was calculated with confidence coefficient at level 95% and potential (80%) and using formula to compare the ratios with 71 members in any group in which it was determined as 80 members in any group by considering 10% excluded members of the sample. The inclusion criteria for this study comprised of Muslim persons with Iranian nationality, <10-week pregnancy age, having, at least, education at 5-grade from primary school, lack of indication for conducting diagnostic tests (background for delivery of child with fetal abnormalities, history of positive result of amnion-synthesis or biopsy of chorionic villi in former pregnancies, positive familial history of a chromosomal or genetic disorder, and parental vector for one of chromosomal anomalies), lack of former background to conduct screening or diagnostic tests for fetal abnormalities in previous pregnancies, and nonemployment in research units at health care medical centers. The exclusion criteria of this study consisted of nonparticipation in one of education sessions, leaving education class before the end of it, lack of tendency to continue participation in this study, fetal death during research, and occurrence of inadvertent events during the period of holding education sessions for the pregnant mother.

The data collection tools included individual-midwifery information form, informed choice questionnaire, and decisional conflict scale.

The individual-midwifery information form comprised of 28 questions about personal and midwifery specifications and fetal anomalies screening tests. The informed choice questionnaire consisted of three scales of knowledge, attitude, and behavior of pregnant women about conducting fetal anomalies screening tests during pregnancy. Sixteen items were used to examine variable of knowledge based on the content of screening and diagnostics procedure of fetal anomalies and education content, and educational booklet were prepared. Giving proper answers to more than eight questions represented as high knowledge and also giving answers to eight questions or less expressed the low knowledge. The attitude scale for mothers also consisted of four items with score values (1–7) in which the minimum score was 4 and the maximum was 28 and mean score was considered as 16 that denoted no-comment attitude while the higher and lower score than mean score expressed positive and negative attitude, respectively. Finally, the behavior of pregnant women versus conducting screening tests was explored based on the recorded results in vitro. The criterion of knowledge for informed choice was defined for pregnant mother in two forms: (1) good knowledge, positive attitude, and conducting screening tests; (2) good knowledge, negative attitude, and nonexecution of screening tests. The criterion for lack of uninformed choice was determined in six forms: (1) high knowledge, negative attitude, conducting screening tests, (2) high knowledge, positive attitude, nonexecution of screening tests, (3) low knowledge, positive attitude, conducting screening tests, (4) low knowledge, negative attitude, conducting screening tests, (5) low knowledge, positive attitude, nonexecution of screening tests, and (6) low knowledge, negative attitude, and nonexecution of screening tests.

Decisional conflict scale included 16 items at Likert measurement spectrum in which score values of each of them ranged from 0 to 4 and in 5-point form. Scores of 16 items were added to acquire total score in this questionnaire and then their sum was divided by number 16 and finally the product was multiplied to 25. Total score <25 denotes a lack of decisional conflict.

The content validity of education and dimensions of knowledge and behavior were confirmed in informed choice questionnaire using content validity method. The validity of informed choice questionnaire has been verified by Nagle et al. and validity of decisional conflict scale was confirmed by O’Connor[19,20] and after translation of two aforesaid inventories, they were approved by means of content-validity technique.

Reliability of dimensions of knowledge and attitude in the informed choice questionnaire was determined by means of internal consistency through calculation of Cronbach alpha coefficient, and they were confirmed as r = 0.82 and r = 0.85. The internal consistency method was also employed to evaluate postbehavior reliability using Kuder–Richardson statistical test, and it was verified as r = 0.76. The reliability of decisional conflict scale was approved with Cronbach alpha coefficient (0.78) by O’Connor,[19] and the present study was determined with the calculation of Cronbach alpha coefficient and r = 0.97 using internal consistency.

The education content was identical in two intervention groups and included some explanations about screening tests at first and second semesters along with diagnostic tests during pregnancy period and specifications of children with fetal abnormalities. Education course was held for two groups in two sessions once a week for two subsequent weeks. The education content in the first session included importance, characteristics, benefits, and side-effects of screening tests at first semester as well as characteristics of children with chromosomal anomalies and open neural tube defects and the second session consists of screening at second semester and diagnostic tests during pregnancy period. The education content in both sessions in face-to-face education group was presented using explanatory education method along with giving various images regarding fetal anomalies, and then questions and answers were proposed and also in group education class (5-member groups and 16 groups totally) education was held by lecture in both sessions along with powerpoint software and then questions and answers were given and at the end of first session education package (including the education booklet about screening and diagnostic tests during pregnancy period with these contents: importance, characteristics, side-effects of screening tests at first and second semesters and diagnostic tests and characteristics of children with chromosomal anomalies and open neural tube defects) was prepared by researcher and given to them for reading at home. Education course was held by researcher and education period was held in two sessions before both education groups in 45–60 min the usual care was executed for pregnant women by midwives in the control group.

The informed choice questionnaire and decisional conflict scale were completed in two phases before intervention and during the 20–22nd week of pregnancy. The data analysis was carried out using SPSS statistical software (version 16, IBM Company Armonk, NY, USA) and statistical tests of Chi-square test, Kruskal–Wallis test, Wilcoxon test, Mann–Whitney U-test, one-way analysis of variance test, and Tukey's range test were conducted. The P < 0.05 was considered as a significant.

Results

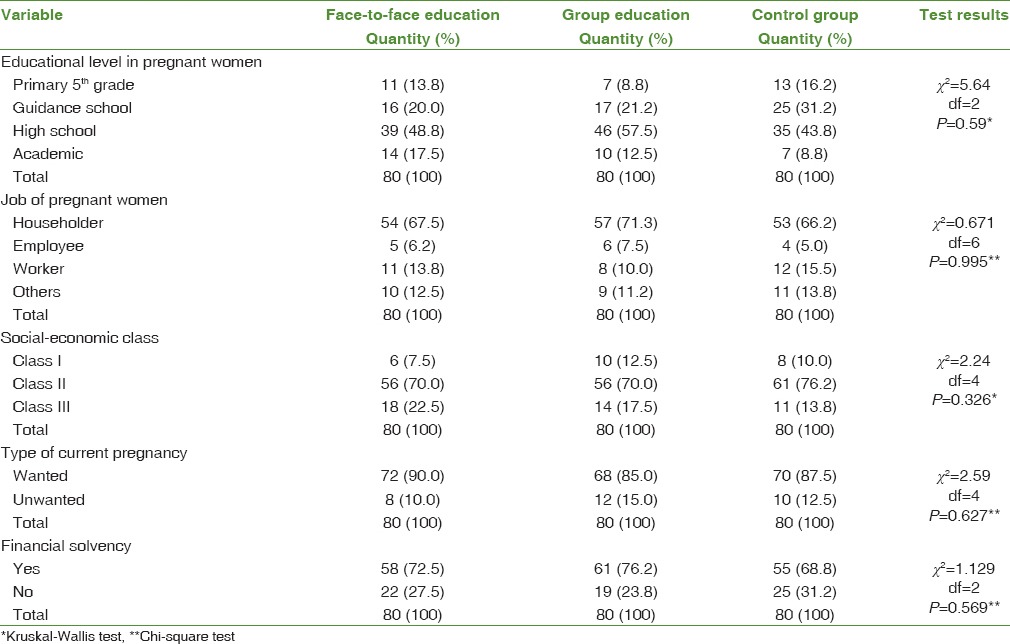

Three groups were homogeneous in this study in terms of mother's education level (P = 0.59), her job (P = 0.995), social-economic class (P = 0.326), type of current pregnancy (P = 0.627), and financial solvency to pay the costs (P = 0.569) [Table 1].

Table 1.

Frequency distribution of research units based on educational level and job of pregnant women, social-economic class, type of current pregnancy, and financial solvency for payment of costs in three face-to-face and group education regarding tests and control group

The mean age of pregnant women in face-to-face education group, group education, and control group was 27.4 ± 5.3, 27.7 ± 5.0, and 26.7 ± 5.7 years, respectively. The mean number of living children was also 1.9 ± 0.87, 2.03 ± 0.8, and 1.8 ± 0.81, respectively, in face-to-face education, group education, and control group so that three groups were homogeneous in terms of mother's age (P = 0.491), number of pregnancy (P = 0.305), and number of living children (P = 0.927) before intervention.

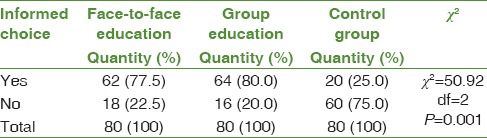

There was a statistically significant difference among three groups in terms of the variable of the informed choice regarding screening of fetal anomalies (P = 0.001). Similarly, pairwise comparison between groups indicated that there was statistically significant difference among face-to-face and control groups (P = 0.001), and group education and control group (P = 0.001) in terms of variable of informed choice but there was no statistically significant difference among face-to-face group and group education (P = 0.077) in terms of this variable [Table 2].

Table 2.

Frequency distribution of pregnant women based on informed choice in three groups of face-to-face and group education regarding screening tests and control group

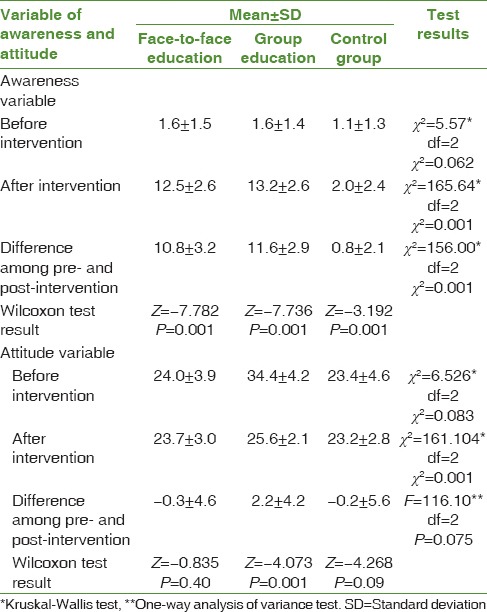

The given results from Wilcoxon test showed that the mean score of knowledge from screening tests was increased significantly in all three face-to-face and group education and control groups after intervention (P = 0.001). The results of Kruskal–Wallis test indicated at postintervention phase that the mean score on variable knowledge of pregnant women had a statistically significant difference in three studied groups (P = 0.001). The result of Mann–Whitney U-test for pairwise comparison of groups showed that there was statistically significant difference in mean score for the variable of knowledge of pregnant women regarding tests after execution of intervention among face-to-face education and control groups (P = 0.001), and group education and control group (P = 0.001). But, there was no statistically significant difference among face-to-face group and group education class (P = 0.059).

Likewise, the results came from Wilcoxon test indicated that mean score of variable of attitude of pregnant women regarding screening tests in group education after intervention was significantly greater than the preinvention phase (P = 0.001), but this difference was not statistically significant in face-to-face education and control groups (P = 0.09 and P = 0.40). The results of Kruskal–Wallis test at postintervention phase showed that there was statistically significant difference in mean score for variable attitude of pregnant women in three groups (P = 0.001) so that the result of Mann–Whitney U-test for pairwise comparison of groups indicated that the mean score of variable attitude in pregnant women at postintervention phase included statistically significant difference among group education and control group (P = 0.001) and face-to-face education group and group education (P = 0.001). However, there was no significant difference among face-to-face education and control group (P = 0.76) [Table 3].

Table 3.

Mean and standard deviation for scores of knowledge and attitude of pregnant women in face-to-face education group and group education regarding screening tests with control group

The results of Chi-square test indicated that there was statistically significant difference among three studied groups in terms of conducting screening tests (P = 0.001) so that 72 members (90.0) in face-to-face education group, 64 members (80.0) in group education class, and 35 members (43.8) in control groups that executed screening tests.

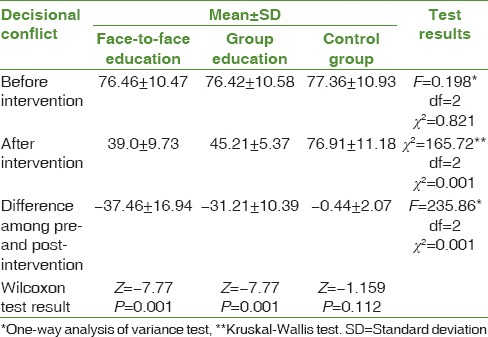

Similarly, pairwise comparison between groups showed that there was statistically significant difference among face-to-face education group and control group (P = 0.001) and group education class with control group (P = 0.001) in terms of behavior of pregnant women regarding conducting tests but there was no statistically significant difference among face-to-face education group and group education class in terms of this variable (P = 0.20). The results of Wilcoxon test indicated that the mean score for variable decisional conflict in pregnant women regarding screening was significantly reduced in both group education and face-to-face education group after intervention (P = 0.001). At postintervention phase, there was statistically significant difference in mean score of decisional conflict for pregnant women regarding screening among three groups (P = 0.001). Likewise, the result of Mann–Whitney U-test for pairwise comparison of groups indicated that there was statistically significant difference in mean score of decisional conflict in pregnant women about screening after execution of intervention among face-to-face education group and group education class (P = 0.001), face-to-face education and control groups (P = 0.001), and also among group education and control group (P = 0.001) [Table 4].

Table 4.

Mean score and standard deviation of variable of decisional conflict in pregnant women in three groups: Face-to-face-education group, group education regarding screening tests, and control group

Discussion

The majority of the research units in this study that had the informed choice were included in two groups of face-to-face education group, and group education class regarding screening of fetal anomalies but the percentage of the informed choice was greater in group education class. The results of a study done by van den Berg et al. indicated that education of pregnant women regarding screening tests by means of educational aid devices such as education booklet might increase the informed choice in the intervention group.[7] Moreover, application of decisional-aid devices such as educational booklet and pamphlet also improved the rate of the informed choice in pregnant women in the intervention group in the study of Nagle et al.[20] Mathieu et al. concluded from their study that presentation of information by educational booklet regarding mammographic screening might improve the rate of informed choice in females.[21] The results of these studies were consistent with the results of the present research. Smith et al. indicated that education by the educational movie and information booklet might be more efficient than the usual education in increasing the informed choice in individuals regarding screening of intestinal cancer.[22] The informed choice about screening tests depends on three important factors of knowledge, attitude, and behavior of the given individual.[23] On the other hand, knowledge, attitude, and behavior are trainable and acquisitive, and education is assumed as a tool and method for this activity.[24] Education of pregnant women, especially regarding screening and diagnostic tests for pregnancy period is deemed as a vital activity in process of informed choice;[25] for this reason, presentation of adequate information, change in attitudes, and employing contributory techniques in decision making have been recommended as important elements in education for process of the informed choice.[26]

The mean score of the variable of knowledge was increased in pregnant women from three groups after education in the present research. Michie et al. concluded from their study that there was no statistically significant difference among rate of awareness of pregnant women who had received the information brochure regarding screening tests with those who have watched video movie in addition to receiving information brochure as well,[27] so this finding was not consistent with results of the current research. The information brochure and video movie have been given to the intervention groups for study and watching them at home. Similarly, there were 4–6 weeks as the time interval in the completion of questionnaires. In a study of Stefansdottir et al., the mean score of knowledge in the intervention group was higher than the control group for execution of screening tests of the information booklet they had received.[28] Likewise, in the investigation of Hewison et al., the mean score of awareness of pregnant women in intervention group, who had received education movie about screening of Down's syndrome, was significantly higher than in control group,[29] while the results of those studies were consistent with the present research.

The mean score of the variable of attitude in pregnant women was increased in group education class after intervention in this study. There was no statistically significant difference in score of the attitude of pregnant women in group education class for pregnancy period cares compared to control group in the study of Toghyani et al. (2008),[30] so this finding was not consistent with the results of present research in this regard. This may be due to the difference in educational content and inadequacy of education information to which the researchers have referred as well.

The frequency of conducting screening tests differed significantly in three studied groups in the current study (P = 0.001). In a study of Hewison et al., video education had no effect on the rate of conducting screening tests among intervention group and control group.[29] The reason for this difference may be related to the existing difference in method of education and technique of holding courses and number of sessions so that in investigation process of Hewison, the information video movie about screening tests was sent by mail to houses of pregnant women for watching while in the present study the information of screening was presented by face-to-face education and group education methods within verbal, written, and visual formats in two sessions.

After intervention in the current study, the mean score of decisional conflict in pregnant women about screening tests was significantly decreased in both classes of group education and face-to-face education groups. The shortage of knowledge about health care decisions is one of the efficient factors in creating decisional conflicts within the health care field.[31] Alternately, rising knowledge through education may create change in health care-related behaviors[30] and utilization from written, verbal, or multimedia information may cause reducing decisional conflicts as contributory tools in decision making.[31] It was also characterized in the study of Kaiser et al. (2004) that the mean score of decisional conflict variable in pregnant women after group counseling was reduced significantly compared to the period before counseling. The researcher expressed that the group education might act as a very efficient technique in supporting the decisions made by pregnant women.[32] Similarly, Hunter et al. (2005) concluded from their study that the rate of decisional conflict of pregnant women in the field of diagnostic tests after group counseling was significantly reduced[33] where the results of these studies were consistent with the result of present research. Bekker et al. showed that the mean score of decisional conflict for intervention group and control group was not significantly different in none of two phases immediately after counseling and 1 month after conducting diagnostic tests for Down's syndrome[14] and this finding was not consistent with the results of current study and one can refer to absence of pretest and possibility for intragroup comparison in study of Bekker and cultural, ethnic, and racial difference and ideological beliefs in research units for both studies as the possible reasons for this fact. On the other hand, education method, quantity, and time of educational sessions in the present study were different from the research of Bekker. The standard education approach is as efficient as counseling approaches in improving the level of knowledge among individuals, and rising knowledge may be an effective factor in the decision-making process as well.[34]

The strong point of this study was randomized allocation of the three groups to the centers, which were similar to each other in terms of social texture while one of the limitations in current research was this point that three affiliated centers to Health Center No. 3 were not selected randomly, and this issue might restrict generalization of results to total population.

Conclusion

Whereas, based on screening protocol in Iran conducting screening tests for fetal anomalies is suggested to all of the pregnant women, therefore, it is better to employ education methods in the presentation of screening information in order to improve attitude and behavior of pregnant women about conducting tests in addition to increasing their knowledge.[35] Hence, with respect to the effectiveness of group education and face-to-face education methods in improving the informed choice and reducing decisional conflicts in pregnant women regarding screening of fetal abnormalities thus each of these education methods can be utilized according to clinical environment conditions to encourage the pregnant mothers to use screening tests. Of course, given the group education method is more available and imposes lower economic burden onto the health care medical system,[36] it is suggested to adopt group education method for this purpose.

Financial support and sponsorship

Mashhad University of Medical Sciences.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This article was recorded under the clinical trial code No. IRCT2014081318785N1 as a result of the thesis in midwifery master's course with code 922882 in Mashhad University of Medical Sciences. We hereby express our gratitude to the respected research deputy of university because he was responsible for financial support for this project and also all of the mothers who participated in this study.

References

- 1.Ghorbani M, Parsiyan N, Mahmodi M, Jalalmanesh S. The study of incidence of congenital anomalies and relationship between anomakies and personal and family-social factors. Iran J Obstet Gynecol Infertil. 2004;6:66–73. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuningham GF, leveno KJ, Bloom SL, Hauth JC, Rouse DJ, Spong CY. Williams Obstetrics. 24th ed. Tehran Golban Medical Publisher; 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Farhad DD, Walizadeh DH, Sharif-Kamali M. Congenital malformations and genetic diseases in 1. Iranian infants. Hum Genet. 1986;74:382–5. doi: 10.1007/BF00280490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Styles screening and diagnosis of fetal abnormalities. Ministry of Health and Medical Education. 2011. [Last accessed on 2014 Oct 21]. Available at: http://www.google.com/gws/rd/ss .

- 5.Hwa HL, Huang LH, Hsieh FJ, Chow SN. Informed consent for antenatal serum screening for Down syndrome. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;49:50–6. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(10)60009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kleinveld JH. Psychological Consequences of Prenatal Screening. VU University Medical Center in Amsterdam. 2008:1–152. [Google Scholar]

- 7.van den Berg M, Timmermans DR, Ten Kate LP, van Vugt JM, van der Wal G. Are pregnant women making informed choices about prenatal screening? Genet Med. 2005;7:332–8. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000162876.65555.ab. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jepson RG, Hewison J, Thompson AG, Weller D. How should we measure informed choice? The case of cancer screening. J Med Ethics. 2005;31:192–6. doi: 10.1136/jme.2003.005793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lewis J, Leach J. Discussion of socio-scientific issues: The role of science knowledge. Int J Sci Educ. 2006;28:1267–87. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Prokop P, Leskova A, Kubiatko M, Diran C. Slovakian students knowledge of and attitudes toward biotechnology. Int J Sci Educ. 2007;29:895–907. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiang HH, Chao YM, Yuh YS. Informed choice of pregnant women in prenatal sceening tests for Down's syndrome. J Med Ethics. 2006;32:273–77. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.012385. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gourounti K, Sandall J. Do pregnant women in Greece make informed choices about antenatal screening for Down's syndrome? A questionnaire survey. Midwifery. 2008;24:153–62. doi: 10.1016/j.midw.2006.09.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dormandy E, Michie S, Hooper R, Marteau TM. Low uptake of prenatal screening for Down syndrome in minority ethnic groups and socially deprived groups: A reflection of women's attitudes or a failure to facilitate informed choices? Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:346–52. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyi021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bekker HL, Hewison J, Thornton JG. Applying decision analysis to facilitate informed decision making about prenatal diagnosis for Down syndrome: A randomised controlled trial. Prenat Diagn. 2004;24:265–75. doi: 10.1002/pd.851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hunt L. Routine prenatal genetic screening in a public clinic: Informed choice or moral imperative? Medical Humanities Report. 2001;22:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Niaki MT, Behmanesh F, Mashmoli F, Azimi H. Impact of prenatal group education on knowledge, attitude and choice of delivery in nulliparous women. Iran J Med Educ. 2010;10:124–30. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Barimnegad L, Asemi S, Samieehaghani N. Effect of individual and group training on therapy, and the rate of complications in patients taking warfarin after heart valve replacement. Iran J Med Educ. 2012;12:10–8. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Golaghayi F, Khosravi SH. Patient education process in clinical care and outpatient. Tehran: Boshra Tohfe Publishers; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 19.O’Connor AM. Validation of a decisional conflict scale. Med Decis Making. 1995;15:25–30. doi: 10.1177/0272989X9501500105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nagle C, Gunn J, Bell R, Lewis S, Meiser B, Metcalfe S, et al. Use of a decision aid for prenatal testing of fetal abnormalities to improve women's informed decision making: A cluster randomised controlled trial. BJOG. 2008;115:339–47. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01576.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mathieu E, Barratt A, Davey HM, McGeechan K, Howard K, Houssami N. Informed choice in mammography screening: A randomized trial of a decision aid for 70-year-old women. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:2039–46. doi: 10.1001/archinte.167.19.2039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Smith SK, Trevena L, Simpson JM, Barratt A, Nutbeam D, McCaffery KJ. A decision aid to support informed choices about bowel cancer screening among adults with low education: Randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2010;341:c5370. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c5370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schoonen M. Rotterdam: Netherlands Institute for Health Sciences; 2011. Prenatal Screening for Down Syndrome and for Structural Congenital Anomalies in the Netherlands: PhD Thesis. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arbabi HY. Education Health and Communications. Tehran: Boshra Publishers; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Skelly CL, Ulrich S. Enhancing informed choice for genetic screening: A pilot study. Nurs Health. 2014;2:126–30. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yee LM, Wolf M, Mullen R, Bergeron AR, Cooper Bailey S, Levine R, et al. A randomized trial of a prenatal genetic testing interactive computerized information aid. Prenat Diagn. 2014;34:552–7. doi: 10.1002/pd.4347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Michie S, Smith D, Marteau TM l. Patient decision making: An evaluation of two different methods of presenting information about a screening test. Br J Health Psychol. 1997;2:317–26. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Stefansdottir V, Skirton H, Jonasson K, Hardardottir H, Jonsson JJ. Effects of knowledge, education, and experience on acceptance of first trimester screening for chromosomal anomalies. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2010;89:931–8. doi: 10.3109/00016341003686073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hewison J, Cuckle H, Baillie C, Sehmi I, Lindow S, Jackson F, et al. Use of videotapes for viewing at home to inform choice in Down syndrome screening: A randomised controlled trial. Prenat Diagn. 2001;21:146–9. doi: 10.1002/1097-0223(200102)21:2<146::aid-pd3>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Toghyani R, Ramezani MA, Izadi M, Shahidi S, Aghdak P, Motie Z, et al. The effect of prenatal care group education on pregnant mothers’ knowledge, attitude and practice. Iran J Med Educ. 2008;7:317–24. [Google Scholar]

- 31.O’Connor AM, Jacobsen MJ. Decisional Conflict: Assessing and Supporting Patient Experiencing Uncertainty About Decisions Affecting their Health, Ottawa. 1998 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaiser AS, Ferris LE, Katz R, Pastuszak A, Llewellyn-Thomas H, Johnson JA, et al. Psychological responses to prenatal NTS counseling and the uptake of invasive testing in women of advanced maternal age. Patient Educ Couns. 2004;54:45–53. doi: 10.1016/S0738-3991(03)00190-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hunter AG, Cappelli M, Humphreys L, Allanson JE, Chiu TT, Peeters C, et al. A randomized trial comparing alternative approaches to prenatal diagnosis counseling in advanced maternal age patients. Clin Genet. 2005;67:303–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Petersen JJ, Paulitsch MA, Guethlin C, Gensichen J, Jahn A. A survey on worries of pregnant women – Testing the German version of the Cambridge worry scale. BMC Public Health. 2009;9:490. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-9-490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Guidelines for maternity providers offering antenatal screening for Down syndrome and other conditions in New Zealand. Wellington, National Screening Unit. 2009. [Last accessed on 2016 Feb 12]. Available at: http://www.nsu.govt.nz .

- 36.Mohammadi N, Tizhosh M, Seyedoshohadaye M, Haghani H. Comparison of effect of group and individual training on consciousness and anxiety in patients hospitalized for coronary angiography. J Nurs Midwifery Tehran Univ Med Sci. 2012;18:44–53. [Google Scholar]