Abstract

Background

The built environment influences behaviour, like physical activity, diet and sleep, which affects the risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). This study systematically reviewed and meta-analysed evidence on the association between built environmental characteristics related to lifestyle behaviour and T2DM risk/prevalence, worldwide.

Methods

We systematically searched PubMed, EMBASE.com and Web of Science from their inception to 6 June 2017. Studies were included with adult populations (>18 years), T2DM or glycaemic markers as outcomes, and physical activity and/or food environment and/or residential noise as independent variables. We excluded studies of specific subsamples of the population, that focused on built environmental characteristics that directly affect the cardiovascular system, that performed prediction analyses and that do not report original research. Data appraisal and extraction were based on published reports (PROSPERO-ID: CRD42016035663).

Results

From 11,279 studies, 109 were eligible and 40 were meta-analysed. Living in an urban residence was associated with higher T2DM risk/prevalence (n = 19, odds ratio (OR) = 1.40; 95% CI, 1.2–1.6; I2 = 83%) compared to living in a rural residence. Higher neighbourhood walkability was associated with lower T2DM risk/prevalence (n = 8, OR = 0.79; 95% CI, 0.7–0.9; I2 = 92%) and more green space tended to be associated with lower T2DM risk/prevalence (n = 6, OR = 0.90; 95% CI, 0.8–1.0; I2 = 95%). No convincing evidence was found of an association between food environment with T2DM risk/prevalence.

Conclusions

An important strength of the study was the comprehensive overview of the literature, but our study was limited by the conclusion of mainly cross-sectional studies. In addition to other positive consequences of walkability and access to green space, these environmental characteristics may also contribute to T2DM prevention. These results may be relevant for infrastructure planning.

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12916-017-0997-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

Keywords: Built environment, Type 2 diabetes mellitus, Lifestyle behaviour, Prevention, Urbanisation

Background

Key risk factors for type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) are lack of physical activity, an unhealthy diet and lack of sleep [1, 2]. Real-life T2DM prevention programmes aimed at changing people’s lifestyle and behaviour have often been ineffective in the long term [3]. An important reason for this may be the focus on individual-level determinants of these lifestyle behaviours, such as motivation and ability, whereas they are also determined by more upstream drivers, such as the availability and accessibility of healthy options in an individual’s environment. In terms of changing and sustaining healthy lifestyle behaviours, the built environment is of importance [4–7].

Urbanisation is one example of an upstream driver. Urbanisation is associated with lower total physical activity and increased consumption of processed foods, which are high in fat, added sugars, animal products and refined carbohydrates [4, 8]. However, urbanisation has also been linked to higher total walking and cycling for transportation [4]. Built environmental characteristics, such as higher walkability, access to parks, and access to shops and services, are consistently associated with higher physical activity [4, 5]. Food built environmental characteristics, such as the perceived availability of healthy foods, are also associated with higher diet quality. In addition, greater availability of fast-food outlets has been associated with lower fruit and vegetable consumption [9, 10]. Other built environmental characteristics have been associated with higher stress and lack of sleep through residential noise, e.g. noise due to road and air traffic [11, 12].

By influencing physical activity, diet and sleep, these built environmental characteristics may also affect the risk/prevalence of T2DM. Indeed, the diabetes atlas showed higher T2DM prevalence in urban vs. rural areas [8], and a recent systematic meta-analysis reported similar results for South East Asia [13]. Two other systematic reviews addressed the association between specific built environmental characteristics and T2DM [14, 15]. However, one review only included German studies [14], while the second review included a broad range of cardiovascular disease outcomes, but only one study was included that considered T2DM as an outcome [15]. A recent meta-analysis showed that higher residential noise was associated with higher T2DM risk [16].

A comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis of the current international evidence is, thus, lacking. This study aims to review systematically the evidence on the association between built environmental characteristics related to lifestyle behaviours and T2DM risk or prevalence, worldwide. Since characteristics of the built environment may vary with the country-specific income level, we stratified our analyses by this factor when possible. Meta-analyses were performed when three or more studies investigated the same exposure and outcome.

Methods

Data sources and searches

A literature search was performed based on the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) statement (www.prisma-statement.org). We systematically searched the bibliographic databases PubMed, EMBASE.com and Web of Science Core Collection from their inception to 6 June 2017 (NdB and LS). Search terms included indexed terms from MeSH in PubMed, EMtree in EMBASE.com, as well as free-text terms. We used free-text terms only in Web of Science. Search terms expressing ‘diabetes’ were used in combination with search terms comprising ‘environment’. Bibliographies of the identified articles were hand-searched for relevant publications. Duplicate articles were excluded. The full search strategies for all databases can be found in Additional file 1. The protocol and search strategy used were uploaded to PROSPERO prior to the study being carried out (CRD42016035663).

Study selection

Two reviewers independently screened titles, abstracts and full-text articles for eligibility (NdB and JL, or JWJB). Studies were included if they: (i) studied a population of adults, 18 years or older; (ii) had T2DM incidence or prevalence, or the glycaemic markers HbA1c, glucose or insulin sensitivity as outcomes; (iii) included independent variables covering built environmental characteristics that potentially influence the risk of T2DM via lifestyle behaviours, physical activity, diet and sleep; and (iv) were written in English, Dutch or German. We excluded studies if they: (i) were not conducted in the general population, but in specific subsamples, like pregnant women, or T2DM patients; (ii) focused on built environmental characteristics that directly affect the cardiovascular system (i.e. not via lifestyle behaviours), such as exposure to particulates due to roadway proximity; (iii) performed prediction analyses or (iv) were specific publication types that do not report original scientific research (editorials, letters, legal cases and interviews). As in the general population, the vast majority of diabetes cases are T2DM (>90%), studies were included if they did not specify the type of diabetes (type 1 diabetes mellitus or T2DM). Inconsistencies in study selection were resolved through consensus with a third reviewer (JL or JWJB).

Data extraction

One reviewer (NdB) performed data extraction, according to a standard protocol, including measures of study design, outcome, outcome assessment and exposure assessment, demographics, and prevalence or effect measure. Data extraction was appraised by a second reviewer (JL) for a random subsample of the included studies.

Quality assessment

Two reviewers (NdB and JWJB, or JL) independently evaluated the methodological quality of the full-text papers using the Quality Assessment Tool for Quantitative Studies, as described earlier by Mackenbach et al. [17]. This tool provides a quality score based on study design, representativeness at baseline (selection bias) and follow-up (withdrawals and drop-outs), confounders, data collection, data analysis and reporting. Each domain received a weak, moderate or strong score, resulting in seven scores. A study was rated as strong when it received four strong ratings and no weak ratings. A study was rated as moderate if it received one weak rating and less than four strong ratings. Finally, a study was rated weak if it received two or more weak ratings. Study quality was assessed in terms of the reported association between the relevant built environmental characteristic and T2DM, even if this was not the primary analysis presented in the study. Studies with a weak rating (n = 23) are presented in Additional file 2 and were included in sensitivity analyses, but excluded from the main analyses.

Data synthesis

Study characteristics were described in a systematic manner, according to the built environmental characteristics under investigation. These categories were made as homogeneous as possible, based on the lifestyle behaviours. Findings were further described according to country-level income, based on the World Bank list of economies, 2016 [18].

Studies were meta-analysed when three or more studies investigated the same exposure and outcome variables. In addition, the studies had to provide at least age and sex adjusted or standardised risk ratios or prevalence, and have a moderate or strong quality rating. If reported ratios were stratified and could not be pooled with the information provided in the publication, the study’s authors were contacted and asked to provide the pooled-risk ratio [19–23]. Reference categories were harmonised by taking the inverse of the risk ratio and 95% confidence interval (CI). If a risk ratio for a continuous variable was reported, we transformed this to a categorical risk ratio based on the methods of Danesh et al. [24]. Forest plots and random-effects meta-analysis models were fitted to relative risks or odds ratios. Plots and models were stratified for country income level and study quality, where permitted. In the sensitivity analyses, the studies with weak quality ratings were added to the models. Heterogeneity was tested using I2. Analyses were performed in R version 3.2.5 using the Metafor package.

Results

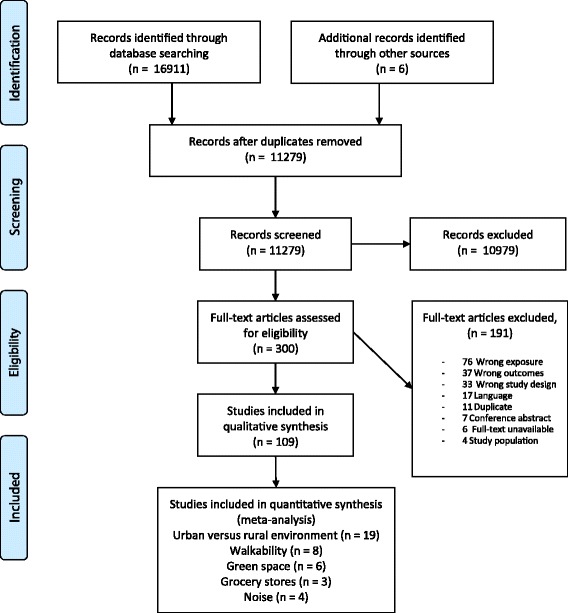

From the 11,279 identified references, 299 full articles were screened, and 109 of these studies were included in our review, of which 23 were not included in our main analyses due to a weak quality rating (Fig. 1 and Additional file 2). Included studies were categorised according to the built environmental characteristic investigated (Tables 1 and 2), and built environments were subdivided by physical activity environment, food environment and residential noise (Table 2).

Fig. 1.

Flow chart of study inclusion

Table 1.

Study characteristics and results of studies investigating the association between urban and rural built environments and diabetes mellitus

| Author | Year | Country | Country income level | Study design | Sample size | Age | Outcomea | Outcome assessmentb | Result | Adjustment for confounding | Quality statement | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban > rural | Rural > urban | No difference | |||||||||||

| Aekplakorn et al. [89] | 2011 | Thailand | Upper middle | Cross-sectional | 18,629 | NFG: 44.3 ± 0.3 Diabetes mellitus: 54.1 ± 0.7 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex | Moderate | ||

| Agyemang et al. [90] | 2016 | Ghana, Netherlands, Germany, England | Lower middle and high | Cross-sectional | 5659 | 25–70 years (NR) | T2DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex, education | Moderate | ||

| Ali et al. [91] | 1993 | Malaysia | Upper middle | Cross-sectional | 681 | 38.6 ± 13.7 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age | Moderate | ||

| Al-Moosa et al. [92] | 2006 | Oman | High | Cross-sectional | 5840 | 24% >50 years 41% < 30 years | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | – | Moderate | ||

| Anjana et al. [93] | 2011 | India | Lower middle | Cross-sectional | 13,055 | 40 ± 14 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | Southern area, western area, eastern area | Northern area | Age, sex | Moderate | |

| Assah et al. [94] | 2011 | Cameroon | Lower middle | Cross-sectional | 552 | 38.4 ± 8.6 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | – | Moderate | ||

| Attard et al. [67] | 2012 | China | Upper middle | Cross-sectional | NA | 51 ± 0.4 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample, self-report | X | Age, sex, income, region, BMI | Strong | ||

| Allender et al. [95] | 2011 | Sri Lanka | Lower middle | Cross-sectional | 4485 | 46.1 ± 15.1 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex, income | Moderate | ||

| Bahendeka et al. [41] | 2016 | Uganda | Low | Cross-sectional | 3689 | 35.1 ± 12.6 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex, region of residence, floor finishing of dwelling, BMI, waist circumference, total cholesterol | Moderate | ||

| Baldé et al. [96] | 2007 | Guinea | Low | Cross-sectional | 1537 | 47.7 ± 12.5 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, location, excess of waist, raised systolic BP, raised diastolic BP | Moderate | ||

| Balogun et al. [97] | 2012 | Nigeria | Lower middle | Longitudinal | 1330 | 77.3 ± 0.3 | T2DM incidence | Self-report | X | Age, sex, education | Strong | ||

| Baltazar et al. [98] | 2003 | Philippines | Lower middle | Cross-sectional | 7044 | 39.0 ± 0.5 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age and sex | Moderate | ||

| Barnabé-Ortiz [99] | 2016 | Peru | Upper middle | Longitudinal | 3123 | 24% < 45 years 25% >65 years | T2DM incidence | Blood sample | X | Sex, age, education level, SES, family history of diabetes, daily smoking, hazardous drinking, TV watching for 2+ hours per day, transport-related physical inactivity, fruit and vegetable consumption, BMI, metabolic syndrome | Moderate | ||

| Bocquier et al. [100] | 2010 | France | High | Cross-sectional | 3,038,670 | 48.9 ± 18.6 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Secondary | X | Age, sex | Strong | ||

| Cubbin et al. [23] | 2006 | Sweden | High | Cross-sectional | 18,081 | 48% >45 years 25% < 35 years | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Self-report | X | Age, sex, marital status, immigration status, SES composite, neighbourhood deprivation | Moderate | ||

| Christensen et al. [101] | 2009 | Kenya | Lower middle | Cross-sectional | 1459 | 38.6 ± 12.6 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex | Moderate | ||

| Dagenais et al. [102] | 2016 | Bangladesh, India, Pakistan, Zimbabwe, China, Colombia, Iran, Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Malaysia, Poland, South Africa, Turkey, Canada, Sweden, United Arab Emirates | Lower, lower middle, upper middle and high | Cross-sectional | 119,666 | 52 ± 9.3 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex, residency location, BMI, waist-to-hip ratio, PA levels, AHEI score, combined former and current smoking, education level, family history of diabetes, ethnicity | Strong | ||

| Dar et al. [25] | 2015 | India | Lower middle | Cross-sectional | 3972 | 43% >50 years 57% 40–50 years | T2DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | – | Weak | ||

| Davila et al. [103] | 2013 | Colombia | Upper middle | Cross-sectional | 1026 | 35% >55 years 35% < 35 years | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex, education, SES, marital status, smoking, alcohol, intake of fruit and vegetables, PA | Strong | ||

| Delisle et al. [104] | 2012 | Benin | Low | Cross-sectional | 541 | 38.2 ± 0.6 | Glycaemic marker: HOMA index | Blood sample | X | Age, sex, SES, location, diet quality, PA, alcohol, BMI | Moderate | ||

| Dong et al. [105] | 2005 | China | Upper middle | Cross-sectional | 12,240 | 46.4 ± 13.9 | T2DM prevalence | Blood sample | X (men) | X (women) | Age, sex | Moderate | |

| Du et al. [106] | 2016 | China | Upper middle | Cross-sectional | 3797 | 15% >60 years 8% 20–29 years | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex | Moderate | ||

| Esteghamati et al. [107] | 2009 | Iran | Upper middle | Cross-sectional | 3397 | 23% >55 years 25% < 35 years | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex, residential area | Moderate | ||

| Georgousopoulou et al. [108] | 2017 | Mediterranean islands | High | Cross-sectional | 2749 | 75 ± 7.3 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex, BMI, physical inactivity, smoking, siesta habit, education, living alone, adherence to Mediterranean diet, GDS, number of friends and family members, frequency of going out with friends and family, number of holiday excursions per year | Moderate | ||

| Gong et al. [109] | 2015 | China | Upper middle | Cross-sectional | 5923 | 38% >50 years 62% < 50 years | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex, education, PA, smoking, alcohol, BMI, triglycerides, HDL-cholesterol, hypertension | Strong | ||

| Hussain et al. [110] | 2004 | Bangladesh | Lower middle | Cross-sectional | 6312 | 14% >50 years 46% < 30 years | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex | Moderate | ||

| Han et al. [111] | 2017 | Korea | High | Longitudinal | 7542 | 52 ± 8.8 | T2DM incidence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex, residential area, family history of diabetes, smoking, alcohol, exercise, abdominal obesity, hypertension, high triglycerides, low HDL-cholesterol | Strong | ||

| Katchunga et al. [112] | 2012 | Congo | Low | Cross-sectional | 699 | 42.5 ± 18.1 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | – | Moderate | ||

| Keel et al. [113] | 2017 | Australia | High | Cross-sectional | 4836 | Non-indigenous: 66.6 ± 9.7 Indigenous: 54.9 ± 8.7 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Self-report | X (indigenous) | X (non-indigenous) | Age, sex, ethnicity, education, English-speaking at home, ethnicity | Moderate | |

| Mayega et al. [114] | 2013 | Uganda | Low | Cross-sectional | 1497 | 45.8% >45 years 54.2% < 45 years | T2DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex, residence, occupation, family history of diabetes, BMI, PA level, dietary diversity | Strong | ||

| Mohan et al. [115] | 2016 | India | Lower middle | Cross-sectional | 6853 | 35–70 years (NR) | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age (only women included) | Moderate | ||

| Msyamboza et al. [116] | 2014 | Malawi | Low | Cross-sectional | 3056 | 12.5% >55 years 45% < 35 years | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex | Moderate | ||

| Ntandou et al. [117] | 2009 | Benin | Low | Cross-sectional | 541 | 38.2 ± 10 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex, waist circumference, education, SES, PA, micronutrient adequacy score, preventive diet score, alcohol | Moderate | ||

| Oyebode et al. [118] | 2015 | China, Ghana, India, Mexico, Russia, South Africa | Upper and Lower middle | Cross-sectional | 39,436 | 47.3% >60 years 12.3% < 40Y | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Self-report | X (pooled) | Age, sex, survey design, income quintile, marital status, education | Strong | ||

| Papoz et al. [119] | 1996 | New Caledonia | High | Cross-sectional | 9390 | 30–59 years (NR) | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age | Moderate | ||

| Pham et al. [120] | 2016 | Vietnam | Lower middle | Cross-sectional | 16,730 | 54 ± 8 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X (men) | X (women) | Age, sex, socio-demographic factors, anthropometric measures, BP, family history of diabetes | Moderate | |

| Raghupathy et al. [121] | 2007 | India | Lower middle | Longitudinal | 2218 | 28 ± 1.2 | T2DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex, number of household possessions, education, PA, smoking, alcohol, parental consanguinity, family history of diabetes mellitus, body fat, BMI, waist-to-hips ratio, subscapular/triceps ratio | Strong | ||

| Ramdani et al. [122] | 2012 | Morocco | Lower middle | Cross-sectional | 1628 | 54.2 ± 10.9 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex, BMI | Moderate | ||

| Sadikot et al. [123] | 2004 | India | Lower middle | Cross-sectional | 41,270 | 36% >50 years 34% < 40 years | T2DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex | Moderate | ||

| Sobngwi et al. [124] | 2004 | Cameroon | Lower middle | Longitudinal | 1726 | 24% >55 years 28% < 35 years | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X (women) | X (men) | Age, sex, residence, socio-professional category, alcohol, smoking, PA | Moderate | |

| Stanifer et al. [125] | 2016 | Tanzania | Low | Cross-sectional | 481 neighbourhoods | 25% >60 years | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex | Moderate | ||

| Weng et al. [126] | 2007 | China | Upper middle | Cross-sectional | 529 | NR | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age, sex | Moderate | ||

| Wu et al. [127] | 2016 | China | Upper middle | Cross-sectional | 23,010 | 40 (30.4–56.3) | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | X | Age | Moderate | ||

| Zhou et al. [128] | 2015 | China | Upper middle | Cross-sectional | 98,658 | 20% >60 years 80% < 60 years | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | X | Age, sex, region | Moderate | |||

BMI body mass index, BP blood pressure, NR not recorded, PA physical activity, SES socioeconomic status, T1DM type 1 diabetes mellitus, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus, NFG normal fasting glucose, HOMA homeostasis model assessment, GDS geriatric depression scale

aPrevalence indicates incidence or glycaemic marker level

bBlood sample: study diagnosed diabetes based on glycaemic marker or oral glucose tolerance test; secondary: from data sources such as national health survey; self-report: ever diagnosed with diabetes

Table 2.

Study characteristics of studies investigating physical activity environment, food environment, residential noise and diabetes mellitus

| Author | Year | Country | Income level | Study design | Sample size | Age | Outcomea | Outcome assessmentb | Exposure category | Exposure assessment | Level geodata | Quality statement |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahern et al. [46] | 2011 | US | High | Cross-sectional | 3128 | NR | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Secondary | PA, food | Place of residence | Aggregate | Moderate |

| AlHasan et al. [69] | 2016 | US | High | Cross-sectional | NA | NR | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Secondary | Food | GIS | Aggregate | Strong |

| Astell-Burt et al. [42] | 2014 | Australia | High | Cross-sectional | 48,072 | 28% 45–55 years 39% >65 years | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Self-report | PA | GIS | Individual | Moderate |

| Auchincloss et al. [47] | 2009 | US | High | Longitudinal | 2285 | 62.1 ± 10 | T2DM incidence | Blood sample, self-report | PA, food | Self-report | Individual | Moderate |

| Bodicoat et al. [44] | 2014 | UK | High | Cross-sectional | 10,476 | 59 ± 10.4 | T2DM prevalence | Secondary (screen detected) | PA | GIS | Individual | Strong |

| Bodicoat et al. [72] | 2015 | UK | High | Cross-sectional | 10,461 | 59 ± 10.4 | T2DM prevalence | Secondary (screen detected) | Food | GIS | Individual | Strong |

| Booth et al. [19] | 2013 | Canada | High | Longitudinal | 1,024,380 | 30–64 years (NR) | T2DM/T1DM incidence | Secondary | PA | Moderate | ||

| Braun et al. [80] | 2015 | US | High | Cross-sectional | NA | NR | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Secondary | PA, food | Register | Aggregate | Moderate |

| Braun et al. [58] | 2016 | US | High | Longitudinal | 1079 | 39.7 ± 3.7 | Glycaemic marker: ln(HOMA index) | Blood sample | PA | GIS | Individual | Strong |

| Braun et al. [57] | 2016 | US | High | Longitudinal | 583 | 69.4 ± 9.5 | Glycaemic marker: fasting glucose | Blood sample | PA | GIS | Individual | Strong |

| Cai et al. [82] | 2017 | Netherlands | High | Cross-sectional | 93,277 | 44.9 ± 12.3 | Glycaemic marker: fasting glucose | Blood sample | Noise | GIS | Aggregate | Strong |

| Carroll et al. [71] | 2017 | Australia | High | Longitudinal | 2582 | 50 ± 15 | Glycaemic marker: HbA1c | Blood sample | Food | GIS | Aggregate | Moderate |

| Christine et al. [48] | 2015 | US | High | Longitudinal | 2157 | 60.7 ± 9.9 | T2DM incidence | Blood sample | PA, food | GIS, self-report | Individual | Strong |

| Creatore et al. [20] | 2016 | Canada | High | Longitudinal | ±4,505,000 | 61% 30–49 years 34% 50–65 years | T2DM/T1DM incidence | Secondary | PA | GIS | Aggregate | Strong |

| Cunningham-Myrie et al. [49] | 2015 | Jamaica | Upper middle | Cross-sectional | 2848 | 36.9 ± 2.7 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | PA | Environmental audit | Individual | Strong |

| Dalton et al. [59] | 2016 | UK | High | Longitudinal | 23,865 | 59.1 ± 9.3 | T2DM/T1DM incidence | Self-report | PA | GIS | Individual | Strong |

| Dzhambov et al. [83] | 2016 | Bulgaria | Upper middle | Cross-sectional | 581 | 36.5 ± 15.4 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Secondary | Noise | Secondary | Aggregate | Moderate |

| Eichinger et al. [50] | 2015 | Austria | High | Cross-sectional | 660 | 47.1 ± 14.1 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | PA | Self-report | Individual | Moderate |

| Eriksson et al. [85] | 2014 | Sweden | High | Longitudinal | 5156 | 47 ± 5 | T2DM incidence | Blood sample | Noise | GIS | Individual | Moderate |

| Flynt et al. [73] | 2015 | US | High | Cross-sectional | NA | NR | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Secondary | Food | Secondary | Aggregate | Moderate |

| Frankenfeld et al. [74] | 2015 | US | High | Cross-sectional | 3227 | 11% >65 years 75% >18 years | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | Food | GIS | Aggregate | Moderate |

| Freedman et al. [68] | 2011 | US | High | Cross-sectional | NA | 100% >50 years | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Self-report | PA, food | Secondary | Aggregate | Moderate |

| Fujiware et al. [60] | 2017 | Japan | High | Cross-sectional | 8904 | 72.5 ± 5.2 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | PA, food | GIS | Individual | Moderate |

| Gebreab et al. [61] | 2017 | US | High | Longitudinal | 3661 | 54 ± 12 | T2DM incidence | Blood sample | PA, Food | GIS | Individual | Strong |

| Glazier et al. [21] | 2014 | Canada | High | Cross-sectional | 2,446,029 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Secondary | PA | GIS | Aggregate | Moderate | |

| Hipp et al. [78] | 2015 | US | High | Cross-sectional | 3109 counties | T2D prevalence | Secondary | Food | GIS | Aggregate | Moderate | |

| Heideman et al. [86] | 2014 | Germany | High | Longitudinal | 3604 | 44.8 ± 13.7 | T2DM incidence | Secondary | Noise | Self-report | Individual | Strong |

| Lee et al. [45] | 2015 | Korea | High | Cross-sectional | 13,478 | 47.6 ± 12.2 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Secondary | PA | GIS | Aggregate | Moderate |

| Liu et al. [79] | 2014 | US | High | Cross-sectional | 17,254 | 46.5 ± 18.5 | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | PA, food | Self-report | Individual | Strong |

| Loo et al. [62] | 2017 | Canada | High | Cross-sectional | 78,023 | 35% 18–40 years 23% >65 years | Glycaemic marker: HbA1c and fasting glucose | Blood sample | PA | GIS | Individual | Strong |

| Maas et al. [66] | 2009 | Netherlands | High | Cross-sectional | 345,103 | 38% >45 years 63% < 45 years | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Secondary | PA | Register | Individual | Moderate |

| Mena et al. [53] | 2015 | Chile | High | Cross-sectional | 832 | 45 ± 14 | Glycaemic marker: Fasting glucose level | Blood sample | PA, food | GIS | Individual | Moderate |

| Meyer et al. [81] | 2015 | US | High | Longitudinal | 14,379 (observations) | 45.2 ± 3.6 | Glycaemic marker: HOMA index | Blood sample | PA, food | GIS | Individual | Moderate |

| Mezuk et al. [70] | 2016 | Sweden | High | Longitudinal | 2,948,851 | NR | T2DM incidence | Secondary | Food | GIS | Individual | Strong |

| Morland et al. [75] | 2006 | US | High | Cross-sectional | 10,763 | 100% >50 years | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Blood sample | Food | GIS | Aggregate | Moderate |

| Müller-Riemenschneider et al. [65] | 2013 | Australia | High | Cross-sectional | 5970 | 29% >65 years 30% < 45 years | T2DM prevalence | Self-report | PA | GIS | Individual | Strong |

| Myers et al. [63] | 2016 | US | High | Cross-sectional | NA | NR | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Secondary | PA, food | Secondary | Aggregate | Moderate |

| Ngom et al. [64] | 2016 | Canada | High | Cross-sectional | 3,920,000 | NR | T2DM/T1DM prevalence | Secondary | PA | GIS | Aggregate | Strong |

| Paquet et al. [54] | 2014 | Australia | High | Longitudinal | 3145 | 51.5 ± 15.5 | T2DM incidence | Blood sample | PA, food | GIS | Individual | Moderate |

| Schootman et al. [56] | 2007 | US | High | Longitudinal | 644 | 56.2 ± 4.3 | T2DM/T1DM incidence | Self-report | PA, noise | Self-report, environmental audit | Individual | Moderate |

| Sørensen et al. [84] | 2013 | Denmark | High | Longitudinal | 57,053 | 56.1 (50.7–64.2) | T2DM/T1DM incidence | Secondary | Noise | GIS | Individual | Moderate |

| Sundquist et al. [22] | 2015 | Sweden | High | Longitudinal | 512,061 | 55 ± 14.9 | T2DM incidence | Secondary | PA | GIS | Aggregate | Moderate |

GIS geographic information systems, NA not applicable, NR not recorded, PA physical activity, T1DM type 1 diabetes mellitus, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus

aPrevalence is incidence or glycaemic marker level

bBlood sample: study diagnosed diabetes based on glycaemic marker or oral glucose tolerance test; secondary: from data sources such as national health survey; self-report: ever diagnosed with diabetes

Sixty studies compared T2DM risk/prevalence in urban vs. rural environments (Table 1 and Additional file 2). The studies rated weak (n = 16) did not differ in terms of country income levels from the other studies [25–40].

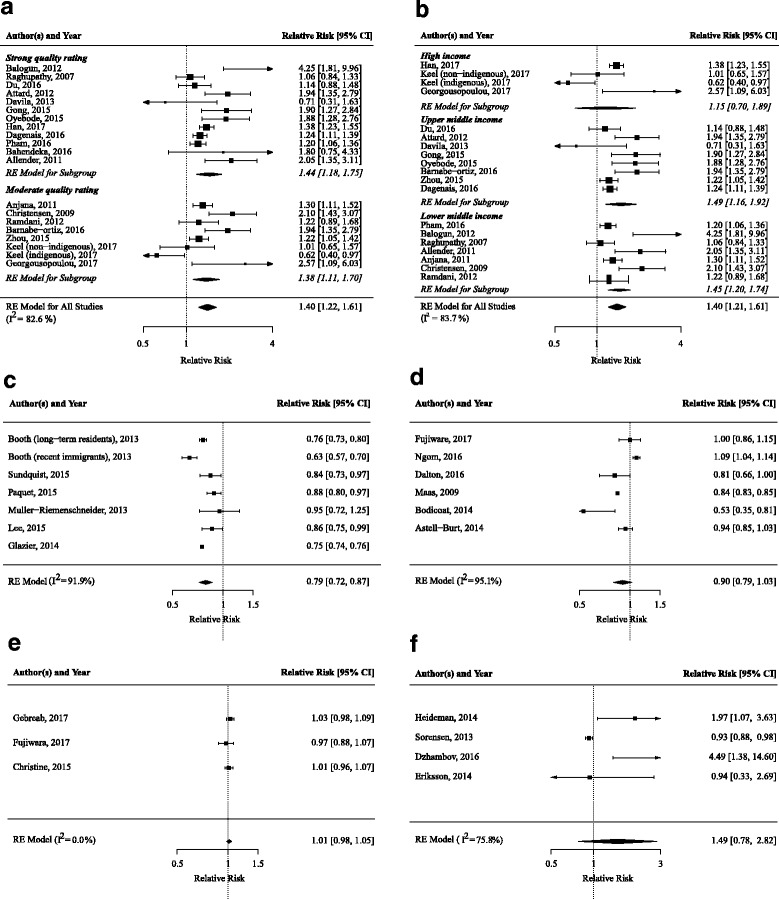

Of the remaining 44 studies, 25 (57%) of them found a higher risk or prevalence of T2DM in urban areas compared to rural areas. Altogether, 19 studies were eligible for the meta-analysis, which revealed a significantly higher risk/prevalence of T2DM in urban areas vs. rural areas (1.40; 95% CI, 1.22–1.61) (Fig. 2). This association was stronger in studies with strong quality ratings (1.44; 95% CI, 1.18–1.75), compared to those with moderate quality ratings (1.38; 95% CI, 1.11–1.70). After stratifying for country income level, one study was excluded [41] because the subgroup contained fewer than three studies. Associations were not different for upper-middle income countries (1.49; 95% CI, 1.16–1.92) and lower-middle income countries (1.45; 95% CI, 1.20–1.74), but were non-significant for high-income countries (1.16; 95% CI, 0.70–1.89).

Fig. 2.

Forest plots of meta-analysis of the association between built environmental characteristics and T2DM risk/prevalence. a Urban vs. rural environments, stratified for study quality. b Urban vs. rural environments, stratified for country income level. c Walkability. d Green space. e Grocery stores. f Noise. T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus. RE model random effects model

Sensitivity analyses that included studies with weak quality ratings [33, 40] did not significantly change the results (Additional file 3).

Thirty studies investigated physical activity environment [19–22, 42–64] (Fig. 1, Table 2 and Additional file 2). All studies were performed in high-income level countries, except for one, which was performed in an upper-middle-level-income country [49].

Ten studies investigated the association between neighbourhood walkability and T2DM risk/prevalence. Six studies received a strong quality rating [20, 48, 57, 58, 62, 65]. Six studies observed that highly walkable neighbourhoods were associated with a lower T2DM risk/prevalence [19–22, 45, 54, 65]. In the meta-analyses of six studies, a pooled-risk ratio of 0.79 (95% CI, 0.72–0.87) was found, with an I2 for heterogeneity of 91.9%.

Six studies investigated the association between facilities for physical activity and T2DM risk/prevalence. Three studies received a strong quality rating [48, 49, 61]. Four studies did not observe an association between density of facilities and T2DM risk/prevalence [46, 48, 49, 61]. In two other studies, the higher availability of neighbourhood resources for physical activity was associated with lower T2DM risk [47, 63].

Seven studies investigated the association between green space and T2DM risk/prevalence. Two studies received a strong quality rating [44, 59]. Four studies observed that a higher availability of green space was associated with lower T2DM risk/prevalence [44, 54, 59, 64, 66]. One study observed that living closer to parks was significantly associated with higher prevalence of T2DM [64]. Aanother study observed a non-significant lower risk [42]. In meta-analyses of six studies, more green space tended to be associated with lower T2DM risk/prevalence with a pooled-risk ratio of 0.90 (95% CI, 0.79–1.03) with I2 for heterogeneity of 95.1%.

Four studies investigated infrastructure in relation to T2DM risk/prevalence. Two studies received a strong quality rating [49, 67]. Four studies did not observe an association between connectivity, infrastructure and road quality and T2DM risk/prevalence [49, 56, 68]. One study observed that a better transportation infrastructure, defined as more paved roads, was associated with higher T2DM prevalence [67].

Four studies investigated the association between safety and T2DM risk/prevalence. One study received a strong rating [49]. None of the studies showed an association between either traffic safety or safety from crime and T2DM risk/prevalence [49, 50, 56].

Twenty studies investigated characteristics of the food environment [46–48, 51–55, 60, 61, 63, 69–77] (Fig. 1, Table 2 and Additional file 2). All studies were performed in high-income-level countries.

Eight studies investigated the association between supermarkets and grocery stores and T2DM risk/prevalence. Two studies received a strong quality rating [61, 69]. One study observed that greater availability of grocery stores was associated with lower T2DM prevalence and that a higher percentage of households without a car located far from a supermarket was associated with higher T2DM prevalence [46]. A second study observed an unadjusted correlation between a greater distance to markets and lower fasting glucose levels [53]. Five studies did not observe a significant association between availability of supermarkets/grocery stores and T2DM prevalence [60, 61, 63, 69, 71, 75]. In a meta-analysis of three studies [48, 60, 61], a higher density of grocery stores was not associated with T2DM risk/prevalence (1.01; 95% CI, 0.98–1.05; I2 = 0%).

Seven studies investigated the association between availability of fast-food outlets and convenience stores and T2DM risk/prevalence. Three studies received a strong quality rating [61, 69, 72]. Four studies did not observe an association between availability of fast-food outlets/convenience stores and T2DM prevalence [61, 63, 69, 71, 75]. A higher availability of fast-food outlets and convenience stores was associated with higher T2DM prevalence in two studies [46, 72]. Studies could not be meta-analysed because the studies did not investigate consistent outcomes (T2DM risk vs. markers).

Four studies investigated the healthiness of the food environment subjectively or as an index and the association with T2DM risk/prevalence. One study received a strong quality rating [48]. Two studies focused on the perceived availability of healthy foods, rather than objectively measured availability. One study observed greater self-reported availability of healthy food resources to be associated with lower T2DM risk [47]. The second study assessed perceived availability, objective availability and a combination of the two, of which only perceived availability was associated with a lower T2DM risk [48]. Another study found no association between the presence of food deserts and T2DM prevalence [78].

Three studies used a ratio of unhealthful food stores to more healthful food stores, such as the Relative Food Environment Index (RFEI), with a higher value indicating an unhealthier food environment. One study received a strong quality rating [70]. This study observed that a higher ratio, i.e. a relatively unhealthier food environment, was associated with a higher risk of T2DM. Two studies did not observe consistent associations between RFEI and T2DM risk [54, 74].

Six studies used composite measures of physical activity and food-related built environmental characteristics (Tables 2 and 3, and Additional file 4). One study received a strong quality rating [79]. A summary score indicating the presence of more healthy food resources and physical activity resources was associated with lower T2DM incidence [47]. Furthermore, residing in a neighbourhood with physical and social-environmental disadvantages was associated with higher T2DM prevalence [79]. Clusters of large metropolitan counties, characterised by low population density, median income, low socioeconomic status index and greater access to food observed less T2DM [73]. Finally, no association was observed between vibrancy index, density and obesogenicity clusters and T2DM risk/prevalence [68, 80, 81].

Table 3.

Study results of studies investigating physical activity environment, food environment, residential noise and diabetes mellitus

| Author | Exposure | Study result | 95% confidence interval or p value | Adjustment for confounding |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahern et al., 2011 [46] | Food environment: | Beta (SE) | Age, obesity rate | |

| 1. Percentage of households with no car living more than 1 mile from a grocery store | 1. 0.07 (0.01) | 1. P < 0.001 | ||

| 2. Fast-food restaurants per 1000 | 2. 0.41 (0.07) | 2. P < 0.001 | ||

| 3. Full service restaurants per 1000 | 3. -0.15 (0.04) | 3. P < 0.01 | ||

| 4. Grocery stores per 1000 | 4. -0.37 (0.09) | 4. P < 0.001 | ||

| 5. Convenience stores per 1000 | 5. 0.30 (0.06) | 5. P < 0.001 | ||

| 6. Direct money made from farm sales per capita | 6. -0.01 (0.02) | 6. P < 0.01 | ||

| PA environment: | ||||

| 7. Recreational facilities per 1000 | 7. -0.12 (0.21) | 7. NS | ||

| AlHasan et al., 2016 [69] | Food outlet density: | Beta (SE) | Age, obesity, PA, recreation facility density, unemployed, education, household with no cars and limited access to stores, race | |

| 1. Fast-food restaurant density per 1000 residents | 1. -0.55 (0.90) | 1. NS | ||

| 2. Convenience store density | 2. 0.89 (0.86) | 2. NS | ||

| 3. Super store density | 3. -0.4 (11.66) | 3. NS | ||

| 4. Grocery store density | 4. -3.7 (2.13) | 4. NS | ||

| Astell-Burt et al., 2014 [42] | Green space (percent): | OR: | Age, sex, couple status, family history, country of birth, language spoken at home, weight, psychological distress, smoking status, hypertension, diet, walking, MVPA, sitting, economic status, annual income, qualifications, neighbourhood affluence, geographic remoteness | |

| 1. >81 | 1. 0.94 | 1. 0.85–1.03 | ||

| 2. 0–20 | 2. 1 | 2. NA | ||

| Auchincloss et al., 2009 [47] | Neighbourhood resources: | HR: | Age, sex, family history, income, assets, education, ethnicity, alcohol, smoking, PA, diet, BMI | |

| 1. Healthy food resources | 1. 0.63 | 1. 0.42–0.93 | ||

| 2. PA resources | 2. 0.71 | 2. 0.48–1.05 | ||

| 3. Summary score | 3. 0.64 | 3. 0.44–0.95 | ||

| Bodicoat et al., 2014 [44] | Green space (percent) | OR: | Age, sex, area social deprivation score, urban/rural status, BMI, PA, fasting glucose, 2 h glucose, total cholesterol | |

| 1. Least green space (Q1) | 1. 1 | 1. NA | ||

| 2. Most green space (Q4) | 2. 0.53 | 2. 0.35–0.82 | ||

| Bodicoat et al., 2015 [72] | OR: | Age, sex, area social deprivation score, urban/rural status, ethnicity, PA | ||

| 1. Number of fast-food outlets (per 2) | 1. 1.02 | 1. 1.00–1.04 | ||

| 2. Density of fast-food outlet (per 200 residents) | 2. 13.84 | 2. 1.60–119.6 | ||

| Booth et al., 2013 [19] | Walkability: | HR: | Age, sex, income | |

| Men | ||||

| Recent immigrants | ||||

| 1. Least walkable quintile | 1. 1.58 | 1. 1.42–1.75 | ||

| 2. Most walkable quintile | 2. 1 | 2. NA | ||

| Long-term residents | ||||

| 1. Least walkable quintile | 1. 1.32 | 1. 1.26–1.38 | ||

| 2. Most walkable quintile | 2. 1 | 2. NA | ||

| Women | ||||

| Recent immigrants | ||||

| 1. Least walkable quintile | 1. 1.67 | 1. 1.48–1.88 | ||

| 2. Most walkable quintile | 2. 1 | 2. NA | ||

| Long-term residents | ||||

| 1. Least walkable quintile | 1. 1.24 | 1. 1.18–1.31 | ||

| 2. Most walkable quintile | 2. 1 | 2. NA | ||

| Braun et al., 2016 [57, 58] | Walkability index, after residential relocation | Beta (SE) | 1. Income, household size, marital status, employment status, smoking status, health problems that interfere with PA 2. Additionally, adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity, education | |

| 1. Fixed-effects model | 1. -0.011 (0.015) | 1. P > 0.05 | ||

| 2. Random-effects model | 2. -0.016 (0.010) | 2. P > 0.05 | ||

| Braun et al., 2016 [57, 58] | Walkability: within person change in Street Smart Walk Score | Beta (SE): 0.999 (0.002) | P > 0.05 | Age, sex, ethnicity, education, householdincome, employment status, marital status, neighbourhood SES |

| Cai et al., 2017 [82] | Daytime noise (dB) | Percentage change in fasting glucose per IQR Daytime noise: 0.2 | 95% CI, 0.1–0.3 P < 0.05 |

Age, sex, season of blood draw, smoking status and pack-years, education, employment, alcohol consumption, air pollution |

| Carroll et al., 2017 [71] | Count of fast-food outlets: | Beta per SD change: − 0.0094 |

-0.030–0.011 | Age, sex, marital status, education, employment status, smoking status |

| 1. Interaction with overweight/obesity | 1. −0.002 | 1. -0.023–0.019 | ||

| 2. Interaction with time | 2. 0.0003 | 2. -0.003–0.004 | ||

| 3. Interaction with time and overweight/obesity | 3. -0.002 | 3. -0.006–0.001 | ||

| Count of healthful food resources: | 0.012 | -0.008–0.032 | ||

| 4. Interaction with overweight/obesity | 4. 0.021 | 4. -0.000–0.042 | ||

| 5. Interaction with time | 5. -0.003 | 5. -0.006–0.001 | ||

| 6. Interaction with time and overweight/obesity | 6. -0.006 | 6. -0.009–-0.002 | ||

| Christine et al., 2015 [48] | Neighbourhood physical environment, diet related: | HR: | Age, sex, family history, household per capita income, educational level, smoking, alcohol, neighbourhood SES | |

| 1. Density of supermarkets and/or fruit and vegetable markets (GIS) | 1. 1.01 | 1. 0.96–1.07 | ||

| 2. Healthy food availability (self-report) | 2. 0.88 | 2. 0.78–0.98 | ||

| 3. GIS and self-report combined measure | 3. 0.93 | 3. 0.82–1.06 | ||

| Neighbourhood physical environment, PA related: | ||||

| 1. Density of commercial recreational facilities (GIS) | 1. 0.98 | 1. 0.94–1.03 | ||

| 2. Walking environment (self-report) | 2. 0.80 | 2. 0.70–0.92 | ||

| 3. GIS and self-report combined measure | 3. 0.81 | 3. 0.68–0.96 | ||

| Creatore et al., 2016 [20] | Walkability: | Absolute incidence rate difference over 12 years FU: | Age, sex, area income, ethnicity | |

| 1. Low walkable neighbourhoods (Q1) | 1. -0.65 | 1. -1.65–0.39 | ||

| 2. High walkable neighbourhoods over (Q5) | 2. - 1.5 | 2. -2.6– -0.4 | ||

| Cunningham-Myrie et al., 2015 [49] | Neighbourhood characteristics: | OR: | Age, sex, district, fruit and vegetable intake | |

| 1. Neighbourhood infrastructure | 1. 1.02 | 1. 0.95–1.1 | ||

| 2. Neighbourhood disorder score | 2. 0.99 | 2. 0.95–1.03 | ||

| 3. Home disorder score | 3. 1 | 3. 0.96–1.03 | ||

| 4. Recreational space in walking distance | 4. 1.12 | 4. 0.86–1.45 | ||

| 5. Recreational space availability | 5. 1.01 | 5. 0.77–1.32 | ||

| 6. Perception of safety | 6. 0.99 | 6. 0.88–1.11 | ||

| Dalton et al., 2016 [59] | Green space: | HR: | Age, sex, BMI, parental diabetes, SES Effect modification by urban-rural status and SES was investigated, but association was not moderated by either | |

| 1. Least green space (Q1) | 1. 1 | 1. NA | ||

| 2. Most green space (Q4) | 2. 0.81 | 2. 0.65–0.99 | ||

| 3. Mediation by PA | 3. 0.96 | 3. 0.88–1.06 | ||

| Dzhambov et al., 2016 [83] | Day-evening-night equivalent sound level: | OR: | Age, sex, fine particulate matter, benzo alpha pyrene, BMI, family history of T2DM, subjective sleep disturbance, bedroom location | |

| 1. 51–70 decibels | 1. 1 | 1. NA | ||

| 2. 71–80 decibels | 2. 4.49 | 2. 1.39–14.7 | ||

| Eichinger et al., 2015 [50] | Characteristics of built residential environment: | Beta: | Age, sex, individual-level SES | |

| 1. Perceived distance to local facilities | 1. 0.006 | 1. P < 0.01 | ||

| 2. Perceived availability/maintenance of cycling/walking infrastructure | 2. NS | |||

| 3. Perceived connectivity | 3. NS | |||

| 4. Perceived safety with regards to traffic | 4. NS | |||

| 5. perceived safety from crime | 5. NS | |||

| 6. Neighbourhood as pleasant environment for walking/cycling | 6. NS | |||

| 7. Presence of trees along the streets | 7. NS | |||

| Eriksson et al., 2014 [85] | Aircraft noise level: | OR: | Age, sex, family history, SES based on education, PA, smoking, alcohol, annoyance due to noise | |

| 1. <50 dB | 1. 1 | 1. NA | ||

| 2. ≥55 dB | 2. 0.94 | 2. 0.33–2.70 | ||

| Flynt et al., 2015 [73] | Clusters (combination of number of counties, urban-rural classification, population density, income, SES, access to food stores, obesity rate, diabetes rate): | Median standardised diabetes mellitues rate: | IQR: | - |

| 1 | 1. 0 | 1. -0.05 - 0.7 | ||

| 2 | 2. 0 | 2. -0.04–0.7 | ||

| 3 | 3. 0 | 3. -0.08–0.01 | ||

| 4 | 4. -0.04 | 4. -1.01–0.6 | ||

| 5 | 5. -0.08 | 5. -1.5–-0.04 ANOVA: p < 0.001 |

||

| Frankenfeld et al., 2015 [74] | RFEI ≤ 1 clusters: | Predicted prevalence: | Demographic and SES variables | |

| 1. Grocery stores | 1. 7.1 | 1. 6.3–7.9 | ||

| 2. Restaurants | 2. 5.9 | 2. 5.0–6.8, p < 0.01 | ||

| 3. Specialty foods | 3. 6.1 | 3. 5.0–7.2, p < 0.01 | ||

| RFEI >1: | ||||

| 4. Restaurants and fast-food | 4. 6.0 | 4. 4.9–7.1, p < 0.01 | ||

| 5. Convenience stores | 5. 6.1 | 5. 4.9–7.3, p < 0.01 | ||

| Freedman et al., 2011 [68] | Built environment: | OR: | Age, ethnicity, marital status, region of residence, smoking, education, income, childhood health, childhood SES, region of birth, neighbourhood scales | |

| Men: | ||||

| 1. Connectivity (2000 Topologically Integrated | 1. 1.06 | 1. 0.86–1.29 | ||

| Geographic Encoding and Referencing system) | 2. 1.05 | 2. 0.89–1.24 | ||

| 2. Density (number of food stores, restaurants, housing units per square mile) | ||||

| Women: | ||||

| 3. Connectivity | 3. 1.01 | 3. 0.84–1.20 | ||

| 4. Density | 4. 0.99 | 4. 0.99–1.17 | ||

| Fujiware et al., 2017 [60] | Count within neighbourhood unit (mean 6.31 ± 3.9 km2) | OR per IQR increase: | Age, sex, marital status, household number, income, working status, drinking, smoking, vegetable consumption, walking, going-out behaviour, frequency of meeting, BMI, depression | |

| 1. Grocery stores | 1. 0.97 | 1. 0.88–1.08 | ||

| 2. Parks | 2. 1.16 | 2. 1–1.34 | ||

| Gebreab et al., 2017 [61] | Density within 1-mile buffer: | HR: | Age, sex, family history of diabetes, SES, smoking, alcohol consumption, physical activity, diet | |

| 1. Favourable food stores | 1. 1.03 | 1. 0.98–1.09 | ||

| 2. Unfavourable food stores | 2. 1.07 | 2. 0.99–1.16 | ||

| 3. PA resources | 3. 1.03 | 3. 0.98–1.09 | ||

| Glazier et al., 2014 [21] | Walkability index: | Rate ratio: | Age, sex | |

| 1. Q1 | 1. 1 | 1. NA | ||

| 2. Q5 | 2. 1.33 | 2. 1.33–1.33 | ||

| Index components: | ||||

| 1. Population density (Q1: Q5) | 1. 1.16 | 1. 1.16–1.16 | ||

| 2. Residential density (Q1: Q5) | 2. 1.33 | 2. 1.33–1.33 | ||

| 3. Street connectivity (Q1: Q5) | 3. 1.38 | 3. 1.38–1.38 | ||

| 4. Availability of walkable destinations (Q1: Q5) | 4. 1.26 | 4. 1.26–1.26 | ||

| Heidemann et al., 2014 [86] | Residential traffic intensity: | OR: | Age, sex, smoking, passive smoking, heating of house, education, BMI, waist circumference, PA, family history | |

| 1. No traffic | 1. 1 | 1. NA | ||

| 2. Extreme traffic | 2. 1.97 | 2. 1.07–3.64 | ||

| Hipp et al., 2015 [78] | Food deserts | Correlation: NR | NS | – |

| Lee et al., 2015 [45] | Walkability: | OR: | Age, sex, smoking, alcohol, income level | |

| 1. Community 1 | 1. 1 | 1. NA | ||

| 2. Community 2 | 2. 0.86 | 2. 0.75–0.99 | ||

| Loo et al., 2017 [62] | Walkability (walk score) Difference between Q1 and Q4 |

Beta for HbA1C: | Age, sex, current smoking status, BMI, relevant medications and medical diagnoses, neighbourhood violent crime rates and neighbourhood indices of material deprivation, ethnic concentration, dependency, residential instability | |

| 1. -0.06 | 1. -0.11–0.02 | |||

| Beta for fasting glucose: | ||||

| 2. 0.03 | 2. -0.04–0.1 | |||

| Maas et al., 2009 [66] | Green space: | OR: | Demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, urbanicity | |

| 1. Q1 | 1. 1 | 1. NA | ||

| 2. Q4 | 2. 0.84 | 2. 0.83–0.85 | ||

| Mena et al., 2015 [53] | Correlation: | – | ||

| 1. Distance to parks | 1. NR | 1. NA | ||

| 2. Distance to markets | 2. -0.094 | 2. P < 0.05 | ||

| Mezuk et al., 2016 [70] | Ratio of the number of health-harming food outlets to the total number of food outlets within a 1000-m buffer of each person | OR per km2: 2.11 | 1.57–2.82 | Age, sex, education, household income |

| Morland et al., 2006 [75] | Presence of: | Prevalence ratio: | Age, sex, income, education, ethnicity, food stores and service places, PA | |

| 1. Supermarkets | 1. 0.96 | 1. 0.84–1.1 | ||

| 2. Grocery stores | 2. 1.11 | 2. 0.99–1.24 | ||

| 3. Convenience stores | 3. 0.98 | 3. 0.86–1.12 | ||

| Müller-Riemenschneider et al., 2013 [65] | Walkability (1600 m buffer): | OR: | Age, sex, education, household income, marital status | |

| 1. High walkability | 1. 0.95 | 1. 0.72–1.25 | ||

| 2. Low walkability | 2. 1 | 2. NA | ||

| Walkability (800 m buffer): | ||||

| 3. High walkability | 3. 0.69 | 3. 0.62–0.90 | ||

| 4. Low walkability | 4. 1 | 4. NA | ||

| Myers et al., 2017 [63] | Physical activity: | Beta: | Age | |

| 1. Recreation facilities per 1000 | 1. -0.457 | 1. -0.809– -0.104 | ||

| 2. Natural amenities (1–7) | 2. 0.084 | 2. 0.042–0.127 | ||

| Food: | ||||

| 3. Grocery stores and supercentres per 1000 | 3. 0.059 | 3. -0.09–0.208 | ||

| 4. Fast-food restaurants per 1000 | 4. -0.032 | 4. -0.125–0.062 | ||

| Ngom et al., 2016 [64] | Distance to green space: | Prevalence ratio: | Age, sex, social and environmental predictors | |

| 1. Q1 (0–264 m) | 1. 1 | 1. NA | ||

| 2. Q4 (774–27781 m) | 2. 1.09 | 2. 1.03–1.13 | ||

| Paquet et al., 2014 [54] | Built environment attributes: | RR: | Age, sex household income, education, duration of FU, area-level SES | |

| 1. RFEI | 1. 0.99 | 1. 0.9–1.09 | ||

| 2. Walkability | 2. 0.88 | 2. 0.8–0.97 | ||

| 3. POS | ||||

| a. POS count | a. 1 | a. 0.92–1.08 | ||

| b. POS size | b. 0.75 | b. 0.69–0.83 | ||

| c. POS greenness | c. 1.01 | c. 0.9–1.13 | ||

| d. POS type | d. 1.09 | d. 0.97–1.22 | ||

| Schootman et al., 2007 [56] | Neighbourhood conditions (objective): | OR: | Age, sex, income, perceived income adequacy, education, marital status, employment, length of time at present address, own the home, area | |

| 1. Housing conditions | 1. 1.11 | 1. 0.63–1.95 | ||

| 2. Noise level from traffic, industry, etc. | 2. 0.9 | 2. 0.48–1.67 | ||

| 3. Air quality | 3. 1.2 | 3. 0.66–2.18 | ||

| 4. Street and road quality | 4. 1.03 | 4. 0.56–1.91 | ||

| 5. Yard and sidewalk quality | 5. 1.05 | 5. 0.59–1.88 | ||

| Neighbourhood conditions (subjective): | ||||

| 6. Fair–poor rating of the neighbourhood | 6. 1.04 | 6. 0.58–1.84 | ||

| 7. Mixed or terrible feeling about the neighbourhood | 7. 1.1 | 7. 0.6–2.02 | ||

| 8. Undecided or not at all attached to the neighbourhood | 8. 0.68 | 8. 0.4–1.18 | ||

| 9. Slightly unsafe–not at all safe in the neighbourhood | 9. 0.61 | 9. 0.35–1.06 | ||

| Sørensen et al., 2013 [84] | Exposure to road traffic noise per 10 dB: | Incidence rate ratio: | Age, sex, education, municipality SES, smoking status, smoking intensity, smoking duration, environmental tobacco smoke, fruit intake, vegetable intake, saturated fat intake, alcohol, BMI, waist circumference, sports, walking, pollution | |

| 1. At diagnosis | 1. 1.08 | 1. 1.02–1.14 | ||

| 2. 5 years preceding diagnosis | 2. 1.11 | 2. 1.05–1.18 | ||

| Sundquist et al., 2015 [22] | Walkability: | OR: | Age, sex, income, education, neighbourhood deprivation | |

| 1. D1 (low) | 1. 1.16 | 1. 1.00–1.34 | ||

| 2. D10 (high) | 2. 1 | 2. NA |

BMI body mass index, CI Confidence interval, GIS graphical information system, HR hazard ratio, IQR interquartile range, NA not applicable, NR not reported, NS not significant, OR odds ratio, PA physical activity, MVPA moderate to vigorous physical activity, POS Public open space, RFEI Retail Food Environment Index, RR relative risk, SD standard deviation, SE standard error, SES socioeconomic status, FU follow-up

Four studies investigated the association between residential noise and T2DM risk/prevalence. One study received a strong quality rating [82]. All studies observed that higher exposure to residential noise was associated with increased T2DM risk/prevalence [82–85]. In meta-analyses of four studies [83–86], higher exposure to residential noise was not associated with T2DM risk/prevalence (1.49; 95% CI, 0.78–2.82, I2 = 75.8%).

Discussion

This systematic review investigated evidence for the association between built environmental characteristics, related to lifestyle behaviours, and T2DM risk/prevalence, worldwide. The association between built environmental characteristics and T2DM risk/prevalence has been investigated a fair amount, with 84 studies on the subject, although for our review, 23 of these studies were excluded due to their low quality ratings. Urbanisation was associated with a higher T2DM risk/prevalence. The evidence for an association between the physical activity environment and T2DM risk was more consistent than it was for the food environment. Higher neighbourhood walkability was associated with lower T2DM risk and more green space tended to be associated with lower T2DM risk.

First, we observed that residing in urban areas was associated with higher T2DM risk/prevalence, in line with the findings of the IDF diabetes atlas [8] and a recent meta-analysis for South East Asia. Urbanisation is a process in which inhabitants of a particular region increasingly move to more densely populated areas. Urbanisation is a broad operationalisation of the built environment and includes a range of characteristics, such as higher availability of food, facilities, and infrastructure. In general, previous reviews have observed conflicting results for urbanisation [4, 5, 8]. Urbanisation has consistently been associated with less physical activity and unhealthier dietary habits, but also with higher total walking and cycling for transportation [4, 5, 8]. The observed heterogeneity in terms of results might be due to the variety of definitions used to classify an urban area, which is distinct for different countries and studies. To account for this, we stratified our analyses by country income level [18], and the majority of studies (38 out of 60) were conducted in middle-income countries, which reduces the heterogeneity in the studies included. It must be recognised that considerable heterogeneity in definitions of urban vs. rural exists beyond stratification on country income level. Across countries with the same country income level, there is large variety of what urban or rural areas may look like and the populations that reside in these areas. At present, there is no homogeneous and generally accepted definition of urban or rural areas and the majority of studies did not include a definition that was used to make this classification.

Second, the present study provides consistent evidence for an association between the built physical activity environment and T2DM risk/prevalence. Higher walkability and availability of green space were most consistently associated with lower T2DM risk/prevalence. Our results for urbanisation seem contradictory to the lower T2DM risk/prevalence associated with greater neighbourhood walkability, since greater walkability is often observed in more urbanised environments [5]. These seemingly contradictory results could be explained by the underrepresentation of high-income countries in the urban to rural comparison studies, and the overrepresentation of these countries in walkability studies. The (perceived) walkability of urban areas also varies across different parts of the world. So, whereas walkability may be a feature of cities in high-income regions, this may not be the case in cities in lower-income regions. Furthermore, urbanisation is a much broader construct than walkability, and even within one urban area, walkability may differ between or even within neighbourhoods. In addition, other urbanisation-related issues, besides walkability, may be more important, such as other physical activity environment characteristics and the food environment, which counterbalance the effects of walkability in urban areas. These results would suggest that certain aspects of the built food environment were associated with a higher T2DM risk, but we could not find consistent evidence of this in our review.

An association between the built food environment and T2DM risk/prevalence was not consistently observed. The availability of fast-food and convenience stores and the perceived healthiness of the food environment tended to be associated with higher T2DM risk/prevalence and lower T2DM risk/prevalence, respectively. However, due to heterogeneity in the studies, insufficient studies were available for meta-analysis, thus preventing us from drawing solid conclusions. The only possible meta-analyses were three studies including the density of grocery stores, but this confirmed that no significant associations could be observed. Also by reviewing the evidence, supermarkets and grocery stores and the RFEI were not associated with T2DM risk/prevalence. These findings are consistent with an earlier systematic review that reported that perceived availability was associated with healthy dietary behaviours [9], whereas objective measures of accessibility and availability of food environment yielded mixed results [9]. The association between the perceived environment and a healthier diet can be explained by not limiting the concept of environment to specific shops or locations, but rather to the participant’s resources for healthy food, e.g. gardens and markets. On the other hand, perceptions may also reflect an individual’s intentions and motivations rather than location alone. A difficulty with regard to establishing useful diet measures is that they are very heterogeneous and difficult to define. For instance, access to a supermarket is often seen as contributing to a healthy food environment, even though they are also sources of unhealthy products [9]. Establishing a comprehensive definition is further complicated because food can be bought in a variety of shops and locations that are not directly associated with food, e.g. at the counter of a pharmacy. The same heterogeneity was observed to a lesser extent in the built physical activity environment. For instance, infrastructure includes drivers for active transportation (sidewalks and cycling lanes) as well as for passive transportation (public transport and roads) [87]. We conclude that the heterogeneity in exposure assessment associated with built environmental variables made the examination of the associations with T2DM risk/prevalence more difficult.

Finally, although higher exposure to residential noise was consistently associated with higher T2DM risk/prevalence in individual studies, this was not confirmed in our meta-analysis, in contrast with an earlier meta-analysis [16]. This difference could be explained by the inclusion of only confounder adjusted risk ratios in our study.

A strength of this study is the comprehensive overview of the literature on the association between built environmental characteristics and T2DM risk/prevalence, in which we included worldwide evidence. We assessed study quality and took country income levels into account. However, certain limitations of this study need to be addressed.

A weakness of any systematic review and meta-analysis is that its quality is dependent on the quality of the studies included. For instance, not all studies that were included distinguished between T2DM and type 1 diabetes mellitus. However, the majority of all people with diabetes have T2DM so the evidence provided in our review was very likely applicable to T2DM risk/prevalence [1]. Secondly, because most studies in the present review were cross-sectional, our review cannot provide the foundation for causal inferences. Finally, publication bias could influence our findings, but our search turned out a relatively high number of null findings, suggesting publication bias an unlikely limitation. Finally, residential self-selection is an important issue that should be included in studies investigating the associations between built environment and disease. Self-selection occurs when residents choose a residence based on socioeconomic or other circumstances, or lifestyle preferences. Evidently, such selections may influence our results, as for instance higher socioeconomic status neighbourhoods may contain more green space, as well as more highly educated and health-conscious residents. However, the true effect of residential self-selection on these associations has often not been accounted for in the included studies and is difficult to investigate. One narrative review observed that studies using various approaches to identify self-selection (i.e. a questionnaire or statistical methods) explained only a minor part of the associations between built environment and travel behaviours [88]. Two studies included in the present review observed that residential relocation, as an indicator of self-selection, resulted in inconsistent effects on associations with health outcomes [57, 58]. It is, therefore, hard to conclude on the effect of self-selection bias on our results, based on the current evidence.

Despite the limitations of our study, our results may be relevant for infrastructure planning. For example, in addition to other positive consequences of walkability and access to green space, these environmental characteristics may also contribute to T2DM prevention. Future research should focus on developing a more homogeneous definition of environmental characteristics, particularly in relation to the food environment. Also, more in-depth explorations are necessary of the pathways through which environments affect diabetes risk, while taking the potential confounding variables into account.

Conclusions

In conclusion, urbanisation is associated with higher T2DM risk/prevalence. The built physical activity environment - walkability and access to green space, in particular - was consistently associated with reduced T2DM risk/prevalence, while no consistent evidence was found for an association between the built food environment and T2DM risk/prevalence. These conclusions have implications in terms of urban planning and the inclusion of walkable and green cities.

Additional files

Search strategy (DOCX 21 kb)

Study characteristics and results of studies with a weak quality rating (DOCX 43 kb)

Sensitivity analyses (ZIP 120 kb)

Study characteristics and results of studies investigating combination environmental characteristics. (DOCX 21 kb)

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors declare that this research received no funding. As a corresponding author, I confirm that I had full access to all data and the final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Availability of data and material

The data sets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors’ contributions

NdB performed the literature search, study selection, data extraction, quality assessment and data synthesis, and drafted the manuscript, tables and figures. JL performed study selection and quality assessment, assessed data extraction and made major revisions to the manuscript. FR provided support in design and execution of the review and meta-analyses, and made major revisions to the manuscript. LJ performed the literature search and contributed to drafting the methods section and flow chart of inclusion. JB provided support in design and execution of the review and meta-analyses, and made major revisions to the manuscript. JWJB performed study selection and quality assessment, made major revisions to the manuscript, is the guarantor of this work and takes responsibility for the integrity of the work and analyses. This manuscript has not been submitted elsewhere and it is original.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

The online version of this article (doi:10.1186/s12916-017-0997-z) contains supplementary material, which is available to authorized users.

References

- 1.WHO. Diabetes, Fact Sheet. WHO; 2016. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs312/en/. Accessed Sept 2016.

- 2.Cappuccio FP, D'Elia L, Strazzullo P, Miller MA. Quantity and quality of sleep and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Diabetes Care. 2010;33(2):414–20. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Teixeira PJ, Carraca EV, Marques MM, Rutter H, Oppert JM, De Bourdeaudhuij I, et al. Successful behavior change in obesity interventions in adults: a systematic review of self-regulation mediators. BMC Med. 2015;13:84. doi: 10.1186/s12916-015-0323-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Van Holle V, Deforche B, Van Cauwenberg J, Goubert L, Maes L, Van de Weghe N, et al. Relationship between the physical environment and different domains of physical activity in European adults: a systematic review. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:807. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sallis JF, Cerin E, Conway TL, Adams MA, Frank LD, Pratt M, et al. Physical activity in relation to urban environments in 14 cities worldwide: a cross-sectional study. Lancet. 2016;387(10034):2207–17. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01284-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osei-Kwasi HA, Nicolaou M, Powell K, Terragni L, Maes L, Stronks K, et al. Systematic mapping review of the factors influencing dietary behaviour in ethnic minority groups living in Europe: a DEDIPAC study. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2016;13:85. doi: 10.1186/s12966-016-0412-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Popkin BM. Nutrition transition and the global diabetes epidemic. Curr Diab Rep. 2015;15(9):64. doi: 10.1007/s11892-015-0631-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cho N, Whiting D, et al. Diabetes Atlas, 7th ed. International Diabetes Federation; 2015. http://www.oedg.at/pdf/1606_IDF_Atlas_2015_UK.pdf.

- 9.Caspi CE, Sorensen G, Subramanian S, Kawachi I. The local food environment and diet: a systematic review. Health Place. 2012;18(5):1172–87. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fraser LK, Edwards KL, Cade J, Clarke GP. The geography of fast food outlets: a review. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2010;7(5):2290–308. doi: 10.3390/ijerph7052290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ising H, Braun C. Acute and chronic endocrine effects of noise: review of the research conducted at the Institute for Water. Soil Air Hygiene Noise Health. 2000;2(7):7–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pirrera S, De Valck E, Cluydts R. Nocturnal road traffic noise: a review on its assessment and consequences on sleep and health. Environ Int. 2010;36(5):492–8. doi: 10.1016/j.envint.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Angkurawaranon C, Jiraporncharoen W, Chenthanakij B, Doyle P, Nitsch D. Urbanization and non-communicable disease in Southeast Asia: a review of current evidence. Public health. 2014;128(10):886–95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Schulz M, Romppel M, Grande G. Built environment and health: a systematic review of studies in Germany. J Public Health. 2016. https://doi.org/10.1093/pubmed/fdw141. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Malambo P, Kengne AP, De Villiers A, Lambert EV, Puoane T. Built environment, selected risk factors and major cardiovascular disease outcomes: a systematic review. PLoS One. 2016;11(11):e0166846. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dzhambov AM. Long-term noise exposure and the risk for type 2 diabetes: a meta-analysis: erratum. Noise Health. 2015;17(75):123. doi: 10.4103/1463-1741.153404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mackenbach JD, Rutter H, Compernolle S, Glonti K, Oppert JM, Charreire H, et al. Obesogenic environments: a systematic review of the association between the physical environment and adult weight status, the SPOTLIGHT project. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:233. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Bank list of economies, 2016. http://www.ispo2017.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/11/World-Bank-List-of-Economies.pdf. Accessed Sept 2016.

- 19.Booth GL, Creatore MI, Moineddin R, Gozdyra P, Weyman JT, Matheson FI, et al. Unwalkable neighborhoods, poverty, and the risk of diabetes among recent immigrants to Canada compared with long-term residents. Diabetes Care. 2013;36:302–5. doi: 10.2337/dc12-0777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Creatore MI, Glazier RH, Moineddin R, Fazli GS, Johns A, Gozdyra P, et al. Association of neighborhood walkability with change in overweight, obesity, and diabetes. JAMA. 2016;315(20):2211–20. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.5898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Glazier RH, Creatore MI, Weyman JT, Fazli G, Matheson FI, Gozdyra P, et al. Density, destinations or both? A comparison of measures of walkability in relation to transportation behaviors, obesity and diabetes in Toronto, Canad. PLoS One. 2014;9(1):e85295. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0085295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sundquist K, Eriksson U, Mezuk B, Ohlsson H. Neighborhood walkability, deprivation and incidence of type 2 diabetes: a population-based study on 512,061 Swedish adults. Health Place. 2015;31:24–30. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2014.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cubbin C, Sundquist K, Ahlen H, Johansson SE, Winkleby MA, Sundquist J. Neighborhood deprivation and cardiovascular disease risk factors: protective and harmful effects. Scand J Public Health. 2006;34(3):228–37. doi: 10.1080/14034940500327935. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Danesh J, Collins R, Appleby P, Peto R. Association of fibrinogen, C-reactive protein, albumin, or leukocyte count with coronary heart disease: meta-analyses of prospective studies. JAMA. 1998;279(18):1477–82. doi: 10.1001/jama.279.18.1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Dar HI, Dar SH, Bhat RA, Kamili MA, Mir SR. Prevalence of type 2 diabetes mellitus and its risk factors in the age group 40 years and above in the Kashmir valley of the Indian subcontinent. JIACM. 2015;16(3–4):187–97. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mi T, Sun S, Du Y, Guo S, Cong L, Cao M, et al. Differences in the distribution of risk factors for stroke among the high-risk population in urban and rural areas of Eastern China. Brain Behav. 2016;6(5):e00461. doi: 10.1002/brb3.461. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kodaman N, Aldrich MC, Sobota R, Asselbergs FW, Poku KA, Brown NJ, et al. Cardiovascular disease risk factors in Ghana during the rural-to-urban transition: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One. 2016;11(10):e0162753. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gangquiang D, Ming Y, Weiwei G, Ruying H, MacLennan R. Nutrition-related disease and death in Zhejiang Province. Asia Pacific J Clin Nutr. 2004;13(2):162–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Azizi F, Vazirian P, Dolatshi P, Habibian S. Screening for type 2 diabetes in the Iranian national programme: a preliminary report. East Mediterr Health J. 2003;9(5–6):1122–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mierzecki A, Kloda K, Gryko A, Czarnowski D, Chelstowski K, Chlabicz S. Atherosclerosis risk factors in rural and urban adult populations living in Poland. Exp Clin Cardiol. 2014;20(8):3152–7. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Njelekela M, Sato T, Nara Y, Miki T, Kuga S, Noguchi T, et al. Nutritional variation and cardiovascular risk factors in Tanzania – rural–urban difference. S Afr Med J. 2003;93(4):295–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ceesay MM, Morgan MW, Kamanda MO, Willoughby VR, Lisk DR. Prevalence of diabetes in rural and urban populations in southern Sierra Leone: a preliminary survey. Trop Med Int Health. 1997;2(3):272–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.1997.d01-265.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Asadollahi K, Delpisheh A, Asadollahi P, Abangah G. Hyperglycaemia and its related risk factors in Ilam province, west of Iran – a population-based study. J Diabetes Metab Disord. 2015;14:81. doi: 10.1186/s40200-015-0203-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bharati D, Pal R, Rekha R, Yamuna T, Kar S, Radjou A. Ageing in Puducherry, South India: an overview of morbidity profile. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2011;3(4):537–42. doi: 10.4103/0975-7406.90111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Colleran KM, Richards A, Shafer K. Disparities in cardiovascular disease risk and treatment: demographic comparison. J Investig Med. 2007;55(8):415–22. doi: 10.2310/6650.2007.00028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Khan MM, Gruebner O, Kraemer A. The geography of diabetes among the general adults aged 35 years and older in Bangladesh: recent evidence from a cross-sectional survey. PLoS One. 2014;9(10):e110756. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0110756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nakibuuka J, Sajatovic M, Nankabirwa J, Furlan AJ, Kayima J, Ddumba E, et al. Stroke-risk factors differ between rural and urban communities: population survey in Central Uganda. Neuroepidemiology. 2015;44(3):156–65. doi: 10.1159/000381453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shera AS, Jawad F, Maqsood A. Prevalence of diabetes in Pakistan. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2007;76(2):219–22. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2006.08.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Valverde JC, Tormo MJ, Navarro C, Rodriguez-Barranco M, Marco R, Egea JM, et al. Prevalence of diabetes in Murcia (Spain): a Mediterranean area characterised by obesity. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2006;71(2):202–9. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2005.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mohamud WN, Ismail AA, Sharifuddin A, Ismail IS, Musa KI, Kadir KA, et al. Prevalence of metabolic syndrome and its risk factors in adult Malaysians: results of a nationwide survey. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2011;91(2):239–45. doi: 10.1016/j.diabres.2010.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bahendeka S, Wesonga R, Mutungi G, Muwonge J, Neema S, Guwatudde D. Prevalence and correlates of diabetes mellitus in Uganda: a population-based national survey. Trop Med Int Health. 2016;21(3):405–16. doi: 10.1111/tmi.12663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Astell-Burt T, Feng X, Kolt GS. Is neighborhood green space associated with a lower risk of type 2 diabetes? Evidence from 267,072 Australians. Diabetes Care. 2014;37(1):197–201. doi: 10.2337/dc13-1325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shaffer K, Bopp M, Papalia Z, Sims D, Bopp CM. The relationship of living environment with behavioral and fitness outcomes by sex: an exploratory study in college-aged students. Int J Exerc Sci. 2017;10(3):330–9. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bodicoat DH, O'Donovan G, Dalton AM, Gray LJ, Yates T, Edwardson C, et al. The association between neighbourhood greenspace and type 2 diabetes in a large cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. 2014;4(12):e006076. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee H, Kang HM, Ko YJ, Kim HS, Kim YJ, Bae WK, et al. Influence of urban neighbourhood environment on physical activity and obesity-related diseases. Public Health. 2015;129(9):1204–10. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ahern M, Brown C, Dukas S. A national study of the association between food environments and county-level health outcomes. J Rural Health. 2011;27(4):367–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2011.00378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Auchincloss AH, Diez Roux AV, Mujahid MS, Mingwu Shen MS, Bertoni AG, Carnethon MR. Neighborhood resources for physical activity and healthy foods and incidence of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169(18):1698–704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 48.Christine PJ, Auchincloss AH, Bertoni AG, Carnethon MR, Sanchez BN, Moore K, et al. Longitudinal associations between neighborhood physical and social environments and incident type 2 diabetes mellitus: the multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (MESA) JAMA Intern Med. 2015;175(8):1311–20. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2015.2691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cunningham-Myrie CA, Theall KP, Younger NO, Mabile EA, Tulloch-Reid MK, Francis DK, et al. Associations between neighborhood effects and physical activity, obesity, and diabetes: The Jamaica Health and Lifestyle Survey 2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2015;68(9):970–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2014.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]