Abstract

The ethnoracial makeup of the U.S. population has undergone transformative change during recent decades, with the non-Hispanic white share of the population shrinking while the minority shares expand. Yet this trend toward greater racial diversity is not universal throughout the nation. Here we propose a framework of segmented change, which incorporates both spatial assimilation and ethnic stratification theories, to better understand variation in patterns of diversification across American communities. Our research applies growth mixture models to decennial census data on places for the 1980–2010 period, finding that trajectories of ethnoracial diversity are much more uneven than popularly claimed. Moreover, types of diversity change are stratified by initial racial composition. While places with mostly-white populations in 1980 underwent extensive diversification, places with larger shares of Hispanics and (especially) blacks in 1980 exhibited less uniform movement toward diversity and were more likely to remain racially homogeneous. Analysis of the underlying group-specific pathways of change indicates that the diversification of white communities was driven largely by Hispanic growth; when areas with a black presence did diversify, it occurred via contracting white populations. These racially conditioned and locally variable patterns emphasize the segmented nature of diversity change in American society.

Few demographic trends in the contemporary United States are as important or newsworthy as the increasing racial and ethnic diversity of the national population. Driven by immigration, differential natural increase, youthful age structures, and other forces, all panethnic minority groups have grown more rapidly than the non-Hispanic white majority (Humes et al. 2011; also Johnson 2015).1 The implications of this trend are substantial, spanning major institutions and promising to reshape the social, economic, and political fabric of society. Empirical evidence on the consequences of ethnoracial diversification is still being assessed (Lichter 2013; Lindsay & Singer 2003), but the general direction of change is clear. The white slice of the U.S. population pie will continue to shrink for the foreseeable future while the slices of every non-white category—blacks and Native Americans as well as Hispanics and Asians—are likely to expand. Continued diversification, or movement toward more equal-sized slices, thus appears inevitable.

Yet emphasizing the national picture can be misleading. Our research is motivated by the uneven distribution of racial-ethnic diversity across the American landscape. For example, both the magnitude of diversity and its pace of change have been shown to differ from one region of the country to the next (Frey 2015). Similarly varied patterns are seen at the state level, with some states, such as California and Texas, containing minority populations that already outnumber whites, while others remain largely homogeneous, with whites making up four-fifths or more of the population (Wright et al. 2014). Here we elect to study local communities, where diversity contrasts are even sharper. In such communities diversity may be a fact of daily life, anchored in regular contact with people from ethnoracial groups outside one’s own, or it may be experienced more vicariously if one’s own group dominates. The main point is that diversity trends and consequences are not geographically uniform.

Our approach to understanding diversity patterns at the local community scale involves the development of what we refer to as a segmented change framework. This broad framework holds that communities do not follow a single, universal trajectory. Instead, race-specific spatial sorting processes (Lee et al. 2015) culminate in varied kinds of change, as predicted by the two theoretical perspectives subsumed within our framework. According to spatial assimilation theory, social and economic gains for certain ethnoracial groups should translate into access to a wider range of community destinations and greater spatial integration with whites. However, in line with the ethnic stratification perspective, the migration and settlement patterns of African Americans and some Latinos reflect durable legacies of discrimination and stigma, which permit little integration despite upward socioeconomic mobility. The community-level consequences of spatial sorting are further shaped by starting points, namely the extent of diversity in a community and its racial-ethnic structure (which groups are present in what proportions) at the beginning of the observation period. Our general expectation, based on the segmented change framework, is that spatial sorting will yield distinctive types of diversity change across communities over time, contingent upon their initial racial-ethnic contexts.

To evaluate this expectation, we analyze 1980 through 2010 decennial census data for four kinds of local communities (what the Census Bureau terms “places”): those that were all-white, mostly-white, white and black, or white and Hispanic in 1980. The analysis is cast within the segmented change framework, drawing insights from spatial assimilation and ethnic stratification theories. Our primary objective is to move beyond the overall or average trend in diversity, focusing instead on how diversity changes compare across and within the four types of places. Growth mixture models allow us to identify variation in patterns of diversity change exhibited by subsets of places, what we call trajectories of diversity. We complement these models by documenting the ethnoracial components of change that places with shared trajectories follow. Throughout the paper, attention is devoted to the manner in which race-based sorting governs the possibilities for change.

Background

Past Research

Much of the existing research on diversity addresses its consequences. This is not surprising given the ongoing national debate over the impact of immigration, one of the key engines of diversity change (along with differential natural increase [Johnson and Lichter 2010]). By definition, one outcome associated with rising diversity is the declining numerical dominance of non-Hispanic whites. Constituting four-fifths of the U.S. population as recently as 1980, whites are now projected to lose their majority status within the next three decades. At the same time, the Hispanic share of the population is expected to reach 29% by 2060, and the combined representation of Asian and multiracial individuals (9% and 5% respectively) will rival or surpass that of blacks (Colby & Ortman 2015). Many potential non-demographic consequences of racial-ethnic diversity have been explored as well. Illustrative studies examine how diversity influences the labor market, electoral politics, crime, and housing segregation (Bean & Stevens 2003; Borjas 1999; DeFina & Hannon 2009; Frey 2015; Parisi et al. 2015). Other lines of work consider the impact of diversity on social capital, trust, personal networks, cultural fragmentation, and intergroup relations (Abascal & Baldassarri 2015; Fischer & Hout 2006; Hou & Wu 2009; Laurence 2014; Lee & Bean 2010; Putnam 2007; Stolle et al. 2008).

Curiously, the studies just cited tend to cluster at the extremes of spatial scale, measuring diversity either for macro units such as states and metropolitan areas or for residential neighborhoods. A similar though less pronounced clustering is apparent in research that describes diversity patterns. Several neighborhood-oriented investigations report a drop in the number of all-white census tracts coupled with a marked increase in tracts shared by multiple ethnoracial groups (Farrell & Lee 2011; Flores & Lobo 2013; Holloway et al. 2012; Logan & Zhang 2010). But whites’ sensitivity to minority neighbors may render multiethnic tracts fragile, in part because whites leave such settings over time and are disinclined to move into them in the first place (Charles 2006; Crowder et al. 2011; Krysan et al. 2009). In parallel fashion, large metropolises have trended toward greater diversity due to minority and immigrant population growth and, in some instances, white population loss (Frey 2011b; Lee et al. 2014). The suburban rings of many metropolitan areas are also experiencing a rise in black, Latino, and Asian representation, albeit to a lesser degree than the metro core (Farrell 2016; Frey 2011a; Singer et al. 2008).

The Case for Place

Although both neighborhoods and metro areas can be conceptualized as communities, they are less than ideal in certain respects. Due to race- and class-based preferences which reinforce residential segregation, neighborhood-level analyses might miss the kinds of cross-group contact occurring in local institutions and activities that extend beyond neighborhood boundaries: in schools, workplaces, grocery stores, churches, parks, civic gatherings, and local politics. Metropolitan-level research, on the other hand, could overstate the salience of diversity to inhabitants if they sort into communities with homogeneous racial compositions.

Between the metropolis and the neighborhood fall census-defined places: individual cities, suburbs, towns, boroughs, and villages that encompass neighborhoods and may be located within metro areas. We regard places as an especially relevant type of community for our purposes. Most of them correspond to governmental jurisdictions and service districts that have prescribed functions; the largest—principal cities of metropolitan areas—often approximate housing and labor markets. As legal entities, incorporated places are typically responsible for developing fiscal or policy responses to diversity-related issues that arise within their boundaries. They can also take steps to discourage or promote diversification. For example, some places have used annexation, zoning, or other measures to deter minority growth and preserve ethnoracial homogeneity (Lichter et al. 2007; Pendall 2000; Rothwell and Massey 2009). At the opposite extreme, immigrant-fueled diversification is occasionally pursued as a revitalization strategy by places experiencing demographic and economic decline (Carr et al. 2012). Consistent with sociological definitions of place (Gieryn 2000), census places constitute symbolic as well as political entities: residents recognize them by name and feel more or less attached to them. The population of a place influences the ethnoracial composition of local neighborhoods, schools, work settings, and voluntary organizations and, ultimately, the social relationships that form in these venues. On a number of dimensions, then, places qualify as “real” communities in addition to being convenient statistical aggregations.

Despite their value as meaningful communities, places have attracted only modest interest from diversity scholars. Cross-sectional evidence suggests that the magnitude of diversity is positively related to several place characteristics, including population size, metropolitan status, a military or government presence, manufacturing and agricultural employment, housing affordability, and location in a coastal or southern border state (Allen & Turner 1989; Lee et al. 2012; Price & Singer 2008). Most critical from our standpoint, however, are the broad strokes with which temporal changes in place diversity have been painted. Lee and associates (2012), for instance, portray ethnoracial diversity as a “master trend”, finding that the average magnitude of diversity rose between 1980 and 2010 for places in all regions of the country and across metropolitan, micropolitan, and rural settings. While average trends are useful for summarizing broad changes, these results say little about variation in the diversity trajectories exhibited by places, in particular how much their initial diversity levels differ and how rapidly and in what direction the levels change. Even for those places on a similar trajectory, the specific shifts they experience in racial-ethnic structure are unlikely to be the same. Such possibilities confirm the need for a detailed approach to describing diversity trends at the community scale.

Perspectives on Diversity Change

The first step in developing this approach is to recognize the variety of distinct forms that ethnoracial change can take. Along with the emergence of what Logan and Zhang (2010) refer to as “global” neighborhoods, some larger community units—not only places but metropolitan areas—have experienced a combination of Hispanic and Asian growth and white decline that produces increasingly diverse racial-ethnic structures consisting of multiple groups, none of which attains majority status (Wright et al. 2014; Frey 2015; Lee et al. 2014). Stable diversity constitutes another scenario. For example, a relatively flat diversity trajectory may result from the long-term concentration of two or more groups in a community that is viewed as a “comfort zone” because of its extensive ethnic infrastructure and reputation for incorporating immigrants (Lieberson & Waters 1988; Portes & Rumbaut 2006). Stable diversity could also be due to the presence of certain types of organizations (e.g., military bases, government agencies, agricultural processing facilities, prisons) with institutional practices that draw members from many panethnic backgrounds. Other trajectories include diversity decline—when one group becomes a more dominant share of the local population over time—and stable homogeneity, epitomized by the persistently white suburb but also reflected in enduring nonwhite places (e.g., Hispanic communities in South Texas, small “Black Belt” towns).

To capture the full range of trends, we propose that a segmented change framework be adopted. Based loosely on Portes and Zhou’s (1993) segmented assimilation model, the framework assumes that places, like minority groups, do not conform to a single trajectory. Rather, they may grow more or less diverse at different speeds or remain stable, and their initial racial-ethnic structure (and other starting-point characteristics) should condition how they evolve. In an abstract sense, the trajectories followed by places are the culmination of where immigrants and members of subsequent generations wind up as they pursue economic opportunities and encounter obstacles. While some places undergo gradual increases in diversity in response to immigrant ascendance into the middle class, others are likely to remain homogeneous or become more so as the selection of white and minority residents into separate communities promotes racial isolation. According to the segmented change framework, then, numerous trajectories should be anticipated; one path will not fit all places.

Why is this the case? For insights about the forces responsible, our overarching framework encompasses two popular theoretical perspectives on spatial sorting. The first perspective, spatial assimilation, holds that minority group incorporation into the societal mainstream occurs via socioeconomic mobility and (in the case of immigrants) acculturation. As blacks, Hispanics, and Asians progress along these dimensions, they should be better able to pursue desirable residential opportunities beyond the boundaries of ethnic enclaves or ghettos (Alba and Logan 1991; Rosenbaum and Friedman 2007). To date, scholars have applied the assimilation perspective primarily to group members’ dispersion and spatial integration (with whites) across neighborhoods (Iceland 2009; South et al. 2008). However, the logic works at the community level as well, predicting that people of color will become more widely and comparably distributed among places over time. Place diversity is anticipated to track upward as a result.

In contrast to spatial assimilation, ethnic stratification theory stresses the factors that separate groups and ultimately limit or erode the diversity of places. Discriminatory practices by real estate agents and lenders are one such factor, effectively restricting where minority homeseekers can live (Pager & Shepherd 2008; Turner et al. 2013). Certain types of land use regulations and policies register a similar impact. As an illustration, low-density zoning may put the cost of housing in white communities out of reach of many African American households (Rothwell & Massey 2009). Even when minorities overcome such barriers and achieve a degree of residential integration, there is no guarantee that the places they enter will remain racially mixed. Indeed, the aversion of some incumbent whites to other races seems sufficiently acute to prompt their flight, not only from neighborhoods but from larger contexts (Crowder et al. 2011; Frey 1995; Pais et al. 2009). At the same time, own-group affinity tends to encourage geographic clustering among all groups (Charles 2006, 2007), with immigrant-rich suburbs—also known as “ethnoburbs”—a recent manifestation (Li 2009; Wen et al. 2009). This version of the stratification perspective thus includes self-selective processes as well as external constraints.2 It expects both kinds of mechanisms to operate in a pro-segregation manner, sorting different groups into different places, with less diversity as a result.

The mechanisms highlighted in stratification theory can spur community racial succession. Although much of the succession literature has focused on neighborhoods (see, e.g., Lee & Wood 1991; Taeuber & Taeuber 1969), the central principle applies across geographic scales: a mixed or diverse racial composition is often temporary. Given differences in group-specific growth rates and the presence of racial preferences and discriminatory practices, succession may eventually occur, with one group outpacing all others and the community population trending toward greater homogeneity (Friedman 2008; Lobo et al. 2002; Wilson and Taub 2006). Lee and Hughes (2015) find modest evidence of succession among places. Since 1980, a small number appear to have passed their diversity peaks and now exhibit less complex racial-ethnic structures in which Latinos predominate. These places that have “bucked the trend” are disproportionately located in the South and West.

Despite appearances, we do not consider the spatial assimilation and ethnic stratification theories inherently incompatible. Although the former favors ethnoracial diversity and the latter favors homogeneity, the explanatory factors emphasized by the perspectives simultaneously shape the trajectories of places. The likelihood that these factors vary in strength from one place to the next and over time provides a justification for the segmented change framework. Which factors are most significant—and hence which trajectories are most common—also depend on where a place begins, in particular its initial diversity level and racial-ethnic structure. For example, communities that start with homogeneous white compositions might be anticipated to exhibit a different array of trajectories after that point than would more diverse places with multi-group structures.

Hypotheses

Because the driving forces identified by the spatial assimilation and ethnic stratification components of the segmented change framework are difficult to link directly to community ethnoracial patterns, our analysis focuses only on descriptive hypotheses. For the 1980–2010 period, we hypothesize that:

The vast majority of places will become more ethnoracially diverse, reflecting the trend in the national population.

Within broad types of 1980-defined places (i.e., those with all-white, mostly-white, white-black, or white-Hispanic racial structures in that year), multiple trajectories of diversification will be apparent.

Mostly-white places, in which modest minority representation at the beginning of the study period implies some openness to other groups, will experience steeper diversity gains than their all-white counterparts.

White-black places with large 1980 shares of African Americans will be the type of place least likely to diversify.

White-Hispanic places will fall between the mostly-white and white-black types and display the greatest variability in their trajectories.

Methodology

Places and Races

We use data from the 1980–2010 decennial censuses to describe patterns of and trends in diversity for U.S. communities over the last three decades. Our file includes all census places which had populations of 1,000 or more in 1980 and which remained as places by the end of the study period. Most of these places are incorporated as cities, suburbs, towns, or villages and vested with governing authority. Others (officially labeled census-designated places) are determined by the Census Bureau to resemble incorporated communities even though they lack municipal status.3 As noted earlier, both types of places constitute meaningful social, symbolic, and institutional contexts with recognizable identities. Unlike many neighborhood-level studies, we use contemporaneous geographic boundaries in order to capture the actual experience of ethnoracial diversity within a place in a given year. Jurisdictional status provides a partial rationale for this operational decision. If, for example, a municipality annexes or cedes land, any resulting shifts in diversity would matter throughout the redefined unit, not just inside its old or new territory.4

We allocate the residents of each place to one of five mutually exclusive panethnic categories: Hispanics and non-Hispanic whites, blacks, Asians/Pacific Islanders, and all other non-Hispanics. Places in turn are classified into four types based on their 1980 racial-ethnic composition. All-white communities were 90% or more white in 1980. Mostly-white communities were less than 90% white but no other group comprised as much as one-tenth of the population. White-black communities consist of majority-black places and those with substantial numbers of white and black residents (both groups exceeding 10% and no other group more than 10%). In similar fashion, white-Hispanic communities may be either majority-Hispanic or include non-trivial proportions of both whites and Hispanics (both groups exceeding 10% and no other group more than 10%). This classification scheme summarizes the 1980 racial-ethnic structure of American communities in a concise yet thorough manner, capturing all but 359 places, which did not form large enough groups based on their 1980 racial-ethnic composition to analyze on their own.5 In total, our analysis examines patterns of ethnoracial diversity for 11,081 places.

Diversity Measurement

We measure diversity using the entropy index, which assesses the extent to which the distribution of panethnic groups in a community deviates from a hypothetical uniform distribution in which all groups comprise equal shares (20% in our five-group case). The index is expressed as:

where r refers to panethnic groups in community i. Normalizing by the natural log of the number of groups (1.609 for five groups) scales E scores from 0 to 1, with values closer to 1 identifying highly diverse places (i.e., where ethnoracial composition approximates the uniform distribution) and values closer to 0 depicting more homogeneous places (i.e., where a single racial-ethnic group dominates).

The entropy index may appear to set an implausibly high bar, given the white-skewed composition of the U.S. as a whole. What must be kept in mind, however, is the variability in diversity that exists at the local level. A number of places approach an entropy value of 1, reflecting maximum diversity. Vallejo, CA, for example, exhibits a 2010 five-group E score of .94, with a population made up of similar shares of white (25.0%), black (22.6%), Hispanic (22.6%), and Asian (25.5%) residents. Other places hover near 0, with virtually all of their residents belonging to a single group. We favor the entropy index because the absolute standard on which it rests—equal group representation—facilitates cross-sectional and longitudinal comparisons for our large sample of places. Such comparisons are more difficult to make when place diversity is measured relative to the racial-ethnic mix of some larger spatiotemporal context (e.g., the surrounding metropolitan area or the national population in a particular year). We also like the congruence of the entropy index with an intuitive understanding of diversity; it tells us about the number and equality in size of the group-specific slices of the local ethnoracial pie.

Analyzing Trajectories

To describe common trajectories of diversity change throughout the 1980–2010 period, we use growth mixture models (or GMMs). From a substantive standpoint, the strength of the GMM approach is that it allows us to detect divergent and heterogeneous patterns of diversity change obscured by a traditional regression analysis which measures average change across our entire sample of places. Each community in the U.S. has had its own distinct experience with diversity, and GMMs allow us to look for commonalities in these experiences while also preserving some of their distinctiveness. From a statistical standpoint, GMMs are an extension both of latent class analysis and growth curve models. GMMs improve on simple panel-style descriptions of average change between time points and extend traditional growth modeling approaches, which assume that a single growth trajectory can describe an entire population of subjects (McCutcheon 1987; Preacher et al. 2008). GMMs relax this assumption and facilitate the estimation of different growth parameters for distinct (unobserved) subpopulations, resulting in separate models for each latent class. The GMM approach allows us to identify subsets of places that have unique diversity trajectories and patterns of change.

Following Jones et al. (2001), given a longitudinal sequence of values y, where y = (y1,y2,…,yT), we assume that there are unobserved subpopulations of places differing in their parameter values that can be expressed as:

where pk is the probability of belonging to class k with corresponding parameters λk, which depend on time.

Because the k subpopulations of places are unobserved, one must determine the value of k, or the number of unobserved groups, that best fit the data. We use the change in the Bayes Information Criterion (BIC) between a model with n classes and a model with n + 1 classes to determine the number of unobserved groups that best fits the data. Two metrics are helpful for this purpose. The first is the BIC log Bayes factor approximation (Arrandale et al. 2006; Jones et al. 2001):

where ΔBIC is the BIC of the more complex model minus the BIC of the simpler model. Values above 2 indicate that the more complex model fits better than the simpler model, while values less than 2 suggest that the more complex model fits worse than the simpler model. The second method is the Jeffreys’ scale, which uses the exponentiated differences between the BICs from the two models:

where BICi is the BIC of the more complex model and BICj is the BIC of the simpler model. Values less than 0.1 are strong evidence in support of the more complex model, while values greater than 10 are strong evidence in support of the simpler model (Arrandale et al. 2006; Nagin 2005).

We used the Stata traj command (Jones and Nagin 2007) to estimate place-level trajectories of ethnoracial diversity, measured by entropy scores, between 1980 and 2010. Using these four data points, we estimated models and obtained BICs starting with two unobserved latent groups of places (relative to one). We compared BICs for successively more complex models, and continued to add latent groups until both the Jeffreys’ scale and the BIC log Bayes factor approximations indicated that a more complex model (i.e., with one additional latent group) was a worse fit for the data. We also compared the BIC scores for models based on a linear time trend and a quadratic time trend and found that, for a given number of unobserved latent classes, the quadratic time trend always fit the data better than the linear time trend. The results for this procedure are reported in Appendix A. Our analysis of model fit yields seven distinct trajectories between 1980 and 2010 for all-white places, three distinct trajectories for mostly-white places, eight distinct trajectories for white-black places, and 15 distinct trajectories for white-Hispanic places.

After describing the mixture model results, we combine conceptually and statistically similar growth trajectories (within each type of 1980 place) based on panethnic group shares and changes over the 1980 to 2010 period in order to better facilitate interpretation of the pathways of racial-ethnic structural change that are associated with different trajectories. Specifically, we collapse the seven trajectories for the all-white places into four general types, retain all three of the trajectories for the mostly-white places, reduce the eight trajectories estimated via GMM for white-black places to four general types, and collapse the 15 trajectories for the white-Hispanic places into four types.6

Results

Basic Patterns

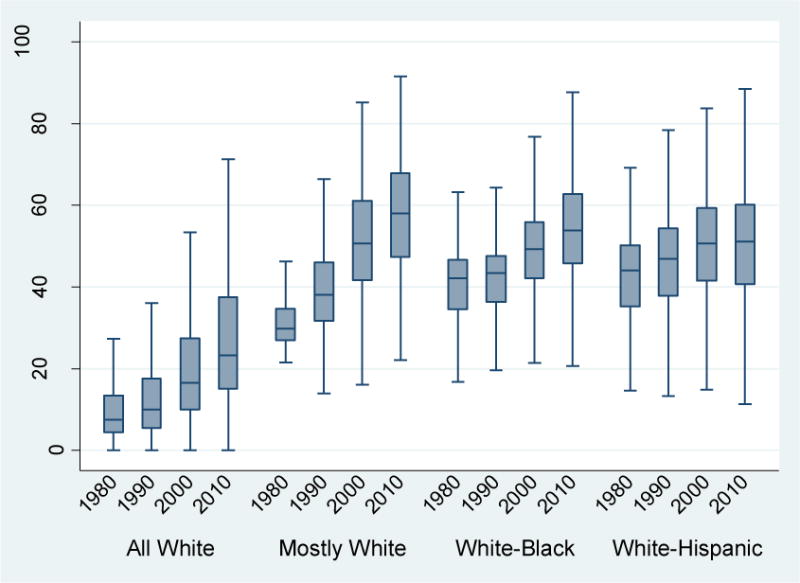

Our analysis highlights the varied pathways that communities have followed toward (or away from) ethnoracial diversity. This variation in patterns of diversity change is evident from the boxplots in Figure 1, which graphically communicate the year-specific distributions of E scores for places exhibiting each type of 1980 racial-ethnic structure. The general trend—illustrated by changes in median diversity (the horizontal line in the middle of each box) and consistent with our first hypothesis—is one of diversification, but the heterogeneity both across and within types of places is striking, as anticipated by hypothesis 2. Across pre-existing (1980) racial-ethnic structures, the plots show that diversity climbed rapidly in the typical all-white and mostly-white communities over the 1980–2010 period. Median levels of ethnoracial diversity also rose in white-black and white-Hispanic places albeit by a comparatively modest amount.

Figure 1.

Diversity Boxplots by 1980 Racial-Ethnic Structure, 1980–2010

The box plots also reveal substantial variation within types of places, conveyed by the height and spread of the bars. For all-white communities, the variation in diversity suggests that some changed extremely rapidly, with 809 (10.7%) achieving E scores above 50 by 2010. Other initially all-white places remained homogeneous, with 713 (9.4%) not reaching a diversity score of 10. Similar within-type heterogeneity in diversity trajectories is evident for the other types of communities. In white-black communities, most places became more diverse over time, but a nontrivial share (13.6%) became less diverse between 1980 and 2010. Among white-Hispanic communities, the share that “bucked the trend” of diversification stands out: nearly one in three (29.6%) had lower levels of diversity in 2010 than 1980.

These boxplots offer preliminary support for the segmented change framework. They emphasize that while the typical U.S. community—regardless of its initial racial-ethnic structure—has become more diverse, there is considerable variation in trajectories, with some places diversifying rapidly, others doing so more slowly, and still others exhibiting little change or becoming less diverse. The boxplots also offer preliminary evidence that diversification is conditioned partly by the initial racial-ethnic structure of a place. The sharpest increases appear in mostly-white places (as hypothesis 3 predicts), but comparatively less diversification has occurred in places with large 1980 black or Hispanic populations (adhering to hypotheses 4 and 5).

Trajectories by Community Type

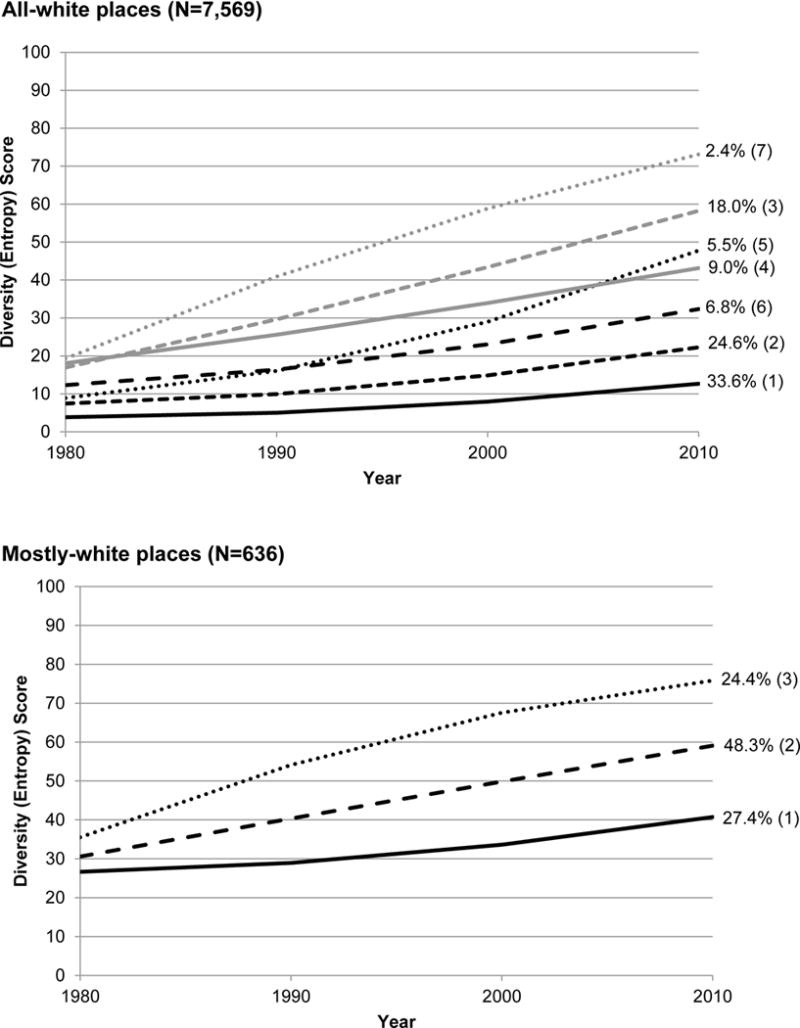

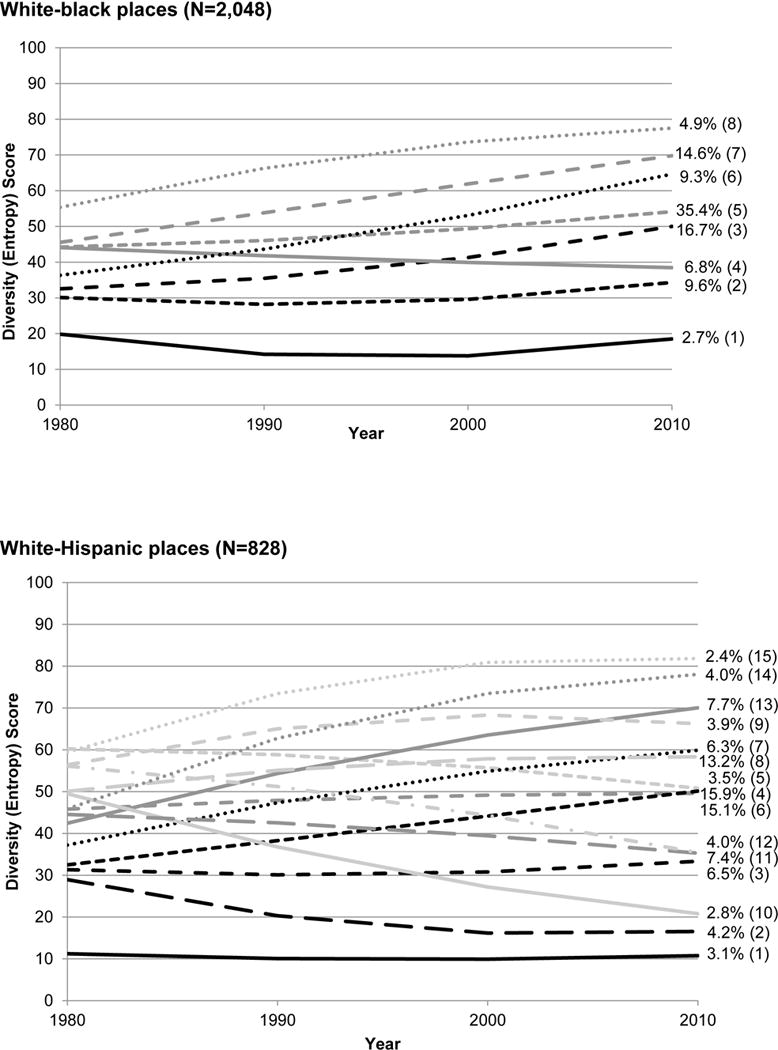

While useful as a descriptive exercise, the boxplot summaries do not capture the different types of diversity trajectories displayed by communities. Perhaps more importantly, they do not inform us about the components of racial change that drive diversification, nor do they indicate where—i.e., in what parts of the country—particular types of change are most common. To address these issues and to more formally unpack the variation in diversity patterns, we rely on growth mixture models (GMMs), which identify common trajectories of diversity that places followed during the 1980–2010 period. We report coefficients from the GMM estimators and fit statistics used to determine the preferred model (number of trajectories) in Appendix Tables A1 (model selection criteria) and A2 (GMM parameter estimates for best-fitting models). Graphical summaries of the GMM results for each of the four different types of communities are shown in Figures 2 and 3.

Figure 2.

Estimated Diversity Trajectories by 1980 Racial-Ethnic Structure, 1980–2010

Figure 3.

Estimated Diversity Trajectories by 1980 Racial-Ethnic Structure, 1980–2010

In 1980, two thirds (66.2%) of our sample communities were classified as all-white, meaning that their non-Hispanic white populations exceeded 90% of the total. By 2010, however, their racial-ethnic makeups were quite varied. The upper portion of Figure 2 presents GMM results for this group of places, showing average diversity scores by year for each of the estimated trajectories. The numbers to the right of the graph represent the percentage of all-white places falling in each trajectory and, in parentheses, the number assigned to each trajectory to facilitate correspondence with the Appendix tables.

The best-fitting model for all-white places yields seven distinct patterns of diversity change, all of which are upward sloping over time. However, the patterns vary in their starting value and especially in their pace of change. The modal pattern (trajectory #1) represented by the solid black line at the bottom of the graph—where 33.6% of the places are situated—reflects little change over the 1980–2010 period. The second largest trajectory (#2, including one-fourth of all-white places) features similarly low levels of diversification. Combined, these two trajectories capture nearly three-fifths of the communities that were classified as all-white in 1980. Although all-white places that reached high levels of diversity (represented by the grey dotted and dashed lines) are less common, they do exist. The Seattle suburb of Bellevue, for example, is one place in the top trajectory (#7) which rapidly diversified over this period, moving from an E score of 24.3 in 1980 to 66.1 in 2010.

The lower portion of Figure 2 shows the estimated trajectories for places that were categorized as mostly white in 1980. The growth mixture models predict less heterogeneity in this subset of places, identifying only three distinct types of diversity change. Communities in this category all had similar starting points, with initial E values in the high 20s to low 30s. What differentiates these places from one another is their pace of diversification. In line with our third hypothesis, all three trajectories slope upward, implying that the dominant tendency in communities that had modest levels of ethnoracial diversity in 1980 was toward increased diversity, but some places clearly diversified earlier and/or more rapidly than others. The trajectories taken by two Southern California communities—Arcadia and Dana Point—with equivalent initial diversity levels (1980 E = 29.4) illustrate this distinction. Located in the San Gabriel Valley of Los Angeles, Arcadia diversified rapidly over the next three decades in response to major Hispanic and Asian population growth (2010 E = 65.2). By contrast, diversity in Orange County’s Dana Point rose more slowly (2010 E = 46.7), largely due to a lack of non-Hispanic minority growth.

The trajectories of diversity change for places with sizeable nonwhite populations in 1980 are shown in Figure 3. Among white-black places (upper half of the figure), the GMMs identify eight distinct patterns of diversification. The large number of trajectories estimated for white-black communities is a function of considerable variation in initial diversity levels as well as variation in rates of diversity change. While the modal trajectory for white-black communities (the grey short-dash line representing 35.4% of these places [#5]) is upward sloping, the change in diversity over the 30-year period is relatively modest, from an average initial E score of 44.2 to an E of 54.1 in 2010. Consistent with hypothesis 4, patterns of diversity change for white-black communities are notable for their relative lack of diversification. Several of the trajectories for white-black places are basically flat: the solid black [#1], short-dash black [#2], and solid grey lines [#4] collectively represent about one-fifth of these places. Among the places with little diversity change are rustbelt cities like Detroit and East St. Louis, both of which actually became less diverse from 1980 to 2010, as well as many smaller towns in the Deep South.

The 828 communities identified in 1980 as white-Hispanic are especially variable in their diversity trends, offering some support for our fifth hypothesis. The lower portion of Figure 3 shows the 15 estimated trajectories for these places. Like white-black places, their diversity trajectories differ in starting points and rates of change. The dominant trajectory (short-dash black line [#4]) depicts modest diversification, but it captures just 15.9% of white-Hispanic places. For the most part, other types of change are upward sloping, yet several trajectories slope downward, reflecting places that became less diverse over the course of the last three decades. Many communities defined by descending trajectories (e.g., long-dash black [#2] and solid grey lines [#10]) are located in border states and have histories of Mexican settlement that often predate municipal incorporation. However, other white-Hispanic communities that became less diverse during the study period are found in parts of the Pacific Northwest, where agricultural demands have long attracted Hispanic laborers.

Pathways of Change

The GMM results document several common patterns since 1980. They show that all-white and mostly-white places have tended to become more racially diverse, white-black communities have remained relatively stable in diversity level (or have increased only moderately), and white-Hispanic places have displayed a wide range of diversity outcomes. Yet the models say little about the specific ethnoracial (or panethnic) pathways that produce these divergent diversity trajectories. That is, a key unanswered question is whether the estimated trajectories are defined by common shifts in their underlying racial-ethnic structures. To address this question, we collapse specific trajectories that share similar ethnoracial profiles of change into broad trajectory categories or types and then calculate weighted (by the number of places in each trajectory) means of their racial compositions in 1980 and 2010. To provide additional context, we also summarize their regional concentrations and their locations within metropolitan, micropolitan, or rural areas. Detailed breakdowns for each of the individual trajectories that we have collapsed can be found in the tables in Appendix C.

The racial-ethnic structures associated with the trajectories of diversity change for all-white places are shown in Table 1. The seven trajectories estimated via GMM have been reduced to four general types. The all-white places that experienced effectively no change in diversity level (i.e., “stably all-white”) comprise a solid majority (58.4%) and are overrepresented in nonmetro areas of the Midwest and Northeast (with very little representation in the West). Among places that showed non-trivial diversity change, the most common pathway involved relative growth in their Hispanic populations. We separate these places into “slight” and “modest” Hispanic growth categories, as the former remained largely white by 2010 while Hispanic expansion in the latter led to more rapid diversification. Nevertheless, both types of places were common in all regions of the country and were noticeably more urbanized than their stably-white counterparts. The final trajectory category experienced much more rapid change, via “multi-ethnic growth” that sharply boosted minority group proportions across the board. Unlike the places diversifying solely through Hispanic growth, these places were heavily concentrated in metropolitan areas, especially in the South. As an example of this type of change, consider Lilburn, GA, a small Atlanta suburb that is home to the largest Hindu temple outside of India. Between 1980 and 2010, Lilburn transitioned from a place that was 98.2% white to one where no single racial group constituted a majority, whites making up 39.3% of the population, blacks 15.9%, Asians 15.2% and Hispanics 27.4%.

Table 1.

Racial Composition of 1980 All-White Place Trajectories, 1980–2010

| Stably All-White | Slight Hispanic Growth | Modest Hispanic Growth | Multi-Ethnic Growth | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Share | ||||

| 1980 | .98 | .96 | .95 | .94 |

| 2010 | .94 | .87 | .78 | .61 |

| Black Share | ||||

| 1980 | .00 | .02 | .02 | .02 |

| 2010 | .01 | .03 | .06 | .12 |

| Hispanic Share | ||||

| 1980 | .01 | .01 | .02 | .03 |

| 2010 | .02 | .06 | .10 | .18 |

| Asian Share | ||||

| 1980 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .01 |

| 2010 | .01 | .02 | .03 | .07 |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | .28 | .22 | .21 | .24 |

| Midwest | .53 | .33 | .27 | .20 |

| South | .15 | .26 | .30 | .38 |

| West | .04 | .18 | .22 | .18 |

| Area | ||||

| Metro | .54 | .66 | .75 | .89 |

| Micro | .21 | .20 | .13 | .08 |

| Rural | .25 | .15 | .12 | .03 |

| N of places | 4419 | 1,364 | 1,092 | 694 |

| % of all-whites places | 58.4 | 18.0 | 14.4 | 9.2 |

Notes: Weighted by trajectory shares; composition of general types by trajectory numbers: Stably All-White (1–2); Slight Hispanic Growth (3); Modest Hispanic Growth (4–5); Multi-Ethnic Growth (6–7). Detailed breakdowns shown in Appendix C.

Racial-ethnic compositional shifts for mostly-white communities are presented in Table 2. Here, the three distinct diversity trajectories align with three distinct pathways of ethnoracial change. The first set of places, which had the lowest rates of diversification, changed mostly via slight Hispanic growth and relative stability in the shares of other minority groups. Communities following this pathway were located mainly in the South and in both metropolitan and nonmetropolitan settings. Harrodsburg, a small rural town in central Kentucky, which lays claim to being the oldest city in the state, serves as a good example. In both 1980 and 2010, Harrodsburg had a dominant white-majority population (~85%) accompanied by a small black population (~8%). But between those years modest Hispanic growth, which boosted the Hispanic share from 0% to 4%, contributed to a slight uptick in overall diversity. The two other trajectories for mostly-white communities are associated with more pronounced patterns of compositional change. The differentiating factor here is simply the magnitude of non-white population growth. The most rapidly diversifying places (in the “strong multiethnic growth” category) saw large-scale increases in all minority groups and fairly dramatic declines in white population shares. Unlike the slowly-diversifying Harrodsburgs, these communities were found almost exclusively in metropolitan areas and mainly in the South and West. This type of rapid change occurred in some of the largest multiethnic cities such as Seattle and St. Paul, but also in booming suburban communities such as Bolingbrook, IL and Herndon, VA where accessible locations and affordable housing made for attractive areas of settlement.

Table 2.

Racial Composition of 1980 Mostly-White Place Trajectories, 1980–2010

| Slight Hispanic Growth | Moderate Multi-Ethnic Growth | Strong Multi-Ethnic Growth | |

|---|---|---|---|

| White Share | |||

| 1980 | .89 | .87 | .85 |

| 2010 | .81 | .65 | .45 |

| Black Share | |||

| 1980 | .05 | .05 | .05 |

| 2010 | .05 | .08 | .15 |

| Hispanic Share | |||

| 1980 | .04 | .05 | .05 |

| 2010 | .09 | .17 | .24 |

| Asian Share | |||

| 1980 | .01 | .02 | .03 |

| 2010 | .01 | .05 | .12 |

| Region | |||

| Northeast | .14 | .19 | .15 |

| Midwest | .17 | .13 | .09 |

| South | .43 | .34 | .41 |

| West | .26 | .34 | .35 |

| Area | |||

| Metro | .57 | .80 | .95 |

| Micro | .24 | .12 | .04 |

| Rural | .19 | .08 | .01 |

| N of places | 174 | 307 | 155 |

| % of mostly-white places | 27.4 | 48.3 | 24.4 |

Notes: Composition of general types by trajectory numbers: Slight Hispanic Growth (1); Moderate Multi-Ethnic Growth (2); Strong Multi-Ethnic Growth (3)

Table 3 shows the common racial-ethnic pathways for white-black communities. As was evident in the diversity trajectories for these places (Figure 3), they are unique relative to the other types of communities in terms of their stability, consistent with our fourth hypothesis. The first two broad types of pathways in the table capture more than a quarter of all white-black places and exhibit few signs of racial change between 1980 and 2010. Both types are concentrated in the South but have some presence in the Midwest as well. The third type (“white decline/black growth”) is the modal pathway and refers to the 42% of places where black shares increased fairly steeply during the 30-year period. These communities, almost all Southern and disproportionately rural, witnessed large reductions in their white population shares and no notable changes among the other non-black groups. Included in this category is the poor rural town of Allendale, SC whose steady population decline over the last three decades has accompanied a substantial reduction in the white share of residents (from 34% to 12%) and a spike in the black share (from 64% to 83%) The last general type of racial change consists of 29% of formerly white-black communities where diversity appears to have taken root. In addition to their concentration in Southern metropolitan areas, what unites these places is that diversity was achieved through increasing Hispanic and black representation and white decline.

Table 3.

Racial Composition of 1980 White-Black Place Trajectories, 1980–2010

| Dominantly Black | Stably White-Black | White Decline/Black Growth | White Decline/Hispanic Growth | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Share | ||||

| 1980 | .21 | .78 | .59 | .70 |

| 2010 | .18 | .71 | .45 | .47 |

| Black Share | ||||

| 1980 | .77 | .20 | .39 | .25 |

| 2010 | .79 | .22 | .48 | .30 |

| Hispanic Share | ||||

| 1980 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .03 |

| 2010 | .02 | .04 | .04 | .17 |

| Asian Share | ||||

| 1980 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 |

| 2010 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .03 |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | .04 | .06 | .02 | .15 |

| Midwest | .33 | .12 | .07 | .10 |

| South | .64 | .81 | .90 | .72 |

| West | .00 | .00 | .01 | .03 |

| Area | ||||

| Metro | .65 | .57 | .46 | .75 |

| Micro | .27 | .24 | .24 | .15 |

| Rural | .07 | .19 | .31 | .10 |

| N of places | 55 | 538 | 865 | 590 |

| N of white-black places | 2.7 | 26.3 | 42.2 | 28.8 |

Notes: Weighted by trajectory shares; composition of general types by trajectory numbers: Dominantly Black (1); Stably White-Black (2–3); White Decline/Black Growth (4–5); White Decline/Hispanic Growth (6–8). Detailed breakdowns shown in Appendix C.

Finally, the ethnoracial pathways associated with the multitude of white-Hispanic trajectories are combined into four general types and summarized in Table 4. The first type, though infrequent (just 7.4% of all places), comprises places with very high Hispanic shares in both 1980 and 2010. Without exception, these places are located in states bordering Mexico. Indeed, many are situated right on the border, including Brownsville, TX, Nogales, AZ, and Calexico, CA, each of which has a long history of Mexican settlement. The second, and largest (41%), type of white-Hispanic pathway is defined by stability, with both white and Hispanic population shares remaining substantial over time and other groups largely absent. Places in this category are concentrated in border states but also throughout the Mountain West, the Pacific Northwest, and parts of the Midwest. The third type, which encompasses more than a third of all places considered white-Hispanic in 1980, is defined by ethnoracial pathways involving dramatic Latino growth and white decline. This set of places is found in the metropolitan South and West and includes urban cores like El Paso and the nearby bedroom community of Horizon City; both places boast Hispanic shares greater than 80%. The final trajectory type contains 14.1% of initially white-Hispanic communities and exhibits significant white declines and increases in all non-white population shares. This pattern of racial change is largely limited to major California cities (e.g., Anaheim, Fresno, San Diego, San Jose) and nearby suburbs.

Table 4.

Racial Composition of 1980 White-Hispanic Place Trajectories, 1980–2010

| Dominantly Hispanic | Stably White-Hispanic | Hispanic Growth/White Decline | Non-White Growth | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White Share | ||||

| 1980 | .10 | .64 | .58 | .75 |

| 2010 | .05 | .50 | .31 | .39 |

| Black Share | ||||

| 1980 | .00 | .01 | .03 | .03 |

| 2010 | .00 | .01 | .03 | .07 |

| Hispanic Share | ||||

| 1980 | .89 | .33 | .36 | .18 |

| 2010 | .91 | .45 | .61 | .38 |

| Asian Share | ||||

| 1980 | .00 | .01 | .02 | .03 |

| 2010 | .00 | .02 | .03 | .12 |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | .00 | .02 | .03 | .06 |

| Midwest | .00 | .08 | .02 | .02 |

| South | .62 | .37 | .28 | .10 |

| West | .38 | .53 | .67 | .82 |

| Area | ||||

| Metro | .74 | .48 | .76 | .96 |

| Micro | .11 | .24 | .13 | .01 |

| Rural | .15 | .29 | .12 | .03 |

| N of places | 61 | 340 | 310 | 117 |

| % of white-Hispanic places | 7.4 | 41.1 | 37.4 | 14.1 |

Notes: Weighted by trajectory shares; composition of general types by trajectory numbers: Dominantly Hispanic (1–2); Stably White-Hispanic (3–6); Hispanic Growth/White Decline (7–12); Non-White Growth (13–15). Detailed breakdowns shown in Appendix C.

Conclusion

The diversification of the U.S. population is one of the most salient demographic trends of recent decades. Fueled by immigration and maintained via racial differences in natural increase, continued growth in racial and ethnic diversity appears certain. Yet while the face of the nation has steadily evolved, the pace of diversification—not to mention its presence—has mapped unevenly across the residential landscape. Our goal here has been to document variation at the local level around the presumed “master trend” toward greater diversity. We used census data to describe heterogeneity in ethnoracial diversity change for a large sample of places between 1980 and 2010, employing growth mixture models to identify distinct trajectories of change and the racial-ethnic pathways that determine diversity outcomes.

Our analysis lends itself to several noteworthy conclusions. Consistent with expectations, American communities are more diverse now than they were three decades ago. However, marked variability exists among them in both diversity levels and the speed of diversification. To help explain this variation, we propose a segmented change framework that underscores the central role played by a place’s initial racial-ethnic structure in conditioning its subsequent diversity trajectory. The framework also draws on spatial assimilation and ethnic stratification perspectives to highlight the sorting processes that make diversification unlikely to occur in a uniform manner across places. Namely, group-specific socioeconomic attainments combine with residential preferences and external constraints (e.g., discrimination, housing policies, zoning restrictions) to create the conditions under which diversity can thrive or not.

Our results largely align with this conceptual framework. Communities that were mostly white but had a modest minority presence in 1980 manifested near-universal upward-sloping diversity trajectories over the next 30 years. Given that these places—and thus their inhabitants—had already shown some willingness to diversify, it is reasonable to predict that they would continue to do so. All-white communities, comprising more than two-thirds of our sample places in 1980, were much more variable. About one-quarter of these places underwent substantial ethnoracial change, due either to Hispanic population growth or the entry of multiple ethnic groups. But an even larger share of the all-white places did not experience any meaningful racial change; over half remained overwhelmingly white.

Diversity trajectories for communities with black or Hispanic residents varied even more. A nontrivial number of places with a visible black presence in 1980 saw their diversity rise. However, in line with the hypothesis that factors such as discrimination and racial stigmatization limit ethnoracial diversity from taking root, levels of diversity in a great number of these places remained essentially fixed over the 1980–2010 period. Indeed, the one clear pattern of diversity change in blacker communities occurred through white population loss. When diversification did happen, it was because Hispanic growth outpaced white decline.

Communities with substantial 1980 Hispanic shares exhibited the widest range of diversity pathways, some rapidly diversifying and others becoming more homogeneous. At first glance Hispanic places seemed more susceptible to diversification, but their pathways of change often mirrored those in blacker communities, with diversity driven by relative white population loss. This particular pathway characterized more than one-third of formerly white-Hispanic places. By contrast, only a small percentage of these places (albeit mainly large urban centers) diversified in truly multiethnic ways.

Taken together, our findings confirm the uneven spread of diversity across American communities: some have diversified rapidly, some have done so more slowly, and others have become more racially homogeneous. Most significantly, these divergent diversity trajectories appear to be structured along racial lines. Communities initially defined by blacker and browner populations not only are less likely than whiter places to experience rapid diversification, but any diversity increases that do occur will be fueled primarily by Latino growth and white loss. Theoretically, these patterns conform to the ethnic stratification perspective nested within our segmented change framework, suggesting that legacies of racial discrimination and segregation in blacker (and to a lesser extent, Latino) communities stigmatize places in a way that makes diversification progress more slowly, if at all. Thus, the popular narrative of diversity diffusing ubiquitously throughout the United States fails to acknowledge how racial stratification and spatial sorting processes structure the possibilities for—and ultimately, exposure to—diversity. While we do not foresee an ethnically-balkanized American future, higher, stable levels of ethnoracial diversity may be out of reach for historically black communities and many places of longstanding Hispanic settlement.

Appendix A

BIC Output for Growth Mixture Models

| Categorization in 1980 | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # Groups | All White | Mostly White | White-Black | White-Hispanic | ||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||

| N=7,569 | N=636 | N=2,048 | N=828 | |||||||||

| Quad | 2ΔBIC | e(BICi-BICj) | Quad | 2ΔBIC | e(BICi-BICj) | Quad | 2ΔBIC | e(BICi-BICj) | Quad | 2ΔBIC | e(BICi-BICj) | |

|

|

||||||||||||

| 2 | −106877.7 | −9249.2 | −30503.1 | −12972.9 | ||||||||

| 3 | −101987.5 | 9,780.4 | 0 | −8923.2 | 651.9 | 2.7376E-142 | −29428.0 | 30503.1 | 0 | −12929.4 | 87.0 | 1.29579E-19 |

| 4 | −99497.1 | 4,980.8 | 0 | −8938.9 | −31.4 | 6452640.6 | −28999.5 | 857.0 | 8.0318E-187 | −12500.1 | 858.5 | 3.7562E-187 |

| 5 | −98201.1 | 2,592.1 | 0 | −28759.4 | 480.2 | 5.2145E-105 | −12321.7 | 356.8 | 3.35898E-78 | |||

| 6 | −97477.9 | 1,446.4 | 0 | −28628.0 | 262.9 | 8.3306E-58 | −12181.0 | 281.4 | 7.84813E-62 | |||

| 7 | −96775.8 | 1,404.1 | 1.2442E-305 | −28415.2 | 425.5 | 3.97655E-93 | −12093.2 | 175.7 | 7.17655E-39 | |||

| 8 | −96796.5 | −41.3 | 920106516.4 | −28288.2 | 254.1 | 6.58481E-56 | −12022.6 | 141.3 | 2.07537E-31 | |||

| 9 | −28306.2 | −36.0 | 66986388.5 | −11959.8 | 125.5 | 5.59785E-28 | ||||||

| 10 | −11936.6 | 46.5 | 8.07228E-11 | |||||||||

| 11 | −11864.8 | 143.5 | 6.97773E-32 | |||||||||

| 12 | −11839.7 | 50.3 | 1.17168E-11 | |||||||||

| 13 | −11815.6 | 48.1 | 3.59102E-11 | |||||||||

| 14 | −11774.1 | 83.0 | 9.29166E-19 | |||||||||

| 15 | −11767.9 | 12.3 | 0.0021 | |||||||||

| 16 | −11774.4 | −13.0 | 671.8264 | |||||||||

Appendix B

Results from Growth Mixture Models of Racial Diversity Trajectories from 1980–2010, by 1980 Racial Composition

| All White | Mostly White | White-Black | White-Hispanic | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trajectory | Parameter | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE | Coeff. | SE |

| 1 | Intercept | 3.845 | 0.085 | 26.635 | 0.479 | 19.821 | 0.844 | 10.809 | 1.374 |

| Linear | 0.028 | 0.013 | 0.11 | 0.08 | −0.818 | 0.121 | −0.158 | 0.158 | |

| Quadratic | 0.009 | 0 | 0.012 | 0.002 | 0.026 | 0.004 | 0.005 | 0.005 | |

| 2 | Intercept | 7.457 | 0.124 | 30.571 | 0.379 | 30.105 | 0.412 | 27.784 | 1.368 |

| Linear | 0.125 | 0.015 | 0.991 | 0.065 | −0.359 | 0.066 | −0.984 | 0.146 | |

| Quadratic | 0.012 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.002 | 0.017 | 0.002 | 0.02 | 0.004 | |

| 3 | Intercept | 12.309 | 0.173 | 35.538 | 0.53 | 32.53 | 0.354 | 31.785 | 0.722 |

| Linear | 0.277 | 0.019 | 2.117 | 0.083 | 0.148 | 0.048 | −0.237 | 0.112 | |

| Quadratic | 0.013 | 0.001 | −0.026 | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.002 | 0.009 | 0.003 | |

| 4 | Intercept | 8.9 | 0.254 | 44.072 | 0.524 | 32.545 | 0.484 | ||

| Linear | 0.425 | 0.036 | −0.246 | 0.076 | 0.526 | 0.094 | |||

| Quadratic | 0.029 | 0.001 | 0.002 | 0.002 | 0.001 | 0.003 | |||

| 5 | Intercept | 16.942 | 0.202 | 44.222 | 0.247 | 49.806 | 1.194 | ||

| Linear | 1.214 | 0.032 | 0.105 | 0.033 | −1.634 | 0.201 | |||

| Quadratic | 0.005 | 0.001 | 0.007 | 0.001 | 0.021 | 0.006 | |||

| 6 | Intercept | 19.341 | 0.318 | 36.336 | 0.75 | 45.313 | 0.631 | ||

| Linear | 2.339 | 0.053 | 0.62 | 0.067 | 0.243 | 0.075 | |||

| Quadratic | −0.018 | 0.002 | 0.011 | 0.002 | −0.004 | 0.002 | |||

| 7 | Intercept | 18.086 | 0.193 | 45.528 | 0.416 | 35.875 | 1.987 | ||

| Linear | 0.707 | 0.028 | 0.836 | 0.051 | 1.177 | 0.134 | |||

| Quadratic | 0.004 | 0.001 | −0.001 | 0.002 | −0.013 | 0.004 | |||

| 8 | Intercept | 55.367 | 0.585 | 47.232 | 0.766 | ||||

| Linear | 1.264 | 0.085 | −0.218 | 0.102 | |||||

| Quadratic | −0.018 | 0.003 | −0.007 | 0.003 | |||||

| 9 | Intercept | 42.629 | 0.854 | ||||||

| Linear | 1.299 | 0.12 | |||||||

| Quadratic | −0.013 | 0.004 | |||||||

| 10 | Intercept | 48.829 | 1.464 | ||||||

| Linear | 0.629 | 0.086 | |||||||

| Quadratic | −0.011 | 0.003 | |||||||

| 11 | Intercept | 45.574 | 1.055 | ||||||

| Linear | 1.993 | 0.138 | |||||||

| Quadratic | −0.03 | 0.004 | |||||||

| 12 | Intercept | 58.786 | 1.248 | ||||||

| Linear | −0.193 | 0.151 | |||||||

| Quadratic | −0.009 | 0.004 | |||||||

| 13 | Intercept | 55.489 | 1.082 | ||||||

| Linear | 1.333 | 0.153 | |||||||

| Quadratic | −0.031 | 0.005 | |||||||

| 14 | Intercept | 59.385 | 1.338 | ||||||

| Linear | 1.733 | 0.174 | |||||||

| Quadratic | −0.033 | 0.005 | |||||||

| 15 | Intercept | 59.022 | 2.205 | ||||||

| Linear | 0.246 | 0.23 | |||||||

| Quadratic | −0.009 | 0.005 | |||||||

| N | 7,569 | 636 | 2,084 | 828 | |||||

Appendix Table C1

Racial Composition of 1980 All-White Place Trajectories, 1980–2010

| Stably All-White | Slight Hispanic Growth | Modest Hispanic Growth | Multi-Ethnic Growth | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||

| Trajectory # | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| White Share | |||||||

| 1980 | .99 | .98 | .96 | .93 | .97 | .94 | .93 |

| 2010 | .96 | .92 | .87 | .79 | .76 | .65 | .48 |

| Black Share | |||||||

| 1980 | .00 | .01 | .02 | .02 | .01 | .02 | .02 |

| 2010 | .01 | .01 | .03 | .05 | .07 | .10 | .17 |

| Hispanic Share | |||||||

| 1980 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .02 | .01 | .02 | .03 |

| 2010 | .02 | .03 | .06 | .10 | .12 | .16 | .22 |

| Asian Share | |||||||

| 1980 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .01 |

| 2010 | .00 | .01 | .02 | .03 | .03 | .06 | .09 |

| Region | |||||||

| Northeast | .29 | .28 | .22 | .20 | .23 | .23 | .27 |

| Midwest | .57 | .47 | .33 | .19 | .41 | .23 | .12 |

| South | .13 | .17 | .26 | .31 | .29 | .34 | .49 |

| West | .01 | .09 | .18 | .30 | .08 | .20 | .12 |

| Area | |||||||

| Metro | .48 | .62 | .66 | .72 | .80 | .87 | .96 |

| Micro | .23 | .18 | .20 | .16 | .08 | .10 | .02 |

| Rural | .28 | .20 | .15 | .12 | .12 | .03 | .02 |

| N of places | 2,558 | 1,861 | 1,364 | 678 | 414 | 515 | 179 |

| Trajectory % | 33.8 | 24.6 | 18.0 | 9.0 | 5.5 | 6.8 | 2.4 |

Appendix Table C2

Racial Composition of 1980 White-Black Place Trajectories, 1980–2010

| Dominantly Black | Stably White | White Decline/Black Growth | White Decline/Hispanic Growth | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||||

| Trajectory # | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| White Share | ||||||||

| 1980 | .21 | .74 | .80 | .49 | .61 | .79 | .67 | .61 |

| 2010 | .18 | .72 | .71 | .31 | .48 | .56 | .45 | .34 |

| Black Share | ||||||||

| 1980 | .77 | .25 | .18 | .49 | .37 | .19 | .28 | .29 |

| 2010 | .79 | .23 | .21 | .66 | .45 | .27 | .32 | .31 |

| Hispanic Share | ||||||||

| 1980 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .01 | .03 | .06 |

| 2010 | .02 | .03 | .05 | .02 | .04 | .13 | .17 | .26 |

| Asian Share | ||||||||

| 1980 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .02 |

| 2010 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .02 | .02 | .06 |

| Region | ||||||||

| Northeast | .04 | .06 | .06 | .01 | .03 | .06 | .15 | .33 |

| Midwest | .33 | .16 | .10 | .10 | .06 | .14 | .08 | .08 |

| South | .64 | .78 | .83 | .88 | .90 | .80 | .74 | .50 |

| West | .00 | .01 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .00 | .03 | .09 |

| Area | ||||||||

| Metro | .65 | .53 | .59 | .45 | .46 | .72 | .71 | .91 |

| Micro | .27 | .26 | .23 | .24 | .24 | .15 | .19 | .06 |

| Rural | .07 | .20 | .18 | .31 | .30 | .13 | .10 | .03 |

| N of places | 55 | 197 | 341 | 140 | 725 | 191 | 299 | 100 |

| Trajectory % | 2.7 | 9.6 | 16.7 | 6.8 | 35.4 | 9.3 | 14.6 | 4.9 |

Appendix Table C3

Racial Composition of 1980 White-Hispanic Place Trajectories, 1980–2010

| Dominantly Hispanic | Stably White-Hispanic | Hispanic Growth/White Decline | Non-White Growth | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||||||||||||

| Trajectory # | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 |

| White Share | |||||||||||||||

| 1980 | .04 | .15 | .53 | .59 | .48 | .79 | .81 | .65 | .64 | .43 | .45 | .30 | .77 | .77 | .65 |

| 2010 | .03 | .07 | .47 | .43 | .31 | .62 | .52 | .41 | .29 | .16 | .16 | .05 | .45 | .35 | .29 |

| Black Share | |||||||||||||||

| 1980 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .06 | .01 | .01 | .03 | .05 | .01 | .04 | .03 | .02 | .03 | .06 |

| 2010 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .04 | .01 | .03 | .03 | .06 | .01 | .03 | .01 | .06 | .08 | .09 |

| Hispanic Share | |||||||||||||||

| 1980 | .96 | .84 | .46 | .38 | .42 | .19 | .16 | .30 | .27 | .54 | .46 | .64 | .17 | .15 | .22 |

| 2010 | .97 | .86 | .50 | .53 | .55 | .33 | .40 | .51 | .51 | .81 | .76 | .93 | .38 | .37 | .38 |

| Asian Share | |||||||||||||||

| 1980 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .00 | .03 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .03 | .01 | .03 | .03 | .02 | .03 | .05 |

| 2010 | .00 | .00 | .01 | .01 | .07 | .01 | .03 | .02 | .10 | .01 | .04 | .01 | .08 | .16 | .21 |

| Region | |||||||||||||||

| Northeast | .00 | .00 | .00 | .02 | .07 | .01 | .04 | .02 | .06 | .00 | .02 | .03 | .08 | .06 | .00 |

| Midwest | .00 | .00 | .15 | .01 | .00 | .14 | .08 | .01 | .00 | .00 | .02 | .00 | .03 | .00 | .00 |

| South | .73 | .54 | .39 | .47 | .38 | .26 | .27 | .38 | .09 | .04 | .33 | .24 | .14 | .06 | .05 |

| West | .27 | .46 | .46 | .50 | .55 | .58 | .62 | .60 | .84 | .96 | .64 | .73 | .75 | .88 | .95 |

| Area | |||||||||||||||

| Metro | .73 | .74 | .43 | .43 | .86 | .46 | .85 | .59 | .91 | 1.00 | .79 | .82 | .95 | .97 | 1.00 |

| Micro | .12 | .11 | .33 | .20 | .07 | .26 | .12 | .20 | .09 | .00 | .10 | .06 | .02 | .00 | .00 |

| Rural | .15 | .14 | .24 | .36 | .07 | .28 | .04 | .21 | .00 | .00 | .11 | .12 | .03 | .03 | .00 |

| N of places | 26 | 35 | 54 | 132 | 29 | 125 | 52 | 109 | 32 | 23 | 61 | 33 | 64 | 33 | 20 |

| Trajectory % | 3.1 | 4.2 | 6.5 | 15.9 | 3.5 | 15.1 | 6.3 | 13.2 | 3.9 | 2.8 | 7.4 | 4.0 | 7.7 | 4.0 | 2.4 |

Footnotes

Support for this research has been provided by a grant from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD074605, awarded to PI Barrett Lee). Additional support comes from the Population Research Institute of Penn State University, which receives infrastructure funding from NICHHD (R24HD041025). The content of the paper is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not reflect the official views of the National Institutes of Health. We are grateful to two reviewers and the Editors for their helpful comments and to Liz Roberto for valuable feedback on an earlier draft.

By way of conceptual clarification, we consider the Hispanic/Latino and non-Hispanic white, black, and Asian populations “panethnic” because they each contain multiple subpopulations that qualify as ethnic groups. Members of an “ethnic group” recognize a common ancestry, history, and cultural tradition, although identification with this tradition varies across individuals and over time. Persons belonging to a “racial group” tend to be assigned to it by others based on perceived physical attributes (skin color, hair texture, etc.) that are regarded as inherent (Cornell and Hartmann 1998). The socially constructed nature of race and ethnicity contributes to an overlap in definitions; many groups are both racial and ethnic in nature. For that reason, we use the terms “ethnoracial” and “race-ethnicity” interchangeably throughout. We also use the terms “white” and “non-Hispanic white” interchangeably.

“Place stratification” scholarship typically focuses on discrimination, zoning, and other types of external constraints. We use the term “ethnic stratification” to reflect our broader view of the forces (including racial residential preferences and own-group affinity) that limit community ethnoracial diversity.

Census-designated places (CDPs) tend to be slightly smaller in population size. In 2010 the median CDP had a population of 3,308, while the median incorporated place had 3,394 residents. CDPs are also moderately more ethnoracially diverse, with a 2010 average diversity level (measured by the entropy index) of 38.9 compared to 36.1 for incorporated places.

As a sensitivity check, we have computed a ratio of the 2010 bounded size of each place (in square miles) to its 1980 size. The ratio can be used to identify places losing land, remaining stable, or annexing land during the observation period. Three conclusions stand out from this exercise: (1) less than three-tenths of all places in our sample increased their areal size by as much as 50% over the three decades of interest; (2) roughly four-tenths remained stable in size or lost land; and (3) mean 1980 and 2010 diversity levels are quite similar across the shrinking, stable, and expanding categories of places.

Falling outside of our classification scheme are the handful of places with dominant Asian populations, those few that were racially mixed in 1980, and those that had substantial non-Hispanic “other” populations (mostly places with large numbers of Native Americans).

For the places determined to be all-white in 1980, the four general types are: stably all-white (< 2 percentage-point average change in any nonwhite group); slight Hispanic growth (2–5 point growth in Hispanic share but < 2 point change in any other minority group share); Hispanic growth (> 5 point growth in Hispanic shares and little change in other minority groups); and multi-ethnic growth (> 5 point growth in each minority group share). For the mostly-white places, we retain all three trajectory types estimated by the GMMs (slight Hispanic growth, moderate multiethnic growth, and strong multiethnic growth). Among the places considered white-black in 1980, the four general types are: dominantly black (majority black population throughout the period and little change in all other panethnic group shares); stably white-black (majority-white population throughout the period and little change in other group shares); white decline/black growth (10+ point reduction in white shares and ~10 point increase in black share; little change in other group shares); white decline/Hispanic growth (10+ point reduction in white share and > 10 point increase in Latino share; little change in other group shares). Lastly, we reduce the 15 white-Hispanic trajectories into four types: dominantly Hispanic (large majority Hispanic throughout the period and no growth in white share); stably white-Hispanic (< 20 point change in white and Hispanic shares); Hispanic growth/white decline (20+ point decline in white share, 20+ point increase in Hispanic share, and little change for the other groups); and non-white growth (20+ point decline in white share, > 10 point increase in Hispanic share, and > 10 point increase in other group shares combined).

Contributor Information

Matthew Hall, Cornell University.

Laura Tach, Cornell University.

Barrett A. Lee, Penn State University

References

- Abascal Maria, Delia Baldassarri. Love thy Neighbor? Ethnoracial Diversity and Trust Reexamined. American Journal of Sociology. 2015;121:722–782. doi: 10.1086/683144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alba Richard D, Logan John R. Variations on Two Themes: Racial and Ethnic Patterns in the Attainment of Suburban Residence. Demography. 1991;28:431–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen James P, Turner Eugene J. The Most Ethnically Diverse Places in the United States. Urban Geography. 1989;10:523–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bean Frank D, Stevens Gillian. America’s Newcomers and the Dynamics of Diversity. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas George J. Heaven’s Gate: Immigration Policy and the American Economy. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Charles Camille Zubrinsky. Won’t You Be My Neighbor? Race, Class, and Residence in Los Angeles. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Charles Camille Zubrinsky. Comfort Zones: Immigration, Acculturation, and the Neighborhood Racial Composition Preferences of Latinos and Asians. DuBois Review. 2007;4:41–77. [Google Scholar]

- Colby Sandra L, Ortman Jennifer M. Current Population Reports. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2015. Projections of the Size and Composition of the U.S. Population: 2014 to 2060; pp. 25–1143. [Google Scholar]

- Cornell Stephen, Douglas Hartmann. Ethnicity and Race: Making Identities in a Changing World. Thousand Oaks, CA: Pine Forge; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Crowder Kyle, Matthew Hall, Tolnay Stewart E. Neighborhood Immigration and Native Out-Migration. American Sociological Review. 2011;76:25–47. doi: 10.1177/0003122410396197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeFina Robert, Lance Hannon. Diversity, Racial Threat, and Metropolitan Housing Segregation. Social Forces. 2009;88:373–94. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell Chad R. Immigrant Suburbanization and the Shifting Geographic Structure of Metropolitan Segregation in the United States. Urban Studies. 2016;53:57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Farrell Chad R, Lee Barrett A. Racial Diversity and Change in Metropolitan Neighborhoods. Social Science Research. 2011;40:1108–23. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2011.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer Claude S, Michael Hout. Century of Difference: How America Changed in the Last Hundred Years. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Flores Ronald JO, Peter Lobo Arun. The Reassertion of a Black/Non-Black Color Line: The Rise in Integrated Neighborhoods without Blacks in New York City, 1970–2010. Journal of Urban Affairs. 2013;35:255–82. [Google Scholar]

- Frey William H. Immigration and Internal Migration ‘Flight’ from U.S. Metropolitan Areas: Toward a New Demographic Balkanization. Urban Studies. 1995;32:733–57. [Google Scholar]

- Frey William H. State of Metropolitan America Series, Metropolitan Policy Program. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution; 2011a. Melting Pot Cities and Suburbs: Racial and Ethnic Change in Metro America in the 2000s. [Google Scholar]

- Frey William H. State of Metropolitan America Series, Metropolitan Policy Program. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution; 2011b. The New Metro Minority Map: Regional Shifts in Hispanics, Asians, and Blacks from Census 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Frey William H. Diversity Explosion: How New Racial Demographics Are Remaking America. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman Samantha. Do Declines in Residential Segregation Mean Stable Neighborhood Racial Integration in Metropolitan America? Social Science Research. 2008;37:920–33. [Google Scholar]

- Gieryn Thomas. A Space for Place in Sociology. Annual Review of Sociology. 2000;26:463–96. [Google Scholar]

- Holloway Steven R, Wright Richard, Ellis Mark. The Racially Fragmented City? Neighborhood Racial Segregation and Diversity Jointly Considered. Professional Geographer. 2012;64:63–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hou Feng, Zheng Wu. Racial Diversity, Minority Concentration, and Trust in Canadian Neighborhoods. Social Science Research. 2009;38:693–716. doi: 10.1016/j.ssresearch.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Humes Karen K, Jones Nicholas A, Ramirez Roberto R. 2010 Census Brief, C2010BR-02. Washington, DC: US Census Bureau; 2011. Overview of Race and Hispanic Origin: 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Iceland John. Where We Live Now: Immigration and Race in the United States. Berkeley: University of California Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Kenneth M. Carsey Research National Fact Sheet #29. University of New Hampshire; 2015. (June) Diversity Growing Because Births Far Exceed Deaths Among Minorities, But Not Among Whites. http://scholars.unh.edu/carsey/244/ [Google Scholar]

- Johnson Kenneth M, Lichter Daniel T. Growing Diversity among America’s Children and Youth: Spatial and Temporal Dimensions. Population and Development Review. 2010;36:151–76. [Google Scholar]

- Krysan Maria, Cooper Mick P, Reynolds Farley, Tyrone Forman. Does Race Matter in Neighborhood Preferences? Results from a Video Experiment. American Journal of Sociology. 2009;115:527–59. doi: 10.1086/599248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laurence James. Reconciling the Contact and Threat Hypotheses: Does Ethnic Diversity Strengthen or Weaken Community Inter-Ethnic Relations? Ethnic and Racial Studies. 2014;37:1328–49. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Barrett A, Firebaugh Glenn, Iceland John, Matthews Stephen A., editors. Residential Inequality in American Neighborhoods and Communities. Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science. 2015;660:1–366. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Barrett A, Hughes Lauren A. Bucking the Trend: Is Ethnoracial Diversity Declining in American Communities? Population Research and Policy Review. 2015;34:113–39. doi: 10.1007/s11113-014-9343-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Barrett A, Iceland John, Farrell Chad R. Is Ethnoracial Integration on the Rise? Evidence from Metropolitan and Micropolitan America Since 1980. In: Logan John R., editor. Diversity and Disparities: America Enters a New Century. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2014. pp. 415–56. [Google Scholar]

- Lee Barrett A, Iceland John, Sharp Gregory. Racial and Ethnic Diversity Goes Local: Charting Change in American Communities over Three Decades. US2010 Project. 2012 Sep; www.s4.brown.edu/us2010/Data/Report/report08292012.pdf.

- Lee Barrett A, Wood Peter B. Is Neighborhood Racial Succession Place-Specific? Demography. 1991;28:21–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Jennifer, Bean Frank D. The Diversity Paradox: Immigration and the Color Line in Twenty-First Century America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Li Wei. Ethnoburb: The New Ethnic Community in Urban America. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Lichter Daniel T. Integration or Fragmentation? Racial Diversity and the American Future. Demography. 2013;50:359–91. doi: 10.1007/s13524-013-0197-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lichter Daniel T, Parisi Domenico, Grice Steven M, Taquino Michael C. Municipal Underbounding: Annexation and Racial Exclusion in Small Southern Towns. Rural Sociology. 2007;72:47–68. [Google Scholar]

- Lieberson Stanley, Waters Mary C. From Many Strands: Ethnic and Racial Groups in Contemporary America. New York: Russell Sage Foundation; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay James M, Singer Audrey. Changing Faces: Immigrants and Diversity in the Twenty-First Century. In: Aaron Henry J, Lindsay James N, Nivola Pietro S., editors. Agenda for the Nation. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press; 2003. pp. 217–60. [Google Scholar]