Abstract

Objective: To determine the relationship between medical and mental health comorbidities in a large cohort of veterans with spinal cord injury (SCI). Methods: Data were collected from interviews and electronic medical records of veterans with SCI (N = 1,047) who received care at 7 geographically diverse SCI centers within the Department of Veterans Affairs across the country (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01141647). Employment, medical, functional, and psychosocial data underwent cross-sectional analysis. Results: Lack of any documented mental health diagnosis correlated strongly with being employed at the time of enrollment. No single comorbidity was associated with employment at enrollment, but an increased number of medical and/or mental health comorbidities (“health burden”) were associated with a decreased likelihood of employment at the time of enrollment. Conclusion: Further investigation is needed to clarify whether comorbidity severity or combinations of specific comorbidities predict rehabilitation outcome, including employment.

Keywords: comorbidity, employment, mental health, outcomes, rehabilitation, spinal cord injury, supported employment, vocational rehabilitation, veterans

Spinal cord injury (SCI), which affected approximately 276,000 persons in the United States in August 2014,1 is less common than some other neurologic conditions such as cerebrovascular accident. However, SCI has a disproportionately large economic impact because most persons with SCI are of working age at the time of their injuries. In addition, the sequelae of SCI are numerous, co-occurring, life-altering, and life-long, including paralysis, pressure ulcers, neurogenic bowel and bladder, spasticity, neurogenic pain, and other problems. Nevertheless, most persons with SCI want to work, and many judge themselves capable of work.2,3 Further, research has demonstrated that being employed is strongly associated with better health status.4 Despite the willingness of persons with SCI to work and the substantial benefits of work, the employment rate in this population is very low.5

Factors related to employment after SCI have been reviewed in detail.5 Epidemiologic research has demonstrated a number of predictors of employment status after SCI, including race,6,7 educational level,8 and other demographic and psychosocial variables.5 The data on the effects of medical factors, however, specifically among veterans with SCI, are limited. Factors previously identified are co-occurring health problems, frequent hospitalizations,9,10 and pain.11 A retrospective evaluation of the influence of secondary conditions on job acquisition and retention in a civilian cohort with SCI found hospitalization and some conditions, including pneumonia, urinary calculi, greater severity of depression and pain and pain interference, and more severe pressure ulcers, decreased the likelihood of job acquisition.7 In one survey of male veterans with SCI, being “unable to hold a job because long hours in a chair cause ulcers”(p367) was most frequently reported as the reason for unemployment.12 In a more recent, though small, survey, medical problems were cited as the major barrier to achieving employment.13

There are little available data, however, to provide details on the relationship between SCI-related comorbidities and employment status, specifically among veterans with SCI. Military service, for example, increases the likelihood of mental health challenges such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Military service requires a high school diploma or a GED but few veterans with SCI have advanced degrees.14 Compared to counterparts in the SCI Model Systems, veterans have a higher average age, lower socioeconomic status, and more comorbid medical conditions; hence, they comprise a unique study population.

Since “medical problems are potentially modifiable factors that may become targets for interventions to improve outcomes,”7(p425) we used medical and employment data from a large cohort of veterans with SCI to determine the extent of comorbidities and assess their relationship to employment. Comorbidities of interest to the present study included SCI-specific sequela such neurogenic bowel and bladder, spasticity, pressure ulcers, and urinary tract infections, as well as general medical comorbidities such as cardiopulmonary disease. Broadly, our research question was, “What is the relationship of comorbid conditions and probability of employment?” We hypothesized that an increased number of comorbidities would be associated with lack of employment post SCI. In our cohort, an individual's SCI could have occurred during military service or, more commonly, following military discharge.

Methods

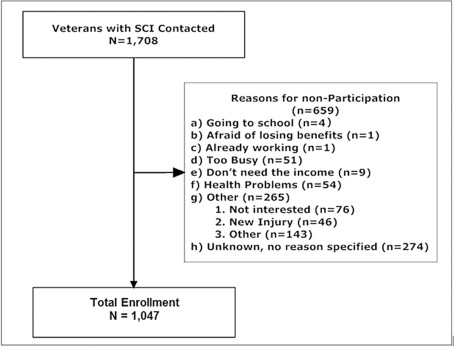

PrOMOTE (Predictive Outcome Model Over Time for Employment), a prospective, multisite study conducted from August 2010 through March 2015, evaluated longitudinal employment, quality of life, and economic outcomes of a large cohort of veterans with SCI receiving medical and rehabilitation care at geographically diverse SCI centers in the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01141647) (Figure 1).15,16 All veterans who met inclusion criteria were invited to participate in an in-person baseline interview to provide information on employment, health, and quality of life. Inclusion criteria included age between 18 and 70 years, medically and neurologically stable, enrolled in VHA care, and having an SCI caused by trauma, compression, infection, or localized inflammatory processes. Veterans with multiple sclerosis, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or other neurodegenerative disorders were excluded. Veterans were then invited to participate in a follow-up phone interview that collected more detailed information on employment after SCI.

Figure 1.

CONSORT flow diagram showing recruitment of veterans with spinal cord injury (SCI) to participate in a study of employment after SCI.

Employment history was recorded as whether or not the veteran had worked during 3 overlapping time periods: any time following their SCI (EMP-PostSCI), active competitive employment at the time of enrollment (EMP-enroll), or during the 5 years before enrollment (EMP-5yr), the latter not being coded for veterans who sustained SCI within 5 years of enrollment. As all participants were veterans, all had participated in the labor force in the form of military service and possibly had other employment before the SCI.

Medical and mental health comorbidities were extracted from electronic medical records and recorded as present or absent at the time of the record review. To aid data capture, study coordinators were provided a form listing 36 common medical conditions and 5 common mental health conditions; there was also space on the form to record “other” conditions or “no conditions.” The listed conditions were derived from electronic medical record problem lists, inpatient or outpatient annual evaluations, history and physicals, and/or discharge summaries. Medical comorbidities were recorded if a current or lifetime diagnosis was listed, and mental health comorbidities were only recorded if a current or lifetime diagnosis was listed such as dementia, depression, substance abuse dependence, bipolar disorder, or schizophrenia.

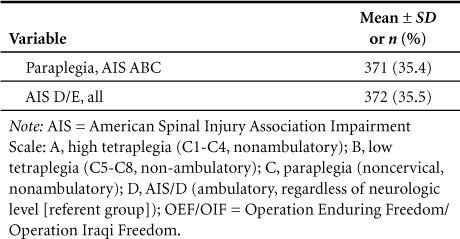

Data are presented as means ± standard deviation (SD) or frequencies and percents, where appropriate. Statistical significance was assessed using chi-square or Student's t test, where appropriate. For employment at time of enrollment (EMP-enroll/Yes), we modeled the association of number of health comorbidities using unconditional logistic regression. We chose this category of employment as we did not solicit information regarding the timing of the comorbidities, either medical or mental. Therefore we had no idea as to the temporal relationship between EMP-postSCI and EMP-5yr. Covariates included in the models to control for potential confounding effects were age, race (Caucasian vs other), years of education, time since injury, employment at time of injury, and level of injury (“injury severity”). Injury severity was recorded as a combination of neurologic level and completeness using the International Standards for Neurological Classification of SCI (ISNCSCI) and American Spinal Injury Assocation Impairment Scale (AIS) as follows: AIS ABC, high tetraplegia (C1–C4); AIS ABC, low tetraplegia (C5–C8); AIS ABC, paraplegia (noncervical); and AIS D/E (regardless of neurologic level) [referent group].1,5,14,17 For all logistic regression models, we modeled the probability of EMP-enroll/Yes. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals are provided. Statistical significance was considered for p < .05, 2-tailed. All analyses were conducted using SAS (version. 9.4; SAS, Inc., Cary, NC).

Results

Participants (N = 1,047) were of average age 53.3 ± 10.0 years, predominantly male (95.7%), and Caucasian (62.3%); slightly over a third were married at the time of study enrollment (35.6%); education level was mainly high school (13.8 ± 2.4 years), fewer than 20% had a bachelor or graduate degree; and fewer than 10% served in Operations Enduring Freedom/Iraqi Freedom (OEF/OIF) (Table 1). Thirty-two percent of participants were service-connected for SCI. The most frequent cause of SCI was vehicular accident (34.8%) or other/unknown (32.2%) (Table 1), the latter was primarily medical or surgical complication (n = 85; 8.1%) or arthritis/spinal stenosis (n = 44; 4.2%).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics for veterans with spinal cord injury (N = 1,047)

For EMP-postSCI, 840 participants responded, and 752 responded for EMP-5yr. The majority of participants (72.1%; n = 606) were employed at the time SCI occurred. Veterans reported they were employed as follows: EMP-postSCI/Yes, 29.8% (n = 251/840), EMP-5yr/Yes, 28.1% (n = 211/753), and EMP-enroll/Yes, 9.3% (n = 97/1,047). Employment was reported for all 3 periods by 5% (55/1,047), whereas 32.5% (n = 340/1,047) reported no employment at all.

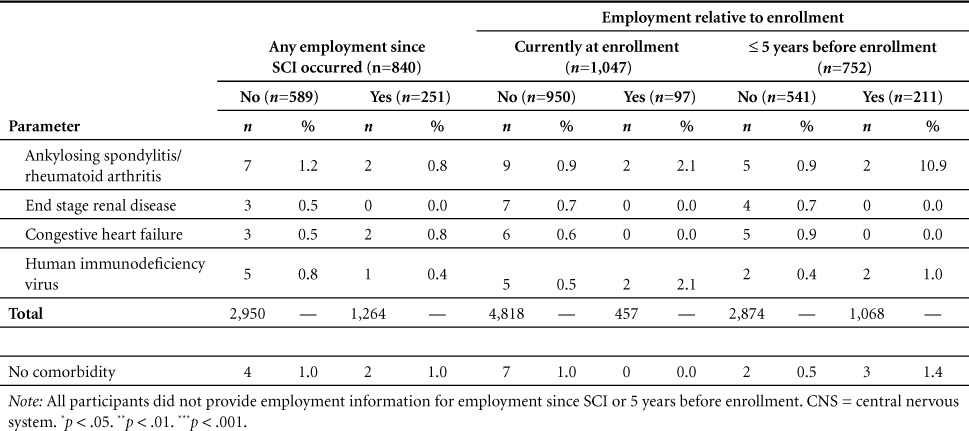

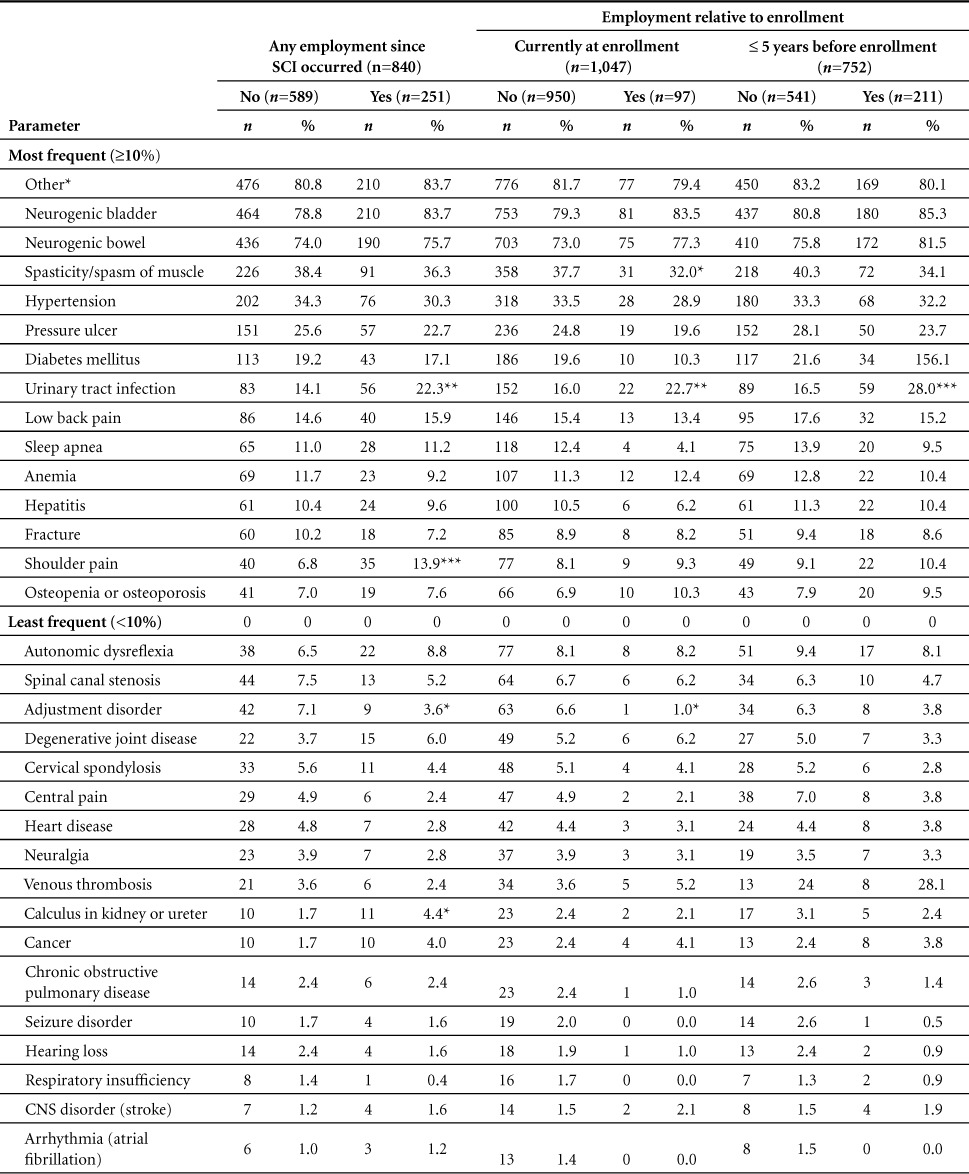

For all 3 groups, the most common of the 37 reported medical comorbidities were, in decreasing order, other medical, neurogenic bladder, neurogenic bowel, spasticity, hypertension, pressure ulcer, and diabetes (Table 2). For all groups, when the numbers of medical comorbidities for each group were compared between those who did and did not report employment, those who reported employment had substantially fewer comorbidities, especially for the EMP-enroll group (Table 2).

Table 2.

Medical comorbidities in veterans with spinal cord injury (SCI) by employment history (N = 1,047) (CONT.)

Table 2.

Medical comorbidities in veterans with spinal cord injury (SCI) by employment history (N = 1,047)

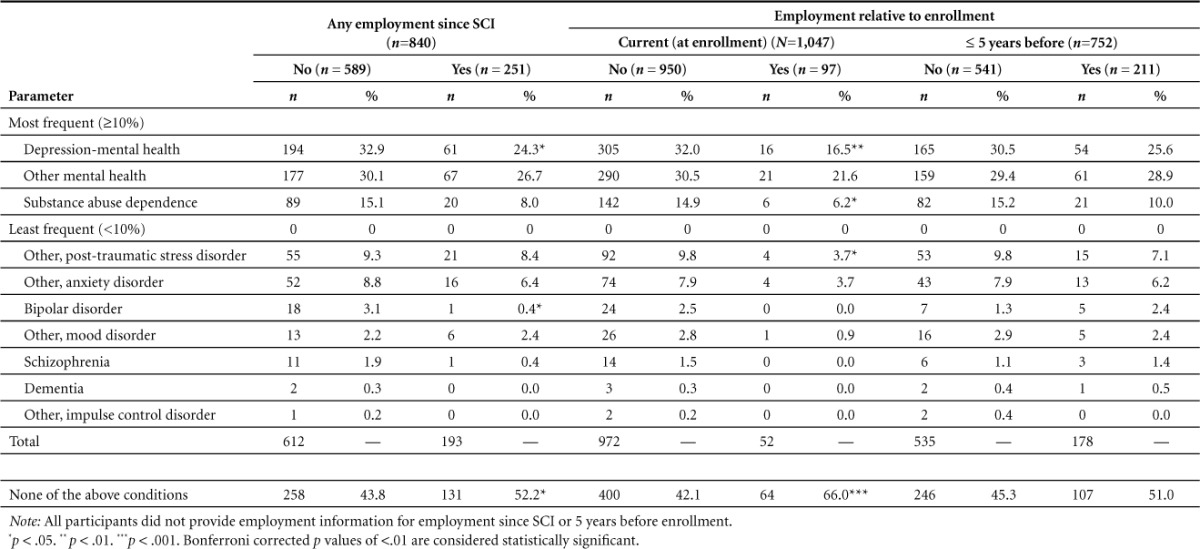

Of the 10 reported possible mental health comorbidities, the most common were depression, other, and substance abuse, but PTSD was close to 10% for all groups except EMP-enroll/Yes, with only 3.7% of those veterans reporting PTSD (Table 3). Further, for both EMP-post SCI and EMP-enroll, depression was reported significantly less often for those who reported employment than those who did not (Table 3). The percentage with no mental health disorders among all three groups ranged from 42% to 52% (Table 3).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics for veterans with spinal cord injury (N = 1,047)

Table 3.

Mental health comorbidities in veterans with spinal cord injury (SCI) by employment history

Stratified by EMP-post SCI/Yes, statistically significant differences were observed for percent having shoulder pain (p < .001) and urinary tract infection (p < .003) (Table 2). Stratified by EMP-5yr/Yes, there was only a statistically significant difference in employment for urinary tract infection (p < .001). For mental health comorbidities, with stratification by EMP-post SCI/Yes, a statistically significant difference was only observed for depression and bipolar disorder (p < .012) (Table 3). Stratified by EMP-enroll/Yes, statistically significant differences were observed for percent having depression (p < .002), substance abuse dependence (p < .018), and none of the above conditions (p < .001) (Table 3). No significant differences were observed for EMP-5yr/Yes.

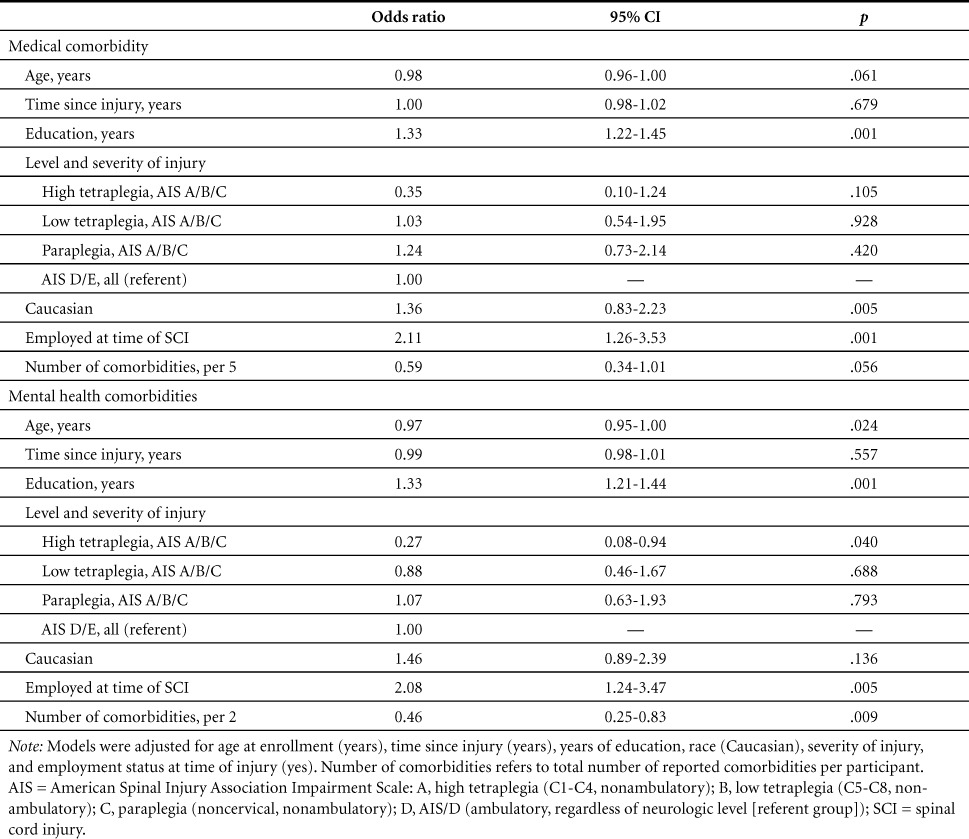

Following adjustment for covariates, the number of medical comorbidities approached statistical significance for current employment (p < .056) (Table 4). Years of education (p < .001), Caucasian race (p < .005), and employment at time of SCI (p < .001) were significant predictors of EMP-enroll/Yes (Table 4). For mental health, after adjustment for covariates, the number of mental health comorbidities was a significant predictor of EMP-enroll/Yes, which correlated most strongly with a lack of any known mental health diagnosis (Table 4). Age (p < .024), years of education (p < .001), high tetraplegia (p < .040), and employment at time of injury (p < .005) were also strong predictors of EMP-enroll/Yes.

Table 4.

Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals of employment at time of enrollment for medical and mental health comorbidities stratified by number of comorbidities and severity of injury after adjustment for covariates (N = 1,047)

After adjustment for medical comorbidities, every 5-unit increase in the number of medical comorbidities decreased the estimated probability of EMP-enroll/Yes by 41% (OR, 0.59; 95% CI, 0.034–1.01). Similarly, a 2-unit increase in number of mental health comorbidities subsequently decreased the estimated probability of EMP-enroll/Yes by 54% (OR, 0.046; 95% CI, 0.25–0.83).

Discussion

Our data demonstrate a decreasing likelihood of employment with an increasing number of comorbidities (“health burden”). The combined incidence (72.5%) of neurogenic bowel and bladder among the cohort was quite high, which likely decreased the utility of these diagnoses as predictors. The occurrence rate of diagnoses reported may be limited by how frequently a diagnosis has been reported in the medical record or recognized and reported as a medical problem by the veteran. For example, osteopenia/osteoporosis might be underreported due to not having been specifically tested for, listed in the medical record, or recalled by the patient.

The strong relationship of mental health comorbidities to unemployment is a key finding and consistent with a previous report that barriers to employment after traumatic spine fracture were more commonly psychological than physical.11 After SCI, depression is common,17,18 and unemployment is associated with increased symptoms of depression.19 Among veterans, PTSD is also a well-recognized mental health problem. Mental health problems, however, cannot be viewed in a vacuum and likely relate to specific physical problems in complex ways over time.

One might expect that a serious SCI-related complication such as a pressure ulcer would predict lack of current or past employment status. Some persons, however, may have had a single pressure ulcer but not have current or ongoing problems with pressure ulcers, which reflects variability in severity of the problem within the group of persons with a pressure ulcer diagnosis. Since our data did not distinguish current versus lifetime diagnoses from electronic medical records, no temporality could be established. The association of shoulder pain with EMP-postSCI/Yes is not clear but could represent a physically active subgroup.

The current study represents an exploratory analysis of data from a large sample of veterans with SCI. Additional data obtained from clinic visits, including diagnostic codes associated with medical comorbidities, will be helpful to further clarify health burden. The frequency, number, and severity of comorbidities may vary widely among persons with SCI. Some persons may continue to work despite severe medical issues. Specific advances in medical, mental health, or rehabilitation care for SCI could be measured by any improvement in employment. A long-term prospective study examining the occurrence of medical complications and their impact on employment would be useful. For example, what percentage of employed persons with SCI return to work after the first, second, third (and so on) occurrence of stage 3 or 4 pressure ulcers? The notable lack of association of other important health factors with employment may reflect a similar need to measure health burden of individual comorbidities over time and to include specific symptoms (eg, bowel or bladder incontinence). There is clearly a need for future research in this area.

Participant age eligibility was 18 to 70 years, but following recruitment only 4 participants were age 68 to 69 and 93 participants were older than 64 years (8.9%). Participants for the PrOMOTE study were recruited between the ages of 18 and 64 years. Veterans who had previously participated in the first RCT (SCI-VIP) were also eligible to enroll in the PrOMOTE study to allow us to collect longitudinal data and receive treatment. Some of these veterans gained and continued employment. We elected to keep them in the sample for the present analysis as they are representative of veterans who receive care in the VHA, although this falls outside the norm for most vocational research. This could have altered our results slightly.

We also included veterans with all AIS levels in our research for similar reasons both in terms of collecting baseline interviews and in having the opportunity to participate in employment interventions. Like the older age of our veterans, this reflects the characteristics of some veterans followed at our centers. Although persons with AIS E status may have recovered to normal strength and sensation as measured by the ISNCSCI exam, the ISNCSCI manuals have noted that these persons can still have other issues including spasticity/hyperreflexia. In addition, these persons frequently have other residual issues such as pain and impairments in proprioception or balance, which can impact function. The latter is quite common and can place persons at risk for falls. This needs to be considered in terms of work restrictions and employment pursuits.

There are some limitations to the generalizability of the sample to non-veterans. Another limitation is that the data reported here do not provide information on the chronology of comorbidities. The focus of the present article was limited to analysis of medical and mental health comorbidities. Medical and mental health comorbidities were aggregated into groups of 5 (medical) and 2 (mental) for modeling to facilitate clinical comparison. Other populations may find these categories either too broad or too narrow. We recognize that it is not merely a diagnosis (eg, neurogenic bladder) but the resulting complications (incontinence, infections, etc) that cause difficulties. Generally disease processes, rather than symptoms, become part of a medical record problem list. Other constructs, such as social connectedness, may also influence employment as a social determinant of health. Previously published data on the effect of social support in the home on employment outcomes have demonstrated the negative effects that poor social participation has on employment.16,20 In addition, we focused on mental health and medical comorbidities in this analysis, which dealt with only a portion of our data set, so we did not control for work disincentives in this analysis. Finally, given the large number of statistical comparisons, some significant comparisons may be due to type I error.

Conclusion

Mental health diagnoses were associated with decreased likelihood of employment in a large cohort of veterans with SCI. Health burden due to multiple medical and mental health comorbidities also was associated with decreased likelihood of employment. These findings emphasize the importance of maximizing management of medical and mental health comorbidities. Given the complex interplay between medical problems, mental health, and employment, integrating vocational and clinical services may provide the best opportunity to address these barriers and to promote better health as well as employment outcomes after SCI.

Acknowledgments

This material is based on work supported by the Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development, Rehabilitation Research and Development Service, Project #O7824R. It was presented in part at the 2015 Educational Conference and Expo, Academy of Spinal Cord Injury Professionals, New Orleans, Louisiana, September 8, 2015.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1. National Spinal Cord Injury Statistical Center. . Spinal cord injury facts and figures at a glance. J Spinal Cord Med. 2014; 37 5: 659– 660. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Tomassen PC, Post MW, van Asbeck FW.. Return to work after spinal cord injury. Spinal Cord. 2000; 38 1: 51– 55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Young AE, Murphy GC.. A social psychology approach to measuring vocational rehabilitation intervention effectiveness. J Occup Rehabil. 2002; 12 3: 175– 189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Krause JS, Saunders LL, Acuna J.. Gainful employment and risk of mortality after spinal cord injury: Effects beyond that of demographic, injury and socioeconomic factors. Spinal Cord. 2012; 50 10: 784– 788. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ottomanelli L, Lind L.. Review of critical factors related to employment after spinal cord injury: Implications for research and vocational services. J Spinal Cord Med. 2009; 32 5: 503– 531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Krause JS, Anson CA.. Employment after spinal cord injury: relation to selected participant characteristics. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1996; 77 8: 737– 743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Meade MA, Forchheimer MB, Krause JS, Charlifue S.. The influence of secondary conditions on job acquisition and retention in adults with spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011; 92 3: 425– 432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Krause JS, Terza JV, Dismuke CE.. Factors associated with labor force participation after spinal cord injury. J Vocat Rehabil. 2010; 33 2: 89– 99. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Anderson D, Dummont S, Azzaria L, Bourdais ML, Noreau L.. Determinants of return to work among spinal cord injury patients: A literature review. J Vocat Rehabil. 2007; 27 1: 57– 68. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Boschen KA, Tonack M, Gargaro J.. Long-term adjustment and community reintegration following spinal cord injury. Int J Rehabil Res Int Z Für Rehabil Rev Int Rech Réadapt. 2003; 26 3: 157– 164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Burnham RS, Warren SA, Saboe LA, Davis LA, Russell GG, Reid DC.. Factors predicting employment 1 year after traumatic spine fracture. Spine. 1996; 21 9: 1066– 1071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. El Ghatit AZ. Variables associated with obtaining and sustaining employment among spinal cord injured males: A follow-up of 760 veterans. J Chronic Dis. 1978; 31 5: 363– 369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ottomanelli L, Bradshaw LD, Cipher D.. Employment and vocational rehabilitation service use among veterans with spinal cord injury. J Vocat Rehabil. 2009; 31 1: 39– 43. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ottomanelli L, Goetz LL, Suris A, . et al. Effectiveness of supported employment for veterans with spinal cord injuries: Results from a randomized multisite study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012; 93 5: 740– 747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Cotner B, Njoh E, Trainor J, O'Connor D, Barnett S, Ottomanelli L.. Facilitators and barriers to employment among veterans with spinal cord injury receiving 12 months of evidence-based supported employment services. Top Spinal Cord Inj Rehabil. 2015; 21 1: 20– 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sutton BS, Ottomanelli L, Njoh E, Barnett SD, Goetz LL.. The impact of social support at home on health-related quality of life among Veterans with spinal cord injury participating in a supported employment program. Qual Life Res. 2015; 24: 1741– 1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Hoffman JM, Bombardier CH, Graves DE, Kalpakjian CZ, Krause JS.. A longitudinal study of depression from 1 to 5 years after spinal cord injury. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011; 92 3: 411– 418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine. Depression Following Spinal Cord Injury: A Clinical Practice Guideline for Primary Care Physicians. Washington DC: Paralyzed Veterans of America; 1998. http://www.pva.org/site/c.ajIRK9NJLcJ2E/b.6305831/k.4943/Clinical_Practice_Guidelines__Consumer_Guides.htm. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bombardier CH, Fann JR, Tate DG, . et al. An exploration of modifiable risk factors for depression after spinal cord injury: Which factors should we target? Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2012; 93 5: 775– 781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Craig A, Nicholson Perry K, Guest R, Tran Y, Middleton J.. Adjustment following chronic spinal cord injury: Determining factors that contribute to social participation. Br J Health Psychol. 2015; 20 4: 807– 823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]