Phthalates are widely used in the manufacturing of consumer and medical products. In the present study, di-2-ethylhexyl-phthalate exposure was associated with alterations in heart rate variability and cardiovascular reactivity. This highlights the importance of investigating the impact of phthalates on health and identifying suitable alternatives for medical device manufacturing.

Keywords: phthalate, endocrine disruptor, heart rate variability, cardiovascular reactivity, autonomic

Abstract

Plastics have revolutionized medical device technology, transformed hematological care, and facilitated modern cardiology procedures. Despite these advances, studies have shown that phthalate chemicals migrate out of plastic products and that these chemicals are bioactive. Recent epidemiological and research studies have suggested that phthalate exposure adversely affects cardiovascular function. Our objective was to assess the safety and biocompatibility of phthalate chemicals and resolve the impact on cardiovascular and autonomic physiology. Adult mice were implanted with radiofrequency transmitters to monitor heart rate variability, blood pressure, and autonomic regulation in response to di-2-ethylhexyl-phthalate (DEHP) exposure. DEHP-treated animals displayed a decrease in heart rate variability (−17% SD of normal beat-to-beat intervals and −36% high-frequency power) and an exaggerated mean arterial pressure response to ganglionic blockade (31.5% via chlorisondamine). In response to a conditioned stressor, DEHP-treated animals displayed enhanced cardiovascular reactivity (−56% SD major axis Poincarè plot) and prolonged blood pressure recovery. Alterations in cardiac gene expression of endothelin-1, angiotensin-converting enzyme, and nitric oxide synthase may partly explain these cardiovascular alterations. This is the first study to show an association between phthalate chemicals that are used in medical devices with alterations in autonomic regulation, heart rate variability, and cardiovascular reactivity. Because changes in autonomic balance often precede clinical manifestations of hypertension, atherosclerosis, and conduction abnormalities, future studies are warranted to assess the downstream impact of plastic chemical exposure on end-organ function in sensitive patient populations. This study also highlights the importance of adopting safer biomaterials, chemicals, and/or surface coatings for use in medical devices.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Phthalates are widely used in the manufacturing of consumer and medical products. In the present study, di-2-ethylhexyl-phthalate exposure was associated with alterations in heart rate variability and cardiovascular reactivity. This highlights the importance of investigating the impact of phthalates on health and identifying suitable alternatives for medical device manufacturing.

the development of plasticized polyvinyl chloride (PVC) materials has promoted versatility in medical device manufacturing, which has transformed hematological care, transfusion medicine, and cardiac surgery. Di-2-ethylhexyl-phthalate (DEHP) is a commonly used plasticizer that imparts flexibility to PVC medical devices (24). Plasticized PVC products allow for the use of individual sterile storage containers and tubing, which has reduced the risk of infection, improved stability, and increased shelf life. DEHP-containing blood storage bags are also associated with a reduced incidence of red blood cell hemolysis. The latter has been attributed to DEHP chemical migration out of the plastic material and into the stored blood and stabilization of red blood cell membranes (2).

Since plasticizers are not covalently bound to the PVC polymer, they are highly susceptible to leaching when in contact with lipophilic solutions (i.e., blood, nutrition solutions, and medication formulation aids) (47, 68). Consequently, patients can be exposed to high phthalate doses, particularly when undergoing multiple medical interventions that use plasticized PVC products (i.e., storage bags containing blood, plasma, intravenous fluids, total parenteral nutrition, tubing associated with their administration, nasogastric tubes, enteral feeding tubes, catheters, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation circuits, hemodialysis tubing, respiratory masks, and endotracheal tubes) (34, 35, 39, 48, 62, 67). Moreover, pediatric patients <1 yr old can be subjected to prolonged phthalate exposure due to an underdeveloped glucuronidation pathway and slowed excretion. As a result, patient exposure can exceed safe levels by 4,000–160,000 times (13, 17, 49).

Emerging epidemiological studies have shown correlations between phthalate exposure and human health concerns, including neurological disorders and cardiovascular disease (14, 22, 32, 58, 76, 78). The latter includes an association between phthalate plasticizer exposure and increased systolic blood pressure (SBP) in adolescents (83, 84) and an increased coronary risk in elderly populations (46, 60). Additionally, our laboratory has previously shown that phthalate exposure adversely affects the electrical activity and contractility of cardiac muscle cells (30, 64–66). To further address the potential clinical impact of phthalates on health, we used an in vivo radiotelemetry system in mice to monitor the direct effect of phthalates on cardiovascular [blood pressure (BP) and heart rate (HR)] and autonomic physiology [HR variability (HRV)]. Modifications in HRV indexes serve as an early and sensitive indicator of cardiovascular dysfunction, which is manifested by a decrease in parasympathetic (16, 31) and/or increase in sympathetic tone (50). A reduction in HRV often precedes the development of hypertension (73), atherosclerosis (72), and conduction abnormalities. HRV markers have also been associated with the Framingham risk score (92), coronary events (20), and dysrhythmia (86). In the present study, animals were monitored under both resting conditions and during and after Pavlovian fear conditioning, which provokes a sympathetically mediated cardiovascular response (19, 44, 77, 85). We hypothesized that phthalate exposure alters autonomic regulation of the cardiovascular system, which is evidenced by a decrease in basal HRV and exaggerated cardiovascular reactivity to a conditioned stressor.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animal protocol and experimental design.

All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the George Washington University and Children’s National Health System. Male 12-wk-old C57BL/6 mice were purchased from Hilltop Laboratory Animals. Mice were housed individually in ventilated acrylic cages with nesting material. Animals were fed a normal laboratory diet ad libitum. Room lights were cycled every 12 h: on from 0700 to 1900 hours and off from 1900 to 0700 hours. Baseline data were recorded for 2–3 days, and animals were then separated into two groups differing in drinking water supplementation: 1) Captisol (4 mg/ml) for vehicle control or 2) DEHP-Captisol (1 µg-4 mg/ml). The DEHP dose was chosen to fall within the range of clinical exposure for a pediatric patient undergoing medical treatment over an extended period of time (13, 32, 49). Open-field testing was performed using the Tru Scan system to assess locomotion.

Telemetry transmitters (n = 12, HDX-11, Data Sciences) were implanted surgically under aseptic conditions with the blood pressure transducer placed in the left carotid artery and fed inferiorly. Electrodes were placed on the right atrium and apex to produce a lead II ECG. Animals were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine via intraperitoneal injection; depth of anesthesia was assessed frequently via toe pinch. Body temperature was regulated using a feedback-controlled heating pad. Mice recovered from surgery for 7–10 days before baseline data collection was started. Cardiovascular reactivity testing to fear conditioning was performed after 4-wk exposure. HR and BP recordings were collected for continuous segments for 3–4 days/wk to conserve transmitter battery power for the total 6-wk experimental protocol. At the end of the study, animals were anesthetized with ketamine-xylazine and then euthanized by exsanguination after heart excision.

Telemetry data acquisition and analysis of HRV.

Telemetry data, including ECG lead II, arterial BP, activity, and temperature, were acquired using DataQuest ART (Data Sciences) and analyzed using ecgAUTO (Emka Technologies). From the BP waveform, the following parameters were determined: diastolic, systolic, mean, and dP/dt. R waves were detected from the ECG to determine the mean RR interval and HR. Each hour, HR and BP signals were sampled and analyzed [120-s continuous segment (80)], resulting in 12 data points per daytime (12 h) and nighttime (12 h). Daytime and nighttime data were averaged across the 12-h timeframe and displayed with two representative data points per week of the 6-wk study, similar to other analysis methods for long-term telemetry recordings (58, 80).

For HRV analysis, an interbeat-interval waveform was calculated for 500 continuous normal beats (~30–60 s of recording), as previously described (8, 10). The interbeat-interval waveform was further processed by cubic spline interpolation and then through fast Fourier transform to determine high-frequency (HF) power between 2.5 and 5 Hz, a suggested bandwidth that is predominantly parasympathetic activity for mouse HRV analysis (6). HF power was normalized by dividing the squared mean RR interval (in s) at that input epoch, a common transform to compensate for the nonlinear relationship between HR and RR (8, 69). Low-power and low-frequency-to-HF ratio were not investigated due to concerns of accuracy (9, 51, 57), particularly for long-term in vivo studies. The SD of normal beat-to-beat intervals (SDNN) was calculated based on guidelines for the measurement of overall HRV (33). Similarly to HF power, SDNN was normalized by dividing by the mean RR interval (in s) of the input epoch (8, 69).

Conditioned cardiovascular and autonomic reactivity to Pavlovian fear conditioning.

Enhanced sympathetic nerve activity is involved in the development and progression of hypertension (37, 43). Indeed, spontaneously hypertensive animals display exaggerated cardiovascular reactivity and prolonged BP elevation (44) in response to fear conditioning due to heightened sympathetic neural activity (37). Therefore, we used a similar Pavlovian fear conditioning paradigm (53) to provoke a conditioned cardiovascular response that is sympathetically mediated (23, 37, 41, 71). Cue-dependent fear conditioning consists of pairing a conditioned stimulus (CS; audible tone) and an unconditioned stimulus (US; mild foot shock) over five consecutive trials. After repeated CS-US pairings, an association is formed such that the CS alone elicits the same behavioral and autonomic responses (conditioned responses) formerly produced by the US (44). After fear conditioning (>22 h), cardiovascular reactivity to the conditioned cue was evaluated in a novel test chamber. For this study, we focused on the cardiovascular components (HR, HRV, and BP), which are mediated by the autonomic nervous system (14, 19, 44, 59, 77).

After 4 wk of exposure, mice underwent auditory fear conditioning (30 min, Coulbourn Instruments). This included five pairings of the CS (audible tone: 30 s, 6 kHz, 75 db) coterminating with an US (mild foot shock: 500 ms, 0.6 mA) (53). Poincaré plots of RR intervals were produced for each animal after the first tone shock pair as a measure of HRV during a provoked sympathetic response. Poincaré plots were averaged by treatment group (control vs. DEHP treated) to produce ensemble means, from which RR variability was quantitated by the SD from the major (SD1) and minor axis (SD2) (38). After the fear conditioning protocol, continuous BP and ECG measurements were collected for ~22 h in the homecage environment (recovery). The next day, cardiovascular reactivity to the CS (tone) was performed in the absence of the US (shock). BP and ECG were continuously monitored. After cardiovascular reactivity testing, animals were returned to their homecage to continuously monitor BP and ECG over 22 h (recovery).

Ganglionic blockade via chlorisondamine administration.

To measure the contribution of the sympathetic nervous system on the cardiovascular system, animals were treated with the ganglionic blocker chlorisondamine (12 mg/kg ip) (7, 29, 88, 91). Blockage of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the autonomic ganglia attenuates sympathetic input to arteries, resulting in vasodilation and a decrease in BP (18). After animals underwent treatment with control or DEHP-supplemented water (6 wk, end of study), chlorisondamine was administered and the magnitude of sympathetic input was determined by the fall in mean arterial pressure (MAP) after ganglionic blockade.

Mass spectrometry to quantitate plasma phthalate concentration.

At the end of the treatment study (6 wk), blood samples were collected via cardiac puncture and anticoagulated. Plasma samples were isolated and then analyzed at the Bioanalytical Laboratory at the School of Pharmacy, Virginia Commonwealth University. Samples were subjected to a high-throughput solid phase extraction and analyzed using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry/mass spectrometry, as previously described (79). Briefly, samples were subjected to reversed phase chromatography using isocratic conditions (85% acetonitrile and 15% of 0.05% acetic acid). An Xterra 2.1 × 100-mm, 3.5 μM HPLC column (Waters, Milford, MA) was used. Concentrations of DEHP and its primary metabolite mono-2-ethylhexylphthalate (MEHP) were quantitated. Replicate analyses of spiked samples containing multiple concentrations of the target molecules were used to generate a calibration curve (DEHP: r2 = 0.992644 and MEHP: r2 = 0.998872).

Gene expression analysis of cardiac tissue.

At the end of the treatment study (6 wk), total RNA was isolated from heart tissue using an RNeasy fibrous tissue kit (Qiagen, Germantown MD) per the manufacturer’s instructions. RNA concentration and quality were assessed via 260:280-nm absorbance readings, and total RNA was reverse transcribed using a SuperScript VILO cDNA synthesis kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The resulting cDNA was used as a template for real-time quantitative PCR (qPCR) using Taqman Gene Expression assays (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) for GAPDH, angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), ACE2, angiotensin II type 1 receptor, α1A-adrenergic receptor, β2-adrenergic receptor, endothelin-1, endothelin receptor-α, endothelin receptor-β, and nitric oxide synthase 3 (NOS3). qPCR was performed using the CFX96 detection system (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA). Quantification and normalization of relative mRNA gene expression was accomplished using the comparative threshold cycle (CT) method (ΔΔCT); ΔΔCT values were converted to ratios by averaged across replicates.

Data presentation and statistical analysis.

Data normality was confirmed by Shapiro-Wilk test, and comparisons between sample means were performed using two-sample Student’s t-test or Student’s t-test with multiple comparisons as needed (R statistical package). Within-group analyses were performed as the comparison between baseline and week 6 by repeated-measures one-way or two-way ANOVA. Sidak-Bonferroni methodology was used to correct for multiple comparisons (Prism, Graphpad). The level of statistical significance was defined as P < 0.05. All results are reported as means ± SE.

RESULTS

Animal characteristics and phthalate exposure.

Mice exposed to DEHP-supplemented drinking water achieved a circulating MEHP concentration of 403 ± 28.8 ng/ml compared with 0.922 ± 0.14 ng/ml in control animals (Table 1). Phthalate exposure did not alter average water intake, body weight, or heart weight (Table 1). Analysis of animal movement within the cage was also assessed to ensure that heart mass, HR, or BP measurements under basal conditions were not confounded by hyperactivity or lethargy. There were no differences in the number of entries to center, time spent in cage center, or total travel distance from the 30-min Tru Scan session (Table 1).

Table 1.

Animal characteristics

| Control | DEHP | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| MEHP serum concentration, ng/ml | 0.922 ± 0.14 | 403 ± 28.8 | <0.001* |

| Heart mass, mg | 170 ± 8.1 | 166 ± 7.1 | 0.709 |

| Heart mass/body mass, mg/g | 5.41 ± 0.3 | 5.34 ± 0.2 | 0.853 |

| Body mass, g | 31.6 ± 0.8 | 31.2 ± 1.1 | 0.525 |

| Water consumption, ml/day | 5.05 ± 1.0 | 5.34 ± 0.6 | 0.651 |

| Tru Scan | |||

| Number of center entries | 84.3 ± 27 | 93.2 ± 30 | 0.561 |

| Time in center, min | 11.8 ± 4.1 | 12.3 ± 5.9 | 0.712 |

| Distance traveled, m | 29.3 ± 4.9 | 29.8 ± 8.6 | 0.653 |

All values reported as means ± SE. DEHP, di-2-ethylhexyl-phthalate. Mono-2-ethylhexyl-phthalate (MEHP) serum concentration was measured by mass spectrometry. All values were taken at the end of the study except for water consumption, which was averaged throughout the study. Tru Scan activity measurements were from a 30-min session.

P < 0.05.

Exaggerated cardiovascular reactivity and poststress recovery in DEHP-exposed animals.

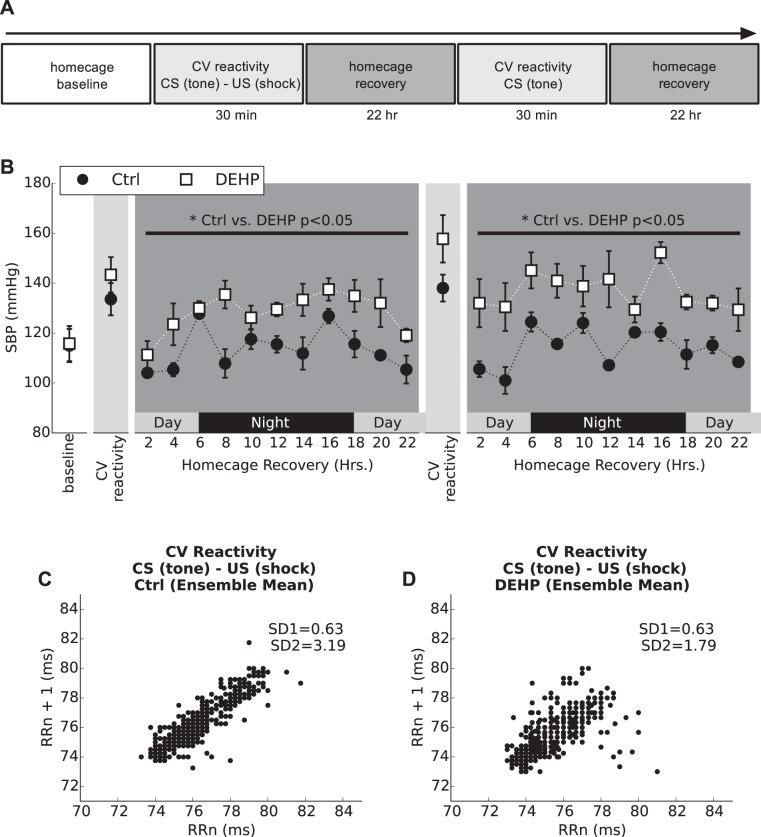

Cardiovascular reactivity testing was assessed after 4 wk of DEHP exposure to model prolonged clinical exposure resulting from multiple medical interventions. To measure the impact of DEHP exposure on autonomic function, we monitored cardiovascular response (HR, BP, and HRV) during and after (recovery) a fear-conditioning protocol (Fig. 1). As shown by others (19, 44, 85), this paradigm elicits a strong cardiovascular and autonomic response to a conditioned cue (tone). Cardiovascular reactivity to stress is an early and sensitive predictor of future pathologies (56, 76); therefore, we hypothesized that an imbalance in autonomic regulation after DEHP exposure would initially present as exaggerated cardiovascular reactivity and prolonged poststress recovery of BP (19, 37, 44).

Fig. 1.

Cardiovascular (CV) reactivity to Pavlovian fear conditioning and poststress recovery (4 wk). A: Pavlovian fear conditioning (CV reactivity) protocol timeline. B: mean systolic blood pressure (SBP) monitored throughout the course of the CV reactivity protocol (30 min). A significant elevation in SBP was observed in the di-2-ethylhexyl-phthalate (DEHP)-treated group during both recovery periods after CV reactivity testing. All values are reported as means ± SE. *P < 0.05 (two-way ANOVA). C and D: Poincaré plots were computed by the first 500 beats after the first tone/shock pair during fear conditioning (the first CV reactivity session) and ensemble averaged for the control and DEHP-treated group. DEHP-treated animals have reduced variability along the major axis (SD2). CS, conditioned stimulus; US, unconditioned stimulus.

At rest and before cardiovascular reactivity testing (4-wk treatment), no difference in SBP or HR was observed between treatment groups (114 ± 9 mmHg and 435 ± 25 beats/min for control animals and 115 ± 9.5 mmHg and 418 ± 24 beats/min for DEHP-treated animals), although HRV was significantly lower in DEHP-treated animals (HF power; Table 2). HRs were comparable during cardiovascular reactivity testing (control: 742 ± 25 beats/min vs. DEHP: 730 ± 38 beats/min). Compared with basal levels in the homecage, HRV parameters diminished significantly after initiation of the fear-conditioning protocol (tone + shock pair) in both control and DEHP-treated animals, thus highlighting the link between stress and sympathetic activity (Table 2). However, DEHP-treated animals displayed significantly lower SD2 (−56%, P < 0.05) compared with control animals, as computed by Poincaré (Fig. 1C), indicating a more intense reduction in HRV (40).

Table 2.

HR variability during cardiovascular reactivity testing (4-wk DEHP exposure)

| Homecage Baseline (4-wk exposure) |

Cardiovascular Reactivity Test 1 (4-wk exposure) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Control | DEHP | P value | Control | DEHP | P value | |

| HR, beats/min | 431 ± 35 | 413 ± 31 | 0.629 | 780 ± 13 | 794 ± 15 | 0.279 |

| RR, ms | 139 ± 6.8 | 145 ± 7.5 | 0.642 | 76.9 ± 0.8 | 75.5 ± 0.5 | 0.279 |

| SD1, ms | 5.4 ± 0.9 | 3.7 ± 0.5 | 0.270 | 0.63 ± 0.08 | 0.63 ± 0.1 | 0.971 |

| SD2, ms | 17.2 ± 2.2 | 18.3 ± 3.3 | 0.832 | 3.19 ± 0.2 | 1.79 ± 0.2* | 0.020 |

| HF power, normalized units | 353 ± 48 | 194 ± 23* | 0.0001 | 47.7 ± 17 | 51.3 ± 28.8 | 0.935 |

All values reported as means ± SE. RR and heart rate (HR) variability parameters were computed from a 500-beat segment during a homecage basal period and again after the initiation of the first conditioned stimulus (tone)-unconditioned stimulus (shock) pair (cardiovascular test 1). High-frequency (HF) power was significantly lower in di-2-ethylhexyl-phthalate (DEHP)-treated animals before reactivity testing. SD from the major (SD1) and minor axis (SD2) were computed from Poincare plots computed in the same timeframe. SD2 was significantly lower (P < 0.05) in the DEHP-treated group than in the control group during the cardiovascular test, indicating heightened reactivity.

P < 0.05.

After the 30-min reactivity test, animals were returned to their home cage, and SBP and HR were continuously monitored during the 22-h recovery period. As shown in Fig. 1, DEHP-treated animals exhibited an exaggerated and delayed poststress SBP recovery (+13% over 22 h; Fig. 1B), which may be attributed to enhanced sympathetic activity. After recovery, cardiovascular reactivity was measured in response to a conditioned stimulus (audible tone). In DEHP-treated animals, cardiovascular reactivity remained significantly elevated during the day/night recovery period (+20% over 22 h; Fig. 1B). SBP returned to baseline in both groups 72 h after completion of the cardiovascular reactivity protocol. Taken together, these data suggest that DEHP-treated animals display an exaggerated response to stress that is mediated by sympathetic dominance (19, 70).

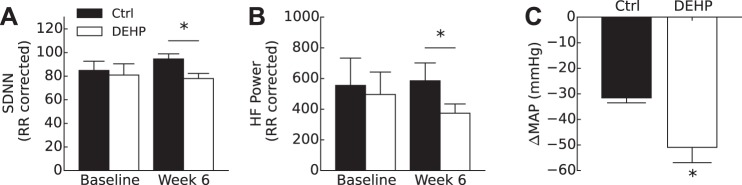

DEHP exposure increases sympathetic dominance and decreases HRV.

Alterations in cardiovascular reactivity to stress suggest an imbalance in autonomic regulation in DEHP-treated animals. To further address the impact of DEHP exposure on autonomic regulation, we analyzed HRV indexes under basal resting conditions. Time-domain measurements by SDNN showed a decrease in HRV in DEHP-treated animals (78 ± 4.3) compared with control (95 ± 4.4) at the end of the study (6 wk, P < 0.05; Fig. 2A). As a marker for parasympathetic innervation on the heart, HF power was computed and corrected for mean RR interval. HF power was also lower in the DEHP-treated group compared with the control group at rest (6 wk, P < 0.05; Fig. 2B). Raw HF power in the DEHP-treated group was 6.31 ms2 compared with 9.53 ms2 in the control group. After RR correction, normalized HF power was computed as 585 ± 117 in the control group and 374 ± 61 in the DEHP-treated group (normalized units).

Fig. 2.

Measurement of heart rate variability and sympathetic tone under basal resting conditions (6 wk, end of study). A: SD of normal beats (SDNN) was corrected for mean RR interval. A significant decrease in SDNN was found at the end of the study in the di-2-ethylhexyl-phthalate (DEHP)-treated group compared with the control (Ctrl) group. B: high-frequency (HF) power was computed by power in the band 2.5–5 Hz corrected by squared mean RR interval. A significant decrease in HF power was found in the DEHP-treated group at 6 wk compared with the Ctrl group. C: after treatment with chlorisondamine (12 mg/kg), mean arterial pressure (MAP) of the DEHP-treated group decreased significantly compared with the Ctrl group, indicating an elevated state of sympathetic tone (means ± SE). All values reported are as means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

DEHP exposure increases sympathetic tone on the cardiovascular system.

To directly investigate the contribution of the sympathetic nervous system on the cardiovascular system, animals were treated with the ganglionic blocker chlorisondamine at the end of the study (6 wk). Blockage of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in the autonomic ganglia attenuates sympathetic input to arteries, resulting in vasodilation and a decrease in BP (7, 18, 29, 91). After administration of chlorisondamine (30 min), the magnitude of sympathetic input was measured by the resulting change in MAP. Before drug administration, control and DEHP-treated groups had initial HRs of 350 and 360 beats/min, respectively (P = 0.31), and an average initial MAP of 101 ± 14 mmHg for the control group and 117 ± 3 mmHg for the DEHP-treated group. After administration of chlorisondamine, DEHP-treated animals displayed greater sympathetic tone under basal conditions, as measured by an exaggerated MAP response to ganglionic blockade (−50.9 mmHg ± 6.0 in the DEHP-treated group vs. −31.6 mmHg ± 0.6 in the control group, P < 0.05; Fig. 2C). After normalization of the initial MAP, the DEHP-treated group displayed a −69.75 ± 4.13% drop in MAP compared with −38.24 ± 7.85% in the control group.

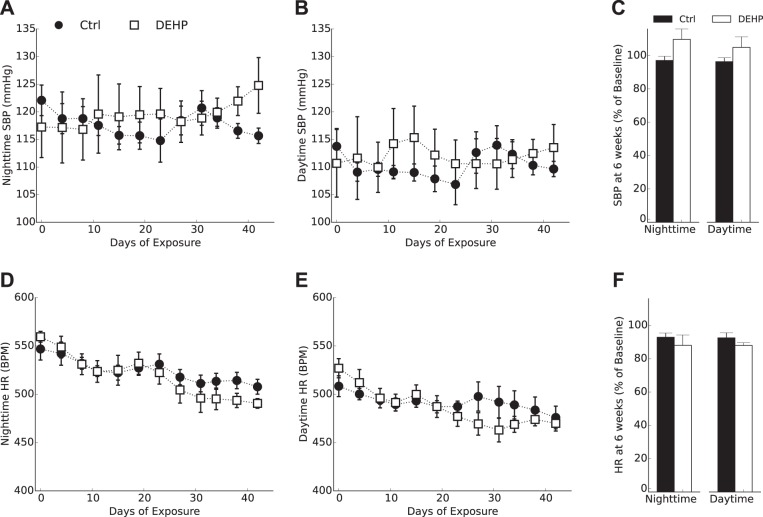

Effect of DEHP exposure on resting HR and BP.

Heightened cardiovascular reactivity and reduced HRV are early markers of cardiovascular dysfunction, which can be used to predict future pathologies (56, 76). After 6 wk of treatment, basal SBP was slightly increased in DEHP-treated animals (125 ± 4.9 mmHg) compared with control animals (116 ± 1.4 mmHg), although this parameter did not reach significance (P = 0.09; Fig. 3F). No significant difference in basal resting HR was detected between DEHP-treated (490 ± 5 beats/min, nighttime) and control animals (508 ± 3.1 beats/min; Fig. 3E). These results were not unexpected, as the timespan required to develop hypertension may exceed the time limitation of a continuous radiotelemetry monitoring protocol.

Fig. 3.

Heart rate (HR) and systolic blood pressure (SBP) under basal resting conditions. SBP (A–C) and HR measurements (D–F) were separated by time of day. SBP decreased marginally in the control (Ctrl) group to 96–97% of the baseline value and increased marginally in the di-2-ethylhexyl-phthalate (DEHP)-treated group to 105–109% of the baseline value (F). No significant difference in HR was observed between groups (F). All values are reported as means ± SE. BPM, beats/min.

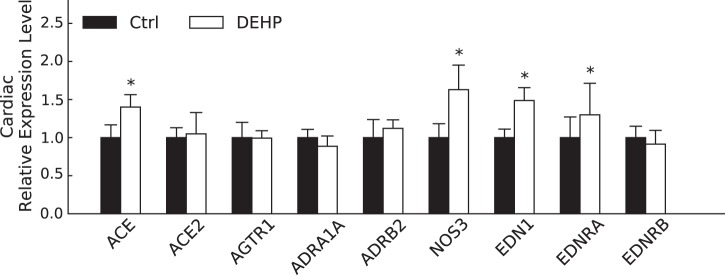

DEHP exposure alters cardiac tissue gene expression.

To identify potential mechanisms contributing to HRV alterations and poststress BP recovery, we investigated genes associated with the renin-angiotensin system, BP regulation, and autonomic balance. We detected elevated levels of NOS3 mRNA in the cardiac tissue of DEHP-treated animals (6-wk exposure; Fig. 4), which may serve as a compensatory effect to offset sympathetically mediated stimulation of β-adrenergic signaling (3, 54, 89).

Fig. 4.

Gene expression profiling of cardiac tissue. Shown are gene expression levels (ΔΔCT, where CT is threshold cycle) of cardiovascular genes involved in blood pressure regulation [angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE), ACE2, and angiotensin II type 1 receptor (AGTR1)], autonomic receptors [α1A-adrenoceptor (ADRA1A) and β2-adrenoceptor (ADRB2)], cardiac contractility [nitric oxide synthase 3 NOS3)], and vasoconstriction [endothelin-1 (EDN1), endothelin receptor type A receptor (EDNRA), and endothelin receptor type B receptor (EDRNB)]. Ctrl, control; DEHP, di-2-ethylhexyl-phthalate. All values are reported as means ± SE. *P < 0.05.

We also observed an upregulation in genes associated with hypertension, including ACE and endothelin-1, in isolated cardiac tissue from DEHP-treated animals (Fig. 4). In the renin-angiotensin system, ACE converts angiotensin I to the active vasoconstrictor angiotensin II, which exerts its actions through interactions with the angiotensin II type 1 receptor. Increased ACE expression could predispose DEHP-treated animals to elevated serum angiotensin II, provided that ACE enzymatic activity has been positively correlated with the angiotensin II serum level (27). No significant alterations in ACE2 or angiotensin II type 1 receptors were observed. Endothelin-1 is also a potent vasoconstrictor, which exerts its hypertensive effects through interaction with endothelin type A receptor. Upregulation of both endothelin-1 and endothelin type A receptors was found in DEHP-treated samples.

We did not detect a difference in the expression of genes associated with adrenergic receptors, including the α1A-adrenergic receptor, β1-adrenergic receptor, or β2-adrenergic receptor, although we cannot rule out alterations in adrenergic receptor protein expression, activity, and/or sensitivity, which were beyond the scope of this study.

DISCUSSION

For the first time, we have shown that phthalate exposure alters autonomic regulation, resulting in decreased HRV, increased sympathetic tone, and exaggerated cardiovascular reactivity and recovery to a stress stimulus. After DEHP treatment, time- and frequency-domain measurements of HRV were reduced, indicating impaired parasympathetic activity. DEHP-treated animals also exhibited an increase in total sympathetic tone, as determined by the exaggerated MAP response to ganglionic blockade. In response to conditioned stress cue, DEHP-treated animals displayed a more significant reduction in HRV and exhibited sustained SBP elevation over a 22-h recovery period. Phthalate-treated animals also had increased endothelin-1 and ACE cardiac expression, which can predispose animals to vasoconstriction, increased vascular resistance and autonomic dysfunction. Overall, our study supports our previous findings that phthalate plasticizer exposure has a profound effect on cardiovascular function (30, 64, 65).

For the described experiments, we focused our attention on early and sensitive indicators of cardiovascular and autonomic dysfunction, including HRV, sympathetic tone on the vasculature, and the magnitude of the cardiovascular response to stress. Alterations in autonomic balance can initially present as a change in HRV, even in normotensive subjects who later develop hypertension (36). Short-term HRV is dominated by respiratory sinus arrhythmia, which manifests as parasympathetic input on the sinus node. In the present study, we found a reduction in parasympathetic input on the heart, as evidenced by a decrease in HF power (2.5–5 Hz) and SDNN of the interbeat intervals, a more significant reduction in HRV during cardiovascular reactivity testing, and prolonged BP elevation. Cardiovascular reactivity to a conditioned stimulus is mediated by mass sympathetic discharge, a resulting release of catecholamines, and an increase in HR and total peripheral resistance through stimulation of adrenergic receptors in the heart and blood vessels (81). DEHP-treated animals displayed an exaggerated cardiovascular response to a conditioned stimulus, with SBP remaining 10 mmHg higher in treated animals after cardiovascular reactivity testing. We speculate that delayed BP recovery is attributed to sympathetic dominance, reduced β-adrenergic sensitivity, and/or norepinephrine spillover (19, 44, 70). Similar to HRV indexes, an exaggerated cardiovascular response to a stressor has been shown to predict future hypertension risk (55, 74, 76). Finally, abnormal autonomic nervous system cardiac control is also associated with anxiety, and reduced HRV has been consistently observed in patients with anxiety disorders (11, 28). This highlights the extensive influence of autonomic regulation on multiple disease pathologies, including cardiovascular function, behavior, and anxiety, which warrant future study in relation to phthalate exposure.

In the present study, we observed a slight elevation in SBP in DEHP-treated animals under resting basal conditions, although this trend was not significant over the 6-wk timeframe (P = 0.09). Phthalate-treated animals also displayed an upregulation of ACE and endothelin-1 in cardiac tissue, genes that encode ACE and endothelin-1, respectively. ACE is responsible for converting angiotensin I to angiotensin II, resulting in elevated vasoconstrictor activity and enhanced sympathetic drive. Importantly, we did not see a change in the expression of ACE2, the gene responsible for encoding the protein for converting angiotensin II to inactive angiotensin 1–7, which would counter the hypertensive effects of ACE1 (21). Endothelin-1 is also known for its vasoconstrictive effects and has been shown to decrease cardiac output due to increased systemic vascular resistance (1, 87). Recent studies have also highlighted the role of endothelin-1 in the interaction between sympathetic neurons and cardiac myocytes (45). Elevated levels of endothelin-1 have been observed in various pathological conditions, including heart failure, myocardial infarction, kidney disease, and hypertension (45). Increased endothelin-1 and ACE expression in phthalate-treated animals may predispose these animals to vasoconstriction and increase vascular resistance.

Epidemiological studies have established an association between DEHP exposure and a mild increase in SBP in adolescents (83, 84), estimating an approximate 1-mmHg increase with a threefold increase of DEHP exposure (84). Studies have also shown a link between elevated SBP and exposure to DEHP alternatives, including diisononyl phthalate (DINP) and diisodecyl phthalate (DIDP) (83). Moreover, ex vivo and in vitro studies have identified links between phthalate exposure and alterations in cardiac contractility and vasculature function. Labow et al. (42) showed that MEHP has a hypertensive effect on the pulmonary vasculature and a negative inotropic effect on isolated human atrial trabeculae (4). Similarly, our group has previously shown that phthalate exposure can alter Ca2+ handling and contractility in rodent and human cardiomyocytes (64, 65). In the present study, we detected an increase in NOS3 gene expression in cardiac tissue, which may attenuate β-adrenergic effects via cGMP-dependent mechanisms (3, 12, 54, 89). The latter may serve as a compensatory effect to offset stimulation of β-adrenergic signaling.

Followup studies are needed to pinpoint the underlying mechanisms responsible for the observed effects on autonomic and cardiovascular physiology. Phthalate esters, including DEHP, are endocrine disruptors that interfere with hormone homeostasis (15). Previous studies have shown that DEHP exposure reduces circulating levels of aldosterone and testosterone (52), increases adrenocorticotropin and corticosterone levels (78), and results in widespread disruption of steroidogenesis. Such alterations can contribute to autonomic imbalance and diminished HRV (61, 90). In addition, phthalates can cause a wide range of nonendocrine-related toxicities (49), including inflammation and oxidative stress (25, 26, 68). The underlying effects of DEHP on autonomic and cardiovascular function are likely to be multifactorial.

Limitations.

The present study was limited by a small sample size in a mouse model. Cardiotoxicity studies performed in mice may not yield the same results in humans, which is due in part to species differences in HR, size, and ion channel expression. To remedy high HRs and artifacts that are common in mouse radiotelemetry protocols, HR and BP data analysis was limited to 2-min continuous recordings, as previously described (80). In addition, our method of administration (oral via water supplementation) resulted in a circulating MEHP plasma level (0.403 µg/ml) that is 40 times less than maximum levels measured in pediatric patients (15.6 µg/ml) (5, 75). Additional dose-response studies are necessary to accurately predict patient safety after high clinical exposures.

Conclusion.

For the first time, we have identified a relationship between phthalate exposure, altered autonomic regulation, and cardiovascular function under basal and stress conditions (conditioned cardiovascular reactivity). HRV indexes are often used as a sensitive early indicator of cardiovascular dysfunction, serving as a precursor to clinical manifestations of hypertension, atherosclerosis, and conduction abnormalities. Sufficient HRV is considered part of the healthy interplay between cardiovascular and nervous systems, providing adaptation and regulatory capacity. HRV indexes are sensitive indicators of cardiovascular and autonomic health and are often used to predict patient recovery from intensive care, extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, and cardiopulmonary bypass. Future studies are needed to examine the risk of phthalate exposure to individuals, particularly in high-risk, high-exposure scenarios.

GRANTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants R00-ES-023477, R00-HL-10767, UL1-TR-000075, and KL2-TR-000076, the Children’s Research Institute (Divisions of Cardiology and Cardiac Surgery, to N. G. Posnack), and American Heart Association Grant 15CSA2430001.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.J., M.S., and N.G.P. analyzed data; R.J., A.S., P.M., and N.G.P. interpreted results of experiments; R.J., M.S., and N.G.P. prepared figures; R.J., P.M., and N.G.P. drafted manuscript; R.J., A.S., P.M., and N.G.P. edited and revised manuscript; R.J., A.S., M.S., N.M., P.M., and N.G.P. approved final version of manuscript; A.S., M.S., N.M., and N.G.P. performed experiments; P.M. and N.G.P. conceived and designed research.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We gratefully acknowledge Dr. Luther Swift for technical assistance with radiotelemetry experiments.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ahlborg G, Ottosson-Seeberger A, Hemsén A, Lundberg JM. Central and regional hemodynamic effects during infusion of Big endothelin-1 in healthy humans. J Appl Physiol 80: 1921–1927, 1996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AuBuchon JP, Estep TN, Davey RJ. The effect of the plasticizer di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate on the survival of stored RBCs. Blood 71: 448–452, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barouch LA, Harrison RW, Skaf MW, Rosas GO, Cappola TP, Kobeissi ZA, Hobai IA, Lemmon CA, Burnett AL, O’Rourke B, Rodriguez ER, Huang PL, Lima JAC, Berkowitz DE, Hare JM. Nitric oxide regulates the heart by spatial confinement of nitric oxide synthase isoforms. Nature 416: 337–339, 2002. doi: 10.1038/416337a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barry YA, Labow RS, Keon WJ, Tocchi M. Atropine inhibition of the cardiodepressive effect of mono(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate on human myocardium. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 106: 48–52, 1990. doi: 10.1016/0041-008X(90)90104-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Barry YA, Labow RS, Rock G, Keon WJ. Cardiotoxic effects of the plasticizer metabolite, mono (2-ethylhexyl)phthalate (MEHP), on human myocardium. Blood 72: 1438–1439, 1988. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Baudrie V, Laude D, Elghozi JL. Optimal frequency ranges for extracting information on cardiovascular autonomic control from the blood pressure and pulse interval spectrograms in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 292: R904–R912, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00488.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becker BK, Speed JS, Powell M, Pollock DM. Activation of neuronal endothelin B receptors mediates pressor response through alpha-1 adrenergic receptors. Physiol Rep 5: e13077, 2017. doi: 10.14814/phy2.13077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Billman GE. The effect of heart rate on the heart rate variability response to autonomic interventions. Front Physiol 4: 222, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Billman GE. The LF/HF ratio does not accurately measure cardiac sympatho-vagal balance. Front Physiol 4: 26, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Billman GE, Hoskins RS. Time-series analysis of heart rate variability during submaximal exercise. Evidence for reduced cardiac vagal tone in animals susceptible to ventricular fibrillation. Circulation 80: 146–157, 1989. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.80.1.146. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brudey C, Park J, Wiaderkiewicz J, Kobayashi I, Mellman TA, Marvar PJ. Autonomic and inflammatory consequences of posttraumatic stress disorder and the link to cardiovascular disease. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 309: R315–R321, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00343.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunner F, Andrew P, Wölkart G, Zechner R, Mayer B. Myocardial contractile function and heart rate in mice with myocyte-specific overexpression of endothelial nitric oxide synthase. Circulation 104: 3097–3102, 2001. doi: 10.1161/hc5001.101966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calafat AM, Needham LL, Silva MJ, Lambert G. Exposure to di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate among premature neonates in a neonatal intensive care unit. Pediatrics 113: e429–e434, 2004. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.e429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Carrive P. Dual activation of cardiac sympathetic and parasympathetic components during conditioned fear to context in the rat. Clin Exp Pharmacol Physiol 33: 1251–1254, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1681.2006.04519.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Casals-Casas C, Desvergne B. Endocrine disruptors: from endocrine to metabolic disruption. Annu Rev Physiol 73: 135–162, 2011. doi: 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cauley E, Wang X, Dyavanapalli J, Sun K, Garrott K, Kuzmiak-Glancy S, Kay MW, Mendelowitz D. Neurotransmission to parasympathetic cardiac vagal neurons in the brain stem is altered with left ventricular hypertrophy-induced heart failure. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 309: H1281–H1287, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00445.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Report on Human Exposure to Environmental Chemicals. Fourth Report, 2009. https://www.cdc.gov/exposurereport/index.html [23 October 2017].

- 18.Chadman KK, Woods JH. Cardiovascular effects of nicotine, chlorisondamine, and mecamylamine in the pigeon. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 308: 73–78, 2004. doi: 10.1124/jpet.103.057307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choi EA, Leman S, Vianna DM, Waite PM, Carrive P. Expression of cardiovascular and behavioural components of conditioned fear to context in T4 spinally transected rats. Auton Neurosci 120: 26–34, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2004.08.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Colhoun HM, Francis DP, Rubens MB, Underwood SR, Fuller JH. The association of heart-rate variability with cardiovascular risk factors and coronary artery calcification: a study in type 1 diabetic patients and the general population. Diabetes Care 24: 1108–1114, 2001. doi: 10.2337/diacare.24.6.1108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Danilczyk U, Penninger JM. Angiotensin-converting enzyme II in the heart and the kidney. Circ Res 98: 463–471, 2006. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000205761.22353.5f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon JP, Giudice LC, Hauser R, Prins GS, Soto AM, Zoeller RT, Gore AC. Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr Rev 30: 293–342, 2009. doi: 10.1210/er.2009-0002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Durand MT, Becari C, Tezini GCSV, Fazan R Jr, Oliveira M, Guatimosim S, Prado VF, Prado MA, Salgado HC. Autonomic cardiocirculatory control in mice with reduced expression of the vesicular acetylcholine transporter. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 309: H655–H662, 2015. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00114.2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Food and Drug Administration DEHP in Plastic Medical Devices. https://www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/ResourcesforYou/ucm142643.htm [23 October 2017].

- 25.Ferguson KK, Loch-Caruso R, Meeker JD. Urinary phthalate metabolites in relation to biomarkers of inflammation and oxidative stress: NHANES 1999-2006. Environ Res 111: 718–726, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ferguson KK, Loch-Caruso R, Meeker JD. Exploration of oxidative stress and inflammatory markers in relation to urinary phthalate metabolites: NHANES 1999-2006. Environ Sci Technol 46: 477–485, 2012. doi: 10.1021/es202340b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Fildes JE, Walker AH, Keevil B, Hutchinson IV, Leonard CT, Yonan N. The effects of ACE inhibition on serum angiotensin II concentration following cardiac transplantation. Transplant Proc 37: 4525–4527, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.transproceed.2005.10.099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Friedman BH. An autonomic flexibility-neurovisceral integration model of anxiety and cardiac vagal tone. Biol Psychol 74: 185–199, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsycho.2005.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gao J, Kerut EK, Smart F, Katsurada A, Seth D, Navar LG, Kapusta DR. Sympathoinhibitory Effect of Radiofrequency Renal Denervation in Spontaneously Hypertensive Rats With Established Hypertension. Am J Hypertens 29: 1394–1401, 2016. doi: 10.1093/ajh/hpw089. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Gillum N, Karabekian Z, Swift LM, Brown RP, Kay MW, Sarvazyan N. Clinically relevant concentrations of di (2-ethylhexyl) phthalate (DEHP) uncouple cardiac syncytium. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol 236: 25–38, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.taap.2008.12.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Goit RK, Ansari AH. Reduced parasympathetic tone in newly diagnosed essential hypertension. Indian Heart J 68: 153–157, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ihj.2015.08.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Green R, Hauser R, Calafat AM, Weuve J, Schettler T, Ringer S, Huttner K, Hu H. Use of di(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate-containing medical products and urinary levels of mono(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate in neonatal intensive care unit infants. Environ Health Perspect 113: 1222–1225, 2005. doi: 10.1289/ehp.7932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.[No authors listed]. Heart rate variability. Standards of measurement, physiological interpretation, and clincical use. Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and the North American Society of Pacing and Electrophysiology. Eur Heart J 17: 354–381, 1996. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Halden RU. Plastics and health risks. Annu Rev Public Health 31: 179–194, 2010. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.012809.103714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jaeger RJ, Rubin RJ. Extraction, localization, and metabolism of di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate from PVC plastic medical devices. Environ Health Perspect 3: 95–102, 1973. doi: 10.1289/ehp.730395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Joyner MJ, Charkoudian N, Wallin BG. Sympathetic nervous system and blood pressure in humans: individualized patterns of regulation and their implications. Hypertension 56: 10–16, 2010. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.109.140186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Judy WV, Watanabe AM, Henry DP, Besch HR Jr, Murphy WR, Hockel GM. Sympathetic nerve activity: role in regulation of blood pressure in the spontaenously hypertensive rat. Circ Res 38, Suppl 2: 21–29, 1976. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.38.6.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kamen PW, Tonkin AM. Application of the Poincaré plot to heart rate variability: a new measure of functional status in heart failure. Aust N Z J Med 25: 18–26, 1995. doi: 10.1111/j.1445-5994.1995.tb00573.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Karle VA, Short BL, Martin GR, Bulas DI, Getson PR, Luban NL, O’Brien AM, Rubin RJ. Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation exposes infants to the plasticizer, di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate. Crit Care Med 25: 696–703, 1997. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199704000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Karmakar CK, Khandoker AH, Voss A, Palaniswami M. Sensitivity of temporal heart rate variability in Poincaré plot to changes in parasympathetic nervous system activity. Biomed Eng Online 10: 17, 2011. doi: 10.1186/1475-925X-10-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Koizumi S, Minamisawa S, Sasaguri K, Onozuka M, Sato S, Ono Y. Chewing reduces sympathetic nervous response to stress and prevents poststress arrhythmias in rats. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H1551–H1558, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01224.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Labow RS, Barry YA, Tocchi M, Keon WJ. The effect of mono(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate on an isolated perfused rat heart-lung preparation. Environ Health Perspect 89: 189–193, 1990. doi: 10.1289/ehp.9089189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lawler JE, Barker GF, Hubbard JW, Cox RH, Randall GW. Blood pressure and plasma renin activity responses to chronic stress in the borderline hypertensive rat. Physiol Behav 32: 101–105, 1984. doi: 10.1016/0031-9384(84)90078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.LeDoux JE, Sakaguchi A, Reis DJ. Behaviorally selective cardiovascular hyperreactivity in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Evidence for hypoemotionality and enhanced appetitive motivation. Hypertension 4: 853–863, 1982. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.4.6.853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lehmann LH, Stanmore DA, Backs J. The role of endothelin-1 in the sympathetic nervous system in the heart. Life Sci 118: 165–172, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.lfs.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lind PM, Lind L. Circulating levels of bisphenol A and phthalates are related to carotid atherosclerosis in the elderly. Atherosclerosis 218: 207–213, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.atherosclerosis.2011.05.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Loff S, Kabs F, Witt K, Sartoris J, Mandl B, Niessen KH, Waag KL. Polyvinylchloride infusion lines expose infants to large amounts of toxic plasticizers. J Pediatr Surg 35: 1775–1781, 2000. doi: 10.1053/jpsu.2000.19249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luban N, Rais-Bahrami K, Short B. I want to say one word to you−just one word− “plastics”. Transfusion 46: 503–506, 2006. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2006.00766.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Mallow EB, Fox MA. Phthalates and critically ill neonates: device-related exposures and non-endocrine toxic risks. J Perinatol 34: 892–897, 2014. doi: 10.1038/jp.2014.157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Malpas SC. Sympathetic nervous system overactivity and its role in the development of cardiovascular disease. Physiol Rev 90: 513–557, 2010. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00007.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Martelli D, Silvani A, McAllen RM, May CN, Ramchandra R. The low frequency power of heart rate variability is neither a measure of cardiac sympathetic tone nor of baroreflex sensitivity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H1005–H1012, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00361.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Martinez-Arguelles DB, Guichard T, Culty M, Zirkin BR, Papadopoulos V. In utero exposure to the antiandrogen di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate decreases adrenal aldosterone production in the adult rat. Biol Reprod 85: 51–61, 2011. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.110.089920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Marvar PJ, Goodman J, Fuchs S, Choi DC, Banerjee S, Ressler KJ. Angiotensin type 1 receptor inhibition enhances the extinction of fear memory. Biol Psychiatry 75: 864–872, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.08.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Massion PB, Feron O, Dessy C, Balligand JL. Nitric oxide and cardiac function: ten years after, and continuing. Circ Res 93: 388–398, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000088351.58510.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Matthews CE, Pate RR, Jackson KL, Ward DS, Macera CA, Kohl HW, Blair SN. Exaggerated blood pressure response to dynamic exercise and risk of future hypertension. J Clin Epidemiol 51: 29–35, 1998. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(97)00223-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Matthews KA, Woodall KL, Allen MT. Cardiovascular reactivity to stress predicts future blood pressure status. Hypertension 22: 479–485, 1993. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.22.4.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Moak JP, Goldstein DS, Eldadah BA, Saleem A, Holmes C, Pechnik S, Sharabi Y. Supine low-frequency power of heart rate variability reflects baroreflex function, not cardiac sympathetic innervation. Heart Rhythm 4: 1523–1529, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.hrthm.2007.07.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Mousa TM, Schiller AM, Zucker IH. Disruption of cardiovascular circadian rhythms in mice post myocardial infarction: relationship with central angiotensin II receptor expression. Physiol Rep 2: e12210, 2014. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ng J, Sundaram S, Kadish AH, Goldberger JJ. Autonomic effects on the spectral analysis of heart rate variability after exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1421–H1428, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00217.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Olsén L, Lind L, Lind PM. Associations between circulating levels of bisphenol A and phthalate metabolites and coronary risk in the elderly. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 80: 179–183, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoenv.2012.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pongkan W, Chattipakorn SC, Chattipakorn N. Chronic testosterone replacement exerts cardioprotection against cardiac ischemia-reperfusion injury by attenuating mitochondrial dysfunction in testosterone-deprived rats. PLoS One 10: e0122503, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0122503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Posnack NG. The adverse cardiac effects of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate and Bisphenol A. Cardiovasc Toxicol 14: 339–357, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s12012-014-9258-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Posnack NG, Idrees R, Ding H, Jaimes R 3rd, Stybayeva G, Karabekian Z, Laflamme MA, Sarvazyan N. Exposure to phthalates affects calcium handling and intercellular connectivity of human stem cell-derived cardiomyocytes. PLoS One 10: e0121927, 2015. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0121927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Posnack NG, Lee NH, Brown R, Sarvazyan N. Gene expression profiling of DEHP-treated cardiomyocytes reveals potential causes of phthalate arrhythmogenicity. Toxicology 279: 54–64, 2011. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2010.09.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Posnack NG, Swift LM, Kay MW, Lee NH, Sarvazyan N. Phthalate exposure changes the metabolic profile of cardiac muscle cells. Environ Health Perspect 120: 1243–1251, 2012. doi: 10.1289/ehp.1205056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Rais-Bahrami K, Nunez S, Revenis ME, Luban LC, Short BL. Adolescents exposed to DEHP in plastic tubing as neonates: research briefs. Pediatr Nurs 30: 406 and 433 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.von Rettberg H, Hannman T, Subotic U, Brade J, Schaible T, Waag KL, Loff S. Use of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate-containing infusion systems increases the risk for cholestasis. Pediatrics 124: 710–716, 2009. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-1765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sacha J. Why should one normalize heart rate variability with respect to average heart rate. Front Physiol 4: 306, 2013. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2013.00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Sakaguchi A, LeDoux JE, Reis DJ. Sympathetic nerves and adrenal medulla: contributions to cardiovascular-conditioned emotional responses in spontaneously hypertensive rats. Hypertension 5: 728–738, 1983. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.5.5.728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schafe GE, Nader K, Blair HT, LeDoux JE. Memory consolidation of Pavlovian fear conditioning: a cellular and molecular perspective. Trends Neurosci 24: 540–546, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0166-2236(00)01969-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schroeder EB, Liao D, Chambless LE, Prineas RJ, Evans GW, Heiss G. Hypertension, blood pressure, and heart rate variability: the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities (ARIC) study. Hypertension 42: 1106–1111, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000100444.71069.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Simms AE, Paton JFR, Pickering AE, Allen AM. Amplified respiratory-sympathetic coupling in the spontaneously hypertensive rat: does it contribute to hypertension? J Physiol 587: 597–610, 2009. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.165902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Singh JP, Larson MG, Manolio TA, O’Donnell CJ, Lauer M, Evans JC, Levy D. Blood pressure response during treadmill testing as a risk factor for new-onset hypertension. The Framingham heart study. Circulation 99: 1831–1836, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.99.14.1831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Sjöberg PO, Bondesson UG, Sedin EG, Gustafsson JP. Exposure of newborn infants to plasticizers. Plasma levels of di-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate and mono-(2-ethylhexyl) phthalate during exchange transfusion. Transfusion 25: 424–428, 1985. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1985.25586020115.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Steptoe A, Marmot M. Impaired cardiovascular recovery following stress predicts 3-year increases in blood pressure. J Hypertens 23: 529–536, 2005. doi: 10.1097/01.hjh.0000160208.66405.a8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Stiedl O, Spiess J. Effect of tone-dependent fear conditioning on heart rate and behavior of C57BL/6N mice. Behav Neurosci 111: 703–711, 1997. doi: 10.1037/0735-7044.111.4.703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Supornsilchai V, Söder O, Svechnikov K. Stimulation of the pituitary-adrenal axis and of adrenocortical steroidogenesis ex vivo by administration of di-2-ethylhexyl phthalate to prepubertal male rats. J Endocrinol 192: 33–39, 2007. doi: 10.1677/JOE-06-0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Takatori S, Kitagawa Y, Kitagawa M, Nakazawa H, Hori S. Determination of di(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate and mono(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate in human serum using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. J Chromatogr B Analyt Technol Biomed Life Sci 804: 397–401, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2004.01.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Thireau J, Zhang BL, Poisson D, Babuty D. Heart rate variability in mice: a theoretical and practical guide. Exp Physiol 93: 83–94, 2008. doi: 10.1113/expphysiol.2007.040733. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Thompson JA, D’Angelo G, Mintz JD, Fulton DJ, Stepp DW. Pressor recovery after acute stress is impaired in high fructose-fed Lean Zucker rats. Physiol Rep 4: e12758, 2016. doi: 10.14814/phy2.12758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Trasande L, Attina TM. Association of exposure to di-2-ethylhexylphthalate replacements with increased blood pressure in children and adolescents. Hypertension 66: 301–308, 2015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.115.05603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Trasande L, Sathyanarayana S, Spanier AJ, Trachtman H, Attina TM, Urbina EM. Urinary phthalates are associated with higher blood pressure in childhood. J Pediatr 163: 747–753.e1, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2013.03.072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ulrich-Lai YM, Herman JP. Neural regulation of endocrine and autonomic stress responses. Nat Rev Neurosci 10: 397–409, 2009. doi: 10.1038/nrn2647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Valkama JO, Huikuri HV, Koistinen MJ, Yli-Mäyry S, Juhani Airaksinen KE, Myerburg RJ. Relation between heart rate variability and spontaneous and induced ventricular arrhythmias in patients with coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 25: 437–443, 1995. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00392-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Vuurmans TJ, Boer P, Koomans HA. Effects of endothelin-1 and endothelin-1 receptor blockade on cardiac output, aortic pressure, and pulse wave velocity in humans. Hypertension 41: 1253–1258, 2003. doi: 10.1161/01.HYP.0000072982.70666.E8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wainford RD, Carmichael CY, Pascale CL, Kuwabara JT. Gαi2-protein-mediated signal transduction: central nervous system molecular mechanism countering the development of sodium-dependent hypertension. Hypertension 65: 178–186, 2015. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.114.04463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Wang H, Kohr MJ, Wheeler DG, Ziolo MT. Endothelial nitric oxide synthase decreases β-adrenergic responsiveness via inhibition of the L-type Ca2+ current. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 294: H1473–H1480, 2008. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01249.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Wranicz JK, Rosiak M, Cygankiewicz I, Kula P, Kula K, Zareba W. Sex steroids and heart rate variability in patients after myocardial infarction. Ann Noninvasive Electrocardiol 9: 156–161, 2004. doi: 10.1111/j.1542-474X.2004.92539.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Xia H, Suda S, Bindom S, Feng Y, Gurley SB, Seth D, Navar LG, Lazartigues E. ACE2-mediated reduction of oxidative stress in the central nervous system is associated with improvement of autonomic function. PLoS One 6: e22682, 2011. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yoo CS, Lee K, Yi SH, Kim J-S, Kim H-C. Association of heart rate variability with the framingham risk score in healthy adults. Korean J Fam Med 32: 334–340, 2011. doi: 10.4082/kjfm.2011.32.6.334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]