Antecedent treatment with the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel opener NS-1619 24 h before ischemia-reperfusion limits postischemic tissue injury by an oxidant-dependent mechanism. The present study shows that NS-1619-induced oxidant production prevents ischemia-reperfusion-induced inflammation and mucosal barrier disruption in the small intestine by provoking increases in heme oxygenase-1 activity.

Keywords: pharmacological preconditioning, leukocyte rolling, leukocyte adhesion, mucosal permeability, large conductance, calcium-activated potassium channel, reactive oxygen species

Abstract

Activation of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channels evokes cell survival programs that mitigate intestinal ischemia and reperfusion (I/R) inflammation and injury 24 h later. The goal of the present study was to determine the roles of reactive oxygen species (ROS) and heme oxygenase (HO)-1 in delayed acquisition of tolerance to I/R induced by pretreatment with the BKCa channel opener NS-1619. Superior mesentery arteries were occluded for 45 min followed by reperfusion for 70 min in wild-type (WT) or HO-1-null (HO-1−/−) mice that were pretreated with NS-1619 or saline vehicle 24 h earlier. Intravital microscopy was used to quantify the numbers of rolling and adherent leukocytes. Mucosal permeability, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) levels, and HO-1 activity and expression in jejunum were also determined. I/R induced leukocyte rolling and adhesion, increased intestinal TNF-α levels, and enhanced mucosal permeability in WT mice, effects that were largely abolished by pretreatment with NS-1619. The anti-inflammatory and mucosal permeability-sparing effects of NS-1619 were prevented by coincident treatment with the HO-1 inhibitor tin protoporphyrin-IX or a cell-permeant SOD mimetic, Mn(III)tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin (MnTBAP), in WT mice. NS-1619 also increased jejunal HO-1 activity in WT animals, an effect that was attenuated by treatment with the BKCa channel antagonist paxilline or MnTBAP. I/R also increased postischemic leukocyte rolling and adhesion and intestinal TNF-α levels in HO-1−/− mice to levels comparable to those noted in WT animals. However, NS-1619 was ineffective in preventing these effects in HO-1-deficient mice. In summary, our data indicate that NS-1619 induces the development of an anti-inflammatory phenotype and mitigates postischemic mucosal barrier disruption in the small intestine by a mechanism that may involve ROS-dependent HO-1 activity.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Antecedent treatment with the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel opener NS-1619 24 h before ischemia-reperfusion limits postischemic tissue injury by an oxidant-dependent mechanism. The present study shows that NS-1619-induced oxidant production prevents ischemia-reperfusion-induced inflammation and mucosal barrier disruption in the small intestine by provoking increases in heme oxygenase-1 activity.

ischemia and reperfusion (I/R) induce microvascular and parenchymal cell injury that compromises tissue function and can ultimately lead to cell death. Although reestablishing the blood supply as quickly as possible has been a major therapeutic goal to reduce ischemic injury, reperfusion is not without peril as it can induce significant oxidant stress and leukocyte infiltration in the affected region. Recognition of the fact that leukocyte-dependent reperfusion injury is a major contributor to tissue damage beyond that conferred by ischemia alone has led to an intensive research effort directed at developing therapies to limit this component of I/R (22, 31, 46). In this regard, the discovery by Murry et al. (47) that prior exposure to brief, intermittent periods of ischemia (ischemic preconditioning) significantly reduced myocardial infarct size caused by a subsequent prolonged ischemic insult was a major advance. Not only has ischemic preconditioning proven to be the most powerful protective intervention in I/R that has been discovered to date, but also ensuing studies have demonstrated that adenosine, ATP-sensitive K+ (KATP) channels, opioids, endothelial nitric oxide (NO) synthase (eNOS), inducible NOS (iNOS), and heme oxygenase (HO)-1 play key roles in the acquisition of tolerance to I/R in ischemic preconditioning (9, 15, 38, 53, 54). Importantly, these mechanistic findings allowed for the identification and development of potential pharmacological mimetics of ischemic preconditioning such as exogenous adenosine or opioids, KATP channel activators, NO donors, and reaction products of HO-1 such as carbon monoxide (CO) (12, 14–16, 23, 32, 38, 39, 49, 62, 71–73). Each of these chemical agents has been shown to produce protected states in the setting of I/R and represent therapeutic approaches that should be more useful clinically than subjecting endangered tissues to short bouts of intermittent ischemia.

Large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channels have also been implicated in ischemic, H2S, and ethanol preconditioning (3, 7, 27, 30, 42, 55, 61, 63, 65, 77). With the development of specific BKCa channel openers such as 1,3-dihydro-1-[2-hydroxy-5-(trifluoromethyl)phenyl]-5-(trifluo-romethyl)-2H-benzimidazol-2-one (NS-1619), more recent work has demonstrated that pharmacological activation of BKCa channels induces the development of a protected state such that tissues are rendered resistant to the deleterious effects of subsequent I/R (59, 70, 77). However, unlike the effect of KATP channel activators, opening BKCa channels with NS-1619 induces preconditioning by a mechanism that is independent of NOS (60). Interestingly, coincident treatment with oxidant scavengers completely abolishes the protection afforded by NS-1619 (17, 18, 26, 59). These results suggest that NS-1619-induced entrance into a preconditioned state is initiated by the formation of reactive oxygen species (ROS).

Although the downstream signaling targets that might serve as mediators or effectors of NS-1619-induced oxidant formation remain unclear, a number of characteristics point to the possibility that HO-1 may play a role. HO-1 is a microsomal protein that catalyzes the rate-limiting step in the degradation of heme to equimolar amounts of CO, iron, and biliverdin, an oxidative reaction that can be inhibited by various metalloporphyrins, including tin protoporphyrin-IX (SnPP). In mammalian systems, biliverdin is subsequently reduced to bilirubin by the cytosolic enzyme biliverdin reductase. Induction of HO-1, also known as heat shock protein 32, serves important cytoprotective roles by catabolizing prooxidant heme to the antioxidant bile pigments biliverdin and bilirubin and by upregulating the expression of ferritin, which chelates iron, thereby exerting an additional antioxidant effect (44). The generation of bilirubin and CO by HO-1 also exerts powerful antiadhesive effects in postcapillary venules (15). Moreover, HO-1 is upregulated by oxidative stress (67). HO-1 and its enzymatic products not only are key players in the maintenance of antioxidant/oxidant homeostasis but also function as important intracellular signaling molecules (8, 43). It has been demonstrated that the HO-1 system mediates the cytoprotection elicited by preconditioning with 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK) activators, H2S, doxorubicin, or short bouts of ischemia in different I/R injury models (15, 28, 39, 45). Additionally, local overexpression of HO-1 ameliorates postischemic tissue damage (34). On the basis of these observations, we postulated that the anti-inflammatory and mucosal permeability-sparing actions of late preconditioning with the BKCa channel opener NS-1619 (NS-1619-PC) were dependent on the function of HO-1, would be prevented by treatment of wild-type (WT) mice with an HO inhibitor, and would be absent in HO-1 knockout mice. Second, we hypothesized that BKCa channel activation with NS-1619 would increase HO-1 activity by a ROS-dependent mechanism in the small intestine and that antioxidant treatment coincident with the administration of NS-1619 would prevent the postischemic anti-inflammatory and mucosal permeability-sparing effects of preconditioning with this BKCa channel activator.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Animals

WT male C57BL/6J mice (6–7 wk of age) and WT H129 (HO-1+/+) mice were obtained from the Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). HO-1−/− mice on the H129 background were provided as a generous gift by Dr. William Fay (University of Missouri). All mice were maintained on standard mouse chow and water ad libitum with a 12:12-h light-dark cycle and used at 8–10 wk of age. The experimental procedures described here were performed according to the criteria listed in the National Institutes of Health guidelines and were approved by the University of Missouri Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee.

Surgical Procedures and Induction of Intestinal I/R

Mice within each group were anesthetized with a cocktail of ketamine (150 mg/kg body wt ip) and xylazine (7.5 mg/kg body wt ip). Body temperature of mice was maintained at 37°C by a heating pad. After a surgical plane of anesthesia was achieved, a tracheotomy was performed to maintain patent airway. Systemic arterial pressure was continuously monitored by a Statham P23A pressure transducer (Gould) connected to the carotid artery catheter and recorded by a personal computer equipped with an analog-to-digital converter (MP100, Biopac System). Carboxyfluorescein diacetate succinimidyl ester (CFDA-SE; Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), a fluorescent dye, was used to label leukocytes and administered through the right jugular vein. CFDA-SE stock (5 mg/ml) was prepared by adding DMSO; the resulting solution was then aliquoted and stored in light-tight containers at −70°C until use. To induce intestinal I/R, a midline abdominal incision was made, and the superior mesenteric artery was occluded with a microvascular clip for 0 min (sham) or 45 min. At the end of the 45 min, the clip was gently removed and leukocytes were labeled by intravenous administration of the fluorochrome solution (250 μg/ml saline) at 20 μl/min for 5 min. Rolling and adhesive leukocytes were counted over minutes 30–40 and 60–70 of reperfusion.

Intravital Fluorescence Microscopy

Mice were positioned on a 30 × 20-cm Plexiglas board in a manner that allowed a selected section of jejunum to be easily exteriorized and spread gently over a glass slide covering a 4 × 3-cm rectangular opening centered in the Plexiglas. Body temperature of the mouse was maintained between 36.5 and 37.5°C using a thermostatically controlled heat lamp. The exposed small intestine was superfused with bicarbonate-buffered saline (BBS; pH 7.4) at 1.5 ml/min using a peristaltic pump (model M312, Gilson). The superfusate was maintained at 37 ± 0.5°C by pumping the solution through a heat exchanger warmed by a constant-temperature circulator (model 1130, VWR). The exteriorized region of the small bowel was also covered with BBS-soaked gauze and cellophane to prevent tissue dehydration and to minimize temperature changes and the influence of respiratory movements. The board was mounted on the stage of an inverted microscope (Diaphot TMD-EF, Nikon), and a ×20 objective lens was used to observe the intestinal microcirculation. Fluorescence images (excitation wavelength: 420–490 nm; emission wavelength: 520 nm) of postcapillary venules were detected with a charge-coupled device camera (XC-77, Hamamatsu Photonics) and an intensifier head (M4314, Hamamatsu Photonics) attached to the camera. Microfluorographs were projected on a television monitor (PVM-1953MD, Sony) and recorded on DVD using a DVD video recorder (DMR-E50, Panasonic) for offline quantification during playback of the recorded images. A video time-date generator (WJ810, Panasonic) displayed the stopwatch function on the monitor.

Intravital microscopic measurements were obtained over minutes 30–40 and 60–70 of reperfusion or at equivalent time points in the control groups. Ten straight, unbranched venules (20–50 µm in diameter and 100 µm in length) were observed, each for at least 30 s. The numbers of rolling and firmly adherent leukocytes were counted in each of the 10 venules and later quantified by the calculation of mean values. Rolling cells are defined as leukocytes moving in the microvessel at a velocity that was significantly lower than centerline velocity (78). Leukocytes were considered firmly adherent if they attached to the venular wall and did not move or detach for a period equal to or longer than 30 s (78). The numbers of rolling or adherent leukocytes were normalized by expressing each as the number of cells per square millimeter vessel area.

Mucosal Permeability Assessment

In separate groups of animals, the plasma-to-lumen clearance of 51Cr-labeled EDTA was measured using previously described methods (33, 37). After induction of anesthesia as described above, an abdominal midline incision was performed, and both kidneys were ligated to prevent excretion of 51Cr-labeled EDTA. A 4- to 5-cm loop of jejunum was then isolated with the blood supply left intact. Inflow and outflow tubes were secured on each end of the jejunal segment and perfused with warmed PBS at a rate of 0.5 ml/min. The jejunal segment and abdominal contents were covered in saline-soaked gauze and covered with clear plastic wrap to minimize evaporation and tissue dehydration. 51Cr-labeled EDTA (50 μCi) was injected via the jugular vein and allowed to equilibrate in the tissues for 30 min followed by a 30-min control period, a 45-min ischemic period, and 70 min of reperfusion, during which samples of the luminal perfusate were collected at 10-min intervals. A single sample of plasma (100 μl) was obtained by cardiac puncture at the end of the experimental protocol. Plasma and luminal perfusate 51Cr-labeled EDTA activities were measured on a gamma counter, with automatic correction for background activity. The plasma-to-lumen clearance of 51Cr-labeled EDTA (in ml·min−1·100 g−1) was calculated from the counts per minute (cpm) in the perfusate times the perfusion rate times 100 divided by the cpm in plasma times the weight of the intestinal segment in grams.

Tumor Necrosis Factor-α Assay

At the end of each experiment, a section of jejunum (3 cm) was washed with PBS (pH 7.4) and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Pulverized frozen tissue was transferred into 0.5 ml lysis buffer [10 mM Tris·HCl (pH 7.4), 150 mM NaCl, 1% Triton X-100, 1 mmol phenylmethylsulphonyl fluoride, and 1:100 protease inhibitor cocktail] and sonicated for 2 × 10 s. The homogenate was then centrifuged at 12,000 g for 10 min at 4°C. Aliquots of the supernatants were stored at −80°C until analysis. Total protein in the supernatants was measured by a Bio-Rad detergent-compatible protein assay reagent (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA). Tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α levels were measured in duplicate by ELISA (KRC3012, Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The minimum detectable dose of TNF-α is <4 pg/ml. Intestinal TNF-α levels were expressed as picograms per gram of protein.

HO Activity

HO converts heme to biliverdin, which is subsequently reduced to bilirubin by biliverdin reductase (BVR). HO activity was detected using a coupled heme degradation assay supplemented with BVR to determine bilirubin levels as a marker of HO activity. The complete conversion of heme to bilirubin requires the cofactor NADPH and cytochrome c (P-450) reductase. Bilirubin was readily detected using a scanning spectrophotometer. The reaction was performed under reduced light conditions to limit destruction of bilirubin, which is photosensitive. In brief, frozen jejunum (∼0.05 g) was homogenized in 10 volumes (wt/vol) of ice-cold (4°C) homogenization buffer (pH 7.4) containing 1.15% KCl, 50 mM Tris·HCl, and 1 mM EDTA for ~20 s and then sonicated for 10 s × 2. The homogenate was subsequently centrifuged at 10,000 g for 20 min at 4°C. The resulting supernatant was ultracentrifuged at 105,000 g (39,000 rpm) and resuspended in buffer (0.1 M potassium PBS, pH 7.5). Each reaction was started by adding NADPH solution to the vials in 5-s intervals. Samples were incubated for 30 min at 37°C with the reactions terminated by placing the tubes on ice. All tubes were measured by a scanning spectrophotometer between 450 and 550 nm.

The activity of HO was determined from the difference between the blank tubes (tubes in which NADPH was substituted by double-distilled H2O) and tubes containing NADPH. The Beer-Lambert law was used to calculate the concentration of bilirubin produced (A = ε × l × c, where A is measured absorbance, l is path length, and c is concentration) using an extinction coefficient (ε) of 40 mM−1·cm−2. HO activity was calculated in picomoles of bilirubin produced per hour per milligram protein, and all values were normalized to sham.

Western Blot Analysis of Whole Gut HO-1 Expression

At the conclusion of the experimental period (1 or 4 h), a 1-cm section of midjejunum was washed free of luminal material with ice-cold saline and then frozen in liquid nitrogen. Jejunal segments were then thoroughly homogenized in 0.6 ml PBS + 1% Triton X-100 + protease inhibitor cocktail (no. P8340, Sigma) for 4–8 min at maximum (setting 12) using a Bullet Blendor (Next Advance, Averill Park, NY). Homogenates were sonicated on ice, and cellular debris was then pelleted by centrifuging at 1,000 g for 5 min at 4°C. The supernatant was centrifuged again at 12,000 g for 10 min, and this final supernatant was assayed for protein content.

Cytosolic lysates (30 µg protein) were subjected to SDS-PAGE and Western blot analysis; blots were probed for both HO-1 and GAPDH using specific primary antibodies (Enzo Life Sciences, Farmingdale, NY, and Chemicon, Temecula, CA, respectively). After incubation with horseradish peroxidase-coupled secondary antibodies (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA), blots were developed using chemiluminescent detection (Super West Pico, Pierce/ThermoFisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Semiquantitative densitometric analysis of detected signals was performed, HO-1 signals for each sample were normalized to the respective signal for GAPDH, and effects of each treatment on HO-1 expression were expressed as a percentage of the normalized signal for the sham group.

Chemicals

NS-1619 was purchased from BioMol (Plymouth Meeting, PA), SnPP was purchased from Frontier Scientific (Logan, UT), Mn(III)tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin (MnTBAP) was obtained from Calbiochem (La Jolla, CA), and all other chemicals were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO).

Experimental Protocols

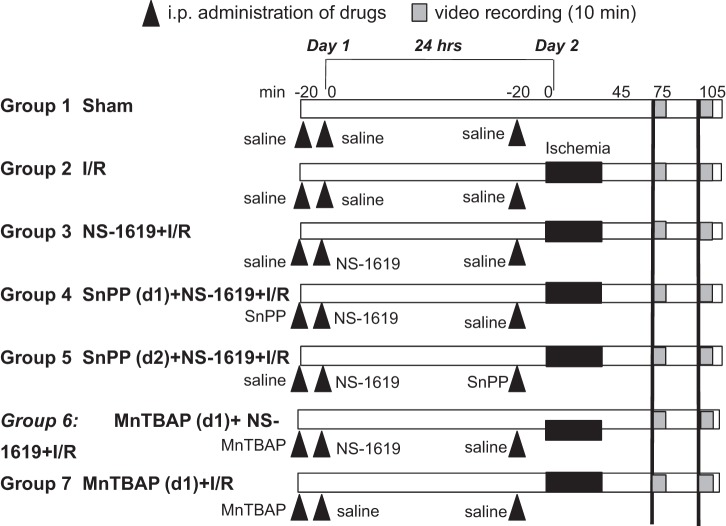

Figure 1 shows the general design of the experimental protocols for each group in the study. WT C57BL/6J mice were used for the first seven groups below. Specific drugs and doses were selected on the basis of previous experiments in our laboratory (5). At least six animals were used in each group below (individual group numbers listed below).

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of the experimental protocols assigned to each group. The numbers along the top of the diagram in minutes refer to the timeline of the protocol on day 1, 24 h before ischemia-reperfusion (I/R), and day 2, the day of I/R. Hatched bars indicate digital video recording (10 min each); solid black bars indicate the 45-min period of ischemia during which the superior mesentery artery was occluded. Solid triangles indicate administration of drug. See text for further details. SnPP, tin protoporphyrin-IX; MnTBAP, Mn(III)tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin; d1 and d2, days 1 and 2.

Group 1: sham.

As a time control for the effects of experimental duration, mice in group 1 (n = 6) received intraperitoneal injections of 0.25-ml saline with or without 2% DMSO, which was used as a vehicle for NS-1619 at different time points. All mice underwent surgery 24 h later (day 2) with the superior mesenteric artery exposed but not occluded. Leukocyte/endothelial cell rolling and adhesive interactions were quantified at time points comparable to those obtained in mice subjected to intestinal I/R (see group 2 below).

Group 2: I/R alone.

Mice in group 2 (n = 6) were treated as described for group 1 above except that I/R was induced 24 h after intraperitoneal injections of vehicles for NS-1619, SnPP, and MnTBAP. The superior mesenteric artery was occluded for 45 min followed by reperfusion for 70 min. Leukocyte rolling and adhesion were quantified during minutes 30–40 and 60–70 of reperfusion.

Group 3: NS-1619 + I/R.

To evaluate the effectiveness of the BKCa channel opener NS-1619 as a preconditioning stimulus to prevent I/R-induced leukocyte rolling and adhesion, mice in group 3 (n = 6) were treated as described for group 2 except that NS-1619 was administered 24 h before I/R. NS-1619 was dissolved in DMSO and diluted in saline (1 mg/kg, 0.25 ml/25 g body wt ip) immediately before use.

Group 4: SnPP (day 1) + NS-1619 + I/R.

To explore the mechanisms underlying the development of anti-inflammatory phenotype induced by late-phase NS-1619-PC, we first investigated the role of HO-1 as an initiator in NS-1619-PC. Mice (n = 7) in group 4 received the same treatment as group 3 except that the HO-1 inhibitor SnPP (10 mg/kg, 0.25 ml/25 g body wt ip, pH 7.4) was administered 20 min before the injection of NS-1619.

Group 5: SnPP (day 2) + NS-1619 + I/R.

To investigate the possible role of HO-1 as an anti-inflammatory effector during I/R in animals that had been preconditioned with NS-1619 24 h earlier, mice in group 5 (n = 6) were treated as described above in group 3 except that SnPP was administered 20 min before the induction of intestinal I/R.

Group 6: MnTBAP (day 1) + NS-1619 + I/R.

To test whether the presence of ROS on the first day is essential for NS-1619-PC, mice in group 6 (n = 7) were treated as described above in group 3 except that MnTBAP (10 mg/kg, 0.25 ml/25 g body wt ip) was administered 20 min before the injection of NS-1619.

Group 7: MnTBAP (day 1) + I/R.

To test whether the presence of MnTBAP on the first day influenced I/R-induced leukocyte rolling and adhesion on the second day, mice in group 7 (n = 6) were treated as described above in group 2 except that MnTBAP was administered 24 h before the induction of I/R.

Group 8: sham (HO-1+/+), group 9: I/R only (HO-1+/+), and group 10: NS-1619 + I/R (HO-1+/+).

The protocols outlined for groups 1–3, respectively, were repeated in WT littermates (HO-1+/+) of HO-1 knockout animals (H129 strain). This allowed us to compare baseline levels (no ischemia or sham), the effects of I/R alone, and the effectiveness of NS-1619 as a preconditioning stimulus on leukocyte rolling and adhesion in this strain versus the WT C57BL/6J mice used in groups 1–3 above (n = 5 for all groups).

Group 11: sham (HO-1−/−), group 12: I/R only (HO-1−/−), and group 13: NS-1619 + I/R (HO-1−/−).

To evaluate the effect of genetic HO-1 ablation on NS-1619-PC to prevent I/R-induced leukocyte rolling and adhesion, the same protocols outlined for groups 1–3 above were repeated with HO-1 knockout mice (n = 6 each).

Groups 14–18: mucosal permeability studies.

The protocols described above for groups 1–4 and 6 were repeated in separate animals to determine whether NS-1619 preconditioning would prevent I/R-induced mucosal barrier disruption (group 16) relative to sham (no ischemia, group 14) or I/R alone (group 15), as assessed by plasma-to-lumen 51Cr-labeled EDTA clearance, and whether this protective effect was prevented by SnPP (group 17) or MnTBAP (group 18) (n = 8 in each group).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with standard statistical analysis, i.e., one-way ANOVA with Scheffe’s test as the post hoc test for multiple comparisons. All values are expressed as means ± SE. Statistical significance was defined at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

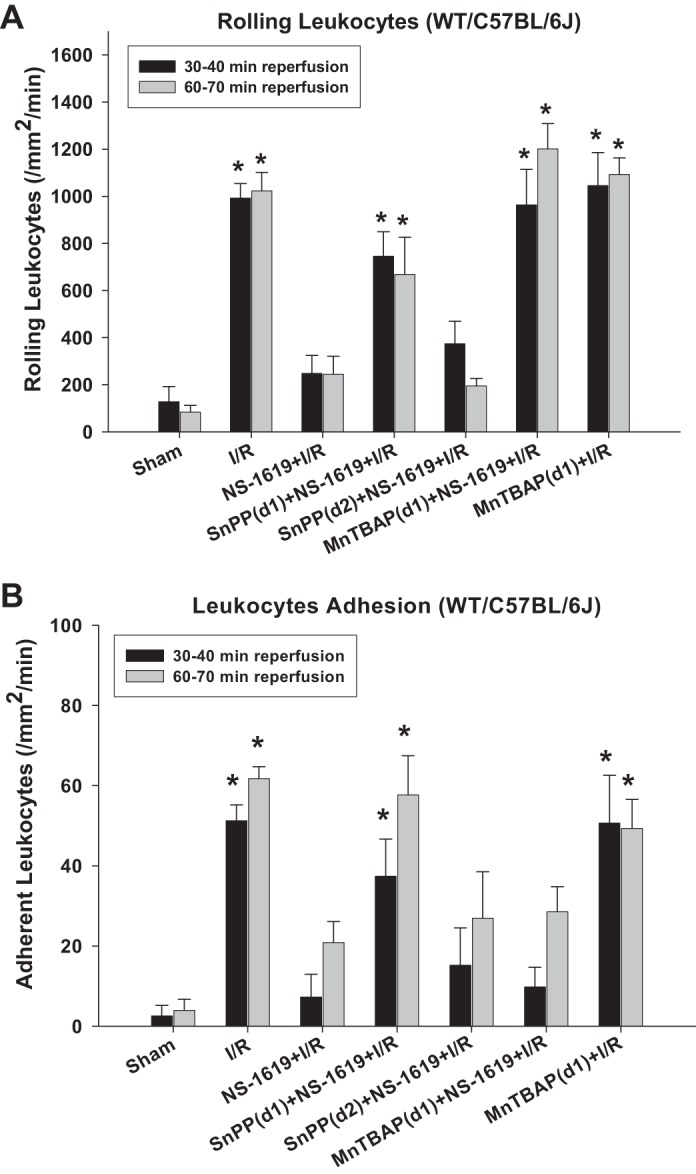

Figure 2 shows the average number of rolling (Fig. 2A) and adherent (Fig. 2B) leukocytes in postcapillary venules of the murine small intestine subjected to I/R alone (I/R, group 2) or after I/R in mice pretreated with the BKCa channel opener NS-1619 either alone (NS-1619 + I/R, group 3) or concomitantly with the HO inhibitor SnPP [SnPP (day 1) + NS-1619 + I/R, group 4] or the cell-permeant SOD mimetic MnTBAP [MnTBAP (day 1) + NS-1619 + I/R, group 6] 24 h earlier compared with nonischemic controls (sham, group 1) and NS-1619-preconditioned mice treated with SnPP just before I/R [SnPP (day 2) + NS-1619 + I/R, group 5]. I/R induced prominent increases in the numbers of rolling and adherent leukocytes compared with sham, proinflammatory effects that were largely prevented by antecedent treatment with NS-1619. SnPP treatment failed to abrogate the antiadhesive effects of antecedent NS-1619 when administered just before I/R [SnPP (day 2) + NS-1619 + I/R] but abolished NS-1619-PC when administered coincidently with BKCa opener 24 h before the induction of I/R [SnPP (day 1) + NS-1619 + I/R]. As shown in Fig. 2A, coadministration of MnTBAP with NS-1619 completely abolished the reductions in postischemic leukocyte rolling induced by NS-1619-PC. However, this SOD mimetic failed to attenuate the effect of NS-1619-PC to prevent I/R-induced leukocyte adhesion (Fig. 2B). Pretreatment with MnTBAP (group 7) did not increase the number of rolling and adhesive leukocytes compared with I/R alone (group 2).

Fig. 2.

Pharmacological inhibition of heme oxygenase (HO)-1 with tin protoporphyrin-IX (SnPP) or treatment with the cell-permeant SOD mimetic Mn(III)tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin (MnTBAP) prevents the antiadhesive effects of preconditioning with NS-1619 in C57BL/6J mice. Effects of ischemia-reperfusion alone (I/R), I/R after pretreatment with the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channel opener NS-1619 (NS-1619 + I/R) 24 h earlier, HO-1 inhibition just before BKCa channel activation [SnPP(d1) + NS-1619 + I/R] or right before the induction of I/R [SnPP (d2) + NS-1619+ I/R], administration of MnTBAP just before BKCa channel activation [MnTBAP(d1) + NS-1619 + I/R], or administration of MnTBAP 24 h before the induction of I/R [MnTBAP(d1) + I/R] on postischemic leukocyte rolling (A) or stationary leukocyte adhesion (B) were tested in wild-type (WT) C57BL/6J mice. Values were determined 30 and 60 min after reperfusion. *Statistically different at P < 0.05 compared with sham or NS-1619 + I/R.

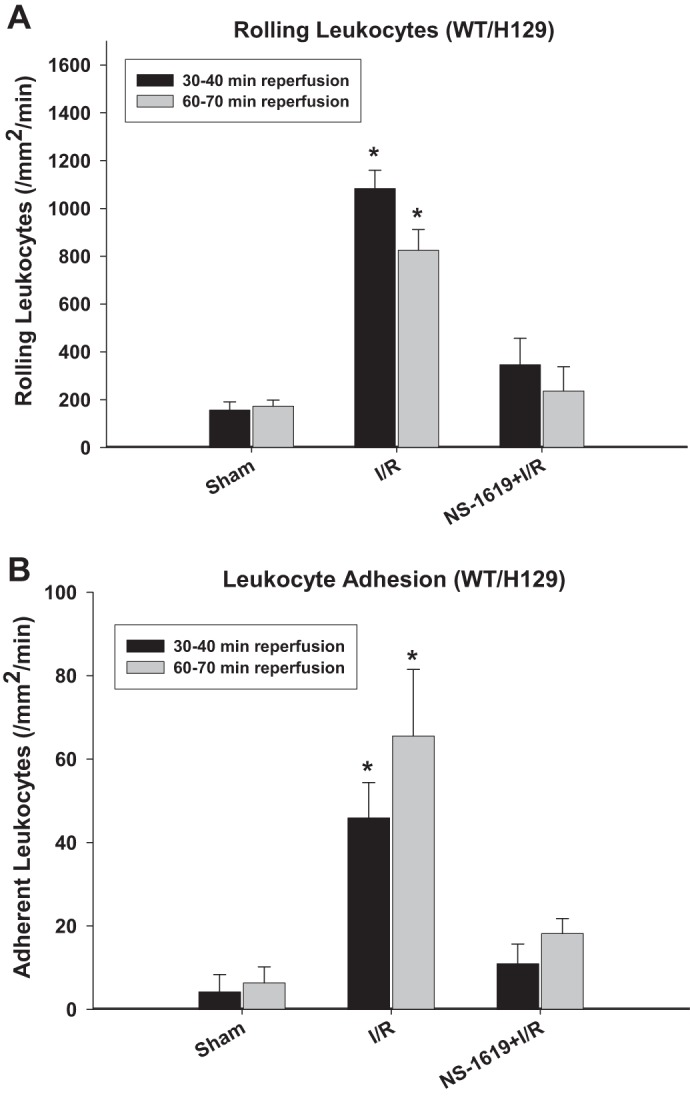

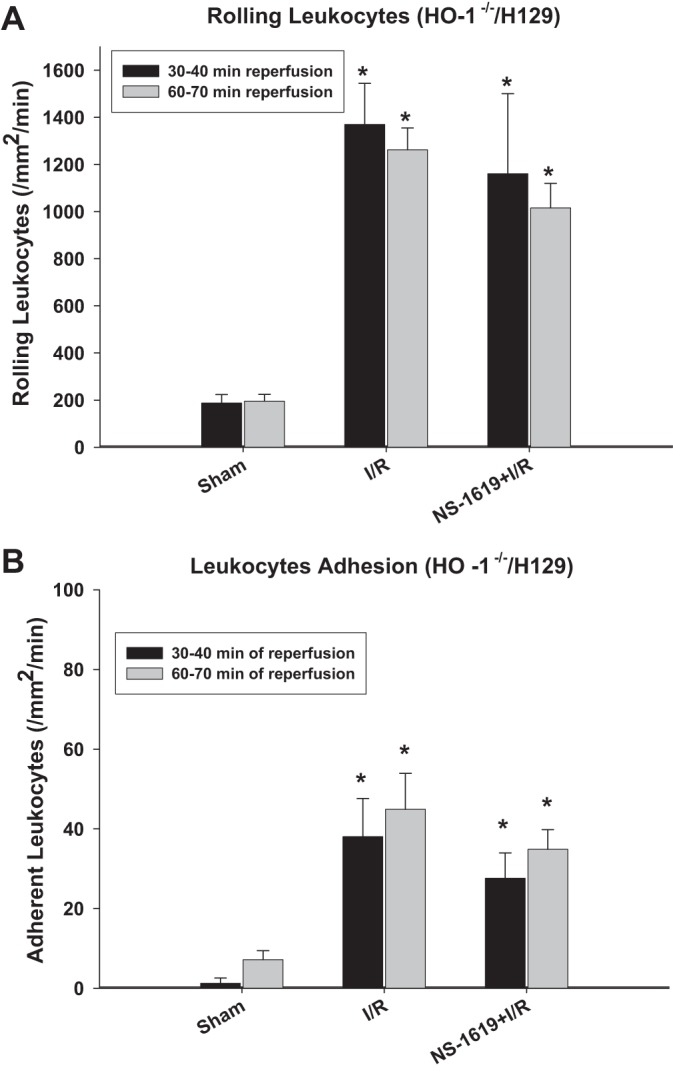

As SnPP has been reported to have effects other than HO inhibition, HO-1-null mice were also used to further evaluate the role of this enzyme in the postischemic antiadhesive effects induced by NS-1619-PC. Comparison of data shown in Figs. 3 and 4 with data shown in Fig. 2 indicated that baseline (nonischemic) leukocyte rolling and adhesion were similar in HO-1−/− mice [group 11: sham (HO-1−/−)], their WT H129 background strain [group 8: sham (HO-1+/+)], and WT C57BL/6J mice (group 1: sham). Except that leukocyte rolling at minutes 60–70 in HO-1−/− mice was slightly higher than that of HO-1+/+ mice, the postischemic increases in leukocyte rolling and adhesion were also similar in these three groups of mice [group 2, I/R only; group 9, I/R only (HO-1+/+); and group 12, I/R only (HO-1−/−)], respectively. Although antecedent treatment with NS-1619 24 h before I/R was equally effective in preventing postischemic leukocyte rolling and adhesion in both WT H129 and C57BL/6J mice (Figs. 2 and 3), pretreatment with this BKCa opener failed to reduce leukocyte rolling and adhesion in HO-1−/− mice [group 13: NS-1619 + I/R (HO-1−/−); Fig. 4].

Fig. 3.

Preconditioning with NS-1619 in heme oxygenase (HO-1)+/+ mice (H129 background). A and B: effects of ishemia-reperfusion (I/R) alone and I/R after pretreatment with the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel opener NS-1619 24 h earlier on postischemic leukocyte rolling (A) and stationary leukocyte adhesion (B) in wild-type (WT) background strain (H129 strain) for HO-1−/− mice. Values were determined 30 and 60 min after reperfusion. *Statistically different at P < 0.05 compared with sham or NS-1619 + I/R.

Fig. 4.

Preconditioning effect of NS-1619 was lost in mice genetically deficient in heme oxygenase-1 (HO-1−/−). A and B: effects of ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) alone and I/R after pretreatment with the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ channel opener NS-1619 on postischemic leukocyte rolling (A) or stationary leukocyte adhesion (B) in HO-1−/− mice. Values were determined 30 and 60 min after the onset of reperfusion. *Statistically different at P < 0.05 compared with sham.

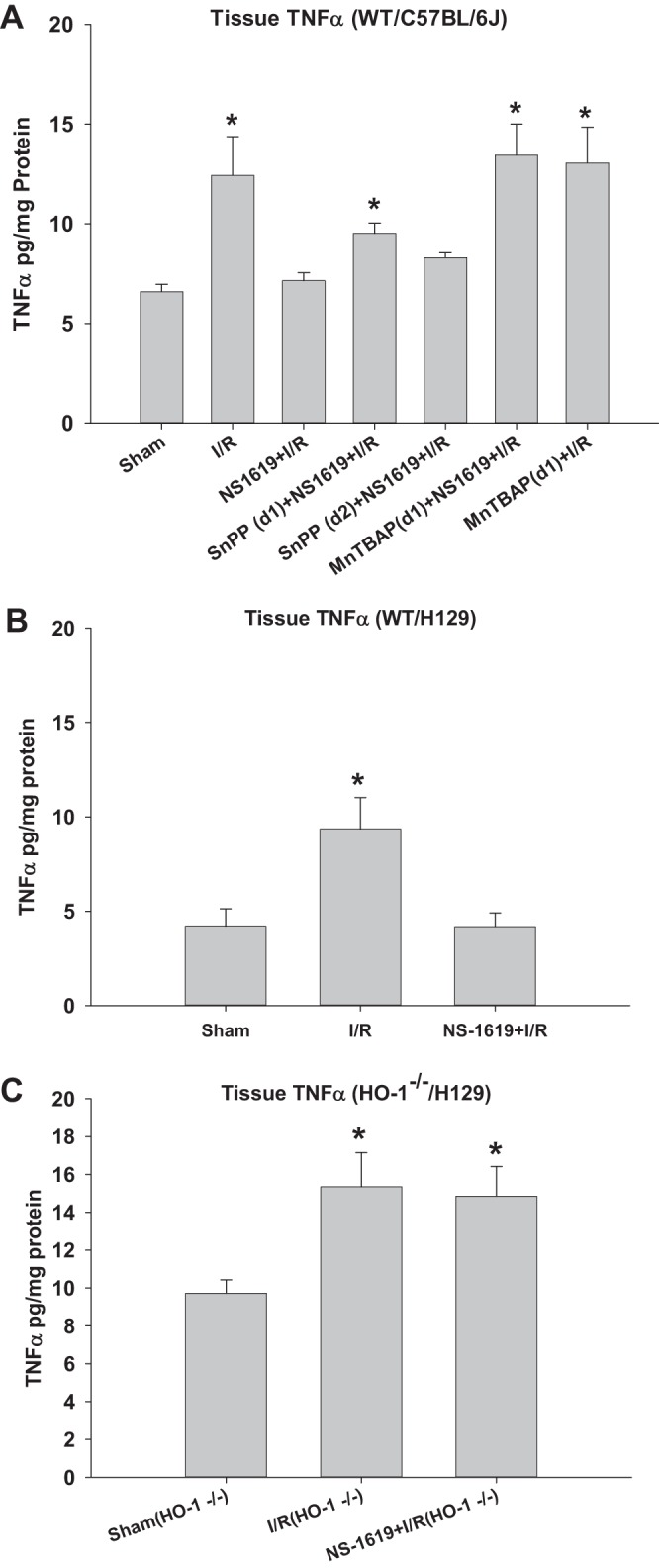

Changes in intestinal (jejunum) TNF-α levels in each treatment group were also measured as a means to further characterize the inflammatory responses to I/R and potential amelioration by NS-1619-PC. In WT C57BL/6J mice (Fig. 5A), I/R was associated with a twofold increase in jejunal TNF-α levels compared with those measured in sham animals. Similar to its effects on postischemic leukocyte rolling and adhesion, NS-1619-PC completely prevented this I/R-induced increase in intestinal TNF-α levels. Concurrent administration of NS-1619 with either SnPP or MnTBAP 24 h before I/R attenuated the reduction in TNF-α release induced by treatment with this BKCa activator alone (Fig. 5A). In WT H129 mice (Fig. 5B), intestinal tissue TNF-α levels in both sham and I/R mice were similar to those of WT C57BL/6J mice, respectively. NS-1619-PC completely reversed I/R-induced TNF-α increase in H129 WT mice. Although baseline (nonischemic/sham) TNF-α levels were higher in HO-1−/− mice (Fig. 5C) compared with WT mice from both strains, I/R induced similar increases in intestinal TNF-α levels in HO-1−/− mice. In stark contrast to the postischemic reductions in intestinal TNF-α induced by NS-1619 in WT mice, preconditioning with this BKCa activator failed to block this inflammatory response in HO-1-deficient mice (Fig. 5C).

Fig. 5.

Preconditioning with NS-1619 prevents postischemic increases in intestinal tissue tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α levels, an effect that was abrogated by coincident administration of tin protoporphyrin-IX (SnPP) or Mn(III)tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin (MnTBAP) in wild-type (WT) C57BL/6J animals and was absent in heme oxygenase (HO)-1-deficient (HO-1−/−) mice. A: effects of ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) alone, I/R after pretreatment with the large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channel opener NS-1619 (NS-1619 + I/R), HO-1 inhibition just before BKCa channel activation [SnPP(d1) + NS-1619 + I/R] or right before the induction of I/R [SnPP(d2) + NS-1619 + I/R], superoxide scavenger MnTBAP administration right before NS-1619 treatment [MnTBAP(d1) + NS-1619 + I/R], or MnTBAP administration 24 h before the induction of I/R [MnTBAP(d1) + I/R] compared with sham on intestinal (jejunum) TNF-α levels of WT C57BL/6J mice. B and C: results obtained from sham, I/R alone, and NS-1619-preconditioned HO-1+/+ and HO-1−/− mice, respectively. *Statistically different at P < 0.05 compared with sham.

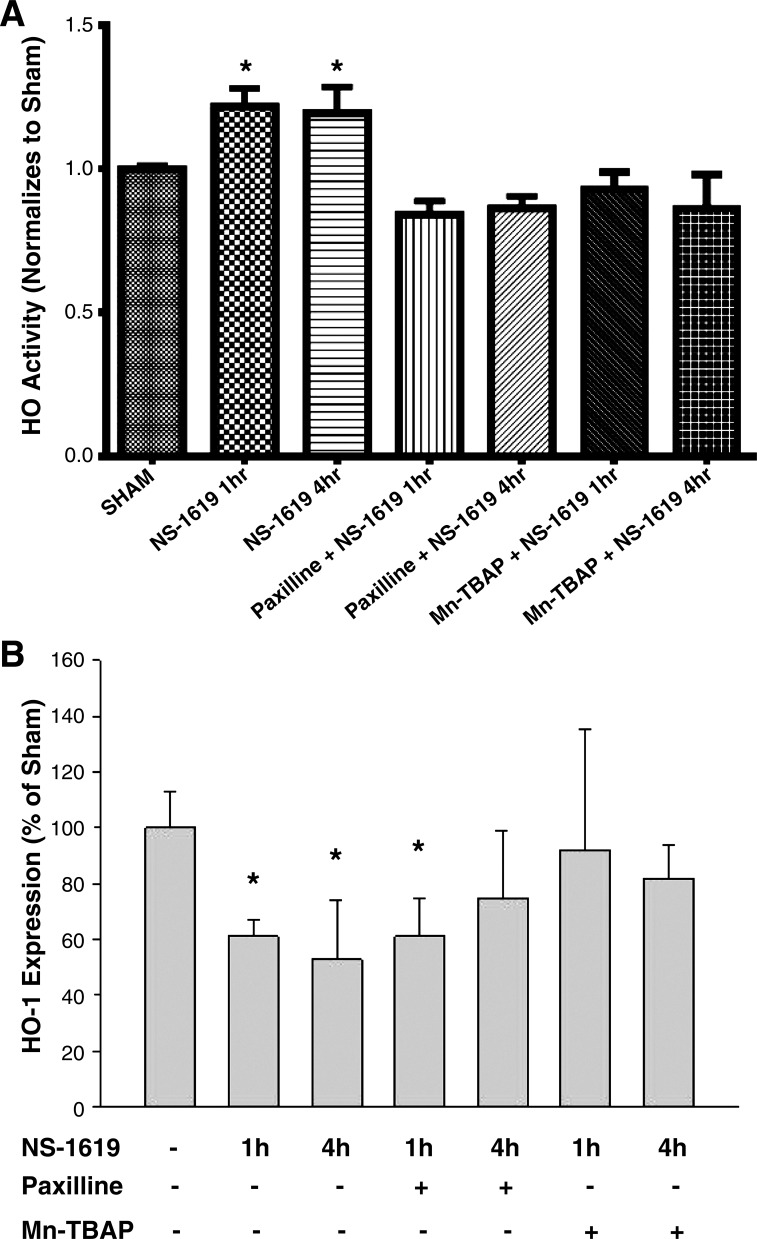

Figure 6 shows the effects of NS-1619 on HO activity (Fig. 6A) and HO-1 expression (Fig. 6B) in samples of the small bowel. The data shown in Fig. 6A indicate that NS-1619 induced a modest increase in intestinal HO activity (by ~20%) when assessed after 1 and 4 h of administration. These NS-1619-induced increases in HO activity were prevented by coincident treatment with paxilline (a BKCa channel inhibitor) or MnTBAP. These data suggest that BKCa channel activation with NS-1619 may increase HO activity via a BKCa- and oxidant-dependent pathway. Surprisingly, NS-1619 treatment produced reductions by 40–50% in intestinal HO-1 protein expression when assessed by Western blot analysis at 1 and 4 h after administration of the BKCa channel activator (Fig. 6B). This NS-1619-induced reduction in HO-1 expression was more short lived in mice treated with the BKCa channel inhibitor paxilline, returning to control levels after 4 h. Treatment with a cell-permeant SOD mimetic (MnTBAP) prevented the reductions in HO-1 expression induced by NS-1619 at both time points.

Fig. 6.

Changes in heme oxygenase (HO) activity (A) and HO-1 expression (B) in the small intestine after NS-1619 treatment. HO activity and HO-1 protein expression in jejunal samples obtained under sham conditions (no treatment) or 1 or 4 h after NS-1619 treatment in the absence (NS-1619 alone) or presence of large-conductance Ca2+-activated K+ (BKCa) channel inhibitor paxilline alone (paxilline + NS-1619) or the cell-permeant SOD mimetic Mn(III)tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin (MnTBAP + NS-1619). Paxilline or MnTBAP was administered 10 min before NS-1619. *P < 0.05 compared with sham.

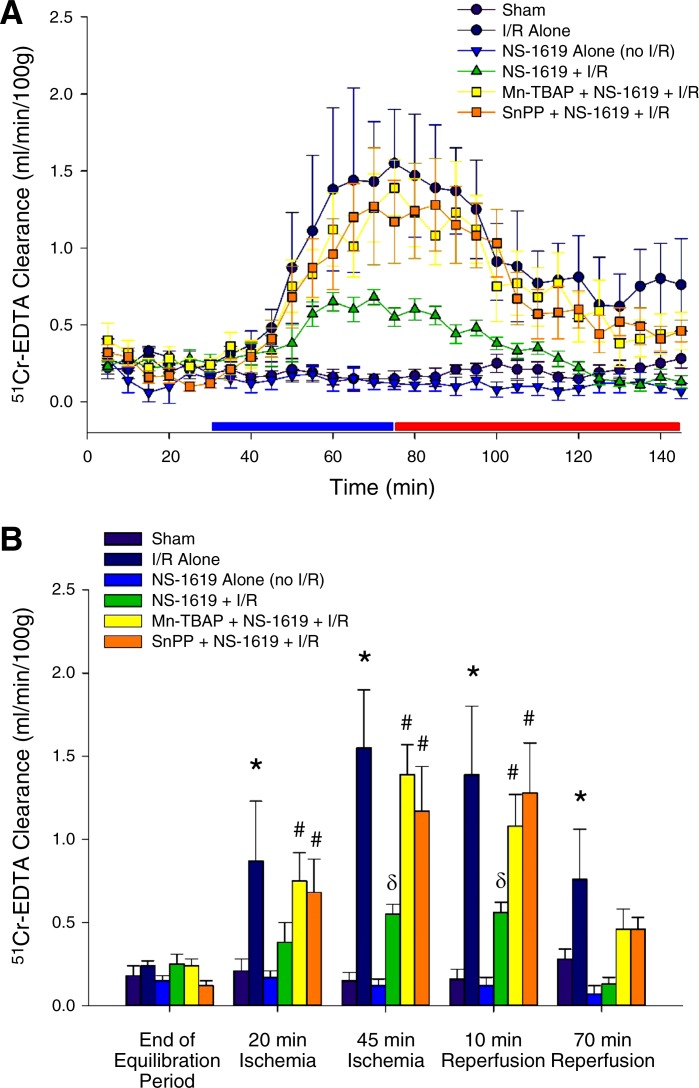

The data shown in Fig. 7A demonstrate the time course for changes in mucosal permeability obtained in groups 14–18, whereas 51Cr-labeled EDTA clearance at selected time points in the protocol are shown in Fig. 7B to depict results of statistical analysis. Time control studies showed that 51Cr-labeled EDTA clearance was low and stable for the duration of the experiments (sham) and that NS-1619 treatment alone (no I/R) had no effect on mucosal permeability. However, 51Cr-labeled EDTA clearance increased progressively during ischemia, an effect that persisted during the first 20 min of reperfusion but was followed by partial restitution of mucosal permeability as reperfusion continued (I/R alone). However, treatment with NS-1619 24 h before I/R (NS-1619 + I/R) markedly reduced the plasma-to-lumen clearance of 51Cr-labeled EDTA during subsequent exposure to I/R. This mucosal permeability-sparing effect of antecedent NS-1619 was prevented by coincident treatment with MnTBAP (MnTBAP + NS-1619 + I/R) or SnPP (SnPP + NS-1619 + I/R). These results indicate that NS-1619 preserves mucosal function by an oxidant- and HO-dependent mechanism.

Fig. 7.

Antecedent NS-1619 prevents mucosal barrier disruption induced by ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) 24 h later. A: time course of epithelial permeability changes, as measured by 51Cr-labeled EDTA clearance from plasma to jejunal lumen under control (no ischemia) conditions and after I/R alone or treatment with NS-1619 alone or in combination with tin protoporphyrin-IX (SnPP) or Mn(III)tetrakis (4-benzoic acid) porphyrin (MnTBAP) 24 h before I/R. The blue and red bars just above the x-axis timeline denote the ischemic and reperfusion periods, respectively. To depict important results of our statistical analysis that would have been obscured by the presentation of the complete time course data shown in A, B shows results of this analysis for data obtained at the end of the 30-min equilibration period before the onset of ischemia compared with data acquired after 20 and 45 min of ischemia and after 10 and 70 min of reperfusion. *Statistically different at P < 0.05 compared with sham; #statistically different at P < 0.05 compared with sham but not different from I/R; δstatistically different at P < 0.05 compared with sham and I/R.

DISCUSSION

BKCa channel activators such as NS-1619 have been shown to elicit delayed acquisition of tolerance to I/R (17, 18, 26, 40, 59, 66, 70). However, in stark contrast to most pharmacological preconditioning agents, which trigger the appearance of protected states by activation of endothelial NOS, opening BKCa channels with NS-1619 induces preconditioning by a mechanism that is independent of the NO-producing enzyme (66). Interestingly, coincident treatment with oxidant scavengers completely abolishes NS-1619-induced protection against myocardial and neuronal injury (17, 18, 47, 59). These results suggest that NS-1619-induced entrance into a preconditioned state is triggered or initiated by the formation of ROS. However, little is known regarding other downstream mediators of NS-1619-PC. Thus, the major aim of our study was to further explore the mechanisms whereby NS-1619 preconditioning protects against I/R-induced inflammatory effects and disrupts mucosal function. Our results not only confirm the essential role of oxidants in the triggering mechanism for NS-1619-induced protection but also demonstrate, for the first time, that HO-1 plays an obligatory role in the postischemic anti-inflammatory effects of this BKCa channel activator. Moreover, we provided evidence in support of the concept that NS-1619 increases HO-1 activity by an oxidant-dependent mechanism. We also present new evidence that in addition to the anti-inflammatory effects of NS-1619 in the microcirculation, treatment with this BKCa activator also protects the mucosal barrier from disruption during I/R, a result consistent with our previous demonstration that NS-1619 preconditioning preserved mitochondrial function in postischemic enterocytes (40).

BKCa channels are expressed on the plasma membrane of a number of cell types including endothelial cells and vascular smooth muscle cells and can be activated by intracellular Ca2+ elevation or membrane depolarization (3, 4, 6, 13, 21, 57, 61). More recent work has demonstrated the presence of BKCa channel subunits on the inner mitochondrial membrane (mitoBKCa) of cardiac myocytes (3, 57, 61, 70), a glioma cell line (56), an immortalized human endothelial cell line (5), and the brain (10). With regard to the small intestine, we have shown that mucosal enterocytes also express BKCa channels, but not in their mitochondria (40). We have also presented evidence supporting the view that microvascular, but not large artery or vein, endothelial cells express BKCa channels (76). The latter is important in view of the controversy regarding expression of these K+ channels in native endothelial cells. This debate arose from the observation that cultured microvascular and macrovascular endothelial cells express BKCa while freshly isolated large artery endothelium does not (52). With respect to vascular function, BKCa channels play an important role in modulating vasodilator responses to many vasodilator substances (27, 41, 48). In addition, activation of BKCa channels plays an important role in the anti-inflammatory and infarct-sparing effects of preconditioning with ethanol, H2S, or short bouts of ischemia (55, 65, 76). Importantly, we and others have shown that the ability of the BKCa activator NS-1619 to induce delayed acquisition of tolerance was abolished by lipophilic BKCa channel blocker paxilline, an observation that supports the specific action of NS-1619 on BKCa to induce preconditioning (40, 76).

We hypothesized that HO-1 might serve as a mediator in NS-1619-PC for the following reasons. First, upregulation of HO-1 suppresses P-selectin expression and leukocyte adhesion induced by hydrogen peroxide or I/R in the small intestine, inflammatory processes that are also attenuated by NS-1619-PC (25, 35, 63, 64). Second, the expression of HO-1 is particularly rich in postcapillary venules of the small intestine (25). Third, the induction of HO-1 expression by hemin limits infarct size in the setting of myocardial ischemia and postischemic inflammation in the small intestine (24, 77), while inhibition of HO-1 either pharmacologically or through siRNA approaches can inhibit the infarct-sparing effects of ischemic preconditioning in myocardial I/R (29). Fourth, work in our laboratory demonstrated that HO-1 plays an essential role in mediating the antiadhesive effects of AMPK- (14, 15) and H2S-induced (77) preconditioning in a murine model of intestinal I/R injury. To address this postulate, mice were treated with HO inhibitor SnPP just before administration of NS-1619 or immediately before I/R to determine whether this heme-degrading enzyme participated as a trigger versus a mediator, respectively, of NS-1619-PC. As shown in Figs. 2, 5, and 7, concurrent administration of the HO inhibitor SnPP with NS-1619 24 h before I/R abrogated the postischemic anti-inflammatory effects (reduced TNF-α release and decreased leukocyte rolling and adhesion in postcapillary venules) and mucosal permeability-sparing actions that are normally induced by treatment with this BKCa channel activator. Interestingly, NS-1619 remained effective as an anti-inflammatory preconditioning stimulus in experiments where SnPP was administered just before I/R. This latter finding was surprising to us in light of our earlier work with an AMPK activator or H2S, which induce preconditioning by a BKCa-dependent mechanism, because HO-1 inhibitor administration just before I/R effectively prevented the anti-inflammatory effects of these stimuli (15, 39, 40, 77). Taken together, our data suggest that HO-1 plays an important role as an early signaling event after BKCa channel activation with NS-1619 but does not serve as the effector of its anti-inflammatory actions during I/R 24 h later. On the other hand, AMPK activation- and H2S-induced BKCa channel activation appears to be associated with enhanced HO-1 expression and activity during reperfusion; HO-1 then serves a mediator or effector role via formation of its antiadhesive and antioxidant products (15, 39, 40, 77).

Although SnPP is commonly used as an inhibitor of HO activity, off-target effects unrelated to HO-1 have been reported (21, 42, 60, 68, 69, 75). In addition, use of this metalloporphyrin inhibitor of HO activity does not facilitate identification of the isoform responsible for its anti-inflammatory actions. To address the aforementioned issues, we used mice that were genetically deficient in their expression of HO-1 (HO-1−/−) to verify our pharmacological results and gain insight as to the isoform involved. As indicated by the data shown in Fig. 4, HO-1−/− mice exhibited comparable numbers of rolling and adherent leukocytes under control (sham) conditions compared with their WT counterparts (Figs. 2 and 3, respectively). Comparison of results shown in Figs. 2–4 also indicates that I/R induced similar increments in leukocyte rolling and adhesion in HO-1-deficient and WT mice. However, in contrast to WT mice, antecedent NS-1619 treatment failed to prevent postischemic leukocyte rolling and adhesion in mice genetically deficient in HO-1 protein. A similar pattern of response was noted with regard to I/R-induced expression of the inflammatory cytokine TNF-α in jejunal tissue samples (Fig. 5). These findings further support a role for HO-1 as a critical signaling element in the development of an anti-inflammatory phenotype evoked by antecedent NS-1619 treatment. It is of interest to note that HO-1-derived CO can activate BKCa channels (51), suggesting the possibility for a positive feedback loop to enhance the anti-inflammatory and mucosal permeability-sparing actions of NS-1619.

Another noteworthy finding is that both baseline and postischemic tissue TNF-α levels were higher in HO-1 knockout animals compared with WT mice (Fig. 5), despite similarities in the numbers of rolling and adherent leukocytes under control conditions and after I/R in these animals (Figs. 2–4). Although these data suggest that TNF-α might serve as a useful proinflammatory marker, our data could be interpreted to suggest that the cytokine may not be a direct cause of inflammation in postischemic intestine. However, this proposal is not supported by the observations that TNF immunoneutralization or inhibition prevents postischemic leukocyte adhesion, phagocyte infiltration, and tissue injury in the small intestine (1, 20, 50, 74), suggesting a cause-and-effect relationship. Similarly, mice deficient in TNF-α receptor 1 also demonstrated marked reductions in P-selectin, E-selectin, VCAM and ICAM-1 expression, intestinal neutrophil infiltration, and apoptosis after splanchnic I/R compared with WT counterparts (11). Because baseline leukocyte rolling and adhesion were similar in WT and HO-1 knockout mice, despite the near doubling of TNF-α levels in HO-1-deficient mice, we interpret these findings to suggest that compensatory alterations in gene expression of anti-inflammatory molecules may limit the effect of this elevation in levels of this cytokine in these mice. Clearly, much additional work will be required to understand how HO-1-deficient mice resist the effects of elevated TNF-α under baseline conditions.

Although well known for their destructive effects, it is now apparent that ROS can function as intracellular signaling molecules. Indeed, not only do oxidants such as superoxide play a major role in the generation of inflammatory mediators and contribute to cell dysfunction and death in I/R, but also they have been implicated as triggers for the development of preconditioned states induced by short bouts of ischemia or ethanol ingestion that prevent postischemic tissue injury (22, 36, 72). Furthermore, it has been demonstrated that coadministration of NS-1619 with ROS scavengers abolishes both immediate and delayed preconditioning elicited by NS-1619 in neuronal cells (17, 18). In a subsequent study, NS-1619 was shown to enhance the generation of ROS in cultured brain slices (26). In addition, Stowe et al. (59) have demonstrated that NS-1619 can trigger mitochondrial ROS generation in cardiac myocytes and that coincident ROS scavenging almost completely abrogates NS-1619-induced cardioprotection.

In light of these findings, we determined whether coincident treatment with MnTBAP, a cell-permeant SOD mimetic, would prevent NS-1619-PC in the small bowel (Figs. 2, 5, and 7). Our results indicated that coincident administration of MnTBAP with NS-1619 was as effective as concomitant HO inhibition in abrogating the effects of NS-1619 to prevent postischemic leukocyte rolling (Fig. 2) and increased mucosal permeability, TNF-α release (Fig. 5), and mucosal barrier disruption (Fig. 7). However, combined treatment with MnTBAP and NS-1619 failed to limit the protection afforded by this BKCa channel activator against increased leukocyte adhesion induced by I/R 24 h later. These results suggest that the ability of NS-1619-PC to prevent postischemic leukocyte rolling was triggered by ROS generation but the abrogation of leukocyte adhesion occurs by an oxidant-independent mechanism. We have reported a similar dissociation of effects of preconditioning with the AMPK activator 5-aminoimidazole-4-carboxamide-1-β-d-ribofuranoside (AICAR) on leukocyte rolling and adhesion in evaluating the role of eNOS in its anti-inflammatory effects (16). In this study, AICAR preconditioning was shown to almost completely prevent postischemic leukocyte rolling and adhesion. Although the ability of AICAR administration 24 h before I/R to limit postischemic leukocyte rolling was almost completely absent in eNOS−/− mice or WT animals treated with a NOS inhibitor [N5-(1-iminoethyl)-l-ornithine (l-NIO)], AICAR-induced abrogation of stationary leukocyte adhesion remained effective in both WT mice treated with l-NIO and in eNOS-deficient animals. On the basis of these findings, we proposed that AICAR-induced NO formation may selectively target the signaling mechanisms involved in the expression of adhesion molecules that mediate leukocyte rolling (e.g., P-selectin) but not adhesion (e.g., ICAM-1) (16, 58). A similar explanation may pertain to disparate roles for ROS in abrogating NS-1619-induced leukocyte rolling versus stationary adhesion.

Since HO-1 can be upregulated by oxidative stress (67) and our results indicate that the development of NS-1619-PC is dependent on both ROS and HO-1, we hypothesized that these signaling events may be mechanistically linked. To address this postulate, we tested whether NS-1619 would increase HO-1 expression and activity in the small bowel and whether this enhanced activity was dependent on ROS production. As shown in Fig. 6, NS-1619 increased HO activity in intestinal tissue, an effect that was attenuated by coincident treatment with the SOD mimetic MnTBAP. To our surprise and in contrast to the effect of NS-1619 to increase HO activity, treatment with this BKCa channel activator reduced the expression of HO-1 protein in intestinal tissue, an effect that was also prevented by MnTBAP. Thus, data shown in Fig. 6 indicate that NS-1619 reduces the expression of HO-1 in gut tissue but the activity of remaining HO is increased. This is not likely due to a compensatory alteration in HO-2 activity, given the failure of NS-1619 to invoke preconditioning in SnPP-treated mice or in HO-1 knockout mice. The data shown in Fig. 6 point to the importance of measuring HO activity versus enzyme expression (or mRNA levels) in assessing a role for the enzyme. These results suggest NS-1619-induced ROS signaling serves as a proximal stimulus for downstream upregulation of HO-1 activity.

Although our results provide important new information regarding the roles of ROS and HO-1 as triggers to instigate the development of an anti-inflammatory and mucosal-sparing phenotype in response to NS-1619-PC, identification of the signaling elements that serve as effectors to mediate reduced TNF-α release and decreased leukocyte rolling and adhesion during I/R 24 h later remains unclear. However, our study does exclude a role for HO-1 as an end effector during I/R 24 h after NS-1619 administration. We have not yet evaluated the potential role of eNOS, iNOS, or KATP channels, which have been implicated as end effectors in other forms of preconditioning models. However, work conducted in the heart excludes roles for these potential effectors as postischemic mediators of NS-1619-PC (7, 66). Data presented in other studies conducted in the heart indicate that NS-1619-PC may prevent postischemic myocardial injury by opening the mitochondrial permeability transition pore and preventing mitochondrial calcium overload (7). In addition to the aforementioned potential end-effector targets, it is tempting to speculate that enzymes such as cytochrome P-450 epoxygenase, cystathionine β-synthase/cystathionine γ-lyase, or 5′-nucleotidase, upregulated by NS-1619 24 h after treatment, may participate as final mediators during subsequent I/R, because the products of their catalytic activity (epoxyeicosatrienoic acids, H2S, and adenosine, respectively) are all anti-inflammatory, acting to prevent leukocyte/endothelial cell adhesive interactions, and have been implicated in other forms of preconditioning (19, 62, 76). Clearly, much additional work will be required to address these intriguing possibilities.

In summary, the results of our study demonstrate that NS-1619, a BKCa channel opener, instigates the development of late-phase preconditioning that limits postischemic TNF-α release, reduces the number of rolling and firmly adherent leukocytes, and prevents mucosal barrier disruption during I/R. These anti-inflammatory and mucosal permeability-sparing effects induced by antecedent NS-1619 in I/R appear to be triggered by ROS-dependent increases in HO-1 activity.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

R.J.K. conceived and designed research; H.D., M.W., P.N.P., and T.K. performed experiments; H.D., M.W., Y.L., W.D., and R.J.K. analyzed data; H.D., M.W., P.N.P., T.K., W.D., and R.J.K. interpreted results of experiments; H.D., M.W., and T.K. prepared figures; H.D., Y.L., W.D., and R.J.K. drafted manuscript; H.D., M.W., and R.J.K. edited and revised manuscript; H.D., M.W., P.N.P., T.K., Y.L., W.D., and R.J.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants AA-022108, HL-095486, and HL-59976.

REFERENCES

- 1.Akdogan RA, Kalkan Y, Tumkaya L, Alacam H, Erdivanli B, Aydin İ. Influence of infliximab pretreatment on ischemia/reperfusion injury in rat intestine. Folia Histochem Cytobiol 52: 36–41, 2014. doi: 10.5603/FHC.2014.0004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alam J, Cook JL. How many transcription factors does it take to turn on the heme oxygenase-1 gene? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 36: 166–174, 2007. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2006-0340TR. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Balderas E, Zhang J, Stefani E, Toro L. Mitochondrial BKCa channel. Front Physiol 6: 104, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2015.00104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barrett JN, Magleby KL, Pallotta BS. Properties of single calcium-activated potassium channels in cultured rat muscle. J Physiol 331: 211–230, 1982. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.1982.sp014370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bednarczyk P, Koziel A, Jarmuszkiewicz W, Szewczyk A. Large-conductance Ca2+-activated potassium channel in mitochondria of endothelial EA.hy926 cells. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 304: H1415–H1427, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00976.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Burnette JO, White RE. PGI2 opens potassium channels in retinal pericytes by cyclic AMP-stimulated, cross-activation of PKG. Exp Eye Res 83: 1359–1365, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.exer.2006.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cao CM, Xia Q, Gao Q, Chen M, Wong TM. Calcium-activated potassium channel triggers cardioprotection of ischemic preconditioning. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 312: 644–650, 2005. doi: 10.1124/jpet.104.074476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choi AM, Alam J. Heme oxygenase-1: function, regulation, and implication of a novel stress-inducible protein in oxidant-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol 15: 9–19, 1996. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb.15.1.8679227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cohen MV, Baines CP, Downey JM. Ischemic preconditioning: from adenosine receptor to KATP channel. Annu Rev Physiol 62: 79–109, 2000. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.62.1.79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Douglas RM, Lai JC, Bian S, Cummins L, Moczydlowski E, Haddad GG. The calcium-sensitive large-conductance potassium channel (BK/MAXI K) is present in the inner mitochondrial membrane of rat brain. Neuroscience 139: 1249–1261, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2006.01.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Esposito E, Mazzon E, Muià C, Meli R, Sessa E, Cuzzocrea S. Splanchnic ischemia and reperfusion injury is reduced by genetic or pharmacological inhibition of TNF-alpha. J Leukoc Biol 81: 1032–1043, 2007. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0706480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fryer RM, Hsu AK, Eells JT, Nagase H, Gross GJ. Opioid-induced second window of cardioprotection: potential role of mitochondrial KATP channels. Circ Res 84: 846–851, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.84.7.846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gárdos G. The function of calcium in the potassium permeability of human erythrocytes. Biochim Biophys Acta 30: 653–654, 1958. doi: 10.1016/0006-3002(58)90124-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Garlid KD, Paucek P, Yarov-Yarovoy V, Murray HN, Darbenzio RB, D’Alonzo AJ, Lodge NJ, Smith MA, Grover GJ. Cardioprotective effect of diazoxide and its interaction with mitochondrial ATP-sensitive K+ channels. Possible mechanism of cardioprotection. Circ Res 81: 1072–1082, 1997. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.81.6.1072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaskin FS, Kamada K, Yusof M, Durante W, Gross G, Korthuis RJ. AICAR preconditioning prevents postischemic leukocyte rolling and adhesion: role of KATP channels and heme oxygenase. Microcirculation 16: 167–176, 2009. doi: 10.1080/10739680802355897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaskin FS, Kamada K, Yusof M, Korthuis RJ. 5′-AMP-activated protein kinase activation prevents postischemic leukocyte-endothelial cell adhesive interactions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H326–H332, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00744.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gáspár T, Domoki F, Lenti L, Katakam PV, Snipes JA, Bari F, Busija DW. Immediate neuronal preconditioning by NS1619. Brain Res 1285: 196–207, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2009.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gáspár T, Katakam P, Snipes JA, Kis B, Domoki F, Bari F, Busija DW. Delayed neuronal preconditioning by NS1619 is independent of calcium activated potassium channels. J Neurochem 105: 1115–1128, 2008. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.05210.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gauthier KM, Yang W, Gross GJ, Campbell WB. Roles of epoxyeicosatrienoic acids in vascular regulation and cardiac preconditioning. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol 50: 601–608, 2007. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0b013e318159cbe3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gerlach UA, Atanasov G, Wallenta L, Polenz D, Reutzel-Selke A, Kloepfel M, Jurisch A, Marksteiner M, Loddenkemper C, Neuhaus P, Sawitzki B, Pascher A. Short-term TNF-alpha inhibition reduces short-term and long-term inflammatory changes post-ischemia/reperfusion in rat intestinal transplantation. Transplantation 97: 732–739, 2014. doi: 10.1097/TP.0000000000000032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ghatta S, Nimmagadda D, Xu X, O’Rourke ST. Large-conductance, calcium-activated potassium channels: structural and functional implications. Pharmacol Ther 110: 103–116, 2006. doi: 10.1016/j.pharmthera.2005.10.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Granger DN, Korthuis RJ. Physiologic mechanisms of postischemic tissue injury. Annu Rev Physiol 57: 311–332, 1995. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.57.030195.001523. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gross GJ. The role of mitochondrial KATP channels in cardioprotection. Basic Res Cardiol 95: 280–284, 2000. doi: 10.1007/s003950050004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hangaishi M, Ishizaka N, Aizawa T, Kurihara Y, Taguchi J, Nagai R, Kimura S, Ohno M. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 can act protectively against cardiac ischemia/reperfusion in vivo. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 279: 582–588, 2000. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2000.3973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hayashi S, Takamiya R, Yamaguchi T, Matsumoto K, Tojo SJ, Tamatani T, Kitajima M, Makino N, Ishimura Y, Suematsu M. Induction of heme oxygenase-1 suppresses venular leukocyte adhesion elicited by oxidative stress: role of bilirubin generated by the enzyme. Circ Res 85: 663–671, 1999. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.85.8.663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heinen A, Camara AK, Aldakkak M, Rhodes SS, Riess ML, Stowe DF. Mitochondrial Ca2+-induced K+ influx increases respiration and enhances ROS production while maintaining membrane potential. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 292: C148–C156, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00215.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hu Y, Yang G, Xiao X, Liu L, Li T. Bkca opener, NS1619 pretreatment protects against shock-induced vascular hyporeactivity through PDZ-Rho GEF-RhoA-Rho kinase pathway in rats. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 76: 394–401, 2014. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182aa2d98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ito K, Ozasa H, Kojima N, Miura M, Iwai T, Senoo H, Horikawa S. Pharmacological preconditioning protects lung injury induced by intestinal ischemia/reperfusion in rat. Shock 19: 462–468, 2003. doi: 10.1097/01.shk.0000055240.25446.16. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jancsó G, Cserepes B, Gasz B, Benkó L, Borsiczky B, Ferenc A, Kürthy M, Rácz B, Lantos J, Gál J, Arató E, Sínayc L, Wéber G, Róth E. Expression and protective role of heme oxygenase-1 in delayed myocardial preconditioning. Ann N Y Acad Sci 1095: 251–261, 2007. doi: 10.1196/annals.1397.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jin C, Wu J, Watanabe M, Okada T, Iesaki T. Mitochondrial K+ channels are involved in ischemic postconditioning in rat hearts. J Physiol Sci 62: 325–332, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s12576-012-0206-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kalogeris T, Baines CP, Krenz M, Korthuis RJ. Ischemia/reperfusion. Compr Physiol 7: 113–170, 2016. doi: 10.1002/cphy.c160006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kamada K, Gaskin FS, Yamaguchi T, Carter P, Yoshikawa T, Yusof M, Korthuis RJ. Role of calcitonin gene-related peptide in the postischemic anti-inflammatory effects of antecedent ethanol ingestion. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H531–H537, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00839.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kanwar S, Hickey MJ, Kubes P. Postischemic inflammation: a role for mast cells in intestine but not in skeletal muscle. Am J Physiol Gastro Liver Physiol 275: G212–G218, 1998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Katori M, Anselmo DM, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. A novel strategy against ischemia and reperfusion injury: cytoprotection with heme oxygenase system. Transpl Immunol 9: 227–233, 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0966-3274(02)00043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Katori M, Busuttil RW, Kupiec-Weglinski JW. Heme oxygenase-1 system in organ transplantation. Transplantation 74: 905–912, 2002. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200210150-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim J, Jang HS, Park KM. Reactive oxygen species generated by renal ischemia and reperfusion trigger protection against subsequent renal ischemia and reperfusion injury in mice. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 298: F158–F166, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00474.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Komatsu S, Grisham MB, Russell JM, Granger DN. Enhanced mucosal permeability and nitric oxide synthase activity in jejunum of mast cell deficient mice. Gut 41: 636–641, 1997. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.5.636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Krenz M, Baines C, Kalogeris T, Korthuis RJ. Cell Survival Programs and Ischemia/Reperfusion: Hormesis, Preconditioning, and Cardioprotection. San Rafael, CA: Morgan & Claypool Life Sciences, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liu XM, Peyton KJ, Shebib AR, Wang H, Korthuis RJ, Durante W. Activation of AMPK stimulates heme oxygenase-1 gene expression and human endothelial cell survival. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 300: H84–H93, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00749.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Liu Y, Kalogeris T, Wang M, Zuidema MY, Wang Q, Dai H, Davis MJ, Hill MA, Korthuis RJ. Hydrogen sulfide preconditioning or neutrophil depletion attenuates ischemia-reperfusion-induced mitochondrial dysfunction in rat small intestine. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 302: G44–G54, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00413.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lu T, Katakam PV, VanRollins M, Weintraub NL, Spector AA, Lee HC. Dihydroxyeicosatrienoic acids are potent activators of Ca2+-activated K+ channels in isolated rat coronary arterial myocytes. J Physiol 534: 651–667, 2001. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.2001.t01-1-00651.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Łukasiak A, Skup A, Chlopicki S, Łomnicka M, Kaczara P, Proniewski B, Szewczyk A, Wrzosek A. SERCA, complex I of the respiratory chain and ATP-synthase inhibition are involved in pleiotropic effects of NS1619 on endothelial cells. Eur J Pharmacol 786: 137–147, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.05.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maines MD. The heme oxygenase system: a regulator of second messenger gases. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 37: 517–554, 1997. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pharmtox.37.1.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Maines MD, Gibbs PE. 30 some years of heme oxygenase: from a “molecular wrecking ball” to a “mesmerizing” trigger of cellular events. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 338: 568–577, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mallick IH, Winslet MC, Seifalian AM. Ischemic preconditioning of small bowel mitigates the late phase of reperfusion injury: heme oxygenase mediates cytoprotection. Am J Surg 199: 223–231, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Moens AL, Claeys MJ, Timmermans JP, Vrints CJ. Myocardial ischemia/reperfusion-injury, a clinical view on a complex pathophysiological process. Int J Cardiol 100: 179–190, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2004.04.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Murry CE, Jennings RB, Reimer KA. Preconditioning with ischemia: a delay of lethal cell injury in ischemic myocardium. Circulation 74: 1124–1136, 1986. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.74.5.1124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Nagaoka T, Hein TW, Yoshida A, Kuo L. Resveratrol, a component of red wine, elicits dilation of isolated porcine retinal arterioles: role of nitric oxide and potassium channels. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 48: 4232–4239, 2007. doi: 10.1167/iovs.07-0094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pain T, Yang XM, Critz SD, Yue Y, Nakano A, Liu GS, Heusch G, Cohen MV, Downey JM. Opening of mitochondrial KATP channels triggers the preconditioned state by generating free radicals. Circ Res 87: 460–466, 2000. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.87.6.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pergel A, Kanter M, Yucel AF, Aydin I, Erboga M, Guzel A. Anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects of infliximab in a rat model of intestinal ischemia/reperfusion injury. Toxicol Ind Health 28: 923–932, 2012. doi: 10.1177/0748233711427056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Riddle MA, Walker BR. Regulation of endothelial BK channels by heme oxygenase-derived carbon monoxide and caveolin-1. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 303: C92–C101, 2012. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00356.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sandow SL, Grayson TH. Limits of isolation and culture: intact vascular endothelium and BKCa. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 297: H1–H7, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00042.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Schultz JE, Rose E, Yao Z, Gross GJ. Evidence for involvement of opioid receptors in ischemic preconditioning in rat hearts. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 268: H2157–H2161, 1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Scorziello A, Santillo M, Adornetto A, Dell’aversano C, Sirabella R, Damiano S, Canzoniero LM, Renzo GF, Annunziato L. NO-induced neuroprotection in ischemic preconditioning stimulates mitochondrial Mn-SOD activity and expression via Ras/ERK1/2 pathway. J Neurochem 103: 1472–1480, 2007. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04845.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shintani Y, Node K, Asanuma H, Sanada S, Takashima S, Asano Y, Liao Y, Fujita M, Hirata A, Shinozaki Y, Fukushima T, Nagamachi Y, Okuda H, Kim J, Tomoike H, Hori M, Kitakaze M. Opening of Ca2+-activated K+ channels is involved in ischemic preconditioning in canine hearts. J Mol Cell Cardiol 37: 1213–1218, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.yjmcc.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Siemen D, Loupatatzis C, Borecky J, Gulbins E, Lang F. Ca2+-activated K channel of the BK-type in the inner mitochondrial membrane of a human glioma cell line. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 257: 549–554, 1999. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Singh H, Lu R, Bopassa JC, Meredith AL, Stefani E, Toro L. MitoBKCa is encoded by the Kcnma1 gene, and a splicing sequence defines its mitochondrial location. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 10836–10841, 2013. [Erratum. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 110: 18024, 2013. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1316210110.] doi:. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Smith CW. Endothelial adhesion molecules and their role in inflammation. Can J Physiol Pharmacol 71: 76–87, 1993. doi: 10.1139/y93-012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Stowe DF, Aldakkak M, Camara AK, Riess ML, Heinen A, Varadarajan SG, Jiang MT. Cardiac mitochondrial preconditioning by Big Ca2+-sensitive K+ channel opening requires superoxide radical generation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 290: H434–H440, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00763.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Szewczyk A, Jarmuszkiewicz W, Koziel A, Sobieraj I, Nobik W, Lukasiak A, Skup A, Bednarczyk P, Drabarek B, Dymkowska D, Wrzosek A, Zablocki K. Mitochondrial mechanisms of endothelial dysfunction. Pharmacol Rep 67: 704–710, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.pharep.2015.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Toro L, Li M, Zhang Z, Singh H, Wu Y, Stefani E. MaxiK channel and cell signalling. Pflugers Arch 466: 875–886, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s00424-013-1359-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tsuchida A, Miura T, Miki T, Shimamoto K, Iimura O. Role of adenosine receptor activation in myocardial infarct size limitation by ischaemic preconditioning. Cardiovasc Res 26: 456–461, 1992. doi: 10.1093/cvr/26.5.456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Urquhart P, Rosignoli G, Cooper D, Motterlini R, Perretti M. Carbon monoxide-releasing molecules modulate leukocyte-endothelial interactions under flow. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 321: 656–662, 2007. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.117218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Vachharajani TJ, Work J, Issekutz AC, Granger DN. Heme oxygenase modulates selectin expression in different regional vascular beds. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 278: H1613–H1617, 2000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wang Q, Kalogeris TJ, Wang M, Jones AW, Korthuis RJ. Antecedent ethanol attenuates cerebral ischemia/reperfusion-induced leukocyte-endothelial adhesive interactions and delayed neuronal death: role of large conductance, Ca2+-activated K+ channels. Microcirculation 17: 427–438, 2010. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2010.00041.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Wang X, Yin C, Xi L, Kukreja RC. Opening of Ca2+-activated K+ channels triggers early and delayed preconditioning against I/R injury independent of NOS in mice. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 287: H2070–H2077, 2004. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00431.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wei Y, Liu XM, Peyton KJ, Wang H, Johnson FK, Johnson RA, Durante W. Hypochlorous acid-induced heme oxygenase-1 gene expression promotes human endothelial cell survival. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol 297: C907–C915, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00536.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wojtovich AP, Nadtochiy SM, Urciuoli WR, Smith CO, Grunnet M, Nehrke K, Brookes PS. A non-cardiomyocyte autonomous mechanism of cardioprotection involving the SLO1 BK channel. PeerJ 1: e48, 2013. doi: 10.7717/peerj.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Wrzosek A. The potassium channel opener NS1619 modulates calcium homeostasis in muscle cells by inhibiting SERCA. Cell Calcium 56: 14–24, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.ceca.2014.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Xu W, Liu Y, Wang S, McDonald T, Van Eyk JE, Sidor A, O’Rourke B. Cytoprotective role of Ca2+- activated K+ channels in the cardiac inner mitochondrial membrane. Science 298: 1029–1033, 2002. doi: 10.1126/science.1074360. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yamaguchi T, Dayton C, Shigematsu T, Carter P, Yoshikawa T, Gute DC, Korthuis RJ. Preconditioning with ethanol prevents postischemic leukocyte-endothelial cell adhesive interactions. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 283: H1019–H1030, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00173.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Yamaguchi T, Dayton CB, Ross CR, Yoshikawa T, Gute DC, Korthuis RJ. Late preconditioning by ethanol is initiated via an oxidant-dependent signaling pathway. Free Radic Biol Med 34: 365–376, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S0891-5849(02)01292-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yamaguchi T, Kamada K, Dayton C, Gaskin FS, Yusof M, Yoshikawa T, Carter P, Korthuis RJ. Role of eNOS-derived NO in the postischemic anti-inflammatory effects of antecedent ethanol ingestion in murine small intestine. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 292: H1435–H1442, 2007. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00282.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Yang Q, Zheng FP, Zhan YS, Tao J, Tan SW, Liu HL, Wu B. Tumor necrosis factor-α mediates JNK activation response to intestinal ischemia-reperfusion injury. World J Gastroenterol 19: 4925–4934, 2013. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v19.i30.4925. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Zhang JY, Cheng K, Lai D, Kong LH, Shen M, Yi F, Liu B, Wu F, Zhou JJ. Cardiac sodium/calcium exchanger preconditioning promotes anti-arrhythmic and cardioprotective effects through mitochondrial calcium-activated potassium channel. Int J Clin Exp Pathol 8: 10239–10249, 2015. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Zuidema MY, Yang Y, Wang M, Kalogeris T, Liu Y, Meininger CJ, Hill MA, Davis MJ, Korthuis RJ. Antecedent hydrogen sulfide elicits an anti-inflammatory phenotype in postischemic murine small intestine: role of BK channels. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 299: H1554–H1567, 2010. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.01229.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Zuidema MY, Peyton KJ, Fay WP, Durante W, Korthuis RJ. Antecedent hydrogen sulfide elicits an anti-inflammatory phenotype in postischemic murine small intestine: role of heme oxygenase-1. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 301: H888–H894, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00432.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zuidema MY, Korthuis RJ. Intravital microscopic methods to evaluate anti-inflammatory effects and signaling mechanisms evoked by hydrogen sulfide. Methods Enzymol 555: 93–125, 2015. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2014.11.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]