A higher volume to comfortable fullness postprandially correlated with a higher calorie intake at ad libitum buffet meal. Gastric emptying of solids is correlated to satiation (volume to fullness and maximum tolerated volume) and satiety (the calorie intake at buffet meal) and symptoms of nausea, pain, and aggregate symptom score after a fully satiating meal. There was no significant correlation between gastric accommodation and either satiation or satiety indices, postprandial symptoms, or gastric emptying.

Keywords: pain, nausea, fullness bloating, nutrient

Abstract

The contributions of gastric emptying (GE) and gastric accommodation (GA) to satiation, satiety, and postprandial symptoms remain unclear. We aimed to evaluate the relationships between GA or GE with satiation, satiety, and postprandial symptoms in healthy overweight or obese volunteers (total n = 285, 73% women, mean BMI 33.5 kg/m2): 26 prospectively studied obese, otherwise healthy participants and 259 healthy subjects with previous similar GI testing. We assessed GE of solids, gastric volumes, calorie intake at buffet meal, and satiation by measuring volume to comfortable fullness (VTF) and maximum tolerated volume (MTV) by using Ensure nutrient drink test (30 ml/min) and symptoms 30 min after MTV. Relationships between GE or GA with satiety, satiation, and symptoms were analyzed using Spearman rank (rs) and Pearson (R) linear correlation coefficients. We found a higher VTF during satiation test correlated with a higher calorie intake at ad libitum buffet meal (rs = 0.535, P < 0.001). There was a significant inverse correlation between gastric half-emptying time (GE T1/2) and VTF (rs = −0.317, P < 0.001) and the calorie intake at buffet meal (rs = −0.329, P < 0.001), and an inverse correlation between GE Tlag and GE25% emptied with VTF (rs = −0.273, P < 0.001 and rs = −0.248, P < 0.001, respectively). GE T1/2 was significantly associated with satiation (MTV, R = −0.234, P < 0.0001), nausea (R = 0.145, P = 0.023), pain (R = 0.149, P = 0.012), and higher aggregate symptom score (R = 0.132, P = 0.026). There was no significant correlation between GA and satiation, satiety, postprandial symptoms, or GE. We concluded that GE of solids, rather than GA, is associated with postprandial symptoms, satiation, and satiety in healthy participants.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY A higher volume to comfortable fullness postprandially correlated with a higher calorie intake at ad libitum buffet meal. Gastric emptying of solids is correlated to satiation (volume to fullness and maximum tolerated volume) and satiety (the calorie intake at buffet meal) and symptoms of nausea, pain, and aggregate symptom score after a fully satiating meal. There was no significant correlation between gastric accommodation and either satiation or satiety indices, postprandial symptoms, or gastric emptying.

satiety and satiation play a major role in determining calorie intake in health, obesity, and dyspepsia (1, 16, 25). The contributions of gastric emptying (GE) and gastric accommodation (GA) to satiation, satiety, and postprandial symptoms remain unclear. In a small study comparing 13 obese subjects to 19 nonobese controls, the fasting gastric volume was greater in obese compared with nonobese participants, but the gastric accommodation expressed as the ratio of postprandial/fasting gastric volume was not different between the two groups (14). Furthermore, in a study that pharmacologically modified gastric functions with atropine or erythromycin, fasting (but not postprandial) gastric volume and the rate of GE of liquid nutrients were inversely associated with symptoms during and following ingestion of an Ensure (Abbott Laboratories, Chicago, IL) meal (9). However, a more recent review of the clinical trials on diverse medications, including prokinetics and antiemetics, failed to show a relationship between the effects of those medications on GE and the occurrence of postprandial symptoms (10).

The rationale for the present study is based on the controversy in the literature suggesting either a significant relationship between gastric motor functions and postprandial satiation or symptoms or, on the other hand, a poor relationship between the acceleration of the rate of GE and symptoms. Therefore, our study hypothesis is that GA, and not GE, is significantly associated with postprandial symptoms. Our aims were to evaluate the relationships between GA or GE with satiation (postprandial fullness), satiety (calorie intake), and postprandial symptoms in otherwise healthy volunteers across the spectrum of body mass index (BMI), as well as in discrete BMI groups.

METHODS

Design

Our study comprised two cohorts (total n = 285) studied with the same methods in our laboratory: we retrospectively collected data on 259 across-all BMI subjects who participated in previous prospective studies by Vazquez Roque et al. (25) and Acosta et al. (1) on gastric sensorimotor functions in normal weight, overweight, and obese people (25); we additionally collected the same data on 26 prospectively studied participants with obesity recruited as part of a clinical trial and evaluated at baseline before any intervention. The addition of the latter group was intended to expand the cohort of participants compared with prior studies [n = 73 (25) and n = 259 (1)]. All participants in both cohorts were otherwise healthy and underwent all the measurements of the gastrointestinal traits usually over a 3- to 4-day period: 81 overweight, 173 obese classes I and II, and 34 obese class III. The prior studies compared quantitative gastrointestinal, hormonal, and psychological traits associated with obesity; for example, we showed obesity was associated with higher fasting gastric volume, accelerated GE of solids and liquids, lower postprandial PYY levels, and higher postprandial levels of GLP-1, and identified latent dimensions that accounted for ~81% of the variation among overweight and obese subjects, including satiety or satiation (21%), gastric motility (14%), psychological factors (13%), and gastric sensorimotor factors (11%). In contrast, the present study explored relationships of gastric motor functions with measures of satiation, satiety, and postprandial symptoms across BMI range, rather than the contributions disorders of gastric, incretin, and psychological functions to obesity. The study was approved by Mayo Clinic Institutional Review Board, and all participants gave written, informed consent to participate in the study.

Measurements of Gastrointestinal Traits

Gastrointestinal traits were measured after an 8-h fasting period: GE of solids, fasting and postprandial gastric volumes, satiety, satiation, and symptoms 30 min after reaching MTV at a liquid nutrient drink test (Ensure, 30 ml/min).

Gastric emptying of solids.

GE of solids was assessed by scintigraphy by measuring gastric half-emptying time (GE T1/2) as the primary end point and proportions emptied at 2 and 4 h as secondary end points (25). We used the gender-specific 10th and 90th percentile in healthy volunteers as the normal range for GE T1/2 (5). Since upper gastrointestinal symptoms are primarily associated with delayed GE of solids, we studied exclusively GE of solids (and not liquids) to minimize radiation exposure (21). Scans were taken every 15 min for the first hour and every 30 min for hours 2–4. We estimated the lag time for the GE of solids as the time to 10% emptied.

Gastric accommodation.

GAs was measured by single photon emission tomography (SPECT) as the postprandial to fasting gastric volume ratio: 10–15 min following intravenous administration of a radioactive marker, a fasting scan was obtained using a dual-head gamma camera, followed by a postprandial scan after ingestion of 300 ml of Ensure (2, 4).

Satiation using nutrient drink test.

In this study, we used the definition provided by Cummings et al. (8) for satiation, that is, satiation is defined as the processes limiting meal size by promoting meal termination. Satiation was assessed by measuring the volume to fullness (VTF) and the maximum tolerated volume (MTV) by using the Ensure nutrient drink test with ingestion (1 kcal/ml, 11% fat, 73% carbohydrate, and 16% protein) at a constant rate of 30 ml/min (7). Using a numerical scale from 0 to 5 (0 being no symptom, 3 corresponding to fullness following a typical meal, and 5 corresponding to the MTV), the participants recorded the progression of their fullness sensation, and the Ensure intake was stopped when a score of 5 was reached. The 100-mm horizontal visual analog scales (with “none” and “worst ever” at each extreme) were used to report postprandial symptoms of fullness, nausea, bloating, and pain 30 min after the meal. The aggregate symptom score was calculated as the sum of scores of all four symptoms.

Satiety.

Satiety, which is commonly equated with the absence of hunger, was assessed by the total caloric intake at an ad libitum buffet meal (25).

Outcomes and Statistical Analysis

The primary outcomes of the analysis were the correlations between GE or GA with kcal intake during measurements of satiety and satiation. Subgroup analyses were also performed with assessment of correlations between the same factors for participants with BMI < 35 kg/m2 and for BMI < 30 kg/m2.

The secondary outcome was the correlation between GA or GE and either the aggregate symptom score or individual postprandial symptoms.

Spearman’s rank (rs) and Pearson linear (R) correlation coefficients were used to measure associations among variables that were nonparametric or normally distributed, respectively.

To estimate the contributions of age, gender, BMI, GE, fasting gastric volume, and accommodation volume to indices of satiation (VTF, MTV), satiety (kcal intake at buffet meal), and postprandial symptoms (nausea, pain, aggregate symptoms), we conducted a multiple regression analysis and summarized the results based on parameter estimates and significance values. To normalize the skewed distribution of the residuals, the analysis was done using a square root transformation of the response variables, except for buffet meal, which was transformed to the square root of log scale.

RESULTS

Demographics of Participants

Participants were 73% women, the mean age was 37.9 yr (SD = 11.6), and the mean BMI was 33.5 kg/m2 (SD = 5.0).

Relationships Between Gastric Motor Functions and Calorie Intake

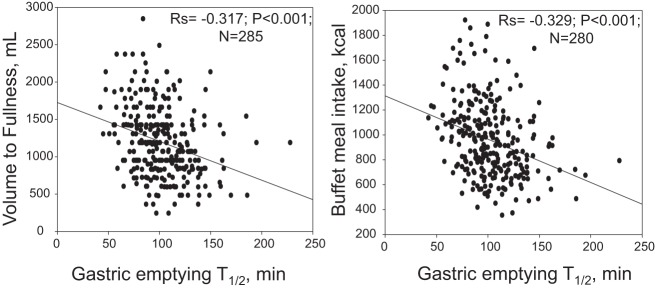

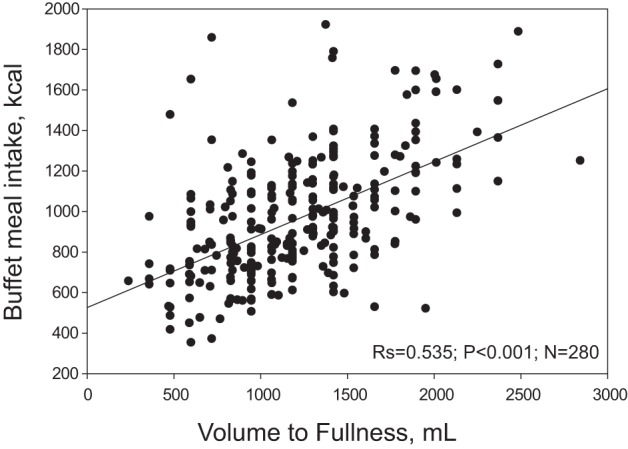

A higher VTF during satiation test correlated with a higher calorie intake at the ad libitum buffet meal (rs = 0.535, P < 0.001, n = 280) (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Relationship between satiation (volume to comfortable fullness) during Ensure nutrient drink test and satiety at a buffet meal test.

Gastric emptying.

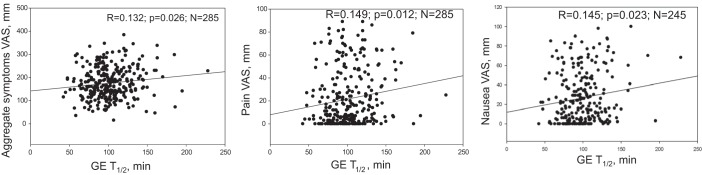

There was a significant inverse (negative) correlation between GE T1/2 and both the VTF (rs = −0.317, P < 0.001, n = 285) and the calorie intake at an ad libitum buffet meal (rs = −0.329, P < 0.001, n = 280) (Fig. 2). Similarly, there was an inverse correlation between GE Tlag and T25% emptied with VTF (rs = −0.273, P < 0.001, n = 282, and rs = −0.248, P < 0.001, n = 284, respectively). The subgroup analyses showed that this inverse correlation between GE T1/2 and both the satiation VTF and the calorie intake at an ad libitum buffet meal was still significant for participants with BMI < 35, and BMI < 30 kg/m2. The results of these analyses are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Relationship of gastric emptying (scintigraphy) with satiation (Ensure nutrient drink test) and with satiety (buffet meal kcal intake) measurements; note lower kcal intake with both Ensure nutrient drink ingested at 30 ml/min and ad libitum buffet meal with slower gastric emptying.

Table 1.

Spearman correlations between gastric half-emptying time, gastric accommodation, satiation and calorie intake at an ad libitum buffet meal in different BMI subgroups

| Variables Tested for Correlation | BMI (kg/m2) | rs | P | n |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kcal buffet meal vs. satiation (VTF), ml | Across-all BMI | 0.535 | <0.001 | 280 |

| BMI < 35 | 0.494 | <0.001 | 179 | |

| BMI < 30 | 0.434 | <0.001 | 79 | |

| Satiation (VTF), ml, vs. GE T1/2, min | Across-all BMI | −0.317 | <0.001 | 285 |

| BMI < 35 | −0.225 | 0.002 | 181 | |

| BMI < 30 | −0.261 | 0.020 | 79 | |

| Kcal at buffet meal vs. GE T1/2, min | Across-all BMI | −0.329 | <0.001 | 280 |

| BMI < 35 | −0.318 | <0.001 | 179 | |

| BMI < 30 | −0.361 | 0.001 | 79 | |

| GE T1/2, min, vs. accommodation, ml | Across-all BMI | 0.048 | ns | 272 |

| BMI < 35 | 0.005 | ns | 173 | |

| BMI < 30 | 0.016 | Ns | 76 | |

| Satiation (VTF) vs. accommodation, ml | Across-all BMI | 0.067 | ns | 272 |

| BMI < 35 | 0.075 | ns | 173 | |

| BMI < 30 | −0.091 | ns | 76 | |

| Kcal at buffet meal vs. accommodation, ml | Across-all BMI | −0.050 | ns | 267 |

| BMI < 35 | 0.023 | ns | 176 | |

| BMI < 30 | −0.162 | ns | 78 |

GE T1/2, gastric half-emptying time; VTF, volume to fullness; BMI, body mass index; rs, Spearman rank correlation; ns, not significant.

GE T1/2 was significantly associated with symptoms of nausea (R = 0.145, P = 0.023, n = 245) and pain (R = 0.149, P = 0.012, n = 285), and with a higher aggregate symptom score (R = 0.132, P = 0.026, n = 285) (Fig. 3). A significant inverse (negative) correlation was found between GE T1/2 and MTV (R = −0.234, P < 0.0001, n = 285). When controlling for the covariate, VTF, a significant association was also found between delay in GE and the symptom of fullness (R = 0.144, P = 0.029, n = 231), in addition to the significant association with the aggregate symptom score (R = 0.192, P = 0.003, n = 231).

Fig. 3.

Relationship of gastric emptying (scintigraphy) and postprandial symptoms: note the increase in aggregate as well as pain and nausea scores with slower gastric emptying (GE).

Gastric accommodation.

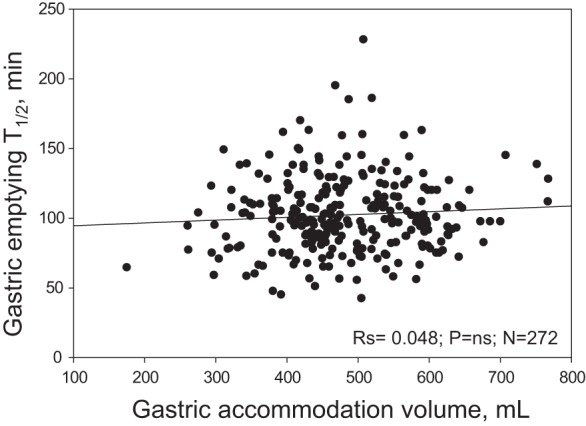

There was no significant correlation between GA and either VTF (rs = 0.067, P = ns, n = 271) or calorie intake at an ad libitum buffet meal (rs = −0.050, P = ns, n = 267) in the entire cohort and in both subgroups (participants with BMI < 35 and for BMI < 30 kg/m2), as shown in Table 1.

In addition, no significant correlation was found between the rate of GE and GA (rs = 0.048, P = ns, n = 272) (Fig. 4). No significant relationship was found between GA and any of the symptoms, or the aggregate symptom score, or the MTV.

Fig. 4.

Absence of significant correlation between gastric emptying T1/2 by scintigraphy and gastric accommodation measured as the difference between postprandial and fasting gastric volume measured by SPECT.

Contribution of independent variables to satiation, satiety, and postprandial symptoms.

This analysis included age, gender, BMI, GE, fasting gastric volume, and accommodation volume. The parameters of age, gender, BMI, nausea, pain, and GAs volume were not significantly associated with any of the dependent variables except that gender was associated with satiety (buffet meal) kcal intake (P = 0.046).

Table 2 shows the parameter estimates (PE) and significance (P value) for the independent variables GE T1/2 and fasting gastric volume. Note slower GE is associated with lower calorie intake to experience fullness (VTF), lower MTV, higher symptom scores, and lower buffet meal intake, whereas higher fasting gastric volumes were associated with higher kcal intake (VTF) and lower symptom scores, but not with the buffet meal.

Table 2.

Parameter estimates and significance (P value) for the independent variables, GE T1/2, and fasting gastric volume

| Satiation VTF |

Satiation MTV |

Satiety Buffet Meal |

Aggregate Symptoms |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent variable | PE | P | PE | P | PE | P | PE | P |

| GE T1/2 | −0.077 | <0.001 | 0.048 | <0.001 | −0.0007 | <0.001 | 0.015 | 0.012 |

| Fasting GV | 0.020 | <0.001 | 0.005 | ns | −0.00005 | ns | −0.007 | 0.002 |

GV, gastric volume; PE, parameter estimates; MTV, maximum tolerated volume.

DISCUSSION

In this study, we showed that GE of solids, rather than GA, was associated with postprandial symptoms as well as satiation measured at an Ensure liquid nutrient test and ad libitum buffet meal in healthy volunteers. In the regression analysis, we confirmed that slower GE is associated with lower calorie intake to experience fullness and higher aggregate symptom scores, whereas higher fasting gastric volumes (but not accommodation volumes) were associated with higher kcal intake with nutrient drink (although not with buffet meal) and lower aggregate symptom scores. This association study suggests that a significant delay in GE in healthy participants may play a role in the generation of postprandial symptoms, including early postprandial fullness. Other potential mechanisms contributing to dyspeptic symptoms are not excluded, such as other impairments of gastric motor functions such as rapid GE, impaired GAs, antral hypomotility, gastric dysrhythmia, and heightened brain-gut perception mechanisms with gastric hypersensitivity and central dysfunctions, which have been demonstrated in patients with functional dyspepsia (3, 11). Therefore, it is plausible that GE accounts for only part of the variance in the development of postprandial symptoms.

In addition, our study shows that GE delay is associated with greater satiation (reduced caloric intake) after liquid nutrient meal and the solid-liquid meal ingested in a buffet meal. This observation is relevant as it provides a rationale for the use of agents that retard GE as a means to induced satiation and reduce appetite in the treatment of otherwise healthy participants with obesity. Such agents include the GLP-1 agonists such as liraglutide, which significantly delays GE (13) and has been shown to result in weight loss at 1 and 3 yr of treatment (15, 19).

By using a well-validated scintigraphy method to measure GE, we were able to show a significant inverse relationship between the rate of GE and the occurrence of symptoms following a dyspeptogenic meal on a separate day. The typical GE test meal is rarely >350 kcal and does not typically induce high symptom scores; thus our decision to use the separate studies a few days apart in each individual.

On the other hand, our results showed no significant correlation between GA and postprandial symptoms. To date, only one study demonstrated an association between symptom improvement and GA with the use of a medication, buspirone (24). Our study suggests that GA is less likely to serve as a biomarker in patients with symptoms of dyspepsia. Future well-designed large clinical trials can prove that therapy targeted at accelerating GE can result in improvement in postprandial symptoms in patients with delayed GE.

There were conflicting prior studies on the relationship between the delay in GE and symptoms, with some reports suggesting that delayed GE might be an asymptomatic incidental condition (12) and others suggesting an association with upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Our data show statistically significant correlation between GE and symptoms, although we acknowledge relatively low R values. We postulate that the correlation is not very strong because upper gastrointestinal symptoms are often multifactorial, with multiple factors playing additive roles including diet, comorbidities, concurrent medication, behavioral symptoms, and BMI.

There are other data supporting a mechanistic role of GE in mediating symptoms, as well as symptom response to efficacious prokinetics. In a study in patients with diabetes (20), both the rate of GE and symptoms improved with the use of metoclopramide, despite the lack of significant correlation between the change in symptoms and the acceleration of GE with the use of parenteral or oral metoclopramide; the R values of 0.09 and 0.29 were reported (for the parenteral and the oral formulation, respectively). However, the study involved only seven patients with GE measurements at the end of the treatment period, and the rate of GE was assessed as the proportion emptied at 90 min, and no dose-response effects were appraised. Although these studies were conducted with metoclopramide, the relationship with more efficacious prokinetic agents would be desirable.

Several studies in the literature are consistent with our results. Stanghellini et al. (23) evaluated GE of solids in patients with functional dyspepsia and showed that the symptoms of postprandial fullness and vomiting (but not pain) were associated with delayed GE of solids (radioisotope technique). Another study showed associations between delayed GE of solids and fullness and vomiting, and between delayed GE of liquids and fullness and early satiety (22). A third study showed that nausea, vomiting, and early satiety were associated with delayed GE at 2 h, but not 4 h (6). There was also better correlation between symptoms and gastric retention at later times (18). Interestingly, we showed significant correlations of symptoms also with lag time and proportion emptied at 2 h. Finally, in a study in patients with diabetic or idiopathic gastroparesis, early satiety and postprandial fullness were associated with increased gastric retention of solids, with GE assessed by scintigraphy, with “decreased water during water load test,” and with other symptoms of gastroparesis (17).

Our study suggests a physiological role of the rate of GE in the perception of satiety, satiation and postprandial symptoms, and GE may serve as a biomarker for therapeutic choices of prokinetic treatments for patients with dyspepsia or retardation of GE in obesity. This potential role of GE as a biomarker will need to be studied in specific, distinct diseases.

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study include robust methods to study gastrointestinal functional traits by using standardized methods in the same laboratory setting, the large sample size, and the use of a dyspeptogenic test approach to evaluate postprandial symptoms.

A potential limitation of this study is the novel approach to measure postprandial symptoms only during the satiation Ensure nutrient drink test and not during the measurement of GE by scintigraphy. The association between postprandial symptoms and the rate of GE was thus established by inference with the symptom data collected during the satiation test. We believe this approach overcomes the low symptom burden associated with the typical 320 kcal meal used as a standard approach to measure GE. Thus we regard this as a minor limitation, as all tests were performed within a few days by using the same protocol for all participants. A definite limitation is that we only studied healthy participants and individuals with obesity who were otherwise healthy; however, we did not study the effect of GE on symptoms in specific conditions such as dyspepsia, gastroparesis, or dumping syndrome, or in response to medications to correct those disturbances of GE. Therefore, our observations may not be generalized to disease states. By establishing a correlation between delay in GE and occurrence of symptoms in healthy participants, our results can serve as a foundation for future research to assess this relationship in disease states and to study the effect of modulating GE on symptoms in those specific conditions.

Conclusion

In healthy volunteers, GE of solids, rather than GA, is associated with postprandial symptoms measured after a maximum tolerated calorie intake at an Ensure liquid nutrient test and with calorie intake at an ad libitum meal. In the future, clinical trials are needed to study the effects on dyspeptic symptoms of individualized therapies targeted at accelerating GE in patients with delayed GE or in retarding GE in patients with obesity to increase satiation and satiety.

GRANTS

M. Camilleri was supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grants R01-DK-67071 and R56-DK-67071; the data were collected during studies funded by R01-DK67071.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

H.H., M.C., and I.O. conceived and designed research; H.H., A.A., M.I.V.-R., I.O., D.D.B., and I.A.B. performed experiments; H.H., M.C., I.O., and A.R.Z. interpreted results of experiments; H.H., M.C., and I.O. prepared figures; H.H., M.C., and I.O. drafted manuscript; H.H., M.C., A.A., M.I.V.-R., I.O., D.D.B., I.A.B., and A.R.Z. edited and revised manuscript; H.H., M.C., A.A., M.I.V.-R., I.O., D.D.B., I.A.B., and A.R.Z. approved final version of manuscript; D.D.B., I.A.B., and A.R.Z. analyzed data.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Cindy Stanislav for excellent secretarial assistance, the nurses and staff of the Mayo Clinic Clinical Research Unit for nursing support and care of patients, and Michael Ryks and Deborah Rhoten for excellent technical support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Acosta A, Camilleri M, Shin A, Vazquez-Roque MI, Iturrino J, Burton D, O’Neill J, Eckert D, Zinsmeister AR. Quantitative gastrointestinal and psychological traits associated with obesity and response to weight-loss therapy. Gastroenterology 148: 537–546.e4, 2015. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2014.11.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bouras EP, Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M, Castillo EJ, Burton DD, Thomforde GM, Chial HJ. SPECT imaging of the stomach: comparison with barostat, and effects of sex, age, body mass index, and fundoplication. Gut 51: 781–786, 2002. doi: 10.1136/gut.51.6.781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bredenoord AJ, Chial HJ, Camilleri M, Mullan BP, Murray JA. Gastric accommodation and emptying in evaluation of patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 1: 264–272, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S1542-3565(03)00130-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Breen M, Camilleri M, Burton D, Zinsmeister AR. Performance characteristics of the measurement of gastric volume using single photon emission computed tomography. Neurogastroenterol Motil 23: 308–315, 2011. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2010.01660.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camilleri M, Iturrino J, Bharucha AE, Burton D, Shin A, Jeong ID, Zinsmeister AR. Performance characteristics of scintigraphic measurement of gastric emptying of solids in healthy participants. Neurogastroenterol Motil 24: 1076–e562, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2982.2012.01972.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cassilly DW, Wang YR, Friedenberg FK, Nelson DB, Maurer AH, Parkman HP. Symptoms of gastroparesis: use of the gastroparesis cardinal symptom index in symptomatic patients referred for gastric emptying scintigraphy. Digestion 78: 144–151, 2008. doi: 10.1159/000175836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chial HJ, Camilleri C, Delgado-Aros S, Burton D, Thomforde G, Ferber I, Camilleri M. A nutrient drink test to assess maximum tolerated volume and postprandial symptoms: effects of gender, body mass index and age in health. Neurogastroenterol Motil 14: 249–253, 2002. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2982.2002.00326.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cummings DE, Overduin J. Gastrointestinal regulation of food intake. J Clin Invest 117: 13–23, 2007. doi: 10.1172/JCI30227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Delgado-Aros S, Camilleri M, Castillo EJ, Cremonini F, Stephens D, Ferber I, Baxter K, Burton D, Zinsmeister AR. Effect of gastric volume or emptying on meal-related symptoms after liquid nutrients in obesity: a pharmacologic study. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 3: 997–1006, 2005. doi: 10.1016/S1542-3565(05)00285-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Janssen P, Harris MS, Jones M, Masaoka T, Farré R, Törnblom H, Van Oudenhove L, Simrén M, Tack J. The relation between symptom improvement and gastric emptying in the treatment of diabetic and idiopathic gastroparesis. Am J Gastroenterol 108: 1382–1391, 2013. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2013.118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Karamanolis G, Caenepeel P, Arts J, Tack J. Association of the predominant symptom with clinical characteristics and pathophysiological mechanisms in functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 130: 296–303, 2006. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kassander P. Asymptomatic gastric retention in diabetics (gastroparesis diabeticorum). Ann Intern Med 48: 797–812, 1958. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-48-4-797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khemani D, Eckert D, O’Neill J, Nelson AD, Ryks M, Rhoten D, Acosta Cardenas AJ, Halawi H, Oduyebo I, Burton D, Clark MM, Zinsmeister AR, Camilleri M. Effects of liraglutide on gastric emptying, gastric accommodation, satiation and satiety after 16 weeks’ treatment: a single-center, randomized, placebo-controlled trial in 32 patients. Gastroenterology 152: S633–S634, 2017. doi: 10.1016/S0016-5085(17)32245-X. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim DY, Camilleri M, Murray JA, Stephens DA, Levine JA, Burton DD. Is there a role for gastric accommodation and satiety in asymptomatic obese people? Obes Res 9: 655–661, 2001. doi: 10.1038/oby.2001.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.le Roux CW, Astrup A, Fujioka K, Greenway F, Lau DCW, Van Gaal L, Ortiz RV, Wilding JPH, Skjøth TV, Manning LS, Pi-Sunyer X; SCALE Obesity Prediabetes NN8022-1839 Study Group . 3 years of liraglutide versus placebo for type 2 diabetes risk reduction and weight management in individuals with prediabetes: a randomised, double-blind trial. Lancet 389: 1399–1409, 2017. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30069-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Park MI, Camilleri M. Gastric motor and sensory functions in obesity. Obes Res 13: 491–500, 2005. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parkman HP, Hallinan EK, Hasler WL, Farrugia G, Koch KL, Nguyen L, Snape WJ, Abell TL, McCallum RW, Sarosiek I, Pasricha PJ, Clarke J, Miriel L, Tonascia J, Hamilton F; NIDDK Gastroparesis Clinical Research Consortium (GpCRC) . Early satiety and postprandial fullness in gastroparesis correlate with gastroparesis severity, gastric emptying, and water load testing. Neurogastroenterol Motil 29: e12981, 2017. doi: 10.1111/nmo.12981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pathikonda M, Sachdeva P, Malhotra N, Fisher RS, Maurer AH, Parkman HP. Gastric emptying scintigraphy: is four hours necessary? J Clin Gastroenterol 46: 209–215, 2012. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31822f3ad2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pi-Sunyer X, Astrup A, Fujioka K, Greenway F, Halpern A, Krempf M, Lau DC, le Roux CW, Violante Ortiz R, Jensen CB, Wilding JP; SCALE Obesity and Prediabetes NN8022-1839 Study Group . A randomized, controlled trial of 3.0 mg of liraglutide in weight management. N Engl J Med 373: 11–22, 2015. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1411892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ricci DA, Saltzman MB, Meyer C, Callachan C, McCallum RW. Effect of metoclopramide in diabetic gastroparesis. J Clin Gastroenterol 7: 25–32, 1985. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198502000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sachdeva P, Malhotra N, Pathikonda M, Khayyam U, Fisher RS, Maurer AH, Parkman HP. Gastric emptying of solids and liquids for evaluation for gastroparesis. Dig Dis Sci 56: 1138–1146, 2011. doi: 10.1007/s10620-011-1635-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sarnelli G, Caenepeel P, Geypens B, Janssens J, Tack J. Symptoms associated with impaired gastric emptying of solids and liquids in functional dyspepsia. Am J Gastroenterol 98: 783–788, 2003. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2003.07389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stanghellini V, Tosetti C, Paternico A, Barbara G, Morselli-Labate AM, Monetti N, Marengo M, Corinaldesi R. Risk indicators of delayed gastric emptying of solids in patients with functional dyspepsia. Gastroenterology 110: 1036–1042, 1996. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8612991. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tack J, Janssen P, Masaoka T, Farré R, Van Oudenhove L. Efficacy of buspirone, a fundus-relaxing drug, in patients with functional dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol 10: 1239–1245, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2012.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vazquez Roque MI, Camilleri M, Stephens DA, Jensen MD, Burton DD, Baxter KL, Zinsmeister AR. Gastric sensorimotor functions and hormone profile in normal weight, overweight, and obese people. Gastroenterology 131: 1717–1724, 2006. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.10.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]