Abstract

Day-night changes in the storage capacity of the urinary bladder are indispensable for sound sleep. Connexin 43 (Cx43), a major gap junction protein, forms hemichannels as a pathway of ATP in other cell types, and the urinary bladder utilizes ATP as a mechanotransduction signals to modulate its capacity. Here, we demonstrate that the circadian clock of the urothelium regulates diurnal ATP release through Cx43 hemichannels. Cx43 was expressed in human and mouse urothelium, and clock genes oscillated in the mouse urothelium accompanied by daily cycles in the expression of Cx43 and extracellular ATP release into the bladder lumen. Equivalent chronological changes in Cx43 and ATP were observed in immortalized human urothelial cells, but these diurnal changes were lost in both arrhythmic Bmal1-knockout mice and in BMAL1-knockdown urothelial cells. ATP release was increased by Cx43 overexpression and was decreased in Cx43 knockdown or in the presence of a selective Cx43 hemichannel blocker, which indicated that Cx43 hemichannels are considered part of the components regulating ATP release in the urothelium. Thus, a functional circadian rhythm exists in the urothelium, and coordinates Cx43 expression and function as hemichannels that provide a direct pathway of ATP release for mechanotransduction and signalling in the urothelium.

Introduction

Humans have the ability to increase bladder capacity and decrease urine production at night-time compared with daytime to avoid disturbances of sleep by micturition1–3. Nocturnal enuresis in childhood and frequent nocturia in the elderly are common and are detrimental to the quality of life by interfering with the patients’ sleeping habits4–8. Insufficient bladder capacity, excessive urine production or both at night-time are the main causes of nocturnal enuresis or frequent nocturia1,9,10. Therefore, clarification of the mechanism(s) of nocturnal enlargement of the bladder would help improve these clinical complaints.

Previously, we have reported that the circadian clock regulated connexin 43 (Cx43), a major gap junction protein, in mouse/rat bladder muscle cells11. Mice are nocturnal (i.e. active primarily during the night), and the phases of their sleep-wake cycles are inverted to those of humans. Their bladder capacity is increased during the sleep/light phase and decreased during the active/dark phase. Cx43 levels in the bladder and the functional bladder capacity showed consistent circadian oscillations in wild-type mice, and the expression level of Cx43 protein in the rat/mouse bladder was inversely correlated with functional bladder capacity. The functional bladder capacity was higher in heterozygous Cx43+/− mice than that in Cx43+/+ mice. However, the circadian rhythms of Cx43 expression level and functional bladder capacity were completely lost in Cry-null mice, which have a dysfunctional circadian clock11. The clock regulator, Rev-erbα, upregulated Cx43 transcription as a co-factor of Sp-1 using Sp-1 cis-elements of the promoter12. However, our previous report focused on bladder muscle cells11–14, and the roles of other components that determine bladder capacity are still unclear.

The urothelium has prominent morphological changes, termed transitional epithelium. The urothelium is a stratified epithelium composed of several layers — the superficial, intermediate, and basal cell layers — that change their morphology in relation to the filling state of the bladder15,16. Urothelial cells appear to be cuboidal when the urinary bladder is not stretched in the vacant phase, and the cells become stretched to a flattened shape when the bladder is filled with urine. Thus, urothelial cells stretch to accommodate increase in urine volume. The primary function of the urothelium is a barrier to prevent the entry of pathogens into the underlying tissues. To achieve this, urothelial cells are connected by tight junctions, or virtually impenetrable junctions that seal the cellular membranes of neighbouring cells17,18.

Urothelial cells also sense changes in stretch and/or intravesical pressure and transmit mechanotransduction signals to the afferent nerve by releasing various neurotransmitters19,20. Of them, ATP released to the basal side of the urothelium activates purinergic receptors such as P2X2 and P2X3 expressed by afferent nerves in the suburothelium21–25, whereas ATP released to the luminal side activates various P2X and P2Y receptors on the urothelium in an autocrine/paracrine manner to form a positive feedback loop of ATP secretion26,27. These findings suggest that ATP modulates bladder capacity by transmitting mechanotransduction signals.

In general, there are two pathways for cellular ATP release — vesicular and non-vesicular mechanisms. Vesicular ATP release involves exocytosis28 while non-vesicular ATP release might be mediated by mechanical stretch, activation of voltage and/or ligand-gated ion channels and receptors, mitochondrial porins, ATP binding cassette transporters, Pannexin1 (PANX1)27,29, Transient Receptor Potential Vanilloid4 (TRPV4)30 and PIEZO131. Recently, it has been reported that Cx43 forms hemichannels in the pathway for non-vesicular ATP release in bone cells and astrocytes32,33.

Based on the above, we hypothesized that the increased functional bladder capacity during sleep-time at night was promoted by the decrease of mechanotransduction signalling by ATP through C43 hemichannels in the urothelium via the functional circadian clock. Here, we investigated the circadian role of the urothelium for ATP release through regulating Cx43 expression and the function of hemichannels in urothelial cells in mice and humans.

Results

Cx43 is expressed in human and mouse urothelium

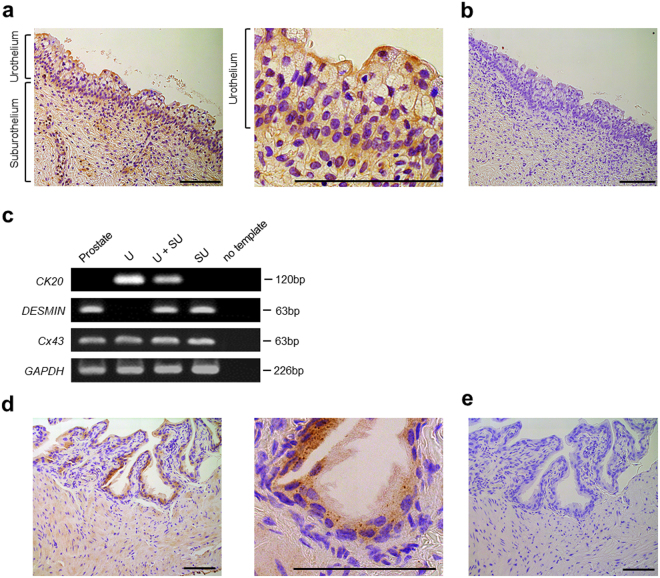

We determined whether Cx43 is expressed in the human urothelium by immunostaining and reverse transcriptional polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) of Cx43 in non-pathological human bladder tissue. The normal human urothelium showed positive staining for Cx43 (Fig. 1a,b). Within the urothelium, basal cells strongly expressed Cx43 as reported in rats34, and umbrella and intermediate cells mildly expressed Cx43 with a scattered staining pattern. RT-PCR demonstrated the expression of Cx43 in the urothelium (Fig. 1c). These results confirmed normal human urothelium contains Cx43 expression.

Figure 1.

Cx43 immunohistochemistry (IHC) in normal human/mouse bladder mucosa. (a) The normal human urothelium shows positive Cx43 staining. (b) IHC with only the secondary antibody as a negative control. (c) Normal human urothelium expresses Cx43 in the urothelium (U) and the suburothelium (SU) by RT-PCR analysis. Cytokeratin 20 (CK20) and desmin were used as urothelial and suburothelial markers, respectively. Normal human prostate was used as a reference. (d) Normal mouse urothelium shows positive Cx43 staining. (e) IHC with only the secondary antibody was used as a negative control. All scale bars indicate 100 µm.

We also examined whether Cx43 is expressed in the mouse urothelium. We performed immunostaining and detected Cx43 expression in normal mouse urothelium (Fig. 1d,e). In addition, we conducted layer-specific dissection (Supplementary Fig. S1a) and found considerable Cx43 mRNA expression in the urothelium by real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis. Immunoblot analysis with layer-specific samples further confirmed the presence of Cx43 in the urothelium (Supplementary Fig. S1b). These findings demonstrate that Cx43 is expressed in human and mouse urothelium.

Mice urothelium contains an endogenous circadian clock and Cx43 oscillation

Because the distribution and expression of Cx43 are similar in humans and mice, we used mouse urothelium to characterize the circadian role of Cx43 in urothelial cells. To examine whether mouse urothelium per se has a circadian clock, we characterized the endogenous clock oscillation in ex vivo cultured urothelium isolated from Per2Luciferase knock-in (Per2::luc) gene reporter mice. We found a robust Per2::luc oscillation of at least six cycles (Fig. 2a, Supplementary Fig. S2) with a period of oscillation of 24.13 ± 0.07 (mean ± s.e.m.). This oscillation was not observed in Per2::luc Bmal1-knockout mice (Per2::luc/Bmal1−/−) (Fig. 2a). These results demonstrate that the bladder urothelium has an endogenous oscillatory machinery.

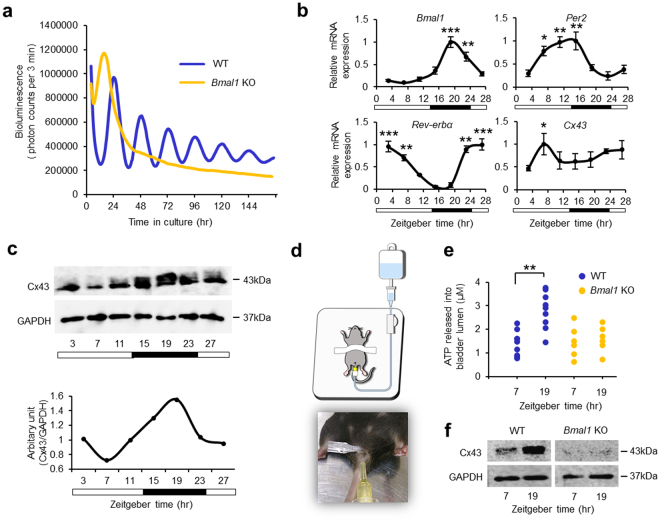

Figure 2.

Oscillation of Cx43 and Clock gene expression in mouse urothelium. (a) Representative oscillation of bioluminescence in the urothelium obtained from Per2::luc mice from an ex vivo culture. The period of oscillation was 24.13 ± 0.07 (mean ± s.e.m) (n = 3). The oscillation of bioluminescence in Per2::luc/Bmal1−/− mice were lost completely. (b) Temporal mRNA accumulation of Bmal1, Per2, Rev-erbα and Cx43 in the urothelium from mice under LD condition. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs. the nadir value (ZT 7 in Bmal1, ZT 23 in Per2, ZT 15 in Rev-erbα and ZT 3 in Cx43) by one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test (n = 4 for each time point). The P-values with Cosinor analysis in Bmal1, Per2, Rev-erbα and Cx43 were 0.02, 0.002, 0.005 and 0.1 respectively. ZT; Zeitgeber time. (c) Representative temporal Cx43 protein accumulation in the mice urothelium under LD condition as shown by immunoblotting (Cosinor analysis, P = 0.01). Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S11. (d) A schematic image and photograph of bladder distention to measure the concentration of ATP released into the bladder. (e) Temporal change in the concentration of ATP release after bladder distention. The high/low level was in accord with the Cx43 expression in the urothelium of mice. **P < 0.01 by Student’s t-test (n = 9), which was completely lost in Bmal1-knockout mice (n = 6). (f) Circadian change of Cx43 protein expression in the urothelium of wild-type mice was lost in Bmal1-knockout mice. Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S11. All error bars indicate s.e.m.

However, it was unknown whether these cellular oscillations of the circadian clock persisted in the bladder urothelium in vivo. We collected urothelium from mouse bladders at seven consecutive time points every 4 hours during the day (zeitgeber time (ZT) 0, 4, 8, 12, 16, 20 and 24) to elucidate whether the circadian clocks exist in the urothelium. RT-PCR analysis demonstrated that the major clock genes Bmal1, Per2 and Rev-erbα mRNA had robust diurnal rhythms, that Cx43 mRNA also had diurnal variation in the urothelium (Fig. 2b), and that Cx43 protein was cycled in abundance with a diurnal rhythm (Fig. 2c). Immunoblot analysis demonstrated Cx43 peaked at the middle of the active/dark phase for mice, but was lowest at the middle of the sleep/light phase. The peak of Cx43 protein expression was delayed for 8–12 hrs from the peak of Cx43 mRNA expression. These results suggested that a post-transcriptional mechanism was required to induce the circadian rhythm of Cx43 protein expression from the diurnal variation of mRNA expression. These findings demonstrate that the levels of Cx43 display diurnal rhythms in the mouse urothelium in vivo, in conjunction with its circadian regulator, Rev-erbα, as we reported in the bladder smooth muscle11.

ATP released into the bladder lumen undergoes daily variations in mice

We next examined whether ATP released from the urothelium had a diurnal variation in mice. We measured the concentration of ATP in the bladder lumen after bladder distention with 30 cm H2O for 10 minutes at ZT7, a resting phase for mice, and ZT19, an active phase (Fig. 2d). The concentration of ATP was significantly higher at ZT19 than at ZT7 (p < 0.01), which was in accord with Cx43 expression in the urothelium in wild-type mice. However, such diurnal changes in ATP release and Cx43 protein expression was lost in arrhythmic Bmal1-knockout mice (Fig. 2e,f). These results suggest that ATP release from the urothelium induced by bladder distension undergoes daily variations regulated by the circadian clock and that changes in ATP release in the resting phase versus the active phase may be involved in the daily oscillation of functional bladder capacity.

Immortalized human urothelial cells exhibit circadian cycles of Cx43 expression and ATP release

We found circadian profiles of the clock genes, as well as Cx43 and ATP release in the urothelium. To investigate the causal-relationship among these findings, we used hTERT-immortalized human urothelial cells (TRT-HU1)27,35–37.

Before examining these relationships, we investigated whether this cell line was suitable for circadian study. After synchronization of the circadian clock by serum shock after applying 50% FBS38, we assessed Cx43 protein and mRNA levels every 6 hours in individual groups for 60 hours. The major clock genes BMAL1, PER2, and REV-ERBα mRNA had circadian rhythms and Cx43 mRNA showed a variation in vitro similar to the urothelium of mice in vivo (Fig. 3a). In addition, Cx43 protein showed an overt circadian rhythm in immunoblot analysis (Fig. 3b). ATP release induced by rinsing with cell bathing solution showed a significantly lower concentration at 6 and 30 hours after serum shock compared with control at 0 hour before serum shock (Fig. 3c). This variation in ATP release coincided with the change of Cx43 protein expression in the human urothelial cells (Fig. 3b). The synchronous circadian oscillations of Cx43 expression and ATP release suggest a functional correlation between Cx43 and ATP.

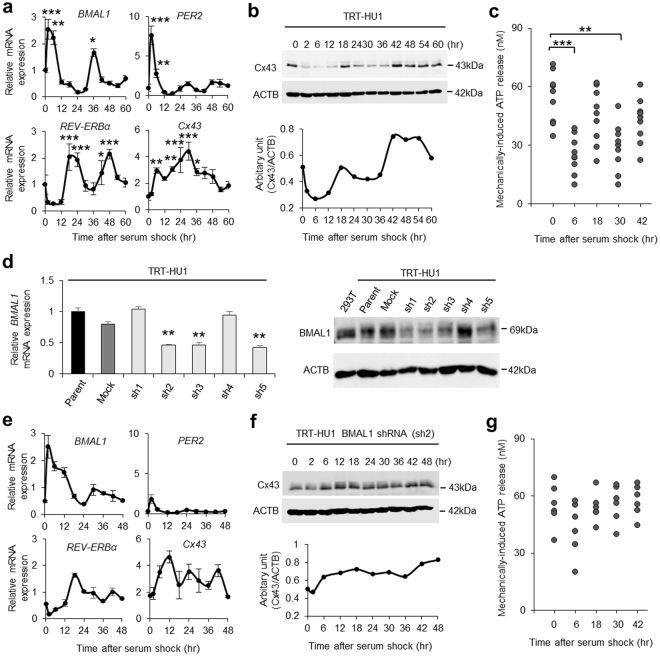

Figure 3.

Oscillation of Cx43 and Clock gene expression in immortalized human urothelial cells. (a) Temporal variation of mRNA accumulation of clock genes and Cx43 mRNA levels in serum-shocked immortalized human urothelial cells (TRT-HU1). The major clock genes BMAL1, PER2, and REV-ERBα had circadian rhythms.*P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs. the nadir value (time 24 in BMAL1, time 18 in PER2, time 6 in REV-ERBα and time 0 in Cx43) by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test (n = 3). The P-values with Cosinor analysis in Bmal1, Per2, Rev-erbα and Cx43 were 0.01, 0.0001, 0.002 and 0.09, respectively. (b) Representative immunoblots showing temporal changes in Cx43 protein levels in serum-shocked TRT-HU1 (Cosinor analysis, P = 0.006). Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S12. (c) Temporal variation of mechanically induced ATP release in TRT-HU1 after serum-shock. **P < 0.01 and *** P < 0.001 by one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test (n = 9). (d) Stable knockdown of BMAL1 in TRT-HU1 (sh1-sh5). **P < 0.01 vs. mock by Student’s t-test (n = 3). Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S12. (e) Temporal variation of mRNA accumulation of clock genes and Cx43 mRNA levels in serum-shocked sh2 TRT-HU1 (TRT-HU1 BMAL1 shRNA). (f) Representative immunoblots showing disturbed temporal changes in Cx43 protein levels in serum-shocked BMAL1 shRNA TRT-HU1. Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S12. (g) Disturbed temporal variation of mechanically induced ATP release after serum-shocked sh2 TRT-HU1 (n = 6). All error bars indicate s.e.m.

To demonstrate that the Cx43 expression and ATP release are under the control of the circadian clock, we investigated the influence of BMAL1-knockdown on the circadian rhythm in urothelial cells. After the transfection of five different BMAL1 shRNA plasmids (sh1-5) to TRT-HU1, BMAL1 shRNA plasmid (sh2) transfected cells (sh2 TRT-HU1) had the highest efficacy in BMAL1 knockdown by real-time quantitative RT-PCR and immunoblotting (Fig. 3d). After serum shock, the oscillation of PER2 and REV-ERBα as well as BMAL1 mRNA expression became unclear in sh2 TRT-HU1 compared with that in parent TRT-HU1 (Fig. 3e, Supplementary Fig. S3). Accordingly, the oscillation of Cx43 protein expression was lost in sh2 TRT-HU1 (Fig. 3f). In addition, the circadian rhythm of mechanically induced ATP release disappeared in sh2 TRT-HU1 (Fig. 3g). Furthermore, to confirm whether Cx43 mRNA expression was regulated by Rev-erbα and Sp-1 in urothelial cells as in smooth muscle cells11, a Cx43 promoter-reporter assay was performed using TRT-HU1. As a result, Cx43 transcription was upregulated in coexistence with Rev-erbα and Sp-1 in TRT-HU1 (Supplementary Fig. S4). These results suggest that the circadian clock system may regulate the oscillation of Cx43 expression and ATP release in urothelial cells.

ATP is released from Cx43 hemichannels in urothelial cells

To investigate whether Cx43 is one of the pathways of ATP release in urothelial cells, we generated Cx43 knockdown and overexpressing immortalized human urothelial cells by using two types of immortalized human urothelial cells — TRT-HU1 and TERT-NHUC39,40. As for the BMAL1-knockdown procedure, the transfection of five different Cx43 shRNA plasmids (sh11-15) to TRT-HU1 indicated that the shRNA14 (sh14 TRT-HU1) and sh13 (sh13 TRT-HU1) plasmids had the two highest efficacies (Fig. 4a, Supplementary Fig. S5). The concentration of mechanically induced ATP release was significantly lower in sh13 and sh14 TRT-HU1 cells compared with that in control cells (Fig. 4b). However, Cx43-overexpressing TERT-NHUC showed a significantly higher concentration of mechanically induced ATP release compared with the control cells (Fig. 4c,d, Supplementary Fig. S6). In these two Cx43 knockdown/overexpressing cell types, mRNA expressions of BMAL1 and other candidate genes associated with urothelial ATP release, PANX126,27, TRPV430, PIEZO131 and Vesicular Nucleotide Transporter (VNUT)28 were not correlated with the increase/decrease of ATP release (Supplementary Figs S7, S8). These results suggest that ATP release from urothelial cells is under the direct control of Cx43 rather than that of Bmal1 or other potential genes for the activation of ATP release driven by Bmal1 that are yet to be identified.

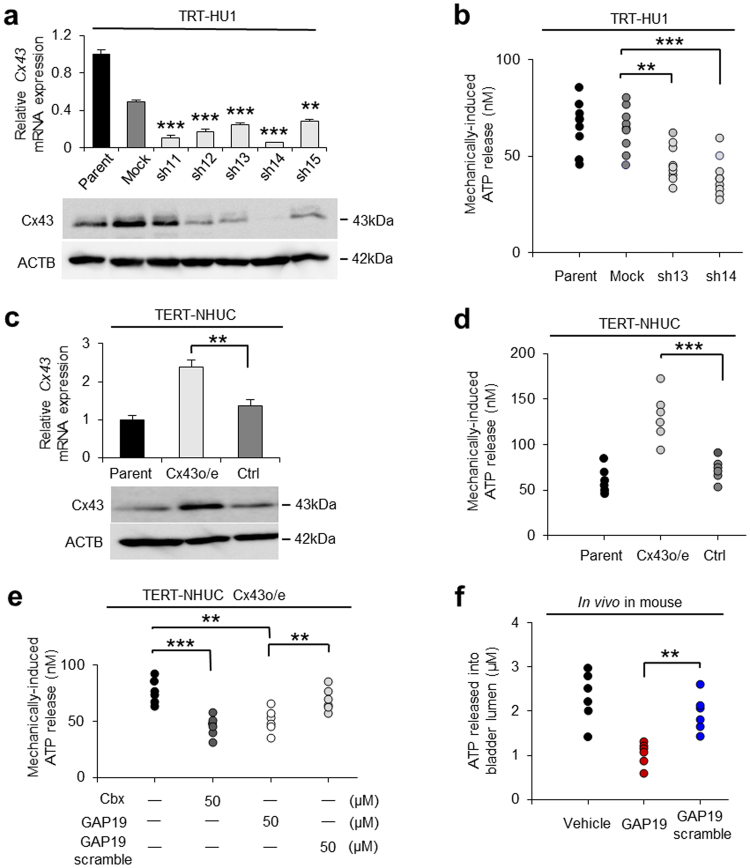

Figure 4.

Mechanically induced ATP release via Cx43 hemichannels has diurnal variation. (a) Stable knockdown of Cx43 in TRT-HU1 (sh11-sh15). **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 vs. mock by Student’s t-test (n = 3). Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S13. (b) Mechanically-induced ATP release was decreased in both sh13 and sh14 TRT-HU1. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001 by Student’s t-test (n = 9). (c) Cx43-overexpression in TERT-NHUC (Cx43 o/e TERT-NHUC). **P < 0.01 by Student’s t-test (n = 3). Full-length blots are presented in Supplementary Fig. S13. (d) Increased mechanically induced ATP release in Cx43 o/e TERT-NHUC. ***P < 0.001 by Student’s t-test (n = 6). (e) Mechanically-induced ATP release in the presence of carbenoxolone and GAP19 peptide. Each reagent was used at 50 µM. **P < 0.001 by Student t-test (n = 6). (f) The concentration of ATP release after bladder distention in the presence of GAP19 peptide and GAP19 scramble peptide in vivo in mice at ZT19. **P < 0.01 by Student’s t-test (n = 6). All error bars indicate s.e.m.

In addition, mechanically induced ATP release was significantly reduced in the presence of carbenoxolone (Cbx), a gap junction and hemichannel inhibitor, compared with the control cells. To clarify the role of the two types of Cx43 channels, we used GAP19 peptide41,42, a specific Cx43 hemichannel blocker. Mechanically induced ATP release was significantly lower in the presence of the GAP19 peptide than that in the presence of scramble control of GAP19 peptide (Fig. 4e), while dye-transfer length indicating gap junction function was not prevented in the GAP19 peptide (Supplementary Fig. S9a) different from using sh14 TRT-HU1 cells that significantly decreased the length (Supplementary Fig. S9b). These results suggest that urothelial cells employ Cx43 hemichannel rather than Cx43 gap-junction for ATP release.

To investigate whether Cx43 hemichannels function in vivo, GAP19 peptide was used for the examination of ATP release by bladder distention in mice at ZT19. The concentration of ATP release was significantly lower in the presence of GAP19 peptide than that in the presence of GAP19 scramble peptide (Fig. 4f). Based on these results, Cx43 hemichannels are considered part of the components regulating ATP release in the urothelium. Therefore, we propose that circadian rhythm in the urothelium coordinates the diurnal change in ATP release via Cx43 hemichannels, which modulate functional bladder capacity (Supplementary Fig. S10).

Discussion

The fundamental adaptive advantage of the circadian clock is that it allows for predictive, rather than entirely reactive, homeostatic regulation of physiological functions. Diurnal change in functional bladder capacity provides an adaptive advantage to secure sound sleep as well as to function correctly for daily increases in urine production in the arousal phase5–8. In the current study, we focused on the circadian clock function of the urothelium and presented evidence for the existence of Cx43 in the human and mouse urothelium, the daily rhythms of clock genes and Cx43 in the mouse urothelium and immortalized human urothelial cells, and the function of Cx43 as a hemichannel for ATP release. Circadian clock-regulated ATP release from Cx43 might contribute in part to the adaptation of functional bladder capacity in daily life.

An important result in this study was the finding that the bladder urothelium has a circadian rhythm generated by the circadian clock and that this indeed modulates urothelial ATP release mechanically stimulated by bladder distension in a circadian manner. Diurnal variations in ATP play a crucial role in various organisms. In rodents, the diurnal change in extracellular ATP levels in astrocytes may provide a mechanism for the clock control of gliotransmission between astrocytes and neurons, which might be associated with sleep-wake changes in the brain by modulating energy metabolism and glial activity43,44. Clinically, the diurnal enhancement of pain hypersensitivity might be mediated by the clock gene controlled glucocorticoid-induced enhancement of extracellular ATP release in the spinal cord45. As above, diurnal variations in ATP levels might be an important mechanism in nature and it is noteworthy that the physiological role of the circadian clock in the urothelium has been demonstrated here.

The mechanism of circadian ATP release from the urothelium was also demonstrated in this study. Cx43 expression had a circadian rhythm in the bladder urothelium and Cx43 functioned as a hemichannel to release ATP in urothelial cells. In addition, the concentration of mechanically induced ATP release had oscillations that correlated with Cx43 expression in the urothelium. It is generally understood that urothelial cells sense the extension stimulus and release ATP, which is essential for the micturition reflex19,46. Stretch-induced urothelial ATP release evokes afferent nerves within the suburothelial tissues via P2X and P2Y receptors and conveys a sense of bladder filling to the central nervous system23–27. Considering the diurnal change of mechanically induced ATP release via Cx43 hemichannels in the present study and the increased functional bladder capacity in Cx43 hetero-knockout mice11,47,48, we infer that the diurnal rhythm of micturition is regulated by diurnal changes in the level of perception for bladder distention.

Our study had some limitations. It was unclear how and to what extent the Cx43 hemichannels are involved in the pathway of ATP release. ATP is abundant in the cell cytoplasm and is released extracellularly by several mechanisms49,50. Our previous study of whole bladder microarray analysis demonstrated that other genes involved in the major pathways of ATP release including Panx1 channels did not show significant circadian change11 (microarray data deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus under accession code GSE35795). In addition, Panx1+/+ and Panx1−/− mice displayed a similar phenotype in voiding micturition pattern51. However, it was reported that clock genes regulate the circadian expression of several genes associated with ATP release in ex vivo mouse bladder mucosa52. Although our current results do not exclude the role of other genes in the circadian change of ATP release in the urothelium because the expression amount was also regulated at multiple levels by transcriptional, post-transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms53, the present study demonstrated diurnal ATP release in the urothelium as well as functionally associated diurnal variation in Cx43 expression.

Another limitation is that roles of the circadian clock and ATP in physiological or pathological conditions in humans have not been investigated yet. Urothelial ATP signalling is involved in pathological conditions such as overactive bladder, but the role of P2X2/3 receptors is still controversial in physiological conditions19,54,55. Interestingly, it was suggested that the circadian clock in the bladder is modulated by endogenous purinergic receptors and that dysregulation of the interaction between the clock and major endogenous receptors may have an effect on maintaining bladder functions56. Further studies are expected to elucidate the roles of the circadian clock and ATP signalling in human micturition.

Despite these limitations, our study revealed that the circadian clock in the urothelium contributes to the formation of diurnal changes of ATP release through the coordination of Cx43 expression, which may modulate day–night changes in functional bladder capacity. This novel concept has the potential to lead to a new treatment strategy for nocturnal enuresis in childhood and/or frequent nocturia in the elderly, which are detrimental to the quality of life.

In conclusion, a functional circadian rhythm exists in the urothelium, and coordinates Cx43 expression and function as hemichannels that provide a direct pathway of ATP release for mechanotransduction and signalling in the urothelium. This understanding warrants further investigation for diseases characterized as disorders of micturition rhythm including nocturnal enuresis and nocturia.

Methods

Animals

Five-week-old female C57BL/6 mice were purchased from CLEA Japan (Tokyo, Japan) or Japan SLC, Inc. (Hamamatsu, Japan). Global Bmal1-knockout C57BL/6 mice were generated by mating Probasin-Cre; Bmal1flx/flx mice57–59. Mice were housed at a constant room temperature with a cycle of 14 hours light (7:00 am to 9:00 pm) and 10 hours dark (9:00 pm to 7:00 am). Food and water were available ad libitum. All animal experiments were approved by the Kyoto University animal experiment committees (Permit Number: Medkyo15504), and all animals used in this study were treated according to the guidelines for animal experimentation of the experimental animal center of Kyoto University.

Immunohistochemistry of normal human and mouse bladder

Normal human bladder tissue was obtained from a 67-year-old female patient who underwent anterior pelvic exenteration under the diagnosis of urethral malignant melanoma after informed consent. Immunostaining with Cx43 antibody (C6219, Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was performed with normal testis as a positive control. Normal mouse bladder tissue was obtained from ten-week-old female C57BL/6 mice. Immunostaining with Cx43 antibody (C6219, Sigma-Aldrich) was performed with normal heart as a positive control. All human experiments were performed in accordance with guidelines on the use of human materials in Kyoto University, and all human experiments were approved by the ethical committees at Kyoto University Hospital. All immunostaining was performed at the Center for Anatomical, Pathological and Forensic Medical Researches in Kyoto University.

Reverse transcriptional PCR of normal human bladder

Normal human urothelium was obtained from a 39-year-old male patient who underwent pelvic exenteration under the diagnosis of advanced rectal cancer after informed consent. Normal urothelium was obtained by scraping the bladder mucosa with a scalpel, and the suburothelium was obtained by resection with scissors. Normal human prostate was obtained as a positive control from a 73-year old male patient who underwent holmium laser enucleation of the prostate (HoLEP) under the diagnosis of benign prostatic hyperplasia. Total RNA was extracted using an RNeasy Mini kits (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocols and complementary DNA was synthesized from 1 µg of RNA using ReverTra Ace qPCR RT Kit (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). The primers for PCR are shown in Supplementary Table S1. Reaction mixtures were denatured at 94 °C for 2 min, followed by 35 PCR cycles using Mastercycler nexus GSX1 (Eppendorf, Germany). Each cycle consisted of the following steps: 94 °C for 20 s, 58 °C for 30 s, and 72 °C for 35 s.

Bioluminescence recording

The urothelium were obtained from adult Period2Luciferase knock-in (Per2::luc) mice (Jackson Laboratories)60. The urothelial layer was dissected away from the smooth muscle layer using ophthalmology scissors and cultured with 800 µl of Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM, Sigma-Aldrich), supplemented with 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.2), 2% B27 (Thermo Scientific, Rockford, IL, USA), 25 units/ml penicillin, 25 mg/ml streptomycin, and 1 mM luciferin, in 35-mm dish, and air sealed. Bioluminescence was continuously monitored without interruption for 7 days immediately upon placement in culture with a dish-type photon countable luminometer (Kronos Dio, ATTO, Tokyo, Japan) at 35 °C.

Tissue preparation

Eight-week-old female C57BL/6 mice anesthetized with isoflurane and euthanized by cervical dislocation, were analysed at seven consecutive time points every 4 hours during the day under a dim light (n = 6 for each time). The bladders were removed and sliced open in a 6-cm dish containing cold normal saline. We scraped the bladder mucosa with a cell scraper in cold normal saline, and collected the normal saline including desquamated urothelium. It was immediately cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen for protein assay, or mixed with RNAlater (Sigma-Aldrich) preserved at 4 °C for mRNA assay. The remaining suburothelium and smooth muscle layer were gathered together as a reference, and a part of the liver was used as a control.

Cell culture

The hTERT-immortalized human urothelial cell line (TRT-HU1) generated by Dr. Louis S. Liou was a gift from Dr. Rosalyn M. Adam (Urological Diseases Research Center, Children’s Hospital Boston, Boston), and hTERT-immortalized normal human urothelial cells (TERT-NHUC) were generated and kindly provided by Dr. MA Knowles (Cancer Research UK Clinical Centre, St James’s University Hospital, Beckett Street, Leeds LS97TF, UK). TRT-HU1 cells were maintained in DMEM (Sigma-Aldrich) containing 2 mM L-glutamine and 110 mg/L sodium pyruvate supplemented with 15% FBS (GIBCO), non-essential amino acids (GIBCO), and 1.15 mM 1-thioglycerol, as previously described32. TERT-NHUC cells were maintained in KSFM (Life Technologies Ltd, Paisley, UK) supplemented with the supplied bovine pituitary extract and epidermal growth factor in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 at 37 °C, as previously described36.

Serum shock analysis of hTERT-cells

As previously reported38, TRT-HU1 were cultured until sub-confluent in DMEM with 15% FBS followed by 48 hours incubation in DMEM with 0.5% FBS. The cells were treated with 50% horse serum (GIBCO) in DMEM for 2 hours, and washed twice with DMEM and then maintained in DMEM with 0.5% of FBS for a maximum of 72 hours. The time 0 (hr) in the figures indicates before serum shock.

Immunostaining of hTERT-cells

After washing with TBS (3 times, 5 min), the cells were permeabilized for 30 min with 0.25% Triton X-100 (in TBS), blocked for 60 min with 1% bovine serum albumin (BSA, in TBS) and incubated 2 days with primary antibodies (in 1% BSA + 0.4% Triton X-100) at 4 °C. The following primary antibodies were used: rabbit polyclonal Cx43 antibody (C6219, Sigma-Aldrich, 1:500), mouse monoclonal anti-vimentin antibody (ab8978, 1:100, Sigma-Aldrich). Donkey anti-mouse IgG (H + L) Alexa Fluor 488 (ab150105, Abcam, Cambridge, UK) was used as secondary antibody followed by DAPI nuclear staining.

Real-time quantitative RT-PCR analysis

Total RNA extraction and complementary DNA synthesis from the mouse urothelium or cultured cells was done using the same procedure as for the human urothelium. Real-time quantitative RT-PCR was performed with SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA) and a 7300 Real-time PCR system (Life Technologies). The thermal cycling conditions were 94 °C for 15 s, 60 °C for 15 s, and 72 °C for 1 min. Values were adjusted relative to the expression levels of the housekeeping gene Gapdh or 18 s ribosome. Primers used are listed in Supplementary Table S1. The ΔΔCt method was used to determine the relative gene expression of the genes of interest.

Immunoblotting

Whole cell lysates from bladder urothelium and cultured cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer containing proteinase inhibitors, which were resolved by SDS-PAGE and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Millipore, Bedford, MA, USA) using a Mini Trans-Blot Cell system (Bio-Rad Laboratories). Membranes were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin diluted in TBST (BSA/TBST) and incubated with primary antibodies diluted in 1% BSA/TBST followed by incubation with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies diluted in 1% BSA/TBST and developed for reading by enhanced chemiluminescence (SuperSignal West Pico Chemiluminescent Substrate, Thermo). Images were acquired with the LAS-4000 imaging system (Fujifilm Life Science, Tokyo, Japan). Anti-Cx43 (C6219, Sigma-Aldrich, 1:8000), anti-BMAL1 (ab93806, Abcam, 1:500), anti-beta actin (ab6276, Abcam, 1:5000) and anti-GAPDH (GAPDH, 2118, Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA, USA, 1:5000) were used as the primary antibodies.

Cell transfection

Stable knockdown of Cx43 or BMAL1 was accomplished using shRNA. Lentivirus-based plasmids containing TRC2-pLKO-puro shRNA sets to human BMAL1 (SHCLNG-NM_001178; TRCN0000331011 (sh1), TRCN0000331012 (sh2), TRCN0000331014 (sh3), TRCN0000331078 (sh4), TRCN0000331079 (sh5) and the same sets to human Cx43 (SHCLNG-NM_000165; TRCN0000333535 (sh11), TRCN0000344841 (sh12), TRCN0000344842 (sh13), TRCN0000344843 (sh14), TRCN0000353147 (sh15)) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Non-silencing shRNAs (Sigma-Aldrich) were used as negative controls. To obtain Cx43-overexpressing urothelial cells, Precision LentiORF GJA1w/Stop Codon (OHS5897-202619897) and Precision LentiORF RFP Control Glycerol Stock (OHS5832) were purchased from Open Biosystems (Huntsville, AL, USA). The experimental procedure for transfection was performed according to the Sigma-Aldrich or Open Biosystems technical manual.

Measurement of ATP release in vivo and in vitro

After eight-week-old female C57BL/6 mice with or without Bmal1-knockout were anesthetized with 4% (induction) and 2% (maintenance) isoflurane, a 24 G catheter (SR-OT2419C, Terumo, Tokyo, Japan) was inserted into the urethra and clamped with a clip (AM-1, Natsume Seisakusho Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan), and connected to a tube filled with phosphate buffered saline (PBS). After bladder distention with 30 cm H2O for 10 minutes, we collected the PBS from the bladder lumen. The ATP concentration in the samples was calculated from standard curves constructed using ATP from 20 nM to 20 μM.

Measurement of ATP release in vitro

The luciferin-luciferase assay (CellTiter-Glo®2.0 Assay; Promega, Madison, WI, USA) was used to quantify the amounts of ATP released in the bathing solution of cultured cells in response to rinsing-induced mechanical stimulation27. Briefly, 20 μl of bathing solution samples were individually placed in triplicate in white walled 96-well plates (Nunc F96 MicroWell; Thermo), and 100 μl CellTiter-Glo®2.0 reagent was added directly to each well. Plates were incubated at room temperature for 15 minutes and were transferred to the Multilabel Plate Reader VICTOR X5 (PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, USA), where luminescence was measured using a 1-sec integration time. The ATP concentration in the samples was calculated with the same procedure as for the in vivo study.

Dye-transfer experiment

Dye-transfer experiment was performed with Lucifer yellow (LO259, Sigma). In 6 cm dishes, confluently cultured cells were cut with a diamond cutter in the presence of Lucifer yellow followed by 4% PFA fixation. Images in fluorescence along with the cutting line were taken and the dye-transfer lengths from the cutting edge were measured using ImageJ software (http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij/).

Reagents

Carbenoxolone disodium salt (CBX), GAP19 peptide (KQIEIKKFK) and GAP19 scramble peptide (IKFKKEIKQ) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Statistical analysis

All data are expressed as the mean ± s.e.m. JMP Pro 11 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) was used for statistical analysis. Unpaired t-test, one-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test, one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc test were performed when appropriate. The P-values of gene oscillation were calculated using a free Cosinor analysis software (Version 3.1) available at http://www.circadian.org/softwar.html. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant. In the figures, statistical significance is indicated as follows: *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001.

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We thank T. Okinami and Sylvia Suadicani for scientific support and advice. This work was supported by Grants-in-Aid for Scientific Research (15H05682, 25893100) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, a Young Research Grant from the Japanese Urological Association, GSK Japan Research Grant 2015 and the Suzuki Urological Foundation.

Author Contributions

A.S. and H.N. designed the experiments, analysed data and prepared the manuscript. A.S. performed most of the experiments. M.U. generated Bmal1-knockout mice. J.K. and T.S. helped with in vitro experiments. N.N. helped with in vivo experiments. S.K. and K.T. contributed the analysis of bioluminescence experiments. L.S.L. provided TRT-HU1 cells. S.S provided Bmal1flx/flx mice. A.K., M.D., H.O. and O.O. supervised the study. All authors reviewed the manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-20379-0.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Van Hoeck K, Bael A, Lax H, Hirche H, van Gool JD. Circadian variation of voided volume in normal school-age children. Eur. J. Pediatr. 2007;166:579–584. doi: 10.1007/s00431-006-0286-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakamura S, et al. Circadian changes in urine volume and frequency in elderly men. J. Urol. 1996;156:1275–1279. doi: 10.1016/S0022-5347(01)65568-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Witjes WP, Wijkstra H, Debruyne FM, de la Rosette JJ. Quantitative assessment of uroflow: is there a circadian rhythm? Urology. 1997;50:221–228. doi: 10.1016/S0090-4295(97)00190-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Robson WL. Clinical practice. Evaluation and management of enuresis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2009;360:1429–1436. doi: 10.1056/NEJMcp0808009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nevéus T. Diagnosis and management of nocturnal enuresis. Curr. Opin. Pediatr. 2009;21:199–202. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e3283229b12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bosch JL, Weiss JP. The prevalence and causes of nocturia. J. Urol. 2010;184:440–446. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Kerrebroeck P, et al. The standardisation of terminology in nocturia: report from the Standardisation Sub-committee of the International Continence Society. Neurourol. Urodyn. 2002;21:179–183. doi: 10.1002/nau.10053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yoshimura K. Correlates for nocturia: a review of epidemiological studies. Int. J. Urol. 2012;19:317–329. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2011.02956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weiss JP, Blaivas JG, Stember DS, Chaikin DC. Evaluation of the etiology of nocturia in men: the nocturia and nocturnal bladder capacity indices. Neurourol. Urodyn. 1999;18:559–565. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6777(1999)18:6<559::AID-NAU6>3.0.CO;2-D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Osman NI, Chapple CR, Wein AJ. Nocturia: current concepts and future perspectives. Acta. Physiol. (Oxf). 2013;207:53–65. doi: 10.1111/apha.12013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Negoro H, et al. Involvement of urinary bladder Connexin43 and the circadian clock in coordination of diurnal micturition rhythm. Nat. Commun. 2012;3:809. doi: 10.1038/ncomms1812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Negoro H, et al. Role of Rev-erbα domains for transactivation of the connexin43 promoter with Sp1. FEBS Lett. 2013;587:98–103. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.11.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Negoro H, et al. Regulation of connexin 43 by basic fibroblast growth factor in the bladder: transcriptional and behavioral implications. J. Urol. 2011;185:2398–2404. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2011.02.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Imamura M, et al. Basic fibroblast growth factor causes urinary bladder overactivity through gap junction generation in the smooth muscle. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F46–54. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.90207.2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arrighi S. The urothelium: anatomy, review of the literature, perspectives for veterinary medicine. Ann. Anat. 2015;198:73–82. doi: 10.1016/j.aanat.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Khandelwal P, Abraham SN, Apodaca G. Cell biology and physiology of the uroepithelium. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2009;297:F1477–F1501. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00327.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu P, et al. Role of membrane proteins in permeability barrier function: uroplakin ablation elevates urothelial permeability. Am J Physiol. 2002;283:F1200–F1207. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00043.2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Apodaca G. The uroepithelium: not just a passive barrier. Traffic. 2004;5:117–128. doi: 10.1046/j.1600-0854.2003.00156.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Birder L, Andersson KE. Urothelial signaling. Physiol. Rev. 2013;93:653–680. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00030.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sano T, et al. Intravital imaging of mouse urothelium reveals activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase by stretch-induced intravesical release of ATP. Phisol. Rep. 2016;4:e13033. doi: 10.14814/phy2.13033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cockayne DA, et al. Urinary bladder hyporeflexia and reduced pain-related behaviour in P2X3-deficient mice. Nature. 2000;407:1011–1015. doi: 10.1038/35039519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vlaskovska M, et al. P2X3 knock-out mice reveal a major sensory role for urothelially released ATP. J. Nurosci. 2001;21:5670–5677. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.21-15-05670.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rong W, Spyer KM, Burnstock G. Activation and sensitisation of low and high threshold afferent fibres mediated by P2X receptors in the mouse urinary bladder. J. Physiol. 2002;541:591–600. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2001.013469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cockayne DA, et al. P2X2 knockout mice and P2X2/P2X3 double knockout mice reveal a role for the P2X2 receptor subunit in mediating multiple sensory effects of ATP. J. Physiol. 2005;567:621–639. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.088435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Andersson KE. Purinergic signalling in the urinary bladder. Auton. Neurosci. 2015;191:78–81. doi: 10.1016/j.autneu.2015.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Beckel JM, et al. Pannexin 1 channels mediate the release of ATP into the lumen of the rat urinary bladder. J. Physiol. 2015;593:1857–1871. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2014.283119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Negoro H, et al. Pannexin 1 channels play essential roles in urothelial mechanotransduction and intercellular signaling. PloS one. 2014;9:e106269. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nakagomi H, et al. Urothelial ATP exocytosis: regulation of bladder compliance in the urine storage phase. Sci Rep. 2016;6:29761. doi: 10.1038/srep29761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lazarowski ER. Vesicular and conductive mechanisms of nucleotide release. Purinergic Signal. 2012;8:359–73. doi: 10.1007/s11302-012-9304-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mochizuki T, et al. The TRPV4 cation channel mediates stretch-evoked Ca2+ influx and ATP release in primary urothelial cell cultures. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:21257–21264. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.020206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Miyamoto T, et al. Functional role for Piezo1 in stretch-evoked Ca(2)(+) influx and ATP release in urothelial cell cultures. J. Biol. Chem. 2014;289:16565–16575. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M113.528638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Orellana JA, Stehberg J. Hemichannels: new roles in astroglial function. Front Physiol. 2014;5:193. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Patel D, Zhang X, Veenstra RD. Connexin hemichannel and pannexin channel electrophysiology: how do they differ? FEBS Lett. 2014;588:1372–1378. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Timóteo MA, et al. ATP released via pannexin-1 hemichannels mediates bladder overactivity triggered by urothelial P2Y6 receptors. Biochem. Pharmacol. 2014;87:371–379. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2013.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim J, et al. An hTERT-immortalized human urothelial cell line that responds to anti-proliferative factor. In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. Anim. 2011;47:2–9. doi: 10.1007/s11626-010-9350-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Leontieva OV, et al. Hypoxia suppresses conversion from proliferative arrest to cellular senescence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:13314–13318. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205690109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wen H, et al. Urinary metabolite profiling combined with computational analysis predicts interstitial cystitis-associatedcandidate biomarkers. J. Proteome. Res. 2015;14:541–548. doi: 10.1021/pr5007729. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Balsalobre A, Damiola F, Schibler U. A serum shock induces circadian gene expression in mammalian tissue culture cells. Cell. 1998;93:929–937. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)81199-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chapman EJ, et al. Expression of hTERT immortalizes normal human urothelial cells without inactivation of the p16/Rb pathway. Oncogene. 2006;25:5037–5045. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chapman EJ, et al. Integrated genomic and transcriptional analysis of the in vitro evolution of telomerase-immortalized urothelial cells (TERT-NHUC) Genes Chromosomes Cancer. 2009;48:694–710. doi: 10.1002/gcc.20672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang N, et al. Selective inhibition of Cx43 hemichannels by Gap19 and its impact on myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury. Basic Res. Cardiol. 2013;108:309. doi: 10.1007/s00395-012-0309-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abudara V, et al. The connexin43 mimetic peptide Gap19 inhibits hemichannels without altering gap junctional communication in astrocytes. Front. Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:306. doi: 10.3389/fncel.2014.00306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Marpegan L, et al. Circadian regulation of ATP release in astrocytes. J. Neurosci. 2011;31:8342–8350. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.6537-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Womac AD, Burkeen JF, Neuendorff N, Earnest DJ, Zoran ML. Circadian rhythms of extracellular ATP accumulation in suprachiasmatic nucleus cells and cultured astrocytes. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2009;30:869–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2009.06874.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Koyanagi S, et al. Glucocorticoid regulation of ATP release from spinal astrocytes underlies diurnal exacerbation of neuropathic mechanical allodynia. Nat. Commun. 2016;7:13102. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sui GP, et al. Purinergic and muscarinic modulation of ATP release from the urothelium and its paracrine actions. Am. J. Physiol. Renal Physiol. 2014;306:F286–98. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.00291.2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chi Y, et al. Connexin43 hemichannels contributes to the disassembly of cell junctions through modulation of intracellular oxidative status. Redox Biol. 2016;9:198–209. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2016.08.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Chi Y, Gao K, Zhang H, Takeda M, Yao J. Suppression of cell membrane permeability by suramin: involvement of its inhibitory actions on connexin 43 hemichannels. Br. J. Pharmacol. 2014;171:3448–3462. doi: 10.1111/bph.12693. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Burnstock G. Purinergic signalling in the urinary tract in health and disease. Purinergic Signal. 2014;10:103–155. doi: 10.1007/s11302-013-9395-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Burnstock G. Purine-mediated signalling in pain and visceral perception. Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2001;22:182–188. doi: 10.1016/S0165-6147(00)01643-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Negoro H, et al. Pannexin 1 involvement in bladder dysfunction in a multiple sclerosis model. Sci. Rep. 2013;3:2152. doi: 10.1038/srep02152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ihara T, et al. Clock genes regulate the circadian expression ofpiezo1, TRPV4, connexin26, and VNUT in an ex vivo mouse bladder mucosa. PLoS one. 2017;12:e0168234. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0168234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kojima S, Shingle DL, Green CB. Post-transcriptional control of circadian rhythms. J. Cell. Sci. 2011;124:311–320. doi: 10.1242/jcs.065771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Takezawa K, et al. Authentic role of ATP signaling in micturition reflex. Sci. Rep. 2016;6:19585. doi: 10.1038/srep19585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takezawa K, et al. Urothelial ATP signaling: what is its role in bladder sensation? Neurourol. Urodyn. 2017;36:966–972. doi: 10.1002/nau.23099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wu C, et al. Local receptors as novel regulators for peripheral clock expression. FASEB J. 2014;28:4610–4616. doi: 10.1096/fj.13-243295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Birbach A. Use of PB-Cre4 mice for mosaic gene deletion. PLoS One. 2013;8:e53501. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0053501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Shimba S, et al. Deficient of a clock gene, brain and muscle Arnt-like protein-1 (BMAL1), induces dyslipidemia and ectopic fat formation. PLoS One. 2011;6:e25231. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0025231. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Okada Y, et al. Amino‐terminal enhancer of split gene AES encodes a tumor and metastasis suppressor of prostate cancer. Cancer Sci. 2017;108:744–752. doi: 10.1111/cas.13187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yoo SH, et al. PERIOD2::LUCIFERASE real-time reporting of circadian dynamics reveals persistent circadian oscillations in mouse peripheral tissues. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2004;101:5339–5346. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308709101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.