Abstract

The pituitary hormone prolactin (PRL), originally described for its role in lactation, has been implemented in over 300 functions and is produced by multiple cell types outside of the pituitary. Monocyte/macrophages in particular show robust expression of extra-pituitary prolactin (ePRL). While ePRL protein is identical to pituitary PRL and translated from the same gene, tissues outside the pituitary engage an alternative promoter to regulate expression. Many of the factors regulating this expression, however, remain unknown. Here we show that the adrenergic hormones epinephrine and norepinephrine induce PRL expression in the human monocytic cell line THP-1 at physiological concentrations. Furthermore, our experiments show the polarization state of differentiated macrophages can influence their response in vitro, with inflammatory M1 macrophages—common in obese adipose—showing the highest levels of PRL expression compared to other macrophage types. Adrenergic hormones have a clearly defined role in adipocyte lipid metabolism, stimulating lipolysis through hormone sensitive lipase (HSL) induction. Meanwhile, PRL has been shown to stimulate lipogenesis. This highlights ePRL production as a possible factor in obesity. The overall balance of these two signals could play a critical role in determining overall lipid turnover/accumulation in adipose depots where large numbers of adipose tissue macrophages (ATMs) reside.

Introduction

PRL has been implemented in lipid metabolism ever since it’s discovered role in lactation and has been shown to induce lipogenesis in many tissues1,2 and inhibit lipolysis in adipocytes specifically3. More recent clinical studies have shown a correlation between hyperprolactinemia and weight gain in both males and females. Often, this weight gain is resolved when serum PRL levels are returned to normal4,5. The majority of these studies have been performed with pituitary-derived PRL in mind, but ePRL synthesis is prevalent in a variety of tissues across the human body6,7. Of particular interest to lipid metabolism is ePRL production in monocyte/macrophages8, cells that are numerous within adipose tissue. Such paracrine signaling from a local source of PRL—such as ATMs—could have far-reaching implications for the overall biological response of fat depots9.

Because ePRL is controlled by an alternative promoter to that or pituitary PRL, it is only within the last decade that researchers have begun to uncover some of the factors that regulate ePRL expression in monocyte/macrophages10. We propose that a class of molecules particularly relevant to lipid metabolism in adipocytes, the adrenergic hormones (AHs), may play a key role in regulating ePRL in monocytes/macrophages—more specifically in ATMs—and that the polarization state of the macrophages may have a further additive effect. As AH are well defined in stimulating lipolysis through activation of hormone sensitive lipase11, we propose such an ePRL response would oppose AH signaling on adipocytes.

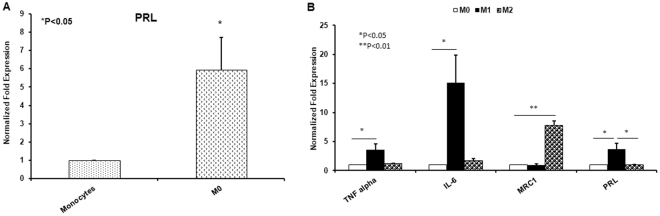

In this study, we set out to determine the effects of dopamine and other catecholamines —such as the AH epinephrine (E) and norepinephrine (NE) —on ePRL in monocytes/macrophages. The effects of L-DOPA and dopamine produced no significant change in overall expression (data not shown); but upon exposure of cells to physiological concentration12,13 of norepinephrine and epinephrine, a dose dependent response occurred in the PRL gene. This response yielded a 4.5-fold increase in expression at 24hrs, at the maximal dose of 100 nM for norepinephrine, and a similar response in epinephrine (Fig. 1). AH exposure consistently increased PRL expression, but the degree to which gene expression was affected varied considerably between trials, with some individual trials yielding no significant change in expression at 100 nM, and others yielding an increase of over 40-fold at the same dose. We attempted to identify possible environmental factors influencing the response by altering conditions such as treatment time of day, confluence, and fetal bovine serum batches, none of which seemed to have a consistent effect on response magnitude. Further research needs to be done to identify other factors influencing the responses magnitude.

Figure 1.

qRT-PCR of PRL gene expression in THP-1 monocytes after 24 hr treatment with norepinephrine or epinephrine.

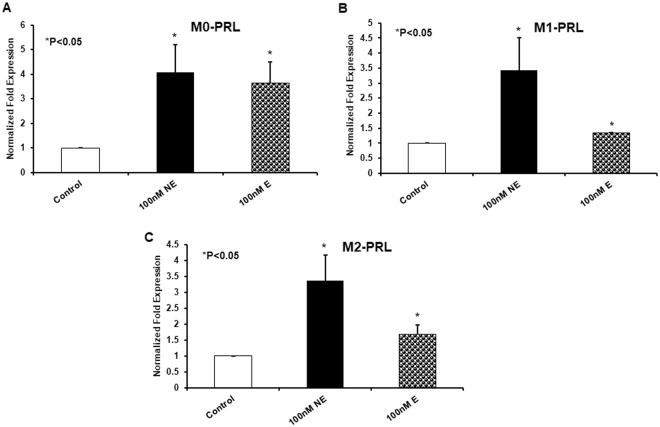

Monocytes will typically leave the bloodstream and take up residence in various tissues as macrophages. Reports show that ATMs display different states of polarization depending on the health of an individual. The ATM population of obese subjects tends to display an M1 polarization and a greater overall number of ATMs to adipose cells. The ATMs of lean individuals, however, display an M2 polarization14. To simulate these populations in vitro, monocytes were exposed to phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) for 72 hours to make “naive” M0 macrophages. Naïve macrophages were then subjected to either lipopolysaccharide (LPS) for 24 hours to form the M1 population, or IL-4 for 24 hours to form the M2 population. Populations were verified via increases in common genetic markers (TNF alpha and IL6 for M1; MRC1 for M2) (Fig. 2B).

Figure 2.

qRT-PCR of basal PRL gene expression in THP-1 monocytes and naïve M0 (A). qRT-PCR for polarization markers and PRL across polarization states.

Before subjecting the populations to AH, we established a baseline for PRL gene expression in each cell type. Our results show a significant and consistent increase in PRL expression as monocytes differentiate into naive macrophages (Fig. 2A). This level of expression remains relatively unchanged as the macrophages polarize to M2. The progression of macrophages to the M1 state, however, is accompanied by a much larger increase in basal PRL gene expression (Fig. 2B).

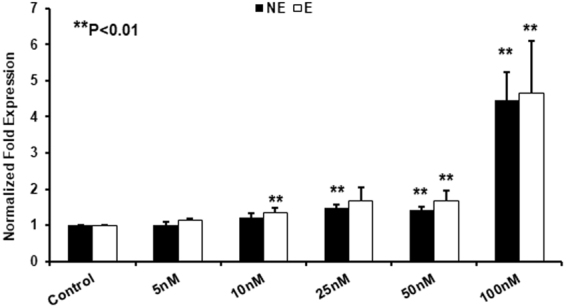

Despite an already elevated basal expression of PRL in macrophages, norepinephrine treatment was still able to illicit an increase in PRL gene expression across all populations. Although M1 and M2 macrophages showed similar fold expression changes in the PRL gene upon AH exposure, overall expression in the M1 population was far higher as the fold expression was being compared to an already elevated basal level (Fig. 3B). Treatment with epinephrine yielded similar, but less drastic results on average when compared to norepinephrine (Fig. 3). The variability in the response noted in monocytes was far less pronounced in macrophages, likely because basal expression was already relatively high before treatment and thus not as susceptible to further increases.

Figure 3.

qRT-PCR of PRL gene expression after 24 hr treatment with norepinephrine or epinephrine in naïve M0 (A), inflammatory M1 (B), and anti-inflammatory M2 (C) monocyte derived macrophages.

Further work will be needed before the full physiological impact of this response can be understood. When considering the traditional roles of both players involved, this balance is likely to have wide-reaching impacts on cellular metabolism. Of particular interest are the opposing roles of the two signals. One of the primary functions of AH in the body is activating hormone sensitive lipase, which breaks down triglycerides to free fatty acids, moving them out of cells and into the bloodstream11,15. PRL, on the other hand, has been closely associated with increases in the body mass index (BMI), which is often corrected in hyperprolactinemia patients whose serum levels are returned to normal5.

With these findings in mind, it is easy to see how the interplay between these two cell signals residing in the adipose can have a strong influence on the overall state of the entire tissue. It is especially concerning considering that ATMs not only shift towards the M1 state in obese patients but also increase in number—accounting for up to 40% of the cells in an adipose depot16. Our findings that PRL expression increases as monocytes differentiate into macrophages could mean that such macrophage influxes could result in overall higher PRL levels, regardless of polarization state and could displace an already delicate balance of lipid mobilization and storage.

Another important aspect of this work is that ePRL production seems to be absent in most mammals. Previous studies have shown that in mice, rats, and most mammal species (outside of the primates), ePRL expression is virtually non-existent10. This was further verified in our lab using both mouse macrophage primary cells and cell lines, in all of which PRL gene expression was undetectable (data not shown). Thus, any impact of such signaling is an important divergence when translating metabolic and immunology research from animal models to humans. This could also help explain the high failure rates in the attempts to do so. Identifying and characterizing such pathways in general will be invaluable in bridging the gap for such translational research. Lastly, PRL has many other well-defined roles that act on immune cells directly, most notably being that of a co-mitogen8.

Seeing as the most well-defined regulator of traditional PRL expression in the pituitary is dopamine, which sharply inhibits its expression17 the paradoxical finding in this study that adrenergic hormones upregulated ePRL expression, necessitates further understanding how its expression is controlled at a local level, particularly in lieu of the involvement of inflammatory macrophages and obesity. Further research is needed to confirm if any of these proposed roles are performed by ePRL; but understanding the factors that regulate its expression is a key step in understanding any of its potential functions. Moreover, considering the already defined rolls of AH and PRL, it is not a stretch to conclude that their influence over each other could have far-reaching implications in general human physiology.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

RPMI-1640, FBS, penicillin-streptomycin, 1× PBS, TRIzol™, and primers were ordered from Life Technologies (Carlsbad, CA). Norepinephrine with bitartrate salt, epinephrine with bitartrate salt, phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA), and lipopolysaccharide from E. coli, were ordered from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). IL-4 from Promega (Madison, WI), Sybr green, Superscript III cDNA kit from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA) were purchased and used.

Cell Culture

The human monocytic cell line THP-1 was used to model both monocytes and macrophages. THP-1 monocytes were differentiated to “naive” macrophages with 50 ng/mL PMA for 72 hrs. The “naive” macrophages were then polarized to either inflammatory “M1” macrophages with 100 ng/mL LPS for 24 hrs or to anti-inflammatory “M2” macrophages with 20 ng/mL IL-4. Cells were maintained in RPMI-1640 supplemented with 10% FBS, 1% penicillin-streptomycin.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from cells using TRIzol™ reagent according to the manufacturer’s instructions; 1 µg of total RNA was used to synthesize cDNA, and quantitative real-time PCR was performed using the CFX96 Touch™ Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad Laboratories, Hercules, CA) with SYBR Green as detection dye. mRNA levels of target genes were normalized to GAPDH.

Statistical analysis

Values are presented as a mean ± standard deviation (SD), and statistical analyses were performed by using student’s t-test, with P < 0.05 as the level of significance.

Author Contributions

Richard Barrett and Dr. Chandrakala Aluganti Narasimhulu performed experiments, Dr. Sampath Parthasarathy was principal investigator who designed and provided overall direction. Richard Barrett wrote manuscript and prepared figures. All authors reviewed manuscript.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Goodridge AG, Ball EG. The effect of prolactin on lipogenesis in the pigeon. In vitro studies. Biochemistry. 1967;6:2335–2343. doi: 10.1021/bi00860a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barber MC, Finley E, Vernon RG. Mechanisms Whereby Prolactin Modulates Lipogenesis in Sheep Mammary-Gland. Horm Metab Res. 1991;23:143–145. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1003636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandebourg TD, Bown JL, Ben-Jonathan N. Prolactin upregulates its receptors and inhibits lipolysis and leptin release in male rat adipose tissue. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2007;357:408–413. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2007.03.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roelfsema F, Pijl H, Keenan DM, Veldhuis JD. Prolactin Secretion in Healthy Adults Is Determined by Gender, Age and Body Mass Index. Plos One. 2012;7:e31305. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Greenman Y, Tordjman K, Stern N. Increased body weight associated with prolactin secreting pituitary adenomas: weight loss with normalization of prolactin levels. Clin Endocrinol. 1998;48:547–553. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2265.1998.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ben-Jonathan N, Mershon JL, Allen DL, Steinmetz RW. Extrapituitary prolactin: distribution, regulation, functions, and clinical aspects. Endocrine reviews. 1996;17:639–669. doi: 10.1210/edrv-17-6-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Marano RJ, Ben-Jonathan N. Minireview: Extrapituitary prolactin: an update on the distribution, regulation, and functions. Molecular endocrinology. 2014;28:622–633. doi: 10.1210/me.2013-1349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sabharwal P, et al. Prolactin synthesized and secreted by human peripheral blood mononuclear cells: an autocrine growth factor for lymphoproliferation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1992;89:7713–7716. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.16.7713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bouckenooghe T, et al. Adipose tissue macrophages (ATM) of obese patients are releasing increased levels of prolactin during an inflammatory challenge: a role for prolactin in diabesity? Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2014;1842:584–593. doi: 10.1016/j.bbadis.2013.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerlo S, Davis JR, Mager DL, Kooijman R. Prolactin in man: a tale of two promoters. BioEssays: news and reviews in molecular, cellular and developmental biology. 2006;28:1051–1055. doi: 10.1002/bies.20468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Steinberg D, Khoo JC. Hormone-Sensitive Lipase of Adipose-Tissue. Fed Proc. 1977;36:1986–1990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rowell LB, Brengelmann GL, Freund PR. Unaltered norepinephrine-heart rate relationship in exercise with exogenous heat. J Appl Physiol (1985) 1987;62:646–650. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1987.62.2.646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Little RA, Frayn KN, Randall PE, Stoner HB, Maycock PF. Plasma catecholamine concentrations in acute states of stress and trauma. Archives of emergency medicine. 1985;2:46–47. doi: 10.1136/emj.2.1.46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Morris DL, Singer K, Lumeng CN. Adipose tissue macrophages: phenotypic plasticity and diversity in lean and obese states. Current opinion in clinical nutrition and metabolic care. 2011;14:341–346. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328347970b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khoo JC, Aquino AA, Steinberg D. Mechanism of Activation of Hormone-Sensitive Lipase in Human Adipose-Tissue. J Clin Invest. 1974;53:1124–1131. doi: 10.1172/JCI107650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Weisberg SP, et al. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI200319246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shaar CJ, Clemens JA. The role of catecholamines in the release of anterior pituitary prolactin in vitro. Endocrinology. 1974;95:1202–1212. doi: 10.1210/endo-95-5-1202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]