Abstract

Sperm chemotaxis toward a chemoattractant is very important for the success of fertilization. Calaxin, a member of the neuronal calcium sensor protein family, directly acts on outer-arm dynein and regulates specific flagellar movement during sperm chemotaxis of ascidian, Ciona intestinalis. Here, we present the crystal structures of calaxin both in the open and closed states upon Ca2+ and Mg2+ binding. The crystal structures revealed that three of the four EF-hands of a calaxin molecule bound Ca2+ ions and that EF2 and EF3 played a critical role in the conformational transition between the open and closed states. The rotation of α7 and α8 helices induces a significant conformational change of a part of the α10 helix into the loop. The structural differences between the Ca2+- and Mg2+-bound forms indicates that EF3 in the closed state has a lower affinity for Mg2+, suggesting that calaxin tends to adopt the open state in Mg2+-bound form. SAXS data supports that Ca2+-binding causes the structural transition toward the closed state. The changes in the structural transition of the C-terminal domain may be required to bind outer-arm dynein. These results provide a novel mechanism for recognizing a target protein using a calcium sensor protein.

Introduction

In many species, the female gamete or its associated structures release chemoattractants to attract spermatozoa. The chemoattractant gradient provides cues that guide sperm chemotaxis toward the egg1. In the sea urchin sperm, after binding of the chemoattractant peptide to its receptor, rapid synthesis of cGMP is induced to activate the K+-selective cyclic nucleotide-gate (KCNG) channel, leading to membrane potential (Em) hyperpolarization. The Em change facilitates the Ca2+ extrusion activity of K+-dependent Na+/Ca2+ exchangers (NCKX) and results in an influx of Ca2+ into the cell2,3. This transient change in the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) is necessary for the directional changes of the sperm flagellum4–7. Spermatozoa from marine invertebrates have been especially used to study the mechanism to control flagellar motility during sperm chemotaxis8–11. The spermatozoa of the ascidian Ciona intestinalis clearly exhibit chemotaxis toward the egg and a transient [Ca2+]i increase in the flagellum accompanying a change of the swimming direction along a chemoattractant gradient field12–14. The sperm keeps straight swimming at lower [Ca2+]i, and higher [Ca2+]i induces asymmetric flagellar bending for the turning motion15,16.

Ca2+ ions activate axonemal dyneins through the phosphorylation of the Txtcx-2-related light chain (LC) of outer-arm dynein and dephosphorylation of an intermediate chain (IC) of inner-arm dynein to induce a change in the flagellar beat, allowing the swimming of sperm along a gradient of the chemoattractant17–20. These responses are mediated by a sharp increase in [Ca2+]i from 10−6 M to 10−4 M21. Studies on dynein-driven microtubule sliding in isolated axonemes have indicated that the calcium signal may be mediated by calmodulin and a calmodulin-dependent kinase22. The dynein light chain from the outer arm of Chlamydomonas flagella was also shown to contain a Ca2+-binding regulatory protein, which is directly associated with the γ dynein heavy chain23. However, the mechanism underlying the Ca2+-dependent regulation of dyneins remains obscure.

Recently, an axonemal Ca2+-binding protein from ascidian C. intestinalis, named calaxin, was demonstrated to bind to a heavy chain (HC) of outer-arm dynein and tubulin in a Ca2+-dependent manner and to be essential for the propagation of Ca2+-induced asymmetric flagellar bending24,25. Based on the amino acid sequence, calaxin belongs to the neuronal calcium sensor (NCS) protein family. Members of this protein family include recoverin and frequenin, which undergo conformational changes upon Ca2+ binding26–29, providing the surfaces to interact with their target proteins. To elucidate the relationship between the Ca2+-dependent regulatory mechanism and structural features of calaxin, we herein solved crystal structures of calaxin in the Ca2+-bound and Mg2+-bound forms. The crystal structure of calaxin shows an open-closed structural transition in both forms, and small-angle X-ray scattering data provides the evidence of structural transition in solution.

Results

Overall structure of calaxin in the Ca2+-bound form

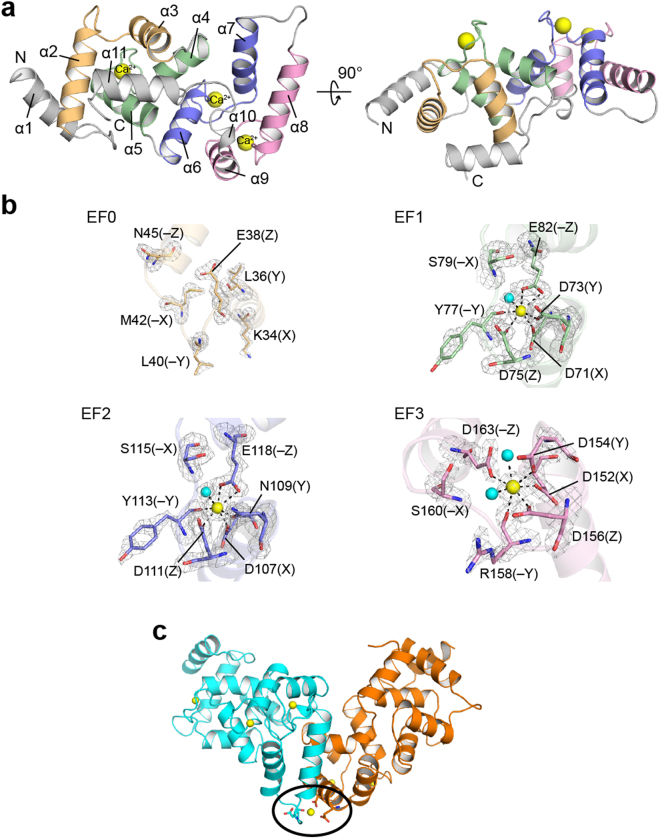

The crystal structure revealed that calaxin was composed of 11 helices (Fig. 1a and Supplementary Table 1) and contained four EF-hand motifs (Fig. 1b). Similarly to other NCS-family proteins, calaxin can be divided into two domains: the N-terminal domain and the C-terminal domain. In the N-terminal domain, EF0 (residues 23–55) interacted with EF1 (residues 60–92), and EF2 (residues 95–129) and EF3 (residues 137–170) formed the C-terminal domain (α6 through α10 helices) by interacting with each other. Both domains adopted their respective hydrophobic pockets, and the extended α11 helix was accommodated in the hydrophobic pocket of the N-terminal domain.

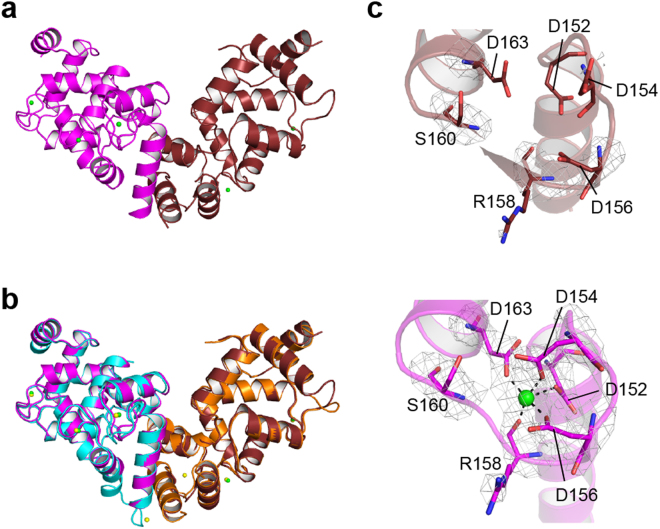

Figure 1.

Structure of the Ca2+-bound form of calaxin. (a) Ribbon diagrams of the overall structure of calaxin in the Ca2+-bound open state. EF0, EF1, EF2 and EF3 are shown in light orange, pale green, slate and pink, respectively. Ca2+ ions are indicated by a yellow sphere model. (b) Close-up view of individual EF-hands binding a Ca2+ ion. Ca2+-binding residues are shown as a stick model. Ca2+ ions and water molecules are indicated by yellow and cyan spheres, respectively. The coordination bonds with Ca2+ ions are highlighted with dashed lines. The Fo − Fc omit maps of EF1, EF2 and EF3 are shown as gray meshes contoured at 3σ. (c) Calaxin dimer in the open state (cyan) and the closed state (orange) in an asymmetric unit. Ca2+ ions are represented as yellow spheres. Side chains coordinating Ca2+ between dimers are represented as sticks (surrounded by a black circle).

The classical EF-hand is characterized by a sequence of 12 residues involved in Ca2+ binding. In calaxin, EF1 and EF2 were composed of the conserved residues for Ca2+ binding that are generally observed as D, D/N, D/N and E at the positions X, Y, Z and −Z, respectively (Fig. 1b)30. These residues formed five coordinate bonds with Ca2+, including bidentate coordination by Glu. The position −Z of EF3 was substituted by Asp, which coordinates Ca2+ ion in a monodentate manner (Fig. 1b). In this type of EF-hand, the shorter side chain of Asp at the position −Z changes the angle of the canonical loop residue, resulting in a smaller and more compact Ca2+ binding motif31. By contrast, no characteristic residues are observed in EF0 (Supplementary Fig. 1), resulting in an impaired capacity to bind Ca2+ as shown in the crystal structure of calaxin (Fig. 1a and b). Among three Ca2+-bound EF hands, only EF2 has a Gly112 at the position between Asp111 (Z) and Tyr113 (−Y). The Gly residue of this position is known to be compatible to the bend of the loop region after position Z32, indicating that EF2 might allow its conformational changes upon Ca2+ binding (Fig. 1b and Supplementary Fig. 1). Moreover, we found that another Ca2+ ion is bonded between two calaxin molecules in an asymmetric unit (Fig. 1c). This Ca2+ coordination may contribute to stabilize the crystal packing.

Conformational differences between two calaxin molecules in an asymmetric unit

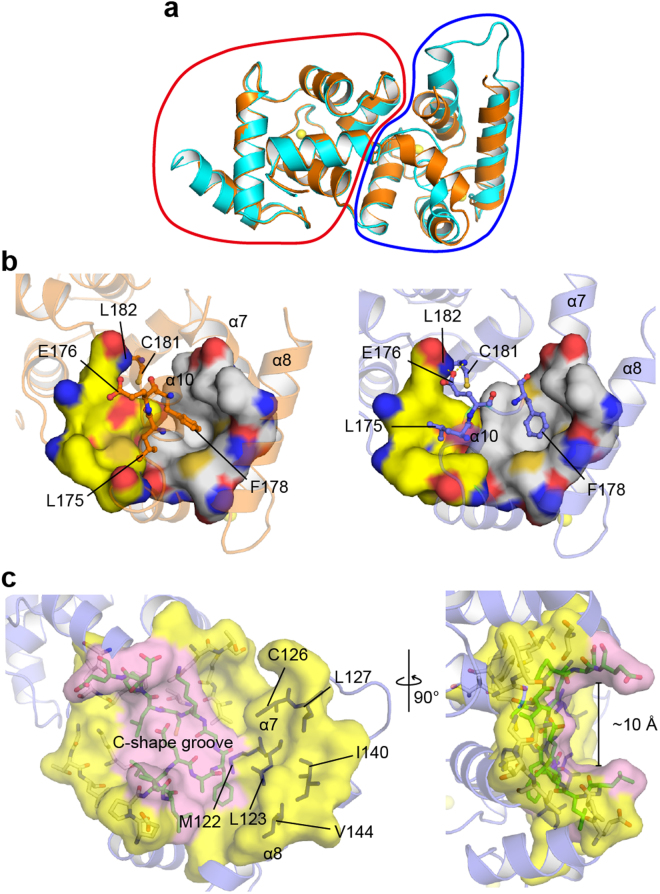

We found that the crystal structure adopts the different conformations in the C-terminal domains between two calaxin molecules in an asymmetric unit: One molecule is in the open state and the other is in the closed state (Fig. 2a). Compared with the open state, the closed state exhibited the inward movement of the α7 and α8 helices and reduced the exposure of the hydrophobic surface formed by the α7, α8 and α10 helices (Met122, Leu123, Cys126, Leu127, Ile140 and Val144) (Fig. 2b and c). Unlike the C-terminal domain, the N-terminal domain showed little structural difference between the open and closed states (Fig. 2a). Another conformational change was observed at the α10 helix. The residues (from Phe172 to Cys181), which formed a 3-turn helix in the closed state, relaxed the helical structure, resulting in a 1-turn helix and a longer loop between the α10 and α11 helices in the open state (Fig. 2b). The side chain of Phe178, which is located in the α10 helix, was accommodated in the hydrophobic surface formed by the α7, α8 and α10 helices in both the closed and open states. Phe178 was dragged by the movement of the α7 and α8 helices, which relaxed a part of the α10 helix in the conformational transition to the open state and induced a C-shaped groove with a width of ~10 Å (Fig. 2c). Furthermore, Glu176 also formed hydrogen bonds with the main-chain imino groups of Cys181 and Leu182 in the open state, resulting in the stabilization of the loop between the α10 and α11 helices in the open state. Two molecules in the open and closed states contacted each other using the α7 and α8 helices in the crystals (Supplementary Fig. 2). This contact may be due to crystal packing, resulting in the appearance of the open and closed states in an asymmetric unit. The simultaneous existence of both states in the Ca2+-bound form as crystal structures indicates that the driving force of Ca2+ binding to calaxin may be insufficient to move the α7 and α8 helices and induce the conformational change of the α10 helix.

Figure 2.

Structural basis for the open-closed transition of calaxin. (a) Structural comparison between the open state (cyan) and closed state (orange) in the Ca2+-bound form. The N-terminal domains and C-terminal domains are circled by a red line and a blue line, respectively. (b) Structures of Ca2+-bound calaxin in the closed (left) and open (right) states. Stick models indicate the residues critical for the twist of EF-hand motifs in the process of the open-closed transition. Hydrophobic holes for F178 and L175 binding are indicated by white and yellow surfaces, respectively. (c) Exposed surface of calaxin in the open state. The C-shaped groove (pink surface) is highlighted in pink, and residues forming the groove are colored green. Residues on the exposed surface and twisted helices are shown by magenta sticks and slate ribbon, respectively.

EF2 and EF3 play pivotal roles in the conformational change between the open and closed states

To characterize the conformational differences in the EF-hands, we measured the interhelical angles between the E-helix and F-helix in each EF-hand (Table 1). EF0 and EF1, which reside in the N-terminal domain, showed slight changes in the interhelical angle between the open and closed states. However, EF2 and EF3 induced a significant change in the interhelical angle in the transition from the closed state to open state, corresponding to the large conformational change in the C-terminal domain (Fig. 2a). This implies that EF2 and EF3 contribute to produce the driving force to convert between the open and closed states.

Table 1.

Interhelical angle between the E-helix and F-helix in each EF-hand of Ca2+-bound calaxin.

| EF-hand | open state (°) | closed state (°) | open state − closed state (°) |

|---|---|---|---|

| EF0 | 63.38 | 67.01 | −3.63 |

| EF1 | 58.01 | 61.82 | −3.81 |

| EF2 | 91.41 | 72.48 | 18.93 |

| EF3 | 94.26 | 80.31 | 13.95 |

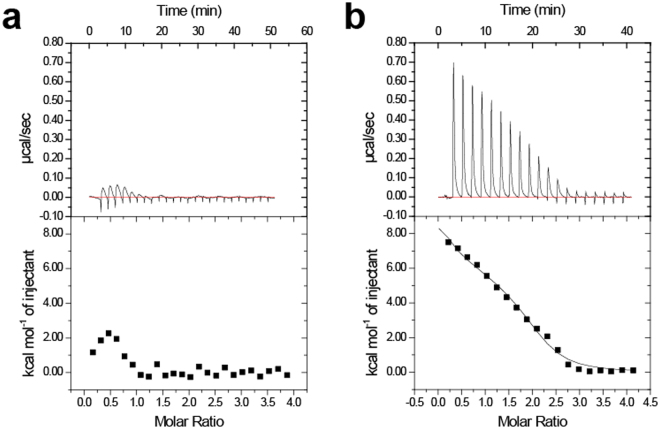

To validate the importance of EF2 and EF3, we performed isothermal titration calorimetry experiments using two mutants, E118A and D163A (in the −Z position of EF2 and EF3, respectively) (Fig. 3). Some studies have reported that EF-hand proteins show large enthalpy changes by Ca2+ titration33,34. Regarding calaxin, it has previously been reported that Ca2+ binding to WT at 4 °C exhibits an endothermic enthalpy change25. E118A and D163A are predicted to be disabled for Ca2+ binding to each EF-hand. Ca2+ titrations to D163A represent endothermic binding similar to that of WT. However, Ca2+ binding to E118A showed a remarkably lower endothermic heat, indicating that the loss-of-function mutation in EF2 extinguishes the ability of the other EF-hand to bind Ca2+. The circular dichroism spectroscopy showed that both E118A and D163A mutants retained their secondary structures despite respective mutation (Supplementary Fig. 3). The results indicate that E118A mutation affects the sensitivity of calaxin to Ca2+ ions without the disruption of the native conformation.

Figure 3.

Isothermal titration calorimetry of Ca2+ binding to the EF2-defective E118A mutant (a) and EF3-defective D163A mutant (b).

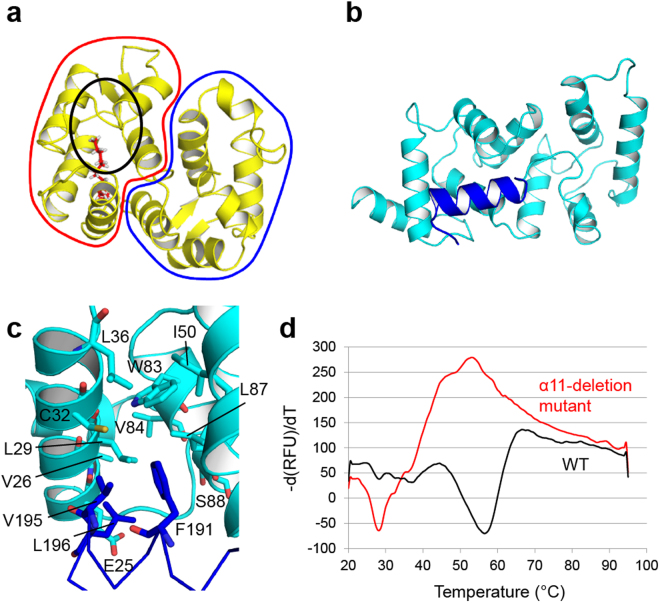

The α11 helix contributes to the thermostability of calaxin in the Ca2+-bound form by hydrophobic interaction

NCS-family proteins have an N-terminal myristoylation motif, such as recoverin, and the myristoyl group is buried in the hydrophobic pocket in the Ca2+-free form (apo form or Mg2+-bound form) (Fig. 4a). Calaxin has no myristoylation motif in the N-terminus. Instead, in the crystal structure of calaxin, the hydrophobic core in the N-terminal domain interacted with hydrophobic residues (Phe191, Val195 and Leu196) on the α11 helix (Fig. 4b and c). To assess the role of the α11 helix, we prepared an α11-deletion mutant (residues 1–182) and analyzed the thermostability of WT and this mutant in the Ca2+-bound forms using the fluorescence-based thermal stability assay (Fig. 4d). The first derivative curve showed the melting temperature (Tm) for WT and mutant calaxin. The first derivative curve of WT showed a large melting peak at 56 °C. However, the α11-deletion mutation caused a remarkable decrease in the melting peak (Tm = 28 °C). Furthermore, the first derivative curve of the mutant showed a wide positive peak near 50 °C, indicating aggregation. Although the thermal stability was decreased, the protein folding was hardly affected by the α11-deletion compared to WT (Supplementary Figs 3 and 4). The results indicate that the hydrophobic interaction of the α11 helix with the N-terminal domain contributes to the thermostability of calaxin in the Ca2+-bound form.

Figure 4.

Contribution of the α11 helix to the thermostability of calaxin. (a) Solution structure of recoverin in the Ca2+-free state (PDB ID: 1IKU). The N-terminal domain and C-terminal domain are surrounded by a red line and a blue line, respectively. The N-terminal myristoyl group is depicted in red sticks. The black circle shows the hydrophobic pocket interacting with the myristoyl group. (b) Crystal structure of Ca2+-bound calaxin in the open state. The α11 helix is colored in blue. (c) Hydrophobic interaction between the C-terminal α11 helix and N-terminal domain. The α11 helix is depicted in blue lines, and its hydrophobic residues (F191, V195 and L196) are shown as blue sticks. Residues forming the hydrophobic core in the N-terminal domain are depicted as cyan sticks. (d) Fluorescence-based thermal stability assay.

Comparison of the structures between the Ca2+-bound and Mg2+-bound forms

To clarify the structural features in Ca2+-bound form, we determined the crystal structure of calaxin in the Mg2+-bound form and compared the structures between these forms. Although calaxin in the Mg2+-bound form was purified in the presence of 100 mM magnesium chloride, the crystallizing conditions contained 10 mM barium chloride. We used isothermal titration calorimetry to determine which ion was bound in calaxin. Titrations of Ba2+ to calaxin in the presence of Mg2+ showed no heat, indicating that Mg2+ bound to calaxin was not replaced by Ba2+ (Supplementary Fig. 5). In addition, the anomalous signals of Ba2+ ions were not observed (Supplementary Fig. 6). Therefore, we obtained the crystal structure of Mg2+-bound calaxin.

The crystal structures are similar between the Ca2+-bound and Mg2+-bound form (RMSD 0.516 Å), and the open and closed states were observed also in the Mg2+-bound form, supporting that Ca2+ is insufficient for the driving force to convert between the open and closed states (Fig. 5a and b). Mg2+ ions in EF1 and EF3 are liganded with octahedral coordination geometry in the open state, due to lack of the monodentate binding at −Z position as compared with Ca2+ ions, which is attributed to the difference of the ionic radii between Mg2+ and Ca2+. However, no electron density of Mg2+ was observed in EF3 of the closed state, and the side chains of the loop between E-helix and F-helix, especially Asp152 and Asp154, seem to be flexible because of poor electron density (Fig. 5c). These data indicate that the affinity of EF3 for Mg2+ is different between the open and closed states: Mg2+ prefers to bind to the open state over the closed state.

Figure 5.

Structure of the Mg2+-bound form of calaxin. (a) Overall structure of calaxin in the Mg2+-bound form. The open state and closed state are depicted in magenta and ruby, respectively. Mg2+ ions are shown in green spheres. (b) Structural comparison between the Ca2+-bound forms (open state: cyan, closed state: orange) and Mg2+-bound forms (open state: magenta, closed state: ruby) of calaxin. (c) Enlarged views of EF3 in the open state (lower pannel) and closed state (upper panel). The Fo − Fc omit maps of the open and closed states are shown as gray meshes contoured at 3σ.

Changes in structural transition between the Ca2+-bound and Mg2+-bound forms in solution

To evaluate the conformation of calaxin in the Ca2+ and Mg2+-bound forms in solution, we carried out small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS) experiments in the presence of Ca2+ or Mg2+ ion. Based on the Guinier plots (Supplementary Fig. 7), the radius of gyration (Rg) was 19.3 and 20.2 Å for Ca2+ and Mg2+-bound forms, respectively. These data show that calaxin exists a monomer in the both states. We further estimated the population of open and closed conformers under equilibrium in solution by fitting the intrinsic scattering curves, which were theoretically calculated with crystal structures of the two states of calaxin, to experimental scattering curves of the Ca2+ and Mg2+-bound calaxin (Fig. 6). Fraction of the open state with the lowest R factor was 0.18 in the presence of Ca2+ ion, which shows that calaxin adopts the closed and open sates with abundance ratio of 18% and 82% in the Ca2+-bound form, respectively. In contrast, the existing rate of Mg2+-bound calaxin was limited to only open state (100%). These results suggest that the Ca2+ binding functions to shift open-closed structural transition toward the closed state. In addition, the open state may be stabilized by a selective binding of Mg2+ to EF3 in the absence of Ca2+ ion.

Figure 6.

Structural transition between the open and closed state of calaxin observed in SAXS experiments. (a) Experimental (blue circles) and calculated (fraction of closed state = 0.18) (red line) scattering curves of Ca2+-bound calaxin. (b) Experimental (blue circles) and calculated (fraction of closed state = 0.00) (red line) scattering curves of Mg2+-bound calaxin.

Discussion

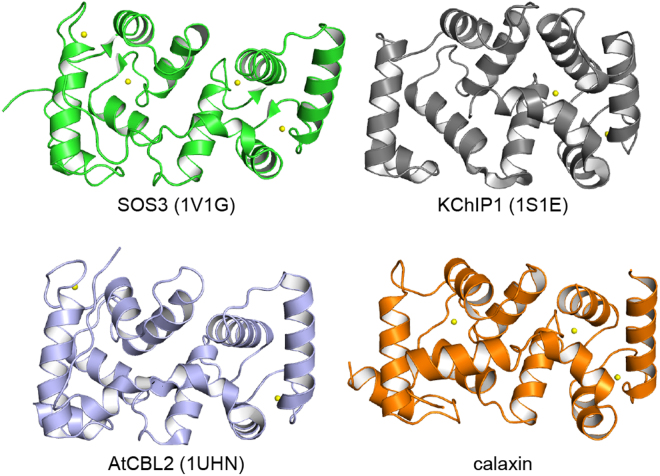

In the typical target-recognition mechanism of NCS-family proteins, Ca2+ binding to a protein induces the extrusion of the N-terminal myristoyl group, which sequesters the hydrophobic groove and covers up the target binding site in the closed state (Supplementary Fig. 8a). This conformational change results in the exposure of residues interacting with the target proteins26–29. However, there is no myristoylation motif in the N-terminus of calaxin24. Several structures of NCS-family proteins have also been determined and are similar to the structure of calaxin (Fig. 7). The C-terminal regions of the NCS-family proteins provide the surface to receive the target protein in the Ca2+-bound form, such as KChIP135 and AtCBL236 (Supplementary Fig. 8b and c). In contrast to these typical NCS-family proteins, calaxin shows an open-closed transition state in the Ca2+-bound form. In the closed state, the exposure of the hydrophobic surface of calaxin is reduced by the movement of the α7 and α8 helices instead of the movement of the N-terminal myristoyl group or C-terminal region in the other NCS-family proteins. Typical NCS-family proteins receive the α-helical structure of target proteins with the induced surfaces of the Ca2+-bound forms. Therefore, the Ca2+-induced surface in the C-terminal domain of calaxin may participate the interaction with dynein, whose structure is largely composed of α-helices37.

Figure 7.

Crystal structures of Ca2+-bound NCS-family proteins. Structural comparison among NCS-family proteins, SOS3 (PDB ID: 1V1G), KChIP1 (PDB ID: 1S1E), AtCBL2 (PDB ID: 1UHN) and calaxin in the closed state. Yellow spheres indicate Ca2+ ions.

EF-hand proteins are known to change the conformation and metal-binding pattern between the Ca2+-bound and Mg2+-bound forms30,38,39. However, calaxin in the Mg2+-bound form shows a similar structure to that of the Ca2+-bound form, indicating that the conformational transition between the Ca2+-bound and Mg2+-bound forms is insignificant and that the effect of the crystal packing may surpass that of the conformational transition. Interestingly, we found that EF3 has a lower affinity for Mg2+ in the closed state due to incompatible arrangements of the acidic residues (Fig. 5c), whereas Ca2+ induces the same arrangements of the EF3 both in the closed and open states. These structural differences in the Ca2+- and Mg2+-bound forms indicate the possibility that calaxin in the Ca2+-bound form is more compatible with the conformational change than the Mg2+-bound form. Moreover, SAXS data supports that Ca2+-binding promotes the open-closed structural transition toward the closed state (Fig. 6). A transient [Ca2+]i is increased up to 10−4 M in the process of the directional changes of sperm movement21. In addition to the Ca2+ binding to the EF-hands causing structural transition, the interaction with outer-arm dynein may be essential to complete the conformational change of calaxin.

In the crystal structure of AtCBL2, which is a member of the NCS protein family, the helices in the C-terminal domain form the hydrophobic crevice and accommodate the regulatory domain of AtCIPK14 (Supplementary Fig. 8c)36. Furthermore, Ca2+ ions are bound by AtCBL2 with and without AtCIPK14, supporting that a conformational transition between the ligand-bound and ligand-free forms can occur in other NCS-family proteins, including calaxin, when the proteins adopt their Ca2+-bound states. However, the binding patterns of Ca2+ ions are different between the ligand-bound and ligand-free forms of AtCBL2. All four EF-hands are filled with Ca2+ ions in the ligand-bound form, whereas Ca2+ ions bind only to the first and fourth EF-hands in ligand-free form. On the other hand, opposite Ca2+ binding patterns are shown in the structure of SOS3 complexed with SOS2. SOS3 in the SOS2-bound form binds Ca2+ ions only at the first and fourth EF-hands, although all four EF-hands are occupied with Ca2+ ions in the SOS2-unbound form40. Calaxin adopts both its open state and closed state in the same Ca2+-binding pattern in which three Ca2+ ions are coordinated to EF1, EF2 and EF3, indicating that its open-closed transition is independent of the Ca2+-binding pattern.

Dynein family proteins use a common principle to generate movement in which they bind to their track, undergo a force-producing conformational change, are released from the track and then return to their original conformation. Therefore, corresponding to the action of dynein family members, conformational change will help calaxin recognize dynein effectively. Although the core structures constituted by four EF-hands (α2 through α9) are similar among NCS-family proteins, their C-terminal helices and loops of each protein adopt various conformations (Supplementary Fig. 9). This indicates that the conformational differences in the C-terminal helices are involved in the selectivity of NCS-family proteins toward associating partners. Also, our fluorescence-based thermal stability assay demonstrated that the C-terminal helix of calaxin contributes the conformational stability by interaction with the hydrophobic core in the N-terminal domain. Although further demonstration requires the identification of the target binding region of dynein and subsequent structural analyses of calaxin complexed with dynein or its target region, our findings provides a plausible conformational change consistent with outer-arm dynein mechanism of the calaxin-mediated regulation of dynein induced by a transient [Ca2+]i increase.

Materials and Methods

Expression and Purification of Ca2+-bound and Mg2+-bound Calaxin

For the preparation of calaxin (UniProt ID: Q8T893), the calaxin gene was cloned at NdeI and BamHI sites of the pET-28a vector (Novagen), and the vector was transformed to the Escherichia coli K12 strain KRX cells (Promega). The cells were grown in Lysogeny Broth (LB) medium containing 30 μg mL−1 kanamycin at 37 °C. After the addition of 0.1% L-rhamnose (Wako) at an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.6, the cell culture was further incubated at 20 °C for 18 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 2,290 × g for 15 min at 4 °C. The pellet was resuspended in sonication buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl and 10 mM imidazole. After sonication, the suspension was centrifuged at 40,000 × g for 30 min at 4 °C to remove cell debris and insoluble fractions. The supernatant was loaded onto a His-tag affinity column prepared by filling a 20-mL chromatography column (BioRad) with Ni Sepharose 6 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare). After the column was washed with washing buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl and 50 mM imidazole, calaxin was eluted with elution buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 300 mM NaCl and 250 mM imidazole. Thrombin was added to the eluted protein to remove the N-terminal His-tag, and the protein solution was then dialyzed overnight against chelate buffer containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM DTT and 1 mM EDTA. The solution was further dialyzed against 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM DTT and 1 mM CaCl2 to prepare the calcium binding protein. The protein was purified using a Resource Q (GE Healthcare) anion exchange column equilibrated with equilibration buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 1 mM DTT and 1 mM CaCl2 and was eluted by increasing the NaCl concentration from 0 to 500 mM in the equilibration buffer. For the preparation of Mg2+-bound calaxin, the protein solution was dialyzed against 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 20 mM MgCl2 and 1 mM DTT. Furthermore, the dialyzed Mg2+-bound calaxin was eluted with a 0 to 300-mM NaCl gradient from a Resource Q column, followed by buffer exchange with a Superdex 75 10/300 HR (GE Healthcare) column using 10 mM MES-NaOH (pH 6.0), 100 mM MgCl2, 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM DTT.

Crystallization, Data Collection and Structure Determination

Crystallization of the Ca2+-bound protein was performed using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method. Each sitting drop was prepared by mixing the protein solution (0.75 μL) with the equal volume of reservoir solution (0.75 μL) containing 0.1 M MES (pH 6.4), 0.2 M calcium acetate and 17.5% PEG8000 and then was equilibrated against the reservoir solution at 20 °C. The concentration of protein for crystallization was 10 mg mL−1, and 24% ethylene glycol was used as the cryoprotectant. The X-ray diffraction data were collected with an in-house X-ray diffractometer equipped with an FR-E SuperBright X-ray generator and an R-AXIS VII imaging plate. For crystallographic phasing, the crystal was soaked in a solution containing 0.1 M MES (pH 6.2), 10 mM SmCl3 and 16% PEG8000, and the single anomalous diffraction (SAD) data were collected at the samarium peak wavelength of 1.6 Å on the BL-17A beamline at Photon Factory (Tsukuba, Japan).

The collected data sets were indexed and integrated using XDS41, and were scaled using XSCALE41. Experimental phasing was performed with the SAD data and the program package autoSHARP42. The initial Model was automatically built with ARP/wARP43 in the CCP4 suite44. After automatic modeling, manual model building was carried out with Coot45, and Refmac546 was used for the refinement of the obtained model. To determine the structure of Ca2+-bound protein, the molecular replacement method was carried out using Molrep47 and the samarium-bound structure as a template. Model building and refinement were performed using Coot and Refmac5, respectively. The quality of the models was verified by PROCHECK48. The images of the protein structure were created by PyMol (http://www.pymol.org/). The sequence alignment and visualization were performed using ClustalW and ESPript, respectively.

Crystallization of the Mg2+-bound protein was also performed using the sitting drop vapor diffusion method at 20 °C by mixing 0.3 μL of 12 mg mL−1 protein solution with 0.3 μL of reservoir solution (containing 0.2 M ammonium sulfate, 0.1 M MES, pH 6.3, 26% (w/v) PEG 5000 MME and 10 mM barium chloride). The X-ray diffraction data were collected at a wavelength of 1.0 Å at Photon Factory beamline AR-NW12A. The data were indexed and integrated with XDS41, and were scaled with AIMLESS49. The crystal structure of Mg2+-bound calaxin was determined by Molrep using the structure of the Ca2+-bound calaxin without Ca2+ ions as a template model. Coot was used for model building, and Phenix.refine50 and Refmac5 were used for refinement. Twin refinement was applied because twinning fraction of structure factor data for Mg2+-bound calaxin was 0.155.

Preparation of Mutant Proteins

Two mutant proteins (E118A and D163A) were prepared for isothermal titration calorimetry experiments. The expression vectors were created using PrimeSTAR Max DNA Polymerase (Takara), the expression vector for wild-type protein as a template and primers (Supplementary Table 2). The protein expression and purification were carried out with the same procedure as that of the wild type.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) Experiments

ITC experiments were carried out using an iTC200 calorimeter (GE Healthcare) at 4 °C. The protein solutions were prepared in aqueous buffer containing 25 mM MOPS-KOH (pH 7.8), 1 mM DTT and 200 mM NaCl. Calcium titrations were carried out with 1 mM CaCl2 and a 50-μM protein solution. The experiments were carried out with each injection consisting of 1.5 μL of the titrant against 200 μL of the protein solution. Data analysis was performed using Origin 7 software. The titration curve of the D163A mutant was fitted using a two sequential binding model. Barium titrations were carried out using 0.8 mM BaCl2 and a 35-μM calaxin solution in the buffer containing 25 mM MOPS-KOH (pH 7.8), 1 mM DTT, 200 mM NaCl and 1 mM MgCl2. Data analysis was conducted in the same way as that for Ca2+ titrations.

Fluorescence-based thermal stability assay

The assay was carried out using the CFX Connect Real-Time System (Bio-Rad) as previously described51. The sample solutions were prepared by mixing 2.22 μL of 100× SYPRO Orange (Life Technologies) and 20 μL of 0.3 mg/mL calaxin solution (20 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT and 1 mM CaCl2). Each sample was heated from 20 to 95 °C in increments of 0.5 °C.

Circular dichroism measurements

Wild type calaxin and its mutants (E118A, D163A and the α11-deletion mutant) were analyzed by circular dichroism to compare their secondary structures. The decalcified WT, E118A and D163A samples (11 μM) were prepared in a buffer of 25 mM MOPS-KOH (pH 7.8) and 1 mM DTT, and the α11-deletion mutant (11 μM) was prepared in a buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT and 1 mM CaCl2. The measurements were performed at room temperature by using a Jasco J-720 spectropolarimeter (WT, E118A and D163A) and a Jasco J-820 spectropolarimeter (the α11-deletion mutant) with a quartz cuvette of 0.1 cm path length. CD spectra were recorded and analyzed between 200–260 nm.

Small-angle X-ray scattering experiments and analyses

The SAXS experiments were carried out on beamline BL-10C at the Photon Factory. All data were collected using X-ray of wavelength of 1.488 Å with a PILATUS3 2 M detector (Dectris) and processed with the FIT2D program (http://www.esrf.eu/computing/scientific/FIT2D/). The sample-to-detector distance was 1.0 m. Equilibrium experiments were performed at 25 °C. The SAXS intensities were accumulated for a total of 30 s by repeating the measurements for a period of 1.0 s each time in order to ensure enough statistical precision. X-ray scattering data were obtained from protein and the corresponding buffers. The scattering data of the buffers were subtracted from those of the protein solutions. X-ray scattering data were analyzed by Guinier approximation, as assuming an exponential dependence of the scattering intensity on h2, where h = 4πsinθ/λ and θ is half of the scattering angle52. Rg and zero angle scattering intensity I(0) were determined using Guinier approximation52. Molecular weight was determined from I(0) by measuring bovine serum albumin (BSA) as a calibration standard53. The sample concentrations of calaxin were 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 and 1.75 mg/mL for the Ca2+-bound form and 0.25, 0.5, 1.0 and 2.0 mg mL−1 for the Mg2+-bound form. The samples of the Ca2+- and Mg2+-bound forms were prepared in 20 mM Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 150 mM NaCl and 1 mM DTT containing 10 mM CaCl2 and MgCl2, respectively.

The intrinsic scattering intensities of open and closed conformers were theoretically calculated from atomic coordinates of their crystal structures by CRYSOL54 program for default parameter settings. The scattering intensity Icalc(h) of equilibrium mixture of open and closed forms with a ratio of (1 − α): α was expressed as:

where Iopen(h) and Iclosed(h) are intrinsic scattering intensities of open and closed conformers, respectively. We evaluated optimal value of α, fraction of the closed conformer under equilibrium in solution, which yielded the lowest R factor such as:

where Iobs(h) is the experimental scattering intensity, and k is the scaling factor between observed and calculated scattering intensities as:

Data Availability

The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 5X9A and 5YPX).

Electronic supplementary material

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the beamline staff at Photon Factory. The synchrotron radiation experiments were performed at BL-17A, AR-NW12A and BL-10C in the Photon Factory, Tsukuba, Japan (2010G640, 2013G654 and 2016R-56). This work was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (S) from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS) for M.T.

Author Contributions

M.T. and K.I. designed the research; T.S., F.H., Y.T. and Y.M. performed the experimental research; T.S., F.H., Y.M., M.O., A.N., K.M., M.K. and T.M. analyzed the data; T.S., F.H., K.I., M.K, T.M. and M.T. wrote the paper; M.T. edited the paper. T.S., H.F. and Y.T. contributed equally to this work.

Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Electronic supplementary material

Supplementary information accompanies this paper at 10.1038/s41598-018-19898-7.

Publisher's note: Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Eisenbach M, Giojalas LC. Sperm guidance in mammals – an unpaved road to the egg. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2006;7:276–285. doi: 10.1038/nrm1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strünker T, et al. A K+-selective cGMP-gated ion channel controls chemosensation of sperm. Nat. Cell Biol. 2006;8:1149–1154. doi: 10.1038/ncb1473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gauss R, Seifert R, Kaupp UB. Molecular identification of a hyperpolarization-activated channel in sea urchin sperm. Nature. 1998;393:583–587. doi: 10.1038/31248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Morisawa M. Cell signaling mechanisms for sperm motility. Zool. Sci. 1994;11:647–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darszon A, Guerrero A, Galindo BE, Nishigaki T, Wood CD. Sperm-activating peptides in the regulation of ion fluxes, singal transduction and motility. Int. J. Dev. Biol. 2008;52:595–606. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.072550ad. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaupp UB, Kashikar ND, Weyand I. Mechanisms of sperm chemotaxis. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2008;70:93–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.70.113006.100654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Guerrero A, Wood CD, Nishigaki T, Carneiro J, Darszom A. Tuning sperm chemotaxis. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2010;38:1270–1274. doi: 10.1042/BST0381270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shingyoji C, Murakami A, Takahashi K. Local reactivation of Triton-extracted flagella by iontophoretic application of ATP. Nature. 1977;265:269–270. doi: 10.1038/265269a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kamimura S, Kamiya R. High-frequency nanometer-scale vibration in ‘quiescent’ flagellar axonemes. Nature. 1989;340:476–478. doi: 10.1038/340476a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ogawa K, Mohri H. A dynein motor superfamily. Cell Struct. Funct. 1996;21:343–349. doi: 10.1247/csf.21.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gibbons BH, Baccetti B, Gibbons IR. Live and reactivated motility in the 9 + 0 flagellum of Anguilla sperm. Cell Motil. 1985;5:333–350. doi: 10.1002/cm.970050406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller RL. Chemotaxis of the spermatozoa of Ciona interstinalis. Nature. 1975;254:244–245. doi: 10.1038/254244a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yoshida M, Inaba K, Morisawa M. Sperm chemotaxis during the process of fertilization in the ascidians Ciona savignyi and Ciona intestinalis. Dev. Biol. 1993;157:497–506. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1993.1152. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shiba K, Baba SA, Inoue T, Yoshida M. Ca2+ bursts occur around a local minimal concentration of attractant and trigger sperm chemotactic response. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2008;105:19312–19317. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0808580105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cook SP, Brokaw CJ, Muller CH, Babcock DF. Sperm chemotaxis: Egg peptides control cytosolic calcium to regulate flagellar responses. Dev. Biol. 1994;165:10–19. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Nishigaki T, et al. A sea urchin egg jelly peptide induces as cGMP-mediated decrease in sperm intracellular Ca2+ before its increase. Dev. Biol. 2004;272:376–388. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2004.04.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Inaba K, Morisawa S, Morisawa M. Proteasomes regulate the motility of salmonid fish sperm through modulation of cAMP-dependent phosphorylation of an outer arm dynein light chain. J. Cell Sci. 1998;111:1105–1115. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.8.1105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Inaba K, Kagami O, Ogawa K. Tctex2-related outer arm dynein light chain is phosphorylated at activation of sperm motility. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1999;256:177–183. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1999.0309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nomura M, Inaba K, Morisawa M. Cyclic AMP- and calmodulin-dependent phosphorylation of 21 and 26 kDa proteins in axoneme is a prerequisite for SAAF-induced motile activation in ascidian spermatozoa. Dev. Growth Differ. 2000;42:129–138. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.2000.00489.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hozumi A, Padma P, Toda T, Ide H, Inaba K. Molecular characterization of axonemal proteins and signaling molecules responsible for chemoattractant-induced sperm activation in Ciona intestinalis. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton. 2008;65:249–267. doi: 10.1002/cm.20258. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bessen M, Fay RB, Witman GB. Calcium control of flagellar waveform. J. Cell Biol. 1980;86:446–455. doi: 10.1083/jcb.86.2.446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elizabeth FS. Regulation of flagellar dynein by calcium and a role for an axonemal calmodulin and calmodulin dependent kinase. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2002;13:3303–3313. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E02-04-0185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.King SM, Patel-King RS. Identification of a Ca2+-binding light chain within Chlamydomonas outer arm dynein. J. Cell Sci. 1995;108:3757–3764. doi: 10.1242/jcs.108.12.3757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mizuno K, et al. A novel neuronal calcium sensor family protein, calaxin, is a potential Ca2+-dependent regulator for the outer arm dynein of metazoan cilia and flagella. Biol. Cell. 2009;101:91–103. doi: 10.1042/BC20080032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mizuno K, et al. Calaxin drives sperm chemotaxis by Ca2+-mediated direct modulation of a dynein motor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2012;109:20497–20502. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1217018109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ames JB, Levay K, Wingard JN, Lusin JD, Slepak VZ. Structural basis for calcium-induced inhibition of rhodopsin kinase by recoverin. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:37237–37245. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M606913200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ames JB, et al. Molecular mechanics of calcium-myristoyl switches. Nature. 1997;389:198–202. doi: 10.1038/38310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lim S, Strahl T, Thorner J, Ames JB. Structure of a Ca2+-myristoyl switch protein that controls activation of a phosphatidylinositol 4-kinase in fission yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:12565–12577. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.208868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tanaka T, Ames JB, Harvey TS, Stryer L, Ikura M. Sequestration of the membrane-targeting myristoyl group of recoverin in the calcium-free state. Nature. 1995;376:444–447. doi: 10.1038/376444a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nara M, Morii H, Tanokura M. Coordination to divalent cations by calcium-binding proteins studied by FTIR spectroscopy. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1828:2319–2327. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2012.11.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Vijay-Kumar S, Cook WJ. Structure of a sarcoplasmic calcium-binding protein from Nereis diversicolor refined at 2.0 Å resolution. J. Mol. Biol. 1992;224:413–426. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(92)91004-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Falke JJ, Drake SK, Hazard AL, Peersen OB. Molecular tuning of ion binding to calcium singal proteins. Q. Rev. Biophys. 1994;27:219–290. doi: 10.1017/S0033583500003012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miyakawa T, et al. Different Ca2+-sensitivities between the EF-hands of T- and L-plastins. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2012;429:137–41. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.10.126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Suzuki N, et al. Calcium-dependent structural changes in human reticulocalbin-1. J. Biochem. 2014;155:281–93.35. doi: 10.1093/jb/mvu003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pioletti M, Findeisen F, Hura GL, Minor D. L. jr. Three-dimensional structure of the KChIP1-Kv4.3 T1 complex reveals a cross-shaped octamer. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2006;13:987–995. doi: 10.1038/nsmb1164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Akaboshi M, et al. The crystal structure of plant-specific calcium-binding protein AtCBL2 in complex with the regulatory domain of AtCIPK14. J. Mol. Biol. 2008;377:246–257. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2008.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kon T, et al. The 2.8 Å crystal structure of the dynein motor domain. Nature. 2012;484:345–50. doi: 10.1038/nature10955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seamon KB. Calcium- and magnesium-dependent conformational states of calmodulin as determined by nuclear magnetic resonance. Biochemistry. 1980;19:207–215. doi: 10.1021/bi00542a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Andersson M, et al. Structural basis for the negative allostery between Ca2+- and Mg2+-binding in the intracellular Ca2+-receptor calbindin D9k. Protein Sci. 1997;6:1139–1147. doi: 10.1002/pro.5560060602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sánchez-Barrena MJ, et al. The structure of the C-terminal domain of the protein kinase AtSOS2 bound to the calcium sensor AtSOS3. Mol. Cell. 2007;26:427–35. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kabsch WXDS. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:125–132. doi: 10.1107/S0907444909047337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vonrhein C, Blanc E, Roversi P, Bricogne G. Automated structure solution with autoSHARP. Methods Mol. Biol. 2007;364:215–230. doi: 10.1385/1-59745-266-1:215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Cohen SX, et al. ARP/wARP and molecular replacement: The next generation. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2008;64:49–60. doi: 10.1107/S0907444907047580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collaborative Computational Project, Number 4 The CCP4 suite: Programs for protein crystallography. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 50, 760–763 (1994). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 45.Emsley P, Lohkamp B, Scott WG, Cowtan K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2010;66:486–501. doi: 10.1107/S0907444910007493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Murshudov GN, et al. REFMAC5 for the refinement of macromolecular crystal structures. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2011;67:355–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444911001314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vagin A, Teplyakov A. MOLREP: An automated program for molecular replacement. J. Appl. Cryst. 1997;30:1022–1025. doi: 10.1107/S0021889897006766. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Laskowski RE, Mac Arthur MW, Moss DS, Thornton JM. PROCHECK: A program to check the stereochemical quality of protein structures. J. Appl. Cryst. 1993;26:283–291. doi: 10.1107/S0021889892009944. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Evans PR, Murshudov GN. How good are my data and what is the resolution? Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2013;69:1204–1214. doi: 10.1107/S0907444913000061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Afonine PV, et al. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2012;68:352–367. doi: 10.1107/S0907444912001308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Miyakawa T, et al. Structural basis for the Ca2+-enhanced thermostability and activity of PET-degrading cutinase-like enzyme from Saccharomonospora viridis AHK190. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2015;99:4297–307. doi: 10.1007/s00253-014-6272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Guinier, A. & Fournet, G. In Small Angle Scattering of X-rays (John Wiley & Sons, 1955).

- 53.Tashiro M, et al. Characterization of fibrillation process of α-synuclein at the initial stage. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2008;369:910–914. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2008.02.127. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Svergun D, Barberato C, Koch MHJ. CRYSOL – a program to evaluate X-ray solution scattering of biological macromolecules from atomic coordinates. J. Appl. Crystal. 1995;28:768–773. doi: 10.1107/S0021889895007047. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The atomic coordinates have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank, www.pdb.org (PDB ID code 5X9A and 5YPX).