Abstract

Much of the immense present day biological diversity of Neotropical rainforests originated from the Miocene onwards, a period of geological and ecological upheaval in South America. We assess the impact of the Andean orogeny, drainage of Lake Pebas and closure of the Panama isthmus on two clades of tropical trees (Cremastosperma, ca 31 spp.; and Mosannona, ca 14 spp.; both Annonaceae). Phylogenetic inference revealed similar patterns of geographically restricted clades and molecular dating showed diversifications in the different areas occurred in parallel, with timing consistent with Andean vicariance and Central American geodispersal. Ecological niche modelling approaches show phylogenetically conserved niche differentiation, particularly within Cremastosperma. Niche similarity and recent common ancestry of Amazon and Guianan Mosannona species contrast with dissimilar niches and more distant ancestry of Amazon, Venezuelan and Guianan species of Cremastosperma, suggesting that this element of the similar patterns of disjunct distributions in the two genera is instead a biogeographic parallelism, with differing origins. The results provide further independent evidence for the importance of the Andean orogeny, the drainage of Lake Pebas, and the formation of links between South and Central America in the evolutionary history of Neotropical lowland rainforest trees.

Keywords: Andean orogeny, Pebas system, molecular dating, Neotropics, niche modelling, Panama isthmus

1. Introduction

The immense biological diversity of the Neotropics is the net result of diversification histories of numerous individual lineages [1–3]. Plants and animals encompassing a wide spectrum of forms, life histories and ecological tolerances have diversified in ecosystems ranging from high alpine-like conditions of the Andean Páramo, to seasonally dry tropical forests and the humid forests of lowland Amazonia [2,4–6]. The dynamic geological and ecological contexts of Neotropical species radiations shift in space and through time [2,7]. Understanding the importance of different factors in driving the origins of biological diversity therefore requires approaches that directly compare biologically equivalent species radiations within the same geographical areas and evolutionary time scales with the ecological conditions that prevailed in those times and places [8–10].

Even across seemingly similar ecosystems and organisms, there are differences in the levels of biodiversity within the Neotropics. For example, comparing across Neotropical rainforests, tree alpha-diversity peaks in the wetter, less seasonal part of Western Amazonia [6,11]. Correlation of this diversity with particular current conditions, such as climate and soils, may suggest a causal link in sustaining, and perhaps even driving, diversity [12,13]. However, both species diversity and ecological conditions have changed dramatically in the Neotropics since the Oligocene [2,11]. Hoorn et al. [11] reviewed evidence including that from the microfossil record, suggesting a ca 10% to 15% increase of plant diversity between ca 7 and 5 Ma. This was shortly after the Late Miocene draining of a wetland system in Western Amazonia, known as the Pebas system, or Lake Pebas, which existed from ca 17 to 11 Ma [11]. The Late Miocene draining of Western Amazonia was a direct result of the uplift that caused orogeny in the Andes [14], with continuous discharge of weathered material from the rising Andes leading to the gradual eastward expansion of terra firme forests. Hoorn et al. [11] concluded that the establishment of terrestrial conditions in Western Amazonia was a possible prerequisite for the (rapid) diversification of the regional biota.

The Andean orogeny itself has been linked to diversification, also in lowland (rather than just montane or alpine) biota [5,8,15,16]. The timeframe of the influence of the Andean orogeny on Neotropical vegetation may extend back to the Miocene, i.e. from ca 23.3 Ma onwards [17]. However, much of the uplift occurred in the late Miocene and Pliocene [18] with intense bursts of mountain building during the late middle Miocene (ca 12 Ma) and early Pliocene (ca 4.5 Ma). A further geological influence, the closing of the isthmus at Panama, facilitating biotic interchange between North and South America, also occurred during the Pliocene [11] and may also have driven diversification. The Panama isthmus has long been assumed to have fully closed by 3.5 Ma. This date has been challenged recently by fossil data and molecular phylogenetic analyses that may indicate migration across that Panama isthmus dating back to the Early Miocene, ca 6–7 Ma [19–22], e.g. resulting from dispersal by birds [19]. Finally, distribution shifts along the Andean elevational range during climatic changes in the Pleistocene (ca 1.8 Ma onwards) may also have driven diversification [23].

These events describe an explicit temporal framework for various plausible causes of diversification in Neotropical taxa. The means to test these hypotheses is presented by clades distributed across the transition zones between the Andes and western (lowland) Amazonia and between Central and South America. Just such distribution patterns are observed in a number of ‘Andean-centred’ (sensu Gentry [15]) genera of Annonaceae, Cremastosperma, Klarobelia, Malmea and Mosannona. These were the subject of analyses using phylogenetic inference and molecular dating techniques by Pirie et al. [24], who concluded that their diversifications occurred during the timeframe of the Andean orogeny. Pirie et al. [24] also identified clades within Mosannona endemic to the west and east of the Andes and estimated the age of their divergence to be ca 15–6 Ma. Central American representatives of the predominantly Asian Annonaceae tribe Miliuseae [25,26] are not found east of the Andes, which might also suggest that the Andes formed a barrier to dispersal prior to the closure of the Panama isthmus.

Even if diversifications occurred within the same timeframe, they were not necessarily driven by the same underlying factors. Further phylogenetic inference approaches would allow us to test whether Andean-centred distributions that originated in Cremastosperma, Mosannona and other Annonaceae clades were indeed influenced by common biogeographic processes (such as vicariance caused by Andean uplift), and whether allopatric speciation has been an important underlying process. For example, by combining phylogeny and species distribution modelling (SDM) in an African clade of Annonaceae, Couvreur et al. [27] could show that niche differences among closely related (but mostly not co-occurring) species were more similar than expected by chance. This was interpreted as suggesting allopatric speciation driven by landscape changes [27]. Such analyses might also contribute to testing diversification scenarios in Andean-centred Neotropical Annonaceae. However, the results presented in Pirie et al. [24] were based on limited taxon sampling within the genera, and species level relationships were largely unresolved, with the geographical structure apparent within Mosannona not reflected by supported clades in the other genera, limiting the power of phylogenetic approaches in general.

In this paper, we focus on two clades of trees found in Neotropical humid forest. Species of Cremastosperma (ca 31 spp. [28]) and Mosannona (ca 14 spp [29]) (figure 1; both Annonaceae) occur from lowland (i.e. up to 500 m) to pre-montane (500–1500 m) and into lower elevation montane rainforest, predominantly in areas surrounding the Andes in South America but also extending north into Central America [30]. Dispersal of the seeds, enclosed individually within fleshy monocarps on the end of often contrastingly coloured stipes (figure 1), is probably by birds. Yet, no species occur on both sides of the Andean mountain chain, suggesting that the Andes represents a current barrier to dispersal. In general, few species of Cremastosperma, and none of Mosannona, co-occur, which may suggest diversification driven by allopatric speciation. Those species of Cremastosperma with overlapping distributions are mostly limited to northern Peru and Ecuador. Our aims are to reassess the timing and sequence of shifts in ancestral distributions in the two related but independent clades of Cremastosperma and Mosannona to test the influence of the following factors on species diversification in the Neotropics: (i) the northern Andean orogeny, dividing western and eastern lineages; (ii) the drainage of lake Pebas creating new habitat in western Amazonia; and (iii) the closure of the Panama isthmus allowing geodispersal of lineages into Central America. To this end, we use phylogenetic inference, molecular dating and niche modelling techniques with new datasets for Cremastosperma and Mosannona based on expanded sampling of taxa and DNA sequence markers.

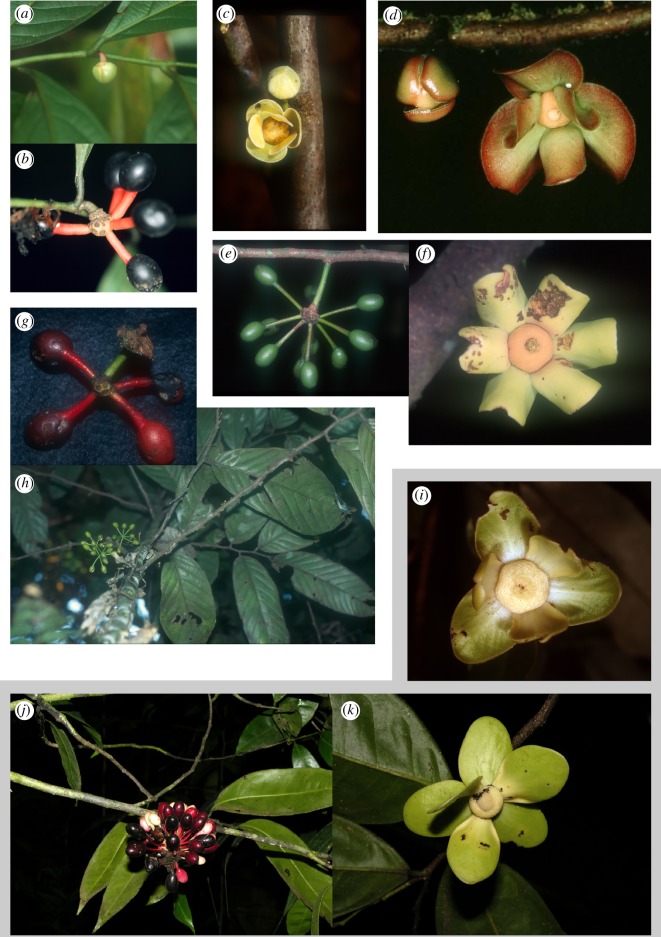

Figure 1.

Examples of species of Cremastosperma and Mosannona. (a,b) C. yamayakatense (Peru; photos: M.D.P.) flowering and fruiting specimens ca 1.5 m tall, showing the typical colour contrast in the ripe fruits; (c) C. cauliflorum (Peru: L.W.C.); (d) C. brevipes (French Guiana: P.J.M.M.); (e,f) C. leiophyllum (Bolivia: L.W.C.); (g,h) C. megalophyllum (Peru: P.J.M.M.); (i): M. vasquezii (Peru: L.W.C.); (j–k) M. costaricensis (Costa Rica: Reinaldo Aguilar).

2. Material and methods

2.1. Taxon sampling

This study largely used previously unpublished sequence data (partly used in Pirie et al. [28]) and published sequences [24,31–34] (see the electronic supplementary material, appendix 1). Datasets were constructed for Cremastosperma and Mosannona in two separate studies employing different outgroup sampling. For the Cremastosperma dataset, 10 Malmeoideae outgroup taxa were selected: seven of tribe Malmeeae, including two accessions each of the most closely related genera Pseudoxandra and Malmea; two of Miliuseae; and a single representative of Piptostigmateae (Annickia pilosa) as the most distant outgroup. For the Mosannona dataset, seven outgroup taxa were selected, exclusively from tribe Malmeeae: one accession each of Cremastosperma, Ephedranthus, Klarobelia, Malmea and Pseudomalmea; and two of Oxandra.

Within Cremastosperma, 39 accessions included 24 of the 29 described plus two informally recognized species in Pirie et al. [28], from across the entire geographical distribution, with some species represented by multiple accessions. For the Mosannona dataset, 14 accessions included 11 of the 14 species recognized by Chatrou [29]. This compares to 13 samples/species of Cremastosperma and seven of Mosannona represented in the analyses of Pirie et al. [24].

2.2. Character sampling

Character sampling differed somewhat between Cremastosperma and Mosannona matrices, depending on taxon-specific success with particular markers. DNA extraction, PCR and sequencing protocols for Cremastosperma followed [24,33], with modifications for Mosannona (as follows). For all 49 accessions of the Cremastosperma dataset, the plastid encoded (cpDNA) markers rbcL, matK, trnT-F (at least partial) and psbA-trnH were sampled. Amplification and sequencing of a further cpDNA marker, ndhF, was successful only in 34 accessions and that of pseudtrnL-F (an ancient paralogue of the plastid trnL-F region [34]), was successful only in 22 including just two outgroups (both species of Malmea).

For all 21 accessions of the Mosannona dataset, cpDNA rbcL, matK, trnL-F, psbA-trnH and the nuclear marker phytochrome C were sampled; for eight ingroup taxa and three outgroups additional cpDNA markers atpB-rbcL and ndhF and the nuclear marker malate synthase were also sampled. New primers were designed for phytochrome C, based on the sequences of representatives of Magnoliales from GenBank (Magnoliaceae: Magnolia×soulangeana, Degeneriaceae: Degeneria vitiensis, Eupomatiaceae: Eupomatia laurina, Annonaceae: Annona sp.). Two forward and two reverse primers were designed: PHYC-1F: 5′-GGATTGCATTATCCGGC-3′, PHYC-1R: 5′-CCAAGCAACCAGAACTGATT-3′, PHYC-2F: 5′-CTCAGTACATGGCCAAYATGG-3′ and PHYC-2R: 5′-GGATAGCCAGCTTCCA-3′, applied in the combination 1F/2R (preferentially), 1F/1R or 2F/2R (where 1F/2R was not successful) and subsequently sequenced with 1F and 2R. Malate synthase was amplified in two overlapping pieces using the primers ms400F and ms943R [35], and mal-syn-R1 (5'-CATCTTGAGAAGATGATCGG-3′) and mal-syn-F2 (5'-CCGATCATCTTCTCAAGATGATGTGG-3′), in the combinations ms400F/mal-syn-R1 and mal-syn-F2/ms943R. The thermocycler protocol for phytochrome C followed that for matK [33]; that for malate synthase was 94°C, 4 min; 35 cycles of (94°C, 1 min; 59°C, 1 min; 72°C, 2 min); 72°C, 7 min.

2.3. Sequence alignment and model testing

DNA sequences were edited in SeqMan 4.0 (DNAStar, Inc., Madison, WI) and aligned manually. Gaps in the alignments were coded as present/absent characters where they could be coded unambiguously, following the simple gap coding principles of Simmons and Ochoterena [36]. Matrices are presented in the electronic supplementary material, appendix 2, on Dryad [37], and on TreeBase (http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S20848). We performed preliminary phylogenetic analyses of markers separately using PAUP* v. 4.0 beta 10 [38] (as below), to identify any differences between datasets, then individual markers were imported into SequenceMatrix [39] which was used to export concatenated matrices for further analyses. Best fitting data partitioning strategies (given models implemented in RAxML, MrBayes and BEAST as below) were selected with PartitionFinder [40], given a concatenated matrix including all sequence markers and the 34 taxa for which ndhF was available, using a heuristic search strategy (greedy) and comparison of fit by means of the Bayesian information criterion. Individual markers (each representing either coding or non-coding regions) were specified as potential data partitions.

2.4. Phylogenetic analyses

Phylogeny was inferred under parsimony, using PAUP*; maximum likelihood (ML), using RAxML [41]; and Bayesian inference, using MrBayes v. 3.2 [42]. Under parsimony, heuristic searches of 1000 iterations, tree bisection and reconnection branch swapping, saving 50 trees per iteration were performed and bootstrap support (BS) was estimated for the markers individually and combined. Only partitioned RAxML analyses of the nucleotide data were performed including bootstrapping on CIPRES [43,44]. Bootstrapping was halted automatically following the majority-rule ‘autoMRE’ criterion. Two independent MrBayes runs of 10 million generations each were performed on the combined nucleotide and binary indel characters, implementing partitioned substitution models for the former, sampling every 1000 generations. Convergence was assessed (using the potential scale reduction factor) and post-burnin tree samples were summarized (using the sumt command) in MrBayes.

Given the phylogenetic results, we chose not to perform formal ancestral area analyses. The reasoning was first that a realistic model for the biogeographic scenario would involve changing extents of areas through time, the definition of which would be likely to strongly influence the results. Second, the geographical structure in the phylogenetic trees (see Results) suggested a minimal number of range shifts, limiting the power of any parametric model [45]. We therefore adopt a parsimonious interpretation of the ancestral areas of the geographically restricted clades and use this to infer the timeframes for shifts in geographical range.

2.5. Molecular dating

In order to infer the timing of lineage divergences within Cremastosperma and Mosannona, we used BEAST v. 1.8.2 [46] with a matrix of plastid markers (rbcL, matK, trnL-trnF, psbA-trnH and ndhF) of Malmeeae taxa combined from the individual matrices described above. Instead of using fossil evidence directly that could only be employed across the family as a whole, we used two different secondary calibration points based on the Annonaceae-wide results of Pirie and Doyle [47]. Although the results based on secondary calibration should be interpreted with caution [48,49], we could thereby analyse a matrix including only Malmeeae sequences, avoiding the uncertainty and error associated with analysing relatively sparsely sampled outgroups with contrasting evolutionary rates. The original analyses were calibrated using the fossils Endressinia [50] to constrain the most recent common ancestor (MRCA) of Magnoliaceae and Annonaceae to a minimum of 115 Ma, and Futabanthus [51], to constrain the MRCA Annonaceae to a minimum of 89 Ma. The latter fossil flower is incomplete and its membership of crown Annonaceae, although assumed in various studies, has not been tested with phylogenetic analysis [52], but both of the two constraints individually imply similar ages for the clade [47]. We used node age ranges derived using BEAST, assuming lognormal distribution of rates, and penalized likelihood (PL), assuming rate autocorrelation. Both of these assumptions are questionable in Annonaceae, and the methods result in somewhat differing ages. Under PL, Pirie and Doyle [47] estimated the age of the Malmeeae crown node to be 52 Ma ± 3, which we represented with (a) a uniform prior and (b) a normal prior (mean of 52 and s.d. of 3) on the age of the root node. Under BEAST, they estimated 95% posterior probability (PP) range of the age to be 33–22 Mya, which we represented with (a) a uniform prior and (b) a normal prior (mean 27, s.d. of 3). With these prior distributions, we aimed to represent uncertainty only in the dating method (given the calibration), not the further uncertainty associated with fossil calibrations (i.e. that they represent minimum age constraints). We employed a birth–death speciation model, assumed a lognormal rate distribution and rooted the tree by enforcing the monophyly of the two sister clades that together represent all the species, as identified in the previous analyses. We performed two independent runs of 10 million generations, assessed their convergence using TRACER v. 1.6 [53] and summarized the results using programs of the BEAST package.

2.6. Species distribution modelling

Data on occurrences of species included in the Cremastosperma and Mosannona phylogenies were extracted from the herbarium specimen database (BRAHMS [54]) of Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden, the Netherlands (http://herbarium.naturalis.nl/). These comprised records curated during our revisionary work on these genera based on specimens housed in multiple international herbaria. A total of 633 specimens of Cremastosperma and 442 specimens of Mosannona were available that were both identified to species by the authors and adequately georeferenced. These specimens included duplicates, i.e. multiple specimens of the same species collected either at the same locality, or not distantly enough from it to be treated as separate localities in our analyses. We only modelled species distributions for species recorded at least at four unique localities. After the removal of duplicates, the database consisted of 222 unique occurrence data points for 10 taxa of Mosannona and 319 data points for 20 taxa of Cremastosperma. The number of unique occurrence localities per species ranged from 4 (Cremastosperma macrocarpum) to 145 (Mosannona depressa subsp. depressa) (electronic supplementary material, appendix 3). Current environmental variables were downloaded from www.worldclim.org at 2.5 minute resolution and categorical Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations soil layers were downloaded from www.fao.org. In a preliminary analysis, we used Pearson correlation tests to remove correlated climate (containing continuous data) and soil (containing numeric categorical data) variables, resulting in eight independent climate layers and 10 independent soil variable layers (electronic supplementary material, appendix 4). We assessed all SDMs using Maxent v. 3.3.3 k [55]. Maxent has been demonstrated to perform well when data are restricted to (i) solely presence only occurrences [56] and (ii) small numbers of point localities [57] (although the number of point localities needed is nevertheless higher for widespread species [58]). Given a set of point localities and environmental variables over geographical space, Maxent estimates the predicted distribution for each species. It does so by finding the distribution of maximum entropy (the distribution closest to uniform) under the constraint that the expected value of each environmental variable for the estimated distribution matches its empirical average over a sample of locations [55]. The resulting distribution model is a relative probability distribution over all grid cells in the geographical area of interest. It expresses the relative probability of the occurrence of a species in a grid cell as a function of the values of the environmental variables in that grid cell. Maxent runs were performed for each of the 29 taxa with the following options: auto features, random test percentage = 0, maximum iterations = 500.

A commonly used measure for model performance is the ‘area under the curve’ (AUC [59]) that is calculated by Maxent. However, its use has been criticized for reasons including erroneously indicating good model performance in the case of SDMs based on few records [60,61]. SDMs were tested for significance using a phylogenetically controlled null-model approach [60]. For each species, 100 replicate SDMs were generated using random locality points in the same numbers as the original locality points. The demarcation of the assemblage of locality points from which random samples are drawn is crucial, as a too large assemblage (e.g. the entire Neotropics) will almost certainly result in null-model tests that indicate that SDMs are significantly different from random. We drew the random locality points from 1009 unique locality points where species of the tribe Malmeeae have been collected, which were extracted from the BRAHMS database of Naturalis Biodiversity Center, Leiden. Cremastosperma and Mosannona belong to this tribe that comprises ca 180 species [62]. All of these species occur in wet tropical forests, and the majority have distributions that overlap with those of species of Cremastosperma and Mosannona. The replicate AUC values were sorted into ascending order and the value of the 95th element is considered as the estimate of the 95th percentile of the null-model distribution. If the AUC value of the original SDM is greater than the 95th percentile, it is considered significantly different from random.

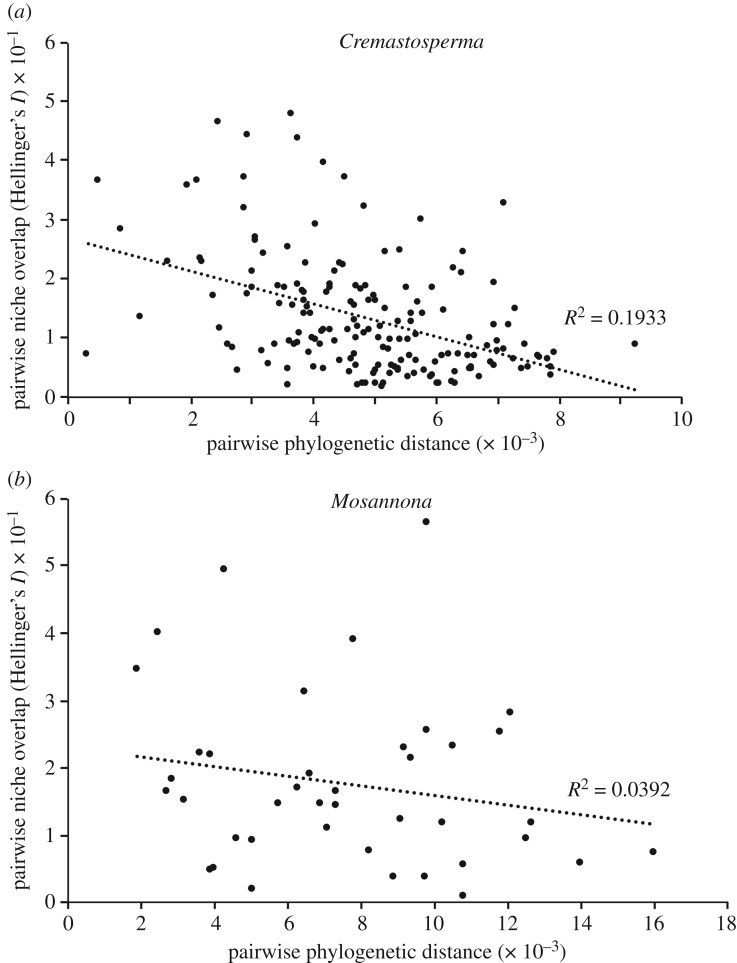

Maxent output was used to calculate the pairwise Hellinger's I niche overlap metric between all species within Cremastosperma and Mosannona using ENMtools [63]. Hellinger's I values were then used to calculate the average niche overlap within and between the different geographically restricted Cremastosperma and Mosannona clades. To test whether abiotic niches are phylogenetically conserved within both genera, we correlated pairwise Hellinger's I values with pairwise patristic distances. These were calculated using PAUP*, using one of the most parsimonious trees, adding up connecting branches between species pairs under the likelihood criterion (GTR + gamma model, all parameters estimated). This approach allowed a meaningful interpretation of niche overlap, despite phylogenetic uncertainty within the geographically restricted clades that, in most cases, prevented the identification of sister-species pairs.

3. Results

3.1. Phylogenetic analyses

Variable and informative characters per DNA sequence marker are reported in table 1. Per PCR amplicon, the plastid markers provided just 6–9/1–8 informative characters within Cremastosperma/Mosannona. Despite the short sequence length, pseud-trnL-F provided 13 within Cremastosperma.

Table 1.

Included, variable and parsimony informative characters per DNA sequence marker, in descending order following the total number of informative characters in Cremastosperma. (Values are made comparable by the inclusion of only Cremastosperma/Mosannona taxa for which all sequences were available. To compare variable/informative characters per sequence, note that rbcL, ndhF and malate synthase were PCR amplified in at least two fragments.)

| marker | included characters | parsimony uninformative characters | parsimony informative characters | parsimony informative indels |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| rbcLa | 1401/1387 | 37/9 | 16/13 | 0/0 |

| ndhF | 2038/2034 | 58/22 | 12/2 | 0/0 |

| pseud-trnLF | 535/– | 9/– | 12/– | 1/– |

| malate synthase | –/928 | –/21 | –/12 | –/0 |

| trnL-trnF | 961/909 | 27/19 | 8/8 | 1/0 |

| trnT-trnL | 898/– | 30/– | 7/– | 1/– |

| psbA-trnH | 483/449 | 13/4 | 6/5 | 2/0 |

| matK | 831/831 | 17/12 | 7/3 | 0/0 |

| atpB-rbcL | –/784 | –/7 | –/2 | –/1 |

| phytochrome C | –/634 | –/9 | –/2 | –/0 |

aIncluding 3′ non-coding region.

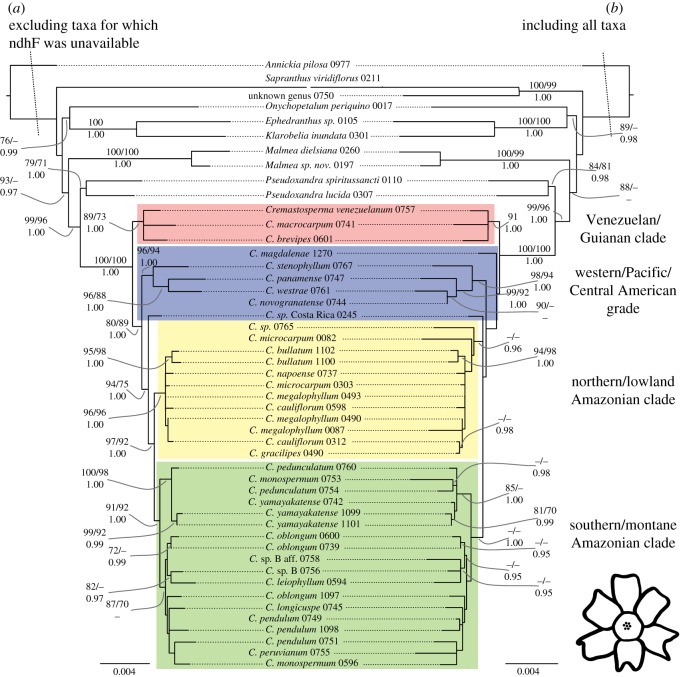

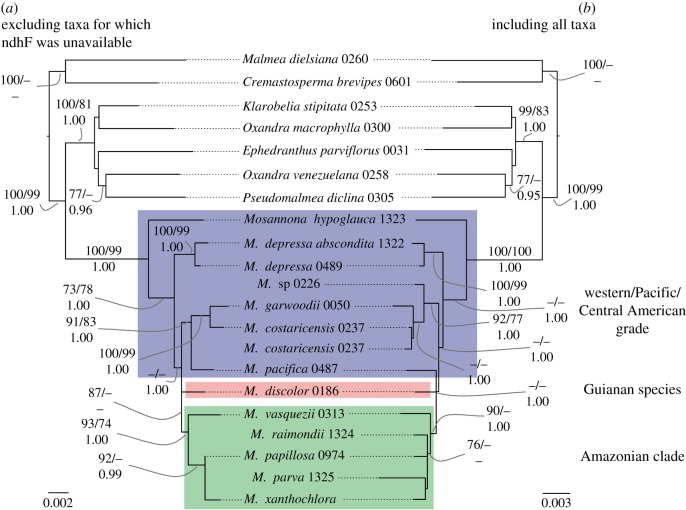

Parsimony bootstrap analysis of the individual data partitions revealed no supported incongruence (BS greater than 70%). Data were thus combined in further analyses. Figures 2 and 3 each show two best scoring trees as inferred under ML from the combined Cremastosperma and Mosannona data, respectively. Figures 2a and 3a show results including only taxa for which ndhF was available; and figures 2b and 3b show results including all taxa (i.e. with a considerable proportion of missing data). BS under parsimony and ML, and PP clade support under Bayesian inference are also indicated. In both cases, the results of parsimony analyses were consistent with those obtained under ML and Bayesian inference, but analyses of the matrices with more missing data resulted in a greater number of nodes subject to PP ≥ 0.95 than those subject to BS ≥ 70.

Figure 2.

Phylogenetic hypotheses for Cremastosperma based on rbcL, matK, trnT-F, psbA-trnH, ndhF and pseudtrnL-F. (a) Excluding taxa for which ndhF was unavailable; (b) including all taxa. Topologies and branch lengths are of the best scoring ML trees with scale in substitutions per site. Branch lengths subtending the ingroup are not to scale. Clade support is indicated: ML and parsimony bootstrap percentages (above; left and right, respectively) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (below); as are major clades referred to in the text.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic hypotheses for Mosannona based on rbcL, matK, trnL-F, psbA-trnH, ndhF, atpB-rbcL, PHYC and malate synthase. (a) Excluding taxa for which ndhF was unavailable; (b) including all taxa. Topologies and branch lengths are of the best scoring ML trees with scale in substitutions per site. Branch lengths subtending the ingroup are not to scale. Clade support is indicated: ML and parsimony bootstrap percentages (above; left and right, respectively) and Bayesian posterior probabilities (below); as are major clades referred to in the text.

The combined analyses revealed a number of clades within both Cremastosperma and Mosannona corresponding to discrete geographical areas. In Cremastosperma, the divergence of the Venezuelan and Guianan lineages, together in a well-supported clade, occurred prior to that leading to clades found in the tropical Andes or in the Chocó/Darién/western Ecuador region or Central America (i.e. either the west or the east side of the Andes mountain chain). Western species fall within a grade of three lineages (a clade including Cremastosperma panamense, C. novogranatense, C. stenophyllum and C. westrae; and two isolated lineages corresponding to C. sp. A from Costa Rica and C. magdalenae from the Magdalena valley of Colombia), in which the three Central American species are not each other's closest relatives. A single clade including all Amazonian species is nested within this grade; it comprises two clades: one including more lowland and northerly distributed species; the other more southerly and higher elevation species. In Mosannona, the species are similarly represented by a western grade and a single eastern, Amazonian, clade. The single Guianan species (none are known from Venezuela), rather than being sister to these, is nested within, part of a polytomy of the western and eastern lineages.

3.2. Molecular dating

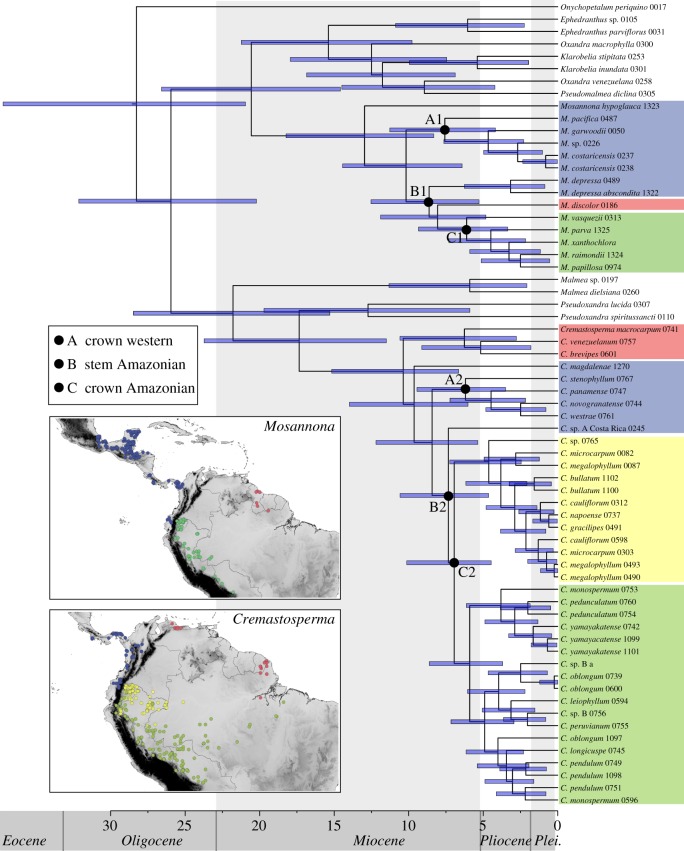

Relaxed-clock molecular dating using BEAST resulted in ultrametric trees with topologies consistent with those obtained separately for Cremastosperma and Mosannona under parsimony, ML, and Bayesian inference (figure 4). The posterior age distributions for the root node given the normal prior were somewhat wider than the priors (37-21 Ma instead of 33-22 for the BEAST calibration; 69-47 instead of 52 +/– 3 for the PL calibration), reflected in somewhat wider/older age estimates for shallower nodes. The nodes that define the divergence of lineages to the west and east of the Andes are (A) the crown nodes of the clades including exclusively western species (such as M. pacifica, M. garwoodii, M. costaricensis and M. sp.: figure 4 A1; and C. stenophyllum, C. panamense, C. novogranatense and C. westrae: figure 4, A2); (B) the stem nodes of the exclusively Amazonian clades (figure 4, B1 and B2), representing the age of the most recent common ancestors of the western and eastern lineages; and (C) the crown nodes of Amazonian clades (figure 4, C1 and C2). The minimum and maximum ages of dispersal into Central American are defined by the crown and stem nodes, respectively, of Central American lineages. In the case of Cremastosperma, these are single species/accessions and hence without crown nodes in these phylogenetic trees. In the case of Mosannona, two clades of taxa are endemic to Central America (M. depressa sspp., and M. costaricensis/M. garwoodii) for which both stem and crown node ages could be estimated. The age ranges for these nodes given the older and more recent secondary calibrations (root node 25-13 Ma; 12-3 Ma) are reported in table 2. The confidence intervals for each of A1 and A2, B1 and B2 and C1 and C2 for a given calibration largely overlap. The implied time window for a putative vicariance process caused by Andean uplift ranges between 24 Ma and 7 Ma (older calibration) and 13 Ma and 3 Ma (recent calibration). The minimum age for dispersal into Central America ranged from 15 to 1 Ma, and only given the older calibration did the minimum estimate for the M. costaricensis/M. garwoodii crown node exceed 3.5 Ma (5 Ma).

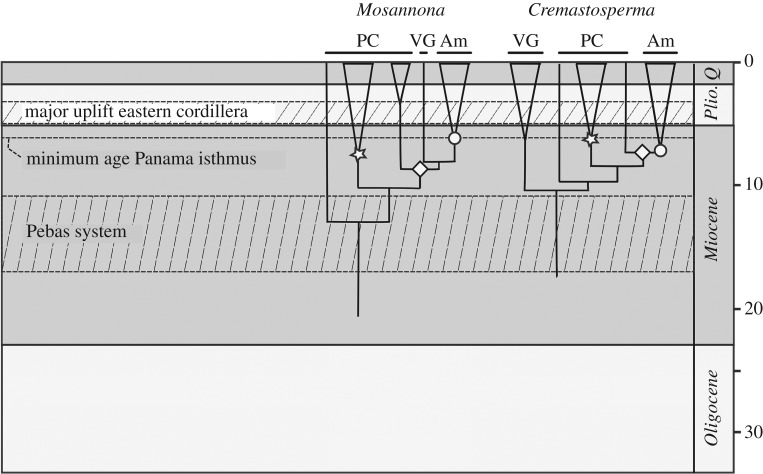

Figure 4.

Chronogram of Malmeeae. Chronogram (given the normal distributed age calibration), indicating nodes within Cremastosperma and Mosannona that define the divergence of lineages to the west and east of the Andes, as referred to in the text and in table 2: A1/A2: crown nodes of clades including exclusively Western species; B1/B2: stem nodes of exclusively Amazonian clades; C1/C2: crown nodes of Amazonian clades. Distributions of the clades, plus those of the Cremastosperma northern/lowland and southern/montane clades are illustrated on the inset maps.

Table 2.

Relaxed clock molecular dating estimates (limits of the 95% highest posterior density) for the ages of selected nodes given older and more recent secondary calibration points. (Ages before the forward slash result from analyses with normal distributions of the age prior, after the forward slash result from analyses with uniform distributions of the age prior.)

| node | age (older) | age (more recent) |

|---|---|---|

| A1 | 22-9/16-8 | 11-4/8-4 |

| A2 | 18-8/14-7 | 9-4/7-3 |

| B1 | 24-11/17-10 | 13-5/8-5 |

| B2 | 20-10/14-8 | 11-5/7-3 |

| C1 | 18-7/14-7 | 9-3/7-3 |

| C2 | 19-9/− | 10-4/− |

| M. depressa sspp. stem | 24-11/17-9 | 13-5/8-4 |

| M. depressa sspp. crown | 12-2/9-2 | 6-1/4-1 |

| M. costaricensis/M. garwoodii stem | 22-9/16-8 | 11-4/8-4 |

| M. costaricensis/M. garwoodii crown | 15-5/11-4 | 8-2/5-2 |

| C. sp. Costa Rica stem | 20-10/14-8 | 11-5/8-4 |

| C. panamense stem | 14-5/14-7 | 7-2/7-3 |

| C. westrae stem | 10-2/11-4 | 5-1/5-2 |

| Cremastosperma lowland Amazonian clade stem | 20-10/12-6 | 11-5/7-3 |

| Cremastosperma lowland Amazonian clade crown | 14-5/9-3 | 7-2/4-1 |

3.3. Species distribution modelling

Null-model tests showed that all SDMs were significantly different from random, except for that of Cremastosperma pendulum, which was excluded from subsequent analyses. Pairwise intra-generic Hellinger's I niche overlap measures ranged from 0.009 (M. depressa subsp. depressa versus M. xanthochlora) to 0.987 (C. pacificum versus C. novogranatense). Niche similarity was found to be negatively correlated with phylogenetic distance in Cremastosperma (squared Pearson correlation R2 = 0.1933, p < 0.0001), while it was not in Mosannona (squared Pearson correlation R2 = 0.0392, p = 0.2207). Even though the SDMs used in the regression analysis all differed significantly from random, we tested the effect of removing the species represented by the smallest number of localities (n = 4). This resulted in no noteworthy changes in values of R2 and p.

Niche similarity is considerably greater for Amazonian species than for species in any of the remaining areas (table 3). By contrast, the smallest niche overlap for species within a given area was observed for the areas west of the Andes, viz. Pacific South America and Central America. Niche similarity within each of the four areas exceeds niche similarity between them in all cases. Only the mean value for Hellinger's I within Pacific/Central America approaches those for between-area niche similarity. For Cremastosperma, the two areas with the largest niche differences are the Amazonian lowland and the Guianas/Venezuela. For Mosannona, niche overlap cannot be calculated for the Guianas and Venezuela owing to the occurrence of only single species, yet the within-area niche differences are larger in the Amazonian lowland than Pacific South America and Central America, as in Cremastosperma.

Table 3.

Within and between-area comparison of niche overlap (Hellinger's I).

|

Cremastosperma |

Mosannona |

||

|---|---|---|---|

| clade (number of species) | Hellinger's I within-clade | clade (number of species) | Hellinger's I within-clade |

| lowland Amazonian (5) | 0.64 ± 0.06 | Amazonian (4) | 0.27 ± 0.06 |

| montane Amazonian (9) | 0.32 ± 0.04 | Pacific/Central-American (5) | 0.20 ± 0.02 |

| Pacific/Central-American (2) | 0.16 | Guianan/Venezuelan (1) | |

| Guianan/Venezuelan (3) | 0.38 ± 0.02 | ||

| clades compared | Hellinger's I between-clades | clades compared | Hellinger's I between-clades |

|---|---|---|---|

| lowland Amazonian ×montane Amazonian | 0.32 ± 0.02 | Amazonian × Pacific/Central-American | 0.11 ± 0.02 |

| lowland Amazonian × Pacific/Central-American | 0.19 ± 0.03 | ||

| lowland Amazonian × Guianan/Venezuelian | 0.08 ± 0.002 | ||

| montane Amazonian × Pacific/Central-American | 0.14 ± 0.02 | ||

| montane Amazonian × Guianan/Venezuelian | 0.15 ± 0.01 | Cremastosperma/Mosannona clades compared | |

| Pacific/Central-American × Guianan/Venezuelian | 0.19 ± 0.03 | Crem. lowland Amazonian × Mos. Amazonian | 0.42 ± 0.04 |

| montane group C. pedunculatum × montane group C. oblongum | 0.31 ± 0.06 | Crem. montane Amazonian × Mos. Amazonian | 0.35 ± 0.04 |

4. Discussion

4.1. Consistent biogeographic signals revealed in phylogenies of two rainforest tree genera

The phylogenetic hypotheses for Cremastosperma and Mosannona show strong geographical signal, with clades endemic both to regions divided by obvious present day dispersal barriers (east and west of the Andes), and to regions that are currently largely contiguous (i.e. within Amazonia). These results appear to contrast with the assumptions of rapid dispersal abilities of Amazon biota [64,65], such as species-rich Neotropical lowland clades [66] including the more typically Amazon-centred, more widely distributed, Annonaceae genus Guatteria [67]. The strong correlation between phylogenetic patterns and geographical areas found here resembles more closely the patterns found in Neotropical birds [68].

Andean-centred distribution patterns are the exception in Neotropical Annonaceae clades, but have originated multiple times independently, for example in Malmea, Klarobelia and Cymbopetalum, as well as Cremastosperma and Mosannona [24]. This may reflect an ecological distinction between more montane Andean-centred genera and their widespread lowland sister-groups. It may also be associated with more limited dispersal abilities of the smaller understorey trees typical of Cremastosperma and Mosannona, as opposed to canopy trees [13] as represented e.g. by species of Guatteria. Similarities between different Andean-centred clades suggest the potential for identifying common and more general underlying causes.

4.2. The impact of the Andean orogeny on lowland rainforest taxa in the Neotropics

The diversifications of extant species of Cremastosperma and Mosannona date to the Middle-Late Miocene (figure 4). During this period, the uplift of the westernmost Cordillera Occidental, the oldest of three cordilleras in Colombia, and of the Cordillera Central had been completed (figure 6). The easternmost Cordillera Oriental was the last Colombian cordillera to rise, with uplift starting around 13-12 Ma. The Cordillera Oriental is decisive for the establishment of a dispersal barrier for lowland organisms on either side of the Andes. During the Miocene, it consisted of low hills, only attaining its current height during the Pliocene and early Pleistocene [18], and as a result the northwestern part of the current Amazon basin was contiguous with areas now in the Colombian states of Chocó and Antioquia, west of the Andes.

Figure 6.

Geological events and ages of clades in Cremastosperma and Mosannona. PC, Pacific Costal and Central American; VG, Venezuelan/Guianan; Am, Amazonian.

Rough bounds for the timing of establishment of an east-west dispersal barrier can be inferred from stem and crown node ages of exclusively eastern and western clades. In both Cremastosperma and Mosannona, the stem node ages, representing common ancestors that were either widespread or which were able to disperse between areas, date to 24-10 Ma (older estimates) or 13-5 Ma (more recent estimates). Crown node ages, representing common ancestors after which there is no further evidence for such dispersal, date to 22-7 Ma (older estimates) or 11-3 Ma (more recent estimates). The error margins are wide, but consistent with a vicariance scenario. Comparable evidence for the Andes forming a strong barrier to dispersal has been found in phylogeographic patterns of individual species [65,69], and phylogenies of clades of lowland tree and palm species [70–73]. However, there are examples of widespread individual species in clades also showing east-west disjunctions, such as Theobroma [74], and a notable contrast is presented by results in tropical orchids, for which there is evidence of more recent trans-Andean dispersal, suggesting that the barrier is less effective for plants with more easily dispersed diaspores [75,76].

4.3. The drainage of Lake Pebas, dispersal and diversification in western Amazonia

Prior to the Andes forming a dispersal barrier for lowland rainforest biota, dispersal from northwestern South America further into the Amazon may have been blocked by Lake Pebas, that flooded the entire western Amazon from ca 17 to 11 Ma [11,77]. One of the first areas to emerge in the upper Amazon basin was the Vaupes Swell or Vaupes Arch, which may have acted as a dispersal route from western Amazonia to the Guianas for frogs during the Late Miocene [78]. This route is also plausible in the case of Cremastosperma. The divergence of the Venezuelan/Guianan clade was prior to that of western and eastern clades, which suggests either an earlier widespread distribution, or stepping stone dispersal, across northern South America. The absence of Mosannona in rainforest of coastal Venezuela could be explained by extinction or failure to sample species (the taxa known to this region are rare [79]). However, the differences between the two genera both in relationships and in the niches of the Guianan species compared with other clades may instead point to different origins. While Cremastosperma Venezuelan/Guianan clades are both distantly related and occupy more dissimilar niches compared with Amazonian clades, the Guianan M. discolor is closely related to the Mosannona Amazonian clade and similar in niche. This may imply a more southerly dispersal route that could have occurred much more recently.

Despite the broad similarities between Cremastosperma and Mosannona, the clades also differ in species numbers, particularly reflected in fewer Amazonian taxa in Mosannona. In Cremastosperma, we identified a single Amazonian clade comprising two subclades of contrasting distributions: one of more lowland, northerly species, the other of more montane or southerly distributed species (figures 2 and 4). These patterns reflect clade-specific niche differences, whereby species of the lowland/northern clade occupy a particularly narrow niche compared with the montane/southerly clade.

Given its distribution and age (crown node between 14 and 2 Ma old), the lowland/northern clade may provide further evidence of diversification within the forested habitat that formed following drainage of Lake Pebas. A similar result was obtained within the palm genus Astrocaryum [71], while in Quiinoideae diversification was earlier, with subsequent independent colonizations of the region [80]. The distributions of the individual species of lowland/northern Cremastosperma broadly overlap, but they are morphologically distinct and particularly diverse in floral characteristics, with large differences in flower colour, indumenta and inflorescence structure. This might point to sympatric speciation in the group, perhaps driven by pollinators or herbivores, as demonstrated for some Neotropical clades of woody plants [81,82].

The montane/southern Cremastosperma clade by contrast is morphologically more homogenous, spread over a wider latitudinal range and with lesser overlap in the distributions of individual species (with the exception of the widespread C. monospermum, which alone represents much of the northern and eastern extremities of the clade; figure 4). Given the age of this clade and its proximity to the Andes, diversification may have been influenced by habitat shifts caused by uplift and/or Pleistocene climatic fluctuations. The large proportion of such pre-montane species across the Cremastosperma clade as a whole may explain the lack of niche-based evidence for allopatric speciation, with the significant negative correlation between phylogenetic distance and niche overlap (figure 5a) reflecting (phylogenetically conserved) niche differentiation. Both this scenario and that for the lowland/northern clade differ markedly from that of allopatric speciation with lack of niche shifts inferred in the diversification of lowland Monodora and Isolona (Annonaceae) in Africa [27].

Figure 5.

Correlation between Hellinger's I metric and patristic distance in Cremastosperma and Mosannona.

In Mosannona, the single Amazonian clade represents far fewer species and ecological distinctions between-clades are not so obvious. The overall niche overlap is lower than that of the Cremastosperma lowland Amazon clade, suggesting that Mosannona may have failed to adapt to the same habitat and, perhaps as a result, failed to diversify to the same extent. Neither niche conservatism, nor a negative correlation between phylogenetic distance and niche overlap as seen in Cremastosperma, is significant across the genus as a whole. This may, in part, reflect the lower numbers of species and/or records available for analysis. Moreover, the use of remotely sensed climate data could have improved the predictive power of our SDMs [83]. Nevertheless, despite the lack of evidence from ecological niches and given the entirely non-overlapping species distributions, allopatric speciation in this and the wider clade is still plausible.

4.4. Closure of the Panama isthmus and geodispersal into Central America

Numerous studies have assumed an age of 3.5 Ma from which dispersal between North-Central and South America would have been possible. However, evidence has been presented suggesting that plant dispersal across the Panama isthmus occurred earlier than that of animals [84] and that dispersal occurred prior to its complete closure [21]. Winston et al. [20] demonstrated that strictly terrestrial South American army ants colonized Central America in two waves of dispersal, the earliest of which occurred 7 Ma. However, pre-Pliocene dates for the formation of an isthmus are still disputed [85], and further data are warranted to further test the timing of dispersal events, potentially between separate land masses, in different groups.

Of the species of Cremastosperma and Mosanonna that are found in Central America, only a few extend beyond Panama or Costa Rica and some, such as C. panamense and M. hypoglauca, straddle the Panama/Colombian border with populations in both Central and South America. Central American lineages of Cremastosperma are single species nested within western clades, implying multiple independent northerly dispersals. The stem lineages date to 20-1 Ma, and these dispersal events must have taken place subsequently, but given the data available it is not possible to further narrow down the timeframe. Seed dispersal could have been facilitated, e.g. by toucans (as reported on a herbarium label of the Amazonian species, M. papillosa), which diversified within the region within roughly the same timeframe [86,87]. Mosannona include two clades of exclusively Central American species (M. garwoodii and M. costaricensis) or subspecies (M. depressa), also nested within a western grade, and the ages of these crown groups can be interpreted as minima for the preceding northerly dispersals. Although independent arrivals over earlier land connections [21] or even (long-distance) dispersal [2,64] cannot be ruled out, the ages of these nodes, ranging from 12-1 to 15-2 Ma would not exclude a scenario of concerted range expansions (i.e. geodispersal) following Pliocene closure of the isthmus.

The biogeographic scenario that emerges from our study reinforces the importance of the geological history of north-western South America during the Late Miocene—Early Pliocene for the evolution of plant diversity in the Neotropics. Three major geological processes (the uplift of the Andes, Lake Pebas and the Panama isthmus) interacted within a timeframe sufficiently narrow to challenge the discerning power of current molecular dating techniques. Ancestral lineages that were present in north-western South America were subject to vicariance and to opportunities for dispersal within a period of little more than about 4 Myr. These events nevertheless left common signatures in the phylogenies of clades such as Cremastosperma and Mosannona (figure 6) that in part—though not entirely—are reflected in the similarities in their modern distributions.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

The authors acknowledge Jan Wieringa for assistance with the BRAHMS database and Reinaldo Aguilar for the use of his photos of M. costaricensis. A preprint version of this paper was reviewed and recommended [88] by Peer Community In Evolutionary Biology (https://evolbiol.peercommunityin.org/public/rec?id=74), for which constructive criticism from Hervé Sauquet and Thomas Couvreur is gratefully acknowledged. For further comments, we also thank Hermine Alexandre, Julie Faure, Steven Ginzbarg, John Clark and Simon Joly, and an anonymous reviewer.

Data accessibility

DNA sequences used in this study have been deposited in GenBank, sequence matrices and phylogenetic trees are available from TreeBase (http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S20848) and matrices, trees, distribution data and environmental layers used for niche modelling are available from Dryad (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.49g85 [37]).

Authors' contributions

M.D.P., H.M-S. and R.A.W. carried out the molecular laboratory work; M.D.P., R.A.W. and L.W.C. performed analyses; M.D.P., P.J.M.M. and L.W.C. conceived the study; M.D.P. led the writing to which all authors contributed. All authors gave final approval for publication.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no financial or non-financial competing interests.

Funding

Funding for fieldwork was provided by The Netherlands Organisation for Scientific Research (NWO; R 85-351 to M.D.P.) and the Hugo de Vries Foundation (to L.W.C.).

References

- 1.Antonelli A, Sanmartín I. 2011. Why are there so many plant species in the Neotropics? Taxon 60, 403–414. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hughes CE, Pennington RT, Antonelli A. 2013. Neotropical plant evolution: assembling the big picture. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 171, 1–18. (doi:10.1111/boj.12006) [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pennington RT, Hughes M, Moonlight PW. 2015. The origins of tropical rainforest hyperdiversity. Trends Plant Sci. 20, 693–695. (doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2015.10.005) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pennington RT, Lavin M, Särkinen T, Lewis GP, Klitgaard BB, Hughes CE. 2010. Contrasting plant diversification histories within the Andean biodiversity hotspot. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 13 783–13 787. (doi:10.1073/pnas.1001317107) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Luebert F, Weigend M. 2014. Phylogenetic insights into Andean plant diversification. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2, 1–17. (doi:10.3389/fevo.2014.00027) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hoorn C, Wesselingh FP. 2009. Amazonia: landscape and species evolution. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham A. 2011. The age and diversification of terrestrial New World ecosystems through Cretaceous and Cenozoic time. Am. J. Bot. 98, 336–351. (doi:10.3732/ajb.1000353) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Fine PVA, Zapata F, Daly DC. 2014. Investigating processes of Neotropical rain forest tree diversification by examining the evolution and historical biogeography of the Protieae (Burseraceae). Evolution 68, 1988–2004. (doi:10.1111/evo.12414) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Koenen EJM, Clarkson JJ, Pennington TD, Chatrou LW. 2015. Recently evolved diversity and convergent radiations of rainforest mahoganies (Meliaceae) shed new light on the origins of rainforest hyperdiversity. New Phytol. 207, 327–339. (doi:10.1111/nph.13490) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Terra-Araujo MH, de Faria AD, Vicentini A, Nylinder S, Swenson U. 2015. Species tree phylogeny and biogeography of the Neotropical genus Pradosia (Sapotaceae, Chrysophylloideae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 87, 1–13. (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2015.03.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hoorn C, et al. 2010. Amazonia through time: Andean uplift, climate change, landscape evolution, and biodiversity. Science 330, 927–931. (doi:10.1126/science.1194585) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stropp J, ter Steege H, Malhi Y. 2009. Disentangling regional and local tree diversity in the Amazon. Ecography 32, 46–54. (doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2009.05811.x) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kristiansen T, Svenning JC, Eiserhardt WL, Pedersen D, Brix H, Munch Kristiansen S, Knadel M, Grández C, Balslev H. 2012. Environment versus dispersal in the assembly of western Amazonian palm communities. J. Biogeogr. 39, 1318–1332. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2012.02689.x) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shephard GE, Müller RD, Liu L, Gurnis M. 2010. Miocene drainage reversal of the Amazon River driven by plate–mantle interaction. Nat. Geosci. 3, 870–875. (doi:10.1038/ngeo1017) [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gentry AH. 1982. Neotropical floristic diversity: phytogeographical connections between Central and South America, Pleistocene climatic fluctuations, or an accident of the Andean orogeny? Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 69, 557–593. (doi:10.2307/2399084) [Google Scholar]

- 16.Särkinen TE, et al. 2007. Recent oceanic long-distance dispersal and divergence in the amphi-Atlantic rain forest genus Renealmia L.f. (Zingiberaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 44, 968–980. (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.06.007) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Burnham RJ, Graham A. 1999. The history of neotropical vegetation: new developments and status. Ann. Missouri Bot. Gard. 86, 546–589. (doi:10.2307/2666185) [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gregory-Wodzicki KM. 2000. Uplift history of the central and northern Andes: a review. Geol. Soc. Am. Bull. 112, 1091–1105. (doi:10.1130/0016-7606(2000)112<1091:UHOTCA>2.0.CO;2) [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bacon CD, Mora A, Wagner WL, Jaramillo CA. 2013. Testing geological models of evolution of the Isthmus of Panama in a phylogenetic framework. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 171, 287–300. (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2012.01281.x) [Google Scholar]

- 20.Winston ME, Kronauer DJC, Moreau CS. 2017. Early and dynamic colonization of Central America drives speciation in Neotropical army ants. Mol. Ecol. 26, 859–870. (doi:10.1111/mec.13846) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bacon CD, Silvestro D, Jaramillo C, Smith BT, Chakrabarty P, Antonelli A. 2015. Biological evidence supports an early and complex emergence of the Isthmus of Panama. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 112, 6110–6115. (doi:10.1073/pnas.1423853112) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Thacker CE. 2017. Patterns of divergence in fish species separated by the Isthmus of Panama. BMC Evol. Biol. 17, 111 (doi:10.1186/s12862-017-0957-4) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hooghiemstra H, van der Hammen T. 1998. Neogene and Quaternary development of the Neotropical rain forest: the forest refugia hypothesis, and a literature overview. Earth Sci. Rev. 44, 147–183. (doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(98)00027-0) [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pirie MD, Chatrou LW, Mols JB, Erkens RHJ, Oosterhof J. 2006. ‘Andean-centred’ genera in the short-branch clade of Annonaceae: testing biogeographical hypotheses using phylogeny reconstruction and molecular dating. J. Biogeogr. 33, 31–46. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2005.01388.x) [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chaowasku T, Thomas DC, van der Ham RWJM, Smets EF, Mols JB, Chatrou LW. 2014. A plastid DNA phylogeny of tribe Miliuseae: insights into relationships and character evolution in one of the most recalcitrant major clades of Annonaceae. Am. J. Bot. 101, 691–709. (doi:10.3732/ajb.1300403) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ortiz-Rodriguez AE, Ruiz-Sanchez E, Ornelas JF. 2016. Phylogenetic relationships among members of the Neotropical clade of Miliuseae (Annonaceae): generic non-monophyly of Desmopsis and Stenanona. Syst. Bot. 41, 815–822. (doi:10.1600/036364416X693928) [Google Scholar]

- 27.Couvreur TLP, Porter-Morgan H, Wieringa JJ, Chatrou LW. 2011. Little ecological divergence associated with speciation in two African rain forest tree genera. BMC Evol. Biol. 11, 296 (doi:10.1186/1471-2148-11-296) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pirie MD, Kankainen S, Maas PJM. 2005. Revision and phylogeny of Cremastosperma (Annonaceae). In Phd thesis, Cremastosperma (and other evolutionary digressions). molecular phylogenetic, biogeographic, and taxonomic studies in neotropical annonaceae (ed. Pirie MD.), pp. 87–191. Utrecht, The Netherlands: Universiteit Utrecht. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chatrou LW. 1998. Changing genera: systematic studies in Neotropical and West African Annonaceae. PhD Thesis Utrecht University, Utrecht, The Netherlands. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chatrou LW. 1997. Studies in Annonaceae XXVIII. Macromorphological variation of recent invaders in northern Central America: the case of Malmea (Annonaceae). Am. J. Bot. 84, 861–869. (doi:10.2307/2445822) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mols JB, Gravendeel B, Chatrou LW, Pirie MD, Bygrave PC, Chase MW, Kessler PJA. 2004. Identifying clades in Asian Annonaceae: monophyletic genera in the polyphyletic Miliuseae. Am. J. Bot. 91, 590–600. (doi:10.3732/ajb.91.4.590) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Richardson JE, Chatrou LW, Mols JB, Erkens RHJ, Pirie MD. 2004. Historical biogeography of two cosmopolitan families of flowering plants: Annonaceae and Rhamnaceae. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B 359, 1495–1508. (doi:10.1098/rstb.2004.1537) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pirie MD, Chatrou LW, Erkens RHJ, Maas JW, Van der Niet T, Mols JB, Richardson JE. 2005. Phylogeny reconstruction and molecular dating in four Neotropical genera of Annonaceae: the effect of taxon sampling in age estimations. In Plant species-level systematics: new perspectives on pattern and process (eds Bakker FT, Chatrou LW, Gravendeel B, Pelser PB), pp. 149–174. Liechtenstein, Germany: Regnum Vegetabile 143, A. R. G. Gantner Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pirie MD, Balcázar Vargas MP, Botermans M, Bakker FT, Chatrou LW. 2007. Ancient paralogy in the cpDNA trnL-F region in Annonaceae: implications for plant molecular systematics. Am. J. Bot. 94, 1003–1016. (doi:10.3732/ajb.94.6.1003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lewis CE, Doyle JJ. 2001. Phylogenetic utility of the nuclear gene malate synthase in the palm family (Arecaceae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 19, 409–420. (doi:10.1006/mpev.2001.0932) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Simmons MP, Ochoterena H. 2000. Gaps as characters in sequence-based phylogenetic analyses. Syst. Biol. 49, 369–381. (doi:10.1080/10635159950173889) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pirie MD, Maas PJM, Wilschut RA, Melchers-Sharrott H, Chatrou LW. 2018. Data from: Parallel diversifications of Cremastosperma and Mosannona (Annonaceae), tropical rainforest trees tracking Neogene upheaval of South America. Dryad Digital Repository (http://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.49g85) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Swofford DL. 2003. PAUP*. Phylogenetic analysis using parsimony (* and other methods), version 4. Sunderland, MA: Sinauer Associates.

- 39.Vaidya G, Lohman DJ, Meier R. 2011. SequenceMatrix: concatenation software for the fast assembly of multi-gene datasets with character set and codon information. Cladistics 27, 171–180. (doi:10.1111/j.1096-0031.2010.00329.x) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lanfear R, Calcott B, Ho SYW, Guindon S. 2012. PartitionFinder: combined selection of partitioning schemes and substitution models for phylogenetic analyses. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1695–1701. (doi:10.1093/molbev/mss020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stamatakis A. 2006. RAxML-VI-HPC: maximum likelihood-based phylogenetic analyses with thousands of taxa and mixed models. Bioinformatics 22, 2688–2690. (doi:10.1093/bioinformatics/btl446) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ronquist F, et al. 2012. MrBayes 3.2: efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model choice across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 61, 539–542. (doi:10.1093/sysbio/sys029) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stamatakis A, Hoover P, Rougemont J. 2008. A rapid bootstrap algorithm for the RAxML web servers. Syst. Biol. 57, 758–771. (doi:10.1080/10635150802429642) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Miller MA, Pfeiffer W, Schwartz T.. 2010. Creating the CIPRES Science Gateway for inference of large phylogenetic trees. In 2010 gateway computing environments workshop (GCE), pp. 1–8. New Orleans, LA: IEEE. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pirie MD, Humphreys AM, Antonelli A, Galley C, Linder HP. 2012. Model uncertainty in ancestral area reconstruction: a parsimonious solution? Taxon 61, 652–664. (doi:10.5167/uzh-64515) [Google Scholar]

- 46.Drummond AJ, Suchard MA, Xie D, Rambaut A. 2012. Bayesian phylogenetics with BEAUti and the BEAST 1.7. Mol. Biol. Evol. 29, 1969–1973. (doi:10.1093/molbev/mss075) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pirie MD, Doyle JA. 2012. Dating clades with fossils and molecules: the case of Annonaceae. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 169, 84–116. (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2012.01234.x) [Google Scholar]

- 48.Graur D, Martin W. 2004. Reading the entrails of chickens: molecular timescales of evolution and the illusion of precision. Trends Genet. 20, 80–86. (doi:10.1016/j.tig.2003.12.003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Schenk JJ. 2016. Consequences of secondary calibrations on divergence time estimates. PLoS ONE 11, e0148228 (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148228) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mohr BAR, Bernardes-de-Oliveira MEC. 2004. Endressinia brasiliana, a magnolialean angiosperm from the Lower Cretaceous Crato Formation (Brazil). Int. J. Plant Sci. 165, 1121–1133. (doi:10.1086/423879) [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takahashi M, Friis EM, Uesugi K, Suzuki Y, Crane PR. 2008. Floral evidence of Annonaceae from the Late Cretaceous of Japan. Int. J. Plant Sci. 169, 908–917. (doi:10.1086/589693) [Google Scholar]

- 52.Massoni J, Couvreur TL, Sauquet H. 2015. Five major shifts of diversification through the long evolutionary history of Magnoliidae (angiosperms). BMC Evol. Biol. 15, 49 (doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0320-6) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rambaut A, Suchard MA, Xie D, Drummond AJ. 2014. Tracer v1.6. See http://tree.bio.ed.ac.uk/software/tracer/.

- 54.Filer DL. 2008. BRAHMS Version 7. See http://herbaria.plants.ox.ac.uk/bol/brahms/software.

- 55.Phillips SJ, Anderson RP, Schapire RE. 2006. Maximum entropy modeling of species geographic distributions. Ecol. Modell. 190, 231–259. (doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2005.03.026) [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elith J, et al. 2006. Novel methods improve prediction of species' distributions from occurrence data. Ecography 29, 129–151. (doi:10.1111/j.2006.0906-7590.04596.x) [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wisz MS, et al. 2008. Effects of sample size on the performance of species distribution models. Divers. Distrib. 14, 763–773. (doi:10.1111/j.1472-4642.2008.00482.x) [Google Scholar]

- 58.van Proosdij ASJ, Sosef MSM, Wieringa JJ, Raes N. 2016. Minimum required number of specimen records to develop accurate species distribution models. Ecography 39, 542–552. (doi:10.1111/ecog.01509) [Google Scholar]

- 59.Metz CE. 1978. Basic principles of ROC analysis. Semin. Nucl. Med. 8, 283–298. (doi:10.1016/S0001-2998(78)80014-2) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Raes N, ter Steege H. 2007. A null-model for significance testing of presence-only species distribution models. Ecography 30, 727–736. (doi:10.1111/j.2007.0906-7590.05041.x) [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lobo JM, Jiménez-Valverde A, Real R. 2008. AUC: a misleading measure of the performance of predictive distribution models. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 17, 145–151. (doi:10.1111/j.1466-8238.2007.00358.x) [Google Scholar]

- 62.Chatrou LW, et al. 2012. A new subfamilial and tribal classification of the pantropical flowering plant family Annonaceae informed by molecular phylogenetics. Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 169, 5–40. (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2012.01235.x) [Google Scholar]

- 63.Warren DL, Glor RE, Turelli M. 2010. ENMTools: a toolbox for comparative studies of environmental niche models. Ecography 33, 607–611. (doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2009.06142.x) [Google Scholar]

- 64.Pennington RT, Dick CW. 2011. Diversification of the Amazonian flora and its relation to key geological and environmental events: a molecular perspective. In Amazonia: landscape and species evolution (eds Hoorn C, Wesselingh FP), pp. 373–385. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dick CW, Abdul-Salim K, Bermingham E. 2003. Molecular systematic analysis reveals cryptic Tertiary diversification of a widespread tropical rain forest tree. Am. Nat. 162, 691–703. (doi:10.1086/379795) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Dexter KG, Lavin M, Torke BM, Twyford AD, Kursar TA, Coley PD, Drake C, Hollands R, Pennington RT. 2017. Dispersal assembly of rain forest tree communities across the Amazon basin. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 114, 2645–2650. (doi:10.1073/pnas.1613655114) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Erkens RHJ, Chatrou LW, Maas JW, van der Niet TT, Savolainen V. 2007. A rapid diversification of rainforest trees (Guatteria; Annonaceae) following dispersal from Central into South America. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 44, 399–411. (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.02.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Smith BT, Harvey MG, Faircloth BC, Glenn TC, Brumfield RT. 2014. Target capture and massively parallel sequencing of ultraconserved elements for comparative studies at shallow evolutionary time scales. Syst. Biol. 63, 83–95. (doi:10.1093/sysbio/syt061) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Scotti-Saintagne C, et al. 2013. Amazon diversification and cross-Andean dispersal of the widespread Neotropical tree species Jacaranda copaia (Bignoniaceae). J. Biogeogr. 40, 707–719. (doi:10.1111/j.1365-2699.2012.02797.x) [Google Scholar]

- 70.Antonelli A, Nylander JAA, Persson C, Sanmartín I. 2009. Tracing the impact of the Andean uplift on neotropical plant evolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 9749–9754. (doi:10.1073/pnas.0811421106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Roncal J, Kahn F, Millan B, Couvreur TLP, Pintaud JC. 2013. Cenozoic colonization and diversification patterns of tropical American palms: evidence from Astrocaryum (Arecaceae). Bot. J. Linn. Soc. 171, 120–139. (doi:10.1111/j.1095-8339.2012.01297.x) [Google Scholar]

- 72.Barfod AS, Trénel P, Borchsenius F. 2010. Drivers of diversification in the vegetable ivory palms (Arecaceae: Ceroxyloideae, Phytelepheae) – vicariance or adaptive shifts in niche traits? In Diversity, phylogeny, and evolution in the monocotyledons (eds Seberg O, Peterson G, Barfod A, Davis JI), pp. 225–243. Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Winterton C, Richardson JE, Hollingsworth M, Clark A. 2014. Historical biogeography of the neotropical legume genus Dussia: the Andes, the Panama Isthmus and the Chocó. In Paleobotany and biogeography (eds WD Stevens, OM Montiel, PH Raven), pp. 389–404. St Louis, MO: Missouri Botanical Garden. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Richardson JE, Whitlock BA, Meerow AW, Madriñán S. 2015. The age of chocolate: a diversification history of Theobroma and Malvaceae. Front. Ecol. Evol. 3, 1–14. (doi:10.3389/fevo.2015.00120) [Google Scholar]

- 75.Pérez-Escobar OA, Gottschling M, Chomicki G, Condamine FL, Klitgård BB, Pansarin E, Gerlach G. 2017. Andean mountain building did not preclude dispersal of lowland epiphytic orchids in the neotropics. Sci. Rep. 7, 4919 (doi:10.1038/s41598-017-04261-z) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Pérez-Escobar OA, Chomicki G, Condamine FL, Karremans AP, Bogarín D, Matzke NJ, Silvestro D, Antonelli A. 2017. Recent origin and rapid speciation of Neotropical orchids in the world's richest plant biodiversity hotspot. New Phytol. 215, 891–905. (doi:10.1111/nph.14629) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wesselingh FP, Räsänen ME, Irion G, Vonhof HB, Kaandorp R, Renema W, Romero Pittman L, Gingras M. 2002. Lake Pebas: a palaeoecological reconstructionof a Miocene, long-lived lake complex in western Amazonia. Cainozoic Res. 1, 35–81. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lötters S, van der Meijden A, Rödder D, Köster TE, Kraus T, La Marca E, Haddad CFB, Veith M. 2010. Reinforcing and expanding the predictions of the disturbance vicariance hypothesis in Amazonian harlequin frogs: a molecular phylogenetic and climate envelope modelling approach. Biodivers. Conserv. 19, 2125–2146. (doi:10.1007/s10531-010-9869-y) [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chatrou LW, Pirie MD. 2005. Three new rarely collected or endangered species of Annonaceae from Venezuela. Blumea 50, 33–40. (doi:10.3767/000651905X623265) [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schneider J V., Zizka G. 2017. Phylogeny, taxonomy and biogeography of Neotropical Quiinoideae (Ochnaceae s.l.). Taxon 66, 855–867. (doi:10.12705/664.4) [Google Scholar]

- 81.Kursar TA, et al. 2009. The evolution of antiherbivore defenses and their contribution to species coexistence in the tropical tree genus Inga. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 106, 18 073–18 078. (doi:10.1073/pnas.0904786106) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Alcantara S, Ree RH, Martins FR, Lohmann LG. 2014. The effect of phylogeny, environment and morphology on communities of a lianescent clade (Bignonieae-Bignoniaceae) in Neotropical biomes. PLoS ONE 9, 1–10. (doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0090177) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Deblauwe V, et al. 2016. Remotely sensed temperature and precipitation data improve species distribution modelling in the tropics. Glob. Ecol. Biogeogr. 25, 443–454. (doi:10.1111/geb.12426) [Google Scholar]

- 84.Cody S, Richardson JE, Rull V, Ellis C, Pennington RT. 2010. The great American biotic interchange revisited. Ecography 33, 326–332. (doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06327.x) [Google Scholar]

- 85.O'Dea A, et al. 2016. Formation of the Isthmus of Panama. Sci. Adv. 2, e1600883 (doi:10.1126/sciadv.1600883) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Patané JSL, Weckstein JD, Aleixo A, Bates JM. 2009. Evolutionary history of Ramphastos toucans: molecular phylogenetics, temporal diversification, and biogeography. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 53, 923–934. (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2009.08.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Lutz HL, Weckstein JD, Patané JSL, Bates JM, Aleixo A. 2013. Biogeography and spatio-temporal diversification of Selenidera and Andigena toucans (Aves: Ramphastidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 69, 873–883. (doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2013.06.017) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Sauquet H. 2017. Unravelling the history of Neotropical plant diversification. Peer Community Evol. Biol. 100033, 1–2. (doi:10.24072/pci.evolbiol.100033) [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- Pirie MD, Maas PJM, Wilschut RA, Melchers-Sharrott H, Chatrou LW. 2018. Data from: Parallel diversifications of Cremastosperma and Mosannona (Annonaceae), tropical rainforest trees tracking Neogene upheaval of South America. Dryad Digital Repository (http://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.49g85) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

DNA sequences used in this study have been deposited in GenBank, sequence matrices and phylogenetic trees are available from TreeBase (http://purl.org/phylo/treebase/phylows/study/TB2:S20848) and matrices, trees, distribution data and environmental layers used for niche modelling are available from Dryad (https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.49g85 [37]).