Abstract

Background:

Popular media typically portray yoga as an exercise or posture practice despite the reality that yoga comprised eight practices (called limbs) including ethical behavior, conscious lifestyle choices, postures, breathing, introspection, concentration, meditation, and wholeness.

Aim:

This study assessed the comprehensiveness of yoga practice as represented in articles in the popular yoga magazine, Yoga Journal. It explored the degree to which articles referenced each of the eight limbs of yoga and other contents (e.g., fitness, spirituality).

Materials and Methods:

Six coders were trained to reliably and independently review 702 articles in 33 Yoga Journal issues published between 2007 and 2014, coding for the limbs of yoga and other contents.

Results:

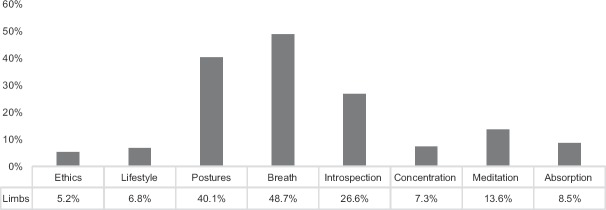

Breathing and postures were most frequently referenced, which were covered in 48.7% and 40.1% of articles. Internal practices were covered in 36.5% of articles with introspection being the most and concentration the least commonly referred to internal practices. Ethical and lifestyle practices were least frequently covered (5.2% and 6.8%). Since 2007, coverage of postures steadily increased, whereas contents related to the other limbs steadily decreased. The most frequent other contents related to fitness (31.7%), spirituality (20.8), and relationships (18.7%) coverage of these did not change across time.

Conclusions:

Representation of yoga in articles contained in the most popular yoga magazine is heavily biased in favor of physical practices. Recommendations are offered about how to shift media representation of yoga to make the heart of the practice more accessible to individuals who could experience health benefits but currently feel excluded from the practice.

Keywords: Limbs of yoga, media representation of yoga, perceptions of yoga, yoga

Introduction

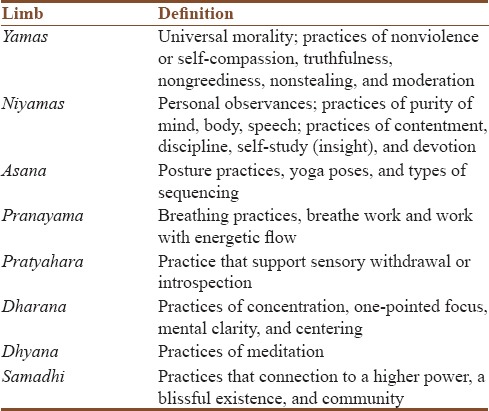

Yoga can be viewed as an ancient psychology that aims to reduce human suffering by training and unifying mind, body, and spirit.[1] Yoga from this perspective represents a commitment to a lifestyle that is deeply rooted in mindfulness and firmly guided by eight distinct practices (also called limbs) first outlined in the Yoga Sutras (Patanjali, ~ 500 BC).[2] These eight limbs or practices are summarized in [Table 1], which include ethical and lifestyle considerations, physical postures, breathing exercises, introspective and concentrative practices, meditation, and absorption or union. The limbs represent practical methods of physical and mental training and provide the mean to attain self-regulation, resilience, and mental, as well as physical wellness. Overwhelming research evidence has been accumulated to demonstrate the effectiveness of yoga in helping practitioners to reach these goals.[3,4,5]

Table 1.

Eight limbs of yoga as defined for study coding

Much of the therapeutic effectiveness of yoga hinges on the integrated practice of all limbs, rather than the isolated practice of single aspects of yoga.[6,7,8,9] In addition, practitioners whose motivation for practice go beyond that of physical benefit (e.g., psycho-spiritual reasons) are more likely to maintain a regular home practice.[10] Unfortunately, perceptions of yoga are stereotypically limited in nature[11,12] and most often focus primarily on its physical aspects with a target audience that consists largely of young, white, educated, healthy, and wealthy females.[13,14] Media portrayals of yoga reinforce these stereotypes with images and articles about yoga that perpetuate stereotypes about what constitutes a yoga practice and who chooses to engage in it.

This limited and biased portrayal of yoga in the public media has the potential to lead to injuries and limitations in access to the practice for the very individuals who may benefit the most.[15,16] For example, biased and noncomprehensive media portrayal of yoga may lead to unsafe practice through images or contents that suggest a particular shape or requirement for a yoga practice. Since media representations have the power to distort an individual's perception of what is desirable, viewers of unrealistic images may force their bodies into less than healthful shapes or to develop unhealthy lifestyle habits.[17,18] Thus, it is not surprising that yoga injuries and extreme physical yoga practices have captured the popular press's attention[19,20] and have potentially redirected potential beneficiaries from the practice. Another potential negative consequence from biased media representations of yoga arises from the reality that readers of popular magazines internalize social norms about the images and contents to which they are exposed. When the yoga that is presented in the media is either limited in scope (typically to a physical practice) or target (typically slender, white, educated women) many individuals who may benefit will be dissuaded from even trying to engage in the practice.[15] If the yoga that is shown and discussed represents the practice in a manner that is unrealistic or unattainable, readers who compare themselves to such representations may respond with negative self-perceptions. For example, internalization of unrealistic social norms has been shown to contribute to readers’ subsequent body dissatisfaction, low self-esteem, and the potential development of eating disorders[17,21] after viewing unattainable images.

Current study

The current study sought to assess the scope of practice components of the written representation of yoga in one of the yoga's most popular magazines. Yoga Journal is a popular magazine that focuses on health and fitness and reported to have nearly two million readers worldwide (http://www3.yogajournal.com/advertise). To assess the comprehensiveness of the yoga practice represented, the current study evaluated the contents of 702 articles in 33 issues of Yoga Journal published between 2007 and 2014 (as part of a larger study that explored yoga's representation throughout this magazine's content including graphics, advertisements, and articles). Each article was coded for explicit or implicit mentions of the eight limbs of yoga, as well as for references to body weight, fitness or flexibility, appearance, relationships, sexuality, sexualized content, gender roles, money, spirituality, age, and race or ethnicity.

Methods

Materials

All issues of Yoga Journals from February 2007 to December 2014 (n = 170) were collected for review. A stratified random sample (one issue per season) of 33 issues was drawn from this pool of magazines. To evaluate each of the 702 articles included in the selected issues, a rating form was developed that comprised forty questions tapping various contents as well as type of article, type of feature, article size, and gender of writer. To standardize ratings, most questions offered discrete response choices in drop-down menus. Specific content questions related to each of the eight limbs of yoga (implicit and explicit mentions), as well as body weight, fitness or flexibility, appearance, relationships, explicit sexuality-related content (i.e., discussing a range of topics regarding human sexuality in a healthful way), sexualized treatment of content that is not intrinsically sexual (i.e., sexualized presentation of clothing, body, or body enhancements), stereotypical gender roles, money, spirituality, age, and race or ethnicity.

Raters

Article coders were graduate students and faculty from a yoga research team at a small, private university in the Northwestern United States. The coding team comprised 15 individuals ranging in age from 26 to 54 years, 2 were men and 13 women, 26% were racially or ethnically diverse, yoga experience ranged from 4 to 36 years, and six team members were certified as yoga teachers. Three teams of coders were created for the larger study to code three major aspects under study: graphics, advertisements, and articles. The raters for the articles team (relevant to this paper) were randomly selected (n = 5) from the larger research team.

Intercoder reliability

Coding rubrics were established in collaborative efforts that included the entire research team and focused on the establishment of variables of interest, definitions for these variables, and operationalization of decision rules for coding. Once the overall rubrics were established, separate codebooks were established (one for visuals and one for article content). The 15-member research team was assigned to three groups of coders and each group was trained for inter-rater reliability on their area of specialization (i.e., either content or visuals in ads or visuals in graphics). For each coding team, inter-rater reliability was established across several training sessions. Specific to the article coding team, each team member was trained to recognize content as related to the eight limbs of yoga and the other content variables to rated. The team then jointly practiced the coding to standardize responses for each item to be rated (using issues of the journal not included in the final study). Once they established consistent consensus on content coding, they each began coding the same contents separately, reconvened to compare coding, discuss discrepancies, and continuously refine the codebooks and decision rules. This process continued until the coders were at least 90% consistent in their coding. At that point, coders were randomly assigned issues to code independently. Throughout the coding process, each team met to conduct drift checks to continue to ensure ongoing intercoding reliability.

Data analyses

Analyses were descriptive, calculating frequencies for the absence or presence of contents of interest. Additional trend line analyses looked at patterns across the years to explore the significance of changes in content coverage across time.

Results

Findings related to the eight limbs of yoga

As shown in Figure 1, the most frequently referenced limbs were the physical practices of pranayama or breathe work (explicitly covered in 48.7% of all articles) and asana or postures (40.1%). The internal practices were covered in 254 (or 36.5%) of the articles, with introspection practices being the most commonly covered internal practice, noted in 26.6% of articles. It was followed by meditation (13.7%), absorption (8.5%), and concentration (7.3%). Ethical and lifestyle practices, the foundational limbs of yoga, were the least frequently explicitly referenced limbs, each noted in fewer than 10% of all articles (in 5.2% and 6.8% of articles, respectively).

Figure 1.

The eight limbs of yoga

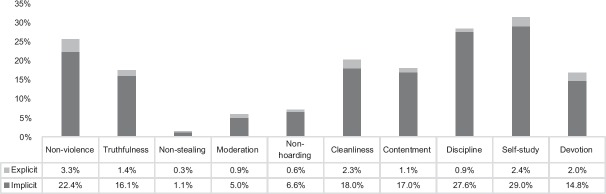

Figures 1 and 2 reveal that implicit mentions of the ethical and lifestyle practices were slightly higher, with up to 262 (or 37.6%) of articles indirectly dealing with contents that were related to topics of ethics and 438 (or 62.9%) with topics of lifestyle choices. It must be noted that these implicit references were just that the articles did not identify the mention of these practices as being a part of a systematic yoga practice but simply tapped into a content that could be attributed in traditional yoga circles to one of these two limbs. For example, the topic of discipline (a lifestyle practice) may be indirectly addressed (and thus coded as implicitly present) in the context of an article primarily dealing with posture practice. Individually, the ethical foundation that was most commonly referenced either implicitly (22.4%) and explicitly (3.3%) was nonviolence. The least common lifestyle practice referenced by the ethical foundation was nonstealing (1.1% and 0.3%). The most common lifestyle practices implicitly referenced by the ethical foundation were self-study and discipline (in 29% and 27.6% of articles, respectively), though their explicit mention was significantly lower (at 2.0% and 0.9%). The most common explicitly referenced lifestyle practice was self-study (2.4%), closely followed by cleanliness (2.3%) and devotion (2.0%).

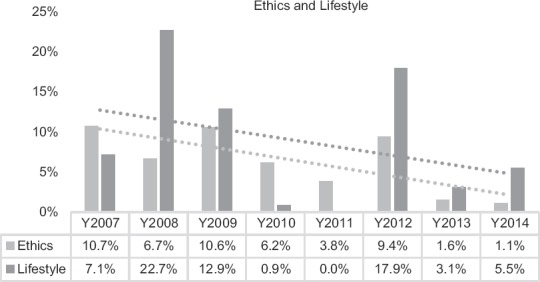

Figure 2.

Ethical and lifestyle practices

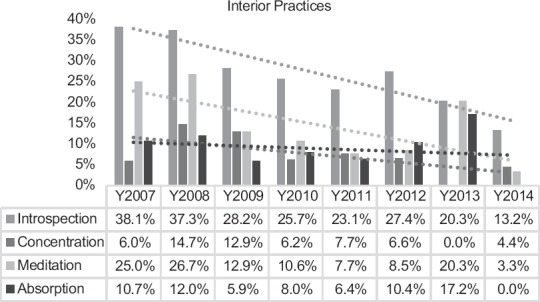

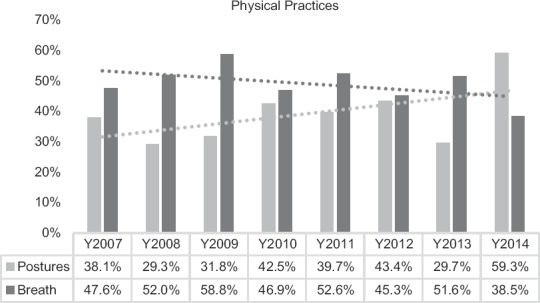

Changes in content related to the eight limbs across time

Figures 3-5 reveal that there have been notable changes in the proportion of article contents as related to the eight limbs across time. Contents related to explicit ethics and lifestyle aspects of yoga philosophy decreased from a 3-year rolling average of 9.3% and 14.3%, respectively, in 2007–2009 to a rolling 3-year average in 2012–2014 of 4.0% and 8.9%. Similar declines in coverage were noted for all interior yoga practices (introspection, concentration, meditation, and absorption), with the greatest decline noted for introspection (with a 3-year rolling average of 34.5% dropping to 20.3% of articles referencing this important limb of yoga). Mention of meditation dropped from an earlier average of 21.5% to a current rolling average of 10.7%. Even breathing practices were mentioned with less frequency in later years (3-year rolling average of 45.1%) as compared to earlier years (with a 3-year rolling average of 52.8%). The only limb of yoga that saw a positive trend in the amount of coverage afforded to it in the articles was posture practice. In 2007–2009, the 3-year rolling average was 33.1% as compared to 44.2% in 2012–2014. In the final year of analysis, posture practice exceeded all other limbs in terms of the percentage of articles devoted to this aspect of yoga.

Figure 3.

Ethics and lifestyle content across time

Figure 5.

Interior practices content across time

Figure 4.

Physical practices content across time

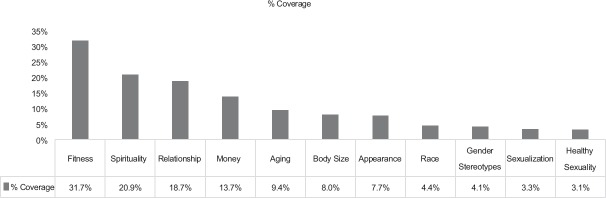

Findings related to other article contents

Figure 6 shows that physical fitness (including flexibility) was the most commonly covered content in the Yoga Journal articles, with 31.7% of articles being devoted to this topic. This physical dimension of yoga was followed by articles about spirituality (including religion) and relationship, which was cited in 20.8% and 18.7% of articles, respectively. Money matters were addressed in 13.7%. Aging was referenced in nearly 10% of articles followed closely by body size (weight and shape) in 8.0% and appearance in 7.7%. The least referenced contents were related to gender, race, and sexuality, all mentioned in fewer than 5% of articles. Trendline analyses revealed that these patterns of coverage have been consistent across time since 2007.

Figure 6.

Other contents covered in articles

Discussion

As expected, findings point to a somewhat uneven representation of yoga philosophy in Yoga Journal's articles. The aspects of yoga that were represented most frequently within the articles were breathing practices (pranayama) and postures (asanas). The other six limbs lagged significantly behind these physical practices, receiving minimal implicit and much less explicit attention. Although physical practices are of course a major aspect of yoga, they are only a fraction of the entire system and lack major foundational principles of an integrated practice. If Yoga Journal represented all of the practices evenly, each limb would receive coverage in approximately 12.4% of articles. However, by the year 2015, nearly 60% of articles covered only posture practices and as few as 3%–4% covered concentration or meditation, while none covered absorption.

Although it is understandable that posture practices (and fitness contents, for that matter) are prioritized by Yoga Journal, given our physically focused culture and marketability of the asanas, this emphasis distorts the essence of yoga which is much broader than stretching and strengthening the body. Even though there are some implicit mentions of the ethical practices in the articles, the messages publicized using the physical practice in the graphics and advertisements overshadow any potential dissemination of the other limbs. Certainly, references to fitness and physical postures are important, particularly given that research has provided ample evidence that exercise is an important staple of a healthy lifestyle.[22,23,24] However, the emphasis on postures in both articles and accompanying graphics, along with the underrepresentation of the ethical, lifestyle, and interior practices of yoga, may exclude a large portion of the population who could be well-served by yoga, but who do not see themselves in the asana pictures that typically accompany these articles.[11,15,25,26]

Indeed, ethics and lifestyle practices may be the most profound limbs that yoga has to offer to support significant life changes and a sustainable practice. Overlooking yoga practices such as the ethical practices (yamas – including nonviolence and nonstealing) may adversely affect the physical practice of yoga, leading practitioners to overvalue esthetics over inner peace and transformation. Asana practice not balanced, for example, by nonviolence may lead to the type of posture practice that leads to injuries and competitiveness.[27,28] Similarly, physical practices to the exclusion of lifestyle commitments (niyamas – including cleanliness, self-study, and devotion) are likely simple fitness practices that fail to realize the deeper benefits of yoga that facilitate emotional self-regulation, stress management, and healthier coping styles.[29] If the media fails to use its platform to expose the general public to the interior limbs of yoga, then the media may similarly deprive purely physical practitioners the additional yogic benefits of connection, community, and compassion. Perhaps most importantly, however, overemphasis on physical practices decreases accessibility to those who do not fit Yoga Journal's and other popular media's representation of a “yogi” and leaves out large groups of individuals who would otherwise benefit greatly from the practice.[15]

Recommendations and implications

Based on the data collected, it is important to implement significant changes in how yoga is represented in the media. To increase accessibility and utilization of yoga, the media need to present a more holistic picture of yoga. Currently, although yoga promotes integration of the mind, body, and spirit, the media gives the impression that yoga's focus is exclusively on sculpting the body, virtually ignoring mind and spirit. Following are a set of recommendations for Yoga Journal and similar publications to increase the visibility of yoga as a lifestyle that offers a pathway into better emotional self-regulation, increased self-awareness, and deeper human connection.

Recommendation #1: Broader media coverage of all limbs of yoga

Major yoga publication needs to embrace a more rounded embodiment of yoga, incorporating all the limbs of yoga in somewhat even proportions. More exposure to all of the limbs promotes a better understanding of all of the features of yoga and allows readers to have autonomy to choose what kind of practices might be the best for them. By only showing certain aspects of the practice, the readers’ choices are limited. The increased popularity of yoga is exciting and owes much to its greater visibility in the popular media. However, the current depiction of yoga in the popular media as exemplified by Yoga Journal is drifting from yoga's deeper philosophical roots and becoming more of a fashion statement rather than a holistic lifestyle. Indeed, the drift appears to be increasing even just within the short timeframe covered by our study. If this direction is not corrected, yoga may eventually be entirely misrepresented as a physical fitness practice and lend itself to being abused for material gain.

Recommendation #2: Broader coverage of the pervasive benefits of yoga

Yoga has been demonstrated to have far-reaching health and wellness effects.[28,29,30,31,32] It is no longer a question of whether yoga supports a healthier lifestyle; it is now a question of how to help the general population to recognize the significant health and mental health benefits that arise from the practice. Media outlets such as Yoga Journal are in the unique position of having a dedicated readership that could learn much about the enhancements to their personal lives from yoga. It is recommended that a greater focus should be placed on the health and mental health aspects of a yoga practice, with an emphasis that these benefits not only are derived from a posture practice but also concurrently from committed, ethical choices and interior practices, such as meditation and mindfulness. Such articles could also help entice those who may most benefit from the practice to try yoga. Perhaps even more importantly, it may disseminate information among health professionals that yoga is a viable complementary treatment for many health conditions. In turn, such broad-based coverage may convince the providers to make referrals for their patients to yoga, increasing its accessibility to exactly those individuals who derive the greatest health and mental health benefits. In a previous study, we found that health professional students knew mostly about the physical aspects of yoga and less about its health benefits and other practices.[12] Thus, they were less inclined to make referrals to yoga, despite the fact that their patients may derive benefit from the practice. Health professionals can use yoga as a resource for their patients[16] but only if they recognize, that in addition to the physical practices, yoga includes a variety of tools that can contribute to a healthier lifestyle.[33]

Recommendation #3: Inviting coverage of yoga as accessible to all

Current emphases in the popular media leave out many individuals. Additional content analyses revealed that race, gender, and similar aspects of being human were nearly entirely left out of the discussion.[25,26] This omission contributes to underrepresentation of certain population groups in yoga classes and keeps the practice limited to certain demographics of privilege.[13,14] Yoga can be a powerful tool for healing and self-study. It is recommended that yoga should be represented in a more inclusive way that includes all limbs to give practitioners and those new to yoga exposure to a comprehensive practice that offers something for everyone. Anyone who can breathe can do yoga; anyone who can sit or lie down with mindful awareness can do yoga; anyone who can pay attention can do yoga. Current media representations, however, suggest just the opposite, showing yoga as a practice exclusively for those individuals who can control and manipulate their bodies in extreme ways. By showing all aspects of yoga, the media can make a choice to offer autonomy to potential, new, and experienced practitioners to shape their own practice in ways that suit them optimally.

Conclusions

Although the media does hold power over what is exposed to the general public, the media is not solely responsible for creating a more holistic vision of yoga in Western culture. Teachers, teacher trainers, yoga therapists, and yoga researchers all share this responsibility. Thus, although the focus here has been on media coverage, profound shifts are needed in how yoga teachers are trained, in how yoga is taught – especially in some settings and how yoga is researched. Future research will be needed to clarify these changes and approaches. Increasingly, comprehensive media coverage of yoga can play an important role in this culture shift.

Financial support and sponsorship

Nil.

Conflicts of interest

There are no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

We gratefully acknowledge the contributions of the other yoga research team members: Jillian Freitas, Julia Ray, Elizabeth Alire, Gregory Arbo, Madison Davis, Kari Sulenes, Lauren Justice, Margaret Shean, Lisa Girasa, Leslie Butler, and Michael Wojtkowicz.

References

- 1.Emerson D, Hopper E. Overcoming Trauma through Yoga: Reclaiming Your Body. Berkeley (CA): North Atlantic Books; 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Satchidananda SS. The Yoga Sutras of Patanjali. 9th ed. Buckingham (VA): Integral Yoga Publications; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Elwy AR, Groessl EJ, Eisen SV, Riley KE, Maiya M, Lee JP, et al. A systematic scoping review of yoga intervention components and study quality. Am J Prev Med. 2014;47:220–32. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2014.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hayes M, Chase S. Prescribing yoga. Prim Care. 2010;37:31–47. doi: 10.1016/j.pop.2009.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Payne L, Gold T, Goldman E. Laguna Beach (CA): Basic Health Publications; 2014. Yoga Therapy and Integrative Medicine: Where Ancient Science Meets Modern Medicine. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Desikachar TK. The Heart of Yoga: Developing a Personal Practice. Rochester (VT): Inner Traditions International; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Iyengar BK. Light on Yoga. New York: Schocken; 1976. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kraftsow G. Yoga for Wellness: Healing with the Timeless Teachings of Viniyoga. New York: Penguin Arkana; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schiffmann E. Yoga: The Spirit and Practice of Moving into Stillness. New York: Pocket Books; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dittmann KA, Freedman MR. Body awareness, eating attitudes, and spiritual beliefs of women practicing yoga. Eat Disord. 2009;17:273–92. doi: 10.1080/10640260902991111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brems C, Justice L, Sulenes K, Girasa L, Ray J, Davis M, et al. Improving access to yoga: Barriers to and motivators for practice among health professions students. Adv Mind Body Med. 2015;29:6–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brems C, Colgan D, Freeman H, Freitas J, Justice L, Shean M, et al. Elements of yogic practice: Perceptions of students in healthcare programs. Int J Yoga. 2016;9:121–9. doi: 10.4103/0973-6131.183710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Birdee GS, Legedza AT, Saper RB, Bertisch SM, Eisenberg DM, Phillips RS. Characteristics of yoga users: Results of a national survey. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23:1653–8. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0735-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Park LC, Braun T, Siegel T. Who practices yoga? A systematic review of demographic, health-related, and psychosocial factors associated with yoga practice. J Behav Med. 2015;38:460–71. doi: 10.1007/s10865-015-9618-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Justice L, Brems C, Jacova C. Exploring strategies to enhance self-efficacy about starting a yoga practice. Ann Yoga Phys Ther. 2016;1:1012. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sulenes K, Freitas J, Justice L, Colgan DD, Shean M, Brems C. Underuse of yoga as a referral resource by health professions students. J Altern Complement Med. 2015;21:53–9. doi: 10.1089/acm.2014.0217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Grabe S, Ward LM, Hyde JS. The role of the media in body image concerns among women: A meta-analysis of experimental and correlational studies. Psychol Bull. 2008;134:460–76. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Milkie MA. Social comparisons, reflected appraisals, and mass media: The impact of pervasive beauty images on Black and White girls’ self-concepts. Soc Psychol Q. 1999;62:190–210. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lorr B. New York: St. Martin's Press; 2014. Hell-Bent: Obsession, Pain, and the Search for Something Like Transcendence in Competitive Yoga. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singleton M. Yoga Body: The Origins of Modern Posture Practice. New York: Oxford University Press; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hawkins N, Richards PS, Granley HM, Stein DM. The impact of exposure to the thin-ideal media image on women. Eat Disord. 2004;12:35–50. doi: 10.1080/10640260490267751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Codella R, Terruzzi I, Luzi L. Sugars, exercise and health. J Affect Disord. 2016 doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.10.035. In press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Edwards MK, Loprinizi PD. Experimentally increasing sedentary behavior results in increased anxiety in an active young adult population. J Affect Disord. 2016;204:166–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2016.06.045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wipfli B, Landers D, Nagoshi C, Ringenbach S. An examination of serotonin and psychological variables in the relationship between exercise and mental health. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2011;21:474–81. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0838.2009.01049.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Razmjou E, Vladagina N, Freeman H, Freitas J, Sulenes K, Michael P, et al. Popular Media Portrayals of Yoga: Limiting Access to a Beneficial Healthcare Practice. Paper Presented at: 144th Annual American Public Health Association Meeting and Exposition; 29 October-02 November 2016, Denver, CO. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Vladagina N, Freeman H, Razmjou E, Freitas J, Sulenes K, Michael P, et al. Media Images of Yoga Poses: Increasing Injury Instead of Access. Paper Presented at: 144th Annual American Public Health Association Meeting and Exposition; 29 October-02 November 2016, Denver, CO. 2016 [Google Scholar]

- 27.Le Corroller T, Vertinsky AT, Hargunani R, Khashoggi K, Munk PL, Ouellette HA. Musculoskeletal injuries related to yoga: Imaging observations. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2012;199:413–8. doi: 10.2214/ajr.11.7440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Park CL, Riley KE, Braun TD. Practitioners’ perceptions of yoga's positive and negative effects: Results of a National United States survey. J Bodywork Movement Ther. 2016;20:270–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jbmt.2015.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gard T, Noggle JJ, Park CL, Vago DR, Wilson A. Potential self-regulatory mechanisms of yoga for psychological health. Front Hum Neurosci. 2014;8:770. doi: 10.3389/fnhum.2014.00770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chandratreya S. Yoga: An evidence-based therapy. J Midlife Health. 2011;2:3–4. doi: 10.4103/0976-7800.83251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chong CS, Tsunaka M, Tsang HW, Chan EP, Cheung WM. Effects of yoga on stress management in healthy adults: A systematic review. Altern Ther Health Med. 2011;17:32–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lavey R, Sherman T, Mueser KT, Osborne DD, Currier M, Wolfe R. The effects of yoga on mood in psychiatric inpatients. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2005;28:399–402. doi: 10.2975/28.2005.399.402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brems C. A yoga stress reduction intervention for university faculty, staff, and graduate students. Int J Yoga. 2015;25:61–77. doi: 10.17761/1531-2054-25.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]