Abstract

Chronic kidney disease affects ∼10% of the world’s adult population: it is within the top 20 causes of death worldwide, and its impact on patients and their families can be devastating. World Kidney Day and International Women’s Day in 2018 coincide, thus offering an opportunity to reflect on the importance of women’s health, and specifically their kidney health, to the community and the next generations, as well as to strive to be more curious about the unique aspects of kidney disease in women, so that we may apply those learnings more broadly. Girls and women, who make up ∼50% of the world’s population, are important contributors to society as a whole and to their families. Gender differences continue to exist around the world in access to education, medical care and participation in clinical studies. Pregnancy is a unique state for women, offering an opportunity for diagnosis of kidney disease, and also a state where acute and chronic kidney diseases may manifest, and which may impact future generations with respect to kidney health. There are various autoimmune and other conditions that are more likely to impact women with profound consequences for child bearing, and for the fetus. Women have different complications on dialysis than men, and are more likely to be donors than recipients of kidney transplants. In this editorial, we focus on what we do and do not know about women, kidney health and kidney disease, and what we might learn in the future to improve outcomes worldwide.

Keywords: access to care, acute and chronic kidney disease, inequities, kidney health, women

Kidney Health and Women’s Health: a case for optimizing outcomes for present and future generations

Introduction

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) affects ∼10% of the world’s adult population: it is within the top 20 causes of death worldwide [1], and its impact on patients and their families can be devastating. World Kidney Day and International Women’s Day in 2018 coincide, thus offering an opportunity to reflect on the importance of women’s health, and specifically their kidney health, to the community and the next generations, as well as to strive to be more curious about the unique aspects of kidney disease in women, so that we may apply those learnings more broadly.

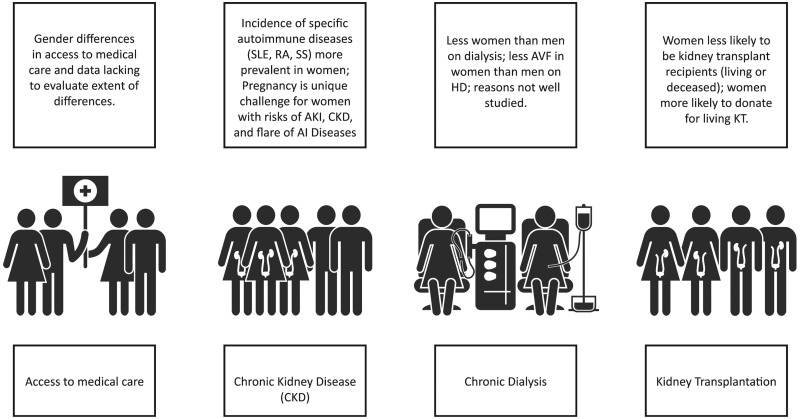

Girls and women, who make up ∼50% of the world’s population, are important contributors to society as a whole and to their families. Besides childbearing, women are essential in childrearing and contribute to sustaining family and community health. Women in the 21st century continue to strive for equity in business, commerce and professional endeavors, while recognizing that in many situations, equity does not exist. In various locations around the world, access to education and medical care is not equitable amongst men and women; women remain underrepresented in many clinical research studies, thus limiting the evidence based on which to make recommendations to ensure best outcomes (Figure 1).

Fig. 1.

Sex differences throughout the continuum of CKD care. AI, autoimmune; AVF, arteriovenous fistula; HD, hemodialysis; KT, kidney transplant.

In this editorial, we focus on what we do and do not know about women’s kidney health and kidney disease, and what we might learn in the future to improve outcomes for all.

What we know and do not know

Pregnancy

Pregnancy is a unique challenge and a major cause of acute kidney injury (AKI) in women of childbearing age [2]. AKI and preeclampsia (PE) may lead to subsequent CKD, but quantification of this risk is not known. PE is a risk factor for the future development of CKD and end-stage renal disease (ESRD) in the mother [3], and is the principal cause of AKI and maternal death in developing countries [4]. Furthermore, PE is linked to ‘small babies’, who are at risk for developing diabetes, metabolic syndrome, cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) and CKD in adulthood [5].

The presence of any degree of CKD has a negative effect on pregnancy, and given the increase in risk of CKD progression postpartum, it raises challenging ethical issues around conception and maintenance of pregnancies. Table 1 describes the various potential adverse effects of pregnancy on kidney health.

Table 1.

Adverse pregnancy outcomes in patients with CKD and in their offspring

| Term | Definition | Main issues |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal death | Death in pregnancy or within 1 week–1 month postpartum | Too rare to be quantified, at least in highly resourced settings, where cases are in the setting of severe flares of immunologic diseases (SLE in primis). Still an issue in AKI; and in low-resourced countries; not quantified in low-resourced countries, where it merges with dialysis need. |

| CKD progression | Decrease in GFR, rise in sCr, shift to a higher CKD stage | Differently assessed and estimated; may be linked to obstetric policy (anticipating delivery in the case of worsening of the kidney function); between 20 and 80% in advanced CKD. Probably not increased in early CKD stages. |

| Immunologic flares and neonatal SLE | Flares of immunologic diseases in pregnancy | Once thought to be increased in pregnancy, in particular in SLE, are probably a risk in patients who start pregnancy with an active disease, or with a recent flare-up. Definition of a ‘safe’ zone is not uniformly agreed; in quiescent, well-controlled diseases do not appear to be increased with respect to nonpregnant, carefully matched controls. |

| Transplant rejection | Acute rejection in pregnancy | Similar to SLE, rejection episodes are not increased with respect to matched controls; may be an issue in unplanned pregnancies, in unstable patients. |

| Abortion | Fetal loss, before 21–24 gestational weeks | May be increased in CKD, but data are scant. An issue in immunologic diseases (eventually, but not exclusively linked to the presence of LLAC) and in diabetic nephropathy. |

| Stillbirth | Delivery of a nonviable infant, after 21–24 gestational weeks | Probably not increased in early CKD, maybe an issue in dialysis patients; when not linked to extreme prematurity, may specifically linked to SLE, immunologic diseases and diabetic nephropathy. |

| Perinatal death | Death within 1 week–1 month from delivery | Usually a result of extreme prematurity, which bears a risk of respiratory distress, neonatal sepsis and cerebral hemorrhage. |

| Small, very small baby | A baby weighing <2500–1500 g at birth | Has as to be analyzed with respect to gestational age. |

| Preterm, early extremely preterm | Delivery before 37–34 or 28 completed gestational weeks | Increase in risk of preterm and early preterm delivery across CKD stages; extremely preterm may be an important issue in undiagnosed or late-referred CKD and PE-AKI. |

| SGA (IUGR) | <5th or <10th centile for gestational age | Strictly and inversely related to preterm delivery; SGA and IUGR are probably related to risk for hypertension, metabolic syndrome and CKD in adulthood. |

| Malformations | Any kind of malformations | Malformations are not increased in CKD patients not treated by teratogen drugs (MMF, mTor inhibitors, ACEi, ARB); exception: diabetic nephropathy (attributed to diabetes); hereditary diseases, such as PKD, reflux nephropathy, CAKUT may be evident at birth. |

| Hereditary kidney diseases | Any kind of CKD | Several forms of CKD recognize a hereditary pattern or predisposition; besides PKD, reflux and CAKUT, Alport’s disease, IgA, kidney tubular disorders and mitochondrial diseases have a genetic background, usually evident in adulthood and not always clearly elucidated. |

| CKD—hypertension | Higher risk of hypertension and CKD in adulthood | Late maturation of nephrons results in a lower nephron number in preterm babies; the risks are probably higher in SGA–IUGR babies than in preterm babies adequate for gestational age. |

| Other long-term issues | Developmental disorders | Mainly due to prematurity, cerebral hemorrhage or neonatal sepsis, are not specific of CKD, but are a threat in all preterm babies. |

GFR, glomerular filtration rate; sCR, serum creatinine; LLAC, lupus-like anticoagulant; PE-AKI, preeclampsia acute kidney injury; SGA, small for gestational age; IUGR, intrauterine growth restriction; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; mTor, mechanistic target of rapamycin; ACEi, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor; ARB, angiotensin II receptor blockers; PKD, polycystic kidney disease; CAKUT, congenital anomalies of the kidney and urinary tract; IgA, immunoglobulin A.

Autoimmune diseases

Autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), rheumatoid arthritis (RA) and systemic scleroderma (SS) preferentially affect women and are characterized by systemic inflammation leading to target organ dysfunction, including kidneys. Sex differences in the incidence and severity of these diseases result from a complex interaction of hormonal, genetic and epigenetic factors (Table 2). The public health burden of autoimmune diseases is substantial, as a leading cause of morbidity and mortality among women throughout adulthood [6–8].

Table 2.

Sex differences in the incidence and severity of autoimmune diseases

| SLE | RA | SS | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peak incidence | Reproductive age | Perimenopausal | After 50–60 years | |

| Female/male ratio | Peak 15: 1 | Peak 4: 1 | Peak 14: 1 | |

| Total 9: 1 | After 60 years 1: 1 | Total 3: 1 | ||

| Influence of estrogen | High levels | Negative | Positive | Unknown |

| Low levels | Unknown | Negative | Negative | |

Renal replacement therapies (RRTs)

In CKD cohorts, the prevalence in women is always lower than in men, and they have slower progression to ESRD [9]. Women with CKD have a higher cardiovascular risk than women without CKD [10].

Access to RRT in general is inequitable around the world [11]. The equality of access to RRT for women and girls is of concern because, in many societies, they are disadvantaged by discrimination rooted in sociocultural factors. There is a paucity of information about sex differences in RRT, but in multiple countries, men are reported to be more likely than women to receive dialysis [11, 12].

Women are more likely to donate kidneys for transplantation than to receive them, as reported from multiple countries; they are less likely to be registered on transplant waiting lists, and wait longer from dialysis initiation to listing. Mothers are more likely to be donors, as are female spouses [13, 14].

Present and future: what we do not know

Pregnancy, AKI, autoimmune diseases, CKD, dialysis and transplantation present specific challenges for women, for which many unanswered questions persist.

In high-income countries with increasing maternal age and assisted fertilization, there maybe an increase in PE, which may impact future generations if associated with adverse fetal outcomes. The increase in invitro fertilization techniques for those of advanced maternal age may lead to multiple pregnancies, which may predispose to PE, intrauterine growth restriction or both. Will this lead to an increase in CKD and CVD for women, and impact their offspring, in the future?

How should we define preconception risks of pregnancy with respect to current proteinuria cutoffs? Indications on when to start dialysis in pregnancy are not well established, nor is there a specificity of frequency and duration. In those with kidney transplants, given the changing expanded donor policies, higher age at transplantation and reduced fertility in older women, there may be changes in attitudes toward pregnancy with less than optimal kidney function [15]. How this will impact short- and long-term outcomes of mothers and their babies is not clear.

Teen pregnancies are very common in some parts of the world, and are often associated with low income and cultural levels. The impact of uneven legal rules for assisted fertilization and the lack of systematic assessment of kidney function require more research.

Despite elegant demonstrations for the role of sex hormones in vascular health and immunoregulation, the striking predominance in females of SLE, RA and SS remains unexplained relative to other systemic diseases such as anti-neutrophil cytoplasmic antibody (ANCA) vasculitis and hemolytic-uremic syndrome. The incidence of kidney involvement in SLE during pregnancy and similarities/differences in those with PE have not been well studied. The role of different medications and responses to medications for autoimmune diseases relative to sex has also not been well studied.

Attention to similarities between conditions, the importance of sex hormones in inflammation, immune modulation and vascular health may lead to important insights and clinical breakthroughs over time. If women are more likely to be living donors, at differential ages, does this impact both CVD risk and risk for ESKD: have we studied this well enough, in the current era, with modern diagnostic criteria for CKD and sophisticated tools to understand renal reserve? Are the additional exposures that women have after living donation compounded by hormonal changes on vasculature as they age? And are the risks of CKD and PE increased in the younger female kidney living donor?

In the context of specific therapies for the treatment or delay of CKD progression, do we know if there are sex differences in therapeutic responses to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor/angiotensin II receptor blocker? Should we look at dose finding/adjustments by sex? If vascular and immune biology is impacted by sex hormones, do we know the impact of various therapies by level or ratio of sex hormones? In low–middle income countries, how do changing economic and social cultures impact women’s health, and what is the nutritional impact on CKD of increasing predominance of obesity, diabetes and hypertension?

Summary

Women have unique risks for kidney diseases. Kidney diseases and issues related to access to care have a profound impact on both the current and next generations. Advocating for improved access to care for women is critical to maintain the health of families, communities and populations. There is a clear need for higher awareness, timely diagnosis and proper follow-up of CKD in pregnancy.

Focused studies on the unique contribution of sex hormones, or the interaction of sex hormones and other physiology, is important to improve our understanding of the progression of kidney diseases. Immunological conditions such as pregnancy (viewed as a state of tolerance to non-self) as well as SLE and other autoimmune and systemic conditions common in women, when better studied may also lead to breakthroughs in understanding and care paradigms.

World Kidney Day and the International Women’s Day 2018 are commemorated on the same day, an opportunity to highlight the importance of women’s health and particularly their kidney health. On its 13th anniversary, World Kidney Day promotes affordable and equitable access to health education, healthcare and prevention of kidney diseases for all women and girls in the world.

Acknowledgements

*Members of the World Kidney Day Steering Committee are: Philip Kam Tao Li, Guillermo Garcia-Garcia, Mohammed Benghanem-Gharbi, Kamyar Kalantar-Zadeh, Charles Kernahan, Latha Kumaraswami, Giorgina Barbara Piccoli, Gamal Saadi, Louise Fox, Elena Zakharova and Sharon Andreoli.

Authors’ contributions

All authors have contributed to the conception, preparation and editing of the manuscript.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared. Full disclosures are listed in the individual authors’ conflict of interest forms.

References

- 1. GBD 2015 Disease and Injury Incidence and Prevalence Collaborators. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016; 388: 1545–1602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Liu Y, Ma X, Zheng J. et al. Pregnancy outcomes in patients with acute kidney injury during pregnancy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2017; 17: 235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mol BWJ, Roberts CT, Thangaratinam S. et al. Pre-eclampsia. Lancet 2016; 387: 999–1011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Piccoli GB, Cabiddu G, Attini R. et al. Risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes in women with CKD. J Am Soc Nephrol 2015; 26: 2011–2022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Luyckx VA, Bertram JF, Brenner BM. et al. Effect of fetal and child health on kidney development and long-term risk of hypertension and kidney disease. Lancet 2013; 382: 273–283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ortona E, Pierdominici M, Maselli A. et al. Sex-based differences in autoimmune diseases. Ann Ist Super Sanita 2016; 52: 205–212 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Pierdominici M, Ortona E.. Estrogen impact on autoimmunity onset and progression: the paradigm of systemic lupus erythematosus. Int Trends Immun 2013; 1: 24–34 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Goemaere S, Ackerman C, Goethals K. et al. Onset of symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis in relation to age, sex and menopausal transition. J Rheumatol 1990; 17: 1620–1622 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Nitsch D, Grams M, Sang Y. et al. Associations of estimated glomerular filtration rate and albuminuria with mortality and renal failure by sex: a meta-analysis. BMJ 2013; 346: f324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Weiner DE, Tighiouart H, Elsayed EF. et al. The Framingham predictive instrument in chronic kidney disease. J Am Coll Cardiol 2007; 50: 217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Saran R, Robinson B, Abbott KC. et al. US Renal Data System 2016 Annual Data Report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis 2017; 69: A7–A8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Liyanage T, Ninomiya T, Jha V. et al. Worldwide access to treatment for end-stage kidney disease: a systematic review. Lancet 2015; 385: 1975–1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Jindal RM, Ryan JJ, Sajjad I. et al. Kidney transplantation and gender disparity. Am J Nephrol 2005; 25: 474–483 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Salter ML, McAdams-Demarco MA, Law A. et al. Age and sex disparities in discussions about kidney transplantation in adults undergoing dialysis. J Am Geriatr Soc 2014; 62: 843–849 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Webster P, Lightstone L, McKay DB. et al. Pregnancy in chronic kidney disease and kidney transplantation. Kidney Int 2017; 91: 1047–1056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]