“Illness and death every day anger us. Not because there are people who get sick or because there are people who die.

We are angry because many illnesses and deaths have their roots in the economic and social policies that are imposed on us.”

(A voice from Central America) Global Health Watch 2 / People’s Health Movement

Executive Summary

Either in the World or in Turkey, the right of living healthy must be considered before economic concerns and interests in all decisions that will influence the health of the individual and population. However, marketing arrangement of tobacco products are currently under the custody of tobacco oligopoly. Custody of the existing oligopoly is quite effective on population due both to public relations and hidden/explicit campaigns. Therefore, new tactics and strategies that directly target tobacco industry are needed to know.

In order to reduce tobacco use in the World and in Turkey, strategies for reducing supply of tobacco products are required in addition to the precautions implemented in Turkey to reduce demand. Therefore, action plans towards supply-reduction must predominantly take place in the National Tobacco Control Program (NTCP) that will be shaped after 2013 in Turkey.

Tobacco industry’s money-making way of work and new tactics developed particularly for sales and marketing make the control almost impossible. Therefore, delivery of tobacco products to consumers must be provided, instead of tobacco industry, by non-profit organizations that completely adopt tobacco control measures. Thereby, manipulative tactics of the tobacco industry particularly at sales and marketing can be totally prevented and it will be easy to implement effective tobacco control policies that can reduce supply, with “plain/simple packaging” being in the first place.

Any level of negotiation and collaboration at any step between the political power and the tobacco industry is acceptable because of the likely destruction for individual and public health. Within this frame, activities of the political mechanisms must be shaped in accordance with the spirit of Framework Convention on Tobacco Control (FCTC) No. 5.3.

Social responsibility projects that tobacco companies arrange or support to regain their reduced social legitimacy and donations and/or financial aids they provide to the public and/or civilian organizations must be totally rejected and foundations and institutions associated with tobacco industry must be announced to the public.1

In order to prevent or deactivate applicability of tobacco control provisions, tobacco industry makes interventions that take the cultural and sociological authenticity of public into account. Therefore, with regard to tobacco use and control, similar multidimensional and stratified scientific data must be formed to inactivate these multidimensional interventions of tobacco industry. Within this frame, obtaining more support for tobacco control in the upcoming period particularly from the fields of psychodynamics, neuroradiology, neuroeconomy, neuromarketing, anthropology and sociology is vital.

In the campaign against the epidemic caused by tobacco industry, real-life stories, that unveil negative emotions of the population and individual, such as anger, irritation and regret and that respond to the questions “why” and “how” must be presented to the public as advertisements for tobacco control. Within this context, before the advertisement campaigns, a target group-oriented evaluation to test the messages that are planned to be given and, likewise, assessment of its efficacy over the course of campaign is mandatory.

Both pregraduate and postgraduate education programs of medical faculties in Turkey should be redesigned in the way to train physicians, who would translate effective tobacco control principles into behaviour. Therefore, education program prepared by the Turkish Thoracic Society (TTS) should take place in the National Tobacco Control Program that will be newly formed in Turkey. Likewise, particularly the fact that health care workers should refrain tobacco use should be specifically highlighted in the National Tobacco Control Program of the upcoming period. Within this frame, especially occupational organizations of paramedical health care workers must take more responsibility for the solution of this problem in terms of tobacco control and transition of their members to a tobacco-free life.

Although unseating the Tobacco and Alcohol Market Regulatory Authority (TAPDK) by the political power is considered as “correct” within the context of principally not defining any economic field out of political mechanism, involving political will, which is the basic part of tobacco control, in this process with all its institutions and rules, and the existence of “demos”, the fact that the authorization of the Tobacco and Alcohol Market Regulatory Authority has been transferred to the ministries free from the tobacco control provisions, is a great handicap in terms of tobacco control in Turkey. Within this context, in the event that the activity field of supreme board could not be filled properly by the ministries, it must be foreseen that the efficacy of tobacco industry would be enhanced in the upcoming period.

In Turkey, the basic organs of tobacco control campaigns are the Provincial Tobacco Control Committees. However, the functions of these committees have been left predominantly to the initiative of non-governmental organizations, which voluntarily make contributions with a great motivation, and to the Ministry of Health and its field organizations. In fact, tobacco control struggle is a process that can succeed with the contribution of different ministries, with the Ministry of Interior being in the first place, as much as the Ministry of Health. Therefore, Provincial Tobacco Control Committees should be reactivated, and disruptions caused by public organizations other than Ministry of Health should be eliminated.

It is known that women and young population are the main targets of tobacco industry both in Turkey and in the World. Because, young population provides an “important opportunity” in terms of a “sustainable market” for tobacco industry. On the other hand, considering the gradually narrowing “tobacco market” in the “developed countries”, it is observed that dynamics of the young population in “developing countries” gain more importance for tobacco industry. Therefore, tobacco control implementations are mandatory to be specified focusing on women and young population. Likewise, it is inevitable for tobacco control implementations to become the basic part of occupational health and safety implementations.

Covering the drugs used in smoking cessation treatment by governmental reimbursement is a basic health right for tobacco product users. On the other hand, cost-effectiveness of these drugs has been proven in scientific researches. Therefore, such drugs must obtain the guarantee of reimbursement by the Social Security Institution. On the other hand, the gradually spreading use of non-evidence-based smoking cessation methods each day must be finalized with effective control activities of the authority as required by the basic principle “primum non nocere”.

Critical Determinations and Recommendations

The aim of tobacco control is to control the ambition of tobacco industry to make money, which causes death in the field of tobacco. Indeed, the most important deficiency in tobacco control policies put in practice in Turkey is the fact that this situation has not been targeted primarily and predominantly.

With regard to tobacco control, distribution of tobacco products to the final points of sales must be immediately taken from the responsibility of tobacco industry and performed by the government and, in the mid-term, tobacco production is necessary to be taken from multinational companies and transferred to the public authority.

Within the frame of the Legislation on the Prevention and Control of Harms of Tobacco Products No. 4207, some implementations brought into agenda within the scope of the definition of “tobacco products” are quite problematic. Because, in daily practice, many products are being put into use under the name of “herbal” particularly via water pipe (hookah). On the other hand, there is no organization in which the laboratory analyses of these products that are put into use via “water pipe” could be performed. That is to say, the content of these products is unknown. Therefore, it must be immediately recorded that all products put into market under the name of “herbal” or under other names are “prohibited” and are not subject to the provisions of the Legislation on the Prevention and Control of the Harms of Tobacco Products No. 4207, but contrarily it is illegal to use and put them on market. Otherwise, all interventions that expand the definition of “tobacco product” would justify and legitimize the use and marketing of products, which are still illegal and have unknown content.

The Turkish practice is in the way that “prohibitions” defined in the scope of Legislation on the Prevention and Control of the Harms of Tobacco Products No. 4207 predominantly remain in the Law and violations become “rule” in almost everywhere, whereas obedience becomes an “exception”.2

For the solutions in the field of tobacco control, governmental organs other than the Ministry of Health must also be ensured that they are sensitive as much as the Ministry of Health at the least.

The final solution of the problems encountered in the field of tobacco control is to establish a “Tobacco Control Institution”. Because maintenance of TAPDK as it stands is insufficient for the solution of problems due both to its unequipped infrastructure and attempt to “organize” but not “control” the tobacco sector.

Related provisions of the Legislation on the Prevention and Control of the Harms of Tobacco Products No. 4207 are particularly inadequate in terms of the package of tobacco products. It must be immediately switched to “Plain/simple package” implementation, which has been put in practice in Australia.

Turkish practice reveals that “public service ad” is not been implemented as is indicated by the legislation. Therefore, implementation of “public service ad” must be performed aiming only at tobacco control as in the Legislation on the Prevention and Control of the Harms of Tobacco Products No. 4207.

From now on, it is mandatory to develop supply-reduction interventions rather than demand-reduction interventions in Turkey. Moreover, both regulation and practice against “brand stretching” policies put in practice by tobacco industry to overcome legal provisions and against new tobacco products recently put on markets (water pipe, smokeless tobacco products, electronic cigarettes etc.) must be made competent.

Health system in Turkey must promptly be brought into conformity with addiction treatment and integrated into primary health care services, pharmacological therapy must be cheap and available and, more importantly, use of non-evidence-based treatment modalities that are claimed to create miraculous solutions, must be prevented.

The most important implementation that reduces the accessibility of young population to tobacco products is keeping the price of cigarettes high. Therefore, the price of cigarettes in Turkey must be increased to the levels in Australia, Norway and the United Kingdom.

Currently, it is not clear how the “protection of development and implementation of public health policies for tobacco control from tobacco industry and other interest groups”, which has been defined in the Framework Convention on Tobacco Control of the World Health Organization (WHO), would be provided. However, this provision is one of the mandatory provisions of FCTC and a regulation defining how this would be implemented must be published in the upcoming period.

Tobacco control policies determined in Turkey must be combined with specific protective precautions for poor people and for the groups that are exposed to social exclusion.

Tobacco epidemic and its Impacts

Tobacco addiction is a public health problem that killed a hundred million people in the 20th century and is going to kill one billion people in the 21st century [1]. Indeed, tobacco use is the risk factor in 6 of 8 diseases that are the leading causes of death in the world [1]. On the other hand, two leading causes of death are hunger and tobacco use worldwide. Because tobacco use leads to many fatal health problems either directly or due to passive exposure to smoke (Table 1) [1].

Table 1.

Smoking-related diseases

| Smoking-related diseases | Second-hand smoke-related diseases | ||

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Cancers | Chronic diseases | Children | Adults |

| Larynx | Stroke (paralysis) | Brain tumour* | Stroke (Paralysis)* |

| Oropharynx | Blindness | Middle ear disease | Nasal irritation |

| Oesophagus | Cataract | Lymphoma* | Nasal Sinus Cancer* |

| Lung | Periodontitis | Pulmonary function disorder | Breast cancer |

| Acute myeloid leukaemia | Aortic Aneurism | Asthma* | Coronary heart disease |

| Stomach | Coronary Heart Disease | Lower respiratory tract disease | Lung cancer |

| Pancreas | Pneumonia | Sudden infant death syndrome | Arteriosclerosis* |

| Kidney and Ureter | Atherosclerotic peripheral vascular disease | Leukaemia* | COPD / Asthma* |

| Colon | COPD / Asthma | Reproductive impacts | |

| Cervix | Hip fracture | ||

| Urinary bladder | Reproductive impacts | ||

Causal evidence level is “challenging

It is known that tobacco smoke carries disease and death also to the individuals other than those using tobacco. However, sometimes these effects of second-hand tobacco smoke on health are disregarded. In fact, data indicate that worldwide 40% of children, 35% of non-smoker women and 33% of non-smoker men are affected by second-hand tobacco smoke [2]. Moreover, second-hand tobacco smoke leads to death due to ischemic heart disease, lower respiratory tract disease, asthma, and lung cancer [2]. Unfortunately, worldwide 47% of female deaths, 28% of paediatric deaths and 26% of male deaths result from second-hand tobacco smoke [2]. Unless this epidemic is not controlled in the upcoming years, it is estimated that 175 million people in most of the developing countries will die due to a tobacco-related disease until 2030 [1].

In summary, as was expressed in the National Tobacco Control Program Circular, today there are 1.1 billion smokers in the world and this outbreak causes death of 4.5 million people each year. In Turkey, there are 17 million smokers as of the date of the Circular and such a high smoking rate leads to the death of 200–250 people in a day and of 70–100 000 people in a year [3].

It is necessary to know the “Enemy” and its Policies

It should be kept in mind that tobacco is not the reason of this problem that kills worldwide 12,000 people each day. Because tobacco plant does not kill humans in the field. The plant itself does not cause health problem in the place where it grows.

On the other hand, the American Indians, who first used tobacco, are also not the cause of these deaths. Because Indians inhaled tobacco only during religious rituals.

The small manufacturer that sells Oriental Tobacco in the open-air market, particularly in the eastern Turkey is either not the cause of these deaths. Because a few kilograms of tobacco that he could sell do not cause such a worldwide epidemic. Moreover, this small manufacturer, who could sell a few kilograms of tobacco in an open-air-market and could just make ends meet does not have the power to effect either 1.1 billion people in the world or the governments.

However, tobacco industry, which buys the tobacco that the Indians use, makes this tobacco a commodity in the factories, eliminates all barriers between itself and this commodity and runs after earnings and interest all over the world is the cause of these deaths. Therefore, the aim of “tobacco control” is to bring such ambition to make money that causes deaths in the field of tobacco under control. Because, as WHO stated, “There is a way of contamination in all contagious diseases and a mediator that leads to the spread of disease and deaths. The mediator in tobacco outbreak is not a virus, bacteria or another microorganism–the mediator is the industry and its working strategy.” [1]. In any case, the most important deficiency of tobacco control policies put in practice in Turkey is the fact that this situation has not been primarily or predominantly targeted. Therefore, we must direct our anger not to the tobacco users, as was frequently done in Turkey, but contrarily to the tobacco industry and the institutions and individuals that work in coordination with the industry. Because, it should not be forgotten that the aim of tobacco control is to bring the ambition of tobacco industry to make money under control.

It is necessary to be closely acquainted with this industry and its policies, which denies following any ethical, moral or legal provision to improve and protect individual and public health but is only motivated to make money. Because constraints and enforcements that would control the industry could be developed if only its policies are known.

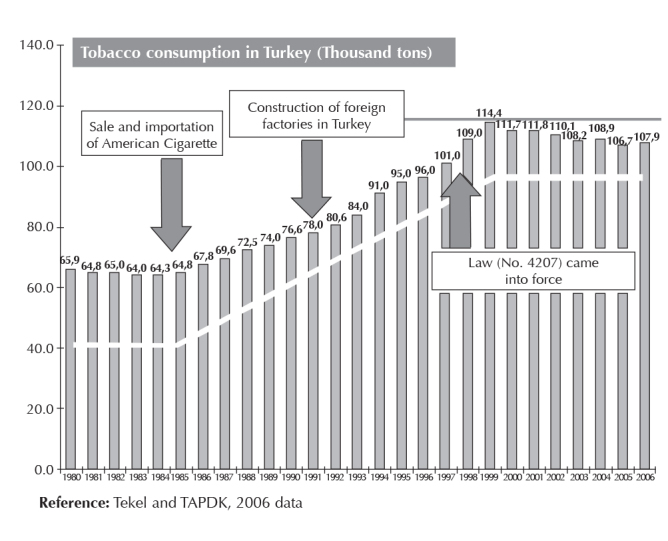

Taking a cigarette-production structure from government ownership and leaving it to the tobacco industry, which has no aim other than making money, is a disadvantageous condition in a country in terms of tobacco control policy of that country. The most concrete evidence of this situation in Turkey is between 1985 and 1995, when multinational companies started to construct factories nationwide. Reviewing the data, it can be seen that the cost of liberalization policy actualized by Turgut Özal in that period after military coup is 80% increase in tobacco consumption in Turkey (Figure 1) [4].

Figure 1.

Tobacco use in Turkey (thousand tonnes)

On the other hand, evaluating the other countries other than Turkey within the same frame, it is observed that tobacco consumption has been increased, age of onset for smoking has been decreased and, moreover, an additional demand has arisen among smokers in the countries in which tobacco production has been denationalized and left to tobacco industry due both to cheapened tobacco products and widened and activated distribution network and to the effective and aggressive lobby activities conducted against tobacco control policies by tobacco companies [5]. However, unfortunately, despite these unfavourable outcomes for individual and public health, it is conspicuous that International Monetary Fund (IMF) continues to put pressure in terms of denationalizing the governmental tobacco production units [5].

In fact, unfortunately, tobacco sector has experienced a similar process in Turkey and the sector has first been liberalized and then the Turkish state owned tobacco and alcoholic beverages company (TEKEL) has been allowed to be denationalized as the result of pressure applied by the IMF and the World Bank on the Ministry of Finance and Ministry of Industry and Trade, as well as on Treasury and State Planning Organization. Privatization of TEKEL has made it quite difficult to control the ambition of Tobacco industry to make money by selling death in the field of tobacco. However, the devastation caused by privatization of TEKEL is not limited to this. Because, privatization of TEKEL means that the farmers in Turkey that earn money by cultivating tobacco and the workers in TEKEL factories are going to become unemployed. Indeed, the majority of tobacco producers left tobacco cultivation due to increased cost, the quota put to increase the interest of transnational tobacco industry, and decreased prices [6].

As a consequence of this policy carried out in Turkey and in the World, decrease in the profit level of transnational tobacco industry due to decreased tobacco consumption in the developed countries has been prevented at the expense of impoverishing the people that earn money by cultivating tobacco in the “developing” and “underdeveloped” countries. Indeed, by 2000s, one of the tobacco companies has reached to the point of marketing 70% of its products to Africa, Asia, Eastern Europe and Latin America [7]. This proves with no doubt that the policy implemented has succeeded in favour of transnational tobacco industry.

For Turkey, in 2008, market share of two tobacco companies has exceeded 80% in Turkey [8]. In fact, in his speech made during handover ceremony, Johan Vandermuelen, the Turkey general manager of the tobacco company that bought TEKEL in 2008, highlighted the importance of “growth opportunities” in Turkey with the words “This provides an important basis for growth opportunities of BAT in Turkey. Such an investment in a period with liquidity crisis in markets is a significant indicator of our belief in Turkey’s future and our stability in terms of being a long-term investor.” [9]. No doubt, the meaning of “growth opportunities” for a cigarette monopoly in terms of medicine and health is the disability or death of more people. On the other hand, in the same ceremony, Tuna Turagay, Director of Corporate Relations of this company in Turkey, pointed out this approaching danger by saying “As BAT, we consider Turkey, which is the 8th great tobacco market of the world, extremely important in terms of our global activities. We have increased our market share in 6 years. With this union, we will be the 2nd greatest company in the sector of fast moving consumer goods next year” [9]. Therefore, for tobacco control, distribution of tobacco products to the final points of sales must immediately be taken from tobacco industry and performed by the government; in the mid-term, tobacco production is necessary to be taken from multinational companies and switched to the public authority.

Current status

Tobacco control studies carried out in Turkey have been widely brought into conformity with the World Health Organization Framework Convention on Tobacco Control by means of the “Legislation on the Prevention and Control of Harms of Tobacco Products No. 4207” and 2008–2012 tobacco control national activity plan has become valid.

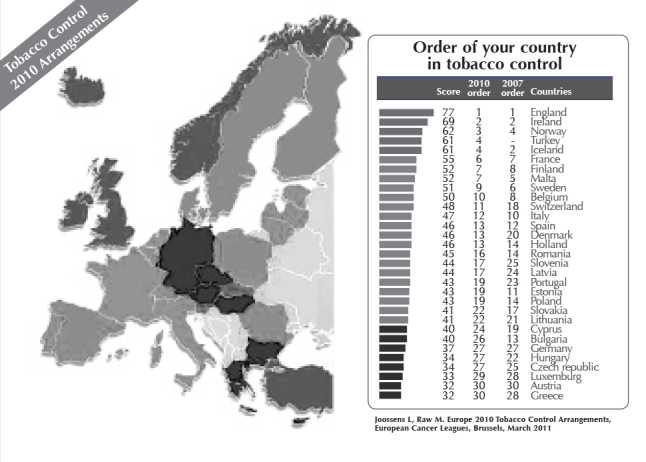

Because of the fact that relevant institutions and organizations have relatively duly undertaken the liabilities under the legislation within the period of 2008–2011, 12% decrease has been observed in tobacco consumption in Turkey in this period and, for the first time within the last 15 years, the number of cigarettes consumed was less than 100 billion (92 billion). Again, with favourable efforts made in this period, Turkey has risen up to number 4 in European tobacco control ranking and this success has been awarded by many international organizations, World Health Organization being in the first place.

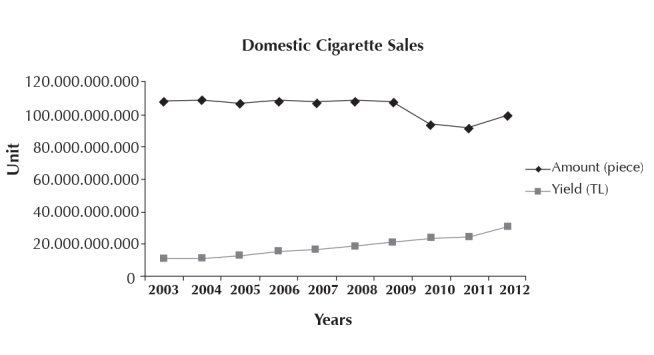

However, the period of 2011–2012 attracts attention as being a period in which this favourable process has suffered from erosion. Because, consumption of tobacco products in closed areas has remarkably increased in this period. In fact, its reflection is observed as increase in cigarette sales. Indeed, Turkey-wide 8 billion more cigarettes have been consumed within the period of 2011–2012 as compared to the previous year and cigarette sales has risen up to 100 billion again (Figure 2) [10].3

Figure 2.

Cigarette sales in Turkey

In addition, although it has been definitely banned in the Legislation on the Prevention and Control of Harms of Tobacco Products No. 4207, advertisement, sponsorship and promotion activities of tobacco industry increasingly continued in the period of 2011–2012. Tobacco industry performed sponsorship and promotion activities either indirectly under the name of “social responsibility projects” or via direct activities under various names.

On the other hand, FCTC Article No. 5.3, which has been accepted by Turkey, adjudicates that all people working in public institutions must be precluded from contact with tobacco industry and compulsorily contacts that would be made for legal justifications are necessary to be transparent to public opinion. However, despite existing mandatory provision, public authority in Turkey contacts with tobacco industry with all its organs from the ministries to the bureaucrats and in all fields and platforms far away from transparency.

From the view of medicine, consumption of tobacco products is now considered as a treatable “disease”. Therefore, same as in other diseases, it should be treated by a physician using evidence-based scientific methods. Within this context, the number of smoking cessation outpatient clinics, which are affiliated to the Ministry of Health, has increased up to approximately 400 in the period of 2008–2012. However, in Turkey of 2012, non-evidence-based methods have been promoted in the media and virtual media, but contrarily; effective scientific methods used for cigarette cessation treatment remain uncovered by the Social Security Institution.

Legislation on the Prevention and Control of Harms of Tobacco Products No. 4207

The first legislative proposal that aimed to regulate tobacco consumption in Turkey within the frame of legal regulation provisions was proposed on 7 March 1986 by Reşit Ülker, Istanbul representative of the Republican People’s Party. This proposal entitled “Legislative Proposal Related to the Addition of Certain Articles to the General Hygiene Law Date 6 May 1930 and No. 1593 for the Prevention of Cigarette Harms” has become obsolete since it could not have been brought to a conclusion within the related legislation year [11]. The second legislative proposal on the subject was proposed on 10 May 1989 by Cüneyt Canver, Adana representative of Social Democratic Populist Party. Prohibitions on advertisement have been brought into agenda with this proposal entitled “Legislative Proposal on the Amendment of Tobacco and Tobacco Monopoly Law No. 1177” [11]. The third legislative proposal on tobacco and tobacco products was proposed by Bülent Akarcalı, Istanbul representative of the Motherland Party. This legislative proposal dated 29 May 1989 was entitled as “Legislative Proposal on the Protection from the Harmful Habits of Cigarette, Tobacco and Tobacco Products” [11].

Landmark for the regulation of tobacco and tobacco products in Turkey within legal provisions is the “Legislation on the Prevention of Harms of Tobacco products No. 4207”, which was accepted on 7 November 1996 and published in the Official Journal Dated 26 November 1996 No. 22829. Because this Law prohibited cigarette use in public transport vehicles and in the majority of closed areas, in addition to putting obligations for educational broadcast on this subject and placing warnings on cigarette packages. Likewise, with this Law, advertisements for tobacco products and cigarette sales to children less than 18 years of age were included within the scope of prohibition. Although there are legal gaps particularly in the implementation of punitive articles of this Law, public transport vehicles in particular have been made free from smoke by means of this Law and significant enhancement have been achieved in social awareness.

On the other hand, expansion of the Law No. 4207 and elimination of certain malfunctions in practice have become obligatory along with the approval of FCTC in 2004 by the Grand National Assembly of Turkey (TBMM) and establishment of the National Tobacco Control Program. Therefore, an amendment proposal, which expands the scope of Law No. 4207 accepted in 1996 in the way to be consonant to FCTC provisions and particularly making the implementation of punitive provisions competent, was prepared by Cevdet Erdöl, Trabzon representative of the Justice and Development Party and the head of Health Commission. This amendment proposal, which was supported also by Recep Akdağ, the Minister of Health, and Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, the Prime Minister of the Justice and Development Party Government, became Law on 3 January 2008 with positive votes from all political parties in the TBMM and entered into force after being published in the Official Journal dated 19 January 2008 [12].

The aim of the Law entitled as the “Legislation on the Prevention of Harms of Tobacco Products” is to prevent the harms of tobacco products and to enable tobacco control. As is known, to prevent the initiation of tobacco product use, to protect the subjects from second-hand cigarette smoke, to help those who want to quit, and to reduce harm for smokers are the components of tobacco control. Therefore, the provisions of the Law were established considering these components. On the other hand, the aforementioned Law did not simplify the problem to cigarette-related harms by expressing that the term “tobacco product” comprises all substances produced entirely or partially from tobacco leaves as the raw material, to be used for smoking, sucking, chewing or snuffing.

However, the definition “any kind of water pipe and cigarettes that does not contain tobacco but mimic tobacco products is considered as tobacco product” which is within the scope of the “Legislation on the amendment of certain Laws and statutory decree No.375” that was accepted on 24 May 2013 and published in the Official Journal on 11 June 2013 is quite problematic. Because, in daily life, many products are brought into use under the name of “herbal”, in particular, via water pipe. However, laboratory analysis of these products that are particularly brought into use via “water pipe” is not available in Turkey. That is to say, the contents of these products are unknown. Therefore, it must immediately be recorded that all of these products put into market under the name of “herbal” or under other names are “prohibited” and are not subject to the provisions of the Legislation on the Prevention and Control of Harms of Tobacco Products No. 4207 but, contrarily, it is illegal to use and put them on market. Otherwise, any effort that expands the definition of “tobacco product” would justify and legitimize the use and sales of these products with unknown contents.

The World Health Organization recommends the member countries prevention of consuming tobacco products in closed areas and thus making these places free from smoke as an effective method to protect the individuals from exposure to second-hand smoke [1]. In conformity with this recommendation, “Legislation on the Prevention and Control of Harms of Tobacco Products” completely banns tobacco consumption in;

Closed areas of public places;

Closed areas of buildings used for any kind of education, health, manufacturing, trading, social, cultural, sports, entertainment and similar purposes, excluding residential buildings, that are accessible for more than one people and belong to private persons liable to law;

Public transport vehicles used on motorways, including taxi services, railroads, maritime line and airline;4

Closed and open areas of preschool, primary and secondary education institutions including private education and training institutions, and cultural and social service buildings

Business places that give entertainment service such as restaurants and café, cafeteria and beer house of private persons that are liable to law.

The Law adjudicates that tobacco products cannot be used in places where any kind of sports, culture, art and entertainment actions are performed outdoors, as well as in the stands or tribunes of these places, but areas for consuming tobacco products can be formed in these facilities. Likewise, it states that rooms in which tobacco consumption is free for customers that consume tobacco products can be allocated in facilities where accommodation service is given. Moreover, it has been adjudicated that areas for tobacco consumption can be created in nursing and rehabilitation centres for elderly, mental and neurological diseases hospitals, prisons and on the decks of passenger liners. But, the Law stipulates as an obligatory that these closed areas formed for tobacco consumption must be isolated in the way to prevent the passage of odour and smoke, equipped with air-conditioners, and that people younger than 18 years old are banned to enter such places.

However, Turkish practice reveals that these “prohibitions” only remain in the Law and violations become “rules” in almost everywhere, whereas units that obey the law turn into an “exception”. The basic reason for this situation is the fact that almost none of the governmental structures - particularly the Ministry of Interior-except for the Ministry of Health, meet the legal liabilities that arise from the laws and circulars. The weak legal basis of the Provincial Tobacco Control Committees, their being left to the initiatives of the administrative chief of the province, and absence of effective and truthful support of law enforcement agencies in the province for the aforementioned committee has led “smokeless air field” applications to be left on paper. The solution of this problem is enhancing the sensitivity of the other units of public authority than the Ministry of Health as much as that of the Ministry of Health. On the other hand, the fact that TAPDK would be unseated in the upcoming period without duly handing over its missions would make the restricted implementation of the requirements of Legislation on the Prevention and Control of Harms of Tobacco Products No. 4207 more impossible. In fact, the problem can be solved by the establishment of the “Tobacco Control Committee” by the legislator. Because continuation of TAPDK as it stands is not adequate for the solution of problems both because of its insufficient infrastructure and efforts made not for “controlling” but for “regulating” tobacco industry. Indeed, it is obvious that, over the course of its duty TAPDK considered some regulations on tobacco control with hesitation and, moreover, could not develop effective and scientific provisions on the regulations of points of sales and on additives. The main reason for this is the fact that the rationale for establishing TAPDK contended itself with “regulating” rather than “control” of tobacco use.

In the MPOWER strategy, the World Health Organization stated that prohibition of advertisement, promotion and sponsorship for tobacco products is an effective policy for tobacco control [1]. The “Legislation on the Prevention of Harms of Tobacco Products”, therefore, adjudicates that names and logo of tobacco companies or the brand and sign of their products or the symbols that would remind these are not allowed to be used as a dress, jewellery or accessory. The Law also punishes the individuals that behave against the provision by a pecuniary penalty in accordance with the article No. 39 of Misdemeanour Law similar to the people that violate the legal provisions in the areas in which tobacco consumption is banned, and transfers the property that violate the law to the public ownership. Moreover, the aforementioned law, just as its 1996 version, orders that advertisement and promotion using the name, brand or signs of tobacco products or producer companies are not allowed to be performed; campaigns that promote or encourage the use of products are not allowed to be organized; companies that produce or market tobacco products are not allowed to sponsor any activity using their names or logo, or the brand or signs of their products; the vehicles of the companies in tobacco sector are not allowed to carry any signs that would allow the recognition of the brands of their products, and the companies are not allowed to deliver tobacco products to the distributors or consumers as an incentive, gift, sample, promotion, free of charge or aid and are not allowed to advertise using the names, logo or symbols of tobacco products. The Law states that the Tobacco and Alcohol Market Regulatory Authority will execute a penal sanction to those that behave against these provisions and the ownership of the properties that are delivered free of charge or as an aid will be transferred to the public ownership.

In today’s world, the effect of mass media, which is considered as the fourth power, on our lives is gradually increasing each day. No doubt, media has an important role in both tobacco consumption and control. Since the “Legislation on the Prevention of Harms of Tobacco Products” is aware of the possible vital role of media on tobacco consumption, it does not allow either the use or demonstration of tobacco products in television programs, movies, serials, music videos, advertisements and promotion videos. The law states that the organizations that behave against this provision and violate the law via visual broadcast will be punished by a pecuniary penalty by the Radio and Television Supreme Council.

Under the topic of other preventive precautions, “Legislation on the Prevention of Harms of Tobacco Products” adjudicates that;

Tobacco products are not allowed to be sold in places where health, education and training, culture and sports services are provided;

Tobacco products are not allowed to be sold to people under the age of 18 years;

Individuals under the age of 18 years are not allowed to be employed in tobacco companies, marketing and sales of tobacco;

Tobacco products are not allowed to be sold in the form of small packages or one by one by means of opening the package;

Tobacco products are not allowed to be exposed for sale in the way that those under the age of 18 years can easily reach or can be seen from the outside of the unit;

Any kind of chewing gum, candy, snacks, toy, dressing, jewellery and similar products are not allowed to be produced, delivered or sold in the way similar to tobacco products or could remind their brands.

But, Turkish practice reveals that almost all of the abovementioned regulations and “prohibitions” remain in the law, violations become “rules” in almost everywhere, and the units that obey the law turn into “exceptions”. The main reason for this situation –as was mentioned before- is the fact that almost none of the governmental structures other than the Ministry of Health-especially the Ministry of Interior-has met the liabilities specified for them with laws and circulars. The way to solve this problem is enabling the units of the public authority other than the Ministry of Health to be as sensitive as the Ministry of Health and to establish a “Tobacco Control Institution”.

For tobacco control, the “Legislation on the Prevention of Harms of Tobacco Products” adjudicates that;

In the areas where smoking is banned, warnings that emphasize the punitive consequences of not obeying this legal regulation must be posted in places observable by everyone.

In areas allocated for tobacco product consumption, health warnings that explain the danger of using tobacco products must be posted in places observable by everyone,

In areas where it is free to sell tobacco products, the phrase “Legal Warning: cigarette and other tobacco products cannot be sold to those under the age of 18 years; legal action will be taken against the sellers” must be written in accordance with the standards specified by the Tobacco and Alcohol Market Regulatory Authority and should be posted in a place observable and readable by everyone in the areas where it is free to sell tobacco products.

On the other hand, for tobacco control the “Legislation on the Prevention of Harms of Tobacco Products” states that;

It is necessary to place warnings and messages in Turkish, within a special frame, on the packages of tobacco products either produced in Turkey or imported;

It is also necessary to place these warnings, in a similar way, on the boxes of tobacco products that contain more than one packages;

Warning messages can also be in the form of pictures, figures or graphics as well and tobacco products that have no warning messages will not be imported or put for sale;

It is not allowed to give wrong or inadequate information especially about the properties of these products, their effects on health, dangers or emissions and it is not allowed to use deceptive definition, brand, colour, figure or sign on the packages and labels of tobacco products. The law states that those who behave against the provisions described in this section will be punished by an administrative pecuniary penalty by the Tobacco and Alcohol Market Regulatory Authority and that the ownership of tobacco products that violate the regulation will be transferred to the public ownership.

Within this context, the related provisions of the Legislation on the Prevention and Control of Harms of Tobacco Products No. 4207 are inadequate especially regarding the package of the tobacco product. Immediately, “Plain/Simple Package” implementation should be put into action as is in Australia [13].

The “Legislation on the Prevention and Control of Harms of Tobacco Products” also equips the Radio and Television Supreme Council with various responsibilities and authority. Within this frame, as required by the provisions of the Law; the Turkish Radio and Television Corporation, private television corporations and radios are obliged to broadcast warning and educating programs for at least ninety minutes in a month, which will be prepared or made prepared by the Ministry of Health, Ministry of National Education, Radio and Television Supreme Council, Tobacco and Alcohol Market Regulatory Authority, scientific organizations and non-governmental organizations, on the harms of tobacco products and other habits deleterious to health. This provision of the Legislation on the Prevention and Control of Harms of Tobacco Products No. 4207 adjudicates the implementation of “Public service ad”, which is of critical importance for Turkey.

However, Turkish practice reveals that “Public service ad” is not used in the way that the Law indicates. Therefore, the implementation of “Public service ad” must be performed focusing only on tobacco control implementation as is defined in the Legislation on the Prevention and Control of Harms of Tobacco Products No. 4207.

For the final word…

Disregarding serious problems in practice, tobacco control struggle that has been insistently, patiently and persistently carried on since early 90s has reached to a quite competent level “in terms of legal regulations” (Figure 3) [14].

Figure 3.

Tobacco control 2010 ranking

However, as we expressed in this paper, despite all these improvements, the struggle for tobacco control in Turkey has dimensions to be developed, implementation and monitoring of the legal provisions being the leading.

On the other hand, it is mandatory to develop interventions focusing on supply-reduction instead of demand-reduction in tobacco control in Turkey. Moreover, it is necessary to make the regulation and particularly the implementation and enforcements competent against “brand stretching” policy that tobacco industry put into use to overcome legal provisions and against new tobacco products put on the market (water pipe, smokeless tobacco products, electronic cigarettes, etc.).

According to the data from the Global Adult Tobacco Survey, 44.9% of smokers in Turkey tried to quit using tobacco within the last year-this prevalence was 40.8% in 2008 [15]. Likewise, 41.8% of males tried to quit using tobacco within the last year-this prevalence was 40.5% in 2008 [15]. Of the current tobacco users, 35.4% are planning to quit smoking within the next 12 months-this prevalence was 27.8% in 2008 [15]. Data indicate that Turkey is ready to quit smoking. However, the medications used for cigarette cessation are unfortunately left out of reimbursement. In fact, as stated by the World Health Organization; health system in Turkey should immediately be brought into conformity with addiction treatment and integrated into primary health care services, pharmacological therapy must be cheap and available, and more importantly, the use of non-evidence-based treatment modalities, which are claimed to provide miracle solutions, must be prevented [1].

Despite the tax burden-with a total tax percentage of 80.3% on tobacco products by the year 2011 [16] - the sales price of cigarettes is low in Turkey. However, the selling price of a pack of cigarettes is about 7.62 Euro in Australia, 7.57 in Norway and 7.18 in the United Kingdom. Although it is claimed that Turkey is not equal to Australia, Norway and United Kingdom in terms of purchasing power, considering the higher prices of natural gas, meat and gasoline as compared to the above-mentioned countries, the sales price of cigarettes, which is not among the basic consumer goods as natural gas, meat or gasoline, should be increased as high as in Australia, Norway and United Kingdom.

Moreover, it is not clear how to enable “the development of public health policies for tobacco control and the protection of implementations from commercial interests of tobacco industry and from other interest group” mentioned also in the WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. In fact, this provision is one of the critical mandatory provisions of FCTC and a circular defining the implementation of this provision must be published in the upcoming period.

Finally, researches on tobacco use revealed that those with low occupational status, living in a rented house, not owning a car, not employed, living in a crowded house, in prisons, or immigrants and homeless people use tobacco significantly more frequently [17]. Indeed, impoverished people and pariahs have lower awareness about the harms of tobacco. They are unprotected against the policies of tobacco industry. They have difficulties in stress management. They maintain their lives with difficulties brought along with coping with financial deficiency and, unfortunately, they define tobacco use as the only “award” in their bad lives [18].

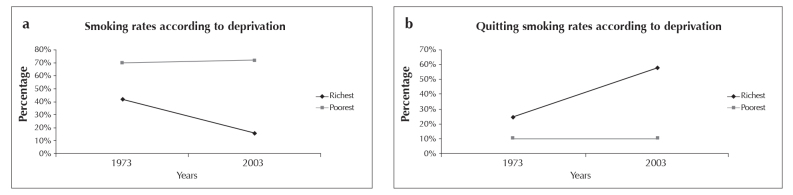

As can be seen, all these data indicate that tobacco epidemic, as other health problems, is determined by socioeconomic factors. Indeed, it is known that unemployment increases the frequency of tobacco use by approximately three times [19]. Within this frame, the close relation between tobacco use and socioeconomic factors highlights that reducing poverty, social policy, and equal distribution of wealth among whole population must be the indispensable parts of tobacco control. In fact, another finding that verifies this determination is the fact that increased prices of tobacco products has not always been a policy that lowers tobacco use among unemployed and impoverished people as was expected [20]. Similarly, in the United Kingdom, which maintains a “successful” campaign in the field of tobacco control, no decrease in the prevalence of smoking and quitting smoking among impoverished people was observed within the 30 years between 1973 and 2003 contrarily to wealthy people (Figures 4a, b) [17].

Figure 4 a, b.

Socio-economic status and prevalence of cigarette smoking

In addition, in another recent study, it was demonstrated that starting smoking is negatively correlated with education in both males and females, whereas continuing smoking is negatively correlated with only income in males, and with both income and education in females [21]. On the other hand, in a study from Turkey, it was demonstrated that “absence of a money-making job” decreases the success rate of quitting smoking [22]. However, in Turkey, where quite successful steps have been made in the field of tobacco control in terms of regulations, it is known that unemployment is unacceptably high and, more importantly, the number of “working poor” is increasing each day.

Here, all these striking results indicate that, policies determined for tobacco control in Turkey must be combined with protective measures focusing on impoverished people and the groups exposed to social exclusion. Because, whilst the losing party in tobacco epidemic is predominantly the impoverished people, companies always make a profit out of this epidemic. In this world, where poverty and deprivation has become global, wealth is accumulated in transnational investment groups. The fact that endorsements of the six leading tobacco companies of the world has reached to 346 billion dollars and their profit has reached to 35 billion dollars in 2010 –the profit of these 6 companies in 2010 was equal to the sum of the profits of Coca-Cola, Microsoft and McDonald’s in the same year-[23], clearly demonstrates who the winner would be in this world unless precaution is taken.

Footnotes

The primary aim of this paper written by the Turkish Thoracic Society Tobacco Control Study Group in a period, in which the Turkish 2013–2017 National Tobacco Control Program has been specified, is to bring the basic philosophy and policy of tobacco control up to discussion. Therefore, the paper in question should not be considered as a review on global tobacco epidemic. Likewise, the expectation of readers from this paper should not be to obtain current information on tobacco use, epidemiology or treatment process.

For detailed information: Elbek O, Tütün Kontrolü (Included: Arslanoğlu İ -Ed-. Tıp Bu Değil 2), İthaki Publications, 2013.

For example, in a study in which the Turkish Thoracic Society and Health Institute Society investigated the consistency of exhibition of tobacco products in points of sales with the regulation, the prevalence of exhibition consistent with the regulation was found to be only 8.6%.

Despite National Tobacco Control Program put in practice in Turkey, it is striking that tobacco industry has notably increased its revenue in years.

In the “Legislation on the amendment of certain Laws and statutory decree No.375” No. 6487, which was accepted on 24 May 2013 and published in the Official Journal on 11 June 2013, this provision was changed as “In public transport vehicles of motorways including driver seats of private vehicles and those providing taxi services, railroads, maritime line and airline”.

Peer-review: Externally peer-reviewed.

Author Contributions: Concept - O.E., O.K., Z.A.A., L.A., Ç.U.K., C.Ö., L.S., P.B., E.D.; Design - O.E., O.K., Z.A.A., L.A., Ç.U.K., C.Ö., L.S., P.B., E.D.; Supervision - O.E., O.K., Z.A.A., L.A., Ç.U.K., C.Ö., L.S., P.B., E.D.; Funding - O.E., O.K., Z.A.A., L.A., Ç.U.K., C.Ö., L.S., P.B., E.D.; Materials - O.E., O.K., Z.A.A., L.A., Ç.U.K., C.Ö., L.S., P.B., E.D.; Data Collection and/or Processing - O.E., O.K., Z.A.A., L.A., Ç.U.K., C.Ö., L.S., P.B., E.D.; Analysis and/or Interpretation - O.E., O.K., Z.A.A., L.A., Ç.U.K., C.Ö., L.S., P.B., E.D.; Literature Review - O.E., O.K., Z.A.A., L.A., Ç.U.K., C.Ö., L.S., P.B., E.D.; Writer - O.E.; Critical Review - O.E., O.K., Z.A.A., L.A., Ç.U.K., C.Ö., L.S., P.B., E.D.

Conflict of Interest: No conflict of interest was declared by the authors.

Financial Disclosure: The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

REFERENCES

- 1.Geneva, World Health Organization, 2008. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008. WHO Report on the Global Tobacco Epidemic, 2008: The MPOWER Package. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oberg M, Jaakkola MS, Woodward A, et al. Worldwide burden of disease from exposure to second-hand smoke: a retrospective analysis of data from 192 countries. Lancet. 2011;377:139–46. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61388-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(10)61388-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Tobacco Control Programme Notice, October 7, 2006, 26312 Official Gazette of the Republic of Turkey.

- 4.TEKEL & TAPDK Data, 2006.

- 5.Gilmore AB, Fooks G, McKee M. A review of the impacts of tobacco industry privatisation: Implications for policy. Glob Public Health. 2011;6:621–42. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2011.595727. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2011.595727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Elbek O. Economic Policies of Tobacco. Aug 7, 2010. [Accessed Date: 5 September 2012]. http://bianet.org/biamag/tarim/123970-tutunun-ekonomi-politigi-Biamag.

- 7.Saloojee Y, Dagli E. Tobacco industry tactics for resisting public policy on health. Bull World Health Organization. 2000;78:902–10. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Özkaya T. Globalization and Agriculture Policies. [Accessed Date: May 2010]. http://www.ikt.yildiz.edu.tr/sempozyum/metin/ozkaya.pdf.

- 9.Ekonews. TEKEL, Endorsed to BAT with ceremony. [Accessed Date: 22 July 2009]. http://www.ekonews.com/index.php?page=sub&pageid=8935&supplement=20.

- 10.Tobacco Alcohol Market Regulatory Institution. 2012. [Erişim 27 Mayıs 2013]. http://www.tapdk.gov.tr/tutunmamulleri7171.asp.

- 11.Elbek O. National Legislations for Tobacco Control. In: Aytemur ZA, Akçay Ş, Elbek O, editors. Tobacco and Tobacco Control Book. First Edition. Toraks Kitapları; 2010. pp. 52–80. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Law on Prevention and Control of Hazards of Tobacco Products, number: 4207, 26 November 1996 dated and 22829 Official Gazette of the Republic of Turkey (Change, 03.01.2008 dated and Law 5727, 19 January 2008 dated and 26761 Official Gazette of the Republic of Turkey.

- 13.Hammond D. Health warning messages on tobacco products: a review. Tob Control. 2011;20:327–37. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.037630. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/tc.2010.037630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Joossens L, Raw M. Europe 2010 Tobacco Control Arrangements. European Cancer Leagues; Brussels: Mar, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Turkish Statistical Institute. Global Adult Tobacco Research. 2012. Aug 31, 2012. [Accessed Date: 10 September 2012]. http://www.tuik.gov.tr/PreHaberBultenleri.do?id=13142.

- 16.Bilir N, Özcebe H, Ergüder T, Mauer-Stender K. Tobacco Control in Turkey. Story of commitment and leadership. WHO Regional Office for Europe; Denmark: Mar, 2012. [Accessed Date: 10 September 2012]. http://www.euro.who.int/__data/assets/pdf_file/0009/163854/e96532.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jarvis MC, Wardle J. Social Patterning of Individual Health Behaviours: the case of cigarette smoking. In: Marmot M, Wilkinson RG, editors. Social Predictors of Health Insev. 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elbek O. Tobacco and Poverty. National Smoking and Health Committee. 4th National Smoking and Health Congress Book; Elazığ. 2010. pp. 80–5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Haustein KO. Smoking and Poverty. Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehabil. 2006;13:312–8. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000199495.23838.58. http://dx.doi.org/10.1097/01.hjr.0000199495.23838.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peretti-Watel P, Constance J. “It’s all we got left”. Why poor smokers are less sensitive to cigarette price increases”. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2009;6:608–21. doi: 10.3390/ijerph6020608. http://dx.doi.org/10.3390/ijerph6020608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Leinsalu M, Kaposvári C, Kunst AE. Is income or employment a stronger predictor of smoking than education in economically less developed countries? A cross-sectional study in Hungary. BMC Public Health. 2011;13:97. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-97. http://dx.doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Öztuna F, Çam G, Ayık S, et al. 10th year pre-outcomes of Smoking Cessation Clinic of Karadeniz Technical University Medical Faculty. Turkish Thoracic Society. 14th Annual Turkish Thoracic Society Congress Book; 13–17 April 2011; Antalya. SS070. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Eriksen M, Mackay J, Ross H. American Cancer Society, World Lung Foundation. The Tobacco Atlas. 2012. [Accessed Date: 10 September 2012]. http://www.tobaccoatlas.org/uploads/Images/PDFs/Tobacco_Atlas_2ndPrint.pdf.