Abstract

Objective

To adapt a validated instrument that quantitatively measures stigma among English/Swahili speaking TB (tuberculosis) patients in Kenya, a high burden TB country.

Methods

Following ethical approval, we elicited feedback on the English and Swahili translated Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI) tools through cognitive interviews. We assessed difficulties in translation, differences in meaning, TB contextual relevance, patients’ acceptability to the questions, and issues in tool structure. The interviews were audio recorded, transcribed and translated. Open coding and thematic analysis of the data was conducted by two independent researchers.

Results

Between May and September 2015 we conducted a qualitative study among 20 adult TB patients attending 11 health facilities in Nairobi County, Kenya. Most questions were understood in both English and Swahili, deemed relevant in the context of TB and acceptable to TB patients. Key areas of adaptation of the SSCI included adding questions addressing fear of infecting others and death, HIV stigma, and intimate, family and workplace relationship contexts. Questions were revised for non-redundancy, specificity and optimized sequence.

Conclusion

The adapted 8-item SSCI appears to be a useful tool that may be administered by health workers in English or Swahili to quantify TB stigma among TB patients in Kenya.

Keywords: measuring stigma, TB, Nairobi, Kenya

INTRODUCTION

In 2014, it was estimated that 9.6 million people fell ill with tuberculosis (TB) worldwide, 12% of whom were HIV-positive (World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Report, 2015). The World Health Organization End TB Strategy geared towards zero deaths, disease and suffering due to TB globally, addresses TB-related stigma in all its three pillars (World Health Organization End TB Strategy), as it is a barrier to TB control with serious health and socioeconomic consequences (Christodoulou, 2011; Courtwright & Turner, 2010; Jaramillo, 1999; Van Brakel, 2006). Weiss and Ramakrishna define health-related stigma as “a social process or related personal experience characterized by exclusion, rejection, blame, or devaluation that results from experience or reasonable anticipation of an adverse social judgment about a person or group identified with a particular health problem.” (Weiss & Ramakrishna, 2006). Drivers of stigma in TB include the fact that it is an infectious condition spread in the air and its association with HIV disease (Christodoulou, 2011; Courtwright & Turner, 2010; Daftary, 2012; Jaramillo, 1999; Kipp et al., 2011; Van Brakel, 2006). The stigma process proposed by Corrigan and Watson suggests that negative stereotype awareness, agreement and application, result in reduced self-esteem and self-efficacy (Watson, Corrigan, Larson, & Sells, 2007). In the context of TB, patients with TB may experience discrimination (enacted stigma), become aware of the negative stereotype around TB (perceived stigma) then concur that the negative stereotype applies and internalize the stigma (self-stigma). Internalized stigma potentially results in TB patients not fully seeking TB care and avoiding cooperation in having their close contacts investigated for TB (Courtwright & Turner, 2010; Van Brakel, 2006). In this way, TB stigma is not only detrimental to TB patients’ health at an individual level but may also promote further spread and drug resistance (Christodoulou, 2011; Courtwright & Turner, 2010; Jaramillo, 1999; Somma et al., 2008; Van Brakel, 2006).

Validated tools to quantitatively measure stigma in TB patients are scarce (Macq, Solis, & Martinez, 2006; Van Rie et al., 2008) and challenges in TB-related stigma tool development include the inability to capture all the feelings of TB patients (Macq, Solis, Martinez, & Martiny, 2008); and the varying cultural and TB/HIV epidemiological contexts in which they are utilized (Courtwright & Turner, 2010; Kipp et al., 2011; Macq et al., 2008). An instrument that comprehensively measures stigma among TB patients in Kenya, a high burden TB/HIV country with a low prevalence of multi-drug resistance (MDR) TB (World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Report, 2015), is envisioned in the national strategic plan (Kenya National Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis, Leprosy & Lung Health, 2015–2018), but does not currently exist. Adaptation of an existing validated stigma tool to assess TB-related stigma in this context would be a first step. The 26 item Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI) developed by Rao et al is a tool for evaluating the stigma of people with chronic illnesses designed for self-administration in the English language (Rao et al., 2009; Rao, Molina, Lambert, & Cohn). We sought to adapt a validated instrument that quantitatively measures stigma among English/Swahili speaking TB patients in a high burden TB setting in Africa.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Ethics Statement

We obtained ethical approval from the Kenyatta National Hospital/University of Nairobi Ethics Research Committee and the University of Washington Institutional Review Board.

Research Team and Re exivity

After obtaining ethical approval, the first author, a female Kenyan pediatrician with formal training and experience in qualitative research conducted the cognitive interviews without establishing a relationship with participants prior to study commencement. The second author, a female, Kenyan anthropologist with extensive training and experience in qualitative research transcribed and translated the audio recordings. These two researchers analyzed the data independently and where consensus was not reached, S.N, a female Swahili/English Translator and Communicator with over 10 years of experience in translation and localization, served as the tie breaker. The three independent multilingual researchers independently translated the original SSCI into Swahili and back into English and adapted it for health worker (HW) administration. Other members of the research team included senior researchers with extensive experience in the fields of stigma, qualitative research, TB-HIV and health economics.

Participant Selection

We selected study participants through a multi-stage sampling approach restricted to public health facilities in Nairobi County, a densely populated urban metropolis and the capital of Kenya. This comprised 13 TB clinics stratified by the level of health care provided: Kenyatta National Hospital, a tertiary referral facility; Mbagathi District Hospital, Mama Lucy Kibaki and Mathari Hospitals, secondary referral facilities; and one primary health facility randomly sampled from each of the nine sub-counties in Nairobi County. We obtained ethical approval to interview 20 participants, a sample size suggested in the literature to be sufficient to reach data saturation in a qualitative study such as ours with a narrow scope, specific sample and established theoretical framework (Morse, 2015), among other factors that contribute to adequate information power (Malterud, Siersma, & Guassora, 2015). Participants were eligible if they were aged ≥18 years, had clinician diagnosed TB and were attending the selected TB clinics. We approached participants, sought informed consent, and conducted face-to-face interviews at each selected TB clinic during hours of operation. Our goal was to achieve a representative sample with regard to the level of health facility (primary, secondary and tertiary) and sub-county distribution in Nairobi County.

The Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI)

The original 26-item SSCI is made up of 13 items that measure internalized stigma, 11 items that measure enacted stigma and two items that address disclosure concerns as a result of disease-related manifestations. It is also referred to as the Neuro-Qol (Quality of Life in Neurological Disorders) Stigma Scale and is available in Spanish, Simplified Chinese and Korean translations of the English version (“Neuro QoL,”).

Data Collection Process

No one else was present during data collection besides the participants and lead researcher, who used a cognitive interview guide, and continually revised the tool through an iterative process to incorporate TB patients’ suggestions (Willis, 2005). (Supplementary Table 1) The researcher audio recorded the interviews, took field notes and noted when data were saturated. The interviews were translated into English and transcribed verbatim. We did not repeat interviews or return transcripts to participants for comments or correction. To maintain confidentiality, we did not audio record participant names during interviews. We stored data in password protected files with access restricted to researchers, and destroyed audio-recorded files six months after transcription as per our protocol.

Analyses

Two independent researchers identified themes related to SSCI tool adaptation in advance. These included difficulties in translation, differences in meaning, TB contextual relevance, acceptability of the questions to patients, and issues in tool structure. The researchers derived sub-themes related to stigma in the context of TB in English/Swahili speaking patients in Nairobi from the data and categorized them as factors promoting TB stigma, factors reducing stigma and time. They manually coded the transcripts and also used Atlas.ti GmbH, Berlin version 7.5.10 (Student License) to manage the data. After analysis, we received and incorporated feedback on the tool from HWs.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

We interviewed 20 adult TB patients attending the study TB clinics between May and September 2015 sampled from 11 of the 13 selected health facilities in Nairobi County, Kenya. Of the 20 adults, most were male with a majority having completed primary education. Half of the participants responded in mixed Swahili and English whereas few responded in Swahili or in English. Most participants had disclosed their TB status to at least one person, and attended primary health facilities. The median age was 32.5 years (IQR 29.0–37.5), with youngest and oldest interviewees being 23 and 47 years respectively. Median time since TB diagnosis was 2 months (IQR 1.0–3.5), and median interview duration was 32.5 minutes (IQR 21.5–47.5). Three TB patients refused to participate, two due to a busy schedule and one feeling uncomfortable being involved in research. (Table 1)

Table 1.

Patient Characteristics

| Participant Characteristics | (N=20) |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Median Age (IQR) [Range] | 32.5 (29–37.5) [23,47] |

|

| |

| Male (%) | 14 (70) |

|

| |

| Completed Primary School Education (%) | 17 (85) |

|

| |

| Median Duration since TB diagnosis (IQR) [Range] | 2 (1–3.5) [0.07,8] |

|

| |

| TB re-treatment (%) | 2 (10) |

|

| |

| Voluntarily disclosed HIV+ status to the interviewer (%) | 3 (15) |

|

| |

| Multi-drug resistant TB (%) | 1 (5) |

|

| |

| Responses in mixed English and Swahili (%) | 10 (50) |

|

| |

| Responses in Swahili (%) | 7 (35) |

|

| |

| Primary health facility (%) | 14 (70) |

|

| |

| Sub-county (Health Facility) | |

| 1. Dagoretti (Kenyatta National Hospital, Mbagathi District Hospital, Waithaka Health Centre) | 5 (2,1,2) |

| 2. Embakasi (Mama Lucy Kibaki Hospital, Mukuru Health Centre) | 4 (2,2) |

| 3. Kamukunji (Eastleigh Health Centre) | 2 (2) |

| 4. Kasarani (Prison Staff Training College Health Centre) | 2 (2) |

| 5. Langata (Langata Health Centre) | 1 (1) |

| 6. Makadara (Makadara Health Centre) | 0 |

| 7. Starehe (Ngara Health Centre, Mathari Hospital) | 1 (0,1) |

| 8. Westlands (Kangemi Health Centre) | 3 (3) |

| 9. Njiru (Dandora I Health Centre) | 2 (2) |

|

| |

| Non-Participant Characteristics | (N=3) |

|

| |

| Male (%) | 2 (67) |

|

| |

| Primary health facility (%) | 3 (100) |

|

| |

| Reasons for non-participation:- | |

| 1. Busy schedule (%) | 2 (67) |

| 2. Not comfortable being involved in research (%) | 1 (33) |

Translation and Meaning of the Questions

Generally, we did not note difficulties in the translation of individual words from English to Swahili, except in one interview in which two errors were made in Question 20 and 21 which influenced the meaning of the question [Interview 2].

TB patients understood most questions well but in a few interviews we noted differences in meaning between the patient and the researcher. Patients initially interpreted ‘looking at you’ in Question 8: “Do you think that because you have TB, people avoided looking at you?” in Swahili to mean ‘looking after you’ [Interview 6, 10, 14, 16, 18 and 20]. The word ‘kuangalia’ in Swahili has two meanings, to look at and to look after. We provided further clarity to enable the patient to understand the question during the interview process. We also adjusted the question in the final harmonized Swahili SSCI to ‘kukuangialia usoni/machoni’ – ‘to look at you in the face/eye’ to make this distinction. Another Swahili word with two meanings is ‘rafiki’, which in this context could mean a general friend or a romantic friend, was used in Question 22: “Do you think that because you have TB, you avoided making new friends?” and some TB patients explicitly requested a distinction [Interview 16 and 18]. We learnt from other interviews that the context of relationships was an important aspect in TB stigma. We distinguished that various levels of relationships were necessary, particularly general and romantic relationships. Patients occasionally misinterpreted ‘physical limitation’ in Question 17: “Do you think that because you have TB, you felt embarrassed because of your physical limitations?” for ‘weight loss’ [Interviews 5, 12 and 14]. In the final harmonized SSCI tool, the question was revised to provide situations in which one would be limited physically – at home/school/work. Participants initially misinterpreted, ‘felt left out of things’ in Question 4: “Do you think that because you have TB, you felt left out of things?” in Swahili to mean ‘felt left behind’ [Interview 1 and 13]. For clarity we added an option in Swahili back translated into English as “you have felt excluded from things”. We also noted the initial meaning of Question 10: “Do you think that because you have TB, you worried about other people’s attitudes towards you?” to be difficult to understand [Interview 1].

Relevance of Questions in the context of Tuberculosis

Most of the patients deemed all 26 questions in the SSCI tool to be relevant in the context of TB. Although responses to each question varied from patient to patient, TB patients provided rich and diverse perspectives which clearly depicted that the questions were applicable to TB stigma.

Question 18: “Do you think that because you have TB, you felt embarrassed about your speech?” was one such question. While patients could hardly see a relationship between TB and speech, others viewed the question in the context of their appearance. Some TB patients cited personal experiences where they felt embarrassed about how they appeared when they talked, particularly when coughing uncontrollably, coughing blood or panting due to breathlessness. Other patients felt embarrassed because people would judge the content of their speech and ignore their points because they suffered from TB. We noted that this question was not very specific and omitted it in the final adapted SSCI for TB stigma, but retained the question on appearance, which was the context in which most TB patients responded to this question.

Another question with differing responses was Question 13: “Do you think that because you have TB, it was hard to stay neat and clean?” Although possible, some TB patients felt that being dirty and disorganized was just an excuse when one had TB, whereas others could consider situations when this could apply, and even relate to situations where they were too sick from TB to bathe or stay clean. Nonetheless, most TB patients responded that for them it was not hard to stay neat and clean. We noted that TB severity and substance abuse may influence the ability of TB patients to perform tasks which require support from caregivers, and thus considered them important patient variables to collect. Similar to question 18, we omitted this question but added a question on support from family, friends, co-workers/school-mates or employers, as this was connected and emerged as a major theme.

Question 9: “Do you think that because you have TB, strangers tended to stare at you?” also elicited differing responses. Some TB patients brought out an important aspect of disclosure: strangers did not know they had TB, so why would they stare? Patients, especially those with physically apparent symptoms agreed that strangers tended to stare at them, whereas TB patients who did not have distinctive signs of illness could not understand this question since there had no tell-tale signs. We also omitted this question but recognized the importance of collecting data on disclosure/TB signs and retaining the question on appearance.

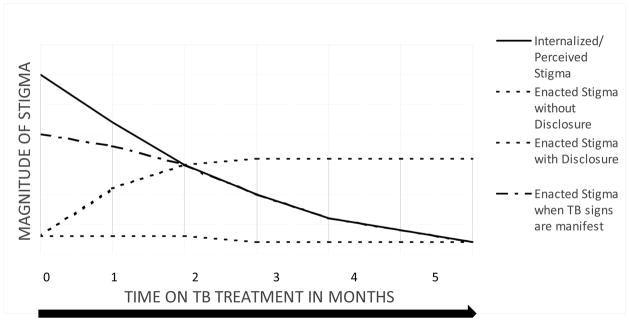

We classified the emerging major themes related to TB stigma in this context under three intertwined categories: factors promoting TB stigma, factors reducing stigma, and time which formed the basis of the 8-item adapted SSCI for TB stigma. (Figure 1, Figure 2, Table 2–4 and Supplementary Table 2)

Figure 1.

Factors Promoting TB Stigma and Factors Reducing TB Stigma

Figure 2.

Internalized, Perceived and Enacted TB Stigma in Relation to Time

Table 2.

Interview Characteristics (N=20)

| Characteristic | Q1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Difficulties in translation | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 01/20 | 01/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 |

| 2 | Differences in meaning between the interviewer and patient | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 02/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 06/20 | 0/20 | 01/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 03/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 01/20 | 01/20 | 02/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 |

| 3 | Relevance in the TB context | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 14/20† | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20† | 16/20† | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 18/20† | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 | 20/20 |

| 4 | Patients’ acceptability to the questions | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 04/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 01/20 | 0/20 | 01/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 | 0/20 |

| 5 | Issues in the tool structure 5A. Format |

Redundancy and sub-optimal flow - 05/20 [ID: 9,10,12,17,19] Incorrect intonation - 01/20 Suggestions:-

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5B. Content |

Suggestions:-

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 5C. Ranking [5,3, E, N] |

Preference:- 5 point scale (2/8) – gives more options 3 point scale (4/8) – brevity (people are busy – they go to work, simpler than the 5 point scale) Either scale (1/8) No scale (1/8) – restricts responses |

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Q4 meaning (left out of things) – interview 1&13 in Swahili; Q6 sensitivity (make fun of) – interview 5,6,7&9 in English & Swahili; Q8 meaning (kuangalia has 2 meanings to look at and to look after requires clarity) interview 6,10,14,16,18,20 in Swahili; Q10 meaning interview 1 in Swahili; Q17 meaning (physical limitations) in interview 5,12,14 in English and Swahili; Q20 & 21 translation – interviewer asked the questions incorrectly in interview 2 in Swahili [initial set of interviews];Q20 & 22 sensitivity – interview 7 in Swahili; Q22 meaning (rafiki has 2 meanings - friend in general/romantic friend) interview 16&18 in Swahili.

Diverse cases.

Table 4.

Adapted 8-Item Stigma Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI) for English/Swahili Speaking Patients with Tuberculosis

A. Factors Promoting TB Stigma

One of the main factors promoting TB stigma was fear of infecting others or experiencing exclusion by others in the community for fear of getting infected. TB Patients reported that they would stay away from others including their intimate partners for fear of infecting them. [Interview 5]: “I may transmit (my TB) infection, so I keep off.” [Interview 17]: “I have been concerned that I will transmit TB to my husband if we sleep together, so I told him that the doctor disallowed us to sleep together for the period I am on TB treatment.” Enacted stigma due to community members’ fear of getting infected with TB was most apparent when a patient had manifest signs such as a persistent cough or hemoptysis. [Interview 18]: “The reason they were running from me is (because) there is a day I coughed blood. I was at home, at my mother’s place. Now on coughing blood, my brother saw. He gave an order that even food, when I go there, I be given with my plate and it is put aside. When I come, I am given (food) with it (that plate) … The cup itself that they put tea for me, is thrown in the toilet.”

TB patients also reported the lack of support from members of the community including family, friends, co-workers and/or employers as a factor promoting stigma. Patients expressed that it was more painful when they experienced stigma from relationships that they regarded to be close such as intimate and family relationships. [Interview 3]: “So I wonder: What is the reason that is keeping her (my sister) away from me? Is it the fear that maybe she has helped me and now she is tired or is she scared that she will get infected?” [Interview 12]: “(Some people can seem uncomfortable with me). Yes it can happen with close people. And they can take you as an outcast or something like a taboo and say that TB is a bad disease, that you have brought shame. It depends on the understanding. So close people, that can be family members, it can be a relationship partner and sometimes family members, make it more painful. Their attachment is too close, they are the ones you rely on for confidence, for courage. So if it becomes negative to them, and they treat you in some other way, it will stress you.” Other factors promoting TB stigma identified were fears or worries related to TB outcomes including changes in appearance, lengthy treatment duration, drug side effects and death.

Disclosure of TB status was mainly influenced by HIV stigma; and the nature of the friendship. TB patients reported that it was difficult to disclose their TB status as community members immediately assumed that they were HIV co-infected. TB patients’ disclosure of their TB status was easier if they considered the nature of the relationship to be close. [Interview 9]: “Even telling people right now, somebody who is not a close friend or maybe can be a friend, that I have TB is not easy, because I feel embarrassed. I feel bad. It is a bad disease. It is like HIV.” However, patients reported that they found it difficult to disclose their TB status to their intimate partners, despite this being considered a close relationship. [Interview 11]: “I told my girlfriend that I was being treated for pneumonia. If you tell them TB, some ladies will turn off quickly. She’ll not be getting your attention and maybe she’ll go away. So you have to cover it a little.” [Interview 14]: “I have not yet told people I have it (TB) but I think they (others) can avoid somebody. You know some people think TB is associated with other things. Like the way you get AIDs people are.….you know people fear, they stigmatise others, not really nowadays but somehow in a small way. It has still not ended. They can think that this person is sick with some other things, especially friends, maybe boyfriend. He (the boyfriend) can think maybe you are sick with things like HIV/AIDs.” Additionally, disclosure of a patient’s TB status was perceived to promote enacted stigma. [Interview 10]: “I have never told anyone that I have TB. They know I have ‘Allergy’. If they knew(I have TB) they would change.”

TB patients and their communities exhibited misconceptions on TB transmission such as sharing utensils, sharing common cigarettes, sexual contact and acts of the devil; and that children/old people would not get TB; and a poor understanding of strategies to prevent TB and the reason for HIV testing. A lack of a proper understanding of TB was the underlying factor promoting TB stigma. This may have been perpetuated by lack of health education provision to individual patients and the community. [Interview 11]: “I ask myself, where did I get this TB? Some people are patients and they don’t understand. Nobody educated me. Still, no one has educated me.” [Interview 9]: “So my embarrassment is the way I used to take others (with TB). So it (TB) has come to me. The way I used to think about others, is the same way they are now thinking about me. That bad thought I had about people who have TB, it’s not that they are having it, but personally I see as if somebody can think of me in that way.” (Figure 1A)

B. Factors Reducing TB Stigma

We identified health worker support through health education as one of the main factors decreasing TB stigma. In addition, TB patients also reported that belief in God influenced their self-efficacy. [Interview 17]: “(When I learnt that I have TB), I thought I will either die or recover because I have never gotten it (TB). I went and asked the doctor. The doctor told me: ‘Have faith and you will be well’. (The doctor told me that) If I use those medicines correctly, I would recover … So from that point I had faith. So I don’t have bad thoughts. I have thoughts of telling God to heal me. I am totally free.”

Relationship support from family, friends (including peers/friends who had experienced TB), coworkers and employers which could be physical, financial, emotional or spiritual; and non-disclosure of TB status decreased TB stigma. [Interview 12]: “No (I didn’t feel embarrassed about my situation). As for me no, because I knew people who ….I had a very good idea about TB. Believing at first is what I had a denial, but when it came to my mind that I have it (TB), I now concentrated on healing myself. (I learnt about TB) through people who experienced it, through some awareness programmes and through some advertisements, but mostly through people; people with experience. Yes (some of the people who have experienced TB are my friends), because I live in a place where there are many people. I live in the other part of town. So you get people here with this disease. So many people with the disease. So, many are friends with TB. I have had of one who died but it was not from TB, but the others are cured.”

Individual patient outlook also decreased TB stigma and positively influenced TB patients’ self-esteem/self-efficacy. Interview 10]: “You know for TB, most people say it is a bad disease, but when you understand what it is ….(TB) is like an accident. I must accept that accident, because I am not the one who looked for that accident … If I think about what they (others) are thinking about me, I will not be able to deal with my treatment (and) my life well … What is left for me is to leave what they are thinking about me, and continue with my life normally.”

The overall underlying factor reducing TB stigma was a proper understanding of TB by individual TB patients as well as their community members. [Interview 4]: “I understand the disease (TB). I will recover because people recover.” [Interview 12]: So they (close people, that can be family members, it can be a relationship partner and sometimes family members) have to be happy with you and they also have to understand the disease. They make it lighter for you and say ‘Yes, that is a small thing. That is not a big thing.’ TB nowadays is another small thing, not like the other days. So you have to get people who are ….a strong foundation and people who are close to you.” (Figure 1B)

C. Internalized/Perceived TB Stigma and Enacted Stigma in Relation to Time

TB stigma appeared to change based on time between diagnosis and treatment. Initially patients reported both internalized and perceived TB stigma especially prior to health education/treatment. Patients who had commenced treatment and noted clinical improvement tended to be more positive, with reduction in internalized/perceived stigma with time on TB treatment. [Interview 12]: “It was a series of thoughts (that came to my mind in the last two months with TB). There were first thoughts, and they were too many thoughts. And they kept on reducing. And right now there are some thoughts also. At first, there were some thoughts that were negative: That I can lose my health at any time; TB is a disease that is so severe; and TB is a disease that you have to be treated for a very long time, and if you don’t take care of yourself very carefully, the treatment can backfire. So it made me get some phobia myself, but I controlled some thoughts after some help from the nurses here, and I got some awareness. And through taking the treatment, it happened for itself. It is not that I was given the awareness, it happened for itself. The drugs were working in the body and then right now, those thoughts are not there. Now they are transformed to be positive.”

Conversely, patients who reported persistent symptoms despite treatment tended to be negative. [Interview 10]: “I am not far from people. Apart from now I have told you this disease, it is like, I think as if am doing zero work of using medication. Sometimes I feel pain because my children are small, so it is bad if there is no work that these medicines are doing. Because let us say I can leave my children, that is the only thing that is making me feel different. I continue using these medication and am not getting well. That is the only thing that makes me feel distant from people. It is increasing, so I think I might die, yet am using medication. But if this disease can be treated and I continue getting well and I improve, I cannot feel distant from people. I feel distant from people because of only that; am using medicines and am not getting well. Now it is like am doing nothing. But let us say, if I use the medicines and I get well, I cannot feel distant from people.”

Participants tended to disclose their TB status more over time, and if they shared their diagnoses with negative individuals, they experienced more enacted stigma. Similarly, less/no disclosure resulted in less/no enacted stigma. TB patients with manifest signs e.g. persistent cough, hemoptysis or weight loss, experienced enacted stigma much earlier even without disclosure of their TB status, and the enacted stigma decreased with time on TB treatment as the patient improved. (Figure 2)

Issues in Tool Structure

From TB patients’ responses during the cognitive interviews, we noted redundancy and suboptimal flow in the questions. Although we had a very narrow scope i.e. the 26-item SSCI, one of the patients suggested that we might gain richer responses if we simply asked about the thoughts of TB patients. Other participants re-iterated that TB patients wanted to be listened to [Interview 10, 12, 16]. After introducing this open question first and re-ordering the questions for optimal flow, the interviews enabled us to glean deeper into TB stigma while still focusing on the 26-item of the SSCI. The duration of responses to this open question ranged from one to 13 minutes.

With regard to content, one TB patient pointed out explicitly that there was no specific question on the various levels of relationships including family, friends, co-workers and employers and suggested this addition [Interview 4]. This TB patient’s observation further solidified our decision to include this dimension as we found that support from various relationships was an important sub-theme of TB stigma that emerged from our data. Another TB patient suggested that we include a question on TB treatment and outcomes. From the data, components that were brought up included treatment adherence, drug side effects, cure/recovery, non-cure/non-recovery and death. The most common aspects that were discussed by the patients with regard to TB stigma were worry of not recovering and other people assuming they would die. We incorporated these latter two in the 8-item adapted SSCI, and included an ‘other, specify’ section for additional thoughts, worries or fears of TB patients.

We explored response option preferences in eight interviews, asking TB patients to choose between a 5-point and a 3-point Likert scale of frequency of experiences ranging from never to always. Four of 8 patients preferred the 3-point Likert scale for its simplicity and brevity, especially because “people had other things to do, like go to work”. Two out of 8 patients preferred the 5-point Likert scale because it provided more options. One patient was ambivalent and another felt that this scale restricted her responses. Although most of these TB patients understood both Swahili and English, some felt the rating in English was simpler. All TB patients whom we asked found it easy to point on a chart compared to having the options committed to memory or the health worker repeating the options after each question.

Patients’ Acceptability to the Questions

Most TB patients liked these questions and made it quite clear that they want to be listened to. They found the questions acceptable, relevant and helpful because they reduced the fear and provided a sense of relief and hope through unburdening. We questioned the influence of positionality of the interviewer being a health-worker when some patients stated that all the questions were good and “you are a doctor”. Despite this concern, we were encouraged that some TB patients were confident in stating which questions they found ‘sensitive’.

Four TB patients did not find Question 6 acceptable, “Do you think that because you have TB, people made fun of you?” These patients were alarmed at how someone would make fun of one who was sick. “They cannot make fun of me because it is a disease which is not your fault.” [Interview 15]. Some patients could relate to the superficial and deeper meanings of making fun of TB patients. For example, there were TB patients who were told by their co-workers/friends “Unadedi/Unaenda”, Swahili slang to jokingly mean ‘you are dying’ [Interview 9, 20]. For others, the jokes were around wasting/weight loss. Although this question was omitted, questions relating to fear of death and appearance were retained.

One TB patient found Question 20, “Do you think that because you have TB, you will blame yourself?” and Question 21, “Do you think that because you have TB, you will not make friends?” to be sensitive [Interview 15]. These two questions were omitted, but related questions were retained: TB patients worrying about being a burden to others, and lack of support from friends leading to possible rejection/loss of friends.

DISCUSSION

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study globally to adapt the SSCI for TB-related stigma, and also adapt a tool to measure stigma for English/Swahili speaking patients with TB particularly in an urban context in sub Saharan Africa. From the literature we identified three tools that quantitatively measure TB stigma: the 10-item tool adapted by Macq et al in Nicaragua from the Internalized Stigma for Mental Illness (ISMI) scale by Ritsher et al (Macq et al., 2006; Macq et al., 2008); the TB and AIDS Scale developed by Van Rie et al in Thailand with three scales: 12-item experienced TB stigma scale, 11-item perceived TB stigma scale and a 10-item perceived AIDS scale (Kipp et al., 2011; Van Rie et al., 2008) and a 5-item scale developed by Chowdhury et al in Bangladesh to measure enacted TB stigma (Chowdhury, Rahman, Mondal, Sayem, & Billah, 2015). The 8-item adapted SSCI for TB stigma we propose for the assessment of TB stigma in Nairobi is consistent with the scales previously developed in three domains. It measures: perceived and enacted TB stigma as the Macq, Van Rie and Chowdhury tools; internalized TB stigma as the tool by Macq et al; HIV perceived stigma in the context of TB disease as the Van Rie tool. The specific 8-items in our adapted scale center around fear of infecting others and death/non-recovery; feeling like a burden; lack of support from intimate/family/work-place relationships (Dias, de Oliveira, Turato, & de Figueiredo, 2013) and HIV stigma are consistent with the literature (Chang & Cataldo, 2014; Courtwright & Turner, 2010; Van Rie et al., 2008; Wynne et al., 2014). To obtain a broader spectrum of responses, we propose to employ the 5-point Likert scale ranging from rarely to always and plan to formally test this tool’s usability in a larger upcoming study.

In our analysis, time was a major emergent theme that influenced internalized, perceived and enacted stigma in different ways thus necessitating measuring TB stigma at baseline and at different time points, as ideal time points and references may not be known. In an interventional study in Nicaragua, Macq et al assessed TB stigma at 15 days and at 2 months since starting TB treatment (Macq et al., 2008), but temporal changes in internalized, perceived and enacted stigma within TB patients were not reported. Other reference points to time apart from commencement of TB treatment may include diagnosis, health education provision and disclosure. Additional covariates noted to potentially influence TB stigma in our context and were consistent with other studies included: age, gender, level of education (Courtwright & Turner, 2010), religion; education; income; TB knowledge on the cause, transmission, cure; knowing a person with TB; HIV status; and TB symptoms (Kipp et al., 2011).

The strength of our adapted tool lies in allowing for qualitative and quantitative assessment of TB stigma gleaned from TB patients in this context. Approaching TB stigma from an individual perspective and not just the public health one is imperative (Somma et al., 2008). Although it has been documented that no tool can be exhaustive regarding TB stigma (Courtwright & Turner, 2010), we think that beginning with an open question inquiring about the thoughts/worries/fears of TB the patient in the 8-item adapted SSCI for TB stigma may help capture aspects of TB stigma that are important to each TB patient. In the future, our 8-item adapted SSCI designed to measure TB stigma may be utilized to test the effectiveness of TB stigma interventions, similar to the adapted ISMI by Macq et al. (Macq et al., 2008).

Additionally, this is the first study to elaborately translate the original 26- item SSCI in English into Swahili through a process of iteration by a multi-disciplinary team incorporating feedback from English/Swahili speaking patients. English and Swahili are the two dominant languages spoken by most Kenyans. While English is the language of instruction in all educational institutions, Swahili is the language of daily interactions with people of different ethnic backgrounds in Kenya and is widely spoken in Eastern and Central Africa (Abuom & Bastiaanse, 2012). The translated SSCIs may be useful for researchers conducting stigma studies related to chronic illness in English/Swahili speaking populations in the future. (Supplementary Table 2)

TB awareness in Nairobi County is almost universal and approximately 90% of both the women and men who are aware of TB know that TB is spread in the air by coughing (Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2014.). It was therefore unsurprising to find that most participants knew that TB is spread in the air by coughing, however TB patients and their communities also harbored incorrect notions of TB transmission. The Kenya Demographic and Health Survey did not report on the proportion of those who also mentioned incorrect routes of TB transmission (Kenya Demographic and Health Survey 2014.). Our team identified potential areas for TB patient empowerment that may be pertinent in averting TB stigma including knowledge on prevention despite infectiousness, cure despite deadliness, association with HIV in some but not all TB patients; anticipation of potential changes in appearance; and avoidance of negative feelings as the situation is temporary with proper treatment.

We envisage that HWs can utilize this one page tool to elicit rapid feedback from TB patients; identify individual gaps that may promote TB stigma at a glance; and facilitate a conversation that will enable TB patients gain a proper understanding of TB. HWs are not limited to clinicians and nurses at the health facility, but also include social workers and community health workers who are very crucial cadres of HWs in TB care. We envision that this tool will be simple to administer and findings will be easily interpreted by HWs. The embedded action points based on the potential areas for TB patient empowerment we identified in this study could offer an opportunity for HWs to re-inforce health education provided that it is specific to the gaps they will note. In addition, this tool may facilitate seamless follow-up among different HWs and potentially allow for audit of care provision related to TB stigma. Furthermore, this tool could be used for comparing TB-related stigma across various health facilities for monitoring and evaluation purposes.

Since cognitive issues are dynamic, we propose that this tool be used at diagnosis prior to treatment commencement as a baseline, at the end of the first month and thereafter monthly. This would assist HWs to consistently address stigma and reinforcing key messages tailored for each patient. These timings would align with routine TB follow-up visits, but may require to be individualized based on prior findings. Optimal timings for assessment could be piloted. The health workforce in many low and middle income countries is constrained, and additional tools could be considered burdensome. The tool’s utility and implementation challenges will be evaluated in a planned future study. This proposed tool has the potential for global adaptability. Translation to common languages is necessary for utilization in varied contexts. In addition, it is important to recognize unique drivers of TB epidemiology in context such as HIV prevalence.

LIMITATIONS

Positionality was a potential bias in this study likely reduced because the interviewer did not work in any of these TB clinics. We were not able to assess potential stigma promoted by HWs as the 8-item adapted SSCI is a HW administered tool. Although self-administered tools are superior in this respect, this approach may not be pragmatic in the context of busy health facilities.

CONCLUSION

In conclusion, we successfully adapted an existing validated 26-item SSCI stigma assessment tool into a shorter locally contextualized 8-item SSCI, which may be administered by HWs in English or Swahili to quantify stigma among TB patients in Kenya. We will assess its utility in quantifying TB stigma in a larger population in the next phase of this study.

Supplementary Material

Table 3.

Adapting the 26-Item Scale for Chronic Illness (SSCI) into an 8-Item SSCI for English/Swahili Speaking TB Patients

| No. | 26–Item SSCI | Adapted 8–Item SSCI for TB-related Stigma | RATIONALE/JUSTIFICATION |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 |

†You felt embarrassed in social situations [Q7] (8/20) †You worried about other people’s attitudes towards you [Q10] (3/20) *You were unhappy about how your situation affected your appearance [Q12] (20/20: 10 unhappy; 10 fine) †You felt embarrassed about your situation [Q16] (5/20) †You felt embarrassed about your speech [Q18] (6/20) †You felt different from others [Q19] (1/20) |

You were unhappy about how TB affected your appearance? *Reference to how TB affects appearance [20/20 interviews]

|

We noted redundancy in questions 7, 10, 12, 16, 18 and 19 of the original SSCI from the patients’ responses. Question 12 best captured aspects of embarrassment, unhappiness and the feeling of being different with regard to how TB affected the appearance of patients and was thus retained. Examples of unhappiness due to how TB affected patients’ appearance included coughing (coughing continuously in social gatherings, coughing when speaking, and coughing blood); weight loss (looking very thin); and skin changes such as altered pigmentation/itchy skin that were adverse reactions of TB treatment. |

| 2 | Some people have seemed uncomfortable with you [Q1] (3/20) You felt distant from other people [Q3] (4/20) You felt left out of things [Q4] (3/20) You felt embarrassed in social situations [Q7] (1/20) You worried about other people’s attitudes towards you [Q10] (1/20) You avoided making new friends [Q22] (1/20) |

You avoided others for fear of infecting them with TB? Reference to avoiding others specific to fear of infecting them with TB [11/20 interviews] |

Patients’ responses from questions 3, 4, 10 and 22 on the feeling of being distant/left out/avoiding making new friends centered on avoiding others for fear of infecting them with TB, a major factor identified to be associated with TB stigma promotion. We thus modified these four related questions and included the phrase on ‘fear of infecting them with TB’ to be specific. |

| 3 |

†You felt distant from other people [Q3] (1/20) †Some people have seemed uncomfortable with you [Q1] (1/20) People made fun of you [Q6] (2/20) †You felt embarrassed in social situations [Q7] (1/20) †Strangers tended to stare at you [Q9] (1/20) †You worried about other people’s attitudes towards you [Q10] (3/20) †You were treated unfairly by others [Q11] (1/20) †You felt embarrassed about your situation [Q16] (2/20) †You felt embarrassed because of your physical limitations [Q17] (2/20) †You avoided making new friends [Q22] (1/20) †You worried that people will tell others about your situation [Q24] (1/20) † Responses to open questions (2/20) |

You worried that you will not recover from TB/may die? Reference to TB treatment outcome of cure/non-recovery/death [20/20 interviews]

|

A major emergent theme was fear of death or non-recovery apparent from unlikely questions such as 6, 9 and 10 and general conversation triggered by open questions. TB patients also recommended that a question on TB outcomes/treatment be included. We therefore included a new question specific to worry about death or non-recovery as there was no question on this in the original SSCI. |

| 4 |

†It was hard for you to stay neat and clean [Q13] (4/20) *You worried that you were a burden to others [Q15] (20/20: 12 burden; 8 not a burden) †You felt embarrassed about your situation [Q16] (3/20) †You felt embarrassed because of your physical limitations [Q17] (6/20) †You tended to blame yourself for your problems [Q20] (2/20) |

You worried that you were a burden (physically/financially/emotionally) to others? *Reference to burden[20/20 interviews]

|

Questions 16, 17 and 13 were redundant with patients’ response centered on worry of being a physical burden. Patients distinguished that the context of being a burden went beyond the physical domain to include emotional and financial aspects, which patients distinguished. This worry of being a burden tended to result in patients blaming themselves for their problems. We therefore retained question 15 which captured the patients’ responses best and modified it to include a category for patients to explicitly clarify the type of burden they were experiencing as this was not captured explicitly in the original SSCI. |

| 5 |

You were careful who you told about your situation [Q23] (20/20) You worried that people will tell others about your situation [Q24] (20/20) Responses to open questions (1/20) |

You were careful who you told you have TB? Reference to being careful on TB status disclosure or worry that people will tell others: [20/20 interviews]

|

Enacted stigma was influenced by disclosure. Disclosure of TB status was mainly influenced by the closeness of the friendship and HIV stigma. Question 23 and 24 were redundant and therefore question 23 was retained qualitatively and quantitatively. |

| 6 | Some people have seemed uncomfortable with you [Q1] (8/20) Some people have avoided you [Q2] (6/20) People were unkind to you [Q5] (3/20) People avoided looking at you [Q8] (3/20) You were treated unfairly by others [Q11] (4/20) You were careful who you told about your situation [Q23] (1/20) People in your situation lost their jobs when their employers found out about it [Q25] (1/20) You lost friends when you told them about your situation [Q26] (1/20) Responses to open questions (4/20) |

Some people avoided you, for fear of infecting them? Reference to some people avoiding TB patients specific to fear of infecting others with TB [16/20 interviews] |

Fear of infection went both ways. TB patients experienced being avoided by others stemming from the community’s fear of TB patients infecting them. Responses to this question also came up when questions 1, 5, 8, 11, and 26 came up implying redundancy. Avoidance occurred especially when patients had disclosed their TB status as from responses to questions 23 and 24. Question 2 of the original SSCI was retained and modified to include the phrase on ‘fear of infecting them with TB to be specific as done in question 2 of the adapted 8-item SSCI. |

| 7 | Some people have avoided you [Q2] (1/20) You felt embarrassed in social situations [Q7] (2/20) Strangers tended to stare at you [Q9] (2/20) You worried about other people’s attitudes towards you [Q10] (4/20) You were treated unfairly by others [Q11] (1/20) People tended to ignore your good points [Q14] (2/20) You felt embarrassed about your situation [Q16] (2/20) You felt embarrassed because of your physical limitations [Q17] (1/20) You felt different from others [Q19] (1/20) You tended to blame yourself for your problems [Q20] (2/20) You avoided making new friends [Q22] (1/20) You were careful who you told about your situation [Q23] (2/20) You worried that people will tell others about your situation [Q24] (2/20) Responses to open questions (3/20) |

You worried that some people assumed you have HIV because you have TB? Reference to some people assuming you have HIV because you have TB [12/20 interviews] |

HIV stigma was a major factor that influenced TB stigma and disclosure of TB status. This emerged from patients’ responses to questions 2, 7, 9, 10, 14, 16, 17, 19, 20, 22, 23 and 24, as well as responses to open questions. We therefore added a new question specific to the assumption of having HIV as there was no question on this in the original SSCI. |

| 8 | People were unkind to you [Q5] (17/20) You were treated unfairly by others [Q11] (17/20) People tended to ignore your good points [Q14] (16/20) Some people acted as though it was your fault [Q21] (14/20) *You were careful who you told about your situation [Q23] (17/20) *You worried that people will tell others about your situation [Q24] (16/20) |

Some people did not support you (physically/emotionally/financially) because you have TB? Reference to lack of support of any kind because of having TB: [20/20 interviews] |

Similar to the question on worry about being a burden, patients distinguished that lack of support was manifested in various forms: physical, financial and emotional. Although there was no question specific to lack of support in the original SSCI, patients responses to questions 5, 11, 14, 21, 25 and 26 addressed this major factor identified to promote TB stigma. *Disclosure of TB status to others increased this form of enacted stigma as evident from responses to questions 23 and 24. According to the TB patients, the closer the relationship, the more it hurt if there was lack of support. Similar to distinguishing the various forms of support, TB patients also distinguished the various types of relationships which fell into five general categories focusing on intimate, family and workplace relationships. The most extreme form of lack of support in a relationship was rejection/abandonment; or being fired from work. Although all TB patients felt that other TB patients may lose their jobs when their employers find out about their TB status, none of the TB patients had been fired from work because of TB. |

| □ Husband/Wife/Boyfriend/Girlfriend (3/20) He/she rejected/left me.(1/20) |

|||

| □ [Other] Family Members (4/20) Some rejected/left me. (3/20) |

|||

| You lost friends when you told them about your situation [Q26] (2/20) | □ Friends (17/20) Some rejected/left me. (2/20) |

||

| □ Co-workers/Schoolmates (3/20) Some rejected/left me. (1/20) |

|||

| People in your situation lost their jobs when their employers found out about it [Q25] (20/20) | □ Employer/Teacher/Warden* (3/20) I was fired from work/chased from school.(0/20) |

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Diana Marangu is a recipient of the International AIDS Research Training Program (IARTP) MPH-PhD Implementation Science Scholarship funded by the Fogarty International Centre, National Institutes of Health (NIH) (1 D43 TW009580). Grace John-Stewart holds an NIH K24 Mentoring Award (K24 HD54314).

We wish to acknowledge all the TB patients who participated in this study, the HWs who provided feedback for the adapted SSCI for TB stigma at the 13 study sites, the National TB Program of Kenya, the Nairobi County Health Services Sector, Kenyatta National Hospital, Mbagathi District Hospital, Mama Lucy Kibaki Hospital, Mathari Hospital, Dandora I, Eastleigh, Kangemi, Langata, Makadara, Mukuru, Ngara, Prison Staff Training College, Waithaka Health Centre, University of Nairobi, University of Washington, International AIDS Research Training Program and all other individuals and institutions that provided support to the ‘TB Kwisha’ Study.

Footnotes

Authorship Contribution:

Diana Marangu conceived and designed the study; and substantially contributed to data acquisition, analysis and interpretation; drafting the article and final approval of the version to be published. Hannah Mwaniki substantially contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. Salome Nduku substantially contributed to analysis and interpretation of data, and final approval of the version to be published. Elizabeth Maleche-Obimbo substantially contributed to study design and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. Walter Jaoko substantially contributed to study design and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. Joseph Babigumira substantially contributed to study design and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. Grace John-Stewart substantially contributed to study design and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published. Deepa Rao substantially contributed to study design and interpretation of data, revising the manuscript critically for intellectual content and final approval of the version to be published.

Conflict of Interest: None

Supplementary Material: Supplementary Table 1, Supplementary Table 2, and the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative studies (COREQ) Checklist attached

References

- Abuom TO, Bastiaanse R. Characteristics of Swahili-English bilingual agrammatic spontaneous speech and the consequences for understanding agrammatic aphasia. Journal of Neurolinguistics. 2012;25(4):276–293. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroling.2012.02.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chang SH, Cataldo JK. A systematic review of global cultural variations in knowledge, attitudes and health responses to tuberculosis stigma. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(2):168–173. i–iv. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury MR, Rahman MS, Mondal MN, Sayem A, Billah B. Social Impact of Stigma Regarding Tuberculosis Hindering Adherence to Treatment: A Cross Sectional Study Involving Tuberculosis Patients in Rajshahi City, Bangladesh. Jpn J Infect Dis. 2015;68(6):461–466. doi: 10.7883/yoken.JJID.2014.522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christodoulou M. The stigma of tuberculosis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2011;11(9):663–664. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(11)70228-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Courtwright A, Turner AN. Tuberculosis and stigmatization: pathways and interventions. Public Health Rep. 2010;125(Suppl 4):34–42. doi: 10.1177/00333549101250S407. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daftary A. HIV and tuberculosis: the construction and management of double stigma. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74(10):1512–1519. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.01.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dias AA, de Oliveira DM, Turato ER, de Figueiredo RM. Life experiences of patients who have completed tuberculosis treatment: a qualitative investigation in southeast Brazil. BMC Public Health. 2013;13:595. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo E. Tuberculosis and stigma: predictors of prejudice against people with tuberculosis. J Health Psychol. 1999;4(1):71–79. doi: 10.1177/135910539900400101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kenya Demographic and Health Survey. 2014 Retrieved from http://statistics.knbs.or.ke/nada/index.php/ddibrowser/74/export/?format=pdf&generate=yes.

- Kenya National Strategic Plan for Tuberculosis, Leprosy & Lung Health. 2015–2018 Retrieved from http://www.nltp.co.ke/docs/NationalStrategicPlan2015-2018.pdf.

- Kipp AM, Pungrassami P, Nilmanat K, Sengupta S, Poole C, Strauss RP, … Van Rie A. Socio-demographic and AIDS-related factors associated with tuberculosis stigma in southern Thailand: a quantitative, cross-sectional study of stigma among patients with TB and healthy community members. BMC Public Health. 2011;11:675. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-11-675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macq J, Solis A, Martinez G. Assessing the stigma of tuberculosis. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11(3):346–352. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Macq J, Solis A, Martinez G, Martiny P. Tackling tuberculosis patients’ internalized social stigma through patient centred care: an intervention study in rural Nicaragua. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:154. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malterud K, Siersma VD, Guassora AD. Sample Size in Qualitative Interview Studies: Guided by Information Power. Qual Health Res. 2015 doi: 10.1177/1049732315617444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morse JM. Data were saturated …. Qual Health Res. 2015;25(5):587–588. doi: 10.1177/1049732315576699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neuro QoL. Retrieved from http://www.healthmeasures.net/explore-measurement-systems/neuro-qol/intro-to-neuro-qol/available-translations.

- Rao D, Choi SW, Victorson D, Bode R, Peterman A, Heinemann A, Cella D. Measuring stigma across neurological conditions: the development of the stigma scale for chronic illness (SSCI) Qual Life Res. 2009;18(5):585–595. doi: 10.1007/s11136-009-9475-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao D, Molina Y, Lambert N, Cohn SE. Assessing Stigma among African-Americans Living with HIV/AIDS. Stigma and Health. doi: 10.1037/sah0000027. In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somma D, Thomas BE, Karim F, Kemp J, Arias N, Auer C, … Weiss MG. Gender and socio-cultural determinants of TB-related stigma in Bangladesh, India, Malawi and Colombia. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2008;12(7):856–866. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Brakel WH. Measuring health-related stigma--a literature review. Psychol Health Med. 2006;11(3):307–334. doi: 10.1080/13548500600595160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Rie A, Sengupta S, Pungrassami P, Balthip Q, Choonuan S, Kasetjaroen Y, … Chongsuvivatwong V. Measuring stigma associated with tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS in southern Thailand: exploratory and confirmatory factor analyses of two new scales. Trop Med Int Health. 2008;13(1):21–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2007.01971.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson AC, Corrigan P, Larson JE, Sells M. Self-stigma in people with mental illness. Schizophr Bull. 2007;33(6):1312–1318. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbl076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weiss MG, Ramakrishna J. Stigma interventions and research for international health. Lancet. 2006;367(9509):536–538. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(06)68189-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing: A tool for improving questionnaire design. Thousand Oaks, Calif: Sage Publications; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization End TB Strategy. Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/EB134/B134_12-en.pdf?ua=1.

- World Health Organization Global Tuberculosis Report. 2015 Retrieved from http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/191102/1/9789241565059_eng.pdf?ua=1.

- Wynne A, Richter S, Jhangri GS, Alibhai A, Rubaale T, Kipp W. Tuberculosis and human immunodeficiency virus: exploring stigma in a community in western Uganda. AIDS Care. 2014 doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.882488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.