Abstract

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD) is a lethal muscle wasting disease caused by a lack of dystrophin, which eventually leads to apoptosis of muscle cells and impaired muscle contractility. Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats/ CRISPR associated protein 9 (CRISPR/Cas9) gene editing of induced pluripotent stem cells (IPSC) offers the potential to correct the DMD gene defect and create healthy IPSC for autologous cell transplantation without causing immune activation. However, IPSC carry a risk of tumor formation, which can potentially be mitigated by differentiation of IPSC into myogenic progenitor cells (MPC). We hypothesize that precise genetic editing in IPSC using CRISPR-Cas9 technology, coupled with MPC differentiation and autologous transplantation, can lead to safe and effective muscle repair. With future research, our hypothesis may provide an optimal autologous stem cell-based approach to treat the dystrophic pathology and improve the quality of life for patients with DMD.

Keywords: CRISPR-Cas9, Precise correction, DMD, myogenic progenitor cells, myogenesis

Introduction

Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy (DMD) is a genetic disorder which is characterized by the absence of dystrophin, a cytoskeletal structural protein. This disease predominately affects males, as the mutations in the gene which cause this condition are located on the X chromosome [1–3]. Most patients are diagnosed between the ages of 2 and 5, ambulation is commonly lost in the teen years, and death is usually caused by cardiac or respiratory failure in the third decade [4]. Lacking the dystrophin protein is problematic for a number of reasons, the most obvious being dystrophin’s role in muscle stabilization. Dystrophin is responsible for protecting the muscle sarcolemma from contraction-induced damages. Without it, the dystroglycan complex, which resides at the cellular surface, is not able to join with the cytoskeleton of myocytes. This inability to link the dystroglycan complex and the cytoskeleton leads to muscular destabilization, and eventually weakness and myopathy [1, 5].

In the early stages of DMD, the damage caused by the absence of dystrophin is counteracted to a certain degree by stem cells in muscle which facilitate repair of the damaged tissue. However, as the disease progresses and the patient ages, this stem cell-mediated repair is insufficient, leading to recruitment of macrophages into the muscle, inflammation, and fibro-fatty replacement of muscle fibers [6–8]. The associated muscle wasting poses major therapeutic challenges, as delivering therapeutic agents into fibrotic, inflamed tissues is difficult and considered a large obstacle in developing curative treatments for DMD [8].

The DMD gene is one of the largest in the human genome, consisting of 79 exons, and one of the more commonly mutated genes [9]. DMD can be caused by in-frame, out-of-frame, and frameshift mutations, with frameshift being the most common. Each of these mutations results in the deletion of exons in the DMD gene, which either generates a premature stop codon or disrupts the reading frame [10–12]. Approximately 60% of these mutations occur between exons 45–55 of the DMD gene, making this section of the gene an ideal target for gene therapy [12, 13]. In-frame deletions between exons 45–55 typically trigger a milder form of dystrophy known as Becker Muscular Dystrophy, which allows patients to live much longer, less affected lives [12]. In-frame deletions between exons 45–46 can result in severe DMD; however these mutations are uncommon [14]. Intragenic mutations affecting more than one exon are typical in at least 60% of DMD patients [15].

Hypothesis

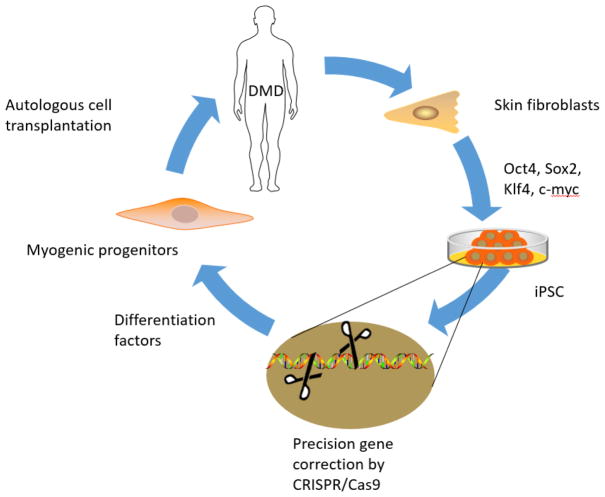

Using autologous iPSC-derived myogenic progenitor cells, in which the dystrophin gene is precisely corrected by CRISPR/Cas9 technology, will efficiently and safely regenerate muscles in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Schematic of repairing muscular dystrophy by combination of autologous iPSC-derived myogenic progenitor cell transplantation with CRISPR/Cas9-mediated precise gene correction.

Basis for Hypothesis

As mentioned above, DMD is a genetic disorder involving the mutation of one or more exons in the DMD gene The use of IPSCs edited by CRISPR/Cas9 technology has been found to be an appropriate and effective method for gene editing [1]. Long et al., reported use of CRISPR/Cas9 technology in vivo led to the repair of damaged muscular tissue and elimination of potential future consequences [1]. The use of autologous IPSCs is an attractive option considering the potentially unlimited availability of these cells [9]. Li HL et. al, reported some success correcting dystrophin gene in DMD patients derived iPSC by CRISPR-Cas9, and can detect full-length dystrophin protein after differentiating iPSC to skeletal muscle cells [16]. Young et al. have conducted imprecise use of CRISPR/Cas9 in the treatment of DMD, in which one single pair of guide RNAs can restore dystrophin expression in 60% of DMD patients[17] [12].

Current therapies to treat DMD

The current approach to DMD involves a combination of glucocorticoids and physical/occupational therapy to maintain strength and flexibility for as long as possible. While these treatments are quite effective at improving symptoms, a large number of undesirable side effects are associated with the chronic use of glucocorticoids [18, 19]. Many alternative remedies have been proposed, both to manage and potentially cure the disease. These alternatives include, but are not limited to gene replacement therapies; manipulation of inflammatory cascades; compensatory protein expression; collagen producing cells; activation/inhibition of key growth factors; and manipulation of mRNAs [8, 19–21]. The most prevalent method currently under investigation is gene editing therapy.

The majority of treatments aimed at managing symptoms and improving quality of life target the chronic inflammation which is a major causative factor for DMD complications. The IL-1β pathway is thought to be the initiator of muscular degradation in DMD. As such, a variety of therapies have been developed to target this pathway [22]. The two most commonly used steroids to reduce inflammation in DMD patients are deflazacort and prednisone; both medications are used chronically and carry a substantial number of side effects. The most common effects are weight gain, stunted growth, and increased risk of respiratory infection, with the latter being the most serious. One study found deflazacort to be the safer than prednisone [23].

Treatment with taurine has recently been shown to be effective in a mouse model of DMD; the therapy prevented both necrosis and inflammation in juvenile mice [7]. Inhibition of PKCθ inhibits both inflammation and muscle atrophy through modulation of immune cell responses. Pharmacological intervention with C20, a PKCθ inhibitor, has proven efficacious at reducing contraction-based injuries and increasing muscular function [19]. Another common target for anti-inflammatory medications is the transcription factor NF-kβ. Flavocoxid, which targets NF-kβ, is currently undergoing testing in phase 1 clinical trials [24].

Follistatin, a therapy developed for management of symptoms rather than to provide curative treatment, activates the Akt/mTOR/S6K signaling pathway, leading to an increase in strength and muscular mass [25]. Follistatin has proven effective in increasing distance in the 6-minute walk test of patients suffering from Becker muscular dystrophy; it is currently under clinical trial for use with DMD patients as well [26, 27]. Resveratrol, a natural compound which induces antioxidant effects, decreases oxidative damage and reduces fibrosis and was found to have cardioprotective functions in mouse models [28]. Another drug that targets fibrosis and oxidative stress is idebenone, which has shown efficacy in DMD[29]. Therapies targeting fibrosis are by no means limited to the previously mentioned drugs; crenolanib, simvastatin, flavocoid, and others not listed here have also been tested experimentally. Most of these agents have antioxidant properties, and nearly all target the TGF-β pathway [8, 30–32].

Drugs such as eteplirsen and ataluren are undergoing various phases of clinical trials; they have been designed to skip exon 51 and disrupt premature nonsense mutations, respectively [9]. Eteplirsen was found to increase dystrophin expression in muscle fibers by 23% compared to the control groups, and it is currently undergoing FDA review [33]. One major downfall of eteplirsen, however, is the cost, which is estimated at $300,000–$400,000 per year [34]. The administration of tricyclo-DNA oligomers, a novel approach to correcting the gene defect, favorably impacted dystrophin protein expression and function in both skeletal and cardiac muscle in a mouse model [35].

As mentioned previously, gene editing is currently a ‘hot topic’ in the development of curative treatments for DMD. There are two major schools of thought regarding gene editing: the first of which is referred to as ‘exon skipping’. This technique essentially takes a DMD phenotype and transforms it into the less severe Becker Muscular Dystrophy phenotype, which carries a higher quality of life and a much longer life expectancy (death is common in the sixth decade of life, as opposed to the third which is typical with DMD) [36]. Through the use of synthetic antisense oligonucleotide sequences, exon skipping is induced during the splicing step of pre-messenger RNA biosynthesis; this leads to the formation of a partially restored reading frame and a truncated version of the dystrophin protein [6]. Exon skipping ascribes to the notion that a truncated version of dystrophin, which can be produced relatively simply when only one or two exons in the gene are mutated, is preferable to a total lack of dystrophin. This is both logical and obvious; however, many issues remain in the generation of templates which are capable of skipping multiple exons while avoiding off-target effects. More than 80% of DMD mutations could potentially be corrected through the skipping of one or two exons, and it has been estimated that a mere 30% production of dystrophin could prevent muscle degeneration [37, 38]. Nevertheless, the major downside to exon skipping is the need to personalize each template to the specific exon(s) in which mutations have occurred [39].

The second most common form of gene editing is whole-gene editing through use of the CRISPR/Cas9 system. This technique permanently changes the genomic makeup of cells, providing long-term restoration of the dystrophin protein [39]. A variety of transport options exist to deliver the CRISPR/Cas9 system into cells, one of the most popular of which is the use of adeno-associated viral vectors (AAV). AAVs are versatile and can be delivered to the patient via several approaches. Methods such as intramuscular injections, intraperitoneal injections, and retro-orbital injections have all been implemented with varying success [5, 40, 41]. AAV-mediated editing appears to be one of the most successful therapeutic approaches currently being tested for DMD, as it has been found by multiple researchers to successfully restore reading frames and dystrophin expression in mouse models [5].

Evaluation of Hypothesis

The use of autologous IPSCs was previously shown to restore muscular function, repair damage, and prevent further complications in DMD [1, 12]. The use of CRISPR/Cas9 is superior to other gene editing technologies such as exon skipping for several reasons. First, the CRISPR/Cas9 system allows for full exonal correction as opposed to a ‘skipping’ of exons, resulting in the production of a full-length dystrophin protein as opposed to a truncated form produced with exon skipping [12]. Second, Cas9 has the capability of producing multiple double-strand breaks in a single gene; this ‘multiplexing’ is more efficacious in the treatment of DMD.

To test the efficacy of IPSC-derived myogenic progenitors in the treatment and correction of the DMD phenotype, we will first take skin fibroblast cells and revert them to a pluripotent state. Once the cells have been reverted to an IPSC state, we will transfect them with the genomic correction and a GFP tag using CRISPR/Cas9 technology, and differentiate them into myogenic precursors. After the cells have been differentiated, genotyping will be conducted on cloned duplicates, which will allow us to identify the correctly edited cells. Once identified, these cells will be amplified, followed by subsequent transplantation into the muscles of an mdx mouse model.

Once we have established the efficacy of this technique using a mouse model, we will repeat the experimentation using human IPSC-derived myogenic precursors. To test the functional merit of this hypothesis, we will monitor the strength of the animals using a grip strength test throughout the duration of the experiment. In addition, we will assess the rate of stem cell integration and transplantation by performing immunohistochemistry and imaging of myocytes to identify the GFP-tagged cells. In conclusion, the combination of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing and autologous iPSC-derived myogenic precursors provides an ideal method and delivery system to restore the reading frame of the full-length dystrophin protein. This novel use of myogenic precursors as opposed to IPSCs will decrease chances of tumorigenesis and allow for stronger integration of corrected cells into muscle.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Support/funding: This work was supported by the American Heart Association Grant-in-Aid 16GRNT31430008 (to Y.T.); NIH grant AR070029 (to Y.T./M. A./N. L. W.), and NIH grants 2RHL086555 (to Y.T.) and HL134354 (to Y.T./M.A./N.L.W.), and NIH grant R01 HL124251 (IM. K).

Footnotes

Supplemental Data: None

Conflicts of interest: None to disclose.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Long C, et al. Prevention of muscular dystrophy in mice by CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of germline DNA. Science. 2014;345(6201):1184–1188. doi: 10.1126/science.1254445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mendell JR, et al. Evidence-based path to newborn screening for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2012;71(3):304–13. doi: 10.1002/ana.23528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Romitti PA, et al. Prevalence of Duchenne and Becker muscular dystrophies in the United States. Pediatrics. 2015;135(3):513–21. doi: 10.1542/peds.2014-2044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Winterholler M, et al. Stroke in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: A Retrospective Longitudinal Study in 54 Patients. Stroke. 2016;47(8):2123–6. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.116.013678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Long C, et al. Postnatal genome editing partially restores dystrophin expression in a mouse model of muscular dystrophy. Science. 2016;351(6271):400–3. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5725. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hammers DW, et al. Disease-modifying effects of orally bioavailable NF-kappaB inhibitors in dystrophin-deficient muscle. JCI Insight. 2016;1(21):e90341. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.90341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Terrill JRP, Grounds MD, Arthur PG. Increased taurine in pre-weaned juvenile mdx mice greatly reduces the acute onset of myofibre necrosis and dystropathology and prevents inflammation. PLoS Curr. 2016;8 doi: 10.1371/currents.md.77be6ec30e8caf19529a00417614a072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ieronimakis N, et al. PDGFRalpha signalling promotes fibrogenic responses in collagen-producing cells in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Pathol. 2016;240(4):410–424. doi: 10.1002/path.4801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mah JK. Current and emerging treatment strategies for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2016;12:1795–807. doi: 10.2147/NDT.S93873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lapidos KA, Kakkar R, McNally EM. The dystrophin glycoprotein complex: signaling strength and integrity for the sarcolemma. Circ Res. 2004;94(8):1023–31. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000126574.61061.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ousterout DG, et al. Multiplex CRISPR/Cas9-based genome editing for correction of dystrophin mutations that cause Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6244. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Young CS, et al. A Single CRISPR-Cas9 Deletion Strategy that Targets the Majority of DMD Patients Restores Dystrophin Function in hiPSC-Derived Muscle Cells. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18(4):533–40. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.01.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bengtsson NE, et al. Muscle-specific CRISPR/Cas9 dystrophin gene editing ameliorates pathophysiology in a mouse model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Commun. 2017;8:14454. doi: 10.1038/ncomms14454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Findlay AR, et al. Clinical phenotypes as predictors of the outcome of skipping around DMD exon 45. Ann Neurol. 2015;77(4):668–74. doi: 10.1002/ana.24365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bladen CL, et al. The TREAT-NMD DMD Global Database: analysis of more than 7,000 Duchenne muscular dystrophy mutations. Hum Mutat. 2015;36(4):395–402. doi: 10.1002/humu.22758. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li HL, et al. Precise correction of the dystrophin gene in duchenne muscular dystrophy patient induced pluripotent stem cells by TALEN and CRISPR-Cas9. Stem Cell Reports. 2015;4(1):143–54. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2014.10.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Breitbart A, Murry CE. Imprecision Medicine: A One-Size-Fits-Many Approach for Muscle Dystrophy. Cell Stem Cell. 2016;18(4):423–4. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2016.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lamb MM, et al. Corticosteroid Treatment and Growth Patterns in Ambulatory Males with Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. J Pediatr. 2016;173:207–213 e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.02.067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Marrocco V, et al. Pharmacological Inhibition of PKCtheta Counteracts Muscle Disease in a Mouse Model of Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. EBioMedicine. 2017;16:150–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Puolakkainen T, et al. Treatment with soluble activin type IIB-receptor improves bone mass and strength in a mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2017;18(1):20. doi: 10.1186/s12891-016-1366-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shang YC, et al. Activation of Wnt3a signaling promotes myogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in mdx mice. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2016;37(7):873–81. doi: 10.1038/aps.2016.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Benny Klimek ME, et al. Effect of the IL-1 Receptor Antagonist Kineret(R) on Disease Phenotype in mdx Mice. PLoS One. 2016;11(5):e0155944. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0155944. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Griggs RC, et al. Efficacy and safety of deflazacort vs prednisone and placebo for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurology. 2016;87(20):2123–2131. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000003217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Miyatake S, et al. Anti-inflammatory drugs for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: focus on skeletal muscle-releasing factors. Drug Des Devel Ther. 2016;10:2745–58. doi: 10.2147/DDDT.S110163. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Winbanks CE, et al. Follistatin-mediated skeletal muscle hypertrophy is regulated by Smad3 and mTOR independently of myostatin. J Cell Biol. 2012;197(7):997–1008. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201109091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Minetti GC, et al. Functional and morphological recovery of dystrophic muscles in mice treated with deacetylase inhibitors. Nat Med. 2006;12(10):1147–50. doi: 10.1038/nm1479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mendell JR, et al. A phase 1/2a follistatin gene therapy trial for becker muscular dystrophy. Mol Ther. 2015;23(1):192–201. doi: 10.1038/mt.2014.200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hori YS, et al. Resveratrol ameliorates muscular pathology in the dystrophic mdx mouse, a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2011;338(3):784–94. doi: 10.1124/jpet.111.183210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McDonald CM, et al. Idebenone reduces respiratory complications in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2016;26(8):473–80. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Buyse GM, et al. Efficacy of idebenone on respiratory function in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy not using glucocorticoids (DELOS): a double-blind randomised placebo-controlled phase 3 trial. Lancet. 2015;385(9979):1748–57. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)60025-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDonald CM, et al. Idebenone reduces respiratory complications in patients with Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neuromuscul Disord. 2016;26(8):473–80. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2016.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Whitehead NP, et al. Simvastatin offers new prospects for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Rare Dis. 2016;4(1):e1156286. doi: 10.1080/21675511.2016.1156286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mendell JR, et al. Eteplirsen for the treatment of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Ann Neurol. 2013;74(5):637–47. doi: 10.1002/ana.23982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Aartsma-Rus A, Krieg AM. FDA Approves Eteplirsen for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: The Next Chapter in the Eteplirsen Saga. Nucleic Acid Ther. 2017;27(1):1–3. doi: 10.1089/nat.2016.0657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Goyenvalle A, et al. Functional correction in mouse models of muscular dystrophy using exon-skipping tricyclo-DNA oligomers. Nat Med. 2015;21(3):270–5. doi: 10.1038/nm.3765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Helderman-van den Enden AT, et al. Becker muscular dystrophy patients with deletions around exon 51; a promising outlook for exon skipping therapy in Duchenne patients. Neuromuscul Disord. 2010;20(4):251–4. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neri M, et al. Dystrophin levels as low as 30% are sufficient to avoid muscular dystrophy in the human. Neuromuscul Disord. 2007;17(11–12):913–8. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Serena E, et al. Skeletal Muscle Differentiation on a Chip Shows Human Donor Mesoangioblasts’ Efficiency in Restoring Dystrophin in a Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Model. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2016;5(12):1676–1683. doi: 10.5966/sctm.2015-0053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Xu L, et al. CRISPR-mediated Genome Editing Restores Dystrophin Expression and Function in mdx Mice. Mol Ther. 2016;24(3):564–9. doi: 10.1038/mt.2015.192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rodino-Klapac LR, et al. Persistent expression of FLAG-tagged micro dystrophin in nonhuman primates following intramuscular and vascular delivery. Mol Ther. 2010;18(1):109–17. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tabebordbar M, et al. In vivo gene editing in dystrophic mouse muscle and muscle stem cells. Science. 2016;351(6271):407–411. doi: 10.1126/science.aad5177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.