Abstract

Purpose:

Approaching death seems to be associated with physiological/spiritual changes. Trajectories including the physical–psychological–social–spiritual dimension have indicated a terminal drop. Existential suffering or deathbed visions describe complex phenomena. However, interrelationships between different constituent factors (e.g., fear and pain, spiritual experiences and altered consciousness) are largely unknown. We lack deeper understanding of patients’ inner processes to which care should respond. In this study, we hypothesized that fear/pain/denial would happen simultaneously and be associated with a transformation of perception from ego-based (pre-transition) to ego-distant perception/consciousness (post-transition) and that spiritual (transcendental) experiences would primarily occur in periods of calmness and post-transition. Parameters for observing transformation of perception (pre-transition, transition itself, and post-transition) were patients’ altered awareness of time/space/body and patients’ altered social connectedness.

Method:

Two interdisciplinary teams observed 80 dying patients with cancer in palliative units at 2 Swiss cantonal hospitals. We applied participant observation based on semistructured observation protocols, supplemented by the list of analgesic and psychotropic medication. Descriptive statistical analysis and Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) were combined. International interdisciplinary experts supported the analysis.

Results:

Most patients showed at least fear and pain once. Many seemed to have spiritual experiences and to undergo a transformation of perception only partly depending on medication. Line graphs representatively illustrate associations between fear/pain/denial/spiritual experiences and a transformation of perception. No trajectory displayed uninterrupted distress. Many patients seemed to die in peace. Previous near-death or spiritual/mystical experiences may facilitate the dying process.

Conclusion:

Approaching death seems not only characterized by periods of distress but even more by states beyond fear/pain/denial.

Keywords: end-of-life care, fears of death and dying, spirituality, near-death experiences, existential suffering, deathbed phenomena, states of consciousness, spiritual care

Introduction

End-of-life processes seem to be associated with essential physiological changes1,2 and spiritual transformations.3,4 Trajectories including the physical–psychological–social–spiritual dimension have indicated a “terminal drop”5–7—a sharp and abrupt physiological/psychological/spiritual deterioration. Nevertheless, we lack detailed information about shifting states of distress and peace. Complex phenomena are described as existential suffering,5–11 but interrelationships between constituent factors (e.g., fear and pain) are largely unknown. We lack deeper understanding of patients’ inner processes to which care should respond.3,5,7,12,13

Study results confirmed spirituality14 as helpful in dealing with distress and improving quality of life15–17 even amid severe illness.18 Single spiritual phenomena such as “spiritual distress” were identified.19–21 Deathbed phenomena were often associated with spiritual experiences and a peaceful death.22–30 However, we do neither know when nor why spirituality becomes fundamental during dying processes (immediately before death, amid calmness, or struggle) and if spiritual experiences are linked to religious beliefs.

Studies on near-death experiences (NDEs) have provided accounts of deep spiritual experiences.31–34 They alter attitudes to religion, to life, and decrease fear of death.34,35 But no studies dealt with impacts of previous NDEs on dying processes although described emotions, and visionary image sequences in NDEs may also emerge at the end of life.3,4,36,37 The authors’ preliminary study (Dying a Transition, N = 680) suggested that a transformation of perception involving an alteration in consciousness comparable to those in NDEs underlays the dying process.3,38 Patients lose their everyday consciousness and ego-related perception and enter into a completely new, ego-distant mode of perception, which seemed accompanied by less or no fear/struggle/denial and with changes in family relationships. The study listed 3 phenomenologically distinct stages: pre-transition, transition itself, and post-transition. In pre-transition, patients still had their everyday consciousness but were approaching death: Emotions, family processes, and maturation were intensified. In transition itself, even consciousness and perception was changing: Sensitivity, distress, and fear often culminated. In post-transition, perception was no longer bound to the ego, for example, patients signalized a state beyond time (timeless), beyond space (endless/nonlocal),32,33 or beyond our normal sense of gravity (out-of-body experience), and without ego-related emotions and impulses (e.g., needs, hunger, fear, and denial).3,38 These states may be comparable to prenatal, perinatal, and postnatal experiences39 but happen several times. However, the preliminary study did not include pain and was based on therapy records written by only one therapist/spiritual caregiver.

In this study, we refined our approach: Can the transformation of perception also be observed by an interdisciplinary palliative care team? How does this transformation coincide with distress (fear/pain/denial), peace (absence of fear/pain/denial), and spiritual experiences comprising experiences of transcendence? What do dying trajectories look like: When do fear/pain/denial and when do spiritual experiences erupt and subside? Are spiritual experiences associated with patients’ religious attitude? What is the impact of previous NDEs, previous spiritual and/or deep positive life experiences, and previous fear and coping patterns?

Methods

In this mixed-method exploratory observational study, 80 dying patients with cancer were observed by two nursing teams and at least one physician, psychotherapist, and spiritual caregiver in each team. Professionals had different religious/spiritual attitudes. The sample size corresponded to our former pilot study and to guidelines of Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA).38,40 In both centers, around half of all team members attended a 2-day voluntary workshop offered by a psychotherapist and a physician. Issues covered results of the previous study, interpretation of symbols in folktales/dreams and symbolic communication, discussions of practical case vignettes, and music-mediated relaxation to possibly enhance sensitivity to an altered awareness of time/space/body. The other professionals underwent a half-day training. All professionals could ask the psychotherapist for support at the deathbed. Then, they were introduced into method (participant observation) and tools.

We used a semistructured observation protocol (O-Protocol) designed by the core study team (psychotherapist, nurse, physician), reviewed for face and construct validity by several professionals of each team. It entailed fear, pain, denial, and spiritual experiences, quantified by a Likert-type scale (0-3). Additionally, the altered awareness of time/space/body and an altered social connectedness were used as parameters to identify patients who underwent a transformation of perception.3,32,41 Spatiotemporal body perception was confirmed by neuroscientific research as fundamentally linked to self-consciousness.41,42 Both parameters were differentiated into items designating pre-transition, transition itself, and post-transition. A supplementary semistructured questionnaire applied in routine care for each admitted patient addressed religious affiliation, spiritual attitudes/practices,43 fear of death and symptom distress, coping patterns, previous NDE,31,33 previous spiritual experiences, and positive life experiences. Both tools provided enough space to note patients’ verbal hints (e.g., “green meadow”). After approval by the two hospital ethics committees, a database was set up.

Inclusion and observation began when patients were diagnosed by the treating physician as dying within 3 days up to 1 or 2 weeks (no specific prognostication tool applied). Excluded were patients unable to answer the questions during the routine admission conversation, patients with psychosis and dementia, and patients who died within 2 days after starting observation or left the hospital during data collection. Patients were observed daily: At midday shift change, two care professionals independently recorded their observations of the same patient situation. After each marked change in patients’ conditions, professionals additionally conducted observations up to 8 times per day. Professionals were encouraged to ask mutually complementary questions to allow patients reacting to one question or the other. Concerning spiritual experiences, they had to focus on obvious signals (e.g., verbal hints about angels). After observation, professionals filled out the O-Protocol. In informal round table sessions, the interdisciplinary team reflected topics from the O-Protocol, but no adaptations of the procedures were made. After death, the data were anonymized and entered into the database. From the medical chart, the list of analgesic and psychotropic drugs was added.

Analysis

Descriptive statistical method was combined with IPA.40 Two researchers with a different professional background (psychotherapist and nurse) analyzed the data and consulted in case of doubt a third person (physician). An international panel (co-authors and experts in philosophy, theology, and NDE) discussed the analysis plan, preliminary results, subgroups, and open questions. Then, the core study team conducted the analysis.

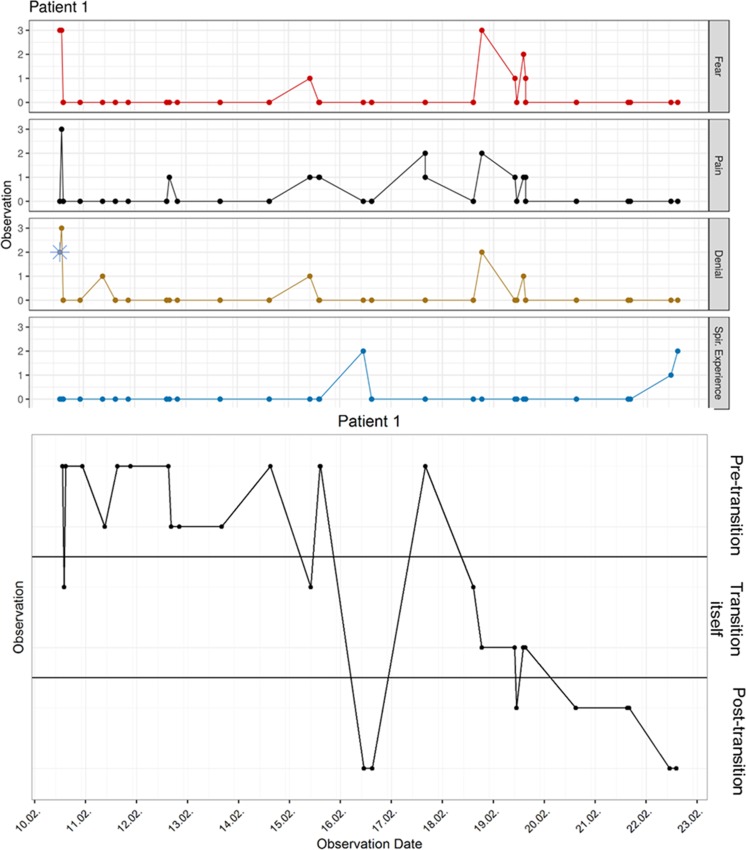

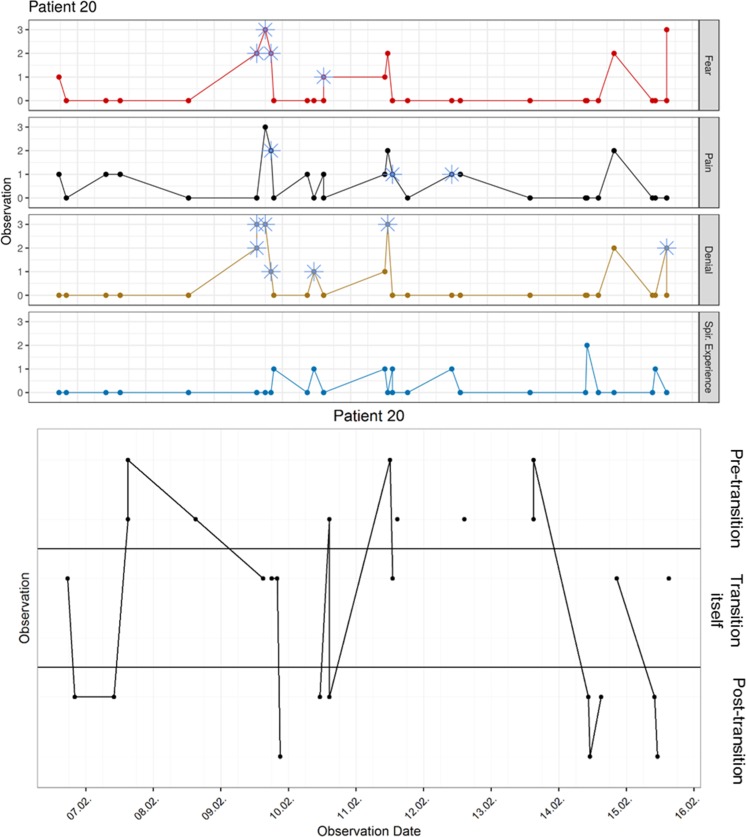

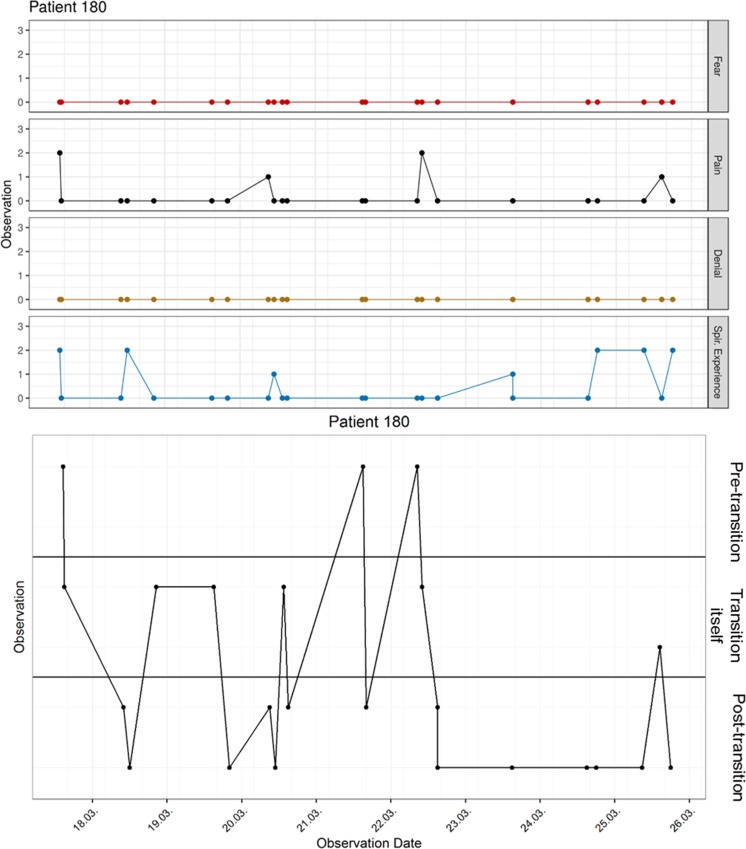

First, the observation data were visualized in longitudinal graphs of dying trajectories (method: visual graphics, Figure 1: No 1; No 20; No 119; No 180). One graph illustrates fear/pain/denial, and spiritual experiences. The other graph shows the transitional stages identified by altered awareness of time/space/body and social connectedness. For clarifying these stages (because we also had O-Protocols where evaluation of the 2 parameters differed), we analyzed the additional comments of 100 such O-Protocols (total N = 2084). Then, we subsumed the combination “pre-transition/post-transition” (e.g., “he was totally awake but in a deep silence”) to pre-transition, “transition itself/pre-transition” (e.g., “she said ‘I’m falling’ but recognized me vaguely”) to transition itself, and “post-transition/transition itself” (e.g., “she stammered ‘flying’ but when addressed she seemed foggy-brained and far away”) to post-transition.

Figure 1.

Dying process of patient 1.

Dying process of patient 20.

Dying process of patient 119.

Dying process of patient 180.

Then, we asked about times of distress and peace and about associations with transitional stages (e.g., peace in post-transition). We particularly analyzed the predeath period: Was there peace and if so for how long? Finally, we discussed patients’ suffering based on graphs (duration and frequency of distress), on qualitative notes, and in case of doubt taking into account the medication. Medication was also studied whenever a graph showed an uninterrupted post-transitional stage for ≥6 hours. Questionnaire information allowed to differentiate sample subgroups and indicate facilitating/hindering factors.

Results

Of the 80 participants 40 were men and 40 women. The average age was 62 years (range 30-90 years). In all, 65 (81.3%) were Christian and 63 (78.8%) called themselves religious/spiritual (Table 1). Our study yielded 2084 O-Protocols in 2 years’ time (site 1: 1005; site 2: 1079). We had 526 double observations (n =1052; 50.5% O-Protocols).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Sample.

| Patients | N = 80 | Site 1 (N = 34; 42.5%) | Site 2 (N = 46; 57.5%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 40 | 50% | 21 | 61.8% | 19 | 41.3% |

| Female | 40 | 50% | 13 | 38.2% | 27 | 58.7% |

| Age | ||||||

| 30-50 | 10 | 12.5% | 2 | 5.9% | 8 | 17.4% |

| 51-70 | 34 | 42.5% | 13 | 38.2% | 21 | 45.7% |

| 71-90 | 36 | 45% | 18 | 52.9% | 18 | 39.1% |

| Religious tradition | ||||||

| Christian | ||||||

| Catholics | 39 | 48.8% | 14 | 41.2% | 25 | 54.3% |

| Protestant | 23 | 28.8% | 15 | 44.1% | 8 | 17.4% |

| Free (protestant) churches | 3 | 3.8% | 1 | 2.9% | 2 | 4.3% |

| No religious tradition | 12 | 15% | 4 | 11.8% | 8 | 17.4% |

| Other religious tradition | 3 | 3.8% | 1 | 2.9% | 2 | 4.3% |

| Religious/spiritual attitude | ||||||

| I am religious/spiritual | 63 | 78.8% | 29 | 85.3% | 34 | 73.9% |

| I like to pray | 36 | 45% | 18 | 52.9% | 18 | 39.1% |

| I like to meditate | 9 | 11.3% | 3 | 8.8% | 6 | 13% |

| Experiences and coping strategies | ||||||

| I had a near-death experience | 9 | 11.3% | 3 | 8.8% | 6 | 13% |

| I had a mystical/spiritual experience (including NDE) | 22 | 27.5% | 3 | 8.8% | 19 | 41.3% |

| Positive life experience as current source of support | 43 | 53.8% | 17 | 50% | 26 | 56.5% |

| I am evading issues of illness and dying (repression) | 25 | 31.3% | 8 | 23.5% | 17 | 37% |

| I am curious about afterlife | 19 | 23.8% | 5 | 14.7% | 14 | 30.4% |

| Fear at time of admission | ||||||

| Fear of symptom distress | 40 | 50% | 15 | 44.1% | 25 | 54.3% |

| Fear of uncertainty | 8 | 10% | 4 | 11.8% | 4 | 8.7% |

Abbreviation: NDE, near-death experience.

Fear/Pain/Denial/Spiritual Experiences

Most patients showed fear (75; 93.8%; 625 O-Protocols), pain (75; 93.8%; 706 O-Protocols), and spiritual experiences (72; 90%; 550 O-Protocols) at least once; 42 (52.5%) underwent denial (565 O-Protocols). Among patients with fear, 50 (62.5%) signalized fear also at time of admission, 25 (31.3%) did not. Among patients with spiritual experiences, 60 (75%) were Christians, 9 (11.3%) patients were without religious affiliation, 1 Buddhist, 1 Muslim, and 1 was adherent of natural religion (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2.

Themes: Fear, Pain, Denial, and Spiritual Experiences.

| Observation Protocols | N = 2084 | Site 1 (N = 1005) | Site 2 (N = 1079) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation of fear | 625 | 30% | 310 | 30.8% | 315 | 29.2% |

| Of pain | 706 | 33.9% | 355 | 35.3% | 351 | 32.5% |

| Of denial | 565 | 27.1% | 174 | 17.3% | 202 | 18.7% |

| Of spiritual experiences | 550 | 26.4% | 178 | 17.7% | 371 | 34.4% |

| Spir. experiences of darkness | 35 | 1.7% | 16 | 1.6% | 19 | 1.8% |

| Patients | N = 80 | Site 1 (N = 34) | Site 2 (N = 46) | |||

| Frequency of fear/pain/denial | ||||||

| Patients with fear | 75 | 93.8% | 34 | 100% | 41 | 89.1% |

| Patients with pain | 75 | 93.8% | 33 | 97.1% | 42 | 91.3% |

| Patients with denial | 42 | 52.5% | 30 | 88.2% | 43 | 93.5% |

| Patients with spiritual experiences (incl. exp. of darkness) | 72 | 90% | 30 | 88.2% | 42 | 91.3% |

| Spiritual experiences of darkness | 25 | 31.3% | 12 | 35.3% | 13 | 28.3% |

| Associations | ||||||

| Associations of fear/pain/denial (distress) | ||||||

| Clear association of all three themes | 35 | 43.8% | 13 | 38.2% | 22 | 47.8% |

| Partial association | 41 | 51.3% | 20 | 58.8% | 21 | 45.7% |

| No association | 4 | 5% | 1 | 2.9% | 3 | 6.5% |

| Associations of spiritual experiences and peace (no fear/pain/denial) | ||||||

| Coincident with periods of peace | 46 | 57.5% | 22 | 64.7% | 24 | 52.2% |

| After peaks of distress (fear/pain/denial) | 15 | 18.8% | 4 | 11.8% | 11 | 23.9% |

| Before peaks of distress | 5 | 6.3% | 3 | 8.8% | 2 | 4.3% |

| Sometimes before, sometimes after peaks of distress | 26 | 32.5% | 15 | 44.1% | 11 | 23.9% |

| Converse to peaks of distress | 3 | 3.8% | 2 | 5.9% | 1 | 2.2% |

| Sometimes coincident or converse to peaks of distress | 23 | 28.8% | 6 | 17.6% | 17 | 37% |

| No spiritual experience | 8 | 10% | 4 | 11.8% | 4 | 8.7% |

Table 3.

Religious Affiliation, Religious/Spiritual Attitude, and Spiritual Experience.

| With Spiritual Experience | With Spiritual Experience of Darkness | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 1 | Site 2 | Site 1 | Site 2 | ||||

| Patients | N = 80 | N = 34 | N = 46 | N = 72 | N = 30 | N = 42 | N = 25 | N = 12 | N = 13 |

| Religious affiliation | |||||||||

| Catholics | 39 (48.8%) | 14 (41.2%) | 25 (54.3%) | 37 (51.4%) | 12 (40%) | 25 (59.5%) | 13 (52%) | 5 (41.7%) | 8 (61.5%) |

| Protestants | 23 (28.8%) | 15 (44.1%) | 8 (17.4%) | 2 (2.8%) | 13 (43.3%) | 7 (16.7%) | 7 (28%) | 5 (41.7%) | 2 (15.4%) |

| Free churches | 3 (3.8%) | 1 (2.9%) | 2 (4.3%) | 3 (4.2%) | 1 (3.3%) | 2 (4.8%) | 3 (12%) | 1 (8.3%) | 2 (15.4%) |

| Buddhist | 1 (1.3%) | — | 1 (2.2%) | 1 (1.4%) | — | 1 (2.4%) | — | — | — |

| Muslim | 1 (1.3%) | 1 (2.9%) | — | 1 (1.4%) | 1 (3.3%) | — | — | — | — |

| Natural religion | 1 (1.3%) | — | 1 (2.2%) | 1 (1.4%) | — | 1 (2.4%) | — | — | — |

| No religious tradition | 12 (15%) | 3 (8.8%) | 9 (19.7%) | 9 (12.5%) | 3 (10%) | 6 (14.3%) | 2 (8%) | 1 (8.3%) | 1 (7.7%) |

| Religious/spiritual attitude | |||||||||

| I am religious/spiritual | 63 (78.8%) | 29 (85.3%) | 34 (73.9%) | 57 (79.2%) | 25 (83.3%) | 32 (76.2%) | 21 (84%) | 10 (83.3%) | 11 (84.6%) |

| I like to pray | 36 (45%) | 18 (52.9%) | 18 (39.1%) | 36 (50%) | 14 (46.7%) | 17 (40.5%) | 14 (56%) | 6 (50%) | 8 (61.5%) |

| I like to meditate | 9 (11.3%) | 3 (8.8%) | 6 (13%) | 9 (12.5% | 3 (10%) | 6 (14.3%) | 3 (12%) | — | 3 (23.1%) |

| I had a near-death experience | 9 (11.3%) | 3 (8.8%) | 6 (13%) | 9 (12.5%) | 3 (10%) | 6 (14.3%) | 3 (12%) | 1 (8.3%) | 2 (15.4%) |

| I had a spiritual experience (incl. NDE) | 22 (27.5%) | 6 (17.6%) | 16 (34.8%) | 22 (30.6%) | 6 (20%) | 16 (38.1%) | 6 (24%) | 2 (16.7%) | 4 (30.8%) |

| I am curious about afterlife | 19 (23.8%) | 5 (14.6%) | 14 (30.4%) | 18 (25%) | 5 (16.7%) | 13 (31%) | 7 (28%) | 2 (16.7%) | 5 (38.5%) |

Abbreviation: NDE, near-death experience.

Trajectories and associations between fear/pain/denial are illustrated in each line graph (Figure 1: No 1; No 20; No 119; No 180): 35 (43.8%) graphs showed clear associations, 41 (51.3%) partial, and 4 (5%) no associations. No trajectory displayed uninterrupted distress. Associations between peace and spiritual experience: 46 (57.5%) graphs illustrated clear, 23 (28.8%) partial, 3 (3.8%) no associations, and 8 (10%) showed no spiritual experiences.

Transformation of Perception

Most patients (69; 86.3%) seemed to undergo a transformation of perception with all 3 stages. Transition itself was observed in 76 (95%; 528 O-Procotols), as short incidence once or several times in 23 (28.8%) patients up to over 48 hours (1 patient). Post-transition was clearly observed (=in both parameters) in 75 (93.8%) patients (559 O-Protocols): as short incidence (19; 23.8%) up to over 48 hours (5; 6.3%). Post-transition was induced by medication in 5 (6.3%) patients; in an additional 7 (8.8%) patients, it was sometimes medication-induced and sometimes occurred naturally/spontaneously. In all, 128 (6.1%) O-Protocols were inconsistent (e.g., comprising all 3 stages because of invalid/missing data, displayed by interrupted lines, e.g., Figure 1: No 20; Table 4).

Table 4.

Stages of Transition: Frequency, Duration, and Association With Themes.

| Observation Protocols | N = 2084 | Site 1 (N = 1005) | Site 2 (N = 1079 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Observation of pre-transition | 869 | 41.7% | 431 | 42.9% | 438 | 40.6% |

| Of transition itself | 528 | 25.3% | 248 | 24.7% | 280 | 25.9% |

| Of post-transition | 559 | 26.8% | 246 | 24.5% | 313 | 29% |

| Inconsistent observations and missing data | 128 | 6.1% | 80 | 8% | 48 | 4.4% |

| Patients | N = 80 | N = 34 | N = 46 | |||

| Observation and duration of stages | ||||||

| All three transitional stages observed | 69a | 86.3% | 31 | 91.2% | 38 | 82.6% |

| Pre-transition/everyday consciousness | 78b | 97.5% | 34 | 100% | 44 | 95.7% |

| Transition itself | ||||||

| No transition itself observed | 4 | 5% | — | — | 4 | 8.7% |

| Several minutes | 23 | 28.8% | 10 | 29.4% | 13 | 28.3% |

| Several minutes-6 hours | 23 | 28.8% | 13 | 38.2% | 10 | 21.7% |

| 6-12 hours | 8 | 10% | 2 | 5.9% | 6 | 13% |

| 12-24 hours | 16 | 20% | 6 | 17.6% | 10 | 21.7% |

| 24-48 hours | 5 | 6.3% | 3 | 8.8% | 2 | 4.3% |

| >48 hours | 1 | 1.3% | — | — | 1 | 2.2% |

| Post-transition | ||||||

| No post-transition observedc | 5 | 6.3% | 3 | 8.8% | 2 | 4.3% |

| Several minutes | 19 | 23.8% | 7 | 20.6% | 12 | 26.1% |

| Several minutes-6 hours | 14 | 17.5% | 4 | 11.8% | 10 | 21.7% |

| 6-12 hours | 8 | 10% | 2 | 5.9% | 6 | 13% |

| 12-24 hours | 14 | 17.5% | 6 | 17.6% | 8 | 17.4% |

| 24-48 hours | 15 | 18.8% | 9 | 26.5% | 6 | 13% |

| >48 hours | 5 | 6.3% | 3 | 8.8% | 2 | 4.3% |

| Medication and Post-transition Period ≥6 hours (N = 42; 52.5%) | ||||||

| Medication reduced | 17 | 21.3% | 10 | 29.4% | 7 | 15.2% |

| Medication (stable dose) | 9 | 11.3% | 2 | 5.9% | 7 | 15.2% |

| Medication may sometimes influence post-transition | 7 | 8.8% | 2 | 5.9% | 5 | 10.9% |

| No interpretation possible (lack of data) | 4 | 5% | 4 | 11.8% | 3 | 6.5% |

| Medication-induced post-transition | 5 | 6.3% | 2 | 5.9% | 3 | 6.5% |

| Associations of Themes and Stages: Graph 1. Fear, Pain, Denial, Spiritual Experience; Graph 2. Stages of Transition | ||||||

| Perfect association between themes and stagesd | 6 | 7.5% | 2 | 5.9% | 4 | 8.7% |

| Clear associatione | 34 | 42.5% | 18 | 52.9% | 16 | 34.8% |

| Sometimes associated, sometimes not associated | 21 | 26.3% | 7 | 20.6% | 14 | 30.4% |

| Sometimes associated or no interpretation possible | 16 | 20% | 6 | 17.6% | 10 | 21.7% |

| No association | 3 | 3.8% | 1 | 2.9% | 2 | 4.3% |

aFive without clear post-transition, 4 without transition itself, and 2 without pre-transition (seeb).

bTwo were in pre-transition at time of admission but not at any time afterwards (during observations).

cIn these cases there was either no post-transition observed or not in both parameters (altered awareness of time/space/body; altered social connectedness). For interpretation, the medication list was additionally consulted.

dPerfect association: In every observation distress (fear/pain/denial) happened either in pre-transition or especially in transition itself, peace in pre-transition or in post-transition. No distress in post-transition. No peace in transition itself. No spiritual experiences in transition itself.

eClear association: In most instances the graph displayed associations (described under d) (e.g., Figure 1: No 1).

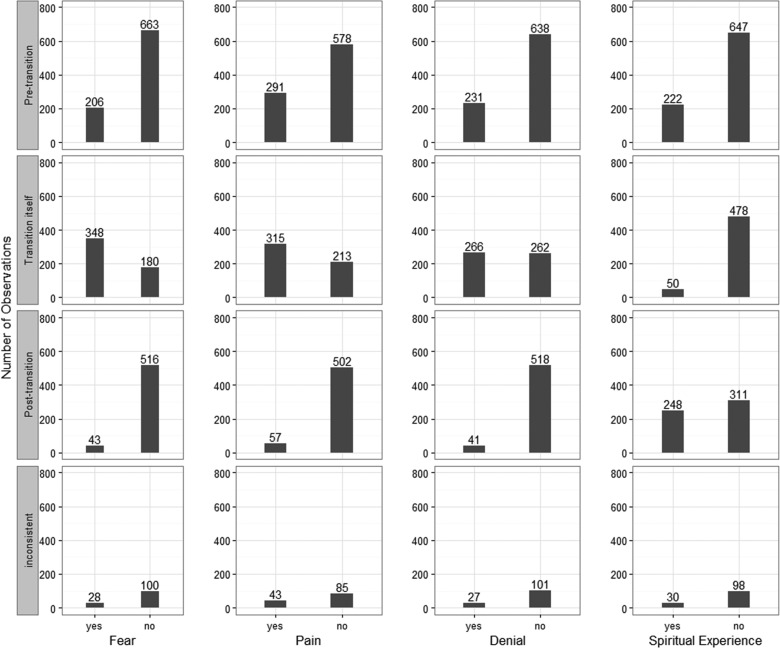

Associations Between Erupting/Subsiding Distress and Transformation of Perception (Comparison of Both Graphs)

In 6 (7.5%) patients, associations were perfect and in 34 (42.5%) clearly visible (e.g., Figure 1: No 1). Transition itself seemed to be related to distress (Figure 2): Out of 528 O-Protocols stating transition itself, 348 (65.9%) indicated fear. Vice versa, of 625 O-Protocols indicating fear, 348 (65.9%) documented transition itself. Pre-transition and in particular post-transition showed associations with peace and spiritual experiences (Figure 2): For example, of 559 O-Protocols stating post-transition, 516 (92.3%) indicated no fear, and 248 (44.4%) reported spiritual experiences.

Figure 2.

Ratings of fear, pain, denial, and spiritual experiences in stages of transition.

Interpretation of Suffering, of Peaceful Death and Facilitating/Hindering Factors

Many patients (20; 25%) died in/after 1 to 5 days of peace and 22 (27.5%) after 6 to 24 hours of peace. In all, 14 (17.5%) died amid distress; nevertheless, 8 of them had long periods of peace before (Figure 1: No 20). At the last observation, 65 (81.3%) patients were in post-transition and 9 (11.3%) in transition itself. Interpretation of suffering ranges from “no/almost no suffering” (10; 12.5%), “mild suffering” (39; 48.8%), “moderate suffering” (11; 13.8%), periods of much suffering along with calm periods (16; 20%; Figure 1: No 20; No 119) to “much suffering” (4; 5%). No patient suffered moderately or severely for longer than 2 days. (Table 5; Figure 3)

Table 5.

Interpretation of Suffering and Peace of Death.

| Patients | N = 80 | Site 1 (N = 34) | Site 2 (N = 46) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Suffering during dying trajectory | ||||||

| No/almost no suffering | 10 | 12.5% | 1 | 2.9% | 9 | 19.6% |

| Mild suffering (degree 1 or few, short peaks) | 39 | 48.8% | 20 | 58.8% | 19 | 41.3% |

| Moderate suffering (degree 2, not often, not very long) | 11 | 13.8% | 4 | 11.8% | 7 | 15.2% |

| Much suffering, much calmness (degree 3, peaceful periods) | 16 | 20% | 8 | 23.5% | 8 | 17.4% |

| Much suffering (degree 3) | 4 | 5% | 1 | 2.9% | 3 | 6.5% |

| Suffering at last observation before death | ||||||

| Distress in patients (at last observation) | 14 | 17.5% | 4 | 11.8% | 10 | 21.7% |

| Fear | 13 | 16.3% | 4 | 11.8% | 9 | 19.6% |

| Pain | 11 | 13.8% | 3 | 8.8% | 8 | 17.4% |

| Denial | 6 | 7.5% | 1 | 2.9% | 5 | 10.9% |

| Peace in patients (at last observation) | 66 | 82.5% | 30 | 88.2% | 36 | 78.3% |

| With spiritual experiences | 36a | 45% | 13 | 38.2% | 23 | 50% |

| Without spiritual experiences | 30 | 37.5% | 17 | 50% | 13 | 28.3% |

| Stages of transition (at last observation) | ||||||

| Patients in pre-transition | 5 | 6.3% | 3 | 8.8% | 2 | 4.3% |

| Transition itself | 8 | 11.3% | 1 | 2.9% | 7 | 15.2% |

| Post-transition | 65 | 81.3% | 28 | 82.4% | 37 | 80.4% |

| Indistinct stage/missing data | 2 | 2.5% | 2 | 5.9% | - | - |

| Dies after period of peace/distress | ||||||

| Dies peacefully after 1-5 days of calmness | 20 | 25% | 10 | 29.4% | 10 | 21.7% |

| Dies peacefully after 6-24 hours of calmness | 22 | 27.5% | 11 | 32.4% | 11 | 23.9% |

| Dies peacefully after short distress | 24 | 30% | 9 | 26.5% | 15 | 32.6% |

| Dies in short mild distress | 4 | 5% | 1 | 2.9% | 3 | 6.5% |

| Dies in short distress | 10 | 12.5% | 3 | 8.8% | 7 | 15.2% |

aTwo (4.3%) patients at site 2 had spiritual experiences and distress at the last observation.

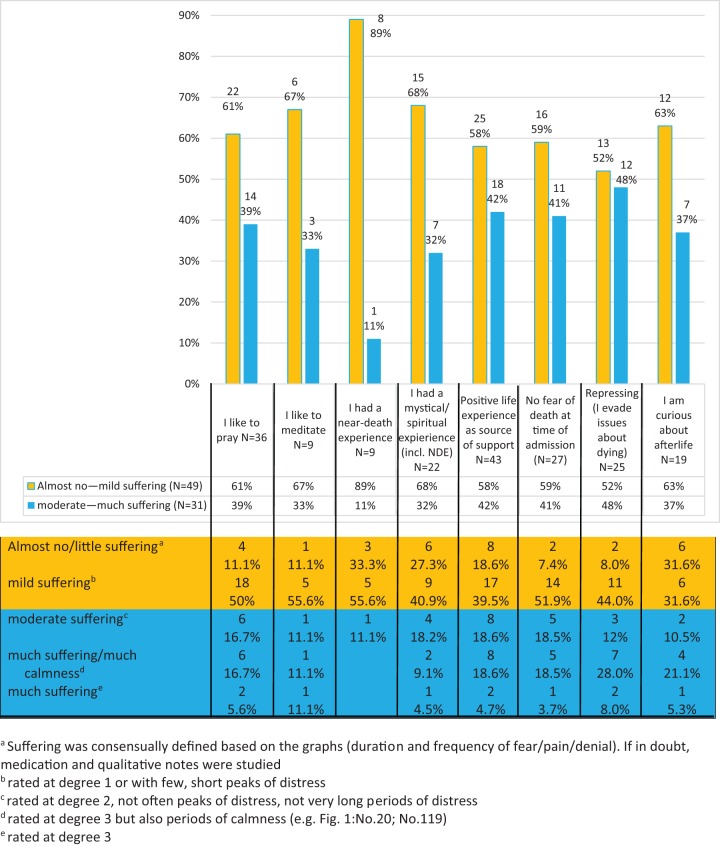

Figure 3.

Suffering and facilitating/hindering factors.

Among patients with “no/almost no” or “mild suffering” (49; 61.3%) were many with previous NDEs or spiritual/mystical experiences. Three out of 9 patients with a previous NDE had “no/almost no suffering” (Figure 1: No 180). Concerning attitudes, coping strategies, and spiritual practices—particularly “curiosity about afterlife”—had a positive, repressing almost no impact.

Discussion

In dying processes, fear/pain/denial seem to be highly associated (peaks of concurrence) but not lasting: Without exception, distress was followed by periods/incidences of observed peace. Observed calmness can last for days (Figure 1: No 1; No 119; No 180). Although pain was reported in other studies to be prevalent at the end of life in 66.4%44 and 70% to 90%45 of patients with cancer, our graphs modify the notion of a “terminal drop” phenomenon5–7 and of increasing suffering before death.

The transformation of perception happened more frequently than our previous studies suggested, probably because observations by many observers increase the observation per patient ratio. The two parameters (altered social connectedness and altered awareness of time/space/body) were appropriate to assess patients’ state of consciousness: As expected, in transition itself fear/pain/denial frequently cumulated. Post-transition was often observed as state without/“beyond” fear/pain/denial. The transformation of perception may provide an explanation for erupting and subsiding fear/pain/denial as well as for the frequency of spiritual experiences. Even if the number of patients without spiritual experiences (8; 10%) might be slightly higher, adding 4 (5%) patients who had only one or two spiritual experience rated at degree 1, this finding is consistent with recent studies. They reported end-of-life dreams/visions in 82.5% of participants.28 Deathbed visions occurred in 21%26 to 95%23 of patients. In contrast to existing literature which sees the apparition of deceased relatives/friends as overarching spiritual theme, we registered 31 visions/experiences of light and 21 visions of angels (among them some appearances of deceased relatives).23–30,36 Japanese patients with cancer were also reported as experiencing visions of light (7%),26 a phenomenon known from accounts of NDEs.33,34 Spiritual experiences happened in 46 (57.5%) patients as hypothesized in periods of peace and in post-transition (Figure 1: No 1) and slightly less in pre-transition. Unexpectedly, 41 (51.3%) patients had at least 1 spiritual experience followed by fear/pain/denial. Maybe the experience was too tremendous, maybe it was so beautiful that returning to everyday consciousness was hardly bearable.13

Spiritual experiences at the last observation before death were seen in 38 (47.5%) patients, mostly combined with peace. Anyway, spiritual experiences were observed as highly effective. This corresponds to literature on end-of-life experiences, which suggest that spiritual experiences provide comfort.4,13,22–28 However, we had 35 (1.7%, N = 2084) experiences of darkness/ambivalence by 25 (31.3%) patients, comparable to earlier reports of 19%26 and 29%46 of patients with reactions of fear after deathbed visions. Nosek et al provided examples of distressing dreams reminiscent of past trauma or difficult situations.28 Fenwick and Brayne revealed that 9% of the dying were confused and 2% frightened and distressed by the experience.30 Spiritual experiences seem independent of patients’ previous religious affiliation13,29,46 but may be dependent on previous experiences: Among patients without any spiritual experiences were none who meditated or had a previous NDE or spiritual/mystical experiences (Table 3). It is notable that all three members of Free Churches also had spiritual experiences, including experiences of darkness and fear of a last judgment. All three called themselves “strict” adherents. This fact, in contrast to open-mindedness (curiosity of afterlife), may hinder dying processes.

Hindering and Facilitating Factors

Christians, adherents of other religions, and nonreligious patients had to endure suffering and death-related anxiety; this reportedly frequent challenge3,47,48 overwhelmed 75 (93.8%) patients, also 25 from a total of 27 who had no fear at time of admission. According to King et al, religious/spiritual attitudes do not predict later levels of anxiety or depression.49

However, deep positive experiences, previous NDEs, and mystical/spiritual experiences as well as open-mindedness (curiosity about afterlife) seemed to reduce suffering. As reported,30,36 patients with a belief in afterlife experienced comforting deathbed phenomena, although they may experience greater anxiety than those without this tenet of belief.50 The point may be that open-mindedness of believers supports dying: letting go and finding a new dimension.13,51 The importance of open-mindedness may also be inferred from a study about images of God in relation to coping strategies: Patients with an image of an unknown “hidden God” had a greater array of coping strategies (denial, seeking advice, and moral support) than patients who firmly believed that “God knows and understands them.”52 Open-mindedness includes the possibility of hope. On the other hand, to be convinced that one is abandoned by the divine may cause spiritual pain and aggravate physical suffering.16,20,21 Especially, the impact of previous NDEs on dying processes seems considerable: Only 1 of 9 patients suffered moderately, and 6 could better deal with pain (experienced pain without accompanying fear or denial, Figure 1: No 180). Even if 6 stated fear of death and symptom distress at time of admission, none feared the uncertainty.

In contrast, repressing did not affect the level of suffering: Sometimes it seemed to aggravate the process, sometimes it was helpful. Rousseau pointed out that denial as coping strategy may be beneficial and support patients in dealing with unfinished business but may also block a peaceful dying process.53 Other studies reported that patients who accepted their prognosis suffered less from severe anxiety and depressive symptoms.54,55 No fear of death seemed to be only slightly beneficial. It could indicate deep trust in 3 (11.1%) of 27 patients but also repression in 6 (22.2%). In all, dying processes remain unpredictable.

Limitations

Our data were limited to patients with cancer from Eastern Switzerland. Due to our homogeneous sample, we considered religious affiliation only in analyzing spiritual experiences (Table 3). Application of our findings to patients of other cultural background and diseases has to be done with caution.

Between observation times were unrecorded periods, despite 2 to 8 daily observations.

Observations were subjective evaluations and influenced by staff culture and interventions. However, the huge amount of prospective data (2084 O-Protocols), the fact of two sites, and of two independent observations (526 times, 1052 O-Protocols, 50.5%) offer reliability to the data set. The median of Cohen’s Kappa56 shows substantial agreement in interrater reliability ranging between 0.57 (altered awareness of time/space/body) and 0.71 (denial), 0.65 for spiritual experience, 0.66 for social connectedness, 0.67 for fear, and 0.68 for pain. Further, we marked positive reactions that were possibly influenced by care and therapeutical interventions with asterisks so that, for example, pain and pain relief fell visibly together (Figure 1: No 20).

The observation of spiritual experiences in particular could be biased by the attitude of the observer and may explain different results between the two sites (Table 2). However, double observations during mid-day shift (N = 526) showed little deviation (degree 1: for spiritual experience 14.3% of O-Protocols; for fear/pain/denial 10.8%).

Subgroups and interpretation of suffering were found only by consensus and not by predefined criteria. The assignment of the subgroup “pre-transition/post-transition” to pre-transition in particular has to be considered. However, required consensus by researchers of different professional background and many qualitative notes minimized researcher bias.

Periods of peace and post-transition may be medication-induced. These important objections can be refuted in many cases after careful study of medication (Table 4). The phenomenon seems to happen often naturally/spontaneously as part of the dying process.

Clinical Relevance

Results and line graphs can alleviate fear of a “terminal drop” (sharp and abrupt physiological/psychological/spiritual deterioration) in patients, relatives, and the public.

An understanding of transition3,38 and our findings combined with respect for every individual patient and process may improve care and instill confidence for recurrent states without/“beyond” fear/pain/denial.

Relatives can better understand the “remoteness” and signals of their loved ones.

The parameters (space/time/body awareness and social connectedness) for assessing transitional stages may be explored in further research. We noted high benefit for individual care interventions.

The concept of transition may help offer non-pharmocological support and an alternative to unspecific sedation for many patients.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the additional experts Dr med Pim van Lommel, Cardiologist, research in the field of near-death experiences, Prof Dr phil Ursula Renz, Professor in Philosophy at the University of Klagenfurt, Austria, and Prof Dr theol Roman Siebenrock, Professor of Dogmatic Theology at the University of Innsbruck, Austria for their analysis of the data and preliminary clusters. We would like to thank Dr sc nat Rafael Sauter, Biostatistician, for compiling the statistical report and Dr phil Daniel Niederer, MSc ETH for checking the study for its methodological rigor. Many thanks go to both multidisciplinary teams (palliative unit Munsterlingen, palliative unit St Gallen) for collecting data and for their open and critical collaboration.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests: The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- 1. Hui D, Dos Santos R, Chisholm G, Bansal S, Souza Crovador C, Bruera E. Bedside clinical signs associated with impending death in patients with advanced cancer: preliminary findings of a prospective, longitudinal cohort study. Cancer. 2015;121(6):960–967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Domeisen Benedetti F, Ostgathe C, Clark J, et al. International palliative care experts’ view on phenomena indicating the last hours and days of life. Support Care Cancer. 2013;21(6):1509–1517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Renz M. Dying: A Transition. New York, NY: Columbia University Press; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Arnold BL, Lloyd LS. Harnessing complex emergent metaphors for effective communication in palliative care: a multimodal perceptual analysis of hospice patients’ reports of transcendence experiences. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2014;31(3):292–299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Tang ST, Liu LN, Lin KC, et al. Trajectories of the multidimensional dying experience for terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2014;48(5):863–874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Giesinger JM, Wintner LM, Oberguggenberger AS, et al. Quality of life trajectory in patients with advanced cancer during the last year of life. J Palliat Med. 2011;14(8):904–912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Murray SA, Kendall M, Grant E, Boyd K, Barclay S, Sheikh A. Patterns of social, psychological, and spiritual decline toward the end of life in lung cancer and heart failure. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2007;34(4):393–402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Puchalski CM, Dorff RE, Hendi IY. Spirituality, religion, and healing in palliative care. Clin Geriatr Med. 2004;20(4):689–714, vi-vii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Jansen LA, Sulmasy DP. Sedation, alimentation, hydration, and equivocation: careful conversation about care at the end of life. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(11):845–849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jansen LA. Intractable end-of-life suffering and the ethics of palliative sedation: a commentary on Cassell and Rich. Pain Med. 2010;11(3):440–441; discussion 442. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ferrell B, Otis-Green S, Economou D. Spirituality in cancer care at the end of life. Cancer J. 2013;19(5):431–437 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lindqvist O, Tishelman C, Hagelin CL, et al. Complexity in non-pharmacological caregiving activities at the end of life: an international qualitative study. PLoS Med. 2012;9(2):e1001173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Renz M. Hope and Grace: Spiritual Experiences in Severe Distress, Illness and Dying. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley Publishers; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Puchalski C, Ferrell B, Virani R, et al. Improving the quality of spiritual care as a dimension of palliative care: the report of the Consensus Conference. J Palliat Med. 2009;12(10):885–904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. McClain CS, Rosenfeld B, Breitbart W. Effect of spiritual well-being on end-of-life despair in terminally-ill cancer patients. Lancet. 2003;361(9369):1603–1607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Balboni TA, Paulk ME, Balboni MJ, et al. Provision of spiritual care to patients with advanced cancer: associations with medical care and quality of life near death. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28(3):445–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Phelps AC, Lauderdale KE, Alcorn S, et al. Addressing spirituality within the care of patients at the end of life: perspectives of patients with advanced cancer, oncologists, and oncology nurses. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30(20):2538–2544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Renz M, Schuett Mao M, Omlin A, Bueche D, Cerny T, Strasser F. Spiritual experiences of transcendence in patients with advanced cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015;32(2):178–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Puchalski CM. Spirituality in the cancer trajectory. Ann Oncol. 2012;23(Suppl 3):49–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Mako C, Galek K, Poppito SR. Spiritual pain among patients with advanced cancer in palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2006;9(5):1106–1113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Delgado-Guay MO, Parsons HA, Hui D, De la Cruz MG, Thorney S, Bruera E. Spirituality, religiosity, and spiritual pain among caregivers of patients with advanced cancer. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30(5):455–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Broadhurst K, Harrington A. A Thematic literature review: the importance of providing spiritual care for end-of-life patients who have experienced transcendence phenomena. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015;33(9):881–893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lawrence M, Repede E. The incidence of deathbed communications and their impact on the dying process. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30(7):632–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Kerr CW, Donnelly JP, Wright ST, et al. End-of-life dreams and visions: a longitudinal study of hospice patients’ experiences. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(3):296–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fenwick P, Lovelace H, Brayne S. Comfort for the dying: five year retrospective and one year prospective studies of end of life experiences. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2010;51(2):173–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Morita T, Naito AS, Aoyama M, et al. Nationwide Japanese survey about deathbed visions: “my deceased mother took me to heaven”. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(5):646–654. e645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mazzarino-Willett A. Deathbed phenomena: its role in peaceful death and terminal restlessness. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2010;27(2):127–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nosek CL, Kerr CW, Woodworth J, et al. End-of-life dreams and visions: a qualitative perspective from hospice patients. Am J Hosp Pall Med. 2015;32(3):269–274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Barbato M, Blunden C, Reid K, Irwin H, Rodriguez P. Parapsychological phenomena near the time of death. J Palliat Care. 1999;15(2):30–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Fenwick P, Brayne S. End-of-life experiences: reaching out for compassion, communication, and connection: meaning of deathbed visions and coincidences. Am J Hosp Hosp Palliat Care. 2011;28(1):7–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. van Lommel P, van Wees R, Meyers V, Elfferich I. Near-death experience in survivors of cardiac arrest: a prospective study in the Netherlands. Lancet. 2001;358(9298):2039–2045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. van Lommel P. Near-death experiences: the experience of the self as real and not as an illusion. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2011;1234:19–28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. van Lommel P. Consciousness beyond Life: The Science of the Near-death Experience. New York, NY: HarperOne; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Greyson B. Near-death experiences and spirituality. Zygon. 2006;41(2):393–414. [Google Scholar]

- 35. Ring K, Elsaesser Valarino E. Lessons from the Light: What We Can Learn from the Near-death Experience. New York, NY: Insight Books; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Osis K. Deathbed Observations by Physicians and Nurses. New York, NY: Parapsychology Foundation; 1961. [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sanders MA. Nearing Death Awareness: A Guide to the Language, Visions and Dreams of the Dying. London, UK: Jessica Kingsley; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Renz M, Schuett Mao M, Bueche D, Cerny T, Strasser F. Dying is a transition. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2013;30(3):283–290. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hepper PG. The beginnings of the mind: evidence from the behaviour of the fetus. J Reprod Infant Psychol. 1994;12(3):143–154. [Google Scholar]

- 40. Smith JA, Larkin MH, Flowers P. Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis: Theory, Method and Research. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE; 2009. [Google Scholar]

- 41. Blanke O, Metzinger T. Full-body illusions and minimal phenomenal selfhood. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13(1):7–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Blanke O. Multisensory brain mechanisms of bodily self-consciousness. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13(8):556–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Frick E, Riedner C, Fegg MJ, Hauf S, Borasio GD. A clinical interview assessing cancer patients’ spiritual needs and preferences. Eur J Cancer Care. 2006;15(3):238–243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. van den Beuken-van Everdingen MH, Hochstenbach LM, Joosten EA, Tjan-Heijnen VC, Janssen DJ. Update on prevalence of pain in patients with cancer: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;51(6):1070–1090. e1079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Syrjala KL, Jensen MP, Mendoza ME, Yi JC, Fisher HM, Keefe FJ. Psychological and behavioral approaches to cancer pain management. J Clin Oncol. 2014;32(16):1703–1711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Osis K, Haraldsson E. Deathbed observations by physicians and nurses: a cross-cultural survey. J Am Soc Psychical Res. 1977;71(3):237–259. [Google Scholar]

- 47. Engelmann D, Scheffold K, Friedrich M, et al. Death-related anxiety in patients with advanced cancer: validation of the German version of the death and dying distress scale. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016;52(4):582–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Sussman JC, Liu WM. Perceptions of two therapeutic approaches for palliative care patients experiencing death anxiety. Palliat Support Care. 2014;12(4):251–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. King M, Llewellyin H, Leurent B, et al. Spiritual beliefs near the end of life: a prospective cohort study of people with cancer receiving palliative care. Psychooncology. 2013;22(11):2505–2512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kolva E, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, Breitbart W, Brescia R. Anxiety in terminally ill cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2011;42(5):691–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Wong PTP, Reker GT, Gesser T. Death attitude profile-revised: a multidimensional measure of attitudes toward death In: Niemeyer RA, ed. Death Anxiety Handbook: Research, Instrumentation and Application. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis; 1994:121–148. [Google Scholar]

- 52. van Laarhoven HW, Schilderman J, Vissers KC, Verhagen CA, Prins J. Images of God in relation to coping strategies of palliative cancer patients. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2010;40(4):495–501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Rousseau P. Death denial. J Clin Oncol. 2000;18(23):3998–3999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Tang ST, Chang WC, Chen JS, Chou WC, Hsieh CH, Chen CH. Associations of prognostic awareness/acceptance with psychological distress, existential suffering, and quality of life in terminally ill cancer patients’ last year of life. Psychooncology. 2016;25(4):455–462. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Chochinov HM, Tataryn DJ, Wilson KG, Ennis M, Lander S. Prognostic awareness and the terminally ill. Psychosomatics. 2000;41(6):500–504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Landis JR, Koch GG. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 1977;33(1):159–174. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]