Abstract

Objective:

To examine whether low managerial quality predicts risk of depressive disorders.

Methods:

Using multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression analyses we examined the prospective association of individual-level and workplace-mean managerial quality with onset of depressive disorders among 5244 eldercare workers from 274 workplaces during 20 months follow-up.

Results:

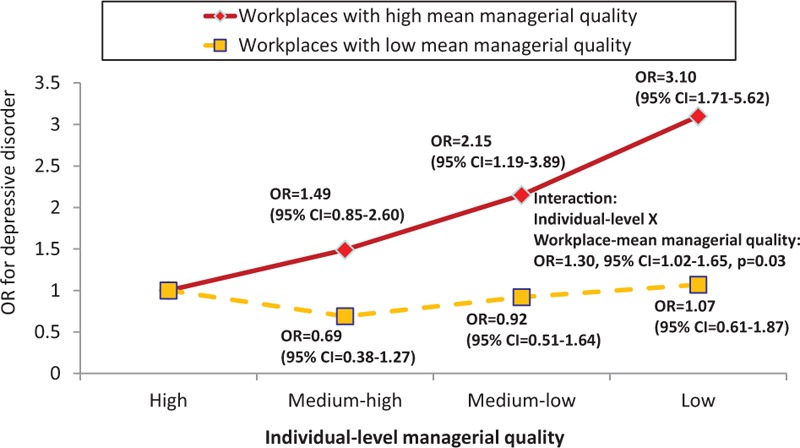

Low managerial quality predicted onset of depressive disorders in both the individual-level (odds ratio [OR] = 1.85, 95% confidence interval [CI] = 1.25 to 2.76) and the workplace-mean analysis (OR = 1.48, 95% CI = 1.06 to 2.07). Low individual-level managerial quality predicted onset of depressive disorders when workplace-mean managerial quality was high (OR = 3.10, 95% CI = 1.71 to 5.62) but not when it was low (OR = 1.07, 95% CI = 0.61 to 1.87). This interaction was statistically significant (P = 0.03).

Conclusions:

Both low individual-level and low workplace-mean managerial quality predicted risk of depressive disorders. The association was strongest among individuals reporting low managerial quality at workplaces with high workplace-mean managerial quality.

Eldercare workers in Denmark have an increased risk of depressive disorders, compared with the general workforce.1,2 Whether this is due to working conditions in eldercare, selection of individuals prone to depressive disorders into eldercare work, or other reasons is unclear.2,3

Managerial quality, also called leadership quality or supervisory quality, pertains to different aspects of the behavior of a manager towards his or her subordinates, for example, providing opportunities for development, solving conflicts, or caring about the employees’ well-being.4,5 It has been hypothesized that exposure to low managerial quality may be a health risk for employees, but empirical findings have been inconsistent.5–10 Some studies found low managerial quality to be associated with risk of sickness absence,6 coronary heart disease,5 depressive symptoms,7 whereas other studies did not find such associations.8–10

An important challenge in studying managerial quality and depressive disorders is that most studies rely on self-report of both exposure and outcome. Employees with low mood may be predisposed to both underestimate the managerial quality of their superiors and to later develop depressive disorders, causing spurious associations between self-reported managerial quality and depressive disorders.2,11 One strategy for addressing this bias is to analyze self-reported managerial quality not at the individual-level, but instead to average managerial quality scores over the whole workgroup and assign each workgroup member this averaged score.12 This average score is thought to indicate the work environment shared by all employees in the workgroup, in this case the shared experience of managerial quality. The evidence for the interpretation that the relation of low managerial quality with risk of depressive disorders is causal and not due to reporting bias would be considerably strengthened, if it can be shown that not only low individual-level managerial quality but also low workplace-mean managerial quality predicts risk of depressive disorders.

Examining both individual and shared experience of managerial quality is a potentially rewarding endeavor, however, not only for addressing reporting bias, but also because individual and shared experiences may be qualitatively different. Whereas some managers may have a good or problematic relation to all of their subordinates, other managers may treat subordinates in different ways and it is possible that a manager has a good relation to the majority of the employees but a very problematic relation to a few employees or maybe only a single employee. These different constellations may have different consequences for employees’ mental health. It is conceivable that individuals who experience the quality of their managers as low may be less affected by this if their colleagues have a similar experience, as these congruent experiences may strengthen the bonds between the employees. On the other hand, individuals experiencing the quality of their managers as low in an environment that on average experiencing managerial quality as high may be particularly strained. These employees not only have to deal with experiencing low managerial quality, but in addition may also feel isolated from their colleagues who do not share their experiences.

In this article, we have two research aims. First, to test the hypothesis that both individual-level and workplace-mean managerial quality predict onset of depressive disorders in a cohort of Danish eldercare workers. Second, to conduct an explorative, that is, hypothesis-generating analysis, examining whether the association between individual-level managerial quality and risk of depressive disorders is different in workplaces with high and low workplace-mean managerial quality, respectively.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

We analyzed the prospective association of managerial quality and risk of depressive disorders using data from the Danish Eldercare Worker Cohort Study. In 2004, 65 Danish municipalities were invited to participate in the study and 36 accepted the invitation. From December 2004 to August 2005 all 12,744 employees working in the eldercare sector in the 36 municipalities received a questionnaire on working conditions and health and 9949 employees (78.1%) from 286 work units responded. Of those, 6304 (63.4%) responded to a follow-up questionnaire sent out from October 2006 to September 2007. Mean time between baseline and follow-up was 20 months (standard deviation [SD]: 2.4 months). The study was registered at the Danish Data Protection Agency (Datatilsynet). According to Danish law questionnaire and register-based studies do not need approval of the National Committee of Health Research Ethics (Det National Videnskabetisk Komité).

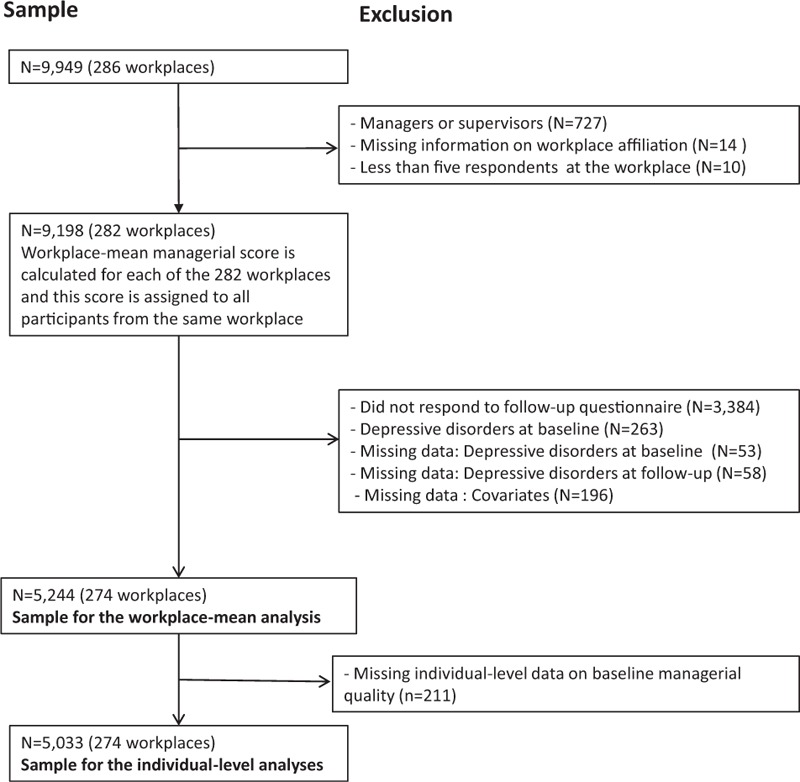

Figure 1 depicts how we constructed the samples for the individual-level and the workplace-mean analyses of managerial quality. Of the 9949 baseline responders, we excluded 727 managers, 14 individuals with missing information on workplace affiliation, and 10 individuals from workplaces with less than five respondents, yielding a sample of 9198 individuals from 282 workplaces. The term “workplace” pertains to the most detailed information that was available. If we had information about the work unit or the work team of the participants, “workplace” refers to this unit or team. If this information was not available, “workplace” refers to larger organizational units, for example, a department or the whole eldercare home.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart on the constructing of the samples for the workplace-mean and the individual-level analysis.

Of the 9198 participants, 8744 participants had no missing data on the four managerial quality items. We calculated the managerial quality score for these participants and then calculated the average managerial quality score for each of the 282 workplaces. These workplace-means were then assigned to all participants who worked in the same workplace, irrespective of their individual-level score and irrespective of whether or not they had responded to the four managerial quality items, yielding a workplace-mean score for all 9198 participants.

In the next step, we excluded individuals because of non-response to the follow-up questionnaire (N = 3384), depressive disorders at baseline (N = 263), missing data on depressive disorders at baseline (N = 53), or at follow-up (N = 58), and missing data on covariates (N = 196), yielding a sample of 5244 participants from 274 workplaces for the workplace-level analysis. For the individual-level analysis, we further excluded 211 participants because of missing individual-level data on baseline managerial quality, yielding a sample of 5033 participants from 274 workplaces.

Measurement of Managerial Quality

We measured managerial quality with the four item “Quality of leadership” scale from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire, version II (COPSOQ-II), a widely used instrument for assessing the psychosocial work environment, both in Denmark and internationally.4 The wording of the items was: “To what extent would you say that your immediate supervisor”: (i) “makes sure that the individual member of staff has good developmental opportunities?”; (ii) “gives high priority to job satisfaction?”; (iii) “is good at work planning?”; (iv) “is good at solving conflicts?” Items were responded on a five-point scale, ranging from “To a very small extent” to “To a very large extent.” Scores were summed up, yielding a scale with a possible range from 4 to 20 points with higher scores indicating higher managerial quality. We calculated separate scales for individual-level and workplace-mean managerial quality and then divided both scales into quartiles by their specific distributions. For the interaction analysis, we further dichotomized workplace-mean managerial quality into low and high by collapsing the first and second and the third and fourth quartile, respectively.

Measurement of Depressive Disorders

We measured depressive disorders by the Major Depression Inventory (MDI) that consists of 10 items assessing the presence of depressive symptoms during the last 2 weeks. Each item is responded on a scale ranging from 0 (the symptom has not been present at all) to 5 (the symptom has been present all of the time). The MDI has been validated in several studies, both against other psychiatric rating scales (eg, the Hamilton Depression scale) and against diagnostic psychiatric interviews.13–15 Based on these studies, a MDI score of equal to or more than 20 points has been recommended for identifying individuals with any form of depressive disorder and consequently we used this cut-off point in our study.

Measurement of Covariates

As covariates we included sex, age (continuous, in years), cohabitation (yes/no), type of job (employed in care work vs employed in noncare work, eg, kitchen staff, janitors in the eldercare home), seniority (continuous, in years), and number of participants at the workplace. Sex, age, cohabitation, and type of job were included because they were related to risk of depressive disorders in previous epidemiological studies.16–19 Number of participants at the workplace was included to control for that precision of the workplace-mean managerial quality variable might differ by the number of employees contributing to the calculation of the variable.

In a sensitivity analysis, we further adjusted for exposure to workplace bullying at baseline, because we had previously reported an association of workplace bullying with depressive disorders in the same cohort.20 Workplace bullying was measured by providing the respondents with a definition of bullying (exposure to repeated and continuous offensive and negative acts, which is difficult to defend oneself against) followed by the question “Have you been exposed to bullying at your current workplace within the last 12 months?”. Response categories were “no,” “yes, now and then,” “yes, monthly,” “yes, weekly,” and “yes, daily, or almost daily.” As in our previous study,20 we created a 3-level exposure variable with the categories (i) “no,” (ii) “yes, occasionally” (combining “now and then” and “monthly”), and (iii) “yes, frequently” (combining “weekly” and “daily/almost daily”).

In another sensitivity analysis, we included a categorical variable on the number of participants per workplace as a rough proxy measure for type of workplace. We assumed workplaces with less than 25 participants likely to be work teams, workplaces with 26 to 75 participants likely to be departments, and workplaces with more than 76 participants likely to be organizations.

Statistical Analysis

We estimated the amount of variance in individual-level managerial quality explained by workplace, by calculating intra-class correlations (ICC). We further calculated within-workplace agreement for a multiple item scale (rwg(j))21,22 with an excel spreadsheet provided by Biemann and Cole.23 Using multilevel mixed-effects logistic regression analysis (command “meqrlogit” in the statistical software package Stata 14.1; StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX) with workplace as a random effects variable, we tested the hypothesis that low managerial quality at baseline predicted risk of depressive disorders at follow-up. Analyses were conducted separately for individual-level managerial quality and workplace-mean managerial quality. We calculated crude associations and associations adjusted for sex, age, cohabitation, type of job, seniority, number of respondents at the workplace, and lengths of follow-up.

To explore whether the association of individual-level managerial quality with risk of depressive disorders was modified by workplace-mean managerial quality, we repeated the analyses on individual-level managerial quality and depressive disorders stratified by high and low workplace-mean managerial quality. Finally, we analyzed whether there was a statistical significant interaction of individual-level and workplace-mean managerial quality with regard to risk of depressive disorders by calculating a multiplicative interaction term (product of individual-level managerial quality [in quartiles] times workplace-mean managerial quality [dichotomized]) and adding this term to the most-adjusted model.

In a sensitivity analysis, we repeated all models while additionally adjusting for workplace bullying. We did not include workplace bullying in the main analysis, because workplace bullying and managerial quality may overlap if the bullying had been done or tolerated by the manager. In another sensitivity analysis we repeated all models while including a proxy measure for type of workplace (work team, department, organization). We did not include type of workplace in the main analysis, because of the roughness of our proxy measure.

RESULTS

Table 1 shows the characteristics of the participants and the number of respondents per workplace for the individual-level and the workplace-mean analysis. In both samples the vast majority of participants were women, the mean age was 46 years and the average number of participants per workplace was 52.

TABLE 1.

Characteristics of the Study Participants

| Individual-Level Analysis (n = 5,033) | Workplace-Mean Analysis (n = 5,244) | ||

| Sex | |||

| Women | n (%) | 4,887 (97.1%) | 5,089 (97.0%) |

| Men | n (%) | 146 (2.9%) | 155 (3.0%) |

| Age in years | Mean (SD) | 46.09 (8.96) | 46.20 (9.00) |

| Living together with a partner | |||

| No | n (%) | 914 (18.2%) | 952 (18.2%) |

| Yes | n (%) | 4,119 (81.8%) | 4,292 (81.8%) |

| Type of job | |||

| Care work | n (%) | 4,485 (89.1%) | 4,650 (88.7%) |

| Noncare work | n (%) | 548 (10.9) | 594 (11.3) |

| Seniority in years | Mean (SD) | 8.66 (7.16) | 8.68 (7.20) |

| Exposed to bullying at baseline | |||

| No | n (%) | 4,508 (89.6%) | 4,701 (89.6%) |

| Yes, occasionally | n (%) | 460 (9.1%) | 476 (9.1%) |

| Yes, frequently | n (%) | 65 (1.3%) | 67 (1.3%) |

| Number of participants per workplace | Mean (SD) | 52.50 (42.78) | 52.33 (42.64) |

| 5–25 | n (%) | 1,029 (24.0%) | 1,259 (24.0%) |

| 26–50 | n (%) | 2,024 (40.2%) | 2,125 (40.5%) |

| 51–75 | n (%) | 1,100 (21.9%) | 1,136 (21.7%) |

| 76–100 | n (%) | 131 (2.6%) | 134 (2.6%) |

| >100 | n (%) | 559 (11.3%) | 590 (11.2%) |

| Self-reported managerial quality | Mean (SD) | 13.35 (3.39) | NA |

| Low | n (%) | 823 (16.4%) | NA |

| Medium–low | n (%) | 1,666 (33.1%) | NA |

| Medium–high | n (%) | 1,228 (24.4%) | NA |

| High | n (%) | 1,316 (26.1%) | NA |

| Workplace-mean managerial quality | Mean (SD) | NA | 13.17 (1.43) |

| Low | n (%) | NA | 1,284 (24.5%) |

| Medium–low | n (%) | NA | 1,309 (25.0%) |

| Medium–high | n (%) | NA | 1,324 (25.2%) |

| High | n (%) | NA | 1,327 (25.3%) |

SD, standard deviation.

The mean score of individual-level managerial quality was 13 with a SD of 3.39 and a range from 4 to 20 points. Workplace-mean managerial quality also showed a mean of 13, but had, as expected, a considerably lower variation with a SD of 1.43 and a range from 8.35 to 17.64 points. The ICC was 0.18, meaning that 18% of the variation in individual-level managerial quality was explained by the workplace. The mean rwg(j) was 0.83 (SD: 0.14) with a median of 0.81, which is an acceptable agreement.24

Managerial Quality at Baseline and Risk of Depressive Disorders at Follow-Up

Table 2 shows the prospective associations of individual-level and workplace-mean managerial quality at baseline with risk of depressive disorders at follow-up. In the analysis of individual-level managerial quality, 287 out of 5033 participants (5.7%) showed a depressive disorder at follow-up. A 1 SD decrease in individual-level managerial quality predicted a 29% increased risk of depressive disorders in the adjusted model (OR = 1.29, 95% CI = 1.15 to 1.45, P < 0.001). When we analyzed individual-level managerial quality as a categorical variable, we found that participants scoring in the lowest quartile of managerial quality had a statistically increased risk of depressive disorders, compared with participants scoring in the highest quartile (OR = 1.85, 95% CI = 1.25 to 2.76, P = 0.002).

TABLE 2.

Prospective Association of Individual-Level and Workplace-Mean Managerial Quality With Risk of Depressive Disorder After 20 Months Follow-Up

| Crude | Adjusted | |||||

| N | Cases (%) | OR | (95% CI) | OR | (95% CI) | |

| Individual-level managerial quality, continuous | 5,033 | 287 (5.7%) | 1.29 | (1.15–1.45) | 1.29 | (1.15–1.45) |

| Individual-level managerial quality, categorical | ||||||

| High (17–20 points) | 823 | 35 (4.3%) | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference |

| Medium–high (14–16 points) | 1,666 | 77 (4.6%) | 1.09 | (0.72–1.64) | 1.10 | (0.73–1.65) |

| Medium–low (12–13 points) | 1,228 | 76 (6.2%) | 1.49 | (0.99–2.24) | 1.50 | (1.00–2.27) |

| Low (4–11 points) | 1,316 | 99 (7.5%) | 1.83 | (1.23–2.72) | 1.85 | (1.25–2.76) |

| Workplace-mean managerial quality, continuous | 5,244 | 304 (5.8%) | 1.07 | (0.95–1.21) | 1.08 | (0.96–1.21) |

| Workplace-mean managerial quality, categorical | ||||||

| High (14.02–17.64 points) | 1,284 | 64 (5.0%) | 1 | Reference | 1 | Reference |

| Medium–high (13.14–14.01 points) | 1,309 | 76 (5.8%) | 1.18 | (0.83–1.66) | 1.18 | (0.82–1.68) |

| Medium–low (12.21–13.13 points) | 1,324 | 69 (5.2%) | 1.05 | (0.74–1.49) | 1.08 | (0.75–1.54) |

| Low (8.35–12.20 points) | 1,327 | 95 (7.2%) | 1.47 | (1.06–2.04) | 1.48 | (1.06–2.07) |

Multilevel logistic regression analysis. Adjusted for sex, age, cohabitation, type of job, seniority, number of respondents at the workplace, lengths of follow-up. CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

In the analyses of workplace-mean managerial quality, 304 out of 5244 participants (5.8%) showed a depressive disorder at follow-up (Table 2). A 1 SD decrease in workplace-mean managerial quality did not predict risk of depressive disorders in the adjusted model (OR = 1.08, 95% CI = 0.96 to 1.21, P = 0.23). However, when contrasting the most exposed with the least exposed group, we found that participants working at workplaces with a low mean score of managerial quality had a statistically significant increased risk of depressive disorders, compared with participants working at workplaces with a high mean score of managerial quality (OR = 1.48, 95% CI = 1.06 to 2.07, P = 0.02).

Individual-Level Managerial Quality and Risk of Depressive Disorders at Workplaces with High or Low Mean Managerial Quality

Figure 2 shows the association of self-reported managerial quality with risk of depressive disorders, stratified by high and low workplace-mean managerial quality. Low individual-level managerial quality predicted risk of depressive disorders (OR = 3.10, 95% CI = 1.71 to 5.62, P < 0.001) when workplace-mean managerial quality was high, but not when workplace-mean managerial quality was low (OR = 1.07, 95% CI = 0.61 to 1.87, P = 0.81). The interaction of individual-level managerial quality and workplace-mean managerial quality with regard to risk of depressive disorders was statistically significant (OR = 1.30, 95% CI = 1.02 to 1.65, P = 0.03).

FIGURE 2.

Prospective association of individual-level managerial quality with risk of depressive disorders after 20 months follow-up stratified by high (red solid line) and low (yellow broken line) workplace-mean managerial quality. Adjusted for sex, age, cohabitation, type of job, seniority, number of respondents at the workplace, lengths of follow-up.

Sensitivity Analyses

When we further adjusted the analyses for workplace bullying at baseline, associations marginally attenuated. The odds ratio for low managerial quality and risk of depressive disorders changed from 1.85 (95% CI = 1.25 to 2.76) to 1.64 (95% CI = 1.09 to 2.45) and from 1.48 (1.06 to 2.07) to 1.38 (0.99 to 1.93) in the individual-level and the workplace-mean analyses, respectively. The odds ratio for the interaction of individual-level with workplace mean managerial quality on risk of depressive disorders changed from 1.30 (95% CI = 1.02 to 1.65) to 1.29 (95% CI = 1.02 to 1.64).

When we repeated all analyses while adjusting for a proxy measure of type of workplace (work team, department, organization), all estimates remained virtually unchanged (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

Summary of Results

Eldercare workers reporting exposure to low managerial quality had a 1.9-fold increased risk of onset of depressive disorders compared with eldercare workers reporting high managerial quality. When we used workplace-mean managerial quality we found that employees working at workplaces with low average managerial quality had a 1.5-fold increased risk of depressive disorders compared with employees working at workplaces with high average managerial quality. Further analyses showed a statistical significant interaction between individual-level and workplace-mean managerial quality. Employees reporting exposure to low managerial quality had a 3.1-fold increased risk of depressive disorders when they worked at workplaces with high workplace-mean managerial quality, but no increased risk if they worked at workplaces with low workplace-mean managerial quality.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study demonstrating the importance of workplace-mean managerial quality for employees’ risk of depressive disorders and the first study showing an interaction of individual-level and workplace-mean managerial quality with regard to the risk of depressive disorders.

Psychosocial Work Environment and Risk of Depressive Disorders

Depressive disorders have a complex etiology, likely encompassing the interplay of social, psychological, and biological factors.25,26 Whether psychosocial working conditions can increase risk of depressive disorders has been controversially discussed.11,27 Recent meta-analyses suggest that job strain, that is, the combination of high psychological demands and low decision latitude at work,28,29 low decision latitude by itself,29 effort-reward imbalance,30 and workplace bullying29,31 are risk factors of depressive disorders. Low managerial quality has not been included as a risk factor of depressive disorders in these meta-analyses. One review, though, examined concepts likely overlapping with managerial quality, such as “supervisor support,” “workplace justice,” and “conflicts with superiors,” all of which were deemed as providing “limited evidence” with regard to risk of depressive disorders.29

Research on psychosocial work environment and risk of depressive disorders has been criticized for the reliance on self-reported exposure measurements that may render analyses vulnerable to common-method bias and spurious associations.2,11,32 Alternatives to self-reported exposure measurements are direct workplace observations,33 register data,34 job exposure matrices,35 or, as we did in the present study, averaging individual-level exposure data at the workplace-level. To our knowledge, no other study has yet examined workplace-mean managerial quality as a predictor of depressive disorders. However, a study by Grynderup et al36 found that workplace-mean procedural and relational justice at work, which may overlap with managerial quality, predicted risk of depressive disorders in a 2-year follow-up study of Danish public sector employees.

There are several mechanisms through which managerial quality may affect employees’ risk of depressive disorders. First, a good relation between managers and employees may be a source of workplace social support as described in the demand-control-support (iso-strain) model by Johnson and Hall37 and Johnson et al.38 High social support by managers may either help to directly reduce high work demands or, in cases where a reduction of work demands is not possible, they may act as a buffer against the potential health hazardous effects of these high work demands. Second, poor managerial quality may cause unnecessary or unreasonable work tasks, which are potentially health-hazardous stressors according to the stress-as-offense-to-self theory.39 A recent cohort study of Danish human service workers reported that unnecessary work tasks predicted a decrease in employees’ mental health.40 Third, poor managerial quality will probably often go hand in hand with lack of respect and lack appreciation of employees, which are health hazardous stressors according to the effort-reward imbalance theory.41 In a recent meta-analysis, effort-reward imbalance was found to be a risk factor for depressive disorders.30

Interaction of Individual-Level and Workplace-Mean Managerial Quality

That individual-level managerial quality predicted risk of depressive disorders when workplace-mean managerial quality was high, but not when it was low, is a novel finding. Interpretations have to be made with caution, as the result emerged from data exploration and not from formal hypothesis testing. This said, several explanations for this result are possible. First, a congruent perception of low managerial quality among employees may strengthen the bonds between employees and may even result in collective actions to handle the situation, which may protect against developing depressive disorders. Second, as it has been discussed in the literature on income inequality and health,42 under certain conditions relative adversity may be worse than absolute adversity. Applied to our study this may mean that experiencing low managerial quality may be more tolerable in an environment where everyone else is also experiencing low managerial quality. Conversely, experiencing low managerial quality in an environment where everyone else is experiencing high managerial quality may be particular hurtful and may result in decreasing self-esteem, which is considered an important mechanism in the etiology of depressive disorders.43,44 Third, an employee who perceives low managerial quality at a place where everyone else perceives high managerial quality may also diverge from his or her colleagues in other characteristics, not measured in this study, and some of these characteristics could be risk factors of depressive disorders. Further studies on the interaction of individual-level and workplace-mean managerial qualities are needed to get more insight into the possible mechanisms and explanations.

Strengths and Limitations

Strengths of the study are the prospective design, the measurement of both individual-level and workplace-mean managerial quality allowing multilevel analyses, and the use of a well-validated instrument for assessing depressive disorders. Eighteen percent of the variation in individual-level managerial quality was explained by the workplace, which is a sufficient proportion for justifying workplace-mean analyses.45 It is a further strength that we examined managerial quality both as a continuous variable and as a categorical variable, the latter allowing us to contrast groups reporting high and low managerial quality against each other.

These strengths have to be balanced against some limitations. First, although managerial quality was measured with a well-established scale from the COPSOQ-II,4 the scale consisted of only four items and may have captured only certain aspects of managerial quality. Second, although the MDI is a well-validated instrument, the gold standard for assessing depressive disorders is a clinical diagnostic interview,46 which was not available in our study. Third, while we ascertained occurrence of depressive disorders at baseline and at 20-months follow-up, we do not know how many participants developed a depressive disorder after baseline but were in remission at follow-up. Fourth, the survey did not include information on other potential causes of depressive disorders, such as traumatic childhood experiences,47,48 marital conflicts,49 or adverse life events,44,50 and consequently we could not adjust for these factors. Fifth, our sample consisted of eldercare workers and further research is needed for elucidating whether results can be generalized to other occupational groups or the workforce in general.

Implications for Praxis

Our results suggest that both individual-level and workplace-mean managerial quality affect the mental health of employees. However, as the literature on this topic is sparse, replications of our findings are needed before firm conclusions can be drawn and recommendations for praxis can be made. Our results further indicate that for estimating the impact of managerial quality on employees’ mental health it may not be sufficient to only assess the individual employees’ appraisal of managerial quality, but that this individual appraisal needs to be seen in the context of the shared experienced managerial quality at the workplace.

Footnotes

Funding: The Danish Working Environment Research Fund (grant number 27-2010-03). The funding source had no further role in study design; in the collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; in the writing of the paper, and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

The authors report no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Hannerz H, Tüchsen F, Holbaek Pedersen B, Dyreborg J, Rugulies R, Albertsen K. Work-relatedness of mood disorders in Denmark. Scand J Work Environ Health 2009; 35:294–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Madsen IEH, Aust B, Burr H, Carneiro IG, Diderichsen F, Rugulies R. Paid care work and depression: a longitudinal study of antidepressant treatment in female eldercare workers before and after entering their profession. Depress Anxiety 2012; 29:605–613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Vammen MA, Mikkelsen S, Hansen ÅM, et al. Emotional demands at work and the risk of clinical depression: a longitudinal study in the Danish public sector. J Occup Environ Med 2016; 58:994–1001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Pejtersen JH, Kristensen TS, Borg V, Bjorner JB. The second version of the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire. Scand J Public Health 2010; 38 Suppl:8–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nyberg A, Alfredsson L, Theorell T, Westerlund H, Vahtera J, Kivimäki M. Managerial leadership and ischaemic heart disease among employees: the Swedish WOLF study. Occup Environ Med 2009; 66:51–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nyberg A, Westerlund H, Magnusson Hanson LL, Theorell T. Managerial leadership is associated with self-reported sickness absence and sickness presenteeism among Swedish men and women. Scand J Public Health 2008; 36:803–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finne LB, Christensen JO, Knardahl S. Psychological and social work factors as predictors of mental distress: a prospective study. PLoS One 2014; 9:e102514. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rugulies R, Aust B, Pejtersen JH. Do psychosocial work environment factors measured with scales from the Copenhagen Psychosocial Questionnaire predict register-based sickness absence of 3 weeks or more in Denmark? Scand J Public Health 2010; 38 Suppl:42–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lund T, Labriola M, Christensen KB, Bültmann U, Villadsen E, Burr H. Psychosocial work environment exposures as risk factors for long-term sickness absence among Danish employees: results from DWECS/DREAM. J Occup Environ Med 2005; 47:1141–1147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madsen IEH, Hanson LL, Rugulies R, et al. Does good leadership buffer effects of high emotional demands at work on risk of antidepressant treatment? A prospective study from two Nordic countries. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2014; 49:1209–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kivimäki M, Hotopf M, Henderson M. Do stressful working conditions cause psychiatric disorders? Occup Med (Lond) 2010; 60:86–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rugulies R. Studying the effect of the psychosocial work environment on risk of ill-health: towards a more comprehensive assessment of working conditions. Scand J Work Environ Health 2012; 38:187–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bech P, Rasmussen NA, Olsen LR, Noerholm V, Abildgaard W. The sensitivity and specificity of the major depression inventory, using the present state examination as the index of diagnostic validity. J Affect Disord 2001; 66:159–164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Olsen LR, Jensen DV, Noerholm V, Martiny K, Bech P. The internal and external validity of the Major Depression Inventory in measuring severity of depressive states. Psychol Med 2003; 33:351–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olsen LR, Mortensen EL, Bech P. Mental distress in the Danish general population. Acta Psychiatr Scand 2006; 113:477–484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, et al. The epidemiology of major depressive disorder: results from the National Comorbidity Survey Replication (NCS-R). JAMA 2003; 289:3095–3105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Madsen IEH, Diderichsen F, Burr H, Rugulies R. Person-related work and incident use of antidepressants: relations and mediating factors from the Danish work environment cohort study. Scand J Work Environ Health 2010; 36:435–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wieclaw J, Agerbo E, Mortensen PB, Bonde JP. Occupational risk of affective and stress-related disorders in the Danish workforce. Scand J Work Environ Health 2005; 31:343–351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Goldberg P, David S, Landre MF, Goldberg M, Dassa S, Fuhrer R. Work conditions and mental health among prison staff in France. Scand J Work Environ Health 1996; 22:45–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rugulies R, Madsen IEH, Hjarsbech PU, et al. Bullying at work and onset of a major depressive episode among Danish female eldercare workers. Scand J Work Environ Health 2012; 38:218–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.James LR, Demaree RG, Wolf G. Estimating within-group interrater reliability with and without response bias. J Appl Psychol 1984; 69:85–98. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Biemann T, Cole MS, Voelpel S. Within-group agreement: On the use (and misuse) of rWG and rWG(J) in leadership research and some best practice guidelines. Leadership Quart 2012; 23:66–80. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Biemann T, Cole MS. An Excel 2007 Tool for Computing Interrater Agreement (IRA) & Interrater Reliability (IRR) Estimates; 2014. Available at: http://www.sbuweb.tcu.edu/mscole/docs/Tool%20for%20Computing%20IRA%20and%20IRR%20Estimates_v1.5.zip Accessed September 3, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kouvonen A, Kivimäki M, Vahtera J, et al. Psychometric evaluation of a short measure of social capital at work. BMC Public Health 2006; 6:251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Toward a comprehensive developmental model for major depression in women. Am J Psychiatry 2002; 159:1133–1145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kendler KS, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Toward a comprehensive developmental model for major depression in men. Am J Psychiatry 2006; 163:115–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Netterstrøm B, Conrad N, Bech P, et al. The relation between work-related psychosocial factors and the development of depression. Epidemiol Rev 2008; 30:118–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Madsen IEH, Nyberg ST, Magnusson Hanson LL, et al. Job strain as a risk factor for clinical depression: systematic review and meta-analysis with additional individual participant data. Psychol Med 2017; 47:1342–1356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Theorell T, Hammarström A, Aronsson G, et al. A systematic review including meta-analysis of work environment and depressive symptoms. BMC Public Health 2015; 15:738. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rugulies R, Aust B, Madsen IEH. Effort-reward imbalance at work and risk of depressive disorders. A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Scand J Work Environ Health 2017; 43:294–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verkuil B, Atasayi S, Molendijk ML. Workplace bullying and mental health: a meta-analysis on cross-sectional and longitudinal data. PLoS One 2015; 10:e0135225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bonde JPE. Psychosocial factors at work and risk of depression: a systematic review of the epidemiological evidence. Occup Environ Med 2008; 65:438–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jakobsen LM, Jorgensen AFB, Thomsen BL, Greiner BA, Rugulies R. A multilevel study on the association of observer-assessed working conditions with depressive symptoms among female eldercare workers from 56 work units in 10 care homes in Denmark. BMJ Open 2015; 5:e008713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Virtanen M, Pentti J, Vahtera J, et al. Overcrowding in hospital wards as a predictor of antidepressant treatment among hospital staff. Am J Psychiatry 2008; 165:1482–1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cohidon C, Santin G, Chastang JF, Imbernon E, Niedhammer I. Psychosocial exposures at work and mental health: potential utility of a job-exposure matrix. J Occup Environ Med 2012; 54:184–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Grynderup MB, Mors O, Hansen ÅM, et al. Work-unit measures of organisational justice and risk of depression—a 2-year cohort study. Occup Environ Med 2013; 70:380–385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Johnson JV, Hall EM. Job strain, workplace social support, and cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study of a random sample of the Swedish working population. Am J Public Health 1988; 78:1336–1342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Johnson JV, Hall EM, Theorell T. Combined effects of job strain and social isolation on cardiovascular disease morbidity and mortality in a random sample of the Swedish male working population. Scand J Work Environ Health 1989; 15:271–279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Semmer NK, Jacobshagen N, Meier LL, et al. Illegitimate tasks as a source of work stress. Work Stress 2015; 29:32–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Madsen IEH, Tripathi M, Borritz M, Rugulies R. Unnecessary work tasks and mental health: a prospective analysis of Danish human service workers. Scand J Work Environ Health 2014; 40:631–638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Siegrist J. Adverse health effects of high-effort/low-reward conditions. J Occup Health Psychol 1996; 1:27–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Marmot M, Wilkinson RG. Psychosocial and material pathways in the relation between income and health: a response to Lynch et al. BMJ 2001; 322:1233–1236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown GW, Harris T. Social Origins of Depression. A Study of Psychiatric Disorder in Women. London: Tavistock; 1978. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kendler KS, Hettema JM, Butera F, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Life event dimensions of loss, humiliation, entrapment, and danger in the prediction of onsets of major depression and generalized anxiety. Arch Gen Psychiatry 2003; 60:789–796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Christensen KB, Nielsen ML, Rugulies R, Smith-Hansen L, Kristensen TS. Workplace levels of psychosocial factors as prospective predictors of registered sickness absence. J Occup Environ Med 2005; 47:933–940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Drill R, Nakash O, DeFife JA, Westen D. Assessment of clinical information: comparison of the validity of a structured clinical interview (the SCID) and the clinical diagnostic interview. J Nerv Ment Dis 2015; 203:459–462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kendler KS, Sheth K, Gardner CO, Prescott CA. Childhood parental loss and risk for first-onset of major depression and alcohol dependence: the time-decay of risk and sex differences. Psychol Med 2002; 32:1187–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kendler KS, Kuhn JW, Prescott CA. Childhood sexual abuse, stressful life events and risk for major depression in women. Psychol Med 2004; 34:1475–1482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Whisman MA, Bruce ML. Marital dissatisfaction and incidence of major depressive episode in a community sample. J Abnorm Psychol 1999; 108:674–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Harris T. Recent developments in understanding the psychosocial aspects of depression. Br Med Bull 2001; 57:17–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]