Abstract

Context

Standardized outcomes that define successful advance care planning (ACP) are lacking.

Objective

To create an Organizing Framework of ACP outcome constructs and rate the importance of these outcomes.

Methods

This study convened a Delphi panel consisting of 52 multidisciplinary, international ACP experts including clinicians, researchers, and policy leaders from four countries. We conducted literature reviews and solicited attendee input from 5 international ACP conferences to identify initial ACP outcome constructs. In 5 Delphi rounds, we asked panelists to rate patient-centered outcomes on a 7-point “not-at-all” to “extremely important” scale. We calculated means and analyzed panelists’ input to finalize an Organizing Framework and outcome rankings.

Results

Organizing Framework outcome domains included process (e.g., attitudes), actions (e.g., discussions), quality of care (e.g., satisfaction), and healthcare (e.g., utilization). The top 5 outcomes included (1) care consistent with goals, mean 6.71 (±SD 0.04); (2) surrogate designation, 6.55 (0.45); (3) surrogate documentation, 6.50 (0.11); (4) discussions with surrogates, 6.40 (0.19); and (5) documents and recorded wishes are accessible when needed 6.27 (0.11). Advance directive documentation was ranked 10th, 6.01 (0.21). Panelists raised caution about whether “care consistent with goals” 6.01 (0.21). Panelists raised can be reliably measured.

Conclusion

A large, multidisciplinary Delphi panel developed an Organizing Framework and rated the importance of ACP outcome constructs. Top rated outcomes should be used to evaluate the success of ACP initiatives. More research is needed to create reliable and valid measurement tools for the highest rated outcomes, particularly “care consistent with goals.”

Keywords: advance care planning, consensus, Delphi technique, outcome measures

INTRODUCTION

Advance care planning (ACP) is defined as a “process that supports adults at any age or stage of health in understanding and sharing their personal values, life goals, and preferences regarding future medical care.”(1–3) The conceptualization of ACP has broadened over the past decade from the completion of legal advance directives to a process that consists of many behaviors, such as choosing a surrogate decision maker, defining values and preferences for medical care, and communicating those wishes to others.(1, 2, 4) However, studies have used a wide variety of outcomes to measure the success of ACP programs and interventions, including advance directive completion, behavior change, healthcare utilization, and care consistent with goals, all of which have been variably measured.(5–10)

The field of ACP research currently lacks consensus about the most important patient-centered outcome domains and constructs that define successful ACP. This is important because there have been increasing ACP initiatives within healthcare systems, including payer reimbursement programs and quality metric initiatives.(8, 9, 11–17) Without a shared understanding of ACP outcomes, it is difficult to compare findings across research and clinical initiatives and to determine which ACP programs or tools are most effective.

Therefore, we convened a large, multidisciplinary Delphi panel of ACP experts in research, clinical care, policy, and law to identify and rate patient-centered ACP outcomes that best define successful ACP. This same panel also created the aforementioned consensus definition of ACP.(1) Our goal for this study was to create an Organizing Framework of ACP outcomes to begin to standardize ACP measurement, to identify and rate a broad set of ACP outcome constructs, to identify knowledge gaps, and to lay the groundwork for future research.

METHODS

Study Design and Participants

In an area that lacks consensus, the Delphi method is an established technique to solicit anonymous, structured feedback from experts through ranking and qualitative input.(18–21) Panelists consisted of researchers, clinicians, legal experts, and policy makers with expertise in ACP, and their recruitment and qualifications have been previously described.(1) The Delphi process was conducted between February 2015 and April 2017 and was determined to be exempt by the University of California, San Francisco Institutional Review Board.

Delphi Methods

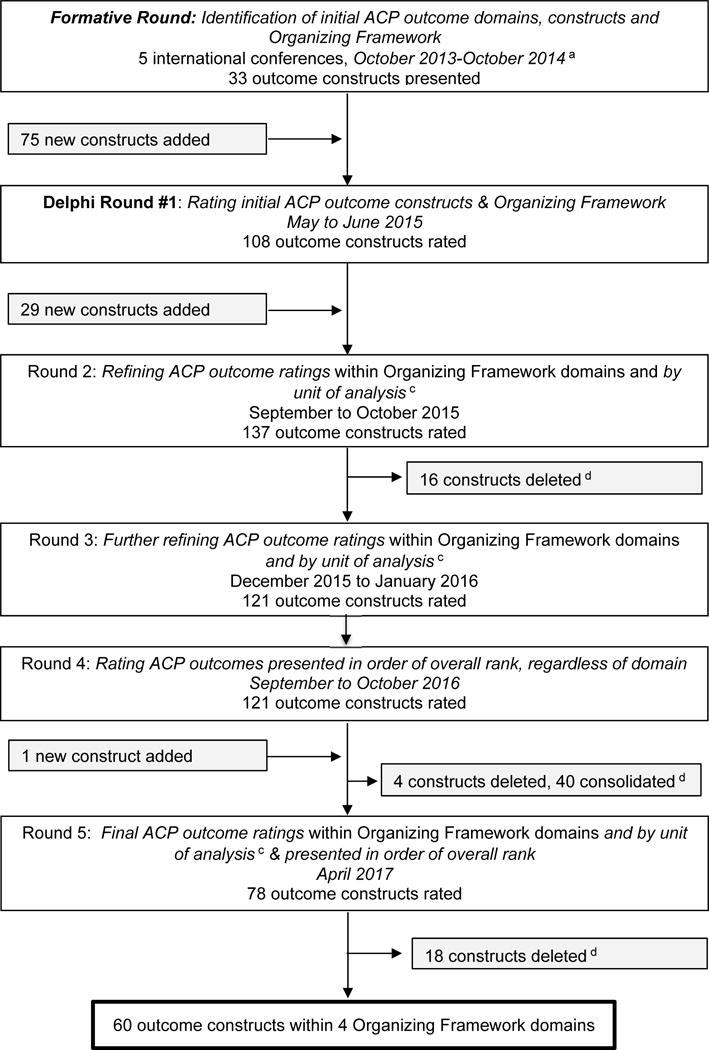

Because validated measures have yet to be standardized for most ACP outcomes, we focused on identifying, rating, and organizing the most important overarching ACP outcome domains and constructs rather than rating individual questionnaires, quality metrics, or survey questions. Figure 1 summarizes the activities and outcome constructs considered in each Delphi Round.

Figure 1. Delphi Method Flowchart.

aIndividual constructs are listed in the Appendix.

b5 International lectures given by author R.L.S. (i.e., Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network—Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, October 2013; University of Washington Palliative Care Conference, Seattle, Washington, USA, April 2014; Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network, Calgary, Alberta, Canada, May 2014; European White Paper on Advance Care Planning, Erasmus University Rotterdam, Wassenaar, Netherlands, June 2014; and the University of Colorado Palliative Care Conference, Denver, Colorado, USA, October 2014).

cUnit of Analysis refers to whom the question is being asked – at the patient, surrogate, or clinician level or through healthcare system data. For example, ACP discussions can be measured at the patient level by self-report, as well as by reports from surrogates and clinicians and by administrative data at the healthcare system level.

dConstructs were deleted if the mean rating was ≤ 1 SD below the overall mean. Constructs were consolidated based on content analysis by the steering committee.

Formative Round: Identification of initial ACP outcome domains, constructs, and an Organizing Framework

Prior to convening the Delphi panel, we conducted literature reviews to begin to collate ACP outcome overarching domains and individual constructs.(4, 8, 22–27) We initially presented 33 potential outcome constructs and solicited iterative input from multi-disciplinary attendees of 5 international palliative care and advance care planning conferences in the US, Canada, and the Netherlands listed in Figure 1. The study steering committee, authors RS, HL, DH, and JY, drafted an original version of the Organizing Framework of overarching ACP domains and subdomains based on published conceptual frameworks for ACP and end-of-life communication and input from the aforementioned lecture audiences (Figure 2).(22–28)

Figure 2. Organizing Framework of Advance Care Planning (ACP) Outcomes.

Because validated measures (i.e., survey instruments or questions) have yet to be standardized for most ACP outcomes, we focused on identifying overarching ACP outcome domains into an Organizing Framework and rating outcome constructs within those domains, rather than rating individual questionnaires, quality metrics, or survey questions.

a) Moderator Variables (largely un-modifiable) may influence the effectiveness or change the strength of an effect or relationship between two variables, such as an intervention’s ability to affect an outcome (i.e., moderators may act as an effect modifier). Moderators can often be used in stratified analyses.

b) Unit of Analysis refers to ranking of the outcome construct at the patient, surrogate, clinician, or healthcare system level. ACP outcomes can often be measured at the level of several units of analysis. For example, ACP discussions can be measured at the patient level by self-report, as well as by reports from surrogates and clinicians and by administrative data at the healthcare system level. Units of analysis are interrelated and interact in ways that affect ACP.

c) Process/Mediator Outcomes specify how or why an effect or relationship occurs. Mediators describe the psychological process that occurs to create the relationship, and as such are always dynamic properties of individuals (e.g., attitudes, perceived barriers, and behavior change (self-efficacy and readiness).

d) ACP Specific Action Outcomes measure an individual’s completion of specific components of ACP (yes or no) such as discussion or documentation of a surrogate or medical preferences.

e) Quality of Care Outcomes measure the impact of ACP on quality of care such as perceived satisfaction with care, communication, and decision making.

f) Healthcare Outcomes measure the impact of ACP on health outcomes, such as health status, mental health, and healthcare utilization.

g) Patient: We use the term patient to distinguish between the surrogate and clinician. However, this refers to any person who engages in ACP.

h) Timeframe: All outcomes can be measured at any stage of the life course and over time.

Instructions to Delphi Panel Members

We used the consensus definition of ACP defined by the Delphi panel as the basis for identifying and rating patient-centered ACP outcomes.(1) A unique link to a REDCap rating survey was sent to each panelist for Rounds 1 and 2.(29, 30) Tables of outcomes were sent to participants by individual email for Rounds 3–5. Responses were stored anonymously and presented only in aggregate form. Consensus was defined as an interquartile range (IQR) of 0, indicating very strong consensus.(3, 18, 31) We anticipated requiring at least 3 rounds, one to finalize the organizing framework, domains, and outcome constructs and two rounds for consensus. Additional rounds were triggered if consensus was not achieved or questions remained, as determined by the steering committee.(18–21)

Within each Delphi round, panel members were reminded that the goal of the ratings was to standardize patient-centered ACP outcomes across research studies and to arrive at a consensus about “the outcomes that best define successful ACP.” “Patient” may refer to any standardize patient-centered ACP outcomes across research studies and to arrive at a person who engages in ACP. Panelists were asked to rate the importance of individual outcome constructs, presented within one of 4 Organizing Framework domains (Figure 2 and results). Constructs were rated on a 7-point Likert scale (i.e., 1-not at all important, 2-extremely low importance, 3-low importance, 4-slightly important, 5-moderately important, 6-very important, 7-extremely important/essential for all ACP studies).(32, 33) The panel was encouraged to use the full 7-point scale to prevent ceiling effects. Open-ended text boxes were provided for panelists to comment on the Organizing Framework domains, subdomains, and outcome constructs; to suggest new constructs; or to suggest whether constructs should be consolidated or deleted. After each round, we reviewed the distribution, mean, median, and interquartile range of each rating. Then, anonymous mean rating scores from the prior round, new or deleted outcomes based on low ratings (i.e. 1 standard deviation below the mean), and a summary of open-ended comments were provided back to the panel for review. To reduce response burden, mean ratings from the prior rounds were auto-filled so panelists could easily leave the ratings unchanged, recommend changes, or provide additional comments.

Delphi Panel Round 1: Rating initial ACP outcome constructs and the Organizing Framework (Figure 1)

To provide context, each construct was presented within overarching Organizing Framework domains identified in our formative work (Figure 2 and results). Open-ended comments were encouraged.

Delphi Panel Round 2: Refining ACP Outcome Ratings at the Patient, Surrogate, Clinician, and Healthcare system-level (i.e., unit of analysis)

To provide context, outcome constructs were presented in tables that used the overarching Organizing Framework domain headers. Newly identified outcome constructs suggested by panelists were added. Based on panelists’ comments, the survey was also updated to include ratings for different “units of analysis” (i.e., at patient, surrogate, clinician, and healthcare system level, Figure 2 and results). For example, ACP discussions can be measured at the administrative data or healthcare system level. Since not every outcome construct is pertinent to from surrogates and clinicians and by every unit of analysis (e.g., “quality of death” could not be asked at the patient level), the Delphi panel also determined pertinent units of analysis iteratively over subsequent Rounds.

Delphi Panel Round 3: Further Refining of ACP Outcome Ratings by Unit of Analysis

Given the large number of constructs, we grouped the outcome constructs into 3 categories: (a) constructs with the highest ratings that may be recommended for most ACP studies, (b) constructs with medium ratings that could be used in certain ACP studies, and (c) constructs flagged for deletion based on low ratings in Round 2. Outcome constructs were presented within Organizing Framework domains (Figure 2).

Delphi Panel Round 4: Rating ACP outcomes overall by Rank Order, regardless of Organizing Framework Domain

Panelists had been rating outcome constructs within Organizing Framework overarching domains and not in overall rank order. Therefore, the steering committee determined it was important for the panel to review and rate the overall outcome rankings, regardless of domain or subdomain. We listed the constructs in sequential ranking order overall (regardless of domain) for review. The Organizing Framework was also provided for context.

Delphi Panel Round #5: Finalizing ACP Outcome Ratings by Organizing Framework Domain and Overall Rank

Because panelists suggested significant consolidation of outcome constructs in Round 4, the steering committee determined it was important for the panel to review these consolidations. Outcome constructs were again presented within Organizing Framework domains. In addition, the construct’s overall rank was provided for context. In the final round, panelists were offered $25 for their time.

Analysis

We calculated the mean ratings (± standard deviation), medians, and interquartile ranges for each ACP outcome construct at each unit of analysis (i.e., patient, surrogate, clinician, or healthcare level), where appropriate. Because the ratings were normally distributed for each round, we presented mean ratings rather than median values for panel review. We ordered the constructs by mean ratings within the Organizing Framework domains and subdomains and by overall rank across all domains.

Our study team calculated rankings based on Delphi ratings, and the steering committee prioritized the ranking at the patient-level unit of analysis. Exceptions were made based on Delphi recommendations when patient-level measures were not pertinent. For example, constructs concerning healthcare utilization, such as hospital length of stay, were prioritized at the healthcare system level because objective administrative data is often considered more accurate.(34) Furthermore, some outcome constructs, such as quality of the dying experience, could only be rated at the surrogate or clinician level. In these cases, we took the most highly rated unit of analysis (i.e., surrogate or clinician) and used that mean value in our overall ranking.

Items were flagged for deletion if their mean rating was less than one standard deviation below the overall mean in Round 2 and 5 (Appendix 1). In addition, the steering committee reviewed open-ended qualitative comments at every round using content analysis to refine the Organizing Framework, identify new ACP outcome constructs, and consolidate constructs. The committee selected quotes that most illustrated the tensions expressed about the rating process.

RESULTS

Fifty-five ACP experts were invited and three declined to participate (96% response rate) resulting in a 52-member Delphi panel from four countries and several disciplines (Table 1). We initially presented 33 outcome constructs to multi-disciplinary audience members from 5 international conferences (Figure 1). Comments collated from these conferences resulted in 75 additional outcome constructs organized within Organizing Framework domains (Figure 2, Appendix 1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Delphi Panel Members, n=52

| Characteristic | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Country of residence | |

| United States | 42 (80%) |

| Canada | 6 (12%) |

| Netherlands | 2 (4%) |

| Australia | 2 (4%) |

| Gender | |

| Women | 33 (63%) |

| Type of Expert | |

| Research | 38 (71%) |

| Clinician/Policy expert | 13 (25%) |

| Law | 2 (4%) |

| Primary Discipline | |

| Physician | 38 (73%) |

| Nurse | 4 (8%) |

| Lawyer | 2 (4%) |

| PhD/Other | 8 (15%) |

Organizing Framework and Outcome Domains

The overarching domains included moderator variables such as demographic characteristics, which were not included in the outcome ratings. However, many panelists noted the importance of the characteristics of the individual, the community, and health systems for the success of ACP (Figure 1). The 4 outcome domains used for ratings were: 1) process, 2) action, 3) quality of care, and 4) healthcare outcomes. Process or Mediator Outcomes were defined as outcomes that specify how or why an effect or relationship occurs, such as dynamic psychosocial properties of the individual (e.g., beliefs) and included subdomains of behavior change and perceptions. ACP Action Outcomes were defined as outcomes that measure an individual’s completion of specific ACP tasks, and included subdomains of communication and documentation of surrogates as well as values and preferences. Quality of Care Outcomes were defined as outcomes that measure the impact of ACP on quality of care (e.g., satisfaction with communication and decision making), and included subdomains of care consistent with goals and satisfaction with care. Healthcare Outcomes were defined as outcomes that measure the impact of ACP on health outcomes, and included subdomains of health status, mental health, and healthcare utilization.

In developing the Organizing Framework, panelists reported nuances relating to units of analysis: “Can you indicate [on the Framework] that patient/surrogate/clinician operate within the healthcare system and are interrelated” and in addition “I had a hard time rating (in Round 1) because the importance of these outcomes differ for addition “I had a hard time rating (in Round 1) patients, surrogates or clinicians.” Panelists also reported nuances in terms of timing of measurement: “Some domains may be relevant depending on the patient population targeted [and] life stage healthy vs seriously ill.” In addition, “Care consistent with goals may pertain to current goals for medical treatment or at the very end of life.” Thus, we refined the Framework to show how outcomes may be measured in or pertain to the patient, surrogate, clinician or the healthcare system “unit of analysis,” and how the “units” are interrelated and interact in ways that may affect ACP. The Framework also shows how outcomes may be measured at any point along the life course (Figure 2).

Outcome Construct Rounds and Ratings

In Round 1, 52 panelists rated 108 outcomes constructs within the Organizing Framework domains. At this stage panelists recommended 29 additional constructs (Figure 1, Appendix 1). In Round 2, 45 panelists (87% response rate) reviewed 137 constructs within the Organizing Framework domains and, due to Delphi panel request, by each unit of analysis. No new constructs were proposed. In Round 3, 32 panelists (62% response rate) rated 137 constructs within the Organizing Framework domains and by each unit of analysis, and panelists agreed to delete 16 constructs with low ratings (i.e., ≤ 1 SD below the mean). In Round 4, 41 panelists (79% response rate) rated 121 constructs listed in overall rank order (i.e., not within domain). In content analysis, 4 items were rated low and considered moderators, such as trust, surrogate availability, and symptoms; “Symptoms…clearly moderate the process but are not directly part of it.” Panelists’ comments also helped to consolidate an additional 40 constructs, “A lot of construct overlap and non-independence in these items.” “Items [with] significant overlap you could combine” (Appendix 1). In Round 5, 44 panelists (85% response rate) rated 78 outcome constructs within the Organizing Framework domains and by each unit of analysis. Seventeen constructs were deleted based on low ratings (Figure 1).

Top Rated Constructs

Table 2 displays the top 10 rated outcome constructs. “Care consistent with goals” was ranked highest, mean 6.71 (SD ±0.04). Constructs related to surrogates were also ranked highly. Physician treatment orders were ranked 7th and advance directives were ranked 10th (Table 2). Table 3 displays the mean ratings and rankings within each of the Organizing Framework domains and subdomains of all of the 60 constructs that demonstrated very high consensus. All mean ratings, rankings and medians at all units of analysis (i.e., patient, surrogate, clinician, or healthcare system) are included in Appendix 2. The top ranked outcome at both the surrogate and clinician level was also “care consistent with goals (Appendix 2).”

Table 2.

Top 10 Advance Care Planning Patient-Centered Outcome Constructs Rated by ACP Delphi Panel Experts

| Outcome Constructsa | Domainb | Overall Ranking | Mean Rating (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Care received is consistent with goals | Quality of Care | 1 | 6.71 (0.04) |

| Patient decides on a surrogate | Action | 2 | 6.55 (0.45) |

| Document the surrogate decision maker | Action | 3 | 6.50 (0.11) |

| Discuss values and care preferences with the surrogate | Action | 4 | 6.40 (0.19) |

| Documents and recorded wishes accessible when needed | Action | 5 | 6.27 (0.11) |

| Identify what brings value to patient’s life | Action | 6 | 6.20 (0.12) |

| Medical record contains physician treatment orders (e.g., POLST, code status) when it is clinically appropriate | Action | 7 | 6.13 (0.17) |

| Discuss values and care preferences with clinicians | Action | 8 | 6.08 (0.24) |

| Document values and care preferences | Action | 9 | 6.02 (0.25) |

| Medical record contains advance directive or documentation patient refused | Action | 10 | 6.01 (0.21) |

Because validated measures (i.e., survey instruments or questions) have yet to be standardized for most ACP outcomes, we focused on identifying overarching ACP outcome domains rather than individual questionnaires, quality metrics, or survey questions.

Domain refers to the overarching Outcome Framework Domains in Figure 2.

Table 3.

Delphi Consensus Rankings and Ratings of Advance Care Planning Constructs Overall and by Domaina

| PROCESS OUTCOMES DOMAIN: | Ranking in Sub-Domain | Overall Ranking | Mean Rating (SD) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Behavior Change Constructs | |||

| Readiness to engage in ACP | 1 | 13 | 5.78 (0.12) |

| Knowledge of ACP | 2 | 37 | 5.04 (0.20) |

| Self-efficacy (confidence) about engaging in ACP | 3 | 40 | 5.00 (0.30) |

| Perceptions Constructs | |||

| Anxiety about thinking about death | 1 | 33 | 5.17 (0.26) |

| Patient’s prognostic awareness | 2 | 52 | 4.79 (0.33) |

| Perceived barriers to ACP | 3 | 56 | 4.66 (0.05) |

| Perceived cultural relevance of ACP | 4 | 58 | 4.59 (0.00c) |

| Perceived facilitators to ACP | 5 | 61 | 4.44 (0.03) |

| ACTION OUTCOMES DOMAIN: | Ranking in Sub-Domain | Overall Ranking | Mean Rating (SD) |

| Communication & Documentation | |||

| Surrogate Constructs | |||

| Patient decides on a surrogate | 1 | 2 | 6.55 (0.45) |

| Document the surrogate decision maker | 2 | 3 | 6.50 (0.11) |

| Surrogate agrees to take on roleb | 3 | 12 | 5.78 (0.00) |

| Ask surrogate to take on the role | 4 | 14 | 5.70 (0.20) |

| Inform clinicians about the surrogate | 5 | 23 | 5.46 (0.00) |

| Inform family/friends about the surrogate | 6 | 41 | 4.97 (0.15) |

| Patient decides on amount of flexibility/leeway in decision making to give surrogate | 7 | 45 | 4.90 (0.54) |

| Discuss flexibility with surrogate | 8 | 49 | 4.87 (0.54) |

| Document surrogate flexibility | 9 | 55 | 4.74 (0.49) |

| Review forms which document a surrogate over time | 10 | 57 | 4.64 (0.00) |

| Values and Preferences Constructs | |||

| Discuss values and care preferences with the surrogate | 1 | 4 | 6.40 (0.19) |

| Documents and recorded wishes accessible when neededb | 2 | 5 | 6.27 (0.11) |

| Identify what brings value to patient’s life | 3 | 6 | 6.20 (0.12) |

| Medical record contains physician treatment orders (e.g., POLST, code status) when it is clinically appropriateb | 4 | 7 | 6.13 (0.17) |

| Discuss values and care preferences with clinicians | 5 | 8 | 6.08 (0.24) |

| Document values and care preferences | 6 | 9 | 6.02 (0.25) |

| Medical record contains advance directive or documentation patient refuseda | 7 | 10 | 6.01 (0.21) |

| Identify preferred general scopes of treatment (e.g., aggressive vs. comfort care) | 8 | 24 | 5.44 (0.28) |

| Discuss values and care preferences with family & friends | 9 | 35 | 5.07 (0.14) |

| Congruence between patient’s stated wishes and surrogate’s reports of patient’s wishes | 10 | 36 | 5.04 (0.00) |

| Identify preference for specific life sustaining treatment (e.g., CPR, etc.) | 11 | 38 | 5.03 (0.14) |

| QUALITY OF CARE OUTCOMES DOMAIN: | Ranking in Sub-Domain | Overall Ranking | Mean Rating (SD) |

| Care Consistent w/Goals Constructs | |||

| Care received is consistent with goals | 1 | 1 | 6.71 (0.04) |

| Satisfaction with Care | |||

| Surrogate/family ratings of quality of death and dyingb | 1 | 15 | 5.70 (0.20) |

| Overall satisfaction with medical care | 2 | 34 | 5.10 (0.27) |

| Overall satisfaction with clinician | 3 | 42 | 4.97 (0.30) |

| Perceptions of clinician level of engagement within clinical encounters | 4 | 59 | 4.57 (0.00) |

| Satisfaction with Decision Making | |||

| Decisional conflict | 1 | 30 | 5.28 (0.22) |

| Decisional regret | 2 | 39 | 5.01 (0.30) |

| Decision control preferences, i.e.; control over decision making (may also be a moderator variable) | 3 | 51 | 4.83 (0.17) |

| Satisfaction with Communication | |||

| Clinicians provide prognostic information tailored to patient/family readiness | 1 | 11 | 5.79 (0.32) |

| Rated quality of discussions with clinicians | 2 | 16 | 5.64 (0.24) |

| Clinicians provide recommendations aligned w/patient’s values | 3 | 19 | 5.57 (0.13) |

| Clinicians engage in answering questions | 4 | 27 | 5.31 (0.10) |

| Rated quality of discussions with surrogates | 5 | 32 | 5.23 (0.24) |

| Specific topics included in discussion (e.g., values, treatment preferences etc.) | 6 | 43 | 4.93 (0.28) |

| HEALTHCARE OUTCOMES DOMAIN: | Ranking in Sub-Domain | Overall Ranking | Mean Rating (SD) |

| Health Status and Mental Health | |||

| Depression | 1 | 31 | 5.25 (0.05) |

| Clinician moral distress b | 2 | 46 | 4.90 (0.29) |

| Peace | 3 | 50 | 4.85 (0.21) |

| Self-rated quality of life | 4 | 53 | 4.77 (0.26) |

| Hope | 5 | 60 | 4.45 (0.00) |

| Care Utilization Constructs | |||

| Hospitalization utilizationb | 1 | 17 | 5.63 (0.00) |

| Use of life sustaining treatmentb | 2 | 18 | 5.59 (0.06) |

| Hospice utilizationb | 3 | 20 | 5.52 (0.07) |

| ICU utilizationb | 4 | 21 | 5.51 (0.11) |

| Place of deathb | 5 | 22 | 5.49 (0.23) |

| Overall healthcare expendituresb | 6 | 25 | 5.39 (0.00) |

| Days in hospice before deathb | 7 | 26 | 5.35 (0.14) |

| ER utilizationb | 8 | 28 | 5.30 (0.01) |

| Palliative care utilizationb | 9 | 29 | 5.29 (0.15) |

| Long term care utilization (i.e., nursing home or institutionalizationb | 10 | 44 | 4.92 (0.01) |

| Withdrawal of life sustaining treatmentb | 11 | 48 | 4.89 (0.00) |

| Out of pocket expenses | 12 | 54 | 4.75 (0.34) |

Because validated measures (i.e., survey instruments or questions) have yet to be standardized for most ACP outcomes, we focused on identifying overarching ACP outcome domains rather than individual questionnaires, quality metrics, or survey questions.

All rankings are based on patient-level unit of analysis, except where this is inappropriate. The following constructs were ranked at the Surrogate level: Surrogate agrees to take on the role, Patient died in preferred location, Surrogate/family ratings of quality of death and dying; the Clinician level: Clinician moral distress; and the Healthcare level: Documents and recorded wishes accessible when needed, Medical record contains physician treatment orders (e.g., POLST, code status) when it is clinically appropriate, Medical record contains advance directive or documentation patient refused, and all care utilization constructs, except out of pocket expenses

To reduce response burden, mean ratings from the prior rounds were presented so panelists could easily leave the ratings unchanged, recommend changes, or provide additional comments. A standard deviation of 0.00 means that all panelists agreed with that rating and did not change it in the final round.

Outcome Considerations

Although care consistent with goals was rated as the number one outcome construct, several panelists cautioned that there were difficulties in defining and measuring this construct:

“While this outcome is extremely important, I am not currently aware of an instrument or method to measure this, especially a method that would be amendable to most ACP studies, including quality improvement studies.”

“Goals of care change over time, so in the metric it would be important to specify ‘most recently documented goals match care’.”

“We cannot measure this in a meaningful and consistent way. So you are setting up a dilemma for our field of research, and potentially setting up a policy dilemma as well.”

There were also questions related to feasibility for measures pertaining to subjective assessments or emotional states under Health Status subdomain: “I don’t trust our ability to measure all of these states (hope, peace…) I worry that we won’t be finding reliable, valid measures to obtain these data.”

Many panelists also reported tensions concerning the subdomain of Care Utilization. Although panelists rated it as important with high consensus, many expressed concerns for focusing on utilization to demonstrate ACP success. “I think we have to be careful…not everyone wants to die at home. Some…may desire aggressive LSTs [life sustaining treatments] at the EOL [end of life]… The foremost principle is that people’s preferences are honored.”

DISCUSSION

Advance care planning is an essential process to ensure healthcare is individualized and guided by patient priorities, yet standardized outcomes are lacking. To fill this gap, a large multidisciplinary group of experts created an overarching Organizing Framework of ACP outcome domains and constructs. The panel also prioritized these ACP outcome constructs. The highest domains and constructs. The panel also prioritized ranked outcome was “care consistent with goals” within the Quality of Care domain, although there was considerable caution raised about the challenges in measuring this important outcome.

Several of the ACP outcome constructs, such as documentation of a surrogate, documentation of treatment preferences and care consistent with goals, have been identified in other consensus projects concerning the broader fields of palliative care and hospice.(3, 8, 9, 12–17, 35) This study and the Delphi panel builds on this palliative care and hospice.(3, 8, 9, 12–17, important prior work by creating an Organizing Framework specifically for overarching ACP domains, subdomains and constructs. This framework can be used to organize ACP outcomes and provide important context for future research.

This Delphi also identified the top-rated constructs that researchers or quality improvement programs may consider when evaluating the efficacy of ACP initiatives to standardize and compare ACP outcomes across studies. Additionally, the panel identified other constructs deemed highly important by international ACP experts, such as readiness to engage in ACP, provision of prognostic information by the clinician, and ratings of satisfaction with care and communication. Although other outcome constructs were rated lower (Appendix 2) this does not mean they should not be considered to address specific research hypotheses and patient populations.

Although “care consistent with goals” is listed as an important metric in many of the aforementioned quality indicator initiatives, there is still no standardized, valid or reliable method to measure this outcome, especially across serious illness populations when preferences may vary over time.(17, 35, 36) Care consistent with goals has been variably measured by retrospective chart review matched to the most current (often out-of-date) advance directive on file and/or proxy report.(5–9) Furthermore, assessing this outcome through chart review is hindered by poor documentation of patients’ real-time wishes within health systems.(37) Surveys of family members after death may be a reasonable proxy measure.(17) However, the best timing to ask such questions to obtain reliable responses while not causing distress is unknown. Furthermore, Delphi members commented on issues pertaining to the conceptualization of goals and values, for example, care consistent with goals can pertain to real-time medical care and not just end of life care. Defining the timeframe for this outcome is critical given that ACP interventions may target populations without serious illness for whom care decisions may be years in the future. Furthermore, patient preferences and clinical contexts change over time, and studies have shown that values do not always align with treatment preferences,(38) making precise measurement difficult.(4) For all of these reasons, “care consistent with goals” may never be precisely measured through chart review nor at a population level. This outcome may require real-time assessment from patients and their caregivers, and future studies should determine how best to define and assess this highest rated outcome.

Previous studies have validated individual ACP measures, and systematic reviews concerning ACP have been published.(2, 4, 27, 39–41) This study builds on this work by describing the broad landscape of ACP outcome domains and constructs deemed important by ACP experts, creating an Organizing Framework, and ranking these outcomes for research purposes. However, much additional research is needed. Because validated measures are not available for many of the constructs, rating took place at the overarching domain/construct level rather than focusing on available surveys. The next step should be to develop consensus definitions and to evaluate these outcomes for both validity and feasibility.(12) For researchers and for population health, these outcomes should also be categorized by ease of extraction from administrative data and/or response burden. In some cases, new measures will need to be created and validated. Additional work is also needed to define surrogate- and clinician-level outcome constructs for ACP, to broaden the international applicability of these findings, and finally, patients and surrogates should also rate these constructs.(3)

This study has a number of limitations that may affect the generalizability of our findings. First, although there were many experts represented on the Delphi panel, they were from four disciplines, resided predominantly in the U.S, and included only a few health plan representatives, but no social workers. In addition, this work was focused on ACP research. Outcomes for quality improvement and clinical demonstration projects may differ. Furthermore, self-selection bias and information bias may have occurred as a different cohort of experts from different perspectives (e.g., quality improvement or payers) may have rated these or other outcomes differently. For example, researchers may rate outcomes highly that can demonstrate change in response to an intervention, while health plans may prioritize utilization. Patients and caregivers may also rate the importance of these outcomes differently and should be included in future research. Furthermore, the breadth of the panel and scope of the charge to apply importance ratings to diverse ACP research purposes was intentional, but may explain why some of the constructs were rated highly despite limited feasibility. This may also explain why some ratings may seem counterintuitive, such as the accessibility of documentation being ranked higher than the completion of legal forms. However, the rating differences between the top outcomes were small, and, this does not mean that lower ranked outcomes should not be included for specific studies. In addition, the sheer number of outcome constructs identified by the Delphi panel may have resulted in response fatigue, and the response rate of 62% in Round 3 threatens the validity of our findings. However, 85% of the original Delphi panel completed ratings in the final and fifth Round. As the field of ACP research matures, these ratings and rankings may change over time. Further research is also needed to create standardized definitions of these outcomes and validated questionnaires in the context of differing units of analyses and patient populations.

In summary, a large, multidisciplinary Delphi panel identified an Organizing Framework and rated ACP outcome constructs that define successful patient-centered ACP. This study is an important step to encourage standardization of outcomes used in ACP research and to improve our understanding of the potential impact of ACP initiatives. Still, more research is needed to create standardized operational definitions of these outcome constructs and to identify feasible and validated approaches to measuring them.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This project was unfunded. However, over the course of the unfunded project, Dr. Sudore was supported in part by the following grants: NIH R01AG045043, PCORI-1306-01500, VA HSR&D 11-110-2, American Cancer Society (ACS) #19659, and NIH U24NR014637.

Role of Funders/Sponsors: No funding bodies had a role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, and approval of the manuscript; or decision to submit the manuscript for publication. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs.

In addition to the authors, we would like to acknowledge the following Delphi panel members:

In Australia:

Karen Detering, MD, Austin Hospital, Melbourne

William Silvester, MD, Austin Hospital, Melbourne

In Canada:

The Canadian Researchers at the End of Life Network

Sarah Davison, MD, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta

Carole Robinson, PhD, RN, University of British Columbia, Kelowna, British Columbia

In the United States:

Sangeeta Ahluwalia, PhD, UCLA, Los Angeles, CA

Wendy Anderson, MD, UCSF, San Francisco, CA

Robert Arnold, MD, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA

Anthony Back, MD, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

Marie Bakitas, RN, PhD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL

David Bekelman, MD, University of Colorado, Denver, CO

Rachelle Bernacki, MD, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Harvard, Boston, MA

Susan Block, MD, Dana-Farber Cancer Institute/Harvard, Boston, MA

David Casarett, MD, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA

Jared Chiarchiaro, MD, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA

J. Randall Curtis, MD, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

Jean Cutner, MD, MPH/MSPH, University of Colorado, Denver, CO

J. Nicholas Dionne-Odom, PhD, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Birmingham, AL

Stacy Fischer, MD, University of Colorado, Denver, CO

Laura Gelfman, MD, Mt Sinai, New York, NY

Krista Harrison, PhD, UCSF, San Francisco, CA

Susan Hickman, PhD, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN

Sarah Hooper, JD, UCSF/UC Hastings Consortium on Law, Science & Health Policy, San Francisco, CA

Daniel Johnson, MD, Kaiser Permanente, Denver, CO

Kimberly Johnson, MD, Duke University, Durham, NC

Amy Kelley, MD, Mt. Sinai, New York, NY

Daniel Matlock, MD, University of Colorado, Denver, CO

James Mittelberger, MD, Optum Healthcare, Oakland, CA

Holly Prigerson, PhD, Cornell University, New York NY

Ruth Engelberg, PhD, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

Yael Schenker, MD, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA

Rashmi Sharma, MD, Northwestern University, Chicago, IL

Alex Smith, MD, UCSF, San Francisco, CA

Karen Steinhauser, PhD, Duke University, Durham, NC

Joan Teno, MD, MS, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

Judy Thomas, JD, Coalition for Compassionate Care of California, Sacramento, CA

Alexia Torke, MD, Indiana University, Indianapolis, IN

Elizabeth Vig, MD, University of Washington, Seattle, WA

Angelo Volandes, MD, Harvard University, Boston, MA

Douglas White, MD, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, PA

Appendix 1: All Outcome Constructs bv Domain and Stage in Delphi Study When Added or Deleted

| Domain | Outcome | Original | Conferences | Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 4* | Round 5 | Final |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Process | Readiness to engage in ACP | X | X | |||||

| Process | Knowledge of ACP | X | X | |||||

| Process | Self-efficacy about engaging in ACP | X | X | |||||

| Process | Perceived barriers to ACP | added | X | |||||

| Process | Perceived cultural relevance of ACP | added | X | |||||

| Process | Anxiety about thinking about death | added | X | |||||

| Process | Perceived facilitators to ACP | added | X | |||||

| Process | Motivation to engage in ACP | added | deleted | |||||

| Process | Contemplation about ACP | X | deleted | |||||

| Process | Behaviors that foster change | X | deleted | |||||

| Process | Attitudes about the cons of ACP | X | deleted | |||||

| Process | Attitudes about the pros of ACP | X | deleted | |||||

| Action | Engage in asking providers questions if desired | X | X | |||||

| Action | Discuss values and care preferences with clinicians | X | X | |||||

| Action | Discuss values and care preferences with family & friends | X | X | |||||

| Action | Discuss values and care preferences with the surrogate | X | X | |||||

| Action | Document values and care preferences | X | X | |||||

| Action | Identify preferences for specific life sustaining treatment (e.g., CPR, etc.) | X | X | |||||

| Action | Identify what brings value to patient’s life | X | X | |||||

| Action | Ask surrogate to take on the role | X | X | |||||

| Action | Discuss flexibility with surrogate | X | X | |||||

| Action | Document surrogate flexibility | X | X | |||||

| Action | Document the surrogate decision maker | X | X | |||||

| Action | Inform clinicians about the surrogate | X | X | |||||

| Action | Inform family/friends about the surrogate | X | X | |||||

| Action | Patient decides on a surrogate | X | X | |||||

| Action | Patient decides on amount of flexibility/leeway in decision making to give surrogate | X | X | |||||

| Action | Identify preferred general scopes of treatment (e.g., aggressive versus comfort care) | added | X | |||||

| Action | Medical record contains physician treatment orders (e.g., POLST, code status) when it is clinically appropriate | added | X | |||||

| Action | Clinicians provide recommendations aligned w/patient’s values | added | X | |||||

| Action | Surrogate agrees to take on the role | added | X | |||||

| Action | Congruence between patient’s stated wishes and surrogate’s reports of patient’s wishes | added | X | |||||

| Action | Review forms which document a surrogate over time | added | X | |||||

| Action | Discuss surrogate flexibility with family & friends | X | deleted | |||||

| Action | Reconciles conflicts between family and friends about surrogate flexibility | added | deleted | |||||

| Action | Was an ACP decision aid or toolkit used? | added | deleted | |||||

| Action | Was an ACP facilitator used? | added | deleted | |||||

| Action | Identify health states where I would not want my life prolonged (i.e., worse than death). | X | deleted | |||||

| Action | Engage(d) (or involved) in medical decision making, if desired | added | deleted | |||||

| Action | Identify trade offs about future health states and at what cost | added | deleted | |||||

| Action | Review documented values and preferences over time | added | deleted | |||||

| Action | Surrogate agrees to follow patients’ stated values | added | deleted | |||||

| Action | Surrogate willing/able to communicate with clinicians | added | deleted | |||||

| Action | Surrogate willing/able to make a decision | added | deleted | |||||

| Action | Does the patient lack a suitable surrogate decision maker?a | added | deleted | |||||

| Action | Discuss surrogate flexibility with clinicians | X | deleted | |||||

| Action | Reconciles conflicts between family and friends about preferences | added | deleted | |||||

| Action | Identify where to be cared for (e.g., at home or an institution) | added | deleted | |||||

| Action | Patient decides on an alternative surrogate | added | deleted | |||||

| Action | Reconcile conflicts between family/friends about the surrogate | added | deleted | |||||

| Action | Review documented flexibility for the surrogate over time | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Decision control preferences, i.e., control over decision making | X | X | |||||

| Quality of Care | Clinicians provide prognostic information tailored to patient/family readiness | added | X | |||||

| Quality of Care | Clinicians engage in answering questions | added | X | |||||

| Quality of Care | Overall satisfaction with medical care | added | X | |||||

| Quality of Care | Overall satisfaction with clinician | added | X | |||||

| Quality of Care | Decisional Conflict | added | X | |||||

| Quality of Care | Decisional Regret | added | X | |||||

| Quality of Care | Rated quality of discussions with clinicians | added | X | |||||

| Quality of Care | Rated quality of discussions with surrogates | added | X | |||||

| Quality of Care | Specific topics included in discussion (e.g., values, treatment preferences etc.) | added | X | |||||

| Quality of Care | Care received is consistent with goals | added | X | |||||

| Quality of Care | Documents and recorded wishes are accessible when needed | added | X | |||||

| Quality of Care | Surrogate/family ratings of quality of death and dying | added | X | |||||

| Quality of Care | Perceptions of clinician level of engagement within clinical encounters | added | X | |||||

| Quality of Care | Died in preferred location | added | X | |||||

| Quality of Care | Clinician self-rated job satisfaction | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Surrogate meets emotional needs | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Clinician meets spiritual needs | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Surrogate meets spiritual needs | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Rated time spent in discussions with clinicians | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Rated time spent in discussions with surrogates | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Consistency of preferences over time | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Surrogate feels respected/appreciated by patient | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Decision control preferences for day-to-day medical decisions | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Anticipatory decisional regret | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Clinicians provide (or patients or surrogates report that clinicians provide) options/alternatives | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Clinicians provide recommendation (or patients or surrogates report that clinicians provide) about care options | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Patient/surrogate feels respected by clinician | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Clinician meets caregiving/medical needs | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Knowledge of alternative options | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Knowledge of benefits of options | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Knowledge of risks of options | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Quality rating (or satisfaction) of medical decisions made | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Did patient’s values affect the clinician’s and surrogate’s decision on their behalf? | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Chart review: advance directive/documentation vs. care received | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Did advance directives affect decisions | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Time documentation (AD, physician’s orders, or documented discussions) is available before death/crisis | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Self-rated quality of care | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Patient feels respected by surrogate | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Surrogate meets caregiving/medical needs | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Types of decisions made (about medication, surgery, institution, etc.) | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Ability to tolerate uncertainty in decision making | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Perceptions of the quality of the relationship with clinicians | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Trust in healthcare systema | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Trust in cliniciansa | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Clinician meets emotional needs | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Clinician meets needs defined or prioritized by the patient/surrogate | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Surrogate meets needs defined or prioritized by the patient | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Decision control preferences for life-threatening decision | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | General activation/empowerment within clinical encounters | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Rated quality of discussions with family and friends | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Overall satisfaction with the surrogate | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Did decision making processes (shared or not shared), match patients’/surrogates’ decision control preferences? | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Acceptance of death | added | deleted | |||||

| Quality of Care | Died in preferred location | deleted | ||||||

| Healthcare | Use of life sustaining treatment | X | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Hospice utilization | X | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Hospitalization utilization | X | X | |||||

| Healthcare | ICU utilization | X | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Depression | X | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Medical record contains advance directive or documentation patient refused | added | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Overall healthcare expenditures | added | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Place of death | added | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Days in hospice before death | added | X | |||||

| Healthcare | ER utilization | added | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Palliative Care utilization | added | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Withdrawal of life sustaining treatment | added | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Peace | added | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Self-rated quality of life | added | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Long term care utilization (i.e., nursing home or institutionalization) | added | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Out of pocket expenses | added | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Clinician moral distress | added | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Patient’s prognostic awareness | added | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Hope | added | X | |||||

| Healthcare | Self-reported co-morbidities | added | deleted | |||||

| Healthcare | Complicated grief | added | deleted | |||||

| Healthcare | Medical record contains narrative documentation of goals of care conversations (i.e., patients’ stories describing overall values for medical care). | added | deleted | |||||

| Healthcare | Medical record contains type of treatment preference (i.e., full code, DNR/DNI, artificial nutrition, comfort care) etc. | added | deleted | |||||

| Healthcare | Family coping ability | added | deleted | |||||

| Healthcare | Complicated grief | added | deleted | |||||

| Healthcare | Symptomsa | added | deleted | |||||

| Healthcare | Functional status | added | deleted | |||||

| Healthcare | Calculated prognosis | added | deleted | |||||

| Healthcare | Self rated health status | added | deleted | |||||

| Healthcare | ICU admission | X | deleted | |||||

| Healthcare | Coping ability | added | deleted | |||||

| Healthcare | Anxiety | X | deleted | |||||

| Healthcare | PTSD | added | deleted |

In Round 4 symptoms, trust, and availability of a potential surrogate were deleted due to low ratings and because they were considered to be moderators and/or not associated with ACP outcomes. All the other “deleted” outcome constructs in Round 4 were consolidated into other constructs because they were duplicative

Appendix 2. Delphi Consensus Overall Rankings and Ratings of Advance Care Planning Constructs by Domain3 and All Pertinent Units of Analysisb

| PROCESS OUTCOMES DOMAIN: | Unit of Analysis | Ranking in Sub-Domain | Overall Ranking | Mean Rating (SD) | Median (IQR) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Behavior Change Constructs | |||||

|

| |||||

| Readiness to engage in ACP | Patient | 1 | 13 | 5.78 (0.12) | 5.75 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.70 (0.00) c | 5.70 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.67 (0.05) | 5.66 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Knowledge of ACP | Patient | 2 | 37 | 5.04 (0.20) | 5.00 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.10 (0.00) | 5.10 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.29 (0.11) | 5.27 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Self-efficacy (confidence) about engaging in ACP | Patient | 3 | 40 | 5.00 (0.30) | 4.95 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 4.78 (0.12) | 4.80 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.15 (0.21) | 5.16 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Perceptions Constructs | |||||

|

| |||||

| Anxiety about thinking about death | Patient | 1 | 33 | 5.17 (0.26) | 5.22 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 4.47 (0.25) | 4.51 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 3.88 (0.02) | 3.88 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Patient’s prognostic awareness | Patient | 2 | 52 | 4.79 (0.33) | 4.68 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 4.93 (0.00) | 4.93 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Perceived barriers to ACP | Patient | 3 | 56 | 4.66 (0.05) | 4.66 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 4.84 (0.02) | 4.84 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.04 (0.14) | 5.02 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Perceived cultural relevance of ACP | Patient | 4 | 58 | 4.59 (0.00) 4.55 | 4.59 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | (0.00) | 4.55 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Perceived facilitators to ACP | Patient | 5 | 61 | 4.44 (0.03) | 4.43 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 4.54 (0.00) | 4.54 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 4.77 (0.00) | 4.77 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| ACTION OUTCOMES DOMAIN | Unit of Analysis | Ranking in SubDomain | Overall Ranking | Mean Rating (SD) | Median (IQR) |

| Communication & Documentation | |||||

|

| |||||

| Surrogate Constructs | |||||

|

| |||||

| Patient decides on a surrogate | Patient | 1 | 2 | 6.55 (0.45) | 6.64 (0.00) |

|

| |||||

| Document the surrogate decision maker | Patient | 2 | 3 | 6.50 (0.11) | 6.48 (0.00) |

| Clinician | – | – | 6.43 (0.00) | 6.43 (0.00) | |

| Healthcare | – | – | 6.45 (0.00) | 6.45 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Surrogate agrees to take on role b | Surrogate | 3 | 12 | 5.78 (0.00) | 5.78 (0.00) |

|

| |||||

| Ask surrogate to take on the role | Patient | 4 | 14 | 5.70 (0.20) 5.37 | 5.68 (0.00) |

| Clinician | – | – | (0.00) | 5.37 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Inform clinicians about the surrogate | Patient | 5 | 23 | 5.46 (0.00) | 5.46 (0.00) |

|

| |||||

| Inform family/friends about the surrogate | Patient | 6 | 41 | 4.97 (0.15) 4.71 | 4.95 (0.00) |

| Clinician | – | – | (0.19) | 4.68 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Patient decides on amount of flexibility/leeway in decision making to give surrogate | Patient | 7 | 45 | 4.90 (0.54) | 5.04 (0.00) |

|

| |||||

| Discuss flexibility with surrogate | Patient | 8 | 49 | 4.87 (0.54) 5.10 | 4.96 (0.00) |

| Clinician | – | – | (0.00) | 5.10 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Document surrogate flexibility | Patient | 9 | 55 | 4.74 (0.49) 5.01 | 4.84 (0.00) |

| Clinician | – | – | (0.30) | 5.05 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Review forms which document a surrogate over time | Patient | 10 | 57 | 4.64 (0.00) 4.72 | 4.64 (0.00) |

| Clinician | – | – | (0.00) | 4.72 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Values and Preferences Constructs | |||||

|

| |||||

| Discuss values and care preferences with the surrogate | Patient | 1 | 4 | 6.40 (0.19) 6.16 | 6.34 (0.00) |

| Clinician | – | – | (0.13) | 6.14 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Documents and recorded wishes accessible when neededb | Healthcare | 2 | 5 | 6.27 (0.11) | 6.26 (0.00) |

| Patient | – | – | 6.12 (0.50) | – | |

| Surrogate | – | – | 6.15 (0.00) | 6.15 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 6.12 (0.00) | 6.12 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Identify what brings value to patient’s life | Patient | 3 | 6 | 6.20 (0.12) 6.19 | 6.18 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | (0.00) | 6.19 (0.00) | |||

|

| |||||

| Medical record contains physician treatment orders(e.g., POLST, code status) when it is clinically appropriateb | Healthcare | 4 | 7 | 6.13 (0.17) | 6.16 (0.00) |

|

| |||||

| Discuss values and care preferences with clinicians | Patient | 5 | 8 | 6.08 (0.24) | 6.02 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.67 (0.20) | 5.64 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Document values and care preferences | Patient | 6 | 9 | 6.02 (0.25) | 6.00 (0.00) |

| Clinician | – | – | 6.11 (0.21) | 6.12 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Medical record contains advance directive or documentation patient refused a | Healthcare | 7 | 10 | 6.01 (0.21) | 5.96 (0.00) |

|

| |||||

| Identify preferred general scopes of treatment (e.g., aggressive vs. comfort care) | Patient | 8 | 24 | 5.44 (0.28) | 5.37 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.32 (0.10) | 5.30 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Discuss values and care preferences with family &friends | Patient | 9 | 35 | 5.07 (0.14) | 5.05 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 4.92 (0.00) | 4.92 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Congruence between patient’s stated wishes and surrogate’s reports of patient’s wishes | Patient | 10 | 36 | 5.04 (0.00) | 5.04 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.07 (0.00) | 5.07 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 4.55 (0.00) | 4.55 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Identify preference for specific life sustaining treatment (e.g., CPR, etc.) | Patient | 11 | 38 | 5.03 (0.14) | 5.01 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.00 (0.15) | 4.98 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| QUALITY OF CARE OUTCOMES DOMAIN: | Unit of Analysis | Ranking in Sub-Domain | Overall Ranking | Mean Rating (SD) | Median(IQR) |

|

| |||||

| Care Consistent w/Goals Constructs | |||||

|

| |||||

| Care received is consistent with goals | Patient | 1 | 1 | 6.71 (0.04) | 6.70 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 6.72 (0.00) | 6.72 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 6.56 (0.00) | 6.56 (0.00) | |

| Healthcare | – | – | 6.77 (0.00) | 6.77 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Satisfaction with Care | |||||

|

| |||||

| Surrogate/family ratings of quality of death and dying b | Surrogate | 1 | 15 | 5.70 (0.20) | 5.67 (0.00) |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.81 (0.18) | 5.78 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Overall satisfaction with medical care | Patient | 2 | 34 | 5.10 (0.27) | 5.14 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.17 (0.13) | 5.15 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Overall satisfaction with clinician | Patient | 3 | 42 | 4.97 (0.30) | 4.97 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.09 (0.27) | 5.12 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Perceptions of clinician level of engagement within clinical encounters | Patient | 4 | 59 | 4.57 (0.00) | 4.57 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 4.90 (0.00) | 4.90 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 4.96 (0.00) | 4.96 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Satisfaction with Decision Making | |||||

|

| |||||

| Decisional conflict | Patient | 1 | 30 | 5.28 (0.22) | 5.30 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.32 (0.22) | 5.33 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Decisional regret | Patient | 2 | 39 | 5.01 (0.30) | 5.05 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.29 (0.00) | 5.29 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Decision control preferences, i.e.; control over decision making (may also be a moderator variable) | Patient | 3 | 51 | 4.83 (0.17) | 4.80 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 4.88 (0.17) | 4.86 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Satisfaction with Communication | |||||

|

| |||||

| Clinicians provide prognostic information tailored to patient/family readiness | Patient | 1 | 11 | 5.79 (0.32) | 5.80 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.77 (0.34) | 5.77 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.94 (0.34) | 5.95 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Rated quality of discussions with clinicians | Patient | 2 | 16 | 5.64 (0.24) | 5.59 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.69 (0.33) | 5.61 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Clinicians provide recommendations aligned w/patient’s values | Patient | 3 | 19 | 5.57 (0.13) | 5.53 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.49 (0.21) | 5.43 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.85 (0.11) | 5.82 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Clinicians engage in answering questions | Patient | 4 | 27 | 5.31 (0.10) | 5.30 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.35 (0.17) | 5.32 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.46 (0.15) | 5.44 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Rated quality of discussions with surrogates | Patient | 5 | 32 | 5.23 (0.24) | 5.22 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.60 (0.28) | 5.61 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.15 (0.29) | 5.13 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Specific topics included in discussion (e.g., values, treatment preferences etc.) | Patient | 6 | 43 | 4.93 (0.28) | 4.86 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.01 (0.27) | 4.95 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.17 (0.30) | 5.08 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| HEALTHCARE OUTCOMES DOMAIN: | Unit of Analysis | Ranking in Sub-Domain | Overall Ranking | Mean Rating (SD) | Median (IQR) |

|

| |||||

| Health Status and Mental Health | |||||

|

| |||||

| Depression | Patient | 1 | 31 | 5.25 (0.05) | 5.26 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.38 (0.00) | 5.38 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Clinician moral distress b | Clinician | 2 | 46 | 4.89 (0.00) | 4.89 (0.00) |

|

| |||||

| Peace | Patient | 3 | 50 | 4.85 (0.21) | 4.84 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.05 (0.21) | 5.05 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Self-rated quality of life | Patient | 4 | 53 | 4.77 (0.26) | 4.73 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 4.94 (0.00) | 4.94 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Hope | Patient | 5 | 60 | 4.45 (0.00) | 4.45 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 4.73 (0.00) | 4.73 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 4.66 (0.00) | 4.66 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Care Utilization Constructs | |||||

|

| |||||

| Hospitalization utilizationb | Healthcare | 1 | 17 | 5.63 (0.00) | 5.63 (0.00) |

| Patient | – | – | 5.50 (0.00) | 5.50 (0.00) | |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.40 (0.00) | 5.40 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.49 (0.00) | 5.49 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Use of life sustaining treatment b | Healthcare | 2 | 18 | 5.59 (0.06) | 5.58 (0.00) |

| Patient | – | – | 5.78 (0.03) | 5.77 (0.00) | |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.68 (0.00) | 5.68 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.68 (0.00) | 5.68 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Hospice utilizationb | Healthcare | 3 | 20 | 5.52 (0.07) | 5.50 (0.00) |

| Patient | – | – | 5.55 (0.00) | 5.55 (0.00) | |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.48 (0.00) | 5.48 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.53 (0.00) | 5.53 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| ICU utilizationb | Healthcare | 4 | 21 | 5.51 (0.11) | 5.48 (0.00) |

| Patient | – | – | 5.34 (0.10) | 5.33 (0.00) | |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.26 (0.00) | 5.26 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.44 (0.08) | 5.43 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Place of death b | Healthcare | 5 | 22 | 5.49 (0.23) | 5.51 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.35 (0.20) | 5.38 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.28 (0.19) | 5.31 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Overall healthcare expendituresb | Healthcare | 6 | 25 | 5.39 (0.00) | 5.39 (0.00) |

| Patient | – | – | 5.13 (0.00) | 5.13 (0.00) | |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.06 (0.00) | 5.06 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.35 (0.00) | – | |

|

| |||||

| Days in hospice before deathb | Healthcare | 7 | 26 | 5.35 (0.14) | 5.32 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | – | ||

| Clinician | – | – | – | ||

|

| |||||

| ER utilizationb | Healthcare | 8 | 28 | 5.30 (0.01) | 5.30 (0.00) |

| Patient | – | – | 5.06 (0.00) | 5.06 (0.00) | |

| Surrogate | – | – | 4.97 (0.00) | 4.97 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.10 (0.00) | 5.10 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Palliative care utilizationb | Healthcare | 9 | 29 | 5.29 (0.15) | 5.26 (0.00) |

| Patient | – | – | 5.17 (0.22) | 5.11 (0.00) | |

| Surrogate | – | – | 5.09 (0.00) | 5.09 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 5.08 (0.00) | 5.08 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Long term care utilization (i.e., nursing home or institutionalization b | Healthcare | 10 | 44 | 4.92 (0.01) | 4.92 (0.00) |

| Patient | – | – | 4.46 (0.00) | 4.46 (0.00) | |

| Surrogate | – | – | 4.33 (0.10) | 4.31 (0.00) | |

| Clinician | – | – | 4.09 (0.00) | 4.09 (0.00) | |

|

| |||||

| Withdrawal of life sustaining treatmentb | Clinician | 11 | 48 | 4.89 (0.00) | 4.89 (0.00) |

| Surrogate | – | – | – | ||

|

| |||||

| Out of pocket expenses | Patient | 12 | 54 | 4.75 (0.34) | 4.69 (0.00) |

| Healthcare | – | – | 4.58 (0.00) | 4.58 (0.00) | |

| Surrogate | – | – | 4.72 (0.19) | 4.69 (0.00) | |

Because validated measures (i.e., survey instruments or questions) have yet to be standardized for most ACP outcomes, we focused on identifying overarching ACP outcome domains rather than individual questionnaires, quality metrics, or survey questions.

All rankings are based on patient-level unit of analysis, except where this is inappropriate. The following constructs were ranked at the Surrogate level: Surrogate agrees to take on the role, Patient died in preferred location, Surrogate/family ratings of quality of death and dying; the Clinician level: Clinician moral distress; and the Healthcare level: Documents and recorded wishes accessible when needed, Medical record contains physician treatment orders (e.g., POLST, code status) when it is clinically appropriate, Medical record contains advance directive or documentation patient refused, and all care utilization constructs, except out of pocket expenses

To reduce response burden, mean ratings from the prior rounds were presented so panelists could easily leave the ratings unchanged, recommend changes, or provide additional comments. A standard deviation of 0.00 means that all panelists agreed with that rating and did not change it in the final round.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Author Contributions: Dr. Sudore had full access to all the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Study concept and design: Sudore, You, Heyland, Lum

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: All authors.

Drafting of the manuscript: Sudore, You, Heyland, Lum

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: All authors.

Content analysis: Sudore, You, Heyland, Lum

Obtained funding: non-applicable

Administrative, technical, or material support: All authors.

Study supervision: Sudore

Conflict of Interest Disclosures: Dr. Green is a co-creator of the advance care planning decision aid, Making Your Wishes Known, which was developed for research purposes and is available free of charge. He has financial interest in Vital Decisions, which is developing a commercial version of the program. Dr. Simon is a Physician Consultant in Advance Care Planning and Goals of Care, Alberta Health Services, Calgary Zone. No other disclosures were reported.

References

- 1.Sudore RL, Lum HD, You JJ, et al. Defining Advance Care Planning for Adults: A Consensus Definition from a Multidisciplinary Delphi Panel. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2017 Jan 03; doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.12.331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.IOM Report: Dying in America: Improving Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. 2014 Sep; Accessed July 2016. http://iom.nationalacademies.org/Reports/2014/Dying-In-America-Improving-Quality-and-Honoring-Individual-Preferences-Near-the-End-of-Life.aspx.

- 3.Rietjens AC, Sudore RL, Connolly M, et al. Definition and recommendations for optimal advance care planning: An international consensus. Lancet Oncology. 2017 doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(17)30582-X. in press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sudore RL, Fried TR. Redefining the “planning” in advance care planning: preparing for end-of-life decision making. Annals of internal medicine. 2010 Aug 17;153(4):256–261. doi: 10.1059/0003-4819-153-4-201008170-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Silveira MWW, Piette J. Advance directive completion by elderly Americans: a decade of change. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2014;62(4):4. doi: 10.1111/jgs.12736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Silveira MJ, Kim SY, Langa KM. Advance directives and outcomes of surrogate decision making before death. N Engl J Med. 2010 Apr 1;362(13):1211–1218. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsa0907901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hammes BJ, Rooney BL, Gundrum JD. A comparative, retrospective, observational study of the prevalence, availability, and specificity of advance care plans in a county that implemented an advance care planning microsystem. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2010 Jul;58(7):1249–1255. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02956.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mularski RA, Dy SM, Shugarman LR, et al. A systematic review of measures of end-of-life care and its outcomes. Health services research. 2007 Oct;42(5):1848–1870. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00721.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dy SM, Herr K, Bernacki RE, et al. Methodological Research Priorities in Palliative Care and Hospice Quality Measurement. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2016 Feb;51(2):155–162. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.10.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biondo P, Lee L, Davison S, Simon J, CRIO A. How healthcare systems evaluate their advance care planning initiatives: Results from a systematic review. Palliat Med. 2016;30(8):10. doi: 10.1177/0269216316630883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pope TM. Legal Briefing: Medicare Coverage of Advance Care Planning. J Clin Ethics. 2015 Winter;26(4):361–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Schenck AP, Rokoske FS, Durham DD, Cagle JG, Hanson LC. The PEACE Project: identification of quality measures for hospice and palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2010 Dec;13(12):1451–1459. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2010.0238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorenz KA, Rosenfeld K, Wenger N. Quality indicators for palliative and end-of-life care in vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007 Oct;55(Suppl 2):S318–326. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01338.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dy SM, Lorenz KA, O’Neill SM, et al. Cancer Quality-ASSIST supportive oncology quality indicator set: feasibility, reliability, and validity testing. Cancer. 2010 Jul 01;116(13):3267–3275. doi: 10.1002/cncr.25109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walling AM, Asch SM, Lorenz KA, et al. The quality of care provided to hospitalized patients at the end of life. Archives of internal medicine. 2010 Jun 28;170(12):1057–1063. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Walling AM, Ahluwalia SC, Wenger NS, et al. Palliative Care Quality Indicators for Patients with End-Stage Liver Disease Due to Cirrhosis. Digestive diseases and sciences. 2017 Jan;62(1):84–92. doi: 10.1007/s10620-016-4339-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dy SM, Kiley KB, Ast K, et al. Measuring what matters: top-ranked quality indicators for hospice and palliative care from the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine and Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2015 Apr;49(4):773–781. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2015.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Diamond IR, et al. Defining consensus: a systematic review recommends methodologic criteria for reporting of Delphi studies. Journal of Clinical Epidemiology. 2014 Apr;67(4):401–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2013.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Keeley T, et al. The use of qualitative methods to inform Delphi surveys in core outcome set development. Trials. 2016 May;17(1):230. doi: 10.1186/s13063-016-1356-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones J, Hunter D. Consensus methods for medical and health services research. Bmj. 1995 Aug 5;311(7001):376–380. doi: 10.1136/bmj.311.7001.376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. Journal of Advanced Nuring. 2000 Oct;32(4):1008–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinuff T, Dodek P, You JJ, et al. Improving End-of-Life Communication and Decision Making: The Development of a Conceptual Framework and Quality Indicators. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2015 Jun;49(6):1070–1080. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.12.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Houben CH, Spruit MA, Groenen MT, Wouters EF, Janssen DJ. Efficacy of advance care planning: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association. 2014 Jul;15(7):477–489. doi: 10.1016/j.jamda.2014.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hickman SE, Keevern E, Hammes BJ. Use of the physician orders for life-sustaining treatment program in the clinical setting: a systematic review of the literature. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015 Feb;63(2):341–350. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Covinsky KE, Fuller JD, Yaffe K, et al. Communication and decision-making in seriously ill patients: findings of the SUPPORT project. The Study to Understand Prognoses and Preferences for Outcomes and Risks of Treatments. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2000 May;48(5 Suppl):S187–193. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2000.tb03131.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bravo G, Dubois MF, Wagneur B. Assessing the effectiveness of interventions to promote advance directives among older adults: a systematic review and multi-level analysis. Social science & medicine. 2008 Oct;67(7):1122–1132. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ramsaroop SD, Reid MC, Adelman RD. Completing an advance directive in the primary care setting: what do we need for success? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007 Feb;55(2):277–283. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sudore RL, Knight SJ, McMahan RD, et al. A novel website to prepare diverse older adults for decision making and advance care planning: a pilot study. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2014 Apr;47(4):674–686. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2013.05.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Obeid JS, McGraw CA, Minor BL, et al. Procurement of shared data instruments for Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) J Biomed Inform. 2013 Apr;46(2):259–265. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]