Abstract

Objective

To characterize patterns of care at the end-of-life for children and young adults with life threatening complex chronic conditions (LT-CCCs) and to compare them by LT-CCC type.

Study design

Cross sectional survey of bereaved parents (n=114, response rate 54%) of children with non-cancer, non-cardiac LT-CCCs who received care at a quaternary care children’s hospital and medical record abstraction.

Results

The majority of children with LT-CCCs died in the hospital (62.7%) with over half (53.3%) dying in the intensive care unit. Those with static encephalopathy (AOR 0.19, 95% CI [0.04–0.98]), congenital and chromosomal disorders (AOR 0.28, 95% CI [0.09–0.91]), and pulmonary disorders (AOR 0.08, 95% CI [0.01–0.77]) were significantly less likely to die at home compared with those with CNS progressive disorders. Almost 50% of patients died after withdrawal or withholding of life sustaining therapies, 17.5% died during active resuscitation and 36% died while receiving comfort care only. Mode of death varied widely across LT-CCCs with no patients with pulmonary disorders dying receiving comfort care only compared with 66.7% of those with CNS progressive disorders. A majority of patients had palliative care involvement (79.3%), however, in multivariable analyses, there was distinct variation in receipt of palliative care across LT-CCCs, with patients having CNS static encephalopathy (AOR 0.07, 95% CI [0.01–0.68]) and pulmonary disorders (AOR 0.07, 95% CI [0.01–0.09]) significantly less likely to have palliative care involvement than those with CNS progressive disorders.

Conclusions

Significant differences in patterns of care at end-of-life exist depending upon LT-CCC type. Attention to these patterns is important to ensure equal access to palliative care and targeted improvements in end-of-life care for these populations.

Keywords: Palliative care, Complex Chronic Conditions, end-of-life care, parental perspectives

Improvements in medical expertise and technology have led to a significant reduction in infant and childhood mortality over the past several decades and many more children are now living with life threatening complex chronic conditions (LT-CCCs) such as severe congenital anomalies, metabolic disorders, cystic fibrosis, neurodegenerative diseases and sequelae of extreme prematurity. (1–4) Because of their multisystem diseases, technology dependence, and complex medication regimens, children and young adults with LT-CCCs often require a high level of medical care and technological support, even at end of life (EOL).(5–7) Unsurprisingly, large population studies, including a recent cross national review, demonstrate that the majority of children with LT-CCCs die in the hospital(3,7–9), after prolonged periods of inpatient admission(10) and primarily in an intensive care unit (ICU) setting.(11,12)

In 2003, The Institute of Medicine’s report, When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families, called for more epidemiologic studies documenting the circumstances surrounding deaths during childhood.(13) Since that time, there have been multiple pediatric studies using administrative data and/or characterizing deaths in the inpatient setting. (10,14,1,15,5,12,7,16,17) Additionally, there have been numerous disease-specific studies in cancer(18–23) and congenital heart disease. (24,25) At present, little is known about patterns of care at EOL for children and young adults with LT-CCCs who die across the spectrum of locations and recent research suggests that hospital use for children with LT-CCCs varies considerably condition type (7), which would suggest that patterns of care at the EOL also may differ. Understanding who these children are, where they die and the circumstances surrounding their deaths is necessary for health care systems to ensure the provision of efficient and equal access to palliative care for this population (14) to enhance symptom management, optimize quality of life, help initiate discussions about advance care planning (ACP), aid in discerning patient and family preferences, and to provide bereavement support to their families.(26,27)

Improving knowledge about patterns of care at EOL for children and young adults by LT-CCCs type may identify gaps, inform clinical practice, and ultimately improve the quality of EOL care for these children and their families. Therefore, the primary objective of this study was to characterize clinical characteristics and patterns of care at the EOL care for children and young adults with LT-CCCs by chronic condition type, focusing on conditions less well described in the literature.

Methods

This prospective cross-sectional study is based on a survey of bereaved parents of children and young adults with LT-CCCs. Parents were eligible for participation if: (1) They were English-speaking, (2) resided in North America with accurate contact information, (3) their child received care at Boston Children’s Hospital (BCH) and died between January 2006 and December 2015, (4) at least 12 months had elapsed after their child’s death, and (5) their child did not have cancer or congenital heart disease. To identify children and young adults with LT-CCC’s, we used the definition of Feudtner et al of complex chronic conditions (CCC) defined as a child or young adult from 1 month of age with a medical condition reasonably expected to last at least 12 months (unless death intervenes) and to involve either several different organ systems or 1 system severely enough to require specialty pediatric care and some period of hospitalization in a tertiary care hospital.(10) In this article, we refer to CCC’s as life-threatening because all children with them in our cohort died. LT-CCC’s were then systematically categorized into 5 primary types: central nervous system (CNS) progressive disorders, static encephalopathy, congenital and chromosomal, neuromuscular, and pulmonary disorders, by study investigators (A.O.) using a previously described classification system(28) to identify the predominant LT-CCC. Because these children often have multiple CCCs, in a small number of patients where it was difficult to discern the predominant LT-CCC from charting, two study investigators adjudicated to identify the primary LT-CCC type. Because many young adults with LT-CCCs continue to receive care at pediatric facilities until the middle of their fourth decade of life, we extended the age range of our cohort, including CCC-related deaths from 1 month up to the thirty-fifth birthday. We excluded children with cancer and primary complex congenital heart disease because they likely represent distinct subgroups of LT-CCCs and recent assessments about patterns of care at the EOL exist in the literature. (21,25,29,30)

Bereaved parents were identified through the hospital bereavement committee database which includes patients cared for at BCH who died in the hospital, at home or elsewhere. Eligible parents were sent an introductory letter explaining the purpose of the study and a postage paid opt-out postcard. Three weeks later, a trained study investigator contacted the family by telephone to confirm their desire to participate and determine their preferred method of survey completion (paper or email). Ten days following distribution of the survey, a combined thank-you reminder card was sent to participating parents. Parents who did not return the survey after the reminder card were called twice – once after two weeks and again after four weeks. Parents who declined participation were not further approached. This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board at BCH.

The Survey Caring for Children with Complex Chronic Conditions (5Cs) was adapted from a previously validated instrument, Survey about Caring for Children with Cancer (SCCC), which measured parental perceptions of EOL care for children with cancer(18) and multiple prior studies have used SCCC or an adaptation of this survey(25,29,30). Relevant items were selected and new items related to communication around ACP for children with LT-CCCs were developed de novo on the basis of literature review and the opinions of an advisory board composed of interdisciplinary clinicians and parents of children with LT-CCCs from the Parent Advisory Council at BCH. Cognitive validity, wording, response burden and willingness to participate were then assessed in a sample (n=11) of bereaved parents of children with LT-CCCs. The final survey instrument (5Cs), a semi-structured 183 item questionnaire, includes parental perspectives on: (1) information about the child and their LT-CCC, (2) communication around prognosis following their child’s diagnosis or recognition of serious illness (3) communication and shared decision making around advance care planning, (4) patient and family experience at EOL and time of death, (5) bereavement and family support, (6) family characteristics, (7) parental experience with research participation in this survey. The survey questions and specific survey domains included in this analysis from sections 1, 4, and 6 are detailed in (Table I; available at www.jpeds.com).

Table I.

Source of Data Elements

| Variable Assessed | Variable Source | Survey Question (if applicable) | Novel S5Cs Question | Survey Domains (if applicable) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent age | Survey | Calculated: When did your child die? less What year were you born? | Family characteristics | |

| Parent gender | Survey | What is your gender? [Male, Female, Other] | Family characteristics | |

| Parent race | Survey | Which of the following best describes your racial background? Choose all that apply [American Indian/Alaskan Native, Asian, Black or African American, Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander, White, Other] | Family characteristics | |

| Time in years since child’s death | Survey | Calculated: Date survey completed? less When did your child die? | ||

| English as primary language | Survey | Is English your first language? [Yes, No] | Family characteristics | |

| Parent income | Survey | Please estimate in dollars your total combined family income for the last 12 months of your child’s life. This should include income (before taxes) from all sources, wages, rent from properties, social security, disability and/or veteran’s benefits, unemployment benefits, workman’s compensation, help from relatives (including child payments and alimony) and so on. | X | Family characteristics |

| Parent education level | Survey | What is the highest degree you earned? [Less than high school, High school diploma or equivalent, Associate degree, Bachelor’s degree, Master’s degree, Doctorate/Professional, Other] | Family characteristics | |

| Parent marital status | Survey | Please describe your current marital status? [Never married, Married, Not married but living with partner, Widowed, Divorced, Separated] | Family characteristics | |

| Number of living children | Survey | How many other children do you have? | Family characteristics | |

| Religion | Survey | Please indicate the religious tradition that best describes you [Protestant, Roman Catholic, Jewish, Eastern Orthodox, Hindu, Buddhist, Muslim, Other, None] | Family characteristics | |

| Child gender | Chart review | |||

| Age at death | Chart review | |||

| Child race | Chart review | |||

| Duration of illness | Survey | Calculated: When did your child die? less When was your child diagnosed with this illness/condition? | X | Information about the child and their LT-CCC |

| Insurance type | Chart review | |||

| Primary LT-CCC type | Chart review | |||

| Technology dependence | Chart review | |||

| Hospital admissions | Chart review | |||

| ICU admissions | Chart review | |||

| Hospital length of stay | Chart review | |||

| Palliative care involvement | Survey | Was there involvement of a palliative care or the pediatric advance care team (PACT) during your child’s illness? [Yes, No] | X | Patient and family experience at EOL and time of death |

| Do Not Resuscitate orders (DNR) | Survey | Did you decide that your child should have a DNR order (that is, that life sustaining treatments should not be undertaken) at any time during your child’s illness? [Yes, No] | Patient and family experience at EOL and time of death | |

| Intensive life sustaining therapies in last two days of life | Survey | Were any life sustaining treatments, such as placing a tube in his/her airway, compressing his/her chest, or shocking his/her heart undertaken during the last two days of life? [Yes, No] | X | Patient and family experience at EOL and time of death |

| Location of death | Survey | Where did your child die? [The hospital at where the care was primarily provided (Intensive Care Unit), The hospital at where the care was primarily provided (Inpatient ward), The hospital at where the care was primarily provided (Outpatient Clinic), The hospital at where the care was primarily provided (ED), A hospital that was not where care was primarily provided but where you child was known as a patient, A hospital where your child was not known as a patient, At home, Other] | Patient and family experience at EOL and time of death | |

| Mode of death | Chart review | |||

| Ability to plan location of death | Survey | Were you able to plan in advance the place where your child would be when s/he died? [Yes, No] | Patient and family experience at EOL and time of death |

Trained research assistants abstracted the medical records of all eligible children to confirm the child’s primary diagnosis, date of death, and to determine the child’s age, race, sex, insurance type, Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order status, technology dependence (chronic noninvasive ventilation, tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation, enteral feeding tube, and/or ventriculoperitoneal shunt), and number of hospital admissions, intensive care unit (ICU) admissions, and hospital length of stay in the last year of life. Mode of death was classified by study personnel (E.B.) based upon chart review and describes the categorization of death along the dimensions of intervention in the immediate end-of-life period and/or terminal admission as previously described(31). “Died while receiving comfort care” describes those children who died because a decision was made not to initiate any new life-sustaining interventions during the immediate end of life period or terminal admission. “Died receiving mechanical ventilation and/or CPR” refers to those patients who died while receiving mechanical or non-invasive ventilation or despite active cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Died after withdrawal or withholding of life sustaining therapies” describes patients who had any life-sustaining therapies in place within the immediate end-of-life period or terminal admission that, once withdrawn, resulted in the patient’s death. Duration of illness, any involvement of palliative care and DNR orders at any time during their child’s illness, the ability to plan their child’s location of death, actual location of death and data regarding intensive life sustaining measures in the last two days of life defined as mechanical ventilation, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and/or ECMO, was obtained from the survey instrument (5Cs). The two day window prior to death was selected to identify intensive therapies provided to patients with LT-CCCs at the very end of life. Parent demographics were obtained from the survey for those that completed it, including age, sex, race, number of children, time since child’s death, primary language, income, education level, marital status and religion. The source of all data elements used in this analysis are detailed in (Table I).

Analyses were conducted using Stata statistical software (StataCorp, 2015, College Station, Texas). Pilot sample responses were not included in the final survey analyses. Patient and parent demographics, clinical characteristics, and resource use were described using frequencies and medians with interquartile ranges [IQR] where appropriate. Primary outcomes assessing patterns of care at the EOL included mode of death, location of death, parental ability to plan their child’s location of death, intensive life sustaining therapies in last two days of life, DNR orders, and the receipt of palliative care. To investigate the association between LT-CCC type and the outcomes of interest, analyses were conducted using chi-square and Fisher exact tests. Multivariable logistic regression was then used to assess the associations between primary outcomes and LT-CCC type with CNS progressive as the reference group. The CNS progressive group was chosen as the reference group as they tend to have more predictable clinical course than other LT-CCC types with gradual decline over a long period of time. Potential confounders (sex, race, technology dependence, distance of the child’s home from the hospital and insurance) were chosen a priori as well as significant predictors (P < .1; age) for model inclusion. Factors that were found to be non-significant or were not appreciable confounders of associations (insurance and distance of the child’s home to the hospital) were removed to obtain the final model with results reported as adjusted odds ratios (AOR [95% CIs]).

Results

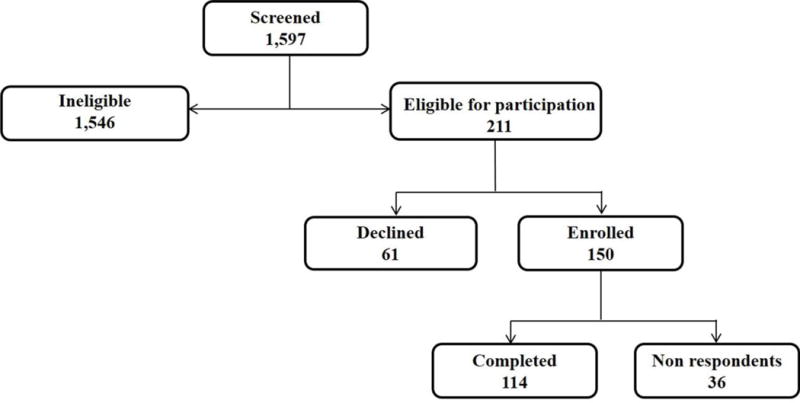

Of the 1,597 patients screened, 211 were eligible for participation. Of those 211 invited to participate, 61 parents (29%) declined, 36 parents (17%) did not respond, and 114 parents completed the survey, yielding a 54% participation rate (Figure; available at www.jpeds.com). Demographics of parents that participated in the survey are detailed in Table II. Parents were primarily female (81.9%) with a median age of 47.5 years [IOR, 40–57]. A majority of parents were White (82.5%), married (80.0%), and Christian (62.1%) with at least some college education (83.8%). Parents completed the survey a median of 3.9 years after the death of their child.

Figure.

Online Consort Diagram for Caring for Children with Complex Chronic Conditions (5Cs) Survey Enrollment

Table II.

Parent Demographics

| N=114 | |

|---|---|

| Age in years at child’s death [median (IQR)] | 47.5 (40–57) |

| Female [n (%)] | 86(81.9) |

| White race [n (%)] | 94 (82.5) |

| Time in years since child’s death [median (IQR)] | 3.9 (2.1–6.5) |

| English as primary language [n (%)] | 101 (94.4) |

| Income in USD [median (IQR)] | $85,000 (50,000–125,000) |

| Education level [n (%)] | |

| Less than high school | 2 (1.9) |

| High school | 15 (14.3) |

| At least some college | 56 (53.3) |

| Graduate degree | 32 (30.5) |

| Marital status at time of child’s death [n (%)] | |

| Single | 5 (4.8) |

| Married/living with partner | 84 (80.0) |

| Divorced | 14 (13.3) |

| Widowed | 2 (1.9) |

| Deceased child was only child [n (%)] | 14 (13.5) |

| Religion [n (%)] | |

| Christian | 64 (62.1) |

| Jewish | 5 (4.9) |

| Muslim | 3 (2.9) |

| Other | 17 (16.5) |

| No religion identified | 14 (13.6) |

Demographics and clinical characteristics of deceased children and young adults with LT-CCCs are detailed in Table III. Those with LT-CCCs were primarily White (77.2%) with a median age at death of 10.5 years, ranging from 8 months to 35 years of age. Children with congenital and chromosomal disorders (38.6%) such as Trisomy 21 or congenital diaphragmatic hernia comprised the largest subset with LT-CCCs, followed by those with CNS progressive disorders (37.6%) such as a mucopolysaccharioses or Retts Disease. Approximately 17% had static encephalopathy and the remaining had either neuromuscular disease (11.4%) such as Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy or pulmonary disorders (9.7%), primarily Cystic Fibrosis. Seventy-five percent of patients in our cohort had chronic technology dependence with enteral feeding tubes (67.5%) and chronic respiratory technology (50%) such as non-invasive positive pressure ventilation common. Median duration of illness prior to death was 6.2 years [IQR, 0.8–17.8]. Children and young adults with LT-CCCs had a median of 1 hospital admission in the last year of life with a median hospital length of stay of 17.7 days [IQR, 2.5–54.8].

Table III.

Patient demographics and clinical characteristics

| N = 114 | |

|---|---|

| Female [n (%)] | 64 (56.1) |

| Age at Death in years [median (IQR)] | 10.53 (1.66–20.64) |

| White race [n (%)] | 88 (77.2) |

| Duration of illness in years [median (IQR)] | 6.2 (0.75–17.8) |

| Insurance type [n (%)] | |

| Private Insurance | 38 (36.2) |

| Government | 29 (27.6) |

| Private Insurance + Government | 37 (35.2) |

| Self-Pay | 1 (1.0) |

| Primary Diagnosis [n (%)] | |

| CNS progressive | 27 (23.7) |

| Static encephalopathy | 19 (16.7) |

| Congenital and chromosomal | 44 (38.6) |

| Neuromuscular | 13 (11.4) |

| Pulmonary | 11 (9.7) |

| Technology Dependence | 85 (74.6) |

| Enteral feeding tube [n (%)] | 77 (67.5) |

| Chronic respiratory technology [n (%)] | 57 (50.0) |

| Ventriculoperitoneal shunt [n (%)] | 12 (10.5) |

| Hospital admissions last year of life [median (IQR)] | 1 (1–3) |

| ICU admissions last year of life [median (IQR)] | 1 (0–2) |

| Hospital length of stay in last year of life, days [median (IQR)] | 17.7 (2.5–54.8) |

Children of non-respondents (n=36) were less likely to be of White race (56 % vs 77 %; p=0.01) and to have palliative care involvement (61% vs 79%; p=0.03). There were no significant differences between children whose parents participated in the study and those of non-respondents with respect to age, sex, insurance type, technology dependence, time since death, mode of death, the presence of DNR orders, or primary LT-CCC groups.

Patterns of Care at End of Life by LT-CCC Type

Patterns of care at the EOL for children and young adults with LT-CCCs are displayed in Table IV. The majority of patients died in the hospital (62.7%) with over half (53.3%) dying in the ICU. Those with CNS progressive disorders were more likely to die at home, and those with static encephalopathy, congenital and chromosomal disorders, neuromuscular disease and pulmonary disorders were more likely to die in the hospital. 46.5% of patients died after withdrawal or withholding of life sustaining therapies, 17.5% died during active resuscitation with new mechanical ventilation or CPR and 36% died while receiving comfort care only. There was wide variation across the five primary LT-CCC types with no patients with pulmonary disorders dying with comfort care only compared with 66.7% of those with CNS progressive disorders. Half of the bereaved parents surveyed reported that they were able to plan their child’s location of death, with wide variation between LT-CCCs types. For example, parents of children with CNS progressive disorders reported being able to plan their child’s location of death 87.0% of the time and those with pulmonary disorders (30%) and congenital and chromosomal disorders (40.5%) were able to plan their child’s location of death less than half the time. A little over a quarter of patients (27.9%) received intensive life sustaining therapies such as mechanical ventilation or CPR in the last two days of life and this was more prominent in patients with pulmonary disorders (45.5%), congenital and chromosomal disorders (38.1%) and static encephalopathy (33.3%). There were no significant differences between LT-CCCs groups regarding the presence of DNR orders (62.5%). A majority of patients in our cohort had a palliative care consult (79.3%). Receipt of palliative care varied across groups with patients having CNS progressive disorders reporting the highest rates of palliative care involvement (96.0%) compared with those with static encephalopathy and pulmonary disorders (62.5, 70.0%).

Table IV.

Patterns of Care at End of Life by Life-Threatening Complex Chronic Condition Type

| All N=114 |

CNS progressive N=27 |

Static encephalopathy N=19 |

Congenital and chromosomal N=44 |

Neuromuscular N=13 |

Pulmonary N=11 |

P-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any palliative care involvement | 84 (79.3) | 24 (96.0) | 10 (62.5) | 33 (78.6) | 10 (76.9) | 7 (70.0) | 0.065 |

| Any Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) orders | 65 (62.5) | 20 (87.0) | 8 (53.3) | 26 (59.1) | 6 (50.0) | 5 (50.0) | 0.064 |

| Intensive life sustaining therapies in last 2 days of life | 29 (27.9) | 1 (4.4) | 5 (33.3) | 16 (38.1) | 2 (15.4) | 5 (45.5) | 0.011 |

| Location of death | |||||||

| ICU | 57 (53.3) | 9 (39.1) | 9 (56.3) | 25 (56.8) | 5 (38.5) | 9 (81.8) | |

| Hospital ward or Emergency room | 10 (9.4) | 1 (4.4) | 1 (6.25) | 6 (13.6) | 2 (15.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Home | 32 (29.9) | 13 (56.5) | 3 (18.8) | 10 (22.7) | 5 (38.5) | 1 (9.09) | 0.07 |

| Other | 8 (7.5) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (18.8) | 3 (6.8) | 1 (7.7) | 1 (9.09) | |

| Mode of death | |||||||

| Died while receiving comfort care | 41 (36.0) | 18 (66.7) | 4 (21.1) | 14 (31.8) | 5 (38.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Died receiving mechanical ventilation and/or CPR | 20 (17.5) | 1 (3.7) | 4 (21.1) | 11 (25.0) | 3 (23.1) | 1 (9.1) | <0.001 |

| Died after withdrawal or withholding of life sustaining therapies | 53 (46.5) | 8 (29.6) | 11 (57.9) | 19 (43.2) | 5 (38.5) | 10 (90.9) | |

| Ability to plan child’s location of death | 52 (50.5) | 16 (72.7) | 9 (56.3) | 17 (40.5) | 7 (53.9) | 3 (30.0) | <0.001 |

Associations were assessed between life-threatening complex chronic condition types using chi-square and fisher’s exact tests

In multivariable models (Table V) compared with those with CNS progressive disorders, those with static encephalopathy were significantly less likely to die receiving comfort care (AOR 0.13, 95% CI [0.03–0.55]), die at home (AOR 0.16, 95% CI [0.03–0.81]), have DNR orders in place (AOR 0.19, 95% CI [0.04–0.93]) or have palliative care involvement (AOR 0.07, 95% CI [0.01–0.68]).

Table V.

Adjusted Patterns of Care at End of Life by Life-Threatening Complex Chronic Condition Type

| Static Encephalopathy | Congenital & Chromosomal | Neuromuscular | Pulmonary | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | AOR | 95% CI | |

| Any palliative care involvement | 0.07 | 0.01–0.68 | 0.16 | 0.02–1.48 | 0.14 | 0.01–1.64 | 0.07 | 0.01–0.90 |

| Any Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) orders | 0.19 | 0.04–0.93 | 0.21 | 0.05–0.82 | 0.14 | 0.03–0.79 | 0.17 | 0.03–1.04 |

| Intensive life sustaining therapies in last 2 days of life | 10.04 | 0.97–103.59 | 13.62 | 1.62–114.59 | 4.05 | 0.31–52.69 | 11.92 | 1.11–127.64 |

| Location of death | ||||||||

| Hospital (ICU) | 1.98 | 0.51–7.60 | 2.09 | 0.72–6.01 | 1.02 | 0.24–4.32 | 6.82 | 1.12–41.47 |

| Hospital (non-ICU) | 1.51 | 0.78–29.21 | 2.91 | 0.32–26.76 | 6.39 | 0.45–90.27 | – | – |

| Home | 0.16 | 0.03–0.81 | 0.23 | 0.07–0.72 | 0.4 | 0.09–1.74 | 0.08 | 0.01–0.77 |

| Other | 1.73 | 0.14–21.18 | 0.58 | 0.04–7.55 | 0.58 | 0.03–12.50 | – | – |

| Mode of death | ||||||||

| Comfort Care | 0.13 | 0.03–0.55 | 0.22 | 0.08–0.62 | 0.32 | 0.08–1.32 | – | – |

| Died receiving mechanical ventilation and/or CPR | 6.11 | 0.61–61.61 | 8.57 | 1.02–71.86 | 7.25 | 0.63–82.34 | 1.91 | 0.10–35.04 |

| Died after withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining interventions | 3.37 | 0.96–11.84 | 1.92 | 0.68–5.41 | 1.48 | 0.36–6.12 | 23.16 | 2.42–221.35 |

| Ability to plan location of death | 0.53 | 0.12–2.23 | 0.22 | 0.07–0.74 | 0.41 | 0.09–1.90 | 0.17 | 0.03–0.99 |

The life-threatening complex chronic condition reference group is CNS progressive disorders.

Binary outcomes were assessed using logistic regression and all analyses were adjusted for age at death, gender, race, technology dependence

Children with congenital and chromosomal disorders were 13-fold as likely to receive intensive life sustaining therapies in last 2 days of life (AOR 13.62, 95% CI [1.62–114.59]) compared with those with CNS progressive disorders, and significantly less likely to die while receiving comfort care (AOR 0.22, 95% CI [0.08–0.62]), die at home (AOR 0.23, 95% CI [0.07–0.72]), or have DNR orders in place (AOR 0.21, 95% CI [0.05–0.82]). Parents of those with congenital and chromosomal disorders were also significantly less likely to be able to plan their child’s location of death compared with those with CNS progressive disorders (AOR 0.22, 95% CI [0.07–0.74]).

Those with neuromuscular disorders were significantly less likely to have DNR orders than CNS progressive disorders (AOR 0.14, 95% CI [0.03–0.79]) but there were no other significant differences between the two populations with respect to location of death, mode of death, receipt of intensive life sustaining measures in the last 2 days of life, palliative care, or the parental ability to plan their child’s location of death.

Lastly, children with pulmonary disorders were significantly more likely to die after withdrawal or withholding of life sustaining interventions than those CNS progressive disorders (AOR 23.16, 95% CI [2.42–221.35]), 12-fold as likely to receive life sustaining therapies in last two days of life (AOR 11.92, 95% CI [1.11–127.64]), and significantly less likely to receive a palliative care consult (AOR 0.07, 95% CI [0.01–0.90]). Parents of those with pulmonary disorders were also significantly less likely to have the ability to plan their child’s location of death (AOR 0.17, 95% CI [0.03–0.99]) than those with CNS progressive disorders with a 6-fold likelihood (AOR 6.82, 95% CI [1.12–41.47]) of dying in the ICU.

Discussion

It has been reported that children and young adults with LT-CCCs often receive their EOL care in the inpatient hospital setting with intensive life-sustaining medical therapies common prior to death, which generally occurs after withdrawal or withholding of those life-sustaining therapies. (1,31–33) This study supports these findings for a majority of children and young adults with LT-CCCs, but provides new insight into important differences in patterns of EOL care across LT-CCC types. Specifically, for patients cared for at our large quaternary care medical center, location of death, mode of death, parental ability to plan their child’s location of death, the presence of intensive life sustaining therapies in the last 2 days of life, DNR orders and the receipt of palliative care all differed significantly by LT-CCCs type. In our cohort, more than half of children and young adults with pulmonary disorders, static encephalopathy, and congenital and chromosomal disorders died in the ICU compared with those with CNS progressive or neuromuscular disorders, who were more likely to die at home. These patients were also significantly more likely to die after withdrawal or withholding of life-sustaining therapies or during active resuscitation when compared with patients with CNS progressive disorders, who were more likely to die receiving comfort care.

Although the overall receipt of palliative care for children and young adults with LT-CCCs was high in this study (79.3%) compared with published literature describing deaths in the general pediatric population (17,26), we noted important differences between LT-CCCs groups with respect to the receipt of palliative care. Importantly, children and young adults with pulmonary disorders and static encephalopathy were significantly less likely to have palliative care at any time during their illness, compared with those with CNS progressive and neuromuscular disorders. In addition, and perhaps related to this decreased incidence of palliative care involvement, parents of children with pulmonary disorders and congenital and chromosomal disorders were more likely to be unable to plan their child’s location of death, which has been identified as a superior proxy for high quality EOL care than actual location of death.(19)

Children and young adults with complex chronic conditions have lifelong, life-threatening conditions and for many, early death is an inevitable outcome of their disease process; however, differences exist with respect to their illness trajectories that may influence the distinct patterns of care at EOL observed in this study. Published data suggest that pediatric patients who die typically experience one of four different trajectories of illness: sudden death (eg, trauma), a steady inexorable decline (e.g., cancer, neurodegenerative disorders, and neuromuscular disease), fluctuating decline (e.g., progressive diseases with intermittent crises such as cystic fibrosis), and constant medical fragility (e.g., static encephalopathy predisposing to crises due to infections).(34) It is plausible that these distinct illness trajectories and specifically the greater prognostic uncertainty commonly observed in those with fluctuating decline and constant medical fragility, result in different barriers to palliative care involvement, advance care planning and ultimately observed EOL care patterns. For example, children and young adults with static encephalopathy often have medical fragility resulting in unpredictable life-threatening crises interspersed with periods of stability, making it difficult to determine the ideal time for palliative care involvement and advance care planning (35) for parents and providers alike. This phenomenon has been described in the adult patients with chronic heart failure, who despite similar disease burden, receive less palliative care consultation than those with cancer due to the cyclic course of disease which makes determination of the appropriate timing of palliative care challenging. (36) Many patients with cystic fibrosis, on the other hand, have known that they have a life-limiting disease for the majority of their lives and barriers to palliative care involvement and advance care planning in this case may include the hope offered by transplant and new therapies(37).

Despite differences in the trajectory of LT-CCCs, all of these patients and their families could benefit from being offered earlier involvement of palliative care services to address symptom management, optimize quality of life, facilitate advance care planning discussions, ensure that medical care occurs in concordance with patient and family goals and values, and to provide bereavement support. (26,38,39) The literature supports the benefits of palliative care with children and young adults who receive palliative care services undergoing fewer procedures, having improved documentation of pain management, shorter length of inpatient stay, and lower daily charges during their terminal hospitalization. (38,26,23,17) The impact of palliative care is mirrored in the adult population where studies demonstrate greater satisfaction with patients’ care experience, providers’ communication, and lower total health care costs at the EOL (40–42) in patients receiving palliative care. These benefits also extend to chronic heart failure, where despite prognostic uncertainty, a recent, randomized control trial of a palliative care intervention demonstrated consistently greater benefits in quality of life, anxiety, depression, and spiritual well-being in the palliative care arm compared with usual care.(36) Unfortunately, despite this compelling evidence, studies still show that over half of parents of children with life-threatening illness indicated that the opportunity to participate in advance care planning and to plan their child’s EOL care was a poorly met need.(43) As a result, the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) endorsed the concurrent use of palliative care and curative care for children with a life-threatening illness.(44) This statement was reaffirmed and expanded in 2013 by the AAP, which now strongly recommends the integration of palliative care into the medical home of children with life-threatening conditions from the moment of diagnosis and throughout the illness course. (45)

Our analysis was nevertheless limited in several ways. First, the number of children in certain LT-CCCs subcategories was small, warranting some caution in interpretation of the percentages. In addition, the study relies, in part, on recall from bereaved parents which may not accurately reflect the actual experience of their child; however, this is an accepted standard in the pediatric literature and for this population. (45,18,30,25) This study also describes the experience at a single, large, quaternary care children’s hospital with a well-established palliative care program, which may explain the high rate of palliative care involvement among our patients and influence generalizability, although a majority of children with LT-CCCs in this country are cared for at large centers. Of note, the palliative care program at Boston Children’s Hospital has been in place since 1997 and is comprised of an interdisciplinary team which provides services at the hospital, outpatient setting and in the community. Additionally, because we did not collect information about timing or frequency of palliative care involvement, we do not know the extent to which these factors influenced observed patterns of care at EOL and future studies should include more detail about palliative care involvement. Finally, selection bias may limit our findings, as it is possible that parent participants may report systematically different EOL experiences for their children than non-participants. Moreover, the lack of significant representation of participants with racial, ethnic, sex and socioeconomic diversity may also influence generalizability. There are several small studies which suggest there may be differences between perceptions of care at EOL (47) and preferred place of death (48) by parent sex, as well as racial and cultural factors which influence the motivation to speak about advance care planning and death in general (49), thus the replication of our findings in a more diverse population is warranted. However, messages about tailoring EOL care to individual children and families with LT-CCCs and ensuring access to palliative care for all families that desire it should be considered as important among populations who have not been well studied.

Despite these limitations, the design of this study allowed us to survey a large number of bereaved parents of children and young adults with LT-CCCs, characterize patterns of care at the EOL for this population, and to identify vulnerable populations with variable receipt of palliative care. Although this study confirms that most children with LT-CCCs spend their last days in an acute care setting, the literature suggests that many parents prefer their child die at home(50) with preferences dependent upon experiences of care, and in-hospital death preferred if community resources to care for the child at home are limited.(17,26,35) Moreover, recent data suggest that the ability to plan a child’s location of death, as opposed to the actual location of death, may be more important to parents of children with life-threatening illness (19) as is a focus on factors that positively influence the experience of EOL care, regardless of location.(51) This study also demonstrates that intensive life-sustaining measures continue to be a part of care at the EOL for many children with LT-CCCs and, at present, it is unclear whether this is concordant with a family’s preferences.

Although there is no correct choice for the style and location of EOL care for all children and young adults with LT-CCCs, this study has identified differences in care between LT-CCC types that may profoundly impact the EOL experiences for these patients and their families. Future studies are needed to quantify the added value of palliative care involvement in these populations, to determine the proportion of in-hospital deaths that are consistent with well-informed family goals and values, and to examine whether children and young adults with LT-CCCs who receive high intensity EOL care experience high suffering or poor quality of life. This study provides much needed information about the nature of care that children and young adults with LT-CCCs receive prior to their deaths. Additionally, the study identifies potential opportunities to improve the quality of EOL care for these children by tailoring EOL care to individual patients and families, and ensuring access to palliative care for all patients with LT-CCCs who desire it.

Acknowledgments

Supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (K12 HS 22986-02): Mentored Career Development in Child and Family Centered Outcomes Research, funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Abbreviations

- CCC

Complex chronic condition

- LT-CCCs

Life threatening complex chronic conditions

- ICU

Intensive care unit

- EOL

End of life

- ACP

Advance care planning

- CNS

Central nervous system

- 5Cs

Caring for Children with Complex Chronic Conditions Survey

- SCCC

Survey about Caring for Children with Cancer

- DNR

Do Not Resuscitate

- AAP

American Academy of Pediatrics

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Reprints: No reprints

References

- 1.Ramnarayan P, Craig F, Petros A, Pierce C. Characteristics of deaths occurring in hospitalised children: changing trends. J Med Ethics. 2007;33(5):255–60. doi: 10.1136/jme.2005.015768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Connell FA. Pediatric Deaths Attributable to Complex Chronic Conditions: A Population-Based Study of Washington State, 1980–1997. Pediatrics. 2000 Jul 1;106(Supplement 1):205–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Feudtner C, Hays RM, Haynes G, Geyer JR, Neff JM, Koepsell TD. Deaths attributed to pediatric complex chronic conditions: national trends and implications for supportive care services. Pediatrics. 2001;107(6):e99–e99. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.e99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cohen E, Patel H. Responding to the rising number of children living with complex chronic conditions. Can Med Assoc J. 2014 Nov 4;186(16):1199–200. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.141036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lindley LC, Lyon ME. A Profile of Children with Complex Chronic Conditions at End of Life among Medicaid Beneficiaries: Implications for Health Care Reform. J Palliat Med. 2013 Nov;16(11):1388. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Srivastava R, Stone BL, Murphy NA. Hospitalist Care of the Medically Complex Child. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2005 Aug;52(4):1165–87. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2005.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ananth P, Melvin P, Feudtner C, Wolfe J, Berry JG. Hospital Use in the Last Year of Life for Children With Life-Threatening Complex Chronic Conditions. Pediatrics. 2015 Nov;136(5):938–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-0260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Håkanson C, Öhlén J, Kreicbergs U, Cardenas-Turanzas M, Wilson DM, Loucka M, et al. Place of death of children with complex chronic conditions: cross-national study of 11 countries. Eur J Pediatr. 2017 Jan;9:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s00431-016-2837-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Feudtner C, Hays RM, Haynes G, Geyer JR, Neff JM, Koepsell TD. Deaths Attributed to Pediatric Complex Chronic Conditions: National Trends and Implications for Supportive Care Services. Pediatrics. 2001 Jun 1;107(6):e99–e99. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.e99. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feudtner C, Christakis DA, Zimmerman FJ, Muldoon JH, Neff JM, Koepsell TD. Characteristics of deaths occurring in children’s hospitals: implications for supportive care services. Pediatrics. 2002;109(5):887–93. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.5.887. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Curtis JR. Communicating about end-of-life care with patients and families in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Clin. 2004;20(3):363–80. doi: 10.1016/j.ccc.2004.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burns JP, Sellers DE, Meyer EC, Lewis-Newby M, Truog RD. Epidemiology of death in the PICU at five U.S. teaching hospitals*. Crit Care Med. 2014 Sep;42(9):2101–8. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000000498. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Medicine I of When Children Die: Improving Palliative and End-of-Life Care for Children and Their Families–Summary [Internet] 1969 [cited 2017 Mar 8]. Available from: https://www.nap.edu/catalog/10845/when-children-die-improving-palliative-and-end-of-life-care.

- 14.Brandon D, Docherty SL, Thorpe J. Infant and child deaths in acute care settings: implications for palliative care. J Palliat Med. 2007 Aug;10(4):910–8. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2006.0236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Siden H, Miller M, Straatman L, Omesi L, Tucker T, Collins J. A report on location of death in paediatric palliative care between home, hospice and hospital. Palliat Med. 2008 Oct;22(7):831–4. doi: 10.1177/0269216308096527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meert KL, Keele L, Morrison W, Berg RA, Dalton H, Newth CJL, et al. End-of-Life Practices Among Tertiary Care PICUs in the United States: A Multicenter Study. Pediatr Crit Care Med J Soc Crit Care Med World Fed Pediatr Intensive Crit Care Soc. 2015 Sep;16(7):e231–238. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osenga K, Postier A, Dreyfus J, Foster L, Teeple W, Friedrichsdorf SJ. A Comparison of Circumstances at the End of Life in a Hospital Setting for Children With Palliative Care Involvement Versus Those Without. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2016 Nov;52(5):673–80. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2016.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wolfe J, Klar N, Grier HE, Duncan J, Salem-Schatz S, Emanuel EJ, et al. Understanding of prognosis among parents of children who died of cancer: impact on treatment goals and integration of palliative care. Jama. 2000;284(19):2469–75. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.19.2469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dussel V, Kreicbergs U, Hilden JM, Watterson J, Moore C, Turner BG, et al. Looking beyond where children die: determinants and effects of planning a child’s location of death. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2009 Jan;37(1):33–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2007.12.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Keim-Malpass J, Erickson JM, Malpass HC. End-of-Life Care Characteristics for Young Adults with Cancer Who Die in the Hospital. J Palliat Med. 2014 Jun 25;17(12):1359–64. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2013.0661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kassam A, Skiadaresis J, Alexander S, Wolfe J. Parent and clinician preferences for location of end-of-life care: home, hospital or freestanding hospice? Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2014 May;61(5):859–64. doi: 10.1002/pbc.24872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Brock KE, Steineck A, Twist CJ. Trends in End-of-Life Care in Pediatric Hematology, Oncology, and Stem Cell Transplant Patients. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2016 Mar;63(3):516–22. doi: 10.1002/pbc.25822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ullrich CK, Lehmann L, London WB, Guo D, Sridharan M, Koch R, et al. End-of-Life Care Patterns Associated with Pediatric Palliative Care among Children Who Underwent Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplant. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. J Am Soc Blood Marrow Transplant. 2016 Jun;22(6):1049–55. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2016.02.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morell E, Wolfe J, Scheurer M, Thiagarajan R, Morin C, Beke DM, et al. Patterns of Care at End of Life in Children With Advanced Heart Disease. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2012 Aug;166(8):745–8. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2011.1829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blume ED, Balkin EM, Aiyagari R, Ziniel S, Beke DM, Thiagarajan R, et al. Parental perspectives on suffering and quality of life at end-of-life in children with advanced heart disease: an exploratory study*. Pediatr Crit Care Med. 2014;15(4):336–42. doi: 10.1097/PCC.0000000000000072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Keele L, Keenan HT, Sheetz J, Bratton SL. Differences in characteristics of dying children who receive and do not receive palliative care. Pediatrics. 2013 Jul;132(1):72–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-0470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burns KH, Casey PH, Lyle RE, Bird TM, Fussell JJ, Robbins JM. Increasing prevalence of medically complex children in US hospitals. Pediatrics. 2010 Oct;126(4):638–46. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunt A, Hacking S. The BiG study for life-limited children and their families. 2013 [cited 2017 May 2]; Available from: http://clok.uclan.ac.uk/8951/2/TfSL_The_Big_Study_Final_Research_Report__WEB_.pdf.

- 29.Wolfe J, Hammel JF, Edwards KE, Duncan J, Comeau M, Breyer J, et al. Easing of suffering in children with cancer at the end of life: is care changing? J Clin Oncol. 2008;26(10):1717–23. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.0277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mack JW, Hilden JM, Watterson J, Moore C, Turner B, Grier HE, et al. Parent and physician perspectives on quality of care at the end of life in children with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23(36):9155–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fontana MS, Farrell C, Gauvin F, Lacroix J, Janvier A. Modes of death in pediatrics: differences in the ethical approach in neonatal and pediatric patients. J Pediatr. 2013 Jun;162(6):1107–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2012.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feudtner C, Silveira MJ, Christakis DA. Where do children with complex chronic conditions die? Patterns in Washington State, 1980–1998. Pediatrics. 2002 Apr;109(4):656–60. doi: 10.1542/peds.109.4.656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chavoshi N, Miller T, Siden H. Mortality trends for pediatric life-threatening conditions. Am J Hosp Palliat Care. 2015 Jun;32(4):464–9. doi: 10.1177/1049909114524476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Issues C on ADAKE of L, Medicine I of Pediatric End-of-Life and Palliative Care: Epidemiology and Health Service Use [Internet] National Academies Press (US); 2015. [cited 2017 May 9]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK285690/ [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kang TI, Munson D, Hwang J, Feudtner C. Integration of Palliative Care Into the Care of Children With Serious Illness. Pediatr Rev. 2014 Aug 1;35(8):318–26. doi: 10.1542/pir.35-8-318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rogers JG, Patel CB, Mentz RJ, Granger BB, Steinhauser KE, Fiuzat M, et al. Palliative Care in Heart Failure: The PAL-HF Randomized, Controlled Clinical Trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017 Jul 18;70(3):331–41. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2017.05.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dellon EP, Leigh MW, Yankaskas JR, Noah TL. Effects of lung transplantation on inpatient end of life care in cystic fibrosis. J Cyst Fibros Off J Eur Cyst Fibros Soc. 2007 Nov 30;6(6):396–402. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2007.03.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schwantes S, O’Brien HW. Pediatric palliative care for children with complex chronic medical conditions. Pediatr Clin North Am. 2014 Aug;61(4):797–821. doi: 10.1016/j.pcl.2014.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Feudtner C, Kang TI, Hexem KR, Friedrichsdorf SJ, Osenga K, Siden H, et al. Pediatric palliative care patients: a prospective multicenter cohort study. Pediatrics. 2011 Jun;127(6):1094–101. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gade G, Venohr I, Conner D, McGrady K, Beane J, Richardson RH, et al. Impact of an Inpatient Palliative Care Team: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Palliat Med. 2008 Mar 1;11(2):180–90. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2007.0055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Teno JM, Clarridge BR, Casey V, Welch LC, Wetle T, Shield R, et al. Family Perspectives on End-of-Life Care at the Last Place of Care. JAMA. 2004 Jan 7;291(1):88–93. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.1.88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gallagher R, Krawczyk M. Family members’ perceptions of end-of-life care across diverse locations of care. BMC Palliat Care. 2013;12:25. doi: 10.1186/1472-684X-12-25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fraser L, Miller M, Aldridge J, Mckinney P, Parslow R. Life-limiting and life-threatening conditions in children and young people in the United Kingdom; national and regional prevalence in relation to socioeconomic status and ethnicity: Final Report For Children’s Hospital UK [Internet] Division of Epidemiology: University of Leeds; 2011. Oct, pp. 1–129. [cited 2016 Mar 18] (Life-Limiting Conditions in Children in the UK). Available from: http://www.togetherforshortlives.org.uk/assets/0000/1100/Leeds_University___Children_s_Hospices_UK_-_Ethnicity_Report.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- 44.American Academy of Pediatrics. Committee on Bioethics and Committee on Hospital Care. Palliative care for children. Pediatrics. 2000 Aug;106(2 Pt 1):351–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Care S on H and PM and C on H. Pediatric Palliative Care and Hospice Care Commitments, Guidelines, and Recommendations. Pediatrics. 2013 Nov 1;132(5):966–72. doi: 10.1542/peds.2013-2731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolfe J, Grier HE, Klar N, Levin SB, Ellenbogen JM, Salem-Schatz S, et al. Symptoms and suffering at the end of life in children with cancer. N Engl J Med. 2000 Feb 3;342(5):326–33. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200002033420506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Edwards KE, Neville BA, Cook EF, Aldridge SH, Dussel V, Wolfe J. Understanding of Prognosis and Goals of Care Among Couples Whose Child Died of Cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2008 Mar 10;26(8):1310–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.13.4056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Goodenough B, Drew D, Higgins S, Trethewie S. Bereavement outcomes for parents who lose a child to cancer: Are place of death and sex of parent associated with differences in psychological functioning? Psychooncology. 2004 Nov 1;13(11):779–91. doi: 10.1002/pon.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hechler T, Blankenburg M, Friedrichsdorf SJ, Garske D, Hübner B, Menke A, et al. Parents’ Perspective on Symptoms, Quality of Life, Characteristics of Death and End-of-Life Decisions for Children Dying from Cancer. Klin Pädiatr. 2008 May;220(03):166–74. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1065347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Bluebond-Langner M, Beecham E, Candy B, Langner R, Jones L. Preferred place of death for children and young people with life-limiting and life-threatening conditions: A systematic review of the literature and recommendations for future inquiry and policy. Palliat Med. 2013 Sep;27(8):705–13. doi: 10.1177/0269216313483186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Lowton K. “A bed in the middle of nowhere”: parents’ meanings of place of death for adults with cystic fibrosis. Soc Sci Med 1982. 2009 Oct;69(7):1056–62. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]