Abstract

Reading disorder is a recognized feature in Primary Progressive Aphasia (PPA). Surface dyslexia, characterized by regularization errors, is typically seen in the English-speaking semantic variant of PPA (svPPA). However, dyslexic characteristics of other languages, particularly logographical languages such as Chinese, remain sparse in the literature. This study aims to characterize and describe the dyslexic pattern in this group of patients by comparing the English-speaking svPPA group to the Chinese-speaking group. We hypothesize that Chinese-speaking individuals with svPPA will likely commit less surface dyslexic errors. By accessing the database of Singapore’s National Neuroscience Institute and National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center of United States, we identified 3 Chinese- and 18 English-speaking svPPA patients for comparison respectively. The results suggest that instead of surface dyslexia, Chinese-speaking svPPA is characterized by a profound deep dyslexic error. Based on current evidence suggesting the role of temporal pole as semantic convergence center, we conclude that this region also mediates and converges lexical-semantic significance in logographical languages.

Keywords: dyslexia, primary progressive aphasia, Chinese language

Introduction

The semantic variant of Primary Progressive Aphasia (svPPA) is a disorder which involves a breakdown in semantic knowledge, typically characterized by impaired single word comprehension and confrontational naming. Neuroimaging tends to show predominant anterior temporal lobe atrophy or hypometabolism (1). During reading, English-speaking svPPA patients typically exhibit surface dyslexia, and display regularization error of irregular words, such as “sew” being read as/su/ {2}. Presence of surface dyslexia is largely due to the dysfunction of the ventral reading pathway, and an over-reliance on the grapheme-phoneme conversion (GPC) or dorsal reading pathway {3}.

To date, little is known about the dyslexic characteristics in Chinese-speaking svPPA patients. Chinese is a logographical language which carries distinctive linguistic characteristics when compared to alphabetic languages such as English. Individual characters in the Chinese writing system are formed by basic graphic units. Each character represents the smallest unit of meaning and is monosyllabic {4}. Simple characters, made up of various spatial arrangements of strokes, can combine to form logographemes/radicals {5}. Approximately 80–90% of Chinese characters are ideophonetic compounds, formed by phonetic and semantic radicals, providing the pronunciation and meaning of the character respectively {4, 6}. Only a very small portion of simple characters are pictographic in nature. Some authors propose that Chinese characters consist of three levels of regularization with regard to the relationship between shape and pronunciation: regular, semi-regular, and irregular. In regular characters, the character is pronounced as a whole in the same manner as its phonetic radical (e.g., “座”/zuo4/, with the phonetic “坐”/zuo4/). In semi-regular characters, the phonetic radical provides partial information about pronunciation (e.g., “精”/jing1/and its phonetic “青”/qing1/). In irregular characters, the pronunciation of the character is different from its phonetic radical (e.g., “埋”/mai2/, with the phonetic “里”/li3/) {7–9}. As such, the Chinese language is considered an opaque language {4, 7–8}. However, other researchers have provided evidence that phonological awareness is reported to be comparatively less important in Chinese compared to other opaque languages {10–12}; instead, reading proficiency is related to other cognitive abilities such as orthographic awareness, visual skills and morphological awareness {10, 11}.

In view of the absence of phonemes that are associated with letters, some scholars believe Chinese has no GPC as per alphabetic language {13–16}. Studies have attempted to classify developmental Chinese dyslexic children according to dual route model but with inconsistent and controversies results {4, 9, 17}, unlike studies investigating alphabetic languages such as English and French, where classifying dyslexia with phonological and surface patterns were consistent {18–23}. In order to overcome the dual route model controversy when classifying Chinese dyslexia, Yin and Weekes used a similar concept called “the triangle model of Chinese reading”, which includes a lexical-semantic pathway that allows phonological output to directly access orthographical representation {24}. However, this model still poses limitations with regards to surface-like error finding when reading irregular Chinese words, probably due to the different fundamental linguistic characteristics of phonological processing between Chinese and English. The above highlights the limitation and controversies of heterogeneity findings of current Chinese reading models.

While previous cases report similar surface dyslexia patterns in Chinese-speaking semantic dementia patients {25–27}, we have also observed a different dyslexia pattern of in our svPPA patients, which ranges from failing to recognize characters as a whole (rather than ‘regularizing’ it), to deep dyslexia {28, 29}. In this study, we aim to further characterize dyslexia patterns in Chinese-speaking svPPA patients, and will compare it to English-speaking svPPA patients. We hypothesize that svPPA patients will commit less surface dyslexia, due to the lack of a GPC route in the Chinese language.

Methods

Study participants

We reviewed the dementia database of National Neuroscience Institute (NNI) Singapore from the year 2014 to 2016. Patients who fulfilled Gorno-Tempini’s criteria {1} for svPPA with Chinese language as their first language were identified and included in the study.

We also accessed data from the National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center (NACC) Uniform Data Set (UDS). The NACC collects data from National Institute on Aging (NIA)–funded Alzheimer’s Disease Centers (ADCs) in the United States. English-speaking patients with a clinical diagnosis of svPPA based on UDS – Frontotemporal Lobar Degeneration (FTLD) module form B9F item 13 code 1were included in this study. Information collected during their baseline visit was reviewed and details analyzed.

Research using the NACC database is approved by the University of Washington Institutional Review Board and data collection process is in accordance to NIA policies. The NACC database includes 34 past and present ADCs. Authors who access the data are required to sign and comply with the data use agreement. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants and informants at the individual ADCs and NACC data were de-identified {30}. The study involving NNI patients was also approved by the SingHealth Centralised Institutional Review Board. 3 Chinese-speaking svPPA patients from the NNI dementia database were identified and included. The final dataset from NACC analyzed for the current study used data from 17 ADCs and included 18 patients evaluated at the National Institute on Aging–funded Alzheimer Disease Centers (ADCs) from 2005 to December 2016.

Case Summary

Case 1

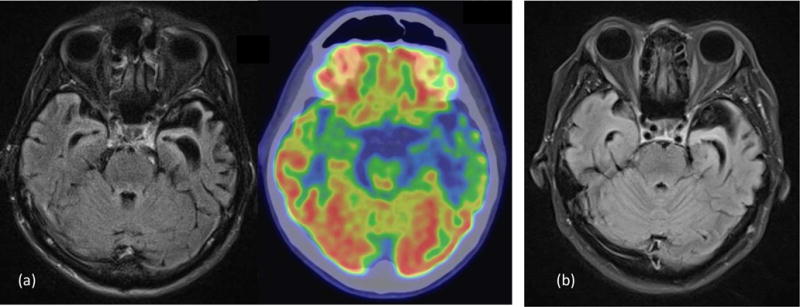

A 56-year-old right-handed Chinese Singaporean man presented with difficulty in comprehending sentences for one-year duration. He received Chinese-stream education up to secondary school. Neurobehavioral assessments showed fluent spontaneous speech and a Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) score of 19/30. An MRI of the brain showed left anterior temporal atrophy and a FDG-PET scan showed predominant left anterior temporal hypometabolism (Figure 2a).

Figure 2.

Neuroimaging examples of case 1 and case 2. (a) case 1: MRI brain FLAIR images and FDG-PET brain images showed a predominant left anterior temporal lobe atrophy and hypometabolism. (b) case 2: MRI brain FLAIR images showed a predominant left anterior temporal lobe atrophy.

Case 2

A 65 year-old right-handed Chinese Singaporean lady presented with gradual worsening of expression over a two-year period. She received Chinese-stream education up to secondary school. Family members noted that the patient frequently had difficulty in using the correct term and tended to replace it with others. Neurobehavioral examination showed fluent spontaneous speech with on and off semantic paraphasia. MRI brain showed left anterior temporal lobe atrophy (Figure 2b).

Case 3

A 53 year-old right-handed Chinese Singaporean lady who received Chinese-stream education up to secondary school presented with difficulty in comprehending and expressing words over a period between one to two years. Family members noted that the patient tended to frequently use the wrong names for vegetables and fruits during grocery shopping. Neurobehavioral examination showed fluent spontaneous speech with on and off semantic paraphasia. MRI brain performed showed left anterior temporal lobe atrophy.

Reading and semantic tasks

Data collected from the Chinese-speaking patients included a 10-word reading task and a short passage reading task from the Mandarin version of the Bilingual Aphasic Battery {31}, 10-item semantic picture matching derived from Comprehensive Aphasic Battery (CAT) {32}, and 15-item modified Boston Naming Test (BNT). Data collected from the English-speaking patients included in this study were a 30-item word reading test, 16-item semantic associates test from FTLD module form C1F item 3 and 6 respectively, and 30-item BNT from UDS module form C1 item 10.

Exclusion criteria included incomplete or inconsistent data of demographics, reading or semantic data details.

Statistical analysis

Chinese- and English-speaking svPPA groups were compared using Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction for continuous variables, with Chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests for categorical variables. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Multivariate analysis was not performed in this study due to the small sample size. All statistical analysis was performed in IBM SPSS version 23.

Results

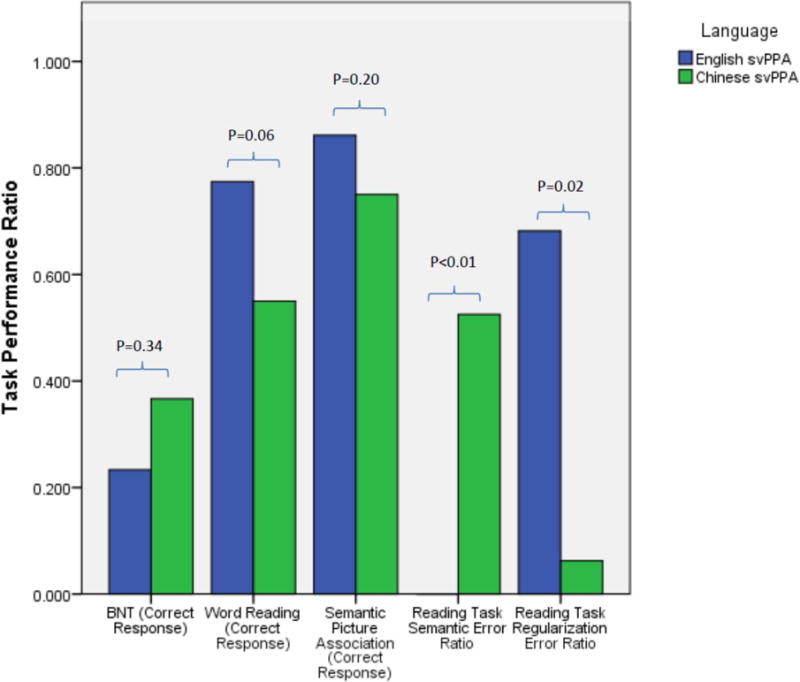

Both groups were comparable in terms of basic demographic except in years of education. Table 1 summarizes the details of the results. Table 2 summarizes the test performances of both language groups. Figure 1 describes the statistical comparison of task performance ratios between the 2 groups. Results showed comparable task performance of the BNT, word reading task, and semantic picture association task. However, semantic errors during reading tasks, indicating deep dyslexia, were noted to be present only in the Chinese-speaking group (p<0.01). Furthermore, the regularization errors during reading tasks were profoundly biased towards the English-speaking group (p = 0.02). Both these findings were statistically significant. Table 3 summarizes the semantic and regularization errors being committed by all 3 patients.

Table 1.

Demographics of both language groups.

| Chinese svPPA, n=3 | English svPPA, n=18 | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (S.D.) | 58.7 (6.6) | 60.6 (12.4) | 0.81 |

| Gender, male, n (%) | 1 (33.3) | 5 (27.8) | 0.84 |

| Education years, mean (S.D.) | 10.0 (0.0) | 16.9 (2.8) | <0.01 |

| Global CDR, mean (S.D.) | 0.50 (0.0) | 0.69 (0.42) | 0.45 |

Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction for continuous variables and Chi-square test for categorical variables. svPPA: Semantic variant of Primary Progressive Aphasia. CDR: Clinical Dementia rating scale. S.D.: Standard deviation. P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Table 2.

Summary of tests results of both language groups.

| Chinese svPPA, n=3 | English svPPA, n=18 | |

|---|---|---|

| BNT, mean (S.D.) | 6.0 (2.6) | 7.0 (6.4) |

| Word reading, mean (S.D.) | 4.7 (2.9) | 23.2 (3.9) |

| Paragraph reading error, mean (S.D.) | 3.7 (1.5) | – |

| Total Reading error, mean (S.D.) | 8.3 (1.5) | 6.8 (3.9) |

| Total Semantic error, mean (S.D.) | 5.0 (1.7) | 0.0 (0) |

| Total Regularization error, mean (S.D.) | 1.0 (1.0) | 4.2 (2.5) |

| Semantic Associates Test, mean (S.D.) | 7.5 (0.7) | 13.8 (1.9) |

BNT: Boston naming test. S.D.: standard deviation.

Figure 1.

Results summarizing performance ratio of both language groups. svPPA: semantic variant Primary Progressive Aphasia. BNT: Boston Naming Test. P: Wilcoxon rank sum test with continuity correction and P values of less than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Table 3.

Reading Task Characters and Error types

| Print Characters | Semantic Error | Regularization Error |

|---|---|---|

| 貓/mao1/cat | 鴨子/ya1zi3/duck, 豬/zhu1/pig | – |

| 狼/lang2/wolf | 熊/xiong2/bear | 良/liang2/good |

| 敲/qiao1/knock | 刮/gua1/scratch | 高/gao1/high |

| 針/zhen1/needle | 夾子/jia2zi3/clip | – |

| 刷/shua1/brush | 掃/sao3/sweep | – |

| 豬/zhu1/pig | 狗/gou3/dog, 鹿/lu4/deer | – |

| 鳥/niao3/bird | 鳥/ma3/horse | – |

| 抓/zhua1/catch | 掛/gua4/hook | – |

| 鴿/ge1/pigeon | 雞/ji1/chicken | – |

| 朋友/peng2you3/friend | 兄弟/xiong1di4/brother | – |

Discussion

Consistent with our previous case reports {28, 29}, the most important and interesting finding of our current study is the significant semantic-related dyslexic error observed only in the Chinese-speaking svPPA patients. Statistically comparable Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) and semantic picture task performance rate suggested that the two groups of patients probably shared a similar stage in clinical severity of the disease. Unfortunately due to the small sample size, multivariate logistic regression models could not be generated, and hence the results were not able to be adjusted for years of education. However, the complete absence of any semantic error in the English-speaking group but relatively high incidence rate in Chinese-speaking patients suggests the observation is likely valid.

Current literature recognizes a dual-route psycholinguistic model of reading consisting of a lexical and sublexical route {33–36}. Several functional studies also support the existence of such routes, which include the ventral-lexical-sound-to-meaning pathway extending from occipital-temporal-frontal region, and the dorsal-sublexical-sound-to-print pathway extending from occipital-parietal-frontal region. Ventral pathway impairment typically presents as failure to read irregular words, as phonological output of these words is directly imprinted into the orthographical representation in this pathway. Meanwhile, dorsal pathway impairment presents as failure to read morphologically complex words, as a result of impairment of print-to-sound or grapheme to phoneme correspondence (GPC) mechanism {37–42}.

Lesions in the ventral route result in an over-reliance on the dorsal route, and produces surface dyslexia, or regularization error. However, patients retain the capability to sound out pseudowords. On the other hand, dorsal route impairment produces phonological dyslexia, characterized by capability to read concrete words, but not pseudowords or words with low semantic value such as function words (eg. ‘it’, ‘the’), signifying an over-reliance on the semantic system. A recent behavior-lesion correlation study by Ripamonti and colleagues demonstrated consistent findings that surface dyslexia is predominantly associated with left temporal lesions and phonological dyslexia at left insula and the left inferior frontal gyrus (pars opercularis) {43}.

Semantic-related dyslexic error, or deep dyslexia, which has been mainly described in alphabetic languages such as English in literature, is perhaps the most extensively studied type of central dyslexia {44}. The term deep dyslexia was designated by Marshall and Newcombe when they described a patient (G.R.) with a tendency to produce errors that appeared to be semantically related to the target words {34}. The failure to produce a phonologically matched but semantically relevant response suggests an impairment of processes mediating the access of stimuli to the visual word form system {45}. The current literature mainly describes this phenomenon in alphabetic languages, with deep dyslexia largely being observed in the left hemisphere, especially in relation to large perisylvian lesions extending to frontal lobe {44}. Deep dyslexia is generally seen in patients suffering from non-fluent dysphasia, such as left middle cerebral artery infarction, which so far has not been associated with any neurodegenerative language disorder, particularly in alphabetic language speakers such as English. The postulation of producing such response has been inconclusive, with no clear consensus among experts. While some experts suggest that residual left hemispheric function is responsible for producing such erroneous responses, Coltheart {46} proposed it could in fact be due to underlying right hemispheric regions attributed to reading. Generally, deep dyslexic semantic errors are observed when phonological impairment prevents patients from using the surface route/GPC route and limits them to employ deep, direct route, hence prone for erroneous responses with production of semantic errors.

Literature describing acquired dyslexia in the Chinese language remains sparse to date, which may be due to the different mechanisms underpinning such phenomenology. Current studies of the lesioned brain and physiological functional study models support the notion that Chinese language processed distinctively when compared to alphabetic languages such as English {7, 28, 29, 47–50}. It is demonstrated that orthography in Chinese is more important in accessing semantics rather than phonology {47, 49} and phonology processing in Chinese is distinctive when compared to alphabetic languages {48}. While most studies describing Chinese deep dyslexia employed a model with a developmental approach, Shu and colleagues as well as Yin and colleagues {7, 50} described cases with deep dyslexia that were either trauma- or vascular-related brain lesions, which were explained well by the triangle model. However, most patients suffered more diffuse and less well localized lesions, and thus determining a more precise brain-behavior correlation is challenging.

Current literature suggests the temporal pole as the convergence region for semantic knowledge. Recent studies have also implicated it in lexical-semantic processing. For instance, Busigny et al. {51} suggested a case for lexico-facio-semantics disassociation, secondary to a dysfunction in the left anterior temporal lobe. Abel et al. provided neurophysiological evidence that the left and right anterior temporal lobe showed robust beta-band during visual naming of famous people and tools {52}. In studies investigating the temporal lobe in language processing in PPA, Wilson et al. demonstrated that its role in sentence processing is likely to relate to higher-level processes such as combinatorial semantic processing {53}, while Migliaccio and colleagues demonstrated its role in binding of lexical and semantic information in bidirectional manner {54}. As Chinese is a logographical language, where semantic data is tagged to each individual character, we speculate that this region also serves as a center of convergence of lexical semantics of the language, particularly in logographical languages. Taking into account the current existing evidence mentioned above, it is possible that this region may mediate the semantic relevance of orthographical representations, in this case, observed via an impaired non-semantic reading pathway.

Another finding in this study is the presence of surface dyslexia in both groups. However, regularization error, or surface dyslexia, was statistically more significantly observed in English speaking group. This is consistent with current literature suggesting a dual route model in reading for alphabetic languages, in which svPPA patients exhibit an over-reliance on the dorsal GPC route, which produces regularization error. While Chinese is considered an opaque language, with regularization errors described in both developmental and acquired dyslexic patients {9, 27}, Weekes predicted based on the triangle model that the presence of surface-like dyslexia is attributable to selective damage to the lexical semantic pathway. This type of error is also described as Legitimate Alternative Reading of Components (LARC) {55}, which was originally described in Japanese speaker {56}. In view of the different linguistic characteristics between English and Chinese, as discussed above, it is not surprising to observe a much higher rate of surface dyslexia in English-speaking group. This is consistent with a neurophysiology study, which suggested that more predominant ventral route functions were employed when reading Chinese {57}. This is also consistent with our previous observation of Chinese-speaking semantic dementia patients, where regularization error was not the most profound dyslexic finding {28, 29}.

Our findings of predominant deep dyslexia with milder form of regularization errors appeared consistent with the current disease model of acquired Chinese-speaking dyslexic patients with lesions, most profoundly at the temporal lobe, which is at the ventral route of dual route reading model. These results are probably best explained by triangle model. The surface-like errors in this study observed could be a result of impairment of semantic knowledge, and more common pronunciations of components would dominate computation of phonology from orthography via the lexical non-semantic pathway as proposed by Yin and colleagues {16}.

The strength of this study lies in being the first case series describing such clinical phenomenon, but the significant limiting factors are due to the small sample size. The complete absence of deep dyslexic errors in English-speaking group also poses challenges for generating a multivariate regression model. Future study should look into multi-center collaborations, in view of the relatively rarity of the disease itself, and a more consistent or unified clinical approach for better comparison. Further looking into performance of Pinyin, particularly in bilingual cases, should also be considered in future.

Our current study has few important conclusions. First, language finding function in neurodegenerative disorders is likely dependent on the characteristics of the patient’s dominant language. Second, the left temporal pole could possibly act as convergence center that mediates lexical semantics in logographical languages.

Acknowledgments

The NACC database is funded by NIA/NIH Grant U01 AG016976. NACC data are contributed by these NIA funded ADCs: P30 AG019610 (PI Eric Reiman, MD), P30 AG013846 (PI Neil Kowall, MD), P50 AG008702 (PI Scott Small, MD), P50 AG025688 (PI Allan Levey, MD, PhD), P50 AG047266 (PI Todd Golde, MD, PhD), P30 AG010133 (PI Andrew Saykin, PsyD), P50 AG005146 (PI Marilyn Albert, PhD), P50 AG005134 (PI Bradley Hyman, MD, PhD), P50 AG016574 (PI Ronald Petersen, MD, PhD), P50 AG005138 (PI Mary Sano, PhD), P30 AG008051 (PI Steven Ferris, PhD), P30 AG013854 (PI M. Marsel Mesulam, MD), P30 AG008017 (PI Jeffrey Kaye, MD), P30 AG010161 (PI David Bennett, MD), P50 AG047366 (PI Victor Henderson, MD, MS), P30 AG010129 (PI Charles DeCarli, MD), P50 AG016573 (PI Frank LaFerla, PhD), P50 AG016570 (PI Marie-Francoise Chesselet, MD, PhD), P50 AG005131 (PI Douglas Galasko, MD), P50 AG023501 (PI Bruce Miller, MD), P30 AG035982 (PI Russell Swerdlow, MD), P30 AG028383 (PI Linda Van Eldik, PhD), P30 AG010124 (PI John Trojanowski, MD, PhD), P50 AG005133 (PI Oscar Lopez, MD), P50 AG005142 (PI Helena Chui, MD), P30 AG012300 (PI Roger Rosenberg, MD), P50 AG005136 (PI Thomas Montine, MD, PhD), P50 AG033514 (PI Sanjay Asthana, MD, FRCP), P50 AG005681 (PI John Morris, MD), and P50 AG047270 (PI Stephen Strittmatter, MD, PhD).

This study is supported by Singhealth Foundation Grant (NRS 15/001), NNI Centre Grant (NCG CS02) and National Medical Research Council, Singapore (NMRC/IRG/015).

References

- 1.Gorno-Tempini ML, Hillis AE, Weintraub S, et al. Classification of primary progressive aphasia and its variants. Neurology. 2011;76:1006–1014. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31821103e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brambati SM, Ogar J, Neuhaus J, et al. Reading disorders in primary progressive aphasia: a behavioral and neuroimaging study. Neuropsychologia. 2009;47(8–9):1893–1900. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2009.02.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mummery CJ, Patterson K, Wise RJ, et al. Disrupted temporal lobe connections in semantic dementia. Brain. 1999;122:61–73. doi: 10.1093/brain/122.1.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho CSH, Chan DWO, Chung KKH, et al. In search of subtypes of Chinese developmental dyslexia. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology. 2007;97(1):61–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Law SP, Leung MT. Structural representations of characters in Chinese writing: Evidence from a case of acquired dysgraphia. Psychologia. 2000;43:67–83. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yin B, Rohsenow JS. Modern Chinese characters. Beijing: Sinolingua; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shu H, Meng X, Chen X, et al. The subtypes of developmental dyslexia in Chinese: Evidence from three cases. Dyslexia. 2005;11(4):311–29. doi: 10.1002/dys.310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ho CSH, Bryant P. Phonological skills are important in learning to read Chinese. Developmental Psychology. 1997;33:946–951. doi: 10.1037//0012-1649.33.6.946. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang LC, Yang HM. Classifying Chinese children with dyslexia by dual-route and triangle models of Chinese reading. Res Dev Disabil. 2014 Nov;35(11):2702–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ridd.2014.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McBride-Chang C, Cho JR, Liu H, et al. Changing models across cultures: associations of phonological awareness and morphological structure awareness with vocabulary and word recognition in second graders from Beijing, Hong Kong, Korea, and the United States. J Exp Child Psychol. 2005 Oct;92(2):140–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jecp.2005.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tong X, McBride-Chang C. Longitudinal predictors of very early Chinese literacy acquisition. Journal of Research in Reading. 2011;34(3):315–332. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lau DK, Leung MT, Liang Y, et al. Predicting the naming of regular-, irregular- and non-phonetic compounds in Chinese. Clin Linguist Phon. 2015;29(8–10):776–92. doi: 10.3109/02699206.2015.1034379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Law SP, Or B. A case study of acquired dyslexia and dysgraphia in cantonese: Evidence for nonsemantic pathways for reading and writing Chinese. Cognitive Neuropsychology. 2001;18:729–748. doi: 10.1080/02643290143000024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Siok WT, Perfetti CA, Jin Z, et al. Biological abnormality of impaired reading is constrained by culture. Nature. 2004;431:71–76. doi: 10.1038/nature02865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Weekes BS, Chen MJ, Gang YW. Anomia without dyslexia in Chinese. Neurocase. 1997;3:51–60. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Yin WG, He S, Weekes BS. Acquired dyslexia and dysgraphia in Chinese. Behavioural Neurology. 2005;16:159–167. doi: 10.1155/2005/323205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ho FC, Siegel L. Identification of sub-types of students with learning disabilities in reading and its implications for Chinese word recognition and instructional methods in Hong Kong primary schools. Reading and Writing: An Interdisciplinary Journal. 2012;25(7):1547–1571. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Castles A, Coltheart M. Varieties of developmental dyslexia. Cognition. 1993;47:149–180. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(93)90003-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Manis FR, Seidenberg MS, Doi LM, et al. On the bases of two subtypes of developmental dyslexia. Cognition. 1996;58:157–195. doi: 10.1016/0010-0277(95)00679-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sprenger-Charolles L, Cole P, Lacert P, et al. On subtypes of developmental dyslexia: Evidence from processing time and accuracy scores. Canadian Journal of Experimental Psychology. 2000;54:87–103. doi: 10.1037/h0087332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stanovich KE, Siegel LS, Gottardo A. Converging evidence for phonological and surface subtypes of reading disability. Journal of Educational Psychology. 1997;89:114–127. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williams MA, Stuart GW, Castles A, et al. Contrast sensitivity in subgroups of developmental dyslexia. Vision Research. 2003;43:467–477. doi: 10.1016/s0042-6989(02)00573-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ziegler JC, Castel C, Pech-Georgel C, et al. Developmental dyslexia and the dual route model of reading: Simulating individual differences and subtypes. Cognition. 2008;107(1):151–178. doi: 10.1016/j.cognition.2007.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yin WG, Weekes BS. Dyslexia in Chinese: Clues from cognitive neuropsychology. Annals of Dyslexia. 2003;53:255–279. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhang YM, Huang Y, Sun XJ, et al. Clinical and imaging features of a Chinese-speaking man with semantic dementia. J Neurol. 2008;255(2):297–8. doi: 10.1007/s00415-008-0694-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Luo BY, Zhao XY, Wang YW, et al. Is surface dyslexia in Chinese the same as in alphabetic one? Chin Med J (Engl) 2007;120(4):348–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wu XQ, Liu XJ, Sun ZC, Chromik L, Zhang YW. Characteristics of dyslexia and dysgraphia in a Chinese patient with semantic dementia. Neurocase. 2015;21(3):279–88. doi: 10.1080/13554794.2014.892621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ting SK, Hameed S. “Lexical Alexia” in a Chinese Semantic Dementia Patient. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2013;25:E37–E38. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.12100247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ting SK, Chia PS, Hameed S. Deep Dyslexia in Chinese Primary Progressive Aphasia of Semantic Variant. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2016;28(2):e25–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.neuropsych.15110385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Alzheimer’s Coordinating Center. For researchers using NACC data – information and resources. Available at: https://www.alz.washington.edu/WEB/researcher_home.html Accessed January 4, 2016.

- 31.Paradis M. Principles underlying the Bilingual Aphasia Test (BAT) and its uses. Clin Linguist Phon. 2011;25(6-7):427–43. doi: 10.3109/02699206.2011.560326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Swinburn K, Porter G, Al E. Comprehensive Aphasia Test. East Sussex: Psychology Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marshall J, Newcombe F. Syntactic and semantic errors in paralexia. Neuropsychologia. 1966;4:169–176. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Marshall J, Newcombe F. Patterns of paralexia: A psycholinguistic approach. Journal of Psycholinguistic Research. 1973;2:175–199. doi: 10.1007/BF01067101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Morton J, Patterson KE. A new attempt at interpretation, or, an attempt at a new interpretation. In: Coltheart M, Patterson KE, Marshall JC, editors. Deep dyslexia. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul; 1980. pp. 91–118. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Coltheart M, Curtis B, Atkins P, et al. Models of reading aloud: Dual-route and parallel-distributed-processing approaches. Psychological Review. 1993;100:589–608. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borowsky R, Cummine J, Owen WJ, et al. FMRI of ventral and dorsal processing streams in basic reading processes: insular sensitivity tophonology. Brain Topogr. 2006;18:233–239. doi: 10.1007/s10548-006-0001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Friederici AD. Pathways to language: fiber tracts in the human brain. Trends Cogn Sci. 2009;13:175–181. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2009.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jobard G, Crivello F, Tzourio-Mazoyer N. Evaluation of the dual route theory of reading: a metanalysis of 35 neuroimaging studies. Neuroimage. 2003;20:693–712. doi: 10.1016/S1053-8119(03)00343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Price CJ. The anatomy of language: a review of 100 fMRI studies published in 2009. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2010;1191:62–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05444.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pugh KR, Mencl WE, Jenner AR, et al. Functional neuroimaging studies of reading and reading disability (developmental dyslexia) Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 2000;6:207–213. doi: 10.1002/1098-2779(2000)6:3<207::AID-MRDD8>3.0.CO;2-P. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Steinbrink C, Vogt K, Kastrup A, et al. The contribution of white and gray matter differences to developmental dyslexia: insights from DTI and VBM at 3.0T. Neuropsychologia. 2008;46:3170–3178. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropsychologia.2008.07.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ripamonti E, Aggujaro S, Molteni F, et al. The anatomical foundations of acquired reading disorders: a neuropsychological verification of the dual-route model of reading. Brain Lang. 2014;134:44–67. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Coltheart M, Patterson K, Marshall JC, editors. Deep dyslexia. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 45.Colangelo A, Buchanan L. Localizing damage in the functional architecture: The distinction between implicit and explicit processing in deep dyslexia. J Neurolinguist. 2007;20(2):111–144. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Coltheart M. Deep dyslexia is right-hemisphere reading. Brain Lang. 2000;71(2):299–309. doi: 10.1006/brln.1999.2183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kong L, Zhang JX, Ho CS, et al. Phonology and access to Chinese character meaning. Psychol Rep. 2010;107(3):899–913. doi: 10.2466/11.22.28.PR0.107.6.899-913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tan LH, Laird AR, Li K, et al. Neuroanatomical correlates of phonological processing of Chinese characters and alphabetic words: a meta-analysis. Hum Brain Mapp. 2005;25:83–91. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zhang Q, Damian MF. Effects of orthography on speech production in Chinese. J Psycholinguist Res. 2012;41(4):267–83. doi: 10.1007/s10936-011-9193-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yin WG, Butterworth B. Deep and surface dyslexia in Chinese. In: Chen HC, Tzeng OJL, editors. Language processing in Chinese. Amsterdam: Elsevier Science Publishers; 1992. pp. 349–366. [Google Scholar]

- 51.Busigny T, de Boissezon X, Puel M, et al. Proper name anomia with preserved lexical and semantic knowledge after left anterior temporal lesion: a two-way convergence defect. Cortex. 2015;65:1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2014.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Abel TJ, Rhone AE, Nourski KV, et al. Beta modulation reflects name retrieval in the human anterior temporal lobe: an intracranial recording study. J Neurophysiol. 2016;115(6):3052–61. doi: 10.1152/jn.00012.2016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wilson SM, DeMarco AT, Henry ML, et al. What role does the anterior temporal lobe play in sentence-level processing? Neural correlates of syntactic processing in semantic variant primary progressive aphasia. J Cogn Neurosci. 2014;26(5):970–85. doi: 10.1162/jocn_a_00550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Migliaccio R, Boutet C, Valabregue R, et al. The Brain Network of Naming: A Lesson from Primary Progressive Aphasia. PLoS One. 2016;11(2):e0148707. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0148707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Weeks B, Chen HQ. Surface Dyslexia in Chinese. Neurocase. 1999;5:161–172. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Patterson K, Suzuki T, Wydell T, et al. Progressive aphasia and surface Alexia in Japanese. Neurocase. 1995;1:155–165. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Sun Y, Yang Y, Desroches AS, et al. The role of the ventral and dorsal pathways in reading Chinese characters and English words. Brain & Language. 2011;119:80–88. doi: 10.1016/j.bandl.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]