Abstract

Objective

Clinical guidelines suggest benzodiazepines (BZDs; e.g., alprazolam) and non-BZD hypnotics (nBHs; e.g., zolpidem) be used on a short-term basis. We examined trends in long-term BZD and nBH use from 1999–2014.

Methods

Data included 82,091 respondents in the 1999–2014 waves of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) (9,756–11,039 per wave). NHANES recorded medications used in past 30-days based on prescription bottles, and participants reported use duration. BZD and nBH use were categorized as short- (<6 months), medium- (6–24 months), and long-term (>24 months) and time trends in use were assessed.

Results

BZD and nBH use increased from 1999–2014 driven by increases in medium- and long-term use, even after adjustment for age and race/ethnicity. In most years, only a fifth of current BZD or nBH users reported short-term use.

Conclusions

Long-term BZD and nBH use has grown independent of US demographic shifts. Monitoring of use is needed to prevent adverse outcomes.

Keywords: hypnotics, chronic use, sleep, benzodiazepines

Introduction

Studies show increased prescribing of medications commonly used for treatment of anxiety and sleep disorders, specifically benzodiazepines (BZDs) and non-BZD hypnotics (nBHs), since the early 1990s (1,2), despite concerns about adverse health outcomes associated with their use (3,4). There is evidence that chronic use of these medications, particularly benzodiazepines, is associated with falls and hip fractures (3,4), and even accidental overdose when combined with opioids and/or alcohol (5). Concerns that long-term use may be associated with adverse outcomes (6), have prompted guidelines recommending use of these medications on a short-term basis (6,7). In recently published treatment guidelines for chronic insomnia, the American College of Physicians recommended that these medications be used only on a short-term basis and if behavioral treatments alone are ineffective (8). Similarly, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends against long-term treatment of generalized anxiety disorder with BZDs (9).

We recently reported that increases in continuing prescriptions (i.e., refills), rather than new prescriptions for these medications, are driving the growing trends in their prescribing, suggesting an increase in the long-term use of these medications (10). However, continued prescribing may not directly translate into long-term use by patients. For example, a patient may have received a prescription from a physician but not filled it at the pharmacy. Alternatively, a patient may have received a prescription for a medication to be used on an “as needed” basis and used the prescription rarely if at all. To our knowledge no research has examined trends in long-term use of BZDs and nBHs. Olfson et al. examined data on dispensed prescriptions and estimated that long-term use (defined as >180 days of refills) of BZDs ranged from .4% among those 18–35 years old to 2.7% for ages 65–80 years (11). However, that report was limited to one year (2008), and did not assess long-term nBH use.

Furthermore, little is known about whether indications for use of these medications are associated with duration of use. While nBHs are primarily prescribed for insomnia, BZDs have broad indications, including anxiety, epilepsy, alcohol withdrawal, in addition to insomnia; the underlying chronicity of these specific conditions may explain long-term use patterns. For example, it is possible that BZDs used for anxiety tend to be used on a long-term basis; whereas, when used for insomnia they are used on a short-term basis.

In this report, we examined national trends in long-term use of BZDs and nBHs from 1999 through 2014. This work in part extends a study by Bertisch et al. (12) who, using the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data, found an increase in the prevalence of use of insomnia medications from 1999 to 2010. Based on our own research (1) and that of Bertisch et al. (12), we hypothesized that the use of BZDs and nBHs increased between 1999 and 2014, and that this was driven by long-term use of these agents.

Methods

Data came from eight waves of the NHANES between 1999 and 2014. NHANES is a nationally representative cross-sectional survey conducted biennially (data obtained from http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/index.htm). NHANES conducts in-person interviews of non-institutionalized US respondents sampled using multi-staged stratified probability sampling methods. Response rates ranged from 71% to 84% across waves.

NHANES interviewers recorded medications used during the preceding month based on inspection of prescription bottles provided by participants, and participants reported duration of use for each medication. BZDs included alprazolam, clonazepam, clorazepate, chlordiazepoxide, diazepam, estazolam, flurazepam, lorazepam, oxazepam, temazepam, and triazolam. nBHs included zolpidem, zaleplon, and eszopiclone.

Based on a previous study (13), we categorized length of use into short-term (<6 months), medium-term (6 to 24 months), and long-term (>24 months). If participants used more than one medication from a class, use duration was based on the longest-used drug.

Analyses were conducted in three stages. First, we compared participant characteristics across the use duration for BZDs and nBHs and tested for differences through chi-squared tests. Next, we assessed trends between 1999 and 2014 in the prevalence of short-, medium- and long-term use of BZDs and nBHs using logistic regression models with dummy coded variables of short-, medium- and long-term BZD and nBH use as the outcome and time as the predictor. Time was transformed by subtracting 1 and dividing by 7 yielding a variable ranging from 0 (1999–2000 wave) and 1 (2013–2014 wave). Thus, the odds ratios from these models represent change in use over the entire study period. We further compared trends among short-, medium- and long-term use, employing seemingly unrelated regression analysis (the “suest” command in Stata).

Because changing trends in use of BZDs and nBHs may be in part driven by shifts in age and racial structure of the US population (14), we repeated analyses controlling for age and race/ethnicity.

Finally, we explored the self-reported reason for BZD and nBH use. Beginning in 2013–2014, participants reported up to three reasons for medication use. We tabulated reasons against duration of use.

This analysis was exempt from IRB review. Analyses were conducted in Stata SE version 13 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), and accounted for the NHANES weights and complex sampling design.

Results

Across all years, .5% of participants were short-term users of BZDs, .9% medium-term users, and 1.4% long-term users. Those with greater BZD use duration were generally older, more likely to be male, to have a high school diploma versus other education groups, and more likely to be non-Hispanic white compared to those with no or shorter duration of BZD use (all p’s <.001) (see Supplemental Table 1). Additionally, .2% were short-term users of nBHs, .4% medium-term users, and .4% long-term users. Those socio-demographic correlates of long-term nBH use were similar to the correlates of long-term BZD use (all p’s ≤.014) (see Supplemental Table 2).

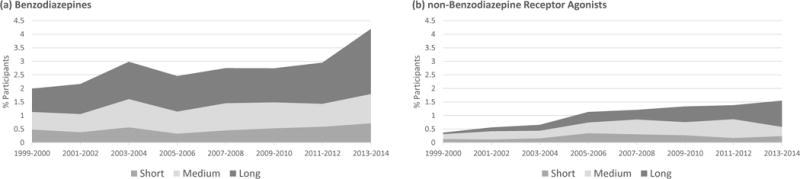

BZD and nBH use increased significantly over the study period (from 2.0% of respondents in 1999–2000 to 4.2% in 2013–2014, p<.001 for BZDs, and from .4% in 1999–2000 to 1.6% in 2013–2014, p<.001, for nBHs). Trends were driven by increases in use >6 months (Figure 1). From 1999 to 2014, odds of BZD use increased for medium-term use (Odds Ratio [OR] = 1.45, 95% Confidence Interval [CI]=1.02–2.07, p=.039) and for long-term use (OR=2.17, 95% CI=1.56–3.01, p<.001), but there were no significant changes for short-term use. There were marginally significant differences across BZD duration use regressions (F(2, 122)=2.94, p=.057). Odds of nBH use increased for medium-term use (OR=2.18, 95% CI=1.34–3.55, p=.002) and for long-term use (OR=8.32, 95% CI= 4.93–14.04, p<.001), with no significant change in short-term use. Across regressions, there were significant differences (F(2, 122)=8.22, p<.001). Results were similar after adjustment for age and race/ethnicity. After adjustment, odds of BZD use increased for long-term use (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 1.97, 95% CI=1.42–2.74, p<.001), and remained marginally significant for medium-term use (AOR=1.41, 95% CI=.98–2.02, p=.066). Odds of nBH use increased for medium-term use (AOR=2.22, 95% CI=1.33–3.71, p=.003), and for long-term use (AOR=7.78, 95% CI=4.55–13.30, p<.001). For these adjusted analyses, there was still a statistically significant difference across nBH models (F(2, 122)=7.29, p=.001), while differences across BZD models were insignificant.

Figure 1.

Trends in short- (<6 months), medium- (6–24 months), and long-term (>24 months) use of benzodiazepines and non-benzodiazepine hypnotics between 1999 and 2014.

In 2013–2014, virtually all of the 96 listed nBHs (97.9%) were used for sleep problems, and of these 94 nBHs, 85.1% were on a medium- or long-term basis. Among the 290 BZDs listed, 60.3% were used for anxiety problems, 29.3% were for sleep problems, 11.7% were for mood problems, 9% for other reasons, and .7% had missing reasons. About 83% of BZDs used for anxiety problems, 84.7% for sleep problems, 82.4% for mood problems, and 70.4% for other problems, were for medium- or long-term use.

Discussion

We found a growing trend in use of both BZDs and nBHs between 1999 and 2014, mirroring trends seen in prescription of these medications (1,2). We further found that growth in use was almost entirely attributable to increases in medium and long-term use (e.g., >6 months), suggesting that this pattern of use may be driving the increasing overall trend in the use of these medications. In exploratory analyses, long-term use of BZDs and nBHs was common regardless of indication.

Our findings of increased long-term use of BZD and nBH medications are not in accordance with recommendations in clinical prescribing guidelines, which generally discourage their long-term use (7–9). Future research needs to identify instances in which long-term use of sedating agents may be clinically indicated, differentiating these cases from those in which long-term use may be associated with greater likelihood of adverse outcomes. Furthermore, research may seek to identify means of monitoring risk of future adverse outcomes in long-term users, especially as they age. Such efforts may be feasible with the wider adoption of prescription drug monitoring programs. The observed trends could not be attributed to changes in the age or racial/ethnic structure of the US population because they persisted even after controlling for age and race/ethnicity.

While trends in long-term prescription and use of BZDs and nBHs are clear, the reasons for these trends are not. Whereas direct-to-consumer marketing may have driven nBH use in the early years of our study, it was most likely not responsible for increases in the older BZDs and recent increases as nBHs as their generic formulations were introduced in later years. Results from our previous study in prescribing suggested growth of prescribing in primary care practices (1). Thus, changes in composition of providers prescribing these medications and differences in practice styles may be, at least partly, responsible for the trend. Changes in public attitudes towards these medications, and psychiatric medications in general, may be another explanation. Regardless, research needs to assess patient and provider views of BZDs and nBHs, and assessment for these changing attitudes over time.

There is ample evidence supporting efficacy of behavioral treatments for insomnia and anxiety disorders (15). While cognitive behavioral therapy for anxiety is widely available, the use of behavioral treatments for insomnia is much less common (15). There are efforts to implement cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia in primary care settings as well as through the Internet and smartphone apps. Our findings highlight the need for wider dissemination of these interventions in various settings.

Conclusions

In summary, this study indicates that the observed increases in BZD and nBH use in recent years may be attributable to growth in long-term use. Limitations include the study’s cross-sectional design, and reliance on self-report data for medication use duration and reasons for use. Monitoring of long-term BZD and nBH use, particularly in vulnerable patients (e.g., older adults), may be important for understanding the reasons for changing pattern of use of these medications and prevention of potential adverse health outcomes associated with their use. Additionally, promoting the availability of behavioral sleep treatments may help reduce the need for pharmacological sleep interventions, as sleep problems remain a major reason for their long-term use. Findings highlight the pressing need for better delineation of appropriate medium- and long-term use of these medications.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Dr. Spira has agreed to serve as a consultant on Awarables, Inc. in support of an NIH grant.

Funding: Dr. Kaufmann received funding from the University of California San Diego’s T32 Research Fellowship in Geriatric Mental Health (T32MH019934).

Footnotes

Disclosures: All other authors have no disclosures to report.

Previous presentation: None

Contributor Information

Christopher N. Kaufmann, University of California, San Diego - Department of Psychiatry, La Jolla, California

Adam P. Spira, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health - Department of Mental Health, Baltimore, Maryland

Colin A. Depp, University of California, San Diego - Department of Psychiatry, La Jolla, California

Ramin Mojtabai, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health - Department of Mental Health, Baltimore, Maryland.

References

- 1.Kaufmann CN, Spira AP, Alexander GC, et al. Trends in prescribing of sedative-hypnotic medications in the USA: 1993–2010. Pharmacoepidemiology and drug safety. 2015:n/a–n/a. doi: 10.1002/pds.3951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ford ES, Wheaton AG, Cunningham TJ, et al. Trends in Outpatient Visits for Insomnia, Sleep Apnea, and Prescriptions for Sleep Medications among US Adults: Findings from the National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey 1999–2010. Sleep. 2014;37:1283–1293. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang PS, Bohn RL, Glynn RJ, et al. Zolpidem use and hip fractures in older people. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2001;49:1685–1690. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2001.49280.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rossat A, Fantino B, Bongue B, et al. Association between benzodiazepines and recurrent falls: a cross-sectional elderly population-based study. The journal of nutrition, health & aging. 2011;15:72–77. doi: 10.1007/s12603-011-0015-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jones CM, Mack KA, Paulozzi LJ. Pharmaceutical overdose deaths, United States, 2010. JAMA. 2013;309:657–659. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilt TJ, MacDonald R, Brasure M, et al. Pharmacologic Treatment of Insomnia Disorder: An Evidence Report for a Clinical Practice Guideline by the American College of Physicians. Annals of internal medicine. 2016;165:103–112. doi: 10.7326/M15-1781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.American Geriatrics Society 2015 Beers Criteria Update Expert Panel. American Geriatrics Society 2015 Updated Beers Criteria for Potentially Inappropriate Medication Use in Older Adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2015;63:2227–2246. doi: 10.1111/jgs.13702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, et al. Management of Chronic Insomnia Disorder in Adults: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Annals of internal medicine. 2016 doi: 10.7326/M15-2175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Generalised anxiety disorder and panic disorder in adults: management [Internet] 2011 Available from: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg113/resources/generalised-anxiety-disorder-and-panic-disorder-in-adults-management-pdf-35109387756997. [PubMed]

- 10.Kaufmann CN, Spira AP, Depp CA, et al. Continuing Versus New Prescriptions for Sedative-Hypnotic Medications: United States, 2005–2012. American journal of public health. 2016:e1–e7. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2016.303382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Olfson M, King M, Schoenbaum M. Benzodiazepine Use in the United States. JAMA psychiatry. 2014 doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bertisch SM, Herzig SJ, Winkelman JW, et al. National Use of Prescription Medications for Insomnia: NHANES 1999–2010. Sleep. 2014;37:343–349. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mojtabai R, Olfson M. National trends in long-term use of antidepressant medications: results from the U.S. National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2014;75:169–177. doi: 10.4088/JCP.13m08443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ortman JM, Velkoff VA. An aging nation: the older population in the United States. Washington: 2014. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Vitiello MV, McCurry SM, Rybarczyk BD. The future of cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia: what important research remains to be done? Journal of clinical psychology. 2013;69:1013–1021. doi: 10.1002/jclp.21948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.