Abstract

This study examined the impact of a stressful death/divorce on psychological and immune outcomes in people with HIV (PWH). PWH with stressful death/divorce were examined from before the event to up to 12 months later (n=45); controls were assessed at similar intervals (n=112). Stressful deaths/divorces were associated with increased viral load and anxiety over time (ps≤.013), but not CD4+ or depression. Increased use of religious coping after the stressful death/divorce was associated with slower increases in viral load (p=.016). These data suggest PWH should consider the potentially elevated risk of transmission after such events and seek appropriate monitoring and care.

Keywords: human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), stress, anxiety, spirituality, social support

Introduction

A substantial amount of research elucidates the roles stressful life events play in areas ranging from psychosocial functioning and social relationships to physical health and mortality. However, most studies that evaluate the impact of stressful life events face several limitations, primarily that the impact of stressful life events has not been measured before and after the event. This is understandable given the difficulty in collecting data before a stressful life event. In addition, the use of summary measures of stressful life events often group together several types of stressors, obscuring the impact that more severe events may have. Thus, the purpose of the current study is to determine the impact of stressful life events on psychological and biological outcomes prospectively from before a stressful death or divorce occurs to after. In addition, we sought to determine which methods of coping would buffer the impact of a stressful death or divorce. Studying the impact of stress in people with HIV (PWH) is helpful both because stressful life events are frequent in people with PWH and because the impact of stress on biologically meaningful markers (CD4, VL) can be observed.

Impact of death or divorce in general and medically ill populations

Research on specific stressors such as the impact of the death of a loved one or a separation/divorce from a partner has demonstrated a negative effect on mortality in the general population. For example, there is a greater mortality risk in divorced persons than in their married counterparts (Sbarra and Coan, 2017; Berntsen and Kravdal, 2012) with mixed evidence regarding whether this effect is greater for men or women (Shor et al., 2012). Likewise, there is also an increase in mortality risk following the death of a loved one, especially a spouse (Roelfs et al., 2011). This effect does appear to have a gender bias, as mortality for men following the loss of their spouse is greater than that of women. This effect is especially pronounced within the first 6 months of widowhood but begins to dissipate thereafter (Moon et al., 2011).

Not only does a significant death or divorce increase the likelihood of death in a general population, but these stressful life events increase the risk of declines in mental and/or physical health. With regards to mental health, death of a loved one has been associated with poor mental health outcomes including increased anxiety and depression (Bruce et al., 1990; Onrust and Cuijpers, 2006). Similar effects have been observed following a stressful divorce (Breslau et al., 2011). With regards to physical health, stressful life events are associated with an increased risk of cancer incidence (Chida and Vedhara, 2009), stroke, myocardial infarction and sudden cardiac death (Kornerup et al., 2010), and metabolic syndrome in healthy populations (Pyykkönen et al., 2010).

Impact of death or divorce in HIV positive populations

Stressful life events also have negative consequences in medically-ill populations. Stressful life events have been shown to exacerbate multiple sclerosis symptoms (Mitsonis et al., 2009) and increase anxiety in people with multiple sclerosis (Potagas et al., 2008). In addition, stressful life events have been associated with increased mortality in cancer populations (Chida et al., 2008).

Stressful life events have an especially deleterious effect on HIV-positive populations due to the negative impact of stress on the immune system (Segerstrom and Miller, 2004). To further compound this issue, stressful life events are associated with reductions in adherence to antiretroviral medications after the events (O’Donnell et al., 2017). In PWH, stressful life events increase the risk of mortality over a 3.5-year follow-up period (Leserman et al., 2007) and are associated with worse disease progression as well as a failure to sustain an undetectable viral load, the quantity of viral particles per mL of blood (Ironson et al., 2005; Mugavero et al., 2009). Although only nine studies have examined this relationship, a recent meta-analysis showed a trend towards an effect of stressful life events on viral load in PWH (Chida and Vedhara, 2009).

As with viral load, levels of CD4+ cells, which are essential to immune function, are markers of disease progression and proxies for immune system functioning. The research on the impact of stressful life events on CD4+ levels is mixed, with some studies showing that stressful life events reduce CD4+ levels (Leserman et al., 2002) and others showing no relationship (Ironson et al., 2005). In their meta-analysis, Chida and Vedhara (2009) did find a significant relationship between stressful life events and CD4+ cell decline; however, other predictors such as coping style and levels of distress were stronger predictors of CD4+ count decline. More research is required to clarify the relationship between CD4+ counts and stressful life events in general. With regard to specific stressors, AIDS-related bereavement in HIV-positive men has been associated with a decline in CD4+ levels (Kemeny and Dean, 1995). To the best of the authors’ knowledge, there has been no research investigating the impact of a divorce or separation from a partner in the HIV positive population.

In sum, the research investigating the impact of stressful life events on disease progression in people with HIV has been mixed; especially with regards to the impact such events have on viral load.

Potential Buffers of Death and Divorce

While there has been much written on coping with stressful life events in general (Stroebe, 2011) and with HIV in particular (Ironson et al., 2011), we focus on the use of religion/spirituality and social support to cope. The relationship between religion/spirituality and both mental and physical health is substantial (Koenig, 2008). The use of religion and/or spirituality to cope with life adversity is especially effective in situations where stressors are not readily amenable to change, such as in cases of the death of a loved one (Pargament et al., 1995; Park, 2005). The use of spirituality to cope with adversity is defined as a “set of cognitive-behavioral skills which focus on connection to a higher presence that aids in meaning making, positive reframing, self-empowerment, and growth on a personal/spiritual level” (Kremer and Ironson, 2009). Given that 85% of all PWH self-identify as spiritual (Lorenz et al., 2005) this represents a potentially powerful coping tool. Spirituality has been shown to help PWH cope with HIV-related stressors (Tarakeshwar et al., 2005a), cope with the loss of a loved one to AIDS (Richards et al., 1999), and help with overcoming the guilt and shame of engaging in risky behaviors that may have resulted in the contraction of the disease (Kaldjian et al., 1998). In addition, use of spirituality as a coping tool has been associated with higher quality of life and greater well-being over time (Trevino et al., 2010). With regard to the specific stressor of bereavement in PWH, the literature has generally suggested that religion and spirituality have a positive impact but there are some contradictory findings that would benefit from further research and clarification (Wortmann and Park, 2008). Little research is available regarding the impact of religion and spirituality as a tool for coping with divorce or separation from a partner, both in HIV positive and general populations. Further research is needed in this area as well.

Social support has also been identified as a powerful coping resource when facing stressful life events such as death and divorce in both healthy and medically ill populations. In general populations, for example, social support has been related to fewer depressive symptoms following bereavement (Stroebe et al., 2005) and lower mortality risk (Holt-Lunstad et al., 2010). In medically-ill populations, for example, social support has been associated with better emotional functioning and less anxiety in terminally ill cancer patients (Kolva et al., 2011), lower mortality after myocardial infarction (Frasure-Smith et al., 2000), and better health in HIV (Ironson and Hayward, 2008). The potential buffering effect of social support merits further examination in PWH.

This study aimed to advance understanding of the impact of stressful life events on immune functioning and distress among PWH by evaluating PWH who reported a stressful life event over a period of up to 18-months and concurrently evaluating a cohort of PWH who reported no stressful life events over the same period. We hypothesized that those experiencing a stressful death of a loved one or divorce would demonstrate greater reductions in CD4+ cell counts and greater increases in viral load, depression, and anxiety over time relative to controls. Exploratory analyses examined whether changes in use of religious coping and social support after the stressful life event predicted changes in outcome variables over time.

Methods

Eligibility

This study was part of a longer longitudinal study of stress and coping in PWH approved by the University of Miami Institutional Review Board. Methods are described in detail elsewhere (Ironson et al., 2005). Briefly, eligibility criteria required that participants not be drug dependent and be in the mid-range of HIV infection at study entry. That is, those eligible for participation had between 150 and 500 CD4+ cells/mm3 at baseline and had no history of any AIDS-defining illnesses (e.g., Kaposi’s sarcoma). Participants completed questionnaires and had blood drawn for CD4 and viral load every six months during the study.

Analyses in the current study were restricted to the 45 participants eligible for analyses in the death/divorce group and the 112 eligible for analyses in the control group. Participants in the death/divorce group reported a stressful death of a loved one and/or a stressful divorce/separation at any time point but were free of a stressful death/divorce in the 6 months preceding the event and the 12 months after the event. Control group participants reported no stressful death/divorce events in a period of at least 12 months. Participants who experienced a stressful death or divorce were those who indicated they had experienced such an event in the preceding 6 months and rated its impact on their lives as “extremely negative” or “moderately negative” on the Life Experiences Survey (Sarason et al., 1978).

Measures

Depression was measured using the Beck Depression Inventory (Beck et al., 1961), which has 21 items assessing cognitive, affective and somatic symptoms of depression over the past week. State anxiety was measured using the 20-item State Anxiety scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Spielberger et al., 1970). Social support was measured using the ENRICHD Social Support Instrument (Mitchell et al., 2003), a 7-item social support scale with an emphasis on emotional support over the past month. Use of religious coping was assessed using the Use of Religion to Cope subscale of the 60-item COPE Inventory (Carver, 1997). Items on the COPE were keyed to how participants coped with “HIV concerns or problems” in the previous month. Sample items include, “I put my trust in God” and “I try to find comfort in my religion.” Life events were assessed using the Life Experiences Survey (Sarason et al., 1978), which asked respondents to indicate whether various life experiences had occurred to them in the previous six months and to rate the degree to which it affected their lives. Medications were assessed using the interviewer-administered Adult AIDS Clinical Trials Group (AACTG) Adherence Instrument (Chesney et al., 2000), and dummy-coded to reflect whether participants were receiving no antiretroviral medications, combination therapy, or highly-active antiretroviral therapy (HAART). Assessment of viral load (in copies per milliliter) was conducted using the Roche Diagnostics (Basel, Switzerland) Amplicor RT/PCR assay of plasma RNA. CD4 lymphocyte counts (in cells per mm2) were assessed using whole-blood four-color direct immunofluorescence using a Beckman Coulter (Brea, California) XL-MCL flow cytometer.

Statistical Analyses

Chi-square and t-tests were conducted to identify group differences on sociodemographic factors and baseline medication regimen. Those significant at p<.05 would be included as covariates in multivariate analyses. Changes over time in outcome variables and their interaction with group membership were evaluated with mixed model analyses using SAS PROC MIXED Version 9.4 (Cary, NC). Unlike repeated-measures analysis of variance, mixed model analyses allow for the use of all available data at each time point without imputing missing data (Singer and Willett, 2003). Given that the death/divorce event occurred after the baseline assessment for those in the death/divorce group, analyses modeled not only the main effect of group membership and a linear group by time interaction on change over time in outcome variables, but also a quadratic group by time by time term. Because the focus of this study is on the influence of a death/divorce on change over time in the outcome variables examined, the group by time term is the focus of these analyses. Lastly, change over time in religious coping and social support from the pre-death/divorce assessment to the assessment immediately after the death/divorce event were independently examined as predictors of the change over time in outcome variables within the death/divorce group using mixed models. To control Type I error these analyses were planned to be conducted only in the outcomes for which we observed group differences in change over time. A two-sided alpha level of .05 was set for all statistical analyses.

Results

Descriptives

Of the 45 participants in the death/divorce group, 37 (82%) reported a stressful death of a loved one, 7 (16%) reported a stressful divorce, and one (2%) reported a stressful death and a stressful divorce. Demographic characteristics of the death/divorce group and the control group are presented in Table 1. Analyses were conducted to identify potential sociodemographic differences between groups. Participants who went on to experience a stressful death or divorce did not differ from control group participants on age, sex, education, racial/ethnic background, and medication regimen at baseline (ps ≥ .08). Thus, multivariate analyses did not control for sociodemographic factors or medication regimen.

Table 1.

Demographic characteristics of the sample

| Death/Divorce (n = 45) |

Controls (n = 112) |

DD vs. Controls | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Characteristic | p | ||

|

| |||

| Age, years | .78 | ||

| Mean | 42.14 | 41.70 | |

| SD | 10.01 | 8.49 | |

|

| |||

| Sex | .08 | ||

| Female | 56% | 29% | |

| Male | 44% | 71% | |

|

| |||

| Race/Ethnicity | .20 | ||

| White non-Hispanic | 33% | 23% | |

| Nonwhite | 67% | 77% | |

|

| |||

| Education | .10 | ||

| ≤ High school | 49% | 34% | |

| ≥ Some college | 51% | 66% | |

|

| |||

| Medication regimen at baseline | .53 | ||

| No HIV medications | 18% | 26% | |

| Combination therapy | 14% | 10% | |

| HAART therapy | 68% | 64% | |

Impact of a Stressful Death or Divorce on Immune Function and Distress

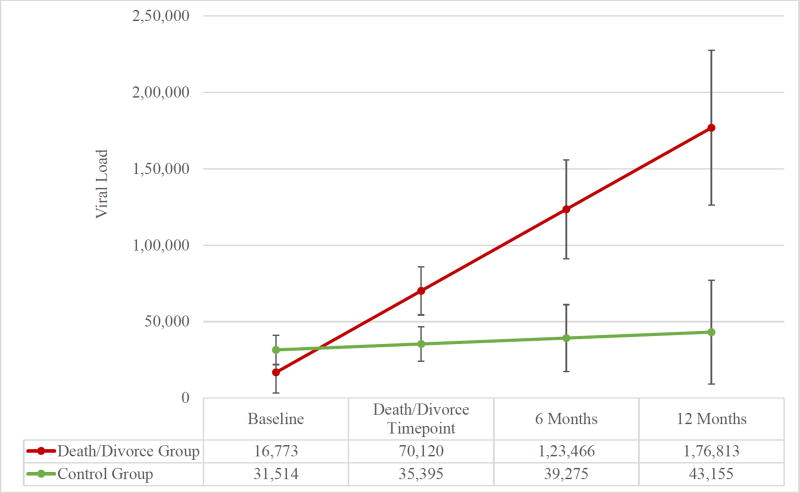

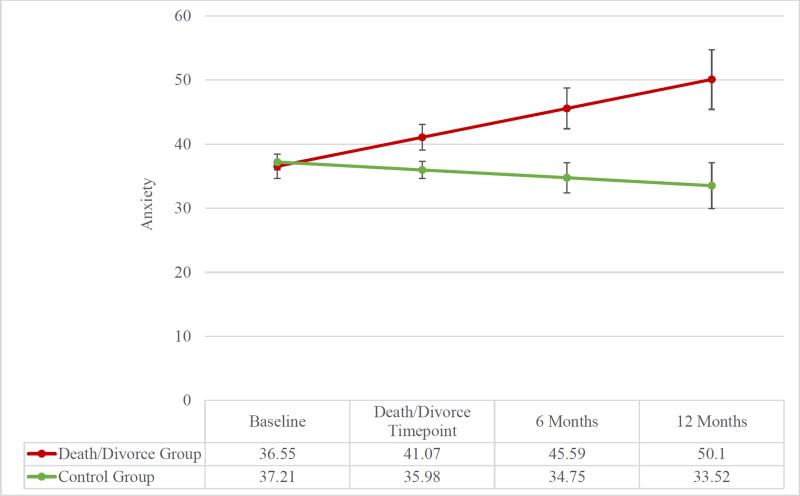

Changes over time in CD4, viral load, depression, and anxiety from before the stressful event to the timepoint immediately after were compared between those who experienced a death/divorce to controls. Change over time in CD4 counts (F(1, 389) = 0.30, p = .582) and depression (F(1, 400) = 2.49, p = .12) did not differ between participants who experienced a stressful death/divorce and controls. In contrast, group by time interactions were observed for viral load (F(1, 382) = 4.53, p = .034) and anxiety (F(1, 392) = 6.07, p = .014; see Figures 1 & 2). Examination of within-group change demonstrated that viral load (F(1, 111) = 7.83, p = .006) and anxiety (F(1, 110) = 7.37, p = .008) increased significantly over time in participants who experienced a stressful death/divorce. Neither viral load (F(1, 271) = 0.09, p = .759) nor anxiety (F(1, 282) = 0.87, p = .352) changed significantly over time in the control group.

Figure 1.

Estimated means and standard errors of viral load (copies per milliliter) from baseline to 12-months after the stressful death/divorce timepoint

Figure 2.

Estimated means and standard errors of state anxiety (State Trait Anxiety Inventory scores) from baseline to 12-months after the stressful death/divorce timepoint

Buffers of the Impact of a Stressful Death or Divorce

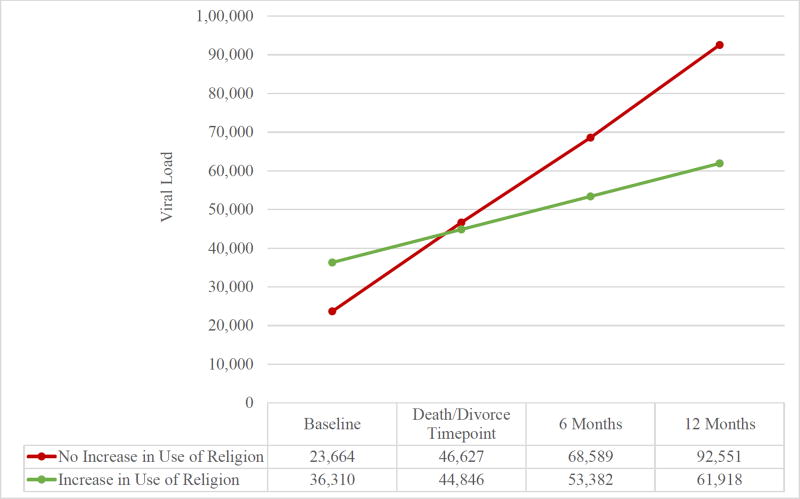

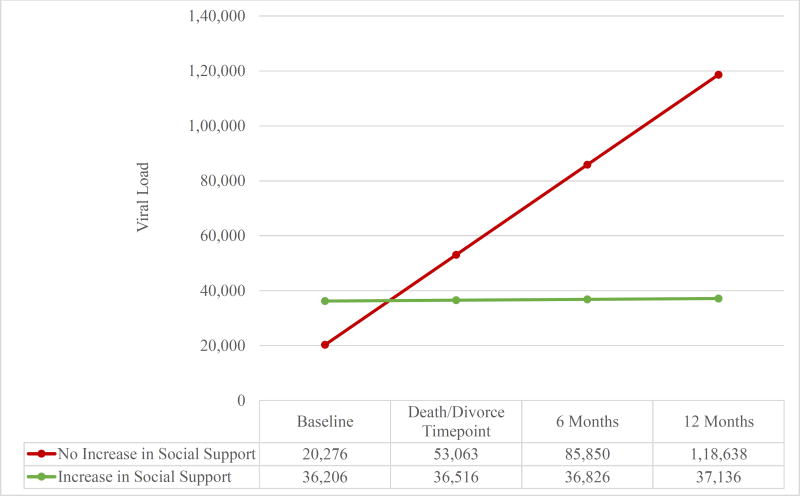

Analyses were conducted within the death/divorce group to identify predictors of the increases in viral load and anxiety seen among participants who experienced a stressful death/divorce (see Figures 3 and 4). Change in use of religious coping after a stressful death/divorce predicted changes in viral load, such that those whose use of religious coping increased after the stressful death/divorce exhibited slower increases in viral load than those whose use of religious coping did not increase (F(1, 104) = 6.82, p = .010). Changes in social support after a stressful death/divorce were not associated with changes in viral load (F(1, 104) = 2.57, p = .112). Changes in use of religious coping (F(1, 106) = 0.10, p = 0.752) and social support (F(1, 106) = 2.31, p = .132) were not associated with changes in anxiety.

Figure 3.

Estimated means of viral load (copies per milliliter) in participants whose use of religious coping increased vs. did not increase after the stressful death/divorce

Figure 4.

Estimated means of viral load (copies per milliliter) in participants whose social support increased vs. did not increase after the stressful death/divorce

Additional exploratory analyses found that baseline (pre-death/divorce) levels of religious coping (F(1, 109) = 3.25, p = .074) and social support were not associated with change over time in viral load (F(1, 109) = 1.24, p = .267). Similarly, baseline (pre-death/divorce) religious coping (F(1, 109) = 1.53, p = .218) and social support (F(1, 109), = 0.91, p = .341) were not associated with change over time in anxiety.

Discussion

Results partially confirmed hypotheses. Although group differences were not observed for changes in CD4+ cell counts and depression, HIV+ individuals who experienced a stressful death or divorce exhibited increasing HIV viral load and anxiety over time relative to a control sample of individuals with no such stressful life events. Among those with a stressful death or divorce, increases in use of religion as a coping strategy from before to after the stressful death or divorce were predictive of a slower rate of increase in viral load. A trend was observed for a similar relationship between increases in social support and viral load.

This was the first study to prospectively examine the impact of stressful life events in HIV+ individuals. These findings bolster the existing literature on the impact of stressful life events on physical health and psychological well-being. Although the hypotheses predicting that a stressful death or divorce would have a negative effect on CD4+ cell counts and depression were not supported, the findings that HIV viral load and anxiety were both impacted negatively has important implications.

The significant effects of stressful death or divorce on HIV viral load are consistent with previous research showing that stressful life events have negative impacts on physical health in the general population (Chida and Vedhara, 2009; Duijts et al., 2003; Kornerup et al., 2010) and medically ill populations (Chida and Vedhara, 2009; Mitsonis et al., 2009; Pyykkönen et al., 2010). This finding is also in line with some studies among individuals with HIV which show stressful life events are associated with worse control of HIV viral load or higher viral load (Chida and Vedhara, 2009; Ironson et al., 2005; Mugavero et al., 2009). Because most previous studies examined viral load only after the stressful life event, our study extends the existing literature by examining viral load both before and after the stressful life event and shows that viral load increases over time after a stressful life event. Findings of effects of stressful death or divorce on anxiety are similarly in line with previous literature in the general population (Bruce et al., 1990; Onrust and Cuijpers, 2006) and medically ill populations (Potagas et al., 2008). Yet, this study is the first we know of to examine the impact of stressful life events on anxiety among individuals with HIV.

In terms of clinical implications, these findings suggest that clinicians should discuss the potential impact that major life stressors can have on individuals with HIV. Doing so would enable patients to prepare for the elevated anxiety that has been found in this study and others. Patients may consider psychotherapy or the short-term use of anxiolytic medications to prevent the increased anxiety after a stressful death or divorce and the increase in viral load. In addition, patients should be informed of stress management and relaxation techniques that have demonstrated benefits for immune functioning and anxiety in previous studies (Antoni et al., 2000; Antoni et al., 2007; Antoni et al., 2006). The risk of increased viral load after a stressful life event is especially notable, given that stressful life events are associated with an approximately 25% increase in the incidence of unprotected sex in PWH (Pence et al., 2010) and that greater viral load is associated with a greater risk of transmission (Fisher et al., 2010).

Social support and use of religion/spirituality to cope can be effective buffers that mitigate the impact of these stressors on wellbeing. Clinicians can increase patient resilience to stressors by encouraging patients to engage in social networks available in the community for PWH, such as AIDSnetwork.org, or by encouraging engagement in activities that strengthen the patient’s sense of spirituality. Spirituality may be a particularly effective coping technique in situations such as death and divorce as these problems are not readily amenable to change. Methods for integrating spirituality into practice are reviewed by Padgett, Kusner, and Pargament (2015). This includes a manualized intervention, Lighting the Way: A Spiritual Journey to Wholeness, that enjoys some empirical support in pilot research (Tarakeshwar et al., 2005b) and is further described by Pargament, et al. (2004). Ways in which spirituality may help one to cope are reviewed by Ironson and Kremer (2011) as well as Park (2005) and include giving one a sense of calm, helping one feel supported and not alone, reframing the stressor in a more positive light (e.g., God is intending I grow from this), or expanding one’s perception of resources available to cope with the stressor such as being able to pray, feeling God is on your side.

Strengths of this study include its prospective design, use of clinically significant immunological and psychosocial variables, and controlling for medication type, including HAART. Nonetheless, some limitations should be noted, including a relatively small sample size. We were unable to describe the sample in terms of religious affiliation and level of religiosity/spirituality. Future studies in this area should examine whether the effects observed in this study are influenced by these factors. The direction of the associations between changes in spiritual coping and social support with changes in viral load cannot be clarified in this study. That is, it is possible that changes in the outcomes examined (viral load and anxiety) were responsible for changes observed in spiritual coping and social support. In addition, the use of psychotropic medications or other mental health services was not assessed in this study. These constitute potential confounds with anxiety, as many individuals seek these services before, during, and after a stressful life event such as a death or divorce. However, it is more likely that the use of psychotropic medications or mental health services would mitigate the effect of a stressful death or divorce. Thus, the effect we observed on anxiety may be underestimated. Future studies should aim to replicate these findings in larger samples of PWH. Further, interventions should be tested to ameliorate the negative impacts that a stressful death or divorce can have on individuals with PWH.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by grants from the National Institute of Mental Health: R01MH066697 (PI: Ironson) and R01MH053791 (PI: Ironson) as well as the National Cancer Institute: K01CA211789 (PI: Gonzalez).

Footnotes

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Gail Ironson, Department of Psychology, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL.

Sarah M. Henry, Department of Psychology, University of Miami, Coral Gables, FL.

Brian D. Gonzalez, Health Outcomes & Behavior Program, Moffitt Cancer Center, Tampa, FL.

References

- Antoni MH, Cruess DG, Cruess S, et al. Cognitive–behavioral stress management intervention effects on anxiety, 24-hr urinary norepinephrine output, and T-cytotoxic/suppressor cells over time among symptomatic HIV-infected gay men. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 2000;68:31. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.68.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH, Ironson G, Schneiderman N. Stress management for persons with HIV infection 2007 [Google Scholar]

- Antoni MH, Lechner SC, Kazi A, et al. How stress management improves quality of life after treatment for breast cancer. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:1143. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.6.1152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck AT, Ward CH, Mendelson M, et al. An inventory for measuring depression. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1961;4:561. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1961.01710120031004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berntsen KN, Kravdal O. The relationship between mortality and time since divorce, widowhood or remarriage in Norway. Soc Sci Med. 2012;75:2267–2274. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.08.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breslau J, Miller E, Jin R, et al. A multinational study of mental disorders, marriage, and divorce. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica. 2011;124:474–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.2011.01712.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruce ML, Kim K, Leaf PJ, et al. Depressive episodes and dysphoria resulting from conjugal bereavement in a prospective community sample. The American journal of psychiatry. 1990 doi: 10.1176/ajp.147.5.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carver CS. You want to measure coping but your protocol's too long: Consider the Brief Cope. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 1997;4:92–100. doi: 10.1207/s15327558ijbm0401_6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chesney MA, Ickovics J, Chambers D, et al. Self-reported adherence to antiretroviral medications among participants in HIV clinical trials: the AACTG adherence instruments. AIDS care. 2000;12:255–266. doi: 10.1080/09540120050042891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chida Y, Hamer M, Wardle J, et al. Do stress-related psychosocial factors contribute to cancer incidence and survival? Nature clinical practice Oncology. 2008;5:466–475. doi: 10.1038/ncponc1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chida Y, Vedhara K. Adverse psychosocial factors predict poorer prognosis in HIV disease: A meta-analytic review of prospective investigations. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity. 2009;23:434–445. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2009.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duijts SFA, Zeegers M, Borne BV. The association between stressful life events and breast cancer risk: A meta-analysis. International journal of cancer. 2003;107:1023–1029. doi: 10.1002/ijc.11504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher M, Pao D, Brown AE, et al. Determinants of HIV-1 transmission in men who have sex with men: A combined clinical, epidemiological and phylogenetic approach. Aids. 2010;24:1739–1747. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0b013e32833ac9e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frasure-Smith N, Lespérance F, Gravel G, et al. Social support, depression, and mortality during the first year after myocardial infarction. Circulation. 2000;101:1919–1924. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.101.16.1919. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt-Lunstad J, Smith TB, Layton JB. Social relationships and mortality risk: a meta-analytic review. PLoS medicine. 2010;7:e1000316. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, Hayward HS. Do positive psychosocial factors predict disease progression in HIV-1? A review of the evidence. Psychosomatic medicine. 2008;70:546–554. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e318177216c. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, Kremer H, Folkman S. Coping, spirituality, and health in HIV. The oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping. 2011:289–318. [Google Scholar]

- Ironson G, O’Cleirigh C, Fletcher MA, et al. Psychosocial factors predict CD4 and viral load change in men and women with human immunodeficiency virus in the era of highly active antiretroviral treatment. Psychosomatic medicine. 2005;67:1013–1021. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000188569.58998.c8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaldjian LC, Jekel JF, Friedland G. End-of-life decisions in HIV-positive patients: The role of spiritual beliefs. Aids. 1998;12:103–107. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199801000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemeny ME, Dean L. Effects of AIDS-related bereavement of HIV progression among New York City gay men. AIDS Education and Prevention. 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koenig HG. Medicine, religion, and health: Where science and spirituality meet. Templeton Foundation Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Kolva E, Rosenfeld B, Pessin H, et al. Anxiety in terminally ill cancer patients. Journal of pain and symptom management. 2011;42:691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2011.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kornerup H, Osler M, Boysen G, et al. Major life events increase the risk of stroke but not of myocardial infarction: Results from the Copenhagen City Heart Study. European Journal of Cardiovascular Prevention & Rehabilitation. 2010;17:113–118. doi: 10.1097/HJR.0b013e3283359c18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kremer H, Ironson G. Everything changed: Spiritual transformation in people with HIV. The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine. 2009;39:243–262. doi: 10.2190/PM.39.3.c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J, Pence B, Whetten K, et al. Relation of lifetime trauma and depressive symptoms to mortality in HIV. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1707–1713. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leserman J, Petitto JM, Gu H, et al. Progression to AIDS, a clinical AIDS condition and mortality: Psychosocial and physiological predictors. Psychological medicine. 2002;32:1059–1073. doi: 10.1017/s0033291702005949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz KA, Hays RD, Shapiro MF, et al. Religiousness and spirituality among HIV-infected Americans. Journal of palliative medicine. 2005;8:774–781. doi: 10.1089/jpm.2005.8.774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell PH, Powell L, Blumenthal J, et al. A short social support measure for patients recovering from myocardial infarction: the ENRICHD Social Support Inventory. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation and Prevention. 2003;23:398–403. doi: 10.1097/00008483-200311000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitsonis CI, Potagas C, Zervas I, et al. The effects of stressful life events on the course of multiple sclerosis: A review. International Journal of Neuroscience. 2009;119:315–335. doi: 10.1080/00207450802480192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon JR, Kondo N, Glymour MM, et al. Widowhood and mortality: A meta-analysis. PloS one. 2011;6:e23465. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugavero MJ, Raper JL, Reif S, et al. Overload: Impact of incident stressful events on antiretroviral medication adherence and virologic failure in a longitudinal, multisite human immunodeficiency virus cohort study. Psychosomatic medicine. 2009;71:920–926. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181bfe8d2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donnell JK, Gaynes BN, Cole SR, et al. Stressful and traumatic life events as disruptors to antiretroviral therapy adherence. AIDS care. 2017:1–8. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1307919. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onrust SA, Cuijpers P. Mood and anxiety disorders in widowhood: Asystematic review. Aging & Mental Health. 2006;10:327–334. doi: 10.1080/13607860600638529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Padgett EA, Kusner KG, Pargament KI. Integrating Religion and Spirituality Into Treatment. In: Lynn SJ, O’Donohue WT, Lilienfeld SO, editors. Health, Happiness, and Well-Being: Better Living Through Psychological Science. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications, In.; 2015. pp. 272–295. [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, McCarthy S, Shah P, et al. Religion and HIV: A review of the literature and clinical implications. Southern Medical Journal. 2004;97:1201–1210. doi: 10.1097/01.SMJ.0000146508.14898.E2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pargament KI, Smith B, Brant C. Annual meeting of the Society for the Scientific Study of Religion. St. Louis, MO: 1995. Religious and nonreligious coping methods with the 1993 Midwest flood. [Google Scholar]

- Park CL. Religion as a meaning-Making Framework in Coping with Life Stress. Journal of Social Issues. 2005;61:707–729. [Google Scholar]

- Pence BW, Raper JL, Reif S, et al. Incident stressful and traumatic life events and human immunodeficiency virus sexual transmission risk behaviors in a longitudinal, multisite cohort study. Psychosomatic medicine. 2010;72:720–726. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e3181e9eef3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potagas C, Mitsonis C, Watier L, et al. Influence of anxiety and reported stressful life events on relapses in multiple sclerosis: a prospective study. Multiple Sclerosis. 2008;14:1262–1268. doi: 10.1177/1352458508095331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyykkönen A-J, Räikkönen K, Tuomi T, et al. Stressful Life Events and the Metabolic Syndrome The Prevalence, Prediction and Prevention of Diabetes (PPP)-Botnia Study. Diabetes care. 2010;33:378–384. doi: 10.2337/dc09-1027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards A, Acree M, Folkman S. Spiritual aspects of loss among partners of men with AIDS: Postbereavement follow-up. Death studies. 1999;23:105–127. doi: 10.1080/074811899201109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roelfs DJ, Shor E, Kalish R, et al. The rising relative risk of mortality for singles: meta-analysis and meta-regression. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2011;174:379–389. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwr111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarason IG, Johnson JH, Siegel JM. Assessing the impact of life changes: development of the Life Experiences Survey. Journal of consulting and clinical psychology. 1978;46:932. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.46.5.932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sbarra DA, Coan JA. Divorce and health: good data in need of better theory. Current Opinion in Psychology. 2017;13:91–95. doi: 10.1016/j.copsyc.2016.05.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segerstrom SC, Miller GE. Psychological stress and the human immune system: a meta-analytic study of 30 years of inquiry. Psychological bulletin. 2004;130:601. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.4.601. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shor E, Roelfs DJ, Bugyi P, et al. Meta-analysis of marital dissolution and mortality: Reevaluating the intersection of gender and age. Social science & medicine. 2012;75:46–59. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.03.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied longitudinal data analysis: Modeling change and event occurrence. Oxford university press; 2003. Doing data analysis with the multilevel model for change; pp. 75–123. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger CD, Gorsuch RL, Lushene RE. Manual for the state-trait anxiety inventory 1970 [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe MS. Coping with bereavement. The oxford handbook of stress, health, and coping. 2011:148–172. [Google Scholar]

- Stroebe W, Zech E, Stroebe MS, et al. Does social support help in bereavement? Journal of social and clinical psychology. 2005;24:1030–1050. [Google Scholar]

- Tarakeshwar N, Hansen N, Kochman A, et al. Gender, ethnicity and spiritual coping among bereaved HIV-positive individuals. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2005a;8:109–125. [Google Scholar]

- Tarakeshwar N, Pearce MJ, Sikkema KJ. Development and implementation of a spiritual coping group intervention for adults living with HIV/AIDS: A pilot study. Mental Health, Religion & Culture. 2005b;8:179–190. [Google Scholar]

- Trevino KM, Pargament KI, Cotton S, et al. Religious coping and physiological, psychological, social, and spiritual outcomes in patients with HIV/AIDS: Cross-sectional and longitudinal findings. AIDS and Behavior. 2010;14:379–389. doi: 10.1007/s10461-007-9332-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wortmann JH, Park CL. Religion and spirituality in adjustment following bereavement: An integrative review. Death studies. 2008;32:703–736. doi: 10.1080/07481180802289507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]